Abstract

Unlike animal cells, plant cells do not possess centrosomes that serve as microtubule organizing centers; how microtubule arrays are organized throughout plant morphogenesis remains poorly understood. We report here that Arabidopsis INCREASED PETAL GROWTH ANISOTROPY 1 (IPGA1), a previously uncharacterized microtubule-associated protein, regulates petal growth and shape by affecting cortical microtubule organization. Through a genetic screen, we showed that IPGA1 loss-of-function mutants displayed a phenotype of longer and narrower petals, as well as increased anisotropic cell expansion of the petal epidermis in the late phases of flower development. Map-based cloning studies revealed that IPGA1 encodes a previously uncharacterized protein that colocalizes with and directly binds to microtubules. IPGA1 plays a negative role in the organization of cortical microtubules into parallel arrays oriented perpendicular to the axis of cell elongation, with the ipga1-1 mutant displaying increased microtubule ordering in petal abaxial epidermal cells. The IPGA1 family is conserved among land plants and its homologs may have evolved to regulate microtubule organization. Taken together, our findings identify IPGA1 as a novel microtubule-associated protein and provide significant insights into IPGA1-mediated microtubule organization and petal growth anisotropy.

Keywords: Arabidopsis, cortical microtubule, growth anisotropy, INCREASED PETAL GROWTH ANISOTROPY 1 (IPGA1), microtubule-associated protein, petal

Arabidopsis IPGA1 is a previously uncharacterized microtubule-associated protein that functions in modulating cell and petal shape through its effect on cortical microtubule organization in abaxial petal epidermal cells.

Introduction

How gene activities are translated into morphology is a central and yet unresolved question in biology. Plant organs such as leaves and petals have through evolution attained numerous morphologies, most of which are generated by spatially non-uniform growth, termed growth anisotropy (Baskin et al., 1999; Coen et al., 2004; Baskin, 2005). Growth of species-specific organs, such as petals, is highly consistent in individuals grown under the same environmental conditions. This indicates that precise genetic controls are applied to coordinate intrinsic growth and developmental signals with environmental cues to enable organ growth to a final characteristic shape (Breuninger and Lenhard, 2010; Czesnick and Lenhard, 2015). In the model plant Arabidopsis, considerable progress has been made over the past two decades toward understanding the molecular mechanisms controlling organ growth and morphogenesis (Uyttewaal et al., 2010; González and Inzé, 2015; Huang and Irish, 2016), yet our knowledge of the genetic regulatory networks of plant organ shape control at the cellular level remains limited.

Plant organ growth and final shape are determined by the tight coordination of cell proliferation and subsequent cell expansion (Gonzalez et al., 2012; Powell and Lenhard, 2012). The directed regulation of anisotropic cell expansion is a process critical for the visible growth of plant organs. Anisotropic cell expansion and final cell shape are largely influenced by the property of cell-wall anisotropy, which is correlated with the orientation of cellulose microfibrils (Green, 1962; Baskin 2001, 2005; Wasteneys, 2004; Smith and Oppenheimer, 2005; Crowell et al., 2010). The deposition of cellulose microfibrils is under the control of cortical microtubules, which play a critical role in recruiting cellulose synthase (CESA)-containing vesicles and guiding the trajectory of CESA complexes (Paredez et al., 2006; Lloyd and Chan, 2008; Crowell et al., 2009; Gutierrez et al., 2009; Lloyd, 2011; Lei et al., 2014). Thus, the organization of cortical microtubule arrays in plant cells primarily functions in the deposition of cellulose microfibrils, which in turn determines cell-wall anisotropy and cell expansion. Consistently, disruption of microtubule arrays by microtubule-depolymerizing agents, such as oryzalin, suppresses anisotropic cell expansion and leads to isotropic cell swelling (Baskin et al., 1994; Sugimoto et al., 2003). Notably, evidence demonstrates that cortical microtubules act as sensors or transducers of mechanical cues that regulate growth and cell shape (Landrein and Hamant, 2013; Sampathkumar et al., 2014).

Live-cell imaging studies have demonstrated that the dynamic features of cortical microtubules, including treadmilling, branching, and severing, enable microtubules to self-organize into diverse arrays (Wasteneys and Ambrose, 2009; Fishel and Dixit, 2013; Shaw, 2013). Genetic and live imaging studies have shown that microtubule-associated proteins (MAPs) together with environmental and endogenous cues play important roles in the regulation of the dynamics and organization of cortical microtubules (Le et al., 2005; Sedbrook and Kaloriti, 2008; Polko et al., 2012; Wang et al., 2012; Lindeboom et al., 2013; Hamada, 2014; Chen et al., 2016; Lian et al., 2017). A large number of Arabidopsis mutants have been shown to display altered microtubule organization, accompanied by defects in anisotropic cell expansion and developmental defects including twisted growth patterns (Thitamadee et al., 2002; Shoji et al., 2004; Ambrose et al., 2007; Korolev et al., 2007; Wang et al., 2007; Buschmann et al., 2009; Fu et al., 2009; Nakamura and Hashimoto, 2009; Oda and Fukuda, 2012; Hamada et al., 2013; Tian et al., 2015; Bhaskara et al., 2017; Sasaki et al., 2017). Despite this progress, the molecular mechanisms underlying cortical microtubule behaviors have remained incompletely understood, and it is possible that previously uncharacterized MAPs also participate in cortical microtubule organization during plant growth and development.

Arabidopsis petals have been used as a model system to study the molecular and genetic mechanisms underlying cell expansion and organ shape (Huang and Irish, 2016). Petal growth and final shape formation rely on cell proliferation during early developmental stages but growth and shape are largely regulated by cell expansion during the late phases of flower development (Hill and Lord, 1989; Smyth et al., 1990). Elegant molecular and genetic work has identified key regulators of petal growth and development (Dinneny et al., 2004; Takeda et al., 2004; Szécsi et al., 2006; Nag et al., 2009; Varaud et al., 2011; Sauret-Güeto et al., 2013; Fujikura et al., 2014; Schiessl et al., 2014; Huang and Irish, 2015; Ren et al., 2016; Saffer et al., 2017; van Es et al., 2018). Nevertheless, how the petal grows into its final characteristic morphology based on anisotropic cell expansion during late flower developmental stages remains largely unclear (Varaud et al., 2011; Ren et al., 2016).

Insights into the molecular and genetic control of growth anisotropy and organ shape have been gained from the analyses of Arabidopsis mutants. For example, JAGGED, which encodes a zinc finger transcription factor, functions in the distal region of the petal to control anisotropic growth (Sauret-Güeto et al., 2013; Schiessl et al., 2014). Loss of function of AN, which is a homolog of mammalian C-terminal binding protein (CtBP)/brefeldin aribosylated substrate (BARS) (Folkers et al., 2002; Kim et al., 2002), leads to a narrow-leaf phenotype owing to a decreased ratio of growth in width relative to growth in length (Tsuge et al., 1996). The an mutants have reduced cell expansion in the leaf-width direction, which correlates with well-ordered cortical microtubule arrays (Kim et al., 2002). Arabidopsis genes LONGIFOLIA1 and LONGIFOLIA2 are responsible for regulating the growth anisotropy of various aerial parts, including leaves, flowers, and siliques (Lee et al., 2006). It has been reported that numerous MAPs, such as MT nucleating proteins (Walia et al., 2014), IQD proteins (Bürstenbinder et al., 2017; Liang et al., 2018), and TRM proteins (Drevensek et al., 2012), function in regulating growth anisotropy in plants. Despite these findings, regulators that function in modulating cell expansion and anisotropic organ growth remain largely unknown.

In this study, through a genetic screen for mutants with abnormal petal shape, we identified INCREASED PETAL GROWTH ANISOTROPY1 (IPGA1) as a previously uncharacterized microtubule-associated protein. Our results demonstrate that IPGA1 negatively regulates petal anisotropic growth, correlating with changes in microtubule ordering and anisotropic cell expansion.

Materials and methods

Plant material and growth conditions

Arabidopsis Columbia-0 (Col-0) was used as the wild-type (WT) ecotype in this study. T-DNA insertion mutants ipga1-2 (SALK_137332C) and ipga1-3 (SAIL_523_C10) were obtained from the Arabidopsis Biological Resource Centre (ABRC) (https://abrc.osu.edu/). Seeds were surface-sterilized in 70% ethanol for 1 min followed by incubation in 1.5% sodium hypochlorite, 0.05% Tween-20 for 10 min, and immediately rinsed with H2O. Sterilized seeds were stratified for 2 d at 4 °C in the dark to obtain synchronous germination. Seedlings were grown on Murashige and Skoog (MS) agar medium for 8 d and then transferred to soil. Plants were grown in a walk-in growth chamber at 22 °C with a 16 h day/8 h dark cycle and 60–70% relative humidity under cool white fluorescent tubes.

