Abstract

Previous work from our laboratory indicated that female Wistar rats will self-administer ethanol (EtOH) directly into the posterior ventral tegmental area (VTA). These results suggested that VTA dopamine (DA) neurons might be involved in mediating the reinforcing actions of EtOH within this region. The objectives of this study were to determine (1) the dose–response effects for the self-administration of EtOH into the VTA of male Wistar rats, and (2) the involvement of VTA DA neurons in the reinforcing actions of EtOH within the VTA. Adult male Wistar rats were implanted stereotaxically with guide cannulas aimed at the posterior or anterior VTA. After 1 week, rats were placed in standard two-lever (active and inactive) experimental chambers for a total of seven to eight sessions. The first experiment determined the intracranial self-administration of EtOH (0–400 mg%) into the posterior and anterior VTA. The second experiment examined the effects of coadministration of the D2/3 agonist quinpirole on the acquisition and maintenance of EtOH self-infusions into the posterior VTA. The final experiment determined the effects of a D2 antagonist (sulpiride) to reinstate self-administration behavior in rats given EtOH and quinpirole to coadminister. Male Wistar rats self-infused 100–300 mg% EtOH directly into the posterior, but not anterior, VTA. Coadministration of quinpirole prevented the acquisition and extinguished the maintenance of EtOH self-infusion into the posterior VTA, and addition of sulpiride reinstated EtOH self-administration. The results of this study indicate that EtOH is reinforcing within the posterior VTA of male Wistar rats and suggest that activation of VTA DA neurons is involved in this process.

Keywords: ventral tegmental area, intracranial self-administration, ethanol reinforcement, dopamine, sulpiride, quinpirole

Introduction

The mesolimbic dopamine (DA) system has been postulated to mediate the reinforcing properties of drugs of abuse, including alcohol (Koob and Bloom 1988; Wise 1998). Several investigators have reported that ethanol (EtOH) can stimulate the mesolimbic DA system. Systemic administration of EtOH increased the activity of ventral tegmental area (VTA) neurons (Gessa et al., 1985) and enhanced somatodendritic DA release in the VTA (Campbell et al., 1996; Kohl et al., 1998) of Wistar rats. Bath perfusion of rat midbrain slices with EtOH increased the firing rate of VTA DA neurons (Brodie et al., 1990, 1995; Bunny et al., 2001). Moreover, bath application of EtOH to acutely dissociated VTA DA neurons increased their firing rate (Brodie et al., 1999). Overall, these results indicate that EtOH can stimulate the activity of VTA DA neurons.

The intracranial self-administration (ICSA) technique has been hypothesized to be a valid procedure to identify specific brain regions involved in the initiation of response–contingent behaviors for the delivery of a reinforcer (Bozarth and Wise 1980; Goeders and Smith 1987; McBride et al., 1999). Studies using the ICSA procedure have successfully isolated discrete brain regions in which opioids (Bozarth and Wise 1981; Devine and Wise, 1994), amphetamine (Hoebel et al., 1983), and cocaine (Goeders and Smith, 1983, 1986; McKinzie et al., 1999; Rodd-Henricks et al., 2002b) can produce reinforcing effects. Self-administration of drugs directly into discrete CNS sites seems to be a very salient reinforcer because a typical finding of ICSA studies is a rapid acquisition of self-administration behaviors (Bozarth and Wise 1981; Goeders and Smith, 1986; Carlezon et al., 1995; Rodd-Henricks et al., 2002a,b, 2003; Rodd et al., 2003, 2004).

Previous ISCA studies indicated that female rats self-administered EtOH directly into the VTA (Gatto at al. 1994) and that this reinforcing effect occurred in the posterior, but not the anterior, VTA (Rodd-Henricks et al., 2000). Furthermore, the self-administration of EtOH into the posterior VTA of female Wistar rats could be prevented with the coadministration of a 5-HT3 antagonist (Rodd-Henricks et al., 2003), suggesting that activation of 5-HT3 receptors is involved in mediating the reinforcing actions of EtOH within the posterior VTA. Local application of a 5-HT3 agonist into the VTA of Wistar rats dose-dependently increased the extracellular levels of DA (Campbell et al., 1996), suggesting that activation of 5-HT3 receptors can increase DA neuronal activity. Overall, these findings support the hypothesis that activation of DA neurons in the VTA is involved in the local reinforcing effects of EtOH.

The initial ICSA studies with EtOH were conducted with female rats because female rats maintained their body weight and head size better than male rats for easier and more accurate stereotaxic placements within subregions of the VTA (Ikemoto et al., 1997a,b; Rodd-Henricks et al., 2000, 2003). Some reports indicate that differences may exist between male and female rats in DA function in the striatum and nucleus accumbens (Becker, 1999) and in behavioral alterations to chronic EtOH (Devaud et al., 1999). Moreover, gender can influence the effects of EtOH at GABAA receptors in the CNS of rats (Devaud et al., 1998). Because all the previous studies on the self-administration of EtOH into the VTA have been conducted with female rats, the possibility of gender differences has not been examined thoroughly (Gatto et al., 1994; Rodd-Henricks et al., 2000, 2003; Rodd et al., 2003, 2004). Consequently, it has not been established whether gender may be a factor influencing EtOH self-infusion into the VTA.

Therefore, the present study was undertaken to determine the dose–response effects of EtOH within the VTA of male Wistar rats and whether the reinforcing effects of EtOH within the VTA of male Wistar rats exhibited the same heterogeneity as found for female Wistar rats (Rodd-Henricks et al., 2000). In addition, the study was also designed to test the hypothesis that activation of VTA DA neurons is involved in mediating the ICSA of EtOH into the VTA.

Materials and Methods

Animals. Experimentally naive male Wistar rats (Harlan, Indianapolis, IN), weighing 250–320 gm at the time of surgery, were used. Rats were double-housed on arrival and maintained on a 12 hr reverse light/dark cycle (lights off at 9:00 A.M.). Food and water were available ad libitum, except in the test chamber. Animals used in this study were maintained in facilities fully accredited by the Association for the Assessment and Accreditation of Laboratory Animal Care. All research protocols were approved by the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee and are in accordance with the guidelines of the Institutional Care and Use Committee of the National Institute on Drug Abuse, National Institutes of Health, and the Guide for the Care and Use of Laboratory Animals (National Research Council, 1996).

The number of animals indicated for each experiment represents 95% of the total number that underwent surgery; 5% of the animals were not included for analyses mainly because of the loss of the guide cannula before completion of all experimental sessions. The data for these animals were not used because their injection sites could not be verified.

Chemical agents and vehicle. The artificial CSF (aCSF) consisted of (in mm): 120.0 NaCl, 4.8 KCl, 1.2 KH2PO4, 1.2 Mg SO4, 25.0 NaHCO3, 2.5 CaCl2, and 10.0 d-glucose. Ethyl alcohol (190 proof; McCormick Distilling, Weston, MO), the DA D2 agonist quinpirole (Sigma, St. Louis, MO), and D2 antagonist sulpiride (Sigma) were dissolved in the aCSF solution, and the pH was adjusted to 7.4 ± 0.1.

