Abstract

During development, growth cones navigate to their targets via numerous interactions with molecular guidance cues, yet the mechanisms of how growth cones translate guidance information into navigational decisions are poorly understood. We have examined the role of intracellular Ca2+ in laminin (LN)-mediated growth cone navigation in vitro, using chick dorsal root ganglion neurons. Subsequent to contacting LN-coated beads with filopodia, growth cones displayed a series of stereotypic changes in behavior, including turning toward LN-coated beads and a phase of increased rates of outgrowth after a pause at LN-coated beads. A pharmacological approach indicated that LN-mediated growth cone turning required an influx of extracellular Ca2+, likely in filopodia with LN contact, and activation of calmodulin (CaM). Surprisingly, fluorescent Ca2+ imaging revealed no LN-induced rise in intracellular Ca2+ in filopodia attached to their parent growth cone. However, isolation of filopodia by laser-assisted transection unmasked a rapid, LN-specific rise in intracellular Ca2+ (+73 ± 11 nm). Additionally, a second, sustained rise in intracellular Ca2+ (+62 ± 8 nm) occurred in growth cones, with a distinct delay 28 ± 3 min after growth cone filopodia contacted LN-coated beads. This delayed, sustained Ca2+ signal paralleled the phase of increased rates of outgrowth, and both events were sensitive to the inhibition of Ca2+/CaM-dependent protein kinase II (CaM-kinase II) with 2 μm KN-62. We propose that LN-mediated growth cone guidance can be attributed, in part, to two temporally and functionally distinct Ca2+ signals linked by a signaling cascade composed of CaM and CaM-kinase II.

Keywords: Ca2+, laminin, growth cone, filopodia, pathfinding, calmodulin, Ca2+/calmodulin-dependent protein kinase II

The precise pattern of neuronal connections formed during development depends on the guided advance of growth cones along specific pathways to their appropriate targets. Numerous transient interactions between growth cones and molecular guidance cues in the environment characterize this period of growth cone pathfinding (Hynes and Lander, 1992; Goodman and Shatz, 1993). The underlying mechanisms of how growth cones receive, interpret, and translate guidance information into navigational decisions are poorly understood. Recent evidence indicates that receptor-activated signal transduction mechanisms regulate advance, navigation, and target recognition of growth cones (Doherty and Walsh, 1994; Kuhn et al., 1995; Tanaka and Sabry, 1995).

The second messenger Ca2+ is a potent and versatile regulator of growth cone behavior and morphology (Kater and Mills, 1991) (for review, see Clapham, 1995; Ghosh and Greenberg, 1995). Growth cones respond to a local source of acetylcholine with a rise in the free intracellular Ca2+ concentration ([Ca2+]i) and navigate toward increasing neurotransmitter concentrations (Zheng et al., 1994).Davenport et al. (1993, 1996) have demonstrated that surgically isolated filopodia do react to neurotransmitter application with a rise of [Ca2+]i. The exchange of Ca2+ ions through gap junctions occurs during interactions of pioneer growth cones with guidepost cells (Bentley et al., 1991). L1, NCAM, and N-cadherin promote neurite outgrowth by stimulating a Ca2+ influx through voltage-gated L- and N-type calcium channels (Doherty et al., 1991;Williams et al., 1992). Also, the extracellular matrix protein LN induces small but significant rises of [Ca2+]i in ciliary ganglion neurons when applied in soluble form to the culture medium (Bixby et al., 1994). Several types of Ca2+ channels, homogeneously distributed or clustered, have been identified on neuronal growth cones (Bolsover and Spector, 1986; Silver et al., 1990) (for review, seeGottmann and Lux, 1995). Furthermore, modification of Ca2+-activated proteins disrupted growth cone behavior, providing additional evidence for a role of Ca2+ in regulating growth cone behavior. Expression of inactive calmodulin (CaM) in Drosophila resulted in severe pathfinding errors of pioneer growth cones (VanBerkum and Goodman, 1995). Also, overexpression of CaM-kinase II caused a prolonged, increased neurite outgrowth (Goshima et al., 1993), whereas CaM-kinase II inhibition decreased neurite outgrowth (Solem et al., 1995; Williams et al., 1995).

In the present study we investigated the role of intracellular Ca2+, CaM, and CaM-kinase II in LN-mediated growth cone guidance in vitro, using a pharmacological approach combined with fluorescent Ca2+ imaging. LN-coated beads, polystyrene beads covalently coupled with LN, represented a spatially restricted guidance stimulus. Growth cones contacting these LN-coated beads displayed a series of stereotypic growth cone responses reflected by changes in behavior and morphology (Kuhn et al., 1995). Two temporally and functionally distinct rises in [Ca2+]i, linked by a sequential activation of CaM and CaM-kinase II, constituted a mechanism underlying growth cone guidance provided by a singular LN stimulus. Additionally, individual growth cone responses could be attributed to individual second messenger activities.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Materials. LN, fibronectin (FN), and 2.5s NGF were obtained from Collaborative Biomedical Research (Bedford, MA). MEM and HBSS were from Life Technologies (Gaithersburg, MD). FBS was purchased from HyClone (Logan, UT). Carboxylated polystyrene beads, together with coupling reagents, were obtained from Polyscience (Warrington, PA). Fura-2AM and AM-BAPTA were from Molecular Probes (Eugene, OR). Bisindolylmaleimide, KN-62, and fluphenazine-N-2-chloroethane (FPC) were obtained from Calbiochem (San Diego, CA). All other chemicals were from Sigma (St. Louis, MO).

Cell culture. Dorsal root ganglia (DRG) from 10-d-old white Leghorn chick embryos were dissociated mechanically and enzymatically (0.1% trypsin/HBSS for 10 min at 37°C) and preplated (7.5% CO2 for 2 hr at 37°C) in MEM, 26.2 mmNaHCO3, 2 mm glutamine, and 10% FBS. Nonadherent cells were resuspended in MEM, 26.2 mmNaHCO3, 2 mm glutamine, 10% FBS, 20 ng/ml 2.5s NGF, and 1% N3 supplement, pH 7.3 (325 ± 5 mOsm) and plated on 2 μg/cm2 FN (25,000 cells/ml). FN was adsorbed (2 hr at 37°C) to dry poly-l-lysine-coated (80 μg/cm2) glass coverslips inserted into 35 mm Falcon culture dishes, washed three times with HBSS, and used immediately.

Inhibitors. The half-maximal inhibitory concentration (IC50) of every inhibitor was determined from the dose dependence of neurite outgrowth of DRG neurons on FN by adding inhibitors (concentrations used: 0.5× IC50, 1× IC50, and 2× IC50) to dissociated DRG neurons after the onset of neurite outgrowth. Cultures were preincubated for 20 min with the particular inhibitor, and the growth rates were determined. None of the inhibitors (IC50or lower concentrations) affected growth cone advance on FN over a time period of 60 min. In the standard assay, inhibitors were added 15 min before LN-coated beads were positioned (concentration used equals IC50).

Standard LN-coated bead assay. LN was coupled covalently to polystyrene beads, exposing carboxyl groups on their surface as previously described (Kuhn et al., 1995). Briefly, polystyrene beads (4.5 μm in diameter) were activated with 1% carbodiimide, pH 7, for 4 hr at RT and then washed three times with borate buffer. LN (50 μg) was coupled to 108 beads/ml (volume, 1 ml), and the remaining active groups were blocked with ethanolamine and BSA. Estimated coupling yields were routinely >65% with SDS-PAGE silver staining.

LN-coated beads were presented to advancing DRG growth cones as previously described (Kuhn et al., 1995). Culture medium was exchanged to a serum-free defined medium (MEM, 10 mm HEPES, 1% N3 supplement, 20 ng/ml 2.5s NGF, 5 mg/ml ovalbumin, and 2 mmglutamine, pH 7.3; 325 ± 5 mOsm), LN-coated beads were added, and mineral oil was overlaid to prevent evaporation (assay temperature, 37°C). LN-coated beads were manipulated in space with a LaserTweezer optical system LT-1000, using a 100 mW diode laser with an emission wavelength of 830 nm (Cell Robotics, Albuquerque, NM). A Nikon inverted microscope was equipped with a CCD camera (Hitachi Denshi, model KP-MF1V) and a computer-controlled microscopic stage (MLC-3, Märzhäuser Wetzlar GMBH). Images were acquired at 100× (Zeiss oil objective) with a MAC CI II and analyzed with the program Image 1.49 (National Institutes of Health, Bethesda, MD). In the pharmacological approach, inhibitors were added 15 min before the addition of LN-coated beads.

Measurement of intracellular calcium. DRG neurons were loaded with 2 μm fura-2AM (Molecular Probes) in MEM, 10% FBS, 20 ng/ml 2.5s NGF, 1% N3 supplement, 26.2 mmNaHCO3, and 2 mm glutamine for 30 min at 37°C. After three washes, DRG neurons were allowed to deesterify for 30 min in the same medium (identical procedure for AM-BAPTA). Then the cultures were transferred to a serum-free defined medium containing MEM without phenol red to reduce background fluorescence. Ca2+ imaging was performed with a 40× oil objective (Nikon, Fluor 1.30) and a cooled CCD camera (Photometrics, Tucson, AZ) linked to an image-processing system. Images were acquired at two excitation wavelengths (350 and 380 nm), and fluorescent emission was filtered with a 495 nm long-pass filter. The ratio of each pair of the 350 and 380 nm images was determined on a pixel-by-pixel basis, and [Ca2+]i was estimated according toGrynkiewicz et al. (1985). The system-specific values wereRmin = 0.27, Rmax = 6.90, and Fo/Fs ·KD = 739. This Ca2+ imaging system was not equipped with laser tweezers. As our criterion, a change in [Ca2+]i was considered positive when it was >2 SD above average resting [Ca2+]i. The significance of our results remained unchanged when 1 SD above average resting [Ca2+]i was applied as a less-stringent criterion.

