Abstract

Background

Stage IV gastric signet ring cell carcinoma (SRCC) is a type of malignant gastric cancer (GC) with poorer survival compared to metastatic non‐SRCC gastric cancer (NOS). However, chemotherapy alone was unable to maintain long‐term survival. This study aimed to evaluate survival benefit of palliative gastrectomy plus chemotherapy (PG+C) for metastatic gastric SRCC.

Methods

We obtained data on gastric cancer patients between 2010 and 2015 from the Surveillance, Epidemiology, and End Results (SEER) database. Statistical methods included χ 2 tests, Kaplan‐Meier curves, COX models, propensity score matching (PSM) and subgroup analysis.

Results

Among 27 240 gastric cancer patients included, 4638 (17.03%) were SRCC patients. The proportion of patients with younger age, female gender, poorly differentiated grade and M1 stage was higher in SRCC than in NOS (P < .001). Multivariate analysis revealed that multiple metastatic sites (HR = 1.39, 95% CI: 1.14‐1.69, P = .001) was associated with increased mortality risk in metastatic SRCC. Median survival time was improved in metastatic SRCC receiving PG+C compared to PG/C alone (13 vs 7 months, P < .001). Notably, in subgroup analysis, 13 of 17 groups of metastatic SRCC patients with PG+C had prolonged overall survival compared to chemotherapy alone, especially for those with only one metastatic site (HR = 0.61, 95% CI: 0.51‐0.73, P < .001).

Conclusions

Our results suggested that there exists at least a selective group of stage IV gastric SRCC patients, who could benefit from palliative gastrectomy followed by chemotherapy compared to chemotherapy alone. Further prospective trials are needed to support our conclusion.

Keywords: chemotherapy, gastric signet ring cell carcinoma, palliative gastrectomy, SEER database, stage IV gastric cancer

Stage IV gastric signet ring cell carcinoma (SRCC) is a type of malignant gastric cancer with higher metastasis rate and poorer overall survival compared to non‐SRCC gastric cancer (NOS). There exists at least a selective group of stage IV gastric SRCC patients, who could benefit from palliative gastrectomy followed by chemotherapy compared to chemotherapy alone.

![]()

1. INTRODUCTION

Gastric cancer is one of the most common malignant tumors of the digestive tract, and currently accounts for 8.2% of all new cancer cases worldwide.1 Adenocarcinomas represent the majority of gastric cancers, while signet ring cell carcinoma (SRCC) is a poorly differentiated subtype of gastric carcinoma with unique clinical characteristics and poor survival rates.2, 3, 4 Previous studies indicated that gastric SRCC has different risk factors compared to non‐SRCC gastric cancer (NOS) types, including older age, female gender, smoking, obesity and American Joint Committee on Cancer (AJCC) IV stage.5, 6, 7 Pathologically, gastric SRCC consists of scattered malignant cells containing abundant intracytoplasmic mucin, and is associated with rapid growth and diffuse infiltration of surrounding tissues.6, 8 Also, previous studies reported that SRCC was not cohesive and prone to invasion of the submucosal and subserosal layers, which also allowed for the increased incidence and poor survival of metastatic SRCC.9, 10, 11

Palliative systemic therapy (mostly chemotherapy) was recommended as standard management for stage IV gastric SRCC.12 A multicenter study reported that triplet chemotherapy with docetaxel‐5FU‐oxaliplatin appeared to be effective as first‐line treatment for patients with metastatic or locally advanced non‐resectable gastric SRCC.13 However, the role of palliative gastrectomy in stage IV gastric cancer is still controversial. Previous retrospective studies and clinical trials showed that palliative gastrectomy was associated with improved overall survival for metastatic gastric cancer patients.14, 15, 16 Conversely, one phase 3, randomized controlled trial (REGATTA trial) showed that gastrectomy followed by chemotherapy failed to have any survival benefit compared with chemotherapy alone in advanced gastric cancer.17 Thus, the appropriate justification for the role of palliative gastrectomy is still needed. Notably, up till now, there is no such analysis focusing on the treatment effect of palliative gastrectomy on stage IV gastric SRCC patients. Considering the higher metastatic rate and the poorer overall survival of gastric SRCC compared to NOS, it is of great necessity to assess the role of palliative gastrectomy followed by adjuvant chemotherapy for stage IV gastric SRCC patients.

Therefore, in this study, the primary aim was to assess the therapeutic effects of palliative gastrectomy and chemotherapy on the survival of stage IV gastric SRCC patients based on a large Western population. We also identified significant clinicopathological characteristics and independent prognosis factors of these patients.

2. MATERIALS AND METHODS

2.1. Data source

Cases of gastric cancer were identified from the Surveillance, Epidemiology, and End Results (SEER) database. The SEER database is an openly accessed database with information on cancer incidence and survival from 18 population‐based cancer registries, representing approximately 28% of the United States population (http://seer.cancer.gov/ about/overview.html).18 SEER is supported by the Surveillance Research Program (SRP) in National Cancer Institute's Division of Cancer Control and Population Sciences (DCCPS). We used the SEER database version available on April 2019 (Noember 2018 Submission). The methods we employed were consistent with the criteria of the SEER database. All TNM classification was restaged according to the criteria described in the American Joint Committee on Cancer (AJCC) Cancer Staging Manual, 8th edition, 2017 (Stages I, II, III, and IV).