Apparatus. The test chambers (30 × 30 × 26 cm) were situated in a sound-attenuating cubicle (64 × 60 × 50 cm; Coulbourn Instruments, Allentown, PA) and illuminated by a dim house light during testing. Two identical levers (3.5 × 1.8 cm) were mounted on a single wall of the test chamber, 15 cm above a grid floor, and were separated by 12 cm. Levers were raised to this level to avoid accidental brushing against the lever and to reduce responses as a result of general locomotor activation. Directly above each lever was a row of three different colored cue lights. The light (red) to the far right over the active bar was illuminated during resting conditions. A desktop computer equipped with an operant control system (L2T2 system; Coulbourn Instruments) recorded the data and controlled the delivery of infusate in relation to lever response.

An electrolytic microinfusion transducer system (Bozarth and Wise, 1980) was used to control microinfusions of drug or vehicle. Two platinum electrodes were placed in an infusate-filled gas-tight cylinder (28 mm in length by 6 mm in diameter) equipped with a 28 gauge injection cannula (Plastics One, Roanoke, VA). The electrodes were connected by a spring-coated cable (Plastics One) and a swivel (model 205; Mercotac, Carlsbad, CA) to a constant current generator (MNC, Shreveport, LA) that delivered 6 μA of quiescent current and 200 μA of infusion current between the electrodes. Depression of the active lever delivered the infusion current for 5 sec, which led to the rapid generation of H2 gas (raising the pressure inside the gas-tight cylinder), and, in turn, forcing 100 nl of the infusate through the injection cannula. During the 5 sec infusion and additional 5 sec timeout period, the house light and right cue light (red) were extinguished, and the left cue light (green) over the active lever flashed on and off at 0.5 sec intervals.

Animal preparation. While under isoflurane anesthesia, subjects were prepared for stereotaxical implanting of a 22 gauge guide cannula (Plastics One) into the right hemisphere; the guide cannula was aimed 1.0 mm above the target region. Coordinates (Paxinos and Watson, 1986) for placements into the posterior VTA were 5.4 mm posterior to bregma, 2.1 mm lateral to the midline, and 8.5 mm ventral from the surface of the skull at a 10° angle to the vertical. Coordinates for placements into the anterior VTA were 4.8 mm posterior to bregma, 2.1 mm lateral to the midline, and 8.5 mm ventral from the surface of the skull at a 10° angle to the vertical. In between experimental sessions, a 28 gauge stylet was placed into the guide cannula and extended 0.5 mm beyond the tip of the guide. After surgery, rats were housed individually and allowed to recover 7–10 d. Animals were handled for at least 5 min daily after the fourth recovery day. Subjects were not acclimated to the experimental chambers before the commencement of data collection, nor did they receive any prior operant training.

General test condition. For testing, subjects were brought to the testing room, the stylet was removed, and the injection cannula was screwed into place. To avoid trapping air at the tip of the injection cannula, the infusion current was delivered for 5 sec during insertion of the injector, which resulted in a single noncontingent administration of infusate at the beginning of the session. Injection cannulas extended 1.0 mm beyond the tip of the guide. The test chamber was equipped with two levers. Depression of the “active lever” (FR1 schedule of reinforcement) caused the delivery of a 100 nl bolus of infusate over 5 sec, followed by a 5 sec timeout period. During both the 5 sec infusion period and 5 sec timeout period, responses on the active lever were recorded but did not produce additional infusions. Responses on the “inactive lever” were recorded but did not result in infusions. The assignment of active and inactive lever with respect to the left or right position was counterbalanced among subjects. However, the active and inactive levers remained the same for each rat throughout the experiment. No shaping technique was used to facilitate the acquisition of lever responses. The number of infusions and responses on the active and inactive lever were recorded. The duration of each test session was 4 hr, and sessions occurred every other day.

Dose response. For the posterior VTA, Wistar rats were assigned randomly to one of eight groups (n = 5–8/group). A vehicle group received infusions of aCSF for all seven sessions. The other groups received infusions of 75, 100, 150, 200, 250, 300, or 400 mg% (16.5–88 mm) EtOH for the first four sessions. During the fifth and sixth sessions, all animals received infusions of aCSF. In the seventh session, rats were allowed to respond for their originally assigned infusate. A previous study indicated that stable responding on the EtOH lever was attained by sessions 3 and 4, extinction was reached within two sessions, and responding on the active lever was reinstated within one session when EtOH was restored in female Wistar rats (Rodd-Henricks et al., 2000). In addition, six rats from various EtOH groups (one with 100 mg%, two with 150 mg%, one with 200 mg%, one with 250 mg%, and one with 400 mg%) had placements outside the VTA. These subjects were collapsed across infusate groups and served as a neuroanatomical control. A total 60 Wistar rats completed the ICSA dose–response experiment.

For the anterior VTA placements, animals were assigned randomly to one of five groups (n = 7/group). One group (vehicle group) received infusions of aCSF over the seven sessions. The other groups received infusions of 100, 200, 300, or 400 mg% EtOH for the first four sessions. During the fifth and sixth sessions, all animals received infusions of aCSF. On the seventh session day, rats were allowed to respond for their originally assigned infusate. This paradigm was identical to that for rats implanted with guide cannulas aimed at the posterior VTA.

Coinfusion of quinpirole during acquisition and maintenance of EtOH ICSA. For the acquisition experiment, animals were assigned randomly to one of six groups (n = 3–5/group). A vehicle group received infusions of aCSF for all seven sessions. A group was given 100 μm quinpirole alone for all seven sessions. Separate groups coinfused either 1, 10, or 100 μm quinpirole with 200 mg% EtOH for all seven sessions. The sixth group self-infused 200 mg% EtOH throughout all seven sessions. The 200 mg% EtOH concentration was previously shown to produce maximal self-infusion behavior when given in the posterior VTA of female Wistar rats (Rodd-Henricks et al., 2000) and in male Wistar rats in the initial experiment. The 200 mg% concentration of EtOH is physiologically relevant and attainable by alcohol-preferring rats under free-choice alcohol drinking conditions (Rodd-Henricks et al., 2001).

For the maintenance experiment, animals were assigned randomly to one of six groups (n = 6–9/group). Separate groups received infusions of aCSF, 100 μm quinpirole, or 200 mg% EtOH for all seven sessions. Additional groups self-administered 200 mg% EtOH for the initial four sessions. During sessions 5 and 6, rats self-administered 200 mg% EtOH with 1, 10, or 100 μm quinpirole. During session 7, rats were again given 200 mg% EtOH alone.

Coinfusion of quinpirole and sulpiride during maintenance of EtOH ICSA. Animals were assigned randomly to one of two groups (n = 6–7/group). Both groups self-administered 200 mg% EtOH for the initial four sessions. During sessions 5 and 6, rats self-administered 200 mg% EtOH plus 100 μm quinpirole. During sessions 7 and 8, rats self-administered 200 mg% EtOH plus 100 μm quinpirole and 10 or 100 μm sulpiride. A concentration of 10 μm quinpirole was originally planned for this experiment, but the stock solution was diluted incorrectly and the mistake was not discovered until the experiments had been completed.

Histology. At the termination of the experiment, 1% bromophenol blue (0.5 μl) was injected into the infusion site. Subsequently, the animals were given a fatal dose of Nembutal and then decapitated. Brains were removed and immediately frozen at –70°C. Frozen brains were subsequently equilibrated at –15°C in a cryostat microtome and then sliced into 40 μm sections. Sections were then stained with cresyl violet and examined under a light microscope for verification of the injection site using the rat brain atlas of Paxinos and Watson (1986).

