Abstract

Human NK cell anti-tumor activities involve antibody-dependent cell-mediated cytotoxicity (ADCC), which is a key mechanism of action for several clinically successful tumor-targeting therapeutic mAbs. Human NK cells exclusively recognize these antibodies by the Fcγ receptor CD16A (FcγRIIIA), one of their most potent activating receptors. Unlike other activating receptors on NK cells, CD16A undergoes a rapid downregulation in expression by a proteolytic process following NK cell activation with various stimuli. In this review, the role of a disintegrin and metalloproteinase-17 (ADAM17) in CD16A cleavage and as a regulatory checkpoint is discussed. Several studies have examined the effects of inhibiting ADAM17 or CD16A cleavage directly during NK cell engagement of antibody-coated tumor cells, which resulted in strengthened antibody tethering, decreased tumor cell detachment, and enhanced CD16A signaling and cytokine production. However, the effects of either manipulation on ADCC has varied between studies and this is likely due to dissimilar assays and the contribution of different killing processes by NK cells. Of importance is that NK cells under various circumstances, including in the tumor microenvironment of patients, downregulate CD16A and this appears to impair their function. Considerable progress has been made in the development of ADAM17 inhibitors, including human mAbs that have advantages of high specificity and increased half-life in vivo. These inhibitors may provide a therapeutic means of increasing ADCC potency and/or anti-tumor cytokine production by NK cells in an immunosuppressive tumor microenvironment, and if used in combination with tumor-targeting antibodies or NK cell-based adoptive immunotherapies may improve their efficacy.

Summary Sentence:

ADAM17 checkpoint inhibitors provide a therapeutic option to increase NK cell effector functions in an immunosuppressive tumor microenvironment.

CD16A-mediated ADCC by human NK cells.

NK cells are a very heterogenous population of lymphocytes of the innate immune system [1]. They mediate direct and indirect cytolytic activities against tumor cells and virus-infected cells without prior sensitization and release various immune-modulating cytokines, as described in more detail in other reviews [2–5]. Direct target cell killing (natural cytotoxicity) by NK cells is tightly controlled by numerous activating and inhibitory receptors [2, 5]. NK cells also mediate indirect killing by recognizing antibody-opsonized target cells, referred to as ADCC [3, 4]. IgG antibodies are recognized by leukocytes that express receptors for the Fc portion of the antibody, referred to as a FcγR. In humans, there are 3 classes of FcγRs: FcγRI (CD64), FcγRII (CD32), and FcγRIII (CD16) [6, 7]. The latter preferentially recognizes IgG1 and IgG3 and consists of two isoforms (CD16A and CD16B) that are encoded by two highly homologous genes [6]. CD16B is primarily expressed by neutrophils and CD16A is expressed at high levels by mature NK cells in the peripheral blood. CD16A is the sole activating FcγR on NK cells and upon binding to antibody-opsonized target cells induces NK cell degranulation and the release of their lytic components, as well as the production of various cytokines and chemokines (Fig. 1). CD16A has a low to intermediate affinity for IgG that varies between its allelic variants. For instance, CD16A with a valine at position 176 (position 158 if amino acid enumeration does not include the signal sequence) has a higher affinity for IgG than the allelic variant CD16A with a phenylalanine at position 176 [8, 9]. Incidentally, the latter is the dominant allele in humans [10]. Clinical analyses have revealed a positive correlation between the efficacy of tumor-targeting therapeutic mAbs and CD16A binding affinity. Patients homozygous for the higher affinity CD16A valine allele (CD16A-176V/V) had an improved clinical outcome after treatment with anti-tumor mAbs compared to those with heterozygous (CD16A-176V/F) or homozygous (CD16A-176F/F) genotypes containing the lower affinity CD16A-F allele [3]. These findings suggest that increasing the attachment strength between NK cells and antibody-opsonized tumor cells increases killing.

Figure 1. Antibody-dependent cell-mediated cytotoxicity (ADCC) by human NK cells.

Tumor-targeting therapeutic mAbs are solely recognized by the Fcγ receptor CD16A (FcγRIIIA) on human NK cells, which induces their activation and release of cytotoxic components and various immune-modulating cytokines.

Regulation of CD16A surface density by ADAM17.

Unlike other activating receptors expressed by NK cells, CD16A surface expression undergoes a rapid downregulation within minutes when induced by the engagement of antibody-coated target cells, through other activating receptors, and by various cytokines [11–15]. Trinchieri et al. initially reported that CD16A is rapidly downregulated in expression upon NK cell activation with a phorbol ester [16]. Others subsequently showed that CD16A release by NK cells was mediated by a metalloprotease [11, 17, 18]. Both allelic variants of CD16A undergo this cleavage process upon NK cell activation [19]. There has been some controversy, however, in the proteolytic mechanism involved. Some studies have suggested the role of matrix metalloproteinases (MMPs) [20, 21], such as membrane-type 6 MMP [14]. More recently, several studies have shown that highly selective inhibitors of ADAM17, also referred to as TNFα converting enzyme (TACE), block CD16A cleavage upon NK cell activation by various means [12, 13, 15, 19, 22]. Moreover, Tsukerman et al. reported that NK cells obtained from a patient lacking ADAM17 expression did not downregulate CD16A during ADCC [23]. The mouse homologue of this receptor is not downregulated by a proteolytic process following leukocyte activation and therefore the role of ADAM17 cannot be further established using normal mice [12].

