Abstract

Studies on the amyloid precursor protein (APP) have suggested that it may be neuroprotective against amyloid-β (Aβ) toxicity and oxidative stress. However, these findings have been obtained from either transfection of cell lines and mice that overexpress human APP isoforms or pretreatment of APP-expressing primary neurons with exogenous soluble APP. The neuroprotective role of endogenously expressed APP in neurons exposed to Aβ or oxidative stress has not been determined. This was investigated using primary cortical and cerebellar neuronal cultures established from APP knock-out (APP−/−) and wild-type (APP+/+) mice. Differences in susceptibility to Aβ toxicity or oxidative stress were not found between APP−/− and APP+/+ neurons. This observation may reflect the expression of the amyloid precursor-like proteins 1 and 2 (APLP1 and APLP2) molecules and supports the theory that APP and the APLPs may have similar functional activities. Increased expression of cell-associated APLP2, but not APLP1, was detected in Aβ-treated APP−/− and APP+/+ cultures but not in H2O2-treated cultures. This suggests that the Aβ toxicity pathway differs from other general forms of oxidative stress. These findings show that Aβ toxicity does not require an interaction of the Aβ peptide with the parental molecule (APP) and is therefore distinct from prion protein neurotoxicity that is dependent on the expression of the parental cellular prion protein.

Keywords: Aβ25–35, cortical neurons, neurotoxicity, APP, Alzheimer’s disease, knock-out mice

An Alzheimer’s disease (AD) brain contains numerous plaques composed of the amyloid-β (Aβ) amyloid peptide (βA4), which is derived from the proteolytic processing of the amyloid precursor protein (APP) (Glenner and Wong, 1984; Masters et al., 1985; Kang et al., 1987). APP is a transmembrane glycoprotein that undergoes extensive alternative splicing (Sandbrink et al., 1994). The APP751 and -770 isoforms contain a Kunitz-type protease inhibitor domain (Tanzi et al., 1988), whereas APP695, which lacks this domain, is expressed at high levels in CNS neurons (Koo et al., 1990). APP is processed by endoproteases called secretases. Constitutive cleavage within the Aβ domain by α-secretase results in the generation of secreted APP (sAPPα). Alternatively, APP can be cleaved by β- and γ-secretases to generate Aβ (for review, see Mattson, 1997). APP is one of a multigene family that contains at least two other homologs known as amyloid precursor-like proteins 1 and 2 (APLP1 and APLP2) (Wasco et al., 1992; Sprecher et al., 1993; Slunt et al., 1994). The APLPs contain most of the domains and motifs of APP, including a hydrophobic membrane-spanning domain, N-glycosylation sites, copper and zinc binding domains, and the KPI domain (only APLP2). Neither APLP1 nor APLP2 contains the Aβ region and cannot directly contribute to Aβ deposition in Alzheimer’s disease. The similarities between APP and APLP (particularly APLP2) suggest that the APLPs could share and compensate for the function of APP.

A number of activities for neuronal APP have been identified. In vitro studies suggest that membrane-associated and secreted APP have an important role in promoting cell-substratum adhesion, neurite extension and development, and synaptic function in neurons (Schubert et al., 1989; Milward et al., 1992; Salvietti et al., 1996). In addition to a neuritogenic role, APP may also have a neuroprotective effect. Neurotrophic factors and neuronal injury upregulate APP expression and induce secretion of sAPP (Nakamura et al., 1992; Mattson et al., 1993b; Ohyagi and Tabira, 1993; Schubert and Behl, 1993). The addition of sAPP to culture medium protects cortical and hippocampal neurons from neurotoxic insults induced by hypoglycemia and excitotoxic amino acids. It is believed that sAPP acts by stabilizing intracellular Ca2+ levels and reducing oxidative stress (Mattson et al., 1993b; Goodman and Mattson, 1994; Barger et al., 1995). Transfecting human cDNA into cell lines and transgenic mice can result in protection against oxidative stress and increased resistance to excitotoxicity (Schubert and Behl, 1993; Mucke et al., 1996). However, increased ischemic brain damage has been reported in transgenic mice that overexpress APP (Zhang et al., 1997). The pathways involved in these effects are yet to be determined.

The neuroprotective role of sAPP may also extend to Aβ toxicity. The Aβ peptides (Aβ1–40 and Aβ1–42) can be toxic in vitro to a wide variety of neuronal cell types through disruption of Ca2+ homeostasis and increased oxidative stress (Yankner et al., 1989, 1990; Roher et al., 1991; Mattson et al., 1993a;Pike et al., 1993). In addition, Aβ can potentiate excitotoxic, hypoglycemic, and oxidative damage to neurons (Koh et al., 1990;Lockhart et al., 1994). Treatment of rat hippocampal neurons with sAPP results in a protective effect against Aβ toxicity (Goodman and Mattson, 1994) by reducing Ca2+ influx and levels of reactive oxygen species. Similarly, it was shown that when the B103 neuronal cell line was transfected with human APP695 or APP751 it was significantly more resistant to Aβ toxicity compared with controls (Schubert and Behl, 1993). The increased survival of APP-expressing cells may reflect a heightened resistance to oxidative stress.

These studies indicate a role for APP in antioxidant responses. In AD, the aberrant processing of APP may not only result in increased deposition of toxic Aβ but could also reduce the normal protective function of sAPP. At present, there are no published studies investigating the role of endogenous APP expression with respect to toxicity in neuronal cells. To determine whether endogenous APP expression alters the response to oxidative stress in neurons, we have established primary neuronal cultures from APP knock-out (APP−/−) and wild-type (APP+/+) mice and exposed them to toxic Aβ peptide and different oxidative stresses. In contrast to previous experiments with exogenous sAPP or transfected cell lines, our study did not identify differences in cell survival in APP−/− compared with APP+/+ neurons when both were exposed to various oxidative insults. This result may reflect expression of the APLP molecules that were detected in the neuronal cultures. Because of their close homology, the APLPs may have a function similar to that of APP and hence possess the ability to compensate for the absence of APP.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Materials. Poly-l-lysine, 3,[4,5 dimethylthiazol-2-yl]-2,5 diphenyltetrazolium bromide (MTT), cytosine arabinofuranoside (Ara C), basic FGF (bFGF), xanthine oxidase, phenylmethylsulfonyl fluoride (PMSF), and protease inhibitors were purchased from Sigma (St. Louis, MO). Glutamine, glutamate, glucose, and gentamycin sulfate were obtained from Life Technologies (Gaithersburg, MD). Aβ25–35 was obtained from Auspep Pty. Ltd. Aβ1–42 was a gift from Dr. Ashley Bush (Massachusetts General Hospital, Boston). Fetal calf serum (FCS) and horse serum (HS) were from the Commonwealth Serum Laboratories. Xanthine was obtained from Boehringer Ingelheim. For immunoblotting, 22C11 (anti-APP/APLP2) was obtained from Boehringer Ingelheim. 25104 (anti-APLP1) is a rabbit polyclonal antiserum raised to an unconjugated peptide corresponding to APLP1 amino acids 499–557 (Paliga et al., 1997); 95/11 (anti-APLP2) is a rabbit polyclonal antiserum raised to recombinant APLP2 amino acids 28–693 (Wasco et al., 1993) expressed in Pichia pastoris(see below).

Primary neuronal cultures. The generation of the APP−/− mice has been described previously (Zheng et al., 1995). Control mice (C57BL6J × 129/Sv) correspond to genetically matched mice from which the APP−/−mice were derived. Primary neuronal cultures of cerebral cortex and cerebellum were established from APP−/− and APP+/+ mice. Cortices from embryonic day 14 (E14) and cerebella from postnatal day 5–6 (P5–6) mice were removed, dissected free of meninges, and dissociated in 0.025% trypsin. Cortical cells were plated onto poly-l-lysine (5 μg/ml)-coated 24-well plates (Greiner) at a density of 450,000 cells/cm2 (high density) or 250,000 cells/cm2 (low density) in MEM (Life Technologies) supplemented with 10% FCS, 10% HS, 2 mm glutamine, 25 mm KCl, and 5 gm/l glucose. Cerebellar granule neurons (CGNs) were plated on identical plates at 350,000 cells/cm2 in BME (Life Technologies) supplemented with 10% FCS, 2 mm glutamine, and 25 mm KCl. Gentamycin sulfate (100 μg/ml) was added to all plating media, and cultures were maintained at 37°C in 5% CO2. For lactate dehydrogenase (LDH) assays and some MTT assays, cortical cultures were placed in MEM with N2 supplements (Life Technologies) at day 3 in vitro. Ara C (10 μm) was added at day 1 (CGN cultures) or day 6 (cortical cultures). Where stated, bFGF (10 ng/ml) was added to cultures at day 1 in vitro. Neuronal purity of cultures was ∼90–95% for cortical cultures and 96–98% for the cerebellar granule cell cultures.