Statistical analysis. Data analysis of the dose–response experiment consisted of a placement times concentration times session mixed ANOVA, with a repeated measure of “session,” performed on the number of infusions. Additionally, for each individual group, lever discrimination was determined by type (active or inactive) times day mixed ANOVA with a repeated measure of session. Lever discrimination is a key factor when a stimulant is self-administered (e.g., EtOH, cocaine, amphetamine) to distinguish between reinforcement–contingent behavior and general drug-stimulated motor activity. Data analysis of the effects of quinpirole and quinpirole/sulpiride coadministration studies consisted of treatment group times session mixed ANOVAs, with repeated measures of session, performed on the number of infusions for the acquisition experiment and active lever responses for the maintenance experiment.

Results

Dose response

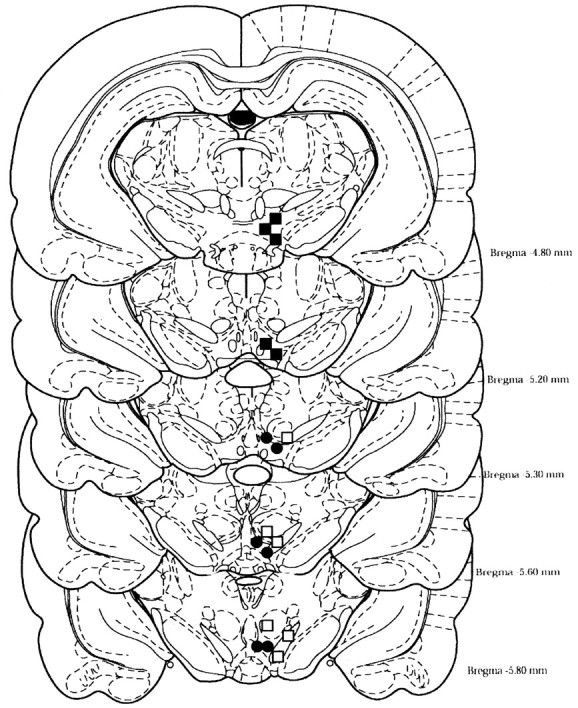

The posterior VTA was defined as the VTA region at the level of the interpeduncular nucleus, coronal sections at –5.3 to –6.0 mm bregma (Fig. 1). Cannula placements surrounding the VTA included injection sites located in the substantia nigra, interpeduncular nucleus, red nucleus, and caudal linear nucleus of the raphe. Data for these rats were not included in the statistical analyses. Cannula placements surrounding the VTA did not support ETOH self-administration (the average number of active and inactive lever responses during acquisition were 8 ± 2 and 7 ± 2, respectively), which is in agreement with findings reported previously (Rodd-Henricks et al., 2000; Rodd et al., 2004).

Figure 1.

Illustration depicts the injection sites in the anterior and posterior VTA, sites outside of the VTA, of male Wistar rats self-administering various concentrations of EtOH. Closed circles represent placements of injection sites within the posterior VTA (defined as –5.4 to –6.0 mm bregma), closed squares represent placements of injection sites in the anterior VTA (defined as –4.8 to –5.3 mm bregma), and open squares represent injection placements outside the VTA.

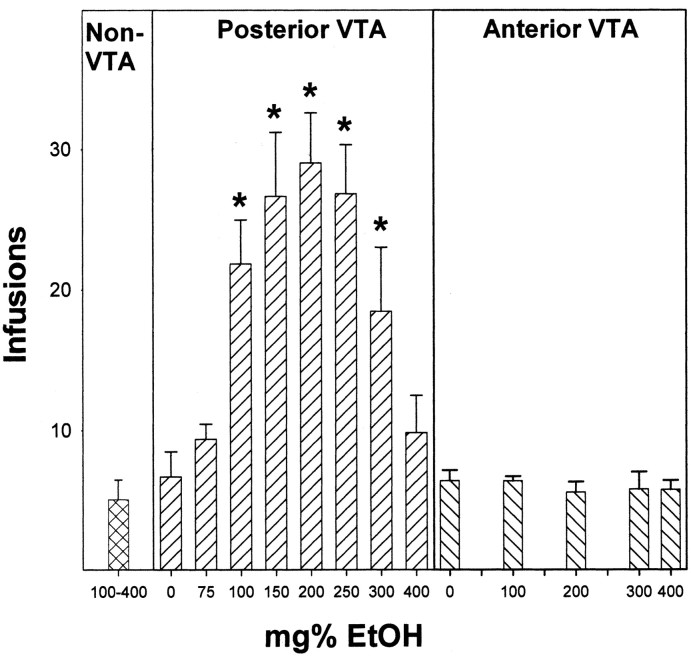

EtOH concentrations between 0 and 400 mg% were tested in the present study to determine the response–contingent behaviors of male Wistar rats with guide cannulas placed directly above the posterior and anterior VTA. Reducing the analysis to the average number of infusions received during the initial four sessions (Fig. 2) revealed that there was a significant effect of placement (F(1,80) = 52.4; p < 0.0001), concentration (F(8,80) = 8.8; p < 0.0001), and a placement times concentration interaction (F(4,80) = 7.5; p < 0.0001). In rats with injection tips located within the posterior VTA, there was a significant effect of EtOH concentration (F(7,46) = 6.6; p < 0.0001), with post hoc comparisons (Tukey'sb; p < 0.05) indicating that male Wistar rats given 100, 150, 200, 250, or 300 mg% EtOH received significantly more infusions than rats given 0, 75, or 400 mg% EtOH (Fig. 2). In contrast to the posterior VTA data, concentrations of 100, 200, 300, or 400 mg% EtOH were not significantly self-infused into the anterior VTA (group: F(4,29) = 0.2, p = 0.93, p = 0.84; session times group: F(12,87) = 0.4, p = 0.95).

Figure 2.

Dose–response graph for the number of infusions averaged over the first four sessions for the self-infusion of 100–400 mg% EtOH into non-VTA sites (a); 0, 75, 100, 150, 200, 250, 300, and 400 mg% EtOH into the posterior VTA (b); and 0, 100, 200, 300, or 400 mg% EtOH into the anterior VTA of male Wistar rats (c). The asterisks indicate that the number of infusions administered is significantly greater (p < 0.05) than aCSF. Data are the means ± SEM; for non-VTA sites, n = 6; for posterior VTA, n = 6–8/dose; and for anterior VTA, n = 6–7/dose.

