Several reliable QTLs for leaf photosynthesis were detected using reciprocal mapping populations derived from japonica and indica rice varieties with different photosynthetic capacities.

Keywords: Backcross inbred line, chromosome segment substitution line, nitrogen content, phenology, photosynthesis, quantitative trait locus, reciprocal mapping population, rice, stomatal conductance, yield

Abstract

The improvement of leaf net photosynthetic rate (An) is a major challenge in enhancing crop productivity. However, the genetic control of An among natural genetic accessions is still poorly understood. The high-yielding indica cultivar Takanari has the highest An of all rice cultivars, 20–30% higher than that of the high-quality japonica cultivar Koshihikari. By using reciprocal backcross inbred lines and chromosome segment substitution lines derived from a cross between Takanari and Koshihikari, we identified three quantitative trait loci (QTLs) where the Takanari alleles enhanced An in plants with a Koshihikari genetic background and five QTLs where the Koshihikari alleles enhanced An in plants with a Takanari genetic background. Two QTLs were expressed in plants with both backgrounds (type I QTL). The expression of other QTLs depended strongly on genetic background (type II QTL). These beneficial alleles increased stomatal conductance, the initial slope of An versus intercellular CO2 concentration, or An at CO2 saturation. Pyramiding of these alleles consistently increased An. Some alleles positively affected biomass production and grain yield. These alleles associated with photosynthesis and yield can be a valuable tool in rice breeding programs via DNA marker-assisted selection.

Introduction

To meet the growing demand for rice (Oryza sativa L.) from the rapidly expanding world population, the world will need 85% more rice production by 2050 relative to 2013 (Ray et al., 2013; Long et al., 2015). Rice yield has increased remarkably since the release of modern semi-dwarf cultivars with high harvest indices in the mid-1960s (Khush, 1999). However, as harvest indices are now close to the theoretical maximum, increases in total biomass production are key to further increasing yields (Mann, 1999; Zhu et al., 2010; van Bezouw et al., 2019). Many genes relating to sink size have been identified through genetic studies (Ashikari et al., 2005; Huang et al., 2009; Ikeda-Kawakatsu et al., 2009; Miura et al., 2010; Yoshida et al., 2013). However, little yield enhancement with these genetic factors is found, indicating that enhanced source capacity is required (Ohsumi et al., 2011; Fukushima et al., 2017).

Dry matter production is determined by radiation use efficiency (RUE) that is affected by canopy architecture, individual leaf photosynthesis, and leaf area. Leaf area affects dry matter production through light interception at the early and late growth stages, when leaf area index (LAI) is less than the critical value (Gardner et al., 1985; Hay and Porter, 2006; Hirasawa, 2014). Canopy architecture affects dry matter production in the middle growth stages, when LAI is greater than the critical value (Hay and Porter, 2006; Hirasawa, 2014), whereas individual leaf photosynthesis affects dry matter production over the entire growing season (Hay and Porter, 2006; Hirasawa, 2014). Improving canopy architecture with short plant height and erect leaves contributed greatly to the yield increase in the last century (Kumura, 1995; Khush, 1999; Hay and Porter, 2006; Taylaran et al., 2009); however, it is unlikely to contribute to further large increases because it has already been subjected to a long breeding history (Kumura, 1995; Horton, 2000; Reynolds et al., 2011; Gu et al., 2014). Thus, improvements in the photosynthetic rates of individual leaves within the canopy have become the focus for increased rice grain production (Horton, 2000; Hubbart et al., 2007; Parry et al., 2011).

Increasing the rate of photosynthesis has been attempted by molecular engineering approaches such as modification of the kinetic properties and production of photosynthetic enzymes (Kebeish et al., 2007; Zhu et al., 2008; Raines, 2011; Sage and Zhu, 2011; Long et al., 2015; Ort et al., 2015; Simkin et al., 2015), and the introduction of the C4 photosynthetic pathway into rice, a C3 plant, to avoid wasteful photorespiration (Sage et al., 2017). Some trials have succeeded; for example, Kromdijk et al. (2016) optimized photoprotection recovery in tobacco leaves and increased dry matter production by 15%. However, these attempts still face challenges for production in terms of adaptation, ecological risks, and public perceptions of genetically modified crops. Another way to enhance photosynthesis is to exploit the natural variation among genetic resources through cross-breeding (Raines, 2011; Flood et al., 2011; Gu et al., 2014). This approach is expected to discover unknown regulatory and developmental genes that may not be identifiable by mutant screening (Sage et al., 2017). Mining existing genetic variation could be the most efficient method for short-term improvements (Parry et al., 2011). A wide range of varietal differences in net photosynthetic rate (An) among rice cultivars have been examined for the past half century (Murata, 1961; Cook and Evans, 1983; Sasaki and Ishii, 1992; Kanemura et al., 2007; Jahn et al., 2011). Several loci that enhance leaf photosynthesis have been detected on chromosomes 3, 4, 5, 6, 8, 9, and 11 (Teng et al., 2004; Adachi et al., 2011a; Gu et al., 2012); however, a very limited number of genes (GREEN FOR PHOTOSYNTHESIS and Carbon assimilation rate 8) responsible for photosynthesis have been identified (Takai et al., 2013; Adachi et al., 2017). More effort is needed to understand the genetic basis of leaf photosynthesis for developing breeding strategies.

Photosynthetic rate in C3 species is limited by biochemical and diffusion capacities. Biochemical limitations can be subdivided into the capacity of Rubisco to consume ribulose-1,5-bisphosphate (RuBP) and the capacity for RuBP to regenerate (Farquhar et al., 1980). Diffusion limitations can be subdivided into stomatal and mesophyll limitations, termed stomatal conductance (gs) and mesophyll conductance (gm), respectively (Makino, 2011): gs controls CO2 flux into the intercellular spaces from the atmosphere, and gm controls it from the intercellular spaces to the site of carboxylation in the chloroplast stroma (Sage et al., 2017). In rice, An is closely related to leaf nitrogen content (LNC), which affects the Rubisco content and electron transport supporting RuBP regeneration as well as gs and gm (Makino et al., 1994; Yamori et al., 2011). It is known that gs is larger in cultivars with higher hydraulic conductance than in those with lower hydraulic conductance even at the same LNC (Adachi et al., 2011a; Taylaran et al., 2011). These differences underlie varietal differences in An (Kuroda and Kumura, 1990; Sasaki et al., 1996; Kanemura et al., 2007; Ohsumi et al., 2007; Adachi et al., 2011b; Taylaran et al., 2011). Therefore, these physiological factors should be examined along with An for a comprehensive understanding of the genetic control of leaf photosynthesis.

The high-yielding indica cultivar Takanari has the highest An among rice cultivars, at 30–33 μmol m−2 s−1 (Kanemura et al., 2007; Hirasawa et al., 2010; Taylaran et al., 2011) during panicle formation to ripening. Its higher An is supported by higher Rubisco content due to greater LNC and by higher gs due to larger hydraulic conductance (Hirasawa et al., 2010; Taylaran et al., 2009, 2011). Thus, Takanari seems to have favorable alleles that contribute to higher An. The high-quality japonica cultivar Koshihikari has a low An of 25–28 μmol m−2 s−1. Some backcross inbred lines (BILs) derived from a cross between Takanari and Koshihikari (Koshihikari/Takanari//Takanari) have 20–30% higher values of An than Takanari (Adachi et al., 2013). This indicates that Koshihikari might have some alleles that further increase An of indica cultivars.

In this study, we examined quantitative trait loci (QTLs) for An, using reciprocal backcross inbred lines (BILs) and chromosome segment substitution lines (CSSLs) derived from a cross between Takanari and Koshihikari in the field for 4 years (2 years for BILs and 2 years for CSSLs). Then we investigated the physiological properties of identified QTLs by using CSSLs grown in pots for 4 years (2 years for plants in Takanari genetic background and 2 years in Koshihikari genetic background). These investigations helped in understanding the genetic architecture of leaf photosynthesis controlled by genetic variation in the rice.

Materials and methods

Plant materials

We used BILs developed by Fukuda et al. (2018). F1 plants from a cross between Koshihikari and Takanari were backcrossed to Koshihikari (for Koshihikari/Takanari//Koshihikari, BKT) or to Takanari (for Koshihikari/Takanari//Takanari, BTK) to produce BC1F1. Then BC1F6 (for the measurements in 2009) and BC1F7 (for the measurements in 2010) lines were generated from a single BC1F1 individual using 140 SSR markers distributed over the genomes of the BILs in Koshihikari background (BKTs) and BILs in Takanari background (BTKs). Eighty-two and 87 lines were used for measurements of BKTs and BTKs, respectively, in 2009, and 87 lines, for BKTs and BTKs in 2010 (Supplementary Table S1 at JXB online). Their genotypes are shown in Supplementary Table S1.