2.2. Patient selection

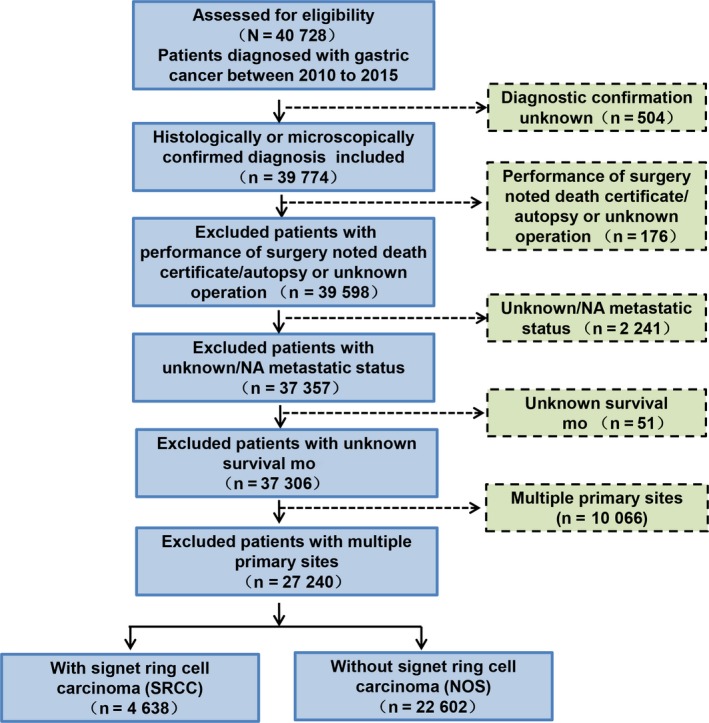

Patient data of gastric cancer, including gastric SRCC from 2010 to 2015 were obtained from the SEER database according to the International Classification of Diseases for Oncology (Third Edition, ICD‐O‐3, SRCC identified as 8490). Patient selection criteria were as follows: (a) confirmation of gastric cancer diagnosis histologically or microscopically; (b) exclusion of patients who had unknown surgeries; (c) exclusion of patients with unknown or absent metastatic status; (d) exclusion of patients with unknown survival months; (e) exclusion of patients with multiple primary tumor sites. As a result, 27 240 patients were assessed for eligibility, including 4638 gastric SRCC patients and 22 602 NOS patients (Figure 1). In subgroup analysis, patients with distant metastasis were identified as AJCC stage IV (M1 stage at diagnosis). Patient clinical variables included age at diagnosis, gender, race, year of diagnosis, tumor grade, AJCC stage, TNM stage at diagnosis, tumor size, tumor location, regional nodes examined, and therapies employed (surgery, chemotherapy, and radiotherapy).

Figure 1.

Flow chart of inclusion and exclusion process of the Surveillance, Epidemiology and End Results (SEER) patient dataset

2.3. Statistical analysis

The R version 3.5.0 (http://www.R-project.org/) was employed for all statistical analysis. Chi‐square tests (χ 2 test) were used to compare clinicopathological characteristics between gastric SRCC and NOS patients. The overall survival (OS) was the primary endpoint outcome defined from the date of operation to the date of death or the latest follow‐up. The 5‐year OS rates were the ratio of patients alive after five years from the operation date among all patients included. Kaplan‐Meier curves and log‐rank tests were used to draw overall survival curves within different patient subgroups. Also, to analyze the prognostic factors of stage IV gastric SRCC and NOS patients, we employed univariate and multivariate Cox regression models to estimate HR (hazard ratio) and exact 95% CIs (confidence intervals). Propensity score matching (PSM) was used to adjust numerical differences between gastric SRCC and NOS patients. The forest plot was used to compare the impact of palliative gastrectomy followed by chemotherapy versus palliative gastrectomy or chemotherapy alone among different metastatic gastric SRCC subgroups. All statistical tests were performed two‐sided and P values <.05 were considered to be statistically significant.

3. RESULTS

3.1. Patient characteristics and overall survival of gastric NOS and SRCC

Data from a total of 27 240 eligible gastric cancer patients diagnosed between 2010 and 2015 were obtained from the SEER database. Among these, 4638 were gastric SRCC patients (17.03%) and 22 602 were NOS patients (82.97%, Table 1). In this cohort, 2701 SRCC patients (58.24%) were younger than 65 years while 9669 NOS patients (42.78%) were younger than 65, indicating that patients diagnosed with SRCC present a younger age compared with other types of gastric cancer (P < .001). Regarding gender, more female patients were diagnosed with SRCC (47.26%) compared with NOS patients (37%) (P < .001). Additionally, compared with NOS patients, patients with SRCC are more likely to have a poorly differentiated tumor grade (77.19% vs 43.01%, P < .001), III/IV AJCC stage (21.07% vs 17.58% in III, 43.31% vs 34.08% in Ⅳ, P < .001) and T4 stage (25.61% vs 16.82%, P < .001), which were in accordance with the pathological features of gastric signet ring cell carcinoma reported previously.2 Importantly, more SRCC patients were in M1 stage than NOS patients (42.93% vs 33.76%, P < .001). With regards to treatment, the proportion of surgery or radiotherapy received was similar between SRCC and NOS patients (41.29% vs 47.82% in surgery, P < .001; 14.6% vs 13.19% in radiotherapy, P = .011), However, more SRCC patients chose to receive chemotherapy compared with NOS patients (60.69% vs 49.78%, P < .001). Additional cohort information is shown in Table 1. In order to eliminate the impact from the difference in the number of SRCC and NOS patients, we also conducted propensity score matching (PSM) to analyze and adjust patient characteristics for gender, race, and age (Table 1). Clinicopathological results between SRCC and NOS patients were essentially the same following PSM. We also analyzed patient characteristics of stage IV gastric SRCC and NOS in Table S1 and the clinicopathological differences were basically very similar with results in Table 1.

Table 1.

