Abstract

Background

Cervical cancer, although almost entirely preventable through cervical cancer screening (CCS) and human papillomavirus vaccination, is the leading cause of cancer deaths among women in Tanzania. Barriers to attending CCS include lack of awareness of CCS, affordability concerns regarding screening and travel cost. We aimed to compare the effectiveness of SMS (short message service) behaviour change communication (BCC) messages and of SMS BCC messages delivered with a transportation electronic voucher (eVoucher) on increasing uptake of CCS versus the control group.

Methods

Door-to-door recruitment was conducted between 1 February and 13 March 2016 in randomly selected enumeration areas in the catchment areas of two hospitals, one urban and one rural, in Northern Tanzania. Women aged 25–49 able to access a mobile phone were randomised using a computer-generated 1:1:1 sequence stratified by urban/rural to receive either (1) 15 SMS, (2) an eVoucher for return transportation to CCS plus the same SMS, or (3) one SMS informing about the nearest CCS clinic. Fieldworkers and participants were masked to allocation. All areas received standard sensitisation including posters, community announcements and sensitisation similar to community health worker (CHW) sensitisation. The primary outcome was attendance at CCS within 60 days of randomisation.

Findings

Participants (n=866) were randomly allocated to the BCC SMS group (n=272), SMS + eVoucher group (n=313), or control group (n=281), with 851 included in the analysis (BCC SMS n=272, SMS + eVoucher n=298, control group n=281). By day 60 of follow-up, 101 women (11.9%) attended CCS. Intervention group participants were more likely to attend than control group participants (SMS + eVoucher OR: 4.7, 95% CI 2.9 to 7.4; SMS OR: 3.0, 95% CI 1.5 to 6.2).

Trial registration number

Keywords: cancer, mHealth, global health, Accessible

Introduction

Tanzania, like many other low-income and middle-income countries, is experiencing an epidemiological transition.1 The major causes of death are shifting from primarily communicable diseases and accidents to a mix of communicable and non-communicable diseases, including cardiovascular diseases, cancer and chronic respiratory diseases. This places a strain on a weak health system that is currently unequipped to handle this burden.2 3 The Sub-Saharan African (SSA) region is predicted to have a greater than 85% increase in cancer burden by the year 2030.4 The fact that many leading cancers, including cervical cancer (CCa), can be treated with curative intent5 provides impetus to strengthen cancer prevention.

CCa represents 25% of all cancers among women in SSA, and it is the highest cause of cancer mortality among women in the region.6 Despite widespread awareness of CCa in the Kilimanjaro Region of Tanzania (82%)7 and availability of free screening services across the region, relatively few women have been screened for CCa: estimates are 4%–23% in rural areas7 8 and 9% in urban areas.7 A study of perceived barriers in access to cervical cancer screening (CCS) in the regions found that most women lacked awareness of the existence of preventive screening (67%), and many were concerned about affordability of both the cost of screening itself and travel costs (49%).7 Travel distance was a barrier more common among rural women than among urban women (27% vs 12%).7 These barriers contribute to 50%–80% of CCa diagnoses being at advanced stages.3 9 10

The primary objective of this randomised controlled trial was to evaluate the effectiveness of behaviour change communication (BCC) messages delivered via short message service (SMS) on the uptake of CCS in the Kilimanjaro and Arusha regions. The secondary objective was to evaluate the effectiveness of an electronic voucher (eVoucher) on the uptake of CCS in the Kilimanjaro and Arusha regions, delivered with an identical series of BCC SMS. The eVoucher was a code sent by SMS, to be redeemed for reimbursement of the return travel cost to the screening site.

