Abstract

The myelin-associated glycoprotein (MAG) is a member of the immunoglobulin gene superfamily and is thought to play a critical role in the interaction of myelinating glial cells with the axon. Myelin from mutant mice incapable of expressing MAG displays various subtle abnormalities in the CNS and degenerates with age in the peripheral nervous system (PNS). Two distinct isoforms, large MAG (L-MAG) and small MAG (S-MAG), are produced through the alternative splicing of the primary MAG transcript. The cytoplasmic domain of L-MAG contains a unique phosphorylation site and has been shown to associate with the fyn tyrosine kinase. Moreover, L-MAG is expressed abundantly early in the myelination process, possibly indicating an important role in the initial stages of myelination. We have adapted the gene-targeting approach in embryonic stem cells to generate mutant mice that express a truncated form of the L-MAG isoform, eliminating the unique portion of its cytoplasmic domain, but that continue to express S-MAG. Similar to the total MAG knockouts, these animals do not express an overt clinical phenotype. CNS myelin of the L-MAG mutant mice displays most of the pathological abnormalities reported for the total MAG knockouts. In contrast to the null MAG mutants, however, PNS axons and myelin of older L-MAG mutant animals do not degenerate, indicating that S-MAG is sufficient to maintain PNS integrity. These observations demonstrate a differential role of the L-MAG isoform in CNS and PNS myelin.

Keywords: alternative RNA splicing, gene knockout, mouse models, myelin-associated glycoprotein, oligodendrocytes, Schwann cells

Although it is a minor component of myelin, considerable evidence has implicated the myelin-associated glycoprotein (MAG) as an important regulator of the interaction between myelinating cells and axons (for review, see Quarles, 1983; Salzer et al., 1990; Trapp, 1990). MAG is expressed early in the myelination process when myelinating cells initiate contact with axons, and MAG binds to axons when it is incorporated into liposomes (Johnson et al., 1989). Furthermore, MAG is a member of the immunoglobulin gene superfamily and shares significant homology with the neural cell adhesion molecule (N-CAM) (Salzer et al., 1987). The periaxonal location of MAG in mature myelin suggests a role for MAG in maintaining the interaction between the myelinating cell and axon (Sternberger et al., 1979).

Recently, mice have been generated with a null mutation in the MAG gene (Li et al., 1994; Montag et al., 1994). CNS myelin formation is delayed in the mutant animals (Montag et al., 1994; Bartsch et al., 1997). Moreover, oligodendrocytic cytoplasmic collars of mature CNS myelin are frequently missing or reduced, whereas controversy persists with regard to the effect of MAG deficiencies on periaxonal spacing (for review, see Bartsch, 1996). Compact myelin of the MAG mutants also contains an increased presence of cytoplasmic loops of oligodendrocytes. Redundant myelination is also common in the CNS of adult MAG mutants (Bartsch et al., 1995), and 8-month-old mice display evidence of dying-back oligodendrogliopathy (Lassmann et al., 1997). In contrast, peripheral nervous system (PNS) myelin formation proceeds normally in MAG-deficient animals. Older mutants, however, display PNS axonal and myelin degeneration with the presence of superfluous Schwann cell processes, indicating that MAG plays a critical role in maintaining PNS integrity (Fruttiger et al., 1995).

Two isoforms of the MAG protein, which are the result of alternative splicing of the primary MAG transcript, are found in myelin (Frail and Braun, 1984; Lai et al., 1987; Tropak et al., 1988). The small (S-MAG) and large (L-MAG) isoforms are identical in their extracellular and transmembrane domains but are distinct at their C-terminal ends (Lai et al., 1987). Early in the myelination process expression of L-MAG predominates, whereas S-MAG accumulates in later stages (Lai et al., 1987; Tropak et al., 1988; Inuzuka et al., 1991; Pedraza et al., 1991). Interestingly, the cytoplasmic region unique to L-MAG contains a tyrosine phosphorylation site, suggesting a role in the regulation of MAG function (Edwards et al., 1988; Afar et al., 1990; Jaramillo et al., 1994).

To examine the role played by the individual MAG isoforms in the myelination process, we have adapted the gene-targeting approach to prematurely truncate the cytoplasmic domain of the L-MAG isoform in mice. The resulting mutant animals continue to express S-MAG, as well as the truncated form of L-MAG. Interestingly, CNS myelin of these animals displays most of the pathological abnormalities of the null MAG mutants, whereas PNS myelin of the truncated L-MAG mutants appears normal. These results indicate that L-MAG is an important component of CNS, but not PNS, myelin.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Cloning of mouse MAG gene and construction of the L-MAGtrun targeting construct. The mouse MAG gene was isolated from a 129/SV mouse genomic library (Stratagene, La Jolla, CA) using probes derived from the DBA mouse strain (Nakano et al., 1991). We isolated a λ clone, λM67–1, that contained 13 kb of the 3′ region of the MAG gene, including exon 13. To generate the L-MAGtrun targeting construct, a deletion was first introduced into the 13th MAG exon using overlapping extension PCR. Two PCR primer pairs were generated to the MAG gene that after ligation of the PCR products resulted in the deletion of 123 bp. The upstream primer pair (T27: CTCATG TCC TGT ACA GCC C; T15: TGA CTC GGA TTT CTG CTC GAG ATC ACA GGC GCT GCT TCT CA) and downstream primer pair (T8: TGA CTC GGA TTT CTG CTC GAG ATC CCA GGC GCT GCT TCT; T13: CTG GTT CCA TTC CCA GCT C) introducedXhoI restriction enzyme sites (underlined) 5′ and 3′, respectively, to the introduced deletion to allow for the insertion of the 1133 bp neo gene, isolated from pMC1neo poly A (Stratagene). The T15 primer also introduced a stop codon (bold) upstream to theXhoI site. The resulting plasmid was analyzed by DNA sequencing to confirm the introduced changes in the MAG sequence. An additional 5.6 kb HindIII fragment (see Fig.1A) was added to the upstream region in the targeting vector, resulting in a total of 5.9 kb of 5′ homology and 0.7 kb of 3′ homology, which extends to the SalI site shown in Figure1A. The 1.8 kb Herpes simplex virus thymidine kinase (HSV-tk) gene was inserted 5′ to the upstream homology, resulting in the 12.5 kb targeting plasmid pLHT7.

