Abstract

The Dmca1D gene encodes a Drosophilacalcium channel α1 subunit. We describe the first functional characterization of a mutation in this gene. This α1 subunit mediates the dihydropyridine-sensitive calcium channel current in larval muscle but does not contribute to the amiloride-sensitive current in that tissue. A mutation, which changes a highly conserved Cys to Tyr in transmembrane domain IS1, identifies a residue important for channel function not only inDrosophila muscle but also in mammalian cardiac channels. In both cases, mutations in this Cys residue slow channel activation and reduce expressed currents. Amino acid substitutions at this Cys position in the cardiac α1 subunit show that the size of the side chain, rather than its ability to form disulfide bonds, affects channel activation.

Keywords: amiloride, calcium channel expression, calcium channel mutant, cardiac calcium channel, channel activation, dihydropyridine, diltiazem, Drosophila melanogaster, larval muscle, two-electrode voltage clamp, Xenopus oocyte expression

Gene cloning studies have shown that both vertebrates and invertebrates have multiple genes encoding the α1 subunit of voltage-dependent calcium channels (Tsien et al., 1991; Hofmann et al., 1994; Catterall, 1995; Dunlap et al., 1995; Zheng et al., 1995; Smith et al., 1996; Eberl et al., 1998). This α1 subunit carries the structural determinants for the voltage sensor, the ion selectivity pore, and many drug binding sites (Catterall and Striessnig, 1992; Tang et al., 1993; Yang et al., 1993;Hofmann et al., 1994; Catterall, 1995; Varadi et al., 1995). There are four homologous repeats (designated I–IV, see Fig.1A), each consisting of six transmembrane domains (S1–S6) (Hofmann et al., 1994; Catterall, 1995). The loops between IIIS5 and IIIS6 and between IVS5 and IVS6 act as the calcium ion selectivity filter in the pore region of the channel (Heinemann et al., 1992; Tang et al., 1993; Yang et al., 1993), whereas the S4 domains play an important role in voltage sensing (García et al., 1997). Despite these common structural motifs, calcium channels differ greatly in their physiological properties. For example, it is well established that cardiac muscle L-type calcium channels activate rapidly, whereas those in skeletal muscle activate slowly (Tanabe et al., 1991; Nakai et al., 1994).

Fig. 1.

Functional characterization of the C629Y mutation in domain IS1 using a Drosophila and rabbit cardiac α1 subunit chimera (DR1). A, Location of the C629Y mutant change in the calcium channel α1subunit. The orientation of the α1 subunit in the membrane is shown diagrammatically. The N and C terminals are cytoplasmic. The position of the amino acid substitution (C629Y) in theAR66 allele is indicated by the arrow. This diagram represents the Drosophila and rabbit cardiac α1c subunit chimera (DR1), showingDrosophila sequences as filled segmentsin the transmembrane domains and heavy lines in the linker regions. The rabbit cardiac sequences are shown as open segments and light linker lines.B, Comparison of IS1 domains across α1subunit types. The missense mutation (C629Y) is found in a highly conserved region of domain IS1 and is caused by a substitution of A for G at nucleotide 1886 in the open reading frame (Zheng et al., 1995;Eberl et al., 1998). The top line shows the position of the C629Y mutation. The IS1 sequence in the DrosophilaDmca1D calcium channel α1 subunit (α1Dm) is compared with that of mammalian α1 subunits, including α1A rabbit brain P/Q type (Mori et al., 1991); α1B human brain N type (Williams et al., 1992); α1C rabbit heart and brain L type (Mikami et al., 1989); α1D rat brain L type (Hui et al., 1991); α1E rat brain E type (Soong et al., 1993); and α1S rabbit skeletal muscle L type (Tanabe et al., 1987). C–F, Oocytes were injected with 50 nl containing α1 chimera cRNA (C, F, wild type DR1; D, mutant DR1C629Y) plus α2–δ cRNA from rabbit skeletal muscle (Ellis et al., 1988) and β1b cRNA from rat brain (Pragnell et al., 1991). They were incubated for 2–4 d before two-electrode voltage-clamp recordings were made using barium as the charge carrier. Currents were elicited from a holding potential of −80 mV by 500 msec voltage steps as indicated. C, Representative current traces from the wild-type fly and rabbit cardiac α1C subunit chimera (DR1). Currents show fast activation. D, Representative currenttraces from oocytes expressing the DR1 chimera carrying the mutation C629Y. This mutation results in a greatly reduced current with markedly slower activation. E, Peak inward current versus test potential (I–V curves) for mutant (DR1C629Y) and wild-type (DR1) chimeras. The no α1 curve represents the endogenous current in oocytes injected with β1b and α2–δ cRNA only. N is the number of oocytes included in each average. Error bars show SEM. F, Representative currenttraces from oocytes expressing the wild-type DR1 chimera 2 d after injection. At this time, the injected cRNAs have not yet produced maximum current levels. The low level currents still show fast activation. The calibration shown below D applies toC, D, and F.

A key question with respect to channel function is how the channel opens in response to transmembrane voltage changes. A number of investigators have taken advantage of the functional differences between skeletal muscle and cardiac muscle α1 subunits and have used chimeric subunits to define regions responsible for differences in activation properties (Tanabe et al., 1991; Nakai et al., 1994; Wang et al., 1995). Taken together, these studies show that the amino acid composition of the S3 segment in repeat I (IS3) and the linker connecting IS3 and IS4 are critical for determining activation kinetics. In addition, repeats III and IV play a role in activation gating (Wang et al., 1995).