Unlike CD16A, which is a transmembrane protein, CD16B is linked to the plasma membrane via a GPI anchor [24, 25]. Interestingly though, CD16B is also cleaved from the cell surface following neutrophil activation [26–31], and this was found to be blocked ex vivo and in cancer patients by selective ADAM17 inhibitors and is also prevented in ADAM17-deficient cells [12]. Taken together, the above findings provide strong evidence that ADAM17 is the primary protease involved in CD16 cleavage. Moreover, soluble CD16 occurs at high levels in the plasma of healthy individuals [11, 12, 27, 32], establishing that its cleavage is a physiological process.

ADAM17 is a member of the adamalysin subfamily of the metzincin metalloproteinase superfamily, which contain a conserved methionine amino acid adjacent to a zinc-binding motif in the catalytic region of the proteases [33, 34]. The ADAMs are type-1 transmembrane proteins with distinct modular domains that include an N-terminus metalloproteinase domain, disintegrin-like domain, cysteine-rich domain, an epidermal growth factor domain, which ADAM17 happens to lack, and transmembrane and cytoplasmic regions [35]. Greater than 20 ADAMs have been identified in humans, though 12 are proteolytically active [34]. ADAM17 is constitutively expressed on the surface of NK cells [13, 15, 22], and it cleaves its substrates typically in a cis manner at an extracellular location proximal to the cell membrane [35]. A single cleavage site has been identified in CD16A released from activated human NK cells, located between alanine-195 and valine-196 [19] (Fig. 2). A synthesized peptide of CD16A was also cleaved by recombinant ADAM17 at the same location [15]. Three cleavage sites in very close proximity were identified in the membrane proximal region of CD16B released from activated neutrophils [19]. This variability in where CD16B is cleaved may be the result of the receptor’s GPI linkage to the plasma membrane, perhaps causing fluctuation in its interaction with the catalytic domain of ADAM17. ADAM17 does not require a strict consensus sequence in its substrates and instead tends to prefer a cleavage region of sufficient physical length with an α-helical conformation [36–38]. We have shown that either truncating the length of the membrane proximal cleavage region of CD16A (data unpublished) or substituting the serine at position 197 adjacent to the ADAM17 cleavage site for a proline (referred to as CD16A-S197P, Fig. 2) completely disrupts its cleavage in cell-based assays [19].

Figure 2. CD16A is cleaved by ADAM17.

CD16A cleavage occurs at a specific extracellular location proximal to the cell membrane, as indicated. Exchange of serine-197 for a proline residue prevents CD16A cleavage by ADAM17.

Of interest is that ADAM17 induction can occur very quickly following leukocyte activation [35]. For most stimuli, serine and threonine kinase-dependent intracellular signaling pathways are involved, including PKC and the MAPKs [39–42]. The rapid activation of ADAM17 in leukocytes involves an increase in its intrinsic activity instead of an upregulation in protease expression, but the targets of the kinases involved in this process remain an active area of debate. Various potential mechanisms of ADAM17 activation in leukocytes have been discussed in recent reviews [35, 43].

Role of CD16A cleavage in NK cell regulation.

CD16A binds to IgG with low to intermediate affinity but achieves a higher binding avidity through multimeric interactions with antibodies on target cells [44]. The rapid cleavage of CD16A by ADAM17 may provide a means of quickly decreasing its binding avidity to antibody-coated target cells. Of interest is that NK cells in the presence of an ADAM17 inhibitor or NK92 cells expressing CD16A-S197P demonstrated reduced mobility on an IgG-coated surface and decreased detachment from antibody-bound target cells [45]. These phenomena resemble the effects of blocking L-selectin cleavage on leukocyte attachment to endothelial cells. L-selectin (CD62L) is also a low affinity receptor that is constitutively expressed at high levels by leukocytes [46, 47], and is a well described ADAM17 substrate [35, 47, 48]. Blocking its cleavage reduces leukocyte mobility on L-selectin ligands and increases their attachment to endothelial cells in vivo [49–51].

CD16A associates with Fcγ (FcεRIγ) and/or CD3ζ chains and is perhaps the NK cell’s most potent activating receptor [3]. Indeed, CD16A alone can trigger degranulation of resting human NK cells, whereas NKG2D and the natural cytotoxicity receptors induce NK cell activation by working together [52, 53]. Inhibitory receptors transmit negative signals and dampen or counteract most activating receptors in NK cells, whereas CD16A is capable of overcoming inhibitory signals [53, 54]. Several studies have shown that blocking CD16A cleavage can increase the intensity and duration of receptor signaling and the production of IFNγ by NK cells [13, 22, 45, 55].

In contrast to the effects of blocking CD16A cleavage on antibody tethering and receptor signaling, the effects on ADCC by NK cells is less clear. Several studies have shown that blocking CD16A cleavage increases NK cell attachment to antibody-coated target cells, degranulation, and ADCC [14, 21, 55, 56], whereas others, including us, have reported that blocking CD16A cleavage either did not affect ADCC or decreased it [13, 22, 45]. For instance, Srpan et al. showed that blocking CD16A cleavage decreased the rate of NK cell detachment from antibody-bound tumor cells and as a result limited their ability to kill in a sequential (serial) manner [45]. This discrepancy between studies maybe the result of differences in the way the in vitro ADCC assays were performed, the NK cell to tumor cell ratios used, or in the killing process by individual NK cells. In addition to serial killing, an NK cell can kill surrounding cells in an indiscriminate manner referred to as bystander killing [57, 58]. At this time, the effects of blocking ADAM17 or directly disrupting CD16A cleavage on the anti-tumor effector functions of NK cells in vivo remain to be determined.

ADAM17 as a regulatory checkpoint of ADCC by NK cells.

