Abstract

ATP analogs substituted in the γ-phosphorus (ATPγS, β,γ-imido-ATP, and β,γ-methylene-ATP) were used to probe the involvement of P2 receptors in the modulation of synaptic transmission in the hippocampus, because their extracellular catabolism was virtually not detected in CA1 slices. ATP and γ-substituted analogs were equipotent to inhibit synaptic transmission in CA1 pyramid synapses (IC50 of 17–22 μm). The inhibitory effect of ATP and γ-phosphorus-substituted ATP analogs (30 μm) was not modified by the P2 receptor antagonist suramin (100 μm), was inhibited by 42–49% by the ecto-5′-nucleotidase inhibitor and α,β-methylene ADP (100 μm), was inhibited by 74–85% by 2 U/ml adenosine deaminase (which converts adenosine into its inactive metabolite-inosine), and was nearly prevented by the adenosine A1 receptor antagonist 1,3-dipropyl-8-cyclopentylxanthine (10 nm). Stronger support for the involvement of extracellular adenosine formation as a main requirement for the inhibitory effect of ATP and γ-substituted ATP analogs was the observation that an inhibitor of adenosine uptake, dipyridamole (20 μm), potentiated by 92–124% the inhibitory effect of ATP and γ-substituted ATP analogs (10 μm), a potentiation similar to that obtained for 10 μm adenosine (113%). Thus, the present results indicate that inhibition by extracellular ATP of hippocampal synaptic transmission requires localized extracellular catabolism by ecto-nucleotidases and channeling of the generated adenosine to adenosine A1 receptors.

Keywords: ATP, adenosine, ecto-nucleotidases, hippocampus, ATP analogs, P2 receptors, A1 receptors

ATP is currently recognized as a neurotransmitter and a neuromodulator in the nervous system (for review, see Zimmermann, 1994). In the hippocampus, ATP is released on stimulation (Terrian et al., 1989; Cunha et al., 1996a; Wieraszko, 1996) and is a potent inhibitor of hippocampal neuronal excitability (Lee et al., 1981; Stone and Cusack, 1989; Cunha et al., 1996b). ATP may directly control neuronal activity either by activating hippocampal P2 receptors (Kidd et al., 1995; Collo et al., 1996; Inoue et al., 1996) or by acting as a substrate of ecto-protein kinase during synaptic plasticity phenomena (Wieraszko, 1996). ATP may also indirectly modulate neuronal excitability after its extracellular catabolism by the ecto-nucleotidase cascade (Lee et al., 1981; Cunha et al., 1992), generating adenosine that modulates synaptic transmission through inhibitory adenosine A1 receptors or facilitatory A2A receptors (Cunha et al., 1994a).

The proposal that P2 receptors are involved in the modulation of synaptic transmission mostly relies on the use of metabolically stable ATP analogs (Fredholm et al., 1994). However, it has been proposed that metabolically stable ATP analogs may inhibit neurotransmission either through direct action on inhibitory adenosine A1 receptors (Hourani et al., 1991; Bailey et al., 1992;Piper and Hollinsworth, 1996) or indirectly after their localized catabolism into adenosine (Bruns, 1990; Cascalheira and Sebastião, 1992).

In the present work we investigated the relationship between the effects of ATP analogs on synaptic transmission in the hippocampus and their extracellular catabolism in this preparation. We observed a mismatch between the absence of extracellular catabolism of γ-substituted ATP analogs in CA1 slices with the modification of the inhibitory effect of γ-substituted ATP analogs by inhibitors of extracellular purinergic metabolism. This lead us to conclude that γ-substituted ATP analogs might undergo minute localized catabolism into adenosine, and this adenosine is channeled to adenosine A1 receptors. It is suggested therefore that the possibility of mechanisms of preferential substrate delivery between ecto-nucleotidases and adenosine receptors ought to be taken into account and tested through functional assays using modulators of purine metabolism whenever effects of apparently stable adenine nucleotides are observed. This might be of particular relevance when the actions of adenine nucleotides do not easily fit to P2X or P2Y receptor-mediated actions.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

ATP, ADP, AMP, adenosine, adenosine-5′-O-(α,β-methylene)-diphosphonate sodium salt (AOPCP), β,γ-imido ATP tetralithium salt (β,γ-imido-ATP), β,γ-methylene ATP sodium salt (β,γ-methylene-ATP), α,β-methylene ATP dilithium salt (α,β-methylene-ATP), adenosine 5′-O-(3-thio)-triphosphate tetralithium salt (ATPγS), 2′-deoxyadenosine, 2′-deoxyadenosine-5′-triphosphate (2′-dATP),p-nitrophenylphosphate, hypoxanthine, and inosine were from Sigma (St. Louis, MO). Adenosine deaminase (type VI, 1803 U/ml, EC3.5.4.4) was also purchased from Sigma, in a suspension in 50% (vol/vol) glycerol in potassium phosphate, pH 6.0, and dilutions of this suspension were used, together with appropriate corrections of glycerol and KH2PO4 content of all control solutions. 2-Methylthio-ATP tetrasodium salt (2-methylthio-ATP), 1,3-dipropyl-8-cyclopentylxanthine (DPCPX), suramin, reactive blue 2, and pyridoxal-phosphate-6-azophenyl-2′,4′-disulfonic acid (PPADS) were from RBI (Natick, MA). 2-Methylthio-ADP trilithium salt and 2-methylthio-AMP dilithium salt were from Boehringer Mannheim (Indianapolis, IN), and dipyridamole was from Boehringer Ingelheim. KH2PO4 (Aristar) was from BDH Chemicals (Poole, UK), methanol (Chromosolv) was from Riedel, and tetrabutylammonium (PIC-A) was from Waters Associates (Milford, MA). All other reagents were of the highest purity available.

All nucleotide stock solutions were made up into a 5 mmstock solution in water. Because most commercially available ATP analogs are contaminated (up to 5%) by ATP, ADP, and other unidentified substances, ATP analogs (except 2′-dATP) were separated by HPLC (as described below) before their use in electrophysiological or kinetic experiments. It was observed (data not shown) that the HPLC eluent did not affect synaptic transmission or ATP catabolism in CA1 hippocampal synaptosomes. DPCPX was made up into a 5 mmstock solution in 99% dimethylsulfoxide/1% NaOH (1 m) (vol/vol). Dipyridamole was made up into a 5 mmdimethylsulfoxide solution. All stock solutions were stored as frozen aliquots at −20°C. Aqueous dilutions of these stock solutions were made daily and appropriate solvent controls were performed. The pH of the superfusion solution did not change by the addition of the drugs in the maximum concentrations used.