Mutant screening and map-based cloning

Approximately 5000 seeds of Col-0 were mutagenized using ethyl methane sulfonate. M2 seeds were harvested from self-fertilized M1 plants individually, and M2 lines were screened for increased petal anisotropic shapes compared with WT. Candidate mutants were backcrossed to WT at least three times before being further analysed. For map-based cloning, the ipga1-1 mutant line was crossed with WT Arabidopsis ecotype Landsberg erecta. Eight hundred F2 plants showing mutant phenotypes were selected for genetic mapping. Genomic DNA of these plants was isolated and used for PCR with simple sequence length polymorphism (SSLP) markers. The information on the SSLP markers used in this study is based on the Arabidopsis mapping platform database (http://amp.genomics.org.cn/). The mutation was first mapped to chromosome 4 between markers FCA and T15N24. For fine mapping, the markersT6K21, T9A21, F28A21, T5K18, and F1C12 were used to narrow down the mutation near to the BAC F28A21 site. The sequencing of candidate genes revealed a single nucleotide G-to-A mutation in codon 467 (TGG/TGA) of At4g18570, generating a premature stop codon. The primers used are listed in Supplementary Table S1 at JXB online.

DNA constructs and generation of transgenic plants

The sequences of primers used in this study are provided in Supplementary Table S1. For transient expression analysis of IPGA1, the coding sequence of IPGA1 was PCR-amplified and cloned into pGWB plasmid, generating 35S::GFP-IPGA1. In addition, the coding sequence of IPGA1 was PCR-amplified and cloned into a Ti plasmid (pFGFP) modified from pCambia3301 using the In-Fusion cloning method (Clontech), resulting in expression of green fluorescent protein (GFP)–IPGA1 driven by the Arabidopsis ACTIN2 promoter (pACT2::GFP-IPGA1). The ACTIN2 promoter was replaced by a 2136-bp fragment of the IPGA1 promoter to generate the pIPGA1::IPGA1-GFP construct for transient expression analysis of IPGA1. For the ipga1-1 complementation experiment, the pACT2::GFP-IPGA1 construct was introduced into ipga1 mutant plants. To generate IPGA1pro::GUS lines, the 2136-bp fragment of the IPGA1 promoter region was PCR-amplified and cloned into the Ti plasmid pCambia1391 with the In-Fusion cloning method.

Confocal laser scanning microscopy

For confocal imaging of petal epidermal cells, samples were stained with a solution containing 50 μg ml−1 propidium iodide for 1 h. Petal epidermal cells were imaged with a Zeiss LSM 880 confocal laser scanning microscope (excitation at 514 nm, emission 550–700 nm). For live-confocal imaging of cortical microtubules, cells stably expressing GFP-TUA6 were imaged using a Zeiss LSM 880 confocal laser scanning microscope (excitation at 488, emission 500–570 nm). Serial optical sections were taken at 0.5 μm increments with a ×40 water or ×63 oil lens, and then projected on a plane (i.e. maximum intensity) using Zeiss LSM 880 software.

Fluorescence recovery after photobleaching analysis

Fluorescence recovery after photobleaching (FRAP) was performed using a Leica TCS SP8 confocal laser scanning microscope equipped with a 488 nm laser. FRAP was observed in Arabidopsis cotyledon pavement cells transiently expressing IPGA1–GFP. In the FRAP experiments, 190×90 pixel areas including microtubules were bleached for 7.8 s, and the images of fluorescence recovery were collected every 3 s. The t1/2 was calculated as described previously (Chang et al., 2005).

Microtubule co-sedimentation assay

Porcine brain tubulin was purified as described previously (Castoldi and Popov, 2003). The pET30a(+):IPGA1 (full length coding sequence) and pET30a(+):IPGA1 (1–220 aa) constructs were generated and transformed into the Escherichia coli strain BL21 (DE3). The recombinant protein, His–IPGA1, was purified with a nickel-nitrilotriacetic acid column (Qiagen) equilibrated with the elution buffer (50 mM NaH2PO4, 300 mM NaCl, and 250 mM imidazol, pH 8.0). Recombinant protein samples were analysed by SDS-PAGE and western blotting with an anti-His antibody. The microtubule polymerization and co-sedimentation assay was performed as described previously (Mao et al., 2005). For the microtubule co-sedimentation assay of IPGA1 proteins, 2.5 μM His–IPGA1 proteins were added to taxol-stabilized microtubules (5 μM porcine brain tubulin) in PEMT buffer (100 mM PIPES, 1 mM EGTA, 1 mM MgCl2, and 20 µM taxol, pH 6.9). After incubation at 25 °C for 30 min, samples were centrifuged at 100 000 g at 25 °C for 20 min. Pellets were analysed by 12% SDS-PAGE, and then visualized by staining the protein gels with Coomassie Brilliant Blue R-250. His-MAP65-1 and BSA were used as positive and negative controls, respectively.

Statistical analysis

Student’s t-test was performed whenever two groups of data were compared. Data are presented as the mean ±SEM from at least three independent experiments.

Results

Isolation of a novel petal mutant with increased growth anisotropy

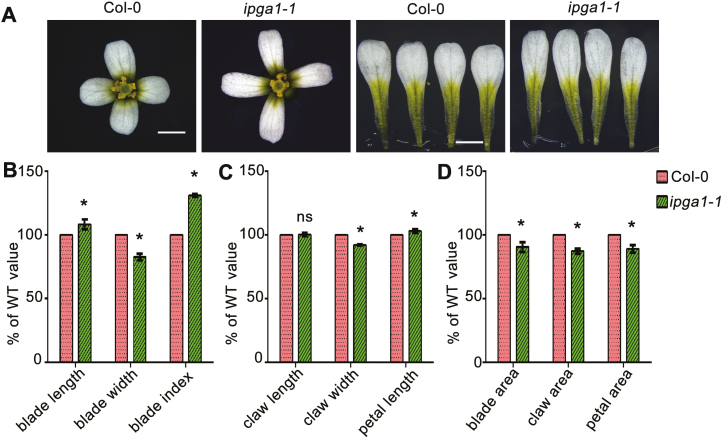

To identify new genes involved in regulating petal growth and shape, we performed a forward genetic screen for Arabidopsis mutants with abnormal petal morphology. We mutagenized wild-type (WT) Colombia-0 (Col-0) seeds with ethyl methanesulfonate (EMS) and screened more than 2000 M2 independent lines. From this screen, we identified one mutant that displayed a phenotype of increased petal growth anisotropy compared with the WT, and thus was named ipga1-1. The ipga1-1 mutant was introduced into the Col-0 background through three rounds of backcrossing, and was then used for further phenotypic analyses. Compared with WT, ipga1-1 mutant plants produced narrower and longer petals (Fig. 1A–D), resulting in an increased petal blade index (Fig. 1B), the ratio of length to width, which is used to describe petal shape (Fujikura et al., 2014). The ipga1-1 mutant also displayed a significant decrease in petal area (Fig. 1D). In addition, ipga1-1 plants had reduced petal claw width but petal claw length was the same as WT (Fig. 1C), leading to an overall decreased petal claw area in ipga1-1 (Fig. 1D).

Fig. 1.

Phenotypic analysis of the ipga1-1 mutant. (A) Mature flowers and petals from WT (Col-0) and the ipga1-1 mutant. The ipga1-1 mutant had longer and narrower petals than the WT. Scale bars: 1 mm. (B–D) Quantification of petal parameters of Col-0 and ipga1-1. Values are mean ±SD of 80 petals of 20 flowers from six plants. Asterisks indicate a significant difference (*P<0.05, Student’s t-test). n.s. indicates no significant difference (P>0.05, Student’s t-test).

