This review summarizes current available evidence for the diagnosis and treatment of Merkel cell carcinoma, including surgery, radiotherapy, chemotherapy, and immunotherapy. This article also reports details of recent therapeutic advances and related implications for care in patients with advanced disease.

Keywords: Merkel, Epidemiology, Diagnosis, Treatment, Immunotherapy

Abstract

Merkel cell carcinoma (MCC) is a rare, aggressive, primary cutaneous neuroendocrine tumor that typically presents as an indurated nodule on sun‐exposed areas of the head and neck in the white population. Major risk factors include immunosuppression, UV light exposure, and advanced age. Up to 80% of MCC are associated with Merkel cell polyomavirus. About 50% of patients present with localized disease, and surgical resection with or without adjuvant radiotherapy is generally indicated in this context. However, recurrence rates are high and overall prognosis rather poor, with mortality rates of 33%–46%. MCC is a chemosensitive disease, but responses in the advanced setting are seldom durable and not clearly associated with improved survival. Several recent trials with checkpoint inhibitors (pembrolizumab, avelumab, nivolumab) have shown very promising results with a favorable safety profile, in both chemonaïve and pretreated patients. In 2017, avelumab was approved by several regulatory agencies for the treatment of metastatic MCC, the first drug to be approved for this orphan disease. More recently, pembrolizumab has also been approved by the U.S. Food and Drug Administration in this setting. Immunotherapy has therefore become the new standard of care in advanced MCC. This article reviews current evidence and recommendations for the diagnosis and treatment of MCC and discusses recent therapeutic advances and their implications for care in patients with advanced disease. This consensus statement is the result of a collaboration between the Spanish Cooperative Group for Neuroendocrine Tumors, the Spanish Group of Treatment on Head and Neck Tumors, and the Spanish Melanoma Group.

Implications for Practice.

Merkel cell carcinoma (MCC) is an uncommon aggressive skin cancer associated with advanced age, UV light exposure, and immunosuppression. Up to 80% are associated with Merkel cell polyomavirus. MCC is a chemosensitive disease, but tumor responses in the advanced setting are short‐lived with no long‐term survivors. Recent clinical trials with immune checkpoint inhibitors (i.e., pembrolizumab, avelumab, nivolumab) have shown promising results, with avelumab becoming the first drug to receive regulatory approval for this orphan indication. Further follow‐up is needed, however, to define more adequately the long‐term benefits of these drugs, and continued research is warranted to optimize immunotherapeutic strategies in this setting.

Introduction

Merkel cell carcinoma (MCC) is a rare cutaneous malignancy that was originally described as a “trabecular carcinoma of the skin” by Cyril Toker in 1972 [1]. Although it shares common features with Merkel cells of the skin, the assumption that it is originated in these cells has been recently questioned. MCC pathogenesis is linked to Merkel cell polyomavirus clonal integration and exposure to UV radiation, the latter being associated with a high mutational burden. In addition, its incidence is significantly increased in immunosuppressed patients. All these together make MCC a suitable candidate for exploring immunotherapeutic approaches. Although surgery with or without adjuvant radiotherapy can be curative in some patients with early‐stage MCC, the proportion of patients with recurrent disease exceeds 40% and median survival of patients with advanced disease ranges from 6 to 9 months with best available cytotoxic chemotherapy [2], [3]. In this context, recent results reported for several immune checkpoint inhibitors have already changed the standard of care of this orphan and aggressive disease.

This article summarizes current available evidence for the diagnosis and treatment of MCC, including surgery, radiotherapy, chemotherapy, and immunotherapy. This review also discusses in detail recent therapeutic advances and their implications for care in patients with advanced disease. This consensus statement is the result of a collaboration between the Spanish Cooperative Group for Neuroendocrine Tumors (GETNE), the Spanish Group of Treatment on Head and Neck Tumors (TTCC) and the Spanish Melanoma Group (GEM).

Epidemiology of MCC

The incidence of MCC has steadily increased over the past 3 decades (by 333% from 1986 to 2011 according to the Surveillance, Epidemiology, and End Results registry data), in part due to improved diagnostic techniques and clinical awareness, but likely also as a consequence of the progressive aging of the population in developed countries and the higher prevalence of some known risk factors such as T‐cell immune suppression. Nevertheless, it continues to be an infrequent disease, with reported annual incidence rates that range from 0.13/100,000 inhabitants in some low‐prevalence regions in Europe (i.e., Scotland or Eastern France) to 1.6/100,000 in countries with the highest prevalence such as Australia [4], [5], [6]. In the U.S., approximately 2,500 new cases are diagnosed per year [7]. MCC is more common in skin exposed to sunlight, advanced age, and male gender. MCC has a mortality rate three times greater than melanoma, and the overall survival (OS) rate at 5 years ranges from 30% to 64% [8], [9].

Etiopathogenesis of MCC

Although the etiology of MCC has not been fully elucidated, two main factors are closely related to the pathogenesis of this disease: the Merkel cell polyomavirus (MCPyV) and UV radiation exposure [10], [11]. Clonal integration of a polyomavirus in human MCC was first described in 2008 by Feng et al. This MCPyV is a double‐stranded DNA virus that has oncogenic potential in preclinical models via interaction with the p53 and Rb gene families [12]. MCPyV induces latent infections in immunocompetent hosts that may turn into MCC tumors in immunosuppressed patients. Up to 80% of MCC have MCPyV clonally integrated into tumor cells, and this condition is believed to be involved in direct viral carcinogenesis [12], [13]. Indeed, MCPyV‐positive MCC cell lines depend on viral oncogene expression for cell proliferation and survival.

Up to 80% of MCC have MCPyV clonally integrated into tumor cells and this condition is believed to be involved in direct viral carcinogenesis. Indeed, MCPyV‐positive MCC cell lines depend on viral oncogene expression for cell proliferation and survival.

Viral oncogenesis is mediated by the large and small T antigens of MCPyV, where large T antigens regulate the life cycle of virus and host cells (primary viral oncogene). In line with this, a recent clinical study, conducted in 68 patients with MCC and 82 controls, observed high levels of antibodies against MCPyV in patients with MCC, specifically in a subpopulation with better clinical outcome (i.e., in which progression‐free survival [PFS] was better in patients with high antibody titers, hazard ratio [HR] 4.6; p = .002) [14]. Nevertheless, the precise role of MCPyV in human MCC pathogenesis is currently under active investigation and debate.

