Abstract

1,2-Dichloropropane (1,2-DCP) has been used as an industrial solvent and a chemical intermediate, as well as in soil fumigants. Human exposure may occur during its production and industrial use. The target organs of 1,2-DCP are the eyes, respiratory system, liver, kidneys, central nervous system, and skin. Repeated or prolonged contact may cause skin sensitization. In this study, 1,2-DCP was dissolved in corn oil at 0, 2.73, 5.75, and 8.75 mL/kg. The skin of mice treated with 1,2-DCP was investigated using western blotting, hematoxylin and eosin staining, and immunohistochemistry. 1,2-DCP was applied to the dorsal skin and both ears of C57BL/6J mice. The thickness of ears and the epidermis increased significantly following treatment, and the appearance of blood vessels was observed in the dorsal skin. Additionally, the expression of vascular endothelial growth factor, which is tightly associated with neovascularization, increased significantly. The levels of protein kinase-B (PKB), phosphorylated PKB, mammalian target of rapamycin (mTOR), and phosphorylated mTOR, all of which are key components of the phosphoinositide 3-kinase/PKB/mTOR signaling pathway, were also enhanced. Taken together, 1,2-DCP induced angiogenesis in dermatitis through the PI3K/PKB/mTOR pathway in the skin.

Keywords: 1,2-Dichloropropane; VEGF; Angiogenesis; Skin; NHFD cell

INTRODUCTION

1,2-Dichloropropane (1,2-DCP) is an organic compound classified as a chlorocarbon (1). It is also referred to as chloromethyl chloride, propylene chloride, propylene bichloride, propylene dichloride, and dichloro-1,2 propane (2). 1,2-DCP is a volatile organic chemical consisting of one hydrocarbon with two chlorines (1). It is obtained as a byproduct of the synthesis of propylene oxide by the chlorohydrin reaction (3). 1,2-DCP was originally used as a fumigant to control root parasitic nematodes in agriculture (4–6). Due to its carcinogenicity and environmental persistence, 1,2-DCP and other types of halogenated propanes have been replaced and are no longer applied to crops (7).

1,2-DCP has also been widely used as an industrial solvent or chemical intermediate during the production of chlorinated organic chemicals (8,9). 1,2-DCP is still used as a textile stain remover, solvent, lead scavenger in antiknock fluids, oil and paraffin extractant, paint and furniture finish remover, and metal-degreasing agent. Sublethal contact can lead to inhibition of the central nervous system (10,11). In rats, short-term exposure of 1,2-DCP by inhalation has been shown to cause liver injury (12).

Most known cases of human 1,2-DCP poisoning involve accidental intake of substances contained in cleansers and solvents (13,14). Symptoms following the ingestion of 1,2-DCP include liver and kidney disorders (high levels of asparagine and alanine transaminase, bilirubin, and creatinine and reduced levels of prothrombin), hemolytic anemia, metabolic acidosis, heart muscle weakness, and shock. However, there is no direct data regarding the effects of skin absorption. Systemic effects, such as death, have been shown to occur following the application of 1,2-DCP to rabbit skin. It is known that 1,2-DCP is absorbed through the skin (15).

The carcinogenicity of 1,2-DCP was evaluated in animal studies of rats and mice. Inhalation studies showed that exposure to 1,2-DCP increased the incidence of nasal tumors in male and female rats, lung tumors in female rats, and Harderian gland tumors in male mice (16,17). However, it was recently shown that inhalation of 1,2-DCP through the respiratory tract may lead to cholangiocarcinoma. In 2012, several workers in Japan working in an offset printing company suffered from cholangiocarcinoma. During the process of ink removal, they were exposed to a high concentration of 1,2-DCP for a long period of time (18). In 2014, the International Agency for Research on Cancer (IARC) reclassified 1,2-DCP from Group 3 to Group 1 (carcinogenic to humans) (19).

Angiogenesis is the physiological process by which new blood vessels are formed from previously existing vessels. Although angiogenesis is required during growth and development, abnormal angiogenesis has been linked to a number of human diseases, including cancer, cardiovascular disease, diabetes, age-related macular degeneration, and diabetic retinopathy (19–22). Vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF), originally known as vascular permeability factor, has the potential to induce the accumulation of ascites fluid due to the activity of tumor cells (23). The VEGF pathway accelerates angiogenesis (24). When VEGF interacts with its receptors in normal endothelial cells, the phosphoinositide 3-kinase (PI3K) and RAS pathways are activated. The mammalian target of rapamycin (mTOR) is downstream of the VEGF receptor (VEGFR)/PI3K/protein kinase B (PKB) pathway (25).

Cholangiocarcinoma was found among the workers who inhaled 1,2-DCP at work in a printing company, Japan. 1,2-DCP can also be absorbed through the skin into the blood circulation, causing internal damage. However, few studies have determined the effects of 1,2-DCP applied to the skin. Therefore, we conducted this study to investigate the effect of 1,2-DCP on the skin, by applying the agent to the dorsal skin and both ears of C57BL/6J mice. Dermatitis and vascular proliferation were both observed. To clarify the mechanisms of 1,2-DCP-induced dermatitis and angiogenesis, we performed immunohistochemistry (IHC) and western blotting, to assess protein expression of the pro-inflammatory cytokines interleukin (IL)-6 and tumor necrosis factor (TNF)-α and the angiogenesis factor VEGF.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Reagents and antibodies

1,2-DCP (99%) and corn oil were obtained from Sigma-Aldrich Co (St. Louis, MO, USA). The following antibodies were used: anti-VEGF (Santa Cruz Biotechnology Inc., Dallas, TX, USA), anti-phosphorylated PKB (p-PKB; Cell Signaling, Danvers, MA, USA), anti-PKB (Cell Signaling), anti-phosphorylated mTOR (p-mTOR; Cell Signaling), anti-mTOR (Cell Signaling), anti-TNF-α (Abcam, Cambridge, UK), anti-IL-6 (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA, USA), anti-actin (Sigma-Aldrich Co.), and anti-mouse or anti-rabbit secondary antibodies (Koma Biotech, Seoul, Korea).

