Anatomical phenotypes of maize nodal roots vary significantly across nodes and nitrogen levels, which affects the evaluation of genotypic variation, allometry, and adaption among field-grown hybrid and inbred lines.

Keywords: Axial root anatomy, genotypic variation, maize (Zea mays L.), nitrogen use efficiency, node, phenotyping, plasticity

Abstract

Root phenotypes that improve nitrogen acquisition are avenues for crop improvement. Root anatomy affects resource capture, metabolic cost, hydraulic conductance, anchorage, and soil penetration. Cereal root phenotyping has centered on primary, seminal, and early nodal roots, yet critical nitrogen uptake occurs when the nodal root system is well developed. This study examined root anatomy across nodes in field-grown maize (Zea mays L.) hybrid and inbred lines under high and low nitrogen regimes. Genotypes with high nitrogen use efficiency (NUE) had larger root diameter and less cortical aerenchyma across nodes under stress than genotypes with lower NUE. Anatomical phenes displayed slightly hyperallometric relationships to shoot biomass. Anatomical plasticity varied across genotypes; most genotypes decreased root diameter under stress when averaged across nodes. Cortex, stele, total metaxylem vessel areas, and cortical cell file and metaxylem vessel numbers scaled strongly with root diameter across nodes. Within nodes, metaxylem vessel size and cortical cell size were correlated, and root anatomical phenotypes in the first and second nodes were not representative of subsequent nodes. Node, genotype, and nitrogen treatment affect root anatomy. Understanding nodal variation in root phenes will enable the development of plants that are adapted to low nitrogen conditions.

Introduction

Maize (Zea mays L.) is a primary global crop, with >1 billion t produced annually for food, fuel, and industrial uses. In intensive maize production, nitrogen (N) fertilizer is generally the most expensive input, costing ~US$60 billion for a total 140 million t of N produced globally in 2016 (FAO, 2018). However, only 33% of applied N is converted to grain yield, with the remainder lost as harmful pollution in the form of surface runoff, volatilized ammonia, or nitrogen oxide emissions, or leached beyond the root zone as nitrate, contaminating waterways and creating eutrophic ‘dead zones’ which require costly remediation (Hirel et al., 2011; Dhital and Raun, 2016). Conversely, low soil N is one of the primary yield constraints in low-input systems in Latin America and sub-Saharan Africa, where maize is essential for food security (Gibbon et al., 2007).

Improving nitrogen use efficiency (NUE) in maize is a sustainable strategy for boosting yields in both large commercial operations and food-insecure regions. NUE is defined as the grain weight produced per unit of soil N, as a result of N uptake (NUpE) and utilization (NUtE) processes, including absorption, assimilation, and remobilization (Moll et al., 1982; Xu et al., 2012). Given the greater potential for agronomic and genetic improvement in NUpE, ‘ideotype’ breeding could improve NUE (Donald, 1968; Lea and Azevedo, 2006; Fischer et al., 2014). Root system ideotypes, including anatomical, architectural, and physiological phenes, have been proposed for optimizing N capture in maize (Clarke and McCaig, 1993; Lynch, 2013; Fischer et al., 2014; Schmidt and Gaudin, 2017). The term ‘phene’ refers specifically to elements of the phenotype, which may be expressed at varying levels (e.g. root hair length of a certain class of roots), whereas ‘trait’ is used more generally to indicate measurements which may or may not be biologically meaningful, such as field estimates of root system ‘size’ or depth (York et al., 2013).

To evaluate genotypic variation and the utility of root phenes, phenotyping methods have been developed, ranging from germination paper to artificial media to field excavation (reviewed in Meister et al., 2014). Studies have largely focused on primary, seminal, and early nodal roots in maize, which develop by the four-leaf stage, within 2 weeks depending on growth conditions. Typically, maize plants develop up to six crown root nodes belowground, with up to three additional brace root nodes emerging aboveground (Hoppe et al., 1986; Hochholdinger et al., 2004). Critical N uptake in field-grown maize occurs during the development of these later nodes, with maximum uptake occurring at the 10- to 14-leaf stage, beginning ~4 weeks after planting (DeBruin et al., 2017).

Several studies have evaluated anatomical phenotypes of the second root node of mature plants, due to initial screening of these genotypes occurring at earlier growth stages in the greenhouse (Burton et al., 2012b; Chimungu et al., 2014a, b; Saengwilai et al., 2014). However, anatomical and architectural phenes, including root number, diameter, branching, angle, and consequently, root depth, may vary by node (Yamazaki and Kaeriyama, 1982; Girardin et al., 1987; Demotes-Mainard and Pellerin, 1992; Stamp and Kiel, 1992; Jordan et al., 1993; Araki et al., 2000; Burton et al., 2012a, 2013; York and Lynch, 2015). There is a clear need to characterize root anatomical phenes across nodes and N levels to determine their impact on NUE.

Phenotypic diversity in both root anatomy and architecture was characterized among Zea species (Burton et al., 2013), but not under stress conditions. York et al. (2015) studied 16 commercially successful hybrids across different planting densities and N levels, and found that changes in nodal root architecture and anatomy, related to cultivation practices over different eras, could contribute to increases in NUE. Modern genotypes had fewer, shallower nodal roots, and a greater number of metaxylem vessels in the second root node. Gaudin et al. (2011) found that teosinte and maize produce similar numbers of nodal roots, and both reduce root number in response to N stress, but by different mechanisms; teosinte reduces tiller number, while maize reduces the number of roots elongated, particularly in younger node.

The role of root anatomy in stress adaptation has received relatively little attention compared with root system architecture (RSA) and morphology. Several recent reviews of root phene-based breeding and phenotyping focused almost exclusively on methods and gene targets relating to RSA (e.g. Cobb et al., 2013; Fiorani and Schurr, 2013; Meister et al., 2014; Paez-Garcia et al., 2015). Lynch (2013, 2015, 2018) suggested that anatomical phenotypes which reduce metabolic cost per root segment, such as fewer cortical cell files and agreater proportion of aerenchyma, could enable rapid, deeper rooting, which is beneficial under drought or low N stress. Similarly, root cortical senescence reduces root metabolic costs, and has been proposed as an adaptation for soil resource capture (Schneider et al., 2017a, b; Schneider and Lynch, 2018). Schmidt and Gaudin (2017) suggested that optimization of aerenchyma formation and endodermal barrier development could enhance tolerance of saline, waterlogged soil common in irrigated environments, and discuss trade-offs of increasing specific root length, including restriction of hydraulic conductivity. Richards and Passioura (1989) bred wheat varieties to contrast by 10 μm in vessel diameter in seminal roots, and found that genotypes with narrower vessels showed up to 11% increased yield under drought. Reduced secondary root growth in common bean reduced metabolic costs and increased phosphorus stress tolerance (Strock et al., 2018). Variation in metaxylem vessel size and number has also been assessed for drought tolerance in legumes (Purushothaman et al., 2013; Prince et al., 2017).

To understand relationships between NUE and root anatomy, we evaluated several root anatomical phenes in different N regimes. We hypothesize that (i) node, genotype, and N treatment affect root anatomy; and (ii) root anatomical phenes scale with root diameter across N treatments. To better identify useful genetic variation for N stress effects on maize nodal root anatomy, 44 hybrid and 39 inbred genotypes were evaluated in the field under various N conditions. Effects of node, N availability, and genotype on nodal root anatomy are presented, as well as phenotypic patterns associated with NUE.

Materials and methods

Plant material

Field studies were conducted from 2013 to 2016 in Pennsylvania (PA) (PA13–PA16) with 44 hybrid and 39 inbred maize genotypes, and in 2014 in South Africa (SA14) with 25 inbred genotypes. All genotypes are listed in Supplementary Table S1 at JXB online. Hybrid seed from select genotypes was provided by the Genomes to Fields (G2F) Consortium, curated for diversity and regional adaptation by G2F (see https://www.genomes2fields.org/home/). Recombinant inbred lines from three populations designated IBM, NYH, and OWRI were provided by D. Shawn Kaeppler at University of Wisconsin, Madison. IBM, NYH, and OWRI bi-parental populations are described in Burton et al. (2014). Root anatomical phenes as well as whole plant traits were collected for each experiment.

Field conditions

PA13–PA16 were conducted in 0.4 ha fields maintained with split high and low N treatments at The Pennsylvania State University’s Russell Larson Research Farm (40°42'40.915''N, 77°,57'11.120''W) which has Hagerstown silt loam soil (fine, mixed, semi-active, mesic Typic Hapludalf). To generate low N conditions, ~84 t ha–1 sawdust was tilled into the soil 1–2 years before commencement of the study. The high N sides of the fields were fertilized with 146 kg N ha−1 applied as urea (46-0-0) in 2013 and 2014; 157 kg N ha−1 in 2015; and 213 kg N ha−1 in 2016, while no N fertilizer was applied on the low N sides. Fields received drip irrigation, nutrients other than N, and pest management as needed. Seeds were planted using hand jab planters in rows with 76 cm row spacing, 91 cm alleys, 23 cm plant spacing, 4.6 m plot length with 3.7 m planted, or ~56 800 plants ha−1. In PA13, PA14, and PA15, each genotype was planted in three-row plots, and plants from the middle row of each three-row plot were sampled; in PA16, single-row plots were used, and plants were sampled from the middle section of the plot. Planting dates were: 18 May 2013, 31 May 2014, 14 June 2015, and 25 May 2016, respectively. Following anthesis, root harvest began on: 21 August 2013, 25 August 2014, 3 Septemeber 2015, and 8 August 2016, respectively.

