Abstract

Thyroid hormone (TH) signaling is a universal regulator of metabolism, growth, and development. Here, we show that TH-TH receptor (TH-TR) axis alterations are critically involved in diabetic nephropathy–associated (DN-associated) podocyte pathology, and we identify TRα1 as a key regulator of the pathogenesis of DN. In ZSF1 diabetic rats, T3 levels progressively decreased during DN, and this was inversely correlated with metabolic and renal disease worsening. These phenomena were associated with the reexpression of the fetal isoform TRα1 in podocytes and parietal cells of both rats and patients with DN and with the increased glomerular expression of the TH-inactivating enzyme deiodinase 3 (DIO3). In diabetic rats, TRα1-positive cells also reexpressed several fetal mesenchymal and damage-related podocyte markers, while glomerular and podocyte hypertrophy was evident. In vitro, exposing human podocytes to diabetes milieu typical components markedly increased TRα1 and DIO3 expression and induced cytoskeleton rearrangements, adult podocyte marker downregulation and fetal kidney marker upregulation, the maladaptive cell cycle induction/arrest, and TRα1-ERK1/2–mediated hypertrophy. Strikingly, T3 treatment reduced TRα1 and DIO3 expression and completely reversed all these alterations. Our data show that diabetic stress induces the TH-TRα1 axis to adopt a fetal ligand/receptor relationship pattern that triggers the recapitulation of the fetal podocyte phenotype and subsequent pathological alterations.

Keywords: Cell Biology

Keywords: Chronic kidney disease, Diabetes, Molecular biology

Elevated thyroid hormone receptor TRα1 promotes thyroid-inactivating enzyme deiodinase 3 expression and diabetic nephropathy–associated podocyte pathology.

Introduction

Thyroid hormone (TH) signaling is a universal regulator of the metabolism, growth, and development. Highly conserved in the animal kingdom, TH signaling played a crucial role in the colonization of land by organisms, the evolution of complex organs, epimorphic regeneration, metamorphosis, endothermy, and hibernation (1–3). The active form of TH, L-triiodothyronine (T3), acts by regulating gene transcription through the binding to its nuclear receptors, TH receptor (TR) α and β (4). TRs have distinct expression patterns and distinct functional roles during fetal and adult life that are contingent on their liganded states. TRα1 regulates larval transition, amphibian metamorphosis and morphogenesis, and tissue maturation in the mammalian embryo (5–7). It is the predominant form in developing organs, such as the heart (8) and brain (9), while TRβ1 is highly expressed during adulthood. During fetal life, T3 levels are low, and unliganded TRα1 (aporeceptor) represses the transcription of target adult genes. After birth, T3 levels increase, and liganded TRα1 (holoreceptor) triggers different gene expression programs, promoting postnatal development and maturation. The low availability of T3 — which is indispensable for the normal development of the fetus — is guaranteed by the TH-inactivating enzyme deiodinase 3 (DIO3). DIO3 is expressed abundantly in fetal tissues to protect the fetus against high maternal T3 levels, thus preventing precocious tissue maturation (10).

In diabetes, the fetal profile of low T3 levels recurs: diabetic patients have significantly lower T3 plasma levels (11) and a high prevalence of thyroid dysfunction compared with the healthy population, while hypothyroidism — both clinical and subclinical — is the most common diabetes-associated disorder (12, 13). Several clinical studies have also shown that, in diabetic patients, thyroid dysfunction and low T3 levels are strongly associated with worse renal clinical outcomes and increased mortality (14–16). Diabetic nephropathy (DN) is one of the most common complications of diabetes mellitus and the leading cause of end-stage renal disease worldwide. Primary hallmarks of DN are podocyte dedifferentiation, hypertrophy, maladaptive proliferation, and apoptosis (17). Podocytes are particularly vulnerable to the noxious stimuli of diabetic milieu (18, 19), and, since they cannot proliferate, podocyte damage and loss result in the impairment of the integrity and function of the glomerular filtering barrier and the subsequent loss of proteins into the urine (17). In response to the various stressful stimuli (including high glucose, free radicals, mechanical stress), podocytes reenter the cell cycle, increase in size, and frequently undergo mitosis with nuclear division but do not complete cytokinesis (20, 21), generating aneuploid podocytes. These rapidly detach and die in a process called mitotic catastrophe (22). Surviving podocytes undergo hypertrophy and dedifferentiation, which is characterized by structural remodeling, the downregulation of terminally differentiated podocyte markers, the concurrent reactivation of developmental pathways, and the acquisition of mesenchymal features (23–28). This adoption of a fetal phenotype results in overall structural and metabolic remodeling of the glomerulus, with detrimental consequences for the kidney’s filtering functions. Although these phenomena have been observed in DN, the etiogenesis remains poorly understood.

Considering (a) the biological roles that TH signaling has in organ development and maturation, (b) the changes in TH availability in diabetes, and (c) the concomitant reactivation of developmental pathways in diabetic podocytes, we hypothesized that the TH-TRα1 axis plays a key role in the pathogenesis of DN by triggering an inappropriate reactivation of podocyte developmental programs and subsequent pathological growth and remodeling. To verify this hypothesis, we studied changes in TH signaling in ZSF1 diabetic rats and diabetic patients, and in vitro models of DN, as well as the possible underlying molecular pathways. Our findings demonstrate that in DN the TH-TR signaling adopts a ligand/receptor relationship profile that resembles that of early embryonic kidney development: high TRα1 in low levels of T3 may act as aporeceptor to trigger early developmental pathways (as it does during normal development) that are responsible for the “fetal-like” pathomorphological changes observed in diabetic podocytes. Moreover, our data indicate that diabetic stress–induced alterations in podocytes are manifestations of an imperfect/maladaptive partial recapitulation of early developmental steps and identify TRα1 as a possible therapeutic target for the treatment of DN.

Results

Diabetes induces the fetal pattern of renal TH signaling that may be involved in the progression of nephropathy.

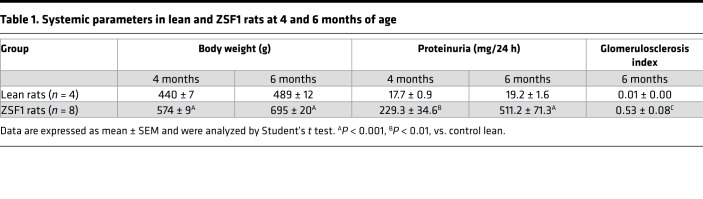

To examine whether TH signaling is associated with the progression of DN, we analyzed changes in circulating T3 levels and the relationships between T3 levels and parameters of metabolic or renal disease in ZSF1 rats (Table 1). At 3 months of age — at the beginning of the study — T3 levels started to decline in ZSF1 rats and dropped to significantly lower levels than in lean controls as the disease progressed (Figure 1A). The Δ between the T3 levels of ZSF1 rats at 4 and 6 months of age, in particular, was inversely correlated with Δ of body weight (R2=0.8754 and P = 0.0061) and with Δ of proteinuria levels (R2 = 0.7822 and P = 0.0193) at the same ages. T3 levels were also inversely correlated with the glomerulosclerosis index (R2 = 0.6154 and P = 0.0212) (Figure 1, B–D), indicating that TH signaling was possibly involved in the progression and related to the severity of DN.

Table 1. Systemic parameters in lean and ZSF1 rats at 4 and 6 months of age.

Figure 1. Changes in T3 levels and correlation of T3 with obesity and renal function parameters in diabetic rats.

(A) Serum T3 levels (ng/dl) declined progressively in ZSF1 rats at 3, 4, and 6 months of age compared with control rats. Data are expressed as mean ± SEM. *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01, unpaired Student’s t test. n = 3–10 rats per group. (B–D) Relationship between T3 levels and parameters of obesity or renal disease in ZFS1 rats at 6 months of age. ΔT3 levels (ng/dl) between 6 and 4 months of age inversely correlated with (B) ΔBW (g) (R2 = 0.8754, P = 0.0061, n = 6 rats) and (C) with Δproteinuria levels (mg/day) (R2 = 0.7822, P = 0.0193, n = 6 rats). (D) T3 levels negatively correlated with GSI in ZSF1 rats (R2 = 0.6154, P = 0.0212, n = 8 rats). R2 values are determined by linear regression. GSI, glomerulosclerosis index.

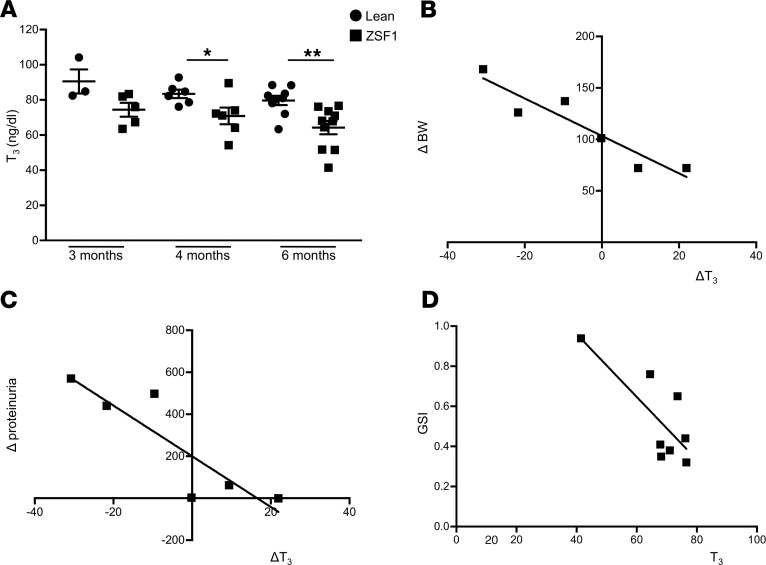

We then investigated whether T3 level decrements were associated with changes in TRs’ expression. Due to a lack of data in kidneys, we first evaluated TR expression patterns in renal tissues of rats at various developmental stages. TRα1 was highly expressed in rat embryonic kidneys, while it declined significantly postnatally (Figure 2A); TRβ1 remained unchanged throughout development (data not shown). Then, we analyzed TRα1 and TRβ1 protein expression in kidney specimens from diabetic ZSF1 rats at 6 months of age, when overt nephropathy had developed. Western blot analysis revealed that TRα1 expression was 2.95-fold higher in the kidneys of ZSF1 rats than in lean controls (ZSF1, 17.50 ± 2.67 vs. lean, 5.94 ± 2.5, P < 0.05) (Figure 2B). Immunofluorescence analysis showed increased expression of TRα1 in nestin-positive podocytes and parietal cells of diabetic rats, compared with lean controls, where glomerular TRα1 expression was almost absent (Figure 2, C and D). In contrast, TRβ1 expression was higher in nestin-positive podocytes of lean control rats than in ZSF1 rats (Figure 2, C and D). Analysis of biopsies from patients with DN and control subjects consistently confirmed the TRα1 and TRβ1 expression pattern observed in diabetic and lean rats, respectively (Figure 2, E and F).

Figure 2. Adoption of fetal expression pattern of TRs and DIO3 during DN.

