Abstract

The purpose of this paper is to present a stepwise, multi-construct, innovative framework that supports the use of eHealth technology to reach sexual minority populations of color to establish trustworthiness and build trust. The salience of eHealth interventions can be leveraged to minimize the existing paradigm of medical mistrust among sexual minority populations of color living with chronic illnesses. These interventions include virtual environments and avatar-led eHealth videos, which address psychosocial and structural-level challenges related to mistrust. Our proposed framework addresses how eHealth interventions enable technology adoption and usage, anonymity, co-presence, self-disclosure, and social support and establish trustworthiness and build trust.

Keywords: Medical Mistrust, eHealth, Chronic Illness, Sexual and Gender Minorities, HIV

Introduction

The purpose of this paper is to present an innovative framework that supports the use of eHealth technology to reach sexual minority populations of color to establish trustworthiness and build trust. The salience of technology-based interventions can be leveraged to minimize the existing paradigm of medical mistrust among sexual minority populations of color living with chronic conditions. Chronic conditions are the leading cause of death in the United States (US) and have accounted for greater than 70% of all deaths per year.1,2 We define chronic conditions as a slow and prolonged course of either communicable,3 or non-communicable,4 diseases that may lead to other health-related complications and can adversely affect quality of life.5

Non-communicable diseases involving the cardiovascular and endocrine system are the most costly6,7 and serious. 6,8,9 Approximately 150 million persons are living with at least one chronic condition, and close to 30 million persons are living with five or more chronic conditions, such as heart disease, diabetes, kidney disease, and/or lung disease.10 These conditions disproportionately impact racial and ethnic minority populations.11

Chronic conditions in sexual minority men of color

Human Immunodeficiency Virus (HIV) is a communicable chronic disease that disproportionately affects African American and Hispanic/Latino sexual minority men. Globally, approximately 240 people are infected with HIV every hour, 12 and in the US, 1.2 million persons are living with HIV (PLWH).13 Published reports contend that half of sexual minority African American men and a quarter of Hispanic/Latino men will ultimately be diagnosed with HIV in their lifetime.14

Chronic conditions, such as cardiovascular disease and diabetes, affect PLWH more frequently than persons not living with HIV15 due to the effects of certain antiretroviral therapies, chronic inflammatory processes, and risk factors like tobacco use.16-18 The disproportionate burden of cardiovascular disease is highest in men of color, 19,20 and has been identified as the second most common cause of death in PLWH.19,21,22 Specifically, African Americans have the highest prevalence of hypertension, diabetes, and HIV, which are all preventable chronic illnesses.14,23 Moreover, type 2 diabetes (T2D) is most prevalent in ethnic and racial minority populations.24,25 It was the 7th leading cause of death in 2015.26 Approximately, 10-15% of PLWH have a comorbid diagnosis of T2D.27,28 Multiple biobehavioral factors influence the incidence of many of these chronic conditions.

Underutilized health care as a result of stigma, fear, and discrimination

In 2002, the Institute of Medicine report, “Unequal Treatment: Confronting Racial and Ethnic Disparities in Healthcare,” highlighted how preventable illnesses such as cardiovascular disease, diabetes, mental illness, and HIV were disproportionally high in ethnic minority populations when compared to non-minorities because of prejudgments and stereotyping from healthcare providers.29 Sexual minority men of color who are not openly self-identified as gay or bisexual, 30 may not want to be “outed” by accessing or receiving care at a LGBTQ community-based health center.31 This is due in part to historic structural and institutional racism that have been longstanding contributors to medical mistrust and perpetual health inequities. Moreover, past experiences with perceived stigma, and misconceptions about sexual activity have left residual fear and discrimination.32-36 The lack of acceptance and training on health issues salient to the LGBTQ community has affected health care access, utilization, and outcomes.31

Previous work has substantiated some root causes of HIV health disparities as being individual and structural-level factors.37-40 These factors include real and perceived racism, sexual orientation discrimination,41 healthcare provider discrimination and its resulting impact on health care utilization,37-39 and access to reliable health information. As these barriers persist, sexual minority men of color continue to live in silos and use their own social networks for support and guidance on how to best care for their health conditions. Because of this, sexual minority men of color living with HIV are at alarming risk of additional HIV-related chronic conditions. The deteriorating cumulative effects (“weathering”)42 of living with HIV, not having access to reliable health information, and possible development of HIV-related cardiovascular, and metabolic disease can be profoundly life threatening.

Understanding historic and present-day enablers of mistrust

We define mistrust as engendered beliefs by an individual that the intentions or motives of another person are misaligned with the priorities of the individual and perceived as harmful.43 In this paper, we refer to mistrust/distrust interchangeably.44 Mistrust can impact health promoting behaviors, healthcare utilization, adherence to prescribed treatments, and participation in research.43 Persons of color are fundamentally distrustful because of the extensive racism and discriminatory practices and experiences, beginning with the Transatlantic Slave Trade,45 to the Jim Crow Laws, and continuing with the longstanding ethical abuses in both human subjects and health care services46-50 that are still evident and have resulted in well-founded conspiracy beliefs.46,51 Mistrust continues to impact the lack of health equity and health outcomes of minority populations today. Health inequity is the systemic, potentially avoidable difference in health, or in the major socially determined influences on health between groups of people who have different relative positions in social hierarchies according to wealth, power or prestige.52

Additional enablers of mistrust in ethnic, racial, and sexual minority populations include microaggressive behaviors and political incivility. Microaggressions (derogatory, invalidating, oppressive snubs)53,54 in research and health care services have also contributed to substantiated feelings of mistrust.55 Political incivilities (rude, threatening, insulting commentary or behaviors based on ideological biases) have created mistrust within both Latino US citizens/legal residents and undocumented Latino communities.56 For example, in recent years, political incivilities towards Latinos have resulted in a negative impact on research participation and study retention.56 Fear of discrimination, and in some instances deportation, has led to challenges maintaining contact with and enrolling new research participants.56,57 Pernicious historical events have created a macrocosm of multi-level complex problems.