Map-based cloning and characterization of two IPGA1 T-DNA insertion alleles

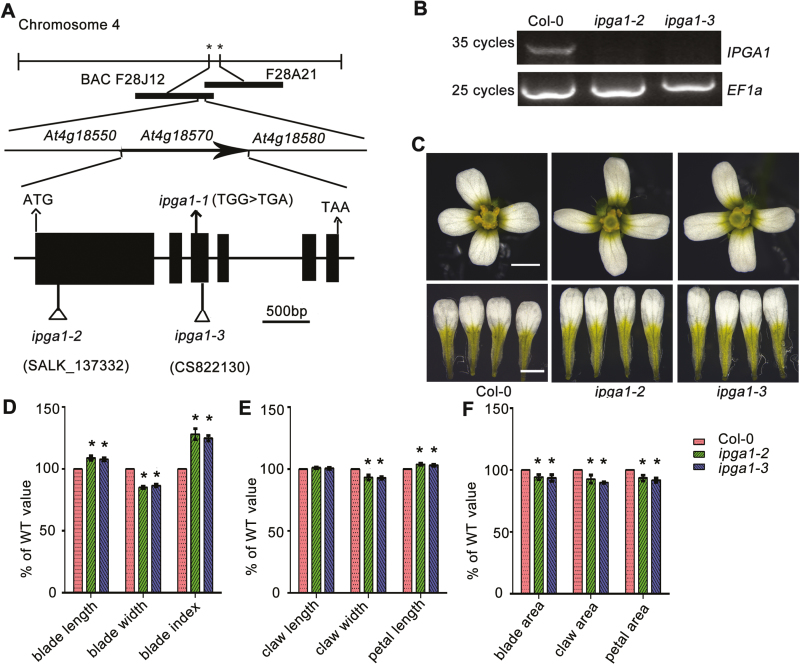

We used a map-based cloning approach to identify the ipga1-1 mutation site. An F2 population resulting from a cross between ipga1-1 and Landsberg erecta was used to map the ipga1-1 mutation. The causative gene was mapped to the 19 kb interval between markers F28J12 and F28A21 on chromosome 4 (Fig. 2A). DNA sequencing revealed that the ipga1-1 mutant had a single nucleotide G-to-A mutation in codon 467 (TGG/TGA) of the At4g18570 gene, resulting in a premature stop codon (Fig. 2A). To further investigate the role of IPGA1 in regulating petal shape, we isolated two T-DNA insertion mutants, ipga1-2 (SALK_137332C) and ipga1-3 (SAIL_523_C10), which were identified with T-DNA insertions in the first and third exon of the At4g18570 gene, respectively (Fig. 2A). We next investigated the expression of the IPGA1 full-length mRNA in ipga1-2 and ipga1-3, and found that the expression of IPGA1 was barely detectable (Fig. 2B), suggesting that these two mutants could be loss-of-function alleles. Similarly to ipga1-1, both ipga1-2 and ipga1-3 exhibited narrower and longer petals, as well as increased petal index compared with WT (Fig. 2C–F). We next crossed ipga1-1 with T-DNA mutant alleles ipga1-2 and ipga1-3, and found that the F1 hybrid petals were narrow and long similarly to ipga1 mutants (see Supplementary Fig. S1). This result implied that the ipga1-1 mutant is allelic to the IPGA1 gene’s T-DNA mutant alleles. Furthermore, the identity of the IPGA1 gene was verified by genetic complementation analysis (Supplementary Fig. S2). These results demonstrate that At4g18570 is the causative gene for the ipga1-1 phenotype.

Fig. 2.

Identification and characterization of IPGA1. (A) Schematic representation of the IPGA1 (At4g18570) gene, showing the nature and position of the ipga1 mutant alleles. Map-based cloning demonstrated that the igpa1-1 mutation carries a single nucleotide G-to-A mutation in codon 467 (TGG/TGA) of At4g18570 generating a premature stop codon. Black rectangles represent coding regions, and the black lines represent introns. Arrows indicate nucleotide substitutions, and triangles indicate T-DNA insertions. (B) RT-PCR monitoring of IPGA1 mRNA levels in Col-0, ipga1-2, and ipga1-3. EF1a mRNA was used as a control. (C) Mature flowers and petals from plants of the indicated genotypes. The petals from ipga1-2 and ipga1-3 displayed a longer and narrower shape compared with Col-0. Scale bars: 1 mm. (D–F) Quantification of petal parameters of Col-0, ipga1-2, and ipga1-3. Values are mean ±SD of 80 petals from 20 flowers from more than six plants. Asterisk indicates significant difference (*P<0.05, Student’s t-test).

IPGA1 function is required in the late phases of petal development to limit anisotropic cell expansion

We next investigated when the petal phenotype observed in the ipga1 mutants first occurs during flower development. Morphological events of Arabidopsis petal development are well characterized; they consist of early stages of growth (stages 5–9) regulated by cell division, and later phases (stage 9 up to stage 14) controlled predominantly by post-mitotic cell expansion (Hill and Lord, 1989; Smyth et al., 1990). WT petals display an anisotropic shape from the earliest stages and become increasingly anisotropic at later developmental stages (Sauret-Güeto et al., 2013). We compared petal phenotypes between WT and the IPGA1 loss-of-function mutants at developmental stages 8–14. Petal blade length and width at developmental stage 8 in the ipga1 mutants were comparable to those of the WT (see Supplementary Fig. S3). However, at development stage 10 and beyond, the ipga1 mutants displayed an increased anisotropic shape, with significantly longer and narrower petals, and increased petal blade index compared with the WT (Supplementary Fig. S3). Taken together, these results suggest that IPGA1 participates in the inhibition of the anisotropic petal shape during late development stages.

Next, we examined whether the petal phenotype observed in the ipga1 mutants was associated with alterations in cell proliferation and/or cell expansion. By analysing total cell numbers in the epidermis of petal blades of WT, ipga1-1, and ipga1-2, we found no significant difference between WT and mutants (see Supplementary Fig. S4A–C). Furthermore, we used 5-ethynyl-2′-deoxyuridine (EdU) staining to monitor cell division activity in petals. EdU is used to mark cell division in the root cells since incorporation of this chemical in the nuclei is indicative of S-phase entry of the cell cycle (Vanstraelen et al., 2009). No significant differences in fluorescence signals were found between WT and mutant petals (Supplementary Fig. S4D, E), suggesting that cell proliferation is not altered in ipga1 mutants.

Given that a previous report demonstrated that alternations in cell shape contribute to petal anisotropic growth, particularly at later developmental stages when cell division rates decrease (Sauret-Güeto et al., 2013), we next examined whether defects in epidermal cell shape could explain the phenotype of longer and narrower petals observed in ipga1-1. Indeed, analysis of abaxial epidermal cells in the distal region of the petal blades showed that ipga1-1 cells increased in length at stage 10 and beyond, and decreased in width at stage 9 and beyond (Fig. 3), resulting in an increased cell index (the ratio of length to width) from stages 9 to 14 (Fig. 3D). Moreover, analysis of abaxial epidermal cells in the middle region of the petal blades demonstrated that increases in length at stage 14 and decreases in width at stage 9 and beyond led to an increased cell index from stages 9 to 14 (see Supplementary Fig. S5). These results suggested that the more elongated petals observed in the ipga1-1 mutant were mainly attributable to the function of IPGA1 in the distal region of the petal blades.

Fig. 3.

IPGA1 functions as a negative regulator in modulating anisotropic cell expansion at late stages. (A) Cells from the top regions of petal abaxial epidermis of Col-0 and ipga1-1 throughout developmental stages 8–14. Scale bar: 20 µm. (B–E) Quantification of cell parameters of Col-0 and ipga1-1 from the indicated developmental stages. (B) Cell length. (C) Cell width. (D) Cell index, calculated by length divided by width. (E) Cell area. Values are mean ±SD of more than 600 cells of six petals from six plants. Asterisks indicate a significant difference (**P<0.01, Student’s t-test). n.s. indicates no significant difference (P>0.05).

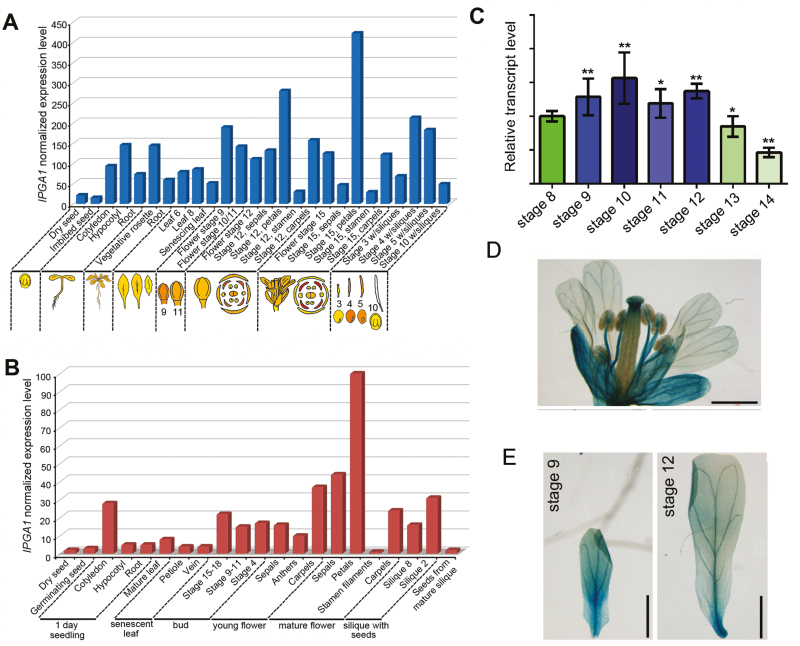

We next analysed IPGA1 (At4g18570) mRNA expression profiles based on information from publicly available databases, including ATH1 Affimetrix data on the eFP browser (http://bar.utoronto.ca/efp/cgi-bin/efpWeb.cgi;Winter et al., 2007) and RNA-seq data at TraVA (http://travadb.org/;Klepikova et al., 2016). As shown in Fig. 4A, B, the IPGA1 gene is ubiquitously expressed across plant developmental stages, with its highest expression levels occurring in petals during late developmental stages. Furthermore, the RT-PCR assays supported the notion that IPGA1 exhibited high expression levels in petals at late developmental stages (Fig. 4C). Analysis of IPGA1pro:GUS plants expressing the GUS reporter under the control of a 2136-bp fragment of the IPGA1 promoter region revealed that GUS signals were detected in the floral organs including in developing petals (Fig. 4D, E). These results are in agreement with the role of IPGA1 in petal development.

Fig. 4.