(A) Western blot and densitometric analysis of TRα1 protein levels. TRα1 was highly expressed in rat embryonic kidneys (E13.5–E18.5) and significantly reduced after birth. Data are expressed as mean ± SEM. *P < 0.0001 vs. P7 and adult, †P < 0.0005 vs. adult, #P < 0.0005 vs. P4, §P < 0.01 vs. P4 and P7, 1-way ANOVA corrected with Tukey’s post hoc test. n = 20 E13.5, n = 16 E15.5, n = 12 E18.5, n = 3 postnatal and adult kidneys. (B) TRα1 levels increased in kidneys of ZSF1 rats compared with lean rats at 6 months of age. *P < 0.05, unpaired Student’s t test. n = 4 rats per group. (C–F) Representative images of TRα1 and TRβ1 protein stainings in kidney sections from (C) lean and (D) ZSF1 rats and in (E) portions of control human kidney tissue and (F) from renal biopsies of DN patient. TRα1 (red) was expressed in nestin-positive (green) podocytes and parietal cells of ZSF1 rats and DN patients, while it was almost absent in lean rats and control human tissue (C–F, left). Conversely, TRβ1 (red) was highly expressed in glomerular tuft and podocytes of lean rats and human controls, while it was lower in ZSF1 rats and DN patients (C–F, right). n = 3 rats and n = 3 human subjects per group. (G) Western blot and densitometric analysis of DIO3 protein levels (left). DIO3 levels increased in kidneys of ZSF1 rats compared with lean rats. Representative images of DIO3 staining in lean and ZSF1 rat kidneys (right). DIO3 was highly expressed in glomerular tuft, parietal cells, and podocytes of ZSF1 rats (right, arrows). Data are expressed as mean ± SEM. **P < 0.01, unpaired Student’s t test. n = 4 rats per groups. Tubulin protein expression was used as sample loading control. Scale bars: 20 μm. LCA, Lens culinaris agglutinin.

To examine if the TH-inactivating enzyme DIO3 was involved in the alterations in TH signaling observed in diabetes, we investigated DIO3 expression and localization in the kidneys of ZSF1 and lean rats. DIO3 protein expression was 3.74-fold higher in diabetic rats than in the lean controls (ZSF1, 8.35 ± 1.26 vs. lean, 2.23 ± 0.73, P < 0.01) (Figure 2G); it was expressed extensively in the glomerular tuft, parietal cells, and in podocytes of diabetic rats (Figure 2G, inset, and Supplemental Figure 1A; supplemental material available online with this article; https://doi.org/10.1172/jci.insight.130249DS1), while it was absent in control rats.

These data demonstrate the adoption of the fetal TH signaling profile (low T3/high TRα1 and high DIO3) by kidneys of rats and patients with DN.

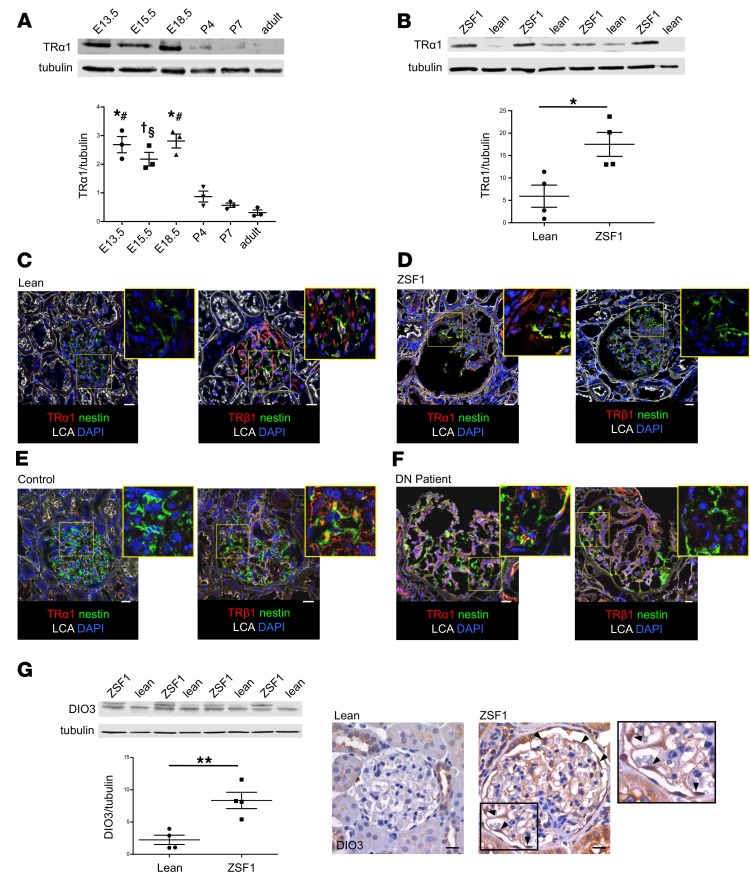

TRα1 upregulation is associated with the reactivation of kidney developmental programs during DN.

To assess whether the fetal ligand/receptor relationship pattern was associated with the reactivation of further developmental pathways, we analyzed the expression of embryonic kidney markers in renal specimens from ZSF1 rats. Western blot analysis showed a significantly increased expression of molecules that are essential for kidney development, such as paired box 2 (Pax2) (29), SIX homeobox 2 (Six2) (30), and glial cell line–derived neurotrophic factor (GDNF) (31) in the kidneys of rats with DN compared with lean rats (Pax2, 2.95-fold; Six2, 1.50-fold; and GDNF, 1.71-fold higher than in controls) (Figure 3, A–C). Immunostaining assays demonstrated that embryonic markers were expressed extensively in the glomerular tuft, in nestin-positive podocytes, parietal cells, and in some tubules of ZSF1 rats. In the glomeruli of lean rats we detected only faint expression of these embryonic markers (Figure 3, A–D). Further investigations in serial sections with colocalization analysis showed that most of fetal marker-positive cells were also expressing TRα1, indicating that TRα1 could be involved in their abnormal reactivation (Figure 3, A–C). In line with these findings, we also observed an increased expression of desmin, a mesenchymal marker (32), which colocalized with TRα1-positive cells in glomeruli of diabetic rats (Supplemental Figure 1, B and C). Moreover, the expression of the GDNF receptor tyrosine kinase (Ret) and the GDNF family receptor α 1 (GFRα1) — proteins that are known to be expressed by podocytes during development and injury (33) — increased markedly in ZSF1 rats (Ret, 2.73-fold, and GFRα1, 1.54-fold higher than in the lean control) and were localized in podocytes and parietal cells (Figure 3, E and F). To examine whether the combined alterations in TH signaling and reactivation of fetal kidney genes is common between different diabetes models and species, we studied stored samples from ZDF rats (tissue and sera) and BTBRob/ob and streptozotocin-treated C57BL/6 mice (tissues). The results showed that the serum T3 levels were significantly lower in ZDF rats than in lean controls and that TRα1, DIO3, Six2, and Pax2 were higher in the glomeruli of all diabetic animals (Supplemental Figure 2).

Figure 3. TRα1 reexpression is associated with reactivation of kidney developmental program in diabetic rats.

(A–C) Expression of fetal markers in kidneys of ZSF1 and lean rats at 6 months of age. Western blot and densitometric analysis of (A) Pax2, (B) Six2, and (C) GDNF protein levels in ZSF1 rats compared with lean rats (left). Representative images of TRα1 and (A) Pax2, (B) Six2, and (C) GDNF stainings on serial sections in lean and ZSF1 rats (right). Fetal markers were highly expressed in the glomerular tuft and parietal cells of ZSF1 rats. (D) Representative images of nestin-positive podocytes (green) expressing Pax2 (red; top) and Six2 (red; bottom) in kidney sections of diabetic rats. (E and F) Western blot and densitometric analysis of (E) Ret and (F) GFRα1 protein levels in ZSF1 rats compared with control rats (left). Representative images of (E) Ret and WT-1 and (F) GFRα1 and nestin stainings in lean and ZSF1 rats (right). Ret and GFRα1 (red) expression significantly increased in kidneys of ZSF1 rats compared with lean rats. Data are expressed as mean ± SEM. *P < 0.05, unpaired Student’s t test. n = 3–4 rats per group. Tubulin protein expression (A) or ponceau red staining (B, C, E, and F) was used as sample loading control. Scale bars: 20 μm. LCA, Lens culinaris agglutinin.

Together, these data indicate that diabetes induces a partial reactivation of the kidney developmental program in the glomerulus of ZSF1 rats, in which the TH-TRα1 axis is involved.

Hypertrophic and polynucleated podocytes are detected in ZSF1 rats.

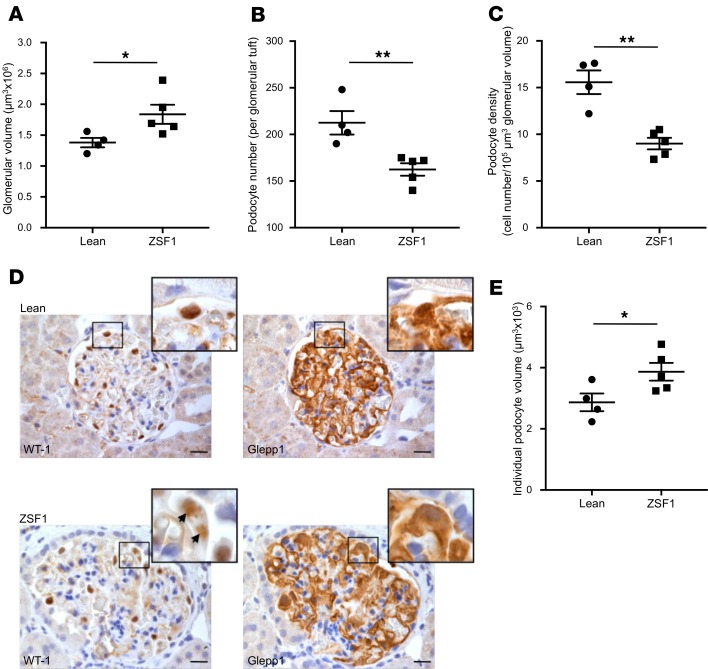

Glomerular and podocyte hypertrophy is a hallmark of DN and has been extensively documented in patients with DN and in some rodent models of diabetes (34, 35); however, in ZSF1 rats, podocyte hypertrophy has not been described yet. Thus, 6-month-old ZSF1 and lean rats were analyzed for glomerular volume; podocyte number and density, which was defined as the ratio between podocyte number and glomerular volume; and individual podocyte volume, which was obtained by the ratio between total glomerular podocyte volume and podocyte number. The overall glomerular volume was significantly higher (ZSF1, 1.84 ± 0.16 μm3 × 106 vs. lean, 1.38 ± 0.07 μm3 × 106, P < 0.05) (Figure 4A), while the number of WT-1 positive podocytes was significantly lower (ZSF1 163 ± 7 vs. lean 213 ± 13, P < 0.01) (Figure 4B) in ZSF1 rats compared with lean rats. As a result, podocyte density was markedly reduced in ZSF1 rats compared with lean controls (ZSF1, 9.01 ± 0.61 cell number/105 μm3 glomerular volume vs. lean, 15.60 ± 1.26 cell number/105 μm3 glomerular volume, P < 0.01) (Figure 4C). We then calculated the total podocyte volume per glomerulus, measuring the percentage of area that was positive for Glepp1, a podocyte apical cell membrane marker. Although podocyte number was significantly reduced, we surprisingly found that Glepp1 expression was only moderately decreased in ZSF1 rats compared with lean rats (ZSF1, 36.7% ± 2.9% vs. lean, 43.6% ± 1.5%), while the Glepp1-positive tuft volume, which was estimated by multiplying the percentage of Glepp1-positive area and the glomerular volume, did not change (ZSF1 6.9 ± 1.2 μm3 × 105 vs. lean 6.0 ± 0.3 μm3 × 105). As explanation of these data, individual podocyte volume was significantly increased in ZSF1 rats compared with lean controls (ZSF1, 3.87 ± 0.29 μm3 × 103 vs. lean, 2.9 ± 0.3 μm3 × 103, P < 0.05) (Figure 4, D and E), highlighting the presence of significant podocyte hypertrophy. Moreover, we occasionally observed hypertrophic podocytes with 2 nuclei (Figure 4D, inset, arrows).

