Abstract

Background

The aim of this research project, part of a program initiated by the Swiss Federal Council, was to trace the development of organized assisted suicide in Switzerland, starting from the very first case in 1985.

Methods

Retrospective data on 3666 death records from Swiss institutes of forensic medicine for the years 1985 to 2014 were systematically compiled, read into a database, and for the most part quantitatively evaluated.

Results

Alongside a marked increase in the overall number of assisted suicides since the turn of the century, the number of people traveling to Switzerland from other countries—predominantly Germany—for this purpose has risen steadily. The proportion of women was 60%, and the age at death ranged from 18 to 105 years (median 73). The largest diagnostic category was malignancy overall, neurological disease for those from other countries. The next largest category was age-related functional limitation, e.g., sensory impairment (loss of sight and hearing), the consequences of which were stated in writing as the reason for the wish to die. Following the Swiss Federal Court’s promulgation of binding requirements in 2006, the documentation contained in the death records for the subsequent period up to 2014 is much more detailed, but still not uniform or even necessarily complete.

Conclusion

The number of candidates for organized assisted suicide increased steadily during the study period, but no standard procedures were followed. The question therefore arises of whether further regulation or the introduction of a central registration office to maximize standardization and promote transparency would lead to improved quality assurance.

Assisted suicide has been anchored in the penal code in Switzerland since 1942 (article 115 of the Swiss Criminal Code) and is legal in certain circumstances—similar to the Benelux countries and some US states (Oregon, Washington, Montana, New Mexico, Vermont, and California) (1). Organizations providing assisted suicide have been providing their services officially under certain regulations (figure 1) since 1985. We use the term “assisted suicide” by analogy with the corresponding terminology in German. The German language has a variety of terms for the concept of assisted suicide, some of which seem less appropriate than others and should therefore be replaced by clearer (e.g., Suizidbeihilfe seems preferable to Sterbehilfe) or more neutral designations (Freitodhilfe e.g.,—a term that is preferred by organizations providing assisted suicide—has euphemistic undertones). For a discussion of the different terms in German see (2).

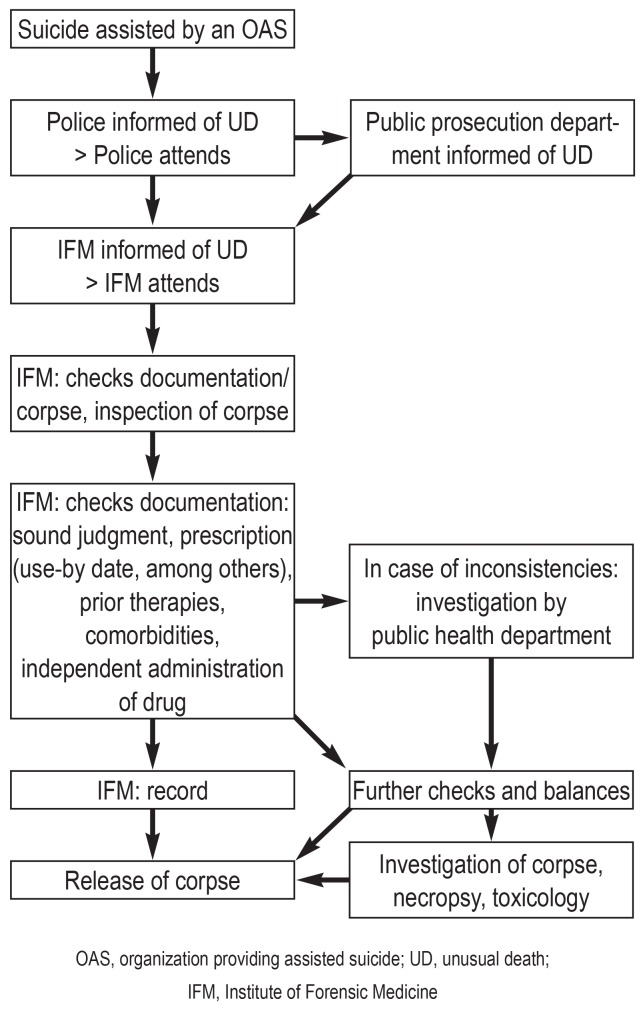

Figure 1.

Documentation process of an assisted suicide

(example: Canton of Zurich)

Because of the cantonal sovereignty regarding the healthcare system, processes and procedures differ slightly between cantons. In the City of Zurich, assisted suicides are documented by forensic medicine doctors at Zurich’s Institute of Forensic Medicine, in some other cantons this is done by the public health officers (district medical officer, cantonal medical officer).

The responsibilities of the physician include confirming the dead person’s identity, the so-called legal inspection (inspection of the corpse by the medical officer) while considering the circumstances of the unequivocally independent ingestion of the lethal substance, checking for completeness and plausibility of documents submitted by the organization providing assisted suicide.

According to the cantonal guidelines of the Senior Public Prosecutor’s Office of the Canton of Zurich, which were ultimately adopted only by EXIT, the following have been regarded as standard since 2009:

– Confirmation of the diagnosis by a physician

– Soundness of judgment confirmed by a physician

– A prescription for the lethal medication

– Minutes documenting the process of the assisted suicide

– A suicide declaration signed by hand

– A membership pass

– A specification of costs from the organization.

Confirmation that the client was of sound judgment regarding their wish to die by suicide is particularly important.

If abnormalities are found on the dead body or the circumstances of the death are questionable (such as is the case, for example, if home made application instruments are found with a client whose neurological impairment would have made ingestion of the substance problematic/impossible) then any further possible forensic investigations (necropsy, toxicology) will be determined by the responsible Public Prosecutor’s Office.