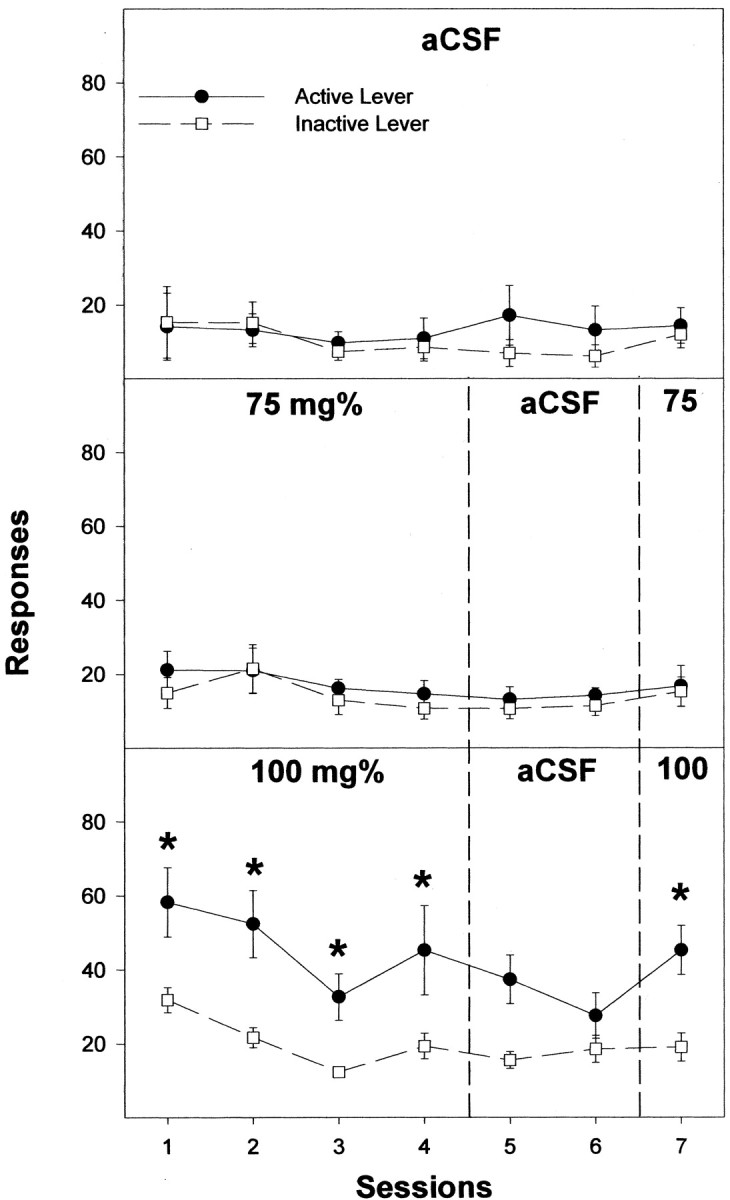

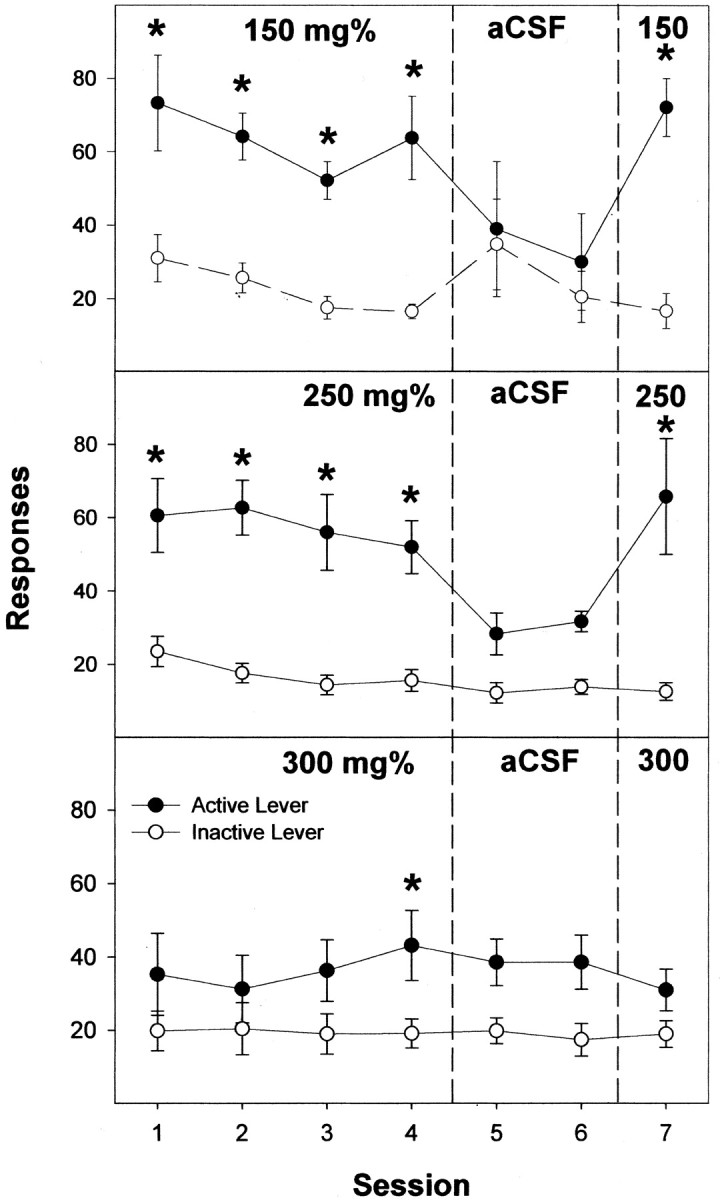

Active lever responses for male Wistar rats self-administering 100 mg% (Fig. 3, bottom), 150 mg% (Fig. 4, top), 200 mg% (see Fig. 6, top), and 250 mg% (Fig. 4, middle) EtOH into the posterior VTA were higher than in rats self-administering aCSF or 75 or 400 mg% EtOH during sessions 1–4 (all F(7,46) > 6.6; all p < 0.0001; post hoc Tukey's b; p < 0.05). For rats given 300 mg% EtOH, the only session when active lever responses were significantly higher than responses for the aCSF controls was during session 4 (Fig. 4, bottom). In sessions 5 and 6, when aCSF was substituted for EtOH, rats in the 100–250 mg% EtOH groups displayed reduced responding on the active lever (all F(2,14) > 13.5; all p < 0.001). In session 7, when EtOH was restored, rats self-administering either 100–250 mg% into the posterior VTA increased the number of active lever responses compared with session 6 (all F(1,7) > 14.4; all p < 0.007).

Figure 3.

Responses on the active and inactive lever by male Wistar rats for the self-infusion of aCSF for seven consecutive sessions, or 75 or 100 mg% EtOH directly into the posterior VTA for the first four sessions (acquisition), aCSF for sessions 5 and 6 (extinction), and EtOH again in session 7 (reinstatement). The asterisks indicate responses on the active lever were significantly higher (p < 0.05) than responses on the inactive lever for that session. Data are the means ± SEM; n = 6–8/group.

Figure 4.

Responses on the active and inactive lever by male Wistar rats for the self-infusion of 150, 250, or 300 mg% EtOH directly into the posterior VTA for the first four sessions (acquisition), aCSF for sessions 5 and 6 (extinction), and EtOH again in session 7 (reinstatement). The asterisks indicate responses on the active lever were significantly higher (p < 0.05) than responses on the inactive lever for that session. Data are the means ± SEM; n = 6–8/group.

Figure 6.