Figure 4. Glomerular volume and podocyte depletion and hypertrophy in ZSF1 rats.

(A and B) Quantification of glomerular volume and WT-1–positive podocytes in lean and ZSF1 rats at 6 months of age. Diabetic rats exhibited (A) increased glomerular volume, (B) decreased number of podocytes per glomerulus, and (C) lower podocyte density compared with lean controls. (D) Representative images of WT-1 and Glepp1 staining on serial sections in lean and ZSF1 rats. Insets show enlarged images of podocytes and highlight a polynucleated podocyte. (E) Quantification of individual podocyte volume in lean and ZSF1 rats. Diabetic rats had significantly greater podocyte volume compared with lean controls. Data are expressed as mean ± SEM. *P < 0.05; **P < 0.01, unpaired Student’s t test. n = 4–5 rats per group. Scale bars: 20 μm.

These data clearly document the presence of both glomerular and podocyte hypertrophy in ZSF1 diabetic rats and that this hypertrophy was associated with the occurrence of polynucleated podocytes.

TH signaling alterations drive podocyte cytoskeleton rearrangement and dedifferentiation in vitro that are totally reversed by T3 treatment.

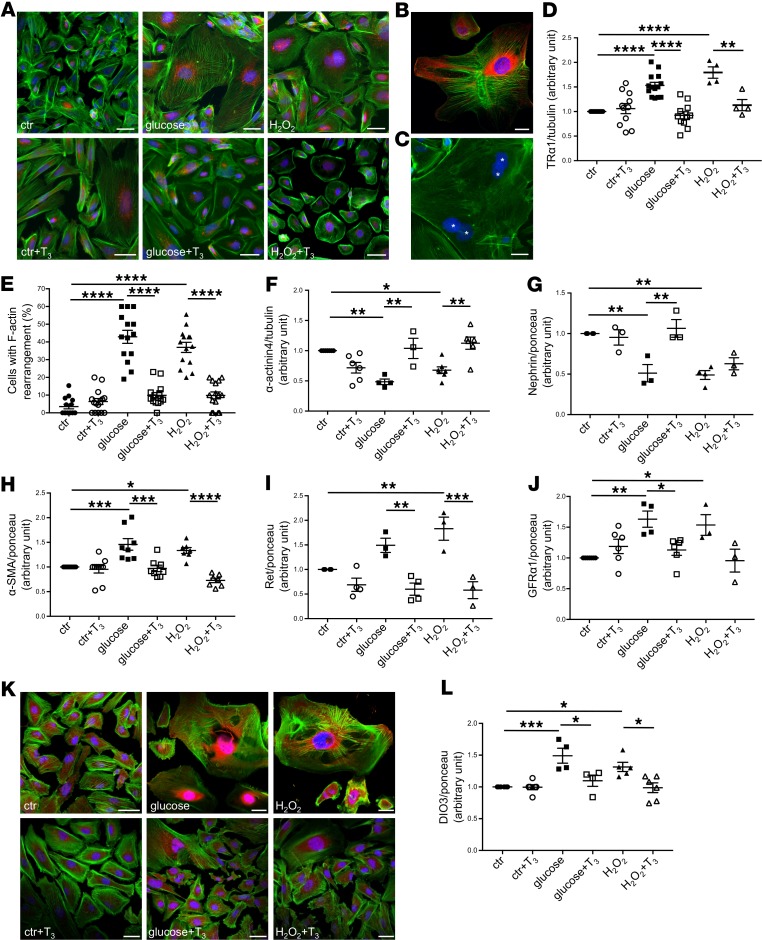

To study the role of TRα1 in inducing the molecular and phenotypical changes observed in vivo in podocytes that are damaged by DN, we cultured human immortalized podocytes in the presence of high glucose concentration and reactive oxygen species (H2O2) — key components of the diabetic milieu — for 9 days. Immunofluorescence analysis showed that some untreated cells expressed TRα1 in the nuclear and perinuclear areas. High glucose and H2O2 treatment markedly increased cell size and TRα1 expression compared with controls; in large cells, TRα1 was highly expressed in the cytoplasm (Figure 5A, top, and Figure 5B). Polynucleated cells were visible after high glucose treatment (Figure 5C, asterisks).

Figure 5. High glucose and oxidative stress induce TRα1 reexpression and podocyte dedifferentiation in vitro that are reversed by T3.

(A) Representative images of TRα1 (red) and F-actin (green) staining in human podocytes. Both high levels of glucose and H2O2 induced TRα1 overexpression and partial translocation from the nucleus to cytoplasm and increased cell size (top). T3 treatment of stimulated podocytes decreased TRα1 expression and restored its nuclear and perinuclear localization, and reduced cell size, but had no effect on control cells (bottom). (B) A representative image of TRα1 (red) and F-actin (green) staining of injured podocytes. (C) Multinucleated podocytes were visible after glucose treatment (asterisks). (D) Densitometric analysis of TRα1 protein levels in podocytes by Western blot. Both glucose and H2O2 increased TRα1 expression significantly, and T3 treatment markedly reversed this effect. (E) Quantification of podocytes with peripheral F-actin distribution. Diabetic stimuli caused F-actin rearrangements that were reversed by T3. (F–J) Densitometric analysis of (F) α-actinin4, (G) nephrin, (H) α-SMA, (I) Ret, and (J) GFRα1 proteins by Western blot. Diabetic stimuli decrease the expression of adult podocyte markers (F and G), cause the reexpression of the mesenchymal marker α-SMA (H), and increase Ret (I), and GFRα1 (J) protein levels. T3 treatment markedly reversed all these changes. (K) Representative images of DIO3 (red) and F-actin (green) staining in human podocytes. Both high glucose and H2O2 stimulation induced DIO3 upregulation mostly in the nuclear and perinuclear regions (top). T3 treatment of injured podocytes decreased DIO3 expression while having no effect on control cells (bottom). (L) Densitometric analysis of DIO3 protein levels in podocytes by Western blot. Both glucose and H2O2 markedly increased DIO3 expression compared with control. T3 treatment reversed this effect. Data from 3 independent experiments are expressed as mean ± SEM. *P < 0.05; **P < 0.01; ***P < 0.001; ****P < 0.0001, 1-way ANOVA corrected with Tukey’s post hoc test. n = 3–15 samples per each condition. Tubulin protein expression (D and F) or ponceau red staining (G–J and L) was used as loading control. Scale bars: 50 μm.

According to the dual-function model for the role of TRs in postembryonic development of some mammalian organs (36) and in the metamorphosis of amphibians, TRα1 can (a) repress target genes that are involved in differentiation to allow tissue/organ growth in the absence of TH or (b) bind TH and induce the previously repressed genes and others to initiate tissue/organ maturation following TH release into the circulation. Based on this knowledge, we tested whether adding T3 to the environment could induce TRα1 to reverse the injury-induced pathological reactivation of the podocyte developmental program, thus restoring a more mature podocyte phenotype. We exposed human podocytes to high glucose or H2O2 for 3 days and then to each stimulus in combination with T3 for an additional 6 days. Treatment with T3 reduced cell size and shifted the TRα1 localization from the cytoplasm to the nuclear and perinuclear areas of both glucose- and H2O2-stimulated podocytes (Figure 5A, bottom). Western blot analysis showed that both high glucose (1.53 ± 0.06 vs. control, P < 0.0001) and H2O2 (1.80 ± 0.12 vs. control, P < 0.0001) increased TRα1, while T3 restored TRα1 to control levels (glucose + T3, 0.92 ± 0.07, H2O2 + T3, 1.13 ± 0.11) (Figure 5D).

In DN, foot process effacement and cell retraction are observed in podocytes, as a consequence of cytoskeletal rearrangements. To investigate whether the restoration of the adult ligand/receptor relationship pattern — obtained through the administration of T3 — could reverse the morphological changes in podocytes damaged by high glucose and oxidative stress, we analyzed changes in the actin-based cytoskeleton of podocytes exposed to high glucose or H2O2 treated or not with T3. As expected, untreated podocytes showed F-actin fibers arranged in parallel and extended across the entire cell body, while exposure to high glucose or H2O2 induced F-actin rearrangement at the cell periphery in 42.92% ± 3.67% and 36.96 % ± 2.85% of podocytes, respectively, compared with 3.53% ± 1.31% of untreated cells. Notably, treatment with T3 induced F-actin redistribution and alignment, reestablishing an actin-based cytoskeleton similar to that observed in control cells (glucose + T3, 9.86% ± 1.56%; H2O2 + T3, 9.84% ± 1.95%) (Figure 5E).

Moreover, T3 treatment in human podocytes (a) restored the expression of the adult podocyte markers α-actinin4 (glucose + T3, 1.04 ± 0.17 vs. glucose, 0.48 ± 0.04, P < 0.01; H2O2 + T3, 1.12 ± 0.10 vs. H2O2, 0.68 ± 0.05, P < 0.01) and nephrin (glucose + T3, 1.06 ± 0.11 vs. glucose, 0.51 ± 0.11, P < 0.01; H2O2 + T3, 0.63 ± 0.07 vs. H2O2, 0.49 ± 0.05) to control levels (Figure 5, F and G); (b) reversed the diabetic stimuli–induced upregulation of the mesenchymal marker α-SMA (glucose + T3, 0.97 ± 0.06 vs. glucose, 1.46 ± 0.11, P < 0.001; H2O2 + T3, 0.73 ± 0.05 vs. H2O2, 1.33 ± 0.06, P < 0.0001) (Figure 5H); and (c) normalized the high glucose– and H2O2-induced upregulation of Ret (glucose + T3, 0.60 ± 0.13 vs. glucose, 1.49 ± 0.14, P < 0.01; H2O2 + T3, 0.58 ± 0.17 vs. H2O2, 1.83 ± 0.24, P < 0.001) and GFRα1 (glucose+T3, 1.13 ± 0.09 vs. glucose, 1.63 ± 0.13, P < 0.05; H2O2 + T3, 0.96 ± 0.18 vs. H2O2, 1.54 ± 0.17) (Figure 5, I and J) that we also observed in vivo in diabetic rats (Figure 3, E and F). T3 treatment also restored the normal DIO3 expression pattern in injured podocytes (glucose + T3, 1.10 ± 0.09 vs. glucose, 1.49 ± 0.12, P < 0.05; H2O2 + T3, 0.99 ± 0.08 vs. H2O2, 1.31 ± 0.07, P < 0.05) (Figure 5, K and L).

Together these data indicate that high glucose and oxidative stress induced the overexpression of TRα1 and, concurrently, podocyte dedifferentiation and reactivation of fetal genes, structural remodeling, and cell growth. The ability of T3 to normalize TRα1 and DIO3 expression and totally reverse injury-induced phenotypical and molecular changes demonstrates that the TH-TRα1 axis is crucially involved in DN-associated podocyte damage.