In principle, no legal regulations exist that explicitly stipulate that assisted suicides should be exclusively performed by associations. At the time the study was being conducted, a total of six right-to-die organizations officially advertised their services in Switzerland (etable 1). Because assisted suicide is also allowed in persons who travel to Switzerland from other countries, Switzerland has become a destination for people internationally who wish to die by suicide (3).

eTable 1. Overview of organizations providing assisted suicide in Switzerland (2014 data).

| EXIT Deutsche Schweitz | EXIT A.D.M.D. | Ex International | Dignitas | Lifecircle/SPIRIT | Sterbehilfe Deutschland | |

| Founded | April 1982. Zurich |

January 1982. Western Switzerland |

1996. Berne |

May 1998. Forch |

November 2011. Basel |

July 2012. Zurich |

| Members to 2014 (approx) |

80 000 | 20 500 | 800 | 7000 | Not available | 310 |

| Membership | >18 years of age. Swiss residents | >20 years of age. _Swiss residents | People over the age of consent worldwide | People over the age of consent | Natural and legal persons | People over the age of consent resident in CH or Germany |

| Assisted suicide (AS) in: |

– Hopeless prognosis – Unbearable pain – Intolerable impairments/disabilities | – Genuine. repeatedly expressed desire for AS – Incurable illness with a poor prognosis – Permanent invalidity – Unbearable physical or mental suffering | – Incurable disease – Intolerable impairment/_disability or polymorbidity | – Terminal illness – Unbearable pain – Intolerable impairments/disabilities | – Incurable diseases – Severe impairments/disability – Need for nursing care – Patient “vegetates” – Reduced quality of life owing to disorders that won’t lead to death in the forseeable future | – Hopeless prognosis – Unbearable impairments – Intolerable disabilities |

| Membership fees (annual fee if not stated otherwise) | 45 CHF or 900 CHF (LTM) |

35 CHF (retired clients); 45 CHF |

Free or voluntary donations | 80 CHF (200 CHF admission fee) |

50 CHF or 1000 CHF (LTM) |

200 Euros or 2000 Euros (LTM) |

| Number of AS/2014 | 583 | 175 | ca 20 | ca 200 | Not available | ca 30 (in Germany) |

| Costs of AS | None after 3 years’ membership. otherwise 1100– 3700 CHF | None | ca 6000 CHF | 10 500 CHF | None | None |

Deutsche Schweiz. German-speaking part of Switzerland; CH. Switzerland; CHF. Swiss Francs; y. years; LTM. lifetime membership

Switzerland has no central register for cases of assisted suicide, and the Swiss Federal Statistical Office has documented such deaths as a separate category only since 2011. The studies available so far had small sample sizes and were conducted in individual cantons over short time periods (4– 6). So as to reflect the time period from 1985 to 2014 on the basis of as broad a base of data as possible and to provide a Swiss-wide overview, a relevant research project was included in the national research program (NFP 67 end of life). Since Switzerland’s institutes of forensic medicine are in some cantons involved by the police to help with postmortem investigations, and since they therefore obtain documents from organizations providing assisted suicide, most of the relevant information is archived by the institutes. Forensic medicine is not deployed in all cases of assisted suicide; about half are investigated by public health officers. Whether ultimately all cases of assisted suicide are actually reported to the police cannot be verified. As the majority of those seeking assisted suicide who have traveled in from other countries were taken care of by the organization Dignitas, which is headquartered in the Canton of Zurich, and as an agreement is in place that the local institute of forensic medicine investigates these cases, it was possible to document most of them.

In addition to legal and professional legal regulations, the Federal Court of Switzerland reached a decision in 2006 (7), which affected the practice of assisted suicide (8). This decision made the hitherto valid guidelines of the Swiss Academy of Medical Sciences (SAMW) mandatory at the federal level. Standardizing the process rules by requiring the provision of information/education, documentation, and, where appropriate, neurological-psychiatric expert opinions from the organizations providing assisted suicide reflects a minimal consensus. The physician involved is under obligation to document that s/he has carefully ruled out impaired judgment. Dementia and mental disorders dominate the neurological-psychiatric conditions that may need to be evaluated by expert opinion in individual cases.

Further requests for the legal standardization of the process in view of differences between cantons and different organizations providing assisted suicide have so far not been granted by the political institutions (federal government, parliament). This adds more importance to the question of the extent to which the minimal consensus has been adhered to in practice and which control mechanisms could ensure this. All this becomes even more of a hot topic because of the increasing number of assisted suicides, which presents the participating organizations and the government authorities, as well as institutions that are involved (for example, old people’s homes and nursing homes) and practicing doctors (4, 7) with relevant challenges. Last but not least, results from epidemiological studies show that a proportion of the risk factors for assisted and conventional suicides are identical (5, 6, 8, 9). Our study builds on earlier studies (5, 10, 11) but documents especially more recent trends. The study also analyzes potential effects of the 2006 decision of the Federal Court of Switzerland.

