Abstract

Angiotensin II (Ang II) elicits an Ang II type 2 (AT2) receptor-mediated increase in delayed-rectifier K+ current (IK) in neurons cultured from newborn rat hypothalamus and brainstem. This effect involves a pertussis toxin (PTX)-sensitive Gi protein and is abolished by inhibition of serine and threonine phosphatase 2A (PP-2A). Here, we determined that Ang II stimulates [3H]arachidonic acid (AA) release from cultured neurons via AT2 receptors. This effect of Ang II was blocked by inhibition of phospholipase A2 (PLA2) and by PTX. Because AA and its metabolites are powerful modulators of neuronal K+currents, we investigated the involvement of PLA2 and AA in the AT2 receptor-mediated stimulation ofIK by Ang II. Single-cell reverse transcriptase (RT)-PCR analyses revealed the presence of PLA2 mRNA in neurons that responded to Ang II with an increase in IK. The stimulation of neuronalIK by Ang II was attenuated by selective inhibitors of PLA2 and was mimicked by application of AA to neurons. Inhibition of lipoxygenase (LO) enzymes significantly reduced both Ang II- and AA-stimulated IK, and the 12-LO metabolite of AA 12S-hydroxyeicosatetraenoic acid (12S-HETE) stimulated IK. These data indicate the involvement of a PLA2, AA, and LO metabolite intracellular pathway in the AT2receptor-mediated stimulation of neuronal IKby Ang II. Furthermore, the demonstration that inhibition of PP-2A abolished the stimulatory effects of Ang II, AA, and 12S-HETE on neuronal IK but did not alter Ang II-stimulated [3H]-AA release suggests that PP-2A is a distal event in this pathway.

Keywords: angiotensin II, AT2 receptor, delayed-rectifier K+ current, phospholipase A2, arachidonic acid, lipoxygenase, serine and threonine phosphatase 2A, hypothalamus and brainstem neurons

Mammalian brain contains angiotensin II (Ang II) type 2 (AT2) receptors (Tsutsumi and Saavedra, 1991; Millan et al., 1992; Song et al., 1992), the functions of which are not well established. The fact that these sites are expressed in high levels in neonatal tissues has led to the idea that they have a role in development (Cook et al., 1991; Tsutsumi and Saavedra, 1991; Millan et al., 1992). Support for this has come from studies that determined that stimulation of AT2receptors causes neurite outgrowth in undifferentiated NG108–15 neuroblastoma × glioma cells (Laflamme et al., 1996) and causes apoptosis of pheochromocytoma PC-12W cells and R3T3 fibroblasts (Yamada et al., 1996; Horiuchi et al., 1997). Within the brain, blockade of periventricular AT2 receptors potentiates the Ang II type 1 (AT1) receptor-mediated stimulation of drinking and vasopressin secretion (Hohle et al., 1995), suggesting that AT1 and AT2 receptors may be antagonistic. In addition, mutant mice lacking the gene encoding the AT2receptor displayed decreased exploratory behavior and spontaneous movements compared with wild-type mice (Hein et al., 1995; Ichiki et al., 1995). Thus, AT2 receptors may be involved in the central control of certain behaviors and hormone secretion, as well as having putative roles in apoptosis and differentiation.

Similar to the in vivo situation, neurons cultured from the hypothalamus and brainstem of newborn rats contain high levels of AT2 receptors (Sumners et al., 1991), and we have used these cultures to determine the AT2 receptor-mediated effects of Ang II on membrane K+ currents. The rationale for this approach was that changes in these currents form the basis of changes in neuronal activity and ultimately of behavioral and physiological effects. We determined that Ang II, via AT2receptors, stimulates neuronal delayed-rectifier K+current (IK) and transient K+ current (IA) (Kang et al., 1993), effects mediated by an inhibitory G-protein (Gi) and abolished by inhibition of serine and threonine phosphatase 2A (PP-2A) (Kang et al., 1994). Our present investigations have centered around the possibility that phospholipase A2 (PLA2) is involved, because Ang II, via AT2 receptors, causes stimulation of PLA2activity in certain cell types (Lokuta et al., 1994; Jacobs and Douglas, 1996). PLA2 catalyzes the generation of arachidonic acid (AA) from membrane phospholipids, and AA and its metabolites such as hydroxyeicosatetraenoic acid (HETE), leukotrienes, and prostaglandins are known modulators of neuronal K+ channels (Premkumar et al., 1990; Schweitzer et al., 1993; Zona et al., 1993; Meves, 1994; Gubitosi-Klug et al., 1995;Kim et al., 1995). Furthermore, modulation of K+currents in sympathetic neurons and pituitary tumor cells involves lipoxygenase (LO) metabolites of AA and serine and threonine phosphatases (Duerson et al., 1996; Yu, 1995). The data presented here indicate that the AT2 receptor-mediated stimulation of neuronal IK by Ang II involves an intracellular pathway that includes PLA2, AA, and LO metabolites of AA. In addition, the results suggest that PP-2A may be important for the stimulation of neuronal IK produced by Ang II and AA.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Materials. Newborn Sprague Dawley rats were obtained from our breeding colony, which originated from Charles River Laboratories (Wilmington, MA). DMEM and TRIzol reagent were obtained from GIBCO-BRL (Gaithersburg, MD). Plasma-derived horse serum (PDHS) was from Central Biomedia (Irwin, MO). [5,6,8,9,11,12,14,15-3H]Arachidonic acid ([3H]-AA; specific activity of 203 Ci/mmol) and [1-3H]ethan-1-ol-2-amine HCL ([3H]ethanolamine; specific activity of 18.0 Ci/mmol) were purchased from Amersham (Arlington Heights, IL). Losartan potassium was generously provided by Merck (Darmstadt, Germany). PD123,319, nodularin (NDL), and antiflammin-2 were purchased from Research Biochemicals (Natick, MA). AA was from Calbiochem (La Jolla, CA). Polyclonal anti-phospholipase A2(anti-PLA2) antibodies were purchased from Upstate Biotechnology (Lake Placid, NY). Activated silicic acid (200–325 mesh; Unisil) was from Clarkson Chemical (Williamsport, PA). Gene-Amp reverse transcriptase (RT)-PCR kits and all reagents for RT-PCR were purchased from Perkin-Elmer (Norwalk, CT). Bovine serum albumin (BSA), Ang II, tetrodotoxin (TTX), dipotassium ATP, sodium GTP, pertussis toxin (PTX), cadmium chloride (CdCl2), HEPES, phosphatidylcholine (PC), phosphatidylethanolamine (PE), phosphatidylserine (PS), phosphatidylinositol (PI), 4-bromophenacyl bromide (4-BPB), nordihydroguiaretic acid (NDGA), indomethacin, and 12S-hydroxy-(5Z,8Z,10E,14Z)-eicosatetraenoic acid (12S-HETE) were purchased from Sigma (St. Louis, MO). All other chemicals were purchased from Fisher Scientific (Houston, TX) and were of analytical grade or higher. Oligonucleotide primers for the rat brain cytosolic PLA2 gene (Owada et al., 1994) and the rat AT2 receptor gene (Mukoyama et al., 1993) were synthesized in the DNA core facility of the Interdisciplinary Center for Biotechnology Research, University of Florida. The sequences of these primers are as follows: PLA2 gene, sense: 5′-GCTCCACATGGTACATGTCA-3′; antisense, 5′-CTTCAAGCTACTCAAGGTCG-3′; AT2 receptor gene, sense, 5′-ACCTGCATGAGTGTCGATAG-3′; antisense: 5′- GGATAGACAAGCCATACACC-3′.

Preparation of cultured neurons. Neuronal cocultures were prepared from the brainstem and a hypothalamic block of newborn Sprague Dawley rats exactly as described previously (Sumners et al., 1991). Cultures were grown in DMEM and 10% PDHS for 10–14 d, at which time they consisted of ∼90% neurons and ∼10% astrocyte glia and microglia, as determined by immunofluorescent staining (Sumners et al., 1994).