Animals

C57BL/6J mice (6-week-old) were purchased from Jungang Animal Company (Seoul, Korea). Mice were observed for 1 day during acclimation and divided into four groups (n = 5 per group): (1) negative control −0 mL/kg 1,2-DCP, (2) 2.73 mL/kg 1,2-DCP, (3) 5.75 mL/ kg 1,2-DCP, and (4) 8.75 mL/kg 1,2-DCP. All groups were maintained under standard temperature (22.5 ± 0.5°C) and humidity (42.6 ± 1.7%) conditions. The experimental protocol used in this study has been approved by the Animal Care and Ethics Committee of Chungnam National University. All animal-handling procedures were performed according to the Guide of the Care and Use of Laboratory Animals of the Korea National Institutes of Health, and followed the guidelines of the Animal Welfare Act.

Cell lines

Normal human dermal fibroblast (NHDF) cells were maintained in Dulbecco’s modified Eagle’s medium (1:1) containing 10% fetal bovine serum and 1% antibiotic. NHDF cells were grown at 37°C in humidified 5% CO2.

Drug treatment

When 1,2-DCP is applied to the skin, the LD50 is 8.75 mL/kg, but the effects at 2.73 mL/kg are unknown. In this experiment, we tested the following concentrations: 0, 2.73, 5.75, and 8.75 mL/kg (26). 1,2-DCP was dissolved in corn oil. After 1 day of acclimation, the dorsal hair of mice was completely removed, followed by treatment with the various concentrations of 1,2-DCP (0, 2.73, 5.75, and 8.75 mL/kg) on the dorsal skin and both ears of mice, once a day for 7 days, while the control group was treated with coin oil without 1,2-DCP. After 7 days, the mice were sacrificed and dorsal skin was collected for subsequent experiments.

Euthanasia in mice

Avertin used in anesthetics dissolve 2.5 grams in 5 mL amylene hydrate. And adding distilled water, up to a final volume of 200 mL. Next, this material was filtered through a 0.22 μm size filter. The material is given by Intraperitoneal injection at a dose of 250 mg/kg.

Ear thickness measurements

Ear thickness were measured as an indirect method of determining skin inflammation caused by DCP. For each mouse, ear thickness was measured and recorded with a micrometer (Mitutoyo, Kawasaki, Japan). To minimize variation, a single investigator performed all measurements.

Histopathological analysis

At the end of the study period, the dorsal skin lesions of each mouse were removed, fixed with 10% neutral-buffered formalin, and embedded in paraffin. Sections of 4-μm thickness were stained with hematoxylin and eosin (H&E) to measure epidermal thickness. Histopathological evaluation of all skin sections was performed in a blind fashion. All samples were observed using an inverted microscope and data are representative of five observations (Nikon Eclipse Ti; Nikon, Tokyo, Japan).

IHC staining procedure

All specimens were fixed in 10% formalin and 4–6 μm sections were cut on glass slides for routine H&E staining. Sections were deparaffinized and rehydrated with graded alcohol to water. The avidin-biotin-peroxidase method and 3,3-diaminobenzidine chromogen were applied for IHC analysis. Endogenous peroxidase activity was blocked with 0.6% hydrogen peroxide. After blocking, sections were incubated at 4°C for 12 hr with antibodies against VEGF (Santa Cruz Biotechnology Inc.), IL-6 (Flarebio Biotech Co., Ltd., Wuhan, Hubei, China), and TNF-α (Abcam). The immunohistochemical markers were examined with an Olympus Korea Co (Seoul, Korea).

Western blot analysis

Western blot analysis was performed as the described previously (27). Protein lysates were prepared from the skin of mice and NHDF cells. Following treatment of NHDF cells with 1,2-DCP, cells were placed on ice, washed twice in ice-cold phosphate-buffered saline, and lysed at 4°C for 30 min in lysis buffer containing 50 mmol/L Tris-HCl, pH 7.5, 1% (v/v) Nonidet P-40 (NP-40), 250 mmol/L NaCl, 0.1 mmol/L phenyl methyl sulfonyl fluoride (PMSF), 0.1 mmol/L sodium vanadate, 20 mmol/L β-glycerol phosphate, 2 mmol/L dithiothreitol (DTT), 1 mmol/L leupeptin, and 10 mmol/L para-nitrophenylphosphate. The dorsal skin tissue from mice (~200 mg) was homogenized in lysis buffer with freshly added protease inhibitors using a mortar and pestle or sonication, and lysates were centrifuged at 13,000 ×g for 1 hr. Protein concentrations were determined according to the BCA protein assay and the standard plot was generated using bovine serum albumin. Protein samples (60 μg) from the different concentrations of 1,2-DCP were denatured by boiling at 100°C for 3 min in sample buffer containing β-mercaptoethanol. Protein was separated by 10% sodium dodecyl sulfate polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis and transferred to nitrocellulose membranes. After blocking with 5% skim milk in Tris-buffered saline (TBS) containing 0.02% Tween-20 at room temperature for 1 hr, the blots were incubated with primary antibody (1:1,000) overnight at 4°C and β-actin (1:5,000) was used as a loading control. Following incubation with primary antibodies, blots were washed four times for 15 min in TBS/Tween-20 before incubation for 1 hr at room temperature with goat anti-mouse or anti-rabbit horse radish peroxidase-conjugated antibody (1:2,000) in TBS/Tween-20 containing 5% skim milk. Proteins were detected with an enhanced chemiluminescence kit (Amersham Biosciences, Buckinghamshire, UK).

Statistical analysis

Quantification of western blot analysis was carried out using ImageJ software (NIH, Bethesda, MD, USA). An overall difference between more than two groups was determined using a one-way ANOVA. If one-way ANOVAs were significant, differenced between individual groups were estimated using a Dunnett’s Multiple comparison test. All calculations and data plotting were performed using GraphPad Software (San Diego, CA, USA). Data are presented as means ± standard deviation. A p-value < 0.05 was considered significant, compared with corresponding control values.

