Abstract

Background

Poor diet is a leading driver of obesity and morbidity. One possible contributor is increased consumption of foods from out of home establishments, which tend to be high in energy density and portion size. A number of out of home establishments voluntarily provide consumers with nutritional information through menu labelling. The aim of this study was to determine whether there are differences in the energy and nutritional content of menu items served by popular UK restaurants with versus without voluntary menu labelling.

Methods and findings

We identified the 100 most popular UK restaurant chains by sales and searched their websites for energy and nutritional information on items served in March-April 2018. We established whether or not restaurants provided voluntary menu labelling by telephoning head offices, visiting outlets and sourcing up-to-date copies of menus. We used linear regression to compare the energy content of menu items served by restaurants with versus without menu labelling, adjusting for clustering at the restaurant level. Of 100 restaurants, 42 provided some form of energy and nutritional information online. Of these, 13 (31%) voluntarily provided menu labelling. A total of 10,782 menu items were identified, of which total energy and nutritional information was available for 9605 (89%). Items from restaurants with menu labelling had 45% less fat (beta coefficient 0.55; 95% CI 0.32 to 0.96) and 60% less salt (beta coefficient 0.40; 95% CI 0.18 to 0.92). The data were cross-sectional, so the direction of causation could not be determined.

Conclusion

Menu labelling is associated with serving items with less fat and salt in popular UK chain restaurants. Mandatory menu labelling may encourage reformulation of items served by restaurants. This could lead to public health benefits.

Introduction

Globally, obesity has almost tripled since 1975, making it one of the most pressing public health challenges today[1]. Poor diet is a leading contributor to obesity, morbidity and mortality internationally[2]. Food from out of home sources, such as restaurants and fast food takeaways, tends to be high in energy, fat, sugar and salt[3–6]. Frequent consumption of food prepared out of the home is associated with poorer dietary quality and increased body weight[7–9].

One commonly proposed intervention to improve the nutritional quality of foods served by and selected from out of home food outlets is menu labelling. Typically menu labelling involves making nutritional information on foods served by out of home establishments available at the point of order or purchase[10]. Mandatory menu labelling in large chains was introduced in the US in May 2018 and has been implemented in some parts of Australia since 2012[11]. In the UK, voluntary menu labelling was included in the government’s Public Health Responsibility Deal in 2011[12]. Mandatory menu labelling was proposed in the second chapter of the government’s Childhood Obesity Plan in summer 2018[13], and a consultation to inform how such a policy might be implemented was launched in September 2018[14].

Menu labelling is typically conceived of as an information-giving intervention. In this framing, the assumption is that providing customers with clearer information on the energy and nutritional content of food served will allow them to make more informed, and hence ‘better’, choices. This conceptualisation of menu labelling is as a high agency intervention that relies on individuals using substantial personal resources to benefit from the intervention. Numerous systematic reviews, including a recent Cochrane review[15], have found only modest, poor quality, evidence of an effect of menu labelling on customer purchasing and consumption[15–25].

It is also possible that menu labelling acts as a low agency intervention by changing what outlets serve. In this framing, outlets are considered to perceive public information on excessively high energy (and other nutrient) content to equate to bad publicity and engage in reformulation, or development of new ‘healthier’ products, before implementing menu labelling. Reformulation is then expected to lead to changes in what consumers eat, without necessarily requiring that they use the information provided to inform changes in what they purchase.

Evidence on whether menu labelling affects the content of menu items served by restaurants is mixed. One 2018 meta-analysis by Zlatevska et al found that, on average, retailers reduced the energy content of items they serve by 15kcal after implementation of menu labelling[26]. However, substantial data included in this meta-analysis were collected in the context of known impending mandatory menu labelling, or implementation of such mandation. This may have substantially impacted the results found. No data from the UK were included. One 2017 systematic review by Bleich et al of five studies examining changes in the content of US restaurant menu items offered following implementation of local menu labelling regulations or in advance of national implementation found mixed effects. Two of the included studies found no statistically significant difference and three found a statistically significant difference in energy content[19].

We aimed to determine whether there were differences in the energy and nutritional content of menu items served by popular UK chain restaurants with versus without voluntary menu labelling. Our data was collected before government proposals for mandatory menu labelling had been published meaning they were uncontaminated by any retailer preparation for implementation of such an intervention.

Methods

We sourced nutritional information on menu items served by large UK chain restaurants from restaurant websites; and used this to compare information from chains that did and did not voluntarily provide menu labelling.

Restaurant inclusion criteria

Popular chain restaurants were defined as those listed in Technomic’s (a foodservice consultancy) “Top 100 U.K. Chain Restaurants Ranking” which were ranked by their total UK foodservice sales in 2013[27]. The list contains different types of restaurants including those with predominantly dine-in facilities and those with predominantly takeaway facilities. Henceforth, we refer to all included establishments as restaurants. Restaurants on this list were included in the analysis if they provided online nutritional information on food served in the restaurants.

Menu item inclusion criteria

Nutritional data were sourced from included restaurants’ websites in March-April 2018. Where a restaurant chain had different menus for use in different outlets (e.g. a number of pub chains provided ‘Core’, ‘Urban’ and ‘Rural’ menus) the most mainstream menu, used in the highest proportion of outlets, was used. Data were collected for all items on included menus as they appeared on websites. The only exception was when there was a negative value presented for energy or any nutrient. As negative values are implausible, these were regarded as errors and so were recorded as missing.

Where multiple menu items with identical item names featured on the same menu, each item was included because nutritional information occasionally varied–perhaps due to portion size variations. Beverages with options for different types of milk (e.g. cappuccino made with coconut milk and cappuccino made with semi skimmed milk) were entered individually so comparisons could be made between the different types. In two instances, platters composed of individual items served together were excluded as there was no nutritional information available for them, but the individual component items for which nutritional information was available were included.