Surgical isolation of individual filopodia. Cultures of DRG neurons were loaded with 5 μm fura-2AM for 35 min at 37°C to ensure the strong loading of filopodia. While deesterifying, individual filopodia were transected from parent growth cones via a Laser scissors system (360 nm cutting wavelength; Cell Robotics). To measure [Ca2+]i, we transferred cultures to the Ca2+ imaging system and relocated growth cones with surgically isolated filopodia.

RESULTS

LN-mediated growth cone turning requires an influx of extracellular Ca2+

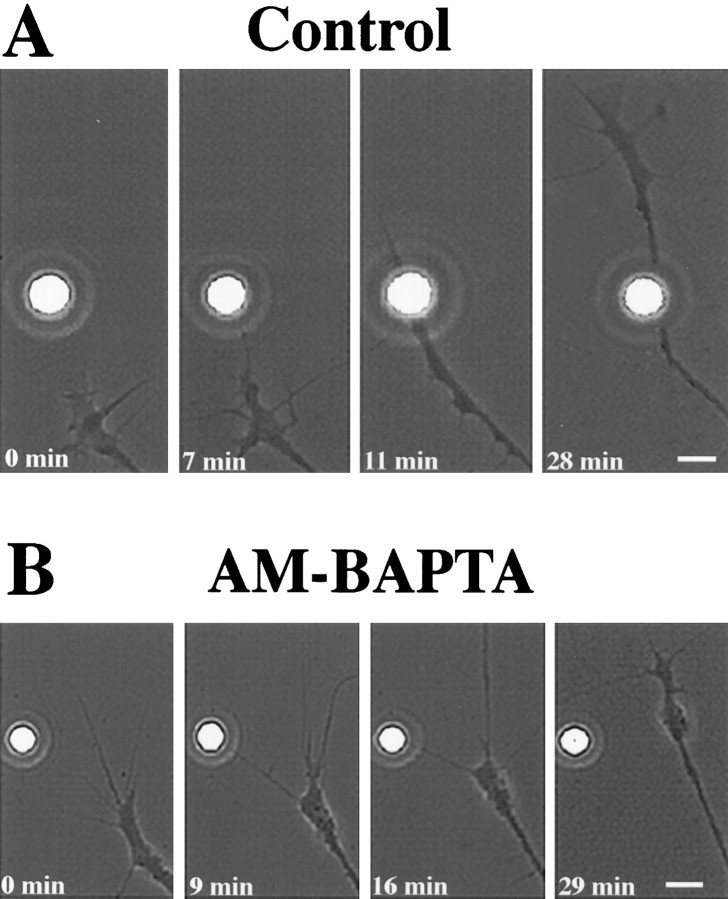

In the standard assay, chick DRG growth cones advanced on a uniform FN substrate and encountered LN-coated beads manipulated in space by optical trapping with laser tweezers. In control conditions, growth cones displayed a series of stereotypic responses characterized by changes in their behavior and morphology when they encountered LN-coated beads (Fig.1A). Typically, growth cones sampled LN-coated beads by repetitive touching with individual filopodia before the formation of long-lasting adhesive contacts with single filopodia. As a result, growth cones changed their original course of advance (turning) and approached LN-coated beads. After an extended pause at beads (14 ± 3 min; n = 12), growth cones advanced beyond LN-coated beads with twofold increased rates of outgrowth for considerable distances until the restoration of growth rates as before contact (Kuhn et al., 1995). Positive growth cone turning was defined as a deviation from the original course of advance >15°. According to this criterion 79 ± 1% (n = 21) of growth cones investigated responded positively (Fig. 2).

Fig. 1.

LN-mediated growth cone guidance is characterized by a series of stereotypic changes in growth cone behavior and requires a rise of [Ca2+]i. A, A chick DRG growth cone, advancing on FN, approaches an LN-coated bead (t = 0 min). The growth cones touches the LN-coated bead with a single filopodium and establishes a long-lasting filopodial contact (t = 7 min). The growth cone changes its original course of advance (turning), approaches the LN-coated bead, and pauses in close proximity (t = 11 min). Then the growth cone continues to advance beyond the LN-coated bead (t = 28 min) with increased rates of outgrowth for considerable distances. B, Chelating an elevation of [Ca2+]i with AM-BAPTA blocks LN-mediated growth cone turning. A growth cone, loaded previously with AM-BAPTA, approaches an LNcoated bead (t = 0 min). Although long-lasting filopodial contact is established (t = 9 min), the growth cone is unable to translate guidance instructions provided by the LN-coated bead into a navigational decision (t = 16 min) and simply passes by (t = 29 min). Scale bar, 4.5 μm. Bead diameter, 4.5 μm.

Fig. 2.

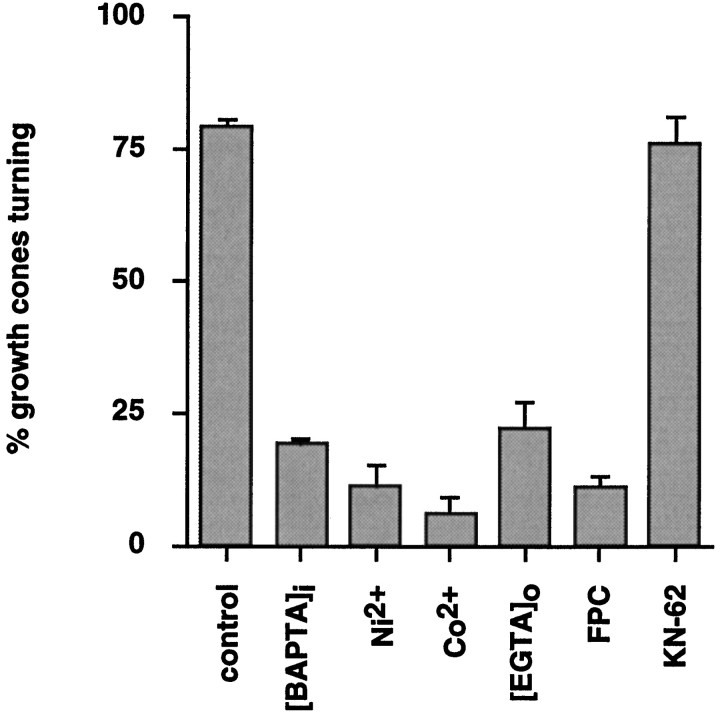

Growth cone turning toward LN-coated beads requires an influx of extracellular Ca2+ and CaM activity. A deviation of the original course of advance >15° defined a positive growth cone turning response. Under control conditions, >75% of growth cones that were investigated respond positively. Blocking Ca2+ channels (2 mm each,Ni2+ andCo2+) or chelating extracellular Ca2+([EGTA]o) or intracellular Ca2+([AM-BAPTA]i) significantly reduces the number of growth cone turnings. Inhibition of CaM with 10 μm fluphenazine-2-N-chloroethane (FPC) blocks growth cone turning, whereas inhibition of CaM-kinase II (2 μmKN-62) is ineffective. None of the inhibitors tested altered growth cone advance on the FN substrate for the time period of observation. The significance of the effects of each inhibitor was compared with a parallel control (t test). Control value shown is an average of all controls. Error bars indicate SEM.

In contrast, growth cones ignored LN-coated beads when preloaded with AM-BAPTA (2 μm; KD = 340 nm) to chelate elevations in [Ca2+]i. Growth cones maintained their original course of advance despite sampling of LN-coated beads with individual filopodia and long-lasting filopodial adhesion (Fig.1B). Under these conditions only 19 ± 1% (n = 21; p < 0.01) of growth cones that were investigated responded positively (Fig. 2). Also, nominal zero extracellular Ca2+ (2 mm EGTA in a Ca2+-free medium) reduced the number of positively responding growth cones (22 ± 5%, n = 13;p < 0.001). Similarly, general Ca2+channel blockers such as 2 mm Ni2+(11 ± 4% growth cones responding positively, n = 17; p < 0.001) or 2 mmCo2+ (6 ± 3% growth cones responding positively, n = 15; p < 0.05) abolished growth cone turning. These inhibitors disrupted the series of stereotypic growth cone responses as detailed for AM-BAPTA conditions. Importantly, none of the inhibitors altered growth cone migration on FN at concentrations used in the standard assay (observation time, 60 min) (Table 1). This finding implied that inhibitors specifically blocked LN-signaled growth cone turning and not indirectly by lowering resting levels of [Ca2+]i in growth cones. However, 4 mm Ni2+ or Co2+caused growth cone collapse and neurite retraction. Growth cone detachment and significant changes in growth cone morphology were observed in 5 mm EGTA and with 4 μm BAPTA, respectively. These effects were observed later than 30 min after the addition of inhibitors at high concentration. In conclusion, this pharmacological study suggests that an LN-stimulated influx of extracellular Ca2+ is required for subsequent growth cone turning. It is conceivable that this Ca2+influx occurs in filopodia at the contact site with LN-coated beads.

Table 1.

Dose-dependent effects of inhibitors on growth cone migration on fibronectin

| Conditions | Growth cone velocity (μm/hr) |

|---|---|

| Control | 32 ± 41-b |

| 2 mm EGTA | 33 ± 3 |

| 5 mm EGTA | 22 ± 31-a |

| 2 mmNi2+ | 29 ± 7 |

| 4 mmNi2+ | 23 ± 61-a |

| 2 mm Co2+ | 33 ± 9 |

| 4 mmCo2+ | 15 ± 41-a |

| 2 μm BAPTA | 33 ± 3 |

| 4 μmBAPTA | nd |

| 10 μm FPC | 29 ± 4 |

| 20 μm FPC | 7 ± 31-a |

| 2 μm KN-62 | 31 ± 3 |

| 4 μmKN-62 | 13 ± 21-a |

Parallel control experiments were performed for each inhibitor (t test).

Average growth cone velocity of all control experiments. nd, Not determined. 4 μm BAPTA significantly changed growth cone morphology.

