Abstract

Background

Online resources for emergency medicine (EM) trainees and physicians have variable quality and inconsistent coverage of core topics. In this first entry of the Society for Academic Emergency Medicine Systematic Online Academic Resource (SOAR) series, we describe the application of a systematic methodology to comprehensively identify, collate, and curate online content for topic‐specific modules.

Methods

A list of module topics and related terms was generated from the American Board of Emergency Medicine's Model of the Clinical Practice of Emergency Medicine. The authors selected “renal and genitourinary” for the first module, which contained 35 terms; all MeSH headers and colloquial synonyms related to the topic and related terms were searched both within the 100 most impactful online educational websites per the Social Media Index and the FOAMsearch.net search engine. Duplicate entries, journal articles, images, and archives were excluded. The quality of each article was rated using the revised METRIQ (rMETRIQ) score.

Results

The search yielded 13,058 online resources. After 12,717 items were excluded, 341 underwent quality assessment. All renal/genitourinary topics were covered by at least one resource. The median rMETRIQ score was 11 of 21 (interquartile range = 8–14). Calculus of urinary tract was most prominently featured with 60 posts. Thirty‐four posts (10% of full‐text screened FOAM articles) covering 12 core topics were identified as high quality (rMETRIQ ≥ 16).

Conclusions

We demonstrated the feasibility of systematically identifying and curating FOAM resources for a specific EM topic and identified an overrepresentation of some subtopics. This curated list of resources may guide trainees, teacher recommendations, and resource producers. Further entries in the series will address other topics relevant to EM.

The well‐documented growth and use, both formally (in residency curricula1, 2) and informally,3, 4, 5 of free online medical education resources (FOAM) in emergency medicine (EM) have been remarkable.3, 4, 6, 7 However, resources are scattered across an enormous number of sites, of variable and difficult to evaluate quality,8, 9, 10 and may not be at the appropriate level for all learners.11 Additionally, various topics are covered extensively while others receive no or scant coverage12 with no synthesis describing specific topics coverage, extent, level of intended learner, and quality. As individuals, educators, and program leaders look to incorporate FOAM into both extra‐ and co‐curricular activities, we see an opportunity for a centralized resource for systematically identified and quality‐assessed content. This paper aims to create a new type of synthesis scholarship that borrows from the systematic review format to aggregate and filter high‐quality, online academic resources for the purposes of assisting educators in finding useful content within certain topics. Please see Box 1 for details about this initiative.

Box 1. The Objective of the SAEM SOAR Topic Review Series.

This is the first entry in the SAEM Systematic Online Academic Resource (SOAR) Topic Review series. We aim to systematically identify online resources by topic to determine FOAM's current coverage of EM topics and subtopics, assess the quality of these resources with a validated tool, and collate links to identified high‐quality online resources in a user‐friendly framework. Thus, the SAEM SOAR Topic Reviews will enable all users (individual learners, educators, and program leaders) to easily find relevant, high‐quality online resources. Additionally, this ongoing series will help create a durable scientific evaluation of FOAM in EM.

This initial entry in the SAEM SOAR Topic Review series will identify and evaluate online education resources in the Renal and Genitourinary systems. Future editions will review other topics, and this SAEM SOAR Topic Review is featured as an article‐type in Academic Emergency Medicine: Education & Training, open to any and all authors. Additionally, this article and its methodology can serve as a guide to future authors for future topics (and, eventually, updated reviews of prior topics) to provide a comprehensive description of the FOAM landscape.

If you are interested in submitting a future SAEM SOAR Topic Review, please contact SAEM at sroseen@saem.org

Methods

Study Design

The design of this review of educational content was conducted similar to that of a traditional systematic literature review. We attempted to adhere to the PRISMA guidelines as closely as possible.13

Topic Identification

Appropriate subtopic searches was based on the 2016 American Board of Emergency Medicine's Model of the Clinical Practice of Emergency Medicine (MCPEM) document as it “represents essential information and skills necessary for the clinical practice of EM by board‐certified emergency physicians.”13 An important component of the document includes a listing of common conditions, symptoms, and disease presentations often seen in the emergency department under each system heading.14

The “renal and genitourinary” system search used the MCPEM renal and genitourinary topic's six headings and over 20 subheadings to create a list of subtopics for the database search. In addition, the authors also reviewed signs, symptoms, and presentations of the MCPEM for other relevant subtopics. Two medical librarians assisted our teams in translating the subtopic list into MeSH headers and colloquial synonyms.

Database Search

We searched using FOAMsearch.net15 and top 100 FOAM websites per the Social Media Index (SMI)16, 17 as the two search repositories. We selected these two methods to identify online educational resources targeted to health professionals; we were concerned that a nonrestricted search of a generic search engine (e.g., Google) would result in an excess of irrelevant and noneducational content aimed at the lay public. As this was the first attempt at this type of review, we restricted our search to the top 100 sites on the SMI because of resource limitations and the availability of data from the originators of the tool. Additionally, the sites beyond 100 in the SMI have too minimal a presence online to adequately correlate with quality. The results of the initial search were extracted with their heading, source type (journal, blog, podcast, archive), and URL.