Electrophysiological recordings of synaptic transmission. Rat hippocampal slices (400 μm thick) were prepared (Cunha et al., 1994a) and allowed to recover for 1 hr at room temperature in artificial cerebrospinal fluid of the following composition (in mm): NaCl 124, KCl 3, KH2PO4 1.25, MgSO4 1, CaCl2 2, NaHCO3 26, glucose 10, pH 7.4, gassed with a 95% O2 and 5% CO2 mixture. One slice was transferred to a 1 ml recording chamber for submerged slices and superfused continuously with gassed artificial cerebrospinal fluid, kept at 30.5°C, at a flow rate of 3 ml/min. Drugs were added to this superfusion solution.

Electrophysiological recordings of field EPSPs (fEPSPs) were obtained as described previously (Cunha et al., 1994a). Monopolar stimulation (rectangular pulses of 0.1 msec applied once every 10 sec) was delivered through an electrode placed on the Schaffer fibers, in the stratum radiatum near the CA3/CA1 border. Orthodromically evoked fEPSPs were recorded through an extracellular microelectrode (4 mNaCl, 2–6 MΩ resistance) placed in the stratum radiatum of the CA1 area. The intensity of the stimulus (130–310 μA) was adjusted to evoke the largest fEPSP without population spike contamination. The individual responses were displayed on a Tektronix (2430A) oscilloscope, and the averages of eight consecutive responses were digitally recorded. fEPSP responses were quantified as the initial slope of the averaged fEPSPs. Perfusion of a slice with any tested drugs was started after a stable response was recorded.

When concentration response curves for ATP analogs were performed, each compound was added in increasing concentrations in a cumulative manner, followed by washout. When the ability of a given substance to modify the effect of ATP analogs was tested, ATP analogs were first tested in the absence of the substance, the substance was then applied to the preparation for at least 30 min, and the effect of the ATP analogs was then tested in the presence of the substance. Usually the substance was washed out, and the effect of ATP analogs was tested again in the absence of the substance.

Extracellular catabolism of ATP analogs in CA1 slices.Slices from the CA1 area were manually dissected (Cunha et al., 1994b) and allowed to recover for 1 hr at room temperature in artificial cerebrospinal fluid gassed with a 95% O2 and 5% CO2 mixture. Groups of three CA1 slices were then transferred to incubation vials with 500 μl of Krebs’ solution of the following composition (in mm): NaCl 125, KCl 3, KH2PO4 1.25, MgSO4 1, CaCl2 2, HEPES 25, glucose 10, pH 7.4, kept at 30.5°C under continuous orbital swirling. After 10 min incubation, the initial substrate, i.e., ATP or an ATP analog, was added at a final concentration of 30 μm. The kinetic protocols consisted of a 20 min incubation period with sample collection (50 μl) at 0, 1, 2, 5, 10, 15, and 20 min. The zero time was defined as the sample collected immediately after (∼2–5 sec) addition of the initial substrate. The samples were stored on ice and analyzed by HPLC. After the incubation, the remaining bathing solution was removed, and the slices were homogenized in 200 μl of 2% (vol/vol) Triton X-100 to determine total lactate dehydrogenase activity and protein content. Lactate dehydrogenase activity, an index of cellular disruption (Cunha et al., 1992), was quantified in the bathing solution and was always lower than 2% of total lactate dehydrogenase activity in the CA1 slices.

Extracellular catabolism of adenine nucleotides in CA1 synaptosomes. Synaptosomes from the CA1 area were obtained from homogenized, manually dissected CA1 slices by a sucrose–Percoll method (Cunha et al., 1992). Aliquots of 100 μl of the synaptosomes (resuspended in 800 μl of Krebs’ solution) were then added to incubation vials with 400 μl of Krebs’ solution kept at 30.5°C. After a 10 min incubation, the initial substrate, i.e., ATP, or an ATP analog, or AMP in the presence of ATP analogs, was added at a final concentration of 30 μm. The kinetic protocols were identical to these described for CA1 slices. Each collected sample was centrifuged (14,000 × g for 15 sec) in a refrigerated centrifuge (4°C), and the supernatant (50 μl) was stored on ice for HPLC analysis. After the 20 min incubation, the synaptosomes were pelleted by centrifugation (14,000 × g for 15 sec) in a refrigerated centrifuge (4°C). The pelleted synaptosomes were homogenized in 200 μl of 2% (vol/vol) Triton X-100 to determine total lactate dehydrogenase activity and protein content. The remaining bathing solution was used to quantify lactate dehydrogenase activity, which was always lower than 3% of total lactate dehydrogenase activity in the CA1 synaptosomes.

HPLC analysis. Separation of nucleotides and their degradation products was performed by ion-pair reverse-phase HPLC analysis of nonextracted samples (20 μl) as described previously (Cascalheira and Sebastião, 1992), with minor modifications, using a Beckman 126 solvent delivery module equipped with a 210A sample injection valve with a 20 μl loop coupled with a Beckman 166 UV detector set at 254 nm, both connected to a Compaq 286e computer using the Gold software package. Separations were performed at room temperature with LiChrospher 100 RP-18 (5 μm) cartridges (Merck, Darmstadt, Germany) fitted into a Manu-cart holder (Merck). The columns were protected by LiChrospher 60 RP-select B (5 μm) pre-columns (Merck). The eluent, pH 6.0, was composed of KH2PO4 60 mm, tetrabutylammonium 5 mm, and 5–35% (vol/vol) methanol. A 10 min linear gradient from 5 to 35% (vol/vol) methanol was performed, starting after sample injection, with a constant flow rate of 1.5 ml/min. Under these conditions, the retention times of the substances used as standards were as follows: hypoxanthine (1.2 min), inosine (1.7 min), adenosine (3.6 min), AMP (4.7 min), AOPCP (5.8 min), ADP (6.8 min), α,β-methylene-ATP (7.8 min), β,γ-imido-ATP (7.9 min), β,γ-methylene-ATP (8.0 min), ATP (8.3 min), 2-methylthio-AMP (9.8 min), ATPγS (10.7 min), 2-methylthio-ADP (10.9 min), and 2-methylthio-ATP (11.6 min). Linear calibration curves were obtained for each substance after electronic integration of the peak area for each substance (1–1000 pmol in 20 μl injected). Identification of the peaks was performed by comparison of relative retention times with standards.

Kinetic analysis. The concentrations of the products at the different times of sample collection were corrected by subtracting the concentrations of products eventually present at zero time. The concentration of products, in samples collected from the same batch of slices or synaptosomes, incubated without adding substrate, were also subtracted for correction of spontaneous release. Plots of concentration of the substrate and products as a function of time (progress curves) were constructed. The relative extent of catabolism of ATP analogs was compared by calculating the amount of substrate catabolized after 20 min. The specific activity of ecto-ATPase activity in hippocampal preparations was calculated by linear regression of the decrease of the amount of extracellular ATP during the first 5 min of catabolism, normalized per milligram of protein. To test the effects ofp-nitrophenylphosphate on the catabolism of ATP analogs, progress curves of ATP analogs were performed in parallel batches of slices or synaptosomes from the same group of animals, one in the absence and the other in the presence ofp-nitrophenylphosphate (1 mm).

