Abstract

Uveoparotid fever, also known as Heerfordt-Waldenström syndrome, is an uncommon acute presentation of systemic sarcoidosis. Patients may have features of complete/classic or incomplete disease. Early diagnosis and multidisciplinary care should be initiated to prevent sequelae. Herein, the authors report a rare case of retrospectively diagnosed incomplete uveoparotid fever in a patient with anterior uveitis, parotid gland enlargement, and fever who presented to our dermatology clinic with cutaneous sarcoidosis.

Keywords: Heerfordt-Waldenström, sarcoidosis, uveoparotid fever

Acute presentations of sarcoidosis are uncommon.1 A syndromic acute presentation is uveoparotid fever, also known as Heerfordt-Waldenström syndrome. Classical features are anterior uveitis, enlarged parotid gland, facial nerve paralysis, and fever. However, incomplete presentations also occur. These variants account for 4.1% to 5.6% of cases diagnosed as uveoparotid fever.2

CASE PRESENTATION

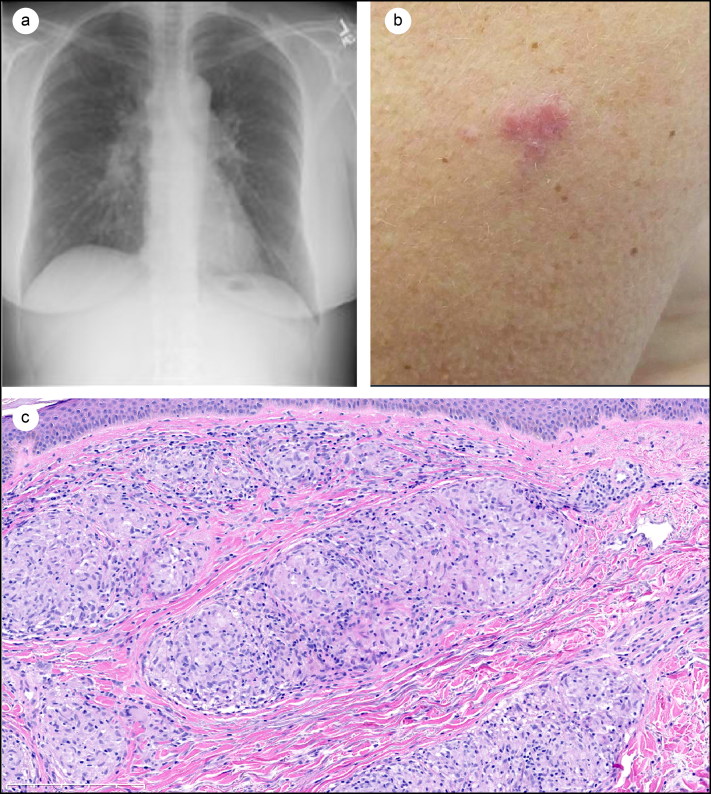

A 54-year-old woman presented to the dermatology clinic with a lesion of her left lateral arm. Her history was significant for episodes of epiphora, parotid enlargement, and subjective, recurrent fevers evaluated by several providers. Four years earlier, she acutely developed these symptoms. At that time, she was seen by an ophthalmologist for epiphora and eye redness concerning for nasolacrimal duct obstruction with uveitis. A diagnosis of self-resolving anterior uveitis was made, and a stent was placed in the left nasolacrimal duct. Intraoperative biopsy revealed noncaseating granulomas. Soon thereafter, the patient developed a mass of the parotid. Biopsy again revealed noncaseating granulomas. Workup for sarcoidosis was initiated. Chest radiograph demonstrated hilar lymphadenopathy and interstitial opacities consistent with pulmonary sarcoidosis (Figure 1a). Four years later, her primary care provider referred her to our clinic after she developed a skin lesion.

Figure 1.

(a) Chest x-ray demonstrating prominent hilar lymphadenopathy and interstitial infiltrates suggestive of pulmonary sarcoidosis. (b) Erythematous plaque without scale of the left lateral arm. (c) Histology of the 6-mm punch biopsy revealed noncaseating granulomas indicative of sarcoidosis (hematoxylin and eosin stain, 13× magnification).

On presentation, she had an enlarged pink-colored lesion of her left lateral arm present for 4 to 5 months. No other lesions were reported. Moisturizers were ineffective, and the patient reported no alleviating or exacerbating factors. The lesion was nontender, nonpruritic, and nonbleeding. Pertinent negative review of systems was lack of weight loss or night sweats and lack of polyarthralgia/polyarthritis, Additional medical and family history was unremarkable.