SA14 was conducted at the Ukulima Root Biology Center in Alma, Limpopo, South Africa (24°33'0.12''S, 28°7'25.84''E, 1235 m asl), which has Clovelly loamy sand (Typic Ustipsamment). A total of 184 kg N ha−1 was applied to high N plots, through five applications of fertigation and granular urea. A total of 23 N ha−1 was applied to the low N plots at planting via fertigation. Pivot irrigation, nutrients, and pesticides were applied as needed. Hand-planting was completed on 26 November 2013, and root sampling began on 10 February 2014. Planting density was ~80 000 plants ha−1 with 76 cm row spacing. Genotypes were planted in three-row plots, and plants were sampled from the middle row of each plot.

Experimental design

All experiments were arranged in a split-plot randomized block design with different configurations. In PA13 and PA14, 30 genotypes were randomized in each of four replicates (blocks) of two N treatments (subplots within blocks), totaling 240 plots. In PA15, 11 genotypes were randomized in four blocks within two N treatments, totaling 88 plots. In PA16, 44 genotypes were randomized in two blocks with two N treatments, totaling 178 plots. In SA14, 25 genotypes were randomized into each of four high N and four low N blocks, totaling 208 plots. In PA13 and PA16, separate 0.4 ha fields were used for each block; in PA14, two 0.4 ha fields were subdivided into eight blocks; in PA15, one 0.4 ha field was subdivided into eight blocks; and in SA14, blocks were randomly assigned within a center pivot and split N treatments were applied.

Plant harvest and root sampling

A representative plant from each plot was excavated manually (Trachsel et al., 2011) at anthesis for all experiments. Root crowns were separated from the shoots, soaked in water with detergent, and rinsed to remove remaining soil. Each node of roots was excised, and up to three representative roots from select nodes for each study (Supplementary Table S2) were sampled at 2–4 cm from the base of the stem and preserved in 75% ethanol for anatomical processing. See Supplementary Fig. S1 for excised root crown images. Shoot biomass was separated into stem, leaves, and ears, dried at ~70 °C for 72 h, and weighed. Ears from eight plants per plot (PA16) and five plants per plot (PA15) were collected at physiological maturity, dried to ~15% moisture content, shelled, and weighed. Dried leaves collected at anthesis were ground, homogenized, and a 2 mg subsample was analyzed for total N content with a CHN elemental analyzer (2400 CHNS/O Series II, PerkinElmer, Waltham, MA, USA).

Image analysis

The middle portion of two representative root segments per node were ablated and imaged using laser ablation tomography (LAT). This technique employs a nanosecond pulsed UV (355 nm) laser (Avia 355-7000, Coherent, Santa Clara, CA, USA) focused into a scanning beam line with a HurryScan 10 galvanometer (Scanlab, Puchheim, Germany) to ablate the cross-sectional surface of a root secured to a three-axis motorized stage (ATS100-100, Aerotech Inc, Pittsburgh, PA, USA). The root is moved into the laser beam at ~30 μm s−1 and, as each surface is ablated and exposed, emission images are captured using a stage-mounted (#62-009, Edmund Optics, Barrington, NJ, USA) camera and ×5 macro lens (Canon EOS Rebel T3i camera with 65mm MP-E ×1–5 variable magnification, Canon USA Inc., Melville, NY, USA). Image scale was 1.173 pixels μm–1.

Images from all studies except PA14 were analyzed using ImageJ (Rasband, 2015), in combination with the ObjectJ plugin, in which cortex, stele, aerenchyma, vessel, and cell outlines were manually traced, and cell files manually counted (detailed in Supplementary Fig. S2). Images from PA14 were analyzed using RootScan2 software, which is based on RootScan (Burton et al., 2012b) but optimized for LAT images. Cortical cell file and metaxylem vessel numbers were manually validated.

Phene descriptions and abbreviations are given in Table 1. Total axial conductance (JSM) was calculated as the sum of Jvessel for all vessels in a root cross-section, using Hagen–Poiseuille corrected for an ellipse:

Table 1.

Description of maize root anatomy phenes

| Phene | Description |

|---|---|

| RXA | Root cross-section area (mm2) |

| CXA | Cortex cross-section area (mm2) |

| SXA | Stele cross-section area (mm2) |

| CSR | Cortex to stele ratio (=CXA/SXA) |

| CF | Number of cortical cell files |

| CCS | Median cortical cell size, from the mid-section of cortex (μm2) |

| MXN | Number of metaxylem vessels |

| MXA | Total metaxylem vessel area in cross-section (mm2) |

| MXP | Percentage of total metaxylem vessel area in the stele (=100×MXA/SXA) |

| AA | Total aerenchyma area in cross-section (mm2) |

| AAP | Percentage of aerenchyma area in the cortex (=100×AA/CXA) |

| MXL, MXW | Median metaxylem vessel diameter (μm): major axis (MXL) and minor axis (MXW) |

| MXM | Median single metaxylem vessel cross-section area (μm2) |

| CDM | Median cortical cell diameter across all cortical cell files (including both greater and lesser diameters) (μm) |

| HYP, OUT, INN | Median cortical cell diameter of hypodermis, and outermost and innermost cortical cell file (μm) |

| ECC | Median metaxylem vessel eccentricity |

| JSM | Estimated axial conductance rate of all metaxylem vessels in cross-section (m MPa−1 s−1) |

where v=viscosity (MPa s−1), a=major axis length (m), b=minor axis length (m), and (Δp/Δx)=pressure gradient (Lewis and Boose, 1995). Additional details used for calculation are outlined in Nobel (2006).

Statistical analysis

Statistical analysis and visualizations were generated using R version 3.3.1 (R Core Team, 2016). ANOVA was performed using the linear mixed effects lmer function in the nlme package (Pinheiro et al., 2018), with genotype and node as fixed effects, and N treatment as a fixed effect nested within a random block effect. Effect sizes on the three-way interaction of genotype, N treatment, and node were calculated using the etaSquared function in the lsr package (Navarro, 2015). Boxplots and bar plots were generated using data aggregation functions from the package plyr (Wickham, 2011) and plotting functions from the package ggplot2 (Wickham, 2016). Principal component analysis (PCA) was performed with scaled, centered data using the prcomp function and visualized with the autoplot function in the ggfortify package (Tang et al., 2016). Correlation matrices of scaled, centered data were generated with the corrplot package (Wei and Simko, 2017). Color-coded values are Spearman’s rank coefficient, and circle size scales with P-value, with blank cells when correlations are not significant at P<0.05. Phene arrangement and grouping (large boxes) are based on hierarchical clustering for the pre-determined number of clusters in order to group related phenes. Power models were generated using the natural log of x and y variables, with the r2 value and P-value from simple linear regression (lm, y~x) indicated on each plot. The percentage of genotypes with significant plastic response across nodes was calculated using a paired Type II t-test, matched by node and replicate; the percentage of genotypes with a significant plastic response within each node was calculated using a paired Type II t-test, matched by replicate. Allometric relationships were modeled using a linear regression of the natural log of anatomical phenes against the natural log of shoot biomass; the significance of N treatment on allometric scaling constants and intercepts in these relationships was determined using ANCOVA (analysis of covariance).

Results

Nodal root anatomical phenes clustered into four groups

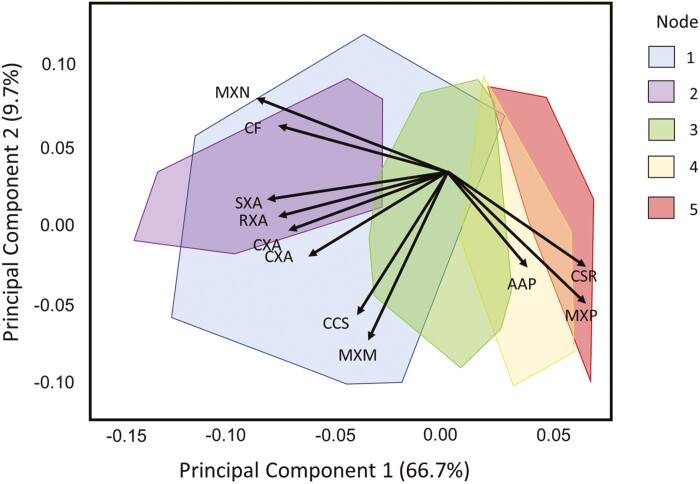

Maize root anatomy differed significantly by genotype, N treatment, and node (Fig. 1). Root anatomical phenes across nodes visually clustered into four groups by PCA (Fig. 2). ‘Root diameter-related’ phenes included the most strongly related phenes—root cross-sectional area (RXA), cortex cross-sectional area (CXA), stele cross-sectional area (SXA), total metaxylem cross-sectional area (MXA)—as well as cortical cell file number (CF) and the number of metaxylem vessels (MXN). These six phenes loaded strongly negatively on the first principal component (PC1), which explained 67% of the total variance (Fig. 2). ‘Proportion-related phenes’ included cortex to stele area ratio (CSR), the percentage of metaxylem vessel area in the stele (MXP), and the percentage of aerenchyma area in the cortex (AAP). These phenes loaded negatively on PC2, which explained 10% of variance. The median cross-sectional area of a single metaxylem vessel (MXM) and median cortical cell size (CCS) also loaded strongly negatively on PC2 (Fig. 2). Phenes also clustered into ‘vessel-related’ and ‘cortical cell-related’ phenes.