The extracellular catabolism of AMP in the presence of ATP analogs was analyzed as described previously (Cunha et al., 1992).

Other determinations. Lactate dehydrogenase (EC 1.1.1.27) activity was assayed by the method of Keiding et al. (1974). Protein concentration of the slices and of the synaptosomes was determined by the Bradford method, modified according to Spector (1978).

Statistical calculations. The values are presented as mean ± SEM, with n being the number of animals or different groups of animals used. The significance of the differences between the means was calculated by a one-way ANOVA followed by a paired Student’s t test or a Dunnett’s test. pvalues of <0.05 were considered to represent significant differences.

RESULTS

Effects of ATP analogs on hippocampal synaptic transmission

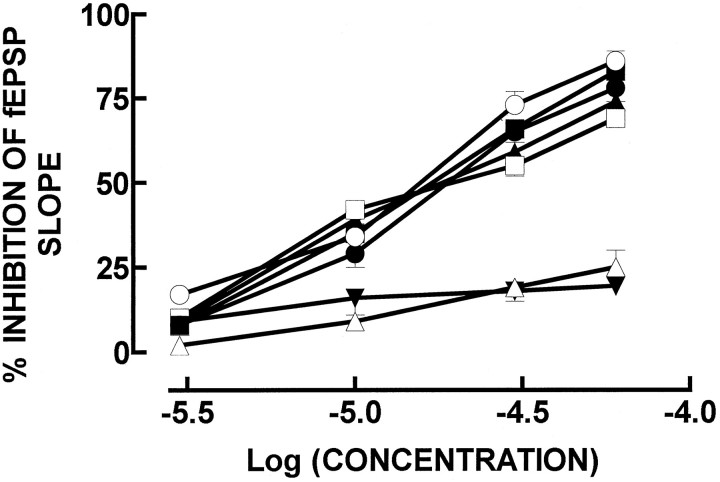

ATP, in the micromolar range, inhibited in a concentration-dependent manner the fEPSP slope in stimulated CA1 pyramid synapses, with an IC50 of 20 ± 3 μm (n = 4) and was slightly less potent than adenosine (IC50 of 12 ± 2 μm;n = 4). ATP analogs substituted in the γ-phosphorus also inhibited synaptic transmission in a concentration-dependent manner (Fig. 1); the IC50values were 17 ± 3 μm (n = 4) for ATPγS, 22 ± 5 μm (n = 4) for β,γ-imido-ATP, and 20 ± 2 μm (n= 4) for β,γ-methylene-ATP. α,β-methylene-ATP, an ATP analog substituted in the α-phosphorus, was less potent than ATP (Fig. 1), with a maximal inhibition of 19 ± 2% at 60 μm(n = 4; p < 0.05). ATP analogs substituted in the purine moiety, namely in the ribose ring, such as 2-methylthio-ATP (Fig. 1), were also less potent than ATP, with a maximum inhibition of 25 ± 5% at 60 μm(n = 4; p < 0.05), or even devoid of effects, such as 2′-dATP (10–100 μm; n = 2).

Fig. 1.

Inhibition of the fEPSP slope, recorded extracellularly in hippocampal CA1 pyramids, by exogenously added adenosine (○), ATP (•), ATPγS (▪), β,γ-imido-ATP (□), β,γ-methylene-ATP (▴), 2-methylthio-ATP (▵), and α,β-methylene-ATP (▾). The ordinates represent the percentage of inhibition of fEPSP slope produced by adenosine, ATP, or ATP analogs in relation to the fEPSP slope in control conditions (i.e., in the absence of any added drug to the perfusion solution). 0% corresponds to the fEPSP slope in control conditions (i.e., without any added drug), and 100% corresponds to blockade of fEPSP. The results are mean ± SEM of two to five experiments. The SEMs are shown when they exceed the symbols in size.

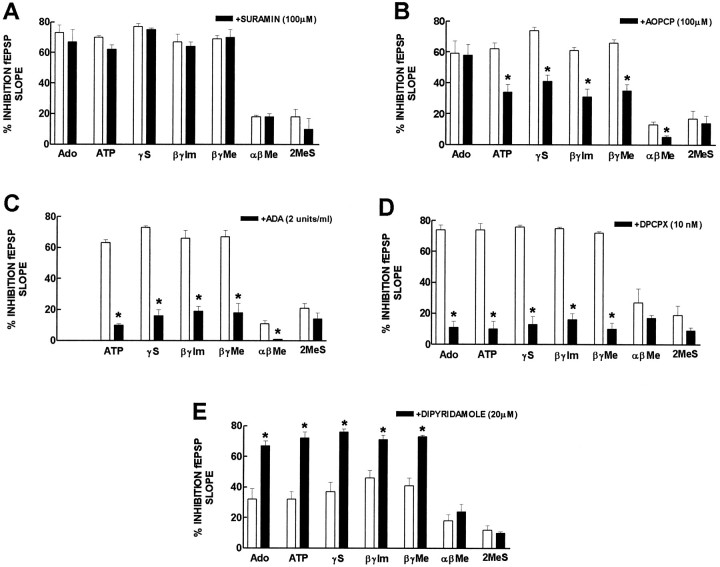

As shown in Figure 2, the inhibitory effect of ATP and of ATP analogs (30 μm) was not modified (n = 2–3) by the P2 receptor antagonist suramin (100 μm). The inhibitory effect of ATP and of γ-phosphorus-substituted ATP analogs was also virtually unaffected by the P2 receptor antagonists, reactive blue 2 (30 μm; n = 2), or PPADS (30 μm; n = 1). By itself, suramin (100 μm; n = 3), reactive blue 2 (30 μm; n = 2), and PPADS (30 μm; n = 1) caused a 16 ± 1%, 21 ± 4%, and 15% inhibition of fEPSP slope, respectively.

Fig. 2.

Modification of the inhibition by adenosine, ATP, and ATP analogs of fEPSPs by 100 μm suramin, a P2 receptor antagonist (A), by 100 μm α,β-methylene ADP (AOPCP), an inhibitor of ecto-5′-nucleotidase (B), by 2 U/ml adenosine deaminase (ADA), the enzyme that converts adenosine into its inactive metabolite, inosine (C), by 10 nm1,3-dipropyl-8-cyclopentylxanthine (DPCPX), an adenosine A1receptor antagonist (D), and by 20 μm dipyridamole, an inhibitor of adenosine uptake (E). The ordinates represent the percentage inhibition of fEPSP slope by adenosine or ATP, ATPγS (γS), β,γ-imido-ATP (β,γ-Im), β,γ-methylene-ATP (β,γ-Me), α, β-methylene-ATP (αβMe), and 2-methylthio-ATP (2MeS) in the absence (open bars) and presence (filled bars) of the drugs indicated in each panel. 0% corresponds to the fEPSP slope in control conditions (i.e., without any added drug or after addition of suramin, AOPCP, adenosine deaminase, DPCPX, or dipyridamole), and 100% corresponds to blockade of fEPSPs. In each experiment, suramin, AOPCP, adenosine deaminase, DPCPX, or dipyridamole were applied to the preparations 30–45 min before the effect of adenosine, ATP, or ATP analogs was tested in their presence. The effect of adenosine, ATP, or ATP analogs in the absence and presence of suramin, AOPCP, adenosine deaminase, DPCPX, or dipyridamole was always compared in the same experiment. * p < 0.05 (paired Student’s t test) when comparing with the effect of adenosine, ATP, or ATP analogs alone. The results are mean ± SEM of three to four experiments. The SEMs are shown when they exceed the symbols in size.

