Abstract

Background and aims

Steroid therapy is the first-line treatment for autoimmune pancreatitis but relapses are frequent. The aims were to assess the efficacy and the safety of immunomodulator treatments for relapsing autoimmune pancreatitis and rituximab in particular and to identify relapsing risk factors.

Methods

Patients followed for autoimmune pancreatitis from 2000 to 2016 were included. Data were retrospectively analysed regarding autoimmune pancreatitis treatment.

Results

In total, 162 patients with autoimmune pancreatitis type 1 (n = 92) and type 2 (n = 70) were included (median follow-up: 3 years (0.5–14). Relapse occurred in 46.5% of patients with autoimmune pancreatitis type 1 (vs 19.3% in autoimmune pancreatitis 2; p < 0.001). Risk factors of relapse were cholangitis, initial use of steroids, other organ involvement and chronic pancreatitis in autoimmune pancreatitis type 1 and initial use of steroids, tobacco consumption and chronic pancreatitis for autoimmune pancreatitis type 2. Overall, 21 patients were treated with immunomodulators (azathioprine, n = 19, or methotrexate, n = 2) for relapses. The efficiency rate was 67%. A total of 17 patients were treated with rituximab, with two perfusions at 15 days apart. The efficacy was 94% (16/17), significantly better than immunomodulator drugs (p = 0.03), with a median follow-up of 20 months (11–44). Only two patients needed two supplementary perfusions.

Conclusion

In relapsing autoimmune pancreatitis, rituximab is more efficient than immunomodulator drugs and shows better tolerance.

Keywords: Autoimmune pancreatitis, IgG4 related disease, cholangitis, rituximab, azathioprine

Key summary

Established knowledge on this subject

Steroid therapy is the first-line treatment in autoimmune pancreatitis (AIP), with a high efficacy rate of over 90%.

Relapses are frequent, especially in type 1 AIP, affecting more than 30% of patients.

Different treatments are available, including azathioprine, methotrexate and rituximab, but none is considered a gold standard.

Significant or new findings of this study

Rituximab had a high success rate for induction and maintenance of remission in relapsing AIP, even in patients previously treated with immunomodulator (IM) drugs.

This treatment was more efficient and had a better tolerance compared with IM.

The rheumatoid arthritis protocol with two perfusions of rituximab 15 days apart is effective and sufficient.

Introduction

Autoimmune pancreatitis (AIP)1 is a chronic fibro-inflammatory disease with two histologically distinct forms: lymphoplasmacytic sclerosing pancreatitis and idiopathic duct centric pancreatitis.2 These two forms, respectively type 1 and type 2 AIP, have distinct clinical phenotypes.3

Type 1 AIP corresponds to the pancreatic involvement of the systemic IgG4-related disease (IgG4-RD),4,5 including an elevation of serum IgG4 levels (80%) and abundant tissue infiltration by lymphocytes and plasmocytes (IgG4-positive for immunochemistry analysis). Other organ involvement (OOI) is frequent, particularly the biliary involvement called IgG4-113-related cholangitis. Type 2 AIP corresponds to an isolated pancreatic disease, classically revealed by acute pancreatitis. Inflammatory bowel disease (IBD) is associated with about one-third of cases and is now considered a diagnostic criterion. In some cases, the distinction between the subtypes may not be possible and AIP should be classified as ‘not otherwise specified’.5

Steroid therapy is the first-line treatment, indicated in symptomatic disease (cholestasis, jaundice, recurrent pancreatitis) with an efficacy rate around 90%.6,7 Despite an high initial remission rate, 30–50% of patients will relapse, especially type 1 AIP.8,9 Masamune et al.10 showed that maintenance of a low dose of steroids (7.5 mg/day for 3 years) could reduce the risk of relapse from 57.9% to 23.3%.

However, the risk induced by a long-term steroid therapy warrants reconsideration of this option. Based on other gastrointestinal autoimmune disorders, immunomodulator (IM) drugs have been used to prevent relapse (azathioprine and methotrexate) with positive results.11–13 More recently, rituximab, an antiCD20 monoclonal antibody, has been proposed. The first series demonstrated its efficiency to induce and maintain remission in case of relapses. However, only a few series are available11,14 to confirm these data.

In 2017, an expert consensus proposed several options for treating relapsing AIP: maintenance dose of steroids, IMs (azathioprine, methotrexate, mycophenolate mofetil), or rituximab.15 However, these recommendations are based on small retrospective series and no data are available to compare these options.

The aims of this study were to assess the efficacy and the safety of IM treatments in case of relapsing AIP, in particular rituximab, and to identify relapsing risk factors.

Patients and methods

Inclusion criteria

We conducted a retrospective study including all patients with AIP followed in the pancreatology department of Beaujon Hospital between January 2000 and December 2016.

Patients were included if they had a certain or possible diagnosis of AIP according to the international criteria for AIP5 or IgG4-RD with pancreatic involvement.4 For patients diagnosed before 2011, the diagnosis was retrospectively reviewed following these criteria. All patients were classified as type 1 AIP or type 2 considering the pathological findings, the serum IgG4 level, OOI and the association with IBD. Exclusion criteria were a follow-up less than 3 months and no initial cross-sectional imaging at diagnosis. Patients were also excluded if they did not reach the diagnosis criteria or were diagnosed with unspecified AIP. Our local ethical review board approved this study (decision number: AAA-2019-08011). Informed consent was obtained for each patient. The study protocol conforms to the ethical guidelines of the 1975 Declaration of Helsinki as reflected in approval by the institution's human research committee.