Expression patterns of IPGA1. (A, B) IPGA1 mRNA expression levels through plant development. Data were collected from publicly available databases at (A) eFP browser (microarray) and (B) TRAVAdb (RNA-seq). (C) qRT-PCR monitoring of IPGA1 mRNA levels throughout petal development stages 8–14. Petals from various developmental stages were used for reverse transcription (*P<0.05, **P<0.01, Student’s t-test). (D, E) IPGA1 was expressed in developing petals. Histochemical GUS staining of inflorescence (D) and petals (E) from a representative proIPGA1:GUS transgenic line. Scale bars: 1 mm.

IPGA1 is colocalized with cortical microtubules and binds directly to microtubules

IPGA1 encodes a 642-amino-acid protein of unknown function. We next searched homologs of the IPGA1 protein in the TAIR database. However, no sequences similar to the full-length IPGA1 sequence were found. Interestingly, there are three genes (AT3G25690, AT1G07120, and AT1G48280) that encode proteins strikingly similar to the C-terminal region of IPGA1 (see Supplementary Fig. S6). The functions of these genes are not clear, although the AT3G25690 gene that encodes CHLOROPLAST UNUSUAL POSITIONING (CHUP1) that contains multiple domains has been reported, and it was shown to be required for organelle positioning and movement (Oikawa et al., 2003). Interestingly, CHUP1 act as a linker between chloroplasts and the actin cytoskeleton (Schmidt von Braun and Schleiff, 2008). AT1G07120 and AT1G48280 were named as IPGA1-LIKE1 (IPGAL1) and IPGAL2, respectively in this study. Motif searches in MEME (http://meme-suite.org/tools/meme) revealed that IPGA1 and the other three proteins, CHUP1, IPGAL1, and IPGAL2, share conserved putative motifs (Supplementary Fig. S7). Interestingly, using the COILS program (Lupas et al., 1991), these four proteins were predicted to have coiled-coil domains (Supplementary Fig. S8).

We next performed a BLAST search in the databases using full-length Arabidopsis IPGA1, and identified orthologs of the IPGA1 protein in Capsella rubella, Brassica rapa, Malus domestica, Glycine max, Sorghum bicolor, and Oryza sativa (see Supplementary Fig. S9), but no orthologs were identified in animals, yeast, or algae. The orthologous proteins have conserved putative motifs very similar to Arabidopsis IPGA1 (Supplementary Fig. S7). This result suggests that the IPGA1 family is conserved among land plants.

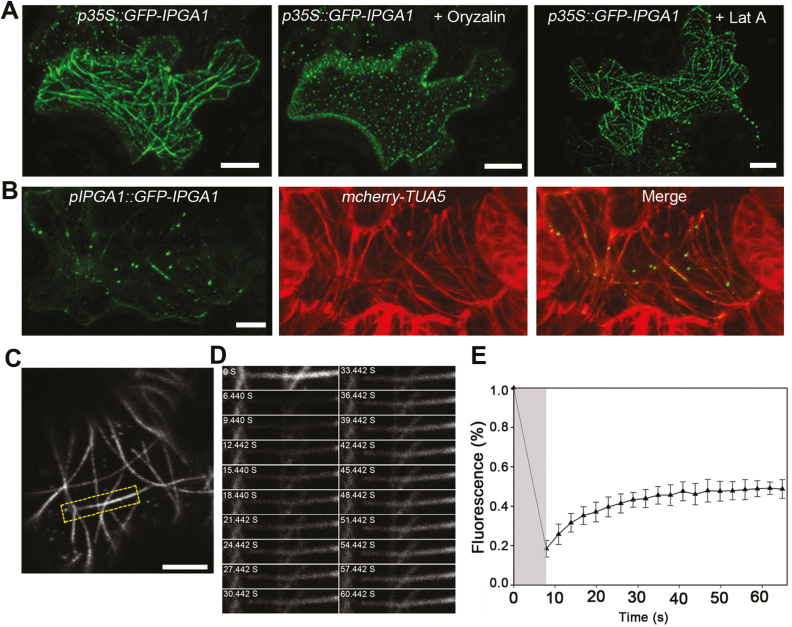

We generated a construct with a 35S promoter-driving IPGA1 fused to GFP, and transformed this construct into WT Arabidopsis cotyledon pavement cells using the FAST technique involving Agrobacterium tumefaciens-mediated transformation of germinating seedlings (Li et al., 2009). Confocal microscopy imaging revealed that GFP–IPGA1 exhibited filamentous structures in all 20 observed cotyledon pavement cells (Fig. 5A). The filament structures were disrupted by treatment with oryzalin (Fig. 5A), a microtubule-disrupting reagent, but the filaments remained intact in the presence of latrunculin A (Lat A) (Fig. 5A), a chemical that de-polymerizes actin filaments, suggesting that the GFP–IPGA1 localization pattern may be associated with microtubules. Furthermore, we used the IPGA1 native promoter-driven GFP–IPGA1 construct to analyse whether IPGA1 was associated with cortical microtubules. The pIPGA1::GFP-IPGA1 construct was transiently expressed in an Arabidopsis transgenic line stably expressing the microtubule marker, a 35S promoter-driven Tubulin5 fused to mCherry (mCherry–TUA5) (Gutierrez et al., 2009). As expected, GFP–IPGA1 exhibited cortical microtubule-like localization in all 20 observed cells, with strong GFP–IPGA1 dots found along the filaments (Fig. 5B). Notably, we observed that the GFP–IPGA1 dots moved along microtubules (see Supplementary Video S1). To further confirm that IPGA1 is localized to cortical microtubules in stable transgenic lines, we generated a construct with IPGA1 tagged with GFP driven by the Arabidopsis ACTIN2 gene’s promoter (pACT2::GFP-IPGA1) and transformed it into the ipga1-2 mutant to generate stable transgenic lines. The defective petal phenotype of the ipga1-2 mutant was fully rescued by the expression of pACT2::GFP-IPGA1 (Supplementary Fig. S10), indicating the fusion protein is functional. We next crossed a pACT2::GFP-IPGA1 ipga1-2 line with the mCherry-TUA5 marker line and analysed the co-localization of GFP–IPGA1 with cortical microtubules. Notably, GFP–IPGA1 co-localized with cortical microtubules in petal epidermal cells (Supplementary Fig. S11), with GFP–IPGA1 dots found along the microtubule filaments.

Fig. 5.

IPGA1 localizes to and directly binds to microtubules. (A) Subcellular localization of GFP–IPGA1. Confocal images of the 35S::GFP-IPGA1 constructs transiently expressing in Col-0 pavement cells. GFP–IPGA1 exhibited filamentous structures in cotyledon pavement cells, and these filamentous structures visualized in this cell were disrupted by oryzalin treatment. Notably, these structures remained intact in the presence of LatA. Scale bars: 10 µm. (B) IPGA1 colocalized with cortical microtubules in Col-0 pavement cells. pIPGA1::GFP-IPGA1 was transiently expressed in cotyledon pavement cells from the microtubule marker line mCherry-TUA5. Scale bar: 10 µm. (C–E) FRAP analysis of GFP–IPGA1. (C) 35S::GFP-IPGA1 signal in the cotyledon pavement cell. The yellow rectangle outlines the photobleached area. Scale bar: 5 µm. (D) Time series of GFP–IPGA1 signal recovery during a FRAP experiment within the area indicated by the rectangle in (C). The numbers show the time in seconds when each of the frames were collected with 0 corresponding to the image before the photobleaching onset and 6.440 just after the photobleaching. (E) Quantification of fluorescence signal. The first FRAP measurement was performed just before the photobleaching and corresponds to point 0. The grey sector indicates the duration of photobleaching, after which 20 images were collected and quantified at approximately 3 s intervals. The fluorescence signals were measured in 20 cells and expressed as the mean percentage of the signal before photobleaching. The error bars represent the SD.

The above findings raised the question of whether IPGA1 could directly bind microtubules. To test this hypothesis, we purified hexa-histidine (His)-fused IPGA1 protein from Escherichia coli for in vitro microtubule co-sedimentation assays, and found that the recombinant His–IPGA1 could bind paclitaxel-stabilized microtubules in vitro (see Supplementary Fig. S12). Furthermore, we performed FRAP analysis to verify the dynamics of IPGA1’s interaction with microtubules in cotyledon pavement cells by transiently expressing GFP–IPGA1. It has been reported that the fluorescence recovery rate after photobleaching reflects the dissociation rate of the protein from microtubules (Bulinski et al., 2001), and that the average 50% recovery time of known MAPs is less than 9 s, for example GFP–AtMAP65-1 (5.93 s), NtMAP65-1a (6.95 s), MIDD1 (8.68 s), and CORD1 (7.90 s) (Chang et al., 2005; Sasaki et al., 2017). We were thus able to assess whether IPGA1 binds microtubules by comparing the fluorescence recovery rate of GFP–IPGA1 with that of the published MAPs. The selected region of a cotyledon pavement cell expressing GFP–IPGA1 (outlined as a yellow rectangle in Fig. 5C) was bleached for approximately 7 s, and was used for the analysis of rapid recovery of GFP–IPGA1 fluorescence after photobleaching. We demonstrated that the average 50% recovery time of GFP–IPGA1 was about 8.18 s (n=28 microtubules) (Fig. 5D, E; Supplementary Video S2). This value is similar to the 50% recovery time of known MAPs such as MIDD1, indicating that IPGA1 binds microtubules directly. Taken together, our results demonstrate that IPGA1 is a novel MAP.