CaM activity is essential for growth cone turning

A Ca2+ influx into growth cones induced by LN-coated bead contact could activate numerous target proteins such as CaM, a major intracellular Ca2+ receptor. CaM is very abundant in filopodia and growth cone bodies (Letourneau et al., 1994), where it is targeted to the inner plasma membrane via an association with GAP-43 (Alexander et al., 1987). Phosphorylation of GAP-43 by Ca2+-dependent protein kinase C (PKC) can cause dissociation of the CaM/GAP-43 complex, resulting in the formation of Ca2+/CaM. In fact, PKC activity is critical for growth cone turning signaled by LN-coated beads (Kuhn et al., 1995). Ca2+/CaM binds to, thus activating, a large number of target proteins, including the α and β isoforms of CaM-kinase II, both highly enriched in neurons (for review, seeSchulman, 1988; Brocke et al., 1995). Thus, we tested whether CaM and CaM-kinase II activity were necessary for LN-mediated growth cone navigation.

The addition of 10 μm FPC, an irreversible Ca2+/CaM inhibitor (Hait et al., 1987; Alvarez et al., 1991), negated growth cone turning (11 ± 2% positively responding growth cones, n = 20; p < 0.005) according to the criterion set above (Fig. 2). Growth cone behavior was identical to that described for AM-BAPTA. In contrast, 2 μm KN-62, a specific CaM-kinase II inhibitor (Tokumitsu et al., 1990), had no effect on growth cone turning (76 ± 5% growth cones responding positively, n = 18) as compared with control (79 ± 1% growth cones responding,n = 21). Longer preincubation of DRG neurons with 2 μm KN-62, sufficient to block CaM-kinase II activity in other cell types (Tokumitsu et al., 1990), was also unsuccessful in blocking growth cone turning. Neither 10 μm FPC nor 2 μm KN-62 altered growth cone migration on FN, indicating the specificity of their effects in the standard assay (Table 1). These data imply that CaM is a primary target of the LN-stimulated Ca2+ influx and that Ca2+/CaM is critical to mediate growth cone turning. Subsequent activation of CaM-kinase II is not required for LN-mediated growth cone turning in this assay system.

CaM-kinase II: a regulator of increased rates of outgrowth signaled by LN

Several studies have linked CaM-kinase II activity to increased neurite outgrowth (Goshima et al., 1993; Solem et al., 1995; Williams et al., 1995). Because CaM-kinase II was not required for LN-signaled growth cone turning, we tested whether CaM-kinase II activity was necessary for growth cone behaviors occurring late in the series of stereotypic responses, such as increased rates of outgrowth.

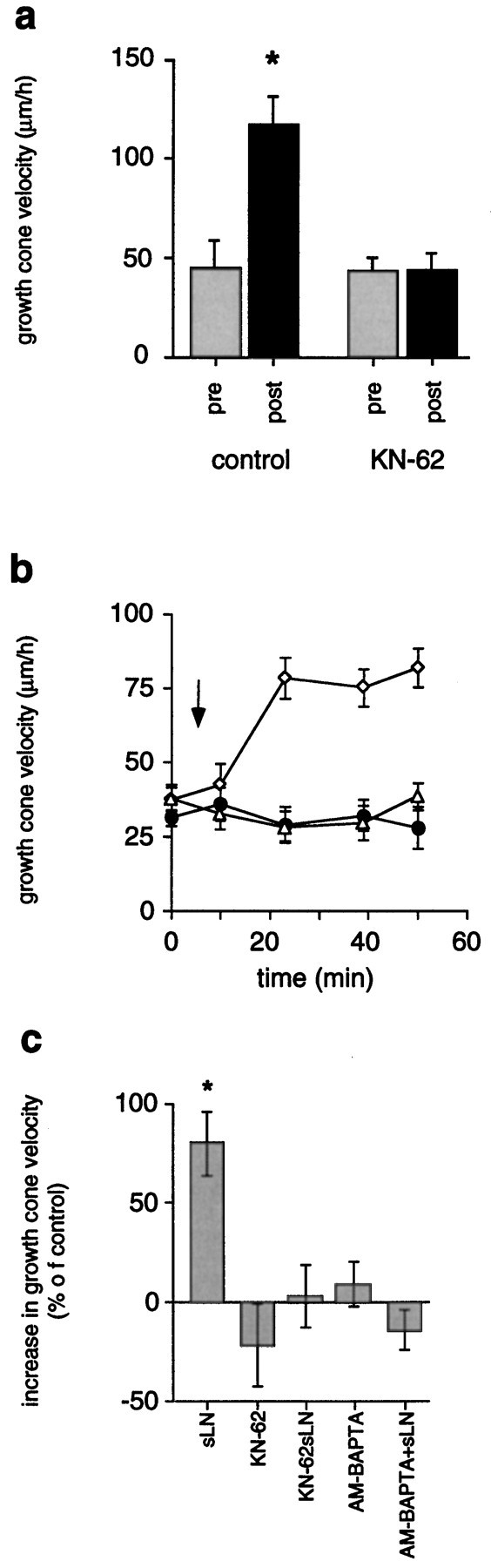

As illustrated in Figure 3a, growth rates on FN significantly increased after transient LN-coated bead contact (117 ± 14 μm/hr, n = 8;p < 0.001) as compared with growth rates before contact (45 ± 13 μm/hr, n = 8), consistent with previous findings (Kuhn et al., 1995). Increased rates of outgrowth lasted for considerable distances beyond LN-coated beads until restoration to FN-like characteristics occurred. In the standard assay, 2 μm KN-62 abolished the period of increased rates of outgrowth (44 ± 8 μm/hr, n = 17) as compared with growth rates measured before LN-coated bead contact (43 ± 7 μm/hr, n = 8). The addition of 20 μl of soluble LN (20 μg/ml) to chick DRG growth cones advancing on FN increased the rates of outgrowth (Fig. 3b,c), in agreement withRivas et al. (1992). Growth rates of 63 ± 10 μm/hr (n = 11; p < 0.01) were measured 30 min after application of LN as opposed to 35 ± 3 μm/hr (n = 11) before the addition of LN. This resulted in a net increase of rates of outgrowth by +80 ± 16% (n = 11) as determined 30 min after LN application. The presence of 2 μm KN-62 prevented this growth-promoting effect of soluble LN (32 ± 5 μm/hr, n = 8, +3 ± 16% increase) as compared with growth rates before the addition of LN (31 ± 3 μm/hr, n = 8). Furthermore, growth cone advance on FN was not altered in the presence of 2 μm KN-62 (29 ± 6 μm/hr, n = 8) as opposed to growth rates on FN in the absence of KN-62 (37 ± 5 μm/hr, n = 8; p > 0.05). Activation of CaM-kinase II critically depends on a preceding elevation of [Ca2+]i. Therefore, preventing a rise of [Ca2+]i should block increased rates of outgrowth. Chelating rises of [Ca2+]i by preloading neurons with 2 μm AM-BAPTA indeed negated the phase of increased rates of outgrowth caused by the addition of soluble LN (Fig. 3c). With intracellular BAPTA, rates of outgrowth before the addition of LN (36 ± 3 μm/hr, n = 14) were identical to rates measured 30 min after the addition of LN (31 ± 3μm/hr,n = 14). It is noteworthy that rates of outgrowth in the absence of intracellular BAPTA were indistinguishable from those determined in the presence of intracellular BAPTA (Table 1; Fig.3c). This suggested that resting [Ca2+]i in advancing growth cones was not lowered significantly by the Ca2+ chelator BAPTA. These results demonstrated that CaM-kinase II activity, preceded by a rise of [Ca2+]i, is necessary for LN-mediated increased rates of outgrowth.

Fig. 3.

CaM-kinase II regulates growth cone motility signaled by LN via increasing rates of outgrowth.a, In the standard assay, growth cones advance with increased rates of outgrowth for considerable distances subsequent to a pause at LN-coated beads (*p < 0.001). Specific inhibition of CaM-kinase II with 2 μm KN-62 prevents this response (pre, before contact;post, after contact). b, The addition of soluble LN to DRG growth cones (FN substrate) stimulates increased rates of outgrowth (open diamonds), whereas the presence of 2 μm KN-62 (open triangles) blocks this effect. Outgrowth on FN in the absence of LN is not significantly affected by KN-62 (filled circles). Anarrow marks the time point of the addition of LN and/or KN-62 (t = 10 min). c, A preceding Ca2+ signal is essential for CaM-kinase II-dependent increases in rates of outgrowth stimulated by LN. Soluble LN (sLN) induces an increase of rates of outgrowth by +80 ± 16% (*p < 0.001). Blocking CaM-kinase II (2 μmKN-62) inhibits the growth-promoting effect of soluble LN (KN-62 + sLN) without affecting growth cone advance on FN (KN-62). Also, chelating rises in [Ca2+]i (AM-BAPTA + sLN) negate increased growth cone motility in response to soluble LN without altering growth cone advance on FN (AM-BAPTA).

Taken together, our pharmacological data indicate that both an influx of extracellular Ca2+ and the formation of Ca2+/CaM are required for LN-mediated growth cone turning. In contrast, CaM-kinase II activity is necessary only for increased rates of outgrowth stimulated by LN-coated bead contact.

A rapid rise in [Ca2+]i in filopodia with LN contact

We used fluorescent Ca2+ imaging with the membrane-permeable calcium indicator fura-2AM (2 μm) to quantify the magnitude of the Ca2+ influx and to determine whether changes in [Ca2+]ioccurred in filopodia adhering to LN-coated beads and/or in the parent growth cones. LN-coated beads were dispersed into cultures of fura-loaded DRG neurons, and the cultures were screened for possible growth cone encounters because our Ca2+ imaging system was not equipped with laser tweezers. Fura-loaded growth cones responded to LN-coated bead encounters with a similar series of stereotypic changes in behavior. Surprisingly, ratiometric Ca2+ imaging during growth cone encounters revealed no rise of [Ca2+]i either in filopodia adhering to LN-coated beads or in parent growth cones, according to the criteria set, despite our pharmacological approach that suggested an LN-stimulated influx of extracellular Ca2+ (see Materials and Methods). We postulated that the Ca2+signal could be masked because of the properties of the intact physical connection beteen filopodia and parent growth cones (Figs. 4, 5, 6).

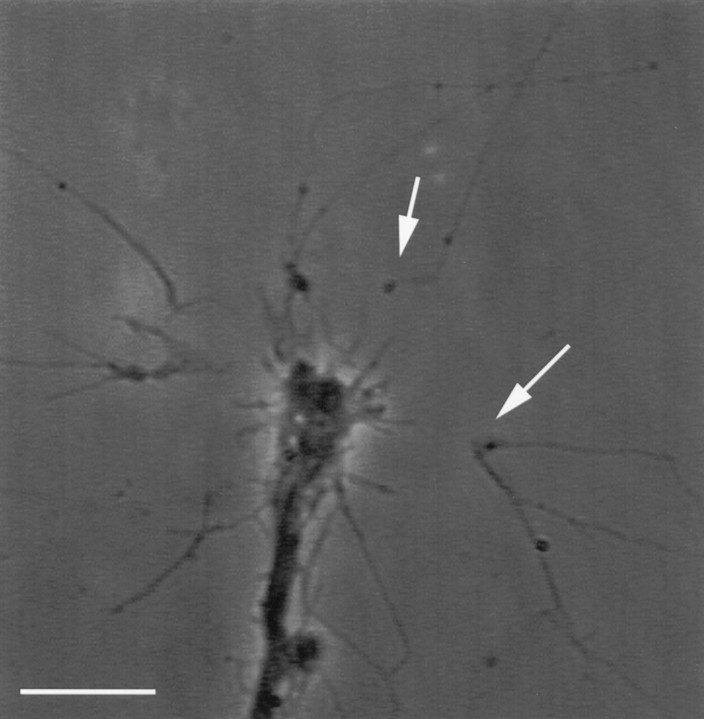

Fig. 4.

Surgical isolation of individual filopodia. Isolated filopodia (arrows), often 20–30 μm long, exhibit intact morphology after laser-assisted transection from their parent, fura-loaded growth cones. A large gap forms between an isolated filopodium and parent growth cone after laser-assisted transection (arrows). This gap results from a retraction of each of the cut ends. This phase picture of a fura-loaded growth cone (5 μm fura-2AM) was taken 20 min after the surgical isolation of filopodia. Scale bar, 10 μm.

Fig. 5.

Top. Soluble LN induces an elevation of [Ca2+]i in surgically isolated filopodia. Using laser scissors, we surgically isolated individual filopodia from growth cones loaded previously with 5 μmfura-2AM for 35 min (phase picture, left panel). Fura images were acquired 30 min after surgical isolation, and only filopodia with stable resting [Ca2+]iwere considered for further experiments (middle panel). Damaged filopodia generally had [Ca2+]i levels >1 μm. Bath application of 20 μl of LN (20 μg/ml) stimulated an immediate rise of [Ca2+]i determined 2 min after LN application (right panel). The color bar shows linear Ca2+ concentrations. Scale bar, 10 μm.

Fig. 6.

Bottom. LN induces a delayed, sustained rise of [Ca2+]i. a, Long-term observation of fura-loaded growth cones during LN-coated bead encounters reveals small but significant rises of [Ca2+]i in growth cones subsequent to a pause at LN-coated beads. No Ca2+ signal is detectable on filopodial contact to LN-coated beads (left panel). After a pause at LN-coated beads, the growth cone continues to advance. During this phase fluorescent Ca2+ imaging reveals a delayed, sustained rise of [Ca2+]i (right panel). The time difference between leftand right panels is 24 min. b, The addition of soluble LN induces rises of [Ca2+]i with characteristics similar to those induced by LN-coated beads. The left panelshows a growth cone immediately after the addition of soluble LN. Note that the growth cones exhibits resting [Ca2+]i. Significant increases in [Ca2+]i become noticeable after 16 min (right panel). c, No gradual increase of [Ca2+]i occurs on contact with LN-coated beads or with the addition of soluble LN. [Ca2+]i (t = 9 min) in growth cones during the delay phase is indistinguishable from resting [Ca2+]i (t= 0 min). According to our criterion (see Materials and Methods), a rise of [Ca2+]i occurs 34 min after bath application of LN. Note that elevations in [Ca2+]i in neurite shafts were smaller than +20 nm, and no significance was assumed. Thecolor bar shows linear Ca2+concentrations. Scale bar, 10 μm.

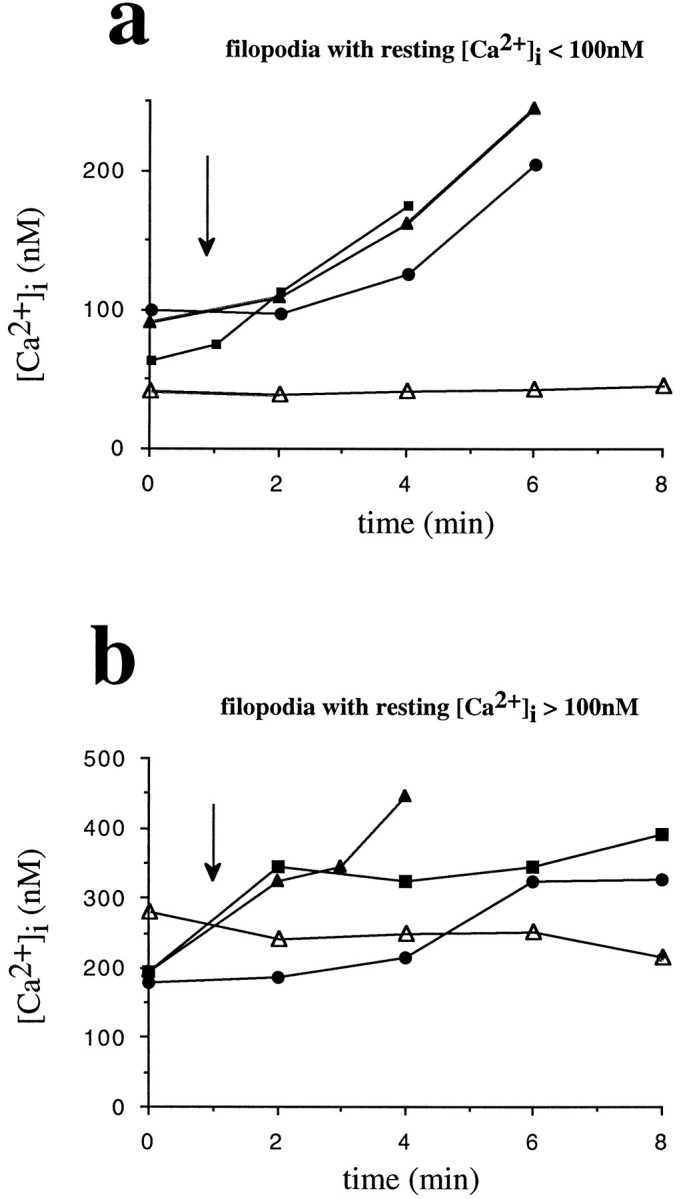

Individual filopodia after transection from their parent growth cones have been used successfully to quantify small, local changes in [Ca2+]i elicited by external stimuli (Davenport et al., 1993). Using a laser scissors system, we surgically isolated individual filopodia from growth cones loaded with fura-2AM (5 μm), transferred them to the Ca2+imaging system, and determined [Ca2+]i30 min after laser-assisted transection (Figs.4, 5). Only isolated filopodia with stable [Ca2+]iand intact morphology were included in our study. Also, we substituted soluble LN for LN-coated beads because our Ca2+imaging system was not equipped with laser tweezers, so an application of LN-coated beads to isolated filopodia was impossible. Of 22 isolated filopodia with intact morphology, 12 filopodia exhibited stable resting [Ca2+]i <100 nm (83 ± 6 nm, n = 12). The remaining 10 isolated filopodia also had stable resting [Ca2+]i that was >100 nm, ranging from 150 to 400 nm. Of the 12 isolated filopodia with resting [Ca2+]i <100 nm, nine reacted with a rapid rise of [Ca2+]i (+73 ± 11 nm; n = 12; p < 0.001) on the addition of soluble LN (20 μl, 20 μg/ml), peaking at 156 ± 14 nm (Figs. 5, 7a). As our control, bath application of FN (20 μl, 20 μg/ml) had no effect on [Ca2+]i in transected filopodia with resting [Ca2+]i <100 nm(Fig. 7a). Nevertheless, the 10 isolated filopodia with resting [Ca2+]i >100 nm also responded with rapid changes in [Ca2+]i (+118 ± 23 nm; n = 10) to an addition of soluble LN (Fig. 7b).

Fig. 7.

Soluble LN stimulates a rapid increase of [Ca2+]i in surgically isolated filopodia. a, Filopodia with resting [Ca2+]i <100 nm responded with a rapid rise of [Ca2+]i to bath-applied LN (20 μl, 20 μg/ml). LN was added att = 2 min (arrow), and significant increases in [Ca2+]i were measured att = 4 min. Three representative isolated filopodia are shown (filled symbols). Identical concentrations of soluble FN had no effect (open triangles). b, Filopodia with resting [Ca2+]i >100 nm also responded to soluble LN (t = 2 min) with a rapid increase of [Ca2+]i(t = 4 min). Data from three representative isolated filopodia are plotted (filled symbols). As a control, the addition of soluble FN has no effect on [Ca2+]i (open triangles). Substrate of neuronal culture = FN.

Taken together, surgically isolated filopodia react to the addition of soluble LN with an immediate, rapid rise of [Ca2+]i irrespective of the current resting [Ca2+]i. This finding, combined with our pharmacological data, suggests that LN-mediated growth cone turning requires an influx of extracellular Ca2+ most likely occurring into filopodia with LN contact.

A sustained rise of [Ca2+]i in growth cones subsequent to a pause at LN-coated beads is associated with increased rates of outgrowth

In the standard assay, growth cones responded to transient LN-coated bead contact with sustained, increased rates of outgrowth. Previous findings have demonstrated that growth cone motility is very sensitive even to subtle changes in [Ca2+]i (Kater and Mills, 1991). Therefore, we measured [Ca2+]i during the entire series of stereotypic growth cone responses, including the period of increased rates of outgrowth.

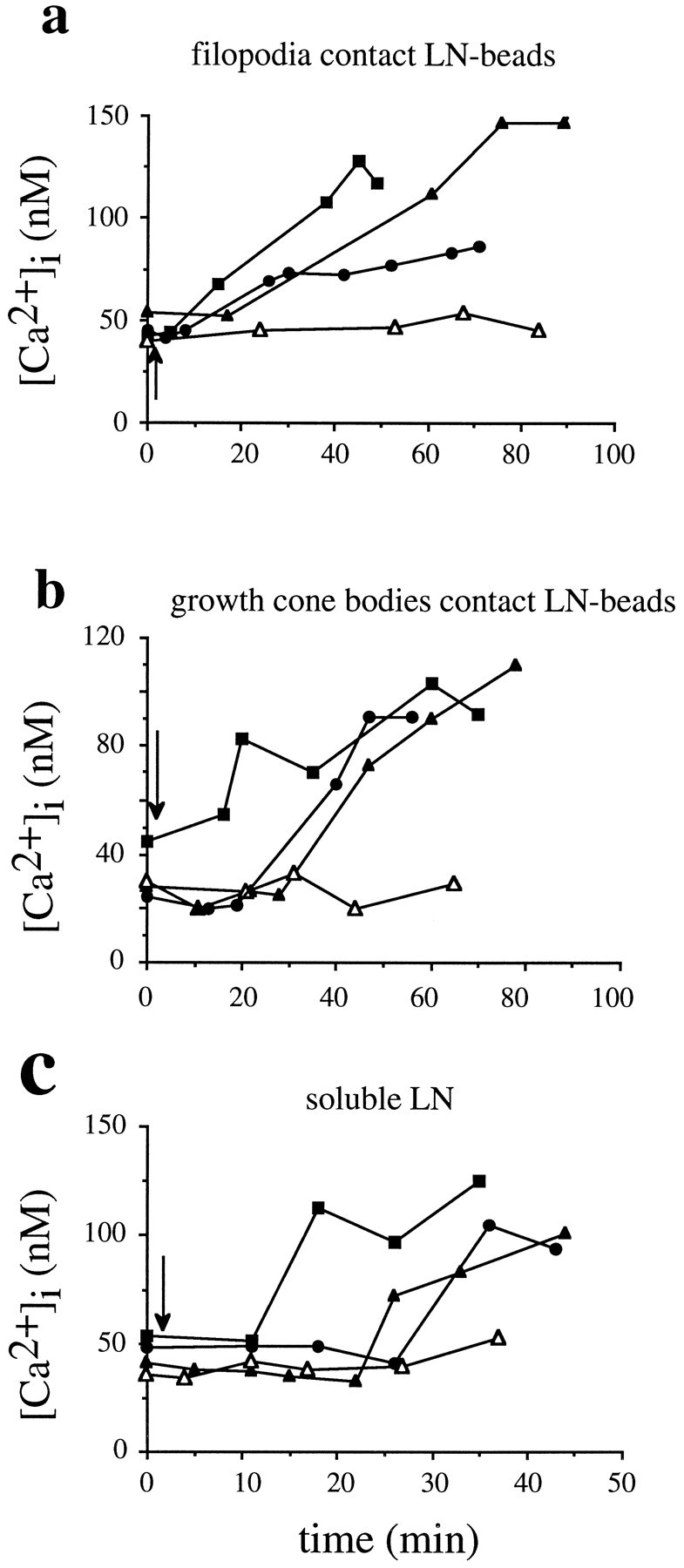

We found that, subsequent to a pause at LN-coated beads, growth cones exhibited small but significant rises of [Ca2+]i (83 ± 2%,n = 20 of 24; p < 0.0001), peaking at 105 ± 6 nm, as compared with average resting [Ca2+]i of 42 ± 2 nm(n = 14) (Fig.6a). [Ca2+]i remained elevated, whereas growth cones advanced considerable distances beyond LN-coated beads (72 ± 7% of growth cones investigated, n = 17 of 24). Most importantly, rises of [Ca2+]i occurred with a distinct delay of 28 ± 3 min (n = 24) after growth cones first contacted LN-coated beads (Fig.8a) and strongly correlated in time with the period of increased rates of outgrowth (delay >20 min after first LN-coated bead contact). In control experiments no changes in [Ca2+]i were observed in growth cones that encountered FN-coated beads on an FN substrate.

Fig. 8.

LN stimulates a second, sustained rise of [Ca2+]i that is temporally distinct from the Ca2+ influx in filopodia contacting LN.a, Time course of changes in [Ca2+]i are plotted for three individual growth cones advancing on FN after encountering LN-coated beads with their filopodia (filled symbols). Thearrow marks the time point when growth cones first contacted LN-coated beads. [Ca2+]iincreases with a distinct delay after contact. LN-coated beads elicit no rise of [Ca2+]i if contacting a neurite shaft (open triangles). b, Growth cones with no previous filopodial contact to LN-coated beads also exhibit delayed rises of [Ca2+]i(filled symbols). This suggests that this delay is not a trivial consequence of growth cones approaching LN-coated beads after filopodial contact, together with a gradual rise of [Ca2+]i. Note that [Ca2+]i remained at resting levels for >20 min. c, Soluble LN induces a delayed, sustained increase in [Ca2+]i with similar characteristics to those observed for LN-coated beads. Measurements of three representative growth cones are shown (filled symbols). Growth cones advancing on FN do not respond with changes in [Ca2+]i on the addition of soluble FN (open triangles).

This delayed, sustained Ca2+ signal could have been temporally distinct from the Ca2+ influx into filopodia induced on LN contact or simply a trivial consequence of the standard assay: a slow but steady elevation of [Ca2+]i initiated by filopodial contact to LN-coated beads and a concomitant approach to LN-coated beads by the growth cone. To test these two alternatives, we selectively measured rises of [Ca2+]iin growth cones contacting LN-coated beads only with their body and having no previous contact with filopodia, thus eliminating the approach phase to LN-coated beads (Fig. 8b). Here, LN-induced rises of [Ca2+]i were characterized by (1) a delay of 29 ± 6 min occurring after the first contact of growth cone bodies to LN-coated beads, (2) an elevation of [Ca2+]i peaking at +103 ± 7 nm (n = 12 of 17) (resting [Ca2+]i = 42 ± 2 nm,n = 14), (3) a temporal correlation with the period of increased rates of outgrowth, and (4) a sustained elevation of [Ca2+]i, while growth cones advanced considerable distances beyond LN-coated beads. No changes in [Ca2+]i were observed when LN-coated beads directly contacted neurite shafts with no previous contact to either filopodia or growth cones (open triangles in Fig. 8b). Regardless of the mode of LN presentation, levels of [Ca2+]i in growth cones during the delay phase (40 ± 2 nm, n = 26) were not significantly different from levels of [Ca2+]i before any LN contact (resting [Ca2+]i = 42 ± 2 nm,n = 14). These data demonstrated that the delayed, sustained Ca2+ signal was not simply a trivial consequence of our standard assay but a temporally distinct event.

Soluble laminin (20 μl, 20 μg/ml) induced rises of [Ca2+]i in growth cones with characteristics indistinguishable from those described for the delayed, sustained Ca2+ signal induced by LN-coated bead contact (Figs. 6b, 8c). Rises of [Ca2+]i peaked at 142 ± 11 nm (+94 ± 11 nm, n = 12 of 14; p < 0.001) as compared with resting [Ca2+]i (46 ± 8 nm,n = 12) and occurred with a distinct delay of 20 ± 4 min (n = 13) after the addition of soluble LN. Elevated levels of [Ca2+]i were sustained and correlated with increased rates of outgrowth detectable 15 min after the addition of soluble LN. As our controls, soluble FN (20 μl, 20 μg/ml) had no effect on [Ca2+]i (51 ± 3 nm,n = 6; average resting [Ca2+]i = 45 ± 2 nm,n = 6), and soluble LN caused no significant rises in [Ca2+]i (36 ± 3 nm,n = 8) in growth cones advancing on LN (average resting [Ca2+]i = 32 ± 2 nm,n = 8) (open triangles in Fig.8c). A small number of growth cones advancing on LN responded to soluble LN with a positive rise in [Ca2+]i (27%, n = 3 of 11) according to the criterion set (see Materials and Methods). However, we assumed no significance because [Ca2+]i peaked at 50 ± 5 nm and increased only by +16 ± 3 nm.

Our results show that growth cones respond to a LN stimulus with a delayed, sustained rise of [Ca2+]iirrespective of filopodial contact, direct growth cone body contact, or both, as in the case of soluble LN. This finding strongly suggests that the delayed, sustained Ca2+ signal is temporally (delay >20 min) and functionally (association with the period of increased rates of outgrowth) distinct from the first Ca2+ signal, which is characterized by a delay of <2 min and by an association with growth cone turning.

CaM-kinase II regulates the delayed, sustained rise in [Ca2+]i

We have identified a delayed, sustained rise of [Ca2+]i in growth cones associated with the period of increased rates of outgrowth, both resulting from a transient contact to LN-coated beads. We have shown previously that inhibition of CaM-kinase II abolished the period of increased rates of outgrowth. Thus, we examined whether the delayed, sustained rise of [Ca2+]i was sensitive to CaM-kinase II inhibition.

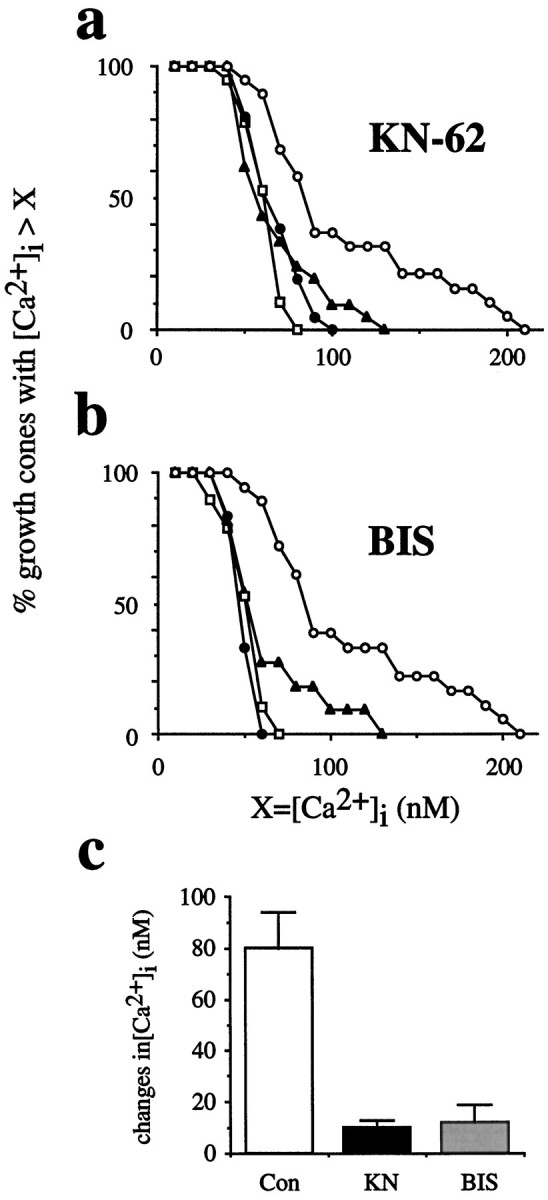

The addition of soluble LN (20 μl, 20 μg/ml) significantly shifted the distribution of [Ca2+]i in a population of growth cones to higher levels of [Ca2+]i according to the criterion set (see Materials and Methods) (Fig.9a). Average resting [Ca2+]i of 48 ± 3 nmwas determined before LN addition, whereas [Ca2+]i peaked at 111 ± 13 nm (n = 17 of 19) after the addition of LN. In the presence of KN-62, soluble LN induced no shift in the distribution of [Ca2+]i (Fig.9a). Resting levels of [Ca2+]i in the presence of KN-62 (47 ± 3 nm) were not affected, as opposed to levels of [Ca2+]i in the absence of KN-62 (48 ± 3 nm). According to the criterion set (see Materials and Methods), 33% (n = 7 of 21) of growth cones exhibited a statistically significant rise in [Ca2+]i (t test). However, we assumed no true significance because the actual net change in [Ca2+]i was only 10 ± 3 nm.

Fig. 9.

CaM-kinase II and PKC regulate the delayed, sustained rise of [Ca2+]i.a, Inhibition of CaM-kinase II (KN-62) blocks LN-induced rises in [Ca2+]i. The distribution of [Ca2+]i of a population of growth cones is plotted against [Ca2+]i. Open squaresillustrate the distribution of resting [Ca2+]i in growth cones advancing on FN. After the addition of soluble LN, a large number of growth cones respond with rises of [Ca2+]i, and the distribution of [Ca2+]i shifts to higher [Ca2+]i (open circles). A presence of 2 μm KN-62 negates the shift in the distribution of [Ca2+]iexpected on the addition of soluble LN (filled triangles). The distribution of resting [Ca2+]i is unaffected by KN-62 (filled circles). b, In the presence of 10 nm bisindolylmaleimide (BIS), a specific PKC inhibitor, the distribution of resting [Ca2+]i (filled circles) is identical to that under control conditions (open squares). However, BIS blocks the expected change in the distribution of [Ca2+]i in growth cones on the addition of soluble LN (closed triangles).c, The change in [Ca2+]i induced by soluble LN is shown as a function of the inhibitors that are present. Inhibition of both CaM-kinase II [KN-62 (KN)] and PKC [bisindolylmaleimide (BIS)] negates LN-induced rises in [Ca2+]i. Con, Control conditions.

Previous studies had shown that inhibition of PKC blocked all growth cone responses in the standard assay subsequent to growth cone turning (Kuhn et al., 1995). Therefore, we examined the effect of PKC inhibition on the delayed, sustained rise of [Ca2+]i. The presence of 10 nm bisindolylmaleimide (BIS), a specific PKC inhibitor (Toullec et al., 1991), clearly blocked an LN-stimulated shift in the distribution of [Ca2+]i in growth cones advancing on FN, whereas 10 nm BIS had no effect on the distribution of resting levels of [Ca2+]i as compared with control (Fig.9b). In summary, KN-62 and BIS both blocked the delayed, sustained change in [Ca2+]i in growth cones stimulated by soluble LN (Fig. 9c). The effect of the CaM-inhibitor, FPC, could not be assessed because resting [Ca2+]i was affected by this inhibitor. With respect to these findings, CaM-kinase II, PKC, and potentially Ca2+/CaM are involved in regulating the delayed, sustained Ca2+ signal in growth cones stimulated by LN.

DISCUSSION

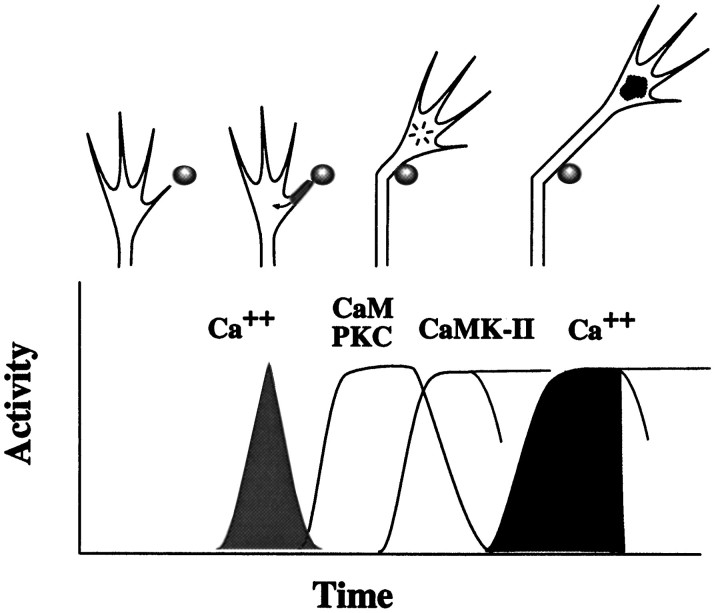

This in vitro study provided evidence that LN-mediated growth cone guidance, a stereotypic series of changes in growth cone behavior and morphology, could be attributed to two temporally and functionally distinct Ca2+ signals linked by a sequential signaling cascade composed of PKC, CaM, and CaM-kinase II (Fig. 10).

Fig. 10.

Proposed mechanism underlying LN-mediated growth cone guidance in vitro. Our results suggest that guidance instructions provided by LN-coated beads activate a signaling mechanism composed of two temporally and functionally distinct Ca2+ signals that are linked sequentially byCaM, PKC, and CaM-kinase II (CaMK-II). Growth cones establish contact to LN-coated beads with individual filopodia. This adhesion event stimulates in an influx of extracellular Ca2+, presumably at adhesion sites between filopodia and LN-coated beads, resulting in a rise of [Ca2+]i(shading adherent filopodia). This early Ca2+ signal is required for growth cone turning, together with an activation of downstream targets (arrow), including CaM and PKC (markedinside the growth cone). This is followed by a Ca2+/CaM-dependent activation of CaM-kinase II, which regulates both the delayed and sustained rise of [Ca2+]i associated with the period of increased rates of outgrowth (dark shading inside the growth cone).

Ca2+ signaling in filopodia

Growth cone guidance in vivo and in vitro, irrespective of the attractive or repulsive nature of environmental cues, depends on the enormous sensory capacity of individual filopodia (O’Connor et al., 1990; Chien et al., 1993; Fan and Raper, 1995; Li et al., 1996) (for review, see Kater and Rehder, 1995). Recently, it has been shown that filopodia are even essential for growth cone guidance by diffusible cues (Zheng et al., 1996). In our standard assay, adhesion of individual filopodia to LN-coated beads induced growth cone redirection. Although our pharmacological approach indicated an influx of extracellular Ca2+ required for LN-mediated turning, fluorescent Ca2+ imaging revealed no change in [Ca2+]i either in attached filopodia or in parent growth cones. In principle, pharmacological inhibition of growth cone turning could have resulted indirectly from a significant decrease of resting [Ca2+]i in advancing growth cones. However, several lines of evidence speak against this alternative. Growth cones loaded with fura-2 displayed a similar series of stereotypic behavior in the standard assay, although fura-2 does affect resting [Ca2+]i. A significant decrease of resting [Ca2+]i should attenuate growth cone migration (Kater and Mills, 1991), but our pharmacological conditions had no effect on growth cone advance on FN (Table 1). Instead, higher inhibitor concentrations were detrimental for advancing growth cones. In addition, resting [Ca2+]i in DRG neurons remained stable at nominal zero extracellular Ca2+ and in the presence of Ni2+ (Gomez et al., 1995) or with intracellular BAPTA (KD = 100–3600 μm) (Tymianski et al., 1994). These arguments strongly favored a direct pharmacological inhibition of growth cone turning in the standard assay. We postulated that LN contact induced an influx of extracellular Ca2+ that was masked in attached filopodia. It was conceivable that this Ca2+ influx occurred in filopodia with LN contact.

Filopodia possess a relatively large surface area-to-volume ratio; consequently, a rise of [Ca2+]i ≤100 nm is composed of only a small number of Ca2+ ions (Davenport et al., 1993). Taking into account the small number of Ca2+ ions and the spatial restriction of the LN-stimulus in the bead assay, we theorized that the masking of a Ca2+ signal in attached filopodia could result from (1) extrusion of Ca2+ions into the extracellular space, (2) sequestration of Ca2+ ions by Ca2+ binding proteins or into intracellular stores, and/or (3) a dilution of Ca2+ ions after rapid diffusion into parent growth cones. Extrusion of Ca2+ ions into the extracellular space by Ca2+–ATPase is one major regulatory mechanism in neuronal growth cones (Werth et al., 1996). CaM could play a critical role in Ca2+-dependent signaling mechanisms because it is a major intracellular receptor for Ca2+. CaM binds significant amounts of Ca2+ at concentrations slightly above resting [Ca2+]i (James et al., 1995) and is abundant in filopodia (Letourneau et al., 1994). Relevant to this study, CaM inhibition blocked all growth cone responses after filopodial adhesion. VanBerkum and Goodman (1995) have demonstrated that the expression of inactive CaM mutants resulted in severe growth cone pathfinding errors, and focal inactivation of calcineurin, a CaM-dependent phosphatase, caused asymmetric retraction of filopodia (Chang et al., 1995).

Surgically isolated filopodia have been used successfully to demonstrate changes in [Ca2+]i in individual filopodia despite the nonphysiological nature of the experiment (Davenport et al., 1993, 1996). We measured a rapid accumulation of Ca2+ in surgically isolated filopodia from chick DRG growth cones almost immediately after the application of soluble LN. This unmasking of an LN-stimulated Ca2+ influx could be attributed either to an incapacity of Ca2+ extrusion into the extracellular space because of a lack of ATP supply from mitochondria in the parent growth cone (Werth et al., 1996) and/or to a saturation of Ca2+ binding proteins. Conclusively, proper engagement of Ca2+ clearing mechanisms in filopodia would require, at least to some extent, a physically intact connection between filopodia and the parent growth cone. Furthermore, it is reasonable that LN-coated beads elicit a similar, however masked, Ca2+ influx in adhering filopodia in regard to the results obtained with soluble LN in isolated filopodia and our pharmacological data in the standard assay.

Ca2+ signals, CaM-kinase II activity, and their effects on growth cone motility

Rises in [Ca2+]i can induce a variety of growth cone responses from the inhibition of motility (Haydon et al., 1984; Robson and Burgoyne, 1989; Fields et al., 1993) to the promotion of motility (Holliday and Spitzer, 1990; Bedlack et al., 1992). Normal growth cone function depends on an optimal range of [Ca2+]i (al-Mohanna et al., 1992), whereas changes in [Ca2+]i above or below this optimal range inhibit neurite outgrowth (Mattson and Kater, 1987; Kater and Mills, 1991).

In our experiments, the delayed, sustained Ca2+signal was small in magnitude and correlated in time with increased rates of outgrowth. This implied that LN promoted growth cone motility via a small rise in [Ca2+]i. Ca2+ signals in neurons stimulated by extracellular matrix (ECM) molecules have been described by Bixby et al. (1994) andGomez et al. (1995), whereas others have proposed Ca2+-independent mechanisms (Campenot and Draker, 1989; Williams et al., 1992). In many non-neuronal cells, ECM-dependent adhesion, motility, and chemotaxis are associated with Ca2+ signals (for review, see Sjaastad and Nelson, 1997). In our hands, the acute addition of LN to cultured DRG neurons elicited small but significant rises of [Ca2+]i in growth cones. Paradoxically, growth cones on a FN or a LN substratum exhibited resting levels of [Ca2+]i although Ca2+ chelators and general Ca2+channel inhibitors reduced growth cone advance, thus indicating an essential tonic Ca2+ influx (Bixby at al., 1994). A similar discrepancy between acute versus tonic Ca2+influx had been reported for L1, NCAM, and N-cadherin. Growth cone advance on these substrates depended on a tonic Ca2+ influx through voltage-gated L- and N-type Ca2+ channels (Doherty et al., 1991; Williams et al., 1992), but [Ca2+]i remained at resting levels (Harper et al., 1994). Instead, acute activation of L1 or NCAM induced rises of [Ca2+]iclearly above resting [Ca2+]i (Schuch et al., 1989; Von Bohlen und Halbach et al., 1992). In conclusion, tonic stimuli apparently affected rates of Ca2+cycling rather than steady-state levels of [Ca2+]i (Harper et al., 1994).

Three types of LN applications were tested to determine conclusively whether the delayed, sustained Ca2+ was a trivial consequence of our LN-coated bead assay, i.e., a gradually increasing Ca2+ signal initiated by filopodial contact concomitant with a growth cone approach toward LN beads, or a temporally distinct event. Irrespective of the mode of LN presentation, a distinct delay phase preceded the sustained rise of [Ca2+]i: 28 ± 3 min after first filopodial contact in the standard assay, 29 ± 6 min after LN contact to growth cone bodies without previous filopodial contact, and 20 ± 4 min after the addition of soluble LN. During the delay phase under each test condition, levels of [Ca2+]i were indistinguishable from resting [Ca2+]i. Therefore, the delayed, sustained Ca2+ signal was temporally distinct from the immediate Ca2+ signal induced on LN-coated bead contact. The two Ca2+ signals were also functionally distinct with respect to their association with two independent growth cone behaviors, i.e., turning versus increased growth cone motility, both clearly separated in time.

In the standard assay the delayed, sustained Ca2+signal and the period of increased rates of outgrowth depended on CaM-kinase II activity. Very similarly, an influx of extracellular Ca2+ and CaM-kinase II activity were both essential for turning and navigation of growth cones toward a gradient of acetylcholine (Zheng et al., 1994). CaM-kinase II activity, downstream of a Ca2+ influx, was specifically required for neurite outgrowth promoted by L1, NCAM, and N-cadherin (Williams et al., 1995). Other investigations also link increased CaM-kinase II activity with the promotion of neurite elongation and growth cone motility (Goshima et al., 1993; Solem et al., 1995; Zou and Cline, 1996; Masse and Kelly, 1997). CaM-kinase II, often associated with actin filaments, can phosphorylate tubulin among various other substrates (Goldenring et al., 1983). Such a modification of tubulin could, in principle, alter microtubule assembly as well as growth cone motility. Many investigations have demonstrated that CaM-kinase II is critically involved in the conversion of single spike-like Ca2+ signals into sustained messages, because autophosphorylation of CaM-kinase II results in a Ca2+/CaM-independent state of sustained kinase activity (Fong et al., 1989) (for review, see Hanson and Schulman, 1992). In this respect, it is an intriguing coincidence that sustained effects on growth cone motility apparently were associated with sustained CaM-kinase II activity.

In summary, it becomes increasingly evident that a complex network of signaling molecules is coordinated precisely in space, time, and activity when growth cones perform even the simplest pathfinding task: translating guidance information provided by a single molecule into navigational changes. Additional complexity could evolve from long-lasting activation of signaling molecules that, consequently, influence future navigational decisions of a single growth cone.

Footnotes

This work was supported by a fellowship from the Swiss National Foundation to T.B.K. and National Institutes of Health Grant NS24683 to S.B.K. We thank Drs. Jim Bamburg and Mark Wright for critical comments and helpful suggestions on this manuscript. Also, we thank Dennis Giddings and Christine Porter for technical assistance.

Correspondence should be addressed to Dr. Thomas B. Kuhn, Department of Biochemistry and Molecular Biology, Colorado State University, Fort Collins, CO 80523.

REFERENCES

- 1.Alexander KA, Cimler BM, Meier KE, Storm DT. Regulation of calmodulin binding to P-57. J Biol Chem. 1987;262:6108–6113. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.al-Mohanna FA, Cave J, Bolsover SR. A narrow window of intracellular calcium concentration is optimal for neurite outgrowth in rat sensory neurons. Brain Res Dev Brain Res. 1992;70:287–290. doi: 10.1016/0165-3806(92)90209-f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Alvarez J, Montero M, Garcia-Sandro J. Cytochrome P-540 may link intracellular Ca2+ stores with plasma membrane Ca2+ influx. Biochem J. 1991;274:193–197. doi: 10.1042/bj2740193. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Bedlack RS, Wei MD, Loew LM. Localized membrane depolarizations and localized calcium influx during electric field-guided neurite growth. Neuron. 1992;9:393–403. doi: 10.1016/0896-6273(92)90178-g. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Bentley D, Guthrie PB, Kater SB. Calcium ion distribution in nascent pioneer axons and coupled preaxogenesis neurons in situ. J Neurosci. 1991;11:1300–1308. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.11-05-01300.1991. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Bixby JL, Grunwald GB, Bookman RJ. Ca2+ influx and neurite growth in response to purified N-cadherin and laminin. J Cell Biol. 1994;127:1461–1475. doi: 10.1083/jcb.127.5.1461. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Bolsover SR, Spector I. Measurements of calcium transients in the soma, neurite, and growth cone of single cultured neurons. J Neurosci. 1986;6:1934–1940. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.06-07-01934.1986. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Brocke L, Srinivasan M, Schulman H. Developmental and regional expression of multifunctional Ca2+/calmodulin-dependent kinase isoforms in rat brain. J Neurosci. 1995;15:6797–6808. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.15-10-06797.1995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Campenot RB, Draker DD. Growth of sympathetic nerve fibers in culture does not require extracellular calcium. Neuron. 1989;3:733–743. doi: 10.1016/0896-6273(89)90242-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Chang HY, Takei K, Sydor AM, Born T, Rusnak F, Jay DG. Asymmetric retraction of growth cone filopodia following focal inactivation of calcineurin. Nature. 1995;376:686–690. doi: 10.1038/376686a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Chien C, Rosenthal DE, Harris WA, Holt CE. Navigational errors made by growth cones without filopodia in the embryonic Xenopus brain. Neuron. 1993;11:237–251. doi: 10.1016/0896-6273(93)90181-p. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Clapham DE. Calcium signaling. Cell. 1995;80:259–268. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(95)90408-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Davenport RW, Dou P, Rehder V, Kater SB. A sensory role for neuronal growth cone filopodia. Nature. 1993;361:721–724. doi: 10.1038/361721a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Davenport RW, Dou P, Mills LR, Kater SB. Distinct calcium signaling within neuronal growth cones and filopodia. J Neurobiol. 1996;31:1–15. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1097-4695(199609)31:1<1::AID-NEU1>3.0.CO;2-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Doherty P, Walsh FS. Signal transduction events underlying neurite outgrowth stimulated by cell adhesion molecules. Curr Opin Neurobiol. 1994;4:49–55. doi: 10.1016/0959-4388(94)90031-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Doherty P, Ashton SV, Moore SE, Walsh FS. Morphoregulatory activities of NCAM and N-cadherin can be accounted for by G-protein-dependent activation of L- and N-type neuronal calcium channels. Cell. 1991;67:21–34. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(91)90569-k. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Fan J, Raper JA. Localized collapsing cues can steer growth cones without introducing their full collapse. Neuron. 1995;14:263–274. doi: 10.1016/0896-6273(95)90284-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Fields RD, Guthrie PB, Russell JT, Kater SB, Malhorta BS, Nelson PG. Accommodation of mouse DRG growth cones to electrically induced collapse: kinetic analysis of calcium transients and set-point theory. J Neurobiol. 1993;24:1080–1098. doi: 10.1002/neu.480240807. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Fong YL, Taylor WL, Jeans AR, Sonderling TR. Studies of the regulatory mechanism of Ca2+/calmodulin-dependent protein kinase II. Mutation of threonine 286 to alanine and aspartate. J Biol Chem. 1989;264:26759–26763. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Ghosh A, Greenberg ME. Calcium signaling in neurons: molecular mechanisms and cellular consequences. Science. 1995;268:239–247. doi: 10.1126/science.7716515. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Goldenring JR, Gonzales B, McGuire JS. Purification and characterization of a calmodulin-dependent kinase from rat brain cytosol able to phosphorylate tubulin and microtubule-associated protein. J Biol Chem. 1983;258:12632–12640. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Gomez TM, Snow DM, Letourneau PC. Characterization of spontaneous calcium transients in nerve growth cones and their effect on growth cone migration. Neuron. 1995;14:1233–1246. doi: 10.1016/0896-6273(95)90270-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Goodman CS, Shatz CJ (1993) Developmental mechanisms that generate precise patterns of neuronal connectivity. Cell 72/Neuron 10[Suppl]:77–98. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 24.Goshima Y, Ohsako S, Yamauchi T. Overexpression of Ca2+/calmodulin-dependent protein kinase II in Neuro2A and NG108-15 neuroblastoma cell lines promotes neurite outgrowth and growth cone motility. J Neurosci. 1993;13:559–567. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.13-02-00559.1993. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Gottmann K, Lux HD. Growth cone calcium ion channels: properties, clustering, and functional roles. Perspect Dev Neurobiol. 1995;2:371–377. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Grynkiewicz G, Poenie M, Tsien RY. A new generation of Ca2+ indicators with greatly improved fluorescence properties. J Biol Chem. 1985;260:3440–3445. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Hait WN, Glazer L, Kaiser C, Cross J, Kennedy KA. Pharmacological properties of fluphenazine-mustard, an irreversible calmodulin antagonist. Mol Pharmacol. 1987;32:404–409. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Hanson PI, Schulman H. Neuronal Ca2+/calmodulin-dependent protein kinases. Annu Rev Biochem. 1992;61:559–601. doi: 10.1146/annurev.bi.61.070192.003015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Harper SJ, Bolsover SR, Walsh FS, Doherty P. Neurite outgrowth stimulated by L1 requires calcium influx into neurons but is not associated with changes in steady state levels of calcium in growth cones. Cell Adhes Commun. 1994;2:441–453. doi: 10.3109/15419069409004454. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Haydon PG, McCobb DP, Kater SB. Serotonin selectively inhibits growth cone motility and the connectivity of identified neurons of Helisoma. J Neurosci Res. 1984;13:135–147. [Google Scholar]

- 31.Holliday J, Spitzer NC. Spontaneous calcium influx and its roles in differentiation of spinal neurons in culture. Dev Biol. 1990;141:13–23. doi: 10.1016/0012-1606(90)90098-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Hynes RO, Lander AD. Contact and adhesive specificities in the association, migration, and targeting of cells and axons. Cell. 1992;86:303–322. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(92)90472-o. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.James P, Vorherr T, Carafoli E. Calmodulin-binding domains: just two-faced or multi-faceted? Trends Biochem Sci. 1995;20:38–42. doi: 10.1016/s0968-0004(00)88949-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Kater SB, Mills LR. Regulation of growth cone behavior by calcium. J Neurosci. 1991;11:891–899. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.11-04-00891.1991. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Kater SB, Rehder V. The sensory-motor role of growth cone filopodia. Curr Opin Neurobiol. 1995;5:68–74. doi: 10.1016/0959-4388(95)80089-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Kuhn TB, Schmidt MF, Kater SB. Laminin and fibronectin guideposts signal sustained by opposite effects to passing growth cones. Neuron. 1995;14:275–285. doi: 10.1016/0896-6273(95)90285-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Letourneau PC, Snow DM, Gomez TM. Growth cone motility: substratum-bound molecules, cytoplasmic [Ca2+], and Ca2+-regulated proteins. Prog Brain Res. 1994;102:35–48. doi: 10.1016/S0079-6123(08)60530-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Li M, Shibata A, Li C, Braun RE, McKerracher L, Roder J, Kater SB, David S. Myelin-associated glycoprotein inhibits neurite/axon growth and causes growth cone collapse. J Neurosci Res. 1996;46:404–414. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1097-4547(19961115)46:4<404::AID-JNR2>3.0.CO;2-K. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Masse T, Kelly PT. Overexpression of Ca2+/calmodulin-dependent protein kinase II in PC12 cells alters cell growth, morphology, and nerve growth factor-induced differentiation. J Neurosci. 1997;17:924–931. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.17-03-00924.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Mattson MP, Kater SB. Calcium regulation of neurite outgrowth and growth cone motility. J Neurosci. 1987;7:4034–4043. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.07-12-04034.1987. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.O’Connor TP, Duerr JS, Bentley D. Pioneer growth cone steering decisions mediated by single filopodial contact in situ. J Neurosci. 1990;10:3935–3946. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.10-12-03935.1990. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Rivas RJ, Burmeister DW, Goldberg DJ. Rapid effects of laminin on the growth cone. Neuron. 1992;8:107–115. doi: 10.1016/0896-6273(92)90112-q. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Robson SJ, Burgoyne RD. L-type calcium channels in the regulation of neurite outgrowth from rat dorsal root ganglion neurons in culture. Neurosci Lett. 1989;104:110–114. doi: 10.1016/0304-3940(89)90338-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Schuch U, Lohse MJ, Schachner M. Neural cell adhesion molecules influence second messenger systems. Neuron. 1989;3:13–20. doi: 10.1016/0896-6273(89)90111-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Schulman H. The multifunctional Ca2+/CaM-dependent protein kinase. Adv Second Messenger Phosphoprotein Res. 1988;22:39–111. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Silver RA, Lamb AG, Bolsover SR. Calcium hotspots caused by L-channel clustering promote morphological changes in neuronal growth cones. Nature. 1990;343:751–754. doi: 10.1038/343751a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Sjaastad MD, Nelson WJ. Integrin-mediated calcium signaling and regulation of cell adhesion by intracellular calcium. BioEssays. 1997;19:47–55. doi: 10.1002/bies.950190109. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Solem M, McMahon T, Messing RO. Depolarization-induced neurite outgrowth in PC-12 cells requires permissive, low-level NGF receptor stimulation and activation of calcium/calmodulin-dependent protein kinase. J Neurosci. 1995;15:5966–5975. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.15-09-05966.1995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Tanaka E, Sabry J. Making the connection, cytoskeletal rearrangements during growth cone guidance. Cell. 1995;83:171–176. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(95)90158-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Tokumitsu H, Chijiwa T, Hagiwara M, Mizutani A, Terasawa M, Hidaka H. KN-62, I-[N,O-bis(5-isoquinolinesulfonyl)-N-methyl-l-tyrosyl]-4-phenylpiperazine, a specific inhibitor of Ca2+/calmodulin-dependent protein kinase II. J Biol Chem. 1990;265:4315–4320. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Toullec D, Pianetti P, Coste H, Bellevergue P, Grans-Perret T, Ajakane M, Baudet V, Biossin P, Boursier E, Loriolle F. The bisindolylmaleimide gf 109203X is a potent and selective inhibitor of protein kinase C. J Biol Chem. 1991;266:15771–15781. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Tymianski M, Charlton MP, Carlen PL, Tator CH. Properties of neuroprotective cell-permeant Ca2+ chelator: effects on [Ca2+]i and glutamate neurotoxicity in vivo. J Neurophysiol. 1994;72:1973–1992. doi: 10.1152/jn.1994.72.4.1973. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.VanBerkum MFA, Goodman CS. Targeted disruption of Ca2+-calmodulin signaling in Drosophila growth cones leads to stalls in axon extension and errors in axon guidance. Neuron. 1995;14:43–56. doi: 10.1016/0896-6273(95)90239-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Von Bohlen und Halbach F, Taylor J, Schachner M. Cell type-specific effects of the neural adhesion molecules L1 and NCAM on diverse second messenger systems. Eur J Neurosci. 1992;4:896–909. doi: 10.1111/j.1460-9568.1992.tb00116.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Werth JL, Usachev YM, Thayer SA. Modulation of calcium efflux from cultured rat dorsal root ganglion neurons. J Neurosci. 1996;16:1008–1015. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.16-03-01008.1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Williams EJ, Doherty P, Turner G, Reid AD, Hemperley JJ, Walsh FS. Calcium influx into neurons can solely account for cell contact-dependent neurite outgrowth stimulated by transfected L1. J Cell Biol. 1992;119:883–892. doi: 10.1083/jcb.119.4.883. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Williams EJ, Mittal B, Walsh FS, Doherty P. A Ca2+/calmodulin kinase inhibitor, KN-62, inhibits neurite outgrowth stimulated by CAMs and FGF. Mol Cell Neurosci. 1995;6:69–79. doi: 10.1006/mcne.1995.1007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Zheng J, Felder M, Connor JA, Poo M. Turning of nerve growth cones induced by neurotransmitters. Science. 1994;368:140–144. doi: 10.1038/368140a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Zheng J, Wan J, Poo MM. Essential role of filopodia in chemotropic turning of nerve growth cone induced by a glutamate gradient. J Neurosci. 1996;16:1140–1149. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.16-03-01140.1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Zou DJ, Cline HT. Expression of constitutively active CaMKII in target tissue modifies presynaptic axon arbor growth. Neuron. 1996;16:529–539. doi: 10.1016/s0896-6273(00)80072-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]