Abstract

Perfusion of rat brain slices with low millimole CsCl elicits slow oscillations of ≤1 Hz in hippocampal CA1 pyramidal neurons. These oscillations are GABAA receptor-mediated hyperpolarizations that permit a coherent fire–pause pattern in a population of CA1 neurons. They can persist without the activation of ionotropic glutamate receptors but require adenosine-dependent inhibition of glutamate transmission. In response to external Cs+, multiple interneurons in the CA1 region display rhythmic discharges that correlate with the slow oscillations in CA1 pyramidal neurons. The interneuronal discharges arise spontaneously from the resting potential, and their rhythmicity is regulated by periodic, GABAA receptor-mediated hyperpolarizations. In addition, interneurons show periodic partial spikes and neurobiotin coupling, and applications of known gap junctional uncouplers interrupt the Cs+-induced slow rhythm in both CA1 pyramidal neurons and interneurons. We propose that these slow oscillations originate from a GABAergic interneuronal network that interacts through reciprocal inhibition and possibly gap junctional connection.

Keywords: adenosine, brain slices, GABA, gap junctions, interneurons, oscillations

Oscillations in brain electrical activities, defined as regularly occurring waveforms of similar shape and duration, appear in distinct behavioral states such as perception, movement initiation, memory, and sleep. Overall, fast rhythms of ≥15 Hz occur in arousal or active states, whereas slow oscillations of ≤1–4 Hz dominate during deep sleep (Niedermeyer, 1993; Steriade, 1993) or some epileptiform activities (Reiher et al., 1989; Gambardella et al., 1995; Normand et al., 1995). Alterations in these oscillations are associated with or result from substantial changes in brain structure and function, and detection of these abnormalities by electroencephalography (EEG) is a widely used diagnostic approach in clinical practice. How do such oscillations arise? Research into brain rhythmic activities has focused on two major issues: (1) the cellular or neurochemical basis of neuronal rhythmicity and (2) the neural assemblies by which rhythmic activities propagate and synchronize over a large scale.

Slow brain oscillations associated with deep sleep have been studied intensively by simultaneous intracellular and EEG recordings in vivo (Steriade et al., 1993a,b; Contreras et al., 1996a; Amzica and Steriade, 1997). These studies demonstrate that the slow EEG oscillations of ≤1 Hz are of neocortical origin and coordinated globally via thalamocortical circuitry. The intracellular responses of cortical neurons manifest a coherent hyperpolarization during each EEG cycle, thought to be mediated via a dysfacilitation mechanism (Contreras and Steriade, 1995; Contreras et al., 1996b).

The activity mediated by GABAergic synapses is the major inhibitory process in the CNS. GABAergic interneurons are known to have extensive axonal arborization by which synchronized inhibition can be imposed onto a population of principal neurons in the local assembly (Buhl et al., 1994; Cobb et al., 1995). Recent studies suggest that GABAergic interneurons are heavily interconnected as distinct networks (Gulyás et al., 1996) that are capable of generating coherent rhythms (Buzsáki and Chrobak, 1995; Freund and Buzsáki, 1996). The γ oscillations (20–70 Hz) observed in hippocampal slices present a good example of such inhibitory rhythms (Whittington et al., 1995; Jefferys et al., 1996). The γ oscillations are GABAA receptor-mediated synaptic events, resulting from the excitation of GABAergic interneurons by metabotropic glutamate receptors. Their frequencies are directly influenced by the decay kinetics of GABAA-mediated synaptic currents, supporting the concept that reciprocally inhibited networks can produce synchronized activities (Wang and Rinzel, 1992; Traub et al., 1996;Wang and Buzsáki, 1996). However, to date it has not been shown that GABAergic interneuronal networks allow a slow oscillatory inhibition of ≤5 Hz to occur regularly and persistently.

We report here a slow (≤1 Hz) oscillatory inhibition in hippocampal CA1 pyramidal neurons after exposure of rat brain slices to low millimole CsCl. These slow oscillations manifest coherent hyperpolarizations attributable to activation of GABAAreceptors, and they can persist without activation of ionotropic glutamate receptors but require adenosine-dependent inhibition of glutamate transmission. In response to Cs+, multiple interneurons in the CA1 region show rhythmic discharges that correlate with slow oscillations in CA1 pyramidal neurons. We provide convergent evidence suggesting that the Cs+-induced slow oscillations arise from the network activity of GABAergic interneurons, via mechanisms of reciprocal inhibition and possibly gap junctional communication.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Brain slice preparation and electrophysiological recordings have been described previously (Zhang et al., 1991, 1993, 1994, 1998). Briefly, male Wistar rats (13- to 52-d-old) were anesthetized with halothane and decapitated. The brain was quickly dissected out and maintained in an ice-cold artificial CSF (ACSF) for 5–15 min. The brain was then mounted on an aluminum block and transverse sections of 400–450 μm were obtained using a vibratome. After sectioning, slices were maintained in oxygenated ACSF at room temperature (22–23°C) for at least 1 hr before recording. The composition of the ACSF was (in mm): NaCl 125, KCl 2.5, NaH2PO4 1.25, CaCl2 2, MgSO4 1.8, NaHCO3 26, and glucose 10. The pH of the ACSF was 7.4 when aerated with 5% CO2–95% O2.

Patch pipettes were pulled from borosilicate thin-wall glass tubes (TW150F-4, World Precision Instruments, Sarasota, FL) using a two-stage Narishige puller (Tokyo, Japan). The composition of the patch pipette solution was 150 mm potassium gluconate, 5 mmHEPES, and 0.1 mm Na-EGTA. In some experiments, half of the potassium gluconate was replaced with KCl to raise intracellular Cl− in the recorded neurons. The patch pipette solutions had a pH of 7.25 adjusted with KOH and an osmolarity of 280 ± 10 mOsm. When filled with these solutions, the patch pipette had a tip resistance of 4–5 MΩ. Extracellular recordings were performed using patch pipettes filled with 150 mmNaCl.

Recordings were performed in a fully submerged chamber at 32–33°C, and warm air of 5% CO2–95% O2 was also applied over the perfusate to ensure an oxygenated local environment. IPSCs in hippocampal CA1 neurons were evoked by stimulating Schaffer collateral afferents using a bipolar tungsten electrode. Cortical IPSCs were evoked focally using a NaCl-filled glass pipette.

Interneurons of the hippocampal CA1 region were identified by infrared imaging and/or by their characteristic electrophysiological properties, which have been described previously (Kawaguchi and Hama, 1987;Lacaille et al., 1987; Lacaille and Schwartzkroin, 1988; Maccaferri and McBain, 1996), i.e., fast spikes, large post-spike hyperpolarization (AHP), and little firing adaptation during repetitive discharges.

Electrical signals were recorded using an Axoclamp (2A) and/or Axopatch patch amplifier (200B, Axon Instruments, Foster City, CA), with the low-pass filter setting at 1–3 kHz or 5 kHz, respectively. The series resistance compensation was near 80% when using the Axopatch amplifier in the voltage-clamp mode. Data were stored and analyzed using the PCLAMP software (version 6.3, Axon Instruments) via a 12-bit D/A interface (Digidata 1200, Axon Instruments), or they were stored on a digitized data recorder (VR-10A/B, Introtech, New York, NY).

For examining dye coupling, interneurons were whole-cell-dialyzed with a patch pipette solution containing 0.5% neurobiotin (Vector Labs, Burlington, ON, Canada), and the concentration of potassium gluconate in the patch pipette solution was reduced to 120 mm to balance osmolarity. One interneuron was recorded per slice. At the end of the recording, the patch pipette was immediately withdrawn from the slice. The slice was kept in the recording chamber and perfused for another 30–40 min to wash out any leaked neurobiotin and to allow intracellular distribution of neurobiotin in the recorded and coupled cells. The slice was then fixed overnight in 4% paraformaldehyde in 0.1 m phosphate buffer and resectioned to 100 μm. The sections were treated with an avidin–biotin–peroxidase complex (ABC Kit, Vector) and rinsed and reacted with diaminobenzidine tetrahydrochloride and H2O2. The sections were mounted on glass slides, and photographs were taken under a 10× or 40× objective. A Zeiss camera lucida drawing device was used to trace the stained neuronal processes.

Glutamate receptor antagonists and the adenosine receptor antagonist 8-cyclopentyl-1,3-dipropylxanthin (DCPCX) were obtained from Tocris Cookson (Ballwin, MO), and other drugs were purchased from Sigma (St. Louis, MO) or Fluka (New York, NY). Chemicals for making patch pipette solutions were obtained from Fluka.

RESULTS

Coherent oscillations in hippocampal and cortical principal neurons of rat brain slices

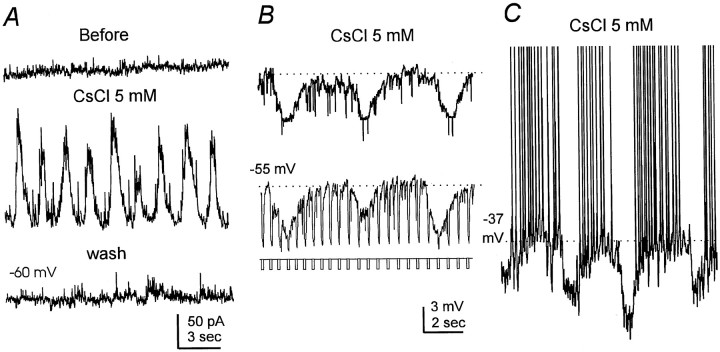

After perfusion of slices with 3–5 mm CsCl for ≥4 min, CA1 pyramidal neurons displayed oscillatory outward currents when voltage-clamped at −50 to −55 mV. These oscillatory events slowly rose and fell in 1–2 sec, with amplitudes of 50–200 pA (Fig.1). They were fully reversible after washing but could persist for >60 min in Cs+, with a mean frequency of 1.09 ± 0.05 Hz or 0.53 ± 0.02 Hz after application of 5 mm CsCl for 6–8 or 15–20 min, respectively (32–33°C; n = 22, mean ± SEM) (Table 1). In CA1 neurons recorded in the current-clamp mode at resting membrane potentials of near −60 mV, a similar application of CsCl induced periodic hyperpolarizations during which the membrane resistance was decreased by 42 ± 5% (n = 5) (Fig. 1B). These hyperpolarizations became larger at more positive potentials and effectively inhibited the tonic discharges induced by depolarizing DC current, yielding a regular fire–pause pattern (Figs. 1C,2C) that was not seen in standard recording conditions in hippocampal pyramidal neurons (Zhang et al., 1994). The Cs+-induced oscillations with similar frequencies were also observed in principal neurons of the hippocampal CA3 region, dentate gyrus, or layers IV–V of the parietal cortex (Table 1), suggesting a common phenomenon in hippocampal and cortical neurons of brain slices.

Fig. 1.

