Abstract

Background: This study aims to analyze the public-private partnership (PPP) policy in primary health care (PHC), focusing on the experience of the East Azerbaijan Province (EAP) of Iran. Methods: This research is a qualitative study. Data were gathered using interviews with stakeholders and document analysis and analyzed through content analysis. Results: Participants considered political and economic support as the most important underlying factors. Improving system efficiency was the main goal of this policy. Most stakeholders were supporters of the plan, and there was no major opponent. Implementing the health evolution plan (HEP) was an opportunity to design this policy. Participants considered the lack of provision of infrastructure as the main weakness, changing the role of the public sector as the main strength, and promoting social justice as the main achievement of policy. The results of the quantitative data review showed that following the implementation of this policy, health indicators have been improved. Conclusions: Based on the results of this study, the PPP model in EAP is a new and successful experience in PHC in Iran. Supporting and developing this policy may improve the quality and quantity of providing care.

Keywords: public-private partnership, primary health care, policy analysis

Background

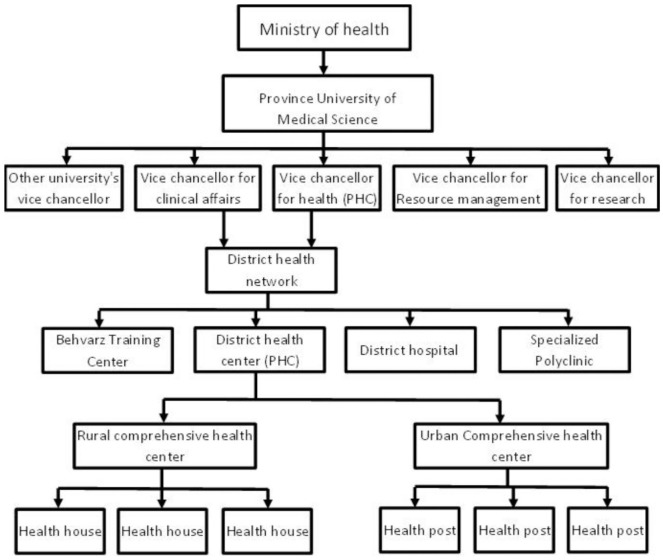

The ultimate goal of the health system of each country is to promote the health of all people so that they can actively participate in economic and social activities, while having adequate health.1 Undoubtedly, today the main strategy for countries to achieve this goal is primary health care (PHC).2 PHC has been established in Iran since 1985 in the form of health care networks in different cities and villages.3 In PHC, the first and widest community contact with the health system has taken place. Service provider units at this level include health houses, health posts, and rural/urban comprehensive health centers (CHCs). Health care providers in health houses include male and female Behvarz and in health posts include family health nurses. In comprehensive urban/rural CHC, general physicians, sometimes dentists, nutritionists, psychologists, and occupational and environmental health experts are usually working4,5 (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

The structure of primary health care in Iran.

The performance and pattern of PHC in Iran has an international reputation and has been visited and praised by experts from various international organizations.6 Today after about 32 years of PHC initiative in Iran in the form of health care networks, many achievements and successes have been obtained in promoting health indexes.7 Despite the brilliant achievements, especially in rural areas, some challenges have emerged in recent years in the field of provision of health services, especially in urban areas. The most important of these challenges are the changing of disease patterns from infectious to chronic, the population aging, unsustainability of resources, hospital-centered health services, use of untrained physicians in managerial positions, deterioration of health centers’ building, changes in people’s needs, increasing urbanization and growing marginal areas of cities with special health needs.7,8 Therefore, the need for fundamental reforms in the management and provision of PHC, especially in urban areas, seems unavoidable.9

Today, different strategies have been used to cope with the challenges of health care system in different countries. The most effective strategy can be public-private partnership (PPP) as a bilateral collaboration and a win-win policy, making use of the abilities of both sides to achieve their goals.10 The private sector knows PPP as an opportunity for market growth and making profit that provides appropriate facilities and innovative management for the public sector.10,11 Public sector also use PPP as an efficient and cost-effective key mechanism to achieve goals and implement policies.12

Another area that seriously addresses the potential use of PPP is the universal health coverage (UHC). UHC is the third goal of sustainable development goals, which most countries are aiming to achieve by 2030.13 The UHC’s goal is to maximize health outcomes through the equitable distribution of financially and geographically accessible high-quality services, ensure efficient service provision, and low out-of-pocket payments in proportion to the individuals’ affordability.14 Countries that seek to realize UHC should use all available resources, including the private sector. So, certainly, PPP is one of the basic strategies for achieving UHC.15 In the Islamic Republic of Iran, in the upstream documents and in many legal articles, PPP has been addressed by national policy makers, which indicates the importance of this issue and support of higher levels of decision-making body.

Various experiences with PPP implementation in PHC have been reported in different countries. For example, the results of a study conducted in Kenya by Bakibinga et al16 show that access to and utilization of health services for women, children, and infants has been improved through PPP implementation. The status of these centers has also been improved in the areas of infrastructure, human resources, information, finance, equipment, and supplies.16 Another study by Baig et al17 in India compared the 3 PHC models, including public, NGOs (nongovernmental organizations), and PPP centers, based on health indexes, managerial performance, and service quality in the view of service recipients. The results showed that there was no significant relationship between the 3 service models based on studied dimensions. In general, public centers were better than other models in access to services, medicines, and infrastructure. On the other hand, NGOs and PPP centers are better than public centers in the provision of laboratory services. All 3 types of service provision models had poor performance in the field of human resources and achievement of predetermined managerial goals.17

In Iran, several studies have been conducted to measure the success of PPP, which show the positive outcomes of this policy. For example, the results of the study by Pour Dolati et al18 study showed that the implementation of the PPP policy has led to improved case finding, patient satisfaction, and affordability. On the other hand, the results of the study conducted by Nikniaz et al19 indicated that compared with public centers, PPP centers have better performance in maternity and child services.