The second main etiological factor involved in MCC development is exposure to UV radiation. As a result, MCC lesions are commonly located on sun‐exposed skin, and chronic UV exposure is likely involved in the increased incidence observed in people of advanced age [15]. A high mutational burden and a distinct mutational profile has been reported in virus‐negative, UV‐induced MCC. Other risk factors for MCC are predominantly linked to immunodeficiency conditions such as organ transplantation and the use of immunosuppressive therapy, HIV infection, and previous malignancies such as chronic lymphocytic leukemia, with a 34‐ to 48‐fold increased risk of developing MCC [16], [17]. In spite of that, it is important to point out that 90% of patients with MCC are immunocompetent.

Clinical Presentation, Diagnosis, and Staging of MCC

The diagnosis of MCC depends on both clinical and pathological factors. MCC typically presents as a rapidly growing, red‐violet, firm, and painless cutaneous nodule in sun‐exposed areas of the head and neck or upper limbs. The AEIOU acronym was proposed by Heath et al. [18] as a mnemonic rule to aid in diagnosis. Thus, an Asymptomatic skin nodule, rapidly Expanding in an Immunocompromised patient Older than 50 years and located in a UV‐exposed area, must be always be suspected of being MCC.

Once MCC is suspected, a complete examination of the skin and lymph nodes followed by a biopsy is mandatory. Three histological subtypes have been identified: (a) the intermediate type, characterized by basophilic cells and a high mitotic rate, is the most common type; (b) the small cell type, which is an undifferentiated subtype virtually indistinguishable from other microcytic tumors; and (c) the trabecular type, with well‐differentiated features, being the rarest [19]. Immunohistochemical (IHC) staining is mandatory, particularly CK20 and thyroid transcriptor factor 1 (TTF‐1), which provide the greatest sensitivity and specificity to diagnose MCC. CK20, with a classic para‐nuclear dot‐like pattern, is a very sensitive marker, being positive in 89%–100% of MCC cases. TTF‐1 is expressed in 83%–100% of small cell lung carcinomas but is consistently negative in MCC. Other IHC markers that may be useful for a differential diagnosis from other tumors that may mimic MCC, because they are not usually expressed in MCC, include CK7 for small cell lung cancer, S100 for melanoma, and leucocyte common antigen for lymphoma [19]. Two different mutational load patterns have been recently described: low mutational load pattern, which is associated with MCPyV‐positive patients, and high mutational load pattern with genetic signatures of UV damage in MCPyV‐negative patients. In a recent cohort study of 282 patients, patients with virus‐negative MCC had significantly increased risk of disease progression (HR 1.77) and death (HR 1.85) relative to patients with MCC with virus‐positive tumors [20]. MCCs that are not driven by MCPyV (∼20%), therefore, represent a more aggressive subtype that likely warrants closer clinical follow‐up.

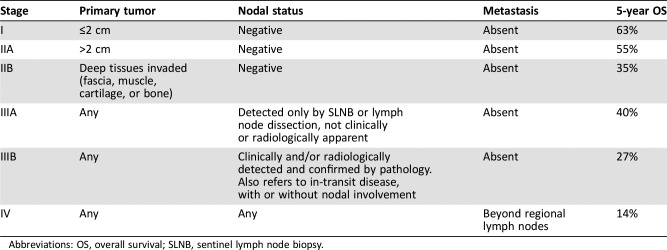

For adequate staging and prognostic stratification, the pathology report should always describe tumor size and depth (with Breslow thickness), mitotic rate, lymphovascular invasion, extracutaneous extension to muscle fascia, cartilage, or bone, and peripheral and deep margin status [21]. MCC can be staged according to the American Joint Committee on Cancer tumor, node, metastasis staging system (Table 1) [22]. Sentinel lymph node biopsy (SLNB) is recommended for accurate staging. Stages I–IIB refer to lymph node‐negative disease, whereas stage III refers to lymph node‐positive disease.

Table 1. American Joint Committee on Cancer staging of Merkel cell carcinoma [22].

Abbreviations: OS, overall survival; SLNB, sentinel lymph node biopsy.

When metastatic involvement beyond regional lymph nodes is observed, the disease is considered to be stage IV. The most common sites of metastasis are distant skin and lymph nodes, bone, and liver. The 5‐year survival rates range from more than 60% in patients with stage I disease to 13% in patients with stage IV disease, according to a recent study that analyzed the impact of disease stage on survival [22]. For practical purposes, descriptions of the different MCC stages are summarized in Table 1.

There is no clear consensus of what imaging techniques should be performed in initial staging or follow‐up of patients with MCC. However, because of their aggressive behavior, it is reasonable to carry out complementary radiological staging such as computed tomography (CT) scan or positron emission tomography‐CT scan to rule out distant metastasis.

Treatment of Patients with Early‐Stage MCC (N0, M0)

No prospective randomized trials have addressed the primary treatment of MCC, so all recommendations are based on retrospective studies. Surgical removal of the primary tumor is the main therapeutic approach in early stages of MCC. Wide excision is recommended, aiming to achieve 1–2‐cm clear margins when feasible [5], [23], [24]. However, surgical margins should be balanced with morbidity of surgery, and undue delay in proceeding to radiation therapy should be avoided [25]. Mohs micrographic surgery can be useful to ensure clear margins, particularly for in‐depth excision or when cosmetic results are important [26].

Postoperative radiotherapy should be administered to reduce the risk of local recurrence when certain risk factors are present, such as primary tumor >1 cm, head and neck location, positive or limited surgical margins, lymphovascular invasion, multiple involved lymph nodes, extracapsular node involvement, or immunosuppression [27], [28], [29]. Adjuvant radiotherapy has been shown to improve OS in patients with early‐stage MCC, according to the retrospective analysis of 6,908 cases from the National Cancer Database (NCDB) [30]. In this multivariate analysis, surgery plus adjuvant radiotherapy significantly improved OS compared with surgery alone in patients with stage I (HR 0.71, 95% confidence interval [CI] 0.64–0.80; p < .001) and stage II (HR 0.77, 95% CI 0.66–0.89; p < .001) MCC. The proposed dose of adjuvant radiotherapy is 45–50 Gy [31]. Radiotherapy should also be considered even when Mohs surgery has been performed [32]. When surgery is not feasible, definitive radiation therapy may be considered and can lead to long‐term tumor control [33].