Analysis of PLA2 activity. Stimulation of PLA2 activity results in generation of AA and of a lysophospholipid, and so we analyzed the effects of Ang II on the generation of both AA and lysophosphatidylethanolamine (LPE) as an index of PLA2 activity. The generation of AA was analyzed as the release of [3H]-AA from neuronal membrane phospholipids, essentially as described by Wakelam and Currie (1992). In preliminary experiments we demonstrated that preincubation of cultured neurons with [3H]-AA (1.0 μCi/well) for 24 hr at 37°C resulted in equilibrium incorporation of the [3H]-AA into PE, PC, PS, and PI, as determined using thin layer chromatography (TLC) on silica gel 60 plates with a solvent of chloroform:methanol:glacial acetic acid:water (75:45:3:1). This time point was used in all subsequent experiments.

For the analyses of AA generation, we measured the release of [3H]-AA into the incubation medium from neurons that had been prelabeled with [3H]-AA for 24 hr in DMEM and 10% PDHS. The medium containing [3H]-AA was removed from the cells, which were then washed 3 times with 0.5 ml of Hank’s Balanced Glucose (HBG) solution containing (in mm): 137 NaCl, 5.36 KCl, 1.66 MgSO4, O.49 MgCl2, 1.26 CaCl2, 0.35 Na2HPO4, 4.17 NaHCO3, and 10 glucose and 1% BSA, pH 7.4. The final wash of HBG was removed and replaced with 0.5 ml of HBG containing control solution, Ang II, or drugs for 1–5 min. Next, the incubation medium was removed from each well and underwent chloroform and methanol extraction, followed by isolation of the [3H]-AA using silicic acid adsorption chromatography (Wakelam and Currie, 1992). The amount of AA released into the medium was expressed as [3H]-AA released (dpm/well).

The generation of LPE was analyzed as the production of [3H]-LPE from [3H]-PE. Cultured neurons were preincubated with [3H]ethanolamine (2.0 μCi/well) for 48 hr at 37°C in DMEM and 10% PDHS, conditions that produced equilibrium incorporation into [3H]-PE. After this, the medium containing [3H]ethanolamine was removed, and the cells were washed 3 times with 0.5 ml of HBG and then incubated with control solution (HBG) or Ang II for 0.5–2.0 min. Next, the incubation medium was discarded, and the cellular [3H]-LPE content was analyzed as detailed by Wakelam and Currie (1992). Briefly, cells underwent chloroform and methanol extraction, followed by isolation of the [3H]-LPE using TLC (chloroform:methanol:glacial acetic acid:water; 50:30:8:3). Spots corresponding to [3H]-LPE were removed, and the data were expressed as dpm [3H]-LPE/well.

Electrophysiological recordings. Macroscopic K+ current was recorded using the whole-cell configuration of the patch-clamp technique as described previously (Hamill et al., 1981; Kang et al., 1994). Experiments were performed at room temperature (22–23°C) using an Axopatch-1D amplifier and Digidata 1200A interface (Axon Instruments, Burlingame, CA). Neurons were bathed in modified Tyrode’s solution containing (in mm): 140 NaCl, 5.4 KCl, 2.0 CaCl2, 2.0 MgCl2, 0.3 NaH2PO4, 10 HEPES, 0.0001 TTX, 0.1 CdCl2, and 10 dextrose, pH 7.4 (NaOH). The patch electrodes had resistances of 3–4 MΩ when filled with an internal pipette solution containing (in mm): 140 KCl, 2 MgCl2, 5 EGTA, 4 ATP, 0.1 GTP, 10 dextrose, and 10 HEPES, pH 7.2 (KOH). For whole-cell recordings, cell capacitance was canceled electronically, and the series resistance (<10 MΩ) was compensated for by 75–80%. Data acquisition and analysis were performed using pCLAMP 6.03. Whole-cell currents were digitized at 3 kHz and filtered at 1 kHz (−3 dB frequency filter). The current measurements from which mean current densities were derived were made 50 msec after the initiation of the test pulse, at which time the current measurements reflect onlyIK (Kang et al., 1994). Current density was reported as pA/pF. The average cell capacitance for neurons used in this study was 33.9 ± 13.7 pF.

Extraction of total RNA and RT-PCR. Growth media were removed from cultured neurons that were then washed once with ice-cold Tyrode’s solution, pH 7.4. After this, neurons were lysed in TRIzol reagent (0.5 ml/dish), and total RNA was extracted as detailed previously (Huang et al., 1997). For the experiments using neurons from the whole dish, RT-PCR of the AT2 receptor and PLA2 was performed using Gene-Amp RT-PCR kits essentially as described by Huang et al. (1997). In brief, PCR was performed at 94°C for 4 min, followed by 38 cycles at 94°C for 45 sec, 63°C (for PLA2) or 62°C (for AT2 receptor) for 1 min 40 sec, and 72°C for 2 min. After final extension at 72°C for 10 min, PCR products were electrophoresed on a 2% agarose gel containing 1 μg/ml ethidium bromide. Using these conditions, we observed the production of a 263 bp PLA2-specific DNA and a 117 bp AT2 receptor-specific DNA from the PCR, which correspond to the PLA2 and AT2 receptor mRNAs, respectively.

For the experiments using single neurons, RT-PCR of the AT2 receptor and PLA2 was performed using the following procedures. Using the electrophysiological methods described above, whole-cell recordings of IK were made from neurons superfused with Ang II. For these recordings, the glass patch pipettes were washed once in ethanol and 3 times in distilled water and were then autoclaved for 30 min. Pipettes were then dried at 200°C for 1.5 hr. These patch pipettes were kept in a sealed box under vacuum until used for recordings. After the recordings ofIK, the neuronal intracellular contents were drawn into the tip of the patch pipette using negative pressure, and the tip was then broken off inside an RT-PCR tube. The volume of patch pipette solution and intracellular contents in the broken tip was ∼6.5 μl, and this was adjusted to 8 μl with patch pipette solution for the RT-PCR, which was performed using Gene-Amp RT-PCR kits. A first PCR was performed exactly as described previously for neurons from the whole dish. A second PCR was performed (on 20 μl of the first PCR products) at 94°C for 4 min, followed by 30 cycles (for PLA2) or 36 cycles (for AT2 receptor) at 94°C for 45 sec, 63°C (for PLA2) or 62°C (for AT2 receptor) for 1 min 40 sec, and 72°C for 2 min. After final extension at 72°C for 10 min, the PCR products were electrophoresed on a 2% agarose gel containing 1 μg/ml ethidium bromide. Using these conditions for single cell RT-PCR, we observed the production of 263 bp PLA2- and 117 bp AT2receptor-specific DNAs, similar to the bands obtained when using neurons from the whole dish. In all situations, exclusion of either RNA or murine leukemia virus reverse transcriptase resulted in no visible bands after gel electrophoresis.

Drug applications. Ang II, drugs, and anti-PLA2antibodies were dissolved in the appropriate solvent and then diluted in HBG (for the [3H]-AA and [3H]-LPE analyses) or in superfusate solution, patch pipette solution, or DMEM (for the electrophysiological experiments). In all experiments, solvent controls were performed for each protocol.

Experimental groups and data analysis. For individual [3H]-AA and [3H]-LPE analyses, each data point was obtained from four and three wells, respectively. Electrophysiological analyses were performed with the use of multiple 35 mm dishes of neurons. Comparisons were made with the use of a one-way ANOVA followed by the Newman–Keuls test to assess statistical significance.