Clinicopathological Characteristics of gastric NOS and SRCC Patients

| Variable |

NOS n = 22 602 (%) |

SRCC n = 4638 (%) |

P |

NOS PSM n = 4638 (%) |

SRCC PSM n = 4638 (%) |

P |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age (y) | ||||||

| <65 | 9669 (42.78) | 2701 (58.24) | 2701 (58.24) | 2701 (58.24) | ||

| ≥65 | 12 933 (57.22) | 1937 (41.76) | <.001 | 1937 (41.76) | 1937 (41.76) | 1 |

| Gender | ||||||

| Male | 14 239 (63) | 2446 (52.74) | 2446 (52.74) | 2446 (52.74) | ||

| Female | 8363 (37) | 2192 (47.26) | <.001 | 2192 (47.26) | 2192 (47.26) | 1 |

| Race | ||||||

| White | 15 820 (69.99) | 3254 (70.16) | 3254 (70.16) | 3254 (70.16) | ||

| Black | 3270 (14.47) | 571 (12.31) | 571 (12.31) | 571 (12.31) | ||

| Other | 3512 (15.54) | 813 (17.53) | <.001 | 813 (17.53) | 813 (17.53) | 1 |

| Year | ||||||

| 2010 | 3572 (15.8) | 731 (15.76) | 773 (16.67) | 731 (15.76) | ||

| 2011 | 3548 (15.7) | 740 (15.96) | 714 (15.39) | 740 (15.96) | ||

| 2012 | 3780 (16.72) | 802 (17.29) | 774 (16.69) | 802 (17.29) | ||

| 2013 | 3845 (17.01) | 746 (16.08) | 802 (17.29) | 746 (16.08) | ||

| 2014 | 3969 (17.56) | 823 (17.74) | 797 (17.18) | 823 (17.74) | ||

| 2015 | 3888 (17.2) | 796 (17.16) | .708 | 778 (16.77) | 796 (17.16) | .443 |

| Tumor grade | ||||||

| Well | 2045 (9.05) | 6 (0.13) | 476 (10.26) | 6 (0.13) | ||

| Moderately | 5544 (24.53) | 86 (1.85) | 1070 (23.07) | 86 (1.85) | ||

| Poorly | 9722 (43.01) | 3580 (77.19) | 2008 (43.29) | 3580 (77.19) | ||

| Undifferentiated | 470 (2.08) | 91 (1.96) | 104 (2.24) | 91 (1.96) | ||

| Unknown | 4821 (21.33) | 875 (18.87) | <.001 | 980 (21.13) | 875 (18.87) | <.001 |

| Tumor location | ||||||

| Upper stomach | 8648 (38.26) | 967 (20.85) | 1694 (36.52) | 967 (20.85) | ||

| Middle stomach | 4822 (21.33) | 1215 (26.2) | 1009 (21.76) | 1215 (26.2) | ||

| Lower stomach | 4303 (19.04) | 1089 (23.48) | 950 (20.48) | 1089 (23.48) | ||

| Overlapping | 1507 (6.67) | 530 (11.43) | 287 (6.19) | 530 (11.43) | ||

| Stomach NOS | 3322 (14.7) | 837 (18.05) | <.001 | 698 (15.05) | 837 (18.05) | <.001 |

| AJCC | ||||||

| 0,I,II | 8502 (34.55) | 1341 (26.7) | 1720 (34.25) | 1341 (26.7) | ||

| III | 4327 (17.58) | 1058 (21.07) | 847 (16.87) | 1058 (21.07) | ||

| IV | 8386 (34.08) | 2175 (43.31) | 1775 (35.34) | 2175 (43.31) | ||

| Unknown | 3393 (13.79) | 448 (8.92) | <.001 | 680 (13.54) | 448 (8.92) | <.001 |

| T‐stage | ||||||

| Tis,T1,T2 | 8293 (36.69) | 1375 (29.65) | 2454 (52.91) | 2102 (45.32) | ||

| T3 | 5502 (24.34) | 1049 (22.62) | 1505 (32.45) | 1504 (32.43) | ||

| T4 | 3801 (16.82) | 1188 (25.61) | 316 (6.81) | 626 (13.5) | ||

| Unknown | 5006 (22.15) | 1026 (22.12) | <.001 | 363 (7.83) | 406 (8.75) | <.001 |

| N‐stage | ||||||

| N0 | 11 699 (51.76) | 2102 (45.32) | 2454 (52.91) | 2102 (45.32) | ||

| N1,N2 | 7470 (33.05) | 1504 (32.43) | 1505 (32.45) | 1504 (32.43) | ||

| N3 | 1613 (7.14) | 626 (13.5) | 316 (6.81) | 626 (13.5) | ||

| Unknown | 1820 (8.05) | 406 (8.75) | <.001 | 363 (7.83) | 406 (8.75) | <.001 |

| M‐stage | ||||||

| M0 | 14 971 (66.24) | 2647 (57.07) | 2999 (64.66) | 2647 (57.07) | ||

| M1 | 7631 (33.76) | 1991 (42.93) | <.001 | 1639 (35.34) | 1991 (42.93) | <.001 |

| Regional lymph nodes | ||||||

| None | 13 998 (61.93) | 2691 (58.02) | 2904 (62.61) | 2691 (58.02) | ||

| Negative | 3868 (17.11) | 670 (14.45) | 795 (17.14) | 670 (14.45) | ||

| Positive | 4425 (19.58) | 1233 (26.58) | 881 (19) | 1233 (26.58) | ||

| Unknown | 311 (1.38) | 44 (0.95) | <.001 | 58 (1.25) | 44 (0.95) | <.001 |

| Surgery | ||||||

| No | 11 794 (52.18) | 2723 (58.71) | 2389 (51.51) | 2723 (58.71) | ||

| Yes | 10 808 (47.82) | 1915 (41.29) | <.001 | 2249 (48.49) | 1915 (41.29) | <.001 |

| Radiotherapy | ||||||

| No | 19 620 (86.81) | 3961 (85.4) | 3990 (86.03) | 3961 (85.4) | ||

| Yes | 2982 (13.19) | 677 (14.6) | .011 | 648 (13.97) | 677 (14.6) | .406 |

| Chemotherapy | ||||||

| No/Unknown | 11 631 (51.46) | 1823 (39.31) | 2329 (50.22) | 1823 (39.31) | ||

| Yes | 10 971 (48.54) | 2815 (60.69) | <.001 | 2309 (49.78) | 2815 (60.69) | <.001 |

Abbreviations: NOS, non‐SRCC gastric cancer; PSM, propensity score matching; SRCC, gastric signet ring cell carcinoma.

