Abstract

Takotsubo cardiomyopathy is a syndrome characterized by transient left ventricular systolic and diastolic dysfunction, similar to an acute myocardial infarction but in the absence of significant obstructive epicardial coronary artery disease. This disease manifests predominantly in postmenopausal women in the presence of stressful triggers. We present a case of reverse takotsubo cardiomyopathy involving apical sparing, resulting from an iatrogenic overdose of epinephrine in a young man who was treated for anaphylaxis and angioedema.

Keywords: Anaphylaxis, catecholamine excess, takotsubo cardiomyopathy

Takotsubo cardiomyopathy (TC) is characterized by transient myocardial dysfunction and myocardial enzyme elevation similar to an acute myocardial infarction but in the absence of significant obstructive epicardial coronary artery disease. This disease predominantly affects postmenopausal women in the presence of triggers such as severe physical or emotional stress, natural disasters, and acute medical illnesses. A commonly accepted hypothesis is that an intense psychological or physical stress results in a catecholamine surge that can adversely affect myocardial contractility, leading to transient myocardial dysfunction.1–4 TC is usually characterized by transient apical akinesis or hypokinesis (apical ballooning) and basal hyperkinesis that resolves spontaneously within a few days or weeks. Variants of TC have been described based on the regions of the ventricular wall motion abnormality. Reverse TC is a rare variant usually seen in young patients, which presents with mid to basal ballooning instead of the classical apical ballooning.5 We present a rare case of iatrogenic epinephrine-induced reverse TC in a young man who presented with anaphylaxis triggered by a spider bite.

CASE PRESENTATION

A 27-year-old man presented to the emergency room with worsening dyspnea, chest pressure, and a pruritic erythematous rash extending from his axilla to anterior abdominal wall after a brown recluse spider bite. Vital signs on admission revealed a blood pressure of 130/80 mm Hg, respiratory rate of 20 breaths/min, and heart rate of 106 beats/min. He had dyspnea and mild to moderate respiratory distress associated with wheezing and an oxygen saturation of 93% on room air. He was treated for anaphylaxis and subacute angioedema. After partial clinical response to intravenous diphenhydramine and methylprednisolone, an emergent order for intramuscular epinephrine, dose 0.3 mg (1:1000 solution), was placed. The formulation, however, was inadvertently administered intravenously by the nurse. The patient developed intractable cough, chest tightness, pallor, and frank hemoptysis resulting in acute hypoxemic respiratory failure (Figure 1) and required emergent mechanical ventilator support. The endotracheal tube aspirate was dark bloody-red tinged, and the chest radiograph showed bilateral dense infiltrates and early cephalization.

Figure 1.

Patient experienced frank hemoptysis after epinephrine administration. Specimen represents sanguinous bronchoalveolar lavage.

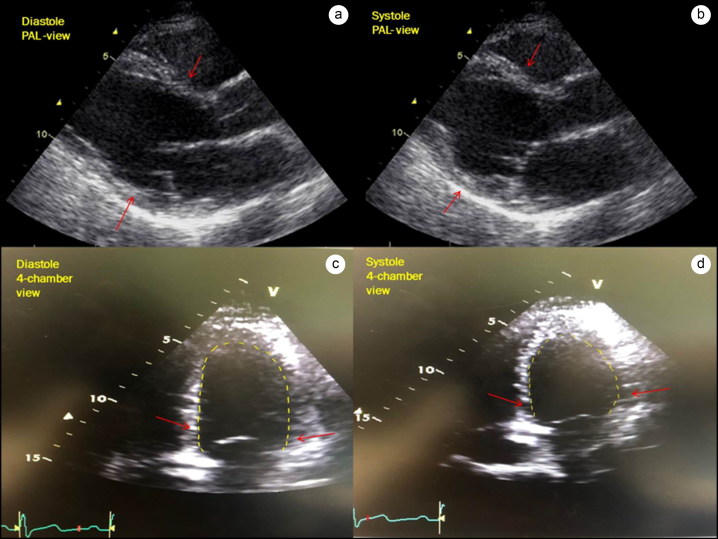

A repeat examination was remarkable for tachycardia (heart rate 116 beats/min), hypotension (blood pressure 80/46 mm Hg), diaphoresis, and tachypnea (respiratory rate 21 breaths/min). Central venous pressure was 10 mm Hg, and mean arterial pressure was 68 mm Hg. Laboratory results showed elevated aspartate and alanine aminotransferases and a normal coagulation profile. The patient’s serial troponin levels increased from <0.01 ng/L to 4.04 ng/L in 5 hours. A transthoracic echocardiogram showed severe left ventricular systolic dysfunction (ejection fraction of 20%) and mid to basal ballooning with preserved apical contractility (Figure 2). Antithrombotic therapy was not administered due to ongoing hemoptysis and thus supportive therapy along with steroids was continued. Unenhanced computerized tomography of the chest, abdomen, and pelvis was remarkable for bilateral ground-glass opacities in the upper pulmonary lobes and dense opacities in the lower pulmonary lobes.