Methods

Study setting and recruitment

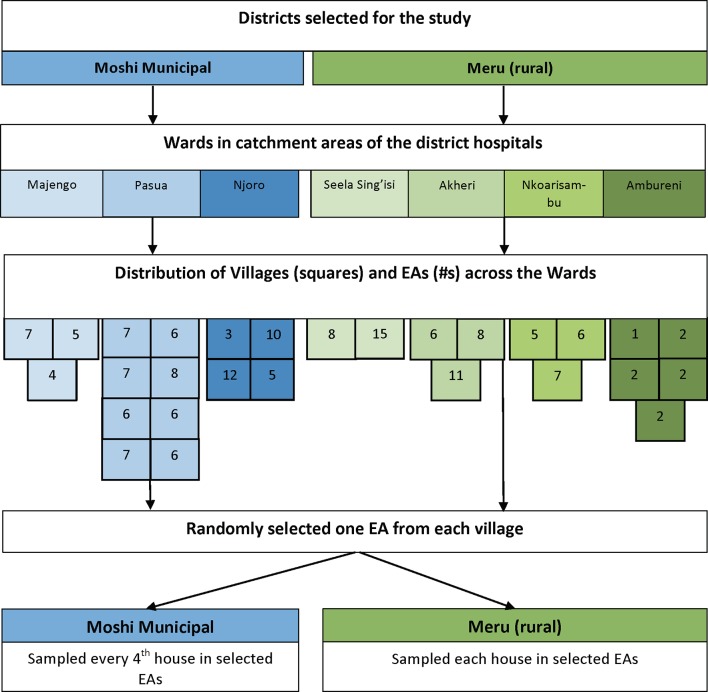

Tanzania is a low-income country in East Africa with a gross domestic product per capita of US$936, a life expectancy of 65.67 years and an estimated population of 57.3 million people.11 12 Kilimanjaro and Arusha are regions located in Northern Tanzania with populations of 1.6 and 1.7 million people, respectively.13 We chose one district from each of these regions: the Moshi Municipal District from the Kilimanjaro Region to represent urban areas, and the Arumeru District from the Arusha Region chosen to represent semiurban/rural areas. Meru District Hospital (Arumeru District) and Mawenzi Regional Referral Hospital (Moshi Municipal District) were the chosen hospitals with CCS. In Tanzania, each district is administratively divided into wards, and we consulted with hospital management to determine the wards in their catchment area. In Arumeru, all wards in the catchment area were included. In Moshi Municipal, wards non-adjacent to the hospital were included. We designed different ward inclusion strategies because of the different geographies of the areas. Moshi Municipal is a city centre and the wards in Moshi are geographically smaller but more densely populated, whereas Arumeru District is a semirural district where the wards are larger in area and less dense. Residents in the wards in Moshi Municipal closest to the hospital can easily walk to the hospital, whereas residents in the wards closest to the hospital in Arumeru could not. We obtained a list of villages for each ward and a list of enumeration areas (EA) for each village, and randomly selected one EA to represent each village within the identified wards using a random integer generator14 (see figure 1 for the sampling procedure).

Figure 1.

Sampling procedure of the study. EAs, enumeration areas.

The target study population included women between the ages of 25 and 49 years with access to a mobile phone living in the catchment areas of Mawenzi Regional Referral Hospital and Meru District Hospital. We used a customised, open-source Medic Mobile (San Francisco, California)15 software platform for data collection and to send the SMS. Fieldworkers used tablets for data collection, with data stored on encrypted tablets, an encrypted laptop and on an encrypted server. We recruited 863 women (n=471 in Moshi Municipal and n=395 in Arumeru District) using household door-to-door surveys, with each household identified using multistage systematic stratified random sampling (figure 1). In the rural area, we approached every household within the selected EAs. In the urban area, we approached every fourth household within the selected EAs.

Participants were randomised to (1) an SMS BCC message group, (2) an SMS + eVoucher group, or (3) a control group. Eligible women owned or had daily access to a mobile phone (a proxy phone). Participants could use a proxy phone if the owner was (1) present at the time of recruitment and (2) not eligible to participate. We excluded women who (1) were screened for CCa in the past year, (2) had a hysterectomy and (3) had a previous diagnosis of CCa. The attendance of a literate individual was required when recruiting an illiterate participant.