There was some inconsistency in portion sizes of pizzas–particularly where these were intended for more than one person. We used energy and nutritional information on whole pizzas where these were intended for one person, and on three slices where it was clearly stated on menus that pizzas were intended to be shared.

Nutritional data

Data collected exactly as shown on included restaurants’ websites included: restaurant name, menu item name, and total energy and nutritional content of all included menu items. Alongside total energy, information on the following nutrients was extracted where available: total fat, total saturated fat, total carbohydrates, total sugar, total fibre, total protein and total salt.

Menu item categorisation

Menu item names were used to identify whether each item was labelled as shareable or not, for example John Barras’ “House Sharing Platter”, to separate items presented as being for sharing from items presented as being for an individual. Item descriptions were also used to categorise all items into one of 12 food categories, derived from similar work in the US[28] (Table 1).

Table 1. Food categories and descriptions.

| Food category | Description and examples |

|---|---|

| Appetisers & Sides | Items designed to supplement a main course e.g. chicken wings, sides of vegetables, rice, beans, fruit portion, coleslaw, potato salad, dumplings, nachos (irrespective of where they appear on the menu). |

| Baked Goods | Foods prepared with flour, baked, and served on their own, e.g. breads and rolls, muffins, doughnuts, croissants. |

| Beverages | All drinks including ice cream smoothies and milk shakes e.g. sugary and sweetened carbonated beverages, juice, milk, coffee, tea, smoothies, hot chocolate, beer, wine, milkshakes, floats, frappes. |

| Burgers | All items described as burgers e.g. hamburger, cheeseburger, chicken burger, veggie burgers. |

| Desserts | All sweets, including baked goods served as a dessert e.g. ice cream, cakes, cupcakes, brownies, cookies, pies, cheesecake, dessert bars, frozen yoghurt, sundaes. Excludes milkshakes. |

| Fried Potatoes | French fries (chips), sweet potato fries, fried potato skins e.g. potato wedges, hash browns, loaded fries which are fries with toppings. Excludes mashed or baked potatoes. |

| Mains | A main course meal and multiple component main course meals e.g. chicken nuggets, pasta mains, rice bowls, waffles, French toast, pancakes, porridge, quiches, sushi, mac and cheese. Excludes items described as or in the menu section indicating appetisers & sides |

| Pizza | Any dish consisting of a flat base of dough with a range of toppings, often featuring cheese and tomato sauce. Includes flatbread. |

| Salads | Any cold dish of various mixtures of raw and cooked vegetables and salad leaves, including side salads and salads served with additional items e.g. chicken or steak. Excludes potato and pasta salads. |

| Sandwiches | Any sandwich items in bread or tortilla e.g. wraps, breakfast sandwiches, hot dogs, bagels. Sandwiches served in buffets in quarter portions were considered Appetisers & Sides. |

| Soup | Any liquid dishes with meat, vegetables, legumes, e.g. soups and stews, gumbo and chowders. |

| Toppings & Ingredients | Toppings and ingredients in build-your-own products or products described as ‘Add Ons’ or ‘Extras’ e.g. sauces, butter and spreads, salad dressing, salad bar items, beverage toppings such as whipped cream. |

Menu labelling

Information on whether restaurants had voluntary menu labelling was obtained by telephoning the head offices of each chain restaurant in May 2018. This was verified either by visiting one outlet from each chain in person or, where this was not possible, sourcing an up-to-date image of the menu online.

Statistical analyses

The unit of analysis was the menu item, clustered within restaurants. Analyses were restricted to non-sharable items and those for which full data on total energy, fat, saturated fat, carbohydrate, sugar, protein and salt data was available. Fibre was excluded from the analyses due to 53% of data being missing. In some cases, stated macronutrient content was inconsistent with the stated energy content. The difference between stated energy content and expected energy content (calculated using stated fat, carbohydrate and protein) was determined and all menu items with more than +/-20% difference between expected and stated energy content were excluded from the analyses. We used +/-20% tolerance as this is the tolerance acceptable under current EU guidance on nutritional labelling on food packaging[29]. As nutritional variables were not normally distributed, non-parametric descriptive methods were used to summarise the data.

Separate linear regression models were used to compare log transformed energy and nutritional content of items from restaurants which did and did not voluntarily provide menu labelling. Variables were log transformed for analysis and regression coefficients back transformed for interpretation. Standard errors (and 95% confidence intervals) were adjusted to account for clustering at the restaurant level.

Results

Forty-two restaurants published nutritional information on their websites and were included in the analysis. Of the remaining 58, two no longer existed at the time of data collection, one had a non-functioning website and the remaining 55 did not publish nutritional information online.

Table 2 shows the 100 restaurants considered for inclusion, ranked by 2013 UK sales (from Technomic’s list), and indicating whether each voluntarily published nutritional information online or provided menu labelling. Of the 42 included restaurants with online nutritional information, 13 (31%) voluntarily provided menu labelling. Eleven of the 13 restaurants that provided voluntary menu labelling were in the top 50 by sales in 2013; 33 of the 52 functioning restaurants with functioning websites that voluntarily provided neither menu labelling or online nutritional information were in the bottom 50 by sales in 2013.

