Abstract

Introduction:

Avoidant coping plays an important role in the maintenance of post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD). However, existing investigations have been limited in their assessment of coping as a static process – despite evidence that the coping strategies individuals use to manage stressors vary across time and contexts. Further, research has relied on cross-sectional designs, precluding determination of the directionality of the negative affect-avoidant coping association. The current study addresses these limitations by using a daily diary method to examine the moderating role of PTSD symptom severity on reciprocal relations between negative affect and avoidant coping.

Methods:

Participants were 1,188 trauma-exposed adults (M age = 19.2, 56% female, 79% White) who provided daily diary data for 30 days via online surveys. Multi-level models were tested to evaluate the moderating role of PTSD symptom severity in the daily relations between negative affect and avoidant coping during the 30-day period.

Results:

Levels of daytime negative affect were assoicated with use of evening avoidant coping. Use of evening avoidant coping were associated with levels of next-day daytime negative affect. PTSD symptom severity moderated these relations. For individuals with more (vs. less) severe PTSD symptoms, the association of negative affect to avoidant coping was weaker and the association of avoidant coping to negative affect was stronger.

Limitations:

Findings must be interpreted in light of limitations, including self-report measures and assessment of a alcohol using sample of college students.

Discussion:

These findings advance our understanding of the negative affect-avoidant coping association among trauma-exposed individuals.

Keywords: post-traumatic stress disorder, trauma, avoidant coping, negative affect, bi-directional, reciprocal, daily dairy study

Post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD) is a serious and debilitating psychiatric disorder characterized by intrusions, effortful avoidance of external and internal trauma-related cues, negative alterations in cognitions and mood (NACM), and alterations in arousal and reactivity (AAR) following traumatic experiences (American Psychiatric Association [APA], 2013). PTSD is highly prevalent, with lifetime, past 12-month and past 6-month rates in the general population of 8.3%, 4.7%, and 3.8%, respectively (Kilpatrick et al., 2013). Further, PTSD is linked to a wide range of physical (e.g., chronic pain; Pacella, Hruska, & Delahanty, 2013), psychological (e.g., depression; Rytwinski, Scur, Feeny, & Youngstrom, 2013), and behavioral health (e.g., substance use; Tull, Weiss, & McDermott, 2015) concerns, as well as impairment in functioning, even among individuals who do not meet full PTSD diagnostic criteria (Hellmuth, Jaquier, Swan, & Sullivan, 2014). Thus, investigations that improve our understanding of the development and maintenance of PTSD have clear clinical relevance and public health significance.

The strategies individuals use to cope with stressors may characterize risk for PTSD following traumatic exposure. Coping refers to purposeful efforts to manage internal and external stressors that are appraised as taxing or exceed one’s resources (Lazarus & Folkman, 1984). A review by Skinner, Edge, Altman, and Sherwood (2003) indicated that the most frequent approach for discriminating among the types of coping is by categorizing such attempts as approach (i.e., behaviors that are directed toward threat including problem solving or seeking support) or avoidant (i.e., behaviors that are directed away from threat including denial or behavioral avoidance). While there are some immediate benefits to avoidant coping (e.g., stress reduction, dosing of threat; Roth & Cohen, 1986), a growing body of research suggests that this type of coping in particular has a deleterious impact on post-trauma outcomes (for reviews, see Aldwin & Yancura, 2004; Olff, Langeland, & Gersons, 2005; Roth & Cohen, 1986).

PTSD is characterized by avoidance of trauma-related internal (e.g., thoughts, emotions) and external (e.g., people, places) cues. Thus, individuals with PTSD may use avoidant coping more frequently as a means of managing their PTSD symptoms and related distress. Moreover, over time, individuals with PTSD may be motivated to use this strategy to cope with other types of experiences, including negative affect stemming from non-trauma-related internal and external events, given evidence that avoidant coping is reinforcing (Fischer, Smith, Spillane, & Cyders, 2005). Consistent with these assertions, more frequent use of avoidant coping has been shown to be associated with greater PTSD symptom severity (e.g., Dempsey, Stacy, & Moely, 2000; Krause, Kaltman, Goodman, & Dutton, 2008; Pineles et al., 2011). For instance, a longitudinal study of female victims of partner violence found that baseline levels of avoidant coping predicted PTSD symptom severity at one-year follow-up, even after controlling for baseline symptoms and covariates (e.g., revictimization; Krause et al., 2008). Likewise, Pineles et al. (2011) found that female victims of assault who reported greater use of avoidant coping at baseline (i.e., within one month of their assault) had greater PTSD symptom severity three months post-assault. Avoidant coping also has been shown to predict response to PTSD treatment. For instance, Boden, Bonn-Miller, Vujanovic, and Drescher (2012) found that decreases in avoidant coping from pre- to post-treatment were associated with lower PTSD symptom severity following residential treatment for PTSD. These findings are consistent with theoretical accounts of PTSD that have proposed that avoidant coping interferes with psychological mechanisms that underlie PTSD, including the emotional processing of traumatic memories, habituation to the aversive emotions associated with these memories, and extinction of trauma-related fear responses (Foa & Kozak, 1986; Foa & Rothbaum, 1998; Keane & Barlow, 2002). Thus, the natural recovery process may be thwarted among individuals who engage in greater avoidance of trauma memories or reminders (Foa & Kozak, 1986).

The aforementioned litertaure suggests that the strength of the association between negative affect and avoidant coping may be stronger among individuals with PTSD. Specifically, it shows that truama-exposed individuals who use avoidant coping to manage negative affect experience more PTSD symptoms post-trauma and show fewer improvements in PTSD symptoms following treatment. The current study extends existing research in this area by examining the potential moderating role of PTSD symptom severity on daily, bi-directional relations between negative affect and avoidant coping among trauma-exposed individuals. Specifically, two important gaps in the current literature were addressed. First, while a plethora of studies have examined coping as a dynamic process in everyday life (for reviews, see Litt, Tennen, & Affleck, 2010; Park & Iacocca, 2014; Tennen, Affleck, Armeli, & Carney, 2000), a dearth of research has assessed the impact of PTSD on individuals’ use of avoidant coping in their natural environments. Coping is a dynamic process – the specific strategies used to manage stressors can vary across time and contexts for an individual (Frydenberg, 2014; Lazarus & Folkman, 1984; Revenson & Lepore, 2012). Thus, to understand nuances in the association between negative affect and avoidant coping among trauma-exposed individuals with varying levels of PTSD symptom severity, it is critical that researchers employ methods that allow for examination of how this relation unfolds day to day. Micro-longitudinal methods capture data frequently and in near real-time, and assess experiences and behaviors as they unfold in their natural environment – which is critical to examining within-person, proximal relationships (Bolger & Laurenceau, 2013; Tennen et al., 2000). As such, these methods are vastly superior to cross-sectional and traditional longitudinal designs in that they reduce recall error and bias (participants are only asked to recall up to 24 hours in micro-longitudinal designs versus up to months or even years in cross-sectional and traditional longitudinal designs). Moreover, these methods allow for examination of rapid changes in behavior, not possible with cross-sectional and traditional longitudinal designs. Notably, micro-longitudinal methods have demonstrated validity and reliability in the study of psychological phenomena including affect and coping (for a review, see Csikszentmihalyi, 2014).