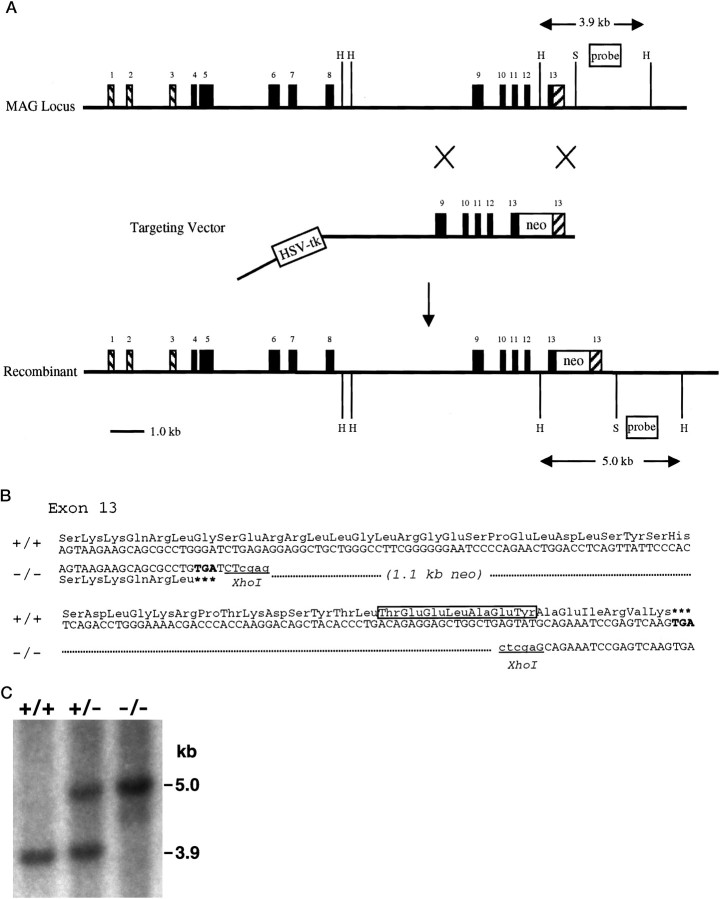

Fig. 1.

Targeted disruption of the mouse MAG locus.A, A partial restriction map of the MAG gene, targeting construct, and the expected replacement event are shown. The neomycin resistance gene (neo) was inserted into the 13th exon, which codes for the C terminal 55 amino acids of L-MAG. The first three exons (descending hatches) encode the 5′ untranslated region of the MAG mRNA, and the 3′ portion of the 13th exon (ascending hatches) encodes the 3′ untranslated region of the normal L-MAG mRNA. The relative location of the screening probe is shown. The top double-headed arrow indicates the endogenous 3.9 Kb HindIII fragment that is characteristic of the wild-type gene. The addition of the neo gene yields a diagnostic 5.0 Kb HindIII fragment. Restriction endonuclease sites: H, HindIII;S, SalI. B, Nucleotide and amino acid sequence of wild-type and targeted 13th MAG exon. PCR was used to introduce the designated stop codon into the targeting construct, upstream of the neo resistance gene. The truncation eliminates the final 49 amino acids of the cytoplasmic domain of L-MAG. The boxed amino acid sequence denotes the tyrosine phosphorylation site. The XhoI sites that are indicated were generated by PCR and represent the endpoints of the introduced deletion. C, Southern blot analysis of tail DNA from wild-type (+/+), heterozygous (+/−), and homozygous (−/−) mutant mice is shown. Tail DNA was digested with HindIII and hybridized with the probe depicted in A.

After linearization with SalI, pLHT7 was electroporated into the BK4 subclone of the E14TG2a embryonic stem (ES) cell line. Clones that survived G418 and gancyclovir selection were identified by Southern blot analysis using a probe located outside the targeting vector (see Fig. 1A). Five of the clones were injected into C57BL/6J blastocysts, resulting in the production of 13 chimeras, as determined by coat color. Male chimeric mice were bred with C57BL/6 females, and agouti offspring were screened for transmission of the disrupted allele by Southern blot hybridization. Interbreeding of heterozygote F1 mice generated homozygotes. For Southern blot analysis, 5–10 μg of ES or tail DNA was digested withHindIII, separated by agarose gel electrophoresis, and transferred to Zeta-Probe (Bio-Rad, Hercules, CA) using 0.4N NaOH. Probes were labeled by random priming. Hybridization and washes were performed as described previously (Coetzee et al., 1996).

Western blots. Myelin proteins were isolated from total brain homogenate using the discontinuous sucrose gradient approach described by Norton and Poduslo (1973) and assayed using the Lowry method. Samples containing 20 μg of myelin protein were electrophoresed on a 10% SDS-polyacrylamide gel, transferred to a nitrocellulose membrane, and stained with Ponceau S solution (Sigma, St. Louis, MO) to assure that equivalent amounts of protein were loaded in each lane. The filters were probed with antisera specific to unique portions of mouse S-MAG and L-MAG, as well as to common MAG domains (Fujita et al., 1990). A monoclonal antibody to myelin basic protein (MBP) (Sternberger Monoclonals, Baltimore, MD) was also used. All antibodies were used at a dilution of 1:5000. Positive antibody–antigen reactions were visualized using chemiluminescence reagents from Boehringer Mannheim (Indianapolis, IN).

Northern blots and RT-PCR. Total RNA was prepared from mouse brains using either the guanidinium thiocyanate method of Chirgwin et al. (1979) or the TRIzol reagent (Life Technologies, Gaithersburg, MD) following the manufacturers recommendations. Northern blots were prepared as described by Popko et al. (1987). Probes for MAG (Sutcliffe et al., 1983) and proteolipid protein (PLP) (Milner et al., 1985) were prepared by PCR (Jansen and Ledley, 1989) or random priming as described by Popko et al. (1987). Hybridization and washes were performed as described previously (Popko et al., 1987). A pair of oligonucleotides for 18S ribosomal RNA were end-labeled with32P and used to evaluate relative levels of total RNA present in each lane as described (Stahl et al., 1990).