Although these and other chimera studies have proven extremely useful in defining functional domains within ion channels, their use is restricted to regions that differ between subunit subtypes. The most highly conserved domains cannot be approached in this manner because they are identical between subtypes, even across species. An alternative approach is illustrated by the use of point mutations in S4 segments and in leucine heptad motifs to demonstrate that highly conserved regions in repeats I and III but not in repeats II and IV are also involved in channel activation (García et al., 1997).

In this report, we use a complementary approach of in vivomutagenesis in Drosophila to dissect genetically different calcium channel currents and to identify a functionally important domain involved in channel activation. Using a point mutation, we demonstrate that the Dmca1D α1 subunit is responsible for the dihydropyridine-sensitive calcium channel current inDrosophila larval muscle but plays no role in the amiloride-sensitive current in that tissue. We define the functional consequences of mutational changes in a highly conserved IS1 site, showing effects on calcium channel current levels and on channel activation kinetics both in vivo and in a heterologous expression system. Finally, we demonstrate that an equivalent mutation has similar effects on the evolutionarily distant rabbit cardiac α1C subunit.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Genetic strains. Drosophila melanogastermutations and chromosomal aberrations in the Dmca1D gene [formerly called l(2)35Fa (Ashburner et al., 1990; Eberl et al., 1998)] were from John Roote (in the laboratory of Michael Ashburner, University of Cambridge, Cambridge, England). TheAR66 allele, carrying the C629Y mutation, is maintained as a heterozygous stock with the CyO, wg1en11 second chromosome balancer that carries an enhancer trap transposon insert. The balancer-bearing heterozygous larvae were identified histochemically after physiology by 5-bromo-4-chloro-3-indolyl-β-d-galactopyranoside staining (Ashburner, 1989) in the wingless pattern. The wild-type control strain is Canton-S. Flies were grown at 25°C on standard yeast–cornmeal–agar medium (Lewis, 1960).

Larval muscle electrophysiology. The preparation of mature third instar larvae was identical to that described by Jan and Jan (1976) except that the dissection saline was a hemolymph-like solution (Stewart et al., 1994) containing (in mm): 70 NaCl, 5 KCl, 1.5 CaCl2, 20 MgCl2, 10 NaHCO3, 5 trehalose, 115 sucrose, and 5 HEPES, pH 7.1. The recording saline contained (in mm): 70 NaCl, 5 KCl, 20 MgCl2, 10 NaHCO3, 5 trehalose, 115 sucrose, 5 HEPES, pH 7.1, 20 tetraethylammonium chloride (TEA), 1 4-aminopyridine (4-AP), 10 BaCl2, and 0.1 quinidine. TEA was from J. T. Baker (Phillipsburg, NJ); diltiazem was from Research Biochemicals (Natick, MA); and 4-AP, quinidine, and amiloride were from Sigma (St. Louis, MO). All drug solutions were stored at 4°C for <3 d.

Two-electrode voltage-clamp measurements were done at 3–5°C as described by Gielow et al. (1995) using the ventrolateral longitudinal muscle fibers 6, 7, 12, and 13 within abdominal segments 2–6. Most recordings came from fiber 12. Electrodes (15–25 MΩ) were pulled from thin-walled 1.0 mm borosilicate glass capillaries with a filament (A-M Systems, Everett, WA). Data were sampled at 5 kHz and filtered at 500 Hz.

To minimize run-down, we made all recordings within 20 min of the start of dissection. Leak current was subtracted on-line with a P/2 protocol. To avoid differences because of fiber size, we normalized currents to membrane capacitance measured from the current response elicited by a ramp wave [a modification of the method of Wu and Haugland (1985)].

cDNA expression constructs. The cardiac α1CΔN60 clone (Mikami et al., 1989; Wei et al., 1991) used as the wild-type control was α1c subcloned into the pAGA2 vector (from L. Birnbaumer, University of California, Los Angeles) following deletion of the first 60 amino acids to enhance expression (Wei et al., 1991). In this construct, C168 is equivalent to C629 in the Drosophila Dmca1D α1 subunit (see Fig. 1B). Mutants for the rabbit cardiac α1C subunit (C168S, C168Y, C168D, C168K, and C168G) were made by site-directed mutagenesis on a ClaI–SstI fragment using the Transformer site-directed mutagenesis kit (Clontech, Palo Alto, CA). The C168W mutation was made by PCR mutagenesis (Cormack, 1997). All mutants were sequenced to confirm that only the desired mutations were introduced.

The DR1 Drosophila Dmca1D and rabbit cardiac α1C chimera (see Fig. 1A) was assembled from a NcoI/SstI fragment of α1C in pAGA2 and a NcoI/SstI-digested PCR fragment from Dmca1D encoding amino acids 553–769 (Zheng et al., 1995). The two α1 segments are joined at a common SstI site found in domain IS5 in both. The mutant chimera DR1C629Y was made using PCR mutagenesis (Cormack, 1997) on aHpaI/SstI fragment to convert the C629 codon TGT to a Tyr codon (TAT).

The β1b construct (pCDβ1) was made by inserting the 1.9 kb HindIII (blunted)/BamHI fragment of rat brain β1 (Pragnell et al., 1991) into a PstI (blunted)/BglII cut vector pCDM6XL (Maricq et al., 1991) that has a 5′-untranslated region (UTR) from the Xenopusβ-globin gene. The α2–δ construct was modified by subcloning the EcoRI coding fragment of clone pSPCA1 (Ellis et al., 1988; Mikami et al., 1989) into vector pBScMXT (from L. Salkoff, Washington University, St. Louis, MO). This vector is a pBluescript (Stratagene, La Jolla, CA) modification with 5′- and 3′-UTR sequences from Xenopus β-globin.