Methods

For the study, all deaths after assisted suicide that had been investigated by Swiss institutes of forensic medicine were recorded on the basis of the archived case files in the institutes. The time period covered by the study comprised the years 1985–2013; at the Institute of Forensic Medicine in Zurich the period through June 2014 was also included. The complete data set includes deaths of Swiss residents, which are also registered in the cause of death statistic of the Swiss Federal Statistical Office, as well as cases of persons domiciled outside Switzerland, which would otherwise have been documented exclusively in the police statistics of the cantons. The documents handed over to the institutes of forensic medicine by the police or organizations providing assisted suicide on the occasion of (external) examinations of the corpse and postmortem examinations were analyzed by using a data entry form that was specially conceived for the study. The data entry form included:

Items about the type of forensic investigation (external inspection/necropsy);

Sociodemographic variables (age, sex, marital status, occupation, etc);

Details on the procedure/process of the assisted suicide (application form of the suicide drug, number and quality of the submitted medical documents, letter declaring the motivation, etc);

Details of underlying diseases/disorders (medical diagnoses from the documents submitted by the organizations providing assisted suicide); and

Details of diseases and motives for wishing to die, as written down by the deceased.

The collected data came exclusively from the documents made available by the organizations providing assisted suicide, which had been archived in the institutes of forensic medicine. Archiving of documents was done differently owing to the different approaches taken by different cantons.

The completed data entry forms were read into a terminal, automatically transferred into the statistics software package SPSS 22, and statistically evaluated. In addition to trends over time, differences between the different organizations providing assisted suicide were shown in relation to approach taken, written documentation, and clientele.

The Swiss Confederation’s expert committee for doctors’ professional secrecy/confidentiality approved the study. The data were collected in an anonymized form.

Results

Overview

Our data cover 3666 cases of assisted suicide, 2191 (59.8%, 95% confidence interval [58.2; 61.4]) of which occurred in women and 1475 (40.2%, [38.6; 41.8]) in men, all aged between 18 and 105 years. The data included 1979 (54%, 52.4 to 55.6) Swiss residents and 1687 (46%) persons domiciled outside Switzerland. Among the latter group, German citizens were the largest group (n = 909), followed by Brits (n = 251), and French citizens (n = 184). The first group (“Swiss residents”) was accounted for almost completely by EXIT (97.7% of all 1420 of EXIT’s cases of assisted suicide) and A.D.M.D. (99.8% of all of A.D.M.D.’s cases of assisted suicide). This group constituted the minority for Dignitas (4.9% of 1607 cases) and Ex International (5.1% of 117 cases); these organizations were approached mainly by persons from other countries.

The median age of death was 73.0 years (mean 71.2 [70.7 to 71.6] years). In Swiss residents, the median was notably higher than in persons resident outside Switzerland (77 versus 68 years). The age difference between men and women was trivial (median 72 versus 74 years).

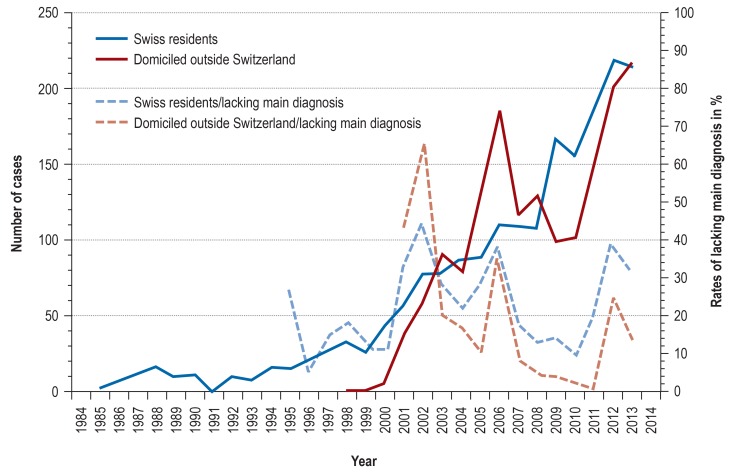

Between 1985 and 1995 the number of cases of assisted suicide amounted to barely more than 10 cases per year; the increase accelerated afterwards. The trend over time can be divided into two phases. Up to the turn of the millennium, a slow upwards trend was observed, with up to 30 cases per year documented by the institutes of forensic medicine. Afterwards, the number of assisted suicides in Swiss residents increased rapidly. What was new—also since the turn of the millennium and at a similar order of magnitude—were assisted suicides among persons domiciled outside Switzerland. In these, an extraordinary peak was noted in 2006, and a slowdown in growth in 2009/10. Up to 2013, the number of assisted suicides in each of the two groups reached more than 200 cases annually (figure 2).

Figure 2.

Trends in assisted suicide in Switzerland; cases documented by the institutes of forensic medicine by place of residence (left y-axis; drawn through lines); trends in lacking information on main diagnosis by place of residence (right y-axis, dotted lines)

Approach and documentation

In Swiss residents, most assisted suicides took place within their own homes (73.8% [71.8; 75.7]); 15.9% [14.4; 17.5] took place within the premises of the organization, and 8.5% [7.3; 9.8] in other institutions (old people’s homes, nursing homes, hospitals). In non-Swiss residents, more than 98% [97.5; 98.7] of assisted suicides took place in rooms made available by the organization providing assisted suicide.

The documents made available by the organizations providing assisted suicide for the purpose of verifying deaths are summarized in the Table for the four larger organizations; the period before 2006 is compared with that after 2006 (judgment by the Federal Court of Switzerland). After 2006, documents confirming the medical diagnosis and the patient’s power of judgment (whether the patient was of sound judgment) were available for far more cases—more than 95% of cases for EXIT and Dignitas. This means that a clear improvement has been achieved in terms of transparency (consistency between the medically fixated diagnosis and the written comments of those affected). This trend was also noted for the remaining organizations providing assisted suicide. However, in the case files documenting assisted suicide in the institutes of forensic medicine, signed suicide declarations (37–97%, on the basis of the available data) and sodium pentobarbital (NaP) prescriptions (range 9–99%) were lacking to a not insubstantial degree. As in confirmations of patients’ sound judgment, it tended to be the smaller organizations that had gaps in their documentation (table).