Additionally, considering the high rate of metastasis in gastric SRCC patients (Table 1), we further analyzed the five‐year overall survival (OS) among gastric SRCC and NOS groups with or without distant metastasis. The survival results showed that SRCC type and distant metastasis were associated with poorer survival (Figure S1A, P < .001). M1 stage SRCC patients had the worst survival, whose 3‐year OS was 1.76% compared to 4.38% (M1 NOS), 22.18% (M0 SRCC) and 30.71% (M0 NOS). Survival outcome between these subgroups was essentially the same after PSM (Figure S1B).

3.2. Patient characteristics of stage IV gastric SRCC with different treatment

Considering the higher metastatic rate and poorer survival of stage IV gastric SRCC compared with NOS, we made further analysis on these patients with different treatments including palliative gastrectomy plus chemotherapy (PG+C), palliative gastrectomy or chemotherapy alone (PG/C) and no treatment (Table 2). T and N stage were not included in the analysis of stage IV patients due to the low accuracy of staging among patients who did not undergo surgery. The number of patients under age 65 was larger in PG+C (77.22%) and PG/C groups (74.01%) than no treatment group (51.31%) (P < .001). Also, the proportion of stage IV gastric SRCC patients with poorly differentiated grade or tumor at overlapping location was higher in PG+C (80%; 21.67%) and PG/C (74.1%; 14.03%) groups than in the no treatment group (62.87%; 9.86%) (P < .001). In addition, more patients with only one metastatic site received PG+C (95.56%) compared to patients with PG/C (82.53%) or no treatment (83.2%) (P < .001). Other clinicopathological differences among these three groups are also shown in Table 2.

Table 2.

Clinicopathological Characteristics of stage IV SRCC Patients with PG+C, PG/C or with no treatment

| Variable |

PG+C n = 180 (%) |

PG/C n = 1162 (%) |

No treatment n = 649 (%) |

P value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age (y) | ||||

| <65 | 139 (77.22) | 860 (74.01) | 333 (51.31) | |

| ≥65 | 41 (22.78) | 302 (25.99) | 316 (48.69) | <.001 |

| Gender | ||||

| Male | 82 (45.56) | 605 (52.07) | 350 (53.93) | |

| Female | 98 (54.44) | 557 (47.93) | 299 (46.07) | .138 |

| Race | ||||

| White | 138 (76.67) | 838 (72.12) | 464 (71.49) | |

| Black | 11 (6.11) | 139 (11.96) | 89 (13.71) | |

| Other | 31 (17.22) | 185 (15.92) | 96 (14.79) | .093 |

| Year | ||||

| 2010 | 42 (23.33) | 162 (13.94) | 104 (16.02) | |

| 2011 | 26 (14.44) | 170 (14.63) | 97 (14.95) | |

| 2012 | 34 (18.89) | 188 (16.18) | 102 (15.72) | |

| 2013 | 25 (13.89) | 183 (15.75) | 114 (17.57) | |

| 2014 | 30 (16.67) | 232 (19.97) | 112 (17.26) | |

| 2015 | 23 (12.78) | 227 (19.54) | 120 (18.49) | .065 |

| Tumor grade | ||||

| Well/ Moderately | 5 (2.78) | 15 (1.29) | 12 (1.85) | |

| Poorly | 144 (80) | 861 (74.1) | 408 (62.87) | |

| Undifferentiated | 6 (3.33) | 10 (0.86) | 11 (1.69) | |

| Unknown | 25 (13.89) | 276 (23.75) | 218 (33.59) | <.001 |

| Tumor location | ||||

| Upper stomach | 14 (7.78) | 246 (21.17) | 116 (17.87) | |

| Middle stomach | 51 (28.33) | 304 (26.16) | 151 (23.27) | |

| Lower stomach | 51 (28.33) | 190 (16.35) | 99 (15.25) | |

| Overlapping | 39 (21.67) | 163 (14.03) | 64 (9.86) | |

| Stomach NOS | 25 (13.89) | 259 (22.29) | 219 (33.74) | <.001 |

| Distant metastasis | ||||

| One site | 172 (95.56) | 959 (82.53) | 540 (83.2) | |

| Multiple sites | 8 (4.44) | 203 (17.47) | 109 (16.8) | <.001 |

| Surgery | ||||

| No | 0 (0.00) | 1092 (93.98) | 649 (100.00) | |

| Yes | 180 (100.00) | 70 (6.02) | 0 (0.00) | |

| Chemotherapy | ||||

| No/Unknown | 0 (0.00) | 70 (6.02) | 649 (100.00) | |

| Yes | 180 (100.00) | 1092 (93.98) | 0 (0.00) | |

3.3. Identifying prognosis factors for patients with stage IV gastric SRCC

To further explore the risk factors related to long‐term survival outcome of metastatic gastric SRCC, we employed univariate and multivariate Cox regression analyses to identify protective or adverse prognostic factors. T and N stage were not included in the analysis of stage IV patients due to the low accuracy of staging among these patients. As shown in Table 3, results of multivariate Cox regression suggested that among metastatic gastric SRCC patients, palliative gastrectomy (HR = 0.66, 95% CI: 0.51‐0.85, P < .001) and chemotherapy (HR = 0.28, 95% CI: 0.24‐0.32, P < .001) were considered as protective prognosis factors, while multiple metastatic sites (HR = 1.39, 95% CI: 1.14‐1.69, P = .001) was an adverse prognosis factor. Other independent prognosis factors of stage IV gastric SRCC identified in the univariate Cox regression are listed in Table 3.