Clinical and morphological data

Clinical data included the age of the patients at diagnosis, previous surgical procedures, disease-related symptoms, IgG4 serum levels, treatments and relapse characteristics. Tobacco consumption was quantified in pack years and alcohol consumption was considered if superior to 20 g/day. Long-term complications as diabetes and exocrine pancreatic insufficiency were recorded. Diabetes was defined by two fasting glucose measurements above 7.0 mmol/l, with systematic screening every 6 to 12 months. Exocrine pancreatic insufficiency was tested on the basis of symptoms and faecal elastase was measured in the case of diarrhoea or clinical steatorrhea. For patients treated with immunosuppressants, the evolution of symptoms and biological data were recorded.

Cross-sectional imaging comprising both multidetector row computed tomography (MDCT) and magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) with magnetic resonance – cholangiopancreatography (MRCP) were reviewed by a radiologist specialized in pancreatic diseases (MPV). Imaging data recorded were: pancreatic duct involvement (ie narrowing of main pancreatic duct (MPD), long vanishing defined as >1/3 length of the MPD, multifocal MPD vanishing, dilatation of MPD >5mm), parenchymal involvement (focal mass, diffuse enlargement) as well as chronic pancreatitis (defined by pancreatic parenchymal atrophy and duct abnormalities with irregular MPD, with focal dilation or stenosis), biliary tract abnormalities (diffuse cholangitis, proximal cholangitis, distal cholangitis) and OOI (kidney, lung, lymphadenopathy). A comparison of the cross-sectional imaging before and after treatment was performed.

Treatment protocols

Patients were treated by a course of steroid therapy in the case of symptomatic disease, including pancreatic pain, recurrent acute pancreatitis, cholestasis or jaundice.15 The daily dose of prednisolone was 40 mg for 4 weeks and gradually tapered by 5 mg every week. In patients with radiological abnormalities but no symptoms, a clinical, biological and morphological surveillance was performed without steroid therapy.

Relapse was defined as clinical or biological flare up of the disease, with reappearance of pancreatic pain, acute pancreatitis, biological cholestasis, jaundice, or extra pancreatic manifestations after remission and cessation of steroids.12 Dependence on steroids was defined by a recurrence of symptoms during steroid therapy tapering leading to prolonged treatment (>3 months) with moderate dosage ≥15 mg.11 Steroid resistance was defined by the persistence of symptoms without any improvement after 15 days at a full dose of steroids of 40 mg/day. New cross-sectional imaging was performed to confirm the relapse if it occurred more than 3 months after previous treatment.

Maintenance treatment was administered in the case of dependence on steroids, or after more than two relapses. The first-line maintenance therapy was azathioprine, methotrexate was given in the case of contraindication. Rituximab was given in the case of failure of the previous IMs except in the last 3 years of the study, where rituximab has become the first-line treatment.

Azathioprine was given at the dosage of 2–2.5 mg/kg/day and maintained at least for 3 years. Methotrexate was given at the dosage of 15 mg per week at least for 3 years. Rituximab is an off-label treatment in France in the indication of relapsing AIP and its administration needs to be validated by a consultation meeting. Screening for hepatitis B, C and HIV was performed before treatment administration. Pre-treatment with 100 mg of methylprednisolone and 10 mg of dexchlorpheniramine was performed. Rituximab was given at the dosage of 1000 mg. The protocol included the administration of two intravenous infusions 15 days apart, as proposed for rheumatoid arthritis. Steroids were used in combination with rituximab in the case of patients with severe symptoms, particularly jaundice, and steroid tapering was quickly performed the day after the first rituximab infusion. Other IMs were also stopped. No systematic infusion was planned. Indication of new infusions depended on relapse symptoms. The decision was left to the clinician in charge of the patient.

Clinical follow-up protocol

Symptomatic patients were followed every 15 days by clinical examination and liver tests during the first month, then every month until 3 months, then every 3 to 6 months after symptom control. Serum IgG4 level measurements and morphological procedures were repeated 3 months after initiation of treatment then every year.

Statistical analysis

Data were expressed as median and range for quantitative data, or percentage for qualitative data. The initial characteristics of AIP were compared using Kruskal-Wallis test for continuous data, and Chi-squared or Fisher's exact test for categorical data. Survival curves were performed to assess disease-free survival according to the type of therapy: rituximab versus azathioprine. Comparisons were performed using the Log-Rank test. All statistical tests were two-sided. The critical level of statistical relevance was set at a p value < 0.05. Statistical analyses were performed using the SAS 9.1 statistical software for Windows (SAS Institute Inc., Cary, NC).

Results

Clinical characteristics

A total of 162 patients met the inclusion criteria, grouped as type 1 (n = 92) and type 2 (n = 70) AIP. The comparison of clinical characteristics according to AIP subtypes is summarized in Table 1. Patients were followed for a median time of 3 years (0.5–14) for type 1 AIP and 2.1 years (0.25–17) for type 2 AIP.

Table 1.