We also used 41 CSSLs covering most of the Takanari genome in the Koshihikari background (T-CSSLs, SL1201–1241) and 39 CSSLs covering the Koshihikari genome in the Takanari background (K-CSSLs, SL1301–1339) developed by Takai et al. (2014) as reciprocal CSSLs.

To detect the precise position of QTL regions, one T-CSSL (or K-CSSL) carrying a single QTL was crossed with Koshihikari (or Takanari), and the self-pollinated seeds were obtained. The progeny lines were selected based on their genotypes analysed with SSR markers. To develop QTL pyramiding lines, two T-CSSLs (or K-CSSLs) carrying a single QTL were crossed and a homozygous plant was selected from F2 individuals with SSR markers.

Cultivation

Koshihikari, Takanari, BKTs and BTKs (in 2009 and 2010), and T-CSSLs and K-CSSLs (in 2011 and 2012) were grown in the paddy field of the University Farm located at Fuchu, Tokyo, Japan (35°41′N, 139°29′E). For comparisons of dry matter and grain production, plants were also grown in the paddy field in 2013 to 2016. Seedlings at the fourth-leaf stage were transplanted at 22.2 hills m−2 (row width, 30 cm), with one plant per hill, and grown under submerged conditions. As a basal dressing, manure was applied at ~15 t ha−1, and chemical fertilizer was applied at 30 kg N, 26 kg P, and 50 kg K ha−1. One-third of the total N was applied as nitrogen sulfate, one-third as slow-release urea (LP-50), and one-third as very-slow-release urea (LPS-100; Chisso Asahi Fertilizer, Tokyo, Japan). No topdressing was applied. The experiments were arranged by randomized block design with two (for BILs) or three (for CSSLs) replicates and three or four replicates for biomass and yield determination. For BILs, one replication block consisted of one series of the lines and one row with eight hills for each line. For CSSLs, one replication block consisted of one series of the lines and four rows with nine hills per row for each line. For the determination of biomass and grain production, one replication block consisted of a set of comparable lines in an area of 10 m2 or 4 m2 per line for plants in the Koshihikari or Takanari genetic background, respectively.

CSSLs were also grown in pots with 12 liters of soil per pot. Seedlings at the fourth-leaf stage were transplanted into pots filled with a 1:1 (v/v) mixture of alluvial soil from the Tama River and Kanto diluvial soil at a density of three plants per hill, with three hills per pot, and grown under submerged conditions. Fertilizer was applied at 1.0 g N, 0.44 g P, and 0.83 g K per pot as a basal dressing, and 1.0 g N per pot as a topdressing a week before heading. The plants were grown outdoors with four to six replications arranged by randomized block design. One replication block consisted of a set of comparable lines with five pots per line.

Measurements of leaf photosynthesis rate and stomatal conductance

In the field in 2009–2012, we measured An and gs with a portable photosynthesis system (LI-6400; LI-COR Inc., Lincoln, NE, USA) and a LED light source (LI-6400-02B; LI-COR Inc.) at the full heading stage in flag leaves attached to the main stem. We measured leaf color (SPAD value) of five or six leaves per replicate with a chlorophyll meter (SPAD-502; Konica Minolta, Osaka, Japan), and An and gs of two or three leaves with average SPAD values.

The air temperature in the leaf chamber was controlled at 30 °C, and the photosynthetically active radiation at the leaf surface was controlled at 2000 μmol photon m−2 s−1. The ambient CO2 concentration in the assimilation chamber (Ca) was adjusted to 370±1 μmol mol−1 by controlling the CO2 concentration of the air entering the chamber, and the leaf-to-air vapor pressure difference (VPD) was adjusted to 1.2–1.5 kPa by controlling the flow rate of air through the desiccant. Measurements were taken in sunlight between 08.30 and 11.30 h on clear days or at >400 μmol photon m−2 s−1 until 14.00 h on cloudy days. The leaf gas exchange rate (indicated by An and gs) reached a steady state within a few minutes after the leaf was installed in the chamber. At least two measurements were taken on the same leaf on different days and averaged.

For An measurements in the pots in 2013–2016, Ca and leaf temperature were controlled at 400 μmol mol−1 and 30 °C. The photosynthetically active radiation was 2000 μmol photon m−2 s−1. The VPD was adjusted to 1.2–1.5 kPa. The An–Ci curve was obtained at 13 values in the order of 330, 400, 500, 600, 800, 1000, 1500, 300, 230, 160, 120, 80, and 40 μmol mol−1 of the intercellular CO2 concentration (Ci) by changing Ca, and the initial slope of the curve and photosynthetic rate at CO2 saturation (Asat) were estimated. An was measured at 400 μmol CO2 mol−1 between 08.30 and 11.30 h on clear days and 14.00 h on cloudy days, and An–Ci curves were drawn. SPAD values of five to six leaves per replicate were measured, and one or two leaves with average SPAD values were selected for measurements of An and gs.

Quantification of leaf nitrogen

LNC of leaves in which photosynthesis was measured was quantified with a CN analyser (MT700 Mark II; Yanako, Tokyo, Japan).

Measurements of dry weight, yield, and yield components

Before sampling for dry weight measurements, we counted panicle numbers in 25 successive hills per replicate. Then we harvested 7–10 hills with an average number of panicles from each replicate and removed roots after washing stem and roots with tap water. The plants were then dried in a ventilated oven at 80 °C for >4 d to a constant dry weight. Plants in an area of 1–2 m2 in each replicate were harvested to determine grain yield per unit area. We determined spikelet number per panicle, ripening percentage, and 1000-grain weight in three or four hills with an average number of panicles in each replicate. Panicle number per m2 was determined as the average of 25 hills per replicate. Grains thicker than 1.8 mm were selected by sieving as fully ripened.

QTL analyses

Data for each parameter were averaged for each replication and used in QTL analyses using genetic linkage maps of the BKT and BTK populations. QTL analyses were performed by composite interval mapping using the Zmapqtl program (model 6) in QTL Cartographer v. 2.5 software (Wang et al., 2005). Genome-wide threshold values (α=0.05) were used to detect putative QTLs based on the results of 1000 permutations.

We conducted analysis of variance (ANOVA) to examine the effects of CSSL on An and traits relevant to An. Significant CSSL effects were explored with Dunnett’s test, using Koshihikari as the control for the Koshihikari background and Takanari as the control for the Takanari background in JMP v. 13 software (SAS Institute, Cary, NC, USA). To delineate candidate QTL regions, we conducted substitution mapping by comparing overlapping segments among the CSSLs according to Takai et al. (2014).

Statistical analysis

Differences and interactions between rice lines and year effects on variance were tested by two-way ANOVA. Differences were also tested by the Tukey–Kramer test. Pearson’s correlation coefficient was calculated to test the significance of the relationships between An, LNC, and gs and between days to heading from sowing (DTH) and An. All statistics were analysed in JMP v. 13 software.

Results

Detection of QTLs

The heading time was 7–9 d earlier in Koshihikari than in Takanari (Supplementary Table S2). Takanari consistently had 20–30% higher An than Koshihikari (Figs 1–3). An of BKTs and BTKs showed a continuous distribution; the means in BKTs and BTKs were close to those of Koshihikari and Takanari, respectively (Fig. 1).

Fig. 1.

Frequency distributions of photosynthetic rate (An) of BILs with Koshihikari background (A, C) and Takanari background (B, D) grown in the paddy field. Arrowheads indicate average values: black (K), Koshihikari; white (T), Takanari; gray, inbred lines.

Fig. 3.

Photosynthetic rates (An) of flag leaves at full heading stage of K-CSSLs (Takanari background) grown in the paddy field. Error bars represent SD (n=3). Asterisks indicate significant differences from Takanari at the *5%, **1%, and ***0.1% α level (Dunnett’s test). NA, not available. (This figure is available in color at JXB online.)

The phenotype data are shown in Supplementary Table S1. QTL analysis for An using the reciprocal BILs was conducted separately for populations and years. The analysis of BKTs estimated two QTLs with significant logarithm of odds (LOD) values on chromosomes (Chrs) 3 and 4 in both 2009 and 2010 (Table 1). The Koshihikari allele on Chr. 3 and the Takanari allele on Chr. 4 increased An. The analysis of BTKs estimated six QTLs on Chrs 1, 2, 3, 4, 5, and 7 (Table 1). Only one QTL, at RM3534 on Chr. 4, was detected in both years. Koshihikari alleles on Chrs 1, 2, and 7 and Takanari alleles on Chrs 3, 4, and 5 increased An. The QTL on Chr. 4 was detected in both populations across the years.

Table 1.