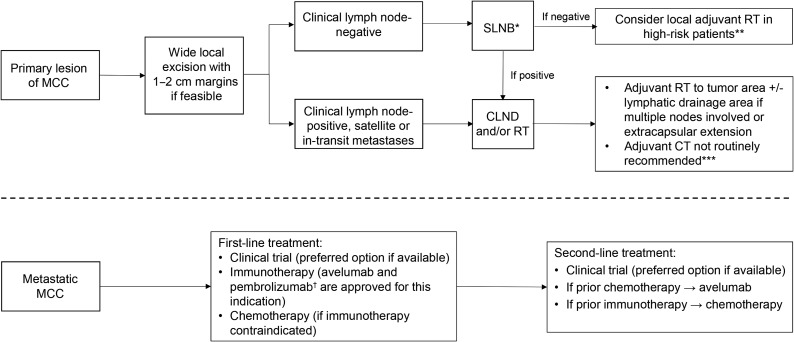

Additionally, SLNB and mapping are usually recommended in patients with early‐stage MCC [5]. SLNB should be performed intraoperatively during wide local excision, as surgery may alter lymphatic drainage. When SLNB is positive, lymph node dissection or definitive radiation therapy of the affected lymph node is indicated. If SLNB is negative, local treatment (radiotherapy and/or lymph node dissection) is only indicated when there is a high risk of recurrence due to other reasons (anatomic location, previous recurrences, etc.) [34]. The role of SLNB may be questioned when primary tumor size is larger than 2 cm, as radiotherapy is generally recommended in these patients regardless of node status. However, SLNB may still be still useful in this setting to finalize staging and to determine the patient's eligibility for clinical trials. In head and neck regions, the SLNB procedure is less reliable because of the complex and variable lymphatic drainage, which can lead to false‐negative results. If SLNB is not performed because of these difficulties, prophylactic radiotherapy or lymph node dissection should be considered [24]. Other alternatives such as adjuvant systemic treatment with chemotherapy or immunotherapy cannot be recommended at this time in node‐negative patients (Fig. 1) [35].

Figure 1.

Treatment algorithm for patients with Merkel cell carcinoma.

*If SLNB is not feasible or reliable (i.e., head and neck region), prophylactic RT or CLND should be considered; **High‐risk patients: tumor >1 cm, lymphovascular invasion, immunocompromised host; ***Could be considered in very selected patients based on clinical judgement (four cycles of platinum plus etoposide would be recommended in these cases). †Pembrolizumab has only been approved by the U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA).

Abbreviations: CLND, complete lymph node dissection; CT, chemotherapy; MCC, Merkel cell carcinoma; RT, radiotherapy; SLNB, sentinel lymph node biopsy.

Treatment of Patients with Locally Advanced MCC (N‐Positive, M0)

Optimal standard treatment for patients with clinically or pathologically positive lymph nodes is not well established. Therapeutic options include complete lymph node dissection, definitive nodal radiation, or a combination of both (Fig. 1). The addition of radiotherapy following lymph node dissection is generally recommended if multiple nodes are involved or extracapsular extension is detected. Adjuvant chemotherapy should not be routinely administered because of the lack of survival benefit demonstrated so far, although its use may be considered in selected fit, high‐risk patients based on best clinical judgement [36]. Moreover, some concern exists regarding the potential immunosuppressive effects of chemotherapy in these patients as well as the fact that efficacy of immunotherapy is substantially lower in chemotherapy‐pretreated patients with advance disease [37], [38]. Finally, adjuvant immunotherapy is currently being explored in different trials, including pembrolizumab (NCT03712605), nivolumab (NCT03798639), or ipilimumab (NCT03798639), and may potentially become a standard of care in this setting in the near future.

However, evidence to support treatment recommendations in the adjuvant setting is weak, as most available data come from retrospective series or small, noncontrolled prospective trials that tested various chemoradiotherapy regimens in heterogenous patient populations [39]. Only two prospective nonrandomized trials have evaluated the role of adjuvant chemotherapy in at least a subgroup of patients with MCC with nodal involvement. The Trans‐Tasman Radiation Oncology Group (TROG) conducted the TROG 96:07 phase II trial to evaluate the administration of synchronous adjuvant radiotherapy (50 Gy) and chemotherapy (four cycles of carboplatin and etoposide) with curative intent in 53 patients with MCC at high risk of recurrence [40]. High risk was defined as primary tumors >1 cm in diameter and/or in‐transit or nodal metastases, gross residual disease, or local or regional recurrence following initial surgery without distant metastatic disease. With a median follow‐up of 48 months, the 3‐year OS for all patients was 76%. The presence of positive nodes was identified as the major factor influencing survival in the multivariate analysis, but it was not a significant influencing factor for locoregional control. The 3‐year OS for patients with lymph nodes affected was 66% compared with 93% in patients without lymph node involvement (p = .27). The most serious side effects of this treatment were severe neutropenia and febrile neutropenia, which occurred in 57% and 35% of patients, respectively. To further assess the potential benefit of adjuvant chemotherapy, results of the TROG 96:07 trial were compared with a historical control that consisted of 62 patients who would have been eligible for the TROG trial but were treated without chemotherapy. A lower incidence of locoregional and distant recurrences and a lower rate of cancer‐related and ‐unrelated deaths were observed in chemotherapy‐treated patients, although no statistically significant differences could be documented in disease‐specific survival or OS [36].

Clinical outcomes did not seem to be negatively affected by a more tolerable regimen evaluated in a second prospective trial conducted in a similar high‐risk MCC population (n = 18), which consisted of weekly carboplatin (area under the curve of 2) concurrently with radiotherapy (50 Gy) [41]. Following radiotherapy, three additional cycles of carboplatin plus etoposide were administered. Severe neutropenia was observed in seven patients (39%), but no patient developed febrile neutropenia.

The retrospective analysis of the NCDB conducted in 6,908 patients with stage I‐III MCC reported that neither adjuvant radiotherapy nor chemotherapy significantly improved or worsened survival of 2,065 patients with MCC with regional nodal involvement (HR 0.98, 95% CI 0.86–1.12; p = 0.80 and HR 0.97, 95% CI 0.85–1.12; p = .71, respectively) [30]. The authors concluded that these findings should not impact on the use of adjuvant radiotherapy in stage III patients, as survival in these patients is mostly driven by the presence of subclinical distant metastasis, and radiotherapy is usually indicated to improve loco‐regional disease control.

In contrast, another retrospective study did observe a survival benefit of adjuvant chemotherapy in certain subsets of patients with MCC. From 4,815 patients with high‐risk head and neck MCC registered in the NCDB, 2,330 patients received adjuvant chemoradiotherapy, 330 patients received adjuvant radiotherapy alone, 97 patients received adjuvant chemotherapy alone, and 1,995 patients were treated with surgery alone. The 5‐year OS in the overall population was 41%. Patients treated with postoperative chemoradiotherapy or radiotherapy alone achieved a better survival rate than patients treated with surgery alone (HR 0.62, 95% CI 0.47–0.81 and HR 0.80, 95% CI 0.70–0.92, respectively). Moreover, adjuvant chemoradiotherapy was associated with better OS compared with adjuvant radiotherapy in patients with MCC with positive surgical margins (HR 0.48, 95% CI 0.25–0.93), male sex (HR 0.69, 95% CI 0.5–0.94), or tumor size ≥3 cm (HR 0.52, 95% CI 0.3–0.9).