Cs+-induced slow oscillations recorded from a CA1 pyramidal neuron. A, The CA1 neuron was voltage-clamped at −60 mV, and records were collected before (top), during perfusion of 5 mm CsCl for 7 min (middle), and after washing (bottom).B, The same neuron was then recorded in the current-clamp mode at approximately −55 mV (dotted line) after re-exposure to 5 mm CsCl. Constant-current pulses (−100 pA, 200 msec) were passed through the recording pipette to measure membrane resistance. Note the decreased resistance during the prolonged hyperpolarizations. C, The neuron was depolarized to approximately −37 mV (dotted line) by intracellular injection of positive DC current. Note the inhibited spiking during the hyperpolarizations.

Table 1.

Cs+-induced oscillations in principal neurons of hippocampus and neocortex

| Neuronal locations | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Hippocampal CA1 region | Hippocampal CA3 region | Dentate gyrus | Parietal cortex | |

| Oscillation frequency | 0.53 ± 0.02 | 0.61 ± 0.14 | 0.51 ± 0.07 | 0.46 ± 0.06 |

| (Hz) | (n = 22) | (n = 5) | (n = 6) | (n = 12) |

Fig. 2.

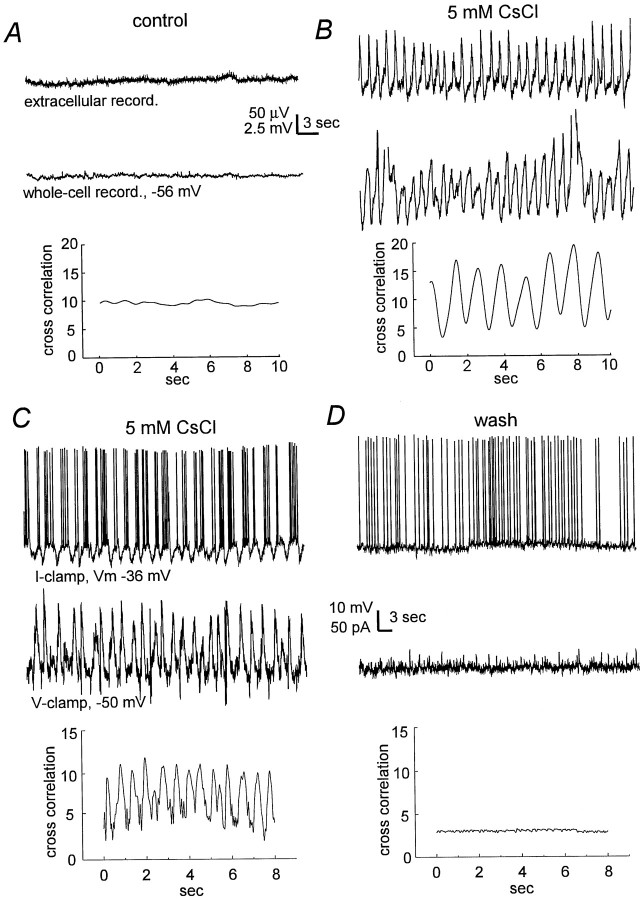

Coherence of Cs+-induced slow oscillations. A, B, CA1 field potentials (extracellular record., top) and voltage responses from a CA1 pyramidal neuron (whole-cell record., bottom) were monitored simultaneously. Records were collected before (A) and after (B) application of 5 mm CsCl for 8 min. The tips of the two recording pipettes were separated by ∼100 μm. C, D, Simultaneous whole-cell recordings were made from two CA1 pyramidal neurons 250 μm apart. One neuron (top) was monitored in the current-clamp mode, and its membrane potential was kept at −36 mV by intracellular injection of DC current to examine firing patterns. Another CA1 neuron (bottom) was voltage-clamped at −50 mV, showing periodic outward currents. The records were collected after application of 5 mm CsCl for 7 min (C) or after washing (D). The corresponding cross-correlation plots are shown below.

During prolonged exposure to external Cs+, hippocampal principal neurons and cortical neurons rarely discharged spontaneously from the resting potential. This is in contrast to the previous study in which Cs+ perfusion induces bursting discharges in CA1 pyramidal neurons recorded at the resting potential (Janigro et al., 1997). The discrepancy between our data and the previous report (Janigro et al., 1997) may be partly attributable to the difference in recording temperature, i.e., 33°C in most of our experiments and 22–25°C in the previous study. If external Cs+ promotes the activity of Na-K ATPase as shown previously in cardiac tissue (Sohn and Vassalle, 1995), the Cs+ enhancement of the enzymatic activity would be greater at 33°C than at 22–25°C, thus helping to maintain ionic homeostasis.

To determine whether the Cs+-induced oscillations occurred in a population of neurons, we monitored field potentials by placing an extracellular recording electrode near (≤200 μm) the whole-cell recording site. Rhythmic field potentials of 100–200 μV were recorded in the hippocampal CA1 region (n = 4) after exposure to 5 mm CsCl, and their frequencies were identical to those oscillations recorded simultaneously from the nearby CA1 neuron (Fig. 2A,B). These field oscillations remained unchanged when the nearby neuron was hyperpolarized or depolarized to fire by intracellular DC current, implying that the activity was generated from a group of neurons. We also did simultaneous whole-cell recordings from two CA1 neurons located 100–450 μm apart, to assess the phase relation during their slow oscillations. Stable recordings of the Cs+-induced oscillations were achieved in 16 pairs of CA1 neurons for at least 10 min, and the peak-to-peak phase lag was 142 ± 4 msec for the oscillatory events measured from corresponding neurons (Fig.2C,D). Given that individual oscillatory events last 1–2 sec, this small phase-lag would allow spatially separated neurons to be in phase in ≥90% of time during the slow oscillations. The high temporal coherence observed from paired CA1 neurons, together with the coherent field oscillations, suggests a synchronized, oscillatory inhibition.

The slow oscillations are temperature- but not age-dependent

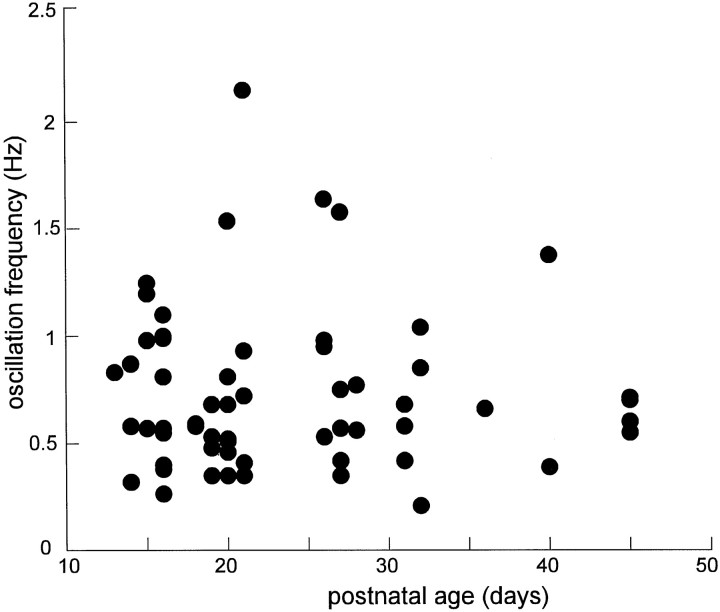

Different from the spontaneous activity observed in neonatal hippocampus (Cherubini et al., 1991), the Cs+-induced oscillations were consistently observed in slices obtained from 13- to 45-d-old rats. Within this age range, there was no clear relation between the oscillation frequency and postnatal age of individual CA1 neurons examined (n = 52) (Fig. 3). The oscillation frequency, however, increased with the recording temperature. In three groups of CA1 neurons (18- to 35-d-old) recorded at 22–23°C (n= 8), 32–33°C (n = 22), or 36–37°C (n = 7), the mean frequency was 0.38 ± 0.06, 1.09 ± 0.05, or 1.58 ± 0.09 Hz, respectively, as measured after the exposure to 5 mm CsCl for 5–10 min. These observations suggest that the Cs+-induced slow oscillations originate from developing or developed local circuitry, because maturation of GABAergic transmission and voltage-gated K+ currents occur by postnatal day 30 in rat hippocampal CA1 neurons (Zhang et al., 1991; Spigelman et al., 1992).

Fig. 3.

The oscillation frequency is independent of the postnatal age of CA1 neurons examined. Data were collected from 52 CA1 pyramidal neurons in slices obtained from rats aged 13–45 d. The oscillations were measured after application of 5 mm CsCl for 7–10 min. Each data point represents the mean frequency of a neuron calculated from a recording period of 2–3 min.

In parallel to the generation of slow oscillations, CA1 neurons displayed an outward shift in holding currents (by 50–100 pA) and a decrease in input conductance (by 38 ± 7.8%, n = 22) after exposure to 3–5 mm CsCl. These changes were consistent with a blockade of the Cs+-sensitive inward rectifier current Ih orIQ, as described previously (Halliwell and Adams, 1982; Maccaferri and McBain, 1996; Janigro et al., 1997). Slow oscillations were not observed in CA1 neurons after perfusion of slices with a high-K+ ACSF for≥10 min (6.5 mm, n = 6). We did not raise external K+ to ≥8 mm because such treatment leads to depolarizing GABAA responses attributable to a positive shift in Cl− reversal potential (Zhang et al., 1991) and induces epileptiform discharges in CA1 pyramidal neurons (McBain, 1994).

Cs+-induced slow oscillations were not mimicked in CA1 pyramidal neurons after perfusion of slices with 1 mmBaCl2 (n = 4), 2 mm4-aminopyridine (n = 5), or 5 mmtetraethylammonium chloride (n = 6). Spontaneous IPSCs were seen in these neurons in the presence of 4-aminopyridine or tetraethylammonium, but these IPSCs were briefer (≤500 msec), less frequent (0.1–0.3 Hz), and irregular compared with the Cs+-induced oscillatory events (cf. Avoli et al., 1996). Thus, although a moderate rise of external K+and/or blockade of depolarization-activated potassium conductances might have occurred after exposure of slices to Cs+, they appear not to be the primary mechanisms in generating the slow oscillatory inhibition.

We also examined the effects of ZD7288, a cation channel blocker reported to block hippocampal Ih (Maccaferri and McBain, 1996). At concentrations (50 and 100 μm) sufficient for blocking Ih, ZD7288 failed to induce oscillations but suppressed evoked IPSCs in five CA1 neurons examined. Irreversible suppression of CA1 synaptic responses and action potentials was also observed after application of 10 μmZD7288 (n = 3), suggesting an inhibition of transmitter release by this agent in addition to its blocking action ofIh.