Inclusion Criteria

All open educational resources on renal and genitourinary topics were included, as determined by matching with a topic listed on the MCPEM list. Of note, items related to female genitoreproductive topics were not included, since they are classified by MCPEM under gynecology. Of note, podcast show notes were specifically included in this review.

Exclusion Criteria

Items were excluded if they were deemed not relevant to the renal genitourinary topic (e.g., a toxicology post that mentions renal injury as a sequela), irrelevant source types (including posts without text to review, such as pure audio or video links without associated written notes or “show notes”), articles in peer‐reviewed journals, or reblogging repositories of posts published initially elsewhere.

Data Extraction and Quality and Usage Assessment

Google Forms (Mountainview, CA) was used to organize author abstraction tool for the final list of resources and included publication date, word count, accompanying media, described and inferred audience level, subtopic reviewed, author information, and quality assessment via the revised METRIQ (rMETRIQ) score.18 The rMETRIQ score contains seven quality‐related scales, each on a scale of 0 to 3, for a maximal score of 21 (Table 1). Each source was extracted and quality assessed by one study author, who also determined the appropriate audience level (as indicated by the post or as determined by the rater if not indicated) and appropriate usage (e.g., journal club, postshift reading, or appropriate for on‐shift ‘just‐in‐time’ reference). We initially used a small set of papers to calibrate our team for judging the audience and the best usage for individual posts. Disagreements were resolved via consensus. We used a modified Angoff method to determine a threshold for high quality.

Table 1.

rMETRIQ Score Questions

| Questions | Options |

|---|---|

| Q1: Does the resource provide enough background information to situate the user? | 3—Yes, the resource provides sufficient background information to situate the user and also directs users to other valuable resources related to the topic. |

| 2—Yes, the resource provides sufficient background information to situate the user. | |

| 1—No, the information presented within the resource cannot be situated within its broader context, but users are directed to resources with this information. | |

| 0—No, the information presented within the resource cannot be situated within its broader context without looking up information independently. | |

| Q2: Does the resource contain an appropriate amount of information for its length? | 3—No unnecessary, redundant or missing content, all content was essential. |

| 2—Some unnecessary, redundant, or missing content, but most content was essential. | |

| 1—Lots of unnecessary redundant or missing content. | |

| 0—Insufficient content. | |

| Q3: Is the resource well written and formatted? | 3—The resource is very well written and formatted in a way that optimized and benefits learning. |

| 2—The resource is reasonably well written and formatted, but aspects of the organization or presentation are distracting or otherwise detrimental to learning. | |

| 1—The resource is somewhat well written and formatted, but could benefit from substantive editing (e.g., grammatical errors are seen or better organized). | |

| 0—The resource is poorly written and/or formatted and should not be a resource for learning. | |

| Q4: Does the resource cite its references? | 3—Yes, the references are cited, clearly map to specific statements within the resource, and all statements of fact that are not common knowledge are supported with a reference. |

| 2—Yes, the references are cited and clearly map to specific statements within the resource, but statements of fact that are not common knowledge are made without the support of a reference. | |

| 1—Yes, there are references listed but they do not map to specific statements within the resource. | |

| 0—No, no references are cited. | |

| Q5: Is it clear who created the resource and do they have any conflicts of interest? | 3—Yes, the identity and qualifications of the author are clear and they specify that they have no relevant conflicts of interest. |

| 2—Yes, the identity and qualifications of the author are clear, but they do not disclose whether they have any conflicts of interest. | |

| 1—Yes, the identity of the author is clear, but they do not list their qualifications or disclose whether they have any conflicts of interest. | |

| 0—No, the author of the resource has significant conflicts of interest or is not clearly identified (e.g., no name or a pseudonym is used). | |

| Q6: Are the editorial and prepublication peer review processes that were used to create the resource clearly outlined? | 3—Yes, a clear review process is described on the website and it was clearly applied to the resource. |

| 2—Yes, a clear review process is described on the website, but it was not clear whether it was applied to the resource. | |

| 1—Yes, a review process is mentioned on the website, but it was not clearly described. | |

| 0—No, it is unclear whether or not the website has a review process or there is no process. | |

| Q7: Is there evidence of postpublication commentary on the resource's content by its users? | 3—Yes, a robust discussion of the resource's content has occurred that expands upon the content of the resource. |

| 2—Yes, some comments have been made on the resource, but a robust discussion about the resource's content has not occurred. | |

| 1—There was a mechanism to leave comments but none had been made. | |

| 0—No, there was no mechanism to leave comments or comments that were present were either unrelated to the post or unprofessional. |