Treatment of Metastatic MCC (M1)

The management of patients with advanced disease should be individually tailored through a multidisciplinary tumor board. Participation in a clinical trial when available should be the preferred option. Standard treatment options in this setting include surgery in selected patients, radiotherapy, and systemic therapies including chemotherapy and immunotherapy (Fig. 1).

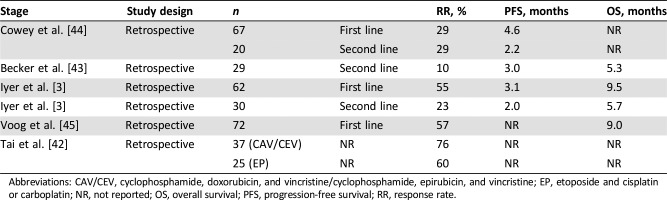

Chemotherapy

Although MCC is considered a chemosensitive disease and cytotoxic chemotherapy has been widely used in the management of metastatic MCC, its benefit remains uncertain. Nowadays, the main role of chemotherapy in MCC is to be administered in the metastatic setting and is mostly indicated to palliate symptoms [5], [24]. Small retrospective series have documented response rates of 29%–75% (Table 2) with cytotoxic agents such as platinum, etoposide, cyclophosphamide, vincristine, doxorubicin, and topotecan, either alone or in combination [3], [42], [43], [44], [45]. Responses are generally short‐lived, however, with median PFS of 3–4 months and median OS of less than 10 months. Current available data are not sufficient to assess whether chemotherapy improves PFS or OS in patients with advanced MCC. Moreover, chemotherapy is associated with significant toxicity, and there are some concerns regarding its potential to subsequently impair response to immunotherapy [46]. Because of this, and with the emerging role of checkpoint inhibitors, chemotherapy will likely be reserved for patients who are not candidates for immunotherapy (i.e., organ transplant recipients) or for those who have progressed on immunotherapy.

Table 2. Retrospective trials evaluating chemotherapy in patients with Merkel cell carcinoma.

Abbreviations: CAV/CEV, cyclophosphamide, doxorubicin, and vincristine/cyclophosphamide, epirubicin, and vincristine; EP, etoposide and cisplatin or carboplatin; NR, not reported; OS, overall survival; PFS, progression‐free survival; RR, response rate.

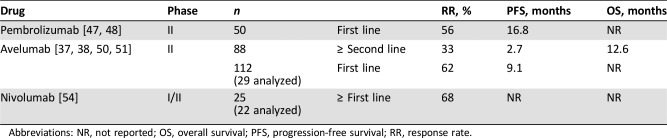

Immunotherapy

Immunotherapy with anti‐programmed cell death‐1 (PD‐1)/‐programmed death ligand‐1 (PD‐L1) antibodies has proved to be one of the most promising treatments for MCC (Table 3). Pembrolizumab, a humanized immunoglobulin (Ig)G4 monoclonal anti‐PD‐1 antibody, has been tested in patients with metastatic or recurrent locoregional MCC in a phase II trial (NCT02267603). Twenty‐six patients who had received no previous chemotherapy were enrolled in this study [47]. Objective tumor responses were observed in 56% of patients, and 16% of them were complete responses. At 6 months, 67% of patients had experienced no progression (95% CI 49–86). Median PFS was 9 months (95% CI 5 months to not reached). No difference in response rate was seen according to PD‐L1 expression. There was a trend toward a better response rate in MCPyV‐positive patients (62%) compared with MCPyV‐negative patients (44%), but given the small sample size, no definitive conclusions may be drawn. Grade 3 or 4 drug‐related adverse events (AEs) were observed in 15% of patients [47]. In a more recent update with 50 patients included and a median follow‐up of 14.9 months, tumor responses were observed in 56% of patients, of which 24% were complete responses. Response rate was very similar in both MCPyV‐positive patients (59%) and MCPyV‐negative patients (53%). Median PFS was 16.8 months (95% CI 5 months to not reached), and median OS has not been reached yet [48].

Table 3. Clinical trials evaluating immunotherapy in patients with Merkel cell carcinoma.

Abbreviations: NR, not reported; OS, overall survival; PFS, progression‐free survival; RR, response rate.

Avelumab is a fully human IgG1 anti‐PD‐L1 antibody that preserves antibody‐mediated cytotoxicity [49]. The efficacy of avelumab was investigated in the JAVELIN Merkel 200 phase II trial, which has two main parts (A and B). Part A enrolled 88 patients with metastatic MCC who had received at least one previous line of chemotherapy and had a life expectancy of at least 3 months [38], [50]. Patients included in this trial received a median of seven doses of avelumab (10 mg/kg) every 2 weeks until disease progression, unacceptable toxicity, or any other criterion for withdrawal. With a median follow‐up of 29.2 months (range: 24.8–38.1 months), 33% of patients achieved an objective response, including 10 complete responses (11%) and 19 partial responses (22%). Median time to response was 6 weeks, and median duration of response has not been reached yet. Responses were durable, with 93% lasting over 6 months, 74% lasting over 1 year, and 67% lasting over 2 years. Two‐year PFS and OS rates were 26% (29% at 1 year) and 36% (50% at 1 year), respectively. Median PFS was 2.7 months and median OS was 12.6 months, which is highly favorable for patients in this setting considering historical chemotherapy data (Table 2) [3], [44], [50], [51]. Durable antitumor efficacy was observed across all patient subgroups (MCPyV‐positive, MCPyV‐negative, PD‐L1‐positive, and PD‐L1‐negative patients), although there was a trend toward a greater response rate in patients with PD‐L1‐positive as compared with PD‐L1‐negative tumors (36% vs 19%, respectively) [38], [50].

Part B of the JAVELIN Merkel 200 phase II trial was planned to include 112 patients with metastatic MCC who have not received prior systemic treatment in the advanced setting. In a recent interim analysis, 39 patients who received at least one dose of avelumab were evaluated [37]. With a median follow‐up of 5.1 months (range: 0.3–11.3 months), patients had received a median of 6 doses of avelumab (range: 1–22). Preliminary efficacy was analyzed in 29 patients with at least 3 months of follow‐up. In this population, the overall response rate was 62% (95% CI 42–79), with four complete responses and 14 partial responses. When the efficacy analysis was performed in the 14 patients who had at least 6 months of follow‐up, the overall response rate increased to 71% (95% CI 42–92). Median duration of response has not been reached yet, and median PFS was 9.1 months, although these results are still immature because of limited follow‐up and analysis of patients. The Part B of JAVELIN Merkel 200 has recently completed enrollment.