Figure 2.

Left ventricular echocardiogram. (a, b) Parasternal long-axis view in diastole and systole. Arrows point toward mid to basal hypokinesis in systole. (c, d) Apical four-chamber views showing diastole and systole. Arrows point toward the basal and mid-left ventricular hypokinesis while apical contractility is preserved.

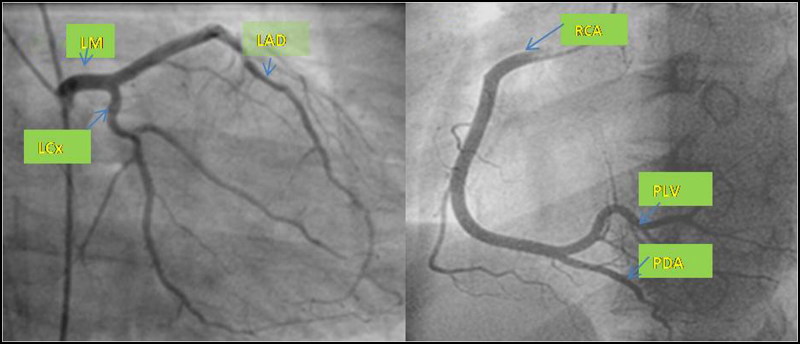

Repeat echocardiogram on the second day of hospitalization demonstrated normalization of the ventricular ejection fraction to 70%. By the third day, there was interval resolution of hemoptysis, and the chest radiograph showed significant improvement of infiltrates leading to successful extubation. However, the patient reported atypical chest pressure with evidence of mild ST depressions and T-wave inversions on electrocardiogram. Troponin was abnormal at 3.3 ng/mL, though it demonstrated a downward trend. Urgent coronary angiography and catheterization demonstrated normal coronaries, a left ventricular end diastolic pressure of 18 mm Hg, and normal left ventricular contractility (Figure 3). Medical therapy was optimized with scheduled administration of low-dose lisinopril and metoprolol and as-needed furosemide. The patient was discharged on the fifth day of hospitalization.

Figure 3.

Coronary angiography demonstrates normal left main (LM), left anterior descending (LAD), left circumflex (LCx), and right coronary (RCA) arteries. PLV indicates posterior left ventricular artery; PDA, posterior descending artery.

DISCUSSION

This case highlights a serious adverse cardiac event resulting from inadvertent administration of a high dose of intravenous epinephrine in a patient with anaphylaxis. Our patient developed accelerated hypertension followed by myocardial dysfunction, as well as hemoptysis resulting in acute cardiopulmonary failure. Several of these observed adverse effects have been previously reported with excess epinephrine administration.6,7

Excess catecholamines can cause multivessel coronary and arterial vasospasm,8 increased mean arterial pressure and ventricular afterload, impaired microcirculatory dysfunction,9 and myocardial stunning.10,11 Pulmonary edema and hemorrhage may result from severely increased mean arterial pressure and pulmonary backflow due to significant ventricular dysfunction. In vivo studies have shown the development of acute reversible apical hypokinesis similar to TC after the administration of intraperitoneal or intravenous catecholamines.12

Classic TC is characterized by transient apical systolic dysfunction, usually in postmenopausal women due to estrogen insufficiency and altered catecholamine hormonal receptor sensitivity.11 This can be associated with dynamic electrocardiographic changes, ranging from transient ST elevations at onset subsequently transitioning to deep T-wave inversions followed by late normalization of T-waves.3,5,13–17 In contrast, patients with reverse TC usually present at a younger age and often have an emotional or physical trigger leading to basal and/or midventricular hypokinesis but preserved apical contractility, as seen in our patient.18 Reverse TC is also typically more likely to be complicated by pulmonary edema and cardiogenic shock.5,19

The plausible underlying mechanisms for TC are sympathetic hyperactivity, multivessel transient coronary vasospasm,8 estrogen deficiency,9,17 and microcirculatory dysfunction.5,9,20,21 There is a near-complete resolution of myocardial dysfunction in most patients usually within a few weeks. The reverse pattern TC coupled with a very rapid resolution of ventricular dysfunction in our young male patient further supports the causation related to an inadvertent high-dose epinephrine administration. The usual recommended dose of epinephrine administration for anaphylaxis is 0.2 mL to 0.5 mL subcutaneously for adults at a concentration of 1:1000 dilution repeated at 10- to 15-minute intervals. If there is no response, a 0.1-mg (1:10,000 dilution) dose of intravenous epinephrine can be administered with close cardiac monitoring.22 Contrary to this guidance, our patient received a fairly high intravenous concentration. The potential risk of TC significantly increases at high intravenous epinephrine doses, generally >1 mg. Thus, it is important for physicians to entertain the possibility of iatrogenic TC in patients receiving a high catecholamine dose. Institution of early appropriate supportive therapy can avert the deleterious outcomes and ensure a good patient prognosis.