Expression in Xenopus oocytes. All the cRNAs used in the study were synthesized using mMESSAGE mMACHINE kits (Ambion, Austin, TX). For the expression of the rabbit cardiac α1CΔN60 wild-type and point mutant subunits, each oocyte was injected with 50 nl containing 300 ng/μl α1and 90 ng/μl β1b. For the expression of theDrosophila and rabbit α1 subunit chimeras (wild-type and mutant), each oocyte was injected with 50 nl containing 200 ng/μl α1, 133 ng/μl α2–δ, and 60 ng/μl β1b. Oocytes were incubated in 0.5× L15 medium (Sigma) at 19°C for 1–4 d before recording. The bath solution for two-electrode voltage clamping contains (in mm): 40 Ba(OH)2, 50 NaOH, 1 KOH, 0.5 niflumic acid, 0.1 EGTA, and 5 HEPES, with pH adjusted to 7.45 with methanesulfonic acid (Perez-Reyes et al., 1992). Electrodes with resistances of 0.5–1 MΩ were filled with 3 m KCl in a 1% agarose cushion (Schreibmayer et al., 1994). Cells were held at −80 mV. Leak current was subtracted online with a P/4 protocol. The signal was digitized at 5 kHz and filtered at 3 kHz.

RESULTS

The AR66 mutation (C629Y) reduces dihydropyridine-sensitive calcium channel currents in larval muscle

Previous work has shown that the embryonic lethal geneDmca1D [formerly called l(2)35Fa] encodes an L-type calcium channel α1 subunit inDrosophila (Eberl et al., 1998). A null mutation in this gene, with a premature stop codon just after transmembrane domain IVS4, causes 100% embryonic lethality. A particularly useful allele, designated AR66, has a “leaky” phenotype allowing survival of some homozygotes to the adult stage. This partial viability suggests that Dmca1D calcium channels are made, but they may have reduced function. Complete sequencing of the Dmca1D cDNA showed that the leaky AR66 allele carries a Cys to Tyr missense mutation [residue C629 of Zheng et al. (1995)] in the IS1 transmembrane domain close to the extracellular side (Fig.1A, arrow) (Eberl et al., 1998). Interestingly, this Cys is highly conserved among all voltage-gated calcium channels (Fig. 1B), suggesting an important role in channel function.

The partial viability of the AR66 allele has allowed us to use two-electrode voltage clamping of Drosophila larval body wall muscles to look for mutant effects on the calcium channel currents described previously in these muscles (Gielow et al., 1995). Total current is significantly reduced in the homozygous mutants compared with wild type (Fig.2A). In heterozygotes, the total current density is intermediate between that of wild type and homozygous mutants. Thus, the total current is reduced in a gene dosage-dependent manner by the AR66 allele.

Fig. 2.

The C629Y mutation affects the dihydropyridine-sensitive D-current but not the amiloride-sensitive A-current in larval muscle. Calcium channel activity was measured in larval muscle by two-electrode voltage-clamp recordings made using barium as the charge carrier. Open squares are wild type; closed triangles are mutant heterozygotes (C629Y/+); and closed circles are mutant homozygotes (C629Y/C629Y). Error bars in A–D and F indicate SEM.A, Current–voltage relationship of total barium currents measured in larval muscle. Currents were elicited by 500 msec voltage steps in 10 mV increments from a holding potential of −100 mV. The number of larvae (L) used and the number of muscle fibers (F) recorded areL = 9 and F = 11 for wild type;L = 8 and F = 14 for mutant heterozygotes (C629Y/+); andL = 5 and F = 8 for mutant homozygotes (C629Y/C629Y).B, Current–voltage relationship of the dihydropyridine-sensitive current (D-current) isolated by recording in the presence of 1 mm amiloride at a holding potential of −100 mV. The difference between the wild type (L = 13; F = 17) and the homozygous mutant (L = 10; F = 13) persists in the absence of the amiloride-sensitive A-current. C, Current–voltage relationship of the dihydropyridine-sensitive current (D-current) isolated by recording with a holding potential of −30 mV. The difference between the wild type (L = 5;F = 7) and the homozygous mutant (L = 4; F = 7) again persists in the absence of the A-current. D, Current–voltage relationship of the amiloride-sensitive A-current recorded in the presence of 500 μm diltiazem at a holding potential of −100 mV. Under these recording conditions, there is no significant difference between the wild type (L = 5;F = 8) and the homozygous mutant (L = 6; F = 6).E, Averaged D-type barium current tracesfrom wild-type (upper) and homozygousC629Y mutant (lower) muscle fibers from the experiment in C. Seven traces are shown for test pulses of −30 to +30 mV. F, Comparison of the apparent time to reach the half maximum response of larval muscle D-type barium currents in wild type (open bar) and in homozygous mutants (closed bar). Recording conditions are described in C except thatVtest = 0 mV. The difference between the values of t1/2 for the wild type and the homozygous mutant is statistically significant (Student’st test; p = 0.006).

These total currents are comprised of two components (Gielow et al., 1995). One, which we name the D-current, is blocked by dihydropyridines and diltiazem. The other, referred to here as the A-current, is insensitive to dihydropyridines but is blocked by 1 mmamiloride and is inactivated at a holding potential of −30 mV. To determine whether one or both of these currents are affected in theAR66 allele, we first measured the D-currents by recording in the presence of 1 mm amiloride. As shown in Figure2B, the D-current in the homozygous mutant is significantly reduced compared with that in the wild type. A similar reduction in mutant compared with wild type is obtained when the D-currents are recorded after first inactivating the A-current by holding the cells at −30 mV (Fig. 2C). In contrast, when A-currents are recorded after blocking the D-current with 500 μm diltiazem, there is no significant difference between the mutant and wild type (Fig. 2D).