Measurement of neuronal cell viability and cell death. Cell viability or redox potential was determined using the MTT assay. Culture medium was replaced with 0.6 mg/ml MTT in control salt solution (Locke’s buffer containing 154 mm NaCl, 5.6 mmKCl, 2.3 mm CaCl2, 1.0 mmMgCl2, 3.6 mm NaHCO3, 5 mm HEPES, and 5.6 mm glucose, pH 7.4) for 2 hr. The MTT was removed and cells were solubilized with dimethyl sulfoxide. Aliquots (100 μl) were measured with a spectrophotometer at 570 nm. Cell death was determined from culture supernatants free of serum and cell debris using an LDH Cytotoxicity Detection Kit (Boehringer Ingelheim) according to manufacturer’s instructions. All cell survival assays were performed with the MTT assay unless stated otherwise.

Induction of oxidative stress. Aβ25–35 was prepared as a 1 mm stock solution in dH2O and aged for 2–3 d at 37°C. Aβ1–42 was prepared by dissolving the peptide in dH2O, sonicating, and centrifuging for 5 min in a microfuge. The supernatant was adjusted to 200 μm and added to cultures. After 3 d in culture, neuronal cells were exposed to Aβ25–35 or Aβ1–42. Neuronal redox activity and cell death were determined after 4 d of exposure to the peptide using the MTT and LDH assays, respectively.

Intracellular peroxide-associated oxidative stress was induced by addition of glutamate to immature cortical cultures (day 3 in vitro) for 24 hr. Extracellular peroxide toxicity was induced in cortical cultures by adding H2O2 to culture media for 24 hr at day 4 in vitro. Superoxide anion production was generated in cell culture medium at days 4 and 6in vitro by adding 50 μm xanthine and increasing concentrations of xanthine oxidase to culture wells for 24 hr. Hypoglycemia was induced by washing cultures twice with glucose-free Locke’s buffer followed by incubation in Locke’s without glucose (5.6 mm, pH 7.4). Data represent the SEM of experiments performed in three to four cultures measured in triplicate.

Recombinant APP, APLP1, and APLP2. Recombinant secreted APP751, APLP2, and APLP1 were produced in the methylotrophic yeastPichia pastoris. APP751 has been described previously (Henry et al., 1997). APLP2 was amplified by the PCR as a 1998 base pair DNA fragment corresponding to residues 28–693 of human APLP2. Human APLP2 cDNA (Wasco et al., 1993) was used as the PCR template (gift of Dr. Wilma Wasco, Massachusetts Institute of Technology, Cambridge, MA). The oligonucleotides used were CCG AAT TCT TGG CGC TGG CCG GCT ACA and CCC CTC TAG AAC TGC TAC TCA GAC TGA AGT C. The PCR fragment was digested with EcoRI and XbaI and ligated into EcoRI/XbaI-digested pIC9 (Invitrogen, San Diego, CA). Human APLP1, corresponding to amino acids 34–650, was amplified by PCR with the primers AAG CTT ACG TAC AGC CCG CCA TCG GGA GCC TG and GGC AGC GGA AGG GCA CAA C. The PCR fragment was digested with SnaB I and ScaI and cloned into pIC9. The protein was expressed in the GS115 strain as described previously (Henry et al., 1997).

Quantitative immunoblotting of APP, APLP1, and APLP2.Cortical cultures (day 2 or 3 in vitro) were exposed to Aβ25–35 (10 μm) or H2O2 (25 μm) for 24 hr and then homogenized in TES buffer (20 mm Tris, pH 7.4, 1 mm EDTA, 0.25 msucrose) and the protease inhibitors pepstatin, aprotinin, and leupeptin at 10 μg/ml and 0.1 mm PMSF. Protein determination was performed using a BCA assay kit (Pierce, Rockford, IL), and normalized protein samples were separated on a 12% SDS-PAGE gel (25 μg/lane) at 30 mA/gel. Separated proteins were transferred to PVDF membrane overnight, blocked overnight in 0.5% hydrolyzed casein, and probed for 1 hr at room temperature (RT) with 22C11 (1:2000), 25104 (1:1000), or 95/11 (1:1000) in Tris-buffered saline (TBST) (10 mm Tris, 0.9% NaCl, and 0.1% Tween-20, pH 7.5). A secondary antibody [1:2000, rabbit anti-mouse immunoglobulins (Amersham, Arlington Heights, IL)] was applied to the 22C11-probed membrane for 1 hr at RT. Blots were then probed with125I-protein-A (Amersham) for 1 hr at RT (0.1 μCi/ml in 0.5% casein). Blots were washed three times (10 min each) between each probing step with TBST, pH 8.5. Blots were analyzed and quantitated on a Fujix BAS 1000 Phosphorimager using MacBas1 software.

RESULTS

APP−/− neuronal cell cultures

To determine whether there were differences in basal cell survival in neurons from APP−/− and APP+/+ mice, we established primary cortical and cerebellar neuronal cultures from mice at E14 and P5, respectively. As shown in Table 1, growth of APP−/− cortical neurons in serum-containing media (up to 7 d) or in serum-free N2-supplemented media (up to 14 d) showed no significant difference in cell survival compared with APP+/+ neurons. The growth of cerebellar neurons in serum-containing media also revealed no differences between APP−/− and wild-type mice. We conclude that growth and survival of primary neuronal cultures at high or low density, with and without serum (after day 3 in vitro) does not differ significantly between APP−/− and APP+/+ neurons under basal conditions.

Table 1.

APP−/− cortical and cerebellar neurons reveal no difference in survival at basal growth conditions compared with APP+/+ neurons using the MTT assay

| Days in vitro | Media supplement | % Survival compared with APP+/+ neurons | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| High density Low density | Cerebellar | |||

| Cortical | ||||

| 1 | Serum | 101 ± 5 | 103 ± 7 | 102 ± 2 |

| 3 | Serum | 101 ± 5 | 98 ± 4 | 101 ± 1 |

| 7 | Serum | 100 ± 1 | 97 ± 5 | 99 ± 3 |

| 7 | N2 | 104 ± 4 | 102 ± 4 | ND1-a |

| 14 | N2 | 105 ± 2 | 108 ± 3 | 97 ± 5 |

Primary cortical neurons were grown at high (450,000 cells/cm2) and low (250,000 cells/cm2) density in MEM supplemented with 10% FCS and 10% HS for up to 7 d or in MEM and N2 from day 3 to day 14 in vitro. Primary cerebellar granule neurons were grown in BME with 10% FCS for up to 7 din vitro and in N2 for up to 14 d.

ND, Not done.