Table 2. Total UK sales and UK units in 2013, presence of online nutritional information, and voluntary menu labelling in 100 popular UK chain restaurants.

| Rank | Restaurant Name | 2013 UK Sales (£000)* | 2013 UK Units* | Online energy/nutritional information | Voluntary menu labelling |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | McDonald’s | £1,810,000 | 1,222 | Yes | Yes |

| 2 | Wetherspoon | 1,217,000 | 905 | Yes | Yes |

| 3 | Costa Coffee | 937,000 | 1,755 | Yes | Yes |

| 4 | Greggs | 787,000 | 1,671 | Yes | Yes |

| 5 | KFC | 684,500 | 850 | Yes | Yes |

| 6 | Domino’s Pizza | 622,500 | 771 | Yes | No |

| 7 | Starbucks | 606,000 | 764 | Yes | Yes |

| 8 | Pizza Hut | 532,000 | 685 | Yes | No |

| 9 | Subway | 531,000 | 1,590 | Yes | Yes |

| 10 | Nando’s | 455,000 | 290 | Yes | No |

| 11 | PizzaExpress | 411,000 | 421 | Yes | No |

| 12 | Burger King | 383,000 | 484 | Yes | Yes |

| 13 | Pret A Manger | 319,000 | 270 | Yes | Yes (food only) |

| 14 | Vintage Inns | 307,000 | 193 | No | No |

| 15 | Caffe Nero | 305,000 | 550 | Yes | Yes (food only) |

| 16 | Frankie & Benny’s | 207,000 | 209 | No | No |

| 17 | Harvester Salad & Grill | 196,000 | 210 | No | No |

| 18 | Wagamama | 179,000 | 105 | Yes | No |

| 19 | Sizzling Pubs | 174,000 | 220 | No | No |

| 20 | Ember Inns | 170,000 | 130 | No | No |

| 21 | Brewers Fayre | 163,000 | 145 | Yes | No |

| 22 | Hungry Horse | 161,000 | 199 | No | No |

| 23 | T.G.I Friday’s | 153,000 | 65 | No | No |

| 24 | Beefeater Grill | 146,000 | 140 | Yes | No |

| 25 | Prezzo | 136,000 | 194 | No | No |

| 26 | Chef & Brewer Pub Co. | 125,000 | 135 | Yes | No |

| 27 | Crown Carveries | 123,000 | 114 | No | No |

| 28 | Table Table | 116,000 | 105 | Yes | No |

| 29 | Taylor Walker | 112,000 | 113 | Yes | No |

| 30 | Toby Carvery | 112,000 | 154 | Yes | No |

| 31 | Revolution Vodka Bars | 109,000 | 67 | No | No |

| 32 | Zizzi | 109,000 | 130 | Yes | No |

| 33 | Carluccio’s | 104,000 | 76 | No | No |

| 34 | Jamie’s Italian | 102,000 | 37 | Yes | No |

| 35 | EAT | 99,000 | 112 | Yes | Yes (food only) |

| 36 | Nicholson’s | 99,000 | 77 | No | No |

| 37 | ASK | 95,000 | 110 | Yes | No |

| 38 | Fayre & Square | 95,000 | 157 | Yes | No |

| 39 | The Slug and Lettuce | 95,000 | 73 | No | No |

| 40 | Café Rouge | 87,000 | 127 | No | No |

| 41 | Papa John’s | 86,000 | 246 | Yes | No |

| 42 | Yate’s | 84,000 | 69 | Yes | No |

| 43 | Sayers the Better Bakers | 78,000 | 178 | No | No |

| 44 | YO! Sushi | 75,000 | 66 | Yes | Yes |

| 45 | All Bar One | 73,000 | 47 | Yes | No |

| 46 | Ben & Jerry’s | 72,000 | 265 | Yes | No |

| 47 | Bella Italia | 66,000 | 91 | No | No |

| 48 | Strada | 63,500 | 68 | No | No |

| 49 | Chicken Cottage | 61,000 | 129 | Yes | No |

| 50 | John Barras | 60,200 | 126 | Yes | No |

| 51 | Chiquito | 54,000 | 70 | No | No |

| 52 | Gaucho Grill | 53,200 | 16 | No | No |

| 53 | Patisserie Valerie | 53,000 | 108 | No | No |

| 54 | Old English Inns | 52,500 | 55 | Yes | No |

| 55 | O’Neill’s | 49,000 | 49 | No | No |

| 56 | Scream | 48,600 | 43 | No longer exists | NA |

| 57 | Gourmet Burger Kitchen | 46,200 | 60 | Yes | No |

| 58 | Davy’s | 45,100 | 28 | No | No |

| 59 | Flaming Grill Pub Co. | 42,000 | 87 | Yes | No |

| 60 | Loch Fyne | 42,000 | 42 | No | No |

| 61 | Browns Bar & Brasserie | 38,500 | 27 | No | No |

| 62 | Giraffe | 38,200 | 50 | No | No |

| 63 | Brasserie Blanc | 38,000 | 19 | No | No |

| 64 | La Tasca | 37,000 | 38 | No | No |

| 65 | Cote Restaurants | 36,700 | 46 | No | No |

| 66 | Miller & Carter | 35,000 | 29 | No | No |

| 67 | Wildwood Restaurants | 33,100 | 18 | No | No |

| 68 | Wacky Warehouse | 32,200 | 75 | No | No |

| 69 | Hollywood Bowl | 32,000 | 46 | No | No |

| 70 | Favourite Fried Chicken | 31,800 | 85 | No | No |

| 71 | Pitcher & Piano | 31,700 | 18 | No | No |

| 72 | Byron | 31,000 | 34 | No | No |

| 73 | Meet & Eat Pub & Grill | 31,000 | 38 | No | No |

| 74 | Piccolino Ristorante e Bar | 30,500 | 21 | No | No |

| 75 | PAUL | 30,400 | 31 | Yes | No |