These results show conclusively that the Dmca1D gene encodes the calcium channel α1 subunit responsible for the dihydropyridine- and diltiazem-sensitive L-type calcium channel current in Drosophila larval body wall muscle. In addition, these experiments also show that mutations in the Dmca1D α1subunit do not affect the A-current in muscles, suggesting that the A-current is mediated via a genetically distinct α1subunit.

Averaged current traces (Fig. 2E) show that in the larval muscle there is also a slowing of D-current activation kinetics. The apparent time to reach half-maximum current (t1/2) in response to a depolarizing pulse to 0 mV was 22.0 ± 3.8 msec in the mutant compared with 9.2 ± 0.7 msec for the wild type (Fig. 2F). Thus, the mutant phenotype involves both a reduction in a specific current level and a slowing of channel activation kinetics.

Analysis of C629 mutations in a heterologous expression system

Because very little attention has been paid to the highly conserved IS1 region, we have taken advantage of the clues provided by the C629Y mutation to focus attention on its role in calcium channel function using expression in Xenopus oocytes where current levels and interactions with auxiliary subunits can be examined in a more controlled manner than is possible with the in vivomuscle preparation. Although we were unable to express full-lengthDmca1D cDNA in Xenopus oocytes, we were able to record currents from chimeric channels comprised of the fly Dmca1D α1 and the rabbit cardiac α1C subunit (Mikami et al., 1989). In this report, we use chimera DR1 that contains the N terminal (through IS5) from Drosophila, with the remaining sequence from the rabbit cardiac channel α1C(see Fig. 1A). When coexpressed with calcium channel β1b and α2–δ subunits, both the wild-type chimera (DR1) and the chimera carrying the C629Y mutation (DR1C629Y) gave detectable barium currents (Fig.1C–F).

There are two differences in the mutant compared with the wild-type channel. First, the magnitude of the macroscopic current is reduced approximately sixfold by the mutation, as shown by the representative current traces (compare Fig. 1C andD). This reduction is readily seen in the current/voltage (I–V) curves shown in Figure1E. The second difference between the mutant and wild type is that channel activation is significantly slower in the mutant (compare Fig. 1C and D). We uset1/2, the time to reach half maximum current amplitude in response to a 500 msec depolarizing pulse, to reflect activation kinetics. At a Vtest of 10 mV, t1/2 is 5.8 ± 0.2 msec for the wild type (N = 10) and 70 ± 1.7 msec for the mutant (N = 10).

This current reduction and slowing of channel activation is strongly reminiscent of the in vivo phenotype of the C629Y mutation in larval muscle. Because it has been reported (Adams et al., 1996) that calcium channel activation kinetics in myotubes is dependent on current density, we also recorded from oocytes expressing wild-type channels at a low level to obtain currents similar in size to that of the mutant (Fig. 1F). Compared with the C629Y mutant, the wild type has faster activation kinetics at low current levels, and there is no significant difference between thet1/2 at low current (t1/2= 6.1 ± 0.4 msec; N = 9) compared with that at high current (t1/2 = 5.8 ± 0.2 msec) levels. Thus, the slow kinetics of activation in the mutant is not caused by reduced peak current.

The conserved Cys in IS1 plays a role in mammalian cardiac α1C activation

Because the Cys at position 629 in the Drosophilaα1 subunit is conserved in all calcium channel α1 subunits cloned to date (Fig. 1B), we chose the well-studied rabbit cardiac α1C to determine whether the equivalent mutation (C168Y) (Mikami et al., 1989) has effects similar to those seen in the DR1 chimera. As shown in Figure3, A versus B, the currents are again dramatically reduced, and the time to reach half maximal amplitude is slower in the mutant (α1CΔN60C168Y; t1/2 = 17.3 ± 1.9 msec) than in the wild type (α1CΔN60; t1/2 = 6.8 ± 0.3 msec) (Fig.3A,B,J). Again expressing wild-type channels at low levels did not significantly alter activation kinetics (Fig. 3C,J, small; t1/2 = 6.2 ± 0.2 msec).

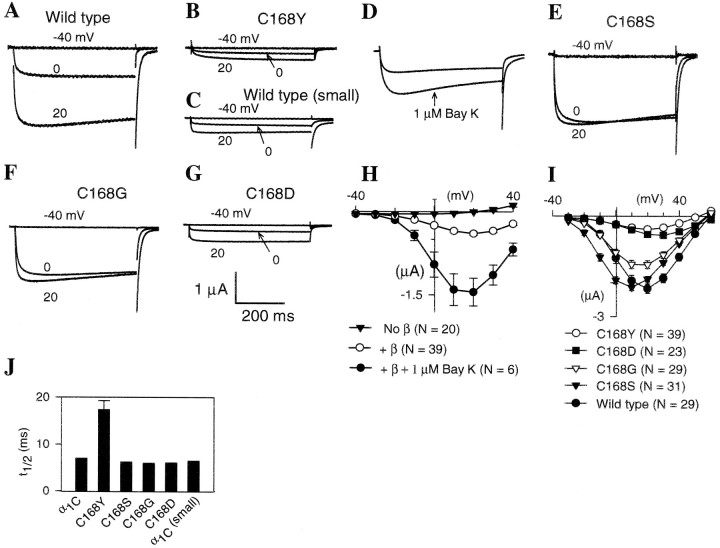

Fig. 3.