For the PCR amplification of MAG cDNA (RT-PCR), the Superscript Preamplification System (Life Technologies) was used to generate random-primed cDNA from 2.0 μg of total mouse brain RNA. RT-PCR was performed essentially as described (Hayes et al., 1992) with primers to MAG exon 10 (ATT GTG TGC TAC ATC ACC CAG ACG) and exon 13 (GAT CCC AGG CGC TGC TTC TCA CT) (Fujita et al., 1989). Amplification of cDNA derived from S-MAG mRNA, which contains exon 12, produces a product of 199 bp, and amplification of cDNA derived from L-MAG mRNA, which lacks this exon, produces a product of 154 bp. PCR products were run on a 2.5% agarose gel containing 1.5% Nusieve agarose (FMC Bioproducts, Rockland, ME) and visualized by ethidium bromide staining. An internal oligonucleotide probe was used as a hybridization probe to confirm the identity of the MAG RT-PCR products.

Morphological analysis. Mice were perfused through the left cardiac ventricle with an ice-cold solution of 4% paraformaldehyde and 2.5% glutaraldehyde in 0.1 m sodium phosphate buffer, pH 7.4. Tissue samples from the optic nerve, 1.75 mm anterior to the optic chiasma, and from the sciatic nerve, 5 mm distal to the sciatic notch, were immersion-fixed in the same solution overnight at 4°C. Tissues were processed, embedded, sectioned, and analyzed by electron microscopy as described previously (Fujita et al., 1996).

RESULTS

Gene-targeting construct and mutant animals

To explore the function of the cytoplasmic domain of L-MAG, including the tyrosine phosphorylation site, we generated mutant animals that express a form of L-MAG truncated at the C terminal. S-MAG contains a 48 residue cytoplasmic domain, and L-MAG contains a 93 residue cytoplasmic domain, the first 38 amino acids of which are also present in S-MAG (Fujita et al., 1989). The 12th MAG exon, which is alternatively spliced, encodes the final 10 amino acids of S-MAG, and the 13th exon encodes the final 55 amino acids of L-MAG (Fig.1A). A stop codon was introduced into the 13th MAG exon, such that the final 49 amino acids of L-MAG should not be translated without altering the expression of S-MAG (Fig. 1B). The truncated allele of L-MAG is predicted to encode a protein four amino acids shorter than wild-type S-MAG. The neomycin resistance gene was placed downstream of the introduced mutation to provide a positive selectable marker after transfection of the targeting construct into ES cells. The tk gene of HSV was also included in the targeting construct to provide negative selection against random integration events. The resulting construct was electroporated into ES cells, and 254 ES cell clones survived positive and negative selection, eight of which were shown to have the correct targeting event. A line of mice heterozygous for the L-MAGtrun mutation was established after the injection of properly targeted ES cells into C57BL blastocysts (Fig.1C). When heterozygous animals were interbred, progeny homozygous for the L-MAGtrun mutation were produced at the expected frequency (25%), indicating that the mutation was not deleterious to mouse development. Furthermore, homozygous mutant mice did not display any remarkable phenotypic abnormalities.

MAG expression in the mutants

As the first step toward determining whether the targeted MAG locus was being expressed as predicted, Western blot analysis was performed. As can be seen in Figure 2, when antibodies that are specific to the cytoplasmic domain of L-MAG are used to probe a blot of total CNS myelin proteins, proteins containing the L-MAG-specific epitope cannot be detected in samples from the mutant animals. In contrast, when antibodies specific to S-MAG are used to probe the same blot, a distinct band of the appropriate molecular weight is detected in the samples from the mutant animals, albeit at levels reduced (∼50%) from that seen in samples from wild-type mice. When antibodies that are specific to the common extracellular domain of MAG are used, bands are seen in samples of both wild-type and mutant animals. Interestingly, the percentage of control amounts of MAG protein detected in the samples from the mutant animals by the common antibody is increased relative to that seen when S-MAG alone is examined. This indicates that the truncated L-MAG protein is being produced in the mutant mice, but that, as expected, it is not detected by the L-MAG antibody. The Western blot data in Figure 2 also demonstrates that the amount of MBP present in the myelin of the mutant animals is not altered.

Fig. 2.

Western blot analysis of myelin proteins from wild-type and L-MAGtrun mutant mice. Samples containing 20 μg of myelin protein from 14-, 24-, 80-, and 154-d-old wild-type (+/+) and L-MAGtrun mutant (−/−) mice were electrophoresed on a 10% SDS-polyacrylamide gel and transferred to a nitrocellulose membrane. The filter was probed with antisera specific to unique portions of S-MAG and L-MAG (Fujita et al., 1990), as well as to common (T-MAG) MAG domains (Fujita et al., 1988). A monoclonal antibody to MBP (Sternberger Monoclonals) was also used. Positive antibody antigen reactions were visualized using chemiluminescence reagents from Boehringer Mannheim.

To examine the reason for the reduced levels of S-MAG and total MAG in the mutant animals, Northern blot analysis was performed. As can be seen in Figure 3, reduced levels of the MAG transcript appear to be in brain RNA samples isolated from the mutant mice. The mRNA transcript derived from targeted MAG gene contains the neo resistance gene in the 3′ untranslated region and as such is ∼1.1 kb longer than the transcript derived from the wild-type locus. Moreover, the MAG transcript appears as a doublet in the RNA samples from the mutant animals. The neo gene has been inserted into the 13th MAG exon in the same transcriptional orientation as the MAG gene. The polyadenylation site of the neo gene is likely being used on occasion to prematurely truncate the MAG transcript, thereby resulting in two transcripts differing in their 3′ untranslated region. Further analysis is needed to determine whether the inclusion of the neo sequences within the MAG transcript is also responsible for reducing the stability of the MAG mRNA. As expected, PLP mRNA levels are not affected by the L-MAGtrun mutation.

Fig. 3.

Northern blot analysis of total RNA isolated from brains of wild-type and L-MAGtrun mice. Total brain RNA isolated from 30- and 240-d-old wild-type and L-MAGtrun mutant mice was separated by formaldehyde–agarose gel electrophoresis, transferred to nylon membranes, and probed for the expression of MAG and PLP. The membrane was analyzed for 18S RNA to insure equivalent loading between lanes (data not shown).