T3 administration enables the cytokinesis in diabetic stress–damaged podocytes in vitro.

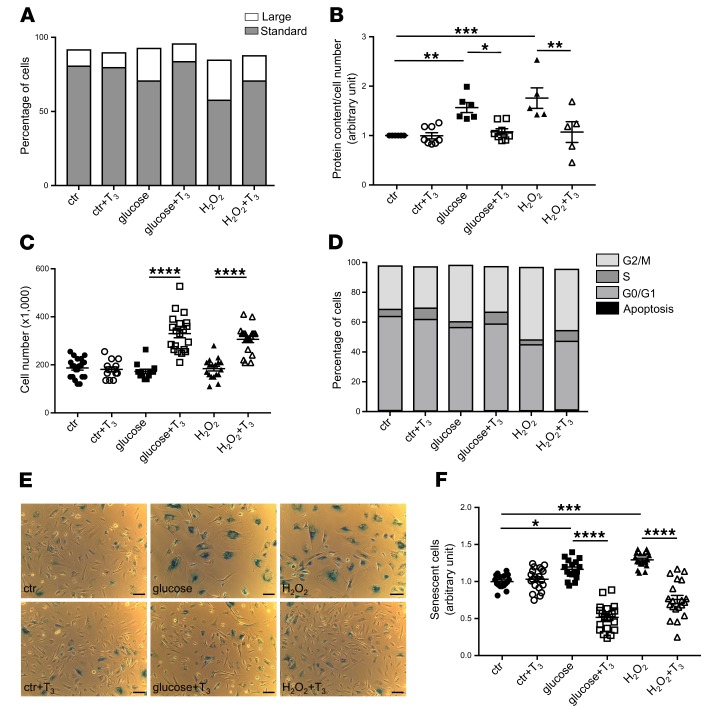

To study in depth the role of TH signaling in changes in podocyte size, we performed FACS analysis of untreated and treated human podocytes. Using forward-scattered light (FSC) versus side-scattered light (SSC) scatter plots, we obtained 2 podocyte subpopulations: cells of normal size that we named “standard cells,” and cells of increased dimensions that we called “large cells.” Scatter plot analysis showed that exposure to high glucose increased the percentage of large cells markedly (glucose, 27.50% ± 2.06% vs. untreated cells, 15.93% ± 1.98%, P < 0.01) and, as a consequence, decreased the percentage of standard cells (glucose, 69.47% ± 1.74% vs. untreated cells, 81.50% ± 1.36%, P < 0.05) (Figure 6A). Similar effects were observed in H2O2-stimulated podocytes (large cells, 30.03 % ± 2.19% vs. untreated cells, P < 0.001; standard cells, 58.00% ± 0.58% vs. untreated cells, P < 0.0001) (Figure 6A). Treating control podocytes with T3 did not alter cell distribution compared with untreated cells (large cells, 15.25% ± 2.78%; standard cells, 80.23% ± 2.04%), while treating glucose- or H2O2-stimulated podocytes with T3 significantly decreased the fraction of large cells (glucose + T3, 14.28% ± 0.99% vs. glucose, P < 0.01; H2O2 + T3, 17.48% ± 0.51% vs. H2O2, P < 0.01) and significantly increased the fraction of standard cells (glucose + T3, 82.07% ± 1.53% vs. glucose, P < 0.01; H2O2 + T3, 76.53% ± 3.65% vs. H2O2, P < 0.001) (Figure 6A and Supplemental Figure 3, A and B).

Figure 6. T3 administration induces cell proliferation and restores cell size and normal cell cycle distribution in damaged podocytes.

(A) Percentage of standard or large treated and untreated podocytes analyzed with FACS by plotting FSC (as dimension of cells) versus SSC (as granularity of cells). Both high levels of glucose and H2O2 increased the large cell population and T3 restored the standard cell size. (B) Quantification of hypertrophy expressed as total protein content per cell number. Diabetic stimuli induced cell hypertrophy and T3 reversed this effect. (C) Quantification of cell number in treated and untreated podocytes by manual cell counting. T3 strongly increased proliferation in podocytes exposed to high levels of glucose or H2O2. (D) A representative graph of the percentage of podocytes in the cell cycle phases evaluated by FACS. Diabetic stimuli induced a marked G2/M accumulation, while T3 administration reduced G2/M phase arrest and increased S phase cells. T3 treatment had no effect on cell size, hypertrophy, proliferation, and cell cycle distribution in control podocytes. Data from 3 independent experiments are expressed as mean ± SEM. (E) Representative images of senescence-associated β-galactosidase (SA-β-Gal) staining in cultured human podocytes. Scale bar: 100 μm. (F) Quantification of senescent podocytes expressed as SA-β-Gal–positive cells per cell number. Both stress stimuli increased the numbers of SA-β-Gal–positive cells (blue) compared with control, while T3 administration strongly reduced the amount of senescent cells. SA-β-Gal activity did not differ between control groups. To quantify the number of positive cells, representative images were taken randomly from diverse areas of cell cultures. Number of fields analyzed: n = 17 for ctr, n = 20 for ctr+T3, n = 17 for glucose, n = 20 for glucose+T3, n = 19 for H2O2, n = 20 for H2O2+T3. Data are expressed as mean ± SEM. *P < 0.05; **P < 0.01; ***P < 0.001; ****P < 0.0001, 1-way ANOVA with Tukey’s post hoc test.

We then measured the total protein content/cell number to evaluate the effect of T3 treatment on cell hypertrophy. Both high glucose and H2O2 caused a significant increase in podocyte hypertrophy (1.57 ± 0.10–fold and 1.76 ± 0.21–fold vs. control, respectively), and this effect was reversed by T3 treatment (glucose + T3, 1.08 ± 0.06–fold and H2O2 + T3, 1.07 ± 0.21–fold vs. control) (Figure 6B). Interestingly, T3 also had a significant proliferative effect in glucose- and H2O2-stimulated podocytes, while it did not alter cell number of control podocytes (Figure 6C).

We used FACS analysis to further evaluate the proliferative effect of T3 and the possible changes in cell cycle distribution in untreated and treated human podocytes. Exposure to high glucose caused a persistent G2/M accumulation (1.56 ± 0.11–fold vs. control, P < 0.001) that was similar to that observed in H2O2-stimulated podocytes (1.81 ± 0.14–fold vs. control, P < 0.0001), indicating hypertrophic podocytes inability to conclude cytokinesis. Treating glucose- or H2O2-stimulated podocytes with T3 decreased the G2/M phase arrest (glucose + T3, 1.01 ± 0.04 vs. glucose, 1.56 ± 0.11, P < 0.01; H2O2 + T3, 1.27 ± 0.08 vs. H2O2, 1.81 ± 0.14, P < 0.01) and increased S phase cells markedly (glucose + T3, 1.98 ± 0.34 vs. glucose, 0.97 ± 0.07, P < 0.001; H2O2+T3, 1.28 ± 0.07 vs. H2O2, 0.78 ± 0.04) (Figure 6D and Supplemental Figure 3D). According to the cell number quantification (Figure 6C), T3 treatment did not induce any changes in G2/M and S phase in control podocytes (G2/M: control + T3, 1.05 ± 0.03-fold vs. control; S: control + T3, 1.08 ± 0.13-fold vs. control) (Supplemental Figure 3, C and D). Together, these data clearly demonstrate that high glucose and oxidative injury induced podocytes to reenter the cell cycle, where they arrested in the G2/M phase undergoing hypertrophy; in these podocytes, T3 enabled cytokinesis, which translated into hypertrophy reduction and cell number increase (Figure 6, B and C). Since diabetes-induced cell cycle arrest is linked to premature senescence (37, 38), we tested whether TH signaling plays a role in this process. Both high glucose and H2O2 caused a significant increase in the number of senescence-associated β-galactosidase–positive (SA-β-Gal–positive) podocytes (39), and this effect was again reversed by T3 treatment (Figure 6, E and F), indicating that TH signaling plays an important role in diabetes-associated podocyte senescence and that its activation results in strong antiaging effects.

TRα1 induces hypertrophy through the ERK1/2 pathway.

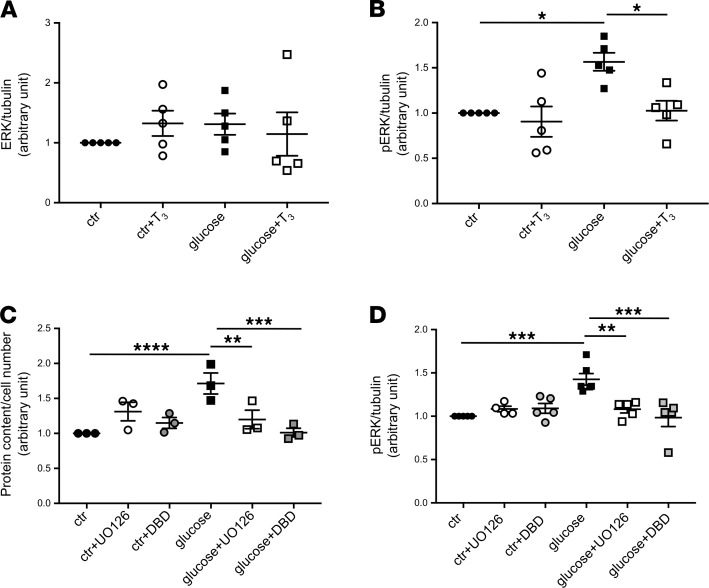

To identify the underlying mechanisms of action of TRα1, we analyzed changes in ERK1/2 signaling pathways, which are regulated by the TH-TR axis and involved in hypertrophy, dedifferentiation, proliferation, and apoptosis (40). Neither high glucose nor T3 treatment affected basal ERK1/2 expression (control + T3, 1.32 ± 0.21; glucose, 1.31 ± 0.18; and glucose + T3, 1.15 ± 0.36-fold vs. control) (Figure 7A), while high glucose significantly increased phospho-ERK1/2 (pERK1/2) (1.57 ± 0.10 vs. control, P < 0.05) that was restored to control levels through T3 treatment (glucose + T3, 1.03 ± 0.11 vs. glucose, P < 0.05) (Figure 7B). The activation of ERK1/2 after glucose stimulation and its modulation by T3 treatment suggested that ERK1/2 plays a role as a TRα1 mediator for cell hypertrophy in podocytes in vitro. To confirm our hypothesis, we first tested whether this glucose-induced alteration was indeed mediated by ERK1/2 by treating podocytes with a subtoxic concentration of UO126 — an inhibitor of ERK1/2 phosphorylation — alone or in combination with high glucose for 9 days. We observed that UO126 treatment impeded the establishment of hypertrophy induced by glucose alone (glucose + UO126, 1.20 ± 0.13 vs. glucose, 1.71 ± 0.15, P < 0.01) (Figure 7C), demonstrating that ERK1/2 is a mediator of hypertrophy in glucose-stimulated podocytes. Second, to confirm that TRα1 plays a role in regulating hypertrophy in glucose-stimulated cells, we treated podocytes with debutyl-dronedarone (DBD) — a TRα1 inhibitor (41) — alone or in combination with high glucose for 9 days. Treatment with DBD, in combination with glucose, blocked the hypertrophy that was induced by glucose alone (glucose + DBD, 1.01 ± 0.06 vs. glucose, 1.71 ± 0.15, P < 0.001) (Figure 7C), demonstrating that TRα1 is necessary for hypertrophy induction. Finally, to assess whether ERK1/2 acts downstream in the TRα1 pathway, we evaluated the expression of pERK1/2 after DBD treatment (Figure 7D). Remarkably, treatment with DBD prevented ERK1/2 activation (glucose + DBD, 0.98 ± 0.10 vs. glucose, 1.43 ± 0.07, P < 0.001) as much as UO126 treatment did (glucose + UO126, 1.08 ± 0.04 vs. glucose, P < 0.01) (Figure 7D). Neither UO126 nor DBD affected pERK1/2 levels in control podocytes (Figure 7D).