Clinical characteristics of the patients.

| Type 1 AIP (n = 92) | Type 2 AIP (n = 70) | p value | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age at diagnosisa | 58 (22–78) | 32 (17–75) | <0.001 |

| Sex ratio (M/F) | 76.4% | 50.7% | 0.0008 |

| Symptoms at diagnosis | <0.0001 | ||

| Jaundice (n/%) | 44/48% | 5/7% | |

| Acute pancreatitis (n/%) | 11/12% | 43/61% | |

| Chronic pancreatic pain (n/%) | 16/17% | 11/16% | |

| OOI | 64/70% | 2/3% | <0.001 |

| Cholangitis (n/%) | 58/63% | 2/3% | |

| Renal involvement (n/%) | 11/12% | 0 | |

| Pulmonary involvement (n/%) | 9/10% | 0 | |

| Association with IBD (n/%) | 1/1% | 47/67% | 0.028 |

| Follow-up duration (years)a | 2.8 [0.5-14] | 1.9 [0.25-17.5] | 0.06 |

| Diabetes (n/%) | 41/45% | 4/6% | <0.0001 |

| Exocrine pancreatic insufficiency (n/%) | 36/39% | 11/16% | 0.001 |

Expressed as median and range.

AIP: auto-immune pancreatitis; F: female; IBD: inflammatory bowel disease; M: male; OOI: other organ involvement.

Treatment and relapses

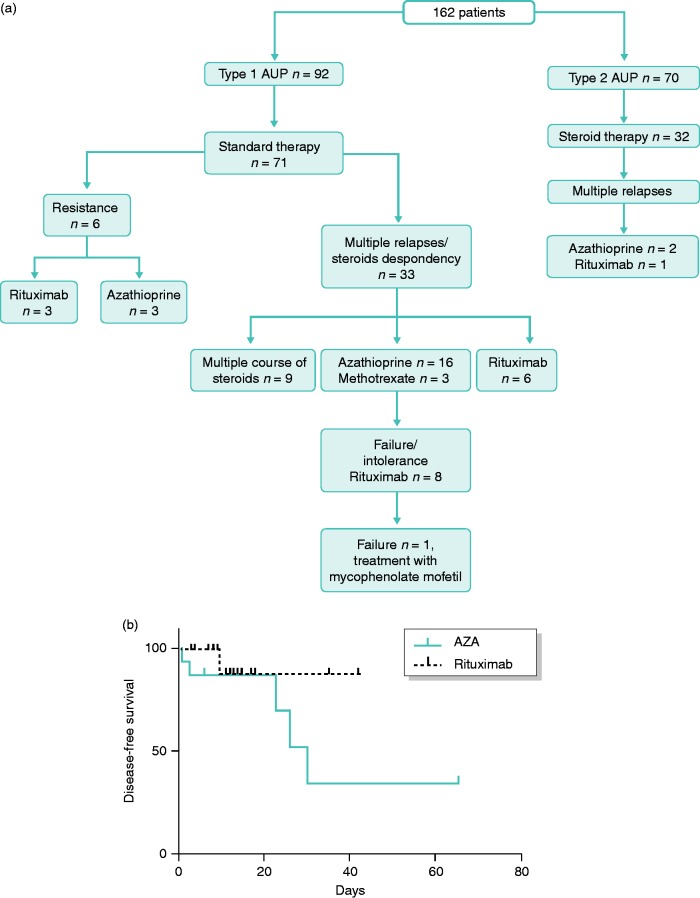

Treatment distribution among AIP patients is summarized in Figure 1.

Figure 1.

(a) Distribution of patient treatment according to the two auto-immune pancreatitis (AIP) subtypes and (b) Disease-free survival according to treatment: rituximab versus azathioprine.

In total, 71 patients with type 1 AIP needed steroids (77.1%) versus 32 patients with type 2 (45.7%; p < 0.001). Other patients (30 type 1 AIP and 38 type 2 AIP) were not treated according to consensus treatment; most had acute pancreatitis with no persistent symptom. Among these, three patients had a second flare up of the disease, but no patient required immunosuppressive treatment. Steroid therapy was efficient in 95 patients (92.2%). After this first line of treatment, relapse occurred in 33 patients with type 1 AIP (46.5%) versus four patients with type 2 AIP (12.5%; p < 0.001).

Relapse manifestations were mainly cholestasis with or without jaundice in type 1 AIP (n = 23/33; 70%), chronic pancreatic pain (n = 6/33; 18%) and acute pancreatitis (n = 4; 12%). For type 2 AIP, relapse manifested as acute pancreatitis (n = 5/8) or chronic pancreatic pain (n = 3/8). Median time to relapse was 8 months (0–120) after remission.

Predictive factors for relapse are summarized in Table 2. Cholangitis and initial need for steroid therapy were strongly associated with a higher risk of relapse for type 1 AIP (p = 0.0003) followed by OOI (p = 0.05). A high IgG4 serum level was not associated with a higher risk of relapse. Chronic pancreatitis was the only radiological sign associated with risk of relapse for both type 1 and type 2 AIP (p = 0.05 and 0.01 respectively). For type 2 AIP, tobacco consumption (p = 0.05) and initial need for steroids (p = 0.06) were the only clinical factors predictive of relapse.

Table 2.