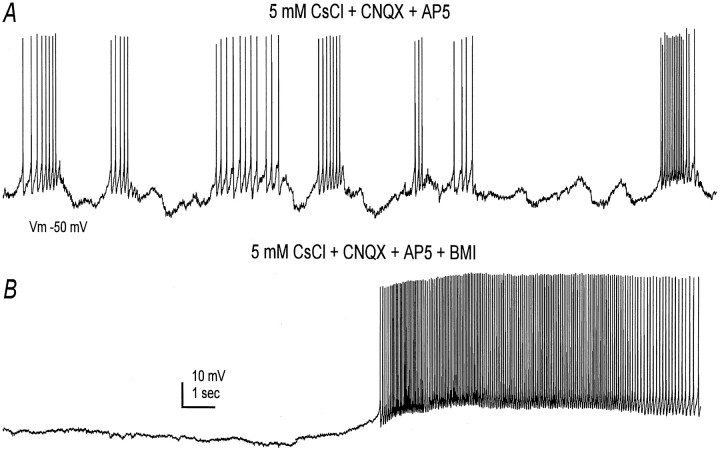

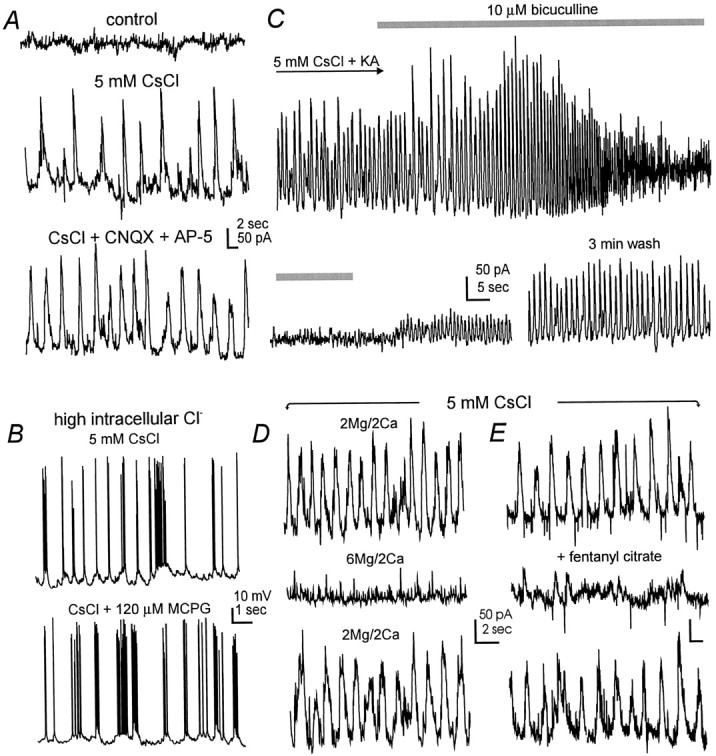

The slow oscillations are GABAA-mediated synaptic events

In both CA1 and cortical neurons (n = 26 and 4), the Cs+-induced oscillations persisted and often became more regular after blocking ionotropic glutamate receptors with CNQX (20 μm) and D-AP5 (50 μm), or 1.5 mm kynurenic acid (Fig.4A). These oscillations showed no substantial alteration after exposure of CA1 neurons to 120 μm (S)-α-methy-4-carboxyphenylglycine (MCPG) or (RS)-α-methyserine-O-phosphate (MSOP) (n = 5 or 4) (Fig. 4B), which antagonizes the group I/II or III metabotropic glutamate receptors, respectively (Conn and Pin, 1997). In contrast, these oscillations in CA1 neurons (n = 10) and cortical neurons (n = 3) were abolished by perfusion of slices with 10 μm bicuculline methiodide, a GABAAreceptor antagonist (Fig. 4C), but they persisted, although they became slower and less regular, in the presence of 120 μm phaclofen, a GABAB receptor antagonist (n = 5, CA1 neurons). In CA1 neurons recorded in the current-clamp mode, the Cs+-induced rhythmic hyperpolarizations reversed at −72 to −80 mV (n = 5), close to the Cl− equilibrium potential predicted under our recording conditions (cf. Zhang et al., 1991). Moreover, when CA1 neurons (n = 9) were recorded with a high-Cl− patch pipette solution (see Materials and Methods), the application of Cs+ induced only rhythmic depolarizations/discharges (Fig. 4B) that were also blocked by 10 μm bicuculline. On the basis of these pharmacological and ionic properties, we conclude that the Cs+-induced slow oscillations are mediated by the GABAA receptor-gated, Cl−-dependent ionic conductances.

Fig. 4.

GABAA receptor-mediated slow oscillations. A, Voltage-clamp recordings were made from a cortical neuron at the holding potential of −60 mV. The records were collected before (top) and after application of 5 mm CsCl for 10 min (middle) and CsCl plus ionotropic glutamate receptor antagonists (bottom) (20 μm CNQX and 50 μm AP5). B, Current-clamp records were collected from a CA1 pyramidal neuron at approximately −55 mV. The neuron was dialyzed with a patch pipette solution containing 75 mm KCl and 75 mmpotassium gluconate. Note the rhythmic depolarizations and discharges in CsCl (top) and their persistence in the presence of the group I/II metabotropic glutamate receptor antagonist MCPG (bottom). C, Continuous voltage-clamp records were collected from a CA1 neuron at the holding potential of −50 mV. CsCl (5 mm) and kynurenic acid (1.5 mm, a general ionotropic glutamate receptor antagonist) were applied throughout the recording period. The time period for the application of bicuculline methiodide (10 μm) was indicated by the shaded bars. Note the early enhancement of the oscillatory events by bicuculline before their full blockade was achieved. D, E, Voltage-clamp records were collected from two CA1 neurons in the presence of 5 mmCsCl. Note that the oscillatory events were suppressed by high external Mg2+ (D) or 1 μmfentanyl citrate, a μ opioid agonist.

The Cs+-induced slow oscillations were abolished by 0.5 μm tetrodotoxin in six CA1 neurons and three cortical neurons examined. They were attenuated by elevating external Mg2+ from 2 to 6 mm and keeping external Ca2+ constant at 2 mm (five CA1 neurons) (Fig. 4D), suggesting their dependence on evoked synaptic transmission. Moreover, these oscillations were reversibly suppressed after exposure of CA1 neurons to 1 μm fentanyl citrate (n = 5) (Fig. 4E), a μ opioid receptor analog that directly inhibits GABAergic interneurons and decreases GABA release (Zieglgänsberger et al., 1979; Nicoll et al., 1980; Madison and Nicoll, 1989; Cohen et al., 1992) (also see below). These observations, together with the persistence of CA1 oscillations in the presence of glutamate receptor antagonists as mentioned above, suggest a synaptically driven, GABAAreceptor-mediated oscillatory behavior, likely originating from the intrinsic rhythmicity of GABAergic interneuronal networks.

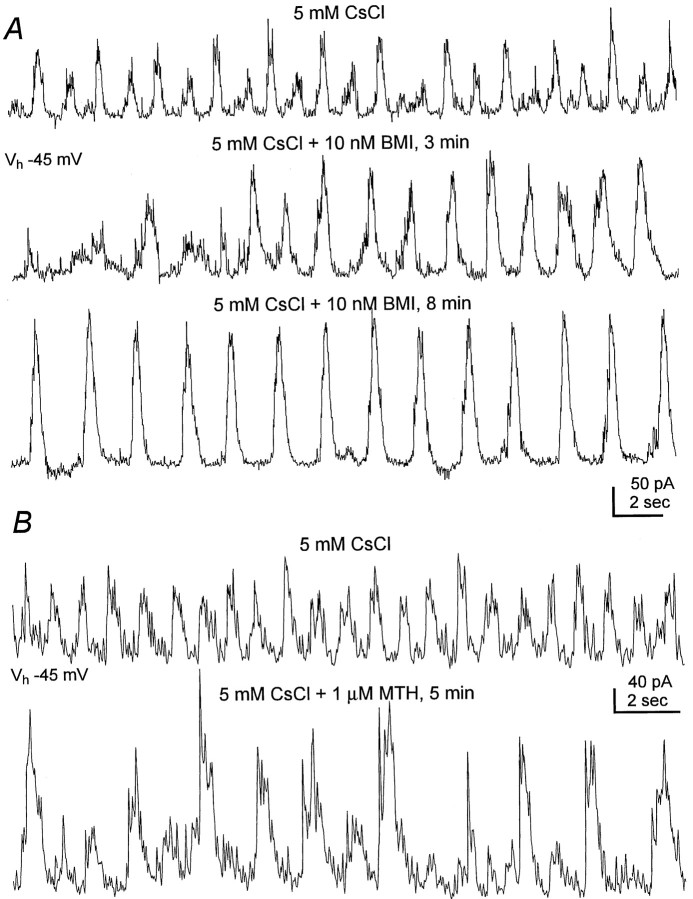

During the application of 10 μm bicuculline, the slow oscillations often showed an initial enhancement before a full blockade was achieved (Fig. 4C). In an attempt to reveal the enhancement without substantial reduction of GABAAconductances in CA1 pyramidal neurons, we examined the effect of 10 nm bicuculline on the Cs+-induced oscillations in CA1 neurons. CA1 oscillations became larger in amplitude (by 20–50%, n = 4) and more regular in waveform in the presence of low nanomole bicuculline, and these changes were sustained throughout the bicuculline application for up to 10 min (Fig. 5A). We also examined the effect of methohexital, an ultrashort-lasting barbiturate anesthetic, on the Cs+-induced oscillations in CA1 neurons. We have shown recently that methohexital enhances GABAergic responses both presynaptically and postsynaptically but does not affect fast glutamate transmission (Zhang et al., 1998). Exposure of CA1 neurons (n = 3) to 1 μm methohexital made the oscillations larger and slower, with increased background synaptic activities (Fig. 5B). The above changes cannot be explained solely by bicuculline blockade or methohexital potentiation of GABAA-gated conductances in CA1 pyramidal neurons. We speculate that at such low concentrations, these two agents may preferentially act on GABAA receptors of interneurons, affecting the dynamics of reciprocal inhibition among interconnected interneurons and therefore altering the oscillations that appeared in CA1 pyramidal neurons.

Fig. 5.

Enhancement of Cs+-induced oscillations by 10 nm bicuculline. A, Voltage-clamp records were collected from a CA1 neuron at the holding potential of −45 mV. The record at top was collected after application of 5 mm CsCl for about 10 min; the records in the middle and bottom were collected 3 and 8 min later after 10 nm bicuculline methiodide (BMI) was added to the perfusate. Note the enhanced oscillations with low background activity in the presence of bicuculline. B, Records were collected from another CA1 neuron, after perfusion of 5 mm CsCl alone for 7 min (top), and after 1 μm methohexital (MTH) was added to the perfusate for 3 min. Note the slowed oscillations in methohexital.

In parallel to Cs+-induced slow oscillations, IPSCs evoked by afferent stimulation (see Materials and Methods) were prolonged in both cortical (n = 4) and CA1 pyramidal neurons (n = 22). The half-decay time of CA1 IPSCs was increased from 64.1 ± 5.6 msec in control to 186.2 ± 16.7 msec after exposure to 5 mm Cs+ for ≥10 min (p < 0.001).