In contrast, the inhibitor of ecto-5′-nucleotidase, AOPCP (100 μm), inhibited by 42–49% (n = 3) the inhibitory effect of ATP and γ-substituted ATP analogs (Fig. 2). This effect was not attributable to any effect of AOPCP per se on purine receptors because the inhibitory effect of adenosine (30 μm) was not modified by 100 μm AOPCP (n = 3). As described previously (Cunha et al., 1996b), AOPCP (100 μm) by itself caused a 18 ± 2% inhibition of fEPSP slope (n = 3).

That the effect of ATP and γ-phosphorus-substituted ATP analogs depended mainly on the formation of extracellular adenosine was also supported by the observation that adenosine deaminase (2 U/ml), which converts adenosine into its inactive metabolite inosine, inhibited by 74–85% (n = 3–4) the inhibitory effect of ATP and γ-substituted ATP analogs (30 μm) (Fig. 2). By itself, adenosine deaminase (2 U/ml) caused a 23 ± 2% increase of fEPSP slope (n = 4), which is compatible with an inhibitory “tonus” by endogenous adenosine (Cunha et al., 1996b).

The requirement for activation of inhibitory adenosine A1receptors to observe the inhibitory effect of ATP and γ-phosphorus-substituted ATP analogs was suggested from the observation that 10 nm DPCPX, an adenosine A1receptor antagonist that blocks the inhibitory effect of maximally effective concentrations of 2-chloroadenosine in the hippocampus (Sebastião et al., 1990), inhibited by 80–93% (n = 3–4) the inhibitory effect of ATP and γ-substituted ATP analogs (30 μm) (Fig. 2). By itself, DPCPX (10 nm) caused a 19 ± 3% increase of fEPSP slope (n = 4).

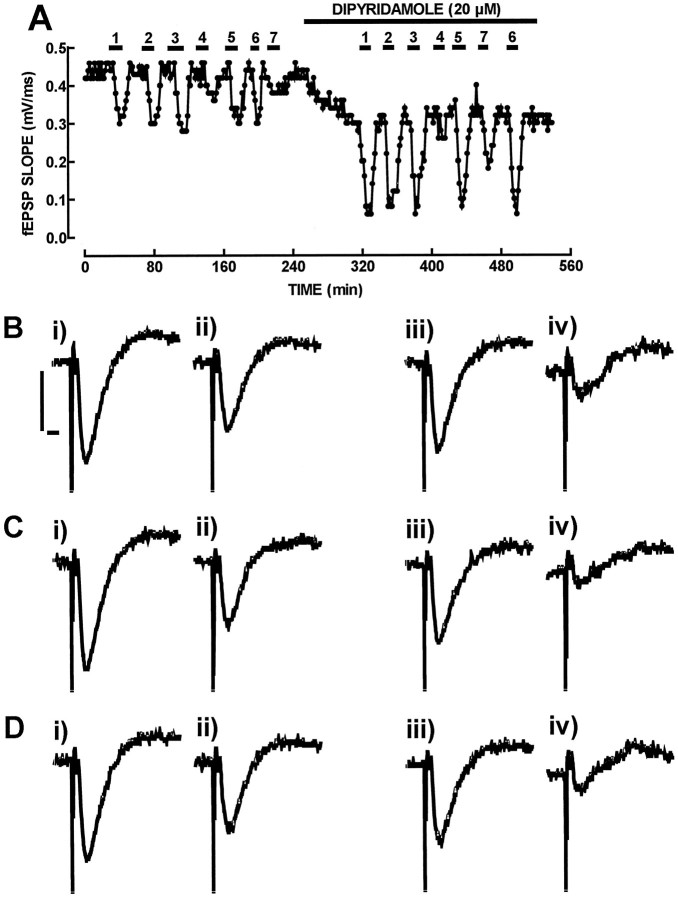

Stronger support for the involvement of extracellular adenosine formation as a main requirement for the inhibitory effect of ATP and γ-substituted ATP analogs was derived from the observation that dipyridamole (20 μm), which supramaximally inhibits adenosine uptake (Morgan and Marangos, 1987), potentiated the inhibitory effect of ATP and γ-phosphorus-substituted ATP analogs (10 μm) (Fig. 3). Thus, dipyridamole (20 μm) potentiated by 92–124% (n = 3–4) the inhibitory effect of ATP and γ-substituted ATP analogs (10 μm), and it potentiated the inhibitory effect of adenosine (10 μm) by a similar amount (113 ± 26%; n = 4). By itself, dipyridamole (20 μm) caused a 30 ± 5% inhibition of fEPSP slope (n = 4), probably by the ability of dipyridamole to increase the endogenous levels of extracellular adenosine (Mitchell et al., 1993).

Fig. 3.

Effect of the inhibitor of adenosine uptake, dipyridamole to potentiate the inhibitory effect of ATPγS (1), β,γ-imido-ATP (2), β,γ-methylene-ATP (3), 2-methylthio-ATP (4), ATP (5), adenosine (6), and α,β-methylene-ATP (7) on fEPSP slope. In A is shown the time course of the slope of averages of eight consecutive fEPSPs recorded from the CA1 area of the hippocampus. The hippocampal slice was perfused with adenosine, ATP, or ATP analogs (10 μm) either in the absence or in the presence of dipyridamole (20 μm), as shown in the top bars. In B, C, andD are shown recordings of fEPSPs, corresponding to the absence of any added drug in the perfusion medium (i inB, C, and D), the presence of ATP (B, ii), ATPγS (C, ii), and adenosine (D,ii), the presence of dipyridamole (iii inB, C, and D), the simultaneous presence of dipyridamole and ATP (B,iv), the simultaneous presence of dipyridamole and ATPγS (C, iv), and the simultaneous presence of dipyridamole and adenosine (D,iv). Each recording is composed of a stimulus artifact followed by the presynaptic volley and the fEPSP and corresponds to the average of eight consecutive responses. Calibration bars (shown inB for B–D): 500 μV, 5 msec. Note that dipyridamole (20 μm) potentiated to a similar extent the inhibitory effect of γ-phosphorus-substituted ATP analogs (1, 2, and 3), ATP (5), and adenosine (6), whereas the inhibitory effect of 2-methylthio-ATP (4) and α,β-methylene-ATP (7) was not modified appreciably.