QTLs for enhancing flag leaf photosynthesis estimated by using BILs

| Line | Year | Chr | Nearest marker or interval | LOD | Confidence interval (Mb) | PVE (%)a | Additive effectb | QTL |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| BKT | 2009 | 3 | RM1371 | 4.02 | 6.8 | 13.4 | 1.42 | qHP3a |

| 4 | RM3534 | 3.59 | 4.7 | 12.1 | −1.71 | qHP4 | ||

| 2010 | 3 | RM1371 | 3.85 | 6.8 | 11.7 | 1.25 | qHP3a | |

| 4 | RM3534 | 5.56 | 4.7 | 17.8 | −2.08 | qHP4 | ||

| BTK | 2009 | 1 | RM7594 | 4.03 | 7.8 | 13.5 | 1.69 | qHP1b |

| 3 | RM3204 | 3.84 | 5.1 | 16.9 | −3.03 | qHP3b | ||

| 4 | RM3534 | 3.97 | 4.7 | 13.9 | -1.7 | qHP4 | ||

| 5 | RM3838–RM1386 | 3.54 | 5.8 | 13.6 | −1.46 | qHP5 | ||

| 2010 | 2 | RM5521 | 3.54 | 11.7 | 10.4 | 0.98 | — | |

| 4 | RM3534 | 5.28 | 4.7 | 16.3 | −1.45 | qHP4 | ||

| 7 | RM6420 | 2.61 | 10.6 | 8.3 | 0.98 | qHP7b |

a Phenotypic variance explained.

b Koshihikari allele increases.

In the analysis of T-CSSLs (Koshihikari genetic background), lines SL1208, SL1217, and SL1235 had significantly higher An than Koshihikari in 2011 and 2012 (Fig. 2A, B). Additionally, SL1222 and SL1224 had significantly higher An than Koshihikari in 2011, while SL1227 had significantly lower An (Fig. 2A). In the analysis of K-CSSLs (Takanari genetic background), SL1301, SL1311, SL1324, and SL1325 had consistently and significantly higher An than Takanari in both years (Fig. 3A, B). Additionally, SL1303 had significantly higher An than Takanari in 2011, and some lines (SL1315, SL1335, and SL1336) had significantly lower An than Takanari (Fig. 3A); SL1336 had significantly lower An than Takanari in both years. We also found SL1324 and SL1325 carried different sets of QTLs for An from the fine mapping experiment of SL1324 (see Supplementary Fig. S1; Supplementary Table S3) although they have an overlapping segment of Koshihikari. Confidence intervals of QTLs for An estimated by using CSSLs and by narrowing down are shown in Supplementary Table S3.

Fig. 2.

Photosynthetic rates (An) of flag leaves at full heading stage of T-CSSLs (Koshihikari background) grown in the paddy field. Error bars represent SD (n=3). Symbols indicate significant differences from Koshihikari at the †10%, *5%, **1%, and ***0.1% α level (Dunnett’s test). (This figure is available in color at JXB online.)

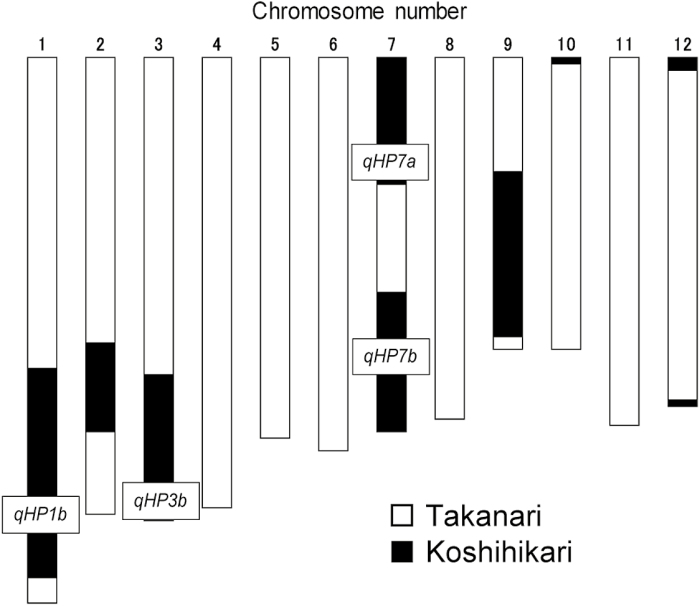

All QTLs for An detected in BILs and CSSLs were mapped on the rice genome and visualized by graphical genotyping (Fig. 4A, B). Most were detected more than twice among the years; we named them ‘qHP’ (high photosynthesis) and focused on them for further analysis. Four QTLs where Takanari alleles enhanced An were identified in two or more years in CSSLs or BILs on Chrs 2, 4, 5, and 10. Among them, only qHP4 was detected in both backgrounds. qHP5 was detected in BTKs and K-CSSL populations (Takanari background), even though the Takanari allele increased An. Six QTLs where Koshihikari alleles enhanced An were identified in two or more years in CSSLs or BILs on Chrs 1, 3, and 7. Most were identified in the populations of the Takanari background, and only qHP3a was detected in the BKTs and T-CSSL populations (Koshihikari background).

Fig. 4.

Summary of identified QTLs. (A) Graphical genotypes of mapping populations. Orange, homozygous for Koshihikari; blue, homozygous for Takanari. BILs (BKTs and BTKs) were used in 2009 and 2010, and CSSLs (T-CSSLs and K-CSSLs) were used in 2011 and 2012. (B) Locations of QTLs for photosynthetic rate (An). (C) Locations of QTLs for stomatal conductance (gs). (D) Locations of QTLs for leaf nitrogen content (LNC). Circles represent the locations of QTLs for An that were repeatedly identified in different years.

In the field in 2009, Takanari had 91% higher gs and 22% higher LNC than Koshihikari, and the mean LNCs in BKTs and BTKs were close to those of Koshihikari and Takanari, respectively (see Supplementary Fig. S2). These trends were the same in 2010 (data not shown). There were close correlations between gs and An and between LNC and An in BKTs and BTKs (Supplementary Fig. S3) and in CSSLs, although those between LNC and An were lower in K-CSSLs than in T-CSSLs (Supplementary Fig. S4).

We mapped the QTLs associated with increased gs and increased LNC as we did for An from the results of the BILs (see Supplementary Tables S4, S5) and CSSLs (Supplementary Figs S5–S8). Four QTLs where Takanari alleles enhanced gs were identified in two or more years in CSSLs or BILs on Chrs 3, 4, 10, and 11, and two of them overlapped with qHP4 and qHP10 (Fig. 4C). No QTL where the Koshihikari allele enhanced gs was identified in any year in CSSLs or BILs. Four QTLs where Takanari alleles increased LNC were identified in two or more years in CSSLs or BILs on Chrs 1, 2, 4, and 9, and two of them overlapped with qHP2 and qHP4 (Fig. 4D). One QTL where Koshihikari alleles increased LNC was identified in two or more years in CSSLs or BILs on Chr. 7, and overlapped with qHP7b (Fig. 4D). We also identified several loci for gs and LNC without any association with the QTLs for An. These results indicate that QTLs for increased gs or LNC don’t always correspond with enhanced An.

Validation of QTLs using pot-grown rice

We grew the parental lines and CSSLs that carry QTLs for An in the background of either Koshihikari or Takanari in pots and examined the cause of the higher An. Takanari had a significantly larger An and gs than Koshihikari, reflecting its larger Ci/Ca (Fig. 5A, B, E). LNC was significantly higher in Takanari than in Koshihikari (Fig. 5F), reflecting the significantly larger initial slope of the An–Ci curve (Fig. 5C), but there was no significant difference in Asat between cultivars (Fig. 5D). All CSSLs had significantly higher An than the respective parental cultivars across the years: SL1217 and NIL10 (developed from SL1235 and carrying a Takanari chromosome segment from RM6128 to RM25840) had significantly higher An than Koshihikari, and SL1301, SL1303, SL1311, SL1324, and SL1325 had significantly higher An than Takanari (Table 2). These results clearly indicate that the QTLs identified in the field also had positive effects on An even in pots. We did not use SL1208 for measurements because the plant size was very small (Takai et al., 2014).

Fig. 5.

Comparisons of photosynthetic rate (An) (A), stomatal conductance (gs) (B), initial slope of the An–Ci curve (C), An at CO2 saturation (Asat) (D), ratio of intercellular CO2 concentration (Ci) to ambient CO2 concentration (Ca) (Ci/Ca) (E), and leaf nitrogen content (LNC) (F) between Koshihikari and Takanari grown in pots. Error bars represent SD (n=6). Asterisks indicate significant differences between Koshihikari and Takanari at the *5% and **1% α level (Student’s t-test). ns, not significant.

Table 2.