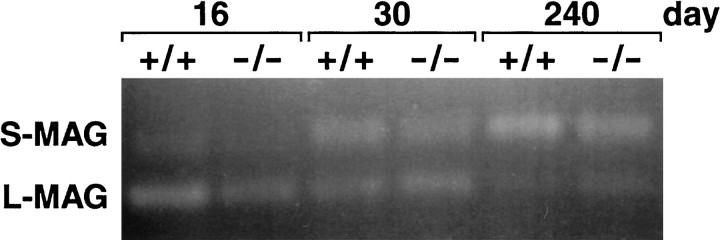

An RT-PCR assay was used to determine whether the primary transcript derived from the mutant MAG locus was subject to similar alternative splicing of the 12th exon as the wild-type locus. PCR primers, complementary to MAG exons 10 and 13, were used to amplify cDNA generated to brain RNA samples isolated from wild-type and mutant animals of various ages. As shown in Figure4, transcripts devoid of exon 12 (L-MAG mRNA) are most prevalent in younger wild-type and mutant animals, whereas transcripts containing the 12th exon (S-MAG mRNA) are predominant in older wild-type and mutant mice.

Fig. 4.

RT-PCR analysis of MAG mRNA in wild-type and L-MAGtrun mice. PCR was performed on cDNA derived from total brain RNA isolated from 16-, 30-, and 240-d-old wild-type and L-MAGtrun mice. The primers were derived from the 10th and 13th MAG exons, such that amplification of cDNA corresponding to S-MAG mRNA resulted in a 199 bp product, and amplification of cDNA derived from L-MAG mRNA resulted in a 154 bp product. PCR products were electrophoresed through a 2.5% agarose gel containing 1.5% Nusieve agarose and visualized by ethidium bromide staining.

Abnormal CNS myelin in the L-MAGtrun mutants

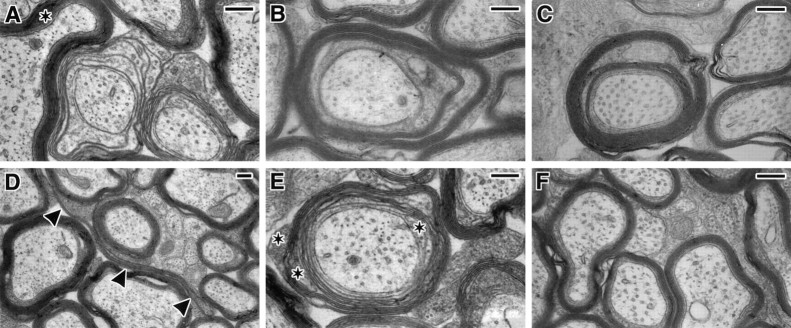

The ultrastructural analysis of the optic nerves from L-MAG-deficient mice revealed abnormal myelin formation in ∼13% of the myelin sheaths (Table 1). Less than 5% of the sheaths in the littermate control mice displayed similar signs of abnormal myelination. Although several types of atypical myelin sheaths were observed, the most common myelin defect present in the L-MAG mutant mice was the retention of cytoplasm within the myelin lamella. In 1-month-old mice (Fig.5A), the presence of cytoplasm in the myelin sheath suggests a delay in the compaction process. The retention of cytoplasm in regions of compact myelin in 8-, 12-, and 16-month-old animals indicates an inability to form mature myelin (Fig.5B,C). In addition, profiles of redundant myelin, often cradling other myelinated processes, were observed in the mutant animals at 1, 8, 12, and 16 months of age (Fig. 5D). Less frequently, myelin sheaths were observed to contain multiple inner and outer cytoplasmic loops that are indicative of multiple processes ensheathing a single internodal segment (Fig. 5E).

Table 1.

Morphological analysis of optic nerve myelin sheaths

| Genotype | Age (months) | Processes | Pathology (%) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Wild type | |||

| Animal 1 | 1 | 257 | 5.5 |

| Animal 2 | 8 | 153 | 5.9 |

| Animal 3 | 8 | 343 | 2.0 |

| Animal 4 | 8 | 322 | 1.6 |

| Animal 5 | 12 | 231 | 8.2 |

| Animal 6 | 12 | 219 | 5.0 |

| Total | 1525 | 4.7* ± 0.26 | |

| L-MAGtrun | |||

| Animal 1 | 1 | 228 | 19.3 |

| Animal 2 | 8 | 166 | 15.7 |

| Animal 3 | 8 | 117 | 13.7 |

| Animal 4 | 8 | 120 | 15.8 |

| Animal 5 | 12 | 391 | 9.7 |

| Animal 6 | 16 | 280 | 12.9 |

| Animal 7 | 16 | 329 | 9.4 |

| Animal 8 | 16 | 382 | 6.0 |

| Animal 9 | 16 | 339 | 14.8 |

| Total | 2352 | 13.0* ± 0.22 |

Randomly selected sheaths of the optic nerves 1.75 mm anterior to the optic chiasma were analyzed for the presence of multiple wraps, lack of compaction, and redundant myelin. Multiple wraps were indicated by the presence of more than one pair of cytoplasmic tongues associated with an individual axon. Lack of compaction was indicated by the presence of cytoplasm within the myelin lamella, and redundant myelin was indicated by the presence of a compact myelin tail extending away from the axon. Electron micrographs at 35,000× were examined.

*Data are presented as mean ± SE and were analyzed using the Student t test. They are significantly different at ap value <0.001.

Fig. 5.

Myelinated axons from the optic nerves of L-MAGtrun mutant mice demonstrating sheath defects.A, Myelin sheaths that contain cytoplasmic organelles between lamellae indicative of a delay or block in compact myelin formation are shown. Note the retention of oligodendrocyte cytoplasm in regions of compact myelin (*). B, C, Myelinated fibers from 8- and 16-month-old animals with cytoplasm between the lamellae of compact myelin are shown. D demonstrates a profile of redundant compact myelin (indicated by arrowheads) coursing away from the axon. E, A neuronal fiber myelinated by at least two oligodendrocytic processes as indicated by multiple cytoplasmic tongues (*). F, Optic nerve processes from a littermate wild-type mouse demonstrating normal myelin formation. Scale bar, 0.25 μm.

Normal CNS myelin in mice heterozygous for the null MAG allele

The ∼50% reduction in the levels of total MAG protein in the L-MAGtrun mutants may contribute to the CNS myelin abnormalities present in these animals. To examine the effect of such a general reduction in MAG protein levels on the myelination process we have examined the CNS of mice that are heterozygous for the null MAG allele and thus express only a single functioning allele of the MAG gene. The abundance of axons with multiple myelin wraps, lack of myelin compaction, and redundant myelin were examined in mice heterozygous and homozygous for the null MAG allele, as well as in control animals. When compared with wild-type mice, no significant increase in myelin abnormalities was observed in the heterozygous animals (data not shown), whereas aberrant myelin sheaths were present in 14.9% (± 4.4%) of the axons of the mice homozygous for the null allele.