Fig. 1.

Nodal variation in maize root anatomy. Nodal root cross-section images from high N field-grown maize hybrids, sampled from older to younger nodes (left to right, numbered) from two genotypes (row A, B). Scale applies to all images.

Fig. 2.

Principal component analysis of root anatomy phenes. Biplot of the first two principal components (PC 1, 2) of a principal component analysis on 11 root anatomy phenes. Points indicate scores of individual roots on these two components, from nodes 1 to 5 (by color, and outlined by convex hull) of field-grown maize inbred lines and hybrids (PA14, PA15, PA16, total n=1171) in high and low nitrogen treatments (by shape). Arrows represent loadings of root anatomy phenes (labeled) on these two components. See Table 1 for phene abbreviations. PC1 and PC2 explained 66.7% and 9.7% of total variance, respectively.

Node, genotype, and nitrogen treatment affected root anatomy

Genotype,N treatment, and node all affected expression of root anatomical phenes. The interaction and combinations of interactions between genotype, treatment, environment, and node were significant drivers in root anatomy (Table 2; Supplementary Tables S3–S5). All anatomical phenes (see Table 1 for abbreviations) varied by genotype, and all except the percentage of aerenchyma in the cortex (AAP) varied by node in hybrids (Table 2). In inbred lines, all phenes evaluated varied by genotype, while all except the percentage of metaxylem vessel area in the stele (MXP) varied by node (see Supplementary Table S3, S4). Genotype×N, genotype×node, and environment×genotype interactions were significant for many phenes, while N, N×node, and genotype×N×node were less important (Table 2; Supplementary Tables S3–S5).

Table 2.

ANOVA table of genotype, nitrogen level, node, and interaction effects on maize root anatomy phenes

| G | T | N | G:T | G:N | T:N | G:T:N | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Root diameter-related phenes | RXA | 3.1*** | 14.9 NS | 361*** | 1.8** | 1.2 NS | 10.9*** | 0.7 NS |

| CXA | 3.1 *** | 25.5NS | 341.7 *** | 1.8 ** | 1.2 NS | 7.8*** | 0.8 NS | |

| SXA | 2.6*** | 6.7 NS | 318.3*** | 1.8** | 1.2 NS | 14.4*** | 0.7 NS | |

| MXA | 3*** | 8.2 NS | 253.5*** | 2.1*** | 1.5* | 4.7** | 1 NS | |

| CF | 5*** | 15.8*** | 404.1*** | 2.6*** | 1 NS | 2.4. | 0.6 NS | |

| MXN | 4.7*** | 30.9 NS | 389.6*** | 2.2*** | 1.3. | 7.7*** | 0.7 NS | |

| Proportion phenes | CSR | 1.9** | 0.7 NS | 123.7*** | 1.6* | 1.1 NS | 8*** | 0.8 NS |

| AAP | 1.7** | 3.6 NS | 1.9 NS | 1.3 NS | 0.8 NS | 0 NS | 0.8 NS | |

| MXP | 4.7*** | 4.4* | 182.4*** | 1.3 NS | 1 NS | 5.4** | 0.8 NS | |

| Metaxylem vessel-related phenes | MXM | 2.5*** | 12.6*** | 51.3*** | 1.5* | 1.2 NS | 0.1 NS | 1 NS |

| MXL | 2.8 *** | 10.0** | 43.9 *** | 1.5 * | 1.3 | 0.3 NS | 1.0 NS | |

| MXW | 2.2 *** | 10.1** | 66.0 *** | 1.6 * | 1.2 NS | 0.5 NS | 0.7 NS | |

| ECC | 2.9*** | 1 NS | 8.9*** | 1 NS | 1.1 NS | 2.7. | 1.2 NS | |

| JSM | 2.5 *** | 8.0 NS | 131.0 *** | 1.8 ** | 1.4 * | 5.2 ** | 1.1 NS | |

| Cortical cell-related phenes | CDM | 1.8 ** | 49.3*** | 7.0 ** | 1.2 NS | 1.2 NS | 5.3** | 0.9 NS |

| CCS | 1.7** | 40.6*** | 24.1*** | 1.3 NS | 1 NS | 0.8 NS | 1.1 NS | |

| HYP | 1.5 * | 0.0 NS | 30.7 *** | 1.3 NS | 1.1 NS | 6.9** | 0.9 NS | |

| OUT | 1.8 ** | 10.2** | 40.7 *** | 0.9 NS | 0.9 NS | 3.3* | 0.7 NS | |

| INN | 1.8 ** | 10.0 | 4.3 * | 1.2 NS | 1.0 NS | 5.5** | 1.0 NS |

ANOVA results from 39 genotypes (G)×2 nitrogen treatments (T)×3 nodes (N)×2 replicates (n=468) from PA16. F-values and significance levels [P<0.1, 0.05*, 0.001**, 0.0001***, not significant (>0.1), NS] are given for each phene (see Table 1 for abbreviations) for each main factor (G, T, N) and all factor interactions (G:T, G:N, T:N, G:T:N). Data from root nodes 2, 3, and 4 were included. Five genotypes were excluded due to missing data.

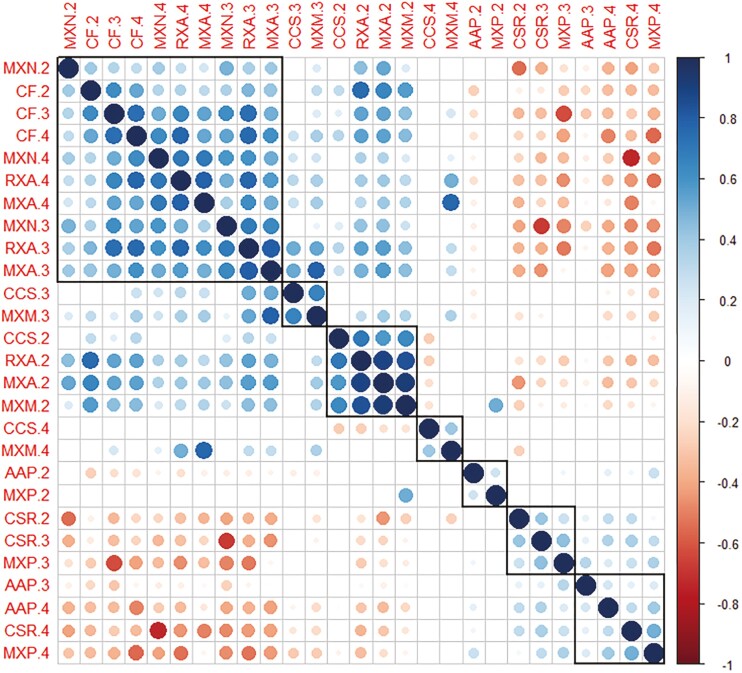

Node effects exceeded genotypic and nitrogen stress effects on root anatomy

The amount of variation attributable to root node exceeded all other sources of variation for root diameter-related phenes, as well as CSR, MXP, and the total estimated axial conductance rate of metaxylem vessels (JSM) (Table 3). Metaxylem vessel- and cortical cell-related phenes, including aerenchyma, showed the greatest relative amount of residual variation, among hybrid and inbred lines (Table 3; Supplementary Table S3, S4). Diameter-related phenes increased with each younger node, with greater relative increases in total stele and metaxylem vessel areas; in contrast, median metaxylem vessel size increased and then plateaued after the first three nodes, and cortical cell size patterns varied, with modest increases in the maximum and median cell diameters balanced by decreasing hypodermis and outer file cell sizes (Fig. 3; Supplementary Fig. S3). In addition, root anatomical phenes were correlated across nodes among genotypes, but the strength of correlation differed by node. For most phenes, the second node clustered independently from nodes three and four and was more strongly related to other phenes within its node (reduction in MXM drove the decrease in MXA across nodes in inbred lines, similar to the CF and CCS pattern). CCS and MXM correlated more strongly within node, a novel association (Fig. 4). From nodes two to four in hybrids, CF and MXN correlated strongly independent of node; sampling any of these nodes would generally result in similar CF and MXN phenotypes (Fig. 4).

Table 3.