Based on prior studies we assumed that the attendance at CCS in the control arm would be less than 10%.7 Using the approach of Proschan16 to control the study-wise type I error rate at 0.05, we planned to compare each intervention arm with the control arm at a two-sided alpha=0.025, and then compare the two intervention arms if at least one intervention arm was significantly superior to the control arm. Calculations showed that about 270 women were required per arm to achieve 80% power to detect at least a 12% improvement in screening incidence, based on prior studies.17 During enrolment, we exceeded this sample size to provide greater power for secondary and exploratory analyses.

Randomisation

Unique study identifiers (USIDs) were generated by Medic Mobile to implement randomisation, which was otherwise unrestricted randomisation, in a 1:1:1 allocation ratio. USIDs were unique to each group, were randomly sorted in Excel, and the combined USIDs were distributed to fieldworkers. Following informed consent, the fieldworker assigned participants a USID.

Fieldworkers were not informed that the USIDs, which did not contain a detectable pattern, were used for randomisation. A software error causing duplication of some of the USIDs led to a greater chance of being allocated to the SMS + eVoucher group such that three-quarters of the way through recruitment fieldworkers were given more USIDs corresponding with the other groups to balance participants between arms; however, fieldworkers responsible for recruitment remained unaware of allocations so that blinding was maintained.

Interventions

Sensitisation methods commonly used in the regions were employed in the study area, including sensitisation via church announcements and posters and sensitisation from fieldworkers recruiting participants. We assumed that participants in all three intervention groups had the same potential to be exposed to this baseline community-based sensitisation.

SMS behaviour change message intervention group

The message schedule was designed to send a total of 15 unique SMS to SMS intervention group participants. Three SMS were sent at enrolment and one SMS sent every 1 or 2 days thereafter until day 21. Two additional SMS containing the location and dates of screening services were added following the mini-process evaluation, conducted a quarter of the way through data collection, which found that 25%–50% of the SMS were not reaching participants.

Draft SMS were informed by literature about barriers towards CCS in SSA and low- and middle-income countries7 8 18–20 and developed based on the Health Belief Model21 with extensive collaboration with laypeople and medical experts. A motivational tone was used for the BCC SMS based on research by de Tolly et al 22 on the higher effectiveness of motivational toned SMS versus an informational toned SMS in increasing uptake of HIV testing in South Africa. A medical translator translated the SMS into Swahili.

We conducted a total of five focus groups with community members and CCS nurses. Each focus group consisted of 6–10 participants and was conducted to ensure the content validity and cultural sensitivity of the SMS. The qualitative data were not formally analysed, however were used to modify the SMS and to select the final group of SMS.

SMS + eVoucher intervention group

The SMS + eVoucher group received identical BCC messages to the SMS group. The eVoucher was valid for 2 months, and we determined its value based on the location of the participant’s home and proximity to the screening site. The transportation eVoucher, delivered via SMS, covered return transportation, minibus or motorcycle taxi, to the nearest screening clinic. We sent also SMS + eVoucher group participants an SMS explaining that the eVoucher expired in 2 months and a reminder SMS a week before the voucher expired. The message schedule was adjusted to send the SMS containing the eVoucher a total of three times following the mini-process evaluation. We reimbursed participants who attended CCS in cash or by mobile phone-based money transfer.

Control group

The control group received one SMS (sent at three separate instances) with the location and hours of the closest screening clinic in addition to the sensitisation methods listed above. After the intervention period ended at 60 days, participants who had not attended CCS received BCC SMS identical to the intervention groups.

Follow-up

The primary outcome was attendance at CCS within 60 days recorded by a fieldworker posted in each clinic. Participants received cards with their USID at enrolment. Each woman attending screening during the follow-up period was asked if they were participating in the study, and if they said yes they were asked to either show their card or to provide their phone number that they used for registration.

Statistical analysis

The primary analysis and secondary exploratory analysis followed an intention-to-treat principle. We used logistic regression to determine ORs and 95% CIs to test the effectiveness of the interventions on CCS attendance after 60 days. All models accounted for stratification and clustering using the SURVEYLOGISTIC procedure. Logistic regression models calculated ORs and CIs for the urban and rural areas together and separately. The analysis was conducted using SAS V.9.4 software.

