Abstract

Gay and bisexual Men Who Have Sex with Men (GBM) are sexually unique in that they can practice penile-anal sex versatility, i.e. engage in insertive and receptive anal sex. Individual-level versatility is extensively researched both as a sexual behavior linked to HIV/STI transmission, and as a GBM identity that can change over time. However, there is a dearth of research on event-level versatility (ELV), defined as taking the receptive and insertive role in the same sexual encounter. We analyzed event-level data from 644 GBM in the Momentum Health Study from February 2012-February 2017 to identify factors associated with ELV prevalence, the relationship between ELV and anal sex role preference, and sero-adaptive and sexualized drug use strategies. Univariate analysis revealed ELV prevalence rates between 15–20%. A multivariate generalized linear mixed model indicated ELV significantly (p<0.05) associated with versatile role preference and condomless sex. However, the majority of ELV came from GBM reporting insertive or receptive role preferences, and there was significantly higher condom use among sero-discordant partners, indicating sero-adaptation. Multivariate log-linear modeling identified multiple polysubstance combinations significantly associated with ELV. Results provide insights into GBM sexual behavior and constitute empirical data useful for future HIV/STI transmission pattern modeling.

Keywords: Anal sex versatility, gay and bisexual men, event-level analysis

Introduction

Gay and Bisexual Men (GBM) have the unique ability to practice penile-anal sex versatility, i.e. take both the insertive and receptive anal sex positions. Versatility constitutes both a sexual behavior with epidemiological ramifications and an important GBM identity role. In the former mathematical modeling and computer simulation studies consistently find versatility elevates HIV/STI transmission probabilities (Wiley & Herschkorn, 1989; Van Druten, Van Griensven, & Hendriks, 1992; Goodreau, Goichochea, & Sanshez, 2005; Beyrer et al., 2012; Cortes, 2018). For example, Goodreau, Goicochea, & Sanchez (2005) reported that their deterministic model of GBM sexual behavior featuring complete versatility would have twice the HIV prevalence in three decades compared to one allowing only insertive and receptive roles. Similarly, in the Beyrer et al. (2012) agent-based computer simulation program completely removing versatility reduced HIV incidence by 19–55%. These results reflect both biology and behavior. Overall, receptive anal sex has a higher probability of infection than insertive anal sex (Baggaley, White, & Boily, 2010; Meng et al., 2015; Baggaley et al., 2018). Beyrer et al. (2012, p. 368] succinctly outline the consequences of this differential for versatility, “Role reversal in MSMs, whereby individuals practice both insertive and receptive roles, helps HIV spread by overcoming the low transmission rates from receptive to insertive partners”.

In terms of identity, while most simulations and modeling exercises assumed fixed anal sexual roles, or role segregation, recent empirical studies delineate an array of personal and contextual variables influencing anal sex roles over the life course. These include age (Van Tieu et al., 2013), number of sexual partners (Lyons et al., 2011), income (Lyons, Pitts, & Gierson, 2013), ever using Pre-Exposure Prophylaxis (PrEP) (Dangerfield, Carmack, Gilreath, & Duncan, 2018), HIV-status (Hart, Wolitski, Purcell, Gomez, & Halkitis, 2003), ethnicity (Wei & Raymond, 2011; Dangerfield et al., 2018), relationship type (Pachankis, Buttenweiser, Bernstein, & Bayles, 2013) and psychological perceptions of power (Johns, Pingel, Eisenberg, Santana, & Bauermeister, 2012; Dangerfield, Smith, Williams, Unger & Bluthenhal, 2017) and gender (Moskowitz & Hart, 2011; Johns et al., 2012; Zheng, Hart & Zheng, 2015). As a result, previous descriptions of invariant anal sex roles, e.g. “tops”, “bottoms” and “versatiles” (Moskowitz, Rieger, & Roloff, 2008) now are modified to include terms like “mostly tops”, “mostly bottoms” or “versatile tops” (Pachankis, Buttenweiser, Bernstein, & Bayles, 2013; Tskhay, Re, & Rule, 2014).

Despite this history of versatility research, there is a dearth of studies focusing on event-level versatility (ELV), defined as having both insertive and receptive anal sex within the same sexual event, and colloquially known as “flip fucking”. That ELV is distinct from the more commonly measured period or individual-level versatility is exemplified in the Lyons et al. (2011) study of Australian GBM which found that 83% of participants were versatile over the past year, but only 20% reported versatility in their last sexual encounter. The first measure could include multiple partners and sexual events, while the second refers only to one event, and usually one partner. In an attempt to understand ELV more fully, we analyzed longitudinal event-level data, i.e. data describing behavior two hours before or during a sexual event (Leigh & Stall, 1993). Our rationale for focusing on ELV is three-fold. First, the recent modification of previously fixed anal sex roles, e.g. tops, bottoms, versatile, into terms like “mostly tops” or “versatile tops” suggests that ELV data may further help delineate relationships between preferred anal sex roles and realized anal sex behavior. These relationships may change over time, but not necessarily correspondingly. For example, Moskowitz and Hart (2011) found that identity and behavior corresponded strongly for men who identified as tops or bottoms.

However, this correspondence was far weaker for men identifying as versatiles, who were more likely to adopt the top or bottom sexual positions. Similarly, in a study of young sexual minority men, Pachankis, Buttenweiser, Bernstein, & Bayles (2013) reported that approximately half their sample changed their identity over a two-year time period, and that these changes did not correspond perfectly with sexual behavior. Event-level data analysis, using sexual encounters as the unit of analysis, has the potential to define this relationship more accurately than period measures, which may include different sexual partners and social contexts.

Secondly, event-level data may help identify sero-adaptive strategies, defined as potential harm reduction behaviors using HIV sero-status to inform sexual decision-making (Snowden, Raymond, & McFarland, 2011; Snowden, Wei, McFarland, & Raymond, 2014), and exemplified by condom use, sero-sorting, viral load sorting and sero-positioning (Card et al., 2017; Roth et al., 2018). Mathematical models of GBM versatility and HIV/STI transmission commonly focus on condomless anal sex without considering possible sero-adaptive strategies. ELV data could be particularly useful identifying sero-positioning among sero-discordant anal sex partners. In this strategy, HIV-positive GBM cognisant of both partners’ sero-status and differential HIV transmission probabilities would use condoms in the top, but not the bottom anal sex role. Thirdly, event-level data remain the gold standard for defining associations between substance use and sexual behavior (Gillmore et al., 2002; Colfax et al., 2004; Vosburgh, Mansergh, Sullivan, & Purcell, 2012; Rich et al., 2016; Yang et al., 2018). As such they are particularly valuable for research into GBM sexualized drug use (Knight, 2018, Tomkins, George, & Kliner, 2019), known as “Party ‘n Play” in North America and Australia (Race, 2015; Soulemaynov, 2017) and “Chemsex” in Europe (Weatherburn, Hickson, Reid, Torres-Rueda, & Bourne, 2016; Bakker & Knoops, 2018). Previous studies using individual-level data identified substances associated with specific anal sex behavior, e.g. erectile dysfunction drugs (EDD) and crystal methamphetamine with insertive anal sex (Mansergh et al., 2006; Lin, Mattson, Freedman, & Skarbinski, 2017) and poppers (amyl nitrites) with receptive anal sex (Drumright, Gorbach, Little, & Strathdee, 2009). However, event-level analyses on substance use and ELV remain rare (Rich et al., 2016), even though the majority of GBM self-identify as versatile (Hart et al., 2003). Given these possible research avenues, we analyzed longitudinal event-level GBM data to: 1) determine ELV prevalence rates over time, 2) identify socio-economic, sexual behavior, substance use, and psycho-social factors associated with ELV, and 3) delineate possible ELV sero-adaptive strategies and polysubstance use patterns. Due to the paucity of ELV studies we consider all analyses exploratory, and therefore do not pose or test specific hypotheses.