| 76 | Le Pain Quotidien | 30,000 | 24 | No | No |

| 77 | Las Iguanas | 29,800 | 34 | No | No |

| 78 | Little Chef | 29,500 | 78 | No | No |

| 79 | Loungers | 29,500 | 38 | No longer exists | NA |

| 80 | Cosmo | 28,100 | 15 | No | No |

| 81 | Handmade Burger Co. | 27,300 | 18 | No | No |

| 82 | San Carlo | 27,000 | 13 | No | No |

| 83 | Jamies Wine Bars | 26,000 | 10 | No | No |

| 84 | Wimpy | 26,000 | 110 | Yes | Yes |

| 85 | Ed’s Easy Diner | 25,700 | 23 | No | No |

| 86 | Pizza GoGo | 25,700 | 95 | No | No |

| 87 | Krispy Kreme | 25,400 | 52 | Yes | No |

| 88 | Bill’s | 25,200 | 31 | Yes | No |

| 89 | Busaba Eathai | 25,200 | 10 | No | No |

| 90 | Pizza Kitchen & Bar | 25,200 | 24 | Website invalid | No |

| 91 | Gusto | 24,800 | 10 | No | No |

| 92 | Muffin Break | 23,300 | 51 | No | No |

| 93 | Walkabout | 23,200 | 27 | Yes | No |

| 94 | Baguette Express | 23,000 | 70 | No | No |

| 95 | Chimichanga | 22,800 | 37 | No | No |

| 96 | AMT Coffee Bars | 22,600 | 60 | No | No |

| 97 | Dixy Chicken | 22,300 | 82 | No | No |

| 98 | Itsu | 21,700 | 43 | Yes | Yes |

| 99 | The Restaurant Bar & Grill | 21,500 | 11 | No | No |

| 100 | Aagrah | 21,400 | 16 | No | No |

Green: restaurants with nutritional information available online and voluntary menu labelling

Orange: restaurants with nutritional information available online, but no voluntary menu labelling

Red: restaurants with no nutritional information available online, and no voluntary menu labelling

Unshaded: restaurant no longer existed at the time of data collection

* Based on Technomic’s 2013 list

Of 10,782 menu items identified across the 42 included restaurants, a total of 9,984 (93%) menu items with no missing data for energy, fat, saturated fat, carbohydrates, sugar, protein and salt were included in the analysis (see Table 3). Of these, 379 (4%) menu items were excluded for having more than +/-20% uncertainty of measurement. Of the remaining 9,605 menu items 6,811 (71%) were food items, 1,929 (20%) were beverages, and 865 (9%) were toppings or ingredients. Table 4 summarises the distribution of total content of energy and each nutrient per menu item across all included items. Daily Reference Intakes (DRIs) for each nutrient are also provided[30]. Across all menu categories, at least 75% of individual menu items were below DRIs for all nutrients. However, the maximum values for energy and each nutrient exceeded DRIs in all cases meaning that individual items were exceeding the entire daily recommended intake. The maximum values show that some individual items contained more than two times the daily recommended amount for energy, fat, saturated fat, sugar, protein or salt. For energy, the maximum value was 5961 meaning an individual menu item contained almost three times the daily recommended amount.

Table 3. Summary of non-missing data on energy and nutritional content of 10,782 menu items.

| Energy/nutrient per serving | Complete Data, n(%) |

|---|---|

| Kcal | 10,653 (99) |

| Fat (g) | 10,535 (98) |

| Saturated Fat (g) | 10,533 (98) |

| Carbohydrates (g) | 10,333 (96) |

| Sugar (g) | 10,538 (98) |

| Fibre (g) | 5,097 (47) |

| Protein (g) | 10,323 (96) |

| Salt (g) | 10,447 (97) |

Table 4. Distribution of energy and nutrients in 9605 menu items from 42 popular UK chain restaurants.

| Energy/nutrient | Median (25th– 75th centile) | Minimum—maximum | Daily reference intake |

|---|---|---|---|

| Energy (kcal) | 327 (150–581) | 1–5961 | 2000 |

| Fat (g) | 13.8 (5.2–25.5) | 0–412 | <70g |

| Saturated Fat (g) | 4.8 (1.5–9.8) | 0–162.2 | <20g |

| Carbohydrates (g) | 37.6 (15–63) | 0–424.7 | At least 260g |

| Sugar (g) | 9.8 (3.6–18.5) | 0–228.3 | 90g |

| Protein (g) | 9.7 (3.5–26.7) | 0–212.6 | 50g |

| Salt (g) | 0.9 (0.21–2.7) | 0–29 | 6g |

The distribution of energy and nutrients in menu items, stratified by food category, is shown in S1 Table. In four categories (burgers, desserts, mains, and sandwiches) the maximum energy and nutritional content of items exceeded DRIs for five or six of the six variables considered.