The safety profile of avelumab as monotherapy was extensively evaluated in the pooled analysis of the JAVELIN phase I trial, which included 1,650 patients with various solid tumors, and the JAVELIN Merkel 200 phase II trial with 88 patients with advanced MCC [52]. AEs of special interest were immune‐related (IR) AEs and infusion‐related reactions (IRRs) that occurred on the day of drug infusion or 1 day after. At the time of the analysis, 1,738 patients analyzed had received a median of 6 doses of avelumab (range: 1–63), 287 of whom (17%) were still undergoing treatment, whereas 1,451 patients (83%) had discontinued the study because of disease progression (59%), AEs (11%), death (5%), consent withdrawal (5%), or other reasons (3%). Treatment‐related AEs leading to discontinuation were observed in 107 patients (6%), and the two most common were IRR (32 patients, 2%) and transaminase elevation (7 patients, ∼0%). Serious treatment‐related AEs occurred in 108 patients (6%), with the most common being IRRs (15 patients, 1%), pneumonitis (11 patients, 1%), and adrenal insufficiency (5 patients, ∼0%). Grade 3 or higher IR AEs were observed in 39 patients (2%), with the most common being hepatitis (13 patients), colitis (7 patients), and pneumonitis (7 patients). Four patients had a treatment‐related death according to the investigator due to autoimmune hepatitis, acute liver failure, respiratory distress, and pneumonitis. Focusing on the MCC population (n = 88), treatment‐related AEs (TRAEs) occurred in 70% of patients; the most common were fatigue (24%) and infusion‐related reactions (17%). Five grade 3 TRAEs were reported in four (5%) patients and included two patients with lymphopenia and three patients with laboratory abnormalities (elevated blood creatine phosphokinase, cholesterol, and liver aminotransferase). There were no grade 4 TRAEs or deaths related to treatment, although three deaths of unknown primary cause were reported. It was concluded that avelumab has a manageable safety profile, and both IRRs and IR AEs observed were generally of low grade, reversible, and rarely requiring a permanent study discontinuation.

Additionally, a real‐world experience with avelumab as second‐line treatment for patients with metastatic MCC in a global expanded access program (EAP) has been recently reported (NCT03089658). Interestingly, in contrast to the JAVELIN Merkel 200 trial, patients enrolled in this trial could have an Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group performance status ≥2, treated brain metastases, or immunosuppressive conditions. Of 272 potentially evaluable patients, 157 patient outcomes were provided (58%). The overall response rate was 52%, including 25% complete responses (three of them in immunocompromised patients). Durable responses were observed in both immune‐competent patients and immunocompromised patients. No new safety signals were identified in the EAP population [53].

Based on these encouraging results, the U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA) granted accelerated approval (March 2017) to avelumab (BAVENCIO; Merck Serono SA, Corsier‐sur‐Vevey, Switzerland) for the treatment of patients 12 years and older with metastatic MCC (this drug is part of an alliance between Merck KGaA and Pfizer). Soon thereafter, the European Medicines Agency (September 2017) and several regulatory agencies from other countries (i.e., Japan, Canada, Israel, Australia) also approved the use of avelumab as monotherapy for the treatment of adult patients with metastatic MCC. This is the first drug to be approved to treat this type of cancer. More recently (December 2018), the FDA also granted accelerated approval to pembrolizumab (KEYTRUDA; Merck Sharp & Dohme B.V., Haarlem, The Netherlands) for adult and pediatric patients with recurrent locally advanced or metastatic MCC.

Nivolumab, an IgG1 anti‐PD1 monoclonal antibody, has also been tested in a cohort of 25 patients with advanced MCC within the CheckMate 358 trial (NCT02488759) [54]. Preliminary results have reported an overall response rate of 68% in 22 evaluable patients. Responses occurred in both treatment‐naïve (71%) and ‐experienced (63%) patients, regardless of tumor MCPyV or PD‐L1 expression (Table 3). Expansion cohorts will evaluate combinations of nivolumab with ipilimumab or anti‐lymphocyte activation gene‐3 (LAG‐3).

Finally, there have been isolated case reports of responses to other immunotherapies, such as talimogene laherparepvec (T‐VEC) in patients with locally advanced disease [55], cytokines [9] or adoptive T‐cell therapy [56]. Consequently, various immunotherapy combinations are currently being investigated in clinical trials.

Other Targeted Therapies

A number of targeted therapies, including phosphoinositide 3‐kinase inhibitors, mammalian target of rapamycin (mTOR) inhibitors, and multikinase inhibitors, have been tested in limited numbers of patients with MCC, including case reports that documented clinical benefit with imatinib, pazopanib, cabozantinib or idelalisib, although a phase II trial with imatinib was prematurely halted because of lack of efficacy and pazopanib showed limited activity in another study (3 of 18 patients achieved a partial response) [9], [57], [58]. Other agents are currently being investigated in clinical trials in patients with advanced MCC, including cabozantinib, a c‐met and vascular endothelial growth factor receptor‐2 inhibitor (NCT02036476) or the mTOR inhibitors MLN0128 and everolimus (NCT02514824 and NCT00655655), among others.

Somatostatin analogs have also been explored in MCC, as tumor expression of somatostatin receptors has been documented in this disease. Octreotide was tested in an old phase II trial conducted in a heterogeneous patient population of different neuroendocrine tumors that included medullary thyroid cancer and MCC. The authors report satisfactory symptomatic and biochemical responses but disappointing activity in terms of tumor regression (overall response rate 3%). Responses to lanreotide have been reported in anecdotal cases, and a phase II trial is currently ongoing in patients with advanced MCC (NCT02351128) [9], [57]. Peptide‐receptor radionuclide therapy would also be worthwhile to be explored in this setting.

Unmet Medical Needs in MCC and Future Perspectives

The identification of the MCPyV and the UV‐induced hyper/ultra‐mutated genome in MCPyV‐negative tumors provided the clues to test immunotherapy with anti‐PD‐1/PD‐L1 blocking antibodies [12], [59].

The identification of the MCPyV and the UV‐induced hyper/ultra‐mutated genome in MCPyV‐negative tumors provided the clues to test immunotherapy with anti‐PD‐1/PD‐L1 blocking antibodies.