Results

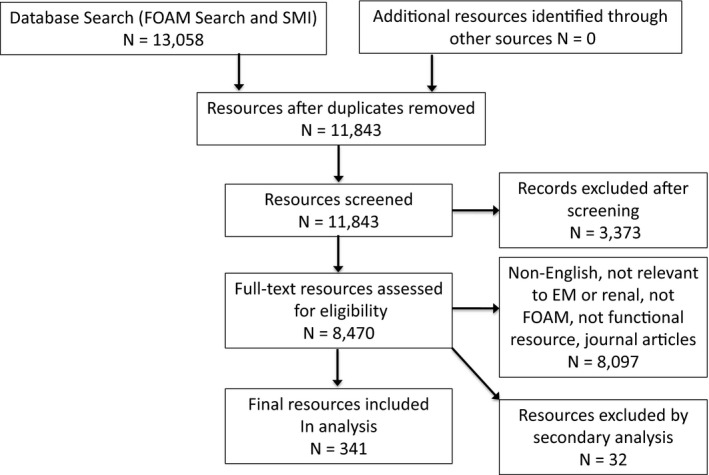

The FOAMsearch and SMI search yielded 13,058 results. Figure 1 displays the search and review results. After excluding for duplicate entries (1,215), nonrelevant titles (3,373), non‐English sources, journals, and non‐FOAM (i.e., not free) sites, nonfunctioning links, tweets, or republished resources (8,097), 330 resources met the inclusion criteria, with the remaining 43 flagged for secondary review. Of these 43 resources, 11 met inclusion criteria on secondary review for a total of 341 resources assessed for quality. The high‐quality threshold was determined by author consensus via modified Angoff method19 at 16 yielding 34 posts with a score ≥ 16. The high‐quality posts can be found at the SAEM SOAR website at https://www.saem.org/education/saem-online-academic-resources.

Figure 1.

Search and review results. FOAM = free online medical education resources; SMI = Social Media Index.

Topic Coverage

Of the 35 renal/genitourinary topics, all were covered at least once; high‐quality posts covered 12 of the topics (plus one additional post on Foley catheter problems and one additional “top nephrology topics,” which covered a range of topics). There is an uneven distribution of FOAM posts within the renal topic, with 17.6% of posts focused on renal calculi. Among the 34 high‐quality posts, 41% are on renal calculi followed by urinary retention (8.8%) and cystitis (8.8%). Although certain topics are covered extensively online, only a small number of these resources met the high‐quality threshold. Renal calculi was most extensively covered online (60 of 341, 18%) but only 23.3% of these posts met the high‐quality threshold. Resources that were relevant but not on the topic list made up 13% of the posts but only 4.4% of these posts were high quality. A total of 7.6% of the posts were on acute and chronic renal failure but only 3.85% were high quality (Table 2).

Table 2.

Renal and Genitourinary SOAR Review Subtopic Analysis

| All | For High‐quality Posts | |

|---|---|---|

| Calculus of urinary tract | 60 | 14 |

| Relevant to topic, but not on list | 45 | 2 |

| Acute and chronic renal failure | 26 | 1 |

| Cystitis | 21 | 3 |

| Torsion | 21 | 1 |

| Hematuria | 16 | 1 |

| Renal tumors | 13 | 0 |

| Urinary retention | 13 | 3 |

| Epididymitis/orchitis | 12 | 1 |

| Gangrene of the scrotum (Fournier's gangrene) | 13 | 2 |

| Paraphimosis/phimosis | 12 | 0 |

| Polycystic kidney disease | 8 | 0 |

| Pyelonephritis | 8 | 2 |

| Hemolytic uremic syndrome | 9 | 3 |

| Priapism | 8 | 0 |

| Dysuria | 6 | 1 |

| Prostatitis | 6 | 0 |

| Nephrotic syndrome | 5 | 0 |

| Prostatic hypertrophy (BPH) | 4 | 0 |

| Glomerulonephritis | 4 | 0 |

| Hernias | 4 | 0 |

| Genital lesion | 4 | 1 |

| Complications of renal dialysis | 3 | 0 |

| Balanitis/balanoposthitis | 1 | 0 |

| Obstructive uropathy | 2 | 0 |

| Urinary incontinence | 2 | 0 |

| Urogenital tumors | 2 | 0 |

| Anuria | 1 | 0 |

| Asymptomatic bacteriuria | 1 | 0 |

| Glomerular disorders | 1 | 0 |

| Testicular masses | 1 | 0 |

| Urethritis | 1 | 0 |

| Not relevant to the topic (e.g., a toxicology post that mentions the kidney) | 8 | 0 |

| Total | 341 | 35 |

SOAR = Systematic Online Academic Resource.

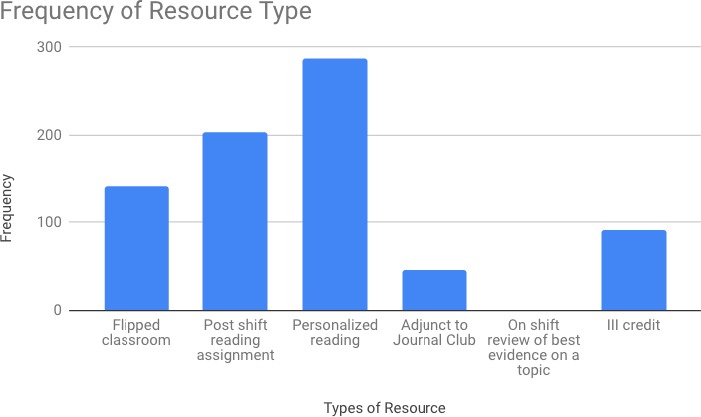

Types of Posts

For each of the 341 articles reviewed, each reviewer determined appropriate uses yielding a total of 771 assigned uses. Topics were determined to be appropriate for personalized reading (87.0%), postshift reading assignment (61.5%), flipped classroom (42.4%), individualized interactive instruction credit (27.9%), adjunct to journal club (13.9%), and on shift review of best evidence on a topic or just‐in‐time resources (0.3%; Figure 2).