Comparisons of photosynthetic rate (An), stomatal conductance (gs), initial slope of the An–Ci curve, photosynthetic rate at CO2 saturation (Asat), and leaf nitrogen content (LNC) of Koshihikari, Takanari, and CSSLs carrying QTLs for enhancing An; all plants were grown in pots

| Group | Year | Cultivar, line | QTL | A n (μmol m−2 s−1) | g s (mol m−2 s−1) | Initial slope (mol m−2 s−1) | A sat (μmol m−2 s−1) | LNC (g m−2) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| A | 2015 | Koshihikari | 25.9±1.7 | 0.54±0.06 | 0.128±0.011 | 41.4±4.8 | 1.98±0.03 | |

| SL1217 | qHP4 | 32.2±2.5** | 0.69±0.05** | 0.144±0.020 | 49.6±1.5** | 2.27±0.19** | ||

| NIL10 | qHP10 | 29.0±1.9* | 0.72±0.11** | 0.134±0.006 | 44.4±4.9 | 2.04±0.09 | ||

| 2016 | Koshihikari | 24.1±0.6 | 0.47±0.02 | 0.108±0.005 | 36.0±3.1 | 1.60±0.18 | ||

| SL1217 | qHP4 | 26.9±1.7** | 0.48±0.06 | 0.127±0.005** | 40.7±2.6** | 1.82±0.06* | ||

| NIL10 | qHP10 | 26.1±1.1* | 0.52±0.03* | 0.116±0.005* | 38.9±1.1 | 1.59±0.19 | ||

| ANOVA | Line | <0.001 | <0.001 | <0.001 | <0.001 | <0.001 | ||

| Year | <0.001 | <0.001 | <0.001 | <0.001 | <0.001 | |||

| Line×Year | <0.05 | <0.05 | ns | ns | ns | |||

| B | 2013 | Takanari | 31.2±0.4 | 1.16±0.15 | 0.132±0.007 | 42.0±4.4 | 1.54±0.04 | |

| SL1301 | qHP1a | 33.8±1.6** | 1.31±0.11 | 0.150±0.006 | 44.2±1.6 | 1.59±0.09 | ||

| SL1303 | qHP1b | — | — | — | — | — | ||

| SL1311 | qHP3b | 35.0±1.0** | 1.27±0.12 | 0.161±0.011** | 51.0±0.3** | 1.72±0.10* | ||

| SL1324 | qHP7a | 33.0±0.5* | 1.37±0.29 | 0.151±0.006 | 44.2±1.9 | 1.58±0.08 | ||

| SL1325 | qHP7b | 33.7±0.9** | 1.20±0.35 | 0.152±0.010* | 49.1±3.7** | 1.72±0.08** | ||

| 2014 | Takanari | 29.6±1.6 | 0.85±0.11 | 0.141±0.008 | 38.8±3.4 | 1.82±0.19 | ||

| SL1301 | qHP1a | 34.8±1.1** | 1.25±0.17** | 0.154±0.006** | 44.3±2.3** | 1.92±0.05 | ||

| SL1303 | qHP1b | 34.1±0.6** | 0.87±0.05 | 0.154±0.004* | 44.1±3.2* | 2.16±0.07* | ||

| SL1311 | qHP3b | 32.2±0.7** | 0.90±0.11 | 0.144±0.006 | 42.0±2.5 | 2.06±0.05 | ||

| SL1324 | qHP7a | 33.5±1.4** | 1.00±0.09 | 0.149±0.005 | 44.8±1.5** | 1.92±0.27 | ||

| SL1325 | qHP7b | 34.8±1.2** | 1.10±0.12** | 0.154±0.004** | 46.0±0.8** | 2.10±0.14** | ||

| ANOVA | Line | <0.001 | <0.01 | <0.001 | <0.001 | <0.01 | ||

| Year | ns | <0.001 | ns | <0.001 | <0.001 | |||

| Line×Year | <0.001 | ns | ns | <0.01 | ns |

Groups A and B represent plants in the Koshihikari and Takanari genetic background, respectively. NIL10 was developed from SL1235 and carries a Takanari chromosome segment from RM6128 to RM25840. Plants were sown on 11 April 2015, 18 April 2016, 6 June 2013, and 6 June 2014. Asterisks indicate significant difference from Koshihikari in A group, or from Takanari in B group at the *5% and **1% α level (n=4–6, Dunnett’s test). ns, not significant.

In the CSSLs with the Koshihikari background, SL1217, which harbors qHP4, had significantly higher values of all photosynthetic parameters measured than Koshihikari (Table 2) in one or both years. In contrast, NIL10, which harbors qHP10, had significantly higher gs but similar initial slope of the An–Ci curve (2015 only), and similar Asat and LNC to Koshihikari (Table 2). These QTL effects are consistent with the field results, in which qHP4 and qHP10 affected gs and qHP4 affected LNC (Fig. 4C, D). All CSSLs with the Takanari background had significantly higher Asat than Takanari in one or both years, and all except for SL1324 had significantly higher initial slope of the An–Ci curve in one or both years, while only SL1301 and SL1325 had significantly higher gs in one year, and SL1303, SL1311, and SL1325 had significantly higher LNC in one or both years (Table 2). These QTL effects were not observed in the field, except that qHP7b (associated with SL1325) affected LNC (Fig. 4D).

Plant or culm length, dry matter and grain production, and yield components of the plants carrying QTLs

In field experiments, SL1217 showed significantly shorter plant length and significantly lower dry weight of above-ground parts at harvest and grain yield than Koshihikari (Table 3); the lower grain yield was caused by the very small number of spikelets per panicle (Table 4). In contrast, in NIL10, plant length did not differ significantly from that of Koshihikari, but dry weight at harvest and grain yield were significantly larger than those of Koshihikari in both years (Table 3); the higher grain yield was caused by the larger number of panicles and spikelets per panicle (2013 only) (Table 4).

Table 3.

Comparisons of plant (culm) length, dry weight of above-ground parts at harvest (biomass), and grain yield of Koshihikari, Takanari, and CSSLs carrying QTLs for enhancing An; all plants were grown in the paddy field

| Group | Year | Cultivar, CSSL | QTL | Plant length (cm) | Culm length (cm) | Biomass (g m−2) | Grain yield (g m−2) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| A | 2016 | Koshihikari | 114.2±3.4 | — | 1421±39 | 585±18 | |

| SL1217 | qHP4 | 106.4±0.4** | — | 1321±42* | 542±20* | ||

| 2013 | Koshihikari | 112.3±0.4 | — | 1445±101 | 517±11 | ||

| NIL10 | qHP10 | 112.8±20.8 | — | 1804 ±183* | 664±13*** | ||

| 2014 | Koshihikari | 104.1±1.0 | — | 1547±31 | 564±35 | ||

| NIL10 | qHP10 | 103.9±0.8 | — | 1645±17*** | 642±12* | ||

| ANOVA | Line | ns | — | <0.01 | <0.001 | ||

| Year | <0.001 | — | ns | ns | |||

| Line×Year | ns | — | ns | <0.05 | |||

| B | 2015 | Takanari | — | 73.9±3.8 | 1329±129 | 513±30 | |

| SL1301 | qHP1a | — | 73.5±2.8 | 1455±113 | 647±49** | ||

| SL1303 | qHP1b | — | 91.5±14.5* | 1633±293† | 536±58 | ||

| SL1311 | qHP3b | — | 89.2±3.9* | 1359±114 | 534±49 | ||

| SL1324 | qHP7a | — | 72.6±1.8 | 1371±110 | 589±27 | ||

| SL1325 | qHP7b | — | 75.1±3.2 | 1461±133 | 612±54* | ||

| 2016 | Takanari | — | 76.2±2.2 | 1461±94 | 829±54 | ||

| SL1301 | qHP1a | — | 82.3±1.7 | 1502±26 | 735±24 | ||

| SL1303 | qHP1b | — | 97.4±3.4*** | 1640±95† | 709±39 | ||

| SL1311 | qHP3b | — | 86.5±2.9*** | 1268±119* | 631±113* | ||

| SL1324 | qHP7a | — | 75.0±1.4 | 1398±114 | 861±109 | ||

| SL1325 | qHP7b | — | 79.4±2.6 | 1373±100 | 847±82 | ||

| ANOVA | Line | — | <0.05 | <0.001 | <0.001 | ||

| Year | — | <0.001 | ns | <0.001 | |||

| Line×Year | — | ns | ns | <0.01 |

Groups A and B represent plants in the Koshihikari and Takanari genetic background, respectively. NIL10 was developed from SL1235 and carries a Takanari chromosome segment from RM6128 to RM25840. Plants were sown on 15 April 2013, 15 April 2014, 5 May 2015, and 6 May 2016. Grain yield was deterrmined at 14.5% moisture content. Symbols indicate significant differences from Koshihikari in Group A or Takanari in Group B at the †10%, *5%, or **1% α level (n=3 or 4, Dunnett’s test); ns, not significant.

Table 4.