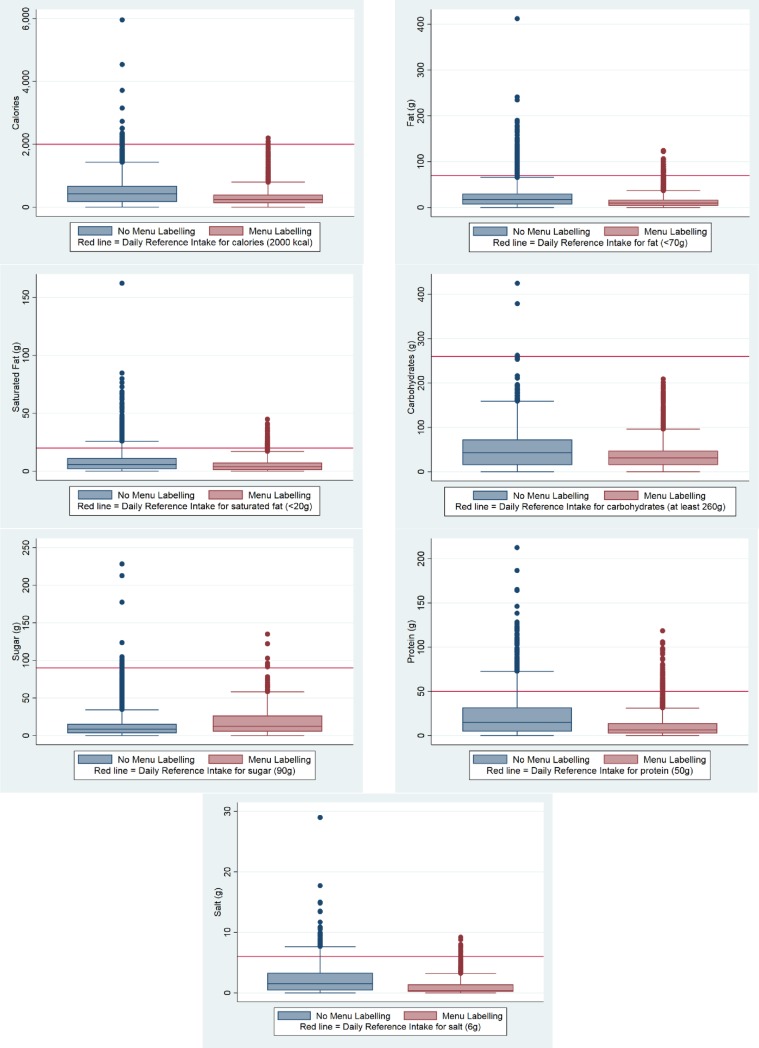

Fig 1 shows the distribution of energy and nutrients in individual menu items stratified by whether restaurants provided voluntary menu labelling or not. Medians for all variables, except sugar, were lower in items from restaurants with, compared to without, menu labelling. However, in all cases, except total carbohydrates, maximum values for items in both groups exceeded relevant DRIs.

Fig 1. Distribution of energy and nutrients in 9605 menu items from 42 popular UK chain restaurants, stratified by whether or not restaurants provided voluntary menu labelling.

Table 5 shows the exponentiated results of the separate linear regression models comparing log transformed energy and nutrients of menu items served by restaurants with and without voluntary menu labelling. The exponentiated coefficients are ratios of the geometric mean of each variable in restaurants with versus without menu labelling. A value less than 1 indicates the variable is lower in restaurants with menu labelling compared to those without. 95% confidence intervals that do not cross 1 indicate statistical significance. After adjusting for clustering at the restaurant level, fat and salt were significantly lower in items from restaurants with, versus without, voluntary menu labelling. Items from restaurants with menu labelling had 45% less fat and 60% less salt than those from restaurants without menu labelling. Although items from restaurants with menu labelling had 32% less energy, 35% less saturated fat, 17% less carbohydrates, 52% more sugar and 48% less protein than those from restaurants without menu labelling, the results were not statistically significant.

Table 5. Summary of linear regression models comparing log transformed energy and nutritional content of 9605 menu items from 42 popular UK restaurants with and without voluntary menu labelling.

| Energy/nutrient | Exponentiated regression coefficient* | 95% CI (adjusted for clustering at restaurant level) |

|---|---|---|

| Energy (kcal) | 0.68 | 0.43 to 1.07 |

| Fat (g) | 0.55 | 0.32 to 0.96 |

| Saturated Fat (g) | 0.65 | 0.41 to 1.01 |

| Carbohydrates (g) | 0.83 | 0.54 to 1.28 |

| Sugar (g) | 1.52 | 0.91 to 2.54 |

| Protein (g) | 0.52 | 0.26 to 1.03 |

| Salt (g) | 0.40 | 0.18 to 0.92 |

*The ratio of the geometric mean of each variable in restaurants with versus without menu labelling.

Similar data to Table 5 stratified by food category is shown in S2 Table. The results are mixed and most differences in energy and nutrient content are not statistically significant. Some notable exceptions were that Baked Goods items from restaurants with menu labelling had, on average, 18% more energy, 74% more fat, 100% more saturated fat, 300% more sugar but 25% more protein and 43% more salt than items from restaurants without menu labelling; pizza items had 39% less sugar and 64% less salt; sandwich items had 39% less sugar, 23% less protein, and 27% less salt; and toppings & ingredients had 47% less fat, 44% less saturated fat, and 59% less protein than items from restaurants without menu labelling. No statistically significant differences was found in the energy or any nutrient contents of Appetisers & Sides, Beverages, Burgers, Desserts, Fried Potatoes, Mains, Salads and Soup items between restaurants with and without menu labelling.

Discussion

This is the first assessment of differences in energy and nutritional content of menu items served by UK restaurants that do and do not provide voluntary menu labelling in a context where mandatory labelling had not been proposed or implemented. Two months before the UK government announced proposals for mandatory menu labelling, menu items served by popular UK restaurants with voluntary menu labelling had 45% less fat and 60% less salt than those from restaurants without menu labelling.

This is the first comprehensive survey of the energy and nutritional content of items served by popular UK chain restaurants, and the prevalence of providing information on these variables online and in-restaurant. Of 100 restaurant chains considered, 42 provided energy and nutritional information online, of which 13 provided any of this information on the restaurant menu. There were examples of single items that contained more than the DRI for energy and all nutrients considered from both restaurants that did and did not provide voluntary menu labelling.

Strengths and weaknesses of methods

We used a cross-sectional design and reverse causation cannot be excluded. It is possible that restaurants serving menu items with less fat and salt are more likely to voluntarily menu label. However, in the absence of mandatory menu labelling, this would also be limitation of a longitudinal design.

We considered all chain restaurants in the top 100 by UK sales in 2013. This increases the generalisability of the findings to the UK chain sector in particular. However, the findings may be less generalizable to the independent sector, and to settings beyond the UK. We were unable to source more recent data on the top UK chain restaurants by sales. It is likely the chains on this list have changed somewhat since 2013.