Figure 2.

Frequency of resource types found in the renal/genitourinary SOAR review. SOAR = Systematic Online Academic Resource.

Quality Assessment and Trainee Level of Recommendation

Quality Assessment. The rMETRIQ scores ranged from 0 to 20 (mean ± SD = 10.8 ± 3.9). It approximated a normal distribution with a mode of 14. Table 3 lists the rank order of the top posts within our review. Overall, 34 (10%) posts met our high‐quality cutoff score of ≥16. In evaluating rates of subtopic meeting our quality criteria, the topics with the highest numbers and rates of high‐quality posts were renal colic (60 total; 14 [23%] high quality), hemolytic uremic syndrome (seven total; one [14%] high quality), genital lesions (four total; one [25%] high quality), and urinary retention (13 total; three [23%] high quality). Renal colic was by far the most frequently covered subtopic overall and among resources that met our quality criteria.

Table 3.

Rank Order of Posts in the Renal and Genitourinary SOAR Review by rMETRIQ Score

| Subtopic | Name of First Author | Name of Blog Post | URL | Level of Trainee (Starred = Author; Unstarred = Team's Recommendation) | rMETRIQ score |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Calculus of urinary tract (renal colic) | Helman, Anton |

Journal Jam 3 – Ultrasound vs CT for Renal Colic View Larger Image |

https://emergencymedicinecases.com/ultrasound-vs-ct-for-renal-colic/ | Junior, senior, attending | 20 |

| Calculus of urinary tract (renal colic) | Chartier, Lucas | Episode 5: Renal Colic, Toxicology Update & Body Packers | https://emergencymedicinecases.com/episode-5-renal-colic-toxicology-update-body-packers/ | Clerk, intern, junior, senior, attending | 19 |

| Calculus of urinary tract (renal colic) | Swaminathan, Anand | Optimal First Line Analgesia in Ureteric Colic | https://coreem.net/journal-reviews/analgesia-ureteric-colic/ | Intern, junior, senior, attending | 19 |

| Topic not on list (Foley catheter problems) | Schneider, Aaron | Foley Catheter Patients: Common ED Presentations / Management / Pearls & Pitfalls | http://www.emdocs.net/foley-catheter-patients-common-ed-presentations-management-pearls-pitfalls/ | Intern, junior, senior | 19 |

| Calculus of urinary tract (renal colic) | Firestone, Daniel | Top 10 reasons NOT to order a CT scan for suspected renal colic | https://www.aliem.com/2014/04/top-10-reasons-order-ct-scan-suspected-renal-colic/ | Intern, junior, senior, attending | 19 |

| Cystitis | Sahsi, Rupinder | Diagnosing Pediatric Urinary Tract Infections | http://epmonthly.com/article/diagnosing-pediatric-urinary-tract-infections/ | Clerk, intern, junior, senior, attending | 18 |

| Hemolytic uremic syndrome | Swartz, Jordan | Hemolytic uremic syndrome | https://wikem.org/w/index.php?title=Hemolytic_uremic_syndrome&redirect=no | Intern, junior, senior | 18 |

| Urinary retention | Benitez, Javier | First ALiEM journal article: Trial of void for acute urinary retention | https://www.aliem.com/2013/03/trial-of-void-acute-urinary-retention/ | Clerk, intern, junior, senior, attending | 18 |

| Calculus of urinary tract (renal colic) | Shih, Jeffrey | Ultrasound For The Win: 46F with Right Abdominal and Flank Pain #US4TW | https://www.aliem.com/2015/02/ultrasound-win-46f-right-abdominal-flank-pain-us4tw/ | Clerk, intern, junior, senior | 18 |

| Calculus of urinary tract (renal colic) | Swaminathan, Anand | Medical Expulsion Therapy with Tamsulosin in Ureteral Colic | http://www.emdocs.net/medical-expulsion-therapy-with-tamsulosin-in-ureteral-colic/ | Junior, senior, attending | 17 |

| Calculus of urinary tract (renal colic) | Swaminathan, Anand | Medical Expulsion Therapy in Ureteral Colic: An Update | http://rebelem.com/medical-expulsion-therapy-in-ureteral-colic-an-update/ | Junior, senior, attending | 17 |

| Calculus of urinary tract (renal colic) | Swaminathan, Anand | Medical Expulsive Therapy (MET) in Renal Colic | https://coreem.net/journal-reviews/medical-expulsive-therapy-met-in-renal-colic/ | Junior, senior, attending | 17 |

| Calculus of urinary tract (renal colic) | Chitnis, Subhanir | Nephrolithiasis: Diagnosis and Management in the ED | http://www.emdocs.net/nephrolithiasis-diagnosis-management-ed/ | Junior, senior, attending | 17 |

| Pyelonephritis | Nickson, Chris | Urosepsis | https://lifeinthefastlane.com/ccc/urosepsis/ | Clerk, intern, junior | 17 |

