Abstract

The Kv3.1 channel subunit, when expressed heterologously, gives rise to a high-threshold noninactivating potassium current. Experiments with auditory neurons have suggested that the presence of this channel subunit enables them to fire action potentials at high frequencies. We have found that the expression levels of Kv3.1 transcripts increase in inferior colliculus neurons before the onset of hearing and then remain relatively constant. Because spontaneous neuronal activity plays an important role in modulating neuronal excitability during development, we examined the effects of depolarization with an elevated concentration of external potassium ions on the expression of Kv3.1 channel subunits in immature inferior colliculus neurons. Elevated potassium produced a marked increase in Kv3.1 mRNA levels and in the amplitude of a high-threshold, noninactivating current before the onset of hearing. This increase was prevented by the presence of a calcium channel blocker, indicating that calcium influx mediated the depolarization-induced increase in this current. In contrast, treatment with an elevated external potassium concentration caused only a moderate increase in the peak amplitude of a lower-threshold inactivating current. The repolarization of action potentials in the high-potassium-treated cells was more rapid and complete than in the control cells. Computer simulations confirmed that this change could be explained by a change in Kv3.1-like current of the same magnitude as recorded in voltage-clamp experiments. Thus, depolarization and calcium influx may alter the excitability of immature inferior colliculus neurons by selectively increasing the levels of a Kv3.1-like potassium current.

Keywords: potassium channel, expression, depolarization, inferior colliculus, Kv3.1, calcium

Neuronal activity plays an important role in the development of the CNS. Both spontaneously generated and experience-dependent neuronal activity are essential for the functional and structural maturation of connections in the visual system (Katz and Shatz, 1996). The intrinsic membrane properties of neurons also undergo dynamic changes during development. One of the mechanisms underlying such changes is the regulation of the levels of potassium channels. Whether neuronal activity regulates the expression of potassium channels during development, however, remains largely unknown.

One potassium channel subunit that regulates the excitability of rapidly firing neurons is the Shaw-type channel, Kv3.1. The Kv3.1 gene gives rise to two transcripts: Kv3.1a and Kv3.1b (Luneau et al., 1991). Although the Kv3.1a and Kv3.1b proteins differ at the C terminus, they both produce high-threshold noninactivating delayed-rectifier currents when expressed heterologously (Yokoyama et al., 1989; Kanemasa et al., 1995). Kv3.1 mRNA and protein are expressed in a subpopulation of neurons in brain (Perney et al., 1992; Weiser et al., 1995). Some of the neurons that contain the Kv3.1 protein have also been demonstrated to possess a high-threshold, noninactivating Kv3.1-like current and are capable of firing action potentials at a rapid rate (Brew and Forsythe, 1995; Du et al., 1996; Massengill et al., 1997; Wang et al., 1998). Experimental evidence and computer simulations suggest that repolarization of action potentials by Kv3.1-like currents minimizes the relative refractory period, enabling these neurons to fire at increased frequencies (Massengill et al., 1997; Perney and Kaczmarek, 1997). Moreover, pharmacological elimination of the high-threshold Kv3.1-like current in auditory neurons specifically reduces their ability to follow high-frequency stimulation (Wang et al., 1998).

The inferior colliculus is a major relay center along auditory pathways (Morest and Oliver, 1983; Oliver and Shneiderman, 1991) and is developmentally plastic (Feldman et al., 1996). Studies of the tonotopic organization of the inferior colliculus have suggested that the ability of the colliculus to respond to higher sound frequency inputs occurs later in development than the response to lower frequencies and that this may be related to the maturation of the cochlea (Ehret and Romand, 1994; Pierson and Snyder-Keller, 1994). However, maturation of the intrinsic excitability of inferior colliculus neurons may also contribute to the developmental changes in this region. Because all the neurons in the inferior colliculus express Kv3.1 mRNA and protein (Perney et al., 1992; Weiser et al., 1994), one possible mechanism underlying developmental changes in this region is an increase in the expression level of Kv3.1.

Depolarization with external potassium ions increases the levels of Kv3.1 mRNA in AtT20 cells and upregulates the activity of the Kv3.1 promoter (Perney and Kaczmarek, 1993; Gan et al., 1996). However, whether depolarization affects the expression of the Kv3.1 potassium channel in auditory neurons during development is not yet known. As in the visual system, spontaneous activity has been observed in the auditory system before the onset of hearing (Kotak and Sanes, 1995). In the present study we have investigated whether depolarization by potassium ions regulates the expression of Kv3.1 in inferior colliculus neurons during maturation and whether it influences the firing properties of these neurons.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Preparation and incubation of slices of inferior colliculus. Inferior colliculi were obtained from decapitated 3- to 30-d-old Sprague–Dawley rats and placed in standard artificial CSF (ACSF) containing (in mm): 125 NaCl, 2.5 KCl, 26 NaHCO3, 1.25 NaH2PO4, 2 CaCl2, 1 MgCl2, 10 glucose, pH 7.4, which was bubbled continuously with a 95% O2 and 5% CO2 mixture. The inferior colliculus was cut into slices (300–500 μm) in ice-cold ACSF solution, and the slices were then incubated in ACSF, in high-K ACSF (77.5 mm NaCl and 50 mm KCl with the other components unchanged), or in high-K ACSF containing 1 mm Cd2+ and 2 mm EGTA at room temperature for 6 hr. In experiments using isolated neurons of the inferior colliculus, we found that elevation of the external potassium ion concentration to 50 mmdepolarized the cells from their resting potential to approximately −29 mV, a value close to the predicted equilibrium potential for potassium ions. For convenience we shall refer to the incubation of inferior colliculus slices in high-K ACSF as “depolarization.”

Deoxyglucose uptake assay. We tested the viability of inferior colliculus slices incubated in ACSF by measuring their uptake of 2-deoxy-[1-3H]-glucose ([3H]DG) (Amersham, Arlington Heights, IL), as described previously (Liu and Kaczmarek, 1998). Briefly, inferior colliculi were dissected from rats, cut into halves, and then weighed and sliced. Half of the slices were incubated with [3H]DG in ACSF at 0°C, and the other half were incubated at room temperature, both for 40 min. The slices were then washed three times in ice-cold ACSF and homogenized in 1% SDS. The levels of [3H]DG were then measured by liquid scintillation counting. The ratio of [3H]DG uptake at room temperature relative to that at 0°C (RDG) was used to evaluate the viability of slices (see Table 1). In a separate series of experiments, slices were incubated in oxygenated ACSF for 6 hr at room temperature, before the [3H]DG uptake assay.RDG values from these slices were not significantly different from those without subsequent incubation in ACSF (see Table 1), indicating that inferior colliculus slices from postnatal rats remain viable for a period of 6 hr in ACSF.

Table 1.

Effect of incubation in ACSF on the deoxyglucose uptake

| Treatment | Deoxyglucose uptake at room temperature/deoxyglucose uptake at 0°C | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| P3 | P8–9 | P15–16 | P38 | |||||

| Mean ± SE | n | Mean ± SE | n | Mean ± SE | n | Mean ± SE | n | |

| No treatment | 3.02 ± 0.99 | 3 | 5.71 ± 0.95 | 4 | 4.57 ± 2.11 | 3 | 3.85 ± 0.78 | 2 |

| ACSF (6 hr) | 2.63 ± 0.34 | 4 | 5.44 ± 0.93 | 4 | 3.6 ± 1.09 | 3 | 3.79 ± 0.68 | 3 |

RNase protection assay. RNA was isolated from inferior colliculus slices immediately after each rat was killed (t = 0) or after 6 hr incubation in ACSF or in high-K ACSF. Total RNA was isolated from each sample by the guanidinium thiocyanate acid phenol–chloroform method (Chomcyznski and Sacchi, 1987), and RNA concentrations were measured using a spectrophotometer. Plasmid DNA containing the coding region of the Kv3.1b gene subcloned into pGEM-A (Luneau et al., 1991) was digested with PvuII. [32P]CTP-labeled antisense RNA probe was transcribed with SP6 polymerase, using the linearized plasmid as the DNA template. This probe (413 base pairs) is complementary to the 108 bases of the 3′ end of Kv3.1a and to the 398 bases of Kv3.1b mRNA (Perney et al., 1992) and was used to measure the levels of the Kv3.1a and Kv3.1b transcripts. Linearized pTRI-GAPDH-rat (Ambion) was used as a DNA template to generate an antisense mRNA (434 base pairs) that hybridized with a 316 base fragment of the glyceraldehyde 3-phosphate dehydrogenase (GAPDH) RNA (a housekeeping enzyme). The levels of GAPDH mRNA were measured and used as an internal control. The RNase protection assay was performed using published procedures (Ausubel et al., 1990). Total RNA (5 μg) isolated from inferior colliculus of postnatal day 3 (P3), P8, P15, or P33–40 was hybridized with [32P]CTP-labeled antisense RNA probes. The amount of probe used in this experiment was in molar excess of the RNA in samples of all ages, because when 10 μg of total RNA was hybridized with the same amount of antisense RNA probes, higher densitometric intensity values of the Kv3.1- and GAPDH-protected bands were obtained at each age (data not shown).

