Abstract

Background

Residency program prestige is an important variable medical students consider when creating their rank list. Doximity Residency Navigator is a ranking system that previous reports have shown significantly influences medical student application decisions. Doximity's use of peer nomination as a central component of its methodology for determining program rank has drawn criticism for its lack of objectivity. Doximity has not published information regarding how peer nomination and more objective measures are statistically weighted in reputation calculation.

Objective

This study assesses whether a strong negative correlation exists between residency program size and Doximity ranking.

Methods

A cross-sectional study of Doximity residency rankings from the 2018–2019 academic year was conducted. Data extracted from Doximity included program rank, size, and age. Data were additionally collected from the Blue Ridge Institute for Medical Research, National Institutes of Health, funding in 2018 and the US News & World Report Best Medical Schools 2019–2020. A multivariable linear regression model was used that included Doximity ranking as the outcome variable and residency program size as the predictor variable with adjustment for the aforementioned variables.

Results

Sixteen of the 28 specialties on Doximity were included in the analysis, representing 3388 unique residency programs. After adjustment for covariates, residency program size was a significant predictor of Doximity ranking (β = -1.84; 95% CI -2.01 to -1.66, P < .001).

Conclusions

These findings support the critique that the Doximity reputation ranking system may favor larger residency programs. More transparency for Doximity reputation ranking algorithm is warranted.

What was known and gap

Medical students are using Doximity Residency Navigator, a ranking system for residency programs, to help them create their rank lists when applying to programs, yet there are concerns about the system's lack of objectivity and transparency.

What is new

A cross-sectional study of Doximity residency rankings from the 2018–2019 academic year. A multivariable linear regression model was used that included Doximity ranking as the outcome variable and residency program size as the predictor variable.

Limitations

Program characteristics included in the statistical models do not entirely account for Doximity rankings. Research funding may not be a useful marker for the educational quality of residency programs.

Bottom line

The size of a residency program is a significant predictor of Doximity rank when adjusted for program age, funding from the NIH, and association with a USNWR-ranked medical school.

Introduction

A total of 37 103 applicants participated in the Main Residency Match program in 2018.1 Perceived prestige of a residency program has consistently been shown to be one of the most important factors for applicants deciding on their rank order list.2–5 The Residency Navigator offered through Doximity's website6 is a widely used ranking system for residency programs of many different specialties. A 2018 survey with responses from 2152 applicants across 24 graduate medical education programs found that their reputation rankings were considered “valuable” or “very valuable” to 78% of respondents.7 Of those who responded, 79% reported that their application, interview invitation acceptance, or match rank order list decisions were influenced by Doximity reputation rankings.7 A survey of medical students applying for emergency medicine residency demonstrated that nearly a quarter of applicants make changes to their rank list based on Doximity rankings.8

Subjective reviews of residency programs are a driving factor of Doximity rank methodology,9 specifying that in addition to objective data (eg, alumni research output, board examination pass rate, and other measures), subjective information such as “current resident and recent alumni satisfaction data” and “reputation data” constitutes 2 of 3 major parts of Doximity ranking methodology. Doximity collects reputation data through annual surveys of current and graduated residents, who are asked to nominate up to 5 residency programs. Residency program directors have raised concerns about the appropriateness of creating rankings based on reputational data.10 More than half of survey respondents applying for emergency medicine residency had doubts about the accuracy of Doximity rankings.7

At the time this study was conducted, Doximity did not publicly indicate the extent to which subjective data was statistically weighted in the calculation of residency program reputation. If the rankings are weighted to favor residency programs that receive higher numbers of votes, there would be a bias in favor of larger programs.

This study evaluates the predictive value of residency program size on Doximity ranking. We hypothesized that a strong negative correlation exists between residency program size and ranking.

Methods

A cross-sectional study of Doximity residency program rankings from academic year 2018–2019 was conducted from March 1 to April 2, 2019. Doximity rankings include 28 medical and surgical specialties. Each specialty includes all Accreditation Council for Graduate Medical Education accredited residency training programs throughout the United States. Residency programs within each specialty can be sorted by reputation, research output, size of program, alphabetically, and percent of graduates who are board certified or received further subspecialization. All specialties listed in Doximity were considered for analysis. Since we were interested in controlling for other potential factors that might influence the reputation of a program, we also collected information on founding year of the program, National Institutes of Health (NIH) funding, and US News & World Report (USNWR) medical school rankings. Specialties were excluded if there was no option for sorting programs within the specialty by reputation, or if more than 20% of the programs within a specialty did not have founding years listed on either Doximity or the Fellowship and Residency Electronic Interactive Database. Specialties were also excluded if no NIH funding data were available for any of its residency programs. Additionally, child neurology and medicine–pediatrics were excluded from analysis due to inaccuracies of reported founding year data on the aforementioned resources. A complete list of reasons for exclusions made in this analysis is available as online supplemental material. Data extracted from Doximity included program rank, current size of the program, and year the program was founded. For each program included in the study, data were collected on total NIH funding awarded in 2018 as reported by the Blue Ridge Institute for Medical Research Ranking Tables of NIH Funding to US Medical Schools in 2018, and the USNWR Best Medical Schools research rankings for 2019–2020.