On exam, a 2-cm erythematous plaque without scale was noted on the left lateral arm (Figure 1b). Additionally, a 1.5-cm subcutaneous nodule of the right mandibular area and a skin-colored papule of the right nasal ala region were noted. A 6-mm punch biopsy of the left arm lesion was subsequently performed. The pathology report indicated noncaseating granulomas, which in this clinical context were pathognomonic for systemic sarcoidosis (Figure 1c). The patient’s cutaneous lesions were clinically interpreted as progression of her systemic sarcoidosis. As such, she was started on methotrexate 10 mg. A retrospective diagnosis of incomplete uveoparotid fever, a rare manifestation of sarcoidosis, was made. Lack of joint symptoms or erythema nodusum ruled out Löfgren syndrome, another acute sarcoidosis presentation.3

DISCUSSION

The diagnostic criteria of uveoparotid fever are not standardized and rely on cases from the early 1900s.4 Some cases describe the classic, or complete, symptoms: anterior uveitis, parotid gland involvement, facial nerve palsy, and fever.5 However, other cases described as classic note three symptoms (no fever).4 Additionally, incomplete presentations (two out of three symptoms) also occur.6 Other reports mention parotitis (in lieu of parotid gland enlargement) as a diagnostic criterion.7 We clinically diagnosed our patient with incomplete uveoparotid fever.

The classic diagnostic criteria reflect symptoms related to the noncaseating granulomas of sarcoidosis in specific regions, leading to localized symptoms (e.g., facial nerve palsy). Though our patient did not have palsy, she had adjacent lesions causing parotid enlargement with pain. Additionally, though she did have symptoms of uveitis, she also had granulomas obstructing the nasolacrimal duct leading to epiphora. The classic criteria reflect a unique presentation but may be too strict in discounting related cases. Simultaneous manifestation of granulomas near the parotid and periorbital region (possibly along with fever) is, in itself, a rare occurrence. It may be useful to reconsider uveoparotid fever as a clinical diagnosis with sarcoidosis of the parotid gland, nasolacrimal/orbital region, fevers, or other clinical features demonstrative of sarcoidosis. Broader diagnostic criteria may allow for earlier identification of the syndrome, prompt treatment, and initiation of multidisciplinary care. For instance, our patient had papules of the right nasal ala, which may indicate upper respiratory sarcoidosis. Laryngoscopy (unremarkable in our patient) is suggested.8 Such coordinated care may be facilitated via earlier recognition.

Treatment of sarcoidosis includes topical and systemic agents. Topical corticosteroids can be used for cutaneous lesions. Systemic treatment is typically reserved for symptomatic and severe pulmonary disease, neurologic involvement, symptomatic hypercalcemia, and ocular disease unresponsive to topical therapy.9 Our patient’s lung disease did not meet criteria for systemic treatment (asymptomatic; stage II, which has a 40% to 70% rate of spontaneous resolution). However, her evolving presentation with a new cutaneous plaque warranted consideration of a worsening course. In sarcoidosis, skin plaques are associated with a chronic course, documented to last up to 2 years in 91% of patients.10 A clinical decision was made to initiate systemic therapy.

The mainstays of systemic therapy are corticosteroids. However, evidence lacks randomized control data.11 Furthermore, our patient had osteoporosis, limiting corticosteroid use. The strongest recommendation for alternative systemic therapy is oral methotrexate, which is also effective in the treatment of cutaneous sarcoidosis.12

References

- 1.Lashari BH, Raza A, Chan V, Ward W. Sarcoidosis presenting as acute respiratory distress syndrome. Case Rep Med. 2018;2018:1–4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Fukuhara K, Fukuhara A, Tsugawa J, Oma S, Tsuboi Y. Radiculopathy in patients with Heerfordt’s syndrome: two case presentations and review of the literature. Brain Nerve. 2013;65:989–992. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Hebel JL, Snider RL, Mitchell D. Lofgren’s syndrome. Cutis. 1993;52:223–224. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Cogan DG. Uveoparotid fever. Am J Ophthalmol. 1935;18:637–640. doi: 10.1016/S0002-9394(35)92692-7. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Makimoto G, Miyahara N, Yoshikawa M, et al. Heerfordt’s syndrome associated with a high fever and elevation of TNF-alpha. Acta Med Okayama. 2016;70:273–277. doi: 10.18926/AMO/54503. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Dua A, Manadan A. Heerfordt’s syndrome, or uveoparotid fever. N Engl J Med. 2013;369:458. doi: 10.1056/NEJMicm1303454. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Jersild M. The syndrome of Heerfordt (uveo-parotid fever), a manifestation of Boeck’s sarcoid. J Int Med. 1938;97:322–328. doi: 10.1111/j.0954-6820.1938.tb09977.x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Jorizzo JL, Koufman JA, Thompson JN, White WL, Shar GG, Schreiner DJ. Sarcoidosis of the upper respiratory tract in patients with nasal rim lesions: a pilot study. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1990;22:439–443. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Bargagli E, Prasse A. Sarcoidosis: a review for the internist. Intern Emerg Med. 2018;13:325–331. doi: 10.1007/s11739-017-1778-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Mañá J, Marcoval J, Graells J, Salazar A, Peyrí J, Pujol R. Cutaneous involvement in sarcoidosis, relationship to systemic disease. Arch Dermatol. 1997;133:882–888. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Baughman RP, Lower EE. Evidence-based therapy for cutaneous sarcoidosis. Clin Dermatol. 2007;25:334–340. doi: 10.1016/j.clindermatol.2007.03.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Schutt AC, Bullington WM, Judson MA. Pharmacotherapy for pulmonary sarcoidosis: a Delphi consensus study. Respir Med. 2010;104:717–723. doi: 10.1016/j.rmed.2009.12.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]