The consequences of mistrust on health status

The consequences of mistrust on health-related outcomes are harmful. Psychosocial stressors, such as perceived stigma and racism, have led to feelings of mistrust of the health care system and a decreased motivation towards health seeking behaviors.19,55,58 There is a growing amount of literature finding plausible associations between chronic psychosocial stress from discrimination and subsequent changes in physiological and behavioral responses to disease susceptibility and incidence.59,60

Sexual minority men of color encounter discrimination for being both a sexual minority and for being a person of color. Published reports suggest that sexual minority men of color who experienced incidents of discrimination did experience psychological distress.61,62 Findings from a meta-analysis of 105 studies suggested that racial/ethnic discrimination resulted in negative health outcomes.63 African Americans are at increased risk of hypertension due to chronic stress exposure.64 A multi-site cohort study of ethnic/racially diverse participants was the first to identify that experiences of discrimination were associated with T2D incidence.59 The chronic stress induced physiologic changes that resulted in hyperglycemia.59

In another study of persons living with T2D, findings suggested that discrimination-based chronic stress may lead to poor glycemic control and exacerbation of the disease.65 Moreover, adverse behavioral coping strategies, such as smoking and loss of control over eating, have been used by persons of color to mitigate the effects of discrimination-based chronic stress.59,66,67 Discrimination based on sexual orientation in minority men was also associated with HIV-risk taking behaviors.68

Overall, one can posit that constant exposure to discrimination increases the stress response, or allostatic load, on the cardiovascular and metabolic systems and thereby increases the risk for cardiovascular disease, diabetes incidence, and poor glycemic control.42,59,60,64,65 The effects of discrimination on health are deleterious and understandably lead to the cycle of decreased trust and lack of trustworthiness.

The role of trustworthiness and trust

Trustworthiness and trust are essential to enhancing participation in research and facilitating health care utilization.69 Trustworthiness precedes trust. Trustworthiness is the demonstration of integrity by an individual;69 and the belief that they will tell you the truth.70 It is a demonstrated assurance of protection from harm.69 Trustworthiness must be established before trust can be expected. Conversely, repeated violations of trustworthiness have resulted in hesitation and /or refusal by persons of color to trust human subjects and health care venues.71 A reliable blueprint to assure trustworthiness in less advantaged populations remains elusive in the presence of persisting inequities. Trust is established over time46 and is founded on transparency in communications and intentions.69 Trust is a continuous interaction that symbolizes verification of honesty, reliability, and confidence.69 All too often, trust is expected before trustworthiness can be established.

With the understanding of how the products of mistrust have adversely shaped health outcomes in sexual minority populations, new efforts must be directed at establishing trustworthiness and trust through non-traditional approaches. To increase accessibility of trusted forms of health-information and to facilitate health promoting behaviors, we contend that strategies utilizing eHealth technology are a good approach to address mistrust. Therefore, we introduce an innovative framework using eHealth technology to reach sexual minority populations of color, begin to establish trustworthiness, and build trust in health-related information and health promotion behaviors.

The salience of eHealth technology

Ubiquitous computing, or the availability and use of technology everywhere,72 is changing the paradigm of in-person health care and research interactions.73 According to findings from the 2018 Pew Research Center reports, 75% of African American and 77% of Latino adults own a smartphone.74 Smartphone ownership in US adults ages 18 through 64 is greater than 70%.74 In families with an annual household income of less than $30,000, almost 70% own a smartphone device.74 Smartphone functionalities (internet access, downloading content, video chatting, and gaming) enable users to interact with their phones much like they would a standard computer. As such, research and medicine have shifted towards utilizing eHealth technology to promote health behaviors and lifestyle changes.75,76

eHealth broadly refers to the advantageous use and access of online technologies to facilitate health education, information, and social support in order to prevent or self-manage chronic illness.77,78 eHealth is advantageous for hard-to-reach, marginalized populations, such as sexual minority men of color. It is a means of obtaining health-related information discreetly and privately to increase knowledge or enable health.

Virtual environments are one modality used in eHealth. Virtual environments are interactive virtual spaces where individuals can actively learn and practice health promoting behaviors and life skills that can be directly translated to the real world,79 and they have been successful in motivating and engaging users with points, badges, rewards, and other incentives.76

Virtual environments have been used in research to intervene with patients for self-management of diabetes,79-81 smoking cessation,82 HIV medication adherence,83 and prevention of HIV risk behaviors.84,85 However, a promising and innovative application is the use of eHealth to decrease medical mistrust and establish trustworthiness and trust among sexual minority men of color. We present a stepwise ascending framework to broaden understanding of how utilizing eHealth technology can increase trustworthiness in order to establish trust.

A proposed stepwise multi-construct framework towards trustworthiness and trust using eHealth technology

Two types of eHealth technologies we will discuss are virtual environments and avatar-led eHealth videos. Virtual environments are 3-demensional, computer-generated interactive spaces.81 Users interact with other persons online, usually in the form of an avatar (computer-generated representation of a human).81 Avatar-led eHealth videos are interactive vignettes that utilize avatars to convey storylines on sensitive topics.86 Both types of eHealth technologies provide many benefits to users and can promote engagement without the stigma associated with face-to-face encounters. The benefits of utilizing eHealth technologies, such as virtual environments, include anonymity, co-presence, self-disclosure, and social support. Adoption and usage of eHealth technologies are expedient and promising given the broad appeal to varying age groups, backgrounds, and levels of technological experience.