Second, much of the research in this area has relied on cross-sectional designs, so little is known about the directionality of association between negative affect and avoidant coping among trauma-exposed individuals with varying levels of PTSD symptom severity. Historically, coping has been viewed (and empirically tested) as a response to emotion. However, there is evidence that the relation between negative affect and avoidant coping is bi-directional, with each affecting the other (Folkman & Lazarus, 1988b). Specifically, negative affect has been theorized to influence succeeding avoidant coping through motivation or impediment mechanisms, which in turn alter the person-environment relationship, resulting in changes in the quality (e.g., intensity, duration) of negative affect (Folkman & Lazarus, 1988a). Because higher intensity of negative affect is more difficult to modulate (Mennin, Heimberg, Turk, & Fresco, 2005), individuals may be more likely to use strategies that function to immediately alleviate these emotional experiences, such as avoidant coping (Roth & Cohen, 1986). Additionally, it is possible that heightened levels of negative affect may increase the likelihood of using coping strategies that require fewer cognitive resources, such as avoidant coping (Kool, McGuire, Rosen, & Botvinick, 2010). For instance, although the exact mechanisms are unknown (Grandey, Frone, Melloy, & Sayre, in press; Inzlicht & Schmeichel, 2012), there is some evidence that high levels of negative affect may reduce one’s capacity for self-control (e.g., adaptive coping).

While understudied relative to the unidirectional link from negative affect to avoidant coping, initial empirical work also provides support for a bi-directional relation of avoidant coping to negative affect (e.g., Dickson, Ciesla, & Reilly, 2012; Fagundes, Berg, & Wiebe, 2012). For instance, laboratory studies have found that avoidant coping is less effective at diminishing negative affect than coping strategies that require individuals to approach their emotions such as acceptance (Campbell-Sills, Barlow, Brown, & Hofmann, 2006; Dan-Glauser & Gross, 2015; Tull, Jakupcak, & Roemer, 2010). Moreover, avoidant coping has been shown to result in persistence of negative affect post-event compared to acceptance (Campbell-Sills et al., 2006), consistent with the suggestion that avoidant coping may be followed by a rebound in distress (Hayes et al., 1996). Yet, research on the bi-directional effect is scarce, and has yet to test whether this association varies as a function of PTSD symptom severity, despite evidence for a relation between PTSD and both negative affect (Miller, Kaloupek, Dillon, & Keane, 2004; Miller & Resick, 2007) and avoidant coping (Dempsey et al., 2000; Krause et al., 2008; Pineles et al., 2011). Such findings would inform intervention efforts for trauma-exposed populations.

Addressing these limitations of prior research, the present study utilized daily diary data collected over 30 days among 1,640 college students to test whether (a) daytime negative affect influences the likelihood of evening avoidant coping, and (b) evening avoidant coping influences the likelihood of next-day negative affect, as well as the moderating role of PTSD symptom severity in these bi-directional associations. We hypothesized bi-directional relations such that (a) levels of daytime negative affect would influence the likelihood of evening avoidant coping, and (b) evening avoidant coping would influence the likelihood of levels of next-day negative affect. We expected that PTSD symptom severity would moderate these relations, such that they would be stronger among individuals with greater PTSD symptom severity.

Methods

Participants

Undergraduate psychology students were recruited as part of a project examining daily experiences and alcohol use. Eligibility criteria were: (a) ≥18 years of age, (b) alcohol use at least twice in the past 30 days, and (c) no past treatment for alcohol problems. The final sample included 1,640 students. This subsample was restricted to individuals who reported a history of traumatic exposure (n = 1,188); a traumatic exposure prevalence rate of 65% is consistent with past research in this population (e.g., 67% using DSM-IV PTSD criteria; Elhai et al., 2012). A little over half (55.7%) of the participants were female and the average age was 19.24 (SD=1.54). In terms of race/ethnicity, 79% were White, 12% Asian American, 4% Black, 4% Latino/a, and 1% Native American or other.

Procedures

Procedures were approved by the institutional review board at the University of Connecticut. Students were recruited through the undergraduate psychology participant pool and an email-based campus-wide announcements system. Students provided informed consent and completed an online baseline survey assessing demographics (e.g., gender, age, race/ethnicity) and a variety of behavioral and personality measures (e.g., lifetime traumatic exposure, baseline PTSD symptom severity). Students were then instructed to provide daily diary data for 30 days via online surveys, available from a secure website between 2:30pm and 7:00pm. Our reporting time window was selected to coincide with naturally occurring end of regularly scheduled academic activities, but before typical evening activities begin (including drinking). Surveys assessed behaviors ―since waking until the time of the report‖ (daytime) and ―since completing yesterday’s survey until you fell asleep‖ (i.e., evening) to cover the entire daily period.

Daily Measures

Negative Affect.

Negative affect items were extracted from the Positive and Negative Affect Schedule – Expanded Form (Watson & Clark, 1999). Negative affect items included: “nervous, “ “irritable, “ “hostile, “ “guilty, “ “sad, “ “ashamed, “ and “angry. “ Items were rated from 1 (not at all) to 5 (extremely) and were averaged to create daily negative affect scores. Participants were asked to report on daytime and evening negative affect. This subscale had good internal consistency in the current sample (ω = .93).

Avoidant coping.

Given the intensive nature of daily data collection, to reduce participant burden, and consistent with recommendations for daily data methods (Stone & Shiffman, 2002; Stone, Shiffman, Alienza, & Nebeling, 2007), avoidant coping was measured by asking a single item (“I avoided dealing with a situation”), rated from 0 (not at all) to 3 (a lot). Participants were asked to report on evening avoidant coping in response to any stressful events or experiences.

Baseline Measures

Demographic questionnaire.

Information regarding age, gender, and racial/ethnic status was obtained.

Trauma exposure.

The Traumatic Experiences Screening Instrument (TESI; Ford et al., 2000) is an 18-item, self-report measure designed to screen for trauma events in a respondent’s lifetime. Consistent with DSM-IV guidelines for determining Criterion A trauma exposure for PTSD, participants were asked only to endorse an event if it elicited fear, helplessness, or horror. The TESI has shown evidence of adequate reliability and validity. Individuals who endorsed at least one trauma event on the TESI were classified as “trauma-exposed.” TESI items have shown evidence of retest reliability (.50–.70) and criterion and predictive validity (Ford et al., 2000).

PTSD symptom severity.

The PTSD Checklist–Civilian Version (PCL-C; Weathers, Litz, Herman, Huska, & Keane, 1993) is a 17-item self-report measure of the severity of PTSD symptoms experienced in response to a stressful life event among civilians, as outlined by DSM-IV (APA, 1994) criteria for PTSD. Using a 5-point Likert-type scale anchored from 1 = not at all to 5 = extremely, participants rate the extent to which each symptom has bothered them in the past month. The PCL-C has excellent internal consistency and test–retest reliability in college students (Ruggiero, Del Ben, Scotti, & Rabalais, 2003). Internal consistency in this sample was excellent (ω = .94).