Comparisons of yield components of Koshihikari, Takanari, and CSSLs carrying QTLs for enhanced An; all plants were grown in the paddy field

| Group | Year | Cultivar, CSSL | QTL | Panicle number (m−2) | Spikelet number per panicle | Ripening percentage (%) | 1000-grain weight (g) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| A | 2016 | Koshihikari | 297±12 | 103±2 | 90.8±1.4 | 21.1±0.1 | |

| SL1217 | qHP4 | 326±11* | 84±6*** | 94.2±1.9* | 21.1±0.6 | ||

| 2013 | Koshihikari | 281±8 | 107±6 | 81.0±3.2 | 21.3±0.5 | ||

| NIL10 | qHP10 | 332±8** | 119±3* | 83.7±2.5 | 20.0±0.5* | ||

| 2014 | Koshihikari | 290±11 | 104±2 | 87.9±3.8 | 21.4±0.3 | ||

| NIL10 | qHP10 | 338±6** | 104±1 | 90.3±2.7 | 20.2±0.1** | ||

| ANOVA | Line | <0.001 | <0.05 | ns | <0.001 | ||

| Year | ns | <0.01 | <0.01 | ns | |||

| Line×Year | ns | <0.05 | ns | ns | |||

| B | 2015 | Takanari | 166±46 | 262±58 | 66.3±2.5 | 18.7±0.3 | |

| SL1301 | qHP1a | 228±29 | 175±9† | 82.4±4.6* | 19.8±0.2** | ||

| SL1303 | qHP1b | 182±58 | 269±45 | 60.0±13.9 | 19.5±0.7† | ||

| SL1311 | qHP3b | 186±58 | 248±73 | 71.5±6.2 | 17.5±0.3** | ||

| SL1324 | qHP7a | 173±27 | 213±24 | 84.9±2.3** | 19.1±0.5 | ||

| SL1325 | qHP7b | 180 ±24 | 266±42 | 67.5±3.1 | 19.2±0.1 | ||

| 2016 | Takanari | 229±19 | 201±11 | 85.7±4.2 | 21.1±0.2 | ||

| SL1301 | qHP1a | 242±7 | 164±13*** | 85.8±5.3 | 21.6±0.3* | ||

| SL1303 | qHP1b | 183±16† | 215±9 | 86.2±5.3 | 21.0±0.3 | ||

| SL1311 | qHP3b | 228±44 | 204±11 | 71.8±2.1*** | 18.9±0.2*** | ||

| SL1324 | qHP7a | 269±33 | 174±5* | 90.2±0.6 | 20.4±0.2*** | ||

| SL1325 | qHP7b | 257±28 | 196±2 | 78.9±1.7† | 21.3±0.1 | ||

| ANOVA | Line | <0.10 | <0.001 | <0.001 | <0.001 | ||

| Year | <0.001 | <0.001 | <0.001 | <0.001 | |||

| Line×Year | <0.10 | ns | <0.001 | <0.05 |

Groups A and B represent plants in the Koshihikari and Takanari genetic background, respectively. NIL10 was developed from SL1235 and carries a Takanari chromosome segment from RM6128 to RM25840. Ripening percentage represents the ratio of the number of grains thicker than 1.8 mm to the total number of spikelets. Grain weight was deterrmined at 14.5% moisture content. Symbols indicate significant difference from Koshihikari in Group A, or from Takanari in Group B, at the †10%, *5%, and **1% α level (n=3 or 4, Dunnett’s test).

In SL1301 and SL1325, culm length and dry weight of above-ground parts at harvest did not differ from those of Takanari, and grain yield was significantly higher than that of Takanari in 2015 but not in 2016 (Table 3). One-thousand-grain weight was significantly larger in SL1301 than in Takanari in both years (Table 4). Panicle number per m2 tended to be larger in SL1325 than in Takanari in both years, although the differences were not significant (Table 4). In SL1311 and SL1324, dry weight of above ground parts at harvest and grain yield were similar to those of Takanari except for SL1311 in 2016, when ripening percentage and 1000-grain weight were also significantly smaller in SL1311. SL1303 showed large culm length and dry weight compared with Takanari in both years, with no significant difference in grain yield or yield components except for 1000-grain weight in 2015 and panicle number in 2016 (Tables 3, 4).

Effects of QTL pyramiding on An

We tested the effects of some QTL combinations. All combinations tested showed clear enhancements of An relative to plants carrying one QTL in the Koshihikari (Fig. 6A) or Takanari (Fig. 6B–D) background. The line carrying qHP4 and qHP10 in the Koshihikari background had 30% higher An than Koshihikari, comparable to the Takanari value (Fig. 6A).

Fig. 6.

Photosynthetic rate (An) of plants carrying Takanari allele(s) in the Koshihikari genetic background in 2016 (A) and Koshihikari allele(s) in the Takanari genetic background in 2015 (B–D) in the paddy field. Ca was controlled at 400±1 μmol mol−1 and other conditions were the same as in the field measurements in 2009–2012. Error bars represent SD (n=4). Bars with the same letter are not significantly different among the cultivar(s) and lines in each figure at the 10% α level (Tukey–Kramer test).

Discussion

We identified QTLs for leaf photosynthesis in rice by directly measuring leaf gas exchange and other relevant traits in the field, and then evaluated their effects using plants grown in pots. The use of two elite mapping populations that were recently developed by DNA marker-assisted selection (MAS) and of repeated trials over different years enabled us to identify reliable QTLs controlling the natural genetic variation of An. We examined the effects of pyramiding the various QTLs on An, and explored the associations between photosynthesis-related parameters and An and the associations between the An-enhancing QTLs and dry matter and grain production by using plants grown in the field and in pots.

Expression and pyramiding effects of QTLs for leaf photosynthesis

We detected 10 QTLs for An—qHP1a, qHP1b, qHP2, qHP3a, qHP3b, qHP4, qHP5, qHP7a, qHP7b, and qHP10—in at least two years by using BILs and CSSLs in the field (Fig. 4B). Among them, four QTLs (qHP1b, qHP4, qHP5, and qHP7b) were detected by using BILs as well as CSSLs, five QTLs (qHP1a, qHP2, qHP3b, qHP7a, and qHP10) were detected only by using CSSLs, and one QTL (qHP3a) was detected only by using BILs. By using CSSLs grown in pots, we confirmed that Takanari alleles at qHP4 and qHP10 increased An in plants with a Koshihikari background and that Koshihikari alleles at qHP1a, qHP1b, qHP3b, qHP7a, and qHP7b increased An in plants with a Takanari background (Table 2). These results indicate that reliable QTLs for enhanced An exist in rice. It is likely that qHP3a is expressed only following allelic interaction with other Koshihikari alleles, because the Koshihikari allele at this QTL was identified only in the populations with the Koshihikari background. There were two patterns of QTL expression: expression in plants with both genetic backgrounds (type I) and expression dependent on genetic background (type II). Both qHP4 and qHP7b are type I QTLs. qHP4 is located in a chromosomal region containing the GPS (GREEN FOR PHOTOSYNTHESIS) gene that Takai et al. (2013) identified by using the same BIL mapping population as we used. qHP4 is very effective at increasing An as the Takanari allele or decreasing An as the Koshihikari allele. On the other hand, qHP7b is as effective at increasing An as the Koshihikari allele or decreasing An as the Takanari allele. The other detected QTLs are type II QTLs. Effects of the Koshihikari allele at qHP3a and the Takanari alleles at qHP2 and qHP10 on An were consistently detected only in plants with a Koshihikari background, and effects of the Koshihikari alleles at qHP1a, qHP1b, qHP3b, qHP5, and qHP7a were consistently detected only in plants with a Takanari genetic background (Fig. 4B).

By using CSSLs derived from a cross between Koshihikari and Habataki, a sister cultivar of Takanari, Adachi et al. (2011b, 2014) detected four QTLs where Habataki alleles enhanced An in plants with a Koshihikari background. But despite using CSSLs derived from related materials, we detected only qHP4 (detected as qCAR4 by Adachi et al., 2014). The Habataki allele at qCAR5 on Chr. 5 enhanced An in plants with a Koshihikari background (Adachi et al., 2014); although qHP5 lies in the same region as qCAR5, in the current study the Takanari allele at qHP5 did not enhance An in the plants with a Koshihikari background, but the Koshihikari allele at qHP5 decreased An in the plants with a Takanari background. Thus, the expression of a type II QTL may be affected also by the combination of parents of the mapping population, although it remains to be seen whether qCAR5 and qHP5 are identical.

The value of An in a plant carrying only one Takanari allele (qHP2, qHP4, or qHP10) did not reach to the level of Takanari (Fig. 2). But the value of An in a plant carrying Takanari alleles of both qHP4 and qHP10 in the Koshihikari background increased to the level of Takanari (Fig. 6A), as it did in a plant carrying Habataki alleles of both qCAR4 and qCAR8 (Adachi et al., 2014). Similar pyramiding effects of Koshihikari alleles on An were observed in plants with the Takanari background (Fig. 6B–D). These results suggest that QTL effects on An are additive in introgression lines with both the Koshihikari background and the Takanari background, and in QTLs of type I as well as type II. Adachi et al. (2013) identified two rice lines with extremely high An (BTK-a and BTK-b) among the same BILs (Koshihikari/Takanari//Takanari). From the genotypes and our results, it is clear that BTK-a carries Koshihikari alleles of qHP1b, qHP3b, qHP7a, and qHP7b (Fig. 7). This observation suggests that An of plants with a Takanari background could be increased by more than 20% above that of Takanari by introgression of Koshihikari alleles. The genetic basis of both types I and II QTL expression should be a target for future research to enhance An.