RESULTS

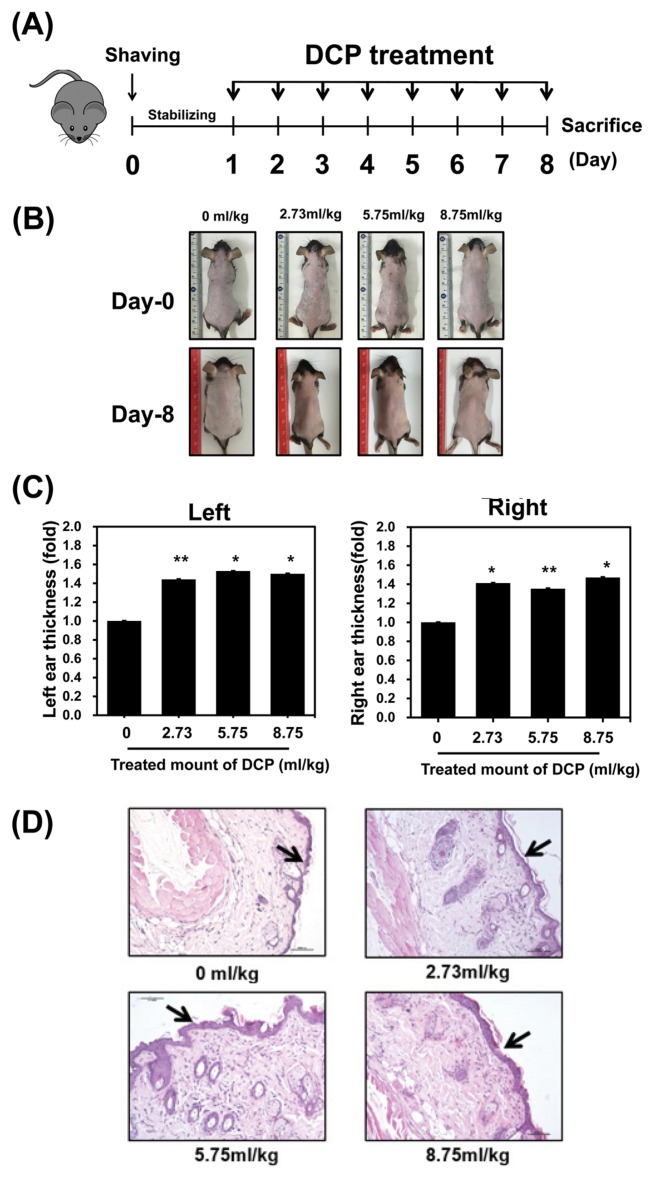

Effects of 1,2-DCP on skin thickness in mice

To investigate the effects of 1,2-DCP on normal mouse skin, we applied 1,2-DCP to the dorsal skin and both ears for 7 days. The concentrations tested were 0, 2.73, 5.75, and 8.75 mL/kg (26), and the experimental scheme is summarized in Fig. 1A. The top photograph in Fig. 1B reflects the first day of the experiment, immediately after shaving, and the photograph below shows the dorsal image of mice after 7 days of daily treatment with 1,2-DCP. After 7 days of treatment, ear thickness increased significantly in a dose-dependent manner (Fig. 1C). We also performed H&E staining of the dorsal skin and observed the tissue under an optical microscope. Dorsal histopathological results showed thickening of the epidermis in a dose-dependent manner in 1,2-DCP-treated mice (Fig. 1D). These results suggest that inflammatory reactions may have occurred.

Fig. 1.

Effect of 1,2-dichloropropane (1,2-DCP) on skin thickness in C57BL/6J mice. (A) Experimental schedule for drug treatment. After 1 day of acclimation, the dorsal hair of mice was completely removed, followed by treatment with the various concentrations of 1,2-DCP (0, 2.73, 5.75, and 8.75 mL/kg) on the dorsal skin and both ears of mice, once a day for 7 days (indicated as an black arrow), while the control group was treated with corn oil without 1,2-DCP. After 7 days, the mice were sacrificed and dorsal skin was collected for subsequent experiments. (B) Image of the first day of the experiment, immediately after shaving (above), and dorsal image of mice after 7 days of daily treatment with 1,2-DCP (below). (C) Ear thickness was measured with a micrometer. Columns represent group means ± SD of ear fold thickness measurements at day-7 (D) Skin histopathological findings following treatment with 1,2-DCP. All sections were stained with hematoxylin and eosin. Mice were treated with 0, 2.73, 5.75, and 8.75 mL/kg 1,2-DCP. Epidermal thickening was observed (20×, scale bar = 10 μm). The results are means ± standard deviation (SD) of two independent experiments. *p < 0.05; **p<0.01.