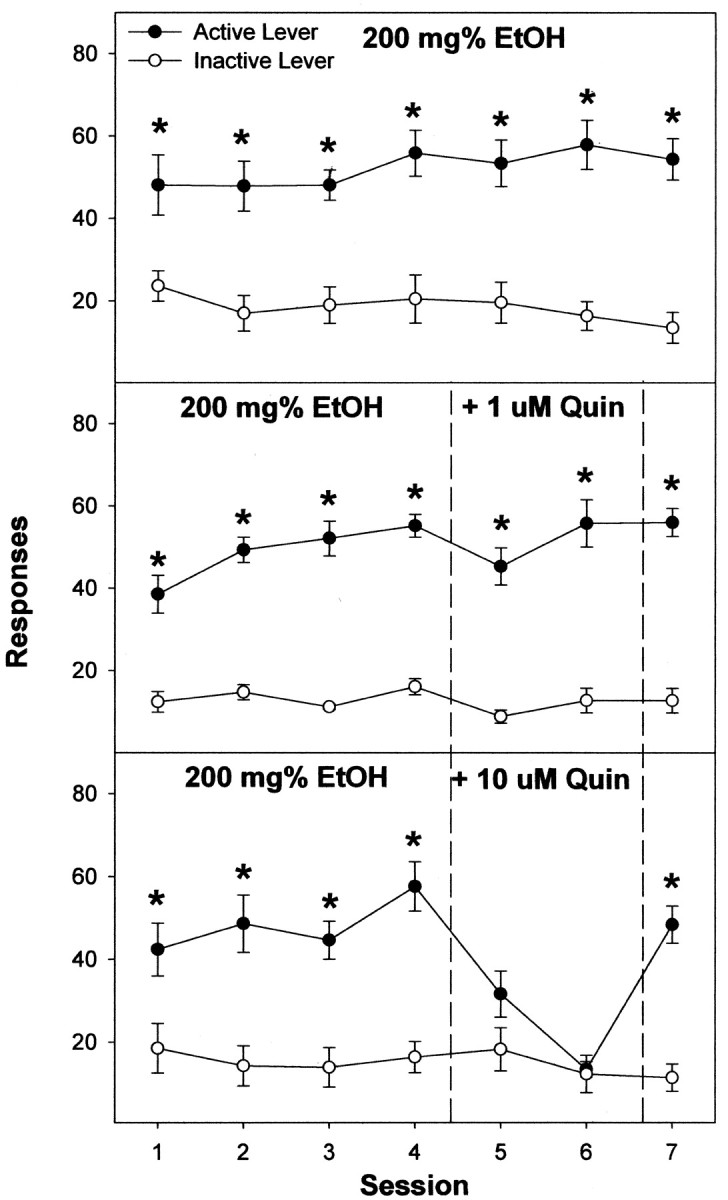

Responses on the active and inactive lever by male Wistar rats for the self-infusion of 200 mg% EtOH for seven consecutive sessions (a, top); 200 mg% EtOH for the first four sessions and 200 mg% EtOH plus 1 or 10μm quinpirole (Quin) in sessions 5 and 6 (b, middle and bottom); and 200 mg% EtOH again in session seven directly into the posterior VTA (c). The asterisks indicate responses on the active lever were significantly higher (p < 0.05) than responses on the inactive lever for that session. Data are the means ± SEM; n = 6–8/group.

Throughout the sessions, the number of lever presses by the aCSF controls with injector placements within the posterior VTA did not differ (p = 0.43) between the active and inactive bar (Fig. 3). The 100–250 mg% groups (Figs. 3 and 4) discriminated between the active and inactive lever throughout the acquisition sessions (all p < 0.027), did not discriminate during extinction in sessions 5 and 6 (all p > 0.067), and regained lever discrimination during reinstatement in session 7 (all p < 0.004). In contrast, the 300 mg% group only discriminated between active and inactive levers during the fourth session.

Coinfusion of quinpirole during acquisition and maintenance of EtOH ICSA

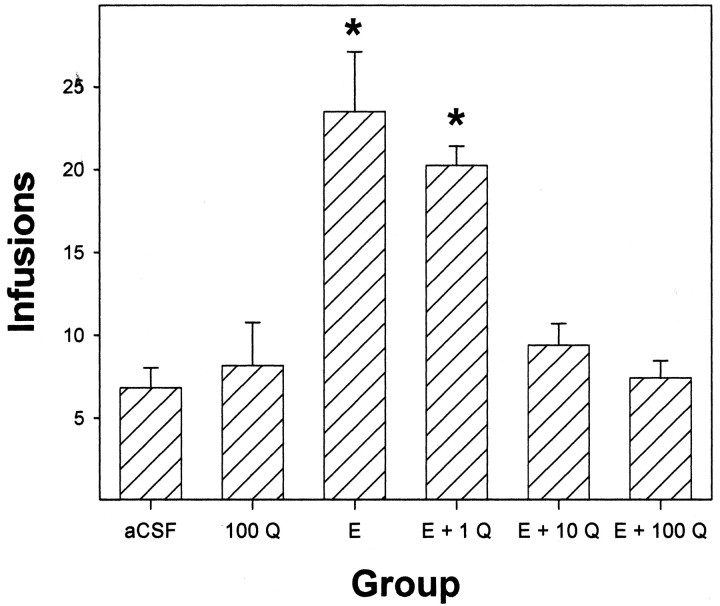

For the acquisition experiment, rats had comparably low infusions of aCSF and 100 μm quinpirole into the posterior VTA (Fig. 5) and did not discriminate the active from the inactive lever in any of the seven sessions (data not shown). In contrast, rats given 200 mg% EtOH alone or 200 mg% EtOH plus 1 μm quinpirole averaged 21–24 infusions/session across the seven sessions, which was significantly higher (p < 0.05; Tukey's b) than the aCSF group or the other groups (F(5,44) = 6.4; p < 0.001). Coadministration of 10 or 100 μm quinpirole with 200 mg% EtOH throughout the seven sessions reduced the number of infusions significantly below that found for 200 mg% EtOH alone to levels found for aCSF or quinpirole alone (Fig. 5).

Figure 5.

Averaged number of infusions over seven sessions for the self-infusion of aCSF, 100 μm quinpirole (Q), 200 mg% ethanol (E), and 200 mg% E plus 1, 10, or 100 μm Q into the posterior VTA. The asterisks indicate that the number of infusions administered is significantly greater (p < 0.05) than aCSF. Data are the means ± SEM; n = 3–5/group.