Predictive factors for relapse (univariate analysis).

| Type 1 AIP |

Type 2 AIP |

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Relapse (n = 39)/ no relapse (n = 53) | p value | Relapse (n = 10)/ no relapse (n = 60) | p value | |

| Elevated IgG4 level | 25 (64%)/28 (53%) | NS | 0/4 | N/A |

| OOI | 35 (90%)/30 (57%) | 0.005 | 1/1 | N/A |

| Cholangitis | 35 (90%)/25 (47%) | 0.0003 | 1/1 | N/A |

| Steroids treatment | 39 (100%)/30 (57%) | 0.0003 | 8 (80%)/24 (40%) | 0.06 |

| Chronic pancreatitis on CT | 18 (46%)/14 (26%) | 0.05 | 7 (70%)/18 (30%) | 0.01 |

| Tobacco consumption | 13 (33%)/17 (32%) | NS | 6 (60%)/28 (47%) | 0.05 |

AIP: auto-immune pancreatitis; CT: computed tomography; OOI: other organ involvement; NS: not significant; N/A: not applicable.

Immunosuppressive treatment for type 1 AIP

In total, 21 patients were treated with IMs: azathioprine (n = 19), and methotrexate (n = 2). Indications were a relapsing disease for 18 patients and resistance to steroids for three. Four patients treated with azathioprine had a history of Whipple procedure at diagnosis, due to a risk of pancreatic cancer. The treatment was effective on preventing relapse for 14 patients (67%). The median time of follow-up with efficient azathioprine treatment was 17 months (3–66). Four patients had relapse with cholangitis (cholestasis or jaundice) and were treated with rituximab, and three stopped azathioprine because of intolerance (nausea and vomiting); two of these patients were switched to rituximab.

At the end of the maintenance treatment with azathioprine after 3 years, 3/12 (25%) patients had a relapse of the disease, within 6 months for two of them. One was treated by a new course of steroids, another one resumed azathioprine and the last was treated by rituximab (Figure 1(a)).

Patients resistant to steroids had an increase in the dosage to 1 mg/kg when beginning azathioprine. A delayed response was observed with a longer need for steroids, but no relapse was observed for these three patients and no other medication was administered.

Rituximab treatment

Rituximab was used for 17 type 1 AIP patients. Baseline characteristics of these patients are summarized in Table 3. IgG4 level was elevated at the diagnosis of AIP for 12 patients (70.6%). Two patients had a previous treatment by surgery (Whipple procedure) because of a risk of cancer. A third patient (patient 10) had a biliary resection for biliary stenosis refractory to steroid treatment because of a suspicion of cholangiocarcinoma.

Table 3.

Baseline characteristics of the 17 patients treated with rituximab at AIP diagnosis.

| Patient | AIP | Age | Sex | IgG4a | OOI | Pancreatic morphology | Histology (site, results)a |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 1 | 45 | M | 8.01 | Cholangitis | Diffuse enlargement | Duodenum: LP infiltration, IgG4 + |

| 2 | 1 | 70 | M | 4.05 | Cholangitis | Diffuse enlargement | Pancreas: LP infiltration, IgG4 + |

| 3 | 1 | 70 | M | 4.72 | Cholangitis, kidney | Focal mass | Pancreas: LP infiltration, IgG4 - |

| 4 | 1 | 56 | M | 2.63 | None | Focal mass | Pancreas: LP infiltration, IgG4 + |

| 5 | 1 | 60 | F | 3.11 | Cholangitis | Diffuse enlargement | Pancreas: normal |

| 6 | 1 | 68 | M | 10.8 | Cholangitis, kidney, lymph node | Focal mass | Pancreas: normal |

| 7 | 1 | 30 | F | 0.66 | None | Focal mass | None |

| 8 | 1 | 66 | M | 5.40 | Cholangitis, lung | Focal mass | Lung: LP infiltration, IgG4 + |

| 9 | 1 | 58 | F | – | Cholangitis | Focal mass | None |

| 10 | 1 | 60 | M | 1.01 | Cholangitis | Bile duct: LP infiltration, IgG4 + | |

| 11 | 1 | 73 | M | 5.22 | None | Focal mass | Pancreas: LP infiltration, IgG4 - |

| 12 | 1 | 72 | M | – | Lymph node | Focal mass | Pancreas: LP infiltration, IgG4 + |

| 13 | 1 | 60 | M | 7.59 | Cholangitis | Diffuse enlargement | Pancreas: LP infiltration, IgG4 + |

| 14 | 1 | 63 | M | 0.75 | Cholangitis | Focal mass | Pancreas: LP infiltration, IgG4 + |

| 15 | 1 | 54 | F | 5.05 | Cholangitis | Focal mass with halo | None |

| 16 | 1 | 44 | F | 1.76 | Cholangitis | Diffuse enlargement with halo | Pancreas: LP infiltration, IgG4 + |

| 17 | 1 | 64 | M | 8.42 | Cholangitis | Focal mass | Liver: no LP infiltration, IgG4 + |

IgG4 values are given in g/l; IgG4 infiltration on tissue was considered positive.

AIP: auto-immune pancreatitis; F: female; M: male; OOI: other organ involvement; LP: lymphoplasmacytic.

Treatment characteristics are summarized in Table 4. All patients had at least one course of steroids before rituximab use. Rituximab was used to induce remission after resistance to steroids (n = 3), to maintain remission after steroids dependency (n = 6), and after multiples relapses (n = 8). Seven patients had previous treatment with immunosuppressants (azathioprine, n = 6, and methotrexate, n = 1). Three patients stopped azathioprine for intolerance, four relapsed under IM and were switched to rituximab.

Table 4.