Results

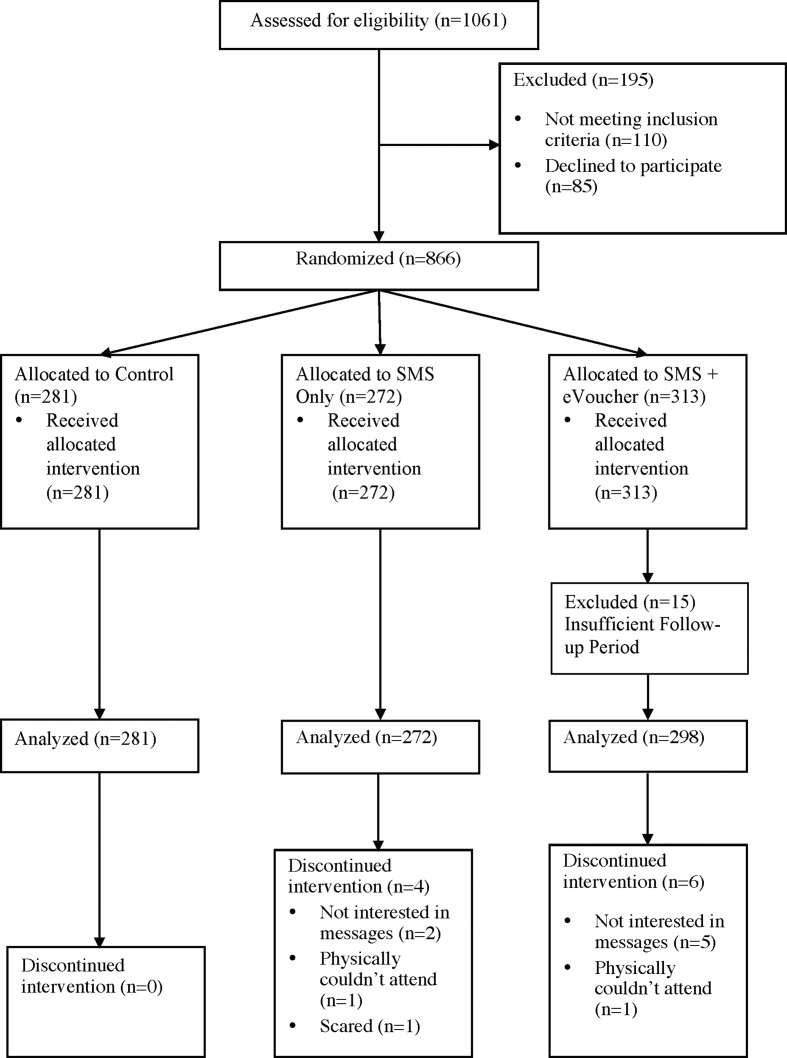

Participants were recruited between 1 February 2016 and 13 March 2016. Of the 1046 women assessed for eligibility, 866 consented and were randomised (see figure 2). Fifteen participants were excluded because of an insufficient follow-up period. The demographic characteristics of the study sample by intervention arm are shown in table 1. The mean age was 34 years and most had a partner or were married. Urban women had higher monthly household income than rural women, although rural women had higher self-reported health status. Overall, the randomisation was successful. The unrestricted nature of the randomisation led to slight imbalances in certain characteristics; however, any imbalances in the groups are due to chance, and therefore it is not appropriate to control for them in the analysis.

Figure 2.

CONSORT flow diagram. ‘Loss to follow-up’ has been omitted because it is not relevant to the study design. Analysis was conducted as intention-to-treat (those who discontinued the intervention were analysed as randomised). CONSORT, Consolidated Standards of Reporting Trials; eVoucher, electronic voucher; SMS, short message service.

Table 1.