The amount of radioactivity in each band was visualized by autoradiography and was quantified on a densitometer by integrating the area under the peak. In a previous study, we determined that the range of densitometric readings that were linearly proportional to the radioactivity of the bands is between 500 and 7000 U (Liu and Kaczmarek, 1998). Therefore, in each experiment the gel was exposed to x-ray film for varying lengths of time. Only when the densitometric intensity values of the Kv3.1- and GAPDH-protected bands were within the linear range were the data used for further analysis. The relative levels of Kv3.1a and Kv3.1b mRNA were calculated by dividing the intensity of the Kv3.1a or Kv3.1b band by the intensity of the GAPDH band. In addition to the protected bands corresponding to Kv3.1a [108 nucleotide (nt)], Kv3.1b (434 nt), and GAPDH (316 nt), several other bands were also present. These bands have been seen when GAPDH probe was not used (Perney et al., 1992), and the intensities of these bands did not vary in proportion to the intensity of bands corresponding to Kv3.1 b mRNA (Liu and Kaczmarek, 1998). Thus these protected bands could not be the degradation products of GAPDH or Kv3.1b mRNA and should not affect the measurement of Kv3.1a and Kv3.1b mRNA levels.

Isolation of inferior colliculus neurons from slices. After incubation in ACSF, high-K ACSF, or high-K ACSF containing 1 mm Cd, inferior colliculus slices were incubated in oxygenated ACSF containing 0.4 mg/ml collegenase A1 (Sigma, St. Louis, MO) for 1 hr and then in 10 mg/ml papain (Sigma) at room temperature for 30 min. The slices were washed with ACSF and maintained in ACSF bubbled continuously with 95% O2 and 5% CO2 until used. Each of these slices was transferred to extracellular solution containing (in mm): 150 NaCl, 5 KCl, 1 MgCl2, 2 CaCl2, 10 mm glucose, 10 HEPES, pH 7.4, in a 35 mm dish (Corning, Corning, NY), mechanically separated using a pair of microelectrodes, and then triturated through glass pipettes.

Electrophysiological recordings. Whole-cell patch-clamp recordings were made at room temperature (20–24°C) from acutely isolated inferior colliculus neurons in the extracellular solution (as specified above), using an Axopatch-1D amplifier. The patch pipettes were pulled from thin-walled borosilicate glass (WPI, Gaithersburg, MD) with a resistance of 4–10 MΩ when filled with intracellular solution. The intracellular solution contained (in mm): 70 KCl, 70 potassium gluconate, 1 CaCl2, 11 EGTA, 10 HEPES, 5 MgCl2, 2.5 Mg-ATP, pH 7.4. After breakthrough into the whole-cell mode, the resting membrane potential was measured. To determine whether the cell was a neuron, the response to test pulses delivered between −20 and 30 pA in current-clamp mode were recorded. Only the cells that fired action potentials were used for the voltage-clamp recordings. Series resistances (11.4 ± 0.8 MΩ; mean ± SEM, n = 28) were compensated to 80%. Cell capacitance (19.4 ± 0.8 pF) was measured from the transient currents produced by a 10 mV voltage step and directly from the amplifier after compensation for series resistance. The cells were then voltage-clamped at −70 mV, and test pulses were delivered from −80 to 60 mV, with a 1 sec prepulse to −100 or −30 mV. Leak currents were monitored throughout the experiment, but not subtracted, unless stated otherwise. Current density was calculated by dividing the current amplitude by the cell capacitance. All data are presented as the mean ± SEM.

Computer modeling. Modeling of the inferior colliculus neurons was performed using methods described previously for other cells (Kanemasa et al., 1995; Perney and Kaczmarek, 1997; Wang et al., 1998). The voltage-dependence and kinetic parameters of the high-threshold Kv3.1-like currents were simulated exactly as described in detail by Wang et al. (1998) for Kv3.1 current recorded in transfected Chinese hamster ovary (CHO) cells. Conductances (gK) were adjusted to match current levels recorded in the present experiments [gK = 0.019 μS (see Fig.11B); gK = 0.01 μS (see Fig.11C); gK = 0.022 μS (see Fig.11D)]. The low-threshold potassium currentIlt and voltage-dependent inward currentsIin were simulated by the equationsIlt =glt(EK −V) and Iin =ginm3h (50 −V).

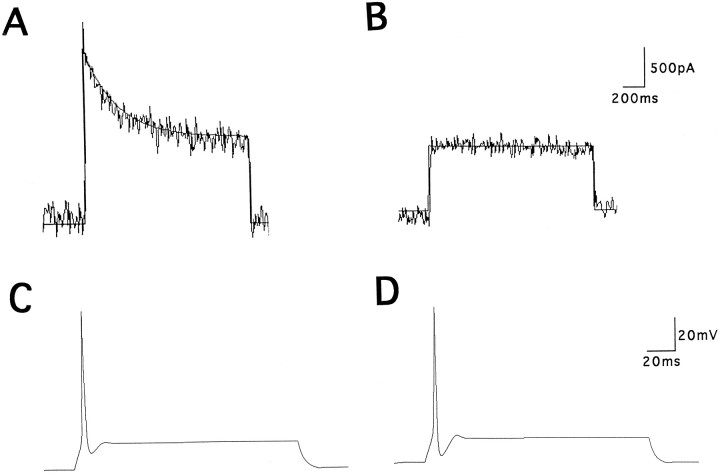

Fig. 11.

Computer simulations of the effects of a Kv3.1-like potassium conductance on action potential repolarization in inferior colliculus neurons. Inactivating (A) and noninactivating (B) potassium currents of the model cells were fit closely to the current traces shown in Figure3B,C. C, D, Action potentials were simulated in response to 20 pA current pulses in model cells with varying levels of the high-threshold noninactivating current. Thetrace in D represents a 2.2-fold increase in the conductance of the noninactivating potassium current over that in C, with no changes in other parameters. The increase in this current enhanced the AHP.

The evolution of the variables q, l,m, and h was determined by Hodgin-Huxley-like equations as described in full by Perney and Kaczmarek (1997). Activation parameters for the low-threshold potassium currents werekαl = 1.2 msec−1,ηαl = 0.03512 mV-1,kβl = 1.2 msec−1, and ηβl = −0.03188 mV-1. Inactivation parameters for the low-threshold current werekαq = 0.001 msec−1,ηαq = −0.00543 mV-1,kβq = 0.00175 msec−1, and ηβq = 0.00956 mV-1. Corresponding parameters for inward current were kαm = 76.4 msec−1, ηαm = 0.037 mV-1, kβm = 0.0027 msec−1, ηβm = −0.003 mV-1, kαh = 0.000593 μsec−1, ηαh = −0.227 mV-1, kβh= 1.065 msec−1, and ηβh= 0.013 mV-1. Numerical simulations of the responses of cells to external stimulation were performed using the equationC dV/dt = IK +Ilt + Iin +gL(EL −V) + Iext(t), wheregL represents a leakage conductance and where external currents Iext(t) were presented as step currents. For all simulations EL= −60 mV, C = 0.005 nF, and gL= 0.005 μS.