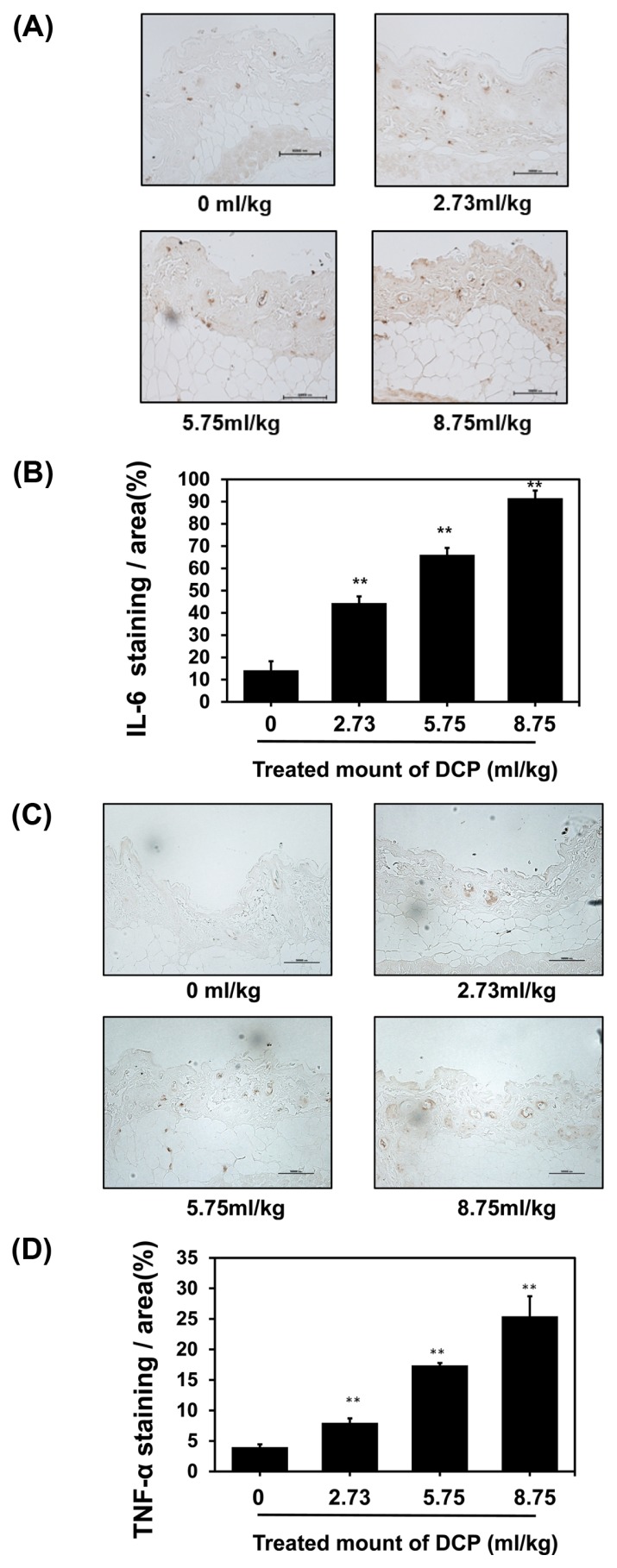

1,2-DCP increases pro-inflammatory cytokine expression

A previous study reported that 1,2-DCP induced contact dermatitis (28). Moreover, pro-inflammatory cytokines, such as IL-6 and TNF-α, were unregulated during the contact reaction (29). In the present study, mice were treated with 1,2-DCP for 7 days. After completion of treatment, the dorsal skin was collected. To determine whether 1,2-DCP treatment induced dermatitis, the pro-inflammatory cytokines IL-6 and TNF-α were detected by IHC staining, which showed that their expression levels were higher than in the control groups, and increased in a dose-dependent manner (Fig. 2A, 2C). Quantification of IHC staining-positive areas in the skin is shown in Fig. 2B, 2D. Together, this finding suggests that 1,2-DCP induces dermatitis, and an increased co ncentration of 1,2-DCP results in increased expression of pro-inflammatory factors.

Fig. 2.

Effects of 1,2-DCP on the expression of pro-inflammatory cytokines in 1,2-DCP-treated mice. (A) Immunohistochemistry (IHC) of interleukin (IL)-6 in dorsal skin treated with 1,2-DCP (brown staining considered positive; 400×, scale bar = 10 μm). (C) IHC of skin tumor necrosis factor (TNF)-α in dorsal skin treated with 1,2-DCP (brown staining considered positive; 400×, scale bar = 10 μm). (B, D) Quantification of IHC-positive areas in the skin is shown on the right. The data were analyzed by Image-Pro Plus software (Media Cybernetics, Silver Spring, MD, USA). The results are means ± SD of two independent experiments. **p<0.01.