Fig. 7.

Graphical genotype of line BTK-a, with extremely high An, which was identified previously among the BILs (Koshihikari/Takanari//Takanari) by Adachi et al. (2013). Black, homozygous for Koshihikari; white, homozygous for Takanari. Boxes: QTLs for An located on the Koshihikari homozygous region in BTK-a. An, initial slope of the An–Ci curve, and Asat of BTK-a were ~25–30% higher than those of Takanari (Adachi et al., 2013).

Causes of the increase in An by Koshihikari and Takanari alleles

The rate of photosynthesis in rice is controlled by gs, gm, the capacity of Rubisco to consume RuBP, and the capacity of RuBP regeneration (Farquhar et al., 1980; Terashima et al., 2011). Takanari had a higher gs, higher initial slope of the An–Ci curve, and higher LNC than Koshihikari (Fig. 5). The initial slope of the An–Ci curve is associated with the combination of Rubisco capacity and gm (Sharkey et al., 2007; Adachi et al., 2013). We suggest that Takanari has a higher An than Koshihikari owing to its higher gs and its higher capacity of Rubisco to consume RuBP (Hirasawa et al., 2010), although we did not examine gm. The Takanari alleles at qHP4 were associated with the increased gs, initial slope of the An–Ci curve, and Asat in SL1217, and that at qHP10 was associated with the increased gs in NIL10 (Table 2). The increases in gs and initial slope of the An–Ci curve are likely due to the Takanari alleles. However, the higher Asat might be due to the combination of the Takanari allele of qHP4 with the Koshihikari genetic background, because Takanari did not have a significantly higher Asat than Koshihikari (Fig. 5).

Although gs, the initial slope of the An–Ci curve, and LNC were smaller in Koshihikari than in Takanari, and there was no difference in Asat between Koshihikari and Takanari (Fig. 5), some Koshihikari alleles increased gs (at qHP1a and qHP7b), the initial slope of the An–Ci curve (at qHP1a, qHP1b, qHP3b, and qHP7b), and Asat (at qHP1a, qHP1b, qHP3b, qHP7a, and qHP7b) in the plants with a Takanari genetic background grown in pots (Table 2). Some of the increase might be caused by the increase in LNC, as reported previously (Makino et al., 1994; Yamori et al., 2011). It is interesting to note that the correlation between LNC and An was lower in K-CSSLs than in T-CSSLs, or was not significant (Supplementary Fig. S4). The combination of a Koshihikari allele with the Takanari background may enhance the initial slope of the An–Ci curve or Asat without increasing LNC (Table 2). Increased gm was a cause of the much higher An in BTK-a and BTK-b than in Takanari (Adachi et al., 2013).

Phenology may affect An through weather conditions and soil properties. However, in the current study, the difference in days to heading from sowing (DTH) between Koshihikari and plants carrying QTLs for enhancing An in the Koshihikari background and between Takanari and plants carrying QTLs enhancing An in Takanari background was within 11 d (see Supplementary Figs S9, S10). SL1208 showed heading 10–11 d later than Koshihikari and, on the contrary, SL1311 and SL1324 showed heading 7–10 d earlier than Takanari in 2011 and 2012 (Supplementary Figs S9, S10). No significant correlations were observed between DTH and An except for T-CSSLs in 2012 (Supplementary Fig. S11). These results suggest that An measured in the current research was affected not by differences in phenology, but by genetic properties.

Our findings suggest that An and traits relevant to An (gs, gm, Rubisco capacity, or RuBP regeneration) can be improved beyond the level of the parent cultivar by combining a Takanari allele with the Koshihikari genetic background or a Koshihikari allele with the Takanari genetic background. The genetic basis of the effects of the QTL alleles and genetic background on diffusion and biochemical capacities should be a target in future research.

Effects of the QTLs on dry matter and grain production

The enhanced An is expected to increase dry matter and grain production through increased carbon gain of plants. In fact, NIL10, a line carrying a qHP10 region in the Koshihikari background, produced heavier dry matter of above-ground parts at harvest and showed higher grain yield than in Koshihikari across two years (Table 3). However, if other traits relevant to dry matter production and grain yield are affected by the QTL for An, known as pleiotropic effects, dry matter production and grain yield also might be affected by them. It was shown in the previous report that the An-enhancing QTL, qCAR8, promoted the earlier heading resulting in shorter growth period and as a result, produced small dry matter at harvest (Adachi et al., 2017). Similarly, in this research, SL1311 and SL1324 displayed earlier heading than Takanari and showed no enhancement of dry matter production. Plant height affects dry matter production through canopy architecture (Ookawa et al., 2010). SL1217 with shorter canopy produced smaller dry matter than Koshihikari and, on the other hand, SL1303 with taller canopy produced heavier dry matter than Takanari (Table 3). Dry matter production is a highly complex trait, which is determined not only by An as measured in the current research, but also by phenology, leaf area and architecture of the canopy (Gardner et al., 1985; Hay and Porter, 2006). To elucidate how each QTL allele identified here is associated with dry matter production and grain yield, detailed investigation on leaf area development, which affects light interception of the canopy, and canopy architecture, which affects light penetration and CO2 diffusion into the canopy as well as individual leaf photosynthesis in the canopy, are required (Hirasawa, 2014).

Toward a comprehensive understanding of the genetic control of rice An

Several QTLs for enhanced An have been reported previously (Teng et al., 2004; Hu et al., 2009; Adachi et al., 2011a; Gu et al., 2012). Except for QTLs (qHP4 and qHP5) identified by using relevant mapping populations (Adachi et al., 2011a), no QTLs for An or traits relevant to An that have been identified using different mapping populations to those used here (Ishimaru et al., 2001; Ogawa et al., 2016) share the same position as those identified here. This is probably because of the strong dependence on the combination of allele and genetic background. The comprehensive information on the genetic components of An in Koshihikari and Takanari that we have identified will be useful for understanding the genetic basis of rice An. The first step will be to clone the genes underlying the QTLs to understand the molecular mechanisms of their functions. The QTLs detected repeatedly over several years (qHP1a, qHP1b, qHP3b, qHP7a, qHP7b, and qHP10) would be good targets for fine mapping by MAS. The second step will be to develop predictive genetic models for selecting plants with appropriate combinations of genes. Genomic selection, a newly developed strategy for crop selection on the basis of haplotype, relies on a training model developed from phenotypic and genotypic data (Heffner et al., 2009; Jannink et al., 2010). QTLs for gs and LNC, which did not always correspond to QTLs for high An (Fig. 4C, D), could be incorporated in connection to the higher An in the model. QTL information presented here could be used to improve prediction models. Furthermore, ‘omics’ approaches, including transcriptome and metabolome analyses, can bridge the gap between genomes and phenotypes (Kuroha et al., 2017). Information on the causal genes will help to explain how the genome controls An in field-grown plants. For a comprehensive understanding of the genetic components of rice An, using mapping populations from other combinations of cultivars and genome-wide association study are promising. Our study, which demonstrated several types of QTL for An based on genetic and environmental background, will provide a guide for future studies evaluating the applicability of estimated QTLs to rice breeding programs.

Conclusions

We found several reliable QTLs for enhanced An in rice. Pyramiding the QTLs greatly enhanced An. An was increased in the high-quality japonica cultivar Koshihikari with a low An by introducing alleles from the high-yielding indica cultivar Takanari with a high An; furthermore, the An of the high-An cultivar Takanari could be increased further by introducing alleles of the low-An cultivar Koshihikari. However, the effects of many QTLs for enhanced An were limited to specific combinations of allele and genetic background. Prediction modeling and gene mapping would contribute to the selection of plants or genomes for further increasing An. By characterizing the effects of each QTL on An and other traits associated with rice production, such as leaf area development, canopy structure, and earliness of heading, breeders could use alleles that enhance An in programs to improve rice productivity.

Supplementary data

Supplementary data are available at JXB online.

Fig. S1. Genotype and photosynthetic rate of lines used for narrowing down QTL regions on chromosomes 7 and 10.

Fig. S2. Frequency distributions of stomatal conductance and leaf nitrogen content of BILs with Koshihikari background and Takanari background in 2009.

Fig. S3. Relationships between stomatal conductance and photosynthetic rate (An), and between leaf nitrogen content and An, in BKTs and BTKs.

Fig. S4. Relationships between stomatal conductance and photosynthetic rate (An), and between leaf nitrogen content and An, in T-CSSLs and K-CSSLs.