Anonymity is a primary reason for the success of virtual environments in attracting users for participation.73 Anonymity refers to the act of remaining electronically unidentifiable and un-linkable among a group of persons with similar attributes to escape social and societal convention or persecution.87,88 Anonymity can decrease barriers to engagement in health-seeking behaviors,31 increase access to sources of reliable health information, and support health enhancing behaviors that can be transferred to real-world situations.80 For example, fear of discrimination and being “outed” as a sexual minority or for living with chronic illness is plausibly lessened from anonymity provided through a virtual environment.80

Virtual environments can enable the feeling of being virtually present (presence) or virtually co-present (co-presence) with others through capabilities like synchronous voice communication and avatar representation of self.89 Co-presence in virtual environments is associated with higher levels of engagement and enjoyment in learning, as opposed to solely playing against a computer.90 Anonymity and co-presence foster self-disclosure. Self-disclosure is the sharing of personal information about oneself 91,92 and is an antecedent to achieving close relationships and supportive interactions with others.90

A significant end-product of anonymity, co-presence, and self-disclosure is social support. Social support is attained when persons of similar circumstances share information and resources with the intent to increase a sense of well-being. A large body of evidence suggests that meaningful relationships or social supports are associated with lower rates of morbidity and mortality.93-95 In the case of a virtual environment, users interact anonymously with each other. They engage in virtual, but often synchronous, voice-conversation, and because they are similar in some aspect, they are able to relate to each other’s social, health-related, or cultural concerns.

Eysenbach proposed additional meanings for the “e” in eHealth to advance the term beyond a general definition of the usage of the internet to facilitate health-related knowledge, support, and management.78 A few characterizations of the additional “e’s” include enabling, easy-to-use, entertaining, encouragement, ethics, empowerment, extending, education, and equity.78 Table 1 illustrates our ascending framework constructs, their relationship to eHealth78 characteristics and its application to trust.

Table 1.

Ascending Framework Constructs – Relationship to eHealth Characteristics and Application to Trustworthiness and Trust.

| Framework Construct | eHealth Characteristic77 | Application to Trustworthiness and Trust |

|---|---|---|

| Adoption and Usage | Enabling | Using technology to communicate on a common platform with others |

| Easy-to-use | Reducing barriers to eHealth by creating an interface that requires minimal cognitive effort | |

| Entertaining | Making eHealth fun and enjoyable | |

| Anonymity | Encouragement | Feeling secure about interacting with others virtually |

| Ethics | Protecting one’s rights to privacy | |

| Co-presence | Empowerment | A feeling of liberation to be virtually among socially or culturally similar persons |

| Self-disclosure | Extending | Having a sense of security in the virtual environment to allow private conversations to occur and meaningful relationships to grow |

| Social Support | Education | Accessibility to likeminded peers to foster growth, knowledge, and health promoting behaviors |

| Equity | Having full access to professional services, peers, and information that can be used to better one’s health |

We have adapted aspects of the definitions to apply them in our framework as it relates to the eHealth virtual environment. Enabling refers to the exchange of information or communication in a standardized way.78 Easy-to-use refers to technology use that is free of effort.96 Entertaining refers to interface design intended to spur gratification and enjoyment.97

Encouragement refers to embarking on a new relationship free of social or societal convention.78,88 Ethics refer to the privacy issues inherent to the usage of eHealth.78 Empowerment refers to the accessibility of health information and informed choice.78

Extending refers to the limitless geographical boundaries and meaningful relationships that are built in eHealth.78 Education refers to the tailored health information and education tools that are available.78 Equity refers to the availability of professional resources, tools, and health information that are not traditionally ubiquitous in marginalized populations.78

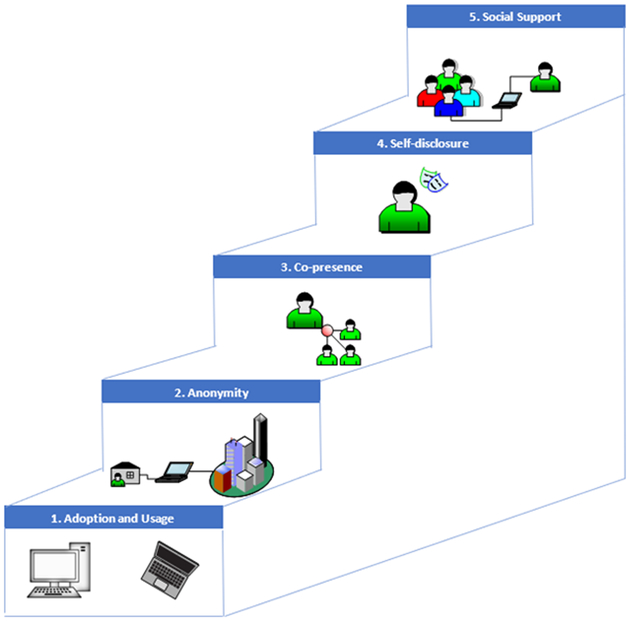

Here, we provide two research exemplars of how our framework towards trustworthiness and trust can be used in the context of two distinct eHealth intervention studies (Figure 1). The two studies reported below are meant to illustrate how our framework constructs of adoption and usage, anonymity, presence/copresence, self-disclosure, and social support can be used in e-Health interventions to establish trustworthiness and build trust in sexual minority populations living with chronic illness.

Figure 1.