Cs+-induced rhythmic discharges in interneurons

To monitor the firing pattern of GABAergic interneurons, we recorded individual interneurons in hippocampal CA1 subfields, including oriens/alveus (n = 25), striatum radium (n = 9), lacunosum moleculare (n = 5), and stratum pyramidale (n = 5). These interneurons were identified by infrared imaging and/or by their characteristic electrophysiological properties, which have been described previously, i.e., fast spikes, large post-spike hyperpolarization, and little firing adaptation during repetitive discharges (Kawaguchi and Hama, 1987, 1988; Lacaille et al., 1987; Lacaille and Schwartzkroin, 1988;Morin et al., 1996). Application of 5 mm CsCl caused an increase in membrane resistance (by 42 ± 11% from the baseline control of 96 ± 11 MΩ, n = 10) and a decrease in the “sag” voltage response induced by negative current pulses, consistent with previous reports (DiFrancesco, 1982; Halliwell and Adams, 1982; Maccaferri and McBain, 1996; Janigro et al., 1997). When examined in the voltage-clamp mode and in the presence of 1 μm tetrodotoxin, application of 5 mm CsCl abolished the inward relaxation current (Ih) activated by negative voltage pulses, without substantial attenuation of outward currents activated by large depolarizing pulses (n = 3).

In response to external Cs+, approximately half of the recorded CA1 interneurons at oriens/alveus, stratum radiatum, or lacunosome moleculare, but not those in stratum pyramidale, displayed rhythmic discharges from the resting membrane potential, with firing durations of 0.5–1 sec and occurrence frequencies of ∼0.5 Hz (Figs.6-11, Table2). These discharges persisted in the presence of 20 μm CNQX and 50 μm D-AP5, or 1.5 mm kynurenic acid (n = 10) (Figs.6-8), but were suppressed or abolished by 1 μm fentanyl citrate (n = 3) or 0.5 μm tetrodotoxin (n = 4). These electrophysiological and pharmacological properties were comparable to Cs+-induced oscillations observed from CA1 pyramidal neurons.

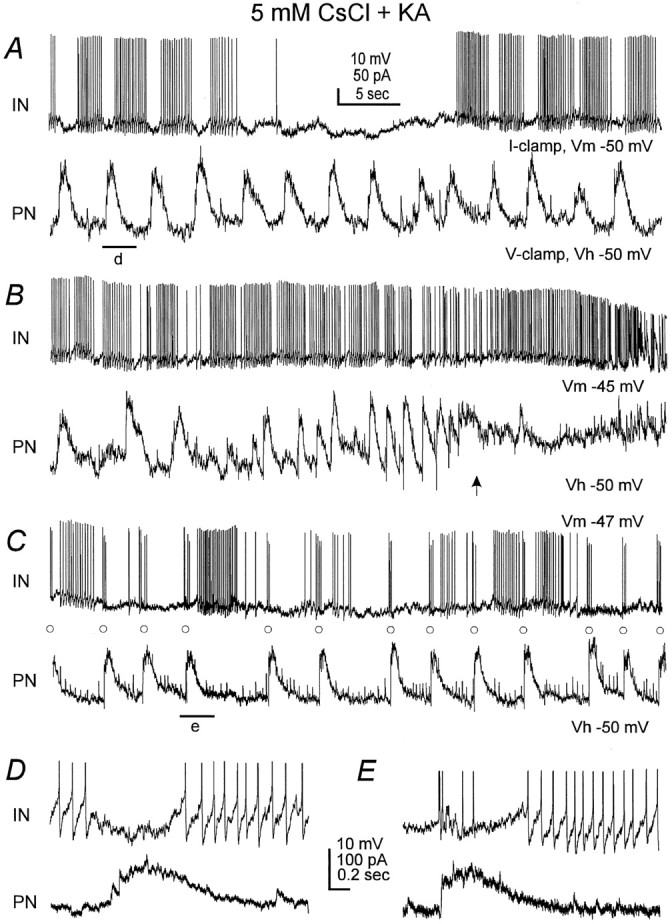

Fig. 6.

Bicuculline blocked interneuronal hyperpolarization and rhythmic discharges. Current-clamp records were collected from an interneuron at CA1 oriens/alveus. A, Responses were recorded after perfusion of 5 mm CsCl for 12 min and in the presence of 20 μm CNQX and 50 μm AP5. Note the slow hyperpolarizations separating discharges and occurring spontaneously without discharges.B, Responses were recorded 5 min after 10 μm bicuculline methiodide (BMI) was added to the perfusate. Note the abolished hyperpolarizations and the high-frequency discharges.

Fig. 7.

Coherent activities between an interneuron and a CA1 pyramidal neuron. Dual recordings were made from an oriens/alveus interneuron (IN, top) and a CA1 pyramidal neuron (PN, bottom) that were ∼200 μm apart. The interneuron was monitored in the current-clamp mode at the resting potential near −50 mV. The CA1 neuron was voltage-clamped at −50 mV. The slice was perfused with 5 mm CsCl and 1.5 mm kynurenic acid (KA). A, Records were collected after CsCl perfusion for 14 min. Note the temporal coherence of hyperpolarizing phases in both cells.B, Records were collected 4 min later when the slow rhythm in both cells was temporally lost. Note that high-frequency discharges in the interneuron concurred with the outward shift in the holding current and tonic activities in the CA1 neuron (arrow). C, Record collected 4 min later when the slow rhythm returned. Note that some interneuronal spikes (○) were followed closely by outward currents in the CA1 neuron.D, E, Records at fast sweep showing the period denoted by a filled bar in A andC, respectively. Note in E that the CA1 outward current showed a rapid onset and immediately followed the corresponding interneuronal spike.

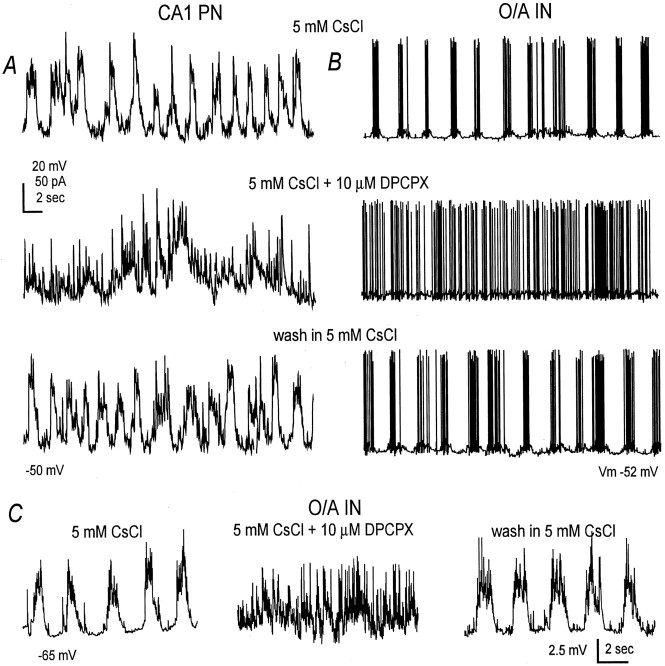

Fig. 8.

Blockade of adenosine A1 receptors interrupted the slow oscillations. A, B, A CA1 pyramidal neuron and an oriens/alveus interneuron were recorded in the voltage- or current-clamp mode in separate experiments. CsCl (5 mm) was applied throughout the recording period. Responses were collected before, at the end of application of DPCPX (an adenosine A1 receptor antagonist), and after washing.C, The same interneuron was hyperpolarized by intracellular injection of negative current to show subthreshold oscillations. Note the tonic activity when the interneuron was re-exposed to DPCPX (middle).

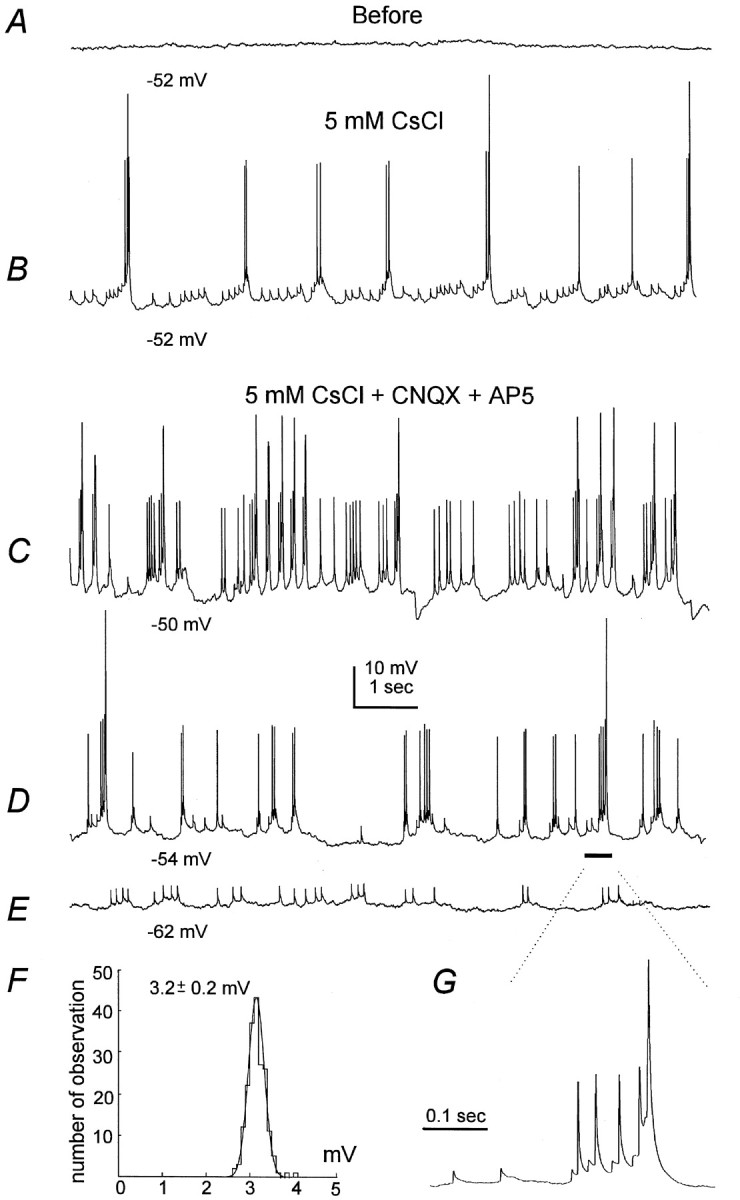

Fig. 9.

Interneuronal partial spikes. All records were collected from a stratum radiatum interneuron in the current-clamp mode. A, Baseline control showing no spontaneous activity at the resting potential near −52 mV. B, Responses recorded after perfusion of 5 mm CsCl for 7 min, showing spontaneous spikes of different amplitudes and small partial spikes. C, The record was collected ∼6 min later, and 20 μm CNQX and 50 μm AP5 were added to the perfusate for 4 min. D, E, The interneuron was hyperpolarized to −54 or −62 mV by intracellular injection of negative DC current. Note the prominent low-amplitude and partial spikes. F, Histogram showing amplitude distribution of partial spikes as illustrated in E. Data collected from a 2 min recording period were included in the analysis, and Simplex least squares fitting was computed using Pclamp software. The mean amplitude of partial spikes was 3.2 ± 0.2 mV, calculated from 265 events at membrane potential of −62 to −63 mV.G, Fast sweep showing partial, low-amplitude, and full-size spikes.