Previous treatments and clinico-biological characteristics of the 17 patients at the time of treatment with rituximab.

| Patient | Clinical symptoms | Courses of steroids | Previous IM treatment | Surgery | IgG4 (n) | ALAT | ALP | Indication rituximab | Number of perfusions |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Cholangitis | 1 | 0 | 0 | 2 | 13 | 4 | Resistance to steroids | 2 |

| 2 | Cholangitis | 2 | 0 | 0 | N | 6 | 4 | Multiple relapses | 2 |

| 3 | Cholangitis | 3 | 0 | 0 | 1.5 | 9 | 8.5 | Multiple relapses | 2 |

| 4 | Cholangitis | 2 | 0 | 0 | 2 | 1.5 | 1.5 | Resistance to steroids | 2 |

| 5 | Cholangitis | 3 | AZA, intolerance | 0 | 2.5 | 1.7 | 2.4 | Multiple relapses, intolerance AZA | 2 |

| 6 | Cholangitis | 1 | 0 | 0 | 18 | 2.5 | 5 | Dependency to steroids | 4 |

| 7 | Pancreatic pain, cholangitis | 1 | AZA 2 months, intolerance | 0 | N | N | N | Dependency to steroids | 4 |

| 8 | Cholangitis | 3 | 0 | 0 | 4.5 | 2.5 | 6 | Multiple relapses | 2 |

| 9 | Pancreatic pain | 2 | MTX 14 months | 0 | N | N | N | Dependency to steroids | 2 |

| 10 | Cholangitis | 2 | AZA 10 months | Biliary resection | 2 | 1.5 | 1.2 | Multiple relapses, failure of AZA | 2 |

| 11 | Metachronous cholangitis | 2 | AZA and 6-MP, intolerance | 0 | 2 | N | N | Multiple relapses, intolerance AZA | 2 |

| 12 | Cholangitis | 2 | AZA 24 months | Whipple procedure | 5 | 1.5 | 4 | Multiple relapses, failure of AZA | 2 |

| 13 | Cholangitis | 1 | 0 | 0 | 4 | 3.5 | 3 | Dependency to steroids | 2 |

| 14 | Cholangitis | 1 | 0 | Whipple procedure | N | 4 | 1.5 | Resistance to steroids | 2 |

| 15 | Cholangitis | 2 | 0 | 0 | 3.6 | 10 | 6 | Dependency to steroids | 2 |

| 16 | Cholangitis | 3 | AZA 20 months | 0 | N | 1.3 | 1.2 | Multiple relapses, failure of AZA | 2 |

| 17 | Cholangitis | 4 | AZA 10 months | 0 | 1.5 | 1.5 | 2 | Multiple relapses, failure of AZA | 2 |

IM: immunomodulator; AZA: azathioprine; MTX: methotrexate; N: normal value; ALAT: alanine amino transaminase; ALP: alkaline phosphatase.

The treatment was efficient for 16 patients (94.1%) and was significantly more efficient than IM drugs (p = 0.03). All patients received two infusions of rituximab; however, two patients needed two supplementary perfusions. Patient 7 was treated for pancreatic pain, with partial efficacy of rituximab, and thus needed two more perfusions. Patient 6 was treated for cholangitis and was controlled for 10 months after the first two perfusions, after a new relapse he had two more doses of rituximab. All patients stopped steroids within 2 months after rituximab administration. One patient had a persistent disease after treatment with rituximab, despite a CD20 lymphocyte decrease, and was treated successfully with mycophenolate mofetil. Survival analysis were performed to assess the disease-free survival according to the type of treatment, rituximab versus azathioprine. (Figure 1(b)).

The median time of remission after treatment was 20 months (11–44). No serious adverse events were reported.

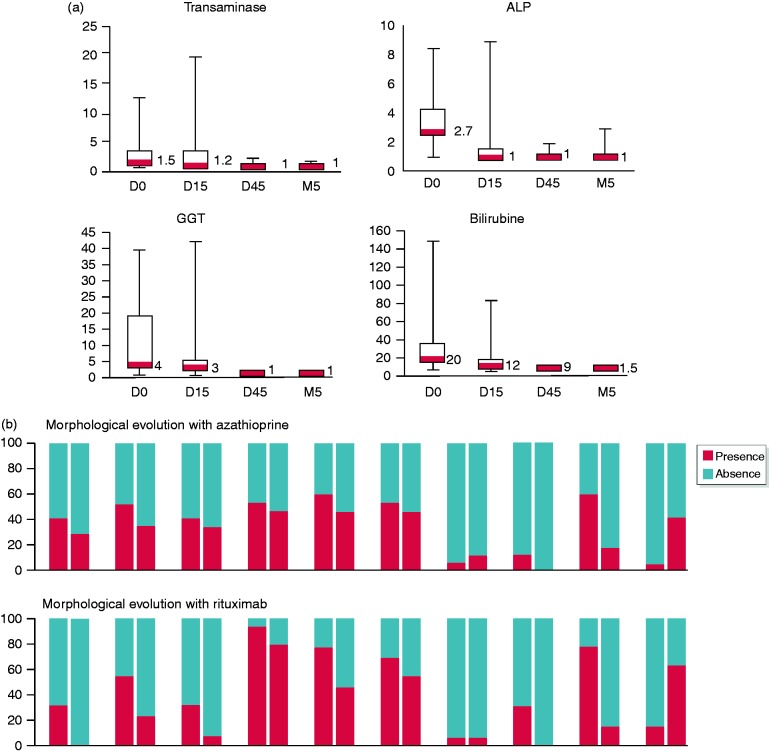

Rituximab allowed a rapid normalization of liver enzymes (Figure 2(a)). After 15 days, transaminase, alkaline phosphatase, gamma-glutamyl transferase and bilirubin were normalized in 72%, 78%, 44% and 78% of patients, respectively. All enzyme levels were normal after 45 days, except gamma-glutamyl transferase for three patients. IgG4 serum level was normalized after 3 months for nine patients, out of 12 with elevated IgG4 level before treatment (75%).