Methods and Materials

Materials

Study data come from the Momentum Health Study, a prospective cohort study of GBM health in Vancouver, British Columbia, Canada. Study participants were recruited using respondent driven sampling (Heckathorn, 1997) as described in previous publications (Lachowsky et al., 2016a; Card et al., 2017; Armstrong et al., 2018). Eligibility criteria included being 16 years of age or older, identifying as a man (including trans-men), having sex with another man in the previous 6 months, living in the Metro Vancouver Area, and being able to understand and complete a questionnaire in English. Eligible participants provided written informed consent, completed a computer-assisted self-interview questionnaire and biological tests including point-of-care HIV testing. They returned every six months to complete the same questionnaire and appropriate biological tests. This study used individual and event-level data collected from February 2012-February 2017. All study procedures received ethical approval from Simon Fraser University, the University of British Columbia, and the University of Victoria.

Analysis

At each visit participants completed a questionnaire section outlining event-level sexual behavior and substance use for themselves and up to five of their most recent sexual partners. This egocentric, or “one with many” design (Mustanski, Starks, & Newcomb, 2014) permitted quantification of sexual behavior, e.g. anal sex, oral sex, masturbation, sex toys, fisting, condom use, etc., as well as anal sex positioning. These last two factors were determined by participants marking responses describing anal position and the use, or non-use of condoms. Examples included “he fucked me without a condom” for receptive, condomless sex, and “I fucked him using a condom” for insertive anal sex with a condom. ELV was defined when participants checked two such boxes for the same partner and event. ELV prevalence levels for each six-month period were calculated and assessed for trend using the Cochran-Mantel-Haenszel Test. To identify variables significantly associated with ELV we used SAS® Version 9.4 PROC GLIMMIX to construct a longitudinal multivariate generalized linear mixed model accounting for respondent driven sampling chains, plus participant and visit clustering. This featured a backward stepwise selection technique that dropped the variable with the highest Type III p-value at each step of the selection process until the model reached the lowest Akaike Information Criterion (Lima et al., 2007). The model’s dependent variable was a dichotomous categorical dependent variable contrasting event-level insertive and/or receptive anal sex with ELV (insertive/receptive vs. ELV). We further used SAS® PROC GLIMMIX to provide univariate tests of sero-adaptive strategies, in particular sero-positioning and differential condom use among sero-discordant partners.

ELV polysubstance patterns were determined via multivariate log-linear models generated by SAS® PROC GENMOD. Log-linear models are analogous to correlational analysis in that they do not specify a dependent variable. Instead, they identify statistically significant associations between variables. In addition, log-linear models are hierarchal, with all higher-level interactions eliminated if not statistically significant, yielding the most parsimonious final model (Allison, 2012).

Measures

Independent variables comprised both individual-level and event-level measures. All individual-level questions referred to the past six months. These included participants’ age, ethnicity, education, HIV sero-status, annual income, residence, sexual orientation, and relationship status. For sexual orientation, 18 participants identified as transgender at baseline or over the study period. We wanted to include these men, some of whom recorded ELV. However, we wondered if all had the biological ability to engage in ELV. We used PROC GLIMMIX to complete univariate and multivariate longitudinal sensitivity analyses excluding transgender men. Results revealed very little statistical change in any independent variable from the sample including them, and no changes in statistical significance. Based on these results these men were included in the baseline and longitudinal samples. Individual-level sexual behavior questions asked if participants attended a group sex party, worked as an escort, used PrEP, and asked for their anal sex role preference (top, bottom, versatile). Individual-level psycho-social measures included revised Sensation Seeking Scales (Kalichman et al., 1994, study α =0.74) and HIV Treatment Optimism-Skepticism Scales (Van de Ven, Prestage, Crawford, Grulich, & Kippax, 2000, study a = 0.85), and the Alcohol Use Identification Test (AUDIT, Saunders, Aasland, Babor, De la Fuente, & Grant, 1993, study α =0.87). Event-level substance use questions consisted of yes/no responses to alcohol, cannabis, EDD, poppers, Ecstasy/MDMA, GHB, and crystal methamphetamine use within two hours before, or during a sexual event. Sexual behavior event-level questions asked how many months since participants first had sex with each specific partner, months since they last had sex with each partner, the number of people involved in each sexual event reported, and where they met their sexual partner(s). Transactional sex was also an event-level variable, with possible responses ranging from no goods, drugs, or money given or received, to all three commodities given or received. The final event-level variable considered condom use, with possible responses including: 1) condoms always used (ALWAYS), 2) condoms never used (NEVER), and 3) condoms used and not used (SOMETIMES) during a sexual event. These last responses recognize that a single sexual event may contain multiple anal sex acts, some condomless and others with condoms.

Results

Descriptive Sample Statistics

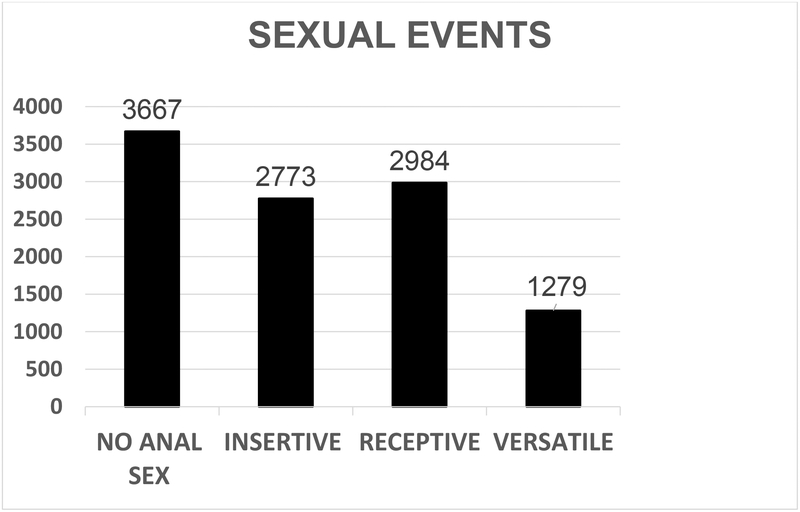

Over the study period, 644 men reported event-level anal sex. As shown in Table 1, the majority of these men self-identified as White (74.8%), and had completed more than high school (80%). Most study participants identified as gay (86.7%), resided in the Downtown Vancouver core (48.5%), and reported an annual income of <$30,000 (60.3%). Participants not having a regular sexual partner totaled 59.9%, 23.5% were in an open relationship, and 16.6% were married or in a monogamous relationship. HIV-positive participants totaled 29.3%. Their median age was 33 (Q1 – Q3 =26 – 46). We excluded 219 events reported by participants who did not consent to be part of the Momentum cohort, but only consented to an initial study visit. We omitted another six because of non-responses, leaving a final sample total of 10,703. As shown in Figure 1, 3,667 events recorded no anal sex. Removing them from analysis left a final baseline sample of 7,036 anal sex events, of which 1,279 were versatile, with the remaining 5,757 either receptive (2,984) or insertive (2,773).