Figure 7. TRα1 regulates glucose-induced hypertrophy through downstream activation of ERK1/2.

(A and B) Densitometric analysis of (A) ERK1/2 and (B) pERK1/2 protein in podocytes by Western blot. (A) Podocyte total ERK1/2 protein expression was not changed either by glucose or T3 treatment. (B) Glucose induced an increase in pERK1/2 protein levels, which were significantly reduced by T3 treatment. (C) Quantification of hypertrophy expressed as protein content per cell number. Glucose induced podocyte hypertrophy, which was prevented by UO126 and DBD. Neither UO126 nor DBD had any effect on untreated cells. (D) Densitometric analysis of pERK1/2 protein in podocytes by Western blot. The increase in pERK1/2 protein levels in glucose-stimulated podocytes was prevented by administering UO126 or DBD. Tubulin protein expression was used as sample loading control (A, B, and D). Data from 3 independent experiments are expressed as mean ± SEM. *P < 0.05; **P < 0.01; ***P < 0.001; ****P < 0.0001, 1-way ANOVA with Tukey’s post hoc test. n = 3–6. pERK1/2, phospho-ERK1/2.

These findings indicate that the TRα1 is responsible for hypertrophy induction and its action is mediated downstream by the ERK1/2 pathway (Figure 8).

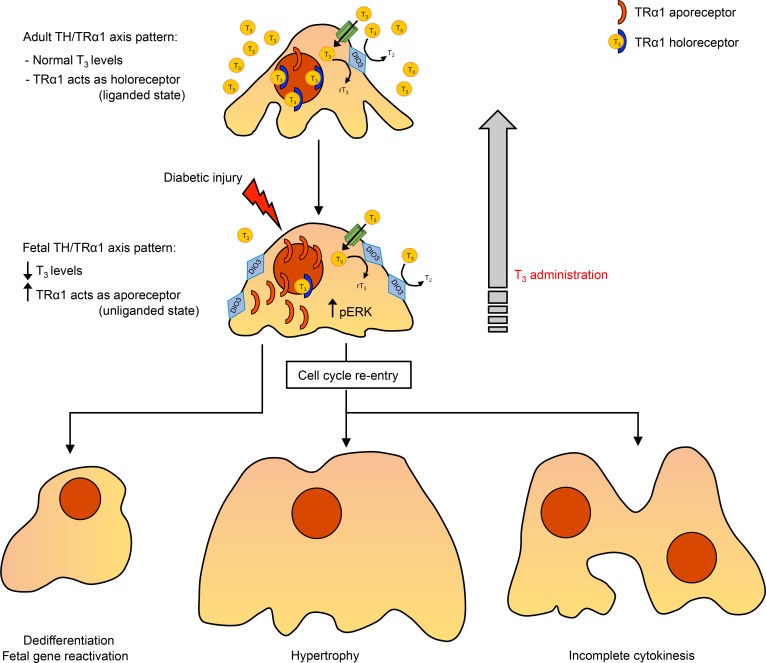

Figure 8. TH/TRα1 axis actions in diabetes.

In healthy podocytes, T3 levels are maintained within a physiological range and TRα1 acts as holoreceptor. Local T3 availability is controlled by the T3-inactivating enzyme DIO3, which converts excessive T3 into rT3 and T2. In response to diabetic injury, systemic T3 levels drop markedly, and TRα1 and DIO3 are overexpressed locally, resulting in the coordinated adoption of the fetal ligand/receptor relationship profile (i.e., low T3 availability/high local TRα1). Here, TRα1 acts as aporeceptor (as happens in the fetus), repressing adult genes, triggering the reactivation of the podocyte developmental program, activating ERK1/2, and inducing cells to reenter the cell cycle. Unable to complete cytokinesis, mitotically activated podocytes become hypertrophic and polynucleated. T3 treatment switches TRα1 to the holoreceptor state (as happens after birth), promoting a mature cell phenotype and globally reversing the phenotypical alterations induced by diabetes. rT3, reverse L-triiodothyronine; T2, L-diiodothyronine.

Discussion

Low systemic T3 level is the most frequent alteration of the TH signaling profile that is observed in chronically ill patients (42). This alteration has long been considered as a harmless metabolic adaptation to chronic illness. However, recent evidence shows that alterations of the TH signaling profile associate with radical phenotypical changes in terminally differentiated cells of various types (i.e., cardiomyocytes [ref. 43], pancreatic cells [ref. 44], neuronal cells [ref. 45], and skeletal muscle cells [ref. 46]). Both the changes in T3 availability and in podocytes’ phenotype have been already reported in DN; however, whether these phenomena are interconnected or not is still unknown.

This study is the first to our knowledge to demonstrate that the TH-TR axis adopts a fetal relationship profile in kidney in response to diabetic stress that may play a pivotal role in the diabetes-induced pathological growth, remodeling, and dedifferentiation of podocytes and identifies TRα1 as a key regulator of the pathogenesis of DN.

By analyzing ZSF1 diabetic rats at different stages of DN, we observed a progressive decrease in T3 availability that paralleled the worsening of metabolic disease, the increase of proteinuria, and the onset of glomerular structural alterations. The reduction of T3 levels was accompanied by the reexpression of the predominantly fetal TR isoform TRα1 in podocytes and parietal cells of diabetic rats, and similar expression patterns were observed in patients with DN. Moreover, the expression of the TH-inactivating enzyme DIO3 also increased at the glomerular level in ZSF1 diabetic rats. TRα1 is highly expressed during fetal life, when T3 levels are low, and acts as aporeceptor (unliganded state) to repress adult genes. After birth, a significant increase in T3 levels occurs and TRα1 switches to holoreceptor (liganded state) to induce the expression of adult genes and promote cell maturation and physiological growth. Local T3 availability is controlled by DIO3 in a spatiotemporal manner during organ development and maturation. Specifically, DIO3 is highly expressed in fetal tissues to inactivate intracellular T3 and enable cell proliferation and physiological growth. Around birth, DIO3 expression is turned off in virtually every tissue to enable the local increase in T3 and subsequent cell differentiation and tissue maturation (47); these changes drive the fetal-to-adult switch in gene expression. Robust local reexpression of DIO3 has been observed in adulthood in fish epimorphic regeneration (48) and in mammals in conditions under which low TH is necessary to sustain cell proliferation and growth, as in inflammation (49, 50), tumors (51), and liver regeneration (52) as well as in the surviving cardiomyocytes after myocardial infarction (53). Here, we report that DIO3 also increases locally in the diabetic kidney and that this is associated with low T3 levels and the overexpression of TRα1. Together, these findings indicate that TH signaling coordinately adopts a fetal ligand/receptor relationship profile (i.e., low T3 availability/high local TRα1 and high DIO3) that may be responsible for the fetal/dedifferentiation features observed in diabetic podocytes. This hypothesis is strengthened by the fact that, in ZSF1 rats, TRα1 increased massively in cells that also expressed fetal kidney markers as well as in dedifferentiating desmin-positive podocytes. To dissect the biological significance of the recapitulation of the fetal profile of TH signaling and its link with diabetic podocyte alterations, we performed mechanistic studies in vitro. In podocytes treated with high glucose or H2O2, we observed a strong increase of TRα1 expression that was associated with changes in the actin-based cytoskeleton, downregulation of adult podocyte markers, upregulation of mesenchymal markers, and increased expression of Ret, GFRα1, and DIO3. Moreover, high glucose and oxidative injury induced podocytes to reenter the cell cycle, which they were unable to conclude, and remained blocked in the G2/M phase undergoing hypertrophy. Strikingly, T3 treatment globally reversed the changes observed in stimulated podocytes and enabled the completion of cytokinesis, demonstrating that TH signaling is a key player in the phenotypical and molecular changes that occur in podocytes in response to exposure to the typical components of the diabetic milieu. It is important to highlight that in the absence of any injury T3 did not affect cell cycle or growth, suggesting that the T3-mediated proliferative effect occurs exclusively in damaged podocytes. Finally, to investigate the pathways underlying the effects of TRα1 overexpression, we performed pharmacological studies with specific inhibitors and identified ERK1/2 as the downstream mediator of the TH-TRα1 axis in inducing podocyte hypertrophy.

TRα1 acting as a molecular switch that triggers the recapitulation of the fetal cell phenotype in response to injury in terminally differentiated and highly specialized cells has also been observed in cardiomyocytes. Stress stimuli, such as adrenergic stimulation induced the upregulation of TRα1 in isolated cardiomyocytes (54), reexpression of fetal structural proteins, and the adoption of fetal-like morphology in terms of cellular structure, size, shape, and geometry (55). As we observed in diabetic podocytes, stress-induced morphological and molecular alterations of the cardiomyocytes were mediated by ERK1/2, and T3 treatment reduced TRα1 expression, reversed the fetal-like pattern of contractile protein expression, both in vitro and in vivo, and normalized wall tension and cardiac chamber geometry in experimental heart disease (56). Of great interest, changes in the TH-TRα1 axis have also been observed in the diabetic heart (57–59), the ischemic brain (60), and injured skeletal muscle (61). These observations, in combination with our data, suggest that the TH-TRα1 axis is a highly sensitive pleiotropic pathway that is able to respond to a wide range of different noxious stimuli (including hemodynamic, ischemic and adrenergic, high glucose, and oxidative stress) and induce profound phenotypical changes in adult injured tissues. The significant differences between hypothyroidism- and diabetes-induced phenotypical changes (atrophy vs. hypertrophy; unchanged podocyte number vs. podocyte loss, respectively) (62,63) indicate that the low availability of T3 alone does not suffice to trigger the recapitulation of the fetal podocyte phenotype and remodeling; one or more chronic noxious stimuli are required to induce TH signaling to adopt its fetal ligand/receptor relationship profile (i.e., low T3 availability/high local TRα1), which in turn triggers, and possibly coordinates, the dedifferentiation in diabetic podocytes.