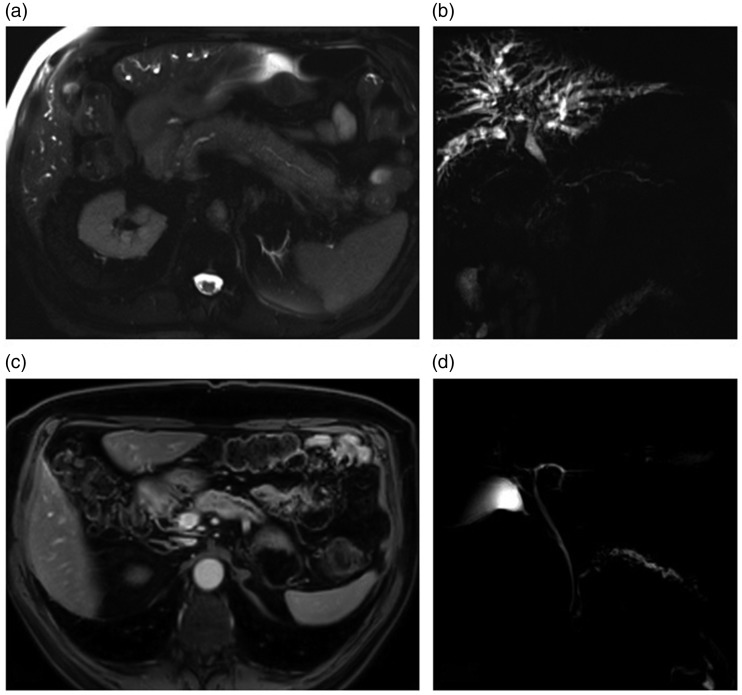

Figure 3.

: Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) of a patient before and after rituximab treatment. (a) Axial T2, before treatment; diffuse pancreatic enlargement, ‘sausage-like’ appearance. (b) MRCP, before treatment; diffuse cholangitis with numerous typical biliary stenosis, mainly perihilar, stenosis of main pancreatic duct (MPD) upstream of the pancreas head. Typical MPD abnormalities: vanishing portion, without upstream enlargement, multiples, involving >1/3 of MPD. (c) Axial enhanced T1 after treatment; regression of pancreatic inflammation, pancreatic atrophy. (d) magnetic resonance – cholangiopancreatography (MRCP), after treatment; regression of cholangitis pattern biliary tree is normal, but appearance of chronic pancreatitis.

Figure 2.

(a) Biological evolution of liver enzymes in patients treated with rituximab. ALAT: alanine amino transaminase; ALP: alkaline phosphatase; GGT: gamma-glutamyl transferase; ULN: upper limit of normal. (b) Evolution of morphological features before and after azathioprine and rituximab. SC: sclerosing cholangitis; MPD: main pancreatic duct (including narrowing, long vanishing > 1/3 of MPD, multifocal vanishing, dilatation < 5 mm); CP: chronic pancreatitis.

Evolution of the morphological features of the patients treated with azathioprine and rituximab is presented in Figure 2(b). Diffuse pancreatic enlargement was significantly normalized after azathioprine (p = 0.001) or rituximab treatment (p = 0.004). For patients treated by rituximab, a trend for normalization of focal pancreatic enlargement (p = 0.09) and diffuse cholangitis (p = 0.09) can be noticed. Evolution to chronic pancreatitis was not stopped by the treatment in both azathioprine and rituximab groups (p = 0.06 and p = 0.04 respectively).

Discussion

This study reports the results of a large series of patients with relapsing AIP treated by IMs and rituximab, in particular. We showed that immunosuppressive treatments were effective in maintaining disease remission and in preventing relapses. The efficacy with IMs was 65% with a median follow-up of 17 months. With rituximab therapy, the efficacy reached 94.1% with a median follow up of 20 months, even for patients resistant to previous immunosuppressive treatments.

Three options are available for maintenance therapy in patients with relapsing AIP: low doses of steroids, IMs or rituximab. No comparison between rituximab and other immunosuppressors have been performed. Thus, there is no ‘gold-standard’ treatment according to the expert consensus for relapsing AIP.15

Azathioprine showed an efficacy rate of 66.7%. No prospective data are available due to the rare condition of AIP, but other studies show a similar efficacy rate around 70%.12,13 Another point is the duration of this treatment. In this study, azathioprine was maintained for at least 3 years, but no data could justify this duration. After discontinuation of the treatment, the risk of relapse persisted and reached 25%. However, regarding the long-term adverse events of azathioprine assessed in patients with IBD,16 it is necessary to limit the duration of treatment. In a prospective cohort, the risk of lymphoproliferative disorders in patients treated by thiopurines was 5.28 (2.01–13.9), compared to controls. This risk increased in males, aged over 65 years. These risk factors correspond to the main characteristics of patients with type 1 AIP, which are more likely to be male, aged over 60 years. However, no evidence has so far proved that these results should be translated to AIP patients.