Table 1.

Socio-demographic variables, total sample, n=644.

| Continuous Variables | ||

| Variable | Median | Q1–Q3 |

| Age | 33 | 26–46 |

| Treatment Optimism Scale | 25 | 21–29 |

| Sexual Sensation Seeking Scale | 31 | 28–34 |

| Categorical Variables | ||

| Variable | n. | % |

| Ethnicity | ||

| White | 482 | 74.8 |

| Asian | 67 | 10.4 |

| Indigenous | 37 | 5.8 |

| Other | 58 | 9.0 |

| Annual Income | ||

| <$30,00 | 388 | 60.3 |

| $30–59,999 | 176 | 27.3 |

| ≥$60,000 | 80 | 12.4 |

| Education | ||

| Completed high school or less | 129 | 20.0 |

| More than high school | 515 | 80.0 |

| Residence | ||

| Downtown Core | 312 | 48.5 |

| Vancouver | 208 | 32.3 |

| Greater Vancouver | 124 | 19.2 |

| Sexual Orientation | ||

| Gay | 558 | 86.7 |

| Bisexual | 45 | 7.0 |

| Other | 41 | 6.3 |

| HIV- Status | ||

| HIV-positive | 189 | 29.3 |

| HIV-negative | 455 | 70.7 |

| Relationship Status | ||

| Monogamous/Married | 107 | 16.6 |

| Open/Yes-Partially | 151 | 23.5 |

| No Regular Partner | 386 | 59.9 |

Figure 1.

Distribution of event-level sex acts, February 2012-February 2017.

Univariate and Multivariate Analyses

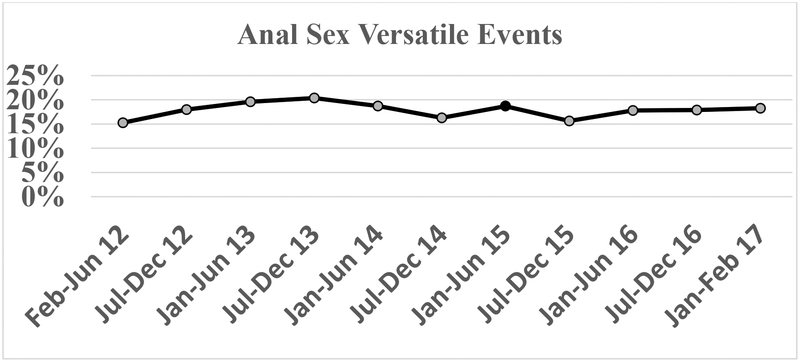

Figure 2 presents ELV prevalence rates for individual six-month intervals spanning the study period. ELV prevalence varied between 15%–20%, and the Cochran-Mantel-Haenszel Test generated a non-significant result (p=0.170) for trend analysis. Table 2 shows multivariate generalized linear mixed model results. For individual-level variables in the multivariate model, ELV was significantly associated with living in Vancouver (in contrast to the Downtown Core, aOR=1.32, 95%CI=1.04–1.67), and not being married or in a common law relationship, (aOR=1.34, 95%CI =1.01–1.78). In contrast, ELV was significantly negatively associated with age (aOR=0.85, 95%CI=0.75–0.95 per 10 years increase). Significant event-level variables in the multivariate model included reporting versatility as the preferred sexual role (aOR= 2.23, 95%CI =1.77–2.81), and using cannabis (aOR=1.43, 95%CI=1.16–1.76), EDD (aOR=1.90, 95%CI=1.43–2.52), and GHB (aOR=1.43, 95%CI=1.02–2.00) immediately before or during a versatile sexual event. Always using a condom (ALWAYS) was significantly, but negatively, associated with ELV (aOR = 0.50, 95%CI = 0.39–0.62), while using and not using a condom (SOMETIMES) was positively associated (aOR = 3.72, 95%CI = 2.79–4.97).

Figure 2.

Prevalence rates for anal sex versatility by six-month visit during study period.

Table 2.

Results for generalized linear mixed model, comparing versatile anal sex events with insertive and receptive anal sex events. Significant variables (p<.05) in bold. (OR=Odds Ratio, OR=Adjusted Odds Ratios, Not Selected = Not selected by AIC, EL=Event-level Variable)

| VARIABLE | Non-Versatile | Versatile | Univariate | Multivariate | ||||

| MD | MD | OR | aOR | |||||

| CONTINUOUS VARIABLES | ||||||||

| Age (per 10 year increase) | 35 | 33 | 0.88 | 0.85 | ||||

| Sexual Sensation Scale | 32 | 32 | 1.04 | Not Selected3 | ||||

| Treatment Optimism Scale | 27 | 27 | 0.99 | |||||

| Months Since 1st Sex (EL) per 12 months increase | 5 | 7 | 1.0 | Not Selected | ||||

| Months Since Most Recent Sex (EL) per 12 months increase | 1 | 1 | 0.87 | 0.92 | ||||

| CATEGORICAL VARIABLES | ||||||||

| N | N | OR | aOR | |||||

| Ethnicity | ||||||||

| White | 4395 | 976 | Ref. | |||||

| Asian | 594 | 113 | 0.78 | |||||

| Indigenous | 255 | 49 | 0.62 | |||||

| Latino/Other | 513 | 141 | 1.29 | |||||

| Education | ||||||||

| ≤ high school | 801 | 179 | Ref. | |||||

| > high school | 4925 | 1089 | 0.96 | |||||

| HIV Sero-status | ||||||||

| HIV negative | 3997 | 891 | Ref. | |||||

| HIV positive | 1760 | 388 | 1.00 | |||||

| Annual Income | ||||||||

| <$30,000 | 2871 | 675 | Ref. | Ref. | ||||

| $30,000-$59,999 | 1915 | 399 | 0.78 | 0.82 | ||||

| ≥$60,000 | 964 | 203 | 0.93 | 1.03 | ||||

| Neighborhood | ||||||||

| Downtown Core | 2963 | 605 | Ref. | Ref. | ||||

| Vancouver | 1625 | 428 | 1.28 | 1.32 | ||||

| Greater | 1169 | 246 | 0.97 | 1.05 | ||||

| Vancouver | ||||||||

| Sexual Orientation | ||||||||

| Gay | 5078 | 1134 | Ref. | |||||

| Bisexual | 305 | 69 | 1.07 | |||||

| Other | 374 | 76 | 1.04 | |||||

| Married | ||||||||

| Yes (includes common law) | 1111 | 241 | Ref. | Ref, | ||||

| No | 1130 | 303 | 1.30 | 1.34 | ||||

| No Regular Partner | 3516 | 735 | 1.13 | 1.20 | ||||

| Relationship | ||||||||

| Monogamous | 918 | 252 | Ref. | Not included-collinear with Married variable | ||||