Table. Documentation of individual steps in the process of assisted suicides in Switzerland. by organization providing assisted suicide. up to and after 2006; reported as % [95% confidence intervals].

| EXIT Deutsche Schweiz [German-speaking Switzerland] |

Dignitas | EXIT A.D.M.D. | Ex International | |||||

| Up to 2006 | After 2006 | Up to 2006 | After 2006 | Up to 2006 | After 2006 | Up to 2006 | After 2006 | |

| Basic information*1 | ||||||||

| Diagnosis medically confirmed | 74.9 [71.4; 78.3] |

96.4 [95.0; 97.6] |

99.0 [98.1; 99.7] |

99.0 [98.4; 99.5] |

90.2 [84.4; 95.4] |

91.3 [88.1; 94.2] |

100.0 [-] |

86.0 [78.6; 92.7] |

| Confirmation that the patient is of sound judgment *2 | 50.3 [46.2; 54.3] |

95.5 [93.9; 96.9] |

85.0 [82.1; 87.9] |

97.9 [97.0 to 98.8] |

26.8 [18.5 to 34.7] |

71.6 [66.6 to 76.1] |

75.0 [56.0 to 91.3] |

84.9 [77.2 to 91.6] |

| NaP prescription | 65.5 [61.8 to 69.3] |

98.2 [97.2 to 99.0] |

99.3 [98.6 to 99.8] |

99.3 [98.7 to 99.8] |

3.3 [0.7 to 6.7] |

9.0 [6.2 to 12.0] |

87.5 [72.2 to 100.0] |

76.3 [68.0 to 85.1] |

| Suicide declaration signed by hand | 76.4 [72.8 to 79.8] |

68.7 [65.3 to 71.8] |

97.2 [95.8 to 98.4] |

92.9 [91.4 to 94.5] |

82.9 [76.2 to 89.5] |

75. [70.7 to 79.9] |

58.3 [37.5 to 78.6] |

37.6 [28.1 to 46.8] |

| Time protocol for the process of the assisted suicide | 88.3 [85.7 to 90.9] |

95.4 [94.0 to 96.8] |

99.0 [98.1 to 99.7] |

94.5 [93.0 to 96.0] |

95.9 [91.8 to 99.2] |

96.1 [94.0 to 98.0] |

95.8 [85.0 to 100.0] |

83.9 [75.5 to 91.2] |

| Neurological-psychiatric expert opinion in % of all cases | 2.7 [1.4 to 3.9] |

18.8 [16.3 to 21.4] |

3.0 [1.8 to 4.3] |

22.2 [19.5 to 24.8] |

4.1 [0.8 to 7.7] |

5.1 [2.9 to 7.4] |

4.2 [0.0 to 14.3] |

12.9 [6.6 to 19.8] |

| Further information | ||||||||

| Date at which the assisted suicide procedure was initiated | 22.9 [19.7 to 26.6] |

58.0 [54.7 to 61.2] |

0.2 [0.0 to 0.5] |

3.2 [2.2 to 4.4] |

55.3 [45.9 to 64.1] |

35.7 [31.0 to 40.7] |

0.0 [-] |

40.9 [30.7 to 49.5] |

| Police report | 89.2 [86.7 to 91.7] |

61.9 [58.5 to 65.3] |

98.5 [97.4 to 99.3] |

79.3 [76.8 to 81.6] |

59.0 [50.0 to 67.9] |

18.5 [14.6 to 22.7] |

91.7 [80.0 to 100.0] |

9.7 [4.0 to 16.0] |

*1 The selection of the most important documentation reflects the agreement between the Senior Public Prosecutor’s Office of the canton of Zurich canton and EXIT

*2 Confirmed by a doctor. no longer than 6 months before

Deutsche Schweiz. German-speaking part of Switzerland; NaP. sodium pentobarbital

Differences in approach were noted also for details relating to timing—for example, in terms of when the process was started by the respective organization providing assisted suicide (table). Also of note, but more easily explained with the circumstances: for Dignitas and Ex International, which have their main focus on clients from abroad who wish to die, the time period between obtaining the NaP prescription and the actual undertaking of the assisted suicide was 0–1 days in three quarters of cases, whereas for EXIT and A.D.M.D., the same lower three quarters of all cases of assisted suicide covered a time period of up to 35 days.

Medical diagnoses according to the documentation of the organizations providing assisted suicide

The documents of the organizations providing assisted suicide included one diagnostic category in 52.2% [50.5; 53.9] of cases, two in 23.5% [22.1; 24.9], three in 15.0% [13.8; 16.2], and four or more categories of diagnoses or more (missing: 29). One single diagnosis was documented mostly for malignant neoplasms (ca 62%) and for neurological disorders (ca 48%), with no further differentiation in this context. Furthermore, two crucial differences are striking: firstly, the rate of cases of assisted suicide for which only one diagnosis category had been documented fell from initially 61.9% [59.3; 64.2] to 47% [45.0; 49.3] after 2006. Secondly, among cases of assisted suicide in Swiss residents (or cases documented by EXIT or A.D.M.A.), 46.7% [42.5; 47.0] had only one category of diagnosis, whereas among patients domiciled in other countries (or those documented by Dignitas and Ex International) the rate was 59.7% [57.4; 62.0].