Effect size of genotype, nitrogen treatment, and node on maize root anatomical phenes

| G | T | N | G:T | G:N | T:N | G:T:N | Resid | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Root diameter-related phenes | RXA | 9.5 | 4.2 | 50 | 5 | 6.6 | 1.4 | 3.9 | 19 |

| CXA | 10 | 4.8 | 49 | 5 | 6.7 | 1.1 | 4.2 | 20 | |

| SXA | 8.8 | 3.1 | 49 | 5.4 | 7.4 | 2 | 4.4 | 20 | |

| MXA | 11 | 2.9 | 41 | 6.8 | 9.4 | 0.6 | 6.1 | 22 | |

| CF | 13 | 1 | 52 | 6.4 | 4.8 | 0.3 | 2.8 | 20 | |

| MXN | 13 | 2.4 | 52 | 5.7 | 7 | 0.9 | 3.5 | 16 | |

| Proportion phenes | CSR | 9.7 | 0.5 | 34 | 8.2 | 11 | 2 | 7.9 | 27 |

| AAP | 14 | 2.8 | 0.3 | 11 | 14 | 0.1 | 13 | 45 | |

| MXP | 19 | 0.4 | 38 | 5.3 | 8.3 | 1.2 | 6.8 | 21 | |

| Metaxylem vessel-related phenes | MXM | 15.9 | 1.6 | 16 | 8.7 | 14 | 0 | 11 | 32 |

| MXL | 18 | 1.3 | 13 | 8.4 | 15 | 0.1 | 12 | 33 | |

| MXW | 14 | 1.3 | 20 | 9.3 | 14 | 0.1 | 8.4 | 32 | |

| ECC | 21 | 0.3 | 3.4 | 6.9 | 15 | 1.2 | 17 | 35 | |

| JSM | 13 | 3 | 28 | 8 | 12 | 0.8 | 9.2 | 27 | |

| Cortical cell-related phenes | CDM | 13 | 9 | 2.5 | 8.4 | 18 | 1.9 | 13 | 35 |

| CCS | 12 | 7 | 8.3 | 9 | 14 | 0.4 | 15 | 34 | |

| HYP | 9.8 | 0 | 12 | 9.3 | 16 | 2.6 | 13 | 38 | |

| OUT | 13 | 2.3 | 15 | 6.9 | 13 | 1.5 | 10 | 37 | |

| INN | 13.5 | 5.7 | 1.9 | 8.5 | 15.6 | 2 | 15 | 37.9 |

Effect sizes (%) for genotype (G), nitrogen treatment (T), and root node (N) and their interactions for each anatomical phene in PA16 (n=468). Effect sizes are the proportion of variation in the phene explained by the given factor, interaction, or other sources (residuals). See Table 1 for phene abbreviations. Root nodes 2, 3, are 4 included. For each phene, the maximum source of variation is in bold; if this source is an interaction or residual, the maximum main factor source of variation is underlined.

Fig. 3.

Root anatomy variation by node in field-grown maize hybrids. Boxplots of nodal root anatomy phenes evaluated in nodes 1 (oldest) through 5 (left to right in each plot) from 44 field-grown maize hybrid genotypes, including high and low nitrogen treatments (PA16). Horizontal box lines indicate the 25th, 50th, and 75th percentile; whiskers indicate range, excluding outliers (points). Total n=469 per plot. See Table 1 for phene abbreviations.

Fig. 4.

Maize root anatomy phene relationships across nodes. Correlation matrix of root anatomy phenes evaluated in nodes 2, 3, and 4 (numbered) in n=69 mean phene values per node from low nitrogen field-grown maize hybrids (PA16). Color scale indicates Spearman’s ranked correlation coefficient. Larger circle size reflects smaller P-value; blank cells indicate that correlation was not significant at P<0.05. Most strongly related phenes are ordered and grouped in black boxes according to hierarchical clustering. See Table 1 for phene abbreviations.

Genotypic variation in nodal root anatomy

Anatomical variation among genotypes ranged from 12% for CF to 96% for AAP among hybrids across nodes two to four, and from 3% for median metaxylem vessel eccentricity (ECC) to 32% for AAP among inbred lines across nodes one to three (Table 4: Supplementary Table S6). Stele and vessel phenes (SXA, MXA, JSM, MXN, and MXM) had greater across-genotype variation than cortical phenes (CXA, CF, and CCS), but also had greater within-genotype variation (Table 4; Supplementary Tables S3, S7). Genotypic variation differed modestly by N treatment and node; low N induced a slight reduction in genotypic variation, while the first node showed the least variation (Table 4; Supplementary Table S6). Within genotypes, variation ranged from an average of 11% for median cortical cell diameter (CDM) to 96% for total aerenchyma area (AA) across nodes among hybrids, and from 10% for CF to 64% for AAP across nodes among inbred lines (Supplementary Table S7). Within-genotype variability was similar across nodes and N treatments (Supplementary Table S7).

Table 4.

Genotypic variation in maize root anatomical phenes by node

| N2 | N3 | N4 | Mean | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| HN | LN | HN | LN | HN | LN | |||

| Root diameter-related phenes | RXA | 28.1 | 30.7 | 31.4 | 30.4 | 32.6 | 29.7 | 30.5 |

| CXA | 28.4 | 30.1 | 31.2 | 28.4 | 30.8 | 28 | 29.5 | |

| SXA | 31.2 | 34.5 | 33.7 | 37.2 | 38.6 | 35.8 | 35.2 | |

| MXA | 35.6 | 36.4 | 36.7 | 29.3 | 37.3 | 30.8 | 34.4 | |

| CF | 9.9 | 10.7 | 12.3 | 12.3 | 11.6 | 12.7 | 11.6 | |

| MXN | 16.7 | 16.7 | 17.2 | 21.5 | 21 | 23.4 | 19.4 | |

| Proportion phenes | CSR | 16.3 | 18 | 12.4 | 13.3 | 17.7 | 19.7 | 16.2 |

| AAP | 107.4 | 90 | 101.9 | 82.1 | 104 | 93 | 96.4 | |

| MXP | 14.4 | 13.4 | 21.6 | 17.8 | 22.8 | 20.8 | 18.5 | |

| Metaxylem vessel-related phenes | MXM | 28.9 | 29.6 | 28.4 | 22 | 27.5 | 19.5 | 26 |

| MXL | 15.4 | 15.9 | 16 | 12.2 | 16 | 11.2 | 14.5 | |

| MXW | 14.7 | 14.8 | 11.6 | 9.8 | 12.9 | 9.7 | 12.3 | |

| ECC | 13.1 | 15.5 | 17.1 | 14.2 | 16.7 | 17.8 | 15.7 | |

| JSM | 59.5 | 63.5 | 68.3 | 44.6 | 58.4 | 47.7 | 57 | |

| Cortical cell-related phenes | CDM | 15.3 | 11.8 | 13.5 | 9.9 | 16.2 | 11.4 | 13 |

| CCS | 25.8 | 21.2 | 29.5 | 18.4 | 24.8 | 20.4 | 23.4 | |

| HYP | 17.7 | 15 | 15 | 11.4 | 17.5 | 13.6 | 15 | |

| OUT | 29 | 21 | 22.1 | 21.5 | 20.3 | 16.7 | 21.8 | |

| INN | 15.2 | 13.9 | 15.3 | 13.2 | 20.5 | 13.6 | 15.3 | |

Genotypic coefficients of variation (GCV, %) for each phene, where [CV=100×SD of phene value)/(mean phene value)] using mean phene values for each genotype, by node (N2, N3, N4) and nitrogen treatment (HN, LN) in field-grown maize hybrids (PA16, n=39 genotypes; five genotypes excluded due to missing data). Mean GCV across nodes and nitrogen treatments are in bold. See Table 1 for phene abbreviations.

Genotypic differences in anatomical plasticity under low nitrogen

Anatomical plasticity in response to N differed across genotypes; for example, N did not change MXA in hybrid genotypes 1, 11, and 27, when averaged across nodes (Fig. 5, subset of representative genotypes; Supplementary Fig. S4, all genotypes). In contrast, low N reduced MXA in genotypes 2, 23, 35, and 42, and increased it in genotype 28 (Fig. 5; Supplementary Fig. S4). Genotypes also differed in the magnitude of plasticity; genotypes 2, 23, and 42 had strong plastic responses of >50% decrease in MXA under low N, whereas genotypes 35 and 28 had weaker responses (Fig. 5, Supplementary Fig. S4). Relative plasticity was calculated as the percentage of genotypes which had a statistically significant response under low N (‘plastic genotypes’), and the percentage of those genotypes which had a negative (decrease in phene value) response and/or a strong response (>50% increase or decrease in phene value) (Table 5). Plasticity ranged from 0% (ECC) to 31% (RXA) of hybrids showing any significant change under low N, across nodes, with lower percentages when calculated for phenes of any single node (Table 5). The relatively low plasticity of genotypes with significant responses reflected strong within-genotype variability; for example, only 11% of genotypes had a statistically significant low N response in SXA, but 75% of genotypes showed a strong (>50%) change in phene state under low N (Table 5). Low N decreased most phene states across nodes (Table 5, hybrids; inbred data not shown).

Fig. 5.

Genotypic variation in plasticity of total metaxylem vessel area (mm2) under low nitrogen. Mean ±SE metaxylem vessel area (mm2) across nodes 2, 3, and 4 under high or low nitrogen (HN, blue; LN, red) for select maize hybrid genotypes (see Supplementary Table S1 for genotype codes). Asterisks represent genotypes with significant differences (P<0.05) between nitrogen treatments according to a pairwise comparison of phene values matched by node.

Table 5.