Without laboratory analysis, we cannot confirm the validity or reliability of the information on energy or nutritional content used. Whilst some macronutrient values were inconsistent with stated total energy content, we do not know which values were erroneous–it could be that the macronutrient values were wrong, or that the total energy content was wrong. As such, we excluded items where stated energy content was +/-20% difference from energy calculated from macronutrients. The other values removed were negative values which are clearly implausible. Laboratory analysis was not feasible within the resources available to us. Nor did we have resources for duplicate transcription. Previous research indicates that in-restaurant data on energy content tends to be accurate overall[31].

Our statistical analysis was conducted at the menu item level. Different restaurants report meals and their component parts differently meaning that items are not necessarily comparable. Repeating our analyses stratified by food category overcame this limitation to some extent.

Our data describe menu items available for purchase. We do not know the relative frequency with which items are purchased and cannot determine the potential impact of menu labelling on purchasing or consumption.

Interpretation of findings

We found lower fat and salt in items served by chains with, versus without, voluntary menu labelling, but no effect on energy content. Previous research comparing food content has largely focused on changes in energy content associated with menu labelling[11,18,26]. The majority of results, including from a meta-analysis, find that menu labelling is associated with healthful changes in the energy content of menu items. However, most previous studies which report an effect on energy content were reported in contexts where nation-wide mandatory menu labelling was implemented. Given we found no difference in energy content, such nation-wide mandatory labelling may be required to achieve significant change in energy content.

This study contributes to the evidence base in two key ways. As far as we understand, it is the first study to present differences in energy content as well as in fat, saturated fat, carbohydrates, sugar, protein and salt; and it is the first major UK study of differences in the energy and nutritional content of menu items served in restaurants with and without menu labelling. We found that the difference in energy and nutrient content between restaurants that did and did not have menu labelling were not consistent. Most previous studies in this area have focused on energy. Our findings that any impacts on energy are not generalisable to other nutrients indicate that future research should include a wider range of nutritional information than just energy.

It is difficult to determine the direction of any causation using cross-sectional data. However, this may not be an either/or situation. It is possible that menu labelling encourages change in the content of food served and simultaneously that those chains with ‘healthier’ offerings are more likely to label. Further research is required to determine why some restaurants opt for voluntary menu labelling. In the UK the Public Health Responsibility Deal[32] encouraged some restaurants to voluntarily menu label. It is notable that 11 of the 13 restaurants that provided voluntary menu labelling were in the top 50 by sales. Larger chains may come under more scrutiny from governments, the media, campaign groups and the public to provide both menu labelling and ‘healthier’ options.

We found inconsistent magnitudes of difference in energy and nutrients between chains that did and did not provide voluntary menu labelling. This suggests that menu labelling is not simply associated with reduced portion size (where energy and other nutrients would be reduced in comparable proportions). Rather, the formulation of items served by the two groups of restaurants appears to be different. Further work could explore these differences in more depth.

While restaurant characteristics may well be one factor influencing whether or not they choose to menu label, it would be difficult and potentially misleading to develop a comprehensive categorisation of these as many restaurants have multiple characteristics. For example, many restaurants provide both dine-in and takeaway facilities. Furthermore, dine-in experiences, for example, may differ between restaurants. The growth of online restaurant ordering platforms such as Deliveroo compound this problem.

We found individual items that substantially exceeded DRIs for energy and all nutrients studied. The highest energy content of a single menu item was almost three times the recommended daily energy intake for a UK adult. Similarly, individual items provided almost six times the DRI for fat, more than eight times the DRI for saturated fat, more than three times the DRI for sugar, and almost five times the DRI for salt. This indicates some exceedingly large portion sizes and nutritionally imbalanced items. Given that portion size is associated with consumption[33], this is likely to contribution to over-consumption at individual sittings. More than one quarter of UK adults eat meals out at least once a week[34], indicating that these large, nutritionally imbalanced portions are likely to contribute to poor dietary intake at a population level[35]. Recent efforts to encourage reduction of portion size across both the supermarket and out of home sectors in England may help address this in due course[36].

Implications for policy, practice and research

Our findings indicate that mandatory menu labelling may lead to reformulation of existing items, or systematic changes in the content of newly introduced dishes. Alongside modest changes in purchasing and consumption[15], mandatory menu labelling has the potential to effect change in the nutritional content of food eaten from out of home sources. Implementation of mandatory menu labelling is required before more robust longitudinal evidence of effect can be generated.

Alongside menu labelling, other strategies are likely to be required to improve the energy and nutritional content of food sourced out of home. This may include strategies to address availability, affordability and marketing; as well as those to provide individuals with the skills and information required to make ‘healthier’ choices. Further research is required to understand the most effective, efficient and equitable combination of strategies.

Conclusion

Popular UK restaurant chains which provided voluntary menu labelling served items with less fat and salt than those without such labelling. Mandatory menu labelling has the potential to improve the nutritional profile of food served out of home. Some menu items from restaurants both with and without menu labelling had very large portion sizes, and were nutritional imbalanced. Further work is required to establish the most effective, efficient and equitable strategies to improve the nutritional profile of food served out of home.

Supporting information

(DOCX)

(DOCX)

(XLSX)

Acknowledgments

We would like to acknowledge helpful advice of the New York City State Department of Health and Mental Hygiene.

Data Availability

All relevant data are within the manuscript and its Supporting Information files.

Funding Statement

DT is supported by the NIHR School for Public Health Research (SPHR). The views expressed are those of the author(s) and not necessarily those of the NHS, the NIHR or the Department of Health and Social Care. JA is supported by the Centre for Diet and Activity Research (CEDAR), a UKCRC Public Health Research Centre of Excellence. Funding from the British Heart Foundation, Cancer Research UK, Economic and Social Research Council, Medical Research Council, the National Institute for Health Research, and the Wellcome Trust, under the auspices of the UK Clinical Research Collaboration, is gratefully acknowledged (grant number MR/K023187/1). The funders had no role in study design, data collection and analysis, decision to publish, or preparation of the manuscript.