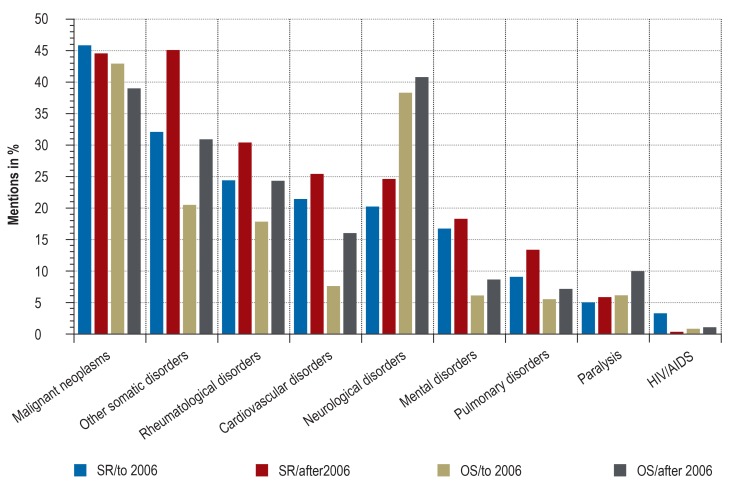

Figure 3 provides an overview of the diagnoses. Malignant neoplasms were the most common category, with 43.2% [41.6; 44.9] mentions. Generally, after 2006 an increase in (co-) diagnoses was observed across all diagnoses, whereas the proportion of malignant neoplasms remained stable or even fell slightly. In cases of assisted suicide among Swiss residents, other somatic illnesses were named in second place after malignant neoplasms; mostly these were documented as a co-diagnosis (in 90% of all documented cases). In cases of assisted suicide in persons domiciled outside Switzerland, neurological disorders were most common, apart from malignant neoplasms (at 40%). Further notable differences relate to cardiopulmonary disorders and mental disorders, which were all more common in Swiss residents (etable 2). Regarding mental disorders this is not immediately plausible when comparing these with documented suicide attempts in the medical history: in cases of assisted suicide among Swiss residents, this information was seen for 6.6% [5.6; 7.8], but it was more common in cases of assisted suicide among persons domiciled outside Switzerland, at 11.6% [10.1; 13.2].

Figure 3.

Diagnoses, by place of residence, up to and after 2006 (incl. multiple mentions)

SR, Swiss residents

OS, domiciled outside Switzerland

eTable 2. List of diagnoses in assisted suicide. total and differentiated by place of residence; multiple mentions possible.