| Dysuria | Lin, Michelle | Paucis Verbis card: Urinary tract infection | https://www.aliem.com/2010/02/paucis-verbis-card-urinary-tract-infection/ | Intern, junior, senior | 17 |

| Cystitis | Shenvi, Christina | Uncomplicated Urinary Tract Infection in Older Adults: Diagnosis and Treatment (Part 1) | https://www.aliem.com/2014/03/uncomplicated-urinary-tract-infection-older-adults-diagnosis-treatment-1/ | Preclerk, clerk, intern, junior, senior | 17 |

| Cystitis | Shenvi, Christina | Uncomplicated Urinary Tract Infections in Older Adults: Diagnosis and Treatment (Part 2) | https://www.aliem.com/2014/04/uncomplicated-urinary-tract-infections-older-adults-diagnosis-treatment-part-2/ | Preclerk, clerk, intern, junior, senior, attending | 17 |

| Acute and chronic renal failure | LaPietra, Alexis | Piperacillin/Tazobactam and Risk of Acute Kidney Injury with Vancomycin | https://www.aliem.com/2014/05/piperacillin-tazobactam-acute-kidney-injury/ | Junior, senior | 17 |

| Calculus of urinary tract (renal colic) | Intravenous lidocaine for renal colic | https://www.aliem.com/2018/02/intravenous-lidocaine-for-renal-colic/ | Intern, junior, senior, attending | 17 | |

| Hematuria | Saunders, Fiona | Investigating microscopic haematuria in blunt abdominal trauma | https://bestbets.org/bets/bet.php?id=41 | Junior, senior, attending | 16 |

| Urinary retention | Rezaie, Salim | Urinary Retention: Rapid Drainage or Gradual Drainage to Avoid Complications? | http://rebelem.com/urinary-retention-rapid-drainage-gradual-drainage-avoid-complications/ | Junior, senior, attending | 16 |

| Calculus of urinary tract (renal colic) | Milne, Ken | SGEM#202: Lidocaine for Renal Colic? | http://thesgem.com/2018/01/sgem202-lidocaine-for-renal-colic/ | Intern, junior, senior, attending | 16 |

| Calculus of urinary tract (renal colic) | Wightman, Rachel | Ultrasonography vs CT in Renal Colic | https://coreem.net/journal-reviews/ultrasonography-vs-ct-in-renal-colic/ | Intern, junior, senior, attending | 16 |

| Hemolytic uremic syndrome | Long, Brit | EM@3AM – Hemolytic Uremic Syndrome | http://www.emdocs.net/em3am-hemolytic-uremic-syndrome/ | Junior, senior, attending | 16 |

| Gangrene of the scrotum (Fournier's gangrene) | Cohen, Paul | How do we misdiagnose and mismanage necrotizing fasciitis? | http://www.emdocs.net/misdiagnose-mismanage-necrotizing-fasciitis/ | Junior, senior, attending | 16 |

| Gangrene of the scrotum (Fournier's gangrene) | Santistevan, Amie | Necrotizing Fasciitis: Pearls & Pitfalls | http://www.emdocs.net/necrotizing-fasciitis-pearls-pitfalls/ | Preclerk, clerk, intern, junior, senior, attending | 16 |

| Urinary retention | Fox, Sean | Urinary Retention in Kids | http://pedemmorsels.com/urinary-retention-in-kids/ | Junior | 16 |

| Torsion | Shih, Jeffrey | Ultrasound For The Win: 22M with Scrotal Pain #US4TW | https://www.aliem.com/2015/02/ultrasound-win-22m-scrotal-pain-us4tw/ | Junior, senior, attending | 16 |

| Genital lesions | Lin, Michelle | Paucis Verbis: Genital Ulcers | https://www.aliem.com/2012/05/paucis-verbis-genital-ulcers/ | Clerk, intern, junior, senior | 16 |

| Pyelonephritis | Long, Brit | Pyelonephritis: It's not always so straightforward… | http://www.emdocs.net/pyelonephritis-its-not-always-so-straightforward/ | Preclerk, clerk, intern, junior, senior, attending | 16 |

| Topic not on list | Sparks, Matt | Renal Fellow Network: Top nephrology‐related stories of 2016 | http://renalfellow.blogspot.com/2016/12/top-nephrology-related-stories-of-2016_25.html | Junior, senior, attending | 16 |

| Epididmitis/Orchitis | Shih, Jeffrey | Ultrasound For The Win! Case – 64M with Fever and Scrotal Pain #US4TW | https://www.aliem.com/2018/02/ultrasound-for-the-win-case-fever-scrotal-pain-us4tw/ | Intern, junior, senior, attending | 16 |

| Calculus of urinary tract (renal colic) | Lin, Michelle | Author Insight: Ultrasonography versus CT for suspected nephrolithiasis | NEJM | https://www.aliem.com/2015/03/author-insight-ultrasonography-versus-ct-for-suspected-nephrolithiasis-nejm/ | Junior, senior, attending | 16 |

| Calculus of urinary tract (renal colic) | Swaminathan, Anand | Alpha Blockers in Renal Colic: A Systematic Review | http://rebelem.com/alpha-blockers-in-renal-colic-a-systematic-review/ | Junior, senior, attending | 16 |

SOAR = Systematic Online Academic Resource.