One compelling question remains unanswered: why does the fetal TH signaling profile recur in diabetic podocytes? It could be either an adaptation to chronic illness (e.g., inducing a low energy state and/or compensatory growth) or a maladaptation (e.g., inducing phenotypical changes that are more harmful than beneficial). It is possible that low T3 indeed provides an initial metabolic benefit to the damaged cells and possibly allows the cells to grow in size to compensate increased work overload. However, persistent low availability of T3 induces also the changes in TH signaling that trigger the dedifferentiation and reactivation of downstream developmental pathways. In any case, based on the ubiquitous roles of TH signaling in the development of all vertebrates and epimorphic regeneration in various taxa (48, 64), we can hypothesize that the fetal relationship pattern being readopted (low T3/high TRα1) during chronic stress is an evolutionary remnant of TH-TR axis–mediated tissue regeneration (2). Though capable of initiating regeneration through developmental pathways, it fails to conclude the regeneration process because this ability has been lost during evolution with the increased complexity of mammalian organs. Hence, the phenotypical and morphological alterations in terminally differentiated podocytes in response to diabetic injury may be manifestations of an imperfect/maladaptive recapitulation of early developmental steps mediated by the TH/TRα1 axis (Figure 8). However, even if it is a maladaptive activation of developmental pathways, it can also be used as a window for regeneration: controlling these pathways spatiotemporally, it could be a strategy to direct the regeneration of damaged tissues. In light of the results reported here, one could propose that pharmacological modulation of the TH-TR axis through T3 treatment could potentially be a promising therapeutic strategy for reversing diabetes-induced pathological podocyte responses and hopefully to increase the regeneration potential of diabetic kidneys. Nevertheless, translating this strategy into clinical practice will not be easy. To achieve an efficient therapeutic effect on stressed cells (overexpressing both TRα1 and DIO3) under conditions of systemic hypothyroidism, very high doses of T3 would be needed; but this can cause various adverse effects — such as tachycardia, arrhythmias (65), hyperfiltration (66), dysfunction of the thyroid gland (67), and even death in the case of long-term treatment (68). As a matter of fact, when we tried to test the therapeutic potential of T3 treatment in diabetic rats (our unpublished data), we needed to use very high doses of T3 in order to reach an initial beneficial effect in function; however, this caused significant complications and we needed to interrupt the study. To minimize the adverse effects and maximize the reparative and regenerative capacities of TH, (our) future therapeutic approaches should be focused on developing a drug delivery technology that could (a) mainly (if not exclusively) target the stressed cells and (b) carry and deliver the TH into the cells of interest.

Although important research remains to be done to shed light on the role that TH signaling plays in the pathobiology of diabetic kidney, we can say that our data provide what we believe to be a novel perspective on the pathogenesis of DN and may provide a conceptual basis for developing potentially new regenerative therapeutic approaches.

Methods

Animals.

Male ZSF1 (ZSF1-Leprfa Leprcp/Crl) and aged-matched nondiabetic lean rats (ZSF1-Leprfa Leprcp/+) were obtained by Charles River Laboratories Italia. Animals were maintained in a specific pathogen–free facility and kept on a 12:12-hour-light/dark cycle with free access to water. ZSF1 rats were fed with the animal Purina 5008 diet (Charles River) containing 18 kJ% fat to accelerate the onset of diabetes. ZSF1 rats at 10 weeks of age underwent unilateral nephrectomy to accelerate the onset of renal disease. All animals were sacrificed at 6 months of age.

Sprague-Dawley (SD) rats (Crl:SD, Charles River Laboratories Italia) were used to study the TRα1 expression pattern in embryonic, postnatal, and adult kidneys. Matings for obtaining SD offspring were performed at Istituto di Ricerche Farmacologiche Mario Negri IRCCS. E13.5 (n = 20), E15.5 (n = 16), E18.5 (n = 12), P4 (n = 3), P7 (n = 3), and adult (n = 3) kidneys were isolated from SD rats.

Tissues from BTBR wild-type and BTBR Lepob/ob mice at 14 weeks of age, C57BL/6 wild-type mice injected intraperitoneally with saline or streptozotocin (200 mg/kg body weight, MilliporeSigma) as previously described (69), and 6-month-old Zucker diabetic fatty rats (ZDF/Gmi-fa/fa) and age-matched nondiabetic lean rats (ZDF/Gmi-fa/+) were used for immunohistochemical studies.

Sera from another set of ZDF and lean rats at 7 months of age were used for the determination of total T3 levels, as described below.

Urinary protein excretion measurements.

Urinary excretion of proteins was measured in 24-hour urine samples by the Coomassie method with a Cobas Mira autoanalyzer (Roche Diagnostics Systems).

T3 measurements.

Serum total T3 levels (T3, ng/dl) were measured using the tT3 total Triiodothyronine ELISA kit (catalog 125-300, Accubind Elisa Microwells, Monobind Inc.) following the manufacturer’s instructions. For T3 determination, serum from n = 3–9 lean rats and n = 5–10 ZSF1 rats and from n = 10 ZDF lean rats and n = 8 ZDF rats was used.

Renal histology.

Kidney samples were fixed in Duboscq-Brazil (catalog P0094, Diapath), dehydrated, and embedded in paraffin. Three-micrometer sections were stained with periodic acid–Schiff reagent, and at least 100 glomeruli were examined for each animal. The degree of glomerular damage was assessed by a semiquantitative scoring method (index) based on the number of glomeruli with sclerosis: grade 0, normal glomeruli; grade 1, up to 25% involvement; grade 2, up to 50% involvement; grade 3, up to 75%; and grade 4, greater than 75% sclerosis. The index was calculated as follows: [(1 × N1) + (2 × N2) + (3 × N3) + (4 × N4)]/(N0 + N1 + N2 + N3 + N4), where Nx is the number of glomeruli in each grade of glomerulosclerosis. Kidney biopsies were analyzed by the same pathologist, who was unaware of the nature of the experimental groups. Samples were examined using ApoTome Axio Imager Z2 (Zeiss).

Immunofluorescence and immunohistochemical analyses.

Immunostaining of TRα1 and TRβ1 was performed in rat and human biopsies. After antigen retrieval, OCT frozen kidney sections were blocked in 1% BSA and incubated overnight at 4°C with the following primary antibodies: rabbit anti-TRα1 and rabbit anti-TRβ1 (catalog PA1-211A and catalog PA1-213A, Invitrogen, 1:250), mouse anti-rat nestin (catalog 556309, BD Biosciences, 1:100), mouse anti-human nestin (catalog MAB5326, Millipore, 1:250), rabbit anti-c-Ret (catalog 3223, Cell Signaling, 1:50), rabbit anti-GFRα1 (catalog sc-10716, Santa Cruz Biotechnology, 1:30), mouse anti–Wilms tumor protein-1 (WT-1) (catalog sc-7385, Santa Cruz Biotechnology, 1:30), rabbit anti-Pax2 (catalog 71-6000, Invitrogen, 1:200), rabbit anti-Six2 (catalog 11562-1-AP Proteintech, 1:400), followed by appropriate Cy3- or FITC-conjugated secondary antibodies (Jackson ImmunoResearch Laboratories). Nuclei and renal structures were stained with DAPI (catalog D9542, MilliporeSigma, 1 μg/ml) and with DyLight 649–labeled Lens culinaris agglutinin (catalog DL1048, Vector Laboratories, 1:400), respectively. Negative controls were obtained by omitting the primary antibody on adjacent sections. Samples were examined using an inverted confocal laser microscope (Leica TCS SP8, Leica Biosystems).

For immunohistochemical analyses, formalin-fixed, 3-μm paraffin-embedded kidney sections were incubated with Peroxidazed 1 (Biocare Medical) to quench endogenous peroxidase, after antigen retrieval in a decloaking chamber with DIVA buffer. After blocking for 30 minutes with Rodent Block R (Biocare Medical), sections were incubated with rabbit anti-DIO3 (catalog NBP1-05767, Novus Biologicals, 1:2000), rabbit anti-TRα1 (catalog PA1-211A, Invitrogen, 1:300), rabbit anti-Pax2 (catalog 71-6000, Invitrogen, 1:300), rabbit anti-Six2 (catalog 11562-1-AP Proteintech, 1:200), rabbit anti-GDNF (catalog sc-328, 1:200), and rabbit anti-desmin (catalog ab15200, Abcam, 1:2000) antibodies, followed by Rabbit on Rodent HRP-Polymer (catalog RMR622G, Bio-Optica) for 20 minutes at room temperature. To study the glomerular podocyte density and individual podocyte volume, sections were incubated with mouse anti-WT-1 (catalog sc-7385, Santa Cruz Biotechnology, 1:30) and mouse anti-Glepp1 (catalog MABS455, Millipore, 1:100) antibodies followed by Mouse on Rat HRP-Polymer (catalog MRT621G, Bio-Optica) for 30 minutes at room temperature. Stainings were visualized using diaminobenzidine (Biocare Medical) substrate solutions. Slides were counterstained with Mayer’s hematoxylin (Bio Optica), mounted with Eukitt mounting medium and finally observed using light microscopy (ApoTome, Axio Imager Z2, Zeiss). Negative controls were obtained by omitting the primary antibody on adjacent sections. Stainings of TRα1 and fetal markers (Pax2, Six2, and GDNF), TRα1, and desmin as well as WT-1 and Glepp1 were performed in serial sections. Desmin staining was quantified by semiquantitative score from 0 to 3 (0, no staining or traces; 1, staining in <25% of the glomerular tuft; 2, staining affecting 26%–50%; 3, staining in >50%). The average number of podocytes per glomerulus and the glomerular volume were determined through morphometric analysis as previously described (70). For Glepp1-positive area measurement, 15 consecutive glomerular tuft areas were measured, and the percentage of each glomerular tuft that stained positive using Glepp1 immunoperoxidase was measured using ImageJ software (v 1.51, NIH). Globally sclerotic glomeruli were excluded from analysis. The mean Glepp1-positive (podocyte) volume per glomerulus was estimated by multiplying the mean glomerular volume by the mean percentage of Glepp1-positive area. The number of podocytes per glomerular tuft was measured using WT-1 immunoperoxidase staining, as described above. The mean individual podocyte volume was estimated by dividing the mean Glepp1-positive tuft volume by the mean podocyte number per tuft (71).

Cell culture and treatments.

Conditionally immortalized human podocytes (provided by P.W. Mathieson and M.A. Saleem, Children’s Renal Unit and Academic Renal Unit, University of Bristol, Southmead Hospital, Bristol, United Kingdom) were cultured and differentiated as described previously (72). Briefly, for cell propagation, podocytes were grown at 33°C in standard condition (5% CO2, 20% O2) in RPMI-1640 medium (catalog 21875034, Life Technologies Europe BV) supplemented with 10% FBS (catalog 10270106, Life Technologies), 1% insulin-transferrin-selenium (catalog 41400045, Life Technologies), and 1% Penicillin/Streptomycin (catalog 15140122, Life Technologies). Media were changed every 2 days. For cell differentiation, 80%-confluent cells were harvested using 0.05% (1′) Trypsin-EDTA (catalog 15400054, Thermo Fisher Scientific) and seeded at a density of 5 × 103 cells/cm2 in 6- or 12-well plates coated with 0.1 mg/ml rat-tail type I collagen (catalog 354236, Corning, Corning-Costar). Podocytes were maintained at 37°C for 14 days, and media were changed every 2 days. After differentiation, podocytes were starved in culture medium supplemented with 2% FBS overnight. Cells were then treated with 40 mM glucose (catalog G5146, MilliporeSigma) or 50 μM hydrogen peroxide (H2O2; catalog H1009, MilliporeSigma) for 3 days and with 40 mM glucose or 50 μM H2O2 in combination with 0.1 μM T3 (catalog T6397, MilliporeSigma) for the following 6 days. In other experiments, cells were treated with 40 mM glucose alone or in combination with 0.5 M DBD (catalog D288875, Toronto Research Chemicals) or in combination with 0.1 μM UO126 (catalog 9903S, Cell Signaling Technology) for 9 days. Glucose was dissolved in culture medium. H2O2 was diluted in culture medium. T3 was dissolved in NaOH, DBD in methanol, and UO126 in DMSO, and they were further diluted in culture medium. T3 concentration in the culture medium was 0.67 nM.