| Total | Residence in Switzerland |

Residence outside Switzerland |

||||

| Disorders | N | % | n | % | n | % |

| Malignancies | 1571 | 42,9 | 890 | 45 | 681 | 40,4 |

| ENT (eg. thyroid cancer) | 117 | 3,2 | 61 | 3,1 | 56 | 3,3 |

| Gastrointestinal | 404 | 11 | 238 | 12 | 166 | 9,8 |

| Prostate | 200 | 5,5 | 136 | 6,9 | 64 | 3,8 |

| Lung | 209 | 5,7 | 118 | 6 | 91 | 5,4 |

| Breast | 242 | 6,6 | 117 | 5,9 | 125 | 7,4 |

| Skin | 61 | 1,7 | 37 | 1,9 | 24 | 1,4 |

| Leukemia | 33 | 0,9 | 21 | 1,1 | 12 | 0,7 |

| Ovaries/uterus/vagina | 120 | 3,3 | 47 | 2,4 | 73 | 4,3 |

| Other/not further specified | 345 | 9,4 | 191 | 9,7 | 154 | 9,1 |

| Heart | 693 | 18,9 | 473 | 23,9 | 220 | 13 |

| Coronary heart disease | 235 | 6,4 | 158 | 8 | 77 | 4,6 |

| Heart failure | 185 | 5 | 104 | 5,3 | 81 | 4,8 |

| Other/not further specified | 419 | 11,4 | 286 | 14,5 | 133 | 7,9 |

| Lung | 341 | 9,3 | 230 | 11,6 | 111 | 6,6 |

| COPD. emphysema | 226 | 6,2 | 154 | 7,8 | 72 | 4,3 |

| Other/not further specified | 137 | 3,7 | 88 | 4,4 | 49 | 2,9 |

| Paralysis | 251 | 6,8 | 107 | 5,4 | 144 | 8,5 |

| Vascular cause | 85 | 2,3 | 43 | 2,2 | 42 | 2,5 |

| Neurological cause | 77 | 2,1 | 27 | 1,4 | 50 | 3 |

| Other/not further specified | 98 | 2,7 | 41 | 2,1 | 57 | 3,4 |

| Rheumatological | 927 | 25,3 | 556 | 28,1 | 371 | 22 |

| Arthritis | 292 | 8 | 185 | 9,3 | 107 | 6,3 |

| Polyarthritis | 90 | 2,5 | 52 | 2,6 | 38 | 2,3 |

| Osteoporosis | 303 | 8,3 | 170 | 8,6 | 133 | 7,9 |

| Pain syndromes | 321 | 8,8 | 184 | 9,3 | 137 | 1,8 |

| Other/not further specified | 322 | 8,8 | 180 | 9,1 | 142 | 8,4 |

| Neurological | 1127 | 30,7 | 453 | 22,9 | 674 | 40 |

| Multiple sclerosis | 191 | 5,2 | 65 | 3,3 | 126 | 7,5 |

| ALS/motor neuron disease | 257 | 7 | 54 | 2,7 | 203 | 12 |

| Parkinson’s disease | 156 | 4,3 | 67 | 3,4 | 89 | 5,3 |

| Alzheimer’s disease | 53 | 1,4 | 24 | 1,2 | 29 | 1,7 |

| Other/not further specified | 523 | 14,3 | 267 | 13,5 | 256 | 15,2 |

| Psychiatric | 482 | 13,1 | 352 | 17,8 | 130 | 7,7 |

| Psychosis | 16 | 0,4 | 9 | 0,5 | 7 | 0,4 |

| Depression | 321 | 8,8 | 236 | 11,9 | 85 | 5 |

| Bipolar disorder | 12 | 0,3 | 7 | 0,4 | 5 | 0,3 |

| Other/not further specified | 214 | 5,8 | 162 | 8,2 | 52 | 3,1 |

| Other | 1283 | 35 | 817 | 41,3 | 466 | 27,6 |

| HIV | 34 | 0,9 | 19 | 1 | 15 | 0,9 |

| Aids | 21 | 0,6 | 18 | 0,9 | 3 | 0,2 |

| Peripheral artery disease | 91 | 2,5 | 63 | 3,2 | 28 | 1,7 |

| Sight loss/blindness | 221 | 6 | 133 | 6,7 | 88 | 5,2 |

| Weakness | 94 | 2,6 | 70 | 3,5 | 24 | 1,4 |

| Other/not further specified | 1096 | 29,9 | 686 | 34,7 | 410 | 24,3 |

When evaluating the diagnosis criteria, another question that arises is whether the increase in co-diagnoses (and, concomitantly, the decrease in single diagnoses) after 2006 reflects a structural effect—that is, whether it is associated with age, for example. A complementary multivariate analysis including age and sex showed, however, that adjusting for these most important confounders does not alter the results (etable 3).

eTable 3. Linear regression with the dependent variable “sum of diagnosis categories” and the independent variables sex, age (two categories), and time point (before or after the 2006 decision of the Swiss Federal Court) *1.

| B | Standard error | 95% Wald confidence interval | Hypothesis test | |||||

| Lower | Upper | Wald chi square | df | Sig. | ||||

| Sex | Men | −0.069 | 0,0343 | −0.136 | −0.002 | 4,059 | 1 | 0,044 |

| Women | 0*2 | – | – | – | – | – | – | |

| Time point | Before 2006 | −0.238 | 0,0349 | −0.306 | −0.170 | 46,625 | 1 | 0 |

| After 2006 | 0*2 | – | – | – | – | – | – | |

| Age | Up to 71 years of age | −0.632 | 0,0337 | −0.698 | −0.566 | 352,26 | 1 | 0 |

| Older than 71 years | 0*2 | – | – | – | – | – | – | |

*1 Calculated using the GENLIN procedure in SPSS 22.0

*2 Reference value. set at 0

On the basis of the information on which disease group dominated the medical documentation—somatic illness that would lead to death within the foreseeable future, long term somatic illness, long term mental illness—it was possible to reconstruct a rough classification of the main diagnoses. A primarily somatic diagnosis dominated, at 73%; the category “will lead to death in the foreseeable future” came in second place, at 23%. Less than 4% were accounted for by a mental diagnosis (alone or in combination with somatic disorders) (etable 4).

eTable 4. Main medical diagnosis, across all cases of AS and differentiated by place of residence, with 95% confidence intervals.

| 95% confidence interval | |||||

| N | % | Lower | Upper | ||

| All AS | Will lead to death after a short time | 667 | 23,3 | 21,8 | 24,9 |

| Long term somatic illness | 2083 | 72,9 | 71,2 | 74,5 | |

| Mental illness only | 61 | 2,1 | 1,6 | 2,7 | |

| Mental and somatic disorder/illness | 46 | 1,6 | 1,2 | 2,1 | |

|

Residence in Switzerland |

Will lead to death after a short time | 403 | 27,5 | 25,3 | 29,8 |

| Long term somatic illness | 980 | 67 | 64,4 | 69,2 | |

| Mental illness only | 43 | 2,9 | 2,1 | 3,8 | |

| Mental and somatic disorder/illness | 37 | 2,5 | 1,8 | 3,4 | |

|

Residence outside Switzerland |

Will lead to death after a short time | 264 | 18,9 | 16,8 | 21 |

| Long term somatic illness | 1103 | 79,1 | 77 | 81,4 | |

| Mental illness only | 18 | 1,3 | 0,7 | 2 | |

| Mental and somatic disorder/illness | 9 | 0,6 | 0,2 | 1,1 | |

Discussion

This is the first study to provide a chronological procedural overview of the dynamics and trends in assisted suicide since the first officially documented “assisted suicide” provided by an assisted suicide organization in Switzerland. The different approaches/procedures of the different organizations providing assisted suicide were documented before and after the 2006 decision of the Swiss Federal Court. Initially the situation was shaped by a small number of organizations that were categorized by their clientele—that is, Swiss residents or persons domiciled outside Switzerland. The Federal Court promoted the already existing professionally mandatory guidelines for physicians at the federal level. This affected not only the physicians involved but also the organizations providing assisted suicide, which had been practicing under their own responsibility up to that point.

The results spell out that approaches/procedures did not adhere to a consistent quality standard during the study period, in spite of an existing regulatory framework (box 1). In our assessment, this has not changed in the years after 2014, with the legal framework remaining unchanged (box 2). Whether, to what extent, and at what quality the necessary documents were included in the investigation of a death differed not only between cantons but also between organizations. Since 2006 the attempts to introduce a more uniform approach has been reflected in the number and type of submitted documents. However, differences remain between the individual organizations providing assisted suicide, which cannot easily be explained with their different clienteles from within or outside Switzerland. The data presented in this study make it obvious that the smaller organizations were affected by these differences to a greater extent than the two large ones (EXIT, Dignitas).