Aβ25–35 and Aβ1–42 toxicity in APP−/−and APP+/+ cortical neuronal cultures

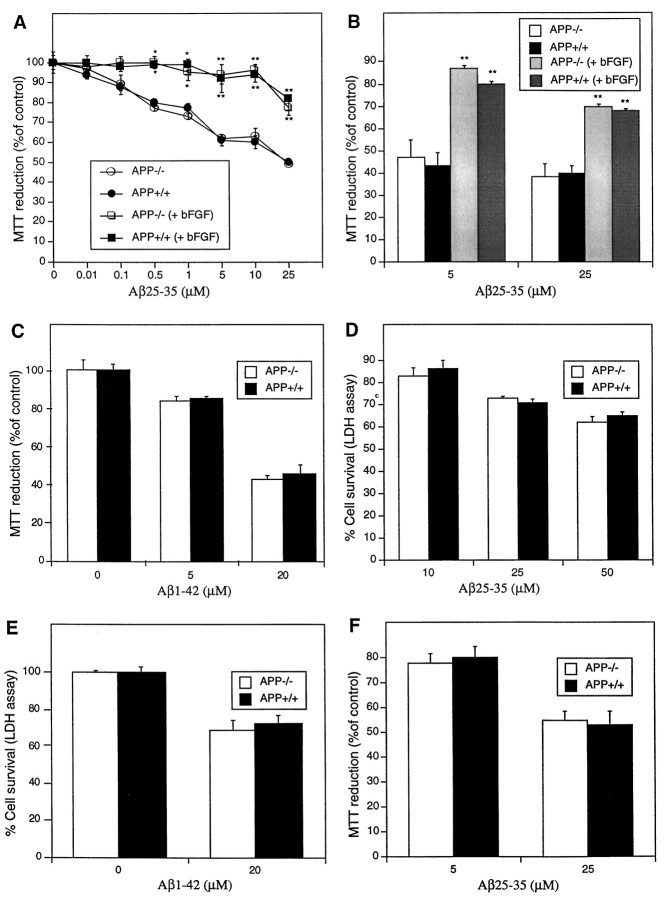

To determine whether the APP molecule is directly involved in neuronal responses to Aβ peptide-mediated toxicity, we added Aβ25–35 or Aβ1–42 peptide to 3-d-old cultures of APP−/− and APP+/+ cortical neurons. The Aβ25–35 peptide was aged at 37°C for 2–3 d in dH2O and showed considerable fibril formation (data not shown). The Aβ1–42 peptide also produced considerable fibril formation when prepared as described in Materials and Methods. Cultures were assayed for neuronal redox activity using the MTT assay after exposure for 4 d to Aβ peptides at different concentrations. The intracellular reduction of MTT to insoluble product is rapidly and significantly inhibited in many types of neurons treated with Aβ peptides (Abe and Kimura, 1996). With this treatment regimen, 0.5 μm Aβ25–35 induced a significant decline in MTT reduction compared with non-Aβ-treated control cultures (Fig.1A). Increasing concentrations of Aβ resulted in a further loss of MTT reduction up to 25 μm Aβ, the highest concentration used. A significant difference was not observed in MTT reduction between APP−/− and APP+/+ cortical cultures (Fig. 1A). Because APP expression and resistance to oxidative stress could be affected by cell density, low-density (250,000 cells/cm2) primary cortical neuronal cultures were also established and exposed to Aβ25–35. Measurement of cell viability after exposure for 4 d revealed no difference between APP−/− and APP+/+ cultures (Fig. 1B). Similar results were obtained when cultures were exposed to Aβ1–42. No significant difference was observed in MTT readings between APP−/− and APP+/+ neurons after 4 d exposure to 5 or 20 μm Aβ1–42 (Fig.1C).

Fig. 1.

APP−/− and APP+/+ cortical neurons do not have differences in susceptibility to Aβ25–35 or Aβ1–42 inhibition of MTT reduction. Primary cortical neurons were grown at (A) high density (450,000 cells/cm2) or (B) low density (250,000 cells/cm2) for 3 d and exposed to Aβ25–35 for an additional 4 d. No differences between MTT reduction were observed between APP−/− and APP+/+ cortical neurons exposed to Aβ25–35 at either density. Treatment of cultures with 10 ng/ml bFGF (applied concomitantly with Aβ) resulted in a significant increase in cell viability as compared with non-bFGF-treated cultures when measured 4 d after exposure to Aβ25–35. *p < 0.05, **p < 0.01: differences in MTT reduction between bFGF and non-bFGF-treated cultures were determined using ANOVA and Newman–Keuls tests. C, APP−/− and APP+/+ cortical neurons reveal no differences in MTT reduction when treated with Aβ1–42. D, APP−/− and APP+/+ cortical neurons have no differences in susceptibility to Aβ25–35-induced cell death as determined using the LDH assay. E, APP−/− and APP+/+ cortical neurons reveal no differences in survival when exposed to Aβ1–42-induced cell death as determined using the LDH assay.F, APP−/− and APP+/+ cerebellar granule neurons reveal no differences in susceptibility to Aβ25–35 inhibition of MTT reduction. Primary cerebellar neurons were grown for 1 d and exposed to Aβ25–35 for an additional 6 d.

Because there is still doubt concerning the direct relationship between Aβ inhibition of MTT levels and Aβ-induced neuronal death (Shearman et al., 1995; Abe and Kimura, 1996; Liu and Schubert, 1997), the LDH assay was also used to determine actual cell death. Release of the stable constitutive enzyme LDH occurs after cell lysis and therefore gives an accurate estimation of the terminal response of neurons to toxic Aβ. Cortical neuronal cultures that had been treated with Aβ25–35 or Aβ1–42 for 4 d were assayed for release of LDH. A clear correlation between Aβ concentration and the level of LDH release into the culture medium was found (Fig.1D,E). The level of cytotoxicity was lower for the LDH assay compared with the MTT assay. This result was expected because of the characteristic ability of Aβ to rapidly lower the level of MTT reduction in treated cultures without a direct increase in cell death and the loss of membrane integrity required for LDH release (Shearman et al., 1995; Abe and Kimura, 1996; Liu and Schubert, 1997). The LDH assay also did not show a significant difference in Aβ-mediated cell death between APP−/− and APP+/+neurons (Fig. 1D,E). These results reveal that a lack of normal endogenous APP expression in mouse cortical neurons does not affect the ability of Aβ to lower neuronal redox activity or induce cell death.

Effect of bFGF on Aβ toxicity in APP−/− and APP+/+ cortical neurons

bFGF has been shown to reduce Aβ toxicity in primary hippocampal cultures (Mattson et al., 1993a) as well as increase APP expression in neurons in vitro (Ohyagi and Tabira, 1993). If these effects were linked, then bFGF treatment of neuronal cultures could result in differential survival of APP−/− and control APP+/+ cultures after exposure to Aβ. Treatment of high- and low-density cultures with 10 ng/ml bFGF resulted in a significant increase in cell viability after exposure to Aβ25–35 for 4 d [Fig. 1A,B, *p < 0.05, **p < 0.01 (ANOVA and Newman–Keuls test)]. Interestingly, a difference was not observed between APP−/− and APP+/+ cultures at low or high density, indicating that APP expression is not required for the protective effect of bFGF on Aβ toxicity in neurons.

Aβ25–35 toxicity in APP−/− and APP+/+ cerebellar granule neuron cultures

To determine how other neuronal cell types are affected by a lack of APP expression, we tested APP−/− and APP+/+ CGN cultures. Aβ25–35 was added to CGN cultures at day 1 in vitro (24 hr after plating) at 5 and 25 μm. Because CGN cultures do not reveal an immediate drop in MTT reduction, characteristic for Aβ-treated cortical neurons (our unpublished observations), the MTT assay was used as a measure of cell survival rather than cell redox activity alone. Cell viability was determined after exposure for 6 d instead of 4 d because of increased resistance to Aβ-induced toxicity in these cultures. As with cortical neuronal cultures, differences were not observed between APP−/− and APP+/+ CGN (Fig. 1F). bFGF treatment did not alter the level of Aβ toxicity in APP−/− and APP+/+ CGN cultures (data not shown).

Effects of peroxide-associated oxidative stress on cell survival in APP−/− and APP+/+ neuronsin vitro

Intracellular peroxide generation can be induced in immature neuronal cultures by exposure to high concentrations (millimolar) of glutamate. This leads to glutathione (GSH) depletion caused by competitive inhibition of cysteine uptake, which is necessary for reduced GSH synthesis (Ratan et al., 1994), resulting in a subsequent increase in intracellular peroxide levels. The role of GSH depletion in this form of glutamate toxicity has been confirmed in our laboratory by preventing toxicity with exogenous GSH (our unpublished observations). This type of oxidative stress is reduced in a B103 cell line transfected with human APP cDNA (Schubert and Behl, 1993), whereas secreted human APP [(hu) sAPP] applied to primary cultures of human and animal cortical neurons results in reduced peroxide generation (Mattson et al., 1993b).