Immune checkpoints are important for maintaining immune homeostasis to prevent excessive tissue damage while the immune system responds against its targets. ADAM17 appears to function as a regulatory checkpoint of CD16A, facilitating the detachment of NK cells from antibody-coated target cells and diminishing signal transduction by this potent activating receptor. Malignant cells, however, can exploit immune checkpoints to suppress anti-tumor immunity. This may be the case for ADAM17 on NK cells as well. For instance, cell surface levels of CD16A on NK cells can be downregulated in the tumor microenvironment of patients, contributing to NK cell dysfunction [59, 60]. CD16A downregulation also occurs on circulating NK cells in individuals receiving tumor-targeting therapeutics antibodies [61, 62], and by NK cells during their ex vivo expansion for adoptive transfer into cancer patients [63]. Blocking ADAM17 activity in these situations may enhance the effector functions of NK cells within the tumor microenvironment. Indeed, ADCC potency by NK cells has been shown to positively correlate with CD16A expression levels [21, 64, 65]. Blocking ADAM17 may also improve the therapeutic efficacy of expanded NK cells for adoptive transfer and tumor-targeting mAbs that induce ADCC. Similar to the effects of blocking L-selectin cleavage, which increases neutrophil attachment levels and binding strength to endothelial cells [50, 51], blocking CD16A cleavage may increase NK cell attachment levels and binding strength to antibody-coated target cells, which may increase the likelihood of killing the most resilient cancer cells in an immunosuppressive tumor microenvironment.

Blocking ADAM17 could enhance the anti-tumor activity of NK cells in other ways as well. CD16A on NK cells has also been reported to mediate cell killing independent of antibody recognition, referred to as spontaneous cytotoxicity [66, 67]. This occurs by CD16A interacting in a cis manner with the NK cell receptor CD2 that recognizes CD58 on particular target cells, such as melanoma cells [67]. Thus, blocking CD16A cleavage may also enhance NK cell killing of certain cancer cells independent of ADCC. NKG2D is another activating receptor broadly expressed by all mature human NK cells and its ligands include MHC class I-related chain molecules A and B (MICA and MICB) and non-MHC-encoded UL16-binding proteins (ULBPs), which are widely expressed by tumor cells [68]. MICA and MICB are reported to be substrates of ADAM17 and their cleavage can impair NK cell activity [69–71]. Blocking ADAM17 may decrease the inhibitory effects of soluble NKG2D ligands and increase NKG2D binding to its ligands on tumor cells. In addition, ADAM17 has been shown to be overexpressed in cancer cells and cause their release of EGFR ligands and adhesion molecules that promote growth and metastasis [72–76]. Taken together, blocking ADAM17 activity may impair tumor cell growth and survival in various direct and indirect manners.

There have been broad efforts to develop ADAM17 inhibitors [76, 77], with a particular focus on preventing tumor cell growth and spread [72–76]. Initial efforts were on the development of selective small-molecule inhibitors. Though early toxicity issues have been addressed by improving their specificity, the small-molecule ADAM17 inhibitors have not been found to be clinically successful thus far. More recently there has been considerable advances in generating function-blocking antibodies of ADAM17 that have greater specificity and a longer half-life in vivo [78–83]. For instance, MEDI3622 produced by Medimmune is noteworthy in that its epitope has been mapped to a surface loop unique to the catalytic domain of ADAM17, resulting in exquisite specificity and a potent inhibitory activity [84]. MEDI3622 was originally developed to impair EGFR-dependent tumor growth [82], but recently has been shown to block CD16A cleavage from activated human NK cells and markedly enhance their production of IFNγ during ADCC [22]. This occurred for NK cells exposed to different tumor cell lines and therapeutic antibodies, and over a broad range of NK cell/target cell ratios. IFNγ has broad anti-tumor effector functions, which includes recruiting innate and adaptive leukocytes, upregulating ICAM-1 and MHC molecules on tumor cells to facilitate leukocyte attachment and activation, and suppressing cell proliferation and angiogenesis in tumors [85–88].

Concluding remarks.

CD16A is a potent activating receptor on NK cells and it has an exclusive role in their ADCC effector function. Of importance is that several clinically successful tumor-targeting antibodies utilize ADCC as a primary mechanism of action [3, 89]. However, despite having a significant impact on some malignancies, most cancer patients respond poorly or develop resistance to this therapy. As detailed above, ADAM17 embodies a regulatory checkpoint of CD16A in NK cells. Its activation results in rapid CD16A cleavage, which abates NK cell attachment to antibody-coated target cells and diminishes CD16A signaling. NK cells in the tumor microenvironment of patients have reduced levels of CD16A on their cell surface [59, 60], indicating increased ADAM17 activity and a dysregulation of this immune checkpoint. Checkpoint inhibitors for cancer immunotherapies are intended to promote a robust and durable immune response in immunosuppressive tumor microenvironments. Function blocking ADAM17 mAbs may be beneficial in part by diminishing CD16A downregulation by tumor-infiltrating NK cells and maintaining their ADCC effector function, and perhaps could be used in combination with tumor-targeting mAbs or adoptively transferred NK cells for treating diverse malignancies. As can be the case with targeting regulatory checkpoints, blocking ADAM17 for prolonged periods of time could have detrimental effects. Indeed, ADAM17 gene-targeting in mice and loss-of-function mutations in ADAM17 in humans can cause inflammatory diseases [90, 91]. Another approach is to specifically block CD16A cleavage by expressing a non-cleavable version of the receptor, such as CD16A-S197P, in engineered NK cells. Various autologous and allogeneic NK cell platforms could be utilized, including expanded peripheral blood NK cells, NK cell lines, and stem cell-derived NK cells, that offer different advantages [92–94]. A potential limitation of this approach is that NK cells expressing non-cleavable CD16A might be less efficient at serial killing of antibody-coated tumor cells in vivo. However, it is also possible that non-cleavable CD16A may further stabilize and increase NK cell attachment to tumor cells in the tumor microenvironment for more effective killing of the more resilient cancer cells. This manipulation may also increase or extended CD16A signaling to boost NK cell activation and their degranulation for killing of surrounding cancer cells and/or their production of anti-tumor cytokines. Moreover, for adoptive cell immunotherapies, lymphocytes are administered in large numbers to increase effector to target cell ratios, and under these conditions, serial killing may play less of a role in ADCC. None-the-less, there is much that needs to be elucidated about the potential benefits and detriments of blocking ADAM17 activity and CD16A cleavage on ADCC by NK cells in vivo.