Protein extraction and Western blot analysis.

Adherent cells were collected and rinsed with cold 1× PBS (catalog AM9625, Invitrogen). Cells were then lysed in CelLytic M buffer (catalog C2978, MilliporeSigma) supplemented with protease (catalog 11836153001, MilliporeSigma) and phosphatase (catalog 04906837001, MilliporeSigma) inhibitors, following the manufacturer’s instructions. Kidney samples were homogenized, and cells were then lysed in CelLytic MT Cell Lysis Reagent (catalog C3228, MilliporeSigma) supplemented with protease and phosphatase inhibitors. Protein concentration was determined by DC protein assay (catalog 5000116, Bio-Rad Laboratories). Whole-cell lysates (30 μg) were separated by SDS polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis and transferred onto nitrocellulose blots (catalog GE10600001, MilliporeSigma). After blocking with 5% (w/v) BSA (catalog A7906, MilliporeSigma) in Tris buffered saline–0.1% (TBS-0.1%) Tween-20 (catalog P2287, MilliporeSigma), blots were incubated overnight at 4°C with the following primary antibodies: rabbit anti-TRα1 (catalog PA1-211A, Invitrogen, 1:500), rabbit anti-Pax2 (catalog 71-600, Invitrogen, 1:400), rabbit anti-Six2 (catalog 11562-1-AP, Proteintech, 1:500), mouse anti-GDNF (catalog sc-13147, Santa Cruz Biotechnology, 1:250), rabbit anti-Ret (catalog ANT-025, Alomone Labs, 1:500), rabbit anti-GFRα1 (catalog sc-10716, Santa Cruz Biotechnology, 1:200), rabbit anti-DIO3 (catalog NBP1-05767, Novus Biologicals, 1:2000), goat anti-α-actinin4 (catalog sc-49333, Santa Cruz Biotechnology, 1:200), mouse anti-α-SMA (catalog A2547, MilliporeSigma, 1:500), rabbit anti-pERK1/2 (catalog 9101, Cell Signaling, 1:1000), rabbit anti-ERK1/2 (catalog 4695, Cell Signaling, 1:1000), and mouse anti-tubulin (catalog T9026, MilliporeSigma, 1:2000). After washing in TBS-Tween, blots were incubated with anti-rabbit, anti-mouse, or anti-goat horseradish peroxidase–conjugated secondary antibodies (catalog A6154, catalog A9044, catalog AP180P, MilliporeSigma, 1:5000 to 1:20000) and developed with Super Signal West Pico chemiluminescent substrate (catalog 34580, Life Technologies) or incubated with anti-rabbit or anti-mouse infrared dye–conjugated secondary antibody (FE3680210, FE30926210, LiCor, 1:5000 to 1:20000) for 1 hour at room temperature. Images were acquired on Odyssey FC Imaging System (LiCor), and bands were quantified by densitometric analysis using the Image Studio Lite 5.0 software (LiCor). Tubulin or total protein load (Ponceau red staining) was used as sample loading control. In in vitro experiments results are expressed in arbitrary units.

Immunofluorescence analyses in vitro.

Podocytes were washed in PBS, fixed with 4% paraformaldehyde (catalog 157-8, Electron Microscopy Sciences) for 10 minutes, and permeabilized by 0.5% Triton X-100 (catalog 93418, MilliporeSigma) for 30 or 10 minutes at room temperature for TRα1 or DIO3 staining, respectively. After washing with PBS and blocking of nonspecific binding sites with 3% BSA (catalog A7906, MilliporeSigma) for 45 minutes at room temperature, cells were incubated with primary rabbit anti-TRα1 antibody (catalog PA1-211A, Invitrogen, 1:80) or rabbit anti-DIO3 (catalog NBP1-05767, Novus Biologicals, 1:80) diluted in 1% BSA, overnight at 4°C. After washing in PBS, cells were incubated with donkey anti-rabbit Cy3–conjugated secondary antibody (catalog 115-096-072, Jackson ImmunoResearch Laboratories, 1:50) for 1 hour at room temperature. For F-actin staining, podocytes were incubated with FITC-conjugated phalloidin (catalog A12389, Life Technologies, 1:150) for 45 minutes at room temperature. Nuclei were stained with DAPI (catalog D9542, MilliporeSigma, 1 μg/ml). Slides were mounted with Dako fluorescence mounting medium (catalog S3023, MilliporeSigma). Negative controls were obtained by omitting primary antibodies. Digital images were acquired using an inverted confocal laser microscope (Leica TCS SP8, Leica Biosystems) or Apotome Axio Imager Z2 (Zeiss). Images were analyzed with LAS X Industry Software and ImageJ. To quantify the number of cells with peripheral F-actin distribution, 15 random images for each sample were acquired and the percentage of cells with F-actin rearrangement with respect to total cells for each field was then evaluated in blind fashion.

Cell hypertrophy.

Podocyte hypertrophy was measured as a ratio between total protein content and cell number, as described previously (73). Data are expressed in arbitrary units.

Cell cycle analysis.

Cell cycle perturbations were analyzed at the end of treatments using the Allophycocyanin Bromodeoxyuridine (BrdU) Flow Kit (catalog 552598; BD Biosciences) following the manufacturer’s instructions. Briefly, cells were incubated with BrdU for 30 minutes in a humidified incubator and then harvested. After fixing and permeabilizing, cells were then treated with 300 μg/ml DNase for 1 hour at 37°C, and immunofluorescent staining with anti-BrdU antibody was performed. DNA was stained with 7-amino-actinomycin D. Finally, samples were analyzed by BD LSRFortessa X-20 (BD Biosciences) and acquired using the FACSDiVa software (BD Biosciences). At least 10,000 events per samples were analyzed using the FlowJo software.

SA-β-Gal activity assay.

SA-β-Gal activity was measured with a Senescence Detection Kit (catalog ab65351, Abcam), according to the manufacturer’s instructions. Briefly, cells were fixed for 15 minutes at room temperature and then stained with a solution containing X-Gal at 37°C overnight. During incubation, plates were put inside resealable bags. The next day, staining solution was removed and cells were overlaid with 70% glycerol. Images were captured using an inverted microscope (Primo Vert, Carl Zeiss) equipped with the AxioCam ERc 5s Rev. 2.0.

Statistics.

Statistical analysis was performed using Graph Pad Prism software. All data are expressed as mean ± SEM and in scatter dot plot diagrams. Comparisons were made using 2-tailed unpaired Student’s t test or 1-way ANOVA with Tukey’s multiple-comparisons post hoc test as appropriate. Correlations between T3 levels and hallmark of metabolic/renal disease were determined by linear regression. Statistical significance was set at P < 0.05. See figure legends for more details on statistical tests and n values used.

Study approval.

All procedures involving animals were performed with the approval of and in accordance with internal institutional guidelines of the Istituto di Ricerche Farmacologiche Mario Negri IRCCS, which are in compliance with national (D.L.n.26, March 4, 2014) and international laws and policies (directive 2010/63/EU on the protection of animals used for scientific purposes).

Renal tissues of patients (n = 3) with DN from the archives of the Unit of Nephrology, Azienda Azienda Socio Sanitaria Territoriale (ASST) Papa Giovanni XXIII (Bergamo, Italy) were studied. Specimens of uninvolved portions of kidney collected from tumor nephrectomy were used as controls. All experimental protocols involving human subjects and requiring informed consent were carried out in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki and good clinical practise guidelines and were approved by the ethical committee of the ASST Papa Giovanni XXIII.

Author contributions

V. Benedetti carried out in vitro experiments; collected, analyzed, and interpreted the data; prepared the figures; and prepared the manuscript. AML carried out in vitro experiments; performed Western blot and immunohistochemistry experiments on animals; collected, analyzed, and interpreted the data; and prepared the figures. ML performed immunohistochemistry experiments on animals and patients. V. Brizi carried out in vitro experiments, performed immunohistochemistry experiments in animals and cultured cells, and was responsible for the SA-β-Gal activity assay. DC performed animal studies. MT performed FACS analysis. RN performed immunohistochemistry experiments in patients and wrote the manuscript. AB edited and approved the final version of the manuscript. CZ supervised the in vivo studies and approved the final version of the manuscript. GR critically revised the manuscript and approved the final version of the manuscript. CX conceived and designed the experiments, analyzed and interpreted data, wrote the manuscript, and supervised the study. All authors reviewed the manuscript.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

The authors are grateful to Kerstin Mierke for the excellent editing work on the manuscript and Sara Buttò for technical contributions to the in vitro studies. Valentina Benedetti, Angelo Michele Lavecchia, and Rubina Novelli are recipients of fellowships from Fondazione Aiuti per la Ricerca sulle Malattie Rare, Bergamo, Italy. This research was partially funded by the European Foundation for the Study of Diabetes/Novo Nordisk and the Associazione per la Ricerca sul Diabete Italia.

Version 1. 09/19/2019

Electronic publication

Footnotes

Conflict of interest: The authors have declared that no conflict of interest exists.

Copyright: © 2019, American Society for Clinical Investigation.

Reference information: JCI Insight. 2019;4(18):e130249.https://doi.org/10.1172/jci.insight.130249.

Contributor Information

Valentina Benedetti, Email: valentina.benedetti@marionegri.it.

Angelo Michele Lavecchia, Email: angelomichele.lavecchia@marionegri.it.

Monica Locatelli, Email: monica.locatelli@marionegri.it.

Valerio Brizi, Email: valerio.brizi@marionegri.it.

Daniela Corna, Email: daniela.corna@marionegri.it.

Marta Todeschini, Email: marta.todeschini@marionegri.it.

Rubina Novelli, Email: rubina.novelli@marionegri.it.

Ariela Benigni, Email: ariela.benigni@marionegri.it.

Carlamaria Zoja, Email: carlamaria.zoja@marionegri.it.

Giuseppe Remuzzi, Email: giuseppe.remuzzi@marionegri.it.

Christodoulos Xinaris, Email: christodoulos.xinaris@marionegri.it.