Data Analysis

A series of multi-level models were tested using R version 3.4.1 software (R Core Team, 2017) to evaluate daily bi-directional associations of negative affect and avoidant coping during the 30-day period. Daily reports (n = 33,513) comprised of level-1 variables nested within person at level-2 (n = 1,188). Multi-level modeling allows us to estimate within-person relations among negative affect and avoidant coping on a daily level while considering how these effects vary by individual and accounting for the autocorrelation structure of repeated assessments within an individual. All models included level-1 covariates of study day (time). Results are presented from unadjusted models and models adjusted for the level-2 covariates of gender and stress, which are differentially related to PTSD (Kilpatrick et al., 2013; Moser, Hajcak, Simons, & Foa, 2007), negative affect (Kring & Gordon, 1998; Moser et al., 2007), and avoidant coping (Matud, 2004; Roth & Cohen, 1986).

PTSD symptom severity was centered around the grand mean and evaluated using generalized mixed effects models for main effects of PTSD symptom severity on avoidant coping. To obtain unbiased estimates of the pooled within-person slopes, the level-1 predictor (negative affect) was person-mean centered and the person means were entered at level-2 to examine between-person variability. All models were initially set with random intercepts and random effects to vary across individuals. Models were run using full information maximum likelihood estimation, robust to missing data. Results are presented from population-averaging models with robust standard errors. To test the moderating effect of PTSD symptom severity on the bi-directional association of negative affect and avoidant coping, cross-level interactions were tested where PTSD symptom severity was added as a level-2 predictor of the level-1 coefficient. Significant interaction effects were examined through analysis of simple-slopes (Aiken & West, 1991).

Results

See Table 1 for prevalence rates of traumatic events assessed with the TESI. PTSD symptom severity on the PCL-C in the current study ranged from 17 to 81, with an average score of 30.53 (SD = 12.30). Using a recommended cut-off score of 44 or above (Blanchard, Jones-Alexander, Buckley, & Forneris, 1996; see Ruggerio et al. [2003] for evidence supporting this cut-off score in college student samples), 16.0% of the sample met criteria for a probable PTSD diagnosis.

Table 1.

Prevalence of lifetime traumatic events

| Item | % |

|---|---|

| Bad accident/fall/fire for self | 30.3 |

| Bad accident/fall/fire for someone else | 45.6 |

| Life threatening storm/earthquake/flood | 19.9 |

| Close loved one died unexpectedly | 36.9 |

| Life threatening illness/permanent injury | 13.2 |

| Separated from close adults as a child | 13.7 |

| Your children taken away from you | 0.2 |

| Someone tried to kill or hurt you really badly | 7.2 |

| Someone threatened to kill or hurt you badly | 11.3 |

| Witnessed family violence | 12.7 |

| In close relationship feared for life/felt trapped | 9.8 |

| Emotionally shamed/humiliated by someone close | 33.3 |

| Had an abortion or miscarriage | 1.5 |

| Witnessed violence outside of family | 18.6 |

| Been in a war or the military | 0.7 |

| Lost or left home due to disaster/war/homelessness | 2.5 |

| Made to do something sexual | 13.5 |

| Other events where self or other could be killed/died/hurt | 8.3 |

In basic models, daytime negative affect was significantly associated with evening avoidant coping (see Table 2), and evening avoidant coping was significantly associated with next-day daytime negative affect (see Table 3), at the person- and daily-level of analysis and unadjusted and adjusted for gender and stressfulness.

Table 2.

Daytime negative affect in relation to evening avoidant coping

| Avoidant Coping | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| B | SE | t | p | R2 | |

| Unadjusted Models | |||||

| Level-Two Negative Affect |

0.295 | 0.012 | 24.18 | <.001 | 0.311 |

| Level-One Negative Affect |

0.266 | 0.004 | 59.69 | <.001 | 0.133 |

| Adjusted Models | |||||

| Level-Two Negative Affect |

0.269 | 0.012 | 22.12 | <.001 | 0.327 |

| Level-One Negative Affect |

0.296 | 0.004 | 69.74 | <.001 | 0.145 |

Note. Estimates are adjusted for all variables in the table. Level-two=person level. Level-one=daily level. Adjusted model includes gender and daily stressfulness.

Table 3.

Evening avoidant coping in relation to next-day daytime negative affect

| Negative Affect | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| B | SE | t | p | R2 | |

| Unadjusted Models | |||||

| Level-Two Avoidant Coping |

0.073 | 0.004 | 20.73 | <.001 | 0.301 |

| Level-One Avoidant Coping |

0.058 | 0.003 | 22.76 | <.001 | 0.127 |

| Adjusted Models | |||||

| Level-Two Avoidant Coping |

0.044 | 0.003 | 17.33 | <.001 | 0.313 |

| Level-One Avoidant Coping |

0.040 | 0.002 | −16.15 | <.001 | 0.136 |

Note. Estimates are adjusted for all variables in the table. Level-two=person level. Level-one=daily level. Adjusted model includes gender and evening stressfulness.

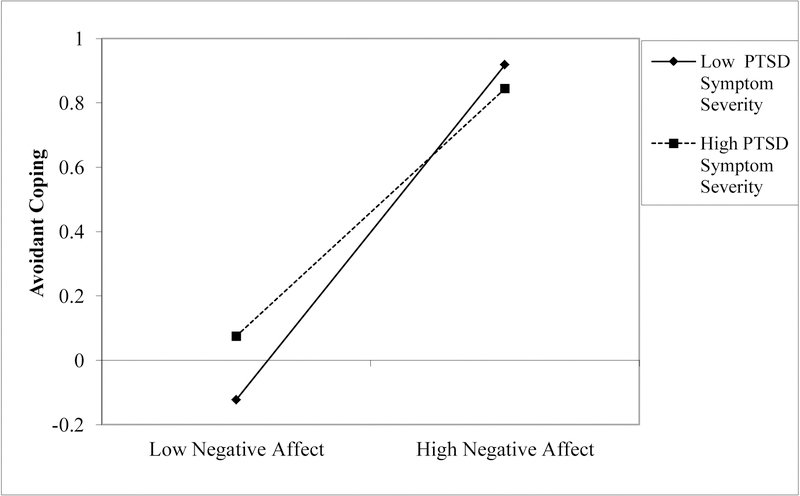

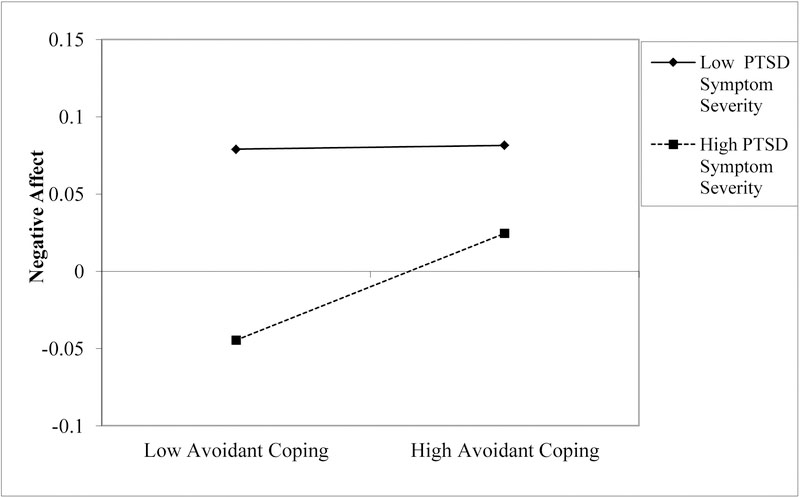

Next, moderation models explored the role of PTSD symptom severity in the reciprocal relations between avoidant coping and negative affect, at the person- and daily-level of analysis and unadjusted and adjusted for gender. Significant relations were found for the moderating role of PTSD symptom severity in daytime negative affect relating to later evening avoidant coping, (see Table 4), and evening avoidant coping relating to next-day daytime negative affect (see Table 5).1, 2 Analysis of simple slopes revealed that the strength of the relation of daytime negative affect to evening avoidant coping was weaker for trauma-exposed individuals with higher versus lower PTSD symptom severity, at the person- and daily-level of analysis and unadjusted and adjusted for gender (see Table 6 and Figure 1). Conversely, the strength of the relation of evening avoidant coping to next-day daytime negative affect was stronger for trauma-exposed individuals with higher versus lower PTSD symptom severity, at the person- and daily-level of analysis and unadjusted and adjusted for gender (see Table 7 and Figure 2).