To investigate whether other IPGA family proteins, including IPGA1L1 and IPGA1L2, also associate with cortical microtubules, we observed the localization of GFP-tagged proteins expressed under the control of 35S promoter in Arabidopsis epidermal cells. Interestingly, both IPGA1L1 and IPGA1L2 localized to cortical microtubule arrays in all of 20 observed cells (see Supplementary Fig. S13). Our results demonstrated that IPGA1, IPGAL1, and IPGAL2 proteins associate with cortical microtubules. Therefore, we have demonstrated that IPGA proteins represent a previously unidentified small MAP family.

IPGA1 regulates cortical microtubule organization

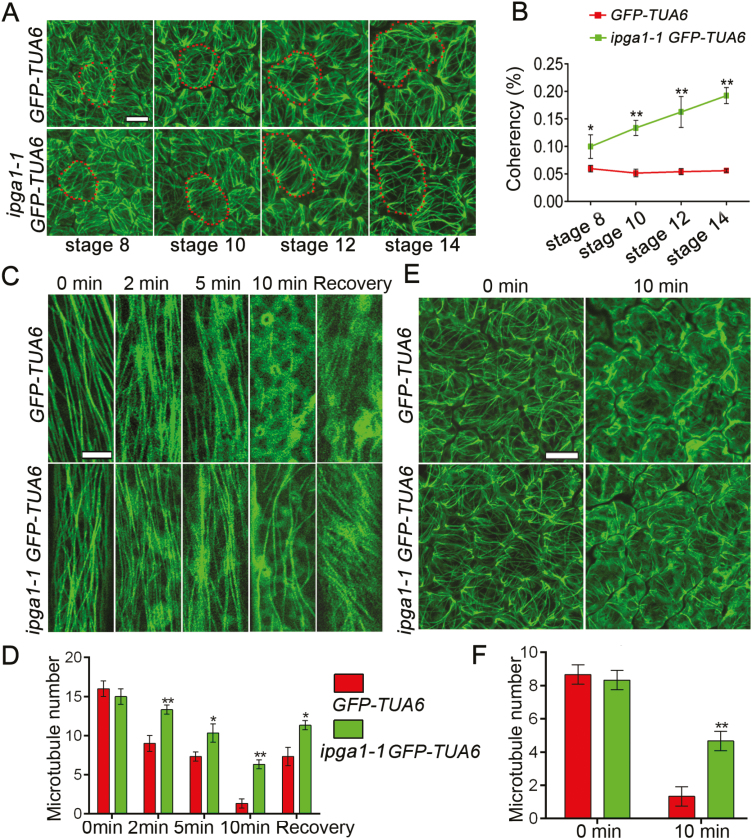

Given that the above findings show that IPGA1 was associated with cortical microtubules and that the abaxial epidermal cells of ipag1-1 had reduced interdigitated growth, with fewer lobes, compared with the WT, we predicted that loss of IPGA1 function would alter the organization of cortical microtubule arrays in abaxial petal epidermal cells. We examined the patterns of cortical microtubule organization by using a transgenic line expressing GFP-tagged α-tubulin6 (GFP–TUA6) (Ueda et al., 1999). Analysis of petal phenotype of the GFP-TUA6 line revealed no significant difference compared with the wild type, suggesting that ectopic expression of GFP–TUA6 had no effect on petal phenotype (see Supplementary Fig. S14). We next crossed the ipga1-1 mutant with the GFP-TUA6 control line to generate an ipga1-1 GFP-TUA6 homozygous line, and found that the ipga1-1 GFP-TUA6 line still had the same petal phenotype as the ipga1-1 mutant (Supplementary Fig. S14). We then analysed cortical microtubule arrangements in petal abaxial epidermal cells from various development stages. We quantified microtubule alignment using OrientationJ, an ImageJ plug-in, to calculate the directional coherency coefficient of the fibers (Fonck et al., 2009). A coherency coefficient close to 1 represents microtubules with a strongly coherent orientation. Cells in the GFP-TUA6 petals retained many randomly oriented microtubules and a few transverse microtubules throughout petal development stages 8–14 (Fig. 6A, B). By contrast, microtubules in ipga1-1 GFP-TUA6 mutant cells were disordered at stage 8, but became increasingly well-ordered throughout petal developmental stages 9–14 (Fig. 6A, B). Notably, stage 14 cells of ipga1-1 GFP-TUA6 had highly aligned microtubules with increased coherency compared with those of GFP-TUA6 (Fig. 6A, B). These results suggested that IPGA1 may play a negative role in regulating microtubule ordering and that the loss-of-function mutation in IPGA1 promotes a transition of microtubule reorientation from being random to transverse in the late stages of petal development.

Fig. 6.

IPGA1 affects microtubule organization and stability. (A) Analysis of microtubule organization at indicated petal developmental stages using the microtubule maker line GFP-TUA6. The ipga1-1 mutant displayed well-ordered transverse microtubule arrays in abaxial epidermal cells of the top part of petal blades at stage 10 and beyond. The red dots depict cell outlines. Scale bar: 5 µm. (B) Quantification of microtubule alignment. The microtubule alignment measurement was carried out with OrientationJ, an ImageJ plug-in, to calculate the directional coherency coefficient of the fibers (Fonck et al., 2009). A coherency coefficient close to 1 represents a strongly coherent orientation of the microtubules. Values are mean ±SD (n=70 cells from 15 petals). Asterisks indicate a significant difference (*P<0.05, **P<0.01, Student’s t-test). (C) Cortical microtubules were observed in epidermal cells of the basal region of GFP-TUA6 and ipga1-1 GFP-TUA6 etiolated hypocotyls after treatment with 20 μM oryzalin for 0, 2, 5, and 10 min. Oryzalin was then washed off and cortical microtubules were imaged after 2 h. Scale bar: 10 μm. (D) Quantification of number of microtubules in hypocotyl epidermal cells using ImageJ software. Values are mean ±SD (n>50 cells from each sample). Asterisks indicate a significant difference (*P<0.05, **P<0.01, Student’s t-test). (E) Cortical microtubules were observed in abaxial epidermal cells of the middle region of GFP-TUA6 and GFP-TUA6 ipga1-1 petals after treatment with water or 20 μM oryzalin for 10 min. Scale bar: 10 μm. (F) Quantification of the numbers of microtubules using ImageJ software. Values are mean ±SD (n>30 cells from each sample). Asterisks indicate a significant difference (**P<0.01, Student’s t-test).

Given that IPGA1 colocalizes with microtubules and alters cortical microtubule organization, we questioned whether IPGA1 could affect microtubule stability. We next compared the stability of the cortical microtubules in hypocotyl epidermal cells and petal abaxial epidermal cells from the GFP-TUA6 control line and the ipga1-1 mutant. In the first experiment, we treated dark-grown hypocotyls with the microtubule-disrupting drug oryzalin. Epidermal cells of the basal region were used to investigate the stability of cortical microtubules. We found that the density of cortical microtubules in the epidermal cells of the GFP-TUA6 control was similar to the ipga1-1 GFP-TUA6 line before treatment (Fig. 6C, D). Notably, the densities were significantly altered after the drug treatment. Cortical microtubules were disrupted in the GFP-TUA6 epidermal cells treated with 20 μM oryzalin for 2 min, while the microtubules in ipga1-1 GFP-TUA6 cells were largely unaffected (Fig. 6C, D). Increased oryzalin concentration and duration of treatment caused severe disruption of cortical microtubules in GFP-TUA6 cells but not in the ipga1-1 GFP-TUA6 cells (Fig. 6C, D; Supplementary Fig. S15). Upon washing off oryzalin after the treatment, a large number of cortical microtubule arrays were recovered in the epidermal cells of the ipga1-1 GFP-TUA6 cells, but not in the GFP-TUA6 cells (Fig. 6C, D). In the second experiment, we treated mature petals with 20 μM oryzalin. Similarly, we observed that microtubule arrays were more stable in the abaxial epidermal cells of ipga1-1 GFP-TUA6 petals compared with those of GFP-TUA6 petals after oryzalin treatment (Fig. 6E, F). Therefore, microtubules in the ipga1-1 cells were less sensitive to the oryzalin treatment. These results suggested that IPGA1 functions as a microtubule destabilizer.

Next, we investigated whether IPGA1 had effects on the dynamics of individual microtubules of petal abaxial epidermal cells. The parameters of microtubule dynamic instability including microtubule growth and shrinkage were examined in live cells located at the top part of petal blade abaxial epidermis from the GFP-TUA6 plants and the ipga1-1 GFP-TUA6 mutant plants. We selected individual microtubules with clearly visible leading ends for measurements (see Supplementary Fig. S16A). The results demonstrated that the average growth velocity in ipga1-1 GFP-TUA6 cells (5.7±0.12 μm min−1, n=40 microtubules from 15 cells of 10 plants) was significantly higher than that of the GFP-TUA6 cells (4.2±0.12 μm min−1, n=40 microtubules, P<0.01, Student’s t-test), and that the average shrinkage velocity in ipga1-1 GFP-TUA6 cells (8.88±2.58 μm min−1, n=40 microtubules from 15 cells of 10 plants) was significantly lower than that of the GFP-TUA6 cells (Supplementary Fig. S16B) (14.4±5.16 μm min−1, n=40 microtubules, P<0.01, Student’s t-test). In summary, these results suggest that IPGA1 participates in regulating the organization and dynamics of cortical microtubules in abaxial petal epidermal cells.