Fig. S5. Stomatal conductance of flag leaves at full heading stage of T-CSSLs (Koshihikari background).

Fig. S6. Leaf nitrogen content of flag leaves at full heading stage of T-CSSLs (Koshihikari background).

Fig. S7. Stomatal conductance of flag leaves at full heading stage of K-CSSLs (Takanari background).

Fig. S8. Leaf nitrogen content of flag leaves at full heading stage of K-CSSLs (Takanari background).

Fig. S9. Days to heading from sowing of T-CSSLs (Koshihikari background).

Fig. S10. Days to heading from sowing of K-CSSLs (Takanari background).

Fig. S11. Relationships between days to heading from sowing and photosynthetic rate in T-CSSLs and K-CSSLs in 2011 and 2012.

Table S1. Averaged value of photosynthetic rate, stomatal conductance and leaf nitrogen content and genotypes for the BILs.

Table S2. Heading date of Koshihikari and Takanari.

Table S3. Genomic locations of QTLs for enhanced flag leaf photosynthesis estimated by using CSSLs and by narrowing down with further crosses.

Table S4. QTLs for stomatal conductance estimated by using BILs.

Table S5. QTLs for leaf nitrogen content estimated by using BILs.

Acknowledgements

This work was supported in part by Grants-in-Aid from the Ministry of Education, Culture, Sports, Science and Technology of Japan (no. 25252007 to TH), the Ministry of Agriculture, Forestry and Fisheries of Japan (Genomics-based Technology for Agricultural Improvement, RBS2006 to TY and TH), and the Japan Science and Technology Agency (PRESTO, JPMJPR13B1, and CREST, JPMJCR15O2, to SA).

Glossary

Abbreviations

- An

net photosynthetic rate

- Asat

net photosynthetic rate at CO2 saturation

- Ca

ambient CO2 concentration in the assimilation chamber

- Ci

intercellular CO2 concentration

- DTH

days to heading from sowing

- gs

stomatal conductance

- gm

mesophyll conductance

- LAI

leaf area index

- LNC

leaf nitrogen content

- MAS

marker-assisted selection

- QTL

quantitative trait locus

- RuBP

ribulose-1,5-bisphosphate.

References

- Adachi S, Baptista LZ, Sueyoshi T, Murata K, Yamamoto T, Ebitani T, Ookawa T, Hirasawa T. 2014. Introgression of two chromosome regions for leaf photosynthesis from an indica rice into the genetic background of a japonica rice. Journal of Experimental Botany 65, 2049–2056. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Adachi S, Nakae T, Uchida M, et al. 2013. The mesophyll anatomy enhancing CO2 diffusion is a key trait for improving rice photosynthesis. Journal of Experimental Botany 64, 1061–1072. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Adachi S, Nito N, Kondo M, Yamamoto T, Arai-Sanoh Y, Ando T, Ookawa T, Yano M, Hirasawa T. 2011a Identification of chromosomal regions controlling the leaf photosynthetic rate in rice by using a progeny from japonica and high-yielding indica varieties. Plant Production Science 14, 118–127. [Google Scholar]

- Adachi S, Tsuru Y, Nito N, Murata K, Yamamoto T, Ebitani T, Ookawa T, Hirasawa T. 2011b Identification and characterization of genomic regions on chromosomes 4 and 8 that control the rate of photosynthesis in rice leaves. Journal of Experimental Botany 62, 1927–1938. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Adachi S, Yoshikawa K, Yamanouchi U, Tanabata T, Sun J, Ookawa T, Yamamoto T, Sage RF, Hirasawa T, Yonemaru J. 2017. Fine mapping of Carbon Assimilation Rate 8, a quantitative trait locus for flag leaf nitrogen content, stomatal conductance and photosynthesis in rice. Frontiers in Plant Science 8, 60. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ashikari M, Sakakibara H, Lin S, Yamamoto T, Takashi T, Nishimura A, Angeles ER, Qian Q, Kitano H, Matsuoka M. 2005. Cytokinin oxidase regulates rice grain production. Science 309, 741–745. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cook MG, Evans LT. 1983. Some physiological aspects of the domestication and improvement of rice. Field Crops Research 6, 219–238. [Google Scholar]

- Farquhar GD, von Caemmerer S, Berry JA. 1980. A biochemical model of photosynthetic CO2 assimilation in leaves of C3 species. Planta 149, 78–90. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Flood PJ, Harbinson J, Aarts MGM. 2011. Natural genetic variation in plant photosynthesis. Trends in Plant Science 16, 327–335. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fukuda A, Kondo K, Ikka T, Takai T, Tanabata T, Yamamoto T. 2018. A novel QTL associated with rice canopy temperature difference affects stomatal conductance and leaf photosynthesis. Breeding Science 68, 305–315. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fukushima A, Ohta H, Yokogami N, Tsudsa N, Yoshida A, Kyozuka J, Maekawa M. 2017. Effects of genes increasing the number of spikelets per panicle, TAW1 and APO1, on yield and yield-related traits in rice. Plant Production Science 20, 485–489. [Google Scholar]

- Gardner FP, Pearce RB, Mitchell RL. 1985. Physiology of crop plants. Ames: Iowa University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Gu J, Yin X, Stomph TJ, Struik PC. 2014. Can exploiting natural genetic variation in leaf photosynthesis contribute to increasing rice productivity? A simulation analysis. Plant, Cell & Environment 37, 22–34. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gu J, Yin X, Struik PC, Stomph TJ, Wang H. 2012. Using chromosome introgression lines to map quantitative trait loci for photosynthesis parameters in rice (Oryza sativa L.) leaves under drought and well-watered field conditions. Journal of Experimental Botany 63, 455–469. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hay RKM, Porter JR. 2006. The physiology of crop yield. Oxford: Blackwell. [Google Scholar]

- Heffner EL, Sorrells ME, Jannish J-L. 2009. Genomic selection for crop improvement. Crop Science 48, 1–12. [Google Scholar]

- Hirasawa T. 2014. Photosynthesis and biomass production in energy crops. In: Tojo S, Hirasawa T, eds. Research approaches to sustainable biomass systems. Oxford: Elsevier, 52–61. [Google Scholar]

- Hirasawa T, Ozawa S, Taylaran RD, Ookawa T. 2010. Varietal differences in photosynthetic rates in rice plants, with special reference to the nitrogen content of leaves. Plant Production Science 13, 53–57. [Google Scholar]

- Horton P. 2000. Prospects for crop improvement through the genetic manipulation of photosynthesis: morphological and biochemical aspects of light capture. Journal of Experimental Botany 51, Issue suppl 1, 475–485. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hu SP, Zhou Y, Zhang L, Zhu XD, Li L, Luo LJ, Liu GL, Zhou QM. 2009. Correlation and quantitative trait loci analyses of total chlorophyll content and photosynthetic rate of rice (Oryza sativa) under water stress and well-watered conditions. Journal of Integrative Plant Biology 51, 879–888. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huang X, Qian Q, Liu Z, Sun H, He S, Luo D, Xia G, Chu C, Li J, Fu X. 2009. Natural variation at the DEP1 locus enhances grain yield in rice. Nature Genetics 41, 494–497. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hubbart S, Peng S, Horton P, Chen Y, Murchie EH. 2007. Trends in leaf photosynthesis in historical rice varieties developed in the Philippines since 1966. Journal of Experimental Botany 58, 3429–3438. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ikeda-Kawakatsu K, Yasuno N, Oikawa T, Iida S, Nagato Y, Maekawa M, Kyozuka J. 2009. Expression level of ABERRANT PANICLE ORGANIZATION1 determines rice inflorescence form through control of cell proliferation in the meristem. Plant Physiology 150, 736–747. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ishimaru K, Kobayashi N, Ono K, Yano M, Ohsugi R. 2001. Are contents of Rubisco, soluble protein and nitrogen in flag leaves of rice controlled by the same genetics? Journal of Experimental Botany 52, 1827–1833. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jahn CE, Mckay JK, Mauleon R, Stephens J, McNally KL, Bush DR, Leung H, Leach JE. 2011. Genetic variation in biomass traits among 20 diverse rice varieties. Plant Physiology 155, 157–168. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jannink JL, Lorenz AJ, Iwata H. 2010. Genomic selection in plant breeding: from theory to practice. Briefings in Functional Genomics 9, 166–177. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kanemura T, Homma K, Ohsumi A, Shiraiwa T, Horie T. 2007. Evaluation of genotypic variation in leaf photosynthetic rate and its associated factors by using rice diversity research set of germplasm. Photosynthesis Research 94, 23–30. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kebeish R, Niessen M, Thiruveedhi K, Bari R, Hirsch HJ, Rosenkranz R, Stäbler N, Schönfeld B, Kreuzaler F, Peterhänsel C. 2007. Chloroplastic photorespiratory bypass increases photosynthesis and biomass production in Arabidopsis thaliana. Nature Biotechnology 25, 593–599. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Khush GS. 1999. Green revolution: preparing for the 21st century. Genome 42, 646–655. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kromdijk J, Głowacka K, Leonelli L, Gabilly ST, Iwai M, Niyogi KK, Long SP. 2016. Improving photosynthesis and crop productivity by accelerating recovery from photoprotection. Science 354, 857–861. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kumura A. 1995. Physiology of high-yielding rice plants from the viewpoint of dry matter production and its partitioning. In: Matsuo T, Kumazawa K, Ishii R, Ishihara K, Hirata H, eds. Science of the rice plant, Vol. 2. Physiology. Tokyo: Food and Agriculture Policy Research Center, 704–736. [Google Scholar]