The small inhibitory effect of α,β-methylene-ATP (30 μm) was more potently inhibited (65 ± 5%;n = 3) by 100 μm AOPCP than the inhibitory effect of γ-phosphorus-substituted ATP analogs, less inhibited by 10 nm DPCPX (60 ± 5%; n= 3), and completely prevented (n = 2) by 2 U/ml adenosine deaminase (Fig. 2). The potentiation of the inhibitory effect of α,β-methylene-ATP (10 μm) by 20 μmdipyridamole (32 ± 15%; n = 3) was also lower than that observed for γ-phosphorus-substituted ATP analogs (Fig.2).

The small inhibitory effect of 2-methylthio-ATP (30 μm) was also less inhibited by 2 U/ml adenosine deaminase (44 ± 5%;n = 3) and by 10 nm DPCPX (67 ± 6%;n = 2) than the inhibitory effect of γ-phosphorus-substituted ATP analogs and was not consistently modified by 100 μm AOPCP (n = 3) or by 20 μm dipyridamole (n = 3) (Fig. 2).

Catabolism of ATP analogs in hippocampal CA1 slices and synaptosomes

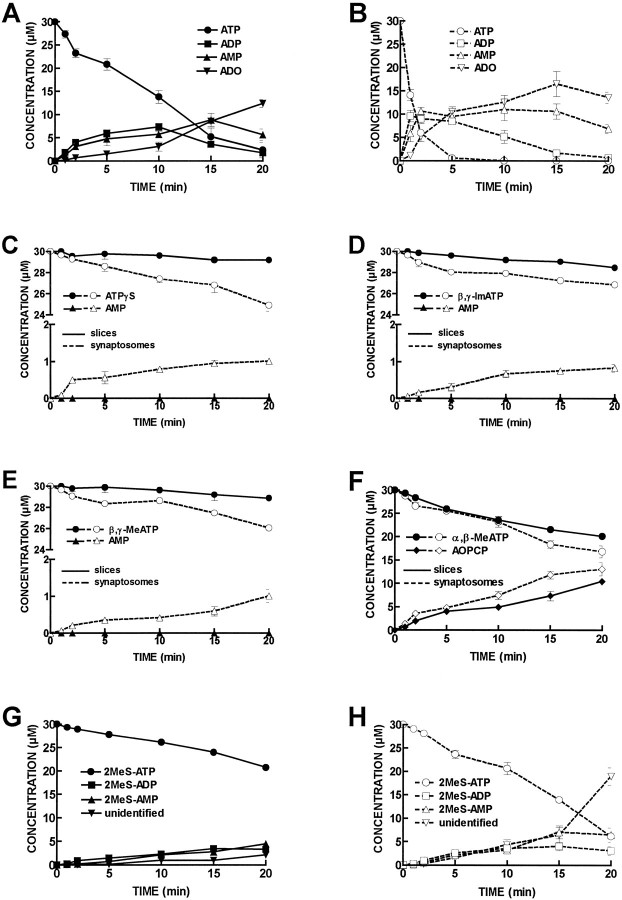

As shown in Figure4A, extracellular ATP (30 μm) was catabolized by hippocampal CA1 slices (0.75 ± 0.02 mg protein), with a half-degradation of 8 ± 2 min (n = 5). The ATP metabolites detected in the bath were ADP, the concentration of which reached a maximum of 7 ± 2 μm at 10 min; AMP, the concentration of which reached a maximum of 9 ± 1 μm at 15 min; and adenosine, the maximum concentration of which (12.5 ± 0.9 μm) was reached at 20 min.

Fig. 4.

Progress curves of ATP and ATP analog catabolism in CA1 hippocampal slices and synaptosomes. ATP or ATP analogs (30 μm) were incubated at zero time with CA1 slices or synaptosomes. Samples (50 μl) were collected from the bath (600 μl) at the times indicated in the abscissa and analyzed by HPLC. InA is shown the catabolism of ATP (•) into ADP (▪), AMP (▴), and adenosine (▾) in CA1 slices. In B is shown the catabolism of ATP (○) into ADP (□), AMP (▵), and adenosine (▿) in CA1 synaptosomes. In C is shown the catabolism of ATPγS (•, ○) into AMP (▴,▵) in CA1 slices (filled symbols, filled lines) and CA1 synaptosomes (open symbols, broken lines). InD is shown the catabolism of β,γ-imido-ATP (•, ○) into AMP (▴,▵) in CA1 slices (filled symbols, filled lines) and CA1 synaptosomes (open symbols, broken lines). In E is shown the catabolism of β,γ-methylene-ATP (•, ○) into AMP (▴,▵) in CA1 slices (filled symbols, filled lines) and CA1 synaptosomes (open symbols, broken lines). InF is shown the catabolism of α,β-methylene ATP (•, ○) into α,β-methylene ADP (♦, ⋄) in CA1 slices (filled symbols, filled lines) and CA1 synaptosomes (open symbols, broken lines). InG is shown the catabolism of 2-methylthio-ATP (•) into 2-methylthio-ADP (▪), 2-methylthio-AMP (▴) and into an unidentified compound (▾) in CA1 slices. In H is shown the catabolism of 2-methylthio-ATP (○) into 2-methylthio-ADP (□), 2-methylthio-AMP (▵) and into an unidentified compound (▿) in CA1 synaptosomes. Each point is the average of four to five experiments. The vertical bars represent the SEM and are shown when they exceed the symbols in size. The concentrations of inosine and adenosine detected under control conditions, without addition of initial substrate, were subtracted. The concentration of any purine metabolite present at time 0 was also subtracted.

The catabolism of ATP (30 μm) showed a similar pattern in hippocampal CA1 synaptosomes (2.6 ± 0.2 mg protein;n = 4), with a half-degradation time of 0.8 ± 0.1 min. The ATP metabolites detected in the bath were ADP, the concentration of which reached a maximum of 10 ± 1 μm at 1 min; AMP, the concentration of which reached a maximum of 11 ± 2 μm at 10 min; and adenosine, the concentration of which reached a maximum of 17 ± 3 μm at 15 min (Fig. 4B).

Surprisingly, the extent of catabolism of γ-phosphorus-substituted ATP analogs (30 μm) was not significant in hippocampal CA1 slices (n = 5). The concentration of these ATP analogs did not change significantly during the 20 min incubation period, nor did any purine metabolite appear in the bath in measurable amounts (Fig. 4C–E).