References

- 1.World Health Organization. Obesity and overweight [Internet]. 2017 [cited 2018 Jul 7]. Available from: http://www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/obesity-and-overweight

- 2.Stanaway JD, Afshin A, Gakidou E, Lim SS, Abate D, Abate KH, et al. Global, regional, and national comparative risk assessment of 84 behavioural, environmental and occupational, and metabolic risks or clusters of risks for 195 countries and territories, 1990–2017: a systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2017. Lancet [Internet]. 2018. November [cited 2018 Dec 3];392(10159):1923–94. Available from: https://linkinghub.elsevier.com/retrieve/pii/S0140673618322256 10.1016/S0140-6736(18)32225-6 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Jaworowska A, Blackham T, Davies IG, Stevenson L. Nutritional challenges and health implications of takeaway and fast food. Nutr Rev [Internet]. 2013. [cited 2018 Dec 3]; Available from: https://academic.oup.com/nutritionreviews/article-abstract/71/5/310/2460221 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Deierlein AL, Peat K, Claudio L. Comparison of the nutrient content of children’s menu items at US restaurant chains, 2010–2014. Nutr J [Internet]. 2015. [cited 2018 Nov 16];14(80). Available from: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC4536860/pdf/12937_2015_Article_66.pdf [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Hobin E, White C, Li Y, Chiu M, Fodor O’brien M, Hammond D. Short Communication Nutritional quality of food items on fast-food “kids” menus’: comparisons across countries and companies. Public Health Nutr [Internet]. 2013. [cited 2018 Dec 3];17(10):2263–9. Available from: https://www.cambridge.org/core/services/aop-cambridge-core/content/view/0FB4348EA7B9827C6B4F0AF18ACE4219/S1368980013002498a.pdf/nutritional_quality_of_food_items_on_fastfood_kids_menus_comparisons_across_countries_and_companies.pdf 10.1017/S1368980013002498 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Wu HW, Sturm R. What’s on the menu? A review of the energy and nutritional content of US chain restaurant menus. Public Health Nutr [Internet]. 2012. [cited 2018 Dec 3];16(1):87–96. Available from: https://www.cambridge.org/core/services/aop-cambridge-core/content/view/B2B9C89AB21F4FDFD867767F0AC5D7CC/S136898001200122Xa.pdf/whats_on_the_menu_a_review_of_the_energy_and_nutritional_content_of_us_chain_restaurant_menus.pdf 10.1017/S136898001200122X [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Lachat C, Nago E, Verstraeten R, Roberfroid D, Van Camp J, Kolsteren P. Eating out of home and its association with dietary intake: A systematic review of the evidence. Obes Rev. 2012;13(4):329–46. 10.1111/j.1467-789X.2011.00953.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Nago ES, Lachat CK, M Dossa RA, Kolsteren PW. Association of Out-of-Home Eating with Anthropometric Changes: A Systematic Review of Prospective Studies. Crit Rev Food Sci Nutr [Internet]. 2014. [cited 2018 Dec 3];54(9):1103–16. Available from: http://www.tandfonline.com/action/journalInformation?journalCode=bfsn20 10.1080/10408398.2011.627095 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Bezerra IN, Curioni C, Sichieri R. Association between eating out of home and body weight. Nutr Rev [Internet]. 2012. [cited 2018 Dec 3]; Available from: https://academic.oup.com/nutritionreviews/article-abstract/70/2/65/1895841 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Thomas E. Food for thought: Obstacles to menu labelling in restaurants and cafeterias. Public Health Nutr. 2015;19(12):2185–9. 10.1017/S1368980015002256 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Wellard-Cole L, Goldsbury D, Havill M, Hughes C, Watson WL, Dunford EK, et al. Monitoring the changes to the nutrient composition of fast foods following the introduction of menu labelling in New South Wales, Australia: an observational study. Public Health Nutr [Internet]. 2017. [cited 2018 Nov 16];21(6):1194–9. Available from: https://www.cambridge.org/core/services/aop-cambridge-core/content/view/D4205EA998E45B0FC3303065E186035E/S1368980017003706a.pdf/monitoring_the_changes_to_the_nutrient_composition_of_fast_foods_following_the_introduction_of_menu_labelling_in_new_south_wale 10.1017/S1368980017003706 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Department of Health. [ARCHIVED CONTENT] Pledges | Public Health Responsibility Deal [Internet]. HM Government. 2012 [cited 2018 Nov 16]. Available from: https://webarchive.nationalarchives.gov.uk/20180201175857/https://responsibilitydeal.dh.gov.uk/pledges/

- 13.Department of Health and Social Care: Global Public Health Directorate: Obesity F and N. Childhood obesity: a plan for action Chapter 2 [Internet]. London; 2018. Available from: https://assets.publishing.service.gov.uk/government

- 14.Global and Public Health Group Obesity Branch, Childhood Obesity Team. Consultation on mandating calorie labelling in the out-of-home sector [Internet]. 2018 [cited 2018 Nov 16]. Available from: www.nationalarchives.gov.uk/doc/open-government-licence/