RESULTS

Changes in the levels of Kv3.1a and Kv3.1b mRNA during development

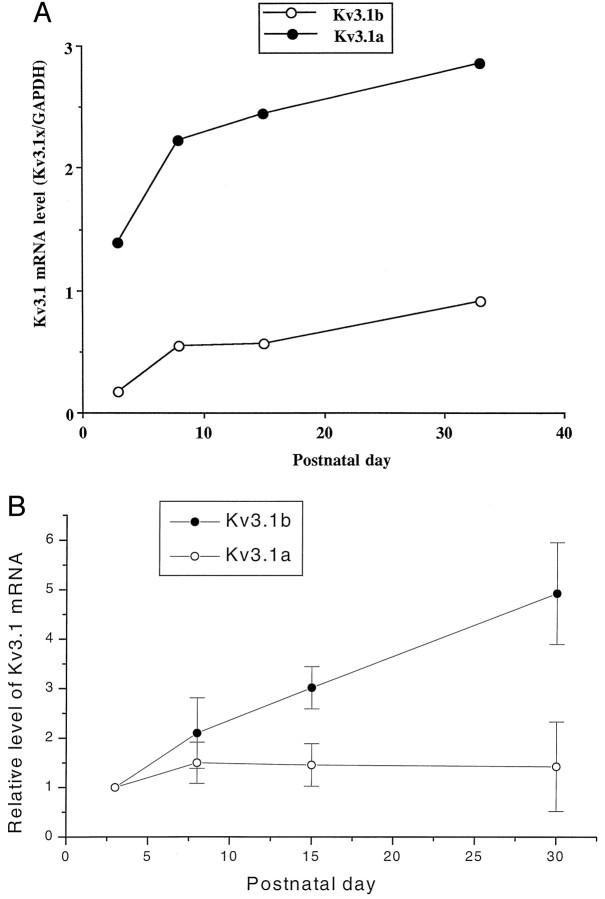

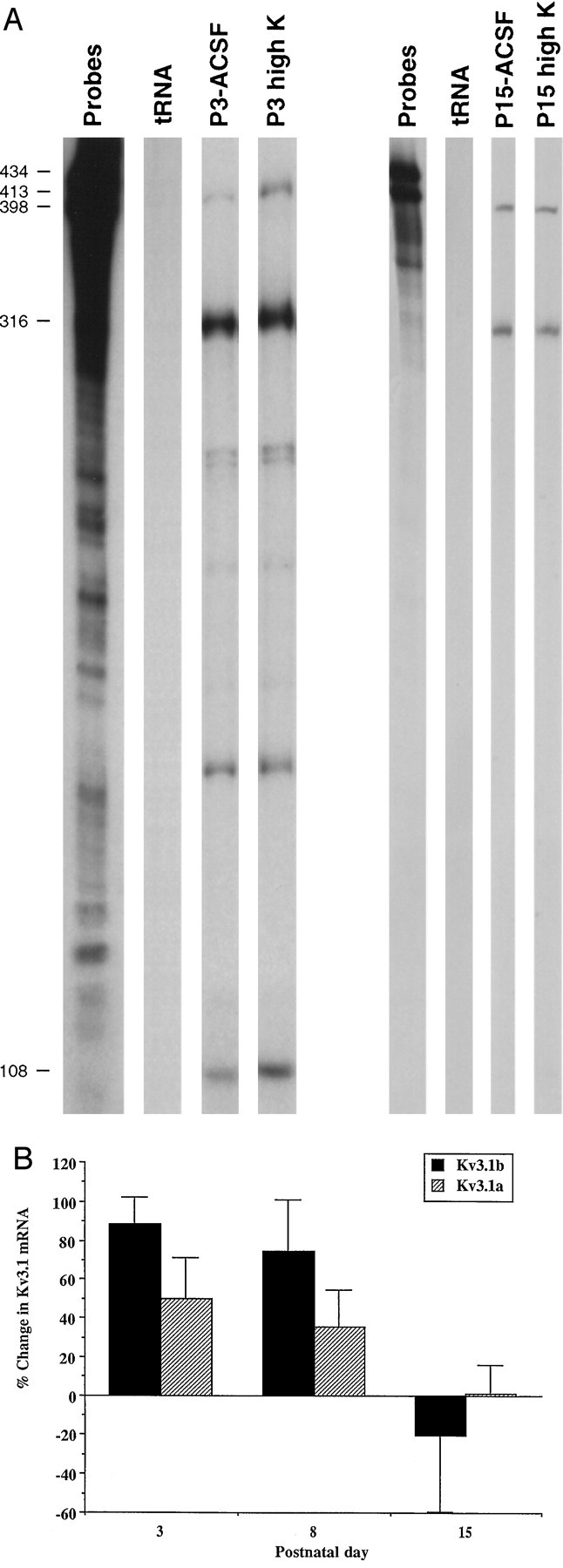

We measured the levels of Kv3.1a and Kv3.1b mRNA in the inferior colliculus at P3, P8, P15, and P33 using an RNase protection assay. The expression levels of both Kv3.1a and Kv3.1b mRNA increase during development (Fig. 1). Kv3.1a mRNA was the dominant transcript throughout development. The levels of Kv3.1a mRNA were approximately eightfold and threefold higher than the levels of Kv3.1b mRNA at P3 and P33, respectively (Fig. 1A). A pronounced increase in the expression levels of Kv3.1 transcripts occurred between P3 and P8. Relative to the levels of Kv3.1 transcripts at P3, there was a 2.1-fold increase in Kv3.1b and a 1.4-fold increase in Kv3.1a at P8 (Fig. 1B). In contrast, there was relatively little change in the levels of the Kv3.1a and Kv3.1b transcripts after P8.

Fig. 1.

Expression levels of Kv3.1a and Kv3.1b mRNA during development. A, The intensities of the Kv3.1a band determined by densitometric measurements were multiplied by 3.6 to account for the differences in the number of labeled C residues in the protected bands of Kv3.1a and Kv3.1b, as described previously (Perney et al., 1992). The levels of the Kv3.1a and Kv3.1b mRNA are normalized by the total amount of GAPDH mRNA. Each point is the mean of two measurements from one experiment. B, Normalized expression levels of Kv3.1a and Kv3.1b mRNA. The Kv3.1a and Kv3.1b mRNA levels determined from the average of two or three measurements for each RNA preparation at each developmental stage were divided by the mean values for these mRNAs at P3 determined in the same experiment. Data are mean ± SEM. n values (numbers of independent RNA preparations) at P3, P8, P18, and P30 are 3, 3, 2, and 2, respectively. The changes in the Kv3.1b mRNA levels are significantly different by ANOVA testing among these age groups, withp < 0.01. A Tukey–Kramer multiple-comparisons test showed that the change in the Kv3.1b mRNA expression at P30 was significantly different from that at P3 and P8, with p < 0.01 and 0.05, respectively.

Regulation of Kv3.1 transcripts by depolarization

To investigate the possible role of neuronal activity in the developmental regulation of Kv3.1 mRNA levels, we examined the effects of depolarization on the expression of Kv3.1a and Kv3.1b mRNAs during development, using an in vitro slice preparation. We first tested the viability of inferior colliculus slices in ACSF by measuring the uptake of 2-deoxyglucose and found that inferior colliculus slices remained viable in ACSF for at least 6 hr at all ages tested (Table1). We also examined whether in vitro incubation by itself altered the levels of Kv3.1 expression and found that the ratio of mRNA levels after incubation in ACSF for 6 hr to that of control was 1.00 ± 0.09 (n = 18) for Kv3.1a and 1.08 ± 0.07 (n = 26) for Kv3.1b. Thus, incubation in ACSF for 6 hr did not change the levels of Kv3.1a and Kv3.1b mRNA.

In the following experiments, inferior colliculus slices from animals at P3, P8, and P15 were incubated in ACSF or in high-K ACSF for 6 hr at room temperature. The levels of Kv3.1a and Kv3.1b mRNA were subsequently determined using an RNase protection assay. Depolarization with high-K ACSF induced a marked increase in the levels of Kv3.1b transcripts at P3 and P8 (Fig.2A,B). Interestingly the depolarization did not affect the expression levels of Kv3.1 transcripts at P15, a developmental period when there was relatively little change in the levels of Kv3.1. Thus the depolarization-induced increase in Kv3.1 mRNA levels appears to correlate temporally with the changes in the levels of Kv3.1 transcripts during development.

Fig. 2.

We also examined whether the neurotrophins BDNF and NT-3 and the growth factors FGF and NGF affected the expression of Kv3.1 transcripts in the inferior colliculus slices at P3, P8, P15, and P30–40. Treatment with these factors in ACSF for 6 hr did not significantly alter the levels of Kv3.1a and Kv3.1b mRNA (data not shown).

Isolation of a Kv3.1-like potassium current in inferior colliculus neurons

Inferior colliculus neurons are known to express several potassium channels, including Kv3.1 (Beckh and Pongs, 1990; Perney et al., 1992; Weiser et al., 1994). To investigate the possible effects of depolarization on currents conducted by the Kv3.1 channel in inferior colliculus neurons, we isolated a potassium current that has the characteristics of the Kv3.1 channel, i.e., a high-threshold, noninactivating current that is sensitive to TEA (Yokoyama et al., 1989; Luneau et al., 1991; Kanemasa et al., 1995).

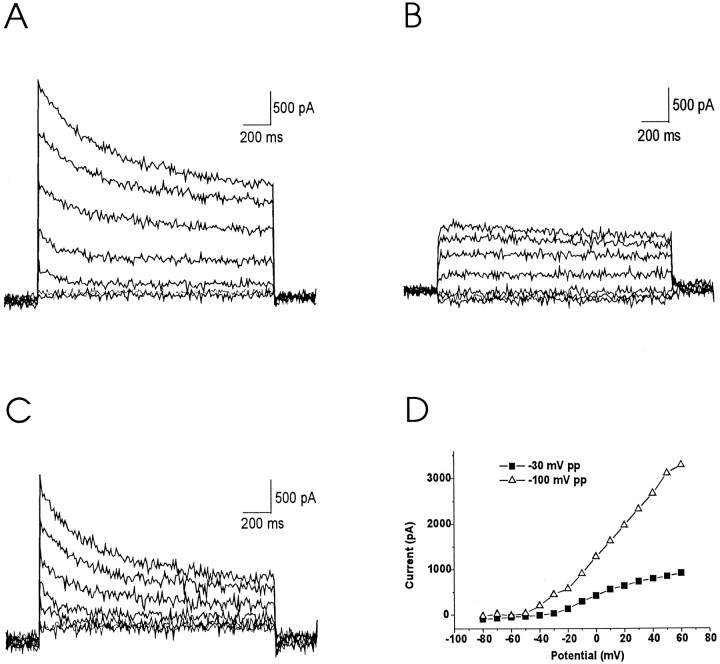

Acutely dissociated neurons from inferior colliculus were voltage-clamped and held at −70 mV. A family of total outward currents (Ipp-100) evoked by a series of voltage steps to potentials between −80 and 60 mV, after a 1 sec prepulse to −100 mV, is illustrated in Figure3A. Voltage-dependent outward currents were activated at potentials to −40 mV (Fig. 3D) and contained an inactivating component and a noninactivating component. In contrast, after a prepulse to −30 mV for 1 sec, outward currents (Ipp-30) were activated only at potentials positive to −20 mV in these cells (Fig. 3D). The latter currents did not undergo inactivation during depolarization lasting 1600 msec (Fig. 3B). Thus, a transient outward current with a low activation threshold could be eliminated by the 1 sec prepulse to −30 mV. Subtracting the noninactivating current after the −30 mV prepulse from the total current gave rise to a family of currents that represent this transient component (Fig.3C).