Normal peripheral nerve ultrastructure in the L-MAGtrun mutants

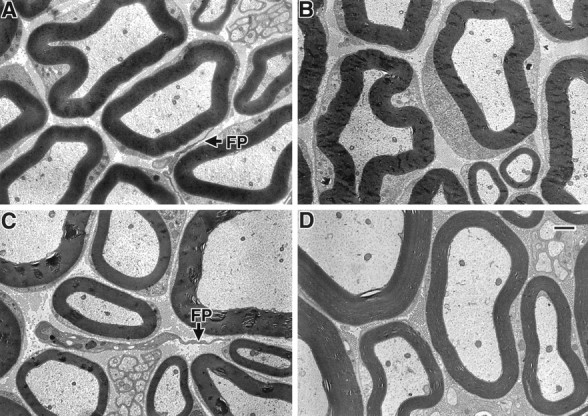

In contrast to the abnormal myelin observed in the CNS, the myelin in the PNS appeared morphologically normal. As shown in Figure6, sciatic nerves from the 1-, 8-, and 16-month-old L-MAG-deficient mice contained compact myelin, and the frequency of abnormally myelinated axons was similar between the mutant and littermate wild-type animals (Table2). Moreover, neither changes in periaxonal structures nor increased axonal degeneration was detected in the mutant animals at the time points examined (1, 8, 12, and 16 months).

Fig. 6.

Myelinated axons from the sciatic nerves of L-MAGtrun mutant and wild-type mice. Sciatic nerve processes from 1-month-old littermate wild-type (A), 1-month-old L-MAGtrunmutant (B), 8-month-old L-MAGtrun (C), and 16-month-old L-MAGtrun (D) mice demonstrating normal myelin ultrastructure are shown. Note the presence of fibroblast processes (FP), identified by the absence of a basement membrane, in A andC. Scale bar, 1.0 μm.

Table 2.

Morphological analysis of sciatic nerve myelin sheaths

| Genotype | Age (months) | Processes | Pathology (%) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Wild type | |||

| Animal 1 | 1 | 280 | 2.1 |

| Animal 2 | 8 | 214 | 3.3 |

| Animal 3 | 8 | 299 | 2.3 |

| Animal 4 | 8 | 348 | 2.9 |

| Animal 5 | 12 | 230 | 4.8 |

| Animal 6 | 12 | 198 | 3.0 |

| Total | 1569 | 3.1 ± 0.17 | |

| L-MAGtrun | |||

| Animal 1 | 1 | 308 | 1.3 |

| Animal 2 | 1 | 305 | 2.6 |

| Animal 3 | 8 | 265 | 6.0 |

| Animal 4 | 8 | 184 | 4.4 |

| Animal 5 | 12 | 282 | 2.8 |

| Animal 6 | 16 | 289 | 3.5 |

| Animal 7 | 16 | 202 | 2.5 |

| Animal 8 | 16 | 321 | 3.7 |

| Animal 9 | 16 | 285 | 5.3 |

| Total | 2541 | 3.6 ± 0.14 |

Randomly selected sheaths of sciatic nerves 5 mm distal to the sciatic notch were analyzed for the presence of multiple wraps, lack of compaction, and redundant myelin as described in Table 1. Electron micrographs at 5000× were examined. Data are presented as mean ± SE and were analyzed using the Student t test. No significant difference was found.

DISCUSSION

To examine the function of the individual MAG isoforms in the myelination process, we have used the gene-targeting approach to introduce a stop codon into the last MAG exon, thereby prematurely terminating translation of L-MAG mRNA. In that this exon serves solely as 3′ untranslated region in the S-MAG mRNA (Lai et al., 1987; Nakano et al., 1991), the introduced mutation should not affect the translation of the S-MAG transcript. As predicted, the animals generated with the targeting construct do not produce L-MAG containing the unique cytoplasmic domain. Nevertheless, Western blot analysis performed with antibodies to the unique cytoplasmic domain of S-MAG in combination with antiserum to the common region of MAG indicates that the truncated form of L-MAG is present in the mutant animals.

Total levels of MAG mRNA and protein, however, are unexpectedly reduced by ∼50% in the mutant animals. Perhaps the inclusion of the neo gene in the MAG transcriptional unit results in the destabilization of the MAG transcripts. Alternatively, the presence of the thymidine kinase promoter within the targeted MAG allele may lead to reduced transcription initiation off the MAG promoter or to the production of antisense MAG transcripts (Johnson and Friedmann, 1990), thereby resulting in the reduction of steady-state levels of MAG mRNA.

A significantly increased percentage of optic nerve axons from adult L-MAGtrun mutant animals display features typically associated with early stages of myelination. Most frequently these abnormalities include the presence of cytoplasm within the myelin lamella, which was noted in young (1 month) and older (8, 12, and 16 months) animals. This observation indicates that the cytoplasmic domain of L-MAG is playing a role in myelin compaction. Redundant compact myelin, a common feature usually restricted to the developing nervous system, also was observed frequently in the CNS of adult mutant animals, further suggesting a delay or block in myelin maturation. Another abnormality observed more frequently in the mutant animals than in controls was the presence of multiple oligodendroglial processes ensheathing a single axonal segment. These results indicate that the absence of the cytoplasmic domain of L-MAG is adversely affecting interactions among oligodendrocytes as well as between oligodendrocytes and axons. The periaxonal space, however, appeared normal in the L-MAGtrun mice. Li et al. (1994) observed swollen and disorganized periaxonal spaces in the CNS of the null MAG mutants, whereas Montag et al. (1994) did not report such abnormalities.