Table 4.

PTSD symptom severity moderating the relation of daytime negative affect to evening avoidant coping

| Avoidant Coping | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Unadjusted Models | B | SE | t | p | R2 |

| Level-Two Negative Affect by PTSD Severity |

−0.135 | 0.052 | −2.61 | .009 | 0.413 |

| Level-One Negative Affect by PTSD Severity |

−0.150 | 0.019 | −7.73 | <.001 | 0.195 |

| Adjusted Models | |||||

| Level-Two Negative Affect by PTSD Severity |

−0.122 | 0.051 | −2.38 | .018 | 0.431 |

| Level-One Negative Affect by PTSD Severity |

−0.133 | 0.019 | −6.86 | <.001 | 0.208 |

Note. Estimates are adjusted for all variables in the table. Level-two=person level. Level-one=daily level. PTSD = post-traumatic stress disorder. Adjusted model includes gender and daytime stressfulness.

Table 5.

PTSD symptom severity moderating the relation of evening avoidant coping to next-day daytime negative affect

| Negative Affect | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Unadjusted Models | B | SE | t | p | R2 |

| Level-Two Avoidant Coping by PTSD Severity |

0.032 | 0.016 | 2.46 | .025 | 0.421 |

| Level-One Avoidant Coping by PTSD Severity |

0.028 | 0.012 | 2.34 | .020 | 0.122 |

| Adjusted Models | |||||

| Level-Two Avoidant Coping by PTSD Severity |

0.026 | 0.012 | 2.26 | .024 | 0.441 |

| Level-One Avoidant Coping by PTSD Severity |

0.025 | 0.011 | 2.19 | .029 | 0.132 |

Note. Estimates are adjusted for all variables in the table. Level-two=person level. Level-one=daily level. PTSD = post-traumatic stress disorder. Adjusted model includes gender and evening stressfulness.

Table 6.

Simple slope tests for daytime negative affect in relation to evening avoidant coping

| Avoidant Coping | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| B | SE | t | p | |

| Low PTSD symptom severity | ||||

| Unadjusted Model | ||||

| Level-Two Negative Affect | 0.265 | 0.025 | 10.47 | < .001 |

| Level-One Negative Affect | 0.275 | 0.009 | 29.5 | < .001 |

| Adjusted Model | ||||

| Level-Two Negative Affect | 0.248 | 0.025 | 9.746 | < .001 |

| Level-One Negative Affect | 0.256 | 0.01 | 26.43 | < .001 |

| High PTSD Symptom Severity | ||||

| Unadjusted Model | ||||

| Level-Two Negative Affect | 0.298 | 0.031 | 9.678 | < .001 |

| Level-One Negative Affect | 0.299 | 0.012 | 25.889 | < .001 |

| Adjusted Model | ||||

| Level-Two Negative Affect | 0.263 | 0.031 | 8.577 | < .001 |

| Level-One Negative Affect | 0.262 | 0.012 | 21.626 | < .001 |

Note. Estimates are adjusted for all variables in the table. Level-two=person level. Level-one=daily level. PTSD = post-traumatic stress disorder. Adjusted model includes gender and evening stressfulness.

Figure 1.

Moderating role of PTSD symptom severity in the daily relation between afternoon negative affect and evening avoidant coping

Note. Estimates are adjusted for all variables in the table. PTSD = post-traumatic stress disorder. Adjusted model includes gender and evening stressfulness.

Table 7.

Simple slope tests for evening avoidant coping in relation to next-day afternoon negative affect

| Avoidant Coping | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| B | SE | t | p | |

| Low PTSD symptom severity | ||||

| Unadjusted Model | ||||

| Level-Two Negative Affect | 0.063 | 0.013 | 5.05 | < .001 |

| Level-One Negative Affect | 0.045 | 0.007 | 5.95 | < .001 |

| Adjusted Model | ||||

| Level-Two Negative Affect | 0.042 | 0.013 | 3.373 | < .001 |

| Level-One Negative Affect | 0.032 | 0.007 | 4.426 | < .001 |

| High PTSD Symptom Severity | ||||

| Unadjusted Model | ||||

| Level-Two Negative Affect | 0.081 | 0.011 | 7.679 | < .001 |

| Level-One Negative Affect | 0.073 | 0.007 | 10.195 | < .001 |

| Adjusted Model | ||||

| Level-Two Negative Affect | 0.068 | 0.011 | 5.958 | < .001 |

| Level-One Negative Affect | 0.053 | 0.007 | 7.703 | < .001 |

Note. Estimates are adjusted for all variables in the table. Level-two=person level. Level-one=daily level. PTSD = post-traumatic stress disorder. Adjusted model includes gender and evening stressfulness.

Figure 2.

Moderating role of PTSD symptom severity in the daily relation between evening avoidant coping and next-day afternoon negative affect

Note. Estimates are adjusted for all variables in the table. PTSD = post-traumatic stress disorder. Adjusted model includes gender and evening stressfulness.

Discussion

The goal of the present study was to examine the daily, bi-directional relations between negative affect and avoidant coping, as well as the potential moderating role of PTSD symptom severity in these associations among trauma-exposed individuals. As hypothesized, negative affect and avoidant coping were found to demonstrate reciprocal associations at the daily level, such that levels of daytime negative affect were associated with use of evening avoidant coping, and use of evening avoidant coping were associated with levels of next-day daytime negative affect. Partially consistent with expectations, the strength of the daily association from negative affect to avoidant coping was stronger for individuals with less severe PTSD symptoms, whereas the strength of the daily association from avoidant coping to negative affect was stronger for individuals with more severe PTSD symptoms. These findings highlight dynamic, bi-directional relations among negative affect and avoidant coping, as well as provide support for the role of PTSD symptom severity in the strength of these relations.