Functional characterization of amino acid substitutions introduced into the rabbit cardiac calcium channel α1CΔN60 subunit at the conserved Cys site in domain IS1. In the cardiac subunit, C168 is equivalent to C629 in theDrosophila Dmca1D α1 subunit. Oocytes were injected with 50 nl containing rabbit cardiac α1 and rat brain β1b. All oocytes were incubated for 3–4 d before recording, except those in C that were incubated only 1–2 d (A, C, rabbit cardiac α1CΔN60 subunit; B, E–G, mutant α1CΔN60 subunits with the Cys residue replaced as indicated). Currents shown were elicited from a holding potential of −80 mV using 500 msec voltage steps to −40, 0 and +20 mV.A–G, Representative current traces for oocytes expressing rabbit cardiac α1CΔN60 subunit variants. Oocytes were injected with truncated, wild-type α1CΔN60 (A, C) or one of the following mutations in α1CΔN60: C168Y (B, D), C168S (E), C168G (F), and C168D (G).D, Representative current traces from the mutant C168Y before (upper) and after (lower) treatment with 1 μm (−)-Bay K 8644. Vtest = 10 mV. H, Peak current versus test potential (I–Vcurves) for C168Y alone (filled inverted triangles), with β1 (open circles), and with β1 plus 1 μm(−)-Bay K 8644 (filled circles).I, Peak inward current versus test potential (I–V curves) for wild-type and mutant cardiac α1CΔN60 subunits. N is the number of oocytes included in each average. Error bars are SEM.J, Effect of amino acid substitutions in the cardiac α1CΔN60 subunit on activation kinetics. Using the same recordings analyzed in I, we plotted the time to reach the half maximal response (t1/2) for a 500 msec depolarizing pulse to +20 mV as the average ± SEM. Error bars are too small to see at this scale for the wild type and some of the mutants. Small, Smaller peak currents resulting from shorter incubation times of oocytes with wild-type cRNA.

The C168Y change alters the size of the side chain. To gain further insight as to how changes at this site affect current levels and activation kinetics, we made additional mutants in which charge (C168D and C168K), size (C168G and C168W), and ability to form a disulfide bond (C168S) were altered. The C168S mutation shows current levels and activation kinetics very similar to that of the wild type (Fig.3E,I,J), suggesting that the ability of Cys to form a disulfide bond does not affect these processes. However, the C168S change did produce a hyperpolarizing shift in the I–V curve (Fig.3E,I). Replacing Cys with a smaller amino acid (C168G) had no dramatic effect on activation kinetics (Fig. 3F,J) and had only a small effect on current amplitude (Fig.3F,I).

In contrast with these relatively minor effects, replacing this Cys with a charged residue or a bulky group was very disruptive. We were not able to record currents in the mutant C168W carrying a bulky side chain. Nor were we able to record currents in C168K carrying a positively charged side chain at this site. Replacement with a negatively charged residue (C168D) significantly reduced current (Fig.3G,I). However, it was without effect on activation kinetics (Fig.3G,J).

Calcium channel β subunits are known to enhance the expressed channel currents and to accelerate channel kinetics via a physical interaction with the intracellular loop between domains I and II in the α1 subunits (Pragnell et al., 1994). To determine whether the reduction in current level and the slowing of activation kinetics in the C168Y mutant was because of the disruption of α1–β interaction, we compared the α1CΔN60C168Y mutant expressed with and without the β1b subunit (Fig. 3H). The β1b subunit did stimulate current levels. Currents expressed in the absence of the β1b subunit were too small to determine whether there was a significant effect on activation kinetics. In addition, the maximum currents from the C168Y mutated channels are still enhanced 3.7-fold by the calcium channel agonist (−)-Bay K 8644 (Fig. 3D,H). Thus, the C168Y mutation does not block α1–β interaction or stimulation by dihydropyridine agonists.

DISCUSSION

Genetic separation of the two calcium channel currents in larval muscles

Calcium channels are involved in excitation–contraction coupling. In Drosophila larval body wall muscle where there are no sodium currents, calcium currents are also the major inward currents and are thus involved in the generation and propagation of action potentials. There are at least two genes encoding calcium channel pore-forming α1 subunits in Drosophila (Zheng et al., 1995; Smith et al., 1996). One (Dmca1D) encodes a subunit similar to mammalian dihydropyridine-sensitive L-type channels; the other (Dmca1A) encodes a subunit more similar to dihydropyridine-insensitive non-L-type channels. Null alleles in each of these genes result in embryonic lethality, demonstrating that they are not functionally redundant, but rather each plays a unique role in the organism (Smith et al., 1996; Eberl et al., 1998). We initially used viability, heart beat, and wing expansion phenotypes to show that mutations in Dmca1D have dramatic effects in the organism (Eberl et al., 1998). We report here the first functional characterization of the Dmca1D α1 subunit showing that mutations in this gene disrupt the dihydropyridine-sensitive current in larval muscle and are without effect on the amiloride-sensitive calcium channel current. It will be interesting to determine whether the amiloride-sensitive current in muscle is carried by the product of theDmca1A gene or by an as yet uncloned α1subunit.

In addition to the two genetically and pharmacologically distinct calcium currents, there are also four potassium currents that have been separated by genetic and pharmacological methods (Singh and Wu, 1989). With the ability to separate genetically the calcium currents, it is now possible to separate all known muscle currents. This complete separation of currents makes Drosophila an ideal system in which to study the effects of disrupting specific currents on the regulation of other channels in the same tissue. Because electrical activity is known to affect channel regulation at the transcriptional and translational levels (Offord and Catterall, 1989; Dargent and Couraud, 1990; Catterall, 1992; Dargent et al., 1994), the ability to disrupt genetically specific current activities in a controlled manner throughout development will provide a specificity that could not be attained in earlier studies.