Anatomical response to nitrogen stress among genotypes

| Phene | Percentage of genotypes with | Percentage of plastic genotypes with | ||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Plastic response (P<0.05) | Strong response (>50%) | Negative response (–) | ||||||||||

| All | N2 | N3 | N4 | All | N2 | N3 | N4 | All | N2 | N3 | N4 | |

| RXA | 31.4 | 2.9 | 8.6 | 8.6 | 63.6 | 0 | 66.7 | 66.7 | 90.9 | 0 | 66.7 | 66.7 |

| SXA | 11.4 | 2.9 | 8.6 | 2.9 | 75 | 100 | 100 | 100 | 75 | 100 | 66.7 | 100 |

| MXA | 20 | 2.9 | 5.7 | 5.7 | 71.4 | 100 | 50 | 50 | 85.7 | 100 | 50 | 50 |

| CF | 25.7 | 14.3 | 17.1 | 11.4 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 77.8 | 60 | 66.7 | 50 |

| MXN | 25.7 | 2.9 | 11.4 | 5.7 | 11.1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 88.9 | 100 | 75 | 0 |

| CSR | 11.4 | 5.7 | 8.6 | 5.7 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 75 | 50 | 66.7 | 0 |

| AAP | 5.7 | 2.9 | 0 | 8.6 | 100 | 100 | – | 100 | 50 | 0 | – | 66.7 |

| MXP | 8.6 | 5.7 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | – | – | 0 | 50 | – | – |

| MXM | 8.6 | 5.7 | 5.7 | 5.7 | 33.3 | 50 | 50 | 0 | 100 | 100 | 100 | 50 |

| ECC | 0 | 0 | 5.7 | 2.9 | – | – | 0 | 0 | – | – | 50 | 0 |

| JSM | 11.4 | 5.7 | 8.6 | 8.6 | 75 | 100 | 0 | 66.7 | 100 | 100 | 33.3 | 100 |

| CDM | 22.9 | 17.1 | 0 | 5.7 | 0 | 16.7 | – | 0 | 100 | 100 | – | 0 |

| CCS | 20 | 8.6 | 0 | 5.7 | 42.9 | 0 | – | 50 | 100 | 66.7 | – | 100 |

| HYP | 5.7 | 2.9 | 5.7 | 5.7 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 100 | 0 |

| OUT | 5.7 | 8.6 | 2.9 | 2.9 | 50 | 0 | 100 | 0 | 100 | 100 | 100 | 0 |

| INN | 14.3 | 5.7 | 2.9 | 8.6 | 20 | 0 | 100 | 0 | 100 | 100 | 100 | 66.7 |

| Mean | 14.3 | 5.9 | 5.7 | 5.9 | 36.2 | 31.1 | 38.9 | 28.9 | 76.2 | 68.4 | 72.9 | 43.3 |

The percentage of evaluated maize genotypes which showed significant phene response (P<0.05) under low N stress (‘Plasticity’) for the indicated anatomical phene, averaged across nodes 2, 3, and 4 (‘All’) and for each node (N) individually; the percentage of plastic genotypes which showed a negative response (i.e. decreased phene value) under low N (‘Direction’); and the percentage of plastic genotypes which showed a strong response (>50% change in phene value, ‘Strength’) among field-grown hybrids (PA16, n=140 per phene, per node). See Table 1 for phene abbreviations.

Anatomical differences among high and low NUE genotypes

Genotypes were matched according to high N yield, then sorted into high or low NUE groups (HNUE and LNUE) according to low N yield. LNUE hybrids had an average of 32% less yield under low N compared with HNUE genotypes; for inbred lines, the difference was 22% (Fig. 6). HNUE genotypes generally had greater RXA, MXA, CCS, and MXM, and less AAP, under low N, relative to LNUE genotypes (Fig. 6). The magnitude of these differences was small under both high and low N, and less among inbred lines with milder N stress (Fig. 6). Overall, HNUE and LNUE lines differed the least in anatomy and responses in the third node; the second and fourth nodes showed similar patterns and responses, but the fourth node typically showed greater separation between HNUE and LNUE values (Supplementary Fig. S5; not all phenes shown).

Fig. 6.

Anatomical differences among HNUE and LNUE genotypes. Genotypes were matched based on high N yield and then grouped according to high or low N use efficiency (HNUE, black; LNUE, gray) based on low N yield. For PA16, 22 hybrid genotypes were included in each group; for PA15, four inbred genotypes were in each group. Genotypes with variable performance were excluded. Means ±SE of yield and select anatomical phenes under high and low N (HN, LN) conditions are plotted; phenes are averaged across nodes 2, 3, and 4 for PA16, and nodes 1, 2, and 3 for PA15. See Table 1 for phene abbreviations and units.

Node-specific nitrogen stress effects on root anatomy

Root diameter-related phenes were reduced under N stress, with greater decreases in the youngest nodes in hybrids; this progression across nodes was less evident in inbred lines, which had milder N stress (Fig. 7; Supplementary Fig. S6; Supplementary Table S8). The exception was CF, which changed little under low N relative to other phenes (Fig. 7). In contrast to hybrids, MXN also was insensitive to low N; reduction in MXM drove the decrease in MXA across nodes in inbred lines, similar to the CF and CCS pattern (Supplementary Fig. S7). Low N increased the cortex to stele ratio (CSR) and percentage of metaxylem vessel area (MXP) in younger nodes of hybrids (Fig. 7; Supplementary Fig. S7). The percentage of aerenchyma area (AAP) increased >2-fold in response to low N stress in the first node, the largest low N-induced change in root anatomy, and increased in nodes two to four to similar levels under low N; node five had little AAP, with a slight increase under low N (Fig. 7; Supplementary Table S7). AAP showed less pronounced differences under milder low N stress in inbred lines (Supplementary Fig. S7).

Fig. 7.

Node-specific root anatomy responses to nitrogen stress. Root phene means ±SE by node (x-axis) and nitrogen treatment (blue, HN; red, LN) in field-grown maize genotypes (PA16). Total n=469 roots per plot. See Table 1 for phene abbreviations and units. Percentage changes under LN by node are given in Supplementary Table S5.

Root anatomical phenes scale with root diameter across nitrogen treatments

Power relationships between RXA and all anatomical phenes were significant, with the exception of vessel eccentricity (ECC) and median cortical cell diameter averaged across the cortex (CDM) (Supplementary Fig. S8). N stress did not affect these relationships, with the exception of AAP, in which the slope of the scaling relationship increased under low N (Supplementary Fig. S8). Within nodes, the scaling relationships differed among phenes; phenes strongly related to root diameter showed small, progressive changes in slope with each node. Hypodermis and outer cortical cell diameters were less related to RXA in some nodes. Overall, scaling relationships between RXA and anatomical phenes were more similar in nodes three to five, and the first node showed the most distinct patterns (Supplementary Fig. S6).

Allometric relationships of root diameter are similar across nitrogen treatments

The allometric scaling coefficients of RXA against shoot biomass (quantified at anthesis) did not differ significantly between high and low N for nodes two, three, and four; however, allometric relationships were stronger under low N, and were not statistically significant under high N in nodes two and four (Supplementary Fig. S9). Shoot biomass was more strongly related to RXA in the third and fourth nodes, relative to the second node, among hybrids (Supplementary Fig. S9). Nodal root emergence occurs in coordination with shoot growth, with some variation in magnitude depending on genotype and under N stress (Supplementary Fig. S10A–C). Root diameter near the stem base typically does not change significantly until after anthesis, when some degradation may occur and cortical cell sizes shrink, particularly in older nodes (Supplementary Fig. S10D; data on other anatomical phenes and nodes not shown).

Cortical cell size distribution is strongly dependent on file number

For roots with the same CF, cell diameters by file did not differ strongly under N stress or among genotypes (Supplementary Fig. S11A–C). In roots with the fewest CF, cell diameters varied the least across files, whereas in roots with greater total CF, there was a gradual increase in cell diameter across the outer cortical files, followed by about six files of maximum cell diameter, and a slight decrease in cell diameter in the innermost file(s) (Supplementary Fig. S11A–C). Cortical cell diameter averaged across a root cross-section therefore confounds changes in the number of files of small, outer layer cortical cells with changes in the maximum cell diameter. Among field-grown hybrids, maximum cortical cell diameters differed by an average of 5 μm (high N, 51–56 μm) and 7 μm (low N, 44–51 μm) between the thinnest (6–11 CF) and thickest (15–27 CF) roots across nodes (data not shown).

Metaxylem vessel sizes show greater variation in younger nodes

Variability of vessel size was greatest in the first node and younger nodes from four onward; N stress reduced variability slightly in younger nodes (Supplementary Fig. S12A). The relative number of both very small and very large vessels increased in younger nodes (Supplementary Fig. S12B). Minimum vessel sizes were similar across nodes, while maximum vessel size increased with node (Supplementary Fig. S12C). Genotypic variation in the minimum and maximum metaxylem vessel size, and the number and percentage of very small and very large metaxylem vessels was significant across three root nodes (Supplementary Table S9). Of these phenes, only minimum vessel size did not differ significantly under low N treatment; all phenes varied significantly by node (Supplementary Table S9).

Discussion

We observed substantial anatomical variation across crown root nodes. In the first three nodes, root diameter and related anatomical phenes, such as cortical cell file number and metaxylem vessel number, increased in each successive node, a stark contrast to the relatively stable number of roots per node produced in these three nodes. However, the median cross-sectional area of metaxylem vessels plateaued after the third node, as reported by Stamp and Kiel (1992), coinciding with the transition to increasing numbers of roots per node. This pattern may reflect the balance between greater conductance required by larger shoots with risk of embolism from larger xylem vessels. Increasing root diameter with each node, driven by modest increases in cortical cell diameters and an increase in the number of outer cortical cell files, could relate to the increasing demand for water and nutrients. Increased metaxylem vessel area per root, driven by a larger number of large vessels, and an increase in the number of roots results in an average 140% increase in total conductance in the fifth node, relative to the fourth node, estimated from field-grown hybrids in high N (data not shown). The maize nodal root system therefore exhibits a distinct ‘root thickening’ strategy with each new node, and although this is driven more by an increase in stele area compared with cortical area, may be considered analogous to the secondary thickening function of taproot systems in dicotyledonous plants, which support prolific resource acquisition and plant growth via a single main stem.