RESULTS

Ang II stimulates PLA2 activity in cultured neurons

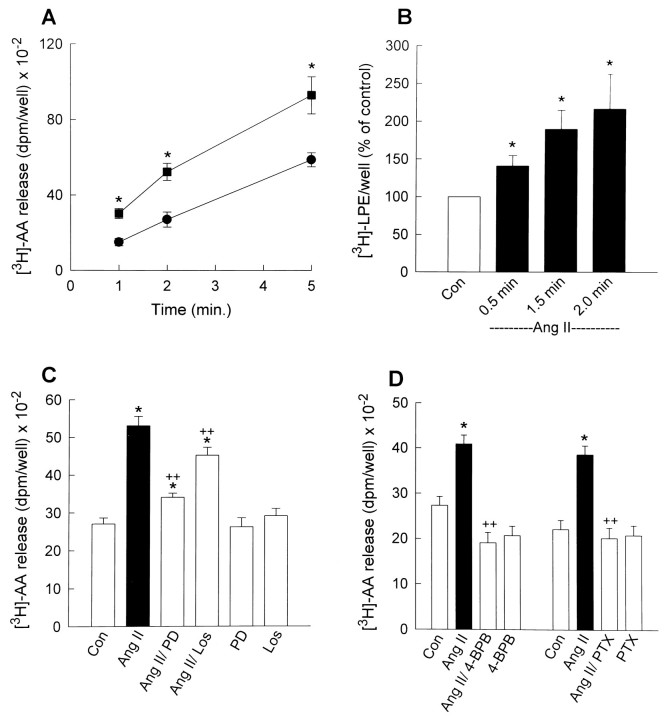

As stated in the Materials and Methods, the effects of Ang II on the generation of AA and LPE were used as an index of stimulation of PLA2 activity. In preliminary experiments, we determined that Ang II (100 nm; 1–5 min) stimulates release of radiolabel from cultured neurons that had been preincubated with [3H]-AA (1.0 μCi/well) (data not shown). This suggested that Ang II caused release of [3H]-AA, and in subsequent experiments, this was tested by performing silicic acid chromatography of the media extracts. Incubation of cultured neurons with control solution (HBG) for 1–5 min resulted in increasing amounts of [3H]-AA released as a function of time (Fig. 1A). Inclusion of Ang II (100 nm) in the incubation media resulted in a significant increase in the levels of [3H]-AA released at all time points (Fig. 1A). In an additional set of experiments, we determined that incubation of cultured neurons with Ang II (100 nm; 0.5–2 min) elicited a significant time-dependent stimulation of [3H]-LPE production (Fig. 1B). Taken together, the data presented in Figure 1, A andB, indicate that Ang II stimulates PLA2 activity in cultured neurons. The stimulatory effects of Ang II (100 nm) on [3H]-AA release from cultured neurons were significantly reduced (by ∼73%) by the addition of the selective AT2 receptor blocker PD123,319 (PD; 1 μm) to the incubation media (Fig. 1C). By contrast, the AT1-selective receptor antagonist losartan (Los; 1 μm) reduced the stimulatory effects of Ang II on [3H]-AA release by ∼30% (Fig. 1C). Combined incubations with both PD (1 μm) and Los (1 μm) resulted in complete inhibition of the effects of Ang II (data not shown). Neither PD nor Los alone had significant effects on [3H]-AA release (Fig. 1C). These data indicate that both AT2 and AT1 receptors are involved in Ang II-stimulated [3H]-AA release from cultured neurons. Because the majority of AT1 and AT2 receptors in these cultures are present on different neurons (Gelband et al., 1997), it is probable that the AT1and AT2 receptor-mediated effects of Ang II on AA release are on different cells. In the presence of 1 μm Los, to block AT1 receptors, the stimulation of [3H]-AA release by Ang II (100 nm) was completely abolished by pretreatment of cultured neurons with the selective PLA2 inhibitor 4-BPB (10 μm; 30 min) (Fig. 1D). These data suggest that the AT2 receptor-mediated component of Ang II-stimulated [3H]-AA release is attributable to activation of PLA2.

Fig. 1.

Ang II stimulates PLA2activity in cultured neurons. A, Cultured neurons were prelabeled with [3H]-AA (1.0 μCi/well) for 24 hr at 37°C and then incubated with 0.5 ml of HBG/well in the absence (•; control) or presence (▪) of 100 nm Ang II for the indicated times at 37°C. This was followed by analysis of [3H]-AA release into the growth media as detailed in the Materials and Methods. Data are mean ± SEM from four experiments; *, significantly different from controls,p < 0.05. B, Cultured neurons were prelabeled with [3H]-ethanolamine (2.0 μCi/well) for 48 hr at 37°C and then incubated with 0.5 ml of HBG in the absence (Con) or presence of 100 nm Ang II for the indicated times at 37°C. This was followed by analysis of cellular [3H]-LPE as detailed in the Materials and Methods. Data are mean ± SEM from four experiments and are presented as a percent of control (100%). Control cellular [3H]-LPE was 2258 ± 279 dpm/well; *, significantly different from Con, p< 0.05. C, Cultured neurons that had been prelabeled with [3H]-AA as described above were incubated with 0.5 ml of HBG/well in the absence (CON) or presence of either 100 nm Ang II, Ang II plus 1 μm PD, Ang II plus 1 μm Los, PD, or Los for 2 min at 37°; analysis of [3H]-AA release into the growth media followed. Data are mean ± SEM from five experiments; *, significantly different from control,p < 0.05; ++Significantly different from Ang II-treated cells, p < 0.05. D, Cultured neurons that had been prelabeled with [3H]-AA as described above were preincubated with 4-BPB (10 μm; 30 min), PTX (200 ng/ml; 24 hr), or control solvent. After this, control and drug-treated cultures were incubated with 100 nm Ang II for 2 min at 37°C. All incubations were performed in the presence of 1 μm Los and were followed by analysis of [3H]-AA release into the growth media. Data are mean ± SEM from three (4-BPB) and four (PTX) experiments; *significantly different from control,p < 0.05; ++, significantly different from Ang II-treated neurons, p < 0.05.

In previous studies, we had determined that neuronal AT2receptors couple to a stimulation of IK via a PTX-sensitive inhibitory G-protein (Gi) (Kang et al., 1994). Therefore, we tested the effects of PTX, which inhibits both Gi and Go, on Ang II-stimulated [3H]-AA release. Preincubation of cultured neurons with PTX (200 ng/ml; 24 hr) completely abolished the stimulation of [3H]-AA release produced by Ang II (100 nm) in the presence of 1 μm Los (Fig.1D). These data provide indirect support for the idea that the AT2 receptor-mediated stimulation of [3H]-AA release by Ang II involves a Gi protein.