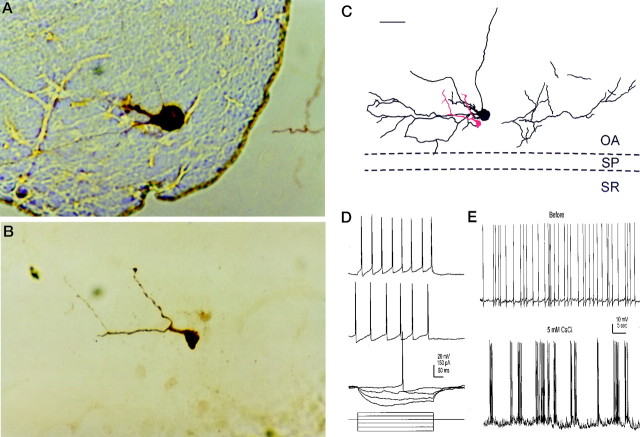

Fig. 10.

Neurobiotin dye couplings in CA1 interneurons.A, B, Photos were taken under a 40× objective from two adjacent sections (100 μm thickness) that were processed from a 400 μm fixed slice (see Materials and Methods). Only the interneuron shown in A was whole-cell dialyzed with 0.5% neurobiotin. Scale bar, 50 μm. C, The stained cells were drawn using a Zeiss Camera Lucida device. Black traces represent drawings taken from the section contained in the soma of the recorded interneuron, and red tracesmark the signals from the adjacent section. OA, Oriens/alveus; SP, stratum pyramidale; SR, stratum radiatum. D,I–V responses of the recorded interneuron in control. Square current pulses of −150 to 100 pA were injected intracellularly (bottom), and the corresponding voltage responses and discharges are illustrated above.E, Discharges of the same interneuron recorded before and after the application of 5 mm CsCl. The membrane potentials were −52 mV in C and E.

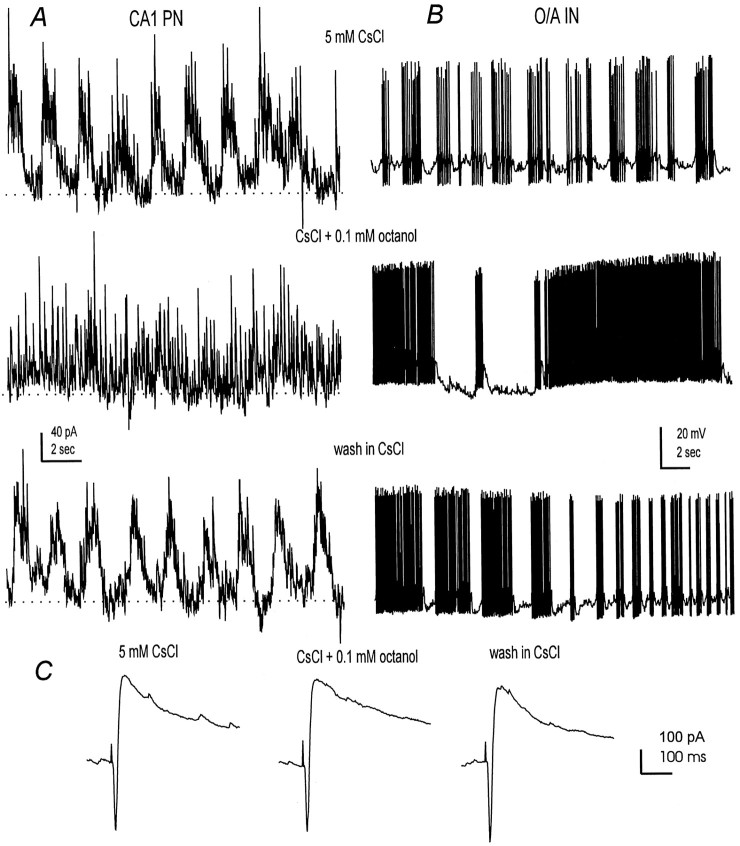

Fig. 11.

Interruption of the slow oscillations by octanol.A, B, A CA1 pyramidal neuron and an oriens/alveus interneuron were recorded in the voltage- or current-clamp mode in separate experiments. CsCl of 5 mmwas applied throughout the recording period. Responses were collected before, at the end of octonal application (0.1 mm, 2 min), and after washing. Note the tonic activity observed from both cells in the presence of octanol. C, Evoked EPSCs–IPSCs were recorded from another CA1 neuron before, during, and after the octanol application.

Table 2.

Cs+-induced rhythmic discharges observed from hippocampal CA1 interneurons

| O/A | SR | LM | SP | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Fraction of rhythmically discharging interneurons | 14/25 | 5/9 | 3/5 | 0/5 |

| Resting membrane potential (mV) | −54.1 ± 1.3 | −50.3 ± 2.6 | −50.7 ± 8.4 | −53.2 ± 3.5 |

| Frequency of rhythmic discharges (Hz) | 0.52 ± 0.06 | 0.48 ± 0.17 | 0.51 ± 0.08 |

All measurements were collected after Cs+ perfusion for 8–10 min at 33°C. O/A, Oriens/alveus; SR, striatum radiatum; LM, lacunosom moleculare; SP, stratum pyramidale. Perfusion of slices with 5 mm Cs+ induced no spontaneous discharges in the SP interneurons that were examined.

A close examination of voltage trajectories underlying the Cs+-induced rhythmic discharges in interneurons revealed periodic hyperpolarizations, which halted tonic spikes and allowed the fire–pause cycle to occur continuously (Figs.6A, 7A,8B). These hyperpolarizations were clearly recognizable when rhythmic discharges ceased randomly (Fig. 6A) or when they were stopped by a few millivolts of hyperpolarization caused by intracellular injection of negative DC current (not shown), but they were not seen in control recordings in the absence of external Cs+. Measured in the presence of CNQX and AP5 or kynurenic acid, these interneuronal hyperpolarizations had varied amplitudes of 1.5–4.0 mV and occurred every 1–2 sec, with a mean duration of 1.02 ± 0.11 sec (n = 7). These slow hyperpolarizations did not match the waveform of IPSPs evoked by afferent stimulation but were comparable to Cs+-induced oscillations seen in CA1 pyramidal neurons (Fig. 1B). Applications of 5–10 μm bicuculline abolished these hyperpolarizations and the associated rhythmic discharges (n = 4) (Fig.6B), producing high-frequency firing without a clear pattern. Collectively, these results suggest that the Cs+-induced, GABAA-gated hyperpolarizations in interneurons were likely caused by reciprocal innervations with summated IPSPs from interconnected interneurons (Freund and Buzsáki, 1996; Gulyás et al., 1996).

To examine the temporal relation between interneuronal discharges and oscillations in CA1 pyramidal neurons, we performed dual whole-cell recordings from a CA1 pyramidal neuron and a nearby oriens/alveus interneuron. Of the eight CA1 pyramidal–interneuron pairs examined, rhythmic discharges were observed in four interneurons after exposure to 5 mm CsCl. In these limited paired recordings, both cells oscillated coherently with a minimum time lag between their hyperpolarizing phases (Fig. 7A,D), implying common GABAergic interneurons that might innervate both cells divergently. The rhythmic discharges of the recorded interneuron appeared to be unnecessary for the generation of the slow oscillations in the corresponding CA1 neuron, because the latter persisted when the interneuron ceased (Fig. 7A).

However, the interneuron shown in Figure 7 might have synaptic connections with the simultaneously recorded CA1 pyramidal neuron. When the slow rhythm was temporally lost, high-frequency firings of the interneuron concurred with an outward shift (hyperpolarization) of the holding current and tonic activities in the CA1 neuron (Fig.7B), implying a massive GABAergic input to the latter, probably originating from the recorded interneuron, from others, or from both. Moreover, some interneuronal spikes (Fig.7C, open circles) recorded 2–3 min later when the slow rhythm began to return were correlated in a nearly one-to-one relation with outward currents in the CA1 neuron (Fig.7C,E). The CA1 outward currents showed a rapid rising phase and a short latency of 1–2 msec after the preceding interneuronal spikes, which are characteristic of monosynaptically evoked IPSCs. Interestingly, interneuronal spikes that occurred rhythmically in clusters (Fig. 7C,E) or were evoked by intracellular injection of depolarizing currents (data not shown) were not followed by the CA1 outward currents with fast rising phase. A similar occasion was also observed in another CA1 pyramidal–interneuron pair. Considering that interneurons possess extensive processes and that action potentials may originate some distant from soma (see below), it is conceivable that interneurons may dynamically innervate their target cells, particularly in the network setting.

The role of endogenous adenosine

Adenosine is a modulatory neurotransmitter implicated in various brain activities (Guieu et al., 1996), including the promotion of slow-wave sleep and associated EEG oscillations (Rainnie et al., 1994;Benington and Heller, 1995; Benington et al., 1995). The inhibition of glutamate transmission by adenosine has been noted for some time and in several brain regions (Green and Haas, 1991; Brundege and Dunwiddie, 1997), which is predominantly mediated by adenosine A1 receptors suppressing calcium influx into presynaptic terminals (Wu and Saggau, 1994). In the hippocampal CA1 region, stimulation of A1 receptors decreases glutamate but not GABAergic transmission (Yoon and Rothman, 1991; Capogna et al., 1993;Khazipov et al., 1995). In viewing such selective modulation by adenosine of CA1 glutamate transmission, we examined whether endogenous adenosine plays a role in shaping the Cs+-induced slow oscillations. Perfusion of slices with 1 μmadenosine amine congener, a stable adenosine analog, caused no oscillatory behavior in CA1 pyramidal neurons (n = 3), but it made the Cs+-induced oscillations more regular (n = 4). In contrast, application of 10 μm DPCPX, an adenosine A1 receptor antagonist, reversibly interrupted the Cs+-induced slow oscillations in CA1 neurons, leading to frequent synaptic activity without a clear pattern (n = 6) (Fig.8A). A similar trend was also observed in oriens/alveus interneurons, where the Cs+-induced rhythmic discharges were converted to tonic firings by 10 μm DPCPX (n = 3) (Fig.8B). The tonic firings were likely caused by the occurrence of nonrhythmic subthreshold synaptic activities, which were clearly viewed when these interneurons were held at hyperpolarized potentials to prevent spiking (Fig. 8C). Collectively, these observations suggest that the Cs+-induced slow oscillations are regulated by endogenous adenosine, which inhibits glutamate transmission via adenosine A1 receptors allowing manifestation of the slow GABAergic rhythm.