The finding that the daily association from negative affect to avoidant coping was significant (and strong) among individuals with severe PTSD symptoms aligns with literature in this area. In the immediate aftermath of trauma, most individuals exhibit some PTSD symptoms. However, many of these individuals will experience a significant reduction or complete remittance of PTSD symptoms within several months (Rothbaum, Foa, Riggs, Murdock, & Walsh, 1992). Avoidant coping has been theorized to play a central role in maintenance of PTSD symptoms (Foa & Kozak, 1986; Foa & Rothbaum, 1998; Keane & Barlow, 2002). For instance, avoidant coping has been posited to interfere with emotional processing of traumatic memories, such as by increasing attentional bias towards threat and trauma-related stimuli (Buckley, Blanchard, & Neill, 2000). Further, avoidant coping has been hypothesized to impede habituation of anxiety-related autonomic responses associated with traumatic memories, including the activation of the traumatic memory (also referred to as the fear memory) and introduction of new information that is incompatible with the existing memory (Foa & Kozak, 1986). Finally, avoidant coping is thought to interfere with the extinction of conditioned fear responses, including behavioral sensitization to stress (McLaughlin, Conron, Koenen, & Gilman, 2010), overgeneralization of the conditioned stimulus-unconditioned stimulus response (Pole et al., 2009), impaired extinction of conditioned stimulus-unconditioned stimulus pairings (Blechert, Michael, Vriends, Margraf, & Wilhelm, 2007), and impaired fear inhibitory learning (Jovanovic et al., 2009). Consistent with this theory, greater use of avoidant coping among trauma-exposed individuals has been shown to predict later PTSD symptoms (e.g., Dempsey et al., 2000; Krause et al., 2008; Pineles et al., 2011).

However, contrary to expectations, the association from negative affect to avoidant coping was slightly stronger among individuals with less (vs. more) severe PTSD symptoms. Future research is needed to better understand this finding. For instance, it is possible that trauma-exposed individuals with more severe PTSD symptoms exhibit heightened use of a wide range of coping strategies following negative affect, resulting in lower overall use of avoidant coping following negative affect when compared to trauma-exposed individuals with less severe PTSD symptoms. This hypothesis is consistent with Dixon-Gordon, Aldao, and De Los Reyes (2015), who found that individuals with more severe psychopathology (i.e., mood, anxiety, and borderline personality symptoms) reported high use of a greater number of coping strategies. Such an explanation is consistent with the notion that trauma-exposed individuals with more severe PTSD symptoms experience more negative affect, and thus require greater coping efforts. Future investigations that explore the relation between negative affect and multiple coping strategies are needed to test this hypothesis. It is also possible that traumatic exposure plays a more pivotal role in the negative affect-avoidant coping link than PTSD symptom severity. Indeed, our findings suggest that negative affect is strongly associated with later avoidant coping for trauma-exposed individuals, with relatively limited influence by PTSD symptoms. Research that examines these relations among individuals with (vs. without) traumatic exposure is warranted.

Extending existing research, and consistent with study hypotheses, our findings provided support for a reciprocal association of avoidant coping to negative affect at the daily level of analysis among trauma-exposed individuals. Moreover, they indicated that the strength of this association from avoidant coping to negative affect was stronger among trauma-exposed individuals in our sample who reported greater (vs. lower) PTSD symptom severity. Said otherwise, trauma-exposed individuals with greater PTSD symptom severity were more likely to experience negative affect following use of avoidant coping than those with less severe PTSD symptoms. This may suggest that avoidant coping is less effective at diminishing negative affect among trauma-exposed individuals with more (vs. less) severe PTSD symptoms. Alternatively, avoidant coping may be more likely to result in a rebound in distress among trauma-exposed individuals with more (vs. less) severe PTSD symptoms, leading to greater persistence of negative affect over time. Future research is warranted to explore these possible explanations.

Nonetheless, our findings provide further support for the utility of targeting the negative affect-avoidant coping link in the treatment of trauma-exposed individuals. Following traumatic exposure, individuals may benefit from being taught approach coping strategies for managing negative affect (e.g., getting in touch with negative emotions, allowing oneself to experience negative emotions, paying attention to the information being provided by negative emotions) to replace avoidant coping strategies (Emotion Regulation Group Therapy; Gratz, Tull, & Levy, 2014). Indeed, among trauma-exposed military veterans, greater use of approach coping to modulate distress has been found to be associated with fewer trauma-related negative outcomes (e.g., PTSD and depression severity; Hassija, Luterek, Naragon-Gainey, Moore, & Simpson, 2012). Additionally, evidence for a reciprocal relation of negative affect to avoidant coping indicates that strategies aimed at reducing negative affect may be valuable in reducing the negative affect-avoidant coping link, and subsequent PTSD symptom severity. For instance, the dialectical behavior therapy skill ACT PLEASE (Linehan, 2014) is used to decrease vulnerability to negative emotions, and involves accumulating positive emotions (A), building mastery (B), coping ahead (C), treating physical illness (PL), balanced eating (E), avoiding mind-altering drugs (A), balanced sleep (S), and exercise (E); dialectical behavior therapy has shown promise in reducing PTSD symptom severity (Harned, Korslund, & Linehan, 2014).

The direct targeting of the negative affect-avoidant coping link also has shown promise in reducing negative trauma-related outcomes. Prolonged exposure, a first-line treatment for PTSD (Rauch, Eftekhari, & Ruzek, 2012), is purported to facilitate recovery from PTSD through habituation (Foa, Hembree, & Rothbaum, 2007). Specifically, imaginal and in vivo exposures are thought to modify fear structures that maintain PTSD by providing corrective information (Rauch & Foa, 2006). Through engagement with traumatic memories – the antithesis of trauma-related avoidance – habituation of anxiety-related autonomic responses associated with traumatic memories (i.e., negative affect) is promoted. Regarding the relation of negative affect to avoidant coping, research suggests that, in some instances, a reduction in intense, overwhelming negative affect, such as through techniques aimed at promoting grounding, a present-focus, or cognitive change, may facilitate approach of traumatic memories in prolonged exposure (Jaycox & Foa, 1996). Finally, our results suggest the value of assessing negative affect and avoidant coping among individuals identified by traumatic exposure (e.g., within the emergency department following a physical injury) or PTSD (e.g., within an outpatient mental health clinic) to identify individuals who would benefit from prevention and intervention efforts, respectively.

Of note, supplemental analyses found that the pattern of findings for moderation analyses remained the same in strength and direction for PTSD re-experiencing and avoidance (but not numbing and hyperarousal) symptom severity. It will be important for future studies to clarify the potentially differential impact of PTSD symptom clusters on the association between negative affect and avoidant coping, ideally using the PTSD symptom clusters outlined in the DSM-5 (i.e., intrusions, avoidance, negative alterations in cognitions and mood, and alterations in arousal and reactivity; APA, 2013).

Although findings of the present study improve our understanding of the directionality of the negative affect-avoidant coping relation among trauma-exposed individuals with varying levels of PTSD symptom severity, several limitations are noteworthy. First, the correlational nature of the data precludes causal determination of the relations examined. Future research is needed using experimental paradigms in the laboratory (e.g., emotion induction) to clarify the relation of negative affect to avoidant coping among individuals with varying levels of PTSD symptom severity. Second, avoidant coping was assessed daily with a single-item measure, which has the disadvantage of having low content validity, sensitivity, and reliability. Nonetheless, single-item measures are practical when measurements are taken at frequent intervals, such as within daily diary studies, to reduce participant burden. Further, they have been shown to demonstrate adequate psychometric properties in daily diary studies where a limited number of items can be included (Cappelleri et al., 2009; Van Hooff, Geurts, Kompier, & Taris, 2007). Future research should consider including more comprehensive measures of daily coping, such as those assessing perceived efficacy of avoidant coping.