Descriptive statistics were used to describe residency training program characteristics, including rank, age, size, NIH funding, and USNWR medical school research ranking. A multivariable linear regression model was used that included Doximity ranking as the outcome variable and program size as the predictor variable with adjustment for department age, NIH funding, association with USNWR-ranked medical school (binary variable; 1, associated with ranked medical school, and 0, not associated with ranked medical school), and an interaction term between program size and specialty. If the P value for the interaction term was less than .10 in the regression model, we claimed that the relationship between Doximity ranking and size would be different for each specialty. Given a significant interaction term, we used multiple linear regressions and reported results separately for each specialty. An alpha of less than 0.05 was considered statistically significant. All statistical analyses were conducted using jamovi version 0.9.5.12.

The study was deemed exempt from review by the Institutional Review Board at Case Western Reserve University.

Results

Sixteen of the 28 specialties listed on Doximity were included in the analysis. In total, 3388 unique residency programs were represented across these 16 specialties. Across all specialties included in the analysis, the average size of a residency program was 31 residents (interquartile range [IQR] = 20), and the average age of residency programs was 39 years (IQR = 45). A total of $8.3 billion was awarded by the NIH in 2018 to the residency programs included in the analysis. Characteristics of included specialties are shown in the Table.

Table.

Residency Program Characteristics on Doximity (2018–2019)

| Specialty | Programs (n) | Residents per Program (Median, IQR) | Residency Program Age (Median, IQR) | Residency Program NIH Funding ($100,000; IQR) |

| Anesthesiology | 149 | 40 (24, 64) | 57 (34, 61) | 0.00 (0, 7.84) |

| Dermatology | 134 | 11 (8.25, 15) | 38 (11, 59.8) | 0.00 (0, 1.29) |

| Emergency medicine | 231 | 36 (27, 45) | 21 (3, 34.5) | 0.00 (0, 0) |

| Family medicine | 611 | 24 (18, 27) | 29 (5, 45) | 0.00 (0, 0) |

| Internal medicine | 525 | 45 (30, 75) | 45 (4, 62) | 0.00 (0, 0) |

| Neurological surgery | 110 | 14 (11, 18) | 59 (41.8, 65) | 0.00 (0, 9.61) |

| Neurology | 131 | 20 (12, 28) | 50 (13.5, 59) | 0.33 (0, 46.3) |

| Obstetrics and gynecology | 253 | 20 (16, 24) | 62 (31, 69) | 0.00 (0, 0) |

| Orthopedic surgery | 167 | 20 (15, 30) | 54 (39, 60) | 0.00 (0, 0) |

| Otolaryngology | 115 | 15 (10, 20) | 55 (35, 62) | 0.00 (0, 6.42) |

| Pathology | 133 | 16 (12, 22) | 65 (56, 66) | 7.90 (0, 53.3) |

| Pediatrics | 210 | 39 (24, 60.8) | 60 (37.3, 78) | 0.00 (0, 31.8) |

| Physical medicine and rehabilitation | 84 | 16 (12, 21.3) | 47 (25, 61) | 0.00 (0, 1.37) |

| Psychiatry | 237 | 28 (20, 38) | 46 (5, 61) | 0.00 (0, 12.5) |

| Radiology (diagnostic) | 160 | 24 (16, 40) | 46 (39, 47) | 0.00 (0, 7.6) |

| Urology | 138 | 10 (8, 12) | 55 (30.3, 61) | 0.00 (0, 0) |

Abbreviation: IQR, interquartile range.