Ascending model of how eHealth can enable stepwise progression towards trustworthiness and trust in a virtual environment.

eHealth Exemplar 1: Virtual environment for diabetes self-management and support

Trustworthiness in health promoting behaviors

The goal of the Diabetes LIVE (Learning In Virtual Environments) intervention was to provide a simulated community for participants living with diabetes to self-manage their condition. This included: accessing resources, virtually engaging with peers, and attending synchronous sessions with a diabetes educator or a health professional who could address their questions or concerns.81 Preliminary work conducted in a one group feasibility pilot study (SLIDES – Second Life Impacts Diabetes Education and Support) informed the development of LIVE and demonstrated that among a small pilot group of patients with diabetes, perceived support increased, and some participants formed longer term supportive relationships with each other and the health professionals.80,89 The analysis of the qualitative data collected in SLIDES89 highlights the potential value of virtual environments in addressing trust among those living with chronic conditions, including diabetes, heart disease, and HIV. Lewinski found that the ties between many participants evolved and became stronger (i.e., closer) and that the personal nature of the narratives shared regarding living with diabetes also increased over time.89 These indicate a high level of trust of peers and providers in the virtual environment by participants. In exemplar one, a virtual environment for chronic illness self-management supports our innovative ascending framework towards trust as follows:

Adoption/usage - In SLIDES, of the 20 participants, 14 came into the site on a regular basis (i.e., at least weekly) for at least the first 3 months; and a subgroup of 6 maintained participation in the site as a group for a full 6 months.80 Self-report perceived ease of use and usefulness were rated as moderate to high by participants at baseline and remained similar over time at 3 and 6 months as determined by validated questionnaires.80 This demonstrates that most of the participants used and maintained usage of the VE over time.

Anonymity – Participants in both SLIDES and LIVE studies used pseudonyms when logged into the sites. They could modify the appearance of their avatars in terms of body shape and size, hair color/style, and clothing. The VE could be accessed in a private setting without disclosing the identity of the user.

Presence/co-presence – Presence and co-presence were rated as moderate to high by participants in SLIDES using validated self-report questionnaires. Participants felt a sense of truly being there with others, based on discussions about avatar appearance and their self-representation among the group.

Self-disclosure – Some participants appeared to bond with each other based on their consistent attendance at weekly classes and support sessions. Conversations increased over time in terms of the depth and personal information89 Statements by participants to study team members directly indicated that they did not want the intervention study to end.80

Social support – Support for diabetes self-management increased significantly over the 6 months of participation in SLIDES (mean score 4.61 to 6.35 over 6 months on a scale of 1-7; p=0.002).57 Supportive relationships were also noted in the qualitative data findings from the interactions in SLIDES. This will continue to inform the use of virtual environments such as LIVE among those living with other chronic conditions.

eHealth Exemplar 2: Avatar-led eHealth videos to increase knowledge of PEP and PrEP for HIV prophylaxis

Trustworthiness in reliable sources of information

The goal of the avatar-led eHealth video study was to increase awareness, knowledge, and uptake of pre-exposure (PrEP) and post-exposure (PEP) HIV prophylaxis.86 The avatar-led eHealth videos were created as a way to engage individuals in an accessible research intervention while decreasing the stigma associated with sensitive topics, such as HIV. The avatar-led eHealth video consisted of two parts. In Part 1, the storyline described two friends in the emergency department. One of the friends was potentially exposed to HIV.86 During this scene, the emergency department physician discusses the benefits and rationale for initiating PEP, based on the risk of HIV exposure. At the end of the scene, the character is returning for follow-up at the hospital where her PEP treatment was started 28 days ago.

In Part 2, the storyline addressed two different friends, one of whom is discussing concerns about the lack of monogamy in the relationship.86 The character is encouraged to discuss these concerns with a clinician. In the following scene, the clinician explains how PrEP can be used in non-monogamous relationships and in relationships where one of the partners is living with HIV. The clinician goes on to describe other aspects to consider when starting PrEP, such as routine laboratory testing, side effects, and cost. This information is empowering for the character and enables an informed decision to be made.

Findings from the study suggested that only 18% of participants had heard of PrEP and 22% had heard of PEP prior to viewing the avatar-led eHealth video.86 This was in a sample of 91 African American women with a reported annual household income of greater or equal to 50 thousand dollars and more than half having completed a college degree. This is notable because it highlights how eHealth interventions aimed at PrEP and PEP have not been accessible in some minority populations despite socioeconomic status.86

In exemplar two, the avatar-led eHealth video supports our innovative ascending framework towards trust as follows:

Adoption/usage – The avatar-led eHealth video was accessible online and took a total of 9 minutes to complete.86

Anonymity – The avatar-led eHealth video could be accessed in a private setting of choice without disclosing the identity of the viewer.

Presence – The avatar-led eHealth video was very engaging due to inclusion of characters that were phenotypically relatable. Because the storylines were culturally tailored to relevant issues in the community, viewers could identify with the protagonist, thus creating an experience of presence.86

Self-disclosure – Greater than half of the participants reported that they would actively seek out PrEP and PEP if ever necessary. This demonstrates that the avatar-led eHealth video could reduce barriers to self-disclosure of the need for PREP and PEP with clinicians and peers.86

Social support – Findings from this study suggested that participants would recommend the avatar-led eHealth video to their peers. This enables social support as peers rely on each other to navigate ambiguous situations.86

Discussion

The purpose of this paper was to present an innovative framework to support the use of eHealth technologies, such as virtual environments and avatar-led eHealth videos, to reach sexual minority populations of color to establish trustworthiness and build trust. We provided a detailed description of how sexual minority men of color are at high risk of chronic conditions. We highlighted this population’s burdensome predisposition to chronic illness via discrimination-based chronic stress. We then identified linkages between biobehavioral predisposition and discrimination-based predisposition. Finally, we presented two examples of how our framework towards trustworthiness and trust can be used in the context of two distinct eHealth intervention studies.