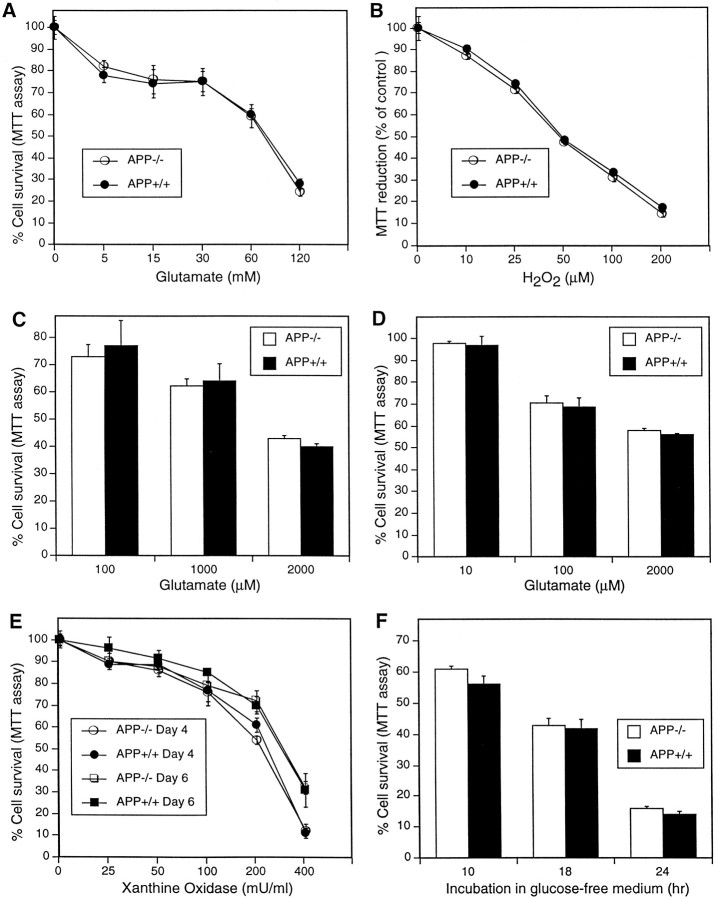

To determine whether APP−/− neurons are more susceptible to oxidative stress than wild-type neurons, high concentrations of glutamate were applied to immature cortical cultures (3 d in vitro), and cell viability was determined after 24 hr. A significant decrease in cell survival was obtained with at least 5 mm glutamate (Fig.2A). Significant differences in toxicity were not observed between APP−/− and APP+/+ cultures. Similarly, exposure to exogenous hydrogen peroxide for 24 hr did not affect cell viability of APP−/− compared with APP+/+ cultures (Fig. 2B). These results indicate that endogenous APP expression does not significantly reduce peroxide-associated oxidative stress in primary cortical neurons.

Fig. 2.

APP−/− and APP+/+ neurons do not have differences in susceptibility to intracellular- or extracellular-generated oxidative stress. A, Primary cortical neurons were grown for 2 d and exposed to glutamate for 24 hr. B, Primary cortical cultures were grown for 4 d and then exposed to H2O2 for 24 hr. C, Primary cerebellar granule neurons were grown for 7 d and then exposed to glutamate for 30 min. D, Primary cortical cultures were grown for 14 d and then exposed to glutamate for 30 min. Cell viability was determined 24 hr later. E, Primary cortical neurons were exposed to increasing concentrations of xanthine oxidase and 50 μm xanthine for 24 hr at either 4 or 6 d in vitro. F, Primary cortical neurons were grown for 14 d before incubation in glucose-free Locke’s media. Cell viability was determined after the given incubation period.

Effects of excitotoxicity-mediated oxidative stress on cell survival in APP−/− and APP+/+neurons in vitro

Previous studies have demonstrated that (hu) sAPP applied to primary cultures of human and animal neurons results in increased resistance to glutamate excitotoxicity (Mattson et al., 1993b). To determine whether APP−/− neurons have decreased resistance to excitotoxicity, micromolar concentrations of glutamate were added to APP−/− and APP+/+cultures of CGN and cortical neurons. The CGN neurons were used because of their highly homogeneous nature (96%) and well characterized response to excitotoxins (Lindholm et al., 1993). Cortical neurons were used because this cell type has previously been shown to be protected from excitotoxic glutamate by (hu) sAPP (Mattson et al., 1993b). A 30 min exposure to glutamate in 7-d-old cultures of CGN or 14-d-old cultures of cortical neurons resulted in cell death in both cultures as measured by MTT reduction 24 hr after exposure (Fig. 2, Cand D, respectively). APP−/− and APP+/+ cultures did not differ significantly at any concentration of glutamate used. The findings show that cortical neurons and CGN that do not express APP do not differ in their ability to survive excitotoxic insult.

Effects of superoxide anion-mediated oxidative stress on cell survival in APP−/− and APP+/+neurons in vitro

An important form of oxidative stress in neurons is mediated by the superoxide anion free radical (Sagara et al., 1996). To determine whether the antioxidant pathway for superoxide removal (superoxide dismutase pathway) involves APP expression, primary cortical neurons were exposed to increasing concentrations of xanthine oxidase (XO) in the presence of 50 μm xanthine, the combination of which results in the generation of superoxide anions (Brown et al., 1996b). Increasing concentrations of XO up to 400 mU/ml in the medium resulted in increasing cell death in 4- and 6-d-old cultures (Fig.2E) as measured 24 hr after addition of the enzyme. Little difference in the level of toxicity was observed between cultures at 4 and 6 d when exposed to 25–100 mU/ml XO. At concentrations of 200 and 400 mU/ml XO, greater toxicity was seen in 4-d-old compared with 6-d-old cultures. Significant differences were not observed in superoxide anion toxicity in APP−/− and APP+/+ cultures at either 4 or 6 d in vitro (Fig. 2E). These results reveal that the level of oxidative stress involving O2− is not significantly affected by expression of APP in cortical neuronal cultures.

Effects of hypoglycemia-mediated oxidative stress on cell survival in APP−/− and APP+/+ neuronsin vitro

Hypoglycemia can cause increased oxidative stress in neurons through increased generation of reactive oxygen species. Mattson et al. (1993b) have demonstrated a significant protective effect against hypoglycemic-related cell death in neurons exposed to exogenous (hu) sAPP. The role of endogenous APP expression in protection against hypoglycemia was examined by exposing 14-d-old cortical neurons from APP−/− and APP+/+ to glucose-free Locke’s solution for 10, 18, and 24 hr. This resulted in a significant and continuous reduction in cell survival over the 24 hr period; again, differences between APP−/− and APP+/+ neurons were not observed (Fig.2F). These results indicate that neurons capable of expressing endogenous APP have no survival advantage under hypoglycemic conditions.

Effect of Aβ25–35 and H2O2 on APP and APLP expression in primary cortical cultures

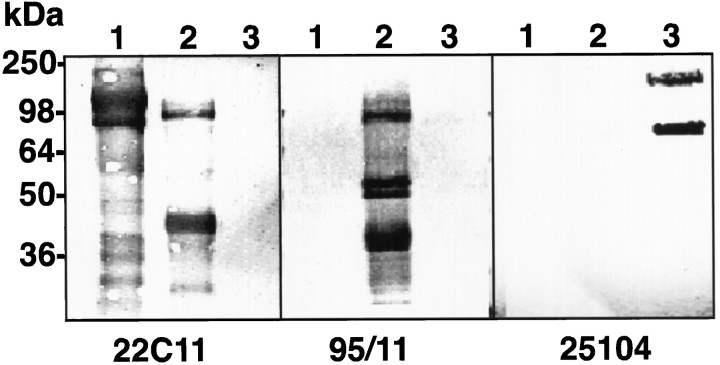

As APP is part of a multi-gene family, the similar survival properties of APP−/− and APP+/+neurons in response to Aβ or oxidative stress may be compensated for by either of the APLPs. To test this hypothesis we exposed APP−/− and APP+/+ neuronal cultures to Aβ25–35 (10 μm) or H2O2 (25 μm) for 24 hr and measured APP/APLP expression by quantitative Western blot analysis. The specificities of the APLP2 and APLP1 antibodies are shown in Figure3. The anti-APLP1 (25104) and anti-APLP2 (95/11) antibodies reacted only with their respective recombinant proteins.