Although Drosophila muscle has only two genetically distinct calcium currents, neurons are more diverse (Pelzer et al., 1989; Leung and Byerly, 1991). It is likely that Dmca1D contributes to one or more of these neuronal currents because our previous in situhybridization studies showed that the Dmca1D transcript is predominantly expressed throughout the nervous system (Zheng et al., 1995). In situ hybridization did not readily detect expression in muscle. Because our electrophysiological studies show that this gene plays an important role in muscle function, its previous lack of detection in muscle is likely because of the low abundance of transcripts in that tissue. The Drosophila Shakerpotassium channel transcripts are similarly readily detectable in neurons but not in muscle, although these channels clearly also play an important role in muscle (Pongs et al., 1988).

The AR66 mutation reveals a domain important for channel activation

The transmembrane segment IS1 has not been specifically associated with any known biophysical characteristic of calcium channels, and yet it is one of the most highly conserved domains in the α1subunit. It is these highly conserved domains that are likely to be most important for channel function and/or subunit interactions because they have been highly constrained throughout evolution. Using voltage-clamp studies of mutant larval muscle and functional expression in Xenopus oocytes, we provide the first evidence that changes in this domain affect current levels and channel activation kinetics in both Drosophila muscle and mammalian cardiac calcium channels. Previous work using chimeras between the slowly activating α1S from mammalian skeletal muscle and the fast-activating α1C from cardiac muscle showed that domain I was involved in channel activation (Tanabe et al., 1991). In these chimera studies, the region responsible for the difference in activation between these two channel types was localized to IS3 and the IS3/S4 linker (Nakai et al., 1994). Point mutations in S4 and in leucine heptad motifs have shown that these motifs in repeats I and III, but not in repeats II and IV, are involved in activation (García et al., 1997). Thus, in addition to the current study, a number of different studies have shown the involvement of other regions of repeat I in channel activation.

We found that blocking the ability of the conserved Cys in IS1 to potentially form disulfide bridges or substituting a smaller amino acid such as Gly in its place had very little effect on channel properties. However, adding a bulky group such as Tyr or a charged group such as Asp caused a dramatic reduction of currents. Interestingly, although the bulky group substitution caused an increase in the time to reach apparent half activation, the substitution of a charged residue was without effect on channel activation kinetics. Thus, this mutagenesis separates these two effects.

In models of sodium and potassium channel activation, the S4 domain is thought to act as a voltage sensor and to move outward in response to depolarization to open (activate) the channel (Larsson et al., 1996;Yang et al., 1996). It is possible that the presence of a bulky group in a nearby transmembrane domain interferes with this movement of S4. Another possibility is that this mutation affects coupling between voltage sensing and channel opening. The β subunit potentiates this process (Neely et al., 1993). Because stimulation by the β subunit is intact in the mutant (Fig. 3H), it is unlikely that the mutant affects this potentiation. Finally, the mutant may affect the opening process.

There are several possible mechanisms that might account for the reduction in calcium channel currents that we observe in both mutant larval muscle and in mutant channels expressed in Xenopusoocytes. One possibility is that the actual number of functional channels inserted into the membranes is reduced in the mutant relative to the wild type. Another possibility is that the mutation that slows channel activation may also reduce the stability of the activated state and thus reduce the maximum probability of channel opening. This effect could reduce the peak calcium channel currents with no associated change in channel number. Additional experiments involving measurement of channel numbers by ligand binding and/or with channel subtype-specific antibodies will be required to distinguish these possibilities.

Interestingly, there is a completely conserved Cys in voltage-gated sodium channels in a position equivalent to the Cys in the calcium channel IS1 domain. Our work raises the question of whether it plays a similar role in sodium channels.

These studies show that changes in channel properties described first in the larval muscle preparation are similar to those caused by the equivalent mutant change in the rabbit cardiac muscle α1Csubunit. Systematic screening for new leaky mutations for this calcium channel subunit should be useful for identifying other interesting functional domains of importance to channel function in vivo.

Footnotes

This work was supported by grants to L.M.H. from the National Institutes of Health (MERIT Award HL39369), from the BioAvenir program sponsored by Rhone Poulenc, the Ministry in charge of Research, and the Ministry in charge of Industry (France), and from the New York Affiliate of the American Heart Association. D.F.E. was supported by a Natural Sciences and Engineering Research Council of Canada Postdoctoral Fellowship. This work was made possible by the generous gifts of the following clones: α1C and α2–δ from X. Wei (deceased; Medical College of Georgia) and β1b from K. P. Campbell (University of Iowa). We thank John Roote, who was exceptionally helpful, and Jeff Hall, Melissa Coleman, and Jorge Golowasch for comments on earlier versions of this manuscript.

D.R., H.X., and D.F.E. contributed equally to this work.

Correspondence should be addressed to Dr. Linda M. Hall, Department of Biochemical Pharmacology, 329 Hochstetter Hall, State University of New York at Buffalo, Buffalo, NY 14260-1200.

Dr. Ren’s present address: Harvard Medical School, Room 1309 Enders Building, 320 Longwood Avenue, Boston, MA 02115.