| Open | 1318 | 289 | 0.78 | |||||

| No Regular Partner | 3516 | 735 | 0.83 | |||||

| Attended Sex Party | ||||||||

| No | 4110 | 919 | Ref. | |||||

| Yes | 1647 | 360 | 0.92 | |||||

| Worked as Escort | ||||||||

| No | 5437 | 1183 | Ref. | |||||

| Yes | 320 | 96 | 1.27 | |||||

| AUDIT Scores | ||||||||

| Low risk 0–7 | 3673 | 798 | Ref. | |||||

| Hazardous 8–15 | 1430 | 355 | 1.00 | |||||

| Harmful 16–19 | 281 | 60 | 0.87 | |||||

| Dependence ≥20 | 324 | 78 | 0.90 | |||||

| Used PrEP P6M | ||||||||

| No | 3397 | 749 | Ref. | |||||

| Yes | 88 | 17 | 0.85 | |||||

| Never heard of PrEP | 1990 | 457 | 1.04 | |||||

| Alcohol (EL)4 | ||||||||

| No | 3716 | 765 | Ref. | |||||

| Yes | 2041 | 514 | 1.14 | |||||

| Cannabis (EL) | ||||||||

| No | 4229 | 848 | Ref. | Ref. | ||||

| Yes | 1528 | 431 | 1.60 | 1.43 | ||||

| Poppers (EL) | ||||||||

| No | 4418 | 933 | Ref. | Not Selected | ||||

| Yes | 1339 | 346 | 1.25 | |||||

| Erectile Dysfunction Drugs (EL) | ||||||||

| No | 4986 | 1002 | Ref. | Ref. | ||||

| Yes | 771 | 277 | 2.03 | 1.90 | ||||

| GHB (EL) | ||||||||

| No | 5481 | 1161 | Ref. | Ref. | ||||

| Yes | 276 | 118 | 1.90 | 1.43 | ||||

| Ecstasy/MDMA (EL) | ||||||||

| No | 5567 | 1198 | Ref. | Not selected | ||||

| Yes | 190 | 81 | 1.78 | |||||

| Crystal Meth (EL) | ||||||||

| No | 5168 | 1099 | Ref. | Not selected | ||||

| Yes | 589 | 180 | 1.48 | |||||

| First Meet (EL) | ||||||||

| On-Line | 3231 | 647 | Ref. | Ref. | ||||

| Other | 2519 | 631 | 1.14 | 1.14 | ||||

| Transactional Sex (EL) | ||||||||

| No money/goods exchanged | 5531 | 1230 | Ref. | |||||

| Money/goods given | 77 | 13 | 0.75 | |||||

| Money/goods received | 132 | 32 | 1.03 | |||||

| Money/goods received and given | 16 | 4 | 1.03 | |||||

| Others Involved (EL) | ||||||||

| Dyad | 5052 | 1091 | Ref. | |||||

| Threesome | 518 | 128 | 0.99 | |||||

| Foursome | 92 | 35 | 1.35 | |||||

| Orgy | 94 | 25 | 1.16 | |||||

| Anal Sex Preference (EL) | ||||||||

| Bottom | 2218 | 379 | Ref. | Ref. | ||||

| Versatile | 1337 | 565 | 2.22 | 2.23 | ||||

| Top | 2160 | 331 | 0.91 | 0.93 | ||||

| No Anal Sex | 42 | 4 | 0.56 | 0.71 | ||||

| Condom Use (EL) | ||||||||

| 0=NEVER | 3106 | 744 | Ref. | Ref. | ||||

| 1=ALWAYS | 2395 | 315 | 0.47 | 0.50 | ||||

| 3=SOMETIMES | 256 | 220 | 3.91 | 3.72 | ||||

We further examined the differential condom use seen in Table 2 to identify ELV sero-adaptive strategies. Specifically, for receptive/insertive anal sex events using and not using a condom (SOMETIMES) comprised 4.4% of all events, compared to 17.2% for ELV, suggesting sero-positioning among sero-discordant partners. Likewise, the significant lower frequency in always using (ALWAYS) condom for EVL events suggested differential condom use based on sero-status. We used SAS® PROC GLIMMIX to provide a univariate test of both these strategies. Results presented in Table 3 showed that compared to never using condoms (NEVER), frequencies of ALWAYS and SOMETIMES using condoms were significantly higher for sero-discordant partners (ALWAYS OR = 3.06, 95%CI = 1.82–5.15, p<0.001, SOMETIMES OR = 1.73, 95%CI = 1.04–2.88, p =0.037) compared to sero-concordant partners, supporting our suggestion of the presence of sero-adaptive strategies.

Table 3.

Univariate GLIMMIX modeling the probability of “Sero-Discordant/Unknown” and condom use patterning for ELV events.

| Sero-concordant | Sero-Discordant/Unknown | Total | Univariate GLIMMIX | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Condom Use | N. | Col % | N. | Col % | N. | Odds Ratio | 95% CI | Prob. |

| NEVER | 436 | 64.7 | 308 | 50.9 | 744 | Ref. | ||

| ALWAYS | 129 | 19.1 | 186 | 30.7 | 315 | 3.06 | 1.82–5.15 | <0.001 |

| SOMETIMES | 109 | 16.2 | 111 | 18.4 | 220 | 1.73 | 1.04–2.88 | 0.037 |

| Total | 674 | 100.0 | 605 | 100.0 | 1279 | |||

Finally, to investigate ELV polysubstance use, SAS® PROC GENMOD produced an initial saturated multivariate log-linear model containing all main effects and interactions for every substance used in the PROC GLIMMIX analysis. However, this original log-linear model failed to converge. It did converge when we removed MDMA/Ecstasy, which was non-significant in the GLIMMIX multivariate model, and featured the lowest use frequency of all substances. Table 4 shows results of this analysis, presenting only combinations selected in the final model. These included multiple significant three-way and two-way interactions. Notable here is the three-way interaction between the three substances significantly associated with ELV in the GLIMMIX analysis, cannabis, EDD, and GHB (cannabis*EDD*GHB = aOR =2.04, 95%CI =1.23–3.37). Equally important, some interactions were significant and negatively associated with ELV (e.g. Poppers*GHB*Crystal, aOR=0.60, 95%CI =0.37–0.96, p=0.035), while others were significant and positively associated (e.g. EDD*Crystal, aOR=3.71, 95%CI=2.82–4.88, p <0.001).

Table 4.