- Kuroda E, Kumura A. 1990. Difference in single-leaf photosynthesis between old and new rice varieties. III. Physiological bases of varietal difference in single-leaf photosynthesis between varieties viewed from nitrogen content and the nitrogen-photosynthesis relationship. Japanese Journal of Crop Science 59, 298–302. [Google Scholar]

- Kuroha T, Nagai K, Kurokawa Y, Nagamura Y, Kusano M, Yasui H, Ashikari M, Fukushima A. 2017. eQTLs regulating transcript variations associated with rapid internode elongation in deepwater rice. Frontiers in Plant Science 8, 1753. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Long SP, Marshall-Colon A, Zhu XG. 2015. Meeting the global food demand of the future by engineering crop photosynthesis and yield potential. Cell 161, 56–66. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Makino A. 2011. Photosynthesis, grain yield, and nitrogen utilization in rice and wheat. Plant Physiology 155, 125–129. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Makino A, Nakano H, Mae T. 1994. Effects of growth temperature on the responses of ribulose-1,5-biphosphate carboxylase, electron transport components, and sucrose synthesis enzymes to leaf nitrogen in rice, and their relationships to photosynthesis. Plant Physiology 105, 1231–1238. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mann CC. 1999. Crop scientists seek a new revolution. Science 283, 310–314. [Google Scholar]

- Miura K, Ikeda M, Matsubara A, Song XJ, Ito M, Asano K, Matsuoka M, Kitano H, Ashikari M. 2010. OsSPL14 promotes panicle branching and higher grain productivity in rice. Nature Genetics 42, 545–549. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Murata Y. 1961. Studies on the photosynthesis of rice plants and its culture significance. Bulletin of National Institute of Agricultural Science D9, 1–169. [Google Scholar]

- Ohsumi A, Hamasaki A, Nakagawa H, Yoshida H, Shiraiwa T, Horie T. 2007. A model explaining genotypic and ontogenetic variation of leaf photosynthetic rate in rice (Oryza sativa) based on leaf nitrogen content and stomatal conductance. Annals of Botany 99, 265–273. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ohsumi A, Takai T, Ida M, Yamamoto T, Arai-Sanoh Y, Yano M, Ando T, Kondo M. 2011. Evaluation of yield performance in rice near-isogenic lines with increased spikelet number. Field Crops Research 120, 68–75. [Google Scholar]

- Ogawa S, Valencia MO, Lorieux M, Arbelaez JD, McCouch S, Ishitani M, Selvaraj MG. 2016. Identification of QTLs associated with agronomic performance under nitrogen-deficient conditions using chromosome segment substitution lines of a wild rice relative, Oryza rufipogon. Acta Physiologiae Plantarum 38, 103. [Google Scholar]

- Ookawa T, Yasuda K, Seto M, Sunaga K, Kato H, Sakai M, Motobayashi T, Hirasawa T. 2010. Biomass production and lodging resistance in ‘Leaf Star’, a new long-culm rice forage cultivar. Plant Production Science 13, 58–66. [Google Scholar]

- Ort DR, Merchant SS, Alric J, et al. 2015. Redesigning photosynthesis to sustainably meet global food and bioenergy demand. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, USA 112, 8529–8536. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Parry MAJ, Reynolds M, Salvucci ME, Raines C, Andralojc PJ, Zhu XG, Price GD, Condon AG, Furbank RT. 2011. Raising yield potential of wheat. II. Increasing photosynthetic capacity and efficiency. Journal of Experimental Botany 62, 453–467. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Raines CA. 2011. Increasing photosynthetic carbon assimilation in C3 plants to improve crop yield: current and future strategies. Plant Physiology 155, 36–42. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ray DK, Mueller ND, West PC, Foley JA. 2013. Yield trends are insufficient to double global crop production by 2050. PLoS One 8, e66428. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reynolds M, Bonnett D, Chapman SC, Furbank RT, Manès Y, Mather DE, Parry MAJ. 2011. Raising yield potential of wheat. I. Overview of a consortium approach and breeding strategies. Journal of Experimental Botany 62, 439–452. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sage RF, Adachi S, Hirasawa T. 2017. Improving photosynthesis in rice: from small steps to giant leaps. In: Sasaki T, ed. Achieving sustainable cultivation of rice, Vol. 1. Breeding for higher yield and quality. Cambridge: Burleigh Dodds Science Publishing, 77–107. [Google Scholar]

- Sage RF, Zhu XG. 2011. Exploiting the engine of C4 photosynthesis. Journal of Experimental Botany 62, 2989–3000. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sasaki H, Ishii R. 1992. Cultivar differences in leaf photosynthesis of rice bred in Japan. Photosynthesis Research 32, 139–146. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sasaki H, Samejima M, Ishii R. 1996. Analysis by δ 13C measurement on mechanism of cultivar difference in leaf photosynthesis of rice (Oryza sativa L.). Plant & Cell Physiology 37, 1161–1166. [Google Scholar]

- Sharkey TD, Bernacchi CJ, Farquhar GD, Singsaas EL. 2007. Fitting photosynthetic carbon dioxide response curves for C3 leaves. Plant, Cell & Environment 30, 1035–1040. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Simkin AJ, McAusland L, Headland LR, Lawson T, Raines CA. 2015. Multigene manipulation of photosynthetic carbon assimilation increases CO2 fixation and biomass yield in tobacco. Journal of Experimental Botany 66, 4075–4090. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Takai T, Adachi S, Taguchi-Shiobara F, et al. 2013. A natural variant of NAL1, selected in high-yield rice breeding programs, pleiotropically increases photosynthesis rate. Scientific Reports 3, 2149. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Takai T, Ikka T, Kondo K, et al. 2014. Genetic mechanisms underlying yield potential in the rice high-yielding cultivar Takanari, based on reciprocal chromosome segment substitution lines. BMC Plant Biology 14, 295. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Taylaran RD, Adachi S, Ookawa T, Usuda H, Hirasawa T. 2011. Hydraulic conductance as well as nitrogen accumulation plays a role in the higher rate of leaf photosynthesis of the most productive variety of rice in Japan. Journal of Experimental Botany 62, 4067–4077. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Taylaran RD, Ozawa S, Miyamoto N, Ookawa T, Motobayashi T, Hirasawa T. 2009. Performance of a high-yielding modern rice cultivar Takanari and several old and new cultivars grown with and without chemical fertilizer in a submerged paddy field. Plant Production Science 12, 365–380. [Google Scholar]

- Teng S, Qian Q, Zeng D, Kunihiro Y, Fujimoto K, Huang D, Zhu L. 2004. QTL analysis of leaf photosynthetic rate and related physiological traits in rice (Oryza sativa L.). Euphytica 135, 1–7. [Google Scholar]

- Terashima I, Hanba YT, Tholen D, Niinemets Ü. 2011. Leaf functional anatomy in relation to photosynthesis. Plant Physiology 155, 108–116. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- van Bezouw RFHM, Keurentjes JJB, Harbinson J, Aarts MGM. 2019. Converging phenomics and genomics to study natural variation in plant photosynthetic efficiency. The Plant Journal 97, 112–133. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang S, Basten CJ, Zeng ZB. 2005. Windows QTL cartographer 2.5. Raleigh, NC: Department of Statistics, North Carolina State University; http://statgen.ncsu.edu/qtlcart/WQTLCart.htm. [Google Scholar]

- Yamori W, Nagai T, Makino A. 2011. The rate-limiting step for CO2 assimilation at different temperatures is influenced by the leaf nitrogen content in several C3 crop species. Plant, Cell & Environment 34, 764–777. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yoshida A, Sasao M, Yasuno N, et al. 2013. TAWAWA1, a regulator of rice inflorescence architecture, functions through the suppression of meristem phase transition. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, USA 110, 767–772. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhu XG, Long SP, Ort DR. 2008. What is the maximum efficiency with which photosynthesis can convert solar energy into biomass? Current Opinion in Biotechnology 19, 153–159. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhu XG, Long SP, Ort DR. 2010. Improving photosynthetic efficiency for greater yield. Annual Review of Plant Biology 61, 235–261. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.