Root anatomy influences stress adaptation

We found that hybrid genotypes with HNUE differed in root anatomy under low N, compared with less efficient (LNUE) genotypes; the HNUE and LNUE groups differed in yield, but not shoot biomass, under suboptimal N. HNUE genotypes had 14% larger root diameter, 22% greater total metaxylem vessel conductance, and 54% less aerenchyma formation under low N, compared with LNUE genotypes. These results contrast with previous findings which have shown that genotypes with greater aerenchyma induction performed better under N stress, as evaluated in the second root node (Saengwilai et al., 2014). Three factors may contribute to this disparity. The first is that in the study by Saengwilai et al., genotypes were selected to be ‘isophenic’: they were closely related genetically (i.e. recombinant inbred lines descending from the same two parents) selected to be contrasting for RCA but otherwise phenotypically similar. In the current study, a range of genotypes was employed, both inbred and hybrid lines, that were not selected to be ‘isophenic’ and displayed a wide range and combination of anatomical phenes. Interactions among root phenes can influence the utility of individual phenes. A few root phene synergisms have been explored (Miguel et al., 2015; Rangarajan et al., 2018), and phene synergisms show strong interactions with environmental conditions (Trachsel et al., 2013; Dathe et al., 2016). Understanding and accounting for phene interactions is important in determining the utility of a phene state for resource capture. The second factor is that we observed that aerenchyma expression in the second node, which was the focus of the Saengwilai et al. study, was either weakly correlated or not correlated with aerenchyma in other nodes within a genotype. The third factor is that aerenchyma formation can be induced by N stress (Saengwilai et al., 2014), therefore HNUE genotypes may have had less aerenchyma formation because they were less stressed due to other adaptations to suboptimal N availability. The relative metabolic costs and functions of root anatomical phenotypes across nodes merit further research.

HNUE genotypes maintained larger axial root diameter and greater vessel conductance, through both larger size and number of cells and vessels, and had reduced induction of aerenchyma formation under N stress. These phenotypes either could be causally beneficial (i.e. directly contributing to improved NUE) or they could be the results of greater growth from improved NUE (e.g. influenced by allometry or other variables; see below). Optimizing hydraulic conductance is a primary function of axial roots, whereas absorptive functions and greater specific root length are central functions of lateral roots, and exist under separate genetic control (Jordan et al., 1993; Hochholdinger et al., 2004). Thick axial roots, which often have layers of small, suberized outer cortical cells and less porosity (in terms of both intercellular space and aerenchyma lacunae), have greater mechanical strength, and support better anchorage and lodging resistance, resilience to herbivory, longevity, and soil penetration in drying soils and hardpans (Eissenstat, 1992; Stamp and Kiel, 1992; Jordan et al., 1993; Eissenstat et al., 2000; Striker et al., 2007; Liu et al., 2012a; Chimungu et al., 2015) Developing thicker roots would not substantially increase intra-plant competition, which has been suggested as a key trade-off to overproduction in number of roots, due to increased probability of overlapping uptake zones of mobile nutrients and water (Postma et al., 2014).

The slower development of large diameter roots could also reduce inter-plant competition in monoculture. Roots in the third and younger nodes have steeper angles and greater rooting depth, depending on genotype and soil conditions (Yamazaki and Kaeriyama, 1982; Hoppe et al., 1986; Araki et al., 2000; Liu et al., 2012b; York and Lynch, 2015), supporting the potential importance of larger diameter roots in penetrating deep soil for mobile resources. The functional utility and trade-offs of these root anatomical phenes under different environmental conditions require further study.

The maximum metaxylem vessel diameters increased with node and root diameter, as did the maximum cortical cell diameter, although variation in this phene was minimal. Instead, average cortical cell diameters reflected changes in the number of small, outer layer cortical cells. Thus, aggregate metrics of an average or median vessel or cell diameter may confound differences in root diameter with genotypic contrasts in vessel or cell size, specifically, and the functional benefits of cell sizes (e.g. for metabolic cost versus structural integrity) should be studied in the context of these different cortical regions.

Anatomical plasticity and allometry differ among genotypes

Plasticity and allometry often complicate the analysis of phenotypic variation (e.g. Weiner, 2004). For example, Wahl and colleagues found that shading had specific effects on axial root anatomy in grasses, while nutrient deprivation resulted in anatomical changes that were proportional to changes in plant size (Wahl et al., 2001). We observed genotypic variation for anatomical plasticity in response to N availability: 31% of hybrids changed root diameter under N stress, predominantly by decreasing stele diameter, and 64% had a diameter change of ≥50%. Even considering phenotypic variability among nodes, the overall plastic response of genotypes was best classified using aggregate data across nodes. Root diameter and cortical aerenchyma were similar for HNUE and LNUE genotypes in high N, and both HNUE and LNUE genotypes manifested decreased root diameter under N stress. However, HNUE genotypes showed less decrease than did LNUE lines. These patterns were evident in each node, but the fourth node showed the strongest contrast. The lack of anatomical plasticity displayed by HNUE genotypes could be interpreted in several ways: (i) less anatomical plasticity is beneficial under N stress; (ii) larger diameter roots and reduced aerenchyma confer adaptive benefits under N stress; or (iii) the lack of plasticity, larger root diameter, and reduced aerenchyma are a result of HNUE genotypes being less stressed than LNUE genotypes, and anatomical differences in successively younger nodes reflect progressively greater stress in later growth stages. Phenotypic screens for root anatomy should consider stress effects and variation in anatomical plasticity among genotypes, and the relevance of phenotyping root anatomy in younger nodes. Root anatomy of younger nodes is relevant for N uptake at critical growth stages, but it may be difficult to distinguish whether phenes are adaptive or reflective of plant performance at later growth stages. Further study is needed on the relative benefits of stable versus plastic, stress-responsive root anatomy phenotypes.

HNUE genotypes did not have significantly greater shoot biomass at anthesis than LNUE genotypes in all treatments; however, it is still relevant to consider the effect of plant size on root anatomy. In this study, root diameter showed weak but significant hyperallometry, although N conditions did not significantly change the scaling constant of root diameter (averaged across three nodes) and shoot biomass. In other words, allometric constraints on root anatomy were limited. Smaller, N-stressed plants generally had thinner roots, but several genotypes either increased root diameter under stress, or showed varying degrees of increasing or decreasing root diameter under stress depending on root node. This suggests that root diameter and related anatomical phenes could play a role in adaptive stress responses, independent of plant size.

The magnitude and direction of plastic responses in root phenotypes such as axial and lateral root number and length under N stress vary among maize genotypes (Li et al., 2016; Yu et al., 2016). York and Lynch (2015) found that genotypes showed contrasting morphological and architectural responses from node to node under N stress. Analyzing adaptive responses in terms of allometric instability and recovery could be a useful application of phenotyping roots across multiple nodes (Coleman et al., 1994; Wilhelm and McMaster, 1995; Anfodillo et al., 2016). Further studies are needed to quantify the relationship of nodal root anatomy with plant size, and the effect of genotype and stress conditions on these allometric relationships.

Optimizing root phenotyping strategies

Optimizing root phenotyping and understanding the utility of root phenotypes is key to the success of trait-based breeding for improved nutrient and water capture. Few studies have addressed phenotypic variation within root systems (e.g. across nodes, positions, age, and root classes) across multiple genotypes, particularly in the field. Phenotyping of axial and lateral root phenotypes along different positions in maize root systems has been conducted in limited genotypes in hydroponic and aeroponic systems (e.g. Gaudin et al., 2011; Gao et al., 2015). A few root anatomical and architectural phenotypes in maize have been evaluated in multiple nodes in the field, typically in one or two genotypes (Yamazaki and Kaeriyama, 1982; Hoppe et al., 1986; Girardin et al., 1987; Demotes-Mainard and Pellerin, 1992; Jordan et al., 1993; Aguirrezabal et al., 1994; Pellerin, 1994; Liu et al., 2012b). Stamp and Kiel (1992) characterized 28 hybrid genotypes and evaluated six nodes with a focus on metaxylem vessel phenes, and Mano et al. (2006) evaluated aerenchyma formation across root nodes and positions in multiple Zea species. Intensive phenotypic profiling of nodal root architecture among several field-grown maize genotypes found significant node effects on root number and diameter, and weaker node effects on angle and lateral root branching (York and Lynch, 2015).

This study revealed that root anatomical phenotypes were strongly influenced by nodal position in field-grown maize. Additional studies may address additional root anatomical phenes, including three-dimensional phenes (e.g. volumes of cortical cells). We speculate that in addition to the root phenes presented herein, other important root phenes exist that have implications on NUE. In this study, root anatomy varied within genotype, and genotypic contrast and patterns in N stress responses were best discerned by aggregating data across three root nodes. The first two nodes were distinct from younger nodes, in terms of phenotypic patterns and stress responses, possibly reflecting developmental transitions that require further study. Phenotyping third and fourth nodes may lead to more representative characterization of nodal root anatomy among genotypes, while phenotyping across nodes is useful for more detailed studies of allometry, plasticity, and phene interactions.