BOX 1. Nationwide regulations in Switzerland that have affected the practice of assisted suicide over time.

1942 – Criminal/Penal Code Art. 115: assisted suicide for non-selfish reasons is not specifically prohibited as long as certain conditions are met.

1951 – Narcotics law Use of the lethal drug sodium pentobarbital (NaP)

1982 – Foundation of the first organizations providing assisted suicide

2004 – Medical-ethical guidelines for doctors from the Swiss Academy of Medical Sciences (SAMW)

The patient’s illness justifies the assumption that the end of their life is near.

Alternative options for help were discussed and applied where desired.

Confirmation that the patient is of sound judgment (Civil Code Art.16)

Autonomy, thorough consideration, and the longstanding desire to die by suicide are all confirmed.

2006 – Decision of the Federal Court

Personal examination by a physician

Checking whether the patient’s judgment is sound

Diagnosis and indication established, and information/education provided by a physician

Assisted suicide in mental disorders should be granted only with extreme caution, expert opinion from psychiatric specialist is compulsory

2007 – Criminal Procedure Code Art. 253: unusual deaths

BOX 2. Current trends and requirements.

Since nothing has changed in the processes/procedures of assisted suicide since 2014, no reliable reporting statistic can be assumed for Switzerland even under current conditions.

The great importance of a functioning and consistent regulation follows from the newly formulated 2018 guidelines of the Swiss Academy of Medical Sciences, which reflect the practice, which now list “intolerable/unbearable suffering” as the prerequisite for assisted suicide (13, 14). Michael Barnikol of the FMH, the professional association of Swiss physicians, has summarized this as follows: “While the old guidelines permit assisted suicide only if ‘the patient’s illness [justifies] the assumption that the end of their life is near,’ assisted suicide is supported by item 6.2.1 of the new guidelines and permitted if ‘a patient’s symptoms of illness and/or functional impairments cause the patient unbearable suffering.’ The revision of the guidelines therefore extends the applicability of assisted suicide to a not insubstantial degree, which throws up numerous legal and practical questions.”

The new guidelines are not uncontroversial within the FMH. As far as we are aware, even before their publication, all involved specialist associations, including Ipsilon, the Swiss suicide prevention umbrella organization (16), were in favor of consistent and functioning regulations regarding assisted suicide. They will do so with even greater vigor forthwith.

Among the practical questions that need a plausible and urgent solution is a manner of documentation of assisted suicide that is guided by uniform regulation. In principle, the question arises what the preferable option might be: further regulation or the introduction of a central registration office. Although many issues may seem trivial at first glance, they are not trivial at second glance: see for example the issue of uniform approaches to how an affected person may be able to ingest the lethal drug by themselves (for example, patients with advanced amyotrophic lateral sclerosis).

Numerical trends in assisted suicide in Switzerland further contribute to the urgency with which uniform and transparent solutions are needed. Since the first documented case in 1985, the case numbers of assisted suicide remained very low for a long time, and the topic therefore remained marginal. With the new millennium, this state of affairs changed. In the current decade, the number of cases of assisted suicide in Swiss residents rose from 500 in 2012 to almost 1000 in 2016 (see [17] and recent data from the Swiss Federal Statistical Office, Neuenburg/Neuchâtel). This means that the numbers of cases of assisted suicide now almost match those of conventional suicide (slightly more than 1000 cases; by way of a comparison, the number of all deaths was 65 000 per year at the last count). Cases of assisted suicide in persons domiciled outside Switzerland reached an order of magnitude of 250 per year over the past decade. Similar increases have been posted in the membership numbers of the largest organization providing assisted suicide, EXIT, which currently stands at 120 000 members.

Apart from the differences that are obvious from the statistic, further specific procedural particularities and deficiencies in the documentation practice existed, which became obvious during data extraction from the case files. The documents contained no information regarding consent to or rejection of an application for assisted suicide, no criteria or working instruments that were proved to have been used demonstrably by the organizations providing assisted suicide in the case of such investigations. From the case files alone it was not possible to understand how an organization providing assisted suicide checked the fundamental principles in the individual case scenario and on which basis it ultimately reached a decision. From the perspective of the institutions tasked with investigating deaths, this still prevailing documentation practice meant insufficient transparency regarding the approach/process of the organizations providing assisted suicide. In spite of the postmortem examinations undertaken by the prosecuting authorities, the question remains unanswered in many cases as to how it was ensured in the individual case whether the fundamental principle had been met, that a person had been of sound judgment regarding their longstanding and thoroughly considered wish to die. In these investigations, the authorities rely in principle on the data found in the supporting documentation submitted by the organizations providing assisted suicide. Costly screenings of all cases of assisted suicide are deemed to be impossible to conduct, for organizational and financial reasons. Ultimately the crucial questions cannot be answered postmortem, not even by necropsy—such as those of sound judgment, the thoroughly considered wish to die, a poor disease prognosis, or an illness/disease beyond treatment.

Limitations

This study used data from the institutes of forensic medicine in Switzerland and therefore provides information about most cases of assisted suicide in persons domiciled outside Switzerland, but about less than half of cases of assisted suicide in Swiss residents. Suicides assisted by public health officers not working in forensic medicine are therefore not included in this study. Furthermore, the researchers studied data only up to the year 2014. Basically the question remains unanswered whether all cases of assisted suicide were really documented as unusual deaths and reported to the police. According to the Federal Statistical Office, the evaluated death certificates do not allow any conclusions about this either. Any reporting system—however official and legally compulsory it may be—always depends on the support of those reporting relevant information. A quality assurance process that takes recourse ex post to non-standardized documentation that has been completed in different ways will therefore have gaps in the data and all sorts of imponderabilities.