Fig. 3.

Different components of the outward current in voltage-clamped inferior colliculus neurons. Cells were held at −70 mV and stepped to a prepulse potential of −100 mV (A) or −30 mV for 1 sec (B), before the voltage was stepped to potentials between −80 and 60 mV (D), or between −70 and 50 mV (A, B) in 20 mV increments. A, Total current after a 1 sec prepulse to −100 mV. B, Outward current after a 1 sec prepulse to −30 mV. C, The difference current obtained by subtracting current inB from the current in A.D, Voltage dependence of the peak amplitude of total currents after a prepulse to −100 mm (▵) and of the steady-state current after a prepulse to −30 mm(▪).

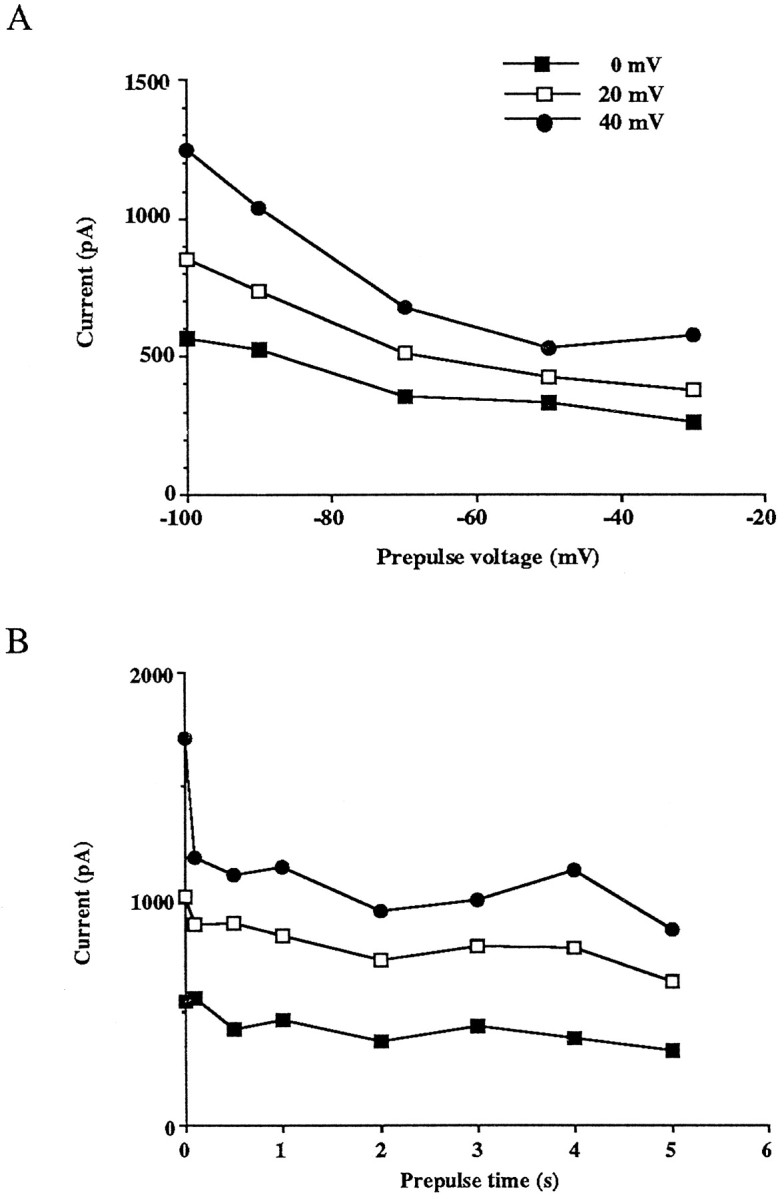

We varied the voltage of the prepulse from −100 to −30 mV (Fig.4A). The peak current amplitude decreased as the potential of the prepulse was made more positive and appeared to level off at approximately −50 mV. We also changed the duration of the prepulse at −30 mV and found that a prepulse of 0.5 sec was sufficient to suppress most of the inactivating current (Fig. 4B). A longer prepulse did not further reduce the current amplitude. We therefore used 1 sec prepulses to −30 and −100 mV in our experiments to measure the noninactivating current and the total currents, respectively. These prepulses did not alter the kinetics and amplitude of Kv3.1 currents in CHO cells transfected with the Kv3.1 gene (data not shown).

Fig. 4.

Effects of prepulse potential and prepulse duration on the peak current amplitude at 0, 20, and 40 mV.A, Measurements of peak current amplitude after prepulse potentials between −100 and −30 mV for 1 sec. B, Measurements of current amplitude after a prepulse to −30 mV for duration between 0 and 5 sec.

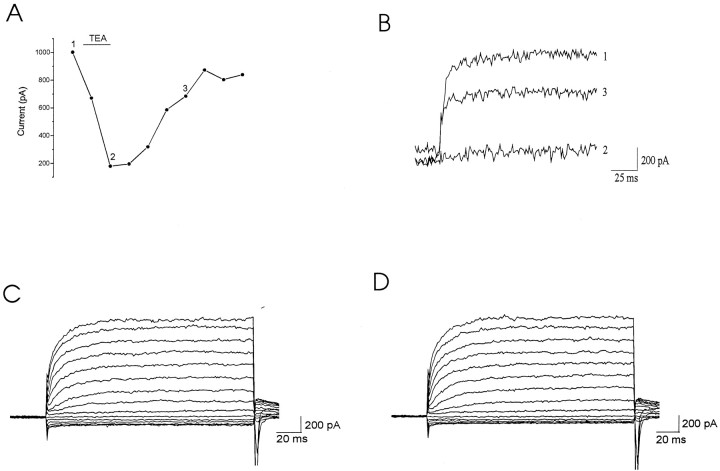

The current generated by the Kv3.1 channel subunit, when expressed in cell lines, is strongly inhibited by 1–2 mm TEA (Kanemasa et al., 1995). We therefore examined the effects of 2 mmTEA on the currents evoked after a −30 mV prepulse and found that TEA reversibly eliminated these currents (Fig.5A,B) (n = 3). This current was also inhibited by 100 μm 4-AP (n = 2; data not shown). The characteristics of these high-threshold currents therefore generally resemble those of Kv3.1 in their high activation threshold, lack of inactivation, and sensitivity to TEA and 4-AP.

Fig. 5.

TEA inhibits the high-threshold current, whereas Cd2+ does not affect this current. Currents of acutely dissociated inferior colliculus neurons were recorded in response to voltage steps from −80 to +60 mV in 20 mV increments after a prepulse to −30 mV for 1 sec. An extracellular solution containing 2 mm TEA (A, B) or 0.5 mmCd2+ (D) was perfused into the recording dish, and cells were then washed with extracellular solution.A, Bath application of 2 mm TEA inhibited the high-threshold current. The inhibition was reversed by perfusing extracellular solution without TEA. The last three data points were measured in the presence of 1 μm TTX. B, Current traces before TEA (1), in the presence of 2 mm TEA (2), and after washing (3). The currents were leak-subtracted and filtered at 500 Hz. C, D, Current traces of an inferior colliculus neuron before (C) and during (D) application of 0.5 mmCd2+.

Because we identified neurons among all dissociated cells in a dish by their ability to fire action potentials in response to injection of depolarizing currents, we did not include TTX in the extracellular solution in most of the experiments. In several experiments, however, we superperfused extracellular solution containing 1 μmTTX into the bath solution to determine whether the sodium current alters the amplitude of the steady-state current after the −30 mV prepulse. TTX did not change the amplitude of the high-threshold steady-state outward current (data not shown; n = 3). We also tested whether calcium current or calcium-activated potassium current contributes to the high-threshold, noninactivating currents by measuring the total current before and after the superperfusion of extracellular solution containing 0.5 mmCd2+. Cd2+ did not alter the amplitude of this current (Fig. 5C,D) (n = 3).