Supplementary data

Supplementary data are available at JXB online.

Fig. S1. Image of a dissected maize root crown.

Fig. S2. Root image analysis protocol.

Fig. S3. Maize root anatomy phenes by node for inbred lines.

Fig. S4. Genotypic variation in plasticity of total metaxylem vessel area under low nitrogen.

Fig. S5. Anatomical differences among HNUE and LNUE genotypes.

Fig. S6. Scaling relationships of root anatomy and diameter by node.

Fig. S7. Nitrogen stress effects by node on root anatomy for inbred lines.

Fig. S8. Scaling relationships between root anatomy traits and root diameter.

Fig. S9. Allometric relationships of root diameter by node.

Fig. S10. Relationship between maize shoot and root development.

Fig. S11. Cortical cell sizes in roots of different cell file numbers.

Fig. S12. Metaxylem vessel size distribution across nodes.

Table S1. Plant materials.

Table S2. Plant nodes sampled.

Table S3. ANOVA table of genotype, nitrogen level, node, and interaction effects on inbred maize root anatomy.

Table S4. Effect size of genotype, nitrogen treatment, and node on root anatomy.

Table S5. ANOVA table of genotype, nitrogen level, node, environment, and interaction effects on inbred and hybrid maize root anatomy.

Table S6. Genotypic variation in maize root anatomical phenes by node.

Table S7. Within-genotype variation in maize root anatomy by node and N treatment.

Table S8. Nitrogen stress induced change in root anatomy.

Table S9. ANOVA table of genotype, nitrogen, and node effects on hybrid maize nodal metaxylem phenotypes.

Acknowledgements

We thank Shawn Kaeppler and the G2F consortium for providing plant materials. For agronomic and technical support, we thank Robert Snyder, Michael Williams, Johan Prinsloo, Tania Galindo-Castañeda, Stephanie Klein, Claire Lorts, Jonathan Wu, Pufan Wang, Ryan Burnett, Andrew Evensen, Larry York, and Joseph Chimungu. We thank Benjamin Hall at L4IS and support from the Edmund Optics Higher Education Grant for technical support and improvements to the LAT platform, and Dannielle Gibson, John Sosa, and Tim Ryan for work on three-dimensional root segmentation. This work was supported by USDA NIFA AFRI grant 2013-02682 to JPL, the Howard G. Buffett Foundation, and the USDA National Institute of Food and Agriculture, Hatch project 4372.

Glossary

Abbreviations:

- AA

total aerenchyma area

- AAP

percentage of cortex that is aerenchyma

- CCS

cortical cell size

- CDM

median cortical cell diameter

- CF

number of cortical cell files

- CSR

cortex to stele ratio

- CXA

cortex cross-sectional area

- ECC

metaxylem vessel eccentricity

- HNUE

high nitrogen use efficiency

- JSM

estimated axial conductance rate of all metaxylem vessels

- LAT

laser ablation tomography

- LNUE

low nitrogen use efficiency

- MXA

metaxylem vessel area

- MXL

median metaxylem vessel diameter (major axis)

- MXM

median single metaxylem vessel cross-section area

- MXN

number of metaxylem vessels

- MXP

percentage of total metaxylem vessel area in the stele

- MXW

median metaxylem vessel diameter (minor axis)

- N

nitrogen

- RXA

root cross-sectional area

- SXA

stele cross-sectional area.

References

- Aguirrezabal LAN, Deleens E, Tardieu F. 1994. Root elongation rate is accounted for by intercepted PPFD and source–sink relations in field and laboratory-grown sunflower. Plant, Cell and Environment 17, 443–450. [Google Scholar]

- Anfodillo T, Petit G, Sterck F, Lechthaler S, Olson ME. 2016. Allometric trajectories and ‘stress’: a quantitative approach. Frontiers in Plant Science 7, 1681. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Araki H, Hirayama M, Hirasawa H, Iijima M. 2000. Which roots penetrate the deepest in rice and maize root systems? Plant Production Science 3, 281–288. [Google Scholar]

- Burton AL, Brown KM, Lynch JP. 2013. Phenotypic diversity of root anatomical and architectural traits in species. Crop Science 53, 1042–1055. [Google Scholar]

- Burton AL, Johnson JM, Foerster JM, Hirsch CN, Buell CR, Hanlon MT, Kaeppler SM, Brown KM, Lynch JP. 2014. QTL mapping and phenotypic variation for root architectural traits in maize (Zea mays L.). Theoretical and Applied Genetics 127, 2293–2311. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Burton AL, Lynch JP, Brown KM. 2012a. Spatial distribution and phenotypic variation in root cortical aerenchyma of maize (Zea mays L.). Plant and Soil 367, 263–274. [Google Scholar]

- Burton AL, Williams M, Lynch JP, Brown KM. 2012b. RootScan: software for high-throughput analysis of root anatomical traits. Plant and Soil 357, 189–203. [Google Scholar]

- Chimungu JG, Brown KM, Lynch JP. 2014a. Large root cortical cell size improves drought tolerance in maize. Plant Physiology 166, 2166–2178. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chimungu JG, Brown KM, Lynch JP. 2014b. Reduced root cortical cell file number improves drought tolerance in maize. Plant Physiology 166, 1943–1955. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chimungu JG, Loades KW, Lynch JP. 2015. Root anatomical phenes predict root penetration ability and biomechanical properties in maize (Zea mays). Journal of Experimental Botany 66, 3151–3162. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Clarke J, McCaig N. 1993. Breeding for efficient root systems. In: Hayward M, Bosemark N, Romagosa I, eds. Plant breeding: principles and prospects. Dordrecht: Springer, Netherlands, 485–499. [Google Scholar]

- Cobb JN, Declerck G, Greenberg A, Clark R, McCouch S. 2013. Next-generation phenotyping: requirements and strategies for enhancing our understanding of genotype–phenotype relationships and its relevance to crop improvement. Theoretical and Applied Genetics 126, 867–887. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Coleman JS, McConnaughay KD, Ackerly DD. 1994. Interpreting phenotypic variation in plants. Trends in Ecology & Evolution 9, 187–191. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dathe A, Postma J, Postma-Blaauw M, Lynch J. 2016. Impact of axial root growth angles on nitrogen acquisition in maize depends on environmental conditions. Annals of Botany 118, 401–414. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- DeBruin JL, Schussler JR, Mo H, Cooper M. 2017. Grain yield and nitrogen accumulation in maize hybrids released during 1934 to 2013 in the US Midwest. Crop Science 57, 1431–1446. [Google Scholar]

- Demotes-Mainard S, Pellerin S. 1992. Effect of mutual shading on the emergence of nodal roots and the root/shoot ratio of maize. Plant and Soil 147, 87–93. [Google Scholar]

- Dhital S, Raun WR. 2016. Variability in optimum nitrogen rates for maize. Agronomy Journal 108, 2165–2173. [Google Scholar]

- Donald CM. 1968. The breeding of crop ideotypes. Euphytica 17, 385–403. [Google Scholar]

- Eissenstat D. 1992. Costs and benefits of constructing roots of small diameter. Journal of Plant Nutrition 15, 763–782. [Google Scholar]

- Eissenstat D, Wells C, Yanai R, Whitbeck J. 2000. Building roots in a changing environment: implications for root longevity. New Phytologist 147, 33–42. [Google Scholar]

- FAO . 2018. FAO STAT. http://www.fao.org/faostat/en/#home

- Fiorani F, Schurr U. 2013. Future scenarios for plant phenotyping. Annual Review of Plant Biology 64, 267–291. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fischer RA, Byerlee D, Edmeades G. 2014. Crop yields and global food security—will yield increase continue to feed the world? Canberra, ACT: ACIAR,8–11. [Google Scholar]

- Gao K, Chen F, Yuan L, Zhang F, Mi G. 2015. A comprehensive analysis of root morphological changes and nitrogen allocation in maize in response to low nitrogen stress. Plant, Cell & Environment 38, 740–750. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gaudin AC, McClymont SA, Holmes BM, Lyons E, Raizada MN. 2011. Novel temporal, fine-scale and growth variation phenotypes in roots of adult-stage maize (Zea mays L.) in response to low nitrogen stress. Plant, Cell & Environment 34, 2122–2137. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gibbon D, Dixon J, Flores Velazquez D. 2007. Beyond drought tolerant maize: study of additional priorities in maize. Report to Generation Challenge Program. 1–42. [Google Scholar]

- Girardin P, Morel-fourrier B, Jordan M, et al. 1987. Développement des racines adventives chez le maïs. Agronomie 7, 353–360. [Google Scholar]

- Hirel B, Tétu T, Lea PJ, Dubois F. 2011. Improving nitrogen use efficiency in crops for sustainable agriculture. Sustainability 3, 1452–1485. [Google Scholar]

- Hochholdinger F, Woll K, Sauer M, Dembinsky D. 2004. Genetic dissection of root formation in maize (Zea mays) reveals root-type specific developmental programmes. Annals of Botany 93, 359–368. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hoppe DC, McCully ME, Wenzel CL. 1986. The nodal roots of Zea: their development in relation to structural features of the stem. Canadian Journal of Botany 64, 2524–2537. [Google Scholar]