Fig. 3.

Characterization of the specificity of the APLP2 and APLP1 antibodies. Western blots of recombinant sAPP751 (lane 1), sAPLP2 (lane 2), and sAPLP1 (lane 3) probed with 22C11 (anti-APP/APLP2, 1:2000), 95/11 (anti-APLP2, 1:1000), or 25104 (anti-APLP1, 1:1000). The lower bands correspond to breakdown products as described previously (Henry et al., 1997). The position of the molecular weight markers is indicated on the left.

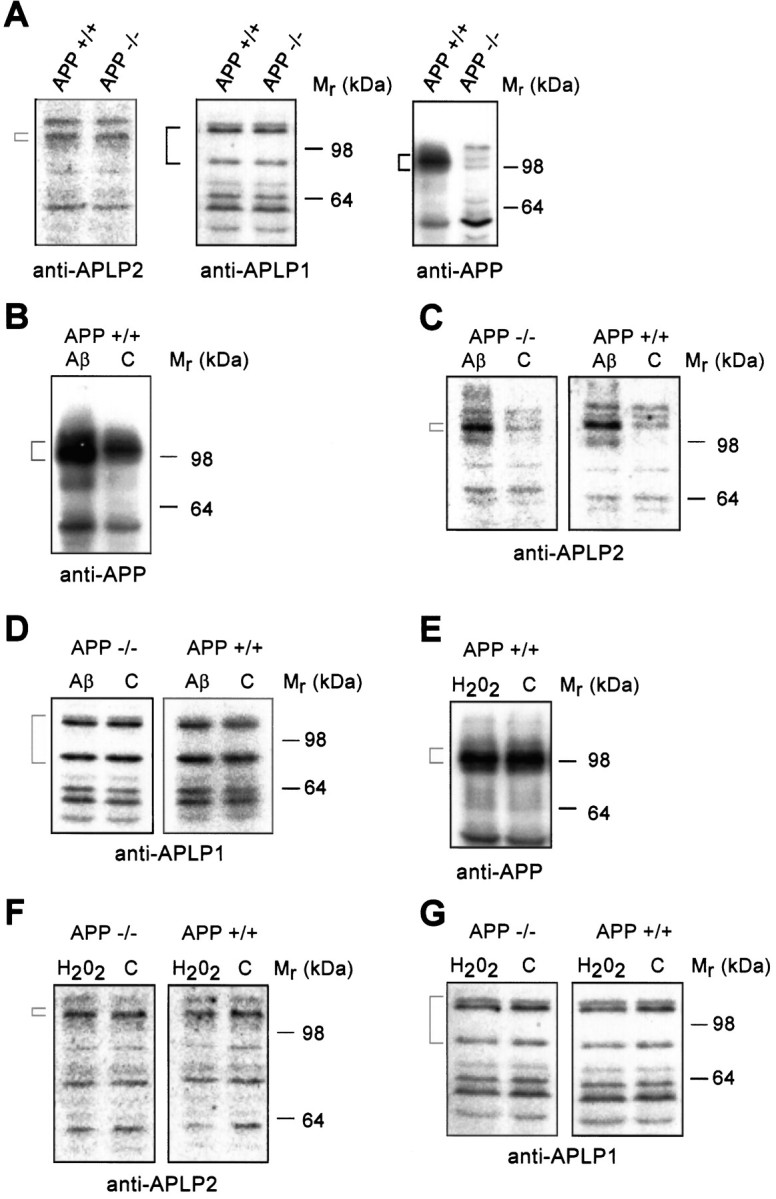

As expected, immunoblot analyses of untreated APP−/− cortical neurons did not reveal expression of APP (Fig. 4A). In addition, no increase in basal level expression of APLP1 or APLP2 was observed in APP−/− neurons when compared with APP+/+ neurons (Fig. 4A). This is consistent with previous data showing no increase in APLP2 expression in total brain homogenates (Zheng et al., 1995). After a 20 hr exposure to Aβ25–35 (10 μm), APP+/+ neurons showed a significant increase in cell-associated APP and APLP2 expression as determined by Western blotting with 22C11 and 95/11, respectively (Fig. 4B,C; Table2). Although 22C11 cross-reacts with APLP2, differences in molecular weight between APP and APLP2 and a comparison with APP−/− lysates allowed us to demonstrate specific increases in both APLP2 (110 kDa) and APP (95–105 kDa) proteins in APP+/+ cultures. Further confirmation of protein specificity was obtained using the APP-specific antibody Ab1–25 (data not shown). Blotting with 95/11 also revealed a significant increase in the 110 kDa APLP2 band in APP−/− cultures exposed to Aβ25–35 (Fig.4C, Table 2). These results indicate that primary cortical neurons respond to Aβ toxicity by upregulating expression of both APP and APLP2. Immunoblotting analysis with anti-APLP1 antibody did not reveal any significant increase in this protein in APP+/+ or APP−/− cultures exposed to Aβ25–35 (Fig. 4D, Table 2). In contrast to the effect of Aβ25–35, the treatment of APP+/+and APP−/− cortical cultures with 25 μm H2O2 for 24 hr resulted in no significant change in the expression levels of APP or APLP (Fig.4E–G). A similar result was also obtained when 3-d-old cultures were exposed to glutamate (15 mm) for 24 hr (data not shown). This indicates that the basal levels of APLP in the APP−/− cultures provide a similar level of protection to APP and APLP in APP+/+ cultures.

Fig. 4.

Quantitative immunoblotting of cell-associated APP, APLP1, and APLP2 in neurons exposed to Aβ25–35 and H2O2. Primary cortical neurons were grown for 2 d and then exposed to either 10 μmAβ25–35(Aβ) or 25 μmH2O2, or were untreated [control (C)] for 24 hr. The antibodies are anti-APP/APLP2 (22C11, 1:2000), anti-APLP2 (95/11, 1:1000), or anti-APLP1 (25104, 1:1000). The brackets correspond to the proteins described in Results and their molecular weights are as follows: anti-APP (95–105), anti-APLP1 (87 and 126), and anti-APLP2 (110 kDa). The position of the molecular weight markers is indicated on theright-hand side. A, Analysis of APLP2, APLP1, and APP expression under basal conditions. B, Analysis of APP expression detected in Aβ25–35-treated APP+/+ cultures. C, Analysis of APLP2 expression in Aβ25–35-treated APP−/− and APP+/+ neurons shows a significant increase in APLP2 expression in both APP−/− and APP+/+ neurons exposed to Aβ. D, Analysis of APLP1 expression in Aβ25–35-treated APP−/− or APP+/+ neurons.E, Analysis of APP expression in APP+/+ neurons in response to H2O2. F, Analysis of APLP2 expression in H2O2-treated APP−/− and APP+/+ neurons.G, Analysis of APLP1 expression in H2O2-treated APP−/− and APP+/+ neurons.

Table 2.

Quantitation of the immunoblot data on cell-associated APP, APLP1, and APLP2 expression after Aβ25-35 treatment as shown in Figure 4B–D

| Mr range (kDa) | Antibody | APP expression | % Increase in protein expression compared with untreated control |

|---|---|---|---|

| 95–105 | 22C11 (APP) | + | 68 ± 1.4 |

| 110 | 95/11 (APLP2) | − | 69 ± 3.4 |

| + | 81 ± 3.1 | ||

| 115–135 | 95/11 (APLP2) | − | 34 ± 4.9 |

| + | 10 ± 0.2 | ||

| 87 and 126 | 25104 (APLP1) | − | 8 ± 0.7 |

| + | 4 ± 2.1 |

The data were derived from quantitative analysis of125I-protein-A-labeled blots with a Fujix 1000 Phosphorimager and MacBas1 software. The percentage increase corresponds to the amount of protein detected in cultures treated with Aβ25-35 compared with untreated cultures.