The similarities of the atypical myelin features displayed in the CNS of the L-MAGtrun mutant animals with those that occur in the complete MAG null mutant mice (Li et al., 1994; Montag et al., 1994; Bartsch et al., 1995; Lassmann et al., 1997) indicate that L-MAG plays the predominant role of the two MAG isoforms in CNS myelination. Moreover, the data presented here strongly support the hypothesis that the unique cytoplasmic domain of L-MAG plays a critical function in the regulation of the myelination process. The tyrosine phosphorylation site in the C terminal of L-MAG, which is deleted in the L-MAGtrun mutant mice, is likely to be critical in the transduction of important signals for the myelinating function of oligodendrocytes (Edwards et al., 1988; Afar et al., 1990; Jaramillo et al., 1994). Interestingly, co-immunoprecipitation data have demonstrated that the fyn tyrosine kinase, which itself is maximally phosphorylated in CNS myelin during the initial period of myelination, associates with L-MAG (Umemori et al., 1994). Moreover, mice in which the fyn gene has been inactivated produce ∼50% of normal amounts of myelin (Umemori et al., 1994).

The ∼50% reduction in overall levels of MAG in the L-MAG mutants might contribute to some or all of the abnormalities observed in the CNS of these animals. Therefore, we have performed a detailed examination of the morphology of CNS myelin of mice that are heterozygous for the null MAG mutation and consequently express only a single functioning allele of the MAG gene. There was no increase in the presence of multiple myelin wraps, lack of myelin compaction, or redundant myelin in mice with a single wild-type MAG gene relative to controls. Interestingly, in mice homozygous for the null MAG allele, these abnormalities were present in ∼15% of CNS axons, which is similar to the incidence observed in the L-MAG mutants (Table 1). These data strongly support our assertion that the defects that we have observed in the L-MAG mutants are predominantly attributable to the truncation of the cytoplasmic domain of the L-MAG isoform. Another possibility is that the truncated isoform of L-MAG might be acting in a dominant manner to disrupt the myelination process in the CNS. This seems unlikely, however, in that the truncated form of L-MAG differs from S-MAG at only six amino acids at the C terminus.

In the MAG null mutants PNS myelination appears to proceed normally. Nevertheless, PNS axon and myelin degeneration are observed in older mutants, indicating that MAG plays a critical role in maintaining PNS integrity (Fruttiger et al., 1995). It is quite interesting that the PNS of the L-MAGtrun mutants fails to develop any of the neuropathological abnormalities that the older total MAG knockouts display prominently. This difference was unexpected because L-MAG expression occurs at moderate levels during the myelination of the PNS (Tropak et al., 1988; Inuzuka et al., 1991; Pedraza et al., 1991). The data presented here indicate that L-MAG is not essential for normal PNS myelination and that S-MAG plays the predominant role in maintaining the interactions between myelinating Schwann cells and axons. Interestingly, these data are consistent with recent observations that indicate that in the PNS MAG functions more as a ligand for an axonal receptor than as a signaling or structural molecule for Schwann cells (B. Trapp, personal communication). Thus, the extracellular domain of MAG (S or L) may be sufficient for maintaining proper PNS integrity.

Interestingly, N-CAM has been demonstrated to be expressed in normal Schwann cells and myelin (Martini and Schachner, 1986) and overexpressed in the PNS of the total MAG mutants (Montag et al., 1994). More recently Carenini et al. (1997) have shown that the onset of PNS myelin and axon degeneration is accelerated in MAG/N-CAM double mutants, suggesting that N-CAM might partially compensate for the absence of MAG in maintaining PNS integrity. It is perhaps relevant to point out that the N-CAM signaling pathway requires the fyn tyrosine kinase (Beggs et al., 1994). It will be informative to determine whether L-MAGtrun/N-CAM double mutants display PNS abnormalities.

It is also noteworthy that the L-MAGtrun mutant mice described here display many of the same myelin abnormalities seen inquaking mutant mice. Quaking is a recessive mutation that results in a severe myelin deficit in homozygotes (Sidman et al., 1964). Mutant animals develop a rapid tremor by approximately postnatal day 12 and tonic seizures in adults. CNS myelin ofquaking mice demonstrates an apparent arrest in maturation with a lack of compaction and pockets of oligodendroglial cytoplasm (Wisniewski and Morell, 1971), whereas PNS myelin is only mildly affected (Samorajski et al., 1970; Suzuki and Zagoren, 1977). Biochemically, there is a dramatic reduction in the amount of L-MAG present, with perhaps an overexpression of S-MAG, in the mutant animals (Fujita et al., 1988, 1990). Although the quaking locus has been mapped to chromosome 17 and the MAG gene is located on mouse chromosome 7 (Barton et al., 1987; D’Eustachio et al., 1988), it has been hypothesized that the L-MAG deficiency might contribute to the abnormalities in quaking myelin (Fujita et al., 1988, 1990;Bartoszewicz et al., 1995; Bo et al., 1995). Recently, thequaking locus has been shown to encode a protein that likely links signal transduction with RNA processing (Ebersole et al., 1996). As such, one consequence of the quaking mutation might be the abnormal splicing of the MAG transcriptional unit, resulting in little L-MAG mRNA and protein production (Ebersole et al., 1996). Nevertheless, the relative mildness of the myelin malformations observed in the L- MAGtrun and total MAG mutant mice demonstrates that additional defects must also be present inquaking oligodendrocytes.

In summary, we have used the gene-targeting approach in embryonic stem cells to introduce a subtle mutation into the mouse MAG gene. The mutant animals that were generated express a truncated form of L-MAG that lacks the final 49 amino acids, including the tyrosine phosphorylation site. These animals, which continue to express S-MAG, display similar myelin abnormalities in the CNS as do mice completely deficient in MAG expression, strongly suggesting that L-MAG is the critical MAG isoform in the CNS. Nevertheless, the PNS of the mutant animals does not display neuropathological abnormalities, in contrast to the total MAG mutants, indicating that S-MAG expression is sufficient to maintain PNS integrity.

Footnotes

This work was supported by Grants NS27336 (B.P.), NS24453 (K.S.), and NS24289 (K.S.), and a Mental Retardation Research Center core grant (HD03110) from National Institutes of Health (NIH). B.P. is the recipient of a Research Career Development Award from NIH (NS01637). J.D. is supported by Training Grant HD07201 from NIH. N.F. was supported by a grant from the International Human Frontiers Science Organization. We thank Dr. Bruce Trapp for communicating data before publication, Dr. Dirk Montag for providing the null MAG mutant animals, and Christiane Born for technical assistance.

Correspondence should be addressed to Dr. Brian Popko, Neuroscience Center, CB 7250, University of North Carolina, Chapel Hill, NC 27599-7250.