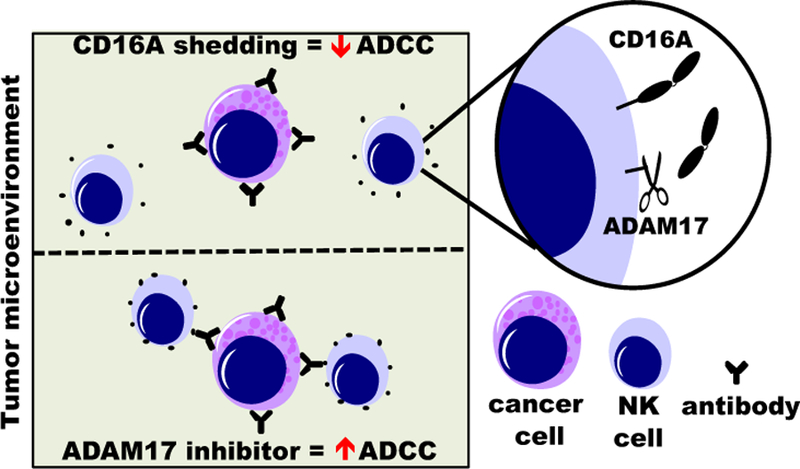

Figure 3. Illustration of CD16A cleavage in the tumor microenvironment and impairment of ADCC by NK cells.

Blocking ADAM17 in NK cells may reduce CD16A downregulation on tumor infiltrating NK cells and increase their ADCC potency.

Acknowledgments

Research in the authors’ laboratory is funded by the National Institutes of Health, including the current grant R01HL128580, R01CA203348 and R21AI125729, and the Minnesota Ovarian Cancer Alliance. The authors wish to acknowledge Ms. Kristin Snyder for her editing assistance.

Abbreviations

- ADAM17

a disintegrin and metalloproteinase-17

- TACE

TNFα converting enzyme

- ADCC

antibody-dependent cell-mediated cytotoxicity

- MMPs

matrix metalloproteinases

Footnotes

Conflict of Interest Disclosure

The authors declare no conflict of interest

References.