Table 3.

Univariate and multivariate analyses for stage IV gastric SRCC Patients

| Variable | Univariable | Multivariable | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| HR | 95% CI | P value | HR | 95% CI | P value | |

| Age (y) | ||||||

| ≦65 | Ref | Ref | ||||

| >65 | 1.38 | 1.26‐1.52 | <.001 | 1.08 | 0.94‐1.23 | .285 |

| Gender | ||||||

| Male | Ref | |||||

| Female | 0.88 | 0.8‐0.96 | .006 | 0.95 | 0.84‐1.08 | .458 |

| Race | ||||||

| White | Ref | |||||

| Black | 1.11 | 0.96‐1.28 | .155 | |||

| Other | 0.96 | 0.84‐1.09 | .488 | |||

| Tumor grade | ||||||

| Well | Ref | |||||

| Moderately | 1.06 | 0.25‐4.44 | .938 | |||

| Poorly | 1 | 0.25‐4 | .998 | |||

| Undifferentiated | 1.1 | 0.26‐4.63 | .901 | |||

| Unknown | 1.06 | 0.25‐4.44 | .938 | |||

| Distant metastasis | ||||||

| One site | Ref | |||||

| Multiple sites | 1.38 | 1.22‐1.57 | 0 | 1.39 | 1.14‐1.69 | .001 |

| Primary tumor location | ||||||

| Upper stomach | Ref | Ref | ||||

| Middle stomach | 0.93 | 0.81‐1.07 | .294 | 1.08 | 0.9‐1.31 | .418 |

| Lower stomach | 0.98 | 0.84‐1.14 | .785 | 1.01 | 0.82‐1.23 | .958 |

| Overlapping | 0.96 | 0.82‐1.13 | .645 | 1.13 | 0.92‐1.39 | .249 |

| Stomach NOS | 1.28 | 1.12‐1.47 | 0 | 1.25 | 1.02‐1.53 | .029 |

| Palliative gastrectomy | ||||||

| No | Ref | Ref | ||||

| Yes | 0.53 | 0.46‐0.61 | <.001 | 0.66 | 0.51‐0.85 | 0 |

| Radiotherapy | ||||||

| No | Ref | Ref | ||||

| Yes | 0.56 | 0.42‐0.74 | <.001 | 1.08 | 0.76‐1.53 | .666 |

| Chemotherapy | ||||||

| No/Unknown | Ref | Ref | ||||

| Yes | 0.31 | 0.28‐0.34 | <.001 | 0.28 | 0.24‐0.32 | 0 |

Abbreviations: NOS, Non‐SRCC gastric cancer; SRCC, Gastric signet ring cell carcinoma.

3.4. Survival benefits of palliative gastrectomy plus chemotherapy for stage IV gastric SRCC

Given that assessing treatment effects for metastatic gastric SRCC patients was essential, we next focused on therapeutic benefits of overall survival for these patients. Treatment managements of metastatic gastric SRCC were divided into three groups (PG+C, n = 180; PG/C, n = 1162; no treatment, n = 649). Radiotherapy was not included in further analysis due to the small patient number (n = 55, P = .355, Table S1) and it was not found to be an independent prognosis factor in multivariate Cox regression (P = .589; Table 3). The findings were as follows.

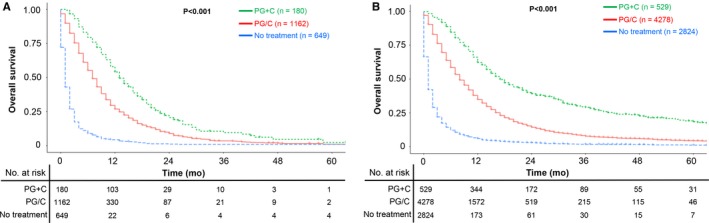

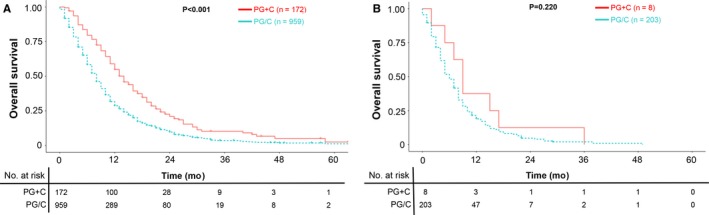

In Figure 2A, median survival time of metastatic SRCC patients receiving PG+C was 13 months (95% CI: 12‐16 months), while the PG/C group was 7 months (95% CI: 7‐8 months). Similar results could also be found among NOS groups in Figure 2B, with 17 months (95% CI: 16‐20 months) of median survival time in PG+C group and 8 months (95% CI: 8‐9 months) in PG/C group. These results indicated that both in metastatic gastric SRCC and NOS, palliative gastrectomy followed by chemotherapy could lead to prolonged overall survival compared to palliative gastrectomy or chemotherapy alone. Notably, when combining these results together, we found that metastatic SRCC receiving PG+C had better overall survival than metastatic NOS receiving PG/C alone (median survival time: 13 vs 8 months, P < .001, Figure S2). Moreover, with regards to the number of metastatic sites, PG+C lead to improved overall survival than PG/C among stage IV gastric SRCC patients with only one metastatic site (P < .001, Figure 3A), while these two groups had no statistical difference among patients with multiple metastatic sites (P = .220, Figure 3B).

Figure 2.

A, OS among stage IV gastric SRCC patients with PG+C, PG/C or with no treatment, P < .001; (B) OS among stage IV gastric NOS patients with PG+C, PG/C or with no treatment, P < .001; NOS: Non‐specific gastric cancer except SRCC; SRCC: Signet ring cell carcinoma; PG+C: Palliative gastrectomy followed by chemotherapy; PG/C: Palliative gastrectomy or chemotherapy alone

Figure 3.