The role of interneuronal gap junctions

When recorded in slices and in the presence of low micromole 4-aminopyridine, CA3–hilar interneurons show a cluster of depolarizing responses that onset in 1–2 msec and decay in tens of milliseconds. These small responses are referred as “partial spikes” because they are not blocked by ionotropic glutamate receptor antagonists and appear in the dye-coupled interneurons (Michelson and Wong, 1994). Similar partial spikes were also observed in our recordings of two stratum radiatum interneurons and three oriens/alveus in Cs+. One example is shown in Figure9B,C where a stratum radiatum interneuron displayed periodic partial spikes of a few millivolts, in group with low-amplitude (20–30 mV) and full-size action potentials (≥55 mV). A hyperpolarization of a few millivolts from the resting potential, by intracellular injection of negative DC currents, markedly reduced the appearance of full-size action potentials (Fig.9D); further hyperpolarization to potentials more negative than −60 mV could terminate both low-amplitude and full-size action potentials, leaving only the partial spikes (Fig. 9E). These partial spikes persisted during application of 20 μm CNQX and 50 μm AP5 and had a uniform distribution in their amplitude (Fig. 9F), confirming that they are not glutamate EPSPs. It has been hypothesized that the partial spikes may arise through the cell-to-cell spread of action potentials via electrotonic connections (gap junctions) at some distance from the somatic recording site (Michelson and Wong, 1994; Benardo and Wong, 1995; Traub, 1995; Benardo, 1997; Vigmond et al., 1997). The present observations of periodic partial spikes prompted us to explore the role of interneuronal gap junctions (Kosaka and Hama, 1983, 1985; Katsumaru et al., 1988) in controlling the Cs+-induced slow rhythm.

To examine interneuronal dye coupling (Stewart, 1978; Connors et al., 1983; Dudek et al., 1993; Michelson and Wong, 1994), one interneuron per slice from CA1 oriens/alveus was whole-cell-dialyzed with 0.5% neurobiotin (see Materials and Methods) at room temperature (22–23°C) to maximize the stability. The slices were perfused with 5 mm CsCl to induce interneuronal rhythmic discharges. Histological processing was successfully achieved in 16 slices, such that the cell body and processes of the recorded interneurons were clearly visualized. Dye coupling was found in 6 of the 16 slices in which a second, neurobiotin-stained neuron was readily recognized. The cell body of the secondary neuron resided in oriens/alveus but was usually separated by 100–200 μm in depth from the soma of the recorded ones. One such example is shown in Figure10, in which A shows the cell body and proximal processes of the recorded interneuron, andB shows the cell body of the neurobiotin-coupled neuron from an adjacent section. The two cell bodies were surrounded by extensive cellular processes (Fig. 10C), suggesting neurobiotin coupling via dendritic processes. This is unlikely to be caused by nonspecific background signals, because no staining was observed in stratum pyramidale, where there are densely packed cell bodies of pyramidal neurons, or in the other hippocampal subfields. Cs+-induced rhythmic discharges were observed from the recorded neuron, with frequency comparable to the CA1 oscillations observed at room temperature (∼0.3 Hz) (Fig.10E).

We then examined the effects of known gap junction uncouplers, including octanol, β-glycyrrhetinic acid, and sodium propionate (Nedergaard, 1994; Perez Velazquez et al., 1994; Yuste et al., 1995;Strata et al., 1997). Perfusion of slices with octanol (0.1–0.2 mm) for 2–3 min reversibly abolished the Cs+-induced oscillations in CA1 (n = 8) or neocortical neurons (n = 4), yielding continuously occurring miniature IPSCs–IPSPs (Fig.11A). The evoked EPSCs–IPSCs observed from the same neurons did not show substantial decrease by octanol (n = 4) (Fig. 11C), suggesting that it was unlikely that the interruption of the slow oscillations by octanol was attributable to a nonspecific synaptic inhibition. Interrupted slow oscillations were also observed after brief exposure of slices to β-glycyrrhetinic acid (50 μm, n = 6) or sodium propionate (20 mm, n = 4). Accordingly, the Cs+-induced rhythmic discharges in oriens/alveus interneurons were interrupted by the similar application of octanol, showing irregular, high-frequency firings (n = 6) (Fig.11B).

DISCUSSION

We demonstrate a novel, slow (≤1 Hz) GABAA-mediated oscillation in rat hippocampus, resulting from the blockade of Cs+-sensitive ionic conductances and/or processes. How are these oscillations produced and why does Cs+induce them?

Induction of slow oscillations by external Cs+

In the hippocampal neurons, the ionic conductance known to be highly sensitive to low millimole CsCl is the inward rectifier current, termed Ih or IQ(DiFrancesco, 1982; Halliwell and Adams, 1982; McCormick and Pape, 1990; Maccaferri and McBain, 1996). The Ihactivates tonically at the resting potential as an inward (depolarizing) current, and it increases with hyperpolarization and decreases with depolarization, thus counteracting shifts in the membrane potential. We show here that the slow oscillations were consistently induced by 3–5 mm CsCl, but not by commonly used potassium channel blockers such as barium, tetraethylammonium, or 4-aminopyridine. Moreover, Cs+ application attenuated the Ih but not the depolarization-stimulated outward currents in interneurons (Maccaferri and McBain, 1996). These observations suggest that the slow oscillations may result from, or be closely associated with, the blockade of Cs+-sensitiveIh.

The ionic mechanisms by which Cs+ promotes interneuronal rhythmic discharges and hence the slow GABAA-mediated oscillations are not fully understood. Given that the Cs+-induced discharges arise spontaneously from the interneurons at the resting potential, the interplay among K+, Na+, and synaptic currents at the voltages near the firing threshold, as suggested in neostriatal neurons (Wilson and Kawaguchi, 1996), may play pivotal roles in initiating or controlling interneuronal discharges. We speculate that the blockade of the Ih makes interneurons more compact electrotonically, thereby amplifying or promoting their responsiveness to the low-threshold, sustained Na+current and other K+ currents (French et al., 1990;Alzheimer et al., 1993; Skinner et al., 1998). By blocking inwardIh, Cs+ hyperpolarizes the cell (Maccaferri and McBain, 1996), and modeling work reveals that hyperpolarizations can induce the fire–pause pattern in interneuronal networks (Skinner et al., 1998).

Other Cs+-sensitive conductances or processes, however, may also be involved. For instance, we have recorded presumed glial cells that showed resting potentials more negative than −70 mV, membrane resistance of ≤10 MΩ, and no action potential or synaptic response. These glia cells (n = 8) displayed no oscillation but did display a great increase in membrane resistance after the Cs+ exposure (data not shown). Blockade of Cs+-sensitive, Ih-like currents in astroglia in turn may cause a decrease in extracellular space and an overall increase in ephaptic coupling in brain tissue, therefore promoting the propagation of the slow oscillations. In addition, Cs+ exposure may promote the release of adenosine from neuronal and/or glial sources (Fredholm et al., 1994;Brundege and Dunwiddie, 1996), and the resulting activation of adenosine A1 receptors may suppress glutamate inputs to pyramidal neurons and/or interneurons, allowing the interneuronal networks to operate on their own rhythmicity.

Coherent activity generated from interneuronal networks

It is now known that coherent rhythms can originate from inhibitory networks if the inhibition is slow relative to the firing rate (Wang and Rinzel, 1992). We propose that the Cs+-induced slow oscillations are generated by the activity of GABAergic interneuronal networks, on the basis of the following convergent evidence. First, the oscillations—as recorded from CA1 pyramidal neurons—were GABAA-mediated synaptic events, but the onset of individual oscillatory events was much slower than the rise time of the IPSCs–IPSPs elicited by afferent stimulation, implying a diversity of GABA synapses that activate coherently but not simultaneously to produce the slow rhythm. Second, the slow oscillations persisted without the necessity of activating fast glutamate transmission but were correlated closely with the rhythmic discharges in multiple interneurons, suggesting the involvement of coherent activity from a group of interneurons. Third, the evoked IPSCs in CA1 pyramidal neurons were prolonged threefold by Cs+. Periodic hyperpolarizations (presumably summed IPSPs) lasting ∼1 sec were also observed in interneurons, and blockade of these hyperpolarizations by bicuculline interrupted the Cs+-induced rhythmic discharges. Fourth, the frequency of the slow oscillations can be manipulated by partial blockade of GABAA receptors with 10 nmbicuculline (Fig. 5A). These observations suggest the emergence of the slow, GABAA-mediated inhibition in reciprocally innervated interneurons, which are critical in maintaining and/or regulating interneuronal rhythmicity. We cannot rule out, however, the possibility that the Cs+-induced slow oscillations may result from the activity of one or a few pacemaker interneurons that possess extensive axonal arborization. This seems unlikely, because these interneurons reside predominantly in CA1 stratum pyramidale (Cobb et al., 1995), whereas in our experiments, interneurons recorded from stratum pyramidale did not discharge spontaneously in Cs+ (Table 2).

We showed that during simultaneous recordings of an interneuron (oriens/alveus) and a CA1 pyramidal neuron, the interneuron discharged rhythmically in a close phase-relation with, but did not elicit by itself, the slow oscillations in the CA1 neuron (Fig. 7A). However, the interneuron appeared to be capable of triggering IPSC-like outward currents in the CA1 neuron (Fig. 7C,E). These observations are consistent with the idea that cooperative activities among interconnected interneurons are responsible for the CA1 slow oscillations. From the view of classic synaptic physiology, one would argue that the activity of a given interneuron should at least partially control the generation of the slow oscillations in an innervated CA1 neuron. The lack of such demonstration in the present experiments may be attributable partly to our limited recordings of CA1 pyramidal-interneuron pairs. It is conceivable that future experiments with large samples of such paired recordings, particularly by recording interneurons at different CA1 subfields, may clarify this issue.

Possible involvement of interneuronal gap junctions

There is controversy regarding the existence of gap junctions in hippocampal interneurons. Early studies using immunohistological techniques have shown gap junctions (connexin 27) in hippocampal interneurons, which manifest dendritic–dendritic or dendritic–axonal contacts (Kosaka and Hama, 1985; Katsumaru et al., 1988). Dye coupling, which is used as presumptive evidence for electrotonic coupling via gap junctions in living cells (Stewart, 1978; Connors et al., 1983; Dudek et al., 1993), is not seen in hippocampal interneurons recordedin vivo (cf. Freund and Buzsáki, 1996), but it is evident in brain slices, particularly in the CA3–hilar region (Michelson and Wong, 1994; Strata et al., 1997). Dye couplings among interneurons have been noted previously in other brain regions, including neocortex (Mollgard and Moller, 1975, 1983; Sloper and Powell, 1978; Smith and Moskovitz, 1979; Connors et al., 1983; Benardo, 1997), cerebellum (Sotelo and Llinas, 1972), and olfactory bulb (Reyher et al., 1991).