REFERENCES

- 1.Adams BA, Tanabe T, Beam KG. Ca2+ current activation rate correlates with α1 subunit density. Biophys J. 1996;71:156–162. doi: 10.1016/S0006-3495(96)79212-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Ashburner M. Drosophila: a laboratory manual, pp 163, 167. Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory; Cold Spring Harbor, NY: 1989. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Ashburner M, Thompson P, Roote J, Lasko PF, Grau Y, El Messal M, Roth S, Simpson P. The genetics of a small autosomal region of Drosophila melanogaster containing the structural gene for alcohol dehydrogenase. VII. Characterization of the region around the snail and cactus loci. Genetics. 1990;126:679–694. doi: 10.1093/genetics/126.3.679. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Catterall WA. Cellular and molecular biology of voltage-gated sodium channels. Physiol Rev. 1992;72:S15–S48. doi: 10.1152/physrev.1992.72.suppl_4.S15. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Catterall WA. Structure and function of voltage-gated ion channels. Annu Rev Biochem. 1995;64:493–531. doi: 10.1146/annurev.bi.64.070195.002425. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Catterall WA, Striessnig J. Receptor sites for Ca2+ channel antagonists. Trends Pharmacol. 1992;13:256–262. doi: 10.1016/0165-6147(92)90079-l. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Cormack B. Directed mutagenesis using the polymerase chain reaction. In: Ausubel FM, Brent R, Kingston RE, Moore DD, Seidman JG, Smith JA, Struhl K, editors. Current protocols in molecular biology. Wiley; New York: 1997. pp. 8.5.1–8.5.10. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Dargent B, Couraud F. Down-regulation of voltage-dependent sodium channels initiated by sodium influx in developing neurons. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1990;87:5907–5911. doi: 10.1073/pnas.87.15.5907. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Dargent B, Paillart C, Carlier E, Alcaraz G, Martin-Eauclaire MF, Couraud F. Sodium channel internalization in developing neurons. Neuron. 1994;13:683–690. doi: 10.1016/0896-6273(94)90035-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Dunlap K, Luebke JI, Turner TJ. Exocytotic Ca2+ channels in mammalian central neurons. Trends Neurosci. 1995;18:89–98. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Eberl DF, Ren D, Feng G, Lorenz LJ, Van Vactor D, Hall LM (1998) Genetic and developmental characterization ofDmca1D, a calcium channel α1 subunit gene inDrosophila melanogaster. Genetics, in press. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 12.Ellis SB, Williams ME, Ways NR, Brenner R, Sharp AH, Leung AT, Campbell KP, McKenna E, Koch WJ, Hui A, Schwartz A, Harpold MM. Sequence and expression of mRNAs encoding the α1 and α2 subunits of a DHP-sensitive calcium channel. Science. 1988;241:1661–1664. doi: 10.1126/science.2458626. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.García J, Nakai J, Imoto K, Beam KG. Role of S4 segments and the leucine heptad motif in the activation of an L-type calcium channel. Biophys J. 1997;72:2515–2523. doi: 10.1016/S0006-3495(97)78896-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Gielow ML, Gu G-G, Singh S. Resolution and pharmacological analysis of the voltage-dependent calcium channels of Drosophila larval muscles. J Neurosci. 1995;15:6085–6093. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.15-09-06085.1995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Heinemann SH, Terlau H, Stühmer W, Imoto K, Numa S. Calcium channel characteristics conferred on the sodium channel by single mutations. Nature. 1992;356:441–443. doi: 10.1038/356441a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Hofmann F, Biel M, Flockerzi V. Molecular basis for Ca2+ channel diversity. Annu Rev Neurosci. 1994;17:399–418. doi: 10.1146/annurev.ne.17.030194.002151. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Hui A, Ellinor PT, Krizanova O, Wang J-J, Diebold RJ, Schwartz A. Molecular cloning of multiple subtypes of a novel rat brain isoform of the α1 subunit of the voltage-dependent calcium channel. Neuron. 1991;7:35–44. doi: 10.1016/0896-6273(91)90072-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Jan LY, Jan YN. Properties of the larval neuromuscular junction in Drosophila melanogaster. J Physiol (Lond) 1976;262:189–214. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.1976.sp011592. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Larsson HP, Baker OS, Dhillon DS, Isacoff EY. Transmembrane movement of the Shaker K+ channel S4. Neuron. 1996;16:387–397. doi: 10.1016/s0896-6273(00)80056-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Leung H-T, Byerly L. Characterization of single calcium channels in Drosophila embryonic nerve and muscle cells. J Neurosci. 1991;11:3047–3059. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.11-10-03047.1991. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Lewis EB. A new standard food medium. Dros Inform Serv. 1960;34:117–118. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Maricq AV, Peterson AS, Brake AJ, Myers RM, Julius D. Primary structure and functional expression of the 5HT3 receptor, a serotonin-gated ion channel. Science. 1991;254:432–437. doi: 10.1126/science.1718042. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Mikami A, Imoto K, Tanabe T, Niidome T, Mori Y, Takeshima H, Narumiya S, Numa S. Primary structure and functional expression of the cardiac dihydropyridine-sensitive calcium channel. Nature. 1989;340:230–233. doi: 10.1038/340230a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Mori Y, Friedrich T, Kim M-S, Mikami A, Nakai J, Ruth P, Bosse E, Hofmann F, Flockerzi V, Furuichi T, Mikoshiba K, Imoto K, Tanabe T, Numa S. Primary structure and functional expression from complementary DNA of a brain calcium channel. Nature. 1991;350:398–402. doi: 10.1038/350398a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Nakai J, Adams BA, Imoto K, Beam KG. Critical roles of the S3 segment and S3–S4 linker of repeat I in activation of L-type calcium channels. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1994;91:1014–1018. doi: 10.1073/pnas.91.3.1014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Neely A, Wei X, Olcese R, Birnbaumer L, Stefani E. Potentiation by the β subunit of the ratio of the ionic current to the charge movement in the cardiac calcium channel. Science. 