A, OS of PG+C or PG/C among stage IV gastric SRCC patients with only one metastatic site, P < .001; (B) OS of PG + C or PG/C among stage IV gastric SRCC patients with multiple metastatic sites, P = .220. SRCC: Signet ring cell carcinoma; PG+C: Palliative gastrectomy followed by chemotherapy; PG/C: Palliative gastrectomy or chemotherapy alone

Considering the poorer prognosis of gastric SRCC compared with NOS, these findings emphasized the value of palliative gastrectomy plus chemotherapy in stage IV gastric SRCC treatment, especially those with only one metastatic site.

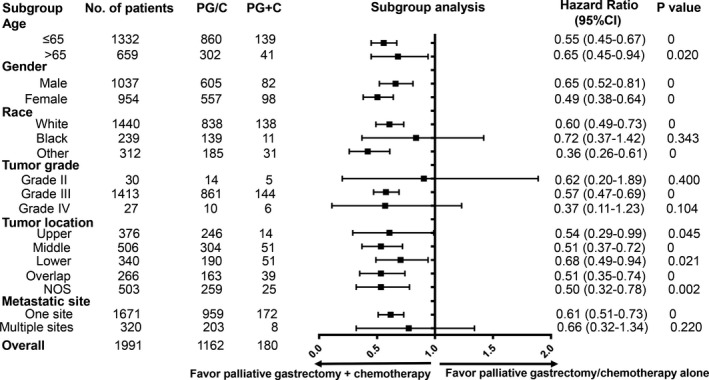

3.5. Subgroup analysis of stage IV gastric SRCC patients

After finding the prolonged survival of palliative gastrectomy plus chemotherapy compared to palliative gastrectomy or chemotherapy alone in metastatic gastric SRCC, we next aimed to analyze the prognostic consistency between these two treatment strategies. Metastatic SRCC patients were divided into subgroups based on the clinicopathological characteristics identified in Table 3. Cox's regression model was separately used to estimate HR and 95% CI in each subgroup (Figure 4). The results suggested that generally metastatic gastric SRCC patients who underwent PG+C could obtain much more survival benefits than patients who underwent PG/C alone (P < .05 arrived in 13 subgroups). Especially, metastatic SRCC patients with only one metastatic site benefited much from PG+C compared to PG/C alone (HR = 0.61, 95% CI: 0.51‐0.73, P = 0) while the survival benefit of PG+C was not statistically significant in patients with multiple metastatic sites (P = .220). Similar results are also presented in Figure 3. Therefore, it could be more meaningful to implement palliative gastrectomy plus chemotherapy in M1 gastric SRCC patients with only one distant metastatic site.

Figure 4.

Subgroup analysis of PG+C and PG/C among stage IV gastric SRCC patients. SRCC: Signet ring cell carcinoma; PG+C: Palliative gastrectomy followed by chemotherapy; PG/C: Palliative gastrectomy or chemotherapy alone. Grade II: Moderately differentiated grade, Grade III: Poorly differentiated grade, Grade IV: Undifferentiated grade

Taken together, results from subgroup analysis indicated that for metastatic gastric SRCC, there existed as least a selective subgroup of patients, who could obtain survival benefit from palliative gastrectomy plus chemotherapy.

4. DISCUSSION

In this study, we analyzed data from 27 240 gastric cancer patients, including 4638 gastric SRCC patients, from the SEER database. To the best of our knowledge, this is the first large population‐based study investigating the prognostic value of palliative gastrectomy followed by chemotherapy among stage IV gastric SRCC patients. The major findings were that in stage IV gastric SRCC, there existed at least a selective group of patients who could have prolonged overall survival with palliative gastrectomy plus chemotherapy compared to chemotherapy alone.

Stage IV gastric signet ring cell carcinoma has long been considered to have worse survival rates compared with other types of adenocarcinoma.6, 19 Previous studies reported that gastric SRCC had high proportion of patients with poorly differentiated grade, younger age and female gender,6, 7, 20, 21, 22 which was consistent with the clinicopathological characteristics identified in our study. As to metastasis, the mechanism behind the formation of signet ring cell carcinoma may contribute to its unique features. It has been shown that the activation of PI3K (Phosphoinositide 3‐kinase) through the ErbB2 (Her2)/ ErbB3 (Her3) pathway in signet ring cells could enhance mucin secretion.23 Additionally, the adherent junction is disrupted via activation of the Mitogen‐activated protein kinase 1 (MEK1) pathway, which leads to the loss of cell‐cell contact.24 Further, it has been reported that signet ring cells were more likely to have transcoelomic metastasis than other gastric cancer cells.2, 25 These findings could explain the high frequency of metastasis and reoccurrence in gastric SRCC. In our study, the proportion of gastric cancer patients with distant metastasis was significantly higher in SRCC than in NOS (43.31% vs 34.08%, P < .001), which was consistent with the pathological features of SRCC reported by previous studies.23, 24, 25 However, further clinical and genetic analyses are still needed to establish improved therapeutic management of these stage IV patients.

Chemotherapy has been the standard palliative management for patients with metastatic gastric cancer.12 However, chemotherapy alone failed to maintain the long‐term survival in some part of stage IV gastric cancer patients.11, 26 The role of palliative gastrectomy for metastatic gastric cancer (mGC) had been assessed in several studies. The first evidence which proved that palliative gastrectomy could bring survival benefit for mGC patients was a Western retrospective analysis from the Dutch Gastric Cancer Trial in 2002.16 In this trial they included 285 mGC patients with incurable tumors and found that patients with palliative gastrectomy performed obtained prolonged overall survival than those without primary tumor resection (8.1 vs 5.4 months; P < .001). Similarly, a retrospective study in the East achieved the same conclusion in 2012.27 Results from this study suggested that palliative gastrectomy could improve the overall survival of patients with late‐stage gastric cancer who could not undergo radical surgery. However, the REGATTA trial proposed the opposite view.17 In this phase 3, randomized controlled trial, 89 advanced gastric cancer patients who received gastrectomy followed by chemotherapy failed to have longer median survival time compared to other 86 patients with chemotherapy alone (14.3 vs 16.6 months, one‐sided P = .70), indicating the low value of adding palliative gastrectomy to chemotherapy. As a result of these studies, the role of palliative gastrectomy is still controversial in mGC patients, not to mention that until now no research assesses the role of palliative gastrectomy in stage IV gastric SRCC patients.