Multivariate log-linear model results for substance main effects and interactions selected in the final model. Statistically significant variables (p<0.05) and interactions in bold.

| VARIABLES | ADJUSTED ODDS RATIOS | 95% CI | PROBABILITY |

|---|---|---|---|

| Alcohol | 0.45 | 0.42–0.48 | <0.001 |

| Cannabis | 0.16 | 0.15–0.18 | <0.001 |

| EDD | 0.08 | 0.07–0.09 | <0.001 |

| Poppers | 0.17 | 0.15–0.18 | <0.001 |

| GHB | 0.01 | 0.01–0.01 | <0.001 |

| Crystal | 0.04 | 0.03–0.04 | <0.001 |

| Alcohol*EDD | 0.84 | 0.69–1.03 | 0.092 |

| Alcohol* Crystal | 0.94 | 0.73–1.22 | 0.654 |

| Alcohol*Poppers | 0.89 | 0.77–1.02 | 0.100 |

| Alcohol*GHB | 1.41 | 0.93–2.13 | 0.105 |

| Alcohol*Cannabis | 2.78 | 2.47–3.14 | <0.001 |

| Cannabis*EDD | 2.14 | 1.75–2.63 | <0.001 |

| Cannabis*Poppers | 2.51 | 2.17–2.89 | <0.001 |

| Cannabis*GHB | 0.63 | 0.44–0.91 | 0.013 |

| Cannabis*Crystal | 2.70 | 2.10–3.48 | <0.001 |

| EDD*Poppers | 2.47 | 1.98–3.09 | <0.001 |

| EDD*GHB | 7.67 | 4.80–12.27 | <0.001 |

| EDD*Crystal | 3.71 | 2.82–4.88 | <0.001 |

| Poppers*GHB | 3.72 | 2.47–5.62 | <0.001 |

| Poppers*Crystal | 2.79 | 2.30–3.40 | <0.001 |

| GHB*Crystal | 33.97 | 21.98–52.49 | <0.001 |

| Alcohol*Cannabis*Crystal | 0.73 | 0.52–1.01 | 0.056 |

| Alcohol*GHB*Crystal | 0.69 | 0.39–1.04 | 0.069 |

| Alcohol*EDD*Poppers | 1.54 | 1.15–2.08 | 0.004 |

| Alcohol*EDD*GHB | 0.51 | 0.31–0.81 | 0.005 |

| Cannabis*EDD*Poppers | 0.74 | 0.55–0.99 | 0.044 |

| Cannabis *EDD*GHB | 2.04 | 1.23–3.37 | 0.006 |

| Cannabis *EDD*Crystal | 0.61 | 0.43–0.89 | 0.010 |

| EDD*GHB*Crystal | 0.35 | 0.22–0.57 | <0.001 |

| EDD*Poppers*GHB | 0.66 | 0.42–1.03 | 0.068 |

| Poppers*GHB*Crystal | 0.60 | 0.37–0.96 | 0.035 |

Discussion

Recent empirical studies indicate far more anal sex role variation over the life course of GBM than previously included in mathematical models of versatility. Despite this finding, we noted a dearth of studies on GBM event-level versatility, i.e. being both a bottom and a top in the same sexual encounter. Therefore, we analyzed longitudinal event-level data from GBM enrolled in the Momentum Health Study to: 1) determine ELV prevalence rates over time, 2) identify socio-economic, sexual behavior, substance use, and psychosocial factors significantly associated with ELV, and 3) identify possible ELV sero-adaptive strategies and polysubstance use patterns. For the first goal, analysis showed ELV prevalence rates ranged from 15% to 20% over the study period and Cochran-Mantel-Haenszel Trend Test results were non-significant. These prevalence levels agree closely with the 20% estimate reported by Lyons et al. (2011), based on last sexual event for Australian GBM.

For the second goal, multivariate analysis showed a significant association between having versatility as the preferred sexual role and ELV. At the same time, Table 2 showed that less than one-half of all ELV (n = 565/1,279, 44.2%) was recorded for men with this role preference. Table 2 also shows the distribution of preferred sex role for anal sex. As in the Moskowitz and Hart (2011) study, the correspondence between preferred role and actual behavior is stronger here, with 76% of these behavioral events reflecting preferred sex roles. These results also support recent studies showing that GBM anal sex roles are not fixed, but rather exhibit much more variation that previously thought, and in particular, previously modeled (Pachankis, Buttenweiser, Bernstein, & Bayles, 2013; Tskhay, Re, & Rule, 2014; Ravenhill & de Visser, 2018).

For the third goal, differential condom use frequencies suggested possible ELV sero-adaptive strategies. While ALWAYS using condoms was negatively associated with ELV, univariate analysis showing significantly higher levels of ALWAYS and SOMETIMES condom use relative to NEVER using condoms for ELV between sero-discordant partners indicated differential condom use based on sero-status disclosure and sero-positioning. Always using condoms in sero-discordant partnerships is particularly noteworthy in light of ELV having a significantly lower level of overall always using condoms compared to either insertive or receptive anal sex as shown in Table 2 (ALWAYS versatile = 24.6%, ALWAYS insertive/receptive=41.6%, aOR= 0.50, 95% CI = 0.39–0.62, p<0.001). While GBM sero-adaptive strategies research increasingly focuses on HAART or PrEP use (Mosley et al., 2018; Roth et al., 2018), contemporary studies also indicate that GBM do not abandon earlier strategies like condom use (Snowden, Wei, McFarland, & Raymond, 2014; Lachowsky et al., 2016b). As such, this study’s identification of two sero-adaptive strategies including condoms remains relevant to current HIV education and prevention programs (Otis et al., 2016; Beyrer et al., 2016).

Finally, multivariate results identified a new substance use pattern associated with ELV. Past analyzes of individual- and event-level data linked EDD and crystal methamphetamine to insertive anal sex and poppers to receptive anal sex (Rich et al., 2016). We therefore expected all three would be significantly associated with ELV. Instead, multivariate results showed EDD, cannabis, and GHB significantly associated with ELV, while poppers and crystal methamphetamine were not. We further explored this patterning via multivariate log-linear modeling. An alternative approach to quantifying GBM substance use patterns employs latent class analysis (Card et al., 2018; Carter et al., 2018; Dangerfield, Carmack, Gilreath & Duncan, 2018b), which has the advantage of including and analyzing associated socio-economic and demographic variables. However, all latent class analyses known to us use individual-level substance use reports with varying time intervals. In contrast, this study’s log-linear analysis used event-level data to identify substances used within two hours or during sexual events, providing a highly accurate measurement of GBM sexualized polysubstance use. We view this last analysis as an important, but preliminary step, with further research needed to place these results in context. For example, qualitative research on the central nervous system depressant gamma-hydroxybutyrate (GHB) among GBM revealed multiple reasons for its use including short effect duration, increased energy and libido, and limited after-effects (Palamar & Halkitis, 2006). At the same time, GBM recognize potential adverse health reactions associated with the drug, specifically coma and death resulting from too large a dose or mixing with other substances, particularly alcohol (Bourne, Reid, Hickson, Torres-Rueda, Steinberg, & Weatherburn, 2015). The negative adjusted odds ratios for some GHB-alcohol combinations shown in Table 4 (e.g. Alcohol*GHB*Crystal, aOR=0.69, 95%CI = 0.39–1.04, p=0.069, Alcohol*EDD*GHB= aOR=0.51, 95%CI =0.31–0.81 p = 0.005) might reflect GBM avoiding alcohol-GHB combinations. Alternatively, they may simply reflect substances at hand during a specific sexual event. As Melendez-Torres & Bourne (2016) note, despite two decades of research we still have more questions than answers about GBM substance use. In the future, combining event-level data with qualitative research stressing substance use combinations and their perceived functions could potentially address these questions by delineating specific substance use strategies, analogous to previous work on sero-adaptive sexual strategies.

