Abstract

Polymorphic eruption of pregnancy, formerly known as pruritic and urticarial papules and plaques of pregnancy, is an uncommon cutaneous eruption that can affect women during their third trimester of pregnancy. As its name implies, it has a variety of morphologies and it is important to consider other diagnoses, such as pemphigoid gestationis, which polymorphic eruption of pregnancy can mimic. Sometimes, as in this case, polymorphic eruption of pregnancy can have a targetoid morphology reminiscent of erythema multiforme. A thorough workup and conservative management plan helps reassure the patient that the correct approach is being taken during the challenging period of a pregnancy nearing completion.

Keywords: Polymorphic eruption of pregnancy, Pregancy related skin conditions

Introduction

Pregnant women may present with a variety of cutaneous eruptions. Beyond adding extra stress during a physiologically and psychologically demanding period, the eruptions can place the mother or fetus at risk for significant complications. Polymorphic eruption of pregnancy (PEP) is a gestational eruption that is bothersome but not dangerous. However, it can sometimes mimic more dangerous eruptions and make the patient (and sometimes the clinician) anxious.

Case report

A 36-year-old G2P0TA1 at 34 weeks gestation with monochorionic-diamniotic twins presented with a 1-week history of a widely distributed pruritic eruption. It started on her abdomen and quickly spread to affect her arms, legs and back. It spared her umbilicus, palms, soles and face. Her mucosal membranes were uninvolved. She was otherwise healthy, and her past medical history was non-contributory. She did not take any medications besides prenatal vitamins. Her family history was negative for atopy.

On examination, she looked uncomfortable but systemically well. She had scattered erythematous papules, coalescing into plaques on her abdomen (Figure 1(a)), back and legs with sparing of the periumbilical area. On the arms, she had multiple erythematous targetoid plaques (Figure 1(b)). The differential diagnosis included PEP, erythema multiforme, acute spontaneous urticaria and pemphigoid gestationis (PG).

Figure 1.

(a) Erythematous papules and plaques located on the patient’s abdomen. The papules and plaques favour the striae and spare the umbilicus. (b) The plaques on the arms are targetoid and reminiscent of erythema multiforme.

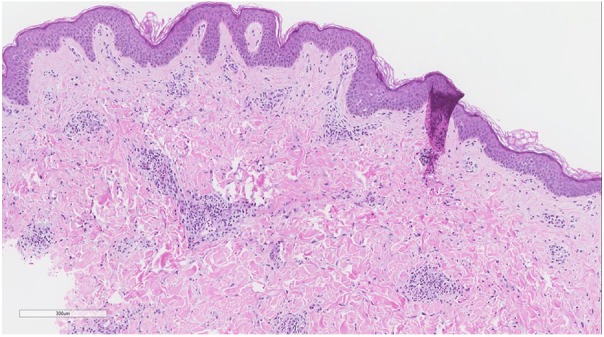

A biopsy was performed for routine histology and direct immunofluorescence was done to rule out PG. The hematoxylin and eosin (H&E) slide demonstrated findings consistent with PEP (Figure 2). The direct immunofluorescence was negative. The patient was prescribed 0.1% betamethasone valerate cream and an oral antihistamine. On follow-up 4 weeks later, she reported that she had delivered healthy twins at 35 weeks after a planned induction without complications and her skin eruption had completely resolved.

Figure 2.

Biopsy of lesional skin shows a superficial perivascular infiltrate of lymphocytes, histiocytes and occasional eosinophils. Focal, mild spongiosis is present. Subepidermal blistering is absent (Hematoxylin and eosin, 40×). Direct immunofluorescence of perilesional skin was negative (not shown).

Discussion

PEP is pruritic cutaneous eruption associated with pregnancy. It usually occurs in the third trimester or immediate postpartum period. Risk factors for PEP include twin pregnancies and rapid weight gain.1 It has a range of morphologies, particularly erythematous urticarial papules and plaques. It is usually pruritic and it most often begins on the abdomen but spares the umbilicus. The targetoid form of PEP occurs in about 5% of patients with the disease2 and, like other forms of PEP, the targetoid form has a benign, self-limited course, generally resolving within 1 week after delivery. Importantly, the targetoid morphology raises the possibility of erythema multiforme. Erythema multiforme may be painful rather than pruritic. Nevertheless, a biopsy for H&E and direct immunofluorescence should be considered to rule out conditions that may affect the fetus such as PG. PEP has no direct effects on the fetus. It is usually treated symptomatically with oral antihistamines and topical corticosteroids. Systemic corticosteroids may be required when the disease is extensive.

Footnotes

Declaration of conflicting interests: The author(s) declared no potential conflicts of interest with respect to the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

Funding: The author(s) received no financial support for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

Informed consent: The patient provided consent for publication of her case and photos.

References

- 1. Rudolph CM, Al-Fares S, Vaughan-Jones SA, et al. Polymorphic eruption of pregnancy: clinicopathology and potential trigger factors in 181 patients. Br J Dermatol 2006; 154(1): 54–60. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Sirikudta W, Silpa-Archa N. Polymorphic eruption of pregnancy presented with targetoid lesions: a report of two cases. Case Rep Dermatol 2013; 5(2): 138–143. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]