In the present experiments, neurobiotin coupling was observed in 6 of 16 interneurons successfully processed, but no coupling was found in interneurons dialyzed with Lucifer yellow (n = 23; data not shown). The neurobiotin-coupled oriens/alveus neurons were defined as clearly stained cell bodies that were separated by at least 100 μm from the recorded interneurons. In addition to neurobiotin coupling, some interneurons showed partial spikes, which may reflect discharges of coupled neurons communicated via gap junctional connections (Michelson and Wong, 1994; Traub, 1995). Furthermore, brief application of known gap junction uncouplers, such as octanol, β-glycyrrhetinic acid, or sodium propionate (Nedergaard, 1994; Perez Velazquez et al., 1994; Yuste et al., 1995; Han et al., 1996; Strata et al., 1997), reversibly interrupted the Cs+-induced rhythms in CA1 pyramidal neurons or interneurons, without affecting the evoked EPSCs–IPSCs or interneuronal discharges. This convergent evidence supports the idea that interneuronal gap junctions may function to sustain and recruit synchronized interneuronal discharges (Michelson and Wong, 1994; Benardo and Wong, 1995; Benardo, 1997).

A model mechanism

To understand the genesis of the slow oscillator behavior, we developed a minimal biophysical model of a two-cell network (Skinner et al., 1998). Each model cell contains Hodgkin-Huxley spike currents, a low-threshold sustained sodium current (INa) (French et al., 1990; Alzheimer et al., 1993), and a slowly inactivating potassium current (ID) (Storm, 1988). These two cells are coupled with mutual GABAA inhibition and gap junctions. The addition of Cs+, modeled as a hyperpolarization attributable to the blockade of inward rectifierIh, produces a stable, synchronized fire–pause pattern in the model network. Both mutual inhibition and gap junction communication are required to obtain this pattern. The fire–pause pattern is set by the interplay amongINa, ID, and synaptic inhibition. The first spike fires because of the increase in INa and the resulting depolarization; firings eventually terminate because of the increase inID relative to INa. Synaptic inhibition is required to hyperpolarize the postsynaptic cell so that the inactivation of ID can be sufficiently removed, allowing the oscillatory behavior to occur. It is found that the role of gap junction coupling is not only to synchronize but also to stabilize the pattern.

In summary, we demonstrate a Cs+-induced, slow oscillatory inhibition of ≤1 Hz arising from GABAergic synapses in hippocampus and perhaps also in neocortex. This is attributable to the network activity of GABAergic interneurons via reciprocal inhibition and possibly gap junction coupling. It remains to be shown whether such mechanisms occur in vivo, and if so, what the physiological and pathophysiological significance of such slow oscillations is in slow wave sleep or epileptiform activity.

Footnotes

This work was supported by the the Medical Research Council of Canada. L.Z. is a Scholar of the Heart and Stroke Foundation of Canada and Ontario.

Correspondence should be addressed to Dr. L. Zhang, Playfair Neuroscience Unit, Room 13-411, Toronto Hospital (Western Division), 399 Bathurst Street, Toronto, Ontario, Canada M5T 2S8.

Dr. Tian’s present address: Brain Injury Research Laboratory, Cara Phelan Centre for Trauma Research and the Department of Anesthesia, St. Michael’s Hospital, Toronto, Ontario, Canada M5B 1W8.

REFERENCES

- 1.Alzheimer C, Schwindt PC, Crill WE. Modal gating of Na+ channels as a mechanism of persistent Na+ current in pyramidal neurons from rat and cat sensorimotor cortex. J Neurosci. 1993;13:660–673. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.13-02-00660.1993. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Amzica F, Steriade M. The K-complex: its slow (≤1-Hz) rhythmicity and relation to delta waves. Neurology. 1997;49:952–959. doi: 10.1212/wnl.49.4.952. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Avoli M, Barbarosie M, Lücke A, Nagao T, Lopantsev V, Köhling R. Synchronous GABA-mediated potentials and epileptiform discharges in the rat limbic system in vitro. J Neurosci. 1996;16:3912–3924. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.16-12-03912.1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Benardo LS. Recruitment of GABAergic inhibition and synchronization of inhibitory interneurons in rat neocortex. J Neurophysiol. 1997;77:3134–3144. doi: 10.1152/jn.1997.77.6.3134. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Benardo LS, Wong RKS. Inhibition in the cortical network. In: Mody I, Gutnick MJ, editors. The cortical neurons. Oxford UP; New York: 1995. pp. 141–155. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Benington JH, Heller HC. Restoration of brain energy metabolism as the function of sleep. Prog Neurobiol. 1995;45:347–360. doi: 10.1016/0301-0082(94)00057-o. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Benington JH, Kodali SK, Heller HC. Stimulation of A1 adenosine receptors mimics the electroencephalographic effects of sleep deprivation. Brain Res. 1995;692:79–85. doi: 10.1016/0006-8993(95)00590-m. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Brundege JM, Dunwiddie TV. Modulation of excitatory synaptic transmission by adenosine released from single hippocampal pyramidal neurons. J Neurosci. 1996;16:5603–5612. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.16-18-05603.1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Brundege JM, Dunwiddie TV. Role of adenosine as a modulator of synaptic activity in the central nervous system. Adv Pharmacol. 1997;39:353–391. doi: 10.1016/s1054-3589(08)60076-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Buhl EH, Halasy K, Somogyi P. Diverse sources of hippocampal unitary inhibitory postsynaptic potentials and the number of synaptic release sites. Nature. 1994;368:823–828. doi: 10.1038/368823a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Buzsáki G, Chrobak JJ. Temporal structure in spatially organized neuronal ensembles: a role for interneuronal networks. Curr Opin Neurobiol. 1995;5:504–510. doi: 10.1016/0959-4388(95)80012-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Capogna M, Gähwiler BH, Thompson SM. Mechanisms of mu-opiod receptor-mediated presynaptic inhibition in rat hippocampus in vitro. J Physiol (Lond) 1993;470:539–558. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.1993.sp019874. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Cherubini E, GaVarsa JL, Ben-Ari Y. GABA: an excitatory neurotransmitter in early postnatal life. Trends Neurosci. 1991;14:514–519. doi: 10.1016/0166-2236(91)90003-d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Cobb SR, Buhl EH, Halasy K, Paulsen O, Somogyi P. Synchronization of neuronal activities in hippocampus by individual GABAergic interneurons. Nature. 1995;378:75–78. doi: 10.1038/378075a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Cohen GA, Doze VA, Madison DV. Opioid inhibition of GABA release from presynaptic terminals of rat hippocampi. Neuron. 1992;9:325–335. doi: 10.1016/0896-6273(92)90171-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Conn PJ, Pin JP. Pharmacology and functions of metabotropic glutamate receptors. Annu Rev Pharmacol Toxicol. 1997;37:205–237. doi: 10.1146/annurev.pharmtox.37.1.205. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Connors BW, Benardo LS, Prince DA. Coupling between neurons of the developing rat neocortex. J Neurosci. 1983;3:773–782. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.03-04-00773.1983. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Contreras D, Steriade M. Cellular basis of EEG slow rhythms: a study of dynamic corticothalamic relationship. J Neurosci. 1995;15:604–622. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.15-01-00604.1995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Contreras D, Destexhe A, Sejnowski TJ, Steriade M. Control of spatiotemporal coherence of a thalamic oscillation by corticothalamic feedback. Science. 1996a;274:771–774. doi: 10.1126/science.274.5288.771. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Contreras D, Timofeev I, Steriade M. Mechanisms of long-lasting hyperpolarizations underlying slow sleep oscillations in cat corticothalamic networks. J Physiol (Lond) 1996b;494:251–264. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.1996.sp021488. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.DiFrancesco D. Block and activation of the pacemaker channel in calf Purkinje fibers: effects of potassium, cesium and rubidium. J Physiol (Lond) 1982;329:485–507. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.1982.sp014315. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Dudek FE, Andrew RD, MacVicar BA, Snow RW, Taylor CP. Recent evidences for and possible significance of gap junctions and electrotonic synapses in the mammalian brain. In: Jasper HH, Van Gelder NM, editors. Brain mechanisms of neuronal hyperexcitability. Liss; New York: 1993. pp. 31–73. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Fredholm BB, Lindström K, Wallman-Johansson A. Propentofylline and other adenosine transport inhibitors increase the efflux of adenosine following electrical or metabolic stimulation of rat hippocampal slices. J Neurochem. 1994;62:563–573. doi: 10.1046/j.1471-4159.1994.62020563.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.French CR, Sah P, Buckett KJ, Gage PW. A voltage-dependent persistent sodium current in mammalian hippocampal neurons. J Gen Physiol. 1990;95:1139–1157. doi: 10.1085/jgp.95.6.1139. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Freund TF, Buzsáki G. Interneurons of hippocampus. Hippocampus. 1996;6:347–470. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1098-1063(1996)6:4<347::AID-HIPO1>3.0.CO;2-I. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Gambardella A, Gotman J, Cenes F, Andermann F. Focal intermittent delta activity in patients with mesiotemporal atrophy: a reliable marker of the epileptogenic focus. Epilepsia. 1995;36:122–129. doi: 10.1111/j.1528-1157.1995.tb00970.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Green RW, Haas HL. The electrophysiology of adenosine in the mammalian central nervous system. Prog Neurobiol. 1991;36:329–341. doi: 10.1016/0301-0082(91)90005-l. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Guieu R, Couraud F, Pouget J, Sampieri F, Bechis G, Rochat H. Adenosine and the nervous system: clinical implications. Clin Neuropharmacol. 1996;19:459–474. doi: 10.1097/00002826-199619060-00001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Gulyás AI, Hájos N, Freund TF. Interneurons containing calretinin are specialized to control other interneurons in the rat hippocampus. J Neurosci. 1996;16:3397–3411. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.16-10-03397.1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Halliwell JV, Adams PR. Voltage-clamp analysis of muscarinic excitation in hippocampal neurons. Brain Res. 1982;250:71–92. doi: 10.1016/0006-8993(82)90954-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Han D, Perez Velazquez JL, Zhang L, Carlen PL. Electrical interactions between neurons after tetanic stimulation-induced epileptiform activity in rat hippocampal parahippocampal slice. Soc Neurosci Abstr. 1996;22:2103. [Google Scholar]