In contrast, γ-phosphorus-substituted ATP analogs (30 μm) were catabolized in hippocampal CA1 synaptosomes (Fig. 4C–E). After 20 min, 5.1 ± 0.5 μmATPγS had been catabolized (n = 4), and 1.0 ± 0.1 μm AMP appeared in the bath; 3 ± 1 μm β,γ-imido-ATP had been catabolized (n = 4), and 0.8 ± 0.1 μm AMP appeared in the bath after 20 min; and 4.0 ± 0.2 μmβ,γ-methylene-ATP had been catabolized (n = 4), and 1.0 ± 0.2 μm AMP appeared in the bath after 20 min. In hippocampal CA1 synaptosomes, when ATPγS, β,γ-imido-ATP, or β,γ-methylene-ATP were assayed as initial substrates, ADP never appeared in the bath in measurable amounts. The presence ofp-nitrophenylphosphate (1 mm) did not appreciably change the amounts of ATPγS, β,γ-imido-ATP or β,γ-methylene-ATP catabolized after 20 min, nor didp-nitrophenylphosphate appreciably change the amounts of AMP formed as a result of γ-phosphorus-substituted ATP analogs (30 μm) catabolism.

When α,β-methylene-ATP (30 μm) was used as initial substrate, the only metabolite appearing in the bath was AOPCP, which reached a maximum concentration of 10.4 ± 0.7 μm in CA1 slices (n = 5) and 13 ± 1 μm in CA1 synaptosomes (n = 4) (Fig.4F).

2-Methylthio-ATP (30 μm) was catabolized in both CA1 slices (Fig. 4G) and CA1 synaptosomes (Fig.4H). During the 20 min incubation period, 9.3 ± 0.6 μm and 13.9 ± 0.6 μm2-methylthio-ATP were catabolized in both CA1 slices (n= 5) and synaptosomes (n = 4), respectively. 2-Methylthio-ATP was converted into 2-methylthio-ADP and 2-methylthio-AMP and in another nonidentified product with a retention time of 7.9 min, which might correspond to 2-methylthio-adenosine, although no standard is commercially available to identify this peak (Fig. 4G,H).

The catabolism of AMP (30 μm) resulted in the formation of adenosine, inosine, and hypoxanthine, as described previously (Cunha et al., 1992). The rate of AMP catabolism during the first 5 min of incubation was decreased by 12–21% by α,β-methylene-ATP (30 μm; n = 2), and was not modified by ATPγS, β,γ-imido-ATP, or β,γ-methylene-ATP (30 μm; n = 2).

DISCUSSION

The present results show that the inhibition of synaptic transmission in Schaffer fibers/CA1 pyramid synapses of rat hippocampal slices by ATP and γ-phosphorus-substituted ATP analogs is mediated by activation of inhibitory A1 adenosine receptors after extracellular catabolism of these nucleotides into adenosine by ecto-nucleotidases. Thus, the inhibitory effect on synaptic transmission of ATP and γ-substituted ATP analogs was inhibited (1) by AOPCP, an inhibitor of ecto-5′-nucleotidase, the enzyme that forms adenosine from extracellular adenine nucleotides, (2) by adenosine deaminase, which converts adenosine into its inactive metabolite inosine, and (3) by DPCPX, an adenosine A1receptor antagonist, whereas (4) it was potentiated by the adenosine uptake inhibitor dipyridamole.

The inability of the nucleotide P2 receptor antagonists suramin reactive blue 2 and PPADS to modify the inhibitory effect of ATP and γ-substituted ATP analogs further supports the idea that extracellular catabolism of ATP and γ-substituted ATP analogs into adenosine is mainly responsible for this inhibitory effect. We tested three chemically distinct P2 antagonists to exclude the possibility that diffusion barriers might exist to access P2 receptors. It should be stressed, however, that the possibility of P2 receptors having a role in the hippocampus cannot be excluded. Indeed, P2 receptors are expressed in the hippocampus (Kidd et al., 1995; Buell et al., 1996;Collo et al., 1996), the effects of ATP on synaptic transmission in the hippocampus are not completely prevented by pharmacological tools interfering with adenosine neuromodulation (Lee et al., 1981; Cunha et al., 1996b), and antagonists of P2 receptors produce effects in hippocampal preparations (Motin and Bennett, 1995), although they also directly affect ionotropic GABA and glutamate receptors (Nakazawa et al., 1995) and modify ecto-nucleotidase activity (Ziganshin et al., 1996). Also, P2 receptors insensitive to the commonly used P2 receptor antagonists have been described (Buell et al., 1996). Thus, it is possible that at higher frequencies of stimulation, for instance, P2 receptors may have a physiological role in modulating synaptic transmission in the hippocampus, as has been shown to occur with ecto-protein kinases (Wieraszko, 1996); although at lower frequencies of stimulation, as used in the present work, the effect of ATP is mostly mediated by A1 receptors after extracellular catabolism into adenosine by ecto-nucleotidases. Previous work also concluded that the absence of P2 receptor-mediated modulation of transmission in Schaffer fibers/CA1 pyramid synapses of rat hippocampal slices based on the use of ATP analogs derived from the inactive enantiomer of adenosinel-adenosine (Stone and Cusack, 1989).

The discrepancy between the stability of γ-substituted ATP analogs in an innervated skeletal muscle preparation and the modification of their action on neuromuscular transmission by modifiers of adenosine metabolism lead to the proposal of localized catabolism of adenine nucleotides coupled to activation of inhibitory adenosine A1 receptors (Bruns, 1990; Cascalheira and Sebastião, 1992). This discrepancy was also observed in the present work, i.e., no measurable extracellular metabolism of γ-substituted ATP analogs seems to occur in hippocampal slices, whereas the functional assays revealed an adenosine-mediated action of these nucleotides. The channeling of the product of ecto-nucleotidases activity, adenosine, to A1 receptors allows us to understand how a very low rate of catabolism of γ-substituted ATP analogs might allow effective activation of adenosine A1 receptors. Although very low amounts of adenosine are formed, substrate channeling allows a high local concentration of adenosine to be reached in the surroundings of A1 receptors. This possibility, which was not tested or considered in several studies on the physiological effects mediated by extracellular ATP, has lead to the proposal that γ-substituted ATP analogs might directly activate adenosine A1 receptors (Hourani et al., 1991; Bailey et al., 1992; Piper and Hollingsworth, 1996), although binding studies show that γ-substituted ATP analogs are not effective displacers of adenosine A1 receptor binding (Williams and Braunwalder, 1986). The existence of substrate channeling properties in the delivery of adenosine formed from ecto-nucleotidases and the existence of a strong gradient for extracellular adenosine in a synapse (Cunha, 1997) could also explain the greater potency of ATP and ATP analogs compared with that of adenosine to inhibit neurotransmitter release or synaptic transmission (Silinsky and Ginsborg, 1983; Shinozuka et al., 1990; Cunha et al., 1994c), which was the basis for proposing the existence of a P3 receptor (Shinozuka et al., 1990; Cunha et al., 1994c) (but see Saitoh and Nakata, 1996). Thus, if adenosine is effectively removed by the nucleoside transport system before reaching adenosine A1 receptors and adenosine formed from extracellular adenine nucleotides catabolism is preferentially delivered to adenosine A1 receptor, it is conceivable that ATP derivatives may have a greater potency than adenosine itself, although both act via adenosine A1 receptor activation. Awareness is growing (Harden et al., 1997) that to establish an effect of ATP as such it is essential to show that removal of extracellular adenosine, inhibition of the ecto-nucleotidase cascade, and blockade of A1-mediated responses does not occlude ATP effect. Only after the possibility is excluded that the effect of ATP is not mediated by localized extracellular catabolism into adenosine by the ecto-nucleotidase cascade will it be possible to consider an effect mediated by ATP as such.