For the first time, a family of drugs has been demonstrated to provide clinical benefit in metastatic MCC in two single‐arm phase II trials [37], [38], [47], [50]. After these results, a phase III trial is unlikely to be pursued. The long‐lasting benefits observed with immunotherapy have never been documented for any of the cytotoxic drugs used for the treatment of MCC; thus, it would be unethical to compare anti‐PD‐1/PD‐L1 with chemotherapy in patients with metastatic MCC. Many different immunotherapeutic approaches are currently being actively explored, alone or in combination with other treatment modalities. Nevertheless, chemotherapy still plays a role in patients who are not suitable for immunotherapy (i.e., organ transplant recipients, patients on chronic immunosuppressive therapy for autoimmune diseases) and in patients who are resistant to or who have progressed following immunotherapy. However, some of these are not absolute contraindications for immunotherapy, as a subset of organ transplant recipients (e.g., kidney) or patients with non‐life‐threatening autoimmune disease may be considered for immunotherapy at the risk of losing the allograft or flare up of their disease. Best clinical judgment is advised in these settings.

Although it might seem that an important battle against this disease has been won, it should be noted that not all patients respond to this treatment and some will do so only briefly. In this context and taking into account that MCC is a chemotherapy‐ and radiotherapy‐sensitive disease, combining these approaches with anti‐PD‐1/PD‐L1 agents seems to be an area worthy of further exploration, both in patients with advanced disease and in the adjuvant setting. An additional challenge in the scenario of future trials will be to include a control arm in such a rare disease. Thus, pharmaceutical companies should join efforts and work together with basic researchers and translational clinicians, in order to identify new biomarkers as well as to design and conduct innovative clinical trials with these agents that have significantly changed the treatment scope of this deadly disease and may eventually increase the curative rate of MCC.

Conclusion

Progress made in our understanding of MCC pathogenesis and immunological background has led to the expansion of the treatment armamentarium for patients with MCC, with avelumab becoming the first drug to receive regulatory approval for this orphan indication. This significant milestone achieved in MCC illustrates how collaborative efforts can yield substantial results even in uncommon diseases. Data, however, are still immature, and further follow‐up is needed to define more adequately the long‐term benefits of these novel therapeutic strategies. Further efforts to identify biomarkers may be of help to select those patients more likely to benefit from avelumab and facilitate further research with checkpoint inhibitors and other promising agents. New strategies to combine checkpoint inhibitors with different treatment modalities, such as radiotherapy, chemotherapy, or other immunomodulatory agents, is also a matter of intense research in cancer and are currently also being considered in MCC. In this sense, and based on the remarkable advances made, all patients with MCC must be encouraged to participate in clinical trials, whenever available, to enable continued progress to be made.

Acknowledgments

We acknowledge the assistance of Dr. Beatriz Gil‐Alberdi from HealthCo (Madrid, Spain) in the preparation of the first draft of this manuscript. Merck KGaA and Pfizer financially supported medical writer assistance and should also be acknowledged. This article is a review article of published literature and does not contain any original study with human participants or animals performed by any of the authors.

Author Contributions

Conception/design: Rocio Garcia‐Carbonero, Alfonso Berrocal

Collection and/or assembly of data: Rocio Garcia‐Carbonero, Alfonso Berrocal

Data analysis and interpretation: Rocio Garcia‐Carbonero, Ivan Marquez‐Rodas, Luis de la Cruz‐Merino, Javier Martinez‐Trufero, Miguel Angel Cabrera, Jose Maria Piulats, Jaume Capdevila, Enrique Grande, Salvador Martin‐Algarra, Alfonso Berrocal

Manuscript writing: Rocio Garcia‐Carbonero, Ivan Marquez‐Rodas, Luis de la Cruz‐Merino, Javier Martinez‐Trufero, Miguel Angel Cabrera, Jose Maria Piulats, Jaume Capdevila, Enrique Grande, Salvador Martin‐Algarra, Alfonso Berrocal

Final approval of manuscript: Rocio Garcia‐Carbonero, Ivan Marquez‐Rodas, Luis de la Cruz‐Merino, Javier Martinez‐Trufero, Miguel Angel Cabrera, Jose Maria Piulats, Jaume Capdevila, Enrique Grande, Salvador Martin‐Algarra, Alfonso Berrocal

Disclosures

Rocio Garcia‐Carbonero: Merck KGaA, Pfizer (RF, H); Ivan Marquez‐Rodas: Bristol‐Myers Squibb, Merck Sharp & Dohme, Merck‐Serono, Amgen, Novartis, GlaxoSmithKline, Roche, Sanofi, Bioncotech, Incyte (C/A); Luis de la Cruz‐Merino: Merck, Pfizer, Roche, Bristol‐Myers Squibb, Pierre Fabre, Celgene (C/A), Merck, Roche, Celgene (RF), Novartis, AstraZeneca (SAB); Javier Martinez‐Trufero: Bristol‐Myers Squibb, Merck KGaA, Merck Sharp & Dohme, Novartis, Roche, Pierre Fabre, GlaxoSmithKline, Regeneron, Sanofi, Amgen, Incyte, AstraZeneca, Bioncotech (C/A); Miguel Angel Cabrera: Ntra. Sra. de Candelaria University Hospital, Hospiten Rambla (E), Merck Sharp & Dohme, Bristol‐Myers Squibb, Novartis, Pfizer, Roche, Boehringer‐Ingelheim, AstraZeneca (H, C/A, SAB); Jose Maria Piulats: Bristol‐Myers Squibb, Merck Sharp & Dohme, Roche, Novartis, VCN Biosciences, Astellas, Janssen, Bayer, Clovis, AstraZeneca, Merck Serono, Pfizer (SAB), Bristol‐Myers Squibb, Merck Sharp & Dohme, Merck Serono, Pfizer, Janssen (RF); Jaume Capdevila: Bayer, Eisai, Sanofi, Ipsen, Exelixis, Novartis, Pfizer, Adacap, Amgen, Merck Serono (C/A), Bayer, Eisai, Ipsen, Adacap, Pfizer, AstraZeneca, Novartis (RF); Enrique Grande: Pfizer, Bristol‐Myers Squibb, Ipsen, Roche, Eisai, Eusa Pharma, Merck Sharp & Dohme, Sanofi‐Genzyme, Adacap, Novartis, Pierre Fabre, Lexicon, Celgene (H, C/A), Pfizer, AstraZeneca, MTEM/Threshold, Roche, Ipsen, Lexicon (RF); Salvador Martin‐Algarra: Merck, Merck Sharp & Dohme, Bristol‐Myers Squibb, Pierre Fabre, Incyte, Amgen, Roche (SAB), Merck, Merck Sharp & Dohme, Bristol‐Myers Squibb, Roche (travel expenses); Bristol‐Myers Squibb, PharmaMar, Merck Sharp & Dohme, Roche (H), Novartis (ET); Alfonso Berrocal: Merck, Merck Sharp & Dohme, Bristol‐Myers Squibb, Pfizer, Novartis (C/A).