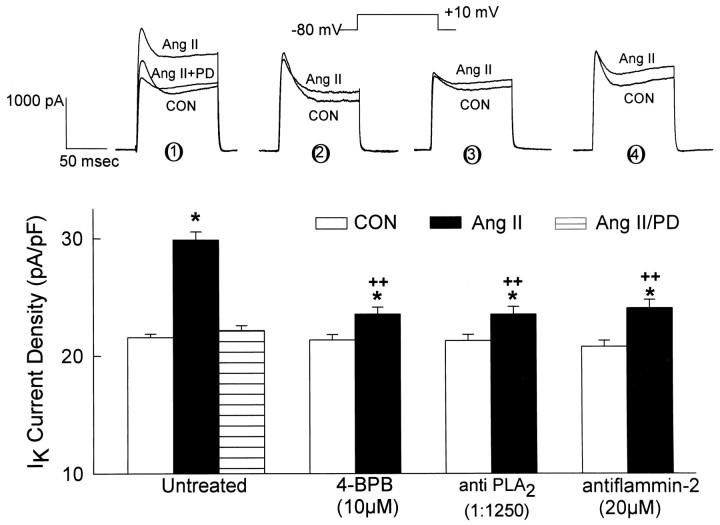

Stimulation of neuronal IK by Ang II involves PLA2 and AA

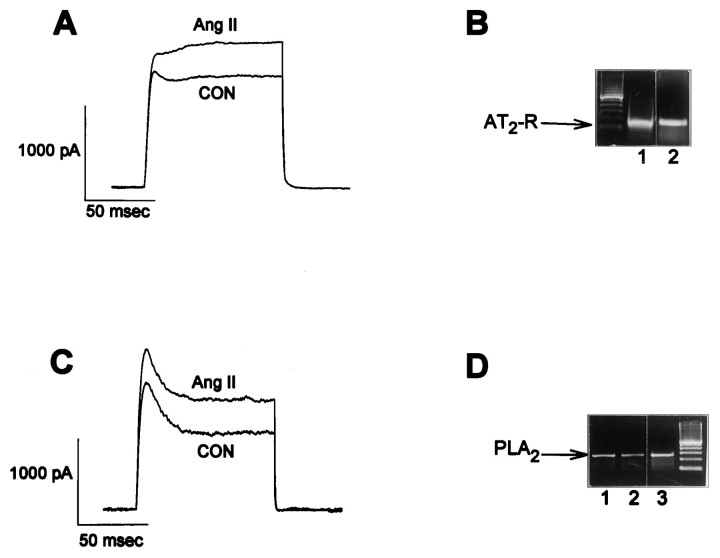

In previous studies, we determined that selective stimulation of neuronal AT2 receptors caused an increase inIK (Kang et al., 1993), whereas selective stimulation of neuronal AT1 receptors caused a decrease inIK (Sumners et al., 1996). Because some neurons in these cultures contain both AT1 and AT2receptors, with potentially offsetting effects onIK (Gelband et al., 1997), all of the present electrophysiological studies on AT2 receptors were performed in the presence of the AT1 receptor blocker Los (1 μm). Los did not alter baselineIK. In the present studies, superfusion of cultured neurons with Ang II (100 nm) caused a significant stimulation of IK that was completely inhibited by 1 μm PD123,319 (Fig. 2), in agreement with our previous experiments (Kang et al., 1993). Treatment of cultured neurons with PLA2 inhibitors significantly attenuated the AT2 receptor-mediated stimulation of IK by Ang II. For example, pretreatment with 4-BPB (10 μm; 30 min) or inclusion of antiflammin-2 (20 μm) in the pipette solution resulted in a 70–76% inhibition of Ang II-stimulated IK(Fig. 2). Furthermore, intracellular perfusion of anti-PLA2antibodies (1:1250) caused an ∼76% inhibition of Ang II-stimulatedIK (Fig. 2). These effects of 4-BPB, antiflammin-2, and anti-PLA2 antibodies were maximal and specific, i.e., higher concentrations produced no greater inhibition of Ang II-stimulated IK (data not shown). Control recordings in the presence of these inhibitors were not significantly different compared with control recordings of IKfrom untreated neurons (Fig. 2). The data presented in Figure 2therefore indicate that PLA2 is involved in the AT2 receptor-mediated stimulation ofIK by Ang II. If this is the case, it follows that the Ang II-responsive neurons should contain PLA2. This was tested by performing single-cell RT-PCR analyses of PLA2 mRNA in neurons that responded to Ang II with an increase in IK. The data in Figure3, A and B, demonstrate the presence of AT2 receptor mRNA in neurons from the whole dish and in a single neuron that responded to Ang II (100 nm) with an increase in IK. Furthermore, Figure 3, C and D, demonstrates the presence of PLA2 mRNA in neurons from the whole dish and in a single neuron that exhibited an AT2 receptor-mediated increase in IK elicited by Ang II (100 nm).

Fig. 2.

Stimulation of neuronalIK by Ang II via AT2 receptors: effect of PLA2 inhibitors. IKwas recorded during 100 msec voltage steps from a holding potential of −80 to +10 mV. Top, Representative currenttracings showing the effects of superfused Ang II (100 nm) on IK in untreated (control) neurons (± 1 μm PD123,319) (1), in neurons pretreated with 10 μm 4-BPB for 30 min (2), in neurons perfused intracellularly with anti-PLA2 antibodies (1:1250; for procedures, see Zhu et al., 1997) (3), and in neurons pretreated with 20 μm antiflammin-2 for 20 hr (4). Control recordings (CON) in all sets oftraces were made before application of Ang II. All recordings were made in the presence of 1 μm Los to block AT1 receptors. Bottom, Bar graphs showing mean ± SEM of current densities obtained in each treatment situation. Sample sizes were 15, 8, 7, and 6 neurons for the untreated, 4-BPB, anti-PLA2, and antiflammin-2 groups, respectively; *p < 0.001 compared with the respective control; ++p < 0.001 compared with Ang II alone (no 4-BPB, anti-PLA2, or antiflammin-2).

Fig. 3.

Stimulation of neuronalIK by Ang II: presence of AT2receptor mRNA and PLA2 mRNA in Ang II-responsive neurons.A, C, Current tracingsfrom two neurons showing stimulation of IK(AT2 receptor-mediated) by 100 nm Ang II.IK was recorded as described in Figure 2. After these recordings, the neurons were prepared for single cell RT-PCR as detailed in the Materials and Methods. B, Ethidium bromide-stained gels showing the RT-PCR DNA products that correspond to the AT2 receptor mRNA (AT2-R; 117 bp). Lane 1, AT2-R mRNA from the responsive neuron shown in A. Lane 2,AT2-R mRNA obtained from a whole dish of neurons. Leftmost lane is 100 bp DNA ladder.D, Ethidium bromide-stained gels showing the RT-PCR products that correspond to the PLA2 mRNA (263 bp).Lanes 1, 2, PLA2 mRNA obtained from a whole dish of neurons. Lane 3, PLA2 mRNA from the responsive neuron shown inC. Rightmost lane is 100 bp DNA ladder.