Discussion

Precise coordination of microtubule organization and dynamics plays critical roles in normal plant cell development, growth, and shape through orienting cellulose fibril arrays (Paredez et al., 2006; Lloyd and Chan, 2008; Crowell et al., 2009; Gutierrez et al., 2009; Lloyd, 2011; Lei et al., 2014). Growth anisotropy is widely found in diverse plant organs and is largely attributed to cell wall anisotropy that is generated by the orientation of the cellulose fibers (Baskin, 2005). The control of cell and organ shape in plants via regulated anisotropic growth is a key question in plant cell and developmental biology. Microtubules exhibit very specific arrangements during anisotropic growth and plant morphogenesis, but how this is regulated and how their alignment is coordinated is yet to be understood. In this study, through a genetic screen for Arabidopsis mutants with a phenotype of increased petal growth anisotropy, we identified IPGA1 as a new petal shape regulator (Fig. 1). Map-based cloning demonstrated that IPGA1 encodes a previously unknown protein associated with cortical microtubules and functions as a negative regulator of the anisotropic growth of petals (Figs 2, 3, 5). Analysis of the IPGA1 expression pattern demonstrated that IPGA1 is constitutively expressed in various organs/tissues, with its highest expression level in petals at late developmental stages (Fig. 4). Consistent with this, IPGA1 plays a role in regulating microtubule organization in petal abaxial epidermal cells (Fig. 6), thereby correlating with growth anisotropy in petals. Interestingly, BLAST analysis demonstrated that the IPGA1 gene is conserved in diverse plant species, including mosses, monocots, and dicots, but is not found in algae. Therefore, IPGA1 may play a crucial and fundamental role in cortical microtubule organization in land plants.

Our data suggested that IPGA1 is a microtubule-associated protein. Loss of IPGA1 function led to excess parallel cortical microtubules in petal abaxial epidermal cells. The patterns of microtubule organization, together with the abaxial petal epidermal cell phenotype observed in the ipga1-1 mutant, are in agreement with previous reports that well-ordered and transversal cortical microtubule arrays are associated with increased cell elongation with the suppression of radial cell expansion (Wasteneys and Galway, 2003; Smith and Oppenheimer, 2005). The quantification of microtubule alignments in petal abaxial epidermal cells demonstrated that a significant but only minor difference was present between the GFP-TUA6 control and the ipga1-1 GFP-TUA6 mutant line. One possible explanation for the relatively weak phenotype could be redundancy. Other potential homologs of IPGA1, including IPGAL1, IPGAL2, and in particular CHUP1, which could encode for an actin binding protein (Oikawa et al., 2003; Schmidt von Braun and Schleiff, 2008), might also participate the regulation of microtubule alignments. In addition, other genes such as SPIKE1, ROP GTPases, katanin, and the SPIRAL genes are also involved in microtubule alignment and cell expansion (Bichet et al., 2001; Qiu et al., 2002; Sedbrook et al., 2004; Ren et al., 2016; Feiguelman et al., 2018; Yanagisawa et al., 2018). Analysis of the genetic interactions between IPGA1 and these cell shape regulators needs to be investigated further.

The phytohormones auxin, gibberellins, and brassinosteroids function to promote cell expansion, whereas jasmonic acid and ethylene inhibit organ growth by negatively affecting cell expansion (Wolters and Jürgens, 2009; Chaiwanon et al., 2016). Notably, auxin, gibberellins, ethylene, and brassinosteroids have been shown to influence cortical microtubule organization through unclear molecular mechanisms in plant cells (Shibaoka, 1994; Le et al., 2005; Li et al., 2011; Polko et al., 2012; Wang et al., 2012; Vineyard et al., 2013). Furthermore, our data demonstrated that ipga1 mutant petals displayed increased growth anisotropy with the abaxial epidermal cells having fewer lobes. Interestingly, a recent study has shown that the shape of jigsaw-puzzle cells is an adaptation used by various plant organs and species to reduce the mechanical stress on their surface and that isotropic organ growth is correlated with the formation of puzzle-shaped cells (Sapala et al., 2018). At present, it is unclear what triggers the activation of IPGA1, making it an interesting possibility for IPGA1 to be involved in phytohormone- or mechanical force-mediated microtubule organization and control of organ growth. The detailed mechanisms by which IPGA1 regulate organ growth and shape need to be further investigated.

Supplementary data

Supplementary data are available at JXB online.

Fig. S1. Phenotypic analysis of F1 hybrid of ipga1 mutants.

Fig. S2. Complementation of the ipga1-1 mutant.

Fig. S3. Phenotypic analysis of ipga1 mutant petals.

Fig. S4. IPGA1 is not required for cell proliferation in petals.

Fig. S5. Phenotypic analysis of the petal abaxial epidermal cells in the ipga1-1 mutant.

Fig. S6. Alignment of the C-terminal region of IPGA1 with those of Arabidopsis AT3G25690 (CHUP1), AT1G07120, and AT1G48280 gene products.

Fig. S7. Conserved motifs of IPGA1 family members.

Fig. S8. Predicted coiled-coil domains of Arabidopsis CORD proteins.

Fig. S9. Phylogenetic tree of IPGA1 proteins.

Fig. S10. Complementation of the ipga1-1 mutant.

Fig. S11. GFP–IPGA1 is associated with cortical microtubules in the stable transgenic line.

Fig. S12. IPGA1 binds to microtubules in vitro.

Fig. S13. Subcellular localization of IPGA1L1–GFP and IPGA1L2–GFP.

Fig. S14. Phenotypic analysis of Col-0, GFP-TUA6, ipga1-1 GFP-TUA6, and ipga1-2 GFP-TUA6.

Fig. S15. IPGA1 affects microtubule stability.

Fig. S16. Comparison of microtubule growth and shrinkage in petal abaxial epidermal cells from GFP-TUA6 plants and the ipga1-1 GFP-TUA6 plants.

Table S1. Primers used in this study.

Video S1. Time-lapse observation of IPGA1-GFP driven by IPGA1 promoter in Arabidopsis cotyledon pavement cells expressing mCherry–TUA6.

Video S2. Time-lapse observation of GFP–IPGA1 signal recovery in a cotyledon pavement cell during a FRAP experiment.

Acknowledgements

We thank the ABRC Stock center for providing seeds of T-DNA insertion lines.

This work was supported by grants from the National Natural Science Foundation of China (Grants 31822003 and 31771344), and the Natural Science Foundation of Fujian Province (Grants 2016J06007 and 2018J01600).