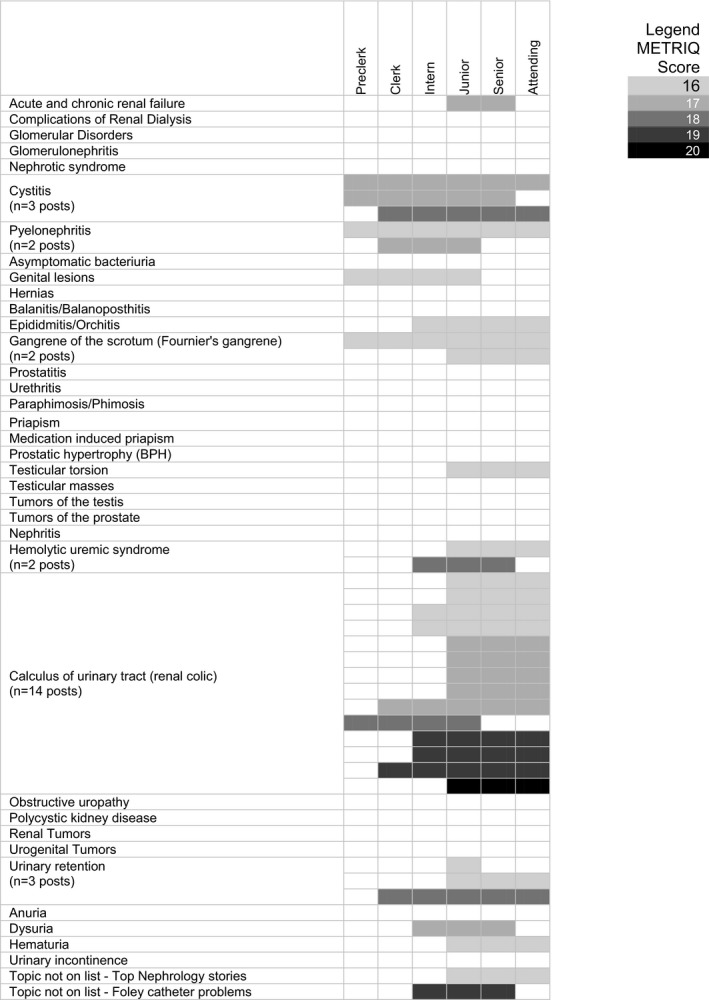

Recommended Target Audience

Of the 341 posts reviewed, each was assigned to be appropriate for at least one type of learner, ranging from preclerk to attending physician. Authors of the posts specified target audience levels for only 12 posts; the remaining were determined by reviewers. Each of these were deemed appropriate for multiple levels (mean = 3.2 levels). In order of frequency, the most common audience was junior resident (76.3%), intern (64.2%), senior resident (56.4%), clerk (i.e., third‐ or fourth‐year medical student, 52.1%), attending (40%), and preclerk (i.e., first‐ or second‐year medical student, 29.0%). The distribution among high‐quality resources was similar: junior resident, 100%; senior resident, 94%; attending, 74%; intern, 56%, clerk, 29%; and preclerk, 12%. Among the high‐quality posts, topics that had the highest number of posts relevant to at least one learner were calculus of urinary tract (renal colic; 41.2%), cystitis (8.8%), and urinary retention (8.8%). Figure 3 graphically depicts the distribution of covered topics, appropriate level, and rMETRIQ score for high‐quality resources.

Figure 3.

FOAM nephrology coverage at a glance. FOAM = free online medical education resources.

Discussion

This study marks the first detailed description of a comprehensive, systematic review of FOAM resources. We performed a topic‐based review and curation of FOAM resources to identify high‐quality resources for educators to integrate into their curricula. Our results demonstrate that it can be quite difficult to navigate and curate resources on a particular topic. The challenges of searching and reviewing online literature are not new.20 Prior studies looking at online patient information resources have demonstrated high variability in quality.21, 22, 23, 24, 25, 26 Since both educators and trainees find it difficult to reliably rate online resources,9, 10 it is likely that trainees and clinicians have difficulty identifying high‐quality resources for their own learning, which frequently occurs at the point of care.5

Other initiatives, such as the Academic Life in Emergency Medicine (ALiEM) Approved Instructional Resources (AIR) series,27, 28 collect and curate topic specific resources, but utilize a much less rigorous and comprehensive search strategy than in this review. Further, the goal of the AIR series is to build modules sufficient for individual interactive instruction, not to comprehensively describe and assess the coverage of FOAM. This review extends the AIR series’ pioneering search technique to the top 100 of the SMI instead of the top 50, as well as performing a broader and more comprehensive FOAMsearch. Additionally, this review applies a newly refined scoring system (the rMETRIQ score). Finally, this review attempts to classify resources based on trainee level to identify appropriate resources for different levels of learner.