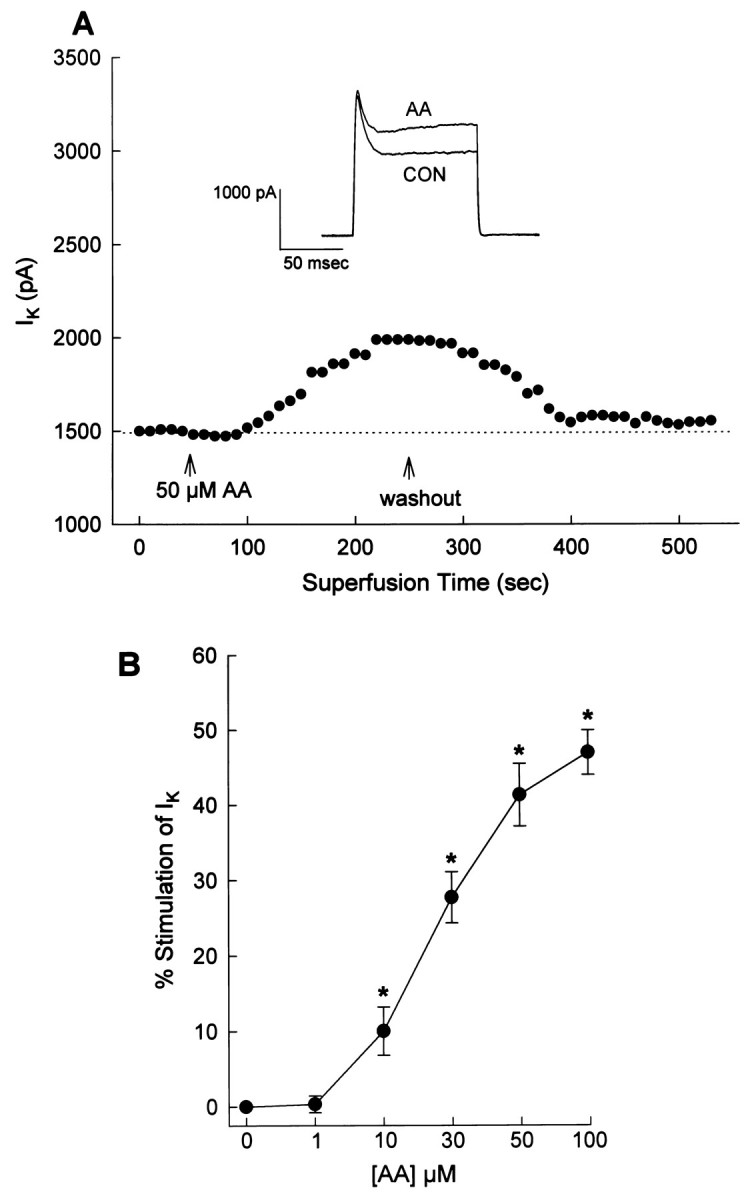

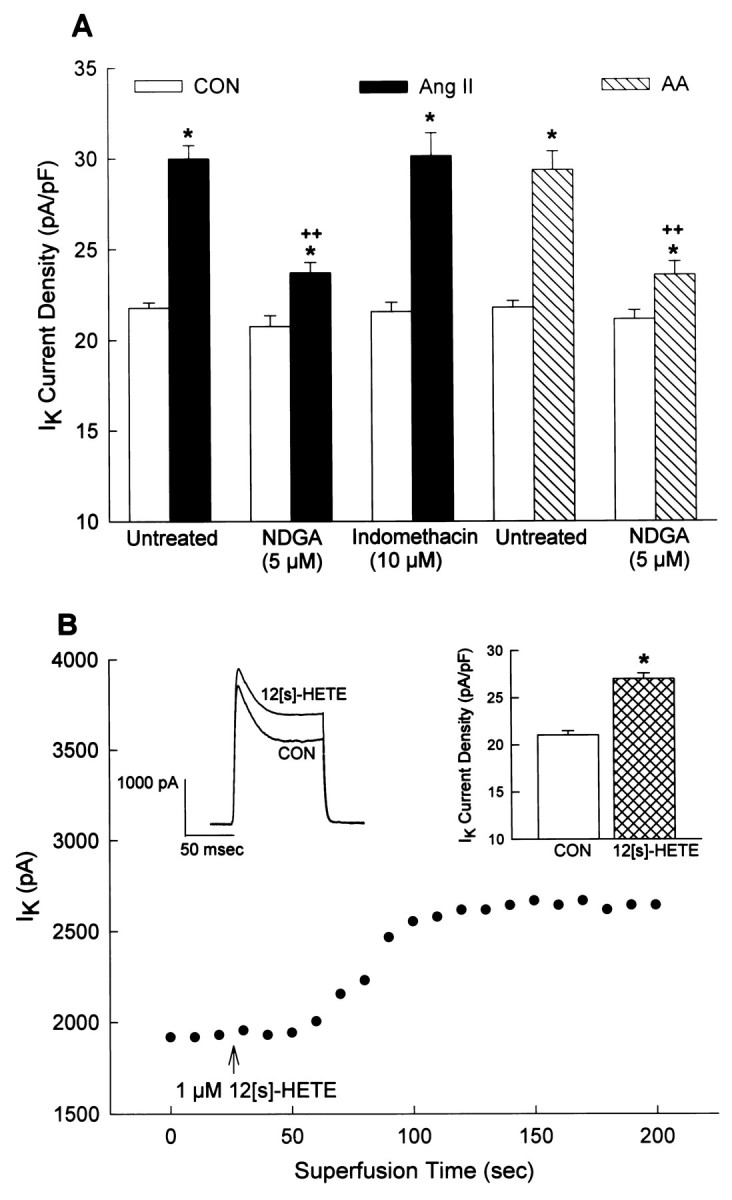

Activation of PLA2 results in generation of AA, and it is known that AA as well as some AA metabolites can modulate K+ currents and channels (Premkumar et al., 1990;Schweitzer et al., 1993; Zona et al., 1993; Meves, 1994; Gubitosi-Klug et al., 1995; Kim et al., 1995; Duerson et al., 1996; Yu, 1995). Therefore, if PLA2 is involved in mediating the stimulatory effects of Ang II on IK, then we might predict that AA would mimic the effects of Ang II. This was the case as superfusion of AA (10–100 μm) onto neurons produced a reversible and concentration-dependent stimulation ofIK (Fig.4A,B). The stimulatory effects of both Ang II and AA on neuronalIK were significantly reduced (by ∼77%) by the pretreatment of cultures with the general LO inhibitor NDGA (5 μm) (Fig. 5A). By contrast, pretreatment with the cyclooxygenase inhibitor indomethacin (10 μm) did not alter the stimulation of neuronal IK by Ang II (Fig. 5A) or by AA (data not shown). Higher concentrations of NDGA produced no further inhibition of Ang II-stimulated IK. Control recordings in the presence of NDGA and indomethacin were not significantly different from control recordings ofIK in untreated neurons (Fig. 5A). These data suggest that the stimulatory actions of Ang II and AA on neuronal IK are mostly mediated via LO metabolites of AA. This idea is supported by experiments that demonstrate that intracellular perfusion of 12S-HETE, a 12-lipoxygenase (12-LO) metabolite of AA, elicits a significant stimulation of neuronal IK (Fig.5B).

Fig. 4.

AA stimulates IK in cultured neurons. IK was recorded as described in Figure 2. A, Representative currenttracings and time course showing the effects of superfused AA (50 μm) on IK. Control (Con) recordings were made before application of AA. B, Effects of different concentrations of AA onIK. Data are mean ± SEM of percent stimulation of IK above control (0 onx-axis). Sample sizes were five to six neurons at each concentration; *significantly different from control,p < 0.001.

Fig. 5.

Stimulation of neuronalIK by Ang II and AA: role of LO metabolites of AA. IK was recorded as described in Figure 2. A, Cultured neurons were pretreated with either control solvent (untreated), NDGA (5 μm), or indomethacin (10 μm) for 5 min at room temperature and then were superfused with control solution (superfusate;Con), 100 nm Ang II, or 50 μmAA. Data are mean ± SEM of current densities obtained in each treatment situation. For the Ang II data, sample sizes were 14, 6, and 7 neurons in the untreated, NDGA, and indomethacin groups, respectively. For the AA data, sample sizes were 9 and 7 neurons in the untreated and NDGA groups, respectively; *p < 0.001 compared with the respective control; ++p < 0.001 compared with Ang II or AA alone (no NDGA). B, Representative current tracings and time course show the effects of intracellular application of 12S-HETE (1 μm) on IK. Control (Con) recordings were made before the application of 12S-HETE, which was performed via an intracellular perfusion technique as detailed previously (Zhu et al., 1997).Bar graphs are mean ± SEM ofIK values in Con and 12S-HETE-treated neurons. Sample size was seven neurons; *significantly different from control, p < 0.001.

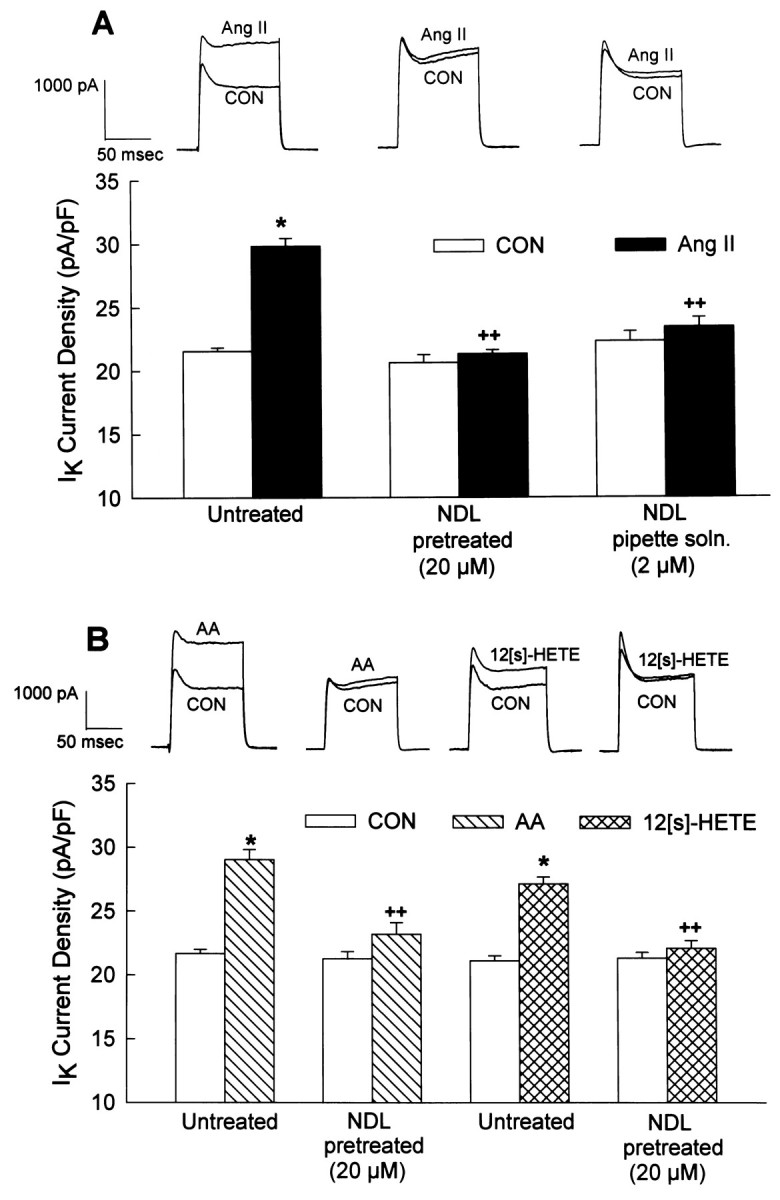

Inhibition of PP-2A blocks the stimulatory effects of Ang II, AA, and 12S-HETE on neuronal IK