In our study, palliative gastrectomy was proved as an independently favorable prognostic factor for metastatic gastric SRCC patients. In subgroup analysis, 13 of 17 subgroups of metastatic SRCC obtained survival benefit from PG+C compared to PG/C alone, especially for those with only one metastatic site. Some of previous studies suggested that SRCC is less chemo‐sensitive than non‐SRCC cancers,28, 29, 30, 31 so the value of palliative gastrectomy plus chemotherapy may be even higher in stage IV gastric SRCC than NOS. In addition, several recently published studies proved that improved long‐term survival was observed among stage IV GC patients who underwent conversion surgery (primary tumor resection performed in initially unresectable metastatic cancer after responding to chemotherapy).32, 33, 34, 35 This also cast light on the therapeutic role of palliative surgery strategies in stage IV gastric SRCC patients. Stage IV gastric cancer patients who were able to undergo surgery could have advantages over other mGC patients in terms of physical and disease conditions, which may account for the improved OS in these patients treated by surgery. Taken results from our study together, palliative gastrectomy is recommended to improve OS for stage IV gastric SRCC patients who have the potential opportunity to undergo surgery.

Although this study had strengths including the large sample size, subgroup analysis and PSM test, some limitations should also be explained. First, metastasis to peritoneum was not assessed in this study due to the absence of peritoneal metastasis data of gastric cancer patients in the SEER database. Thus, the influence of peritoneal metastasis among stage IV gastric SRCC should be further analyzed. Second, the SEER registry does not include detailed information concerning the dose, toxicity, or duration of chemotherapy, so we were not able to further analyze the effects of varying chemotherapy approaches. Finally, research bias could exist in this retrospective study; so the results of this study needed to be validated by future prospective trials.

5. CONCLUSION

Stage IV gastric SRCC is a type of malignant gastric cancer with higher metastasis rate and poorer overall survival compared to NOS. Results from our study suggest that there exists at least a selective group of metastatic gastric SRCC patients, who could benefit from palliative gastrectomy followed by chemotherapy compared to chemotherapy alone. Therefore, palliative gastrectomy is recommended for metastatic gastric SRCC patients who have the potential opportunity to undergo palliative surgery. However, further prospective trials are still needed to validate our results so that palliative gastrectomy could be cautiously considered into the management of metastatic gastric SRCC patients.

CONFLICT OF INTEREST

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

AUTHOR CONTRIBUTIONS

All authors read and approved the final manuscript. Conception/Design: Jia Wei; Collection and/or assembly of data: All authors; Data analysis and interpretation: All authors; Manuscript writing: Tao Shi; Review and editing, All authors; Final approval of manuscript: All authors.

Supporting information

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

The authors of this study have no contribution to SEER data collection. We would like to thank the SEER database for its open data access.

Shi T, Song X, Liu Q, et al. Survival benefit of palliative gastrectomy followed by chemotherapy in stage IV gastric signet ring cell carcinoma patients: A large population‐based study. Cancer Med. 2019;8:6010–6020. 10.1002/cam4.2521

Funding information

This work was funded by grants from The National Key Research and Development Program of China (No. 2017YFC1308900), The National Major Projects for "Major New Drugs Innovation and Development" (No. 2018ZX09301048‐003) and Program of Jiangsu Provincial Key Medical Center (No. YXZXB2016002). The funding sources had no role in the study design, data collection, data analysis, data interpretation, or writing of the report.