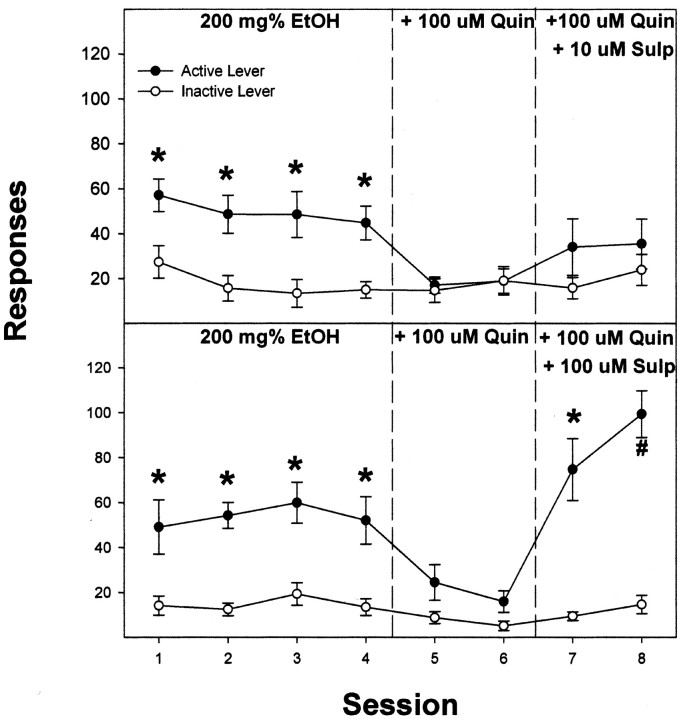

For the maintenance experiment with quinpirole, rats readily self-infused 200 mg% EtOH (22 ± 2 infusions/session) and discriminated the active from the inactive lever (all F(1,7) > 21.5; all p < 0.0001) throughout the first four sessions (Figs. 6 and 7). The effects of 1, 10, and 100 μm quinpirole on EtOH self-infusions were determined by examining responses on the active lever in session 4 versus responses on the active lever in sessions 5 and 6. This analysis revealed a significant effect of session for rats self-administering 200 mg% EtOH plus 10 or 100 μm quinpirole (all F(2,14) > 17.1; all p < 0.001). Post hoc comparisons revealed that the number of responses on the active lever during session 4 was significantly higher than during sessions 5 and 6. In addition, coadministration of 10 or 100 μm quinpirole did not alter the low number of responses on the inactive lever (all F(2,14) < 1.4; all p > 0.26). Comparison of responses on the active lever in session 7, when EtOH alone was restored, with active lever responses in sessions 5 and 6 (Fig. 6 shows data for the 10 μm quinpirole group, which were similar to the 100 μm concentration), indicated significantly higher responses on the active lever in session 7 (F(2,14) = 15.4; p < 0.001). Levels of responding in session 7 had almost returned to levels observed during session 4.

Figure 7.

Responses on the active and inactive lever by male Wistar rats for the self-infusion of 200 mg% EtOH for the first four sessions, 200 mg% EtOH plus 100 μm quinpirole (Quin) in sessions 5 and 6, and 200 mg% EtOH plus 100 μm Quin and 10 or 100 μm sulpiride (Sulp) in sessions 7 and 8 directly into the posterior VTA. The asterisks indicate responses on the active lever were significantly higher (p < 0.05) than responses on the inactive lever for that session. The # indicates that responses on the active lever were significantly higher than inactive lever responses in that session and active lever responses in session 4. Data are the means ± SEM; n = 6–7/group.

Coinfusion of quinpirole and sulpiride during maintenance of EtOH ICSA

The data for the first six sessions replicated the findings of the quinpirole-maintenance study in that rats self-administered 200 mg% EtOH in sessions 1–4 and reduced self-administration when 100 μm quinpirole was coadministered with EtOH in sessions 5 and 6 (Fig. 7). Coadministering 100 μm sulpiride (but not 10 μm sulpiride) with EtOH plus quinpirole reinstated responding on the active lever in sessions 7 and 8. In the group that self-administered 200 mg% EtOH plus 100 μm quinpirole and 100 μm sulpiride, there was higher responding on the active lever during sessions 7 and 8 than during session 6 (F(2,10) = 52.2; p < 0.0001). In addition, the average responses in session 8 were higher than the average responses during sessions 1–4 (F(5,25) = 7.3; p < 0.0001; post hoc p < 0.05).

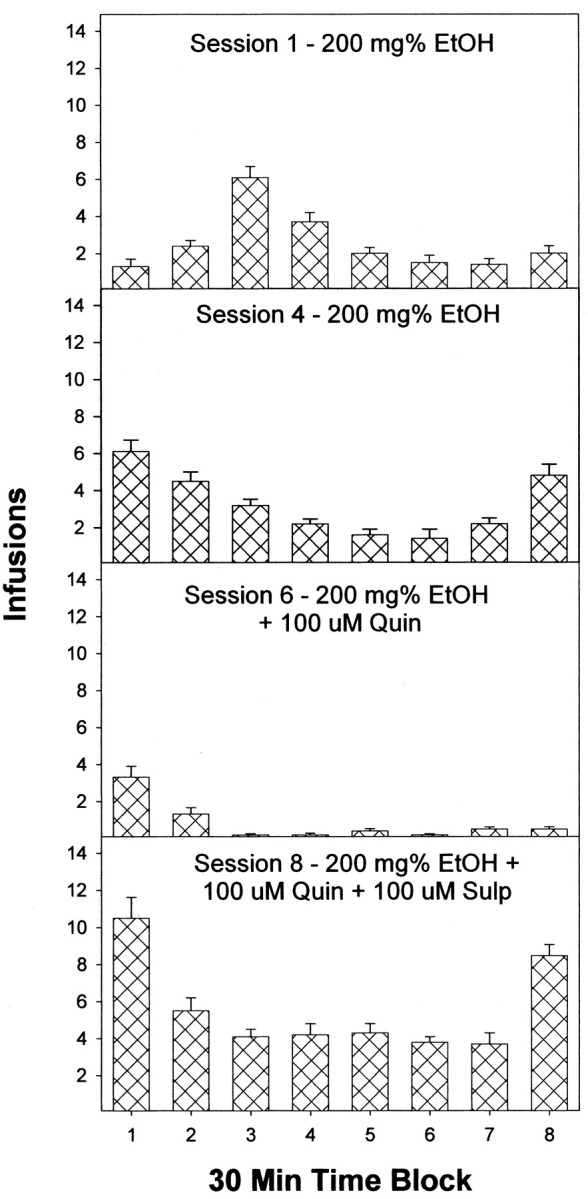

The pattern of self-infusion in 30 min blocks during the 4 hr sessions for rats self-administering 200 mg% EtOH alone (acquisition), 200 mg% EtOH plus quinpirole, and 200 mg% EtOH plus quinpirole and sulpiride indicates the distribution of infusions over the session (Fig. 8). During the initial session, rats appear to acquire EtOH self-administration in the second hour of testing. After the acquisition of EtOH self-administration (session 4), rats display a high level of initial self-administration, a consistent level of responding during the middle portion of the session, and an increase in self-infusions during the last period of the session. When quinpirole was coadministered with EtOH (session 6), rats primarily self-infused within the initial hour of the session (very similar to that observed during aCSF substitution). When sulpiride was added to the EtOH plus quinpirole infusate, self-infusions were restored, and the pattern of infusions was similar to that seen in session 4 with 200 mg% EtOH alone, although the number of infusions tended to be higher (Fig. 8).

Figure 8.

Number of infusions during the 4 hr session in 30 min blocks for male Wistar rats self-infusing 200 mg% EtOH into the posterior VTA during the first four sessions (only sessions 1 and 4 are shown), 200 mg% EtOH plus 100 μm quinpirole (Quin) in sessions 5 and 6 (only session 6 is shown), and 200 mg% EtOH μm quinpirole and 100 μm sulipride (Sulp) in sessions 7 and 8 (only session 8 is shown). Data are the means ± SEM; n = 6.