Second, evaluation of the context in which avoidant coping has occurred may provide further evidence regarding the adaptive vs. maladaptive nature of such efforts (Aldao, 2013). Indeed, although generally associated with deleterious outcomes (Aldao, Nolen-Hoeksema, & Schweizer, 2010), avoidant coping may be adaptive in some contexts (e.g., when employed flexibly to meet situational demands; Bonanno, Papa, Lalande, Westphal, & Coifman, 2004). For instance, avoidant coping may confer short-term benefits when presented with physical threat (Lewis et al., 2006) or in contexts perceived as uncontrollable (Vitaliano, DeWolfe, Maiuro, Russo, & Katon, 1990). A more comprehensive assessment of contextual factors would also be valuable to understanding the factors that both drive and constrain the association between negative affect and avoidant coping. For example, it is likely that daily experiences promote or impede both negative affect (e.g., stressful vs. pleasurable events) and avoidant coping (e.g., work vs. home environment).

Third, avoidant coping was only assessed in the evening, precluding assessment of the impact of evening negative affect on next-day daytime avoidant coping. This is an important avenue for future research as daytime and evening experiences (e.g., interpersonal interactions) and physiological functioning (e.g., cortisol secretion) may differ in important ways. Further, research using daily survey methods suggests that there is some stability in behavior from day to day, often because the underlying stressors/problems are still be salient. However, there are many things that could happen from one day to the next that could alter affect and coping. For example, someone might have been in a bad mood at mid-day assessment, then had a fun night, which in turn negated any effect of negative affect on next day avoidant coping. Alternatively, sleep may ameliorate stress, and thus reports of prior-evening avoidant coping may not be systematic. Thus, our models do suffer from misspecification in that do not account for all experiences that could have happened between reporting periods. That said, it is possible that omission of these variables actually weakens our findings. Future studies should test this hypothesis. Fourth, given that avoidance is characteristic of PTSD, it is possible that the link between PTSD symptom severity and avoidant coping reflects a measurement confound. Although our analyses that exclude PTSD avoidance items suggest a similar pattern of findings, future research would benefit from further examining this overlap.

Finally, our findings may not generalize to other samples (e.g., with regard to age, race/ethnicity, education). For instance, given the aims of the larger study, our study was comprised of alcohol-using college students. The relation of PTSD to the negative affect-avoidant coping link may be stronger among alcohol-users given evidence that alcohol use is one strategy that individuals with PTSD may use to module trauma symptoms and distress (Weiss, Tull, Viana, Anestis, & Gratz, 2012). Further, while trauma is highly prevalent among college students (Frazier et al., 2009) and associated with deleterious outcomes (Anders, Frazier, & Shallcross, 2012), including PTSD symptom severity (Read et al., 2012), replication across other samples of trauma-exposed individuals (e.g., clinical) is needed. Nonetheless, analogue samples have important strengths, such as identifying vulnerabilities to the initial development of clinical phenomena (Tull et al., 2008), highlighting the importance of research with college students to the research process.

Despite these limitations, findings of the present study underscore reciprocal relations among negative affect and avoidant coping at the daily level. Further, our results provide support for the moderating role of PTSD symptom severity in bi-directional relations between negative affect and avoidant coping, such that for individuals with more (vs. less) severe PTSD symptoms, the association of negative affect to avoidant coping was weaker and the association of avoidant coping to negative affect was stronger. These findings suggest the utility of treatments targeting negative affect to reduce avoidant coping among trauma-exposed individuals broadly, and avoidant coping to reduce negative affect among trauma-exposed individuals with greater PTSD symptom severity in particular.

Highlights.

Daytime negative affect related to evening avoidant coping

Evening avoidant coping related to next-day daytime negative affect

Daily relation of negative affect to avoidant coping was stronger among individuals with less severe PTSD symptoms

Daily relation of avoidant coping to negative affect was stronger among individuals with more severe PTSD symptoms

Findings advance our understanding of the negative affect-avoidant coping association

Acknowlegdements

The research described here was supported, in part, by grants from the National Institute on Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism (P60AA003510) and National Institute on Drug Abuse (K23DA039327).

Role of Funding Source

This project was supported by a grant from the National Institute on Alcohol Abuse (P60AA003510). Work on this paper by the first author was also supported by National Institute on Drug Abuse grant K23DA039327. The opinions, findings, and conclusions or recommendations in this manuscript are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect those of the National Institute on Alcohol Abuse or the National Institute on Drug Abuse.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

The avoidance items were removed from the PCL-C and analyses were re-ran. Findings remained the same in strength and direction.

Moderation analyses were re-ran using the PTSD symptom cluster severity scores (i.e., re-experiencing, avoidance, numbing, and hyperarousal). Results remained the same in strength and direction for PTSD re-experiencing and avoidance symptom severity. PTSD numbing and hyperarousal symptom severity did not moderate the bi-directional relation between negative affect and avoidant coping.

Declaration-of-competing-interests

The authors have no conflicts of interest to report.

Contributor Information

Nicole H. Weiss, University of Rhode Island, 142 Flagg Rd., Kingston, RI, 02881

Megan M. Risi, University of Rhode Island, 142 Flagg Rd., Kingston, RI, 02881

Tami P. Sullivan, Yale University School of Medicine, 389 Whitney Avenue, New Haven, CT 06511

Stephen Armeli, Fairleigh Dickinson University, 1000 River Road, Teaneck, NJ, 07666

Howard Tennen, University of Connecticut Health Center, 263 Farmington Avenue, Farmington, CT, 06030

References

- Aiken LS, & West SG (1991). Multiple regression: Testing and interpreting interactions Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage. [Google Scholar]

- Aldao A (2013). The future of emotion regulation research capturing context. Perspectives on Psychological Science, 8, 155–172. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Aldao A, Nolen-Hoeksema S, & Schweizer S (2010). Emotion-regulation strategies across psychopathology: A meta-analytic review. Clinical Psychology Review, 30, 217–237. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Aldwin CM, & Yancura LA (2004). Coping and health: A comparison of the stress and trauma literatures Washington, D.C.: American Psychological Association. [Google Scholar]

- American Psychiatric Association [APA]. (2013). Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders (5th ed.). Washington, DC: Author. [Google Scholar]

- Anders SL, Frazier PA, & Shallcross SL (2012). Prevalence and effects of life event exposure among undergraduate and community college students. Journal of Counseling Psychology, 59, 449–457. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Blanchard EB, Jones-Alexander J, Buckley TC, & Forneris CA (1996). Psychometric properties of the PTSD Checklist (PCL). Behaviour Research and Therapy, 34, 669–673. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Blechert J, Michael Tanja, Vriends Noortje, Margraf Jurgen, & Wilhelm Frank H. (2007). Fear conditioning in posttraumatic stress disorder: Evidence for delayed extinction of autonomic, experiential, and behavioural responses. Behavior Research and Therapy, 45, 2019–2033. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boden MT, Bonn-Miller Marcel O, Vujanovic Anka A, & Drescher Kent D. (2012). A prospective investigation of changes in avoidant and active coping and posttraumatic stress disorder symptoms among military Veteran. Journal of Psychopathology and Behavioral Assessment, 34, 433–439. [Google Scholar]

- Bolger N, & Laurenceau JP. (2013). Intensive longitudinal methods: An introduction to diary and experience sampling research New York: Guilford. [Google Scholar]