Depolarization increases the current density of the high-threshold, noninactivating current

We next examined whether the increase in the Kv3.1 mRNA induced by depolarization results in an increase in the current density of the high-threshold, noninactivating current in inferior colliculus neurons. Inferior colliculus slices obtained from P3–P6 rats were incubated in high-K ACSF or in ACSF for 6 hr, and then treated with collagenase and papain in ACSF. Cells were then mechanically dissociated from the slices in extracellular solution. First, the properties of the cells were determined in the current-clamp mode to distinguish neurons from glia. For each neuron, we measured the capacitance of the cell, resting membrane potential, and input resistance. The resting membrane potentials of high-K-treated cells (mean ± SEM = −63 ± 4 mV, n = 9; values ranged from −50 to −80 mV) were not significantly different from those of control cells (−59 ± 3 mV, n = 17; ranging from −30 to −74 mV). The input resistance of high-K-treated cells was 323 ± 72 MΩ(n = 11) and that of control cells was 320 ± 46 MΩ (n = 17).

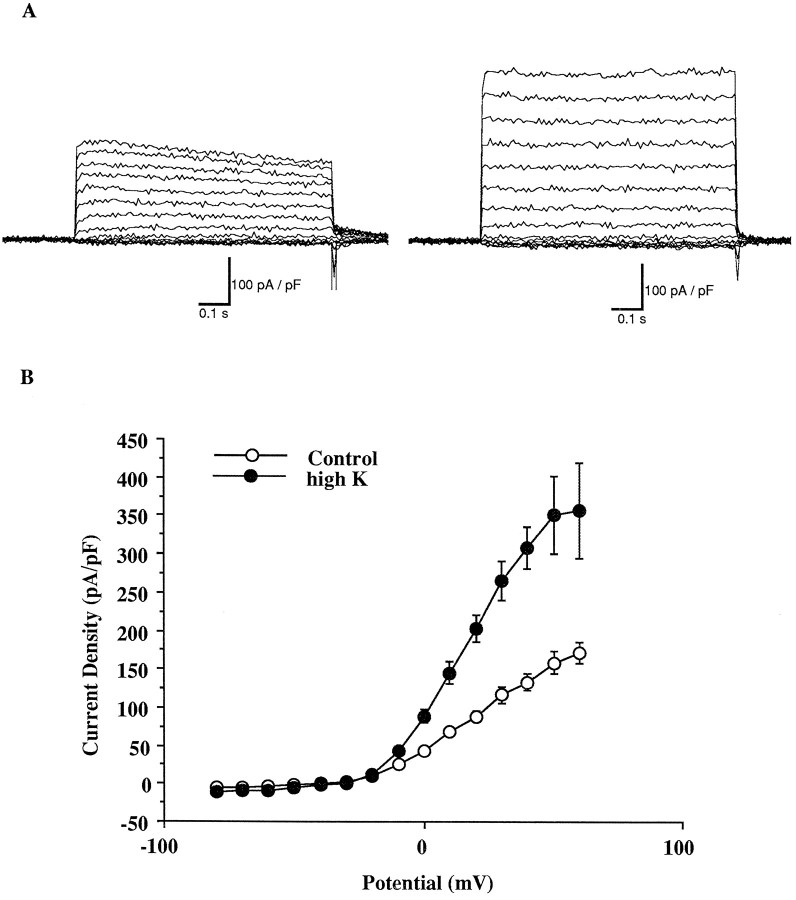

We then measured the outward currents in these inferior colliculus neurons in response to voltage steps between −80 and 60 mV after a 1 sec prepulse to −30 mV. Current traces from a control inferior colliculus neuron at P5 and those from a high-K-treated P5 neuron are shown in Figure 6A. An averaged value of current density is plotted against command potential in Figure 6B. In both control and high-K-treated cells, currents were activated at potentials positive to −20 mV and showed no inactivation. However, the high-K-treated cells had a 2.2-fold higher current density than that of controls. The changes in current density produced by previous depolarization appear to quantitatively agree with the changes in the Kv3.1 mRNA levels (Fig.2B).

Fig. 6.

High-K depolarization induces an increase in the current density of the high-threshold current. A, Typical examples of high-threshold current recorded from control cells (left) and high-K-treated cells (right).B, Current density versus voltage curves were generated for both control (n = 19) and high-K-treated cells (n = 10). Data points are mean ± SEM. The current density in high-K-treated cells is significantly different from that of control at −10 mV (p < 0.01) and from 0–60 mV (p < 0.001) (two-tailed Student’s t test).

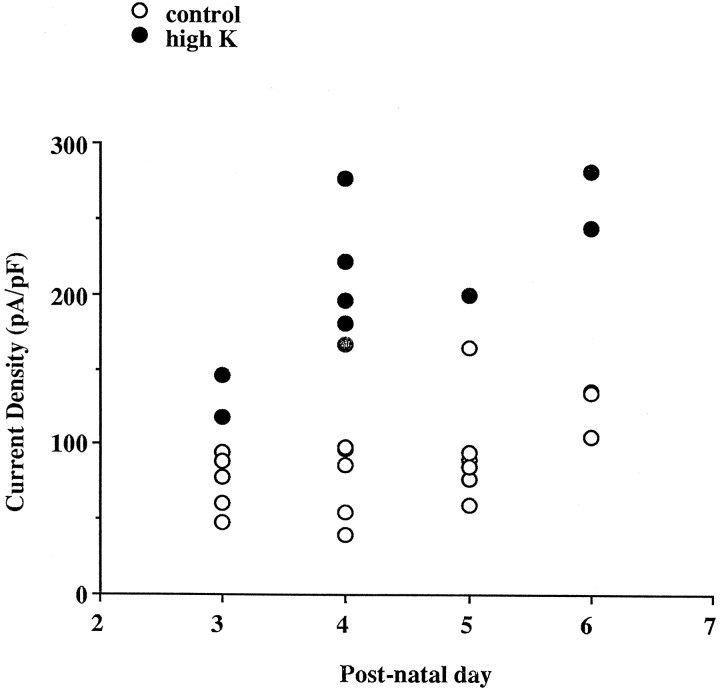

Because the levels of Kv3.1 mRNA increased between P3 and P8, we examined whether the density of this high-threshold, noninactivating current also increases over this period in the dissociated inferior colliculus neuron. The amplitude of the current density at 20 mV increased from 74 ± 9 pA/pF (n = 5) at P3 to 125 ± 10 pA/pF (n = 3) at P6 in the control cells (p < 0.01) (Fig.7). This increase appeared to be consistent with the increase in the levels of Kv3.1 mRNA during this developmental period (Fig. 1). The high-K-treated cells consistently had a higher current density than that of control cells of the same age (Fig. 7). This correlates with our observation that depolarization increases the levels of Kv3.1 mRNA at both P3 and P8.

Fig. 7.

Developmental changes in current density of the high-threshold current at +20 mV after a prepulse to −30 mV for 1 sec in control (○) and high-K-treated (•) inferior colliculus neurons. The current density in control cells increases during development. High-K treatment induced an increase in the current density at each of the early postnatal days examined.

Ca2+ influx mediates the increase in the amplitude of high-threshold currents

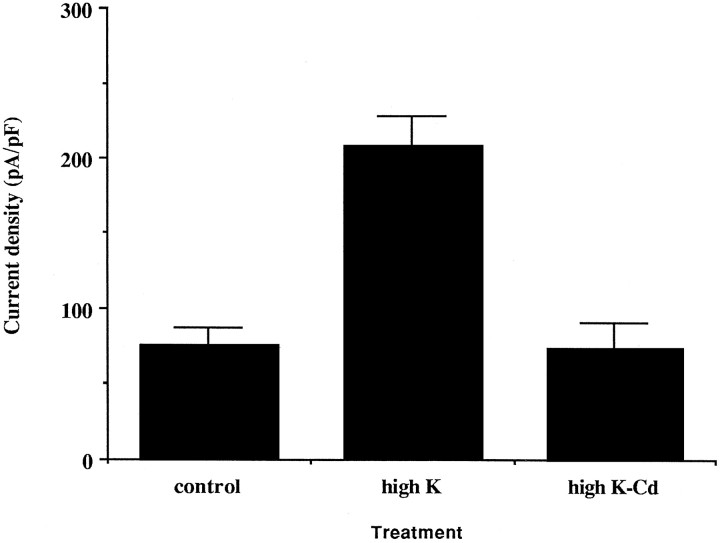

An increase in intracellular calcium concentration of immature neurons plays an important role in the maturation of neuronal connectivity and in developmental changes in the expression of ion channels (Gu and Spitzer, 1995; Wong et al., 1995). We therefore tested whether the high-K ACSF-induced increase in high-threshold current amplitude in the immature inferior colliculus neurons requires Ca2+ influx by blocking voltage-gated calcium currents with Cd2+. P4 inferior colliculus slices were incubated in high-K ACSF or in high-K ACSF containing 1 mm Cd2+ for 6 hr. Neurons were dissociated from the slices after these treatments. The current density after a prepulse to −30 mV in the neurons incubated in high-K ACSF containing Cd2+ remained at the control level (Fig.8). Thus this Ca2+channel inhibitor blocked the depolarization-induced increase in amplitude of the high-threshold current, suggesting that the increase in current is mediated by calcium influx during the depolarization. Because in the AtT20 cell line blocking L-type calcium channels prevented the high-K-induced upregulation of Kv3.1 mRNA expression (T. M. Perney and L. K. Kaczmarek, unpublished data), we incubated the inferior colliculus slices in high-K ACSF in the presence of 100 μm nifedipine, a blocker of L-type channel. Nifedipine completely blocked the depolarization-induced increase in current density of the high-threshold current (the current density at +20 mV was 16.0 ± 0.6 pA/pF; n = 4), suggesting that the major source of calcium influx is through L-type channel.