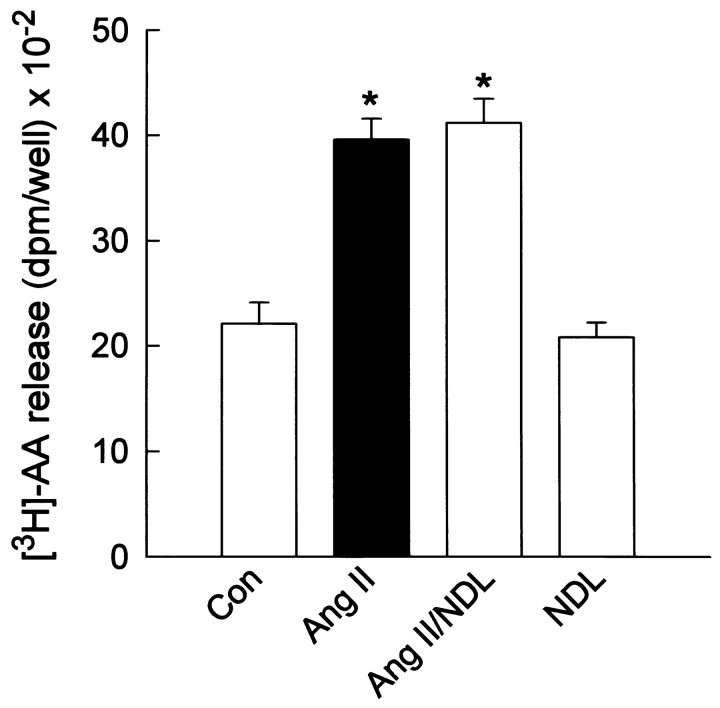

Our previous studies suggested that the AT2receptor-mediated stimulation of IK by Ang II was inhibited by low concentrations of the selective PP-2A inhibitor okadaic acid (Kang et al., 1994). This was confirmed in the present study by the demonstration that the PP-2A inhibitor nodularin (NDL) (Honkanen et al., 1991) completely reversed the stimulation of neuronalIK by Ang II (100 nm) (Fig.6A). The data presented in Figure 6A are from neurons pretreated with NDL (20 μm; 24 hr) or treated with NDL (2 μm) in the pipette solution. Similarly, pretreatment of cultured neurons with 20 μm NDL for 24 hr abolished the stimulation of neuronalIK either by superfusion of AA (50 μm) or by intracellular perfusion of 12S-HETE (1 μm) (Figure 6B). These data support the idea that PP-2A is involved in the stimulatory effects of Ang II, AA, and 12S-HETE on IK. In addition, the AA data suggest that PP-2A is involved at a locus distal to the generation of AA by PLA2. This is supported by the fact that AT2 receptor-mediated stimulation of [3H]-AA release by Ang II was not altered by NDL (20 μm; 24 hr pretreatment) (Fig.7).

Fig. 6.

Inhibition of PP-2A blocks the stimulatory effects of Ang II and AA on neuronal IK.IK was recorded as described in Figure 2.A, Neurons were superfused with control solution (superfusate; CON) or Ang II (100 nm) in the absence (untreated) or presence of NDL (either pretreatment with 20 μm NDL for 24 hr or inclusion of 2 μmNDL in the pipette solution). All recordings were made in the presence of a constant superfusion of 1 μm Los.Top, Representative current tracings show the effects of Ang II on IK in each treatment situation. Bottom, Bar graphsare mean ± SEM of the current densities in each treatment group. Sample sizes were 17, 6, and 5 neurons in the untreated, NDL (pretreatment), and NDL (pipette solution) groups, respectively; *p < 0.001 compared with respective control; ++,p < 0.001 compared with Ang II alone (no NDL).B, Neurons were superfused with control solution (superfusate; CON) or AA (50 μm) or were perfused intracellularly with control solution (patch pipette solution; Con) or 12S-HETE (1 μm). Application of AA and 12S-HETE was made in the absence (untreated) or presence of NDL (20 μm; pretreatment for 24 hr). Top, Representative current tracings show the effects of AA and 12S-HETE on IK in both treatment situations. Bottom, Bar graphsare mean ± SEM of current densities in the treatment groups. Sample sizes were 14 and 5 neurons for the untreated and NDL groups (AA superfusions), respectively. Sample sizes were 8 and 9 neurons for the untreated and NDL groups (12S-HETE application), respectively. *p < 0.001 compared with respectiveIK control value; ++, p< 0.001 compared with AA or 12S-HETE alone (no NDL).

Fig. 7.

Ang II-stimulated [3H]-AA release from cultured neurons: effects of nodularin. Cultures were prelabeled with [3H]-AA (1.0 μCi/well) for 24 hr at 37°C. At the same time, cultures were also preincubated with control solvent or NDL (20 μm) for 24 hr. After this, control and NDL-treated cultures were incubated with 0.5 ml/well of HBG in the absence (CON) or presence of 100 nm Ang II for 2 min at 37°C. Incubations were performed in the presence of 1 μm Los. These incubations were followed by analysis of [3H]-AA release into the growth media as detailed in the Materials and Methods. Data are mean ± SEM from four independent experiments; *significantly different from control, p < 0.001.

DISCUSSION

The data presented here indicate that Ang II stimulates, via AT1 and AT2 receptors, production of AA in neurons cultured from newborn rat hypothalamus and brainstem. This demonstration is reasonable considering that activation of either AT1 or AT2 receptors elicits a stimulation of AA release in various peripheral cells (Lokuta et al., 1994; Rao et al., 1994; Jacobs and Douglas, 1996; Pueyo et al., 1996). Within cultured neurons, the majority of this Ang II response is mediated via AT2 receptors (Fig. 1C), which is consistent with the demonstration that these cultures contain greater numbers of AT2 receptors than AT1 receptors (Sumners et al., 1991). Most of the AT1 and AT2 receptors in these cultures are located on different populations of neurons (Gelband et al., 1997), and so it is probable that these stimulatory actions of Ang II on AA release occur via AT1 and AT2 receptors located on different cells. The release of AA stimulated by Ang II may occur via various mechanisms. For example, we have determined previously that Ang II, via AT1 receptors, stimulates phospholipase C, phosphoinositide hydrolysis, and production of diacylglycerol in cultured neurons (Sumners et al., 1994, 1996). It is well known that AA can be released from diacylglycerol via the action of diacylglycerol lipase (Irvine, 1982). Therefore, in the present study the AT1 receptor-mediated effects of Ang II may occur via sequential activation of phospholipase C and diacylglycerol lipase (Irvine, 1982). By contrast, the AT2receptor-mediated stimulation of AA release in cultured neurons seems to occur via activation of PLA2, because this effect was abolished by the selective PLA2 inhibitor 4-BPB (Fig.2A; Schweitzer et al., 1993; Williams et al., 1994). Our data also indicate that the Ang II-induced stimulation of AA release, via AT2 receptors, is abolished by PTX (Fig.1D). This is consistent with our previous observations that neuronal AT2 receptors couple intracellularly via a PTX-sensitive Gi protein (Kang et al., 1994; Huang et al., 1995) and also with studies that have shown that the AT2 receptor coprecipitates with Giα2 and Giα3 proteins (Zhang and Pratt, 1996). However, at present we have no indication whether the AT2 receptor-mediated stimulation of AA release occurs via direct coupling of Gi to PLA2 or via an indirect intracellular mechanism (Axelrod et al., 1988; Dickerson and Weiss, 1995).