- Bonanno GA, Papa A, Lalande K, Westphal M, & Coifman K (2004). The importance of being flexible the ability to both enhance and suppress emotional expression predicts long-term adjustment. Psychological Science, 15, 482–487. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Buckley TC, Blanchard EB, & Neill WT (2000). Information processing and PTSD: A review of the empirical literature. Clinical Psychology Review, 20, 1041–1065. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Campbell-Sills L, Barlow DH, Brown TA, & Hofmann SG (2006). Effects of suppression and acceptance on emotional responses of individuals with anxiety and mood disorders. Behaviour Research and Therapy, 44, 1251–1263. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cappelleri JC, Bushmakin Andrew G, McDermott Anne M, Sadosky Alesia B, Petrie Charles D, & Martin Susan. (2009). Psychometric properties of a single-item scale to assess sleep quality among individuals with fibromyalgia. Health and Quality of Life Outcomes, 7, 54. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Csikszentmihalyi M (2014). Flow and the foundations of positive psychology: The collected works of Mihaly Csikszentmihalyi Dordrecht, Netherlands: Springer. [Google Scholar]

- Dan-Glauser ES, & Gross JJ (2015). The temporal dynamics of emotional acceptance: Experience, expression, and physiology. Biological Psychology, 108, 1–12. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dempsey M, Stacy O, & Moely B (2000). “Approach” and “avoidance” coping and PTSD symptoms in innercity youth. Current Psychology, 19, 28–45. [Google Scholar]

- Dickson KS, Ciesla JA, & Reilly LC (2012). Rumination, worry, cognitive avoidance, and behavioral avoidance: Examination of temporal effects. Behavior Therapy, 43, 629–640. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dixon-Gordon KL, Aldao A, & De Los Reyes A (2015). Repertoires of emotion regulation: A person-centered approach to assessing emotion regulation strategies and links to psychopathology. Cognition and Emotion, 29, 1314–1325. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Elhai JD, Miller ME, Ford JD, Biehn TL, Palmieri PA, & Frueh BC (2012). Posttraumatic stress disorder in DSM-5: Estimates of prevalence and symptom structure in a nonclinical sample of college students. Journal of Anxiety Disorders, 26, 58–64. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fagundes CP, Berg CA, & Wiebe DJ (2012). Intrusion, avoidance, and daily negative affect among couples coping with prostate cancer: A dyadic investigation. Journal of Family Psychology, 26, 246–253. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fischer S, Smith GT, Spillane N, & Cyders MA (2005). Urgency: Individual differences in reaction to mood and implications for addictive behaviors. In Clark AV (Ed.), The Psychology of Mood (pp. 85–107). New York, NY: Nova Science Publishers. [Google Scholar]

- Foa EB, Hembree E, & Rothbaum BO (2007). Prolonged exposure therapy for PTSD: Emotional processing of traumatic experiences New Yourk, NY: Oxford University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Foa EB, & Kozak MJ (1986). Emotional processing of fear: Exposure to corrective information. Psychological Bulletin, 99, 20–35. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Foa EB, & Rothbaum BO (1998). Treating the trauma of rape: Cognitive-behavioral therapy for PTSD New York: Guilford Press. [Google Scholar]

- Folkman S, & Lazarus RS (1988a). Coping as a mediator of emotion. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 54, 466–475. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Folkman S, & Lazarus RS (1988b). The relationship between coping and emotion: Implications for theory and research. Social Science & Medicine, 26, 309–317. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ford JD, Racusin R, Ellis CG, Daviss WB, Reiser J, Fleischer A, & Thomas J (2000). Child maltreatment, other trauma exposure, and posttraumatic symptomatology among children with oppositional defiant and attention deficit hyperactivity disorders. Child Maltreatment, 5, 205–217. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Frazier P, Anders S, Perera S, Tomich P, Tennen H, Park CL, & Tashiro T (2009). Traumatic events among undergraduate students: Prevalence and associated symptoms. Journal of Counseling Psychology, 56, 450–460. [Google Scholar]

- Frydenberg E (2014). Coping research: Historical background, links with emotion, and new research directions on adaptive processes. Australian Journal of Psychology, 66, 82–92. [Google Scholar]

- Grandey AA, Frone MR, Melloy RC, & Sayre GM (in press). When are fakers also drinkers? A self-control view of emotional labor and alcohol consumption among US service workers. Journal of Occupational Health Psychology [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Gratz KL, Tull MT, & Levy R (2014). Randomized controlled trial and uncontrolled 9-month follow-up of an adjunctive emotion regulation group therapy for deliberate self-harm among women with borderline personality disorder. Psychological Medicine, 1–14. [DOI] [PubMed]

- Harned MS, Korslund KE, & Linehan MM (2014). A pilot randomized controlled trial of Dialectical Behavior Therapy with and without the Dialectical Behavior Therapy Prolonged Exposure protocol for suicidal and self-injuring women with borderline personality disorder and PTSD. Behavior Research and Therapy, 55, 7–17. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hassija CM, Luterek Jane A, Naragon-Gainey Kristin, Moore Sally A, & Simpson Tracy. (2012). Impact of emotional approach coping and hope on PTSD and depression symptoms in a trauma exposed sample of veterans receiving outpatient VA mental health care services. Anxiety, Stress & Coping, 25, 559–573. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hayes SC, Wilson KG, Gifford EV, Follette VM, & Strosahl K (1996). Experiential avoidance and behavioral disorders: A functional dimensional approach to diagnosis and treatment. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology, 64, 1152–1168. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hellmuth JC, Jaquier V, Swan SC, & Sullivan TP (2014). Elucidating posttraumatic stress symptom profiles and their correlates among women experiencing bidirectional intimate partner violence. Journal of Clinical Psychology, 70, 1008–1021. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Inzlicht M, & Schmeichel BJ (2012). What is ego depletion? Toward a mechanistic revision of the resource model of self-control. Perspectives on Psychological Science, 7, 450–463. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jaycox LH, & Foa EB (1996). Obstacles in implementing exposure therapy for PTSD: Case discussions and practical solutions. Clinical Psychology & Psychotherapy: An International Journal of Theory and Practice, 3, 176–184. [Google Scholar]

- Jovanovic T, Norrholm SD, Fennell JE, Keyes M, Fiallos AM, Myers KM, … Duncan EJ (2009). Posttraumatic stress disorder may be associated with impaired fear inhibition: Relation to symptom severity. Psychiatry Research, 167, 151–160. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Keane TM, & Barlow DH (2002). Posttraumatic stress disorder. In Barlow DH (Ed.), Anxiety and its disorder: The nature and treatment of anxiety and panic (Vol. 418–452). New York: Guilford Press. [Google Scholar]

- Kilpatrick DG, Resnick HS, Milanak ME, Miller MW, Keyes KM, & Friedman MJ (2013). National estimates of exposure to traumatic events and PTSD prevalence using DSM‐ IV and DSM‐ 5 criteria. Journal of Traumatic Stress, 26, 537–547. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kool W, McGuire JT, Rosen ZB, & Botvinick MM (2010). Decision making and the avoidance of cognitive demand. Journal of Experimental Psychology: General, 139, 665–682. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Krause ED, Kaltman S, Goodman LA, & Dutton MA (2008). Avoidant coping and PTSD symptoms related to domestic violence exposure: A longitudinal study. Journal of Traumatic Stress, 21, 83–90. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kring AM, & Gordon AH (1998). Sex differences in emotion: Expression, experience, and physiology. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 74, 686–703. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lazarus RS, & Folkman S (1984). Stress, appraisal, and coping New York: Springer. [Google Scholar]