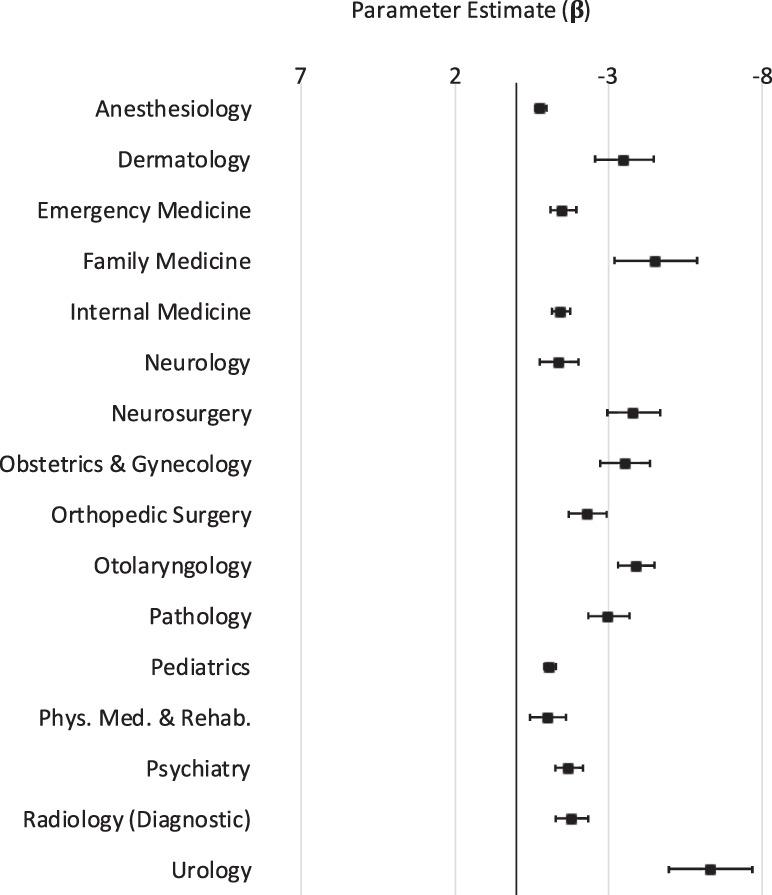

In the overall multivariable regression model, the total number of residents in a program was a significant predictor of Doximity rank (β = -1.8355; 95% confidence interval [CI] -2.0124 to -1.6586; P < .001) after adjusting for departmental NIH funding, association with USNWR-ranked medical school, and residency program age. The interaction term (program size × specialty) was also significant (P < .001). The parameter estimates for the relationship between residency program size and Doximity ranking for each specialty are shown in the Figure. Twelve specialties were excluded due to lack of reputation ranking on Doximity or lack of data regarding departmental NIH funding and/or residency program age. Across the individual multivariable regression models for each specialty, increasing the total residency program size by one resident was associated with improvement in Doximity ranking by 0.80 to 6.32 ranks. R2 values for models and parameter estimates for departmental NIH funding, association with USNWR-ranked medical school, and residency program age are provided as online supplemental material.

Figure.

Parameter Estimates (Beta) for Relationship Between Residency Program Size and Doximity Ranking by Specialty, Adjusted for Program Age, NIH Funding, and Association with USNWR-Ranked Medical School

Abbreviations: Phys. Med. & Rehab, physical medicine and rehabilitation; USNWR, US News & World Report.

Note: The negative value of the beta for the program size relationship indicates that a larger residency program correlates with a lower (ie, improved) rank number. Parameter estimates (beta) are from individual multivariable linear regression models for each specialty. The error bars represent the 95% confidence interval.

Discussion

Of the 16 specialties with available data, the size of a residency program is a significant predictor of 2019 Doximity rank when adjusted for departmental NIH funding, association with USNWR-ranked medical school, and residency program age. Increasing a residency program size by 1 resident was associated with an improvement in Doximity rank of by 0.80 to 6.32 ranks, depending on specialty.

One possible explanation for this phenomenon is that larger programs have more residents (and graduates) who respond to the Doximity reputation survey that is used to determine ranking. Doximity's published methodology9 for its ranking system states that, “To account for ‘self-votes,' raw votes were divided into alumni-votes and non-alumni votes. Alumni votes were weighted according to the percent of the eligible physician population that a particular program accounts for within that specialty (number of alumni divided by total eligible within the specialty).” This documentation does not indicate the degree to which votes from current residents are weighted in comparison to alumni. This documentation also does not indicate whether votes from current residents are adjusted for residency program size. Doximity declined to answer whether the number of survey responses is weighted in the calculation of rank (written communication, February 2019).