REFERENCES

- 1.Afar DE, Salzer JL, Roder J, Braun PE, Bell JC. Differential phosphorylation of myelin-associated glycoprotein isoforms in cell culture. J Neurochem. 1990;55:1418–1426. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-4159.1990.tb03155.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Barton DE, Arquint M, Roder J, Dunn R, Francke U. The myelin-associated glycoprotein gene: mapping to human chromosome 19 and mouse chromosome 7 and expression in quivering mice. Genomics. 1987;1:107–112. doi: 10.1016/0888-7543(87)90002-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Bartoszewicz ZP, Noronha AB, Fujita N, Sato S, Bö L, Trapp BD, Quarles RH. Abnormal expression and glycosylation of the large and small isoforms of myelin-associated glycoprotein in dysmyelinating quaking mutants. J Neurosci Res. 1995;41:27–38. doi: 10.1002/jnr.490410105. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Bartsch U. Myelination and axonal regeneration in the central nervous system of mice deficient in the myelin-associated glycoprotein. J Neurocytol. 1996;25:303–313. doi: 10.1007/BF02284804. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Bartsch U, Montag D, Bartsch S, Schachner M. Multiply myelinated axons in the optic nerve of mice deficient for the myelin-associated glycoprotein. Glia. 1995;14:115–122. doi: 10.1002/glia.440140206. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Bartsch S, Montag D, Schachner M, Bartsch U. Increased number of unmyelinated axons in optic nerves of adult mice deficient in the myelin-associated glycoprotein (MAG). Brain Res. 1997;762:231–234. doi: 10.1016/s0006-8993(97)00484-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Beggs HE, Soriano P, Maness PF. NCAM-dependent neurite outgrowth is inhibited in neurons from Fyn-minus mice. J Cell Biol. 1994;127:825–833. doi: 10.1083/jcb.127.3.825. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Bö L, Quarles RH, Fujita N, Bartoszewicz Z, Sato S, Trapp BD. Endocytic depletion of L-MAG from CNS myelin in quaking mice. J Cell Biol. 1995;131:1811–1820. doi: 10.1083/jcb.131.6.1811. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Carenini S, Montag D, Cremer H, Schachner M, Martini R. Absence of the myelin-associated glycoprotein (MAG) and the neural cell adhesion molecule (N-CAM) interferes with the maintenance, but not with the formation of peripheral myelin. Cell Tissue Res. 1997;287:3–9. doi: 10.1007/s004410050727. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Chirgwin JM, Przybyla AE, MacDonald RJ, Rutter WJ. Isolation of biologically active ribonucleic acid from sources enriched in ribonuclease. Biochemistry. 1979;18:5294–5299. doi: 10.1021/bi00591a005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Coetzee T, Fujita N, Dupree J, Shi R, Blight A, Suzuki K, Suzuki K, Popko B. Myelination in the absence of galactocerebroside and sulfatide: normal structure with abnormal function and regional instability. Cell. 1996;86:209–219. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)80093-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.D’Eustachio P, Colman DR, Salzer JL. Chromosomal location of the mouse gene that encodes the myelin-associated glycoproteins. J Neurochem. 1988;50:589–593. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-4159.1988.tb02951.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Ebersole TA, Chen Q, Justice MJ, Artzt K. The quaking gene product necessary in embryogenesis and myelination combines features of RNA binding and signal transduction proteins. Nat Genet. 1996;12:260–265. doi: 10.1038/ng0396-260. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Edwards AM, Arquint M, Braun PE, Roder JC, Dunn RJ, Pawson T, Bell JC. Myelin-associated glycoprotein, a cell adhesion molecule of oligodendrocytes, is phosphorylated in brain. Mol Cell Biol. 1988;8:2655–2658. doi: 10.1128/mcb.8.6.2655. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Frail DE, Braun PE. Two developmentally regulated messenger RNAs differing in their coding region may exist for the myelin-associated glycoprotein. J Biol Chem. 1984;259:14857–14862. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Fruttiger M, Montag D, Schachner M, Martini R. Crucial role for the myelin-associated glycoprotein in the maintenance of axon-myelin integrity. Eur J Neurosci. 1995;7:511–515. doi: 10.1111/j.1460-9568.1995.tb00347.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Fujita N, Sato S, Kurihara T, Inuzuka T, Takahashi Y, Miyatake T. Developmentally regulated alternative splicing of brain myelin-associated glycoprotein mRNA is lacking in the quaking mouse. FEBS Lett. 1988;232:323–327. doi: 10.1016/0014-5793(88)80762-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Fujita N, Sato S, Kurihara T, Kuwano R, Sakimura K, Inuzuka T, Takahashi Y, Miyatake T. cDNA cloning of mouse myelin-associated glycoprotein: a novel alternative splicing pattern. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 1989;165:1162–1169. doi: 10.1016/0006-291x(89)92724-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Fujita N, Sato S, Ishiguro H, Inuzuka T, Baba H, Kurihara T, Takahashi Y, Miyatake T. The large isoform of myelin-associated glycoprotein is scarcely expressed in the quaking mouse brain. J Neurochem. 1990;55:1056–1059. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-4159.1990.tb04596.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Fujita N, Suzuki K, Vanier MT, Popko B, Maeda N, Klein A, Henseler M, Sandhoff K, Nakayasu H, Suzuki K. Targeted disruption of the mouse sphingolipid activator protein gene: a complex phenotype, including severe leukodystrophy and wide-spread storage of multiple sphingolipids. Hum Mol Genet. 1996;5:711–725. doi: 10.1093/hmg/5.6.711. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Hayes C, Kelly D, Murayama S, Komiyama A, Suzuki K, Popko B. Expression of the neu oncogene under the transcriptional control of the myelin basic protein gene in transgenic mice: generation of transformed glial cells. J Neurosci Res. 1992;31:175–187. doi: 10.1002/jnr.490310123. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Inuzuka T, Fujita N, Sato S, Baba H, Nakano R, Ishiguro H, Miyatake T. Expression of the large myelin-associated glycoprotein isoform during the development in the mouse peripheral nervous system. Brain Res. 1991;562:173–175. doi: 10.1016/0006-8993(91)91204-e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Jansen R, Ledley FD. Production of discrete high specific activity DNA probes using polymerase chain reaction. Genet Anal Tech Appl. 1989;6:79–83. doi: 10.1016/0735-0651(89)90020-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Jaramillo ML, Afar DEH, Almazan G, Bell JC. Identification of tyrosine 620 as the major phosphorylation site of myelin-associated glycoprotein and its implication in interacting with signaling molecules. J Biol Chem. 1994;269:27240–27245. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Johnson P, Friedmann T. Limited bidirectional activity of two housekeeping gene promoters: human HPRT and PGK. Gene. 1990;88:207–213. doi: 10.1016/0378-1119(90)90033-n. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Johnson PW, Abramow-Newerly W, Seilheimer B, Sadoul R, Tropak MB, Arquint M, Dunn RJ, Schachner M, Roder JC. Recombinant myelin-associated glycoprotein confers neural adhesion and neurite outgrowth function. Neuron. 1989;3:377–385. doi: 10.1016/0896-6273(89)90262-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Lai C, Brow MA, Nave K-A, Noronha AB, Quarles RH, Bloom FE, Milner RJ, Sutcliffe JG. Two forms of 1B236/myelin-associated glycoprotein, a cell adhesion molecule for postnatal neural development, are produced by alternative splicing. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1987;84:4337–4341. doi: 10.1073/pnas.84.12.4337. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Lassmann H, Bartsch U, Montag D, Schachner M. Dying-back oligodendrogliopathy: a late sequel of myelin-associated glycoprotein deficiency. Glia. 1997;19:104–110. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Li C, Tropak MB, Gerlai R, Clapoff S, Abramow-Newerly W, Trapp B, Peterson A, Roder J. Myelination in the absence of myelin-associated glycoprotein. Nature. 1994;369:747–750. doi: 10.1038/369747a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Martini R, Schachner M. Immunoelectron microscopic localization of neural cell adhesion molecules (L1, N-CAM, and MAG) and their shared carbohydrate epitope and myelin basic protein in developing sciatic nerve. J Cell Biol. 1986;103:2439–2448. doi: 10.1083/jcb.103.6.2439. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Milner RJ, Lai C, Nave K, Lenoir D, Ogata J, Sutcliffe JG. Nucleotide sequences of two mRNAs for rat brain myelin proteolipid protein. Cell. 1985;42:931–939. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(85)90289-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Montag D, Giese KP, Bartsch U, Martini R, Lang Y, Blüthmann H, Karthigasan J, Kirschner DA, Wintergerst ES, Nave K, Zielasek J, Toyka KV, Lipp H, Schachner M. Mice deficient for the myelin-associated glycoprotein show subtle abnormalities in myelin. Neuron. 1994;13:229–246. doi: 10.1016/0896-6273(94)90472-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Nakano R, Fujita N, Sata S, Inuzuka T, Sakimura K, Ishiguro H, Mishina M, Miyatake T. Structure of mouse myelin-associated glycoprotein gene. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 1991;178:282–290. doi: 10.1016/0006-291x(91)91811-p. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Norton WT, Poduslo SE. Myelination in rat brain: method of myelin isolation. J Neurochem. 1973;21:749–757. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-4159.1973.tb07519.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Pedraza L, Frey AB, Hempstead BL, Colman DR, Salzer JL. Differential expression of MAG isoforms during development. J Neurosci Res. 1991;29:141–148. doi: 10.1002/jnr.490290202. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Popko B, Puckett C, Lai E, Shine HD, Readhead C, Takahashi N, Hunt SWI, Sidman RL, Hood L. Myelin deficient mice: expression of myelin basic protein and generation of mice with varying levels of myelin. Cell. 1987;48:713–721. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(87)90249-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Quarles RH. Myelin-associated glycoprotein in development and disease. Dev Neurosci. 1983;6:285–303. doi: 10.1159/000112356. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Salzer JL, Holmes WP, Colman DR. The amino acid sequences of the myelin-associated glycoproteins: homology to the immunoglobulin gene superfamily. J Cell Biol. 1987;104:957–965. doi: 10.1083/jcb.104.4.957. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Salzer JL, Pedraza L, Brown M, Struyk A, Afar D, Bell J. Structure and function of the myelin-associated glycoproteins. Ann NY Acad Sci. 1990;605:302–312. doi: 10.1111/j.1749-6632.1990.tb42404.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Samorajski T, Friede RL, Reimer PR. Hypomyelination in the quaking mouse. A model for the analysis of disturbed myelin formation. J Neuropathol Exp Neurol. 1970;29:507–523. doi: 10.1097/00005072-197010000-00001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Sidman RL, Dickie MM, Appel SH. Mutant mice (quaking and jimpy) with deficient myelination in the central nervous system. Science. 1964;144:309–311. doi: 10.1126/science.144.3616.309. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Stahl N, Harry J, Popko B. Quantitative analysis of myelin protein gene expression during development in the rat sciatic nerve. Mol Brain Res. 1990;8:209–212. doi: 10.1016/0169-328x(90)90018-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Sternberger NH, Quarles RH, Itoyama Y, Webster HD. Myelin-associated glycoprotein demonstrated immunocytochemically in myelin and myelin-forming cells of developing rat. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1979;76:1510–1514. doi: 10.1073/pnas.76.3.1510. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Sutcliffe JG, Milner RJ, Shinnick TM, Bloom FE. Identifying the protein products of brain-specific genes with antibodies to chemically synthesized peptides. Cell. 1983;33:671–682. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(83)90010-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Suzuki K, Zagoren JC. Quaking mouse: an ultrastructural study of the peripheral nerves. J Neurocytol. 1977;6:71–84. doi: 10.1007/BF01175415. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Trapp BD. Myelin-associated glycoprotein. Location and potential functions. Ann NY Acad Sci. 1990;605:29–43. doi: 10.1111/j.1749-6632.1990.tb42378.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Tropak MB, Johnson PW, Dunn RJ, Roder JC. Differential splicing of MAG transcripts during CNS and PNS development. Brain Res. 1988;464:143–155. doi: 10.1016/0169-328x(88)90006-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Umemori H, Sato S, Yagi T, Aizawa S, Yamamoto T. Initial events of myelination involve Fyn tyrosine kinase signalling. Nature. 1994;367:572–576. doi: 10.1038/367572a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Wisniewski H, Morell P. Quaking mouse: ultrastructural evidence for arrest of myelinogenesis. Brain Res. 1971;29:63–73. doi: 10.1016/0006-8993(71)90417-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]