- 15.Crockett RARA, King SESESE, Marteau TMTMTM, Prevost ATT, Bignardi G, Roberts NWNW, et al. Nutritional labelling for healthier food or non-alcoholic drink purchasing and consumption. Cochrane Database Syst Rev [Internet]. 2018. February 27 [cited 2018 Jul 6];2018(2). Available from: http://doi.wiley.com/10.1002/14651858.CD009315.pub2 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Cawley J. Does Anything Work to Reduce Obesity? (Yes, Modestly). J Health Polit Policy Law [Internet]. 2016;41(3):463–72. Available from: http://jhppl.dukejournals.org/lookup/doi/10.1215/03616878-3524020 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Cawley J, Wen K. Policies to prevent obesity and promote healthier diets: A critical selective review. Clin Chem. 2018;64(1):163–72. 10.1373/clinchem.2017.278325 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Bleich SNSN, Economos CDCD, Spiker MLML, Vercammen KAKA, VanEpps EMEM, Block JPJP, et al. A Systematic Review of Calorie Labeling and Modified Calorie Labeling Interventions: Impact on Consumer and Restaurant Behavior. Obesity [Internet]. 2017. December [cited 2018 Jul 6];25(12):2018–44. Available from: http://doi.wiley.com/10.1002/oby.21940 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Littlewood JA, Lourenço S, Iversen CL, Hansen GL. Menu labelling is effective in reducing energy ordered and consumed: A systematic review and meta-analysis of recent studies. Public Health Nutr. 2016;19(12):2106–21. 10.1017/S1368980015003468 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Long MW, Tobias DK, Cradock AL, Batchelder H, Gortmaker SL. Systematic review and meta-analysis of the impact of restaurant menu calorie labeling. Am J Public Health. 2015;105(5):e11–24. 10.2105/AJPH.2015.302570 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Cantu-Jungles TM, McCormack LA, Slaven JE, Slebodnik M, Eicher-Miller HA. A meta-analysis to determine the impact of restaurant menu labeling on calories and nutrients (Ordered or consumed) in U.S. adults. Nutrients. 2017;9(10). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Swartz JJ, Braxton D, Viera AJ. Calorie menu labeling on quick-service restaurant menus: An updated systematic review of the literature. Int J Behav Nutr Phys Act. 2011;8:1–8. 10.1186/1479-5868-8-1 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Harnack LJ, French SA. Effect of point-of-purchase calorie labeling on restaurant and cafeteria food choices: A review of the literature. Int J Behav Nutr Phys Act. 2008;5:3–8. 10.1186/1479-5868-5-3 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Sinclair SESE, Cooper M, Mansfield EDED. The influence of menu labeling on calories selected or consumed: a systematic review and meta-analysis. J Acad Nutr Diet. 2014;114(9). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Kiszko KM, Martinez OD, Abrams C, Elbel B. The influence of calorie labelling on food orders and consumption: A review of the literature. J Community Health. 2014;39(6):1248–69. 10.1007/s10900-014-9876-0 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Zlatevska N, Neumann N, Dubelaar C. Mandatory Calorie Disclosure: A Comprehensive Analysis of Its Effect on Consumers and Retailers. J Retail [Internet]. 2018. March [cited 2018 Dec 3];94(1):89–101. Available from: https://linkinghub.elsevier.com/retrieve/pii/S0022435917300775 [Google Scholar]

- 27.Technomic Top 100 U.K. Chain Restaurant Report [Internet]. Technomic. 2014 [cited 2018 Dec 3]. Available from: https://www.technomic.com/available-studies/industry-reports

- 28.MenuStat Methods Data Source [Internet]. MenuStat. 2018 [cited 2018 Jul 7]. Available from: http://menustat.org/Content/assets/pdfFile/MenuStat Data Completeness Documentation.pdf

- 29.GUIDANCE DOCUMENT FOR COMPETENT AUTHORITIES FOR THE CONTROL OF COMPLIANCE WITH EU LEGISLATION. European Commission. 2012.

- 30.British Nutrition Foundation. Nutrition Requirements [Internet]. 2016 [cited 2018 Dec 3]. Available from: https://www.nutrition.org.uk/attachments/article/234/Nutrition Requirements_Revised Oct 2016.pdf

- 31.Urban LE, Mayer J, McCrory MA, Dallal GE, Krupa Das S, Saltzman E, et al. Accuracy of Stated Energy Contents of Restaurant Foods) gathered restaurant information; HHS Public Access. JAMA [Internet]. 2011. [cited 2018 Dec 3];306(3):287–93. Available from: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC4363942/pdf/nihms585948.pdf 10.1001/jama.2011.993 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Knai C, Petticrew M, Durand MA, Eastmure E, James L, Mehrotra A, et al. Has a public-private partnership resulted in action on healthier diets in England? An analysis of the Public Health Responsibility Deal food pledges. Food Policy [Internet]. 2015;54(March 2011):1–10. Available from: 10.1016/j.foodpol.2015.04.002 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Hollands G, Shemilt I, Marteau T, Lewis H, Wei Y, Higgins J, et al. Portion, package or tableware size for changing selection and consumption of food, alcohol and tobacco (Review). Cochrane Database Syst Rev | Cochrane Collab [Internet]. 2015. [cited 2018 Dec 3]; Available from: http://www.thecochranelibrary.com [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Adams J, Goffe L, Brown T, Lake AA, Summerbell C, White M, et al. Frequency and socio-demographic correlates of eating meals out and take-away meals at home: Cross-sectional analysis of the UK national diet and nutrition survey, waves 1–4 (2008–12). Int J Behav Nutr Phys Act [Internet]. 2015;12(1):1–9. Available from: ??? [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Goffe L, Rushton S, White M, Adamson A, Adams J. Relationship between mean daily energy intake and frequency of consumption of out-of-home meals in the UK National Diet and Nutrition Survey. Int J Behav Nutr Phys Act [Internet]. 2017. [cited 2018 Dec 3];14(131). Available from: https://ijbnpa.biomedcentral.com/track/pdf/10.1186/s12966-017-0589-5 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Tedstone Alison. Why we are working to reduce calorie intake—Public health matters [Internet]. Public Health England. 2018. [cited 2018 Jul 7]. Available from: https://publichealthmatters.blog.gov.uk/2018/03/06/why-we-are-working-to-reduce-calorie-intake/ [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

(DOCX)

(DOCX)

(XLSX)

Data Availability Statement

All relevant data are within the manuscript and its Supporting Information files.