- 1.Horowitz A, Strauss-Albee DM, Leipold M, Kubo J, Nemat-Gorgani N, Dogan OC, Dekker CL, Mackey S, Maecker H, Swan GE, Davis MM, Norman PJ, Guethlein LA, Desai M, Parham P, Blish CA. (2013) Genetic and environmental determinants of human NK cell diversity revealed by mass cytometry. Sci Transl Med 5, 208ra145. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Long EO, Kim HS, Liu D, Peterson ME, Rajagopalan S. (2013) Controlling natural killer cell responses: integration of signals for activation and inhibition. Annu Rev Immunol 31, 227–58. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Wang W, Erbe AK, Hank JA, Morris ZS, Sondel PM. (2015) NK Cell-Mediated Antibody-Dependent Cellular Cytotoxicity in Cancer Immunotherapy. Front Immunol 6, 368. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Battella S, Cox MC, Santoni A, Palmieri G. (2016) Natural killer (NK) cells and anti-tumor therapeutic mAb: unexplored interactions. J Leukoc Biol 99, 87–96. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Paul S and Lal G. (2017) The Molecular Mechanism of Natural Killer Cells Function and Its Importance in Cancer Immunotherapy. Front Immunol 8, 1124. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Nimmerjahn F and Ravetch JV. (2008) Fcgamma receptors as regulators of immune responses. Nature reviews. Immunology 8, 34–47. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Bruhns P. (2012) Properties of mouse and human IgG receptors and their contribution to disease models. Blood 119, 5640–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Wu J, Edberg JC, Redecha PB, Bansal V, Guyre PM, Coleman K, Salmon JE, Kimberly RP. (1997) A novel polymorphism of FcgammaRIIIa (CD16) alters receptor function and predisposes to autoimmune disease. J Clin Invest 100, 1059–70. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Koene HR, Kleijer M, Algra J, Roos D, von dem Borne AE, de Haas M. (1997) Fc gammaRIIIa-158V/F polymorphism influences the binding of IgG by natural killer cell Fc gammaRIIIa, independently of the Fc gammaRIIIa-48L/R/H phenotype. Blood 90, 1109–1114. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Dong C, Ptacek TS, Redden DT, Zhang K, Brown EE, Edberg JC, McGwin G Jr., Alarcon GS, Ramsey-Goldman R, Reveille JD, Vila LM, Petri M, Qin A, Wu J, Kimberly RP. (2014) Fcgamma receptor IIIa single-nucleotide polymorphisms and haplotypes affect human IgG binding and are associated with lupus nephritis in African Americans. Arthritis & rheumatology 66, 1291–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Harrison D, Phillips JH, Lanier LL. (1991) Involvement of a metalloprotease in spontaneous and phorbol ester-induced release of natural killer cell-associated Fc gamma RIII (CD16-II). J Immunol 147, 3459–3465. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Wang Y, Wu J, Newton R, Bahaie NS, Long C, Walcheck B. (2013) ADAM17 cleaves CD16b (FcgammaRIIIb) in human neutrophils. Biochim Biophys Acta 1833, 680–5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Romee R, Foley B, Lenvik T, Wang Y, Zhang B, Ankarlo D, Luo X, Cooley S, Verneris M, Walcheck B, Miller J. (2013) NK cell CD16 surface expression and function is regulated by a disintegrin and metalloprotease-17 (ADAM17). Blood 121, 3599–608. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Peruzzi G, Femnou L, Gil-Krzewska A, Borrego F, Weck J, Krzewski K, Coligan JE. (2013) Membrane-type 6 matrix metalloproteinase regulates the activation-induced downmodulation of CD16 in human primary NK cells. J Immunol 191, 1883–94. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Lajoie L, Congy-Jolivet N, Bolzec A, Gouilleux-Gruart V, Sicard E, Sung HC, Peiretti F, Moreau T, Vie H, Clemenceau B, Thibault G. (2014) ADAM17-mediated shedding of FcgammaRIIIA on human NK cells: identification of the cleavage site and relationship with activation. J Immunol 192, 741–51. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Trinchieri G, O’Brien T, Shade M, Perussia B. (1984) Phorbol esters enhance spontaneous cytotoxicity of human lymphocytes, abrogate Fc receptor expression, and inhibit antibody-dependent lymphocyte-mediated cytotoxicity. J Immunol 133, 1869–77. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Lanier LL, Phillips JH, Testi R. (1989) Membrane anchoring and spontaneous release of CD16 (FcR III) by natural killer cells and granulocytes. Eur J Immunol 19, 775–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Ravetch JV and Perussia B. (1989) Alternative membrane forms of Fc gamma RIII(CD16) on human natural killer cells and neutrophils. Cell type-specific expression of two genes that differ in single nucleotide substitutions. J Exp Med 170, 481–497. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Jing Y, Ni Z, Wu J, Higgins L, Markowski TW, Kaufman DS, Walcheck B. (2015) Identification of an ADAM17 cleavage region in human CD16 (FcgammaRIII) and the engineering of a non-cleavable version of the receptor in NK cells. PLoS One 10, e0121788. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Grzywacz B, Kataria N, Verneris MR. (2007) CD56(dim)CD16(+) NK cells downregulate CD16 following target cell induced activation of matrix metalloproteinases. Leukemia 21, 356–9; author reply 359. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Liu Q, Sun Y, Rihn S, Nolting A, Tsoukas PN, Jost S, Cohen K, Walker B, Alter G. (2009) Matrix metalloprotease inhibitors restore impaired NK cell-mediated antibody-dependent cellular cytotoxicity in human immunodeficiency virus type 1 infection. J Virol 83, 8705–12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Mishra HK, Pore N, Michelotti EF, Walcheck B. (2018) Anti-ADAM17 monoclonal antibody MEDI3622 increases IFNgamma production by human NK cells in the presence of antibody-bound tumor cells. Cancer Immunol Immunother 67, 1407–1416. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Tsukerman P, Eisenstein EM, Chavkin M, Schmiedel D, Wong E, Werner M, Yaacov B, Averbuch D, Molho-Pessach V, Stepensky P, Kaynan N, Bar-On Y, Seidel E, Yamin R, Sagi I, Elpeleg O, Mandelboim O. (2015) Cytokine secretion and NK cell activity in human ADAM17 deficiency. Oncotarget 6, 44151–60. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Selvaraj P, Rosse WF, Silber R, Springer TA. (1988) The major Fc receptor in blood has a phosphatidylinositol anchor and is deficient in paroxysmal noctural hemoglobinuria. Nature 333, 565–567. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Huizinga TW, Kerst M, Nuyens JH, Vlug A, von dem Borne AE, Roos D, Tetteroo PA. (1989) Binding characteristics of dimeric IgG subclass complexes to human neutrophils. J Immunol 142, 2359–64. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Tosi MF and Zakem H. (1992) Surface expression of Fc gamma receptor III (CD16) on chemoattractant-stimulated neutrophils is determined by both surface shedding and translocation from intracellular storage compartments. J Clin Invest 90, 462–470. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Huizinga TW, de Haas M, Kleijer M, Nuijens JH, Roos D, von dem Borne AE. (1990) Soluble Fc gamma receptor III in human plasma originates from release by neutrophils. J Clin Invest 86, 416–423. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Dransfield I, Buckle AM, Savill JS, McDowall A, Haslett C, Hogg N. (1994) Neutrophil apoptosis is associated with a reduction in CD16 (Fc gamma RIII) expression. Journal of Immunology 153, 1254–1263. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Middelhoven PJ, van Buul JD, Hordijk PL, Roos D. (2001) Different proteolytic mechanisms involved in Fc gamma RIIIb shedding from human neutrophils. Clinical and experimental immunology 125, 169–175. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Bazil V and Strominger JL. (1994) Metalloprotease and serine protease are involved in cleavage of CD43, CD44, and CD16 from stimulated human granulocytes. Induction of cleavage of L-selectin via CD16. J Immunol 152, 1314–22. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Moldovan I, Galon J, Maridonneau-Parini I, Roman-Roman S, Mathiot C, Fridman WH, Sautes-Fridman C. (1999) Regulation of production of soluble Fc gamma receptors type III in normal and pathological conditions. Immunology Letters 68, 125–134. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Teillaud C, Galon J, Zilber MT, Mazieres N, Spagnoli R, Kurrle R, Fridman WH, Sautes C. (1993) Soluble CD16 binds peripheral blood mononuclear cells and inhibits pokeweed-mitogen-induced responses. Blood 82, 3081–90. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Giebeler N and Zigrino P. (2016) A Disintegrin and Metalloprotease (ADAM): Historical Overview of Their Functions. Toxins (Basel) 8, 122. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Takeda S. (2016) ADAM and ADAMTS Family Proteins and Snake Venom Metalloproteinases: A Structural Overview. Toxins (Basel) 8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Mishra HK, Ma J, Walcheck B. (2017) Ectodomain Shedding by ADAM17: Its Role in Neutrophil Recruitment and the Impairment of This Process during Sepsis. Front Cell Infect Microbiol 7, 138. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Migaki GI, Kahn J, Kishimoto TK. (1995) Mutational analysis of the membrane-proximal cleavage site of L-selectin: relaxed sequence specificity surrounding the cleavage site. J Exp Med 182, 549–57. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Mezyk R, Bzowska M, Bereta J. (2003) Structure and functions of tumor necrosis factor-alpha converting enzyme. Acta biochimica Polonica 50, 625–45. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Stawikowska R, Cudic M, Giulianotti M, Houghten RA, Fields GB, Minond D. (2013) Activity of ADAM17 (a disintegrin and metalloprotease 17) is regulated by its noncatalytic domains and secondary structure of its substrates. J Biol Chem 288, 22871–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Fan H and Derynck R. (1999) Ectodomain shedding of TGF-alpha and other transmembrane proteins is induced by receptor tyrosine kinase activation and MAP kinase signaling cascades. EMBO J 18, 6962–72. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Rizoli SB, Rotstein OD, Kapus A. (1999) Cell volume-dependent regulation of L-selectin shedding in neutrophils. A role for p38 mitogen-activated protein kinase. J Biol Chem 274, 22072–80. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Alexander SR, Kishimoto TK, Walcheck B. (2000) Effects of selective protein kinase C inhibitors on the proteolytic down-regulation of L-selectin from chemoattractant-activated neutrophils. J Leukoc Biol 67, 415–22. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Wang Y, Robertson JD, Walcheck B. (2011) Different signaling pathways stimulate a disintegrin and metalloprotease-17 (ADAM17) in neutrophils during apoptosis and activation. J Biol Chem 286, 38980–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Lambrecht BN, Vanderkerken M, Hammad H. (2018) The emerging role of ADAM metalloproteinases in immunity. Nature reviews. Immunology. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 44.Bruhns P, Iannascoli B, England P, Mancardi DA, Fernandez N, Jorieux S, Daeron M. (2009) Specificity and affinity of human Fcgamma receptors and their polymorphic variants for human IgG subclasses. Blood 113, 3716–25. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Srpan K, Ambrose A, Karampatzakis A, Saeed M, Cartwright ANR, Guldevall K, De Matos G, Onfelt B, Davis DM. (2018) Shedding of CD16 disassembles the NK cell immune synapse and boosts serial engagement of target cells. J Cell Biol 217, 3267–3283. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Wedepohl S, Beceren-Braun F, Riese S, Buscher K, Enders S, Bernhard G, Kilian K, Blanchard V, Dernedde J, Tauber R. (2012) L-selectin--a dynamic regulator of leukocyte migration. European journal of cell biology 91, 257–64. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Ivetic A. (2018) A head-to-tail view of L-selectin and its impact on neutrophil behaviour. Cell Tissue Res 371, 437–453. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Li Y, Brazzell J, Herrera A, Walcheck B. (2006) ADAM17 deficiency by mature neutrophils has differential effects on L-selectin shedding. Blood 108, 2275–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Walcheck B, Kahn J, Fisher JM, Wang BB, Fisk RS, Payan DG, Feehan C, Betageri R, Darlak K, Spatola AF, Kishimoto TK. (1996) Neutrophil rolling altered by inhibition of L-selectin shedding in vitro. Nature 380, 720–3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Hafezi-Moghadam A, Thomas KL, Prorock AJ, Huo Y, Ley K. (2001) L-selectin shedding regulates leukocyte recruitment. J Exp Med 193, 863–72. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Long C, Hosseinkhani MR, Wang Y, Sriramarao P, Walcheck B. (2012) ADAM17 activation in circulating neutrophils following bacterial challenge impairs their recruitment. J Leukoc Biol 92, 667–72. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Bryceson YT, March ME, Ljunggren HG, Long EO. (2006) Synergy among receptors on resting NK cells for the activation of natural cytotoxicity and cytokine secretion. Blood 107, 159–66. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Bryceson YT, Ljunggren HG, Long EO. (2009) Minimal requirement for induction of natural cytotoxicity and intersection of activation signals by inhibitory receptors. Blood 114, 2657–66. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Chan WK, Kung Sutherland M, Li Y, Zalevsky J, Schell S, Leung W. (2012) Antibody-dependent cell-mediated cytotoxicity overcomes NK cell resistance in MLL-rearranged leukemia expressing inhibitory KIR ligands but not activating ligands. Clinical cancer research : an official journal of the American Association for Cancer Research 18, 6296–305. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Zhou Q, Gil-Krzewska A, Peruzzi G, Borrego F. (2013) Matrix metalloproteinases inhibition promotes the polyfunctionality of human natural killer cells in therapeutic antibody-based anti-tumour immunotherapy. Clin Exp Immunol 173, 131–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Pomeroy EJ, Hunzeker JT, Kluesner MT, Crosby MR, Lahr WS, Bendzick L, Miller JS, Webber BR, Geller MA, Walcheck B, Felices M, Starr TK, Moriarity BS. (2018) A Genetically Engineered Primary Human Natural Killer Cell Platform for Cancer Immunotherapy. BioRxiv 430553 [Preprint]. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 57.Hsu HT, Mace EM, Carisey AF, Viswanath DI, Christakou AE, Wiklund M, Onfelt B, Orange JS. (2016) NK cells converge lytic granules to promote cytotoxicity and prevent bystander killing. J Cell Biol 215, 875–889. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Gwalani LA and Orange JS. (2018) Single Degranulations in NK Cells Can Mediate Target Cell Killing. J Immunol 200, 3231–3243. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Lai P, Rabinowich H, Crowley-Nowick PA, Bell MC, Mantovani G, Whiteside TL. (1996) Alterations in expression and function of signal-transducing proteins in tumor-associated T and natural killer cells in patients with ovarian carcinoma. Clinical cancer research : an official journal of the American Association for Cancer Research 2, 161–73. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Felices M, Chu S, Kodal B, Bendzick L, Ryan C, Lenvik AJ, Boylan KLM, Wong HC, Skubitz APN, Miller JS, Geller MA. (2017) IL-15 super-agonist (ALT-803) enhances natural killer (NK) cell function against ovarian cancer. Gynecologic oncology 145, 453–461. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Veeramani S, Wang SY, Dahle C, Blackwell S, Jacobus L, Knutson T, Button A, Link BK, Weiner GJ. (2011) Rituximab infusion induces NK activation in lymphoma patients with the high-affinity CD16 polymorphism. Blood 118, 3347–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Cox MC, Battella S, La Scaleia R, Pelliccia S, Di Napoli A, Porzia A, Cecere F, Alma E, Zingoni A, Mainiero F, Ruco L, Monarca B, Santoni A, Palmieri G. (2015) Tumor-associated and immunochemotherapy-dependent long-term alterations of the peripheral blood NK cell compartment in DLBCL patients. Oncoimmunology 4, e990773. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Granzin M, Soltenborn S, Muller S, Kollet J, Berg M, Cerwenka A, Childs RW, Huppert V. (2015) Fully automated expansion and activation of clinical-grade natural killer cells for adoptive immunotherapy. Cytotherapy 17, 621–32. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Cooper MA, Fehniger TA, Caligiuri MA. (2001) The biology of human natural killer-cell subsets. Trends Immunol 22, 633–40. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Hatjiharissi E, Xu L, Santos DD, Hunter ZR, Ciccarelli BT, Verselis S, Modica M, Cao Y, Manning RJ, Leleu X, Dimmock EA, Kortsaris A, Mitsiades C, Anderson KC, Fox EA, Treon SP. (2007) Increased natural killer cell expression of CD16, augmented binding and ADCC activity to rituximab among individuals expressing the Fc{gamma}RIIIa-158 V/V and V/F polymorphism. Blood 110, 2561–2564. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Mandelboim O, Malik P, Davis DM, Jo CH, Boyson JE, Strominger JL. (1999) Human CD16 as a lysis receptor mediating direct natural killer cell cytotoxicity. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 96, 5640–4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Grier JT, Forbes LR, Monaco-Shawver L, Oshinsky J, Atkinson TP, Moody C, Pandey R, Campbell KS, Orange JS. (2012) Human immunodeficiency-causing mutation defines CD16 in spontaneous NK cell cytotoxicity. J Clin Invest 122, 3769–80. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Spear P, Wu MR, Sentman ML, Sentman CL. (2013) NKG2D ligands as therapeutic targets. Cancer immunity 13, 8. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Waldhauer I, Goehlsdorf D, Gieseke F, Weinschenk T, Wittenbrink M, Ludwig A, Stevanovic S, Rammensee HG, Steinle A. (2008) Tumor-associated MICA is shed by ADAM proteases. Cancer Res 68, 6368–76. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Boutet P, Aguera-Gonzalez S, Atkinson S, Pennington CJ, Edwards DR, Murphy G, Reyburn HT, Vales-Gomez M. (2009) Cutting edge: the metalloproteinase ADAM17/TNF-alpha-converting enzyme regulates proteolytic shedding of the MHC class I-related chain B protein. J Immunol 182, 49–53. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Chitadze G, Lettau M, Bhat J, Wesch D, Steinle A, Furst D, Mytilineos J, Kalthoff H, Janssen O, Oberg HH, Kabelitz D. (2013) Shedding of endogenous MHC class I-related chain molecules A and B from different human tumor entities: heterogeneous involvement of the “a disintegrin and metalloproteases” 10 and 17. International journal of cancer. Journal international du cancer 133, 1557–66. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Fabre-Lafay S, Garrido-Urbani S, Reymond N, Goncalves A, Dubreuil P, Lopez M. (2005) Nectin-4, a new serological breast cancer marker, is a substrate for tumor necrosis factor-alpha-converting enzyme (TACE)/ADAM-17. J Biol Chem 280, 19543–50. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Shen H, Li L, Zhou S, Yu D, Yang S, Chen X, Wang D, Zhong S, Zhao J, Tang J. (2016) The role of ADAM17 in tumorigenesis and progression of breast cancer. Tumour Biol [DOI] [PubMed]