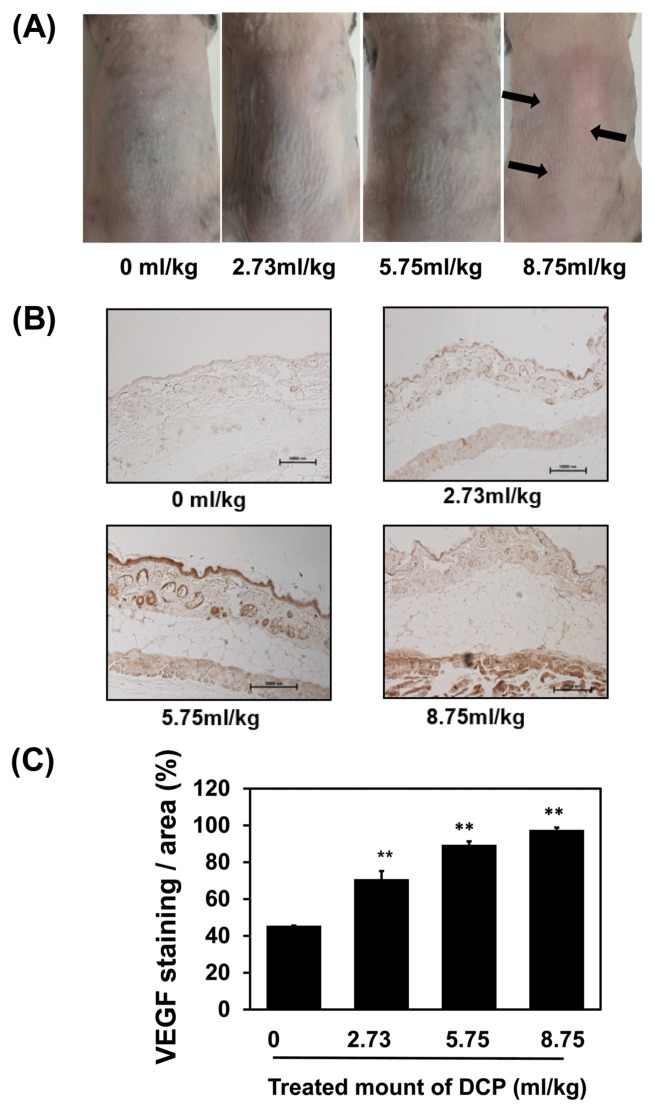

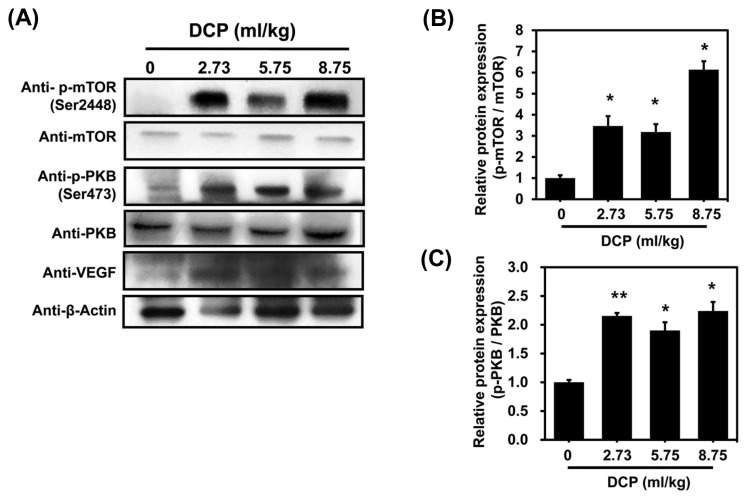

1,2-DCP induced angiogenesis through activation of the PI3K signaling pathway

VEGF is a potent angiogenic factor having effects on endothelial cells that are mediated by the PI3K pathway (30). mTOR is a downstream target of the VEGFR/PI3K/PKB pathway (31). We observed that blood vessels were enlarged in the dorsal skin of mice treated with 1,2-DCP for 7 days (Fig. 3A). VEGF also showed higher expression in 1,2-DCP-treated sections compared with the control in a dose-dependent manner (Fig. 3B, 3C). To further study the mechanisms underlying VEGF-driven angiogenesis in 1,2-DCP-administered mice, we performed western blotting to assess p-AKT and p-mTOR activity, which are both important in the PI3K/AKT/mTOR signaling pathway. As shown in Fig. 4, the protein levels of p-AKT and p-mTOR increased significantly in a dose-dependent manner. 1,2-DCP increased cell proliferation and angiogenesis by activating the PI3K signaling pathway. These results suggested that the PI3K signaling pathway was activated in 1,2-DCP-treated mice.

Fig. 3.

1,2-DCP enhanced angiogenic signaling. (A) In 1,2-DCP-treated mice, the challenged dorsal skin remained vascularized. (B) Immunofluorescence of vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF) following 1,2-DCP treatment in mice. (C) Quantification of IHC-positive areas in the skin is shown on the right. The data were analyzed by Image-Pro Plus software. Mice treated with 1,2-DCP at each indicated concentration (0, 2.73, 5.75, and 8.75 mL/kg) for 7 days (400×, scale bar = 10 μm). The results are means ± SD of two independent experiments. **p < 0.01.

Fig. 4.

Protein expression of VEGF, phosphorylated protein kinase B (p-PKB), and phosphorylated mammalian target of rapamycin (p-mTOR) in the angiogenic sites. (A) Western blot analysis of VEGF, p-PKB, and p-mTOR following 1,2-DCP treatment in mice. Actin was used as a loading control. (B, C) Graph shows densitometric quantification of bands. The results are means ± SD of two independent experiments. *p < 0.05; **p<0.01.

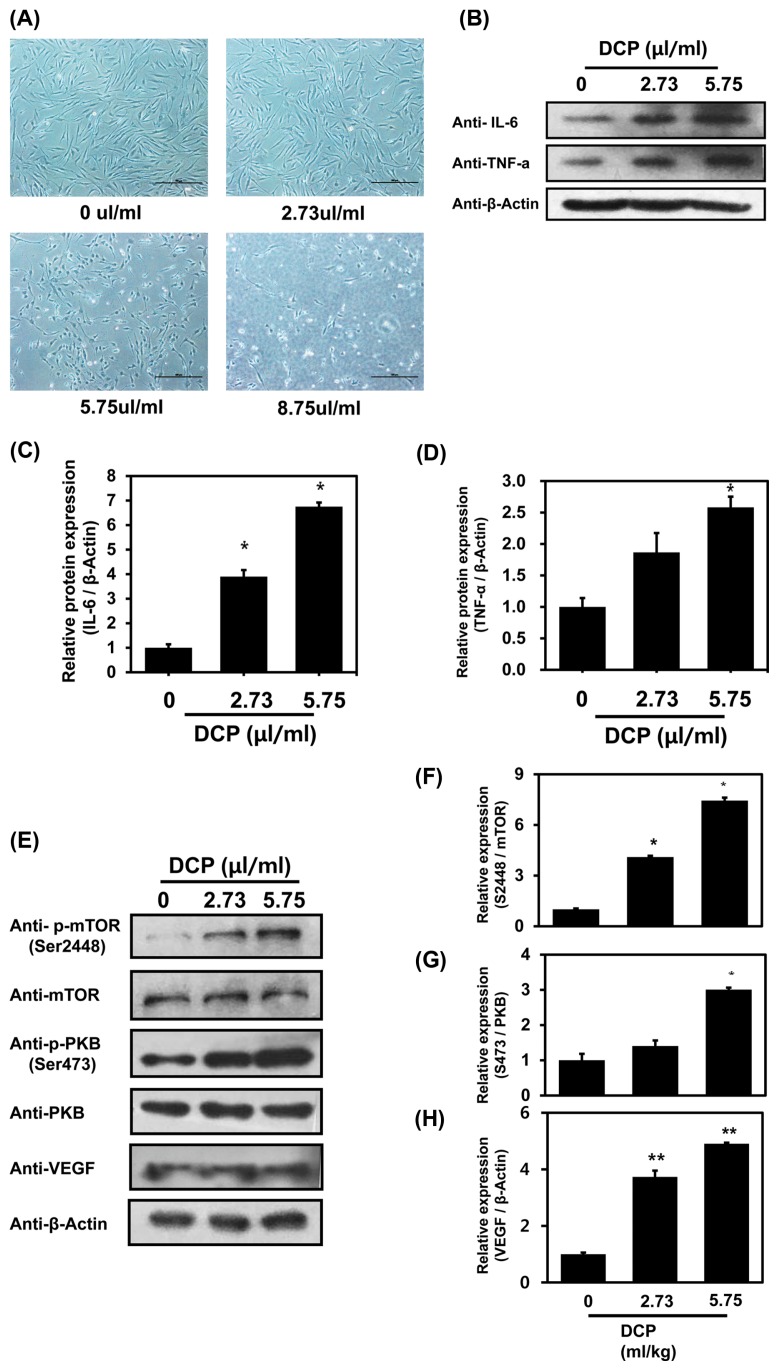

1,2-DCP induced angiogenesis through activation of the PI3K signaling pathway in NHFD cells

NHDF cells were treated with 1,2-DCP at doses of 2.73, 5.75, and 8.75 μL/mL for 24 hr and imaged. Cells treated with 5.75 and 8.75 μL/mL 1,2-DCP exhibited an increased rate of cell death compared with untreated control cells (Fig. 5A). As shown in Fig. 5A, treatment of cell with 8.75 μL/mL 1,2-DCP caused the cell-death. Therefore, it was not possible to recover the cell extracts from the treatment of cell with 8.75 μL/mL 1,2-DCP. Protein extracts of untreated and 1,2-DCP-treated cells were analyzed by western blotting. Some studies have shown that pro-inflammatory cytokines, such as IL-6 and TNF-α, are unregulated during inflammation (29). VEGF induces angiogenesis through the PI3K/PKB pathway (32) and mTOR is a downstream target of the VEGFR/PI3K/PKB pathway (31). Our results showed that protein levels of IL-6, TNF-α, VEGF, p-AKT, and p-mTOR were increased in a dose-dependent manner (Fig. 5B-5H). These data indicate that 1,2-DCP not only induces inflammation, but also induces angiogenesis in NHFD cells through the PI3K signaling pathway.