References

- 1.Taylor E, Heyland A. Evolution of thyroid hormone signaling in animals: Non-genomic and genomic modes of action. Mol Cell Endocrinol. 2017;459:14–20. doi: 10.1016/j.mce.2017.05.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. doi: 10.1007/s00239-019-09908-1. Mourouzis I, Lavecchia AM, Xinaris C. Thyroid hormone signalling: from the dawn of life to the bedside [published online ahead of print August 27, 2019]. J Mol Evol . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Little AG, Seebacher F. The evolution of endothermy is explained by thyroid hormone-mediated responses to cold in early vertebrates. J Exp Biol. 2014;217(Pt 10):1642–1648. doi: 10.1242/jeb.088880. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Brent GA. Mechanisms of thyroid hormone action. J Clin Invest. 2012;122(9):3035–3043. doi: 10.1172/JCI60047. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Heyland A, Reitzel AM, Hodin J. Thyroid hormones determine developmental mode in sand dollars (Echinodermata: Echinoidea) Evol Dev. 2004;6(6):382–392. doi: 10.1111/j.1525-142X.2004.04047.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Laudet V. The origins and evolution of vertebrate metamorphosis. Curr Biol. 2011;21(18):R726–R737. doi: 10.1016/j.cub.2011.07.030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Forhead AJ, Fowden AL. Thyroid hormones in fetal growth and prepartum maturation. J Endocrinol. 2014;221(3):R87–R103. doi: 10.1530/JOE-14-0025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Mai W, et al. Thyroid hormone receptor alpha is a molecular switch of cardiac function between fetal and postnatal life. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2004;101(28):10332–10337. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0401843101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Horn S, Heuer H. Thyroid hormone action during brain development: more questions than answers. Mol Cell Endocrinol. 2010;315(1-2):19–26. doi: 10.1016/j.mce.2009.09.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Santini F, et al. Serum iodothyronines in the human fetus and the newborn: evidence for an important role of placenta in fetal thyroid hormone homeostasis. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 1999;84(2):493–498. doi: 10.1210/jcem.84.2.5439. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Wu J, Li X, Tao Y, Wang Y, Peng Y. Free Triiodothyronine Levels Are Associated with Diabetic Nephropathy in Euthyroid Patients with Type 2 Diabetes. Int J Endocrinol. 2015;2015:204893. doi: 10.1155/2015/204893. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Zou J, et al. Association between Thyroid Hormone Levels and Diabetic Kidney Disease in Euthyroid Patients with Type 2 Diabetes. Sci Rep. 2018;8(1):4728. doi: 10.1038/s41598-018-22904-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Wu P. Thyroid disorders and diabetes. It is common for a person to be affected by both thyroid disease and diabetes. Diabetes Self Manag. 2007;24(5):80–82. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Zoccali C, Mallamaci F, Tripepi G, Cutrupi S, Pizzini P. Low triiodothyronine and survival in end-stage renal disease. Kidney Int. 2006;70(3):523–528. doi: 10.1038/sj.ki.5001566. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Rhee CM. The interaction between thyroid and kidney disease: an overview of the evidence. Curr Opin Endocrinol Diabetes Obes. 2016;23(5):407–415. doi: 10.1097/MED.0000000000000275. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Lazzeri C, Sori A, Picariello C, Chiostri M, Gensini GF, Valente S. Nonthyroidal illness syndrome in ST-elevation myocardial infarction treated with mechanical revascularization. Int J Cardiol. 2012;158(1):103–104. doi: 10.1016/j.ijcard.2012.03.100. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Najafian B, Alpers CE, Fogo AB. Pathology of human diabetic nephropathy. Contrib Nephrol. 2011;170:36–47. doi: 10.1159/000324942. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Mukhi D, Nishad R, Menon RK, Pasupulati AK. Novel Actions of Growth Hormone in Podocytes: Implications for Diabetic Nephropathy. Front Med (Lausanne) 2017;4:102. doi: 10.3389/fmed.2017.00102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Lin JS, Susztak K. Podocytes: the Weakest Link in Diabetic Kidney Disease? Curr Diab Rep. 2016;16(5):45. doi: 10.1007/s11892-016-0735-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Herman-Edelstein M, Thomas MC, Thallas-Bonke V, Saleem M, Cooper ME, Kantharidis P. Dedifferentiation of immortalized human podocytes in response to transforming growth factor-β: a model for diabetic podocytopathy. Diabetes. 2011;60(6):1779–1788. doi: 10.2337/db10-1110. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Kriz W, Hähnel B, Rösener S, Elger M. Long-term treatment of rats with FGF-2 results in focal segmental glomerulosclerosis. Kidney Int. 1995;48(5):1435–1450. doi: 10.1038/ki.1995.433. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Lasagni L, Lazzeri E, Shankland SJ, Anders HJ, Romagnani P. Podocyte mitosis - a catastrophe. Curr Mol Med. 2013;13(1):13–23. doi: 10.2174/156652413804486250. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Kato H, et al. Wnt/β-catenin pathway in podocytes integrates cell adhesion, differentiation, and survival. J Biol Chem. 2011;286(29):26003–26015. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M111.223164. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Sweetwyne MT, Gruenwald A, Niranjan T, Nishinakamura R, Strobl LJ, Susztak K. Notch1 and Notch2 in Podocytes Play Differential Roles During Diabetic Nephropathy Development. Diabetes. 2015;64(12):4099–4111. doi: 10.2337/db15-0260. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Niranjan T, et al. The Notch pathway in podocytes plays a role in the development of glomerular disease. Nat Med. 2008;14(3):290–298. doi: 10.1038/nm1731. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Li Y, Kang YS, Dai C, Kiss LP, Wen X, Liu Y. Epithelial-to-mesenchymal transition is a potential pathway leading to podocyte dysfunction and proteinuria. Am J Pathol. 2008;172(2):299–308. doi: 10.2353/ajpath.2008.070057. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Herman-Edelstein M, Thomas MC, Thallas-Bonke V, Saleem M, Cooper ME, Kantharidis P. Dedifferentiation of immortalized human podocytes in response to transforming growth factor-β: a model for diabetic podocytopathy. Diabetes. 2011;60(6):1779–1788. doi: 10.2337/db10-1110. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Harder JL, et al. Organoid single cell profiling identifies a transcriptional signature of glomerular disease. JCI Insight. 2019;4(1):122697. doi: 10.1172/jci.insight.122697. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Dressler GR, Deutsch U, Chowdhury K, Nornes HO, Gruss P. Pax2, a new murine paired-box-containing gene and its expression in the developing excretory system. Development. 1990;109(4):787–795. doi: 10.1242/dev.109.4.787. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Kobayashi A, et al. Six2 defines and regulates a multipotent self-renewing nephron progenitor population throughout mammalian kidney development. Cell Stem Cell. 2008;3(2):169–181. doi: 10.1016/j.stem.2008.05.020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Qiao J, Sakurai H, Nigam SK. Branching morphogenesis independent of mesenchymal-epithelial contact in the developing kidney. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1999;96(13):7330–7335. doi: 10.1073/pnas.96.13.7330. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Loeffler I, Wolf G. Epithelial-to-Mesenchymal Transition in Diabetic Nephropathy: Fact or Fiction? Cells. 2015;4(4):631–652. doi: 10.3390/cells4040631. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Tsui CC, Shankland SJ, Pierchala BA. Glial cell line-derived neurotrophic factor and its receptor ret is a novel ligand-receptor complex critical for survival response during podocyte injury. J Am Soc Nephrol. 2006;17(6):1543–1552. doi: 10.1681/ASN.2005080835. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Miyauchi M, et al. Hypertrophy and loss of podocytes in diabetic nephropathy. Intern Med. 2009;48(18):1615–1620. doi: 10.2169/internalmedicine.48.2137. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Dai H, Liu Q, Liu B. Research Progress on Mechanism of Podocyte Depletion in Diabetic Nephropathy. J Diabetes Res. 2017;2017:2615286. doi: 10.1155/2017/2615286. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Bernal J, Morte B. Thyroid hormone receptor activity in the absence of ligand: physiological and developmental implications. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2013;1830(7):3893–3899. doi: 10.1016/j.bbagen.2012.04.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Burton DGA, Faragher RGA. Obesity and type-2 diabetes as inducers of premature cellular senescence and ageing. Biogerontology. 2018;19(6):447–459. doi: 10.1007/s10522-018-9763-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Verzola D, et al. Accelerated senescence in the kidneys of patients with type 2 diabetic nephropathy. Am J Physiol Renal Physiol. 2008;295(5):F1563–F1573. doi: 10.1152/ajprenal.90302.2008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Dimri GP, et al. A biomarker that identifies senescent human cells in culture and in aging skin in vivo. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1995;92(20):9363–9367. doi: 10.1073/pnas.92.20.9363. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Pantos C, Xinaris C, Mourouzis I, Malliopoulou V, Kardami E, Cokkinos DV. Thyroid hormone changes cardiomyocyte shape and geometry via ERK signaling pathway: potential therapeutic implications in reversing cardiac remodeling? Mol Cell Biochem. 2007;297(1-2):65–72. doi: 10.1007/s11010-006-9323-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Mourouzis I, Kostakou E, Galanopoulos G, Mantzouratou P, Pantos C. Inhibition of thyroid hormone receptor α1 impairs post-ischemic cardiac performance after myocardial infarction in mice. Mol Cell Biochem. 2013;379(1-2):97–105. doi: 10.1007/s11010-013-1631-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Ganesan K, Wadud K. Euthyroid Sick Syndrome. In: StatPearls. Treasure Island, Florida, USA: StatPearls Publishing; 2019. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Pantos C, Mourouzis I, Xinaris C, Papadopoulou-Daifoti Z, Cokkinos D. Thyroid hormone and “cardiac metamorphosis”: potential therapeutic implications. Pharmacol Ther. 2008;118(2):277–294. doi: 10.1016/j.pharmthera.2008.02.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Blanco-Molina A, González-Reyes JA, Torre-Cisneros J, López-Miranda J, Nicolás M, Pérez-Jiménez F. Effects of hypothyroidism on the ultrastructure of rat pancreatic acinar cells: a stereological analysis. Histol Histopathol. 1991;6(1):37–42. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Nam SM, et al. Hypothyroidism affects astrocyte and microglial morphology in type 2 diabetes. Neural Regen Res. 2013;8(26):2458–2467. doi: 10.3969/j.issn.1673-5374.2013.26.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Vadászová A, Zacharová G, Machácová K, Jirmanová I, Soukup T. Influence of thyroid status on the differentiation of slow and fast muscle phenotypes. Physiol Res. 2004;53 Suppl 1:S57–S61. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Charalambous M, Hernandez A. Genomic imprinting of the type 3 thyroid hormone deiodinase gene: regulation and developmental implications. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2013;1830(7):3946–3955. doi: 10.1016/j.bbagen.2012.03.015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Bouzaffour M, Rampon C, Ramaugé M, Courtin F, Vriz S. Implication of type 3 deiodinase induction in zebrafish fin regeneration. Gen Comp Endocrinol. 2010;168(1):88–94. doi: 10.1016/j.ygcen.2010.04.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Boelen A, et al. Induction of type 3 deiodinase activity in inflammatory cells of mice with chronic local inflammation. Endocrinology. 2005;146(12):5128–5134. doi: 10.1210/en.2005-0608. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Boelen A, et al. Type 3 deiodinase is highly expressed in infiltrating neutrophilic granulocytes in response to acute bacterial infection. Thyroid. 2008;18(10):1095–1103. doi: 10.1089/thy.2008.0090. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Dentice M, Antonini D, Salvatore D. Type 3 deiodinase and solid tumors: an intriguing pair. Expert Opin Ther Targets. 2013;17(11):1369–1379. doi: 10.1517/14728222.2013.833189. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Kester MH, et al. Large induction of type III deiodinase expression after partial hepatectomy in the regenerating mouse and rat liver. Endocrinology. 2009;150(1):540–545. doi: 10.1210/en.2008-0344. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Janssen R, Zuidwijk M, Muller A, Mulders J, Oudejans CB, Simonides WS. Cardiac expression of deiodinase type 3 (Dio3) following myocardial infarction is associated with the induction of a pluripotency microRNA signature from the Dlk1-Dio3 genomic region. Endocrinology. 2013;154(6):1973–1978. doi: 10.1210/en.2012-2017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Pantos C, et al. Thyroid hormone receptor alpha 1: a switch to cardiac cell “metamorphosis”? J Physiol Pharmacol. 2008;59(2):253–269. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]