References

- 1.Powers FM, Pifarre R, Thomas JX Jr.. Ventricular dysfunction in norepinephrine-induced cardiomyopathy. Circ Shock. 1994;43:122–129. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Kurowski V, Kaiser A, von Hof K, et al. Apical and midventricular transient left ventricular dysfunction syndrome (tako-tsubo cardiomyopathy): frequency, mechanisms, and prognosis. Chest. 2007;132:809–816 doi: 10.1378/chest.07-0608. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Khalid N, Chhabra L. Pathophysiology of takotsubo syndrome. StatPearls Web site. Published 2019. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Khalid N, Ahmad SA, Chhabra L Pathophysiology of Takotsubo Syndrome In: StatPearls [Internet]. Treasure Island, FL: StatPearls Publishing. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK538160/ [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Awad HH, McNeal AR, Goyal H. Reverse takotsubo cardiomyopathy: a comprehensive review. Ann Transl Med. 2018;6:460. doi: 10.21037/atm.2018.11.08. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Murthy A, Henien S, McPherson CA, Logue MA. Epinephrine use results in “stress” cardiomyopathy. J Cardiol Cases. 2015;11(3):85–87. doi: 10.1016/j.jccase.2014.11.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Nazir S, Melnick S, Lohani S, Lloyd B. Rare case of stress cardiomyopathy due to intramuscular epinephrine administration. BMJ Case Rep. 2016;2016. doi: 10.1136/bcr-2016-215691. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Braunwald E, Kloner RA. The stunned myocardium: prolonged, postischemic ventricular dysfunction. Circulation. 1982;66:1146–1149. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Chhabra L, Sareen P. Takotsubo cardiomyopathy and microvascular dysfunction. Int J Cardiol. 2015;196:107. doi: 10.1016/j.ijcard.2015.05.161. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Lyon AR, Rees PS, Prasad S, Poole-Wilson PA, Harding SE. Stress (takotsubo) cardiomyopathy—a novel pathophysiological hypothesis to explain catecholamine-induced acute myocardial stunning. Nat Rev Cardiol. 2008;5:22–29. doi: 10.1038/ncpcardio1066. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Abraham J, Mudd JO, Kapur N, Klein K, Champion HC, Wittstein IS. Stress cardiomyopathy after intravenous administration of catecholamines and beta-receptor agonists. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2009;53:1320–1325. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2009.02.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Williams R, Arri S, Prasad A. Current concepts in the pathogenesis of takotsubo syndrome. Heart Fail Clin. 2016;12:473–484. doi: 10.1016/j.hfc.2016.06.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Ramaraj R, Movahed MR. Reverse or inverted takotsubo cardiomyopathy (reverse left ventricular apical ballooning syndrome) presents at a younger age compared with the mid or apical variant and is always associated with triggering stress. Congest Heart Fail. 2010;16:284–286. doi: 10.1111/j.1751-7133.2010.00188.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Bybee KA, Kara T, Prasad A, et al. Systematic review: transient left ventricular apical ballooning: a syndrome that mimics ST-segment elevation myocardial infarction. Ann Intern Med. 2004;141:858–865. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Khalid N, Ahmad SA, Shlofmitz E, Umer A, Chhabra L. Sex disparities and microvascular dysfunction. Int J Cardiol. 2019;282:16. doi: 10.1016/j.ijcard.2018.11.129. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Ueyama T, Hano T, Kasamatsu K, Yamamoto K, Tsuruo Y, Nishio I. Estrogen attenuates the emotional stress–induced cardiac responses in the animal model of tako-tsubo (ampulla) cardiomyopathy. J Cardiovasc Pharmacol. 2003;42(Suppl 1):S117–S119. doi: 10.1097/00005344-200312001-00024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Chhabra L. Myopericarditis and takotsubo cardiomyopathy association. Int J Cardiol. 2015;186:143. doi: 10.1016/j.ijcard.2015.03.228. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Chhabra L, Khalid N, Sareen P. Extremely low prevalence of takotsubo cardiomyopathy and transient cardiac dysfunction in stroke patients with T-wave abnormalities. Am J Cardiol. 2019;123:1009. doi: 10.1016/j.amjcard.2019.01.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Khalid N, Ahmad SA, Shlofmitz E, Chhabra L. Racial and gender disparities among patients with takotsubo syndrome. Clin Cardiol. 2019;42:19. doi: 10.1002/clc.23130. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Khalid N, Chhabra L. Takotsubo cardiomyopathy and microcirculatory dysfunction. Nat Rev Cardiol. 2015;12:497. doi: 10.1038/nrcardio.2015.88. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Khalid N, Ahmad SA, Umer A, Chhabra L. Role of microcirculatory disturbances and diabetic autonomic neuropathy in takotsubo cardiomyopathy. Crit Care Med. 2015;43:e527. doi: 10.1097/CCM.0000000000001183. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Tang AW. A practical guide to anaphylaxis. Am Fam Physician. 2003;68:1325–1332. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]