The concept of establishing trustworthiness and trust using eHealth has tremendous implications for bridging relational divides between researchers, patients, and clinicians. As researchers and clinicians, we need to open ourselves to “check and clarification” from our patients and participants with regard to our communications and intentions. Using language or vocal tone that is from stereotyped modern vernacular is a form of microaggression98,99 - even with the best of intentions. Trustworthiness and trust are not established because of the ability to “relate” in stereotyped language, vocal tone, or popular culture. Rather, it is established and built on authenticity, respectful interaction, clear, honest, and thorough explanations, and consistent provision of the power of choice on behalf of the participant or patient.31,56 Trust needs to be earned as participants and patients determine our trustworthiness and then take a risk and give us their trust. Lars Hertzberg stated, “Trust is always for something we can rightfully demand from others: misplaced trust, accordingly, is not a shortcoming on the part of the trustful person, but of the person in whom the trust was placed.”100

In order to move forward, while respecting the fact that we are not trusted until we establish trustworthiness, we must adjust the way in which we interact, recruit, conduct research, and provide care. As clinicians, we should consistently ask clarifying questions about a patient’s name and gender preference and not assume sexual promiscuity or HIV serostatus based on sexual orientation.31 When conducting research, relationship building is essential. This can be established by demonstrating cultural competence, fostering confidentiality with sensitive information, and assuring privacy during data collection encounters.31 It is also vital to lay the foundation for trust and rapport through the use of community health workers,56 faith-based organizations,69 and research or health care staff who resemble the community being recruited or for whom care is given; as these entities have presumably proven themselves trustworthy.69 Moreover, appropriate remuneration for study participation should be offered since participation may take place during work hours or family time.56,69

eHealth may provide platforms to reach more diverse populations for health interventions. Persons residing in the US of varying income levels, age ranges, and race/ethnicities own a smartphone. This speaks to the growth in accessibility of technology and the progressive ubiquity of eHealth as a plausible strategy to establishing trustworthiness in hard-to-reach populations, such as sexual minority men of color. As such, researchers must engage participants in contributing to eHealth interventions in terms of their perceived needs since this is necessary for trustworthy interventions.

Equitable electronic access to credible sources of health-related information is a step in the right direction to addressing health disparities in the digital era. However, research and health care should not solely rely on remote technological interactions. Personal face-to-face interaction, even in the digital era, will always be the cornerstone that differentiates being trustworthy from that of having a sustainable trusting relationship with patients and participants.

Lastly, research findings should be disseminated at timely intervals to the study participants. Participants want to know how their contribution has impacted new knowledge or practice. If we take (collect data), we must also give back (disseminate to the community). This is critical in an effort to move from trustworthiness to a place where we are extended the privilege of trust.

Conclusion:

eHealth technology can be leveraged to dismantle some traditional elements of medical mistrust and help translate trustworthiness into trust. Elements of eHealth technology can promote engagement through adoption and use, anonymity, co-presence, and social support in populations who have historically experienced stigma and mistrust. Changing the paradigm of medical mistrust is vital and plausible.

Contributor Information

S. Raquel Ramos, New York University, Rory Meyers College of Nursing, New York, NY. USA.

Rueben Warren, Tuskegee University, National Center for Bioethics in Research and Health Care, Tuskegee, AL. USA

Michele Shedlin, New York University, Rory Meyers College of Nursing, New York, NY. USA.

Gail Melkus, New York University, Rory Meyers College of Nursing, New York, NY. USA.

Trace Kershaw, Yale University, School of Public Health, New Haven, CT. USA.

Allison Vorderstrasse, New York University, Rory Meyers College of Nursing, New York, NY. USA.

References

- 1.Schmidt H Chronic disease prevention and health promotion In: Public Health Ethics: Cases Spanning the Globe. Springer; 2016:137–176. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Organization WH. Noncommunicable diseases country profiles 2011. 2011.

- 3.Organization WH. Ten Years in Public Health, 2007–2017: Report by Dr Margaret Chan, Director-General, World Health Organization; 2017. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Organization WH. Noncommunicable diseases: progress monitor 2017. 2017.

- 5.Health UDo, Services H. Multiple chronic conditions—a strategic framework: optimum health and quality of life for individuals with multiple chronic conditions. Washington, DC: US Department of Health and Human Services; 2010;2. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Benjamin EJ, Blaha MJ, Chiuve SE, et al. Heart disease and stroke statistics—2017 update: a report from the American Heart Association. Circulation. 2017;135(10):e146–e603. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Leung MYM, Carlsson NP, Colditz GA, Chang S-H. The Burden of Obesity on Diabetes in the United States: Medical Expenditure Panel Survey, 2008 to 2012. Value in Health. 2017;20(1):77–84. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.CDC. Leading causes of death and numbers of deaths, by sex, race, and Hispanic origin: United States, 1980 and 2014 (Table 19). Health, United States; 2015. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Health UDo, Services H. The health consequences of smoking—50 years of progress: a report of the Surgeon General. Atlanta, GA: US Department of Health and Human Services, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, National Center for Chronic Disease Prevention and Health Promotion, Office on Smoking and Health; 2014;17. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Buttorff C, Ruder T, Bauman M. Multiple Chronic Conditions in the United States. 2017.

- 11.Heckler M Report of the Secretary’s task force on Black & minority health. 1985. [PubMed]

- 12.UNAIDS fact sheet 2017.