Fig. 5.

1,2-DCP induces inflammation and activates angiogenic signals in NHFD cells. (A) NHFD cells (1 × 106) were grown in 3.5 mm diameter cell culture dishes and treated with 1,2-DCP at doses of 0, 2.73, 5.75, and 8.75 μL/mL for 24 hr and imaged. (B, E) Western blot analysis of IL-6, TNF-α, VEGF, p-PKB, and p-mTOR following 1,2-DCP treatment in NHFD cells. Actin was used as a loading control. The graph shows densitometric quantification of bands. (C, D, F–H) The results are means ± SD of two independent experiments. *p < 0.05; **p < 0.01.

DISCUSSION

1,2-DCP is a chemical intermediate that is used as a solvent in industry, and as an insecticide fumigant in agriculture (33). Acute exposure to 1,2-DCP can cause damage to the liver and kidneys in humans and animals (34). It is also used as a cleaner in offset-printing processes in Japan. In 2012, workers of an offset proof-printing company in Japan suffered from cholangiocarcinoma following long-term exposure to high levels of 1,2-DCP during ink removal operations (35). In 2014, the IARC reclassified 1,2-DCP from Group 3 to Group 1 (carcinogenic to humans) (18). Several younger employees who were exposed to halohydrocarbon solvents mainly composed of 1,2-DCP for a long period of time developed occupational cholangiocarcinoma (36). For workers involved in the production or use of 1,2-DCP, there is a risk of chemical exposure by inhalation or dermal contact. However, little attention has been paid to the impact of 1,2-DCP on the skin.

In the present study, we applied 1,2-DCP to the dorsal skin and both ears of mice for 7 days. We observed that ear and dorsal skin thickness increased in a dose-dependent manner (Fig. 1). Moreover, the expression levels of the pro-inflammatory cytokines TNF-α and IL-6 were upregulated in a dose-dependent manner (Fig. 2).

Dermatitis is known to result in dysfunction of the epidermal barrier. The preformed IL-1β is released by disruption of the skin barrier, and is the first step in the inflammatory cascade of contact dermatitis (32). Activated IL-1β stimulates further production of proinflammatory cytokines and chemokines, such as IL-1β, TNF-α, and IL-6, by surrounding epidermal and dermal cells (32,33). Our results revealed that 1,2-DCP application on the skin of mice induced dermatitis.

Following treatment with 1,2-DCP, vascular proliferation was observed in the dorsal skin in the group of mice treated with the highest concentration of 1,2-DCP (Fig. 3A). Angiogenesis begins with vasodilation. The increased vascular permeability in response to VEGF allows the extravasation of plasma proteins, and the plasma protein deposition is used as a provisional scaffold for migrating endothelial cells (37). VEGF is an important signaling protein involved in both vasculogenesis and angiogenesis (38). It is secreted primarily by keratinocytes and is an effective mediator of angiogenesis (39). TNF-α (40) and IL-6 (41) can potentiate VEGF production. TNF-α has also been shown to induce angiogenesis in a variety of experimental models (19). In this study, vascular dilation was observed in dorsal mice treated with 1,2-DCP and the expression level of VEGF increased in a dose-dependent manner, as assessed by western blotting and IHC. Thus, we confirmed that 1,2-DCP induces angiogenesis.

VEGF is an effective angiogenic factor, and its effect on endothelial cells is mediated by the PI3K pathway (30). The phosphatase and tensin homolog (PTEN) gene encodes a phosphatase that counteracts the effect of PI3K, thereby reducing the level of activated PKB, which controls protein synthesis and cell growth by triggering the phosphorylation of mTOR.

In this study, protein levels of AKT, p-AKT, mTOR, and p-mTOR, all of which are key factors of the PI3K/AKT/ mTOR signaling pathway, were shown to be increased by western blotting (Fig. 4). Thus, the PI3K/AKT/mTOR pathway was activated in 1,2-DCP-treated mice. The same experimental results were also obtained for 1,2-DCP-treated NHFD cells (Fig. 5). Activation of the PI3K/PKB/ mTOR pathway can increase the secretion of VEGF. The PI3K/PKB pathway also regulates other angiogenic factors, such as nitric oxide and angiopoietins (42). Together, these findings reveal that 1,2-DCP induced angiogenesis in dermatitis through the P13K/PKB/mTOR pathway in the skin.

When 1,2-DCP is in contact with skin, it increases the expression of inflammatory factors and angiogenesis factors, such as IL-6, TNF-α and VEGF, which induces dermatitis and angiogenesis. Therefore, these results clearly indicated and explained how 1,2-DCP can induced the cholangiocarcinoma in workers who were exposed to halohydrocarbon solvents mainly composed of 1,2-DCP for a long period of time previously (43). The observation of current report could be included as a mechanism of carcinogenesis for 1,2-DCP in the recent review about occupational cholangiocarcinoma (44).

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

This study was supported by research fund of Chungnam National University (Jongsun Park) and Basic Science Research Program through the National Research Foundation of Korea, funded by the Ministry of Education (NRF-2016K1A3A1A08953546, NRF-2014R1A1A3050752 and NRF-2015R1A2A2A01003597).

List of abbreviations

- 1,2-DCP

1,2-Dichloropropane

- IL-6

Interleukin-6

- NHFD cell

Normal human fibroblast cell

- TNF-α

Tumor necrosis factor alpha

- VEGF

Vascular endothelial growth factor.

Footnotes

CONFLICT OF INTEREST

The authors have no conflict of interest to disclose.