Rituximab showed a significantly better efficacy rate (94%; p = 0.03) in 17 patients with type 1 AIP. The Mayo Clinic series11 reports a similar experience; 12 patients were treated with rituximab with a high success rate (10/12; 83.3%) and no serious adverse events were observed. The population of this study was similar to the present one, with patients refractory to other IM and presenting with cholangitis. The major difference was the rituximab protocol: in this study, only two systematic perfusions of rituximab were administered, whereas 10 perfusions were systematic in the Mayo series, including maintenance infusions every 2–3 months over 24 months. In the present study, one patient needed two supplementary perfusions for partial response and one patient had a relapse after 10 months controlled by two additional infusions. Median follow-up after the last perfusion was 14 months, with a distal range at 33 months.

Recently, a nationwide study of French patients treated with rituximab for IgG4-RD17 showed the same efficacy (93.5%). In this study, the patients had different manifestations of IgG4-RD, including nephritis, lymphadenopathy and orbital involvement and more than half did not have AIP or cholangitis. This study reported a longer follow-up (24.9 ± 21 months) and showed a relapse rate of 41.9% after a mean delay of 19 months after rituximab. Rituximab protocol was not standardized in this multicentric study but the patients had an induction regimen without maintenance. In the case of relapse after rituximab, retreatment was efficient with a longer relapse-free survival. These results sustain the idea that a first treatment with two infusions could be sufficient and retreatment could be driven by symptoms.

Recent advances in comprehension of IgG4-RD showed a main role of CD4 + T lymphocytes and plasmablasts18,19 and a specific depletion of these populations after rituximab. Rituximab induces a strong and prolonged immunodepression (6 months in median). In this study, we did not observe any adverse events even if we report on only 17 patients. The long-term risks of rituximab have been evaluated in rheumatoid arthritis in a study of 3194 patients.20 Over 9.5 years of follow-up, most patients received four perfusions. The risk of serious infection events reached 3.94/100 patient years, which was similar to the risk in patients treated with methotrexate in the long term. Thus, rituximab looks safe, with rare adverse events.

Finally, a high relapse rate was demonstrated, reaching 46.5% for type 1 AIP, significantly higher than for type 2 AIP (12.5%; p < 0.001). This allowed the study of relapse risk factors. This study assessed that OOI, cholangitis in particular, was a risk factor for a relapse of IgG4-RD. The initial need for steroid therapy is also an important point. IgG4 serum levels were not associated with a higher relapse risk. Data on relapsing risk factors are controversial. The international study of Hart et al.21 showed no association between IgG4 levels, or pancreas enlargement and relapse, whereas the Japanese multicentre studies7,22 found these factors had an impact. The strongest risk factor was a history of relapse.

A recent meta-analysis on risk factors including 36 studies also demonstrates that type 1 AIP has a higher relapse rate (37.5% vs 15.9%; p < 0.01).23 Tacelli et al. highlight the controversial results between the different studies. Jaundice was the most common significant risk factor for AIP in multivariate analysis. Induction and maintenance with steroid treatment was also retained in several studies, such as IgG4 serum level. However, in the pooled results, IgG4 level was not associated with a higher relapse rate. Finally, maintenance steroid therapy was the most important factor to prevent relapse, but results with IMs could not be studied. However, it is difficult to recommend maintenance therapy for every patient because the relapse risk did not reach 50%. In this study immunosuppressive treatments were only started after the first relapse or in the case of dependency or resistance to steroids, despite the expert consensus for AIP treatment.15 This consensus proposed a maintenance treatment after first steroid therapy for every patient with risk factors for relapse. Regarding such a difference on data on relapsing risk factors, it seems reasonable to wait for a first episode of relapse before introducing an immunosuppressive treatment.24

A major limitation of this study is the retrospective design. However, due to the rare condition of AIP, it is difficult to conduct a prospective large series. Another limitation is the long period of recruitment. We tried to correct this bias by reviewing every diagnosis regarding the International consensus diagnostic criteria, but it is clear that available treatments have changed over the period studied, leading to different strategies for some patients. Another difference is the definition of relapse based only in clinical or biological symptoms, which is different from other studies, where radiological relapse was also considered. Also, steroid dependence and resistance are not defined in the same way in different studies; this should be standardized.

The results of the study seem to support the use of rituximab in relapsing type 1 AIP prior to other treatments. Other IMs can be used in the case of contraindication or failure of rituximab. The rheumatoid arthritis protocol, with two initial infusions to induce remission and retreatment only in case of new relapse, seems to be appropriate, with the same efficacy, and would lead to a cost-effectiveness improvement. Further prospective, large-scale, multicentre studies comparing rituximab with other IMs should be conducted to confirm these results. This will also provide more information on relapsing factors and help clarify the indication of this maintenance treatment after the first flare.

Author contributions

Heithem Soliman and Vinciane Rebours: study design and concept, data acquisition, data analysis, statistical analysis and manuscript drafting.

Marie-Pierre Vullierme: study design and data acquisition.

Frédérique Maire, Olivia Hentic and Nelly Muller: data acquisition.

Philippe Ruszniewski and Philippe Lévy: critical revision and manuscript drafting.

Declaration of conflicting interests

The authors have no conflicts of interest to declare.

Funding

This research received no specific grant from any funding agency in the public, commercial, or not-for-profit sectors.