Sociodemographic characteristics of the study sample by group

| Characteristics | Total (n=851) | Control (n=281) | SMS (n=272) | eVoucher (n=298) |

| % (n) | % (n) | % (n) | % (n) | |

| Age | ||||

| Mean (±SD) | 34.4 (7.2) | 34.4 (7.4) | 34.5 (7.1) | 34.4 (7.2) |

| Marital status | ||||

| Single | 11.5 (98) | 6.4 (18) | 9.9 (27) | 17.8 (53) |

| Partner/Married | 80.6 (686) | 84.7 (238) | 84.2 (229) | 73.5 (219) |

| Separated/Divorced/Widow | 7.8 (66) | 8.9 (25) | 5.9 (16) | 8.4 (25) |

| Declines to answer | 0.1 (1) | 0.3 (1) | ||

| Partnership type (of those partnered or married) | ||||

| Monogamy | 94.2 (646) | 96.2 (229) | 93.5 (214) | 92.7 (203) |

| Polygamy | 4.5 (31) | 2.1 (6) | 5.2 (12) | 5.9 (13) |

| Declines to answer | 1.3 (9) | 1.1 (3) | 1.3 (3) | 1.4 (3) |

| Religion | ||||

| Christian | 68.7 (585) | 71.2 (200) | 67.6 (184) | 67.4 (201) |

| Muslim | 31.3 (266) | 28.8 (81) | 32.4 (88) | 32.6 (97) |

| Tribe | ||||

| Chaga | 22.3 (190) | 22.8 (64) | 24.6 (67) | 19.8 (59) |

| Pare | 11.8 (101) | 13.9 (39) | 8.8 (24) | 12.8 (38) |

| Maasai | 4.6 (39) | 3.9 (11) | 4.0 (11) | 5.7 (17) |

| Meru | 25.6 (218) | 25.3 (71) | 25.0 (68) | 26.5 (79) |

| Other | 35.1 (299) | 33.8 (95) | 37.5 (102) | 34.2 (102) |

| Declines to answer | 0.5 (4) | 0.4 (1) | 1.0 (3) | |

| Monthly household income (Tanzanian shillings) | ||||

| 0–39 999 | 13.7 (117) | 12.8 (36) | 13.9 (38) | 14.4 (43) |

| 40 000–59 999 | 24.2 (206) | 22.1 (62) | 23.9 (65) | 26.5 (79) |

| 60 000–99 999 | 25.6 (218) | 27.0 (76) | 25.4 (69) | 24.5 (73) |

| ≥100 000 | 31.7 (269) | 35.2 (99) | 30.1 (82) | 29.5 (88) |

| Declines to answer | 4.8 (41) | 2.8 (8) | 6.6 (18) | 5.0 (15) |

| Occupation | ||||

| Housewife/Farmer | 37.1 (316) | 35.6 (100) | 41.5 (113) | 34.6 (103) |

| Small business | 50.6 (431) | 51.6 (145) | 47.1 (128) | 53.0 (158) |

| Professional | 3.8 (32) | 3.6 (10) | 3.7 (10) | 4.0 (12) |

| Other | 8.1 (69) | 9.3 (26) | 7.7 (21) | 7.4 (22) |

| Declines to answer | 0.4 (3) | 1.0 (3) | ||

| Highest level of education | ||||

| Primary or lower | 73.3 (624) | 71.5 (201) | 72.4 (197) | 75.8 (226) |

| Secondary | 20.3 (173) | 20.3 (57) | 22.1 (60) | 18.8 (56) |

| College/University | 6.0 (51) | 8.2 (23) | 4.4 (12) | 5.4 (16) |

| Declines to answer | 0.4 (3) | 1.1 (3) | ||

| Mobile phone ownership | ||||

| Own | 74.4 (633) | 73.7 (207) | 75.7 (206) | 73.8 (220) |

| Other’s | 14.8 (126) | 14.6 (41) | 15.4 (42) | 14.4 (43) |

| Unknown | 10.8 (92) | 11.7 (33) | 8.8 (24) | 11.7 (35) |

SMS, short message service; eVoucher, electronic voucher.