The present studies also indicate that activation of PLA2and the subsequent generation of AA and LO metabolites of AA are involved in the AT2 receptor-mediated stimulation ofIK by Ang II. Support for this comes from the fact that these Ang II-responsive neurons contain PLA2, as evidenced by single-cell RT-PCR analyses and from the demonstration that PLA2 inhibitors significantly attenuate the AT2 receptor-mediated stimulation of neuronal IK. However, the failure of PLA2 inhibitors to abolish completely the stimulation of neuronal IK by Ang II probably indicates that another mechanism or pathway is also involved. One possibility is that the neuronal AT2 receptor can also influenceIK by direct membrane-delimited coupling between Gi subunits and the delayed-rectifier K+channel that is involved. AA and LO metabolites of AA are known modulators of neuronal ionic currents and channels (Premkumar et al., 1990; Schweitzer et al., 1993; Zona et al., 1993; Meves, 1994;Gubitosi-Klug et al., 1995; Kim et al., 1995; Duerson et al., 1996; Yu, 1995), and their involvement in the stimulation of neuronalIK by Ang II is suggested by a number of observations. First, both AA and 12S-HETE (a 12-LO metabolite of AA) elicit significant stimulatory effects on neuronalIK similar to that obtained with Ang II via AT2 receptors. Second, the stimulatory effects of Ang II and AA on neuronal IK are significantly attenuated by inhibition of LO but not by inhibition of cyclooxygenases. The observation that LO inhibitors do not completely block these effects of Ang II and AA may suggest that the stimulation of IK is partially mediated via a direct action of AA at the K+ channel, as shown in other systems (Schweitzer et al., 1993; Kim et al., 1995). Many questions remain to be answered concerning the roles of AA and LO metabolites in the stimulation of neuronal IK by Ang II. For example, although our studies indicate that 12S-HETE stimulates neuronal IK and is a possible candidate for mediating the stimulatory effects of Ang II onIK, we cannot exclude the possibility that other LO metabolites (e.g., leukotrienes, 5-LO metabolites) are also involved. Furthermore, does AA directly modulate K+ channel activity?

The present results and our previous studies (Kang et al., 1994) demonstrate that inhibition of PP-2A blocks the stimulatory effects of Ang II, AA, and 12S-HETE on neuronalIK, while not altering baselineIK. The exact cellular locus at which PP-2A is involved is not known. However, the fact that Ang II-stimulated AA release (AT2 receptor-mediated) is not affected by inhibition of PP-2A suggests that this enzyme may be involved as a distal event in the intracellular pathway controllingIK. One possibility is that PP-2A is complexed or associated with the delayed-rectifier K+ channel (which underlies IK) in the neuronal membrane. Support from this idea comes from studies that demonstrated that BKCa channels from rat brain exist as part of a regulatory complex with PP-1 (Reinhart and Levitan, 1995) and that a PP-2A-sensitive regulatory site controls the gating of L-type Ca2+ channels in smooth muscle cells (Groschner et al., 1996). The exact locus of the involvement of PP-2A will only be determined by single-channel recordings. Because there is much evidence that the phosphorylation and dephosphorylation of channel proteins is extremely important in the regulation of ion channel activity (Levitan, 1994), another question that remains is whether PP-2A directly modulates the activity of the K+ channel(s) that underlie IK by dephosphorylation.

In summary, our data provide the first demonstration that an intracellular pathway that includes activation of PLA2 and generation of AA and LO metabolites of AA is important for the stimulation of neuronal IK by Ang II via AT2 receptors. Furthermore, our data suggest that the activation of PP-2A may be a distal event in this pathway. Interestingly, similar pathways have been proposed for calcium-dependent modulation of M (K+) current in sympathetic neurons (Yu, 1995) and for somatostatin-induced stimulation of BKCa in rat pituitary tumor cells (Duerson et al., 1996). Collectively, these findings may suggest that a common series of intracellular events (AA/LO metabolites/PP-2A) may be responsible for the modulation of different K+ currents in different cell types.

Footnotes

This work was supported by National Institutes of Health Grants NS19441, HL49130, and HL52189. We thank Jennifer Brock for typing this manuscript.

Correspondence should be addressed to Dr. Colin Sumners, Department of Physiology, University of Florida, Box 100274, 1600 Southwest Archer Road, Gainesville, FL 32610.