References

- Ambrose JC, Shoji T, Kotzer AM, Pighin JA, Wasteneys GO. 2007. The Arabidopsis CLASP gene encodes a microtubule-associated protein involved in cell expansion and division. The Plant Cell 19, 2763–2775. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baskin TI. 2001. On the alignment of cellulose microfibrils by cortical microtubules: a review and a model. Protoplasma 215, 150–171. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baskin TI. 2005. Anisotropic expansion of the plant cell wall. Annual Review of Cell and Developmental Biology 21, 203–222. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baskin TI, Meekes HT, Liang BM, Sharp RE. 1999. Regulation of growth anisotropy in well-watered and water-stressed maize roots. II. Role of cortical microtubules and cellulose microfibrils. Plant Physiology 119, 681–692. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baskin TI, Wilson JE, Cork A, Williamson RE. 1994. Morphology and microtubule organization in Arabidopsis roots exposed to oryzalin or taxol. Plant & Cell Physiology 35, 935–942. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bhaskara GB, Wen TN, Nguyen TT, Verslues PE. 2017. Protein phosphatase 2Cs and microtubule-associated stress protein 1 control microtubule stability, plant growth, and drought response. The Plant Cell 29, 169–191. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bichet A, Desnos T, Turner S, Grandjean O, Höfte H. 2001. BOTERO1 is required for normal orientation of cortical microtubules and anisotropic cell expansion in Arabidopsis. The Plant Journal 25, 137–148. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Breuninger H, Lenhard M. 2010. Control of tissue and organ growth in plants. Current Topics in Developmental Biology 91, 185–220. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bulinski JC, Odde DJ, Howell BJ, Salmon TD, Waterman-Storer CM. 2001. Rapid dynamics of the microtubule binding of ensconsin in vivo. Journal of Cell Science 114, 3885–3897. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bürstenbinder K, Möller B, Plötner R, Stamm G, Hause G, Mitra D, Abel S. 2017. The IQD family of calmodulin-binding proteins links calcium signaling to microtubules, membrane subdomains, and the nucleus. Plant Physiology 173, 1692–1708. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Buschmann H, Hauptmann M, Niessing D, Lloyd CW, Schäffner AR. 2009. Helical growth of the Arabidopsis mutant tortifolia2 does not depend on cell division patterns but involves handed twisting of isolated cells. The Plant Cell 21, 2090–2106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Castoldi M, Popov AV. 2003. Purification of brain tubulin through two cycles of polymerization-depolymerization in a high-molarity buffer. Protein Expression and Purification 32, 83–88. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chaiwanon J, Wang W, Zhu JY, Oh E, Wang ZY. 2016. Information integration and communication in plant growth regulation. Cell 164, 1257–1268. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chang HY, Smertenko AP, Igarashi H, Dixon DP, Hussey PJ. 2005. Dynamic interaction of NtMAP65-1a with microtubules in vivo. Journal of Cell Science 118, 3195–3201. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen X, Wu S, Liu Z, Friml J. 2016. Environmental and endogenous control of cortical microtubule orientation. Trends in Cell Biology 26, 409–419. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Coen E, Rolland-Lagan AG, Matthews M, Bangham JA, Prusinkiewicz P. 2004. The genetics of geometry. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, USA 101, 4728–4735. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Crowell EF, Bischoff V, Desprez T, Rolland A, Stierhof YD, Schumacher K, Gonneau M, Höfte H, Vernhettes S. 2009. Pausing of Golgi bodies on microtubules regulates secretion of cellulose synthase complexes in Arabidopsis. The Plant Cell 21, 1141–1154. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Crowell EF, Gonneau M, Vernhettes S, Höfte H. 2010. Regulation of anisotropic cell expansion in higher plants. Comptes Rendus Biologies 333, 320–324. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Czesnick H, Lenhard M. 2015. Size control in plants—lessons from leaves and flowers. Cold Spring Harbor Perspectives in Biology 7, a019190. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dinneny JR, Yadegari R, Fischer RL, Yanofsky MF, Weigel D. 2004. The role of JAGGED in shaping lateral organs. Development 131, 1101–1110. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Drevensek S, Goussot M, Duroc Y, et al. 2012. The Arabidopsis TRM1-TON1 interaction reveals a recruitment network common to plant cortical microtubule arrays and eukaryotic centrosomes. The Plant Cell 24, 178–191. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Feiguelman G, Fu Y, Yalovsky S. 2018. ROP GTPases structure-function and signaling pathways. Plant Physiology 176, 57–79. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fishel EA, Dixit R. 2013. Role of nucleation in cortical microtubule array organization: variations on a theme. The Plant Journal 75, 270–277. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Folkers U, Kirik V, Schöbinger U, et al. 2002. The cell morphogenesis gene ANGUSTIFOLIA encodes a CtBP/BARS-like protein and is involved in the control of the microtubule cytoskeleton. The EMBO Journal 21, 1280–1288. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fonck E, Feigl GG, Fasel J, Sage D, Unser M, Rüfenacht DA, Stergiopulos N. 2009. Effect of aging on elastin functionality in human cerebral arteries. Stroke 40, 2552–2556. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fu Y, Xu T, Zhu L, Wen M, Yang Z. 2009. A ROP GTPase signaling pathway controls cortical microtubule ordering and cell expansion in Arabidopsis. Current Biology 19, 1827–1832. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fujikura U, Elsaesser L, Breuninger H, Sánchez-Rodríguez C, Ivakov A, Laux T, Findlay K, Persson S, Lenhard M. 2014. Atkinesin-13A modulates cell-wall synthesis and cell expansion in Arabidopsis thaliana via the THESEUS1 pathway. PLoS Genetics 10, e1004627. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- González N, Inzé D. 2015. Molecular systems governing leaf growth: from genes to networks. Journal of Experimental Botany 66, 1045–1054. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gonzalez N, Vanhaeren H, Inzé D. 2012. Leaf size control: complex coordination of cell division and expansion. Trends in Plant Science 17, 332–340. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Green PB. 1962. Mechanism for plant cellular morphogenesis. Science 138, 1404–1405. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gutierrez R, Lindeboom JJ, Paredez AR, Emons AM, Ehrhardt DW. 2009. Arabidopsis cortical microtubules position cellulose synthase delivery to the plasma membrane and interact with cellulose synthase trafficking compartments. Nature Cell Biology 11, 797–806. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hamada T. 2014. Microtubule organization and microtubule-associated proteins in plant cells. International Review of Cell and Molecular Biology 312, 1–52. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hamada T, Nagasaki-Takeuchi N, Kato T, Fujiwara M, Sonobe S, Fukao Y, Hashimoto T. 2013. Purification and characterization of novel microtubule-associated proteins from Arabidopsis cell suspension cultures. Plant Physiology 163, 1804–1816. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hill JP, Lord EM. 1989. Floral development in Arabidopsis thaliana: a comparison of the wild type and the homeotic pistillata mutant. Canadian Journal of Botany 67, 2922–2936. [Google Scholar]

- Huang T, Irish VF. 2015. Temporal control of plant organ growth by TCP transcription factors. Current Biology 25, 1765–1770. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huang T, Irish VF. 2016. Gene networks controlling petal organogenesis. Journal of Experimental Botany 67, 61–68. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim GT, Shoda K, Tsuge T, Cho KH, Uchimiya H, Yokoyama R, Nishitani K, Tsukaya H. 2002. The ANGUSTIFOLIA gene of Arabidopsis, a plant CtBP gene, regulates leaf-cell expansion, the arrangement of cortical microtubules in leaf cells and expression of a gene involved in cell-wall formation. The EMBO Journal 21, 1267–1279. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Klepikova AV, Kasianov AS, Gerasimov ES, Logacheva MD, Penin AA. 2016. A high resolution map of the Arabidopsis thaliana developmental transcriptome based on RNA-seq profiling. The Plant Journal 88, 1058–1070. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Korolev AV, Buschmann H, Doonan JH, Lloyd CW. 2007. AtMAP70-5, a divergent member of the MAP70 family of microtubule-associated proteins, is required for anisotropic cell growth in Arabidopsis. Journal of Cell Science 120, 2241–2247. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Landrein B, Hamant O. 2013. How mechanical stress controls microtubule behavior and morphogenesis in plants: history, experiments and revisited theories. The Plant Journal 75, 324–338. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Le J, Vandenbussche F, De Cnodder T, Van Der Straeten D, Verbelen JP. 2005. Cell elongation and microtubule behaviour in the Arabidopsis hypocotyl: responses to ethylene and auxin. Journal of Plant Growth Regulation 24, 166–178. [Google Scholar]