During the 60-day follow-up period, overall 101 study participants (11.9%) attended CCS. The highest proportion of women attending screening were in the SMS + eVoucher group (18%, n=54), followed by 12.9% in the SMS group (n=35) and 4.3% in the control group (n=12). Participants in the intervention groups were more likely to attend CCS than participants in the control group (SMS + eVoucher adjusted OR [AOR] 4.7, 95% CI 2.9 to 7.4; SMS AOR 3.0, 95% CI 1.5 to 6.2), and those in the SMS + eVoucher group were more likely to attend CCS than women in the SMS group (SMS + eVoucher AOR 1.5, 95% CI 1.1 to 2.2) (table 2). Although both interventions were significant in both urban and rural areas, the intervention effects of the SMS and SMS + eVoucher interventions in the rural area were more pronounced than in the urban area. The analyses of the urban and rural areas separately are presented in tables 3 and 4, respectively.

Table 2.

Results for cervical cancer screening attendance—combined urban and rural

| Predictor | Crude OR | Adjusted OR | Adjusted OR 95% Wald confidence limits |

|

| SMS vs control | 3.31 | 3.04 | 1.49 | 6.21 |

| SMS + eVoucher vs control | 4.96 | 4.67 | 2.93 | 7.44 |

| SMS + eVoucher vs SMS | 1.50 | 1.53 | 1.11 | 2.19 |

The adjusted OR was adjusted for age, stratification and clustering.

SMS, short message service; eVoucher, electronic voucher.

Table 3.

Results for cervical cancer screening attendance for Moshi Municipal (urban)

| Predictor | Crude OR | Adjusted OR | Adjusted OR 95% Wald confidence limits |

|

| SMS vs control | 2.59 | 2.12 | 1.16 | 3.86 |

| SMS + eVoucher vs control | 4.48 | 3.42 | 2.63 | 4.44 |

| SMS + eVoucher vs SMS | 1.73 | 1.61 | 1.03 | 2.54 |

The adjusted OR was adjusted for clustering.

SMS, short message service; eVoucher, electronic voucher.

Table 4.

Results for cervical cancer screening attendance for Meru (rural)

| Predictor | Crude OR | Adjusted OR | Adjusted OR 95% Wald confidence limits |

|

| SMS vs control | 7.05 | 6.12 | 1.56 | 24.0 |

| SMS + eVoucher vs control | 10.9 | 8.78 | 2.88 | 26.8 |

| SMS + eVoucher vs SMS | 1.55 | 1.44 | 0.96 | 2.14 |

The adjusted OR was adjusted for clustering.

SMS, short message service; eVoucher, electronic voucher.

Discussion

Research investigating the impact of SMS messaging to increase uptake of cervical and breast cancer screening services has been conducted in other settings.23 24 We believe this is the only study investigating the provision of transportation vouchers (electronic or paper-based) to increase uptake of CCS in Tanzania. The strengths of this trial include the sample being intended to be representative of the Kilimanjaro and Arusha regions, and the results being generalisable to other regions with similar patterns of mobile phone use and sociodemographic characteristics.

Three factors may help explain the larger ORs in the rural areas versus the urban area for both the SMS and SMS + eVoucher interventions. First, in a previous study conducted in the same region, greater perceived travel barriers were reported in the rural areas versus the urban areas.7 This consideration pertains largely to the SMS + eVoucher intervention. Second, the rural area exhibited a lower level of baseline knowledge (9%) than the urban area (18%).7 This difference could have amplified the effects of the SMS behaviour change in the rural area. Lastly, a lower baseline rate of screening in Arumeru (4% vs 7% in Moshi Municipal) could also help to explain the greater impact of both interventions (SMS and SMS + eVoucher) in the rural area.

We conducted a mini-process evaluation a quarter of the way through data collection. In this evaluation, we found that 50%–75% of the SMS were received by participants, and half of eVoucher participants received the eVoucher SMS. This was due to a variety of reasons, including mobile network coverage issues. To resolve this, select important messages were sent three times to the participants and the follow-up period was extended from 30 to 60 days. We discovered in the same mini-process evaluation that women in the control group thought that they needed to wait to go for screening until they received an SMS. As part of explaining the study, they had been told that they would be receiving SMS at some point; however, some misunderstood and thought that they had to wait until they received an SMS to go for screening. To mitigate this, we therefore sent control participants who were already enrolled an SMS with the dates and locations and control participants an SMS as they were enrolled into the study.