Fig. 8.

The depolarization-induced increase in high-threshold current density requires calcium influx. Inferior colliculus slices from P4 rats were incubated in high-K, in high-K ACSF containing 1 mm Cd, or in ACSF for 6 hr at room temperature. The neurons were then acutely dissociated from the inferior colliculus slices. After a 1 sec prepulse to −30 mV, evoked currents were measured at +20 mV. Data are mean ± SEM. The current density of the high-K-treated sample (n = 5) is significantly different from that of control (n = 5) (p < 0.001) and from that of the high-K ACSF Cd2+ samples (n = 3) (p < 0.01), by a two-tailed Student’s t test.

Effects of depolarization on the inactivating current

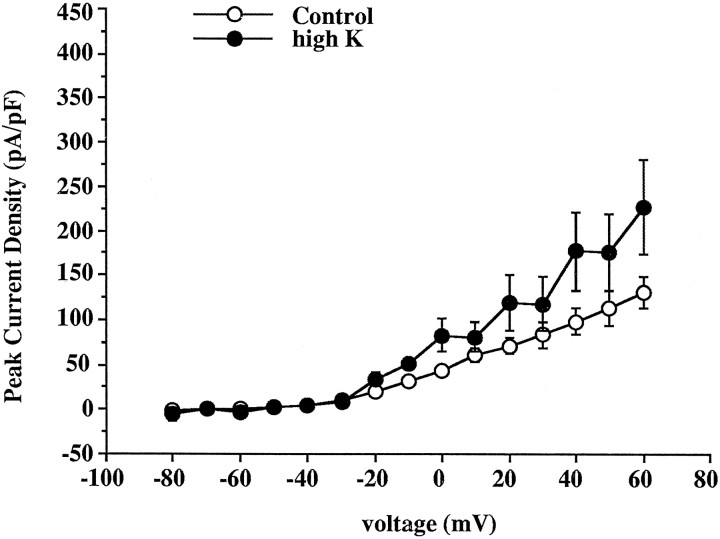

As described above, the outward currents in inferior colliculus neurons consist of inactivating currents and noninactivating currents, and these components can be separated by applying prepulses to −30 and −100 mV (Fig. 3). We therefore tested whether the depolarization specifically increases the current density of the high-threshold, noninactivating current or whether it also affects the inactivating currents. Currents were measured after a prepulse to −100 mV, and the noninactivating current evoked after a prepulse to −30 mV was subtracted from this current. The difference current activated between −40 and −20 mV (Figs. 3C,9). The averaged current density for the peak of this difference current was smaller than that of the noninactivating current (Figs. 6B, 9). Treatment with elevated potassium caused only a moderate increase (47%) in the peak value of the difference current. Thus depolarization appears preferentially to upregulate the expression of noninactivating current in early postnatal inferior colliculus neurons.

Fig. 9.

Effects of high-K depolarization on the inactivating current obtained by subtracting the current after a 1 sec prepulse to −30 mV from the total current after a 1 sec prepulse to −100 mV. Peak current density versus voltage curves were generated for both control (n = 17) and high-K-treated cells (n = 8). Data points are mean ± SEM. The mean current density in high-K-treated cells is different from that in control cells at −20, −10, 0, 10, 40, and 60 mV (p < 0.05) by a two-tailed Student’st test.

Depolarization alters the electrophysiological properties of inferior colliculus neurons

The kinetic properties of Kv3.1 current and the high-threshold current in inferior colliculus neurons, namely high-activation threshold and lack of inactivation, indicate that these currents should facilitate rapid repolarization of action potentials. To test the hypothesis that the selective upregulation of the high-threshold current affects the electrophysiological properties of inferior colliculus neurons during maturation, we examined the firing properties of control and of high-K-treated cells in normal extracellular solution.

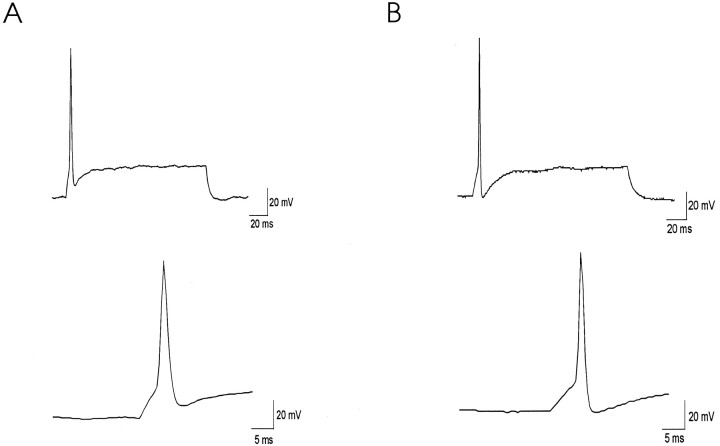

The majority of control inferior colliculus neurons (63%) and many high-K-treated cells (44%) fired only a single action potential in response to sustained depolarizing current (10–20 pA, 160 msec), whereas the remainder were capable of generating two to five spikes in response to the same stimuli (Table 2). These results are consistent with previous studies of the responses of inferior colliculus neurons in slices (Peruzzi and Oliver, 1994;Wisgirda et al., 1996). Repolarization of the action potentials during the current pulse was associated with an afterhyperpolarization (AHP), after which the membrane potential decayed passively toward its steady-state value (Fig. 10). We measured three parameters of action potential repolarization: (1) the amplitude of the first action potential, (2) the latency from the peak of the action potential to the peak of the subsequent AHP, and (3) the difference in membrane potential between the peak AHP and the resting potential. The amplitude of the first action potential in control cells was not different from that in high-K-treated cells. The duration of the decay phase of the action potentials, however, was significantly reduced in the high-K-treated cells (Table 2, Fig. 10). Moreover, the degree of repolarization was significantly enhanced in the high-K-treated cells, as measured by the differences between the AHP and resting potential. These data indicate that repolarization in high-K-treated cells is more rapid and complete than in the control cells.

Table 2.

Effects of depolarization on electrophysiological properties of inferior colliculus neurons

| AP amplitude (mV) | AHP–RMP (mV) | AP decay duration (msec) | Number of AP | Number of cells firing | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Multiple APs | Single AP | |||||

| Control | 104 ± 9 | 16 ± 22-a | 4.4 ± 0.32-a | 2.4 ± 0.6 | 6 | 10 |

| High-K treated | 111 ± 6 | 8 ± 32-a | 3.3 ± 0.32-a | 3.9 ± 1.4 | 5 | 4 |

The action potential amplitude, difference between the afterhyperpolarization potential and resting membrane potential, action potential decay duration, and number of action potentials were determined from the action potentials evoked by a 10 pA (or 20 pA in two control cells) depolarizing current step for 160 msec. The action potential decay duration is defined as the time from the peak of the action potential to the maximal hyperpolarization. In total, 16 control cells and 9 high-K-treated cells were examined.

The control values are different from that determined in high-K-treated cells; p < 0.05 (two-tailed Student’s t test).

Fig. 10.

Representative whole-cell voltage recordings from a control neuron (A) and from a high-K-treated neuron (B), isolated from P5 inferior colliculus. Action potentials were evoked by a 160 msec depolarizing current pulse of 10 pA. The rate of repolarization of action potential was 30.6 mV/msec in the control cell and 44.7 mV/msec in the high-K-treated cell. The difference between AHP and resting potential was 8.83 mV in the control and −0.5 mV in the high-K-treated cell.

To determine whether the increase in high-threshold current alone can account for the change in the action potential repolarization, we performed computer simulations of the isolated inferior colliculus neurons. We simulated a cell that has voltage-sensitive inward current, a leak conductance, and two components of K current: an inactivating conductance and a high-threshold noninactivating conductance. The activation and deactivation parameters of the noninactivating current matched those of Kv3.1 current recorded in CHO cells (Wang et al., 1998), and its conductance was adjusted to levels of current recorded in the inferior colliculus neurons (Fig.11B). The inactivating current was fitted to an A-type current model, and its conductance and kinetic parameters were adjusted to fit closely to the recorded difference currents (Fig. 11A). Inward current parameters were adjusted to give action potentials that matched those recorded in these experiments. Simulated action potentials were triggered by a 160 msec suprathreshold current pulse (Fig.11C). As the conductance of noninactivating K current was increased by 2.2-fold, the repolarization of the simulated action potentials and the magnitude of the AHP were enhanced in a manner that closely resembled voltage traces recorded from the high-K-treated inferior colliculus neurons (Fig. 10A,B). Thus an increase in the density of a Kv3.1-like current alone, by the same amount that occurs in response to depolarization by elevated potassium concentrations, can produce the more rapid and complete repolarization of action potentials measured in these experiments.