Key Messages.

Since 1985, assisted suicides have been offered by organizations providing assisted suicide in Switzerland.

With the new millennium, cases of assisted suicide have risen continuously, among Swiss residents but also residents of other countries (mainly Germany), who travel to Switzerland because they want to die by assisted suicide.

The most common reasons for wanting to die were malignancies (among Swiss residents) or neurological disorders (among residents of other countries), followed directly by age-related functional impairments, for example sensory loss (sight, hearing)

The 2006 decision of the Swiss Federal Court made the guidelines of the Swiss Academy of Medical Sciences mandatory, not only for physicians but also for organizations providing assisted suicide.

The data analyzed in this study reflect, on the one hand, the visible attempts to develop more uniform procedures/processes and improved documentation of the practice of organizations providing assisted suicide and, on the other hand, the fact that processes and procedures did not follow a general quality standard, in spite of an existing regulatory framework.

Acknowledgments

Translated from the original German by Birte Twisselmann, PhD.

Acknowledgment

This study is based on data collected by the following institutes of forensic medicine in Switzerland: Basel, Bern, Chur, Lausanne, St Gallen, Zurich. The study would have been impossible to conduct without the commitment of the participating institutes and their staff.

Footnotes

Conflict of interest statement

Dr. Ajdacic-Gross is a member of EXIT, which provides assisted suicide—an immaterial conflict of interest. The remaining authors declare that no conflict of interest exists.

References

- 1.Emanuel EJ, Onwuteaka-Philipsen BD, Urwin JW, Cohen J. Attitudes and practices of euthanasia and physician-assisted suicide in the United States, Canada, and Europe. JAMA. 2016;316:79–90. doi: 10.1001/jama.2016.8499. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Brauer S, Bolliger C, Strub JD. Swiss physicians‘ attitudes to assisted suicide: A qualitative and quantitative empirical study. Swiss Med Wkly. 2015;145 doi: 10.4414/smw.2015.14142. w14142. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Gauthier S, Mausbach J, Reisch T, Bartsch C. Suicide tourism: a pilot study on the Swiss phenomenon. J Med Ethics. 2015;41:611–617. doi: 10.1136/medethics-2014-102091. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Schmid M, Zellweger U, Bosshard G, Bopp M. Swiss Medical End-Of-Life Decisions Study G: Medical end-of-life decisions in Switzerland 2001 and 2013: Who is involved and how does the decision-making capacity of the patient impact? Swiss Med Wkly. 2016;146 doi: 10.4414/smw.2016.14307. w14307. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Steck N, Junker C, Maessen M, et al. Suicide assisted by right-to-die associations: a population based cohort study. Int J Epidemiol. 2014;43:614–622. doi: 10.1093/ije/dyu010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Steck N, Zwahlen M, Egger M, Cohort SN. Time-trends in assisted and unassisted suicides completed with different methods: Swiss National Cohort. Swiss Med Wkly. 2015;145 doi: 10.4414/smw.2015.14153. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Schweizerisches Bundesgericht. Entscheide 2A.48/2006 und 2A.66/2006. www.bger.ch/ext/eurospider/live/de/php (last accessed on 11 June 2019) [Google Scholar]

- 8.Steck N, Egger M, Zwahlen M, Cohort SN. Assisted and unassisted suicide in men and women: longitudinal study of the Swiss population. Brit J Psychiat. 2016;208:484–490. doi: 10.1192/bjp.bp.114.160416. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Steck N, Junker C, Zwahlen M. Swiss National C: Increase in assisted suicide in Switzerland: did the socioeconomic predictors change? Results from the Swiss National Cohort. BMJ Open. 2018;8 doi: 10.1136/bmjopen-2017-020992. e020992. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Bosshard G, Ulrich E, Bar W. 748 cases of suicide assisted by a Swiss right-to-die organisation. Swiss Med Wkly. 2003;133:310–317. doi: 10.4414/smw.2003.10212. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Fischer S, Huber CA, Imhof L, et al. Suicide assisted by two Swiss right-to-die organisations. J Med Ethics. 2008;34:810–814. doi: 10.1136/jme.2007.023887. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Kovacevic A, Bartsch C. Suizidbeihilfe in der Schweiz. sozialpolitik.ch. 2017;1:1–11. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Schweizerische Akademie der Medizinischen Wissenschaften (SAMW) Umgang mit Sterben und Tod. Medizin-ethische Richtlinien. SAMW 2018. www.samw.ch/de/Ethik/Sterben-und-Tod/Richtlinien-Sterben-Tod.html (last accessed on 5 May 2019) [Google Scholar]

- 14.Hürlimann D. Umstrittene Suizidhilfe am Lebensende. Neue Zürcher Zeitung, 12.10.2018 [Google Scholar]

- 15.Barnikol M. Die Regelung der Suizidbeihilfe in den neuen SAMW-Richtlinien. Schweiz Ärzteztg. 2018;991:392–396. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Ipsilon. Positionspapier zur Sterbehilfe und Suizidbeihilfe. http://ipsilon.ch/de/aktuell/news.cfm (last accessed on 12 July 2019) 2017 [Google Scholar]

- 17.Bundesamt für Statistik BfS. Todesursachenstatistik 2014: Assistierter Suizid (Sterbehilfe) und Suizid in der Schweiz. Bundesamt für Statistik BfS. 2016 [Google Scholar]