DISCUSSION

The aim of this work was to investigate the neuroprotective role of endogenously expressed APP in the CNS. It has been shown that treatment of primary neurons with secreted forms of APP (Mattson et al., 1993b; Goodman and Mattson, 1994) or transfection of cell lines and mice with (hu)APP cDNA (Schubert and Behl, 1993;Mucke et al., 1996) results in protection against oxidative toxicity induced by the Aβ peptide, glutamate excitotoxicity, and hypoglycemia. This increased survival may reflect a heightened resistance to oxidative stress. Although these findings support a neuroprotective activity for APP, the role of endogenous neuronal APP in neuroprotection has not been assessed. We used APP knock-out primary neurons to test the role of endogenous APP because they avoid the problems associated with antisense procedures.

This study clearly demonstrates that endogenous APP expression does not alter the survival of primary cortical or cerebellar neurons in response to Aβ-mediated toxicity or oxidative stress in vitro. We found that the absence of APP expression had no effect on neuronal viability under basal conditions (Table 1), suggesting that the neurotrophic activity of APP is not essential for cortical or cerebellar neuronal growth in vitro. This differs slightly from a report on survival of hippocampal neurons cultured from APP−/− mice. Perez et al. (1997) observed a small but significant reduction in viability in APP−/−as compared with APP+/+ hippocampal neurons in primary culture. The results from our study may simply reflect differences between cell types (cortical vs hippocampal), media, cell densities, or the effect of astrocyte-conditioned media. There was no observable increase in the basal levels of APLP1 and APLP2 expression in APP−/− neurons in our study, indicating that under normal growth conditions in vitro, the absence of APP does not require the compensatory increased expression of an APLP. We evaluated the survival of APP−/− and APP+/+ neurons under neurotoxic conditions by exposing them to a range of endogenously and exogenously generated oxidative stresses. In all cases, differences in cell survival were not observed between the APP−/− and APP+/+ neurons. However, changes in APP and APLP expression were found after exposure to Aβ but not to H2O2. Aβ treatment caused increased expression of APLP2 and APP in APP+/+ neurons and APLP2 in APP−/− neurons.

Our data demonstrating a similarity between the APP−/− and APP+/+ neurons do not support a neuroprotective function for endogenous APP in vitro. It is possible that the level of endogenous APP expression and secretion in primary neuronal cultures is too low to influence the level of neuroprotection against oxidative stress. If so, the absence of APP in APP−/− neurons would not be expected to have any effect. The level of APP expression in transgenic mice is an important factor in determining the degree of neuroprotection against excitotoxic insult (Mucke et al., 1996). Although the specific level of sAPP in primary neuronal cultures has not been reported, our immunoblotting data and the study by Hung et al. (1992) show that primary neuronal cultures express readily detectable levels of APP (Fig. 4B). It is therefore unlikely that the level of APP expression is too low to induce a measurable neuroprotective effect.

The similarity between the APP−/− and APP+/+ neurons may reflect species-dependent sequence variations between human and mouse APP. The effect of these sequence differences on neuroprotection is unknown because all previous studies have used human APP. The high homology between the coding regions (97%) and the 5′ regulatory regions of human and mouse APP (De Strooper et al., 1991; Chernak, 1993) suggests a conserved function between species and is therefore also an unlikely explanation. However, it has been proposed that the Aβ1–16 sequence is important for neuroprotection, possibly through heparin binding. Interestingly, the three differences between the mouse and human Aβ sequences are all contained within Aβ1–16, including the histidine to arginine substitution at position 13 that may be required for heparin binding (Brunden et al., 1993).

We speculate that APP−/− and APP+/+ neurons do not display any differences because APLP expression is able to compensate for the absence of APP. This model would support the existing studies describing the neuroprotective activity of APP but indicates that this function could also be shared by the APLP molecules. There is considerable sequence homology and conservation of putative functional motifs and domains between APP and the APLP (Paliga et al., 1997). These similarities suggest the APLPs could share and/or compensate for the function of APP, thus reflecting a redundancy in the APP gene family. This is supported by studies in which APP, APLP1, and APLP2 single knock-out mice have been shown to survive with minor neurological dysfunction (Zheng et al., 1995; Muller et al., 1997; von Koch et al., 1997). However, APP/APLP2 double knock-outs are a lethal combination resulting in death during embryonic to early postnatal development (von Koch et al., 1997). This suggests that although early cerebral development may not be severely impaired by a loss of either APP or APLP expression, cells cannot compensate for a simultaneous loss of both. The APLP could be compensating for APP by binding to and stimulating the APP receptor. Alternatively, APLP could be acting as a receptor to bind the APP ligand and transmit the appropriate signal. However, the putative compensatory role of APLP remains to be tested.

The finding that cell-associated APP and APLP2 expression is increased after exposure to Aβ is consistent with previous reports (Cribbs et al., 1995; Saporito-Irwin et al., 1997; Schmitt et al., 1997). The increased level of cell -associated protein may be attributable, at least in part, to decreased secretion because 40% less sAPP was detected in the media of Aβ-treated cultures (data not shown). This is supported by Schmitt et al. (1997) who reported that increases in cellular APP expression induced by Aβ25–35 were caused by decreases in APP secretion. APP and APLP2 have similar expression and secretory pathways (Nitsch et al., 1992; Webster et al., 1995). Interestingly, no change was seen in sAPLP2 levels after Aβ treatment (data not shown). This would indicate that Aβ can also induce increased expression of APLP2, and possibly APP, and that Aβ may have differential effects on some aspects of APP and APLP2 expression and processing. No change in APLP1 expression was detected after exposure to Aβ, and this may reflect the lower homology of APLP1 with APP and APLP2. This data would indicate that APLP2 expression, rather than APLP1, may be responsible for compensatory activity in APP−/− cells. To clarify this issue, the neuroprotective activity of APLP2 and APLP1 needs to be determined. In addition, the susceptibility of neurons from APLP1 and APLP2 single knock-outs and APP/APLP1, APP/APLP2, and APLP1/APLP2 double knock-outs to oxidative stress also needs to be investigated.

Our finding that APP and APLP expression levels remain unaltered in H2O2 and glutamate-treated cultures is important because it suggests that Aβ-induced toxicity is distinct from general oxidative stress and that Aβ increases APP/APLP2 expression through a nonoxidative stress-related pathway. This could be because Aβ operates via an Aβ-receptor (Yan et al., 1996, 1997), which results in either localized oxidative stress or activation of a specific cell-signaling pathway or both. In contrast, H2O2 and glutamate produce pan-cellular oxidative stress, which does not increase APP/APLP expression. It is unlikely that the level of H2O2 or glutamate exposure was too low to induce APP/APLP expression because the level of toxicity obtained was similar to that induced by Aβ.

It has been suggested that toxic, amyloidogenic peptides may share a common toxic mechanism (Ridley and Baker, 1993). Our data would suggest that the mechanism of Aβ-toxicity is distinct from the amyloidogenic prion protein-derived peptide PrP106–126 (Brown et al., 1996a). The PrP106–126 peptide requires expression of normal cellular prion protein (the parent molecule) to induce toxicity in neurons in vitro (Brown et al., 1996a). In contrast, our results show that Aβ does not require the presence of the normal parent molecule (APP) to induce neuronal toxicity (other than as a source of Aβ in vivo). This suggests that although Aβ may induce a positive feedback effect on APP processing leading to increased Aβ formation and aberrant APP metabolism (Cribbs et al., 1995), these factors do not contribute to the short-term neuronal loss seen in vitro. The effect of increased APP expression may result, however, in changes to neuronal survival in the longer term. An alternative, and exciting, explanation is that if the APLP molecules represent functional homologs of APP then the Aβ peptide could act through an APLP, and in particular APLP2. This would suggest that APP/APLP double knock-out neurons would be refractory to Aβ toxicity and hence mimic the prion-PrPc model.