- Jordan MO, Harada J, Bruchou C, Yamazaki K. 1993. Maize nodal root ramification: absence of dormant primordia, root classification using histological parameters and consequences on sap conduction. Plant and Soil 153, 125–143. [Google Scholar]

- Lea PJ, Azevedo RA. 2006. Nitrogen use efficiency. 1. Uptake of nitrogen from the soil. Annals of Applied Biology 149, 243–247. [Google Scholar]

- Lewis AM, Boose ER. 1995. Estimating volume flow rates through xylem conduits. American Journal of Botany 82, 1112–1116. [Google Scholar]

- Li P, Zhuang Z, Cai H, Cheng S, Soomro AA, Liu Z, Gu R, Mi G, Yuan L, Chen F. 2016. Use of genotype–environment interactions to elucidate the pattern of maize root plasticity to nitrogen deficiency. Journal of Integrative Plant Biology 58, 242–253. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu S, Song F, Liu F, Zhu X, Xu H. 2012a. Effect of planting density on root lodging resistance and its relationship to nodal root growth characteristics in maize (Zea mays L.). Journal of Agricultural Science 4, 182. [Google Scholar]

- Liu S, Song F, Zhu X, Xu H. 2012b. Dynamics of root growth and distribution in maize from the black soil region of NE China. Journal of Agricultural Science 4, 21–30. [Google Scholar]

- Lynch JP. 2013. Steep, cheap and deep: an ideotype to optimize water and N acquisition by maize root systems. Annals of Botany 112, 347–357. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lynch JP. 2015. Root phenes that reduce the metabolic costs of soil exploration: opportunities for 21st century agriculture. Plant, Cell & Environment 38, 1775–1784. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lynch JP. 2018. Rightsizing root phenotypes for drought resistance. Journal of Experimental Botany 69, 3279–3292. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mano Y, Omori F, Takamizo T, Kindiger B, Bird RMK, Loaisiga CH. 2006. Variation for root aerenchyma formation in flooded and non-flooded maize and teosinte seedlings. Plant and Soil 281, 269–279. [Google Scholar]

- Meister R, Rajani MS, Ruzicka D, Schachtman DP. 2014. Challenges of modifying root traits in crops for agriculture. Trends in Plant Science 19, 779–788. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miguel MA, Postma JA, Lynch JP. 2015. Phene synergism between root hair length and basal root growth angle for phosphorus acquisition. Plant Physiology 167, 1430–1439. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moll RH, Kamprath EJ, Jackson WA. 1982. Analysis and interpretation of factors which contribute to efficiency of nitrogen utilization. Agronomy Journal 74, 562–564. [Google Scholar]

- Navarro D. 2015. Learning statistics with R: a tutorial for psychology students and other beginners (Version 0.5). http://www.fon.hum.uva.nl/paul/lot2015/Navarro2014.pdf [Google Scholar]

- Nobel PS. 2006. Plants and fluxes. In: Physicochemical and environmental plant physiology. London: Academic Press, 438–505. [Google Scholar]

- Paez-Garcia A, Motes C, Scheible W-R, Chen R, Blancaflor E, Monteros M. 2015. Root traits and phenotyping strategies for plant improvement. Plants 4, 334–355. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pellerin S. 1994. Number of maize nodal roots as affected by plant density and nitrogen fertilization: relationships with shoot growth. European Journal of Agronomy 3, 101–110. [Google Scholar]

- Pinheiro J, Bates D, DebRoy S, Sarkar D, Team RC. 2018. nlme: linear and nonlinear mixed effects models. R package version 3.1-137. https://CRAN.R-project.org/package=nlme. [Google Scholar]

- Prince SJ, Murphy M, Mutava RN, Durnell LA, Valliyodan B, Shannon JG, Nguyen HT. 2017. Root xylem plasticity to improve water use and yield in water-stressed soybean. Journal of Experimental Botany 68, 2027–2036. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Postma JA, Dathe A, Lynch J. 2014. The optimal lateral root branching density for maize depends on nitrogen and phosphorus availability. Plant Physiology 166, 590–602. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Purushothaman R, Zaman-allah M, Mallikarjuna N, Merr L. 2013. Root anatomical traits and their possible contribution to drought tolerance in grain legumes. 16, 1–8. [Google Scholar]

- Rangarajan H, Postma JA, Lynch JP. 2018. Co-optimization of axial root phenotypes for nitrogen and phosphorus acquisition in common bean. Annals of Botany 122, 485–499. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rasband W. 2015. ImageJ. Bethesda, MD: National Institutes of Health. http://imagej.nih.gov/ij. [Google Scholar]

- R Core Team . 2016. R: a language and environment for statistical computing. Vienna, Austria: R Foundation for Statistical Computing. [Google Scholar]

- Richards RA, Passioura J. 1989. A breeding program to reduce the diameter of the major xylem vessel in the seminal roots of wheat and its effect on grain yield in rain-fed environments. Crop and Pasture Science 40, 943–950. [Google Scholar]

- Saengwilai P, Nord EA, Chimungu JG, Brown KM, Lynch JP. 2014. Root cortical aerenchyma enhances nitrogen acquisition from low-nitrogen soils in maize. Plant Physiology 166, 726–735. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schmidt JE, Gaudin ACM. 2017. Toward an integrated root ideotype for irrigated systems. Trends in Plant Science 22, 433–443. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schneider HM, Lynch JP. 2018. Functional implications of root cortical senescence for soil resource capture. Plant and Soil 423, 13–26. [Google Scholar]

- Schneider HM, Postma JA, Wojciechowski T, Kuppe C, Lynch J. 2017a. Root cortical senescence improves barley growth under suboptimal availability of nitrogen, phosphorus, and potassium. Plany Physiology 174, 2333–2347. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schneider HM, Wojciechowski T, Postma JA, Brown KM, Lücke A, Zeisler V, Schreiber L, Lynch JP. 2017b. Root cortical senescence decreases root respiration, nutrient content and radial water and nutrient transport in barley. Plant, Cell & Environment 40, 1392–1408. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stamp P, Kiel C. 1992. Root morphology of maize and its relationship to root lodging. Journal of Agronomy and Crop Science 168, 113–118. [Google Scholar]

- Striker GG, Insausti P, Grimoldi AA, Vega AS. 2007. Trade-off between root porosity and mechanical strength in species with different types of aerenchyma. Plant, Cell & Environment 30, 580–589. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Strock CF, Morrow de la Riva L, Lynch JP. 2018. Reduction in root secondary growth as a strategy for phosphorus acquisition. Plant Physiology 176, 691–703. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tang Y, Horikoshi M, Li W. 2016. ggfortify: unified interface to visualize statistical result of popular R packages. The R Journal 8.2, 478–489. [Google Scholar]

- Trachsel S, Kaeppler SM, Brown KM, Lynch JP. 2011. Shovelomics: high throughput phenotyping of maize (Zea mays L.) root architecture in the field. Plant and Soil 341, 75–87. [Google Scholar]

- Trachsel S, Kaeppler SM, Brown KM, Lynch JP. 2013. Maize root growth angles become steeper under low N conditions. Field Crops Research 140, 18–31. [Google Scholar]

- Wahl S, Ryser P, Edwards PJ. 2001. Phenotypic plasticity of grass root anatomy in response to light intensity and nutrient supply. Annals of Botany 88, 1071–1078. [Google Scholar]

- Wei T, Simko V. 2017. R package ‘corrplot’: visualization of a correlation matrix (Version 0.84). https://cran.r-project.org/web/packages/corrplot/corrplot.pdf [Google Scholar]

- Weiner J. 2004. Allocation, plasticity, and allometry in plants. Perspectives in Plant Ecology, Evolution and Systematics 6, 207–215. [Google Scholar]

- Wickham H. 2011. The split–apply–combine strategy for data analysis. Journal of Statistical Software 40, 1–29. [Google Scholar]

- Wickham H. 2016. ggplot2: elegant graphics for data analysis. New York: Springer-Verlag. [Google Scholar]

- Wilhelm WW, McMaster GS. 1995. Importance of the phyllochron in studying development and growth in grasses. Crop Science 35, 1–3. [Google Scholar]

- Xu G, Fan X, Miller AJ. 2012. Plant nitrogen assimilation and use efficiency. Annual Review of Plant Biology 63, 153–182. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yamazaki K, Kaeriyama N. 1982. The morphological characters and the growing directions of primary roots of corn plants. Japanese Journal of Crop Science 51, 584–590. [Google Scholar]

- York LM, Galindo-Castañeda T, Schussler JR, Lynch JP. 2015. Evolution of US maize (Zea mays L.) root architectural and anatomical phenes over the past 100 years corresponds to increased tolerance of nitrogen stress. Journal of Experimental Botany 66, 2347–2358. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- York LM, Lynch JP. 2015. Intensive field phenotyping of maize (Zea mays L.) root crowns identifies phenes and phene integration associated with plant growth and nitrogen acquisition. Journal of Experimental Botany 66, 5493–5505. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- York LM, Nord EA, Lynch JP. 2013. Integration of root phenes for soil resource acquisition. Frontiers in Plant Science 4, 355. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yu P, Baldauf JA, Lithio A, Marcon C, Nettleton D, Li C, Hochholdinger F. 2016. Root type-specific reprogramming of maize pericycle transcriptomes by local high nitrate results in disparate lateral root branching patterns. Plant Physiology 170, 1783–1798. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.