Limitations and Strengths

This study has limitations. As with any research based on self-reports there may be desirability bias, with participants concerned about anticipated stigma associated with condomless anal sex or polysubstance use reporting lower values for these behaviors. However, self-administered questionnaires, such as our computer-based one, consistently yield more accurate sensitive data estimates than do interviewer-based questionnaires (Gnambs & Kaspar, 2015). A second consideration is that the widespread dissemination of HAART in the Vancouver Treatment as Prevention environment (Montaner et al., 2014) combined with low PrEP uptake during the study period (Lachowsky et al., 2016b; Mosley et al., 2018) means that these data are not representative of other areas with differing levels of HAART and PrEP use. In addition, we note that our findings are specific to North American GBM sexual culture and as such may differ significantly with versatility patterns found in South America, Asia and/or sub-Saharan Africa (Beyrer et al., 2012; Meng et al., 2015). Thirdly, although respondent driven sampling yields more robust population estimates, we do not claim that our final sample constitutes a representative sample.

While recognizing the above limitations, this longitudinal event-level data analysis achieved its goals in determining ELV prevalence, identifying factors associated with ELV, assessing variation between preferred role and actual behavior, and delineating sero-adaptation, and polysubstance use patterns. These findings can help understand recent findings of GBM anal sex role preference and anal sex behavior, and substance use decision-making as well as provide new data for future HIV/STI transmission mathematical modeling.

Acknowledgements

Disclosure Statement The co-authors acknowledge that they have no financial interest or benefit arising from the direct application of this research to disclose. All co-authors saw and approved the final version of this work.

Acknowledgements The authors are grateful for the assistance and involvement of Momentum Health Study participants, office staff and community advisory board, and our community partner agencies, the Health Initiative for Men, YouthCo HIV and Hep C Society, and the Positive Living Society of BC.

Funding Momentum funding is through the National Institute on Drug Abuse (Grant # R01DA031055–01A1) and the Canadian Institutes for Health Research (Grant # MOP-107544, 143342, PJT-153139). A CANFAR/CTN Postdoctoral Fellowship Award supported NJL. Scholar Awards from the Michael Smith Foundation for Health Research (#5209, #16863) support DMM and NJL. A Postdoctoral Fellowship Award from the Canadian Institutes of Health Research (Grant # MFE-152443) supports HLA. A Frederick Banting and Charles Best Doctoral Research Award from the Canadian Institutes of Health Research (#379361) supports AJR. KGC is supported by a University Without Walls/Engage Fellowship award, a Canadian HIV Trials Network/Canadian Foundation for AIDS Research Postdoctoral Fellowship award, a Michael Smith Foundation for Health Research Trainee Award.

Contributor Information

Lindsay Shaw, Canadian Institute for Substance Use Research, University of Victoria, Victoria, British Columbia, Canada.

Lu Wang, British Columbia Centre for Excellence in HIV/AIDS, Vancouver, British Columbia, Canada

Zishan Cui, British Columbia Centre for Excellence in HIV/AIDS, Vancouver, British Columbia, Canada.

Ashleigh J. Rich, University of British Columbia, Vancouver, British Columbia, Canada; British Columbia Centre for Excellence in HIV/AIDS, Vancouver, British Columbia, Canada.

Heather L. Armstrong, University of British Columbia, Vancouver, British Columbia, Canada, British Columbia Centre for Excellence in HIV/AIDS, Vancouver, British Columbia, Canada.

Nathan J. Lachowsky, School of Public Health and Social Policy, University of Victoria, Victoria, British Columbia, British Columbia Centre for Excellence in HIV/AIDS, Vancouver, British Columbia, Canada.

Paul Sereda, British Columbia Centre for Excellence in HIV/AIDS, Vancouver, British Columbia, Canada.

Kiffer G. Card, British Columbia Centre for Excellence in HIV/AIDS, Vancouver, British Columbia, Canada.

Gbolahan Olarewaju, British Columbia Centre for Excellence in HIV/AIDS, Vancouver, British Columbia, Canada

David Moore, Faculty of Medicine, University of British Columbia, Vancouver, British Columbia, Canada, British Columbia Centre for Excellence in HIV/AIDS, Vancouver, British Columbia, Canada

Robert Hogg, Faculty of Health Sciences, Simon Fraser University, British Columbia Centre for Excellence in HIV/AIDS, Vancouver, British Columbia, Canada.

Eric Abella Roth, Department of Anthropology, University of Victoria, Victoria, British Columbia, Canada.

References

- Allison P (2012). Logistic regression using SAS: Theory and application SAS Institute, Cary, NC: SAS Press; ISBN978–1–59994–641–2. [Google Scholar]