If APP is involved in neuroprotection against Aβ and oxidative stressin vivo, then any perturbations to APP metabolism such as those occurring in AD may not only result in increased Aβ deposition but may also reduce neuroprotection (Mattson et al., 1993b). If the APLP molecules, in particular APLP2, have a neuroprotective function reflecting that seen with sAPP, then changes to APLP protein metabolism may also result in decreased neuronal resistance to oxidative insults or Aβ. A neuroprotective role for APLP may have important implications for Alzheimer’s disease because therapeutic treatments specifically aimed at increasing APLP expression may provide a means of increasing neuroprotection without directly contributing to Aβ deposition. This may have the added benefit of replacing some of the functions that are lost because of aberrant APP metabolism, such as dendritic growth.

Footnotes

This work was supported in part by grants from the National Health and Medical Research Council of Australia to C.L.M. K.B. is supported by the Deutshe Forschungsgemeinschaft and the Bundesministerium fur Forschung und Technologie.

Correspondence should be addressed to Dr. Roberto Cappai, Department of Pathology, The University of Melbourne, Parkville Victoria 3052, Australia.

REFERENCES

- 1.Abe K, Kimura H. Amyloid β toxicity consists of a Ca2+-independent early phase and a Ca2+-dependent late phase. J Neurochem. 1996;67:2074–2078. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Barger SW, Fiscus RR, Ruth P, Hofmann F, Mattson MP. Role of cyclic GMP in the regulation of neuronal calcium and survival by secreted forms of β-amyloid precursor. J Neurochem. 1995;64:2087–2096. doi: 10.1046/j.1471-4159.1995.64052087.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Brown DR, Schmidt B, Kretzschmar HA. A neurotoxic prion protein fragment enhances proliferation of microglia but not astrocytes in culture. Glia. 1996a;18:59–67. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1098-1136(199609)18:1<59::AID-GLIA6>3.0.CO;2-Z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Brown DR, Schmidt B, Kretzschmar HA. Role of microglia and host prion protein in neurotoxicity of a prion protein fragment. Nature. 1996b;380:345–347. doi: 10.1038/380345a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Brunden KR, Richter-Cook NJ, Chaturvedi N, Frederickson RCA. pH-dependent binding of synthetic β-amyloid peptides to glycosaminoglycans. J Neurochem. 1993;61:2147–2154. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-4159.1993.tb07453.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Chernak JM. Structural features of the 5′ upstream regulatory region of the gene encoding rat amyloid precursor protein. Gene. 1993;133:255–260. doi: 10.1016/0378-1119(93)90648-m. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Cribbs DH, Davis-Salinas J, Cotman CW, Van Nostrand WE. Aβ induces increased expression and processing of amyloid precursor protein in cortical neurons. Alzheimer’s Res. 1995;1:197–200. [Google Scholar]

- 8.De Strooper B, Van Leuven F, Van Den Berghe H. The amyloid β protein precursor or proteinase nexin II from mouse is closer related to its human homolog than previously reported. Biochim Biophys Acta. 1991;1129:141–143. doi: 10.1016/0167-4781(91)90231-a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Glenner GG, Wong CW. Alzheimer’s disease and Down’s syndrome: sharing of a unique cerebrovascular amyloid fibril protein. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 1984;122:1131–1135. doi: 10.1016/0006-291x(84)91209-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Goodman Y, Mattson MP. Secreted forms of β-amyloid precursor protein protect hippocampal neurons against amyloid β-peptide-induced oxidative injury. Exp Neurol. 1994;128:1–12. doi: 10.1006/exnr.1994.1107. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Henry A, Masters CL, Beyreuther K, Cappai R. Expression of the ectodomains of the human amyloid precursor protein in Pichia pastoris: analysis of culture conditions, purification, and characterization. Protein Expr Purif. 1997;10:283–291. doi: 10.1006/prep.1997.0748. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Hung AY, Koo EH, Haass C, Selkoe DJ. Increased expression of β-amyloid precursor protein during neuronal differentiation is not accompanied by secretory cleavage. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1992;89:9439–9443. doi: 10.1073/pnas.89.20.9439. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Kang J, Lemaire H, Unterbeck A, Salbaum JM, Masters CL, Grzeschik K, Multhaup G, Beyreuther K, Müller-Hill B. The precursor of Alzheimer’s disease amyloid A4 protein resembles a cell-surface receptor. Nature. 1987;325:733–736. doi: 10.1038/325733a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Koh J, Yang LL, Cotman CW. β-Amyloid protein increases the vulnerability of cultured cortical neurons to excitotoxic damage. Brain Res. 1990;533:315–320. doi: 10.1016/0006-8993(90)91355-k. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Koo EH, Sisodia SS, Archer DR, Martin LJ, Weidemann A, Beyreuther K, Fischer P, Masters CL, Price DL. Precursor of amyloid protein in Alzheimer disease undergoes fast anterograde axonal transport. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1990;87:1561–1565. doi: 10.1073/pnas.87.4.1561. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Lindholm D, Dechant G, Heisenberg C, Thoenen H. Brain-derived neurotrophic factor is a survival factor for cultured rat cerebellar granule neurons and protects them against glutamate-induced neurotoxicity. Eur J Neurosci. 1993;5:1455–1464. doi: 10.1111/j.1460-9568.1993.tb00213.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Liu Y, Schubert D. Cytotoxic amyloid peptides inhibit cellular 3-(4,5-dimethylthiazol-2-yl)-2,5-diphenyltetrazolium bromide (MTT) reduction by enhancing MTT formazan exocytosis. J Neurochem. 1997;69:2285–2293. doi: 10.1046/j.1471-4159.1997.69062285.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Lockhart BP, Benicourt C, Junien JL, Privat A. Inhibitors of free radical formation fail to attenuate direct β-amyloid25–35 peptide-mediated neurotoxicity in rat hippocampal cultures. J Neurosci Res. 1994;39:494–505. doi: 10.1002/jnr.490390416. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Masters CL, Simms G, Weinman NA, Multhaup G, McDonald BL, Beyreuther K. Amyloid plaque core protein in Alzheimer disease and Down syndrome. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1985;82:4245–4249. doi: 10.1073/pnas.82.12.4245. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Mattson MP. Cellular actions of beta-amyloid precursor protein and its soluble and fibrillogenic derivatives. Physiol Rev. 1997;77:1081–1132. doi: 10.1152/physrev.1997.77.4.1081. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Mattson MP, Barger SW, Cheng B, Lieberburg I, Smith-Swintosky VL, Rydel RE. β-Amyloid precursor protein metabolites and loss of neuronal Ca2+ homeostasis in Alzheimer’s disease. Trends Neurosci. 1993a;16:409–414. doi: 10.1016/0166-2236(93)90009-b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Mattson MP, Cheng B, Culwell AR, Esch FS, Lieberburg I, Rydel RE. Evidence for excitoprotective and intraneuronal calcium-regulating roles for secreted forms of the β-amyloid precursor protein. Neuron. 1993b;10:243–254. doi: 10.1016/0896-6273(93)90315-i. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Milward E, Papadopoulos R, Fuller SJ, Moir RD, Small D, Beyreuther K, Masters CL. The amyloid protein precursor of Alzheimer’s disease is a mediator of the effects of nerve growth factor on neurite outgrowth. Neuron. 1992;9:129–137. doi: 10.1016/0896-6273(92)90228-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Mucke L, Abraham CR, Masliah E. Neurotrophic and neuroprotective effects of hAPP in transgenic mice. Ann NY Acad Sci. 1996;777:82–88. doi: 10.1111/j.1749-6632.1996.tb34405.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Muller U, Gajic V, Hainsellner J, Aguzzi A, Herms J, Tremml P, Wolfer D, Lipp HP. Transgenic models to define the physiological role of proteins of the APP-family. Soc Neurosci Abstr. 1997;23:1874. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Nakamura Y, Takeda M, Niigawa H, Hariguchi S, Nishimura T. Amyloid β-protein precursor deposition in rat hippocampus lesioned by ibotenic acid injection. Neurosci Lett. 1992;136:95–98. doi: 10.1016/0304-3940(92)90656-r. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Nitsch RM, Slack BE, Wurtman RJ, Growdon JH. Release of Alzheimer amyloid precursor derivatives stimulated by activation of muscarinic acetylcholine receptors. Science. 1992;258:304–307. doi: 10.1126/science.1411529. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Ohyagi Y, Tabira T. Effect of growth factors and cytokines on expression of amyloid β protein precursor mRNAs in cultured neural cells. Mol Brain Res. 1993;18:127–132. doi: 10.1016/0169-328x(93)90181-n. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Paliga K, Peraus G, Kreger S, Dürrwang U, Hesse L, Multhaup G, Masters CL, Beyreuther K, Weidemann A. Human amyloid precursor-like protein 1 cDNA cloning, ectopic expression in COS-7 cells and identification of soluble forms in the cerebrospinal fluid. Eur J Biochem. 1997;250:354–363. doi: 10.1111/j.1432-1033.1997.0354a.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Perez RG, Zheng H, Van der Ploeg LHT, Koo EH. The β-amyloid precursor protein of Alzheimer’s disease enhances neuron viability and modulates neuronal polarity. J Neurosci. 1997;17:9407–9414. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.17-24-09407.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Pike CJ, Burdick D, Walenciwicz AJ, Glabe CG, Cotman CW. Neurodegeneration induced by β-amyloid peptides in vitro: the role of peptide assembly state. J Neurosci. 1993;13:1676–1687. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.13-04-01676.1993. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Ratan RR, Murphy TH, Baraban JM. Oxidative stress induces apoptosis in embryonic cortical neurons. J Neurochem. 1994;62:376–379. doi: 10.1046/j.1471-4159.1994.62010376.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Ridley RM, Baker HF. Prion protein: a different concept of replication. Trends Neurosci. 1993;16:425–426. doi: 10.1016/0166-2236(93)90066-u. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Roher AE, Ball MJ, Bhave SV, Wakade AR. β-amyloid from Alzheimer disease brains inhibits sprouting and survival of sympathetic neurons. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 1991;174:572–579. doi: 10.1016/0006-291x(91)91455-l. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Sagara Y, Dargusch R, Klier FG, Schubert D, Behl C. Increased antioxidant enzyme activity in amyloid β protein-resistant cells. J Neurosci. 1996;16:497–505. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.16-02-00497.1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Salvietti N, Cattaneo E, Govoni S, Racchi M. Changes in β-amyloid precursor protein secretion associated with the proliferative status of CNS derived progenitor cells. Neurosci Lett. 1996;212:199–203. doi: 10.1016/0304-3940(96)12800-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Sandbrink R, Masters CL, Beyreuther K. βA4-amyloid protein precursor mRNA isoforms without exon 15 are ubiquitously expressed in rat tissues including brain, but not in neurons. J Biol Chem. 1994;269:1510–1517. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Saporito-Irwin SM, Thinakaran G, Ruffini L, Sisodia SS, Van Nostrand WE. Amyloid β-protein stimulates parallel increases in cellular levels of its precursor and amyloid precursor-like protein 2 (APLP2) in human cerebrovascular smooth muscle cells. Int J Exp Clin Invest. 1997;4:54–60. [Google Scholar]