- Lewis CS, Griffing S, Chu M, Jospitre T, Sage RE, Madry L, & Primm BJ (2006). Coping and violence exposure as predictors of psychological functioning in domestic violence survivors. Violence Against Women, 12, 340–354. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Linehan M (2014). DBT Skills Training Manual New York: Guilford Publications. [Google Scholar]

- Litt MD, Tennen H, & Affleck G (2010). The dynamics of stress, coping and health: Assessing stress and coping processes in near real time. In Folkman S (Ed.), The Oxford handbook of stress, health, and coping (pp. 387–406). San Francisco, CA: Oxford University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Matud MP (2004). Gender differences in stress and coping styles. Personality and Individual Differences, 37, 1401–1415. [Google Scholar]

- McLaughlin KA, Conron KJ, Koenen KC, & Gilman SE (2010). Childhood adversity, adult stressful life events, and risk of past-year psychiatric disorder: A test of the stress sensitization hypothesis in a population-based sample of adults. Psychological Medicine, 40, 1647–1658. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mennin DS, Heimberg RG, Turk CL, & Fresco DM (2005). Preliminary evidence for an emotion dysregulation model of generalized anxiety disorder. Behavior Research and Therapy, 43, 1281–1310. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miller MW, Kaloupek DG, Dillon Amy L, & Keane Terence M. (2004). Externalizing and internalizing subtypes of combat-related PTSD: A replication and extension using the PSY-5 scales. Journal of Abnormal Psychology, 113, 636–645. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miller MW, & Resick PA (2007). Internalizing and externalizing subtypes in female sexual assault survivors: Implications for the understanding of complex PTSD. Behavior Therapy, 38, 58–71. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moser JS, Hajcak G, Simons RF, & Foa EB (2007). Posttraumatic stress disorder symptoms in trauma-exposed college students: The role of trauma-related cognitions, gender, and negative affect. Journal of Anxiety Disorders, 21, 1039–1049. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Olff M, Langeland W, & Gersons BPR (2005). The psychobiology of PTSD: Coping with trauma. Psychoneuroendocrinology, 30, 974–982. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pacella ML, Hruska B, & Delahanty DL (2013). The physical health consequences of PTSD and PTSD symptoms: A meta-analytic review. Journal of Anxiety Disorders, 27, 33–46. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Park CL, & Iacocca MO (2014). A stress and coping perspective on health behaviors: Theoretical and methodological considerations. Anxiety, Stress & Coping, 27, 123–137. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pineles SL, Mostoufi SM, Ready CB, Street AE, Griffin MG, & Resick PA (2011). Trauma reactivity, avoidant coping, and PTSD symptoms: A moderating relationship? Journal of Abnormal Psychology, 120, 240–246. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pole N, Neylan TC, Otte C, Henn-Hasse C, Metzler TJ, & Marmar SR (2009). Prospective prediction of posttraumatic stress disorder symptoms using fear potentiated auditory startle responses. Biological Psychiatry, 65, 235–240. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rauch S, Eftekhari A, & Ruzek JI (2012). Review of exposure therapy: A gold standard for PTSD treatment. Journal of Rehabilitation Research and Development, 49, 679–688. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rauch S, & Foa E (2006). Emotional processing theory (EPT) and exposure therapy for PTSD. Journal of Contemporary Psychotherapy, 36, 61–. [Google Scholar]

- Read JP, Colder CR, Merrill JE, Ouimette P, White J, & Swartout A (2012). Trauma and posttraumatic stress symptoms predict alcohol and other drug consequence trajectories in the first year of college. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology, 80, 426–439. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Revenson TA, & Lepore SJ (2012). Stress and coping processes in social context New York: Psychology Press. [Google Scholar]

- Roth S, & Cohen LJ (1986). Approach, avoidance, and coping with stress. American Psychologist, 41, 813. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rothbaum BO, Foa EB, Riggs DS, Murdock T, & Walsh W (1992). A prospective examination of post-traumatic stress disorder in rape victims. Journal of Traumatic Stress, 5, 455–475. [Google Scholar]

- Ruggiero KJ, Del Ben K, Scotti JR, & Rabalais AE (2003). Psychometric properties of the PTSD Checklist—Civilian version. Journal of Traumatic Stress, 16, 495–502. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rytwinski NK, Scur MD, Feeny NC, & Youngstrom EA (2013). The co‐occurrence of major depressive disorder among individuals with posttraumatic stress disorder: A meta‐ analysis. Journal of Traumatic Stress, 26, 299–309. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Skinner EA, Edge K, Altman J, & Sherwood H (2003). Searching for the structure of coping: A review and critique of category systems for classifying ways of coping. Psychologial Bulletin, 129, 216–269. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stone AA, & Shiffman S (2002). Capturing momentary, self-report data: A proposal for reporting guidelines. Annals of Behavioral Medicine, 24, 236–243. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stone AA, Shiffman S, Alienza AA, & Nebeling L (2007). The science of real-time data capture: Self-reports in health research New York, NY: Oxford University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Tennen H, Affleck G, Armeli S, & Carney MA (2000). A daily process approach to coping: Linking theory, research, and practice. American Psychologist, 55, 626–636. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tull MT, Bornovalova MA, Patterson R, Hopko DR, & Lejuez CW (2008). Analogue research. In McKay D (Ed.), Handbook of research methods in abnormal and clinical psychology Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage Publications. [Google Scholar]

- Tull MT, Jakupcak M, & Roemer L (2010). Emotion suppression: A preliminary experimental investigation of its immediate effects and role in subsequent reactivity to novel stimuli. Cognitive Behaviour Therapy, 39, 114–125. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tull MT, Weiss NH, & McDermott MJ (2015). Posttraumatic stress disorder and impulsive and risky behavior: An overview and discussion of potential mechanisms. In Martin CR, Preedy VR, & Patel VB (Eds.), Comprehensive Guide to Post-traumatic Stress Disorders (pp. 803–816). New York, NY: Springer. [Google Scholar]

- Van Hooff MLM, Geurts SAE, Kompier MAJ, & Taris TW (2007). “How fatigued do you currently feel?” Convergent and discriminant validity of a single-item fatigue measure. Journal of Occupational Health, 49, 224–234. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vitaliano PP, DeWolfe DJ, Maiuro RD, Russo J, & Katon W (1990). Appraised changeability of a stressor as a modifier of the relationship between coping and depression: A test of the hypothesis of fit. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 59, 582–592. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weathers FW, Litz BT, Herman DS, Huska JA, & Keane TM (1993). The PTSD Checklist (PCL): Reliability, validity, and diagnostic utility. Paper presented at the International Society for Traumatic Stress Studies. [Google Scholar]

- Weiss NH, Bold KW, Sullivan TP, Armeli S, & Tennen H (2017). Testing bidirectional associations among emotion regulation strategies and substance use: A daily diary study. Addiction, 112, 695–704. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weiss NH, Tull MT, Viana AG, Anestis MD, & Gratz KL (2012). Impulsive behaviors as an emotion regulation strategy: Examining associations between PTSD, emotion dysregulation, and impulsive behaviors among substance dependent inpatients. Journal of Anxiety Disorders, 26, 453–458. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]