- 74.Mustafi R, Dougherty U, Mustafi D, Ayaloglu-Butun F, Fletcher M, Adhikari S, Sadiq F, Meckel K, Haider HI, Khalil A, Pekow J, Konda V, Joseph L, Hart J, Fichera A, Li YC, Bissonnette M. (2017) ADAM17 is a Tumor Promoter and Therapeutic Target in Western Diet-associated Colon Cancer. Clinical cancer research : an official journal of the American Association for Cancer Research 23, 549–561. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Buchanan PC, Boylan KLM, Walcheck B, Heinze R, Geller MA, Argenta PA, Skubitz APN. (2017) Ectodomain shedding of the cell adhesion molecule Nectin-4 in ovarian cancer is mediated by ADAM10 and ADAM17. J Biol Chem 292, 6339–6351. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Moss ML and Minond D. (2017) Recent Advances in ADAM17 Research: A Promising Target for Cancer and Inflammation. Mediators Inflamm 2017, 9673537. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Duffy MJ, Mullooly M, O’Donovan N, Sukor S, Crown J, Pierce A, McGowan PM. (2011) The ADAMs family of proteases: new biomarkers and therapeutic targets for cancer? Clinical proteomics 8, 9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Tape CJ, Willems SH, Dombernowsky SL, Stanley PL, Fogarasi M, Ouwehand W, McCafferty J, Murphy G. (2011) Cross-domain inhibition of TACE ectodomain. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 108, 5578–83. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Richards FM, Tape CJ, Jodrell DI, Murphy G. (2012) Anti-tumour effects of a specific anti-ADAM17 antibody in an ovarian cancer model in vivo. PLoS One 7, e40597. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Kwok HF, Botkjaer KA, Tape CJ, Huang Y, McCafferty J, Murphy G. (2014) Development of a ‘mouse and human cross-reactive’ affinity-matured exosite inhibitory human antibody specific to TACE (ADAM17) for cancer immunotherapy. Protein engineering, design & selection : PEDS 27, 179–90. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Caiazza F, McGowan PM, Mullooly M, Murray A, Synnott N, O’Donovan N, Flanagan L, Tape CJ, Murphy G, Crown J, Duffy MJ. (2015) Targeting ADAM-17 with an inhibitory monoclonal antibody has antitumour effects in triple-negative breast cancer cells. Br J Cancer 112, 1895–903. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Rios-Doria J, Sabol D, Chesebrough J, Stewart D, Xu L, Tammali R, Cheng L, Du Q, Schifferli K, Rothstein R, Leow CC, Heidbrink-Thompson J, Jin X, Gao C, Friedman J, Wilkinson B, Damschroder M, Pierce AJ, Hollingsworth RE, Tice DA, Michelotti EF. (2015) A Monoclonal Antibody to ADAM17 Inhibits Tumor Growth by Inhibiting EGFR and Non-EGFR-Mediated Pathways. Mol Cancer Ther 14, 1637–49. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Dosch J, Ziemke E, Wan S, Luker K, Welling T, Hardiman K, Fearon E, Thomas S, Flynn M, Rios-Doria J, Hollingsworth R, Herbst R, Hurt E, Sebolt-Leopold J. (2017) Targeting ADAM17 inhibits human colorectal adenocarcinoma progression and tumor-initiating cell frequency. Oncotarget 8, 65090–65099. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Peng L, Cook K, Xu L, Cheng L, Damschroder M, Gao C, Wu H, Dall’Acqua WF. (2016) Molecular basis for the mechanism of action of an anti-TACE antibody. MAbs 8, 1598–1605. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Ikeda H, Old LJ, Schreiber RD. (2002) The roles of IFN gamma in protection against tumor development and cancer immunoediting. Cytokine Growth Factor Rev 13, 95–109. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Schroder K, Hertzog PJ, Ravasi T, Hume DA. (2004) Interferon-gamma: an overview of signals, mechanisms and functions. J Leukoc Biol 75, 163–89. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Wang R, Jaw JJ, Stutzman NC, Zou Z, Sun PD. (2012) Natural killer cell-produced IFN-gamma and TNF-alpha induce target cell cytolysis through up-regulation of ICAM-1. J Leukoc Biol 91, 299–309. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Kammertoens T, Friese C, Arina A, Idel C, Briesemeister D, Rothe M, Ivanov A, Szymborska A, Patone G, Kunz S, Sommermeyer D, Engels B, Leisegang M, Textor A, Fehling HJ, Fruttiger M, Lohoff M, Herrmann A, Yu H, Weichselbaum R, Uckert W, Hubner N, Gerhardt H, Beule D, Schreiber H, Blankenstein T. (2017) Tumour ischaemia by interferon-gamma resembles physiological blood vessel regression. Nature 545, 98–102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Seidel UJ, Schlegel P, Lang P. (2013) Natural killer cell mediated antibody-dependent cellular cytotoxicity in tumor immunotherapy with therapeutic antibodies. Front Immunol 4, 76. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Blaydon DC, Biancheri P, Di WL, Plagnol V, Cabral RM, Brooke MA, van Heel DA, Ruschendorf F, Toynbee M, Walne A, O’Toole EA, Martin JE, Lindley K, Vulliamy T, Abrams DJ, MacDonald TT, Harper JI, Kelsell DP. (2011) Inflammatory skin and bowel disease linked to ADAM17 deletion. N Engl J Med 365, 1502–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Chalaris A, Adam N, Sina C, Rosenstiel P, Lehmann-Koch J, Schirmacher P, Hartmann D, Cichy J, Gavrilova O, Schreiber S, Jostock T, Matthews V, Hasler R, Becker C, Neurath MF, Reiss K, Saftig P, Scheller J, Rose-John S. (2010) Critical role of the disintegrin metalloprotease ADAM17 for intestinal inflammation and regeneration in mice. J Exp Med 207, 1617–24. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.Zeng J, Tang SY, Toh LL, Wang S. (2017) Generation of “Off-the-Shelf” Natural Killer Cells from Peripheral Blood Cell-Derived Induced Pluripotent Stem Cells. Stem Cell Reports 9, 1796–1812. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93.Zhang C, Oberoi P, Oelsner S, Waldmann A, Lindner A, Tonn T, Wels WS. (2017) Chimeric Antigen Receptor-Engineered NK-92 Cells: An Off-the-Shelf Cellular Therapeutic for Targeted Elimination of Cancer Cells and Induction of Protective Antitumor Immunity. Front Immunol 8, 533. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94.Mehta RS and Rezvani K. (2018) Chimeric Antigen Receptor Expressing Natural Killer Cells for the Immunotherapy of Cancer. Front Immunol 9, 283. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]