- 39.Schmitt TL, Steiner E, Trieb K, Grubeck-Loebenstein B. Amyloid beta-protein (25–35) increases cellular APP and inhibits the secretion of APPs in human extraneuronal cells. Exp Cell Res. 1997;234:336–340. doi: 10.1006/excr.1997.3606. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Schubert D, Behl C. The expression of amyloid beta protein precursor protects nerve cells from beta-amyloid and glutamate toxicity and alters their interaction with the extracellular matrix. Brain Res. 1993;629:275–282. doi: 10.1016/0006-8993(93)91331-l. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Schubert D, Jin LW, Saitoh T, Cole G. The regulation of amyloid β protein precursor secretion and its modulatory role in cell adhesion. Neuron. 1989;3:689–694. doi: 10.1016/0896-6273(89)90237-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Shearman MS, Hawtin SR, Tailor VJ. The intracellular component of cellular 3-(4,5-dimethylthiazol-2-yl)-2,5-diphenyltetrazolium bromide (MTT) reduction is specifically inhibited by β-amyloid peptides. J Neurochem. 1995;65:218–227. doi: 10.1046/j.1471-4159.1995.65010218.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Slunt HH, Thinakaran G, Von Koch C, Lo ACY, Tanzi RE, Sisodia SS. Expression of a ubiquitous, cross-reactive homologue of the mouse β-amyloid precursor protein (APP). J Biol Chem. 1994;269:2637–2644. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Sprecher CA, Grant FJ, Grimm G, O’Hara PJ, Norris F, Norris K, Foster DC. Molecular cloning of the cDNA for a human amyloid precursor protein homolog: evidence for a multigene family. Biochemistry. 1993;32:4481–4486. doi: 10.1021/bi00068a002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Tanzi RE, McClatchey AI, Lamperti ED, Villa-Komaroff L, Gusella JF, Neve RL. Protease inhibitor domain encoded by an amyloid protein precursor mRNA associated with Alzheimer’s disease. Nature. 1988;331:528–530. doi: 10.1038/331528a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.von Koch CS, Zheng H, Chen H, Trumbauer M, Thinakaran G, van der Ploeg LHT, Price DL, Sisodia SS. Generation of APLP2 KO mice and early postnatal lethality in APLP2/APP double KO mice. Neurobiol Aging. 1997;18:661–669. doi: 10.1016/s0197-4580(97)00151-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Wasco W, Bupp K, Magendantz M, Gusella JF, Tanzi RE, Solomon F. Identification of a mouse brain cDNA that encodes a protein related to the Alzheimer disease-associated amyloid β protein precursor. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1992;89:10758–10762. doi: 10.1073/pnas.89.22.10758. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Wasco W, Gurubhagavatula S, Paradis MD, Romano DM, Sisodia SS, Hyman BT, Neve RL, Tanzi RE. Isolation and characterization of APLP2 encoding a homologue of the Alzheimer’s associated amyloid β protein precursor. Nat Genet. 1993;5:95–100. doi: 10.1038/ng0993-95. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Webster MT, Groome N, Francis PT, Pearce BR, Sherriff FE, Thinakaran G, Felsenstein KM, Wasco W, Tanzi RE, Bowen DM. A novel protein, amyloid precursor-like protein 2, is present in human brain, cerebrospinal fluid and conditioned media. Biochem J. 1995;310:95–99. doi: 10.1042/bj3100095. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Yan SD, Chen X, Fu J, Chen M, Zhu HJ, Roher A, Slattery T, Zhao L, Nagashima M, Morser J, Migheli A, Nawroth P, Stern D, Schmidt AM. RAGE and amyloid-β peptide neurotoxicity in Alzheimer’s disease. Nature. 1996;382:685–691. doi: 10.1038/382685a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Yan SD, Fu J, Soto C, Chen X, Zhu HJ, Almohanna F, Collison K, Zhu AP, Stern E, Saido T, Tohyama M, Ogawa S, Roher A, Stern D. An intracellular protein that binds amyloid-beta peptide and mediates neurotoxicity in Alzheimer’s disease. Nature. 1997;389:689–695. doi: 10.1038/39522. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Yankner BA, Dawes LR, Fisher S, Villa-Komaroff L, Oster-Granite ML, Neve RL. Neurotoxicity of a fragment of the amyloid precursor associated with Alzheimer’s disease. Science. 1989;245:417–420. doi: 10.1126/science.2474201. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Yankner BA, Duffy LK, Kirschner DA. Neurotrophic and neurotoxic effects of amyloid β protein: reversal by tachykinin neuropeptides. Science. 1990;250:279–282. doi: 10.1126/science.2218531. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Zhang F, Eckman C, Younkin S, Hsiao KK, Iadecola C. Increased susceptibility to ischemic brain damage in transgenic mice overexpressing the amyloid precursor protein. J Neurosci. 1997;17:7655–7661. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.17-20-07655.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Zheng H, Jiang MH, Trumbauer ME, Sirinathsinghji DJS, Hopkins R, Smith DW, Heavens RP, Dawson GR, Boyce S, Conner MW, Stevens KA, Slunt HH, Sisodia SS, Chen HY, Van der Ploeg LHT. β-amyloid precursor protein-deficient mice show reactive gliosis and decreased locomotor activity. Cell. 1995;81:525–531. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(95)90073-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]