(C/A) Consulting/advisory relationship; (RF) Research funding; (E) Employment; (ET) Expert testimony; (H) Honoraria received; (OI) Ownership interests; (IP) Intellectual property rights/inventor/patent holder; (SAB) Scientific advisory board

References

- 1.Toker C. Trabecular carcinoma of the skin. Arch Dermatol 1972;105:107–110. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Allen PJ, Bowne WB, Jaques DP et al. Merkel cell carcinoma: Prognosis and treatment of patients from a single institution. J Clin Oncol 2005;23:2300–2309. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Iyer JG, Blom A, Doumani R et al. Response rates and durability of chemotherapy among 62 patients with metastatic Merkel cell carcinoma. Cancer Med 2016;5:2294–2301. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Fitzgerald TL, Dennis S, Kachare SD et al. Dramatic increase in the incidence and mortality from Merkel cell carcinoma in the United States. Am Surg 2015;81:802–806. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Lebbe C, Becker JC, Grob JJ et al. Diagnosis and treatment of Merkel cell carcinoma. European consensus‐based interdisciplinary guideline. Eur J Cancer 2015;51:2396–2403. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Youlden DR, Soyer HP, Youl PH et al. Incidence and survival for Merkel cell carcinoma in Queensland, Australia, 1993‐2010. JAMA Dermatol 2014;150:864–872. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Paulson KG, Park SY, Vandeven NA et al. Merkel cell carcinoma: Current US incidence and projected increases based on changing demographics. J Am Acad Dermatol 2018;78:457–463 e452. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Amaral T, Leiter U, Garbe C. Merkel cell carcinoma: Epidemiology, pathogenesis, diagnosis and therapy. Rev Endocr Metab Disord 2017;18:517–532. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Schadendorf D, Lebbe C, Zur Hausen A et al. Merkel cell carcinoma: Epidemiology, prognosis, therapy and unmet medical needs. Eur J Cancer 2017;71:53–69. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Becker JC, Zur Hausen A. Cells of origin in skin cancer. J Invest Dermatol 2014;134:2491–2493. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Goh G, Walradt T, Markarov V et al. Mutational landscape of MCPyV‐positive and MCPyV‐negative Merkel cell carcinomas with implications for immunotherapy. Oncotarget 2016;7:3403–3415. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Feng H, Shuda M, Chang Y et al. Clonal integration of a polyomavirus in human Merkel cell carcinoma. Science 2008;319:1096–1100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Becker JC, Houben R, Ugurel S et al. MC polyomavirus is frequently present in Merkel cell carcinoma of European patients. J Invest Dermatol 2009;129:248–250. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Touze A, Le Bidre E, Laude H et al. High levels of antibodies against merkel cell polyomavirus identify a subset of patients with merkel cell carcinoma with better clinical outcome. J Clin Oncol 2011;29:1612–1619. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Harms PW, Patel RM, Verhaegen ME et al. Distinct gene expression profiles of viral‐ and nonviral‐associated merkel cell carcinoma revealed by transcriptome analysis. J Invest Dermatol 2013;133:936–945. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Koljonen V, Kukko H, Pukkala E et al. Chronic lymphocytic leukaemia patients have a high risk of Merkel‐cell polyomavirus DNA‐positive Merkel‐cell carcinoma. Br J Cancer 2009;101:1444–1447. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Paulson KG, Iyer JG, Blom A et al. Systemic immune suppression predicts diminished Merkel cell carcinoma‐specific survival independent of stage. J Invest Dermatol 2013;133:642–646. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Heath M, Jaimes N, Lemos B et al. Clinical characteristics of Merkel cell carcinoma at diagnosis in 195 patients: The AEIOU features. J Am Acad Dermatol 2008;58:375–381. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Jaeger T, Ring J, Andres C. Histological, immunohistological, and clinical features of merkel cell carcinoma in correlation to merkel cell polyomavirus status. J Skin Cancer 2012;2012:983421. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Moshiri AS, Doumani R, Yelistratova L et al. Polyomavirus‐negative Merkel cell carcinoma: A more aggressive subtype based on analysis of 282 cases using multimodal tumor virus detection. J Invest Dermatol 2017;137:819–827. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Andea AA, Coit DG, Amin B et al. Merkel cell carcinoma: Histologic features and prognosis. Cancer 2008;113:2549–2558. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Harms KL, Healy MA, Nghiem P et al. Analysis of prognostic factors from 9387 Merkel cell carcinoma cases forms the basis for the new 8th edition AJCC staging system. Ann Surg Oncol 2016;23:3564–3571. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Tai P. A practical update of surgical management of merkel cell carcinoma of the skin. ISRN Surg 2013;2013:850797. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.NCCN. NCCN Clinical Practice Guidelines in Oncology (NCCN Guidelines): Merkel Cell Carcinoma. 2017. Available at https://www.nccn.org.