Discussion

The major findings of this study indicate that EtOH is self-administered directly into the posterior, but not anterior, VTA of male Wistar rats (Fig. 2) and that activating D2 autoreceptors within the posterior VTA prevents the acquisition (Fig. 5) and reduces the maintenance (Figs. 6 and 7) of EtOH self-infusion into the posterior VTA. The results of this study suggest that EtOH is producing reinforcing effects within the VTA and that there is regional heterogeneity within the VTA with regard to the reinforcing effects of EtOH. Moreover, activation of local D2 autoreceptors within the posterior VTA reduces EtOH self-infusions, which can be restored when the D2 agonist quinpirole is removed (Fig. 6) or can be blocked if a D2 antagonist is given concomitantly (Fig. 7).

Because local perfusion of a D2 agonist will activate D2 autoreceptors and thereby reduce the firing rates of VTA DA neurons (Congar et al., 2002; Jeziorski and White, 1989), the finding that coinfusion of quinpirole reduces EtOH self-administration suggests that activation of DA neurons is involved in mediating the reinforcing actions of EtOH within the posterior VTA. In support of this interpretation, the results of in vivo electrophysiological (Gessa et al., 1985) and microdialysis (Campbell et al., 1996; Kohl et al., 1998) studies indicated that systemic EtOH administration increased the firing rates of VTA DA neurons and enhanced somatodendritic DA release in the VTA. Moreover, in vitro electrophysiological findings indicated that EtOH activated VTA DA neurons in tissue slices (Brodie et al., 1990, 1995; Bunny et al., 2001) or in acutely dissociated VTA DA neurons (Brodie et al., 1999), suggesting that EtOH can have a direct stimulating effect on VTA DA neuronal activity.

In addition to a possible direct effect of EtOH on VTA DA neuronal activity, the tone of the VTA DA system likely plays a role in the actions of EtOH within the VTA. For example, DA neurons within the VTA are regulated, in part, by excitatory amino acids (EAA), neurotensin, nicotinic receptors, and inhibitory GABAA and GABAB receptors (for review, see Kalivas, 1993). The 5-HT system may also play a role in mediating the reinforcing actions of EtOH in the posterior VTA. The transtegmental 5-HT pathway, which originates in the dorsal and median raphe nuclei, primarily innervate DA and non-DA neurons in the posterior VTA with little indication of innervation in the anterior VTA (Herve et al., 1987). Furthermore, coadministration of 5-HT3 receptor antagonists inhibited the acquisition and extinguished the maintenance of EtOH self-infusions into the posterior VTA of Wistar rats (Rodd-Henricks et al., 2003).

The finding that the addition of the D2 antagonist to 200 mg% EtOH plus 100 μm quinpirole solution restored active lever responding (Fig. 7) provides additional support for an interpretation that activation of D2 autoreceptors within the posterior VTA reduces EtOH self-infusions. Moreover, the averaged responses on the active lever for sessions 7 and 8, when sulpiride was present, were higher than the averaged responses across sessions 1–4, when only 200 mg% was given (Fig. 7), suggesting that sulpiride was blocking the tonic activation of D2 autoreceptors by endogenous DA, thereby increasing the activity of VTA DA neurons and EtOH self-administration.

The functional heterogeneity observed within the VTA for the self-administration of EtOH (Fig. 2) is compatible with studies demonstrating functional differences between the anterior and posterior VTA in the locomotor activating effects of GABAA agonists and antagonists (Arnt and Scheel-Kruger, 1979), and in the ICSA of GABAA agonists and antagonists (Ikemoto et al., 1997a, 1998). Injection of a GABAA or GABAB agonists into the posterior but not anterior VTA increased locomotor activity, whereas injections of agonists into the anterior VTA did not affect locomotor activity (Arnt and Scheel-Kruger, 1979; Boehm et al., 2002). GABA agents are also self-infused differentially between anterior and posterior VTA (Ikemoto et al., 1997a, 1998), and the posterior, but not the anterior, VTA supported the self-infusion of acetaldehyde, the active metabolite of EtOH (Rodd-Henricks et al., 2002a).

The results of the present study with male rats are in agreement with a previous study (Rodd-Henricks et al., 2000) that indicated that female Wistar rats would self-administer 150–250 mg% EtOH directly into the posterior, but not anterior, VTA. However, there were some apparent gender differences. Male Wistar rats seem to be more sensitive to the reinforcing properties of EtOH than female Wistar rats, in that the male rats reliably self-infuse 100 mg% EtOH (Fig. 3), whereas female rats did not (Rodd-Henricks et al., 2000). In addition, female Wistar rats self-infused 300 and 400 mg% during the initial acquisition sessions, whereas male rats reliably responded for 300 mg% EtOH only in the last acquisition session (Fig. 4) and did not reliably respond for 400 mg% during the four acquisition sessions (Fig. 2). Although these differences are relatively small, they may indicate gender differences in the sensitivity of the VTA to the reinforcing effects of EtOH.

The rapid acquisition of lever discrimination and EtOH self-administration into the posterior VTA by male Wistar rats (Figs. 3, 4, 6,7,8) is similar to the rapid acquisition demonstrated by female Wistar rats (Rodd-Henricks et al., 2000). Most ICSA studies indicate that rats readily learn to discriminate the active from the inactive lever for self-infusion of EtOH (Gatto et al., 1994; Rodd-Henricks et al., 2000, 2003), opioids (Bozarth and Wise, 1981; Devine and Wise 1994), GABAA antagonists (Ikemoto et al., 1997a), and acetaldehyde (Rodd-Henricks et al., 2002a) into the VTA. Although the mechanisms underlying this rapid acquisition are unknown, they likely involve the mesolimbic DA system and the temporal association between pressing the lever and the almost immediate CNS rewarding effect.

Overall, the ICSA data suggest that EtOH can produce reinforcing effects within the posterior, but not anterior, VTA of male Wistar rats. The concentrations of EtOH (100–250 mg%) that were reinforcing are relevant pharmacologically and could be attained by rats under free-choice alcohol drinking conditions (Rodd-Henricks et al., 2001). The present study also provides pharmacological evidence that activation of VTA DA neurons is involved in mediating the reinforcing effects of EtOH within the posterior VTA.

Footnotes

This work was supported in part by research Grants AA12262, AA10721, and AA10717 from the National Institute of Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism and Grant NIMH19457 from the National Institute on Mental Health.

Correspondence should be addressed to Dr. Zachary A. Rodd, Institute of Psychiatric Research, Indiana University School of Medicine, 791 Union Drive, Indianapolis, IN 46202-4887. E-mail: zrodd@iupui.edu.