The extracellular catabolism of ATP by ecto-nucleotidases was qualitatively similar in hippocampal CA1 slices and synaptosomes, with the apparent sequential formation of ADP, AMP, and adenosine. Quantitatively, the specific activity of ATP catabolism was higher in synaptosomes than in slices, as had been observed previously in a particular synaptosomal fraction (Cunha and Sebastião, 1992). ATP analogs with substitutions in γ-phosphorus were also catabolized in CA1 synaptosomes, but not in slices, although at a lower rate than ATP catabolism. However, the extracellular catabolism of γ-phosphorus-substituted ATP analogs was different from that of ATP, because the only metabolite detected in the bath was AMP, whereas ADP was never detected. This pattern would be expected if an ecto-ATP pyrophosphatase (EC 3.6.1.8) instead of an ecto-ATP diphosphohydrolase (Plesner, 1995) would be catabolizing extracellular ATP, because the involvement of nonspecific phosphatases was excluded on the basis of the absence of effect of p-nitrophenylphosphate. The lack of commercially available inhibitors of ecto-ATP pyrophosphatase precludes direct testing of this hypothesis. The ability to detect catabolism of ATP analogs in synaptosomes but not in slices probably reflects a higher specific activity of catabolism of γ-substituted ATP analogs in synaptosomes. It is expected that localized catabolism of γ-substituted ATP analogs might occur in the slices, because the synaptosomes were obtained from the slices, but the rate of catabolism may be below detection limit.

It is interesting to note that ATP analogs substituted in the α-phosphorus or in the purine ring displayed a functional behavior distinct from that of γ-substituted ATP analogs. Thus, the modulators of adenosine metabolism/effects (adenosine deaminase, DPCPX) affected the action of α,β-methylene-ATP the same as they modify the action of AOPCP in the hippocampus (Cunha et al., 1996b). The observations that a long (30 min) preincubation with α,β-methylene-ATP (100 μm) reduces the inhibitory effect of ATP (30 μm) on synaptic transmission by 16–21% (n = 2; data not shown) and that α,β-methylene-ATP (30 μm) inhibited extracellular AMP catabolism further supports the possibility that the effect of this α-substituted ATP analog is caused by direct or indirect (after conversion into AOPCP) (compare Fig. 4F) inhibition of ecto-5′-nucleotidase. Although presynaptic inhibition of neurotransmitter by activation of P2Y receptors has been proposed (von Kügelgen, 1996), the effect of 2-methylthio-ATP, which was smaller than that of the other ATP analogs, is currently difficult to interpret with the biochemical and pharmacological approaches used.

In conclusion, the present results demonstrate that ATP and γ-phosphorus-substituted ATP analogs have to be extracellularly converted into adenosine to exert their inhibitory effects on synaptic transmission in the hippocampus, and they highlight the importance of channeling adenosine to adenosine A1 receptors as a means for adenine nucleotides to inhibit synaptic transmission.

Footnotes

This work was supported by Junta Nacional de Investigaçao Cientifica e Tecnologica, Praxis XXI, Gulbenkian Foundation, and European Union (BIOMED 2 programme). We thank Dr. H. Zimmermann for critically reviewing this manuscript.

Correspondence should be addressed to R. A.Cunha, Laboratory of Neurosciences, Faculty of Medicine, University of Lisbon, Avenida Professor Egas Moniz, 1600 Lisboa, Portugal.