- Armstrong H, Roth E, Rich A, Lachowsky N, Cui Z, Sereda P, & Hogg R (2018). Associations between sexual partner number and HIV risk behaviors: implications for HIV prevention efforts in a Treatment as Prevention (TasP) environment. AIDS Care, 30, 1290–7. 10.1080/09540121.2018.1454583 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baggaley R, White R, & Boily M-C (2010). HIV transmission risk through anal intercourse: systematic review, meta-analysis and implications for HIV prevention. International Journal of Epidemiology, 39, 1048–63. 10.1093/ije/dyq057 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baggaley R, Owen B, Silhol R, Elmes J, Anton P McGowan I, van der Straten A, Shacklett B, Dang Q, Swann E, & Bolton D (2018). Does per-act HIV-1 transmission risk through anal sex vary by gender? An updated systematic review and meta-analysis. American Journal of Reproductive Immunology, 80:e13039 10.1111/aii.13039 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bakker I & Knoops L (2018). Towards a continuum of care concerning chemsex issues. Sexual Health, 15, 173–5. 10.1071/SH17139 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beyrer C, Baral S, Van Griensven F, Goodreau S, Chariyalertsak S, Wirtz A, & Brookmeyer R (2012). Global epidemiology of HIV infection in men who have sex with men. The Lancet, 380, 367–77. 10.1016/S0140-6736(12)60821-6 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beyrer C, Baral S, Collins C, Richardson E, Sullivan P, Sanchez J, & Wirtz A (2016). The global response to HIV in men who have sex with men. The Lancet, 388, 198–206. 10.1016/S0140-6736(16)30781-4 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bourne A, Reid D, Hickson F, Torres-Rueda S, Steinberg P, & Weatherburn P (2015). “Chemsex” and harm reduction need among gay men in South London. International Journal of Drug Policy, 26, 1171–6. 10.1016/j.drugpo.2015.07.013 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Card K, Lachowsky N, Cui Z, Sereda P, Rich A, Jollimore J, & Roth E (2017). Seroadaptive strategies of gay & bisexual men (GBM) with the highest quartile number of sexual partners in Vancouver, Canada. AIDS and Behavior, 21, 1452–66. 10.1007/s10461-016-1510-y [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Card K, Lachowsky N, Cui Z, Carter A, Armstrong H, Shurgold S, Moore D, Hogg R & Roth E (2018). A latent class analysis of seroadaptation among gay and bisexual men. Archives of Sexual Behavior, 47, 95–106. 10.1007/s10508-016-0879-z [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carter A, Roth E, Ding E, Milloy M-J, Kestler M, Jabbari S, & Kaida A (2018). Substance use, violence, and antiretroviral adherence: a latent class analysis of women living with HIV in Canada. AIDS and Behavior, 22, 971–85. 10.1007/s10461-017-1863-x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Colfax G, Vittinghoff E, Husnik M, McKirnan D, Buchbinder S, Koblin B, & Bozeman S (2004). Substance use and sexual risk: a participant-and episode-level analysis among a cohort of men who have sex with men. American Journal of Epidemiology, 159, 1002–12. 10.1093/aje/kwh135 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cortés A (2018). On how role versatility boosts an STI. Journal of Theoretical Biology, 440, 66–9. 10.1016/j.jtbi.2017.12.018 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dangerfield D, Smith L, Williams J, Unger J, & Bluthenthal R (2017). Sexual positioning among men who have sex with men: a narrative review. Archives of Sexual Behavior, 46, 869–84. 10.1007/s10508-016-0738-y [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dangerfield D, Carmack C, Gilreath T, & Duncan D (2018). Latent classes of sexual positioning practices and sexual risk among Men Who Have Sex with Men in Paris, France. AIDS and Behavior, 22, 4001–8. 10.1007/s10461-018-2267-2 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dangerfield D, Smith L, Anderson J, Bruce O, Farley J & Bluthenthal R (2018). Sexual positioning practices and sexual risk among Black gay and bisexual men: A life course perspective. AIDS and Behavior, 22, 1919–31. 10.1007/s10461-017-1948-6 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Drumright L, Gorbach P, Little S, & Strathdee S (2009). Associations between substance use, erectile dysfunction medication and recent HIV infection among men who have sex with men. AIDS and Behavior, 13, 328–33. 10.1007/s10461-007-9330-8 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gillmore M, Morrison D, Leigh B, Hoppe M, Gaylord J, & Rainey D (2002). Does “high= high risk”? An event-based analysis of the relationship between substance use and unprotected anal sex among gay and bisexual men. AIDS and Behavior, 6, 361–70. 10.1023/A:1021104930612 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Gnambs T & Kaspar K (2015). Disclosure of sensitive behaviors across self-administered survey modes: a meta-analysis. Behavior Research Methods, 47, 1237–59. 10.3758/s13428-014-0533-4 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goodreau S, Goicochea L, & Sanchez J (2005). Sexual role and transmission of HIV Type 1 among men who have sex with men, in Peru. The Journal of Infectious Diseases, 191, S147–58. 10.1086/425268 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hart T, Wolitski R Purcell D, Gomez C, & Halkitis P (2003) Seropositive Urban Men’s Study Team. Sexual behavior among HIV-positive men who have sex with men: What’s in a label? Journal of Sex Research, 40, 179–88. 10.1080/00224490309552179 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Heckathom D (1997). Respondent-driven sampling: A new approach to the study of hidden populations. Social Problems, 44, 174–99. 10.2307/3096941 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Johns M, Pingel E, Eisenberg A, Santana M, & Bauermeister J (2012). Butch tops and femme bottoms? Sexual positioning, sexual decision-making, and gender roles among young gay men. American Journal of Men’s Health, 6, 505–18. https://doi.org/10.1177%2F1557988312455214 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kalichman S, Johnson J, Adair V, Rompa D, Multhauf K, & Kelly J (1994). Sexual sensation seeking: Scale development and predicting AIDS-risk behavior among homosexually active men. Journal of Personality Assessment, 2, 385–97. 10.1207/s15327752jpa62031 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Knight R (2018). Investments in implementation science are needed to address the harms associated with the sexualized use of substances among gay, bisexual and other men who have sex with men. Journal of the International AIDS Society, 21, e25141. doi: 10.1002/jia2.25141 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lachowsky N, Lin S, Hull M, Cui Z, Serada P, Jollimore J, Rich A, Montaner J, Roth E, Hogg R, & Moore D (2016a). Pre-exposure prophylaxis awareness among gay and other men who have Sex with men in Vancouver, British Columbia, Canada. AIDS and Behavior, 20, 1408–22. 10.1007/s10461-016-1319-8 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lachowsky N, Tanner Z, Cui Z, Sereda P, Rich A, Jollimore J, Montaner J, Hogg R, Moore D & Roth E (2016b). An Event-Level analysis of condom use during anal intercourse among self-reported Human Immunodeficiency Virus-negative gay and bisexual men in a Treatment as Prevention Environment. Sexually Transmitted Diseases, 43, 765–70. https://dx.doi.org/10.1097%2FOLQ.0000000000000530 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leigh B & Stall R (1993). Substance use and risky sexual behavior for exposure to HIV: Issues in methodology, interpretation, and prevention. American Psychologist, 48, 1035–45. https://psycnet.apa.org/doi/10.1037/0003-066X.48.10.1035 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lima V, Geller J, Bangsberg D, Patterson T, Daniel M, Kerr T, & Hogg R (2007). The effect of adherence on the association between depressive symptoms and mortality among HIV-infected individuals first initiating HAART. AIDS, 21, 1175–83. 10.1097/QAD.0b013e32811ebf57 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lin X, Mattson C, Freedman M, & Skarbinski J (2017). Erectile dysfunction medication prescription and condomless intercourse in HIV-infected Men Who have Sex with Men in the United States. AIDS and Behavior, 21, 1129–37. 10.1007/s10461-016-1552-1 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lyons A, Pitts M, & Grierson J (2013). Versatility and HIV vulnerability: Patterns of insertive and receptive anal sex in a national sample of older Australian gay men. AIDS and Behavior, 17, 1370–7. 10.1007/s10461-012-0332-9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lyons A, Pitts M, Smith G, Grierson J, Smith A, McNally S & Couch M (2012). Versatility and HIV vulnerability: investigating the proportion of Australian gay men having both insertive and receptive anal intercourse. The Journal of Sexual Medicine, 8, 2164–71. 10.1111/j.1743-6109.2010.02197.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mansergh G, Shouse R, Marks G, Guzman R, Roder M, Buchbinder S & Colfax G (2006). Methamphetamine and sildenafil (Viagra) use are linked to unprotected receptive and insertive anal sex, respectively, in a sample of men who have sex with men. Sexually Transmitted Infections, 82, 131–4. 10.1136/sti.2005.017129 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Melendez-Torres G & Bourne A (2016). Illicit drug use and its association with sexual risk behavior among MSM: more questions than answers? Current Opinion in Infectious Diseases, 29, 58–63. DOI: 10.1097/QCO.0000000000000234 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Meng X, Zou H, Fan S, Zheng B, Zhang L, Dai X, & Lu B (2015). Relative risk for HIV infection among men who have sex with men engaging in different roles in anal sex: a systematic review and meta-analysis on global data. AIDS and Behavior, 19, 882–9. 10.1007/s10461-014-0921-x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Montaner J, Lima V, Harrigan P, Lourengo L, Yip B, Nosyk B, & Hogg R (2014). Expansion of HAART coverage is associated with sustained decreases in HIV/AIDS morbidity, mortality and HIV transmission: the “HIV Treatment as Prevention” experience in a Canadian setting. PloS one. 9(2), e87872. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0087872 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moskowitz D & Hart T (2011). The influence of physical body traits and masculinity on anal sex roles in gay and bisexual men. Archives of Sexual Behavior, 40, 835–41. 10.1007/s10508-011-9754-0 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moskowitz D, Rieger G, & Roloff M (2008). Tops, bottoms and versatiles. Sexual and Relationship Therapy, 23, 191–202. 10.1080/14681990802027259 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Mosley T, Khaketla M, Armstrong H, Cui Z, Sereda P, Lachowsky N, Hull M, Olarewaju G, Jollimore J, Edward J & Montaner J (2018). Trends in awareness and use of HIV PrEP among gay, bisexual, and other Men who have Sex with Men in Vancouver, Canada 2012–2016. AIDS and Behavior, 22, 3550–65. 10.1007/s10461-018-2026-4 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mustanski B, Starks T, & Newcomb M (2014). Methods for the design and analysis of relationship and partner effects on sexual health. Archives of Sexual Behavior, 43, 21–33. 10.1007/s10508-013-0215-9 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Otis J, McFadyen A, Haig T, Blais M, Cox J, Brenner B, & Spot Study Group. (2016). Beyond condoms: risk reduction strategies among gay, bisexual, and other men who have sex with men receiving rapid HIV testing in Montreal, Canada. AIDS and Behavior, 20, 2812–26. 10.1007/s10461-016-1344-7 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pachankis J, Buttenwieser I, Bernstein L, & Bayles D (2013). A longitudinal, mixed methods study of sexual position identity, behavior, and fantasies among young sexual minority men. Archives of Sexual Behavior, 42, 1241–53. 10.1007/s10508-013-0090-4 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Palamar J & Halkitis P (2006). A qualitative analysis of GHB use among gay men: Reasons for use despite potential adverse outcomes. International Journal of Drug Policy, 17, 23–8. 10.1016/j.drugpo.2005.11.002 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Race K (2015). ‘Party and Play’: Online hook-up devices and the emergence of PNP practices among gay men. Sexualities, 8, 253–75. https://doi.org/10.1177%2F1363460714550913 [Google Scholar]