- 32.Janigro D, Gasparini S, D’Ambrosio R, McKhann GII, DiFrancesco D. Reduction of K+ uptake in glia prevents long-term depression maintenance and causes epileptiform activity. J Neurosci. 1997;17:2813–2824. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.17-08-02813.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Jefferys JG, Traub RD, Whittington MA. Neuronal networks for induced “40 Hz” rhythms. Trends Neurosci. 1996;19:202–208. doi: 10.1016/s0166-2236(96)10023-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Katsumaru H, Kosaka T, Heizman CW, Hama K. Gap junctions on GABAergic neurons containing the calcium-binding protein parvalbumin in the rat hippocampus (CA1 region). Exp Brian Res. 1988;72:363–370. doi: 10.1007/BF00250257. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Kawaguchi Y, Hama K. Fast-spiking non-pyramidal cells in the hippocampal CA3 region, dentate gyrus and subiculum of rats. Brain Res. 1987;425:351–355. doi: 10.1016/0006-8993(87)90518-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Kawaguchi Y, Hama K. Physiological heterogeneity of nonpyramidal cells in rat hippocampal CA1 region. Exp Brain Res. 1988;72:494–502. doi: 10.1007/BF00250594. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Khazipov R, Congar P, Ben-Ari Y. Hippocampal CA1 lacunosum-moleculare interneurons: comparison of effects of anoxia on excitatory and inhibitory postsynaptic currents. J Neurophysiol. 1995;74:2138–2149. doi: 10.1152/jn.1995.74.5.2138. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Kosaka T. Gap junctions between non-pyramidal cell dendrites in the rat hippocampus (CA1 and CA3 regions). Brain Res. 1983;271:157–161. doi: 10.1016/0006-8993(83)91377-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Kosaka T, Hama K. Gap junctions between non-pyramidal cell dendrites in the rat hippocampus (CA1 and CA3 regions): a combined Golgi-electron microscopy study. J Comp Neurol. 1985;231:150–161. doi: 10.1002/cne.902310203. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Lacaille JC, Schwartzkroin PA. Stratum lacunosum-moleculare interneurons of hippocampal CA1 region. I. Intracellular response characteristics, synaptic responses, and morphology. J Neurosci. 1988;8:1400–1410. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.08-04-01400.1988. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Lacaille JC, Mueller A, Kunkel DD, Schwartzkroin PA. Local circuit interactions between oriens/alveus interneurons and CA1 pyramidal cells in hippocampal slices: electrophysiology and morphology. J Neurosci. 1987;7:1979–1993. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.07-07-01979.1987. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Maccaferri G, McBain CJ. The hyperpolarization-activated current (Ih) and its contribution to pacemaker activities in rat CA1 hippocampal stratum oriens-alveus interneurons. J Physiol (Lond) 1996;497:119–130. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.1996.sp021754. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Madison DV, Nicoll RA. Enkaphalin hyperpolarizes interneurones in the hippocampus. J Physiol (Lond) 1989;398:123–130. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.1988.sp017033. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.McBain CJ. Hippocampal inhibitory neuron activity in the elevated potassium model of epilepsy. J Neurophysiol. 1994;72:2853–2863. doi: 10.1152/jn.1994.72.6.2853. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.McCormick DA, Pape HC. Properties of a hyerpolarization-activated cation current and its role in rhythmic oscillation in thalamic relay neurons. J Physiol (Lond) 1990;431:291–318. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.1990.sp018331. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Michelson HB, Wong RKS. Synchronization of inhibitory neurons in the guinea-pig hippocampus in vitro. J Physiol (Lond) 1994;477:35–45. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.1994.sp020169. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Mollgard K, Moller M. Dendrodendritic gap junctions (a developmental approach). Adv Neurol. 1975;12:79–89. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Morin F, Beaulieu C, Lacaille JC. Membrane properties and synaptic currents evoked in CA1 interneuron subtypes in rat hippocampal slices. J Neurophysiol. 1996;76:1–16. doi: 10.1152/jn.1996.76.1.1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Nedergaard M. Direct signaling from astrocytes to neurons in culture of mammalian brain cells. Science. 1994;263:1768–1771. doi: 10.1126/science.8134839. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Nicoll RA, Alger BE, Jahr CE. Enkephalin blocks inhibitory pathways in the vertebrate CNS. Nature. 1980;287:22–25. doi: 10.1038/287022a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Niedermeyer E. Sleep and EEG. In: Niedermeyer E, DaSilva FL, editors. Electroencephalography. Williams & Wilkins; Baltimore: 1993. pp. 153–166. [Google Scholar]

- 52.Normand M, Wszolek ZK, Klass DW. Temporal intermittent rhythmic delta activity in electroencephalogram. J Clin Neurophysiol. 1995;12:280–284. doi: 10.1097/00004691-199505010-00005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Perez Velazquez JL, Valiante TA, Carlen PL. Modulation of gap junctional mechanisms during calcium-free induced burst activity: a possible role for electrotonic coupling in epileptogenesis. J Neurosci. 1994;14:4308–4317. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.14-07-04308.1994. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Rainnie DG, Grunze HCR, McCarley RW. Adenosine inhibition of mesopontine cholinergic neurons: implications for EEG arousal. Science. 1994;263:689–892. doi: 10.1126/science.8303279. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Reiher J, Beaudry M, Leduc CP. Temporal intermittent rhythmic delta activity (TIRDA) in the diagnosis of complex partial epilepsy: sensitivity, specificity and predictive value. Can J Neurol Sci. 1989;16:398–401. doi: 10.1017/s0317167100029450. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Reyher CK, Lubke J, Larsen WJ, Hendrix GM, Shipley MT, Baumgarten HG. Olfactory bulb granule cell aggregates: morphological evidence for interperikaryal electrotonic coupling via gap junction. J Neurosci. 1991;11:485–495. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.11-06-01485.1991. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Skinner FK, Zhang L, Perez Velazquez JL, Carlen PL (1998) Bursting in inhibitory interneuronal networks: a role for gap-junctional coupling. J Neurophysiol, in press. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 58.Sloper JJ, Powell TPS. Gap junctions between dendrites and somata of neurones in the primate sensorimotor cortex. Proc R Soc Lond B Biol Sci. 1978;203:39–47. doi: 10.1098/rspb.1978.0089. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Smith DE, Moskovitz N. Ultrastructure of layer IV of the primary auditory cortex of the squirrel monkey. Neuroscience. 1979;4:349–360. doi: 10.1016/0306-4522(79)90098-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Sohn HG, Vassalle M. Cesium effects on dual pacemaker mechanisms in guinea pig sinoatrial node. J Mol Cell Cardiol. 1995;27:563–577. doi: 10.1016/s0022-2828(08)80051-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Sotelo C, Llinas R. Specialized membrane junctions between neurons in the vertebrate cerebellar cortex. J Cell Biol. 1972;53:271–289. doi: 10.1083/jcb.53.2.271. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Spigelman I, Zhang L, Carlen PL. Patch-clamp study of postnatal development of CA1 neurones in rat hippocampal slices: membrane excitability and K+ currents. J Neurophysiol. 1992;68:55–69. doi: 10.1152/jn.1992.68.1.55. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Steriade M. Cellular substrates of brain rhythm. In: Niedermeyer E, DaSilva FL, editors. Electroencephalography. Williams & Wilkins; Baltimore: 1993. pp. 27–62. [Google Scholar]

- 64.Steriade M, McCormick DA, Sejnowski TJ. Thalamocortical oscillations in the sleeping and aroused brain. Science. 1993a;262:679–685. doi: 10.1126/science.8235588. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Steriade M, Nunes A, Amzica F. A novel slow oscillation (≤1 Hz) of neocortical neurons in vivo: depolarizing and hyperpolarizing components. J Neurosci. 1993b;13:3252–3265. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.13-08-03252.1993. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Stewart WW. Functional connections between cells as revealed by dye-coupling with a highly fluorescent napthalimide tracer. Cell. 1978;14:741–759. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(78)90256-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Storm JF. Temporal integration by a slowly inactivating K+ current in hippocampal neurons. Nature. 1988;336:379–381. doi: 10.1038/336379a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Strata F, Atzori M, Molnar M, Ugolini G, Tempia F, Cherubini E. A pacemaker current in dye-coupled hilar interneurons contributes to the generation of giant GABAergic potentials in developing hippocampus. J Neurosci. 1997;17:1435–1446. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.17-04-01435.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Traub RD. Model of synchronized population bursts in electrically coupled interneurons containing active dendritic conductances. J Comp Neurosci. 1995;2:283–289. doi: 10.1007/BF00961440. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Traub RD, Whittington MA, Colling SB, Buzsaki G, Jeffreys JGR. Analysis of gamma rhythms in the rat hippocampus in vitro and in vivo. J Physiol (Lond) 1996;493.2:471–484. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.1996.sp021397. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Vigmond EJ, Perez Velazquez JL, Valiante TA, Bardakjian BL, Carlen PL. Mechanisms of electrical coupling between pyramidal cells. J Neurophysiol. 1997;78:3107–3116. doi: 10.1152/jn.1997.78.6.3107. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Wang XJ, Buzsáki G. Gamma oscillation by synaptic inhibition in a hippocampal interneuronal network model. J Neurosci. 1996;16:6402–6413. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.16-20-06402.1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Wang XJ, Rinzel J. Alternating and synchronous rhythms in reciprocally inhibitory model neurons. Neural Comput. 1992;4:84–97. [Google Scholar]

- 74.Whittington MA, Traub RD, Jeffery JGR. Synchronized oscillations in interneuron networks driven by metabotropic glutamate receptor activation. Nature. 1995;373:612–615. doi: 10.1038/373612a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Wilson CJ, Kawaguchi Y. The origin of two-state spontaneous membrane potential functions of neostriatal neurons. J Neurosci. 1996;16:2397–2410. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.16-07-02397.1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Wu LG, Saggau P. Adenosine inhibits evoked synaptic transmission primarily by reducing presynaptic calcium influx in area CA1 of hippocampus. Neuron. 1994;12:1139–1148. doi: 10.1016/0896-6273(94)90321-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Yoon KW, Rothman SM. Adenosine inhibits excitatory but not inhibitory synaptic transmission in the hippocampus. J Neurosci. 1991;11:1375–1380. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.11-05-01375.1991. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Yuste R, Nelson DA, Rubin WW, Katz LC. Neuronal domains in developing neocortex: mechanisms of coactivation. Neuron. 1995;14:7–17. doi: 10.1016/0896-6273(95)90236-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Zhang L, Spigelman I, Carlen PL. Development of GABA-mediated, chloride-dependent inhibition in CA1 pyramidal neurones of immature hippocampal slices. J Physiol (Lond) 1991;444:25–49. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.1991.sp018864. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Zhang L, Weiner JL, Carlen PL. Potentiation of GABAA receptor-mediated synaptic currents by pentobarbital and diazepam in immature hippocampal CA1 neurons. J Exp Pharmacol Ther. 1993;266:1227–1235. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Zhang L, Weiner JL, Valiante TA, Velumian AA, Walson P, Jahromi SS, Schetzer S, Pennefather PS, Carlen PL. Effects of internally applied anions on the Ca2+-activated afterhyperpolarization in rat hippocampal neurons. Pflügers Arch. 1994;426:247–253. doi: 10.1007/BF00374778. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Zhang L, Zhang Y, Wennberg R (1998) Multiple actions of methohexital on hippocampal CA1 and cortical neurons of rat brain slices. J Pharmacol Exp Ther, in press. [PubMed]

- 83.Zieglgänsberger W, French ED, Siggins CR, Bloom FE. Opioid peptides may excite hippocampal neurons by inhibiting adjacent inhibitory interneurons. Science. 1979;205:415–417. doi: 10.1126/science.451610. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]