- 25.Bichakjian CK, Olencki T, Aasi SZ et al. Merkel cell carcinoma, version 1.2018, NCCN Clinical Practice Guidelines in Oncology. J Natl Compr Canc Netw 2018;16:742–774. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.O'Connor WJ, Roenigk RK, Brodland DG. Merkel cell carcinoma. Comparison of Mohs micrographic surgery and wide excision in eighty‐six patients. Dermatol Surg 1997;23:929–933. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Boyer JD, Zitelli JA, Brodland DG et al. Local control of primary Merkel cell carcinoma: Review of 45 cases treated with Mohs micrographic surgery with and without adjuvant radiation. J Am Acad Dermatol 2002;47:885–892. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Harrington C, Kwan W. Radiotherapy and conservative surgery in the locoregional management of Merkel cell carcinoma: The British Columbia Cancer Agency experience. Ann Surg Oncol 2016;23:573–578. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Jabbour J, Cumming R, Scolyer RA et al. Merkel cell carcinoma: Assessing the effect of wide local excision, lymph node dissection, and radiotherapy on recurrence and survival in early‐stage disease‐‐Results from a review of 82 consecutive cases diagnosed between 1992 and 2004. Ann Surg Oncol 2007;14:1943–1952. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Bhatia S, Storer BE, Iyer JG et al. Adjuvant radiation therapy and chemotherapy in Merkel cell carcinoma: Survival analyses of 6908 cases from the National Cancer Data Base. J Natl Cancer Inst 2016;108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Goessling W, McKee PH, Mayer RJ. Merkel cell carcinoma. J Clin Oncol 2002;20:588–598. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Lewis KG, Weinstock MA, Weaver AL et al. Adjuvant local irradiation for Merkel cell carcinoma. Arch Dermatol 2006;142:693–700. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Harrington C, Kwan W. Outcomes of Merkel cell carcinoma treated with radiotherapy without radical surgical excision. Ann Surg Oncol 2014;21:3401–3405. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Gunaratne DA, Howle JR, Veness MJ. Sentinel lymph node biopsy in Merkel cell carcinoma: A 15‐year institutional experience and statistical analysis of 721 reported cases. Br J Dermatol 2016;174:273–281. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Fields RC, Busam KJ, Chou JF et al. Recurrence after complete resection and selective use of adjuvant therapy for stage I through III Merkel cell carcinoma. Cancer 2012;118:3311–3320. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Poulsen MG, Rischin D, Porter I et al. Does chemotherapy improve survival in high‐risk stage I and II Merkel cell carcinoma of the skin? Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys 2006;64:114–119. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.D'Angelo SP, Russell J, Lebbe C et al. Efficacy and safety of first‐line avelumab treatment in patients with stage IV metastatic Merkel cell carcinoma: A preplanned interim analysis of a clinical trial. JAMA Oncol 2018;4:e180077. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Kaufman HL, Russell J, Hamid O et al. Avelumab in patients with chemotherapy‐refractory metastatic Merkel cell carcinoma: A multicentre, single‐group, open‐label, phase 2 trial. Lancet Oncol 2016;17:1374–1385. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Rabinowits G. Is this the end of cytotoxic chemotherapy in Merkel cell carcinoma? Onco Targets Ther 2017;10:4803–4807. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Poulsen M, Rischin D, Walpole E et al. High‐risk Merkel cell carcinoma of the skin treated with synchronous carboplatin/etoposide and radiation: A Trans‐Tasman Radiation Oncology Group Study‐‐TROG 96:07. J Clin Oncol 2003;21:4371–4376. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Poulsen M, Walpole E, Harvey J et al. Weekly carboplatin reduces toxicity during synchronous chemoradiotherapy for Merkel cell carcinoma of skin. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys 2008;72:1070–1074. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Tai PT, Yu E, Winquist E et al. Chemotherapy in neuroendocrine/Merkel cell carcinoma of the skin: Case series and review of 204 cases. J Clin Oncol 2000;18:2493–2499. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Becker JC, Lorenz E, Ugurel S et al. Evaluation of real‐world treatment outcomes in patients with distant metastatic Merkel cell carcinoma following second‐line chemotherapy in Europe. Oncotarget 2017;8:79731–79741. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Cowey CL, Mahnke L, Espirito J et al. Real‐world treatment outcomes in patients with metastatic Merkel cell carcinoma treated with chemotherapy in the USA. Future Oncol 2017;13:1699–1710. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Voog E, Biron P, Martin JP et al. Chemotherapy for patients with locally advanced or metastatic Merkel cell carcinoma. Cancer 1999;85:2589–2595. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Colunga A, Pulliam T, Nghiem P. Merkel cell carcinoma in the age of immunotherapy: Facts and hopes. Clin Cancer Res 2017;24:2035–2043. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Nghiem PT, Bhatia S, Lipson EJ et al. PD‐1 blockade with pembrolizumab in advanced Merkel‐cell carcinoma. N Engl J Med 2016;374:2542–2552. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Nghiem P, Bhatia S, Lipson EJ et al. Durable tumor regression and overall survival in patients with advanced Merkel cell carcinoma receiving pembrolizumab as first‐line therapy. J Clin Oncol 2019;37:693–702. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Boyerinas B, Jochems C, Fantini M et al. Antibody‐dependent cellular cytotoxicity activity of a novel anti‐PD‐L1 antibody avelumab (MSB0010718C) on human tumor cells. Cancer Immunol Res 2015;3:1148–1157. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Kaufman HL, Russell JS, Hamid O et al. Updated efficacy of avelumab in patients with previously treated metastatic Merkel cell carcinoma after ≥1 year of follow‐up: JAVELIN Merkel 200, a phase 2 clinical trial. J Immunother Cancer 2018;6:7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Nghiem P, Bhatia S, Brohl AS et al. Two‐year efficacy and safety update from JAVELIN Merkel 200 part A: A registrational study of avelumab in metastatic Merkel cell carcinoma progressed on chemotherapy. J Clin Oncol 2018;36(suppl 15):9507a. [Google Scholar]

- 52.Kelly K, Infante JR, Taylor MH et al. Safety profile of avelumab in patients with advanced solid tumors: A JAVELIN pooled analysis of phase 1 and 2 data. J Clin Oncol 2017;35(suppl 15):3059a. [Google Scholar]

- 53.Walker J, Kasturi V, Lebbe C et al. Second‐line avelumab treatment of patients (pts) with metastatic Merkel cell carcinoma (mMCC): Experience from a global expanded access program (EAP). J Clin Oncol 2018;36(suppl 15):9537a. [Google Scholar]

- 54.Topalian SL, Bhatia S, Hollebecque A et al. Abstract CT074: Non‐comparative, open‐label, multiple cohort, phase 1/2 study to evaluate nivolumab (NIVO) in patients with virus‐associated tumors (CheckMate 358): Efficacy and safety in Merkel cell carcinoma (MCC). Cancer Res 2017;77:CT074a. [Google Scholar]

- 55.Blackmon JT, Dhawan R, Viator TM et al. Talimogene laherparepvec for regionally advanced Merkel cell carcinoma: A report of 2 cases. JAAD Case Rep 2017;3:185–189. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Lyngaa R, Pedersen NW, Schrama D et al. T‐cell responses to oncogenic merkel cell polyomavirus proteins distinguish patients with merkel cell carcinoma from healthy donors. Clin Cancer Res 2014;20:1768–1778. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Hughes MP, Hardee ME, Cornelius LA et al. Merkel cell carcinoma: Epidemiology, target, and therapy. Curr Dermatol Rep 2014;3:46–53. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Tarabadkar ES, Thomas H, Blom A et al. Clinical benefit from tyrosine kinase inhibitors in metastatic Merkel cell carcinoma: A case series of 5 patients. Am J Case Rep 2018;19:505–511. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Wong SQ, Waldeck K, Vergara IA et al. UV‐associated mutations underlie the etiology of MCV‐negative Merkel cell carcinomas. Cancer Res 2015;75:5228–5234. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]