- Ravenhill J & de Visser R (2018). “It takes a man to put me on the bottom”: Gay men’s experiences of masculinity and anal intercourse The Journal of Sex Research, 55, 1033–47. doi: 10.1080/00224499.2017.1403547 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rich A, Lachowsky N, Cui Z, Sereda P, Lal A, Moore D, & Roth E (2016). Event-level analysis of anal sex roles and sex drug use among gay and bisexual men in Vancouver, British Columbia, Canada. Archives of Sexual Behavior, 45, 1443–51. 10.1007/s10508-015-0607-0 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Roth E, Cui Z, Rich A, Lachowsky N, Sereda P, Card K, Jollimore J, Howard T, Armstrong H, Moore D, & Hogg R (2018). Seroadaptive strategies of Vancouver gay and bisexual men in a Treatment as Prevention environment. Journal of Homosexuality, 65, 524–39. 10.1080/00918369.2017.1324681 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Saunders J, Aasland O, Babor T, De la Fuente J, & Grant M (1993). Development of the alcohol use disorders identification test (AUDIT). WHO collaborative project on early detection of persons with harmful alcohol consumption-II. Addiction, 88, 791–804. 10.1111/j.1360-0443.1993.tb02093.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Snowden J, Raymond H, & McFarland W (2011). Seroadaptive behaviors among men who have sex with men in San Francisco: the situation in 2008. Sexually Transmitted Infections, 87, 162–4. 10.1136/sti.2010.042986 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Snowden J, Wei C, McFarland, & Raymond H (2014). Prevalence, correlates and trends in seroadaptive behaviours among men who have sex with men from serial cross-sectional surveillance in San Francisco, 2004–2011. Sexually Transmitted Infections, 90, 498–504. 10.1136/sextrans-2013-051368 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Souleymanov R (2017). Sexual and drug-related practices of queer Men Who Party-N-Play. The Journal of Sexual Medicine, (5): e251 10.1016/j.jsxm.2017.04.244 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Tomkins A, George R, & Kliner M (2019). Sexualised drug taking among men who have sex with men: a systematic review. Perspectives in Public Health, 139, 23–33. https://doi.org/10.1177%2F1757913918778872 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tskhay K, Re D, & Rule N (2014). Individual differences in perceptions of gay men’s sexual role preferences from facial cues. Archives of Sexual Behavior, 43, 1615–20. 10.1007/s10508-014-0319-x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Van de Ven P, Prestage G, Crawford J, Grulich A, & Kippax S (2000). Sexual risk behavior increases and is associated with HIV optimism among HIV-negative and HIV-positive gay men in Sydney over the 4-year period to February 2000. AIDS, 14, 2951–3. 10.1097/00002030-200012220-00023 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Van Druten H, Van Griensven F, & Hendriks J (1992). Homosexual role separation: implications for analyzing and modeling the spread of HIV. Journal of Sex Research, 29, 477–99. 10.1080/00224499209551663 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Van Tieu H, Li X, Donnell D, Vittinghoff E, Buchbinder S, Parente Z, & Koblin B (2013). Anal sex role segregation and versatility among men who have sex with men: EXPLORE Study. Journal of Acquired Immune Deficiency Syndromes (1999), 64, 121–5. https://dx.doi.org/10.1097%2FQAI.0b013e318299cede [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vosburgh H, Mansergh G, Sullivan P, & Purcell D (2012). A review of the literature on event-level substance use and sexual risk behavior among men who have sex with men. AIDS and Behavior, 16, 1394–1410. 10.1007/s10461-011-0131-8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weatherburn P, Hickson F, Reid D, Torres-Rueda S, & Bourne A (2016). Motivations and values associated with combining sex and illicit drugs (‘chemsex’) among gay men in South London: findings from a qualitative study. Sexually Transmitted Infections, 12, sextrans-2016. 10.1136/sextrans-2016-052695 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wei C & Raymond H (2011). Preference for and maintenance of anal sex roles among men who have sex with men: Sociodemographic and behavioral correlates. Archives of Sexual Behavior, 40, 829–34. 10.1007/s10508-010-9623-2 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wiley J & Herschkorn S (1989). Homosexual role separation and AIDS epidemics: insights from elementary models. Journal of Sex Research, 26, 434–49. 10.1080/00224498909551526 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Yang C, Latkin C, Tobin K, Seal D, Koblin B, Chander G, Siconolfi D, Flores S, & Spikes P (2018) An event-level analysis of condomless anal intercourse with a HIV-discordant or HIV status-unknown partner Among Black Men Who Have Sex with Men from a multi-site study. AIDS and Behavior, 22, 2222–34. 10.1007/s10461-018-2161-y [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zheng L, Hart T, & Zheng Y (2015). Top/bottom sexual self-labels and empathizing-systemizing cognitive styles among gay men in China. Archives of Sexual Behavior, 44, 1431–8. 10.1007/s10508-014-0475-z [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]