REFERENCES

- 1.Rossberg M, Lendle W, Pfleiderer G, Tögel A, Dreher E-L, Langer E, Rassaerts H, Kleinschmidt P, Strack H, Cook R, Beck U, Lipper K-A, Torkelson TR, Löser E, Beutel KK, Mann T. Chlorinated Hydrocarbons in Ullmann’s Encyclopedia of Industrial Chemistry. Wiley Online Library; Germany: 2006. pp. 11–25. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Agency for Toxic Substances and Disease Registry. Toxicological Profile for 1,2-Dichloropropane. Atlanta, GA, USA: 2019. Available from: http://www.atsdr.cdc.gov/ToxProfiles/tp.asp?id=831&tid=162/ [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Timchalk C, Dryzga MD, Smith FA, Bartels MJ. Disposition and metabolism of [14C]1,2-dichloropropane following oral and inhalation exposure in Fischer 344 rats. Toxicology. 1991;68:291–306. doi: 10.1016/0300-483X(91)90076-D. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Fletcher KE, Löffler FE, Richnow HH, Nijenhuis I. Stable carbon isotope fractionation of 1,2-dichloropropane during dichloroelimination by Dehalococcoides populations. Environ Sci Technol. 2009;43:6915–6919. doi: 10.1021/es900365x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Tesoriero AJ, Löffler FE, Liebscher H. Fate and origin of 1,2-dichloropropane in an unconfined shallow aquifer. Environ Sci Technol. 2001;35:455–461. doi: 10.1021/es001289n. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Albrecht WN, Chenchin K. Dissipation of 1,2-dibromo-3-chloropropane (DBCP), cis-1,3-dichloropropene (1,3-DCP), and dichloropropenes from soil to atmosphere. Bull Environ Contam Toxicol. 1985;34:824–831. doi: 10.1007/BF01609813. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Loffler FE, Champine JE, Ritalahti KM, Sprague SJ, Tiedje JM. Complete reductive dechlorination of 1,2-dichloropropane by anaerobic bacteria. Appl Environ Microbiol. 1997;63:2870–2875. doi: 10.1128/aem.63.7.2870-2875.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.1,2-Dichloropropane. IARC Monogr Eval Carcinog Risks Hum. 1999;71(Pt 3):1393–1400. [No authors listed] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Toyoda Y, Takada T, Suzuki H. Halogenated hydrocarbon solvent-related cholangiocarcinoma risk: biliary excretion of glutathione conjugates of 1,2-dichloropropane evidenced by untargeted metabolomics analysis. Sci Rep. 2016;6:24586. doi: 10.1038/srep24586. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Imberti R, Calabrese SR, Emilio G, Marchi L, Giuffrida L. Acute poisoning with solvents: chlorinated aliphatic hydrocarbons. Minerva Anestesiol. 1987;53:399–403. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Lucantoni C, Grottoli S, Gaetti R. 1, 2-Dichloropropane is a renal and liver toxicant. Letter Toxicol Appl Pharmacol. 1992;117:133. doi: 10.1016/0041-008X(92)90228-K. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.World Health Organization. 1,2-Dichloropropane. IARC Monogr Eval Carcinog Risk Chem Hum. 1986;41:131–147. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Di Nucci A, Imbriani M, Ghittori S, Gregotti C, Baldi C, Locatelli C, Manzo L, Capodaglio E. 1,2-Dichloropropane-induced liver toxicity: Clinical data and preliminary studies in rats in The Target Organ and the Toxic Process. Springer; 1988. pp. 370–374. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Larcan A, Lambert H, Laprevote MC, Gustin B. Acute poisoning induced by dichloropropane. Acta Pharmacol Toxicol (Copenh) 1976;41(Suppl 2):330. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Pozzi C, Marai P, Ponti R, Dell’Oro C, Sala C, Zedda S, Locatelli F. Toxicity in man due to stain removers containing 1, 2-dichloropropane. Br J Ind Med. 1985;42:770–772. doi: 10.1136/oem.42.11.770. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Umeda Y, Matsumoto M, Aiso S, Nishizawa T, Nagano K, Arito H, Fukushima S. Inhalation carcinogenicity and toxicity of 1,2-dichloropropane in rats. Inhal Toxicol. 2010;22:1116–1126. doi: 10.3109/08958378.2010.526973. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Matsumoto M, Umeda Y, Take M, Nishizawa T, Fukushima S. Subchronic toxicity and carcinogenicity studies of 1,2-dichloropropane inhalation to mice. Inhal Toxicol. 2013;25:435–443. doi: 10.3109/08958378.2013.800618. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Benbrahim-Tallaa L, Lauby-Secretan B, Loomis D, Guyton KZ, Grosse Y, El Ghissassi F, Bouvard V, Guha N, Mattock H, Straif K International Agency for Research on Cancer Monograph Working Group. Carcinogenicity of perfluorooctanoic acid, tetrafluoroethylene, dichloromethane, 1,2-dichloropropane, and 1,3-propane sultone. Lancet Oncol. 2014;15:924–925. doi: 10.1016/S1470-2045(14)70316-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Marcus Y, Shefer G, Stern N. Adipose tissue renin-angiotensin-aldosterone system (RAAS) and progression of insulin resistance. Mol Cell Endocrinol. 2013;378:1–14. doi: 10.1016/j.mce.2012.06.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Yang W, Yu X, Zhang Q, Lu Q, Wang J, Cui W, Zheng Y, Wang X, Luo D. Attenuation of streptozotocin-induced diabetic retinopathy with low molecular weight fucoidan via inhibition of vascular endothelial growth factor. Exp Eye Res. 2013;115:96–105. doi: 10.1016/j.exer.2013.06.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Yang Z, Wang H, Jiang Y, Hartnett ME. VEGFA activates erythropoietin receptor and enhances VEGFR2-mediated pathological angiogenesis. Am J Pathol. 2014;184:1230–1239. doi: 10.1016/j.ajpath.2013.12.023. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Barot M, Gokulgandhi MR, Patel S, Mitra AK. Microvascular complications and diabetic retinopathy: recent advances and future implications. Future Med Chem. 2013;5:301–314. doi: 10.4155/fmc.12.206. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Senger DR, Galli SJ, Dvorak AM, Perruzzi CA, Harvey VS, Dvorak HF. Tumor cells secrete a vascular permeability factor that promotes accumulation of ascites fluid. Science. 1983;219:983–985. doi: 10.1126/science.6823562. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Shibuya M. Vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF)-Receptor2: its biological functions, major signaling pathway, and specific ligand VEGF-E. Endothelium. 2006;13:63–69. doi: 10.1080/10623320600697955. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Takekoshi K, Isobe K, Yashiro T, Hara H, Ishii K, Kawakami Y, Nakai T, Okuda Y. Expression of vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF) and its cognate receptors in human pheochromocytomas. Life Sci. 2004;74:863–871. doi: 10.1016/j.lfs.2003.07.036. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Smyth HF, Jr, Carpenter CP, Weil CS, Pozzani UC, Striegel JA, Nycum JS. Range-finding toxicity data: List VII. Am Ind Hyg Assoc J. 1969;30:470–476. doi: 10.1080/00028896909343157. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Park J, Lee H, Tran Q, Mun K, Kim D, Hong Y, Kwon SH, Brazil D, Park J, Kim SH. Recognition of transmembrane protein 39A as a tumor-specific marker in brain tumor. Toxicol Res. 2017;33:63–69. doi: 10.5487/TR.2017.33.1.063. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Baruffini A, Cirla AM, Pisati G, Ratti R, Zedda S. Allergic contact dermatitis from 1,2-dichloropropane. Contact Derm. 1989;20:379–380. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0536.1989.tb03178.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Hess A, Bloch W, Wittekindt C, Siodladczek J, Addicks K, Michel O. Immunohistochemical detection of vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF) and VEGF-receptors Flt-1 and KDR/Flk-1 in the vestibule of guinea pigs. Neurosci Lett. 2000;280:147–150. doi: 10.1016/S0304-3940(00)00774-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Ellis LM, Hicklin DJ. VEGF-targeted therapy: mechanisms of anti-tumour activity. Nat Rev Cancer. 2008;8:579–591. doi: 10.1038/nrc2403. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Hidalgo M, Rowinsky EK. The rapamycin-sensitive signal transduction pathway as a target for cancer therapy. Oncogene. 2000;19:6680–6686. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1204091. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Neufeld G, Cohen T, Gengrinovitch S, Poltorak Z. Vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF) and its receptors. FASEB J. 1999;13:9–22. doi: 10.1096/fasebj.13.1.9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Bruckner J, MacKenzie WF, Ramanathan R, Muralidhara S, Kim HJ, Dallas CE. Oral toxicity of 1,2-dichloropropane: acute, short-term, and long-term studies in rats. Fundam Appl Toxicol. 1989;12:713–730. doi: 10.1016/0272-0590(89)90003-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Fiaccadori E, Maggiore U, Rotelli C, Giacosa R, Ardissino D, De Palma G, Bergamaschi E, Mutti A. Acute renal and hepatic failure due to accidental percutaneous absorption of 1,2-dichlorpropane contained in a commercial paint fixative. Nephrol Dial Transplant. 2003;18:219–220. doi: 10.1093/ndt/18.1.219. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Kumagai S, Kurumatani N, Arimoto A, Ichihara G. Cholangiocarcinoma among offset colour proof-printing workers exposed to 1,2-dichloropropane and/or dichloromethane. Occup Environ Med. 2013;70:508–510. doi: 10.1136/oemed-2012-101246. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Kubo S, Nakanuma Y, Takemura S, Sakata C, Urata Y, Nozawa A, Nishioka T, Kinoshita M, Hamano G, Terajima H, Tachiyama G, Matsumura Y, Yamada T, Tanaka H, Nakamori S, Arimoto A, Kawada N, Fujikawa M, Fujishima H, Sugawara Y, Tanaka S, Toyokawa H, Kuwae Y, Ohsawa M, Uehara S, Sato KK, Hayashi T, Endo G. Case series of 17 patients with cholangiocarcinoma among young adult workers of a printing company in Japan. J Hepatobiliary Pancreat Sci. 2014;21:479–488. doi: 10.1002/jhbp.86. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Eliceiri BP, Paul R, Schwartzberg PL, Hood JD, Leng J, Cheresh DA. Selective requirement for Src kinases during VEGF-induced angiogenesis and vascular permeability. Mol Cell. 1999;4:915–924. doi: 10.1016/S1097-2765(00)80221-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Fadouloglou VE, Balomenou S, Aivaliotis M, Kotsifaki D, Arnaouteli S, Tomatsidou A, Efstathiou G, Kountourakis N, Miliara S, Griniezaki M, Tsalafouta A, Pergantis SA, Boneca IG, Glykos NM, Bouriotis V, Kokkinidis M. Unusual α-carbon hydroxylation of proline promotes active-site maturation. J Am Chem Soc. 2017;139:5330–5337. doi: 10.1021/jacs.6b12209. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Bae CJ, Shim SB, Jee SW, Lee SH, Kim MR, Lee JW, Lee CK, Hwang DY. IL-6, VEGF, KC and RANTES are a major cause of a high irritant dermatitis to phthalic anhydride in C57BL/6 inbred mice. Allergol Int. 2010;59:389–397. doi: 10.2332/allergolint.10-OA-0207. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Carmeliet P. Mechanisms of angiogenesis and arteriogenesis. Nat Med. 2000;6:389–395. doi: 10.1038/74651. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Cohen T, Nahari D, Cerem LW, Neufeld G, Levi BZ. Interleukin 6 induces the expression of vascular endothelial growth factor. J Biol Chem. 1996;271:736–741. doi: 10.1074/jbc.271.2.736. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Dutta PR, Maity A. Cellular responses to EGFR inhibitors and their relevance to cancer therapy. Cancer Lett. 2007;254:165–177. doi: 10.1016/j.canlet.2007.02.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Kumagai S, Kurumatani N, Arimoto A, Ichihara G. Cholangiocarcinoma among offset colour proofprinting workers exposed to 1,2-dichloropropane and/or dichloromethane. Occup Environ Med. 2013;70:508–510. doi: 10.1136/oemed-2012-101246. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Kudo S, Takemura S, Tanaka S, Shinkawa H, Kinoshita M, Hamano G, Ito T, Koda M, Aota T. Occupational cholangiocarcinoma caused by exposure to 1,2-dichloropropane and/or dichloromethane. Ann Gastroenterol Surg. 2018;2:99–105. doi: 10.1002/ags3.12051. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]