Topic Coverage

While we found a plethora of resources within our selected topic, many were not of high quality. In fact, 90% of the identified resources did not reach the high‐quality threshold set by our study group. The reasons for heterogeneity of quality as measured by the rMETRIQ score were quite variable. Some sites (e.g., Wikis) were limited in their ability to attribute the work to a single, well‐documented author, raising the potential for author conflict of interest or insufficient knowledge or education skill. On other sites, it was difficult to discern whether an author had academic credentials and/or training, or conflicts of interest, since they used informal biographies. Although we performed this review primarily to identify resources for EM educators and learners, a high level of contribution exists from other specialties that are avidly contributing to the FOAM space. Radiopaedia,29, 30 notably, contributed over 18% of the search results that we reviewed.

The coverage of the topics that we identified for the search was quite heterogeneous. Every topic was covered by at least one post; some (particularly renal colic) were discussed extensively, while others were only covered once. This is consistent with the findings of the less granular review of all FOAM topics by Stuntz and Clontz,12 which found markedly uneven coverage of topics, with those thought to be more interesting discussed more frequently. While all topic areas were covered by at least one resource, it is notable that resources did not have to provide comprehensive coverage of a topic to be classified under it and many subtopics are incompletely covered. This suggests that many renal and genitourinary topics have yet to be covered in depth anywhere. Numerous resources were also created on topics that did not make our topic list, suggesting that, while superficial, the coverage of this area within FOAM is vast.

Best Use of Resources

Very few resources were deemed by our team to be worthy of on‐shift review, mostly because the resources were either too in depth (high‐quality posts) or incomplete (low‐quality posts), although online content on renal/genitourinary topics may have less on‐shift utility than other topics. The literature describes trainees reporting that they do use the content from FOAM to review during shifts at the point of care.5 Perhaps, in other topic areas (e.g., cardiology or critical care) there may be other FOAM resources that are of high quality and appropriate for such usage; our review largely yielded only a very small fraction of posts (0.3%) that we found would be appropriate for referencing on shift, as they were generally broader reviews of topics as opposed to references for clinical utility (e.g., clinical decision aides or medication dosage recommendations).

Limitations

There were a number of limitations to our present protocol and study. First and foremost, we excluded audio and video entries from our review. Previous literature has shown that trainees have some level of preference for podcasts,3, 4 and so this may have resulted in the exclusion of some popular and leading FOAM content. However, podcast show notes were included in our search strategy and included for review.

Also, for pragmatic reasons (primarily resource constraints), only a single reviewer extracted information and rated the items (rMETRIQ score, appropriate target audience, usage). To mitigate the problems with this single extractor, we met multiple times as a team to discuss the interpretation of each aspect of the rMETRIQ score. However, despite the presumed improvements in reliability of the rMETRIQ score,18 it is likely that additional raters would be needed to reach reliable ratings for each resource.31

Moreover, we did not directly assess the accuracy of content included in posts. Assessing accuracy of online educational resources is difficult and no criterion standard exists. The rMETRIQ score does not directly ask for a quality appraisal of the blog post; it was designed and derived to be used by junior trainees who may be unable to accurately judge quality.32 Further, the rMETRIQ score includes elements that are likely to correlate with and/or help ensure accuracy (e.g., peer review processes, postpublication commentary, references, COI). In the future, applying another scoring tool which incorporates an educator's judgment on accuracy (such as the ALiEM AIR score27, 28) may potentially improve the quality assessment of online content (n.b., prior work has shown correlation between the AliEM AIR and METRIQ scores31). Next, while we did discuss and calibrate our raters with regards to the target audience and usage suitability, we did not compute any inter‐rater reliability metric on this part of our extraction.

Finally, our analysis likely overestimates topic coverage, as posts are included if they cover any part of a topic. Finally, we utilized a new and as‐of‐yet untested methodology to identify both the resources for inclusion and the highest quality resources.

Conclusion

We present a systematic approach to reviewing online educational resources, showing that only 10% of posts that met our inclusion criteria were of high quality according to the revised METRIQ scoring tool. In our first review, we found that free online medical education resources covered renal/genitourinary topics broadly but with variable quality and high‐quality posts only covered approximately one‐third of topics. We hope that educators and learners can use this information to find educational resources and that free online medical education resources content producers can use this information to choose topics to produce new content.

We thank the SAEM for their support of this project.

AEM Education and Training 2019;3:375–386

The authors have no relevant financial information.

AB reports salary support from the Society for Academic Emergency Medicine (SAEM) for her work on this project. TMC hold grants from the Physician Services Incorporated Foundation for work on social media knowledge translation. NST receives salary support from the American Medical Association for his role as Digital Media Editor, JAMA Network Open.

Related articles appear on pages 396 and 398.

References

- 1. Reiter DA, Lakoff DJ, Trueger NS, Shah KH. Individual interactive instruction: an innovative enhancement to resident education. Ann Emerg Med 2013;61:110–3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Scott KR, Hsu CH, Johnson NJ, Mamtani M, Conlon LW, DeRoos FJ. Integration of social media in emergency medicine residency curriculum. Ann Emerg Med 2014;64:396–404. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Purdy E, Thoma B, Bednarczyk J, Migneault D, Sherbino J. The use of free online educational resources by Canadian emergency medicine residents and program directors. CJEM 2015;1717:101–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Mallin M, Schlein S, Doctor S, Stroud S, Dawson M, Fix M. A survey of the current utilization of asynchronous education among emergency medicine residents in the United States. Acad Med J Assoc Am Med Coll 2014;89:598–601. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Patocka C, Lin M, Voros J, Chan T. Point‐of‐care resource use in the emergency department: a developmental model. AEM Educ Train 2018;2:221–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Cadogan M, Nickson C. Free Open Access Medical Education. Life in the Fast Lane. 2014. Available at: http://lifeinthefastlane.com/foam/. Accessed January 9, 2016.