The strength of the relationship between residency program size and Doximity rank contrasts with previous work that found only a moderate association between an objective, outcomes-based ranking system and Doximity rankings in one specialty—surgery—which was not one of the specialties included in our study.11 It is possible that Doximity reputation score calculations are weighted such that larger residency programs are often ranked higher because they have more residents and alumni who may respond to the survey. Another possible explanation for the correlation between residency program size and rank is that the strength of a program may have contributed to approval for more residency spots. Finally, large programs may be incorporated into larger academic medical centers, with more opportunities and resources during training, and hence, have higher ranks. What remains unclear for students and the graduate medical education community is precisely how Doximity calculates rankings for residency programs. Previous studies on residency program reputation have employed objective outcomes such as patient outcomes, board pass rates for residents, and prevalence of alumni publications.11,12 Of note, Doximity does incorporate objective factors in its reputation calculation, but it is not clear how much statistical weight these factors are given compared to subjective, peer-nomination surveys.

The findings in this study are limited by the residency program characteristics included in the statistical models, which did not entirely account for Doximity rankings (see R2 values for logistic regression models in the online supplemental material, which range from 0.501–0.814). Another limitation is the use of NIH funding as a surrogate marker for research funding, as this amount may not reflect other sources of research funding. Also, research funding may not be a useful marker for the educational quality of residency programs. We also could not assess the number of people who responded to the Doximity survey, so we had to use program size as a surrogate indicator. Finally, the variability in the nature of academic affiliations between residency programs and hospitals and medical schools makes it difficult to assess the predictive value of an affiliation with a USNWR-ranked medical school.

Conclusions

The size of a residency program is a significant predictor of Doximity rank when adjusted for program age, funding from the NIH, and association with a USNWR-ranked medical school. Our statistical model shows that an increase in residency program size by 1 resident was associated with an improvement in Doximity rank across specialties assessed.

Supplementary Material

References

- 1.National Resident Matching Program. Charting Outcomes in the Match: U.S. Allopathic Seniors. 2019 https://www.nrmp.org/wp-content/uploads/2018/06/Charting-Outcomes-in-the-Match-2018-Seniors.pdf Accessed August 26.

- 2.Davydow D, Bienvenu OJ, Lipsey J, Swartz K. Factors influencing the choice of a psychiatric residency program: a survey of applicants to the Johns Hopkins residency program in psychiatry. Acad Psychiatry. 2008;32(2):143–146. doi: 10.1176/appi.ap.32.2.143. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Parker AM, Petroze RT, Schirmer BD, Calland JF. Surgical residency market research-what are applicants looking for. J Surg Educ. 2013;70(2):232–236. doi: 10.1016/j.jsurg.2012.09.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Svider PF, Gupta A, Johnson AP, Zuliani G, Shkoukani MA, Eloy JA, et al. Evaluation of otolaryngology residency program websites. JAMA Otolaryngol Neck Surg. 2014;140(10):956–960. doi: 10.1001/jamaoto.2014.1714. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Atashroo D, Luan A, Vyas K, Zielins ER, Maan Z, Duscher D, et al. What makes a plastic surgery residency program attractive? An applicant's perspective. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2015;136(1):189–196. doi: 10.1097/PRS.0000000000001365. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Doximity. Residency Navigator 2019–2020. 2019 https://residency.doximity.com Accessed August 26.

- 7.Smith BB, Long TR, Tooley AA, Doherty JA, Billings HA, Dozois EJ. Impact of Doximity residency navigator on graduate medical education recruitment. Mayo Clin Proc Innov Qual Outcomes. 2018;2(2):113–118. doi: 10.1016/j.mayocpiqo.2018.01.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Peterson WJ, Hopson LR, Khandelwal S, White M, Gallahue FE, Burkhardt J, et al. Impact of Doximity residency rankings on emergency medicine applicant rank lists. West J Emerg Med. 2016;17(3):350–354. doi: 10.5811/westjem.2016.4.29750. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Doximity. Residency Navigator Methodology. 2019 https://residency.doximity.com Accessed August 26.

- 10.Cook T. After the Match: the Doximity dilemma. Emerg Med News. 2015;37(10):19. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Wilson AB, Torbeck LJ, Dunnington GL. Ranking surgical residency programs: reputation survey or outcomes measures. J Surg Educ. 2015;72(6):e243–e250. doi: 10.1016/j.jsurg.2015.03.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Bansal N, Simmons KD, Epstein AJ, Morris JB, Kelz RR. Using patient outcomes to evaluate general surgery residency program performance. JAMA surgery. 2016;151(2):111–119. doi: 10.1001/jamasurg.2015.3637. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.