- 13.CDC. HIV Surveillance Report, 2015;. 2016;27. [Google Scholar]

- 14.CDC. Half of black gay men and a quarter of Latino gay men projected to be diagnosed within their lifetime. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, Atlanta, GA: 2016:2016. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Triant VA. Cardiovascular disease and HIV infection. Current HIV/AIDS Reports. 2013;10(3):199–206. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Freiberg MS, So-Armah K. HIV and cardiovascular disease: we need a mechanism, and we need a plan. In: Am Heart Assoc; 2016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Crothers K Chronic obstructive pulmonary disease in patients who have HIV infection. Clinics in chest medicine. 2007;28(3):575–587. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.De Wit S, Sabin CA, Weber R, et al. Incidence and risk factors for new-onset diabetes in HIV-infected patients: the Data Collection on Adverse Events of Anti-HIV Drugs (D: A: D) study. Diabetes care. 2008;31(6):1224–1229. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.CDC. A closer look at African American men and high blood pressure control: A review of psychosocial factors and systems-level interventions. Atlanta: US Department of Health and Human Services; 2010. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Balfour PC Jr, Ruiz JM, Talavera GA, Allison MA, Rodriguez CJ. Cardiovascular disease in Hispanics/Latinos in the United States. Journal of Latina/o psychology. 2016;4(2):98. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Oliveria SA, Chen RS, McCarthy BD, Davis CC, Hill MN. Hypertension knowledge, awareness, and attitudes in a hypertensive population. Journal of general internal medicine. 2005;20(3):219–225. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Sackoff JE, Hanna DB, Pfeiffer MR, Torian LV. Causes of death among persons with AIDS in the era of highly active antiretroviral therapy: New York City. Annals of internal medicine. 2006;145(6):397–406. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.CDC. Vital signs. In. African American health creating equal opportunities for health 2017. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Cheng C-Y, Reich D, Haiman CA, et al. African ancestry and its correlation to type 2 diabetes in African Americans: a genetic admixture analysis in three US population cohorts. PloS one. 2012;7(3):e32840. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Chukwueke I, Cordero-MacIntyre Z. Overview of type 2 diabetes in Hispanic Americans. International journal of body composition research. 2010;8(Supp):77. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.CDC. National diabetes statistics report, 2017. Atlanta, GA: Centers for Disease Control and Prevention; 2017. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Zuniga JA, Bose E, Park J, Lapiz-Bluhm MD, García AA. Diabetes Changes Symptoms Cluster Patterns in Persons Living With HIV. Journal of the Association of Nurses in AIDS Care. 2017;28(6):888–896. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Hernandez-Romieu AC, Garg S, Rosenberg ES, Thompson-Paul AM, Skarbinski J. Is diabetes prevalence higher among HIV-infected individuals compared with the general population? Evidence from MMP and NHANES 2009–2010. BMJ Open Diabetes Research and Care. 2017;5(1):e000304. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Smedley B, Stith A, Nelson A. Unequal treatment: What healthcare providers need to know about racial and ethnic disparities in healthcare. Washington, DC: National Academy Press; Retrieved February 2002;12:2004. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Rosario M, Schrimshaw EW, Hunter J. Different patterns of sexual identity development over time: Implications for the psychological adjustment of lesbian, gay, and bisexual youths. Journal of sex research. 2011;48(1):3–15. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Graham R, Berkowitz B, Blum R, et al. The health of lesbian, gay, bisexual, and transgender people: Building a foundation for better understanding. Washington, DC: Institute of Medicine; 2011. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Boekeloo BO, Schamus LA, Cheng TL, Simmens SJ. Young adolescents’ comfort with discussion about sexual problems with their physician. Archives of pediatrics & adolescent medicine. 1996;150(11):1146–1152. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Dowshen N, Binns HJ, Garofalo R. Experiences of HIV-related stigma among young men who have sex with men. AIDS Patient Care and STDs. 2009;23(5):371–376. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Emlet CA. “You’re awfully old to have this disease”: Experiences of stigma and ageism in adults 50 years and older living with HIV/AIDS. The Gerontologist. 2006;46(6):781–790. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Emlet CA. A comparison of HIV stigma and disclosure patterns between older and younger adults living with HIV/AIDS. AIDS Patient Care & STDs. 2006;20(5):350–358. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Estem KS, Catania J, Klausner JD. HIV Self-Testing: a Review of Current Implementation and Fidelity. Current HIV/AIDS Reports. 2016;13(2):107–115. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Nelson LE, Wilton L, Moineddin R, et al. Economic, legal, and social hardships associated with HIV risk among black men who have sex with men in six US cities. Journal of Urban Health. 2016;93(1):170–188. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Magnus M, Franks J, Griffith MS, Arnold MP, Goodman MK, Wheeler DP. Engaging, recruiting, and retaining black men who have sex with men in research studies: don’t underestimate the importance of staffing—lessons learned from HPTN 061, the BROTHERS study. Journal of public health management and practice: JPHMP. 2014;20(6):E1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Irvin R, Wilton L, Scott H, et al. A study of perceived racial discrimination in Black men who have sex with men (MSM) and its association with healthcare utilization and HIV testing. AIDS and Behavior. 2014;18(7):1272–1278. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Koblin BA, Mayer KH, Eshleman SH, et al. Correlates of HIV acquisition in a cohort of Black men who have sex with men in the United States: HIV prevention trials network (HPTN) 061. PloS one. 2013;8(7):e70413. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Halkitis P. Discrimination and homophobia fuel the HIV epidemic in gay and bisexual men. Director. 2012;202:6176. [Google Scholar]