DISCUSSION

The expression of potassium channels changes throughout development and plays an important role in determining the excitability of neurons (Ribera and Spitzer, 1992). In the present study we found a marked increase in the levels of Kv3.1 mRNA in the inferior colliculus neurons from P3 to P8. We also identified a noninactivating high-threshold, TEA-sensitive potassium current in the neurons acutely isolated from the P3–P6 inferior colliculus. This current has all the characteristics expected of a Kv3.1-type current and undergoes a 1.7-fold increase in amplitude from P3 to P6. This is comparable to the increase in the levels of Kv3.1 mRNA in the developing inferior colliculus neurons over the same time period.

Increases in the levels of Kv3.1a and Kv3.1b mRNA and Kv3.1b protein during development have also been found in cerebellum (Liu and Kaczmarek, 1998) and in hippocampal interneurons (Du et al., 1996). However, the temporal expression pattern of these splice variants in inferior colliculus cells differs from that in cerebellum. The Kv3.1a transcript predominates in early postnatal days in cerebellum, whereas the levels of Kv3.1b mRNA increase and exceed those of Kv3.1a mRNA during subsequent development. In contrast, Kv3.1a appears to be the dominant transcript in inferior colliculus throughout development. This difference in the temporal expression pattern of splice variants suggests that there exists cell type-specific regulation of the expression of the Kv3.1 potassium channel.

Upregulation of Kv3.1 expression by depolarization

Our observation that treatment with high-K ACSF induces an increase in the expression of Kv3.1 in developing inferior colliculus neurons is consistent with the earlier observation that depolarization increases Kv3.1 mRNA levels in AtT20 cells (Perney and Kaczmarek, 1993). Depolarization has also been shown to alter the expression of a Ca2+-activated potassium channel gene in cerebellum (Muller et al., 1998) and the Kv1.5 potassium channel in pituitary cells (Levitan et al., 1995) via calcium-dependent and calcium-independent pathways, respectively. In the present experiments, we found that blocking Ca2+ channels with Cd2+ prevented the depolarization-induced increase in amplitude of a high-threshold Kv3.1-like current. Thus the effect of depolarization is likely to be mediated by an increase in Ca2+ influx. Because elevated potassium concentrations have been shown to enhance the activity of the Kv3.1 promoter, depolarization may elevate the levels of Kv3.1 expression in developing inferior colliculus neurons by increasing Kv3.1 promoter activity (Gan et al., 1996).

Effects of depolarization with high-K ACSF on the expression of Kv3.1 appears to depend on the cell type as well as its stage of development. In cerebellum at P8, depolarization alone does not affect the expression of Kv3.1, but selectively suppresses the FGF-induced upregulation of Kv3.1a mRNA by inhibiting PKC activation (Liu and Kaczmarek, 1998). Thus, different cellular mechanisms appear to regulate the expression of Kv3.1 mRNA in different cell types.

Functional role of the high-threshold current in developing inferior colliculus neurons

In the present study, we used prepulses of −100 and −30 mV to separate a noninactivating, high-threshold, and TEA-sensitive current from other inactivating currents. A similar method has been used to isolate currents that have all the characteristics of Kv3.1-type current in neurons of the medial nucleus of the trapezoid body and in cortical neurons (Brew and Forsythe, 1995; Massengill et al., 1997;Wang et al., 1998) in which Kv3.1 mRNA and protein are present (Perney et al., 1992; Weiser et al., 1994). In addition to the Kv3.1 channel, mRNA for another Shaw-subfamily potassium channel, Kv3.3, is present in inferior colliculus neurons (Weiss et al., 1994). Kv3.3 current, like Kv3.1, activates at potentials positive to −20 mV and is sensitive to TEA and 4-AP. These two channels differ, however, in their inactivation kinetics. The Kv3.3 gene, when expressed alone in oocytes, produces current that inactivates substantially in 100 msec, whereas Kv3.1 expresses a noninactivating, delayed rectifier-type current. Coassembly of Kv3.1 and Kv3.3 subunits is likely to produce a current with intermediate inactivation kinetics, as has been shown for co-expression of the Kv3.1 and Kv3.4 genes (Weiser et al., 1994). In our experiments, however, the currents measured after a −30 mV prepulse exhibited no inactivation, and therefore most closely resemble the characteristics of Kv3.1 expressed alone. Calcium currents, which could activate calcium-dependent potassium currents during depolarization, have been characterized in inferior colliculus neurons and appear to be of the L and N type (N’Gouemo and Rittenhouse, 1997). Because the presence of Cd2+, which blocks these channels, did not alter the amplitude of the steady-state outward current after a −30 mV prepulse, the activation of calcium-dependent potassium currents appears to be very small under our experimental conditions.

We have shown that depolarization induces an increase in the high-threshold, noninactivating currents and that this increase in current density parallels an increase in Kv3.1 mRNA levels. In contrast, depolarization caused only a moderate increase in the inactivating component of potassium currents. Computer simulation studies have demonstrated that an increase in Kv3.1-like current allows cells to follow high rates of synaptic stimulation (Kanemasa et al., 1995; Perney and Kaczmarek, 1997; Wang et al., 1998). Consistent with this, higher levels of Kv3.1 mRNA and Kv3.1-like current have been found in fast-spiking cortical neurons than in regular-spiking cortical neurons (Massengill et al., 1997), and elimination of Kv3.1-like currents prevents auditory neurons in the medial nucleus of the trapezoid body from following high-frequency stimuli (Wang et al., 1998). In inferior colliculus neurons, we have shown that the repolarization of action potentials in the high-K-treated cells was more rapid and complete than in the control cells. Although this produces only a minor change in the response of the isolated cells to a sustained depolarizing current, enhanced repolarization is likely to enhance the response of the cells to repetitive synaptic stimulation (Perney and Kaczmarek, 1997; Wang et al., 1998). Furthermore, computer simulation of action potentials in inferior colliculus neurons indicated that an increase in Kv3.1-like current by itself was sufficient to produce such changes in repolarization. Thus selective upregulation of Kv3.1 could enable these neurons to fire at high frequencies in response to synaptic stimulation, with very little changes in the amplitude of their action potentials.

Differential regulation of the expression of Kv3.1 by depolarization during development

We have demonstrated that depolarization with an elevated potassium concentration upregulates the expression of Kv3.1 in P3 and P8 neurons but not in P15 neurons of the inferior colliculus. This suggests that depolarization affects expression only at early developmental stages, before the onset of hearing (P12–P14) (Kelly, 1992). Interestingly, spontaneous neuronal activities are present in many immature neurons and neural networks and contribute to the refinement of neuronal connections within the visual system before the onset of vision (Wong et al., 1995; Shatz, 1996). Spontaneous activity has been recorded in the nucleus magnocellularis and in the nucleus laminaris of the developing chick auditory system (Lippe, 1994) and in immature mammalian auditory neurons, including inferior colliculus neurons (Kotak and Sanes, 1995). Although the average rates of neuronal discharge in mammalian auditory neurons appear to be low during development, low-frequency stimulation of an excitatory pathway from the cochlear nucleus induces a long-lasting depolarization (up to 34 min) of neurons in the lateral superior olive of early postnatal gerbils before the onset of hearing (Kotak and Sanes, 1995). Such a prolonged depolarization may increase Ca2+ influx and could regulate the transcription of ion channels and other proteins (Spitzer, 1991; Gu and Spitzer, 1995). In our experiments, incubation of inferior colliculus slices in high-K ACSF may exert effects similar to those of spontaneous synaptic activity, which before the onset of hearing may provide signals required for the maturation of intrinsic membrane properties. Our findings suggest, therefore, that Ca2+ influx plays a role in the maturation of potassium channel expression in auditory neurons before the onset of hearing.

The failure of depolarization with a raised external potassium concentration to enhance expression of Kv3.1 in P15 neurons could reflect developmental changes in intracellular signaling pathways. For example, depolarization inhibits PKC activity in P8 cerebellum but enhances PKC activity in the adult (Liu and Kaczmarek, 1998). Alternatively, developmental changes in ion channels (O’Dowd et al., 1988; Ribera and Spitzer, 1989) could alter calcium dynamics in response to depolarization. Moreover, depolarization may cause release of neurotransmitters (Smith, 1992), and the effects of elevated potassium ions could be mediated by substances released during depolarization.

Footnotes

This work was supported by Grant DC-01919 from National Institutes of Health (L.K.K.) and a National Research Service Award fellowship (S.J.L.). We thank Drs. Neil Magoski, Lu-yang Wang, Matthew Whim, and Mary Wisgirda for helpful discussions and technical advice.