1993;262:575–578. doi: 10.1126/science.8211185. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Offord J, Catterall WA. Electrical activity, cAMP, and cytosolic calcium regulate mRNA encoding sodium channel α subunits in rat muscle cells. Neuron. 1989;2:1447–1452. doi: 10.1016/0896-6273(89)90190-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Pelzer S, Barhanin J, Pauron D, Trautwein W, Lazdunski M, Pelzer D. Diversity and novel pharmacological properties of Ca2+ channels in Drosophila brain membranes. EMBO J. 1989;8:2365–2371. doi: 10.1002/j.1460-2075.1989.tb08365.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Perez-Reyes E, Castellano A, Kim HS, Bertrand P, Baggstrom E, Lacerda AE, Wei X, Birnbaumer L. Cloning and expression of a cardiac/brain β subunit of the L-type calcium channel. J Biol Chem. 1992;267:1792–1797. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Pongs O, Kecskemethy N, Müller R, Krah-Jentgens I, Baumann A, Kiltz HH, Canal I, Llamazares S, Ferrus A. Shaker encodes a family of putative potassium channel proteins in the nervous system of Drosophila. EMBO J. 1988;7:1087–1096. doi: 10.1002/j.1460-2075.1988.tb02917.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Pragnell M, Sakamoto J, Jay SD, Campbell KP. Cloning and tissue-specific expression of the brain calcium channel β-subunit. FEBS Lett. 1991;291:253–258. doi: 10.1016/0014-5793(91)81296-k. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Pragnell M, De Waard M, Mori Y, Tanabe T, Snutch TP, Campbell KP. Calcium channel β-subunit binds to a conserved motif in the I–II cytoplasmic linker of the α1-subunit. Nature. 1994;368:67–70. doi: 10.1038/368067a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Schreibmayer W, Lester HA, Dascal N. Voltage clamping of Xenopus laevis oocytes utilizing agarose-cushion electrodes. Pflügers Arch. 1994;426:453–458. doi: 10.1007/BF00388310. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Singh S, Wu C-F. Complete separation of four potassium currents in Drosophila. Neuron. 1989;2:1325–1329. doi: 10.1016/0896-6273(89)90070-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Smith LA, Wang XJ, Peixoto AA, Neumann EK, Hall LM, Hall JC. A Drosophila calcium channel α1 subunit gene maps to a genetic locus associated with behavioral and visual defects. J Neurosci. 1996;16:7868–7879. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.16-24-07868.1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Soong TW, Stea A, Hodson CD, Dubel SJ, Vincent SR, Snutch TP. Structure and functional expression of a member of the low voltage-activated calcium channel family. Science. 1993;260:1133–1136. doi: 10.1126/science.8388125. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Stewart BA, Atwood HL, Renger JJ, Wang J, Wu C-F. Improved stability of Drosophila larval neuromuscular preparations in haemolymph-like physiological solutions. J Comp Physiol [A] 1994;175:179–191. doi: 10.1007/BF00215114. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Tanabe T, Takeshima H, Mikami A, Flockerzi V, Takahashi H, Kangawa K, Kojima M, Matsuo H, Hirose T, Numa S. Primary structure of the receptor for calcium channel blockers from skeletal muscle. Nature. 1987;328:313–318. doi: 10.1038/328313a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Tanabe T, Adams BA, Numa S, Beam KG. Repeat I of the dihydropyridine receptor is critical in determining calcium channel activation kinetics. Nature. 1991;352:800–803. doi: 10.1038/352800a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Tang S, Mikala G, Bahinski A, Yatani A, Varadi G, Schwartz A. Molecular localization of ion selectivity sites within the pore of a human L-type cardiac calcium channel. J Biol Chem. 1993;268:13026–13029. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Tsien RW, Ellinor PT, Horne WA. Molecular diversity of voltage-dependent Ca2+ channels. Trends Pharmacol. 1991;12:349–354. doi: 10.1016/0165-6147(91)90595-j. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Varadi G, Mori Y, Mikala G, Schwartz A. Molecular determinants of Ca2+ channel function and drug action. Trends Pharmacol. 1995;16:43–49. doi: 10.1016/s0165-6147(00)88977-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Wang Z, Grabner M, Berjukow B, Savchenko A, Glossmann H, Hering S. Chimeric L-type Ca2+ channels expressed in Xenopus laevis oocytes reveal role of repeats III and IV in activation gating. J Physiol (Lond) 1995;486:131–137. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.1995.sp020797. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Wei X, Perez-Reyes E, Lacerda AE, Schuster G, Brown AM, Birnbaumer L. Heterologous regulation of the cardiac Ca2+ channel α1 subunit by skeletal muscle β and γ subunits. Implications for the structure of cardiac L-type Ca2+ channels. J Biol Chem. 1991;266:21943–21947. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Williams ME, Brust PF, Feldman DH, Patthi S, Simerson S, Maroufi A, McCue AF, Veliçelebi G, Ellis SB, Harpold MM. Structure and functional expression of an ω-conotoxin-sensitive human N-type calcium channel. Science. 1992;257:389–395. doi: 10.1126/science.1321501. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Wu C-F, Haugland FN. Voltage clamp analysis of membrane currents in larval muscle fibers of Drosophila: alteration of potassium currents in Shaker mutants. J Neurosci. 1985;5:2626–2640. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.05-10-02626.1985. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Yang J, Ellinor PT, Sather WA, Zhang J-F, Tsien RW. Molecular determinants of Ca2+ selectivity and ion permeation in L-type Ca2+ channels. Nature. 1993;366:158–161. doi: 10.1038/366158a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Yang N, George AL, Jr, Horn R. Molecular basis of charge movement in voltage-gated sodium channels. Neuron. 1996;16:113–122. doi: 10.1016/s0896-6273(00)80028-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Zheng W, Feng G, Ren D, Eberl DF, Hannan F, Dubald M, Hall LM. Cloning and characterization of a calcium channel α1 subunit from Drosophila melanogaster with similarity to the rat brain type D isoform. J Neurosci. 1995;15:1132–1143. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.15-02-01132.1995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]