- 42.Geronimus AT, Hicken M, Keene D, Bound J. “Weathering” and age patterns of allostatic load scores among blacks and whites in the United States. American journal of public health. 2006;96(5):826–833. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Hoyt MA, Rubin LR, Nemeroff CJ, Lee J, Huebner DM, Proeschold-Bell RJ. HIV/AIDS-related institutional mistrust among multiethnic men who have sex with men: Effects on HIV testing and risk behaviors. Health Psychology. 2012;31(3):269. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Smirnoff M, Wilets I, Ragin D, et al. A paradigm for understanding trust and mistrust in medical research: The Community VOICES study. AJOB empirical bioethics. 2018;9(1):39–47. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Nunn N, Wantchekon L. The slave trade and the origins of mistrust in Africa. American Economic Review. 2011;101(7):3221–3252. [Google Scholar]

- 46.Ball K, Lawson W, Alim T. Medical mistrust, conspiracy beliefs & HIV related behavior among African Americans. Journal of Psychological and Behavioral Science. 2013;1(1):1–7. [Google Scholar]

- 47.Corbie-Smith G, Thomas SB, Williams MV, Moody-Ayers S. Attitudes and beliefs of African Americans toward participation in medical research. Journal of general internal medicine. 1999;14(9):537–546. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Shavers-Hornaday VL, Lynch CF, Burmeister LF, Torner JC. Why are African Americans under-represented in medical research studies? Impediments to participation. Ethnicity & health. 1997;2(1-2):31–45. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Dula A African American suspicion of the healthcare system is justified: what do we do about it? Cambridge quarterly of healthcare ethics. 1994;3(3):347–357. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Boulware LE, Cooper LA, Ratner LE, LaVeist TA, Powe NR. Race and trust in the health care system. Public health reports. 2016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Jaiswal JL. A qualitative study of urban people of color living with human immunodeficiency virus: challenges related to retention in care, antiretroviral therapy acceptance, and “conspiracy beliefs”. 2017.

- 52.Braveman P Health disparities and health equity: concepts and measurement. Annu Rev Public Health. 2006;27:167–194. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Sue DW. Microaggressions in everyday life: Race, gender, and sexual orientation. John Wiley & Sons; 2010. [Google Scholar]

- 54.Sue DW, Capodilupo CM, Torino GC, et al. Racial microaggressions in everyday life: Implications for clinical practice. American psychologist. 2007;62(4):271. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Hall JM, Fields B. “It’s Killing Us!” Narratives of black adults about microaggression experiences and related health stress. Global qualitative nursing research. 2015;2:2333393615591569. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Sage R, Benavides-Vaello S, Flores E, LaValley S, Martyak P. Strategies for conducting health research with Latinos during times of political incivility. Nursing Open. 2018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.García AA, Zuñiga JA, Lagon C. A personal touch: The most important strategy for recruiting Latino research participants. Journal of Transcultural Nursing. 2017;28(4):342–347. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Orom H, Sharma C, Homish GG, Underwood W, Homish DL. Racial discrimination and stigma consciousness are associated with higher blood pressure and hypertension in minority men. Journal of racial and ethnic health disparities. 2017;4(5):819–826. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Whitaker KM, Everson-Rose SA, Pankow JS, et al. Experiences of discrimination and incident type 2 diabetes mellitus: The Multi-Ethnic Study of Atherosclerosis (MESA). American journal of epidemiology. 2017;186(4):445–455. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.McEwen BS. Protective and damaging effects of stress mediators. New England journal of medicine. 1998;338(3):171–179. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Choi K-H, Paul J, Ayala G, Boylan R, Gregorich SE. Experiences of discrimination and their impact on the mental health among African American, Asian and Pacific Islander, and Latino men who have sex with men. American Journal of Public Health. 2013;103(5):868–874. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Chae DH, Krieger N, Bennett GG, Lindsey JC, Stoddard AM, Barbeau EM. Implications of discrimination based on sexuality, gender, and race/ethnicity for psychological distress among working-class sexual minorities: The United for Health Study, 2003–2004. International Journal of Health Services. 2010;40(4):589–608. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Carter RT, Lau MY, Johnson V, Kirkinis K. Racial discrimination and health outcomes among racial/ethnic minorities: A meta-analytic review. Journal of Multicultural Counseling and Development. 2017;45(4):232–259. [Google Scholar]

- 64.Williams DR, Neighbors H. Racism, discrimination and hypertension: evidence and needed research. Ethn Dis. 2001;11(4):800–816. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.LeBrón AM, Spencer M, Kieffer E, Sinco B, Palmisano G. Racial/ethnic discrimination and diabetes-related outcomes among Latinos with type 2 diabetes. Journal of immigrant and minority health. 2018:1–10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Todorova IL, Falcón LM, Lincoln AK, Price LL. Perceived discrimination, psychological distress and health. Sociology of health & illness. 2010;32(6):843–861. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Kelly NR, Smith TM, Hall GC, et al. Perceptions of general and postpresidential election discrimination are associated with loss of control eating among racially/ethnically diverse young men. International Journal of Eating Disorders. 2018;51(1):28–38. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Frye V, Nandi V, Egan J, et al. Sexual orientation-and race-based discrimination and sexual HIV risk behavior among urban MSM. AIDS and Behavior. 2015;19(2):257–269. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Warren RC, Shedlin MG., Alema-Mensah E. Clinical trials: African American leadership interviews In. National Center For Bioethics in Research and Health Care Tuskegee University;2017. [Google Scholar]

- 70.Spence PR, Lachlan KA, Westerman D, Spates SA. Where the gates matter less: Ethnicity and perceived source credibility in social media health messages. Howard Journal of Communications. 2013;24(1):1–16. [Google Scholar]

- 71.Katz RV, Warren RC. The search for the legacy of the USPHS syphilis study at Tuskegee. Lexington Books; 2011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Heinrichs JH, Lim JS, Lim KS. Influence of social networking site and user access method on social media evaluation. Journal of Consumer Behaviour. 2011;10(6):347–355. [Google Scholar]

- 73.Watson AJ, Grant RW, Bello H, Hoch DB. Brave new worlds: How virtual environments can augment traditional care in the management of diabetes. Journal of diabetes science and technology. 2008;2(4):697–702. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Center PR. Mobile fact sheet. Pew Research Center: Internet, Science & Tech. 2017.