REFERENCES

- 1.Axelrod J, Burch RM, Jelsema CL. Receptor-mediated activation of phospholipase A2 via GTP-binding proteins: arachidonic acid and its metabolites as second messengers. Trends Neurosci. 1988;11:117–123. doi: 10.1016/0166-2236(88)90157-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Cook VI, Grove KL, McMenamin KM, Carter MR, Harding JW, Speth RC. The AT2 angiotensin receptor subtype predominates in the 19 day gestation fetal rat brain. Brain Res. 1991;560:334–336. doi: 10.1016/0006-8993(91)91254-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Dickerson CD, Weiss ER. The coupling of pertussis toxin-sensitive G proteins to phospholipase A2 and adenylyl cyclase in CHO cells expressing bovine rhodopsin. Exp Cell Res. 1995;216:46–50. doi: 10.1006/excr.1995.1006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Duerson K, White RE, Jiang F, Schonbrunn A, Armstrong DL. Somatostatin stimulates BKCa channels in rat pituitary tumor cells through lipoxygenase metabolites of arachidonic acid. Neuropharmacology. 1996;35:949–961. doi: 10.1016/0028-3908(96)00131-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Gelband CH, Zhu M, Lu D, Reagan LP, Fluharty SJ, Posner P, Raizada MK, Sumners C. Functional interactions between neuronal AT1 and AT2 receptors. Endocrinology. 1997;138:2195–2198. doi: 10.1210/endo.138.5.5236. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Groschner K, Schuhmann K, Mieskes G, Baumgartner W, Romanin C. A type 2A phosphatase-sensitive phosphorylation site controls modal gating of L-type Ca2+ channels in human vascular smooth-muscle cells. Biochem J. 1996;318:513–517. doi: 10.1042/bj3180513. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Gubitosi-Klug RA, Yu SP, Choi DW, Gross RW. Concomitant acceleration of the activation and inactivation kinetics of the human delayed rectifier K+ channel (Kv1.1) by Ca(2+)-independent phospholipase A2. J Biol Chem. 1995;270:2885–2888. doi: 10.1074/jbc.270.7.2885. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Hamill OP, Marty A, Neher E, Sakmann B, Sigworth BJ. Improved patch-clamp techniques for high resolution current recording from cells and cell-free membrane patches. Pflügers Arch. 1981;391:85–100. doi: 10.1007/BF00656997. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Hein L, Barsh GS, Pratt RE, Dzau VJ, Kobilka BK. Behavioural and cardiovascular effects of disrupting the angiotensin II type-2 receptor in mice. Nature. 1995;377:744–747. doi: 10.1038/377744a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Hohle S, Spitznagel H, Rascher W, Culman J, Unger T. Angiotensin AT1 receptor-mediated vasopressin release and drinking are potentiated by an AT2 receptor antagonist. Eur J Pharmacol. 1995;275:277–282. doi: 10.1016/0014-2999(95)00005-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Honkanen RE, Dukelow M, Zwiller J, Moore RE, Khatra BS, Boynton AL. Cyanobacterial nodularin is a potent inhibitor of type 1 and type 2A protein phosphatases. Mol Pharmacol. 1991;40:577–583. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Horiuchi M, Hayashida W, Kambe T, Yamada T, Dzau VJ. Angiotensin type 2 receptor dephosphorylates bcl-2 by activating mitogen-activated protein kinase phosphatase-1 and induces apoptosis. J Biol Chem. 1997;272:19022–19026. doi: 10.1074/jbc.272.30.19022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Huang X-C, Richards EM, Sumners C. Angiotensin II type 2 receptor-mediated stimulation of protein phosphatase 2A in rat hypothalamic/brainstem neuronal co-cultures. J Neurochem. 1995;65:2131–2137. doi: 10.1046/j.1471-4159.1995.65052131.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Huang X-C, Shenoy UV, Richards EM, Sumners C. Modulation of angiotensin II type 2 receptor mRNA in rat hypothalamus and brainstem neuronal cultures by growth factors. Mol Brain Res. 1997;47:229–236. doi: 10.1016/s0169-328x(97)00047-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Ichiki T, Labosky PA, Shiota C, Okuyama S, Imagawa Y, Fogo A, Miimura F, Ichikawa I, Hogan BL, Inagami T. Effects on blood pressure and exploratory behavior of mice lacking angiotensin II type 2 receptor. Nature. 1995;377:748–750. doi: 10.1038/377748a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Irvine RF. How is the level of free arachidonic acid controlled in mammalian cells? Biochem J. 1982;204:3–16. doi: 10.1042/bj2040003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Jacobs LS, Douglas JG. Angiotensin II type 2 receptor subtype mediates phospholipase A2 signaling in rabbit proximal tubular epithelial cells. Hypertension. 1996;28:663–668. doi: 10.1161/01.hyp.28.4.663. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Kang J, Sumners C, Posner P. Angiotensin II type 2 (AT2) receptor modulated changes in potassium currents in cultured neurons. Am J Physiol. 1993;265:C607–C616. doi: 10.1152/ajpcell.1993.265.3.C607. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Kang J, Posner P, Sumners C. Angiotensin II type 2 receptor stimulation of neuronal K+ currents involves an inhibitory GTP binding protein. Am J Physiol. 1994;267:C1389–C1397. doi: 10.1152/ajpcell.1994.267.5.C1389. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Kim D, Sladek CD, Aguado-Velasco C, Mathiasen JR. Arachidonic acid activation of a new family of K+ channels in cultured rat neuronal cells. J Physiol (Lond) 1995;484:643–660. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.1995.sp020693. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Laflamme L, de Gasparo M, Gallo JM, Payet MD, Gallo-Payet N. Angiotensin II induction of neurite outgrowth by AT2 receptors in NG108–15 cells. J Biol Chem. 1996;271:22729–22735. doi: 10.1074/jbc.271.37.22729. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Levitan IB. Modulation of ion channels by protein phosphorylation and dephosphorylation. Annu Rev Physiol. 1994;56:193–212. doi: 10.1146/annurev.ph.56.030194.001205. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Lokuta AJ, Cooper C, Gaa ST, Wang HE, Rogers TB. Angiotensin II stimulates the release of phospholipid-derived second messengers through multiple receptor subtypes in heart cells. J Biol Chem. 1994;269:4832–4838. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Meves H. Modulation of ion channels by arachidonic acid. Prog Neurobiol. 1994;43:175–186. doi: 10.1016/0301-0082(94)90012-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Millan M, Jacobowitz DM, Aguilera G, Catt KJ. Differential distribution of AT1 and AT2 angiotensin II receptor subtypes in the rat brain during development. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1992;88:11440–11444. doi: 10.1073/pnas.88.24.11440. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Mukoyama M, Nakajima M, Horiuchi M, Sasamura H, Pratt RE, Dzau VJ. Expression cloning of type 2 angiotensin II receptor reveals a unique class of seven transmembrane receptors. J Biol Chem. 1993;268:24539–24542. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Owada Y, Tominaga T, Yoshimoto T, Kondo H. Molecular cloning of rat cDNA for cytosolic phospholipase A2 and increased gene expression in the dentate gyrus following transient forebrain ischemia. Mol Brain Res. 1994;25:364–368. doi: 10.1016/0169-328x(94)90174-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Premkumar LS, Gage PW, Chung SH. Coupled potassium channels induced by arachidonic acid in cultured neurons. Proc R Soc Lond B Biol Sci. 1990;242:17–22. doi: 10.1098/rspb.1990.0097. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Pueyo ME, D’Diaye N, Michel JB. Angiotensin II-elicited signal transduction via AT1 receptors in endothelial cells. Br J Pharmacol. 1996;118:79–84. doi: 10.1111/j.1476-5381.1996.tb15369.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Rao GN, Lassegue B, Alexander RW, Griendling KK. Angiotensin II stimulates phosphorylation of high molecular mass cytosolic phospholipase A2 in vascular smooth muscle cells. Biochem J. 1994;299:197–201. doi: 10.1042/bj2990197. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Reinhart PH, Levitan IB. Kinase and phosphatase activities intimately associated with a reconstituted calcium-dependent potassium channel. J Neurosci. 1995;15:4572–4579. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.15-06-04572.1995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Schweitzer P, Madamba S, Champagnat J, Siggins GR. Somatostatin inhibition of hippocampal CA1 pyramidal neurons: mediation by arachidonic acid and its metabolites. J Neurosci. 1993;13:2033–2049. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.13-05-02033.1993. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Song K, Allen AM, Paxinos G, Mendelsohn FAO. Mapping of angiotensin II receptor subtypes heterogeneity in rat brain. J Comp Neurol. 1992;316:467–492. doi: 10.1002/cne.903160407. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Sumners C, Tang W, Zelezna B, Raizada MK. Angiotensin II receptor subtypes are coupled with distinct signal transduction mechanisms in neurons and astroglia from rat brain. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1991;88:7567–7571. doi: 10.1073/pnas.88.17.7567. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Sumners C, Raizada MK, Kang J, Lu D, Posner P. Receptor-mediated effects of angiotensin II in neurons. Front Neuroendocrinol. 1994;15:203–230. doi: 10.1006/frne.1994.1009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Sumners C, Zhu M, Gelband CH, Posner P. Angiotensin II type 1 receptor modulation of K+ and Ca2+ currents: intracellular mechanisms. Am J Physiol. 1996;271:C154–C163. doi: 10.1152/ajpcell.1996.271.1.C154. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Tsutsumi K, Saavedra JM. Differential development of angiotensin II receptor subtypes in the rat brain. Endocrinology. 1991;138:630–632. doi: 10.1210/endo-128-1-630. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Wakelam MJO, Currie S. The determination of phospholipase A2 activity in stimulated cells. In: Milligan G, editor. Signal transduction, a practical approach. IRL; Oxford: 1992. pp. 153–165. [Google Scholar]

- 39.Williams EJ, Furness J, Walsh FS, Doherty P. Characterization of the second messenger pathway underlying neurite outgrowth stimulated by FGF. Development. 1994;120:1685–1693. doi: 10.1242/dev.120.6.1685. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Yamada T, Horiuchi M, Dzau V. Angiotensin II type 2 mediates programmed cell death. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1996;93:156–160. doi: 10.1073/pnas.93.1.156. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Yu SP. Roles of arachidonic acid, lipoxygenases and phosphatases in calcium-dependent modulation of M-current in bullfrog sympathetic neurons. J Physiol (Lond) 1995;487:797–811. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.1995.sp020919. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Zhang J, Pratt RE. The AT2 receptor selectively associates with Gi(α)-2 and Gi(α)-3 in the rat fetus. J Biol Chem. 1996;271:15026–15031. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Zhu M, Neubig RR, Wade SM, Posner P, Gelband CH, Sumners C. Modulation of K+ and Ca2+ currents in cultured neurons by an angiotensin II type 1a receptor peptide. Am J Physiol. 1997;273:C1040–C1048. doi: 10.1152/ajpcell.1997.273.3.C1040. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Zona C, Palma E, Pellerin L, Avoli M. Arachidonic acid augments potassium currents in rat neocortical neurones. NeuroReport. 1993;4:359–362. doi: 10.1097/00001756-199304000-00004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]