The pragmatic nature of this trial led to some methodological limitations. The nature of the intervention made it impossible for the coordinator or clinic fieldworkers to be blinded. Although participants were not informed of their intervention group, contamination between groups could have resulted if participants communicated. Fifteen participants had an insufficient follow-up period because they were recruited at the end of the recruitment period and the study was ended for budgetary reasons prior to completion of their follow-up period. A further limitation was that due to the mobile health (mHealth) nature of our interventions, we were unable to enrol women in the lowest socioeconomic status. As mobile phone ownership becomes increasingly pervasive, this inequity may be ameliorated.25 Attention must be devoted to equity in order to avoid marginalising disenfranchised groups.26

Previous SMS behaviour change interventions have demonstrated that two-way SMS interventions are more effective than one-way interventions.26 Due to budgetary limitations, we could not include built-in, two-way SMS capabilities to the mHealth platform. In our study, participants called/texted the phone number sending the messages. A fieldworker was responsible for answering questions/concerns either via text or voice and for logging the communication. When this intervention or similar interventions are scaled up, it should be ensured greater capacity is available to facilitate two-way communication between participants and study officials.

Conclusion

These results show the potential for SMS focusing on behaviour change and eVouchers for transportation costs to increase uptake of CCS in Tanzania and in similar settings. Due to the wide variety of barriers to CCS, and the fear and misconceptions that surround CCa, it is unsurprising that, although the SMS intervention was effective, the change in uptake was relatively modest. Health/cancer educational initiatives involving inperson contact are required to address the more fear-inducing and sensitive aspects of education and counselling surrounding CCa. Harnessing the potential of these mHealth interventions requires a multifaceted, equity-focused approach which includes interpersonal elements.

Acknowledgments

We thank the study participants for their participation and trust, and our fieldwork team for their dedication to the project.

Footnotes

Contributors: All authors have made substantive intellectual contributions to this randomised controlled trial. EE designed the study in collaboration with KJA and KY. AF, GM, OO and PDM made significant contributions to the survey tools and SMS. EE was the main implementer of the study, assisted by KY, JS and NW. PDM led the fieldwork team to conduct all recruitment and data collection. AD assisted with the preparation of the analysis plan, and AD and KJA supervised EE in conducting the analysis. GM and AF managed the screening clinics where participants attended and ensured that clinic data collection proceeded according to protocol. BM facilitated regional cooperation on the trial. EE initiated the first draft of the manuscript, to which a number of iterations followed, with contributions from all authors and particularly significant contributions from OG, KJA, AD, NW, BM and KY. All authors approved the final version of the manuscript.

Funding: The Terry Fox Foundation and the Canadian Institutes of Health Research provided a studentship to EE through the Training Program in Transdisciplinary Cancer Research. This research was conducted in partial fulfilment of the requirements for a master's degree by EE.

Competing interests: None declared.

Patient consent for publication: Obtained.

Ethics approval: The study was approved by the Human Ethics Review Board of Queen’s University (60155) and the National Institute of Medical Research, Tanzania (R.8a/Vol. IX/1716).

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

References

- 1. Narh-Bana SA, Chirwa TF, Mwanyangala MA, et al. . Adult deaths and the future: a cause-specific analysis of adult deaths from a longitudinal study in rural Tanzania 2003-2007. Trop Med Int Health 2012;17:1396–404. 10.1111/j.1365-3156.2012.03080.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Defo BK, Demographic B. Demographic, epidemiological, and health transitions: are they relevant to population health patterns in Africa? Glob Health Action 2014;7 10.3402/gha.v7.22443 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Foundation for Cancer Care in Tanzania Meeting the challenge of cancer care in northern Tanzania. 64, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- 4. Morhason-Bello IO, Odedina F, Rebbeck TR, et al. . Challenges and opportunities in cancer control in Africa: a perspective from the African Organisation for research and training in cancer. Lancet Oncol 2013;14:e142–51. 10.1016/S1470-2045(12)70482-5 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. International Agency for Research on Cancer World cancer report 2014. WHO, 2014: 1–632. [Google Scholar]

- 6. International Agency for Research on Cancer Cancer today. GCO: Cancer Today. Available: http://gco.iarc.fr/today/home [Accessed 6 Dec 2016].

- 7. Cunningham MS, Skrastins E, Fitzpatrick R, et al. . Cervical cancer screening and HPV vaccine acceptability among rural and urban women in Kilimanjaro region, Tanzania. BMJ Open 2015;5 10.1136/bmjopen-2014-005828 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Lyimo FS, Beran TN. Demographic, knowledge, attitudinal, and accessibility factors associated with uptake of cervical cancer screening among women in a rural district of Tanzania: three public policy implications. BMC Public Health 2012;12 10.1186/1471-2458-12-22 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Mlange R, Matovelo D, Rambau P, et al. . Patient and disease characteristics associated with late tumour stage at presentation of cervical cancer in northwestern Tanzania. BMC Womens Health 2016;16 10.1186/s12905-016-0285-7 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. George W. Bush Presidential Center Tanzania | pink ribbon | red ribbon. Available: http://pinkribbonredribbon.org/where-we-work/tanzania/ [Accessed 30 Nov 2016].

- 11. World Bank Tanzania | data. Available: http://data.worldbank.org/country/tanzania [Accessed 22 May 2017].

- 12. United Nations Development Programme Human development reports. Tanzania human development report. Available: http://hdr.undp.org/en/countries/profiles/TZA [Accessed 24 May 2017].

- 13. National Bureau of Statistics Basic Demographic and Socio-Economic Profile: Key Findings of the 2012 Tanzanian Population and Housing Census, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- 14. Randomness and Integrity Services , 2015. random.org. Available: https://www.random.org/integers/

- 15. Medic mobile. Available: www.medicmobile.org [Accessed 19 Jan 2017].

- 16. Proschan MA. A multiple comparison procedure for three- and four-armed controlled clinical trials. Statistics in Medicine 1999;18:787–98. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Noor FR, Talukder NM, Rob U. Effect of a maternal health voucher scheme on out-of-pocket expenditure and use of delivery care services in rural Bangladesh: a prospective controlled study. The Lancet 2013;382 10.1016/S0140-6736(13)62181-9 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Kahesa C, Kjaer S, Mwaiselage J, et al. . Determinants of acceptance of cervical cancer screening in Dar es Salaam, Tanzania. BMC Public Health 2012;12 10.1186/1471-2458-12-1093 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Urasa M, Darj E. Knowledge of cervical cancer and screening practices of nurses at a regional hospital in Tanzania. Afr Health Sci 2011;11:48–57. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Perng P, Perng W, Ngoma T, et al. . Promoters of and barriers to cervical cancer screening in a rural setting in Tanzania. Int J Gynaecol Obstet 2013;123:221–5. 10.1016/j.ijgo.2013.05.026 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Rosenstock IM. The health belief model and preventive health behavior. Health Educ Monogr 1974;2:354–86. 10.1177/109019817400200405 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 22. de Tolly K, Skinner D, Nembaware V, et al. . Investigation into the use of short message services to expand uptake of human immunodeficiency virus testing, and whether content and dosage have impact. Telemedicine and e-Health 2012;18:18–23. 10.1089/tmj.2011.0058 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Khokhar A. Short text messages (SMS) as a reminder system for making working women from Delhi breast aware. Asian Pac J Cancer Prev 2009;10:319–22. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Lee HY, Koopmeiners JS, Rhee TG, et al. . Mobile phone text messaging intervention for cervical cancer screening: changes in knowledge and behavior pre-post intervention. J Med Internet Res 2014;16 10.2196/jmir.3576 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Raifman JRG, Lanthorn HE, Rokicki S, et al. . The impact of text message reminders on adherence to antimalarial treatment in northern Ghana: a randomized trial. PLoS One 2014;9:e109032 10.1371/journal.pone.0109032 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Hall AK, Cole-Lewis H, Bernhardt JM. Mobile text messaging for health: a systematic review of reviews. Annu Rev Public Health 2015;36:393–415. 10.1146/annurev-publhealth-031914-122855 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]