DOI:10.1523/JNEUROSCI.1319-03.2004

Copyright © 2004 Society for Neuroscience 0270-6474/04/241050-08$15.00/0

References

- Arnt J, Scheel-Kruger J (1979) GABA in the ventral tegmental area: differential regional effects on locomotion, aggression and food intake after microinjection of GABA agonists and antagonists. Life Sci 25: 1351–1360. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Becker JB (1999) Gender differences in dopaminergic function in striatum and nucleus accumbens. Pharmacol Biochem Behav 64: 803–812. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boehm II SL, Piercy MM, Bergstrom HC, Phillips TJ (2002) Ventral tegmental area region governs GABA(B) receptor modulation of ethanol-stimulated activity in mice. Neuroscience 115: 185–200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bozarth MA, Wise RA (1980) Electrolytic microinfusion transducer system: an alternative method of intra-cranial drug application. J Neurosci Methods 2: 273–275. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bozarth MA, Wise RA (1981) Intracranial self-administration of morphine into the ventral tegmental area in rats. Life Sci 28: 551–555. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brodie MS, Shefner SA, Dunwiddie TV (1990) Ethanol increases the firing rate of dopamine neurons of the rat ventral tegmental area in vitro. Brain Res 508: 65–69. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brodie MS, Trifunovic RD, Shefner SA (1995) Serotonin potentiates ethanol-induced excitation of ventral tegmental area neurons in brain slices from three different rat strains. J Pharmacol Exp Ther 273: 1139–1146. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brodie MS, Pesold C, Appel SB (1999) Ethanol directly excites dopaminergic ventral tegmental area reward neurons. Alcohol Clin Exp Res 23: 1848–1852. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bunny EB, Appel SB, Brodie MS (2001) Electrophysiological effects of cocaethylene, cocaine, and ethanol on dopaminergic neurons of the ventral tegmental area. J Pharmacol Exp Ther 297: 696–703. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Campbell AD, Kohl RR, McBride WJ (1996) Serotonin-3 receptor and ethanol-stimulated somatodendritic dopamine release. Alcohol 13: 569–574. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carlezon WA, Devine DP, Wise RA (1995) Habit-forming actions of nomifensine in nucleus accumbens. Psychopharmacology 122: 194–197. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Congar P, Bergevin A, Trudeau LE (2002) D2 receptors inhibit the secretory process downstream from calcium influx in dopaminergic neurons: implication of K+ channels. J Neurophysiol 87: 1046–1056. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Devaud LL, Fritschy JM, Morrow AL (1998) Influence of gender on chronic ethanol-induced alterations in GABA(a) receptors in rats. Brain Res 796: 222–230. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Devaud LL, Matthews DB, Morrow AL (1999) Gender impacts behavioral and neurochemical adaptations in ethanol-dependent rats. Pharmacol Biochem Behav 64: 841–849. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Devine DP, Wise RA (1994) Self-administration of morphine, DAMGO, and DPDPE into the ventral tegmental area of rats. J Neurosci 14: 1978–1984. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gatto GJ, McBride WJ, Murphy JM, Lumeng L, Li T-K (1994) Ethanol self-infusion into the ventral tegmental area by alcohol-preferring rats. Alcohol 11: 557–564. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gessa GL, Muntoni F, Collu M, Vargiu L, Mereu G (1985) Low doses of ethanol activate dopaminergic neurons in the ventral tegmental area. Brain Res 348: 201–203. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goeders NE, Smith JE (1983) Cortical dopaminergic involvement in cocaine reinforcement. Science 221: 773–775. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goeders NE, Smith JE (1986) Reinforcing properties of cocaine in the medial prefrontal cortex: primary action on presynaptic dopaminergic terminals. Pharmacol Biochem Behav 25: 191–199. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goeders NE, Smith JE (1987) Intracranial self-administration methodologies. Neurosci Biobehav Rev 11: 319–329. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Herve D, Pickel VM, Joh TH, Beaudet A (1987) Serotonin axon terminals in the ventral tegmental area of the rat: fine structure and synaptic input to dopaminergic neurons. Brain Res 435: 71–83. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hoebel BG, Monaco AP, Hernandez L, Aulisi EF, Stanley BG, Lenard L (1983) Self-injection of amphetamine directly into the brain. Psychopharmacology 81: 158–163. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ikemoto S, Murphy JM, McBride WJ (1997a) Self-infusion of GABAA receptor antagonists directly into the ventral tegmental area and adjacent regions. Behav Neurosci 110: 331–345. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ikemoto S, Kohl RR, McBride WJ (1997b) GABAA receptor blockade in the anterior ventral tegmental area increase extracellular levels of dopamine in the nucleus accumbens of rats. J Neuorchem 69: 137–143. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ikemoto S, Murphy JM, McBride WJ (1998) Regional differences within the rat ventral tegmental area for muscimol self-infusions. Pharmacol Biochem Behav 61: 87–92. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jeziorski M, White FJ (1989) Dopamine agonists at repeated “autoreceptor-selective” doses: effects upon the sensitivity of A10 dopamine autoreceptors. Synapse 4: 267–280. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kalivas PW (1993) Neurotransmitter regulation of dopamine neurons in the ventral tegmental area. Brain Res Rev 18: 75–113. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kohl RR, Katner JS, Chernet E, McBride WJ (1998) Ethanol and negative feedback regulation of mesolimbic dopamine release in rats. Psychopharmacology 139: 79–85. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Koob GF, Bloom FE (1988) Cellular and molecular mechanisms of drug dependence. Science 242: 715–723. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McBride WJ, Murphy JM, Ikemoto S (1999) Localization of brain reinforcement mechanisms: intracranial self-administration and intracranial place-conditioning studies. Behav Brain Res 101: 129–152. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McKinzie DA, Rodd-Henricks ZA, Dagon CT, Murphy JM, McBride WJ (1999) Cocaine is self-administered into the shell region of the nucleus accumbens in Wistar rats. Ann NY Acad Sci 877: 788–791. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Paxinos G, Watson C (1986) The rat brain in stereotaxic coordinates, Ed 2. New York: Academic.

- Rodd ZA, Bell RL, Zhang Y, Goldstein A, Zaffaroni A, McBride WJ, Li T-K (2003) Salsolinol produces reinforcing effects in the nucleus accumbens shell of alcohol-preferring (P) rats. Alcohol Clin Exp Res 27: 440–449. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rodd ZA, Bell RL, Melendez RI, Kuc KA, Lumeng L, Li T-K, Murphy JM, McBride WJ (2004) Comparison of intracranial self-administration of ethanol within the posterior ventral tegmental area between alcohol-preferring (P) and Wistar rats. Alcohol Clin Exp Res, in press. [DOI] [PubMed]

- Rodd-Henricks ZA, McKinzie DL, Crile RS, Murphy JM, McBride WJ (2000) Regional heterogeneity for the intracranial self-administration of ethanol within the ventral tegmental area of female Wistar rats. Psychopharmacology 149: 217–224. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rodd-Henricks ZA, Bell RL, Kuc KA, Murphy JM, McBride WJ, Lumeng L, Li T-K (2001) Effects of concurrent access to multiple ethanol concentrations and repeated deprivations on alcohol intake of alcohol-preferring rats. Alcohol Clin Exp Res 25: 1140–1150. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rodd-Henricks ZA, Melendez RI, Zaffaroni A, Goldstein A, McBride WJ, Li T-K (2002a) The reinforcing effects of acetaldehyde in the posterior ventral tegmental area of alcohol-preferring rats. Pharmacol Biochem Behav 72: 55–64. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rodd-Henricks ZA, McKinzie DL, Li T-K, Murphy JM, McBride WJ (2002b) Cocaine is self-administered into the shell, but not the core, of the nucleus accumbens of Wistar rats. J Pharmacol Exp Ther 303: 1216–1226. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rodd-Henricks ZA, McKinzie DL, Li T-K, Murphy JM, McBride WJ (2003) Effects of serotonin-3 receptors antagonists on the intracranial self-administration of ethanol within the ventral tegmental area of Wistar rats. Psychopharmacology 165: 252–259. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wise RA (1998) Drug-activation of brain reward pathways. Drug Alcohol Depend 51: 13–22. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]