Informed consent

Informed consent was obtained for each patient.

Ethics approval

Local ethical review board approved this study (decision number: AAA-2019-08011). The study protocol conforms to the ethical guidelines of the 1975 Declaration of Helsinki as reflected in approval by the institution s human research committee.

References

- 1.Sarles H, Sarles JC, Muratore R, et al. Chronic inflammatory sclerosis of the pancreas: An autonomous pancreatic disease?. Am J Dig Dis 1961; 6: 688–698. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Zamboni G, Lüttges J, Capelli P, et al. Histopathological features of diagnostic and clinical relevance in autoimmune pancreatitis: A study on 53 resection specimens and 9 biopsy specimens. Virchows Arch 2004; 445: 552–563. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Kamisawa T, Notohara K, Shimosegawa T. Two clinicopathologic subtypes of autoimmune pancreatitis: LPSP and IDCP. Gastroenterology 2010; 139: 22–25. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Umehara H, Okazaki K, Masaki Y, et al. Comprehensive diagnostic criteria for IgG4-related disease (IgG4-RD), 2011. Mod Rheumatol 2012; 22: 21–30. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Shimosegawa T, Chari ST, Frulloni L, et al. International consensus diagnostic criteria for autoimmune pancreatitis: Guidelines of the International Association of Pancreatology. Pancreas 2011; 40: 352–358. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Hirano K, Tada M, Isayama H, et al. Long-term prognosis of autoimmune pancreatitis with and without corticosteroid treatment. Gut 2007; 56: 1719–1724. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Kamisawa T, Shimosegawa T, Okazaki K, et al. Standard steroid treatment for autoimmune pancreatitis. Gut 2009; 58: 1504–1507. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Maire F, Le Baleur Y, Rebours V, et al. Outcome of patients with type 1 or 2 autoimmune pancreatitis. Am J Gastroenterol 2011; 106: 151–156. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Sah RP, Chari ST, Pannala R, et al. Differences in clinical profile and relapse rate of type 1 versus type 2 autoimmune pancreatitis. Gastroenterology 2010; 139: 140–148. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Masamune A, Nishimori I, Kikuta K, et al. Randomised controlled trial of long-term maintenance corticosteroid therapy in patients with autoimmune pancreatitis. Gut 2017; 66: 487–494. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Hart PA, Topazian MD, Witzig TE, et al. Treatment of relapsing autoimmune pancreatitis with immunomodulators and rituximab: The Mayo Clinic experience. Gut 2013; 62: 1607–1615. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Sandanayake NS, Church NI, Chapman MH, et al. Presentation and management of post-treatment relapse in autoimmune pancreatitis/immunoglobulin G4-associated cholangitis. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol Off Clin Pract J Am Gastroenterol Assoc 2009; 7: 1089–1096. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.de Pretis N, Amodio A, Bernardoni L, et al. Azathioprine maintenance therapy to prevent relapses in autoimmune pancreatitis. Clin Transl Gastroenterol 2017; 8: e90. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Khosroshahi A, Carruthers MN, Deshpande V, et al. Rituximab for the treatment of IgG4-related disease: Lessons from 10 consecutive patients. Medicine (Baltimore) 2012; 91: 57–66. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Okazaki K, Chari ST, Frulloni L, et al. International consensus for the treatment of autoimmune pancreatitis. Pancreatology 2017; 17: 1–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Beaugerie L, Brousse N, Bouvier AM, et al. Lymphoproliferative disorders in patients receiving thiopurines for inflammatory bowel disease: A prospective observational cohort study. Lancet Lond Engl 2009; 374: 1617–1625. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Ebbo M, Grados A, Samson M, et al. Long-term efficacy and safety of rituximab in IgG4-related disease: Data from a French nationwide study of thirty-three patients. PloS One 2017; 12: e0183844. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Mattoo H, Mahajan VS, Della-Torre E, et al. De novo oligoclonal expansions of circulating plasmablasts in active and relapsing IgG4-related disease. J Allergy Clin Immunol 2014; 134: 679–687. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Mattoo H, Mahajan VS, Maehara T, et al. Clonal expansion of CD4 + cytotoxic T lymphocytes in patients with IgG 4 -related disease. J Allergy Clin Immunol 2016; 138: 825–838. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.van Vollenhoven RF, Emery P, Bingham CO, et al. Long-term safety of rituximab in rheumatoid arthritis: 9.5-year follow-up of the global clinical trial programme with a focus on adverse events of interest in RA patients. Ann Rheum Dis 2013; 72: 1496–1502. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Hart PA, Kamisawa T, Brugge WR, et al. Long-term outcomes of autoimmune pancreatitis: A multicentre, international analysis. Gut 2013; 62: 1771–1776. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Saeki T, Kawano M, Mizushima I, et al. The clinical course of patients with IgG4-related kidney disease. Kidney Int 2013; 84: 826–833. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Tacelli M, Celsa C, Magro B, et al. Risk factors for rate of relapse and effects of steroid maintenance therapy in patients with autoimmune pancreatitis: Systematic review and meta-analysis. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol Off Clin Pract J Am Gastroenterol Assoc 2019; 17: 1061–1072.e8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Ghazale A, Chari ST, Zhang L, et al. Immunoglobulin G4-associated cholangitis: Clinical profile and response to therapy. Gastroenterology 2008; 134: 706–715. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]