- Lee YK, Kim GT, Kim IJ, Park J, Kwak SS, Choi G, Chung WI. 2006. LONGIFOLIA1 and LONGIFOLIA2, two homologous genes, regulate longitudinal cell elongation in Arabidopsis. Development 133, 4305–4314. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lei L, Li S, Bashline L, Gu Y. 2014. Dissecting the molecular mechanism underlying the intimate relationship between cellulose microfibrils and cortical microtubules. Frontiers in Plant Science 5, 90. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li J, Jiang J, Qian Q, et al. 2011. Mutation of rice BC12/GDD1, which encodes a kinesin-like protein that binds to a GA biosynthesis gene promoter, leads to dwarfism with impaired cell elongation. The Plant Cell 23, 628–640. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li JF, Park E, von Arnim AG, Nebenführ A. 2009. The FAST technique: a simplified Agrobacterium-based transformation method for transient gene expression analysis in seedlings of Arabidopsis and other plant species. Plant Methods 5, 6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lian N, Liu X, Wang X, Zhou Y, Li H, Li J, Mao T. 2017. COP1 mediates dark-specific degradation of microtubule-associated protein WDL3 in regulating Arabidopsis hypocotyl elongation. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, USA 114, 12321–12326. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liang H, Zhang Y, Martinez P, Rasmussen CG, Xu T, Yang Z. 2018. The microtubule-associated protein IQ67 DOMAIN5 modulates microtubule dynamics and pavement cell shape. Plant Physiology 177, 1555–1568. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lindeboom JJ, Nakamura M, Hibbel A, Shundyak K, Gutierrez R, Ketelaar T, Emons AM, Mulder BM, Kirik V, Ehrhardt DW. 2013. A mechanism for reorientation of cortical microtubule arrays driven by microtubule severing. Science 342, 1245533. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lloyd C. 2011. Dynamic microtubules and the texture of plant cell walls. International Review of Cell and Molecular Biology 287, 287–329. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lloyd C, Chan J. 2008. The parallel lives of microtubules and cellulose microfibrils. Current Opinion in Plant Biology 11, 641–646. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lupas A, Van Dyke M, Stock J. 1991. Predicting coiled coils from protein sequences. Science 252, 1162–1164. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mao T, Jin L, Li H, Liu B, Yuan M. 2005. Two microtubule-associated proteins of the Arabidopsis MAP65 family function differently on microtubules. Plant Physiology 138, 654–662. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nag A, King S, Jack T. 2009. miR319a targeting of TCP4 is critical for petal growth and development in Arabidopsis. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, USA 106, 22534–22539. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nakamura M, Hashimoto T. 2009. A mutation in the Arabidopsis γ-tubulin-containing complex causes helical growth and abnormal microtubule branching. Journal of Cell Science 122, 2208–2217. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Oda Y, Fukuda H. 2012. Initiation of cell wall pattern by a Rho- and microtubule-driven symmetry breaking. Science 337, 1333–1336. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Oikawa K, Kasahara M, Kiyosue T, Kagawa T, Suetsugu N, Takahashi F, Kanegae T, Niwa Y, Kadota A, Wada M. 2003. CHLOROPLAST UNUSUAL POSITIONING1 is essential for proper chloroplast positioning. The Plant Cell 15, 2805–2815. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Paredez AR, Somerville CR, Ehrhardt DW. 2006. Visualization of cellulose synthase demonstrates functional association with microtubules. Science 312, 1491–1495. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Polko JK, van Zanten M, van Rooij JA, Marée AF, Voesenek LA, Peeters AJ, Pierik R. 2012. Ethylene-induced differential petiole growth in Arabidopsis thaliana involves local microtubule reorientation and cell expansion. New Phytologist 193, 339–348. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Powell AE, Lenhard M. 2012. Control of organ size in plants. Current Biology 22, R360–R367. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Qiu JL, Jilk R, Marks MD, Szymanski DB. 2002. The Arabidopsis SPIKE1 gene is required for normal cell shape control and tissue development. The Plant Cell 14, 101–118. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ren H, Dang X, Yang Y, Huang D, Liu M, Gao X, Lin D. 2016. SPIKE1 activates ROP GTPase to modulate petal growth and shape. Plant Physiology 172, 358–371. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Saffer AM, Carpita NC, Irish VF. 2017. Rhamnose-containing cell wall polymers suppress helical plant growth independently of microtubule orientation. Current Biology 27, 2248–2259.e4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sampathkumar A, Krupinski P, Wightman R, Milani P, Berquand A, Boudaoud A, Hamant O, Jönsson H, Meyerowitz EM. 2014. Subcellular and supracellular mechanical stress prescribes cytoskeleton behavior in Arabidopsis cotyledon pavement cells. eLife 3, e01967. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sapala A, Runions A, Routier-Kierzkowska AL, et al. 2018. Why plants make puzzle cells, and how their shape emerges. eLife 7, e32794. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sasaki T, Fukuda H, Oda Y. 2017. CORTICAL MICROTUBULE DISORDERING1 is required for secondary cell wall patterning in xylem vessels. The Plant Cell 29, 3123–3139. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sauret-Güeto S, Schiessl K, Bangham A, Sablowski R, Coen E. 2013. JAGGED controls Arabidopsis petal growth and shape by interacting with a divergent polarity field. PLoS Biology 11, e1001550. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schiessl K, Muiño JM, Sablowski R. 2014. Arabidopsis JAGGED links floral organ patterning to tissue growth by repressing Kip-related cell cycle inhibitors. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, USA 111, 2830–2835. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schmidt von Braun S, Schleiff E. 2008. The chloroplast outer membrane protein CHUP1 interacts with actin and profilin. Planta 227, 1151–1159. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sedbrook JC, Ehrhardt DW, Fisher SE, Scheible WR, Somerville CR. 2004. The Arabidopsis sku6/spiral1 gene encodes a plus end-localized microtubule-interacting protein involved in directional cell expansion. The Plant Cell 16, 1506–1520. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sedbrook JC, Kaloriti D. 2008. Microtubules, MAPs and plant directional cell expansion. Trends in Plant Science 13, 303–310. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shaw SL. 2013. Reorganization of the plant cortical microtubule array. Current Opinion in Plant Biology 16, 693–697. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shibaoka H. 1994. Plant hormone-induced changes in the orientation of cortical microtubules—Alterations in the cross-linking between microtubules and the plasma-membrane. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, USA 45, 527–544. [Google Scholar]

- Shoji T, Narita NN, Hayashi K, Hayashi K, Asada J, Hamada T, Sonobe S, Nakajima K, Hashimoto T. 2004. Plant-specific microtubule-associated protein SPIRAL2 is required for anisotropic growth in Arabidopsis. Plant Physiology 136, 3933–3944. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smith LG, Oppenheimer DG. 2005. Spatial control of cell expansion by the plant cytoskeleton. Annual Review of Cell and Developmental Biology 21, 271–295. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smyth DR, Bowman JL, Meyerowitz EM. 1990. Early flower development in Arabidopsis. The Plant Cell 2, 755–767. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sugimoto K, Himmelspach R, Williamson RE, Wasteneys GO. 2003. Mutation or drug-dependent microtubule disruption causes radial swelling without altering parallel cellulose microfibril deposition in Arabidopsis root cells. The Plant Cell 15, 1414–1429. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Szécsi J, Joly C, Bordji K, Varaud E, Cock JM, Dumas C, Bendahmane M. 2006. BIGPETALp, a bHLH transcription factor is involved in the control of Arabidopsis petal size. The EMBO Journal 25, 3912–3920. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Takeda S, Matsumoto N, Okada K. 2004. RABBIT EARS, encoding a SUPERMAN-like zinc finger protein, regulates petal development in Arabidopsis thaliana. Development 131, 425–434. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thitamadee S, Tuchihara K, Hashimoto T. 2002. Microtubule basis for left-handed helical growth in Arabidopsis. Nature 417, 193–196. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tian J, Han L, Feng Z, Wang G, Liu W, Ma Y, Yu Y, Kong Z. 2015. Orchestration of microtubules and the actin cytoskeleton in trichome cell shape determination by a plant-unique kinesin. eLife 4, e09351. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tsuge T, Tsukaya H, Uchimiya H. 1996. Two independent and polarized processes of cell elongation regulate leaf blade expansion in Arabidopsis thaliana (L.) Heynh. Development 122, 1589–1600. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ueda K, Matsuyama T, Hashimoto T. 1999. Visualization of microtubules in living cells of transgenic Arabidopsis thaliana. Protoplasma 206, 201–206. [Google Scholar]

- Uyttewaal M, Traas J, Hamant O. 2010. Integrating physical stress, growth, and development. Current Opinion in Plant Biology 13, 46–52. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- van Es SW, Silveira SR, Rocha DI, Bimbo A, Martinelli AP, Dornelas MC, Angenent GC, Immink RGH. 2018. Novel functions of the Arabidopsis transcription factor TCP5 in petal development and ethylene biosynthesis. The Plant Journal 94, 867–879. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vanstraelen M, Baloban M, DaInes O, Cultrone A, Lammens T, Boudolf V, Brown SC, De Veylder L, Mergaert P, Kondorosi E. 2009. APC/C-CCS52A complexes control meristem maintenance in the Arabidopsis root. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, USA 106, 11806–11811. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Varaud E, Brioudes F, Szécsi J, Leroux J, Brown S, Perrot-Rechenmann C, Bendahmane M. 2011. AUXIN RESPONSE FACTOR8 regulates Arabidopsis petal growth by interacting with the bHLH transcription factor BIGPETALp. The Plant Cell 23, 973–983. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vineyard L, Elliott A, Dhingra S, Lucas JR, Shaw SL. 2013. Progressive transverse microtubule array organization in hormone-induced Arabidopsis hypocotyl cells. The Plant Cell 25, 662–676. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Walia A, Nakamura M, Moss D, Kirik V, Hashimoto T, Ehrhardt DW. 2014. GCP-WD mediates γ-TuRC recruitment and the geometry of microtubule nucleation in interphase arrays of Arabidopsis. Current Biology 24, 2548–2555. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang X, Zhang J, Yuan M, Ehrhardt DW, Wang ZY, Mao T. 2012. Arabidopsis microtubule destabilizing protein40 is involved in brassinosteroid regulation of hypocotyl elongation. The Plant Cell 24, 4012–4025. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang X, Zhu L, Liu B, Wang C, Jin L, Zhao Q, Yuan M. 2007. Arabidopsis MICROTUBULE-ASSOCIATED PROTEIN18 functions in directional cell growth by destabilizing cortical microtubules. The Plant Cell 19, 877–889. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wasteneys GO. 2004. Progress in understanding the role of microtubules in plant cells. Current Opinion in Plant Biology 7, 651–660. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wasteneys GO, Ambrose JC. 2009. Spatial organization of plant cortical microtubules: close encounters of the 2D kind. Trends in Cell Biology 19, 62–71. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wasteneys GO, Galway ME. 2003. Remodeling the cytoskeleton for growth and form: an overview with some new views. Annual Review of Plant Biology 54, 691–722. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Winter D, Vinegar B, Nahal H, Ammar R, Wilson GV, Provart NJ. 2007. An “electronic fluorescent pictograph” browser for exploring and analyzing large-scale biological data sets. PLoS One 2, e718. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wolters H, Jürgens G. 2009. Survival of the flexible: hormonal growth control and adaptation in plant development. Nature Reviews. Genetics 10, 305–317. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yanagisawa M, Alonso JM, Szymanski DB. 2018. Microtubule-dependent confinement of a cell signaling and actin polymerization control module regulates polarized cell growth. Current Biology 28, 2459–2466.e4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.