REFERENCES

- 1. Siegel RL, Miller KD, Jemal A. Cancer statistics, 2019. CA Cancer J Clin. 2019;69(1):7‐34. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Murakami H, Nakanishi H, Tanaka H, et al. Establishment and characterization of novel gastric signet‐ring cell and non signet‐ring cell poorly differentiated adenocarcinoma cell lines with low and high malignant potential. Gastric Cancer. 2013;16(1):74‐83. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Yamada M, Fukagawa T, Nakajima T, et al. Hereditary diffuse gastric cancer in a Japanese family with a large deletion involving CDH1. Gastric Cancer. 2014;17(4):750‐756. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Shu Y, Zhang W, Hou Q, et al. Prognostic significance of frequent CLDN18‐ARHGAP26/6 fusion in gastric signet‐ring cell cancer. Nat Commun. 2018;9(1):2447. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Bamboat ZM, Tang LH, Vinuela E, et al. Stage‐stratified prognosis of signet ring cell histology in patients undergoing curative resection for gastric adenocarcinoma. Ann Surg Oncol. 2014;21(5):1678‐1685. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Pernot S, Voron T, Perkins G, Lagorce‐Pages C, Berger A, Taieb J. Signet‐ring cell carcinoma of the stomach: impact on prognosis and specific therapeutic challenge. World J Gastroenterol. 2015;21(40):11428‐11438. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Bozkaya Y, Erdem GU, Ozdemir NY, et al. Comparison of clinicopathological and prognostic characteristics in patients with mucinous carcinoma and signet ring cell carcinoma of the stomach. Curr Med Res Opin. 2017;33(1):109‐116. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Hyung WJ, Noh SH, Lee JH, et al. Early gastric carcinoma with signet ring cell histology. Cancer. 2002;94(1):78‐83. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Piessen G, Messager M, Leteurtre E, Jean‐Pierre T, Mariette C. Signet ring cell histology is an independent predictor of poor prognosis in gastric adenocarcinoma regardless of tumoral clinical presentation. Ann Surg. 2009;250(6):878‐887. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Honoré C, Goéré D, Messager M, et al. Risk factors of peritoneal recurrence in eso‐gastric signet ring cell adenocarcinoma: results of a multicentre retrospective study. Eur J Surg Oncol. 2013;39(3):235‐241. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Ebinger SM, Warschkow R, Tarantino I, Schmied BM, Güller U, Schiesser M. Modest overall survival improvements from 1998 to 2009 in metastatic gastric cancer patients: a population‐based SEER analysis. Gastric Cancer. 2016;19(3):723‐734. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Ajani JA, D'Amico TA, Almhanna K, et al. Gastric cancer, version 3.2016, NCCN clinical practice guidelines in oncology. J Natl Compr Canc Netw. 2016;14(10):1286‐1312. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Pernot S, Dubreuil O, Aparicio T, et al. Efficacy of a docetaxel‐5FU‐oxaliplatin regimen (TEFOX) in first‐line treatment of advanced gastric signet ring cell carcinoma: an AGEO multicentre study. Br J Cancer. 2018;119(4):424‐428. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Seo HS, Song KY, Jung YJ, et al. Radical gastrectomy after chemotherapy may prolong survival in stage IV gastric cancer: a Korean multi‐institutional analysis. World J Surg. 2018;42(10):3286‐3293. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Sougioultzis S, Syrios J, Xynos ID, et al. Palliative gastrectomy and other factors affecting overall survival in stage IV gastric adenocarcinoma patients receiving chemotherapy: a retrospective analysis. Eur J Surg Oncol. 2011;37(4):312‐318. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Hartgrink HH, Putter H, Klein Kranenbarg E, Bonenkamp JJ, van de Velde C. Value of palliative resection in gastric cancer. Br J Surg. 2002;89(11):1438‐1443. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Fujitani K, Yang H‐K, Mizusawa J, et al. Gastrectomy plus chemotherapy versus chemotherapy alone for advanced gastric cancer with a single non‐curable factor (REGATTA): a phase 3, randomised controlled trial. Lancet Oncol. 2016;17(3):309‐318. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Hankey BF, Ries LA, Edwards BK. The surveillance, epidemiology, and end results program: a national resource. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev. 1999;8(12):1117‐1121. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Mizushima T, Nomura M, Fujii M, et al. Primary colorectal signet‐ring cell carcinoma: clinicopathological features and postoperative survival. Surg Today. 2010;40(3):234‐238. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Chon HJ, Hyung WJ, Kim C, et al. Differential prognostic implications of gastric signet ring cell carcinoma: stage adjusted analysis from a single high‐volume center in Asia. Ann Surg. 2017;265(5):946‐953. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Kwon K‐J, Shim K‐N, Song E‐M, et al. Clinicopathological characteristics and prognosis of signet ring cell carcinoma of the stomach. Gastric Cancer. 2014;17(1):43‐53. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Erickson LA. Gastric signet ring cell carcinoma. Mayo Clin Proc. 2017;92(6):e95‐e96. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Fukui Y. Mechanisms behind signet ring cell carcinoma formation. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2014;450(4):1231‐1233. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Chang YT, Shu CL, Fukui Y. Activation of the MEK pathway is required for complete scattering of MCF7 cells stimulated with heregulin‐beta1. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2013;433(3):311‐316. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Voron T, Messager M, Duhamel A, et al. Is signet‐ring cell carcinoma a specific entity among gastric cancers? Gastric Cancer. 2016;19(4):1027‐1040. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Kurimoto K, Ishigure K, Mochizuki Y, et al. A feasibility study of postoperative chemotherapy with S‐1 and cisplatin (CDDP) for stage III/IV gastric cancer (CCOG 1106). Gastric Cancer. 2015;18(2):354‐359. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Chen S, Li Y‐F, Feng X‐Y, Zhou Z‐W, Yuan X‐H, Chen Y‐B. Significance of palliative gastrectomy for late‐stage gastric cancer patients. J Surg Oncol. 2012;106(7):862‐871. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Robb WB, Messager M, Gronnier C, et al. High‐grade toxicity to neoadjuvant treatment for upper gastrointestinal carcinomas: what is the impact on perioperative and oncologic outcomes? Ann Surg Oncol. 2015;22(11):3632‐3639. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Messager M, Lefevre JH, Pichot‐Delahaye V,et al. The impact of perioperative chemotherapy on survival in patients with gastric signet ring cell adenocarcinoma: a multicenter comparative study. Ann Surg. 2011;254(5):684‐693; discussion 693. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Charalampakis N, Nogueras González GM, Elimova E, et al. The proportion of signet ring cell component in patients with localized gastric adenocarcinoma correlates with the degree of response to pre‐operative chemoradiation. Oncology. 2016;90(5):239‐247. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Lemoine N, Adenis A, Bouche O, et al. Signet ring cells and efficacy of first‐line chemotherapy in advanced gastric or oesogastric junction adenocarcinoma. Anticancer Res. 2016;36(10):5543‐5549. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Solaini L, Ministrini S, Bencivenga M, et al. Conversion gastrectomy for stage IV unresectable gastric cancer: a GIRCG retrospective cohort study. Gastric Cancer. 2019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Kinoshita J, Fushida S, Tsukada T, et al. Efficacy of conversion gastrectomy following docetaxel, cisplatin, and S‐1 therapy in potentially resectable stage IV gastric cancer. Eur J Surg Oncol. 2015;41(10):1354‐1360. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Yamaguchi K, Yoshida K, Tanahashi T, et al. The long‐term survival of stage IV gastric cancer patients with conversion therapy. Gastric Cancer. 2018;21(2):315‐323. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Zurleni T, Gjoni E, Altomare M, Rausei S. Conversion surgery for gastric cancer patients: a review. World J Gastrointest Oncol. 2018;10(11):398‐409. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials