Abstract

Temporal pairing of presynaptic activity and serotonin produces enhanced facilitation at Aplysia sensory-motor neuron synapses (pairing-specific facilitation), which may contribute to classical conditioning of the gill and siphon withdrawal reflex. This cellular analog of conditioning is thought to involve Ca2+ priming of the cAMP pathway in the sensory neurons. Consistent with that idea, we have found that pairing-specific facilitation by serotonin is greatly reduced by presynaptic injection of a slow Ca2+ chelator or a specific inhibitor of cAMP-dependent protein kinase and is accompanied by a transient increase in the frequency but by no change in the amplitude of spontaneous, miniature EPSPs. However, like post-tetanic potentiation (PTP) and long-term potentiation (LTP) at these synapses, pairing-specific facilitation is also greatly reduced by postsynaptic injection of a rapid Ca2+ chelator or by postsynaptic hyperpolarization during training, although postsynaptic hyperpolarization has no effect on the increase in frequency or on the amplitude of spontaneous EPSPs. These results suggest that pairing-specific facilitation by serotonin involves Hebbian postsynaptic as well as non-Hebbian presynaptic components that interact in some way, perhaps via retrograde signaling, to specifically enhance evoked, synchronized release of transmitter.

Keywords: Aplysia, pairing-specific facilitation, serotonin, sensory neuron, motor neuron, cell culture, calcium, cAMP-dependent protein kinase

The gill and siphon withdrawal reflex of Aplysia undergoes classical conditioning when a weak tactile stimulus to the siphon [the conditioned stimulus (CS)] occurs just before a noxious stimulus to the tail [the unconditioned stimulus (US)] (Carew et al., 1981, 1983). In a neural analog of the conditioning, presynaptic facilitation of siphon sensory neurons by tail shock is enhanced or amplified when spike activity in the sensory neurons just precedes the tail shock (Hawkins et al., 1983). Because this analog occurs at synapses in the circuit for the reflex with the same temporal parameters as behavioral conditioning, it is thought to contribute to the conditioning (Hawkins et al., 1983; Clark et al., 1994). A similar analog of conditioning occurs at synapses of the tail sensory neurons (Walters and Byrne, 1983). In addition, plasticity also occurs at other sites during conditioning (Colebrook and Lukowiak, 1988; Lukowiak and Colebrook, 1988).

The analog of conditioning in the ganglion has been suggested to be caused by an enhancement of the same mechanisms that contribute to sensitization of the reflex (Hawkins et al., 1983, 1993). Tail stimulation excites interneurons that release several modulatory transmitters including serotonin (5-HT), which produces presynaptic facilitation of the siphon sensory neurons. Serotonin acts in part by stimulating adenylate cyclase to produce cAMP, which acts via cAMP-dependent protein kinase to produce closure of K+ channels, spike broadening, increased Ca2+ influx, and increased transmitter release. Serotonin can also produce facilitation via protein kinase C and a second process that may involve transmitter mobilization (Byrne and Kandel, 1996). Activity-dependent enhancement of the facilitation is thought to be caused in part by priming of the adenylate cyclase by Ca2+ that enters the sensory neurons during the spike activity (Abrams, 1985). Consistent with this hypothesis, serotonin can substitute for tail shock in a neural analog of conditioning at synapses between individual sensory and motor neurons in isolated cell culture. Moreover, this pairing-specific facilitation by serotonin is accompanied by enhancement of both excitability and spike broadening in the sensory neurons, and quantal analysis indicates that it is expressed presynaptically as enhancement of transmitter release (Eliot et al., 1994a).

However, in addition to causing firing of facilitator interneurons, tail stimulation also produces firing of the motor neurons, so that activity-dependent facilitation by tail stimulation could be attributable in part to Hebbian potentiation caused by coincident firing of the sensory and motor neurons. Aplysiasensory-motor neuron synapses use l-glutamate or a similar transmitter that activates NMDA-like receptors (Dale and Kandel, 1993;Trudeau and Castellucci, 1993), and therefore these synapses might have similarities with mammalian synapses that undergo NMDA-dependent Hebbian long-term potentiation (LTP) (Hawkins et al., 1993). Carew et al. (1984) failed to find any evidence of Hebbian potentiation at these synapses by depolarizing or hyperpolarizing the motor neurons. More recently, however, several studies have provided evidence that these synapses undergo Hebbian LTP that is dependent on postsynaptic depolarization and increased Ca2+ (Cui and Walters, 1994; Lin and Glanzman, 1994a,b; Murphy and Glanzman, 1996). A possible explanation for these different results is that the more recent studies were able to control conditions in the synaptic region more effectively. In addition, Bao et al. (1997) and Cui and Walters (1994)have found that post-tetanic potentiation (PTP), which has been thought to be entirely presynaptic, also involves similar postsynaptic mechanisms at these synapses. We have therefore examined the possible contribution of postsynaptic as well as presynaptic mechanisms to pairing-specific facilitation by serotonin at Aplysiasensory-motor neuron synapses in cell culture.

Parts of this paper have been published previously in abstract form (Bao and Hawkins, 1995, 1996).

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Cell culture. The techniques for makingAplysia sensory-motor neuron cocultures have been described previously (Schacher and Proshansky, 1983; Schacher, 1985). In most experiments, a single identified L7 gill motor neuron was isolated from the abdominal ganglion of a juvenile (1–4 gm) Aplysia(Howard Hughes Medical Institute Mariculture Facility, Miami, FL) and cocultured with two mechanosensory neurons isolated from the pleural ganglion of an adult (70–100 gm) animal. In other experiments, an LFS siphon motor neuron was isolated from an adult animal. Results with L7 and LFS motor neurons were similar and have been pooled. The two sensory neurons were placed on opposite sides of the motor neuron near the initial segment of its main axon and 50–100 μm apart (see Fig.1A) to minimize the formation of electrical coupling between them. The cells were plated in culture dishes coated with 0.5 mg/ml poly-l-lysine and were incubated at 18°C for 4–6 d. The culture medium consisted of 50% filtered Aplysiahemolymph and 50% L-15 medium supplemented with 34.6 mmd-glucose and the following salts (in mm): NaCl, 260; CaCl2, 10.1; KCl, 4.6; MgSO4, 25; MgCl2, 28; and NaHCO3, 2.3. Additionally, glutamine (1 mm), penicillin (50 U/ml), and streptomycin (50 μg/ml) were also included in the culture medium. All chemicals were from Sigma (St. Louis, MO) unless otherwise indicated.

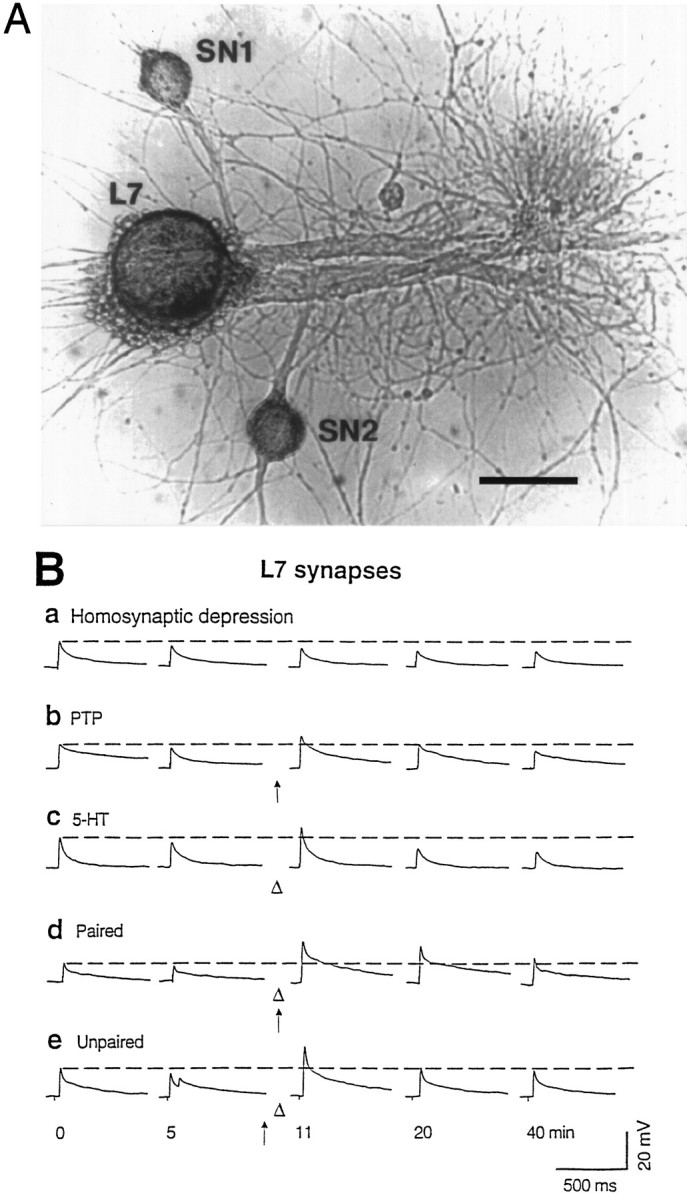

Fig. 1.

The experimental preparation and representative recordings. A, Micrograph of an Aplysiagill motor neuron (L7) isolated from the abdominal ganglion of a juvenile animal and cocultured with two sensory neurons (SN) from the pleural ganglion of an adult animal. Scale bar, 100 μm. B, Original recordings from five representative experiments, showing (a) homosynaptic depression of EPSPs caused by test-alone stimulation of a sensory neuron at ∼5 min intervals, (b) PTP caused by a tetanus (arrow) to the sensory neuron applied at 10 min, (c) short-term facilitation induced by a single puff of 5-HT (open triangle) applied at 10 min, (d) facilitation induced by paired training (5-HT applied ∼0.5 sec after the start of a tetanus given at 10 min), and (e) facilitation induced by unpaired training (5-HT applied 1 min after a tetanus given at 9 min). The recordings inc and d were taken from an experiment in which one sensory neuron received both tetanus and 5-HT and the other only 5-HT. The double EPSPs in e may be caused by double spikes in the sensory neuron.

Electrophysiology. The motor neuron was impaled with a microelectrode (6–15 MΩ) filled with 2.5 m KCl for recording of EPSPs. The electrical signals were amplified with an Axoclamp 2B amplifier (Axon Instruments, Foster City, CA) and recorded on a four-channel tape recorder. A conventional bridge balance circuit was used to inject current through the recording electrode. Because it is not possible to produce PTP while the sensory neuron is impaled with an intracellular electrode (Eliot et al., 1994b), sensory neurons were stimulated with brief (0.1 msec) depolarizing pulses delivered through an extracellular electrode pressed against the soma. The motor neuron was hyperpolarized 30 mV (1.2–3.1 nA; on average, 1.79 ± 0.06 nA) below the resting membrane potential throughout the experiment to minimize spike initiation and to allow accurate measurement of EPSPs. Under these conditions, the minimum amplitude of an EPSP that would initiate a spike was ∼50 mV, which was approximately three times the average amplitude of the initial EPSPs. After 30 min of rest (or, in some experiments, 30 min after the start of presynaptic or postsynaptic injections), EPSPs were evoked from each sensory neuron at ∼5 min intervals for 40 min. On each trial, one sensory neuron was stimulated 1 min after the other. The peak amplitude and initial slope of the EPSPs were measured automatically with an interface to a microcomputer and commercially available software (Hilal Associates, Englewood, NJ).

For PTP experiments, a tetanus (20 Hz for 2 sec) was applied to one of the sensory cells 10 min after the first EPSP in the series (see Fig.1B), and the stimulus intensity was increased 20–30% above that used to evoke the previous EPSP, which was sufficient to produce one-for-one EPSPs during the tetanus; the other sensory cell served as a test-alone control. For experiments on paired training, a single puff of 5-HT (50 μm) was applied in the vicinity of the cells ∼0.5 sec (0.48 ± 0.05 sec) after the start of a tetanus, which was also delivered at “10 min.” The 5-HT did not affect the number of EPSPs produced during the tetanus. For experiments on unpaired training, the tetanus was given at 9 min, 1 min before 5-HT application. At the beginning of each experiment, one of the two sensory neurons was assigned randomly to receive paired or unpaired training; the other sensory neuron served as a 5-HT-alone control. Puffs of 5-HT solution were applied from a low resistance electrode positioned upstream of the cells and connected to a Pico-Injector (pressure, 0.3–0.5 psi; 800 msec in duration) (Medical Systems, Greenvale, NY). The concentration of 5-HT reaching the cells should have been approximately the same as that in the pipette during the puff. Fast green (0.2%), which alone did not affect synaptic transmission, was included in the 5-HT solution to check the delivery and location of the puff and to estimate the time of washout. Quick (<60 sec) washout of 5-HT was achieved by continuous perfusion of the culture dish at a rate of ∼0.5 ml/min with 50% supplemented L-15 medium and 50% artificial seawater (in mm: NaCl, 460; KCl, 11; CaCl2, 10; MgCl2, 27; and MgSO4, 27). All experiments were performed at room temperature (20–23°C) on cultures 4–6 d after plating, by which time sensory-motor neuron synapses become stable (Bank and Schacher, 1992; Zhu et al., 1994).

Intracellular injections. For pressure injections, the tip of the injection electrode was beveled to have a resistance of 3–6 MΩ. The electrode was connected to a Pico-Injector (Medical Systems), and pulses of pressure (800 msec in duration; 0.3–1.4 psi) were delivered at 2 sec intervals for 10–60 sec. The injection electrode was then withdrawn from the cell, and stimulation of the sensory neuron with an extracellular electrode was begun after 30 min of rest. EGTA was first dissolved in KOH, and the pH was adjusted to 7.5 with HCl. Fast green (0.2%) was usually included in the EGTA solution or the control vehicle solution to visually ensure successful injection. The peptide inhibitor of protein kinase A (fragment 6–22 amide, Thr-Tyr-Ala-Asp-Phe-Ile-Ala-Ser-Gly-Arg-Thr-Gly-Arg-Arg-Asn-Ala-Ile-NH2) was dissolved in 0.86 m KCl, and lissamine-rhodamine B (1.7%) (Gurr Diagnostic, High Wycombe, Bucks, England) was included in the solution to monitor the injection. Injections were stopped when the cell body turned pink, and diffusion into the processes was checked with a fluorescence microscope at the end of the experiments. By these criteria, the injections of the protein kinase A inhibitor into the sensory and motor neurons were comparable. In some experiments, both rhodamine and Lucifer yellow were separately injected into the sensory and motor neurons to check for dye coupling between the two cells. For injection of BAPTA (Molecular Probes, Eugene, OR) into the motor neuron, the neuron was impaled with a microelectrode filled with BAPTA dissolved in 2.5 mm KCl, and BAPTA was injected either by iontophoresis (0.5–1 nA; 500 msec; 1 Hz) or diffusion. Similar results were obtained after 20–30 min of iontophoretic application or diffusion. For hyperpolarization of the motor neuron, it was injected with 4 nA of current from ∼20 sec before to 20 sec after the tetanus or 5-HT application. This current injection produced ∼50–100 mV of additional hyperpolarization below the level at which the neuron was held throughout the rest of the experiment, as measured in the soma. The hyperpolarization could have been substantially less at the synaptic region, however.

Spontaneous miniature EPSPs. For these experiments, only a single sensory neuron was cocultured with a motor neuron. Recording of spontaneous miniature EPSPs (mEPSPs) was made at high gain, filtered at 300 Hz (−3 dB), and AC-coupled, whereas evoked EPSPs were recorded at low gain and DC-coupled. Signals were digitized off-line using a personal computer-based Fetchex program (part of the Pclamp package; Axon Instruments) and were analyzed using an Axobasic program. mEPSPs were identified visually based on the following criteria: (1) a rise time of 3–20 msec, (2) a half decay time of at least 5 msec, and (3) a minimum amplitude of 50 μV, which was usually ∼25% greater than the peak-to-peak noise level (Eliot et al., 1994a,b). The frequency and the peak amplitude of mEPSPs were then automatically determined by the computer.

Sensory neuron excitability. Isolated sensory neurons in culture were used for these experiments. Excitability was measured by counting the number of spikes produced by a 500 msec intracellular depolarizing current pulse before and during perfusion with 5-HT (20 μm for 2 min). The current intensity was adjusted to produce one spike before exposure to 5-HT.

Statistics. Most of the data in the text and figures are expressed as mean ± SEM (n represents the number of cultures) and normalized to the first test EPSP (30 min after the impalement), except where otherwise indicated. Data were analyzed statistically by t tests or two-way ANOVAs with one repeated measure (time), and then comparisons were made at each time point by one-way ANOVAs followed by Fisher’s protected least significant difference (PLSD) tests.

RESULTS

We examined EPSPs produced in an Aplysia motor neuron by stimulating individual cocultured sensory neurons. In agreement withEliot et al. (1994a,b), in test-alone controls, the evoked EPSPs underwent homosynaptic depression, i.e., declined over time even when the stimulation interval was as long as 5 min (Fig.1Ba). A single brief tetanic stimulation (20 Hz for 2 sec) of the sensory neuron induced PTP that lasted 15–20 min (Fig. 1Bb). Puffing 5-HT (50 μm) into the vicinity of cells produced facilitation that lasted 5–10 min (Fig. 1Bc). Temporal (0.5 sec forward interstimulus interval) pairing of tetanic stimulation with a single puff of 5-HT produced larger facilitation that lasted >30 min (pairing-specific facilitation) (Fig. 1Bd). Tetanus and 5-HT given 1 min apart (unpaired training) produced only short-lasting facilitation (Fig. 1Be). On average, the facilitation by paired training was significantly larger than the facilitation by unpaired training (for comparison, see Fig. 4), replicating the results of Eliot et al. (1994a). As an additional control, pairing the tetanus with a similar amount of vehicle solution did not produce enhanced facilitation but only a PTP-like potentiation (117.9 ± 7.9% 1 min after the pairing; n = 3).

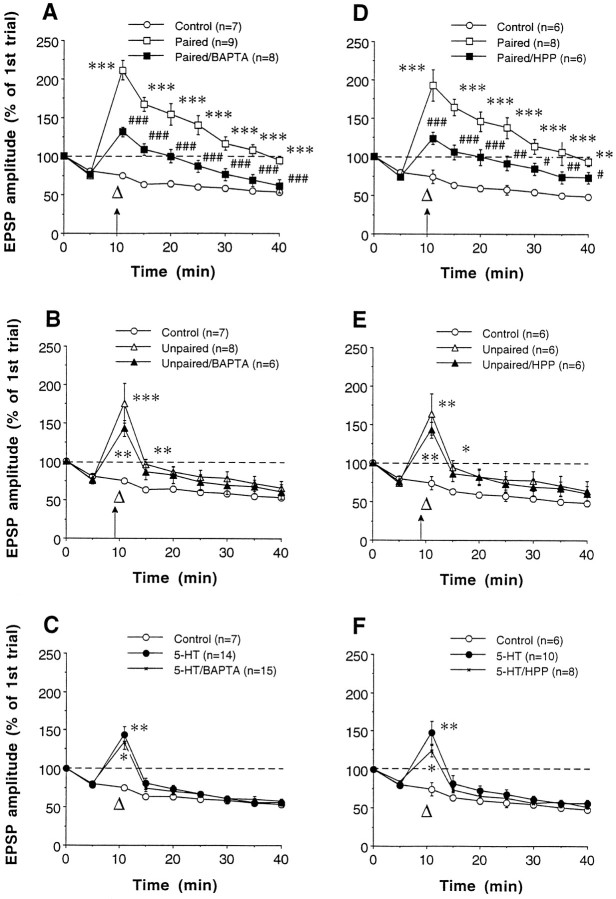

Fig. 4.

Postsynaptic BAPTA or postsynaptic hyperpolarization during training reduce pairing-specific facilitation but not facilitation by unpaired training or by 5-HT.A–C, Effect of postsynaptic BAPTA on facilitation induced by paired presentation of a tetanus (arrow) and 5-HT (large open triangle) (A), by unpaired training (B), and by 5-HT (C). The 5-HT alone and 5-HT/BAPTA results are from the second sensory neuron in the same culture that did not receive tetanic stimulation and are pooled from both paired and unpaired training groups. Average EPSP amplitudes on trial one, 30 min after impalement, were 14.3 ± 1.5 mV (control), 18.2 ± 2.0 mV (paired), 14.9 ± 1.5 mV (paired/BAPTA), 13.3 ± 1.5 mV (unpaired), 21.5 ± 3.3 mV (unpaired/BAPTA), 20.1 ± 1.9 mV (5-HT), and 20.7 ± 2.9 mV (5-HT/BAPTA), not significantly different [F(6,66) = 1.68;p = 0.1417]. D–F, Effect of postsynaptic hyperpolarization (HPP) on facilitation by paired training (D), by unpaired training (E), and by 5-HT (F). The average amplitudes of EPSPs 30 min after impalement were 14.1 ± 1.9 mV (control), 16.0 ± 3.0 mV (paired), 15.9 ± 2.6 mV (paired/HPP), 11.7 ± 2.4 mV (unpaired), 18.7 ± 2.3 mV (unpaired/HPP), 18.5 ± 2.8 mV (5-HT), and 19.6 ± 3.1 mV (5-HT/HPP), not significantly different [F(6,48) = 0.96; p = 0.4628].

Role of presynaptic Ca2+

Pairing-specific facilitation by serotonin is thought to be attributable in part to priming of adenylate cyclase by Ca2+ that enters the sensory neurons during the spike activity (Abrams, 1985; Eliot et al., 1994a). To investigate the contribution of presynaptic Ca2+ to pairing-specific facilitation more directly, we pressure injected the sensory neuron with EGTA, a Ca2+ chelator with slow kinetics that buffers residual Ca2+ without affecting transmitter release (Adler et al., 1991). Presynaptic EGTA reduces potentiation by tetanic stimulation (PTP) at these synapses (Bao et al., 1997). Presynaptic EGTA (50 mm in the electrode) also substantially reduced pairing-specific facilitation to a level comparable with that produced by 5-HT alone (Fig.2) but did not significantly affect baseline EPSPs (Fig. 2, control) or the area under the summed EPSPs during the pairing (t10 = 1.25, not significant). Overall, there were significant differences between the four groups in Figure 2 [F(3,32) = 15.63 for treatment; p = 0.0001; F(24,256)= 9.25 for treatment × time; p = 0.0001], and there were significant differences between the paired group (paired/control) and the paired group with EGTA injection (paired/EGTA) at each test from 5 to 30 min after training.

Fig. 2.

Presynaptic EGTA reduces pairing-specific facilitation. Paired training is indicated by an arrow(tetanus) and a large open triangle (5-HT). In both control (open circles) and paired/control (open squares) groups, sensory neurons received injection of vehicle solution. The 5-HT-alone (small open triangles) data were obtained from the second sensory neurons in the cultures that did not receive any injection but only 5-HT puffs. For this and subsequent figures, *p < 0.05, **p < 0.01, and ***p < 0.001 versus control; #p < 0.05, ##p < 0.01, and ###p < 0.001 versus paired/control by Fisher’s PLSD tests. The average amplitudes of EPSPs on trial one, 30 min after impalement, were 12.7 ± 2.1 mV (control), 22.5 ± 6.5 mV (paired/control), 12.2 ± 2.5 mV (paired/EGTA), and 19.1 ± 3.5 mV (5-HT), not significantly different from each other [F(3,35) = 1.39; p = 0.2625].

In agreement with Clark et al. (1994), we found that there was an increase in the initial slope of evoked EPSPs that paralleled the increase in amplitude of EPSPs after paired training [F(8,55) = 5.25; p < 0.001;p < 0.05 at each test from 1 to 15 min after training], suggesting that pairing-specific facilitation may involve some mechanism in addition to spike-broadening in the sensory neurons (Hochner et al., 1986). Furthermore, presynaptic injection of EGTA reduced the increase in slope of the EPSPs in parallel with its effect on their amplitude (p < 0.05 at each test from 5 to 20 min after training; n = 4). These results suggest that both spike broadening and any additional mechanism of pairing-specific facilitation require an increase in presynaptic Ca2+.

Role of presynaptic cAMP-dependent protein kinase

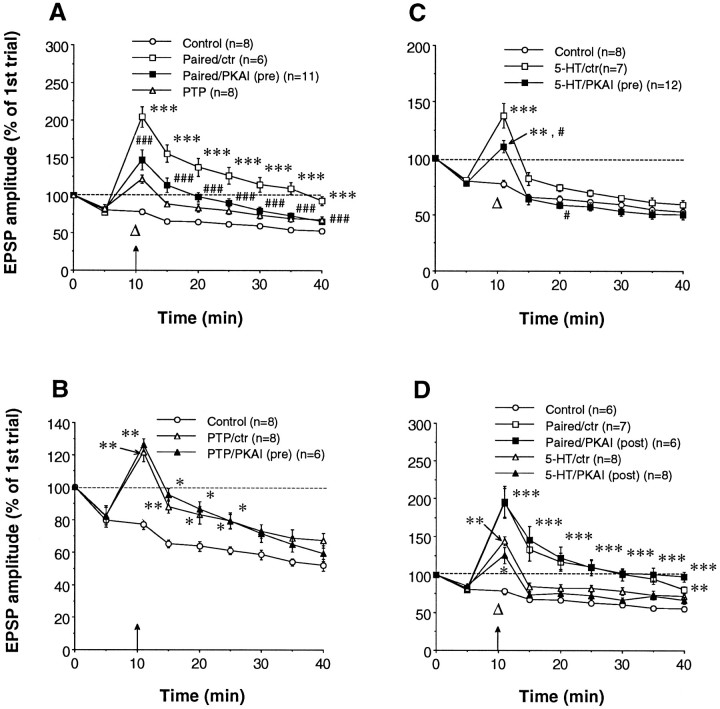

Several lines of evidence suggest that pairing-specific facilitation involves cAMP-mediated processes in the sensory neuron (Abrams, 1985; Hawkins et al., 1993; Eliot et al., 1994a). To test directly whether presynaptic cAMP-dependent protein kinase (PKA) is involved in pairing-specific facilitation, we pressure injected a specific peptide inhibitor of PKA (PKAI6–22) (Cheng et al., 1985) into the sensory neuron. Presynaptic injection of PKAI6–22 (500 μm in the electrode) reduced pairing-specific facilitation to a level comparable with PTP, whereas sensory neurons receiving vehicle injection exhibited normal pairing-specific facilitation (Fig.3A). PKAI6–22injected into the sensory neuron had no effect on basal synaptic transmission (Fig. 3A, control). Overall, there were significant differences between the seven groups in Figure3A–C [F(6,51) = 21.12 for treatment; p = 0.0001; F(48,408)= 9.83 for treatment × time; p = 0.0001], and there were significant differences between the paired/control group and the paired/PKAI(pre) group at each test after training.

Fig. 3.

Presynaptic but not postsynaptic injection of a protein kinase A inhibitor (PKAI6–22) reduces pairing-specific facilitation. A, Presynaptic PKAI6–22 [PKAI(pre)] significantly reduced the facilitation induced by paired training indicated by anarrow (tetanus) and a large open triangle(5-HT). For both control and paired/control groups, sensory neurons received injection of vehicle solution. PTP by tetanus alone is plotted here for comparison (same data plotted as PTP/ctr in B).B, Presynaptic PKAI6–22 had no effect on PTP. The control group is replotted for comparison. C, Presynaptic PKAI6–22 reduced 5-HT-induced facilitation; #p < 0.05 versus 5-HT. The average amplitudes of EPSPs on trial one, 30 min after impalement, in A–Cwere 14.6 ± 2.6 mV (control), 15.8 ± 4.9 mV (paired/control), 24.0 ± 3.3 mV [paired/PKAI(pre)], 12.3 ± 2.7 mV (PTP/control), 18.2 ± 5.2 mV [PTP/PKAI(pre)], 20.4 ± 2.8 mV (5-HT/control), and 19.9 ± 6.9 mV [5-HT/PKAI(pre)], not significantly different [F(6,51) = 2.15; p = 0.0638]. D, Postsynaptic injection of PKAI6–22 [PKAI(post)] did not significantly affect pairing- or 5-HT-induced facilitation. For control, paired/control, and 5-HT/control groups, the motor neurons were injected with vehicle solution. EPSPs 30 min after impalement had amplitudes of 15.4 ± 2.5 mV (control), 12.8 ± 1.3 mV (paired/control), 19.2 ± 4.6 mV [paired/PKAI(post)], 21.4 ± 4.7 mV (5-HT/control) and 17.4 ± 3.9 mV [5-HT/PKAI(post)], not significantly different [F(4,32) = 0.83; p = 0.5146].

PKAI6–22 injected into the sensory neuron had essentially no effect on PTP (Fig. 3B). However, injection of PKAI6–22 into the sensory neuron did reduce short-term facilitation by serotonin (Fig. 3C). There were significant differences between the 5-HT/control and the 5-HT/PKAI(pre) groups 1 and 10 min after training. In separate experiments, PKAI6–22 injected into a sensory neuron also significantly reduced the increase in sensory neuron excitability by 5-HT (vehicle, 15 ± 2 spikes; n = 3; PKAI6–22, 3.2 ± 0.9 spikes; n = 5;t6 = 6.22; p = 0.0008). These effects of 5-HT are thought to be mediated at least in part by the cAMP-PKA pathway, confirming that PKAI6–22 inhibited the activity of PKA in the sensory neuron. Synaptic facilitation by 5-HT at depressed synapses is also thought to be mediated in part by protein kinase C (Byrne and Kandel, 1996), which could account for the remaining facilitation 1 min after 5-HT (Fig. 3C).

By contrast, injection of PKAI6–22 into thepostsynaptic cell did not have any appreciable effect on pairing-specific facilitation or 5-HT-induced short-term facilitation (Fig. 3D), suggesting that the induction of pairing-specific facilitation probably does not require cAMP-PKA in the postsynaptic neuron. Overall, there were significant differences between the five groups in Figure 3D [F(4,30) = 12.91 for treatment; p = 0.0001;F(32,240) = 8.96 for treatment × time;p = 0.0001], but there were no significant differences between the paired/control and paired/PKAI(post) groups or the 5-HT/control and 5-HT/PKAI(post) groups.

Taken together, the results of these experiments and the EGTA injection experiments suggest that 5-HT-induced facilitation (cAMP-PKA pathway) and tetanus-induced potentiation (Ca2+-? pathway) are independent presynaptic processes and that both cAMP and Ca2+ must be elevated in the presynaptic neuron to produce pairing-specific facilitation. Moreover, the fact that explicitly unpaired training with the tetanus and 5-HT applied 1 min apart did not induce long-lasting facilitation indicates that presynaptic Ca2+ and cAMP act synergistically and are not simply additive.

Role of postsynaptic Ca2+ and membrane potential

Both LTP and PTP at Aplysia sensory-motor neuron synapses in cell culture are dependent on postsynaptic depolarization and Ca2+ elevation (Lin and Glanzman, 1994a,b; Bao et al., 1997). We therefore examined the possible involvement of these postsynaptic events in pairing-specific facilitation. Postsynaptic injection of BAPTA (200 mm in the electrode), a Ca2+ chelator with fast kinetics (Adler et al., 1991), greatly reduced facilitation by paired training but did not significantly affect that by unpaired training or by 5-HT (Fig.4A–C). Overall, there were significant differences between the seven groups in Figure4A–C [F(6,60) = 14.76 for treatment; p = 0.0001; F(48,480)= 8.32 for treatment × time; p = 0.0001]. Replicating the results of Eliot et al. (1994a), there were significant differences between paired and unpaired training at each test from 5 to 30 min after training (p < 0.01 in each case). There were also significant differences between the paired and paired/BAPTA groups at each test after training, but there were no significant differences between the unpaired and unpaired/BAPTA or between the 5-HT and 5-HT/BAPTA groups.

Similarly, strong hyperpolarization (4 nA) of the motor neuron during training significantly reduced facilitation produced by pairing but left unaffected facilitation by unpaired training or by 5-HT (Fig.4D–F). On average, the motor neuron was hyperpolarized longer during unpaired training than during paired training, but there was overlap, and the results did not correlate with duration of hyperpolarization. Overall, there were significant differences between the seven groups in Figure4D–F [F(6,42) = 11.49 for treatment; p = 0.0001; F(48,336)= 8.00 for treatment × time; p = 0.0001]. Again, there were significant differences between paired and unpaired training at each test from 1 to 30 min after training (p< 0.01 in each case). There were also significant differences between the paired and paired/HPP groups at each test after training, but there were no significant differences between the unpaired and unpaired/HPP or between the 5-HT and 5-HT/HPP groups.

Previous control experiments indicate that postsynaptic BAPTA or hyperpolarization does not affect the presynaptic neuron through gap junctions or electrical coupling (Bao et al., 1997). As additional evidence, we found that either rhodamine or Lucifer yellow injected into the sensory or motor neuron did not appear in the uninjected cell (data not shown), suggesting that there is also minimal dye coupling between the sensory and motor neurons. These results thus suggest that the induction of pairing-specific facilitation involves depolarization and an increase in Ca2+ in the postsynaptic neuron.

Postsynaptic hyperpolarization during paired training does not affect spontaneous miniature EPSPs

To try to determine which aspect of synaptic transmission is affected by these postsynaptic manipulations, we analyzed the effect of postsynaptic hyperpolarization on both evoked EPSPs and spontaneous mEPSPs during paired training. Consistent with the results of Eliot et al. (1994a), paired training of the sensory neuron that induced a long-lasting facilitation of evoked EPSPs also produced a transient increase in the frequency of mEPSPs (Fig.5A,B) but did not significantly increase the amplitude of mEPSPs (Fig.5C,E). Although there were too few spontaneous mEPSPs to detect small changes in their amplitude in any individual experiment (Fig. 5C), the results were very consistent between experiments, so that fairly small changes could have been detected in the average results (Fig. 5E). Whereas paired training produced a significant increase in the amplitude of evoked EPSPs (t4 = 8.52; p < 0.001), there was no significant change in the amplitude of spontaneous mEPSPs during the same time period. These results suggest that pairing-specific facilitation involves a presynaptic increase in transmitter release.

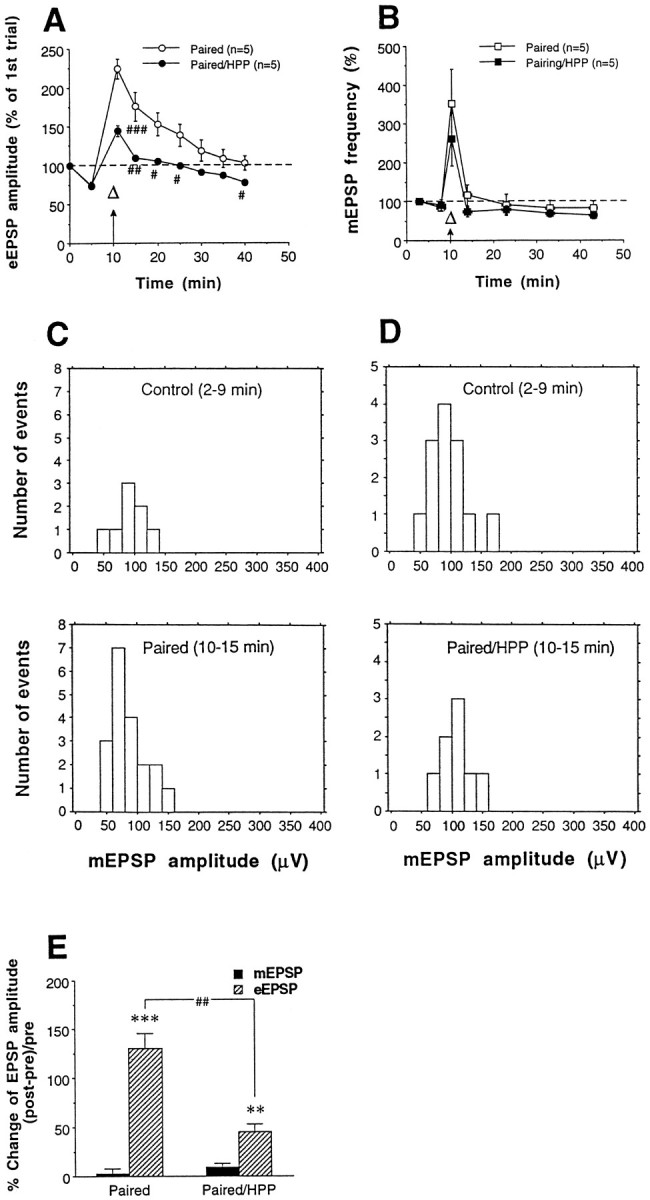

Fig. 5.

Effects of paired training and postsynaptic hyperpolarization during paired training on spontaneous release.A, B, HPP reduced pairing-induced facilitation of evoked EPSPs (eEPSPs) (A) but not the pairing-induced increase in the frequency of spontaneous mEPSPs(B). Paired training is indicated by a combinedarrow (tetanus) and open triangle (5-HT).A, EPSPs on trial one, 30 min after impalement, had amplitudes of 22.2 ± 3.9 mV (paired) and 27.0 ± 3.9 mV (paired/HPP), not significantly different (t8 = 0.87; p = 0.4089).B, The average frequency of mEPSPs 30 min after impalement was 0.059 ± 0.013 and 0.048 ± 0.005 Hz for paired and paired/HPP groups, respectively, not significantly different (t8 = 0.76; p = 0.4683).C, Amplitude distribution of mEPSPs at a representative synapse before (2–9 min) and after (10–15 min) paired training. Paired training did not increase the amplitude of mEPSPs. In this experiment, the mean amplitudes of mEPSPs before and after the training were 88.1 ± 7.6 μV (n = 8) and 84.8 ± 6.4 μV (n = 19), respectively, not significantly different (t25 = 0.30; p= 0.7658). D, Postsynaptic hyperpolarization during paired training also did not affect mEPSP amplitude. In this experiment, the mean amplitudes of mEPSPs before and after the training were 95.9 ± 8.1 μV (n = 13) and 105.4 ± 9.1 μV (n = 8), respectively, not significantly different (t19 = 0.76;p = 0.4552). E, Summary of effects of paired training and postsynaptic hyperpolarization during pairing (paired/HPP) on amplitudes of eEPSPs and mEPSPs. For eEPSPs, “pre” and “post” were defined as the average of EPSP amplitudes at 0 and 5 min and at 11 and 15 min, respectively; for mEPSPs, “pre” and “post” were defined as the average amplitude of mEPSPs during 2–9 min and 10–15 min, respectively; **p < 0.01 and ***p < 0.001 versus pre; ##p < 0.01 versus paired byt tests.

Replicating the results shown in Figure 4D, strong hyperpolarization (4 nA) of the postsynaptic motor neuron during paired training reduced pairing-induced facilitation of evoked EPSPs (Fig.5A). Overall, there was a significant difference between paired training and paired training during hyperpolarization (paired/HPP) [F(1,8) = 10.98 for treatment;p = 0.0106; F(8,64) = 12.12 for treatment × time; p = 0.0001]. However, hyperpolarization during paired training did not significantly affect the increase in frequency of mEPSPs (Fig. 5B) or the amplitude of mEPSPs (Fig. 5D,E), although it did significantly reduce the increase in amplitude of evoked EPSPs during the same time period (t8 = 4.92; p < 0.0012). These results suggest that postsynaptic hyperpolarization during paired training affects some aspect of transmitter release that is specific to evoked release.

DISCUSSION

Mechanisms contributing to pairing-specific facilitation by serotonin

Our results support the hypothesis that pairing-specific facilitation at Aplysia sensory-motor neuron synapses involves Ca2+ priming of the cAMP pathway in the presynaptic neurons (Abrams, 1985; Hawkins et al., 1993; Eliot et al., 1994a). In agreement with Eliot et al. (1994a), we found that paired training produced no change in the amplitude of spontaneous mEPSPs, suggesting that pairing-specific facilitation is expressed presynaptically as an increase in transmitter release (Fig. 5). Moreover, presynaptic injection of the Ca2+ chelator EGTA (Fig. 2) or an inhibitor of PKA (Fig. 3A) reduced pairing-specific facilitation to approximately the level of facilitation by 5-HT alone or PTP alone, respectively. However, postsynaptic injection of the Ca2+ chelator BAPTA or postsynaptic hyperpolarization during training also greatly reduced facilitation by paired training but had little effect on facilitation by unpaired training (Fig. 4), suggesting that postsynaptic mechanisms also contribute to pairing-specific facilitation. Long-term (24 hr) pairing-specific facilitation produced by four training trials (but not one training trial) is similarly reduced by postsynaptic hyperpolarization during training (Schacher et al., 1997).

Because most of the enhancement of facilitation by pairing was eliminated by either presynaptic (Figs. 2, 3A) or postsynaptic (Fig. 4) manipulations, these two types of mechanisms are evidently not additive but interact in some way. One possibility is that Ca2+ elevation in the postsynaptic neuron leads to formation of a retrograde messenger that then interacts with Ca2+ or cAMP in the presynaptic neuron to enhance some aspect of transmitter release. Eliot et al. (1994a) found that paired training produced a transient increase in the frequency of spontaneous mEPSPs, but that unpaired training also produced a similar increase. Consistent with that result, we found that pairing-specific facilitation was accompanied by an increase in the frequency of spontaneous mEPSPs, but that increase did not last as long as the facilitation of evoked EPSPs (Fig.5A,B). Moreover, postsynaptic hyperpolarization reduced the facilitation of evoked EPSPs but did not significantly affect the frequency or the amplitude of spontaneous mEPSPs (Fig. 5). These results therefore suggest that the putative retrograde messenger does not affect spontaneous release but rather acts to specifically enhance evoked, synchronous release. Similar mechanisms are thought to contribute to PTP at these synapses (Bao et al., 1997), suggesting that pairing-specific facilitation and PTP may affect the same or similar aspects of transmitter release.

Mechanisms contributing to learning

Both pairing-specific facilitation by serotonin and Hebbian LTP could contribute to activity-dependent facilitation by tail stimulation, which in turn is thought to contribute to classical conditioning of the gill and siphon withdrawal reflex (Hawkins et al., 1983; Clark et al., 1994) and to site-specific sensitization of the tail withdrawal reflex (Walters, 1987; Cui and Walters, 1995). Murphy and Glanzman (1996) recently reported that activity-dependent facilitation by tail stimulation is blocked by postsynaptic injection of BAPTA, and they suggested that the facilitation may be caused primarily by Hebbian LTP. Surprisingly, our results indicate that pairing-specific facilitation by 5-HT is also blocked by postsynaptic BAPTA (Fig. 4A), so that BAPTA injection does not discriminate between these two mechanisms, and their relative contributions to activity-dependent facilitation by tail stimulation remain unknown. Moreover, Abrams and Galun (1995) found that activity-dependent facilitation by tail stimulation, like pairing-specific facilitation by serotonin (Fig. 3A), is also blocked by presynaptic injection of an inhibitor of cAMP-dependent protein kinase. These results indicate that Hebbian postsynaptic and activity-dependent presynaptic mechanisms may both be required for activity-dependent facilitation by tail stimulation, and therefore attempting to determine their relative contributions may not be the correct way of thinking about the problem. Rather, as our data suggest,Aplysia sensory-motor neuron synapses may have a single hybrid mechanism with Hebbian postsynaptic and activity-dependent presynaptic components. Such a hybrid mechanism might combine the advantages of activity-dependent presynaptic facilitation by a modulatory transmitter, which is well suited for learning which stimuli occur just before a motivationally significant event, and Hebbian potentiation, which is synapse-specific and therefore might provide a mechanism for the response specificity of classical conditioning (Hawkins et al., 1989). A hybrid mechanism might also account for the temporal specificity of conditioning (Clark et al., 1994), whereas a purely Hebbian mechanism would not (Lin and Glanzman, 1997).

Recent data suggest that long-term potentiation in the CA1 region of hippocampus, which has been thought to be purely Hebbian, also involves a similar (but not identical) hybrid combination of Hebbian postsynaptic and activity-dependent presynaptic components (Hawkins et al., 1993; Zhuo et al., 1993; Arancio et al., 1996). These results support the idea that such hybrid mechanisms may be more widespread. Thus, the elementary mechanisms of synaptic plasticity that have been identified previously may form an alphabet of basic components that are combined in various ways in the nervous system, presumably permitting a greater range of functional synaptic modifications (Hawkins and Kandel, 1984).

Footnotes

This work was supported by National Institute of Mental Health Grant MH26212 and a grant from the Howard Hughes Medical Institute. A long-term fellowship from the Human Frontier Science Program Organization to J.-X.B. is gratefully acknowledged. We thank H. Ayers and I. Trumpet for typing this manuscript.

Correspondence should be addressed to Dr. Robert D. Hawkins, Center for Neurobiology and Behavior, Columbia University, 722 West 168th Street, New York, NY 10032.