REFERENCES

- 1.Bailey SJ, Hickman D, Hourani SMO. Characterization of the P1-purinoceptors mediating contraction of the rat colon muscularis mucosae. Br J Pharmacol. 1992;105:400–404. doi: 10.1111/j.1476-5381.1992.tb14265.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Bruns RF. Adenosine receptors. Roles and pharmacology. Ann NY Acad Sci. 1990;603:211–226. doi: 10.1111/j.1749-6632.1990.tb37674.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Buell G, Lewis C, Collo G, North RA, Surprenant A. An antagonist-insensitive P2X receptor expressed in epithelia and brain. EMBO J. 1996;15:55–62. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Cascalheira JF, Sebastião AM. Adenine nucleotide analogues, including γ-phosphate-substituted analogues, are metabolised extracellularly in innervated frog sartorius muscle. Eur J Pharmacol. 1992;222:49–59. doi: 10.1016/0014-2999(92)90462-d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Collo G, North RA, Kawashima E, Merlo-Pich E, Neidhart S, Surprenant A, Buell G. Cloning of P2X5 and P2X6 receptors and the distribution and properties of an extended family of ATP-gated ion channels. J Neurosci. 1996;16:2495–2507. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.16-08-02495.1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Cunha RA, Sebastião AM. Ecto-ATPase activity in cholinergic nerve terminals of the hippocampus and of the cerebral cortex of the rat. Neurochem Int. 1992;21[Suppl]:A12. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-4159.1992.tb09420.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Cunha RA, Sebastião AM, Ribeiro JA. Ecto-5′-nucleotidase is associated with cholinergic nerve terminals in the hippocampus but not in the cerebral cortex of the rat. J Neurochem. 1992;59:657–666. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-4159.1992.tb09420.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Cunha RA, Johansson B, van der Ploeg I, Sebastião AM, Ribeiro JA, Fredholm BB. Evidence for functionally important adenosine A2a receptors in the rat hippocampus. Brain Res. 1994a;649:208–216. doi: 10.1016/0006-8993(94)91066-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Cunha RA, Milusheva E, Vizi ES, Ribeiro JA, Sebastião AM. Excitatory and inhibitory effects of A1 and A2A adenosine receptor activation on the electrically evoked [3H]acetylcholine release from different areas of the rat hippocampus. J Neurochem. 1994b;63:207–214. doi: 10.1046/j.1471-4159.1994.63010207.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Cunha RA, Ribeiro JA, Sebastião AM. Purinergic modulation of the evoked release of [3H]acetylcholine from the hippocampus and cerebral cortex of the rat: role of the ectonucleotidases. Eur J Neurosci. 1994c;6:33–42. doi: 10.1111/j.1460-9568.1994.tb00245.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Cunha RA, Vizi ES, Ribeiro JA, Sebastião AM. Preferential release of ATP and its extracellular catabolism as a source of adenosine upon high- but not low-frequency stimulation of rat hippocampal slices. J Neurochem. 1996a;67:2180–2187. doi: 10.1046/j.1471-4159.1996.67052180.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Cunha RA, Correia-de-Sá P, Sebastião AM, Ribeiro JA. Preferential activation of excitatory adenosine receptors at rat hippocampal and neuromuscular synapses by adenosine formed from released adenine nucleotides. Br J Pharmacol. 1996b;119:253–260. doi: 10.1111/j.1476-5381.1996.tb15979.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Cunha RA. Release of ATP and adenosine and formation of extracellular adenosine in the hippocampus. In: Okada Y, editor. Excerpta Medica International Congress series. Elsevier Science; Amsterdam: 1997. pp. 135–142. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Fredholm BB, Abbracchio MP, Burnstock G, Daly JW, Harden TD, Jacobson KA, Leff P, Williams M. Nomenclature and classification of purinoceptors. Pharmacol Rev. 1994;46:143–156. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Harden TK, Lazarowski ER, Boucher RC. Release, metabolism and interconversion of adenine and uridine nucleotides: implications for G protein-coupled P2 receptor agonist selectivity. Trends Pharmacol. 1997;18:43–46. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Hourani SMO, Bailey SJ, Nicholls J, Kitchen I. Direct effect of adenylyl 5′-(β,γ-methylene)diphosphonate, a stable ATP analogue, on relaxant P1-purinoceptors in smooth muscle. Br J Pharmacol. 1991;104:685–690. doi: 10.1111/j.1476-5381.1991.tb12489.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Inoue K, Koizumi S, Ueno S. Implication of ATP receptors in brain functions. Prog Neurobiol. 1996;50:483–492. doi: 10.1016/s0301-0082(96)00037-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Keiding R, Horder M, Gerhart W, Pitkanen E, Tehhunen R, Stömme JH, Theorderson L, Waldenström J, Tryding N, Westlund L. Recommended methods for the determination of four enzymes in the blood. Scand J Clin Lab Invest. 1974;33:291–306. doi: 10.1080/00365517409082499. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Kidd EJ, Grahames CBA, Simon J, Michel AD, Barnard EA, Humphrey PPA. Localization of P2X purinoceptor transcripts in the rat nervous system. Mol Pharmacol. 1995;48:569–573. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Lee KS, Schubert P, Emmert H, Kreutzberg GW. Effect of adenosine versus adenine nucleotides on evoked potentials in a rat hippocampal slice preparation. Neurosci Lett. 1981;23:309–314. doi: 10.1016/0304-3940(81)90016-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Mitchell JB, Lupica CR, Dunwiddie TV. Activity-dependent release of endogenous adenosine modulates synaptic responses in the rat hippocampus. J Neurosci. 1993;13:3439–3447. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.13-08-03439.1993. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Morgan PF, Marangos PJ. Comparative aspects of nitrobenzylthioinosine and dipyridamole inhibition of adenosine accumulation in rat guinea pig synaptoneurosomes. Neurochem Int. 1987;11:339–356. doi: 10.1016/0197-0186(87)90055-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Motin L, Bennett MR. Effect of P2-purinoceptor antagonists on glutamatergic transmission in the rat hippocampus. Br J Pharmacol. 1995;115:1276–1280. doi: 10.1111/j.1476-5381.1995.tb15036.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Nakazawa K, Inoue K, Ito K, Koizumi S, Inoue K. Inhibition by suramin and reactive blue 2 of GABA and glutamate receptor channels in rat hippocampal neurons. Naunyn Schmiedebergs Arch Pharmacol. 1995;351:202–208. doi: 10.1007/BF00169334. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Piper AS, Hollingsworth M. ATP and β,γ-methylene ATP produce relaxation of guinea-pig isolated trachealis muscle via actions at P1 purinoceptors. Eur J Pharmacol. 1996;307:183–189. doi: 10.1016/0014-2999(96)00237-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Plesner L. Ecto-ATPases: identities and functions. Int Rev Cytol. 1995;158:141–214. doi: 10.1016/s0074-7696(08)62487-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Saitoh Y, Nakata H. Photoaffinity labeling of a P3 purinoceptor-like protein purified from rat brain membranes. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 1996;219:469–474. doi: 10.1006/bbrc.1996.0257. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Sebastião AM, Stone TW, Ribeiro JA. The inhibitory adenosine receptor at the neuromuscular junction and hippocampus of the rat: antagonism by 1,3,8-substituted xanthines. Br J Pharmacol. 1990;101:453–459. doi: 10.1111/j.1476-5381.1990.tb12729.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Shinozuka K, Bjur RA, Westfall DP. Effect of α,β-methylene ATP on the prejunctional purinoceptors of the sympathetic nerves of the rat caudal artery. J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 1990;254:900–904. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Silinsky EM, Ginsborg BL. Inhibition of acetylcholine release from preganglionic frog nerves by ATP but not adenosine. Nature. 1983;305:327–328. doi: 10.1038/305327a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Spector T. Refinement of the Coomassie Blue method of protein quantification. A simple and linear spectrophotometric assay for < 0.5 to 50 μg of protein. Anal Biochem. 1978;86:142–146. doi: 10.1016/0003-2697(78)90327-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Stone TW, Cusack NJ. Absence of P2-purinoceptors in hippocampal pathways. Br J Pharmacol. 1989;97:631–635. doi: 10.1111/j.1476-5381.1989.tb11996.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Terrian DM, Hernandez PG, Rea MA, Peters RI. ATP release, adenosine formation, and modulation of dynorphin and glutamic acid release by adenosine analogues in rat hippocampal mossy fiber synaptosomes. J Neurochem. 1989;53:1390–1399. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-4159.1989.tb08529.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.von Kügelgen I. Modulation of neural ATP release through presynaptic receptors. Semin Neurosci. 1996;8:247–257. [Google Scholar]

- 35.Wieraszko A. Extracellular ATP as a neurotransmitter: its role in synaptic plasticity in the hippocampus. Acta Neurobiol Exp. 1996;56:637–648. doi: 10.55782/ane-1996-1168. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Williams M, Braunwalder A. Effects of purine nucleotides on the binding of [3H] cyclopentyladenosine to adenosine A1 receptors in rat brain membranes. J Neurochem. 1986;47:88–97. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-4159.1986.tb02835.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Ziganshin AU, Ziganshina LE, King BF, Pintor J, Burnstock G. Effects of P2-purinoceptor antagonists on degradation of adenine nucleotides by ecto-nucleotidases in folliculated oocytes of Xenopus laevis. Biochem Pharmacol. 1996;51:897–901. doi: 10.1016/0006-2952(95)02252-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Zimmermann H. Signalling via ATP in the nervous system. Trends Neurosci. 1994;17:420–426. doi: 10.1016/0166-2236(94)90016-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]