- 7. Cadogan M, Thoma B, Chan TM, Lin M. Free open access meducation (FOAM): the rise of emergency medicine and critical care blogs and podcasts (2002‐2013). Emerg Med J 2014;31:e76–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Schriger DL. Does everything need to be “scientific”? Ann Emerg Med 2016;68:738–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Krishnan K, Thoma B, Trueger NS, Lin M, Chan TM. Gestalt assessment of online educational resources may not be sufficiently reliable and consistent. Perspect Med Educ 2017;6:91–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Thoma B, Sebok‐Syer SS, Krishnan K, et al. Individual gestalt is unreliable for the evaluation of quality in medical education blogs: a METRIQ study. Ann Emerg Med 2017;70:394–401. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Trueger NS. Yelp, but for blogs? Ann Emerg Med 2016;68:736–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Stuntz R, Clontz R. An evaluation of emergency medicine core content covered by free open access medical education resources. Ann Emerg Med 2016;67:649–53.e2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Moher D, Liberati A, Tetzlaff J, Altman DG; PRISMA Group . Preferred reporting items for systematic reviews and meta‐analyses: the PRISMA statement. Ann Intern Med 2009;151:264–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Counselman FL, Babu K, Edens MA, et al. The 2016 Model of the Clinical Practice of Emergency Medicine. J Emerg Med 2017;52:846–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Raine T, Thoma B, Chan TM, Lin M. FOAMSearch.net: a custom search engine for emergency medicine and critical care. Emerg Med Australas 2015;27:363–5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Thoma B, Sanders J, Lin M, Paterson Q, Steeg J, Chan T. The Social Media Index: measuring the impact of emergency medicine and critical care websites. West J Emerg Med 2015;16:242–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Thoma B, Chan TM, Kapur P, et al. The Social Media Index as an indicator of quality for emergency medicine blogs: a METRIQ study. Ann Emerg Med 2018;72:696–702. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Colmers‐Gray IN, Krishnan K, Chan TM, et al. P022: the revised METRIQ score: an international, social‐media based usability analysis of a quality evaluation instrument for medical education blogs. Can J Emerg Med 2018;20(Suppl S1):S64. [Google Scholar]

- 19. George S, Haque MS, Oyebode F. Standard setting: comparison of two methods. BMC Med Educ 2006;6:46. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Lo A, Shappell E, Rosenberg H, et al. Four strategies to find, evaluate, and engage with online resources in emergency medicine. Can J Emerg Med 2018;20:293–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Raikos A, Waidyasekara P. How useful is YouTube in learning heart anatomy? Anat Sci Educ 2014;7:12–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Azer SA. Mechanisms in cardiovascular diseases: how useful are medical textbooks, eMedicine, and YouTube? AJP Adv Physiol Educ 2014;38:124–34. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Rees CE, Ford JE, Sheard CE. Evaluating the reliability of DISCERN: a tool for assessing the quality of written patient information on treatment choices. Patient Educ Couns 2002;47:273–5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Khazaal Y, Chatton A, Cochand S, et al. Brief DISCERN, six questions for the evaluation of evidence‐based content of health‐related websites. Patient Educ Couns 2009;77:33–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Charnock D, Shepperd S, Needham G, Gann R. DISCERN: an instrument for judging the quality of written consumer health information on treatment choices. J Epidemiol Community Health 1999;53:105–11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Shepperd S, Charnock D, Cook A. A 5‐star system for rating the quality of information based on DISCERN. Health Info Libr J 2002;19:201–5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Lin M, Joshi N, Grock A. Approved Instructional Resources (AIR) series: a national initiative to identify quality emergency medicine blog and podcast content for resident education. J Grad Med Educ 2016;8:219–25. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Chan TM, Grock A, Paddock M, Kulasegaram K, Yarris LM, Lin M. Examining reliability and validity of an online score (ALiEM AIR) for rating free open access medical education resources. 2016;68:729–35. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Hoang JK, McCall J, Dixon AF, Fitzgerald RT, Gaillard F. Using social media to share your radiology research: how effective is a blog post? J Am Coll Radiol 2015;12:760–5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Dixon A, Fitzgerald RT, Gaillard F. Letter by Dixon et al regarding article, “A randomized trial of social media from circulation”. Circulation 2015;131:e393. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Thoma B, Sebok‐Syer SS, Colmers‐Gray I, et al. Quality evaluation scores are no more reliable than gestalt in evaluating the quality of emergency medicine blogs: a METRIQ study. Teach Learn Med 2018;30:294–302. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Chan TM, Thoma B, Krishnan K, et al. Derivation of two critical appraisal scores for trainees to evaluate online educational resources: a METRIQ study. West J Emerg Med 2016;17:574–84. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]