Correspondence should be addressed to Dr. Leonard K. Kaczmarek, Department of Pharmacology, Yale University School of Medicine, 333 Cedar Street, New Haven, CT 06520-8066.

REFERENCES

- 1.Ausubel FM, Brent R, Kingston RE, Moore DD, Seidmand JG, Smith JA, Struhl K. Current protocols in molecular biology, pp 4.7.1–4.8.3. Wiley; New York: 1990. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Beckh S, Pongs O. Members of the RCK potassium channel family are differentially expressed in the rat nervous system. EMBO J. 1990;9:777–782. doi: 10.1002/j.1460-2075.1990.tb08173.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Brew HM, Forsythe ID. Two voltage-dependent K+ conductances with complementary functions in postsynaptic integration at a central auditory synapse. J Neurosci. 1995;15:8011–8022. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.15-12-08011.1995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Chomcyznski P, Sacchi N. Single-step method of RNA isolation by guanidinium thiocyanate-phenol-chloroform extraction. Anal Biochem. 1987;162:156–159. doi: 10.1006/abio.1987.9999. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Du J, Zhang L, Weiser M, Rudy B, McBain C. Developmental expression and functional characterization of the potassium-channel subunit Kv3.1b in parvalbumin-containing interneurons of the rat hippocampus. J Neurosci. 1996;16:506–518. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.16-02-00506.1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Ehret G, Romand R. Development of tonotopy in the inferior colliculus II: 2-DG measurements in the kitten. Eur J Neurosci. 1994;6:1589–1595. doi: 10.1111/j.1460-9568.1994.tb00549.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Feldman DE, Brainard MS, Knudsen EI. Newly learned auditory responses mediated by NMDA receptors in the owl inferior colliculus. Science. 1996;271:525–528. doi: 10.1126/science.271.5248.525. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Gan L, Perney TM, Kaczmarek LK. Cloning and characterization of the promoter for a potassium channel expressed in high frequency firing neurons. J Biol Chem. 1996;271:5859–5865. doi: 10.1074/jbc.271.10.5859. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Gu X, Spitzer NC. Distinct aspects of neuronal differentiation encoded by frequency of spontaneous Ca2+ transients. Nature. 1995;375:784–787. doi: 10.1038/375784a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Kanemasa T, Gan L, Perney TM, Wang L-Y, Kaczmarek LK. Electrophysiological and pharmacological characterization of a mammalian Shaw channel expressed in NIH 3T3 fibroblasts. J Neurophysiol. 1995;74:207–217. doi: 10.1152/jn.1995.74.1.207. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Katz LC, Shatz CJ. Synaptic activity and the construction of cortical circuits. Science. 1996;274:1133–1138. doi: 10.1126/science.274.5290.1133. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Kelly JB. Behavioral development of the auditory orientation response. In: Romand R, editor. Development of auditory and vestibular system 2. Elsevier; Amsterdam: 1992. pp. 391–418. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Kotak VC, Sanes DH. Synaptically evoked prolonged depolarizations in the developing auditory system. J Neurophysiol. 1995;74:1611–1620. doi: 10.1152/jn.1995.74.4.1611. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Levitan ES, Gealy R, Trimmer JS, Takimoto K. Membrane depolarization inhibits Kv1.5 voltage-gated K+ channel gene transcription and protein expression in pituitary cells. J Biol Chem. 1995;270:6036–6041. doi: 10.1074/jbc.270.11.6036. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Lippe WR. Rhythmic spontaneous activity in the developing avian auditory system. J Neurosci. 1994;14:1486–1495. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.14-03-01486.1994. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Liu SJ, Kaczmarek LK. The expression of two splice variants of the Kv3.1 potassium channel gene is regulated by different signaling pathways. J Neurosci. 1998;18:2881–2890. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.18-08-02881.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Luneau CJ, Williams JB, Marshall J, Levitan ES, Oliva C, Smith JS, Antanavage J, Folander K, Stein RB, Swanson R, Kaczmarek LK, Buhrow SA. Alternative splicing contributes to K+ channel diversity in the mammalian central nervous system. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1991;88:3932–3936. doi: 10.1073/pnas.88.9.3932. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Massengill JL, Smith MA, Son DI, O’Dowd DK. Differential expression of K4-AP currents and Kv3.1 potassium channel transcripts in cortical neurons that develop distinct firing phenotypes. J Neurosci. 1997;17:3136–3147. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.17-09-03136.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Morest DK, Oliver DL. The neuronal architecture of the inferior colliculus in the cat: defining the functional anatomy of the auditory midbrain. J Comp Neurol. 1983;222:209–236. doi: 10.1002/cne.902220206. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Muller YL, Reitstetter R, Yool AJ. Regulation of Ca2+-dependent K+ channel expression in rat cerebellum during postnatal development. J Neurosci. 1998;18:16–25. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.18-01-00016.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.N’Gouemo P, Rittenhouse AR. Pharmacological characterization of voltage-sensitive calcium currents in inferior colliculus neurons. Soc Neurosci Abstr. 1997;23:1187. doi: 10.1016/s0306-4522(00)00006-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.O’Dowd DK, Rebera AB, Spitzer NC. Development of voltage-dependent calcium, sodium and potassium currents in Xenopus spinal neurons. J Neurosci. 1988;8:792–805. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.08-03-00792.1988. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Oliver DL, Shneiderman A. The anatomy of the inferior colliculus: a cellular basis for integration of monaural and binaural information. In: Altschuler RA, Bobbins RP, Clopton BM, Hoffman DW, editors. Neurobiology of hearing: the central auditory system. Raven; New York: 1991. pp. 195–222. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Perney TM, Kaczmarek LK. Expression and regulation of mammalian K channel genes. Semin Neurosci. 1993;5:135–145. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Perney TM, Kaczmarek LK. Localization of a high threshold potassium channel in the rat cochlear nucleus. J Comp Neurol. 1997;386:178–202. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Perney TM, Marshall J, Martin KA, Hockfiels S, Kaczmarek LK. Expression of the mRNAs for the Kv3.1 potassium channel gene in the adult and developing rat brain. J Neurophysiol. 1992;3:756–766. doi: 10.1152/jn.1992.68.3.756. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Peruzzi D, Oliver DL. Intracellular responses to current injection in slices of rat inferior colliculus (IC). Soc Neurosci Abstr. 1994;20:321. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Pierson M, Snyder-Keller A. Development of frequency-selective domains in inferior colliculus of normal and neonatally noise-exposed rats. Brain Res. 1994;636:55–67. doi: 10.1016/0006-8993(94)90175-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Ribera AB, Spitzer NC. A critical period of transcription required for differentiation of the action potential of spinal neurons. Neuron. 1989;2:1055–1062. doi: 10.1016/0896-6273(89)90229-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Ribera AB, Spitzer NC. Developmental regulation of potassium channels and the impact on neuronal differentiation. In: Narahashi T, editor. Ion channels. Plenum; New York: 1992. pp. 1–38. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Shatz CJ. Emergence of order in visual system development. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1996;93:602–608. doi: 10.1073/pnas.93.2.602. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Smith PH. Anatomy and physiology of multipolar cells in the rat inferior colliculus cortex using the in vitro brain slice technique. J Neurosci. 1992;12:3700–3715. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.12-09-03700.1992. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Spitzer NC. A developmental handshake: neuronal control of ionic currents and their control of neuronal differentiation. J Neurobiol. 1991;22:659–673. doi: 10.1002/neu.480220702. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Wang L-Y, Gan L, Forsythe ID, Kaczmarek LK. Contribution of the Kv3.1 potassium channel to high-frequency firing in mouse auditory neurons. J Physiol (Lond) 1998;509:183–193. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-7793.1998.183bo.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Weiser M, Bueno E, Sekirnjak C, Martone ME, Baker H, Hillman BD, Chen S, Thornhill W, Ellisman M, Rudy B. The potassium channel subunit Kv3.1b is localized to somatic and axonal membranes of specific populations of CNS neurons. J Neurosci. 1995;15:4298–4314. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.15-06-04298.1995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Weiser M, Vega-Saenz de Miera E, Moreno H, Fransen ML, Hillman D, Baker H, Rudy B. Differential expression of Shaw-related K+ channels in the rat central nervous system. J Neurosci. 1994;14:949–972. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.14-03-00949.1994. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Wisgirda ME, Wang L-Y, Kaczmarek LK. Characterization of potassium currents in the rat inferior colliculus using the in vitro brain slice. Soc Neurosci Abstr. 1996;22:889. [Google Scholar]

- 38.Wong ROL, Chernjavsky A, Smith SJ, Shatz CJ. Early functional neuronal networks in the developing retina. Nature. 1995;374:716–718. doi: 10.1038/374716a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Yokoyama S, Imoto K, Kawamura T, Higashida H, Iwabe N, Miyata T, Numa S. Potassium channels from NG108–15 neuroblastoma-glioma hybrid cells. Primary structure and functional expression of cDNAs. FEBS Lett. 1989;259:37–42. doi: 10.1016/0014-5793(89)81488-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]