- 75.Murray E, Burns J, See Tai S, Lai R, Nazareth I. Interactive Health Communication Applications for people with chronic disease. The Cochrane Library. 2005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.AlMarshedi A, Wills G, Ranchhod A. Gamifying self-management of chronic illnesses: a mixed-methods study. JMIR serious games. 2016;4(2). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Macdonald GG, Townsend AF, Adam P, et al. eHealth technologies, multimorbidity, and the office visit: qualitative interview study on the perspectives of physicians and nurses. Journal of medical Internet research. 2018;20(1). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Eysenbach G What is e-health?(2001). Journal of Medical Internet Research. 2001;3(2):e20. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Johnson C, Feenan K, Setliff G, et al. Building a virtual environment for diabetes self-management education and support. International Journal of Virtual Communities and Social Networking (IJVCSN). 2013;5(3):68–80. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Johnson C, Feinglos M, Pereira K, et al. Feasibility and preliminary effects of a virtual environment for adults with type 2 diabetes: pilot study. JMIR research protocols. 2014;3(2). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Vorderstrasse AA, Melkus G, Pan W, Lewinski AA, Johnson CM. Diabetes LIVE (Learning in Virtual Environments): Testing the Efficacy of Self-Management Training and Support in Virtual Environments (RCT Protocol). Nursing research. 2015;64(6):485. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Woodruff SI, Edwards CC, Conway TL, Elliott SP. Pilot test of an Internet virtual world chat room for rural teen smokers. Journal of Adolescent Health. 2001;29(4):239–243. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Côté J, Godin G, Guéhéneuc Y-G, et al. Evaluation of a real-time virtual intervention to empower persons living with HIV to use therapy self-management: study protocol for an online randomized controlled trial. Trials. 2012;13(1):187. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Rhodes SD. Hookups or health promotion? An exploratory study of a chat room-based HIV prevention intervention for men who have sex with men. AIDS Education and Prevention. 2004;16(4):315–327. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Christensen JL, Miller LC, Appleby PR, et al. Reducing shame in a game that predicts HIV risk reduction for young adult men who have sex with men: a randomized trial delivered nationally over the web. Journal of the International AIDS Society. 2013;16:18716. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Bond K, Ramos SR. Utilization of an animated eHealth video to increase knowledge of HIV post- and pre-exposure proplylaxis among African American Women. JMIR Research Protocols (forthcoming/in press). 2018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Pfitzmann A, Köhntopp M. Anonymity, unobservability, and pseudonymity—a proposal for terminology. Paper presented at: Designing privacy enhancing technologies 2001. [Google Scholar]

- 88.Wang Z Anonymity Effects and Implications in the Virtual Environment: From Crowd to Computer-Mediated Communication. Social Networking. 2017;7(01):45. [Google Scholar]

- 89.Lewinski AA, Anderson RA, Vorderstrasse AA, Fisher EB, Pan W, Johnson CM. Type 2 Diabetes Education and Support in a Virtual Environment: A Secondary Analysis of Synchronously Exchanged Social Interaction and Support. Journal of medical Internet research. 2018;20(2). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.De Kort YA, IJsselsteijn WA, Poels K. Digital games as social presence technology: Development of the Social Presence in Gaming Questionnaire (SPGQ). Proceedings of PRESENCE. 2007;195203. [Google Scholar]

- 91.Hollenbaugh EE, Everett MK. The effects of anonymity on self-disclosure in blogs: An application of the online disinhibition effect. Journal of Computer-Mediated Communication. 2013;18(3):283–302. [Google Scholar]

- 92.Altman I, Taylor DA. Social penetration: The development of interpersonal relationships. Holt, Rinehart & Winston; 1973. [Google Scholar]

- 93.Feeney BC, Collins NL. A new look at social support: A theoretical perspective on thriving through relationships. Personality and Social Psychology Review. 2015;19(2):113–147. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94.Holt-Lunstad J, Smith TB. Social relationships and mortality. Social and Personality Psychology Compass. 2012;6(1):41–53. [Google Scholar]

- 95.Uchino BN. Social support and health: a review of physiological processes potentially underlying links to disease outcomes. Journal of behavioral medicine. 2006;29(4):377–387. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 96.Davis FD. Perceived usefulness, perceived ease of use, and user acceptance of information technology. MIS quarterly. 1989:319–340. [Google Scholar]

- 97.Khalil GE, Wang H, Calabro KS, Mitra N, Shegog R, Prokhorov AV. From the Experience of Interactivity and Entertainment to Lower Intention to Smoke: A Randomized Controlled Trial and Path Analysis of a Web-Based Smoking Prevention Program for Adolescents. Journal of medical Internet research. 2017;19(2). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 98.Hill JH. The everyday language of white racism. John Wiley & Sons; 2009. [Google Scholar]

- 99.Eberhardt M, Freeman K. ‘First things first, I’m the realest’: Linguistic appropriation, white privilege, and the hip-hop persona of Iggy Azalea. Journal of Sociolinguistics. 2015;19(3):303–327. [Google Scholar]

- 100.Hertzberg L On the attitude of trust. Inquiry. 1988;31(3):307–322. [Google Scholar]