REFERENCES

- 1.Abrams TW. Activity-dependent presynaptic facilitation: an associative mechanism in Aplysia. Cell Mol Neurobiol. 1985;5:123–145. doi: 10.1007/BF00711089. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Abrams TW, Galun JE. Role of adenylyl cyclase and cAMP in associative facilitation at sensory neuron synapses in Aplysia. Soc Neurosci Abstr. 1995;21:1023. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Adler EM, Augustine GJ, Duffy SN, Charlton MP. Alien intracellular calcium chelators attenuate neurotransmitter release at squid giant synapse. J Neurosci. 1991;11:1496–1507. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.11-06-01496.1991. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Arancio O, Kiebler M, Lee LJ, Lev-Ram V, Tsien RY, Kandel ER, Hawkins RD. Nitric oxide acts directly in the presynaptic neuron to produce long-term potentiation in cultured hippocampal neurons. Cell. 1996;87:1025–1035. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)81797-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Bank M, Schacher S. Segregation of presynaptic inputs on an identified target neuron in vitro: structural remodeling visualized over time. J Neurosci. 1992;12:2960–2972. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.12-08-02960.1992. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Bao J-X, Hawkins RD. A postsynaptic contribution to posttetanic potentiation (PTP) and pairing-specific facilitation at Aplysia sensory-motor synapses in cell culture. Soc Neurosci Abstr. 1995;21:1024. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Bao J-X, Hawkins RD. Posttetanic potentiation and activity-dependent facilitation at Aplysia cultured sensory-motor neuron synapses involve both pre- and postsynaptic mechanisms. Soc Neurosci Abstr. 1996;22:695. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Bao J-X, Kandel ER, Hawkins RD. Involvement of pre- and postsynaptic mechanisms in posttetanic potentiation at Aplysia synapses. Science. 1997;275:969–973. doi: 10.1126/science.275.5302.969. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Byrne JH, Kandel ER. Presynaptic facilitation revisited: state and time dependence. J Neurosci. 1996;16:425–435. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.16-02-00425.1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Carew TJ, Walters ET, Kandel ER. Classical conditioning in a simple withdrawal reflex in Aplysia californica. J Neurosci. 1981;1:1426–1437. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.01-12-01426.1981. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Carew TJ, Hawkins RD, Kandel ER. Differential classical conditioning of a defensive withdrawal reflex in Aplysia californica. Science. 1983;219:397–400. doi: 10.1126/science.6681571. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Carew TJ, Hawkins RD, Abrams TW, Kandel ER. A test of Hebb’s postulate at identified synapses which mediate classical conditioning in Aplysia. J Neurosci. 1984;4:1217–1224. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.04-05-01217.1984. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Cheng HC, van Pattern SM, Smith AJ, Walsh DA. An active twenty-amino acid-residue peptide derived from the inhibitor protein of the cyclic AMP-dependent protein kinase. Biochem J. 1985;231:655–661. doi: 10.1042/bj2310655. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Clark GA, Hawkins RD, Kandel ER. Activity-dependent enhancement of presynaptic facilitation provides a cellular mechanism for the temporal specificity of classical conditioning in Aplysia. Learn Mem. 1994;1:243–257. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Colebrook E, Lukowiak K. Learning by the Aplysia model system: lack of correlation between gill and gill motor neurone responses. J Exp Biol. 1988;135:411–429. doi: 10.1242/jeb.140.1.273. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Cui M, Walters ET. Homosynaptic LTP and PTP of sensorimotor synapses mediating the tail withdrawal reflex in Aplysia are reduced by postsynaptic hyperpolarization. Soc Neurosci Abstr. 1994;20:1071. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Cui M, Walters ET. Long-term potentiation of Aplysia sensory neuron synapses after tail pinch: effects of postsynaptic hyperpolarization and BAPTA injection. Soc Neurosci Abstr. 1995;21:1456. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Dale N, Kandel ER. l-Glutamate may be the fast excitatory transmitter of Aplysia sensory neurons. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1993;90:7163–7167. doi: 10.1073/pnas.90.15.7163. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Eliot LS, Hawkins RD, Kandel ER, Schacher S. Pairing-specific, activity-dependent presynaptic facilitation of Aplysia sensory-motor neuron synapses in isolated cell culture. J Neurosci. 1994a;14:368–383. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.14-01-00368.1994. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Eliot LS, Kandel ER, Hawkins RD. Modulation of spontaneous transmitter release during depression and posttetanic potentiation of Aplysia sensory-motor neuron synapses isolated in culture. J Neurosci. 1994b;14:3280–3292. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.14-05-03280.1994. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Hawkins RD, Kandel ER. Is there a cell biological alphabet for simple forms of learning? Psychol Rev. 1984;91:375–391. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Hawkins RD, Abrams TW, Carew TJ, Kandel ER. A cellular mechanism of classical conditioning in Aplysia: activity-dependent amplification of presynaptic facilitation. Science. 1983;219:400–405. doi: 10.1126/science.6294833. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Hawkins RD, Lalevic N, Clark GA, Kandel ER. Classical conditioning of the Aplysia siphon-withdrawal reflex exhibits response specificity. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1989;86:7620–7624. doi: 10.1073/pnas.86.19.7620. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Hawkins RD, Kandel ER, Siegelbaum SA. Learning to modulate transmitter release: themes and variations in synaptic plasticity. Annu Rev Neurosci. 1993;16:625–665. doi: 10.1146/annurev.ne.16.030193.003205. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Hochner B, Klein M, Schacher S, Kandel ER. Additional component in the cellular mechanism of presynaptic facilitation contributes to behavioral dishabituation in Aplysia. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1986;83:8794–8798. doi: 10.1073/pnas.83.22.8794. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Lin XY, Glanzman DL. Long-term potentiation of Aplysia sensorimotor synapses in cell culture: regulation by postsynaptic voltage. Proc R Soc Lond [Biol] 1994a;255:113–118. doi: 10.1098/rspb.1994.0016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Lin XY, Glanzman DL. Hebbian induction of long-term potentiation of Aplysia sensorimotor synapses: partial requirement for activation of a NMDA-related receptor. Proc R Soc Lond [Biol] 1994b;255:215–221. doi: 10.1098/rspb.1994.0031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Lin XY, Glanzman DL. Effect of interstimulus interval on pairing-induced LTP of Aplysia sensorimotor synapses in cell culture. J Neurophysiol. 1997;77:667–674. doi: 10.1152/jn.1997.77.2.667. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Lukowiak K, Colebrook E. Classical conditioning alters the efficacy of identified gill motor neurons in producing gill withdrawal movement in Aplysia. J Exp Biol. 1988;140:273–285. doi: 10.1242/jeb.140.1.273. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Murphy GG, Glanzman DL. Enhancement of sensorimotor connections by conditioning-related stimulation in Aplysia depends on postsynaptic Ca2+. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1996;93:9931–9936. doi: 10.1073/pnas.93.18.9931. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Schacher S. Differential synapse formation and neurite outgrowth at two branches of the metacerebral cell of Aplysia in dissociated cell culture. J Neurosci. 1985;5:2028–2034. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.05-08-02028.1985. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Schacher S, Proshansky E. Neurite regeneration by Aplysia neurons in dissociated cell culture: modulation by Aplysia hemolymph and the presence of the initial axonal segment. J Neurosci. 1983;3:2403–2413. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.03-12-02403.1983. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Schacher S, Wu F, Sun ZY. Pathway-specific synaptic plasticity: activity-dependent enhancement and suppression of long-term heterosynaptic facilitation at converging inputs on a single target. J Neurosci. 1997;17:597–606. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.17-02-00597.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Trudeau L-E, Castellucci VF. Excitatory amino acid neurotransmitter at sensory-motor and interneuronal synapses of Aplysia californica. J Neurophysiol. 1993;70:1221–1230. doi: 10.1152/jn.1993.70.3.1221. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Walters ET. Multiple sensory neuronal correlates of site-specific sensitization in Aplysia. J Neurosci. 1987;7:408–417. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.07-02-00408.1987. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Walters ET, Byrne JH. Associative conditioning of single sensory neurons suggests a cellular mechanism for learning. Science. 1983;219:405–408. doi: 10.1126/science.6294834. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Zhu H, Wu F, Schacher S. Aplysia cell adhesion molecules and serotonin regulate sensory cell–motor cell interactions during early stages of synapse formation in vitro. J Neurosci. 1994;14:6886–6900. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.14-11-06886.1994. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Zhuo M, Small SA, Kandel ER, Hawkins RD. Nitric oxide and carbon monoxide produce activity-dependent long-term synaptic enhancement in the hippocampus. Science. 1993;260:1946–1950. doi: 10.1126/science.8100368. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]