In 1998, health cooperatives were designed by senior managers at the University of Medical Sciences and rolled out in a pilot study at the provincial level in East Azerbaijan Province (EAP). Health cooperatives were a model of PPP that provided the PHC services in the form of a clear and integrated service package using a market-controlled pattern and private sector approach. Through continuous evaluation and based on the quality of services, the public sector’s reimbursement was based on pay for performance and capitation.20

Since early 2014, the initial design for the establishment of health complexes (HC) began as a fundamental strategy for strengthening the health system and moving toward the UHC. This was based on the study of upstream documents, successful reports from other countries, health cooperatives’ experience in the EAP, and a comprehensive analysis the current state of public and private sector. Modification and finalization of the HC plan was carried out based on the views of the Deputy of Health of the Ministry of Health (MOH), the University’s Board of Directors, experts, and consultants from different departments of medical university. The executive guideline, the contract text, and the service package were drafted during April and May 2014. After the approval in the University’s Board of Directors, the rollout of the first HC took place in June 2015, and following initial evaluations and revisions to the plan, the launch of other HCs began in February 2015. Since May 2015, the rest of the province’s cities were gradually covered.20

Although health cooperatives and HCs have both been implemented with the aim of PPP implementation in primary health care, there are some differences between these 2 models. Health cooperatives covered between 9 and 17 000 people, while the population covered by HCs is between 40 and 120 000. HCs consist of several health centers, which one of them is CHC. The population covered by each of these centers approximately equivalent to covered population by a health cooperative. The CHC has 4 specialist physicians (internist, pediatrician, gynecologist, and psychiatrist) who provide specialty services for referrals by family physicians and family health nurses who work at health centers. The nutrition and mental health services added to the service package provided by HC compared with health cooperative. More information on health cooperatives and HCs is provided studies by Tabrizi et al,20 Farabakhsh et al,21 and Bakhtiati et al.22

Given the passing of about 4 years of implementation of PPP in the provision of PHC policy in EAP, it is necessary to review the performance and achievements of this policy. The purpose of this study was to analyze the PPP in PHC policy in EAP.

Methods

In this study, the policy analysis triangle framework was used. This model that designed in 1994 by Walt and Gilson23 to analyze health policy, covering 4 sections. In each section of the policy triangle, the following information examined:

Content: The objectives of PPP in PHC policy in EAP and the contract between the public and private sectors.

Stakeholder: In this section, all stakeholders including influential individuals and organizations were identified and analyzed. To this end, the WHO Stakeholder Analysis Guideline24 has been used. This includes planning the process, selecting and defining a policy, identifying key stakeholders, adapting the tools, collecting and recording the information, filling in the stakeholder table, analyzing the stakeholder table, and using the information.

Context: In this section, economic, political, cultural, and other contextual conditions were examined. To classify the factors related to the context, Licher’s method was used, which includes conditional factors, structural factors, cultural factors, and international factors.25

Process: This section consists of 4 parts: agenda setting, policy design, policy implementation, and policy evaluation. In this study, the framework used for agenda setting was a multiple streams framework developed by John Kingdon (1984).26 In policy development, the process and designing method of PPP in PHC policy was analyzed. In the implementation part, the method of implementation of the policy include the way of preparation of the project executive basics, human resources supply, intra and inter-sectorial communications, contract items, as well as monitoring and evaluation methods were examined. In the evaluation part, performance and achievements of PPP in PHC policy were reviewed based on interviewees’ opinions.

Research Environment

This study was conducted in EAP, the largest and most densely populated province in the northwest of Iran. Based on the population and housing census in 2016, the population of the EAP was 3.9 million, of which 2.809 million (72%) settled in urban areas, of which 530 000, (19%) settled in city marginal areas.

Participants

The participants were informed experts from the following organizations and sectors: Senior officials and managers from the Vice Chancellor for Health of University of Medical Sciences (VCH) and its subordinate units, senior officials and managers from health networks and Tabriz district health center, and experts and authorities from private sectors.

Data Collection

The required data were gathered using qualitative methods. Initially, the required information extracted from the documents related to the development and implementation of the policy (including the regulations, minutes, instructions, recalls, contracts, and other related documents) in the information system of the VCH. In the next stage, interviews were conducted with stakeholders and individuals involved in the implementation of the policy.

At the last stage of the study, semistructured interviews were conducted with 14 current and former managers of the VCH, district health networks’ managers, faculty members with a history of executive and scientific work on PPP, and managers of private HCs. The sampling method was purpose based and participants were selected heterogeneously. Inclusion criteria for participants were having at least 5 years of management experience or executive activity in relation to the providing PHC services, faculty members with a background in PPP research, having at least bachelor’s degree in medical sciences, having enough knowledge in PHC (publishing books, papers, reports, etc), and having the desire and ability to participate in the study.

Interview sessions were planned and implemented based on the willingness of the participants and with prior notice and sending information sheets including the objectives, methodology and interview questions. Each session lasted between 40 and 150 minutes, and the participants were free to leave the study if they deprecate the process of sessions and how to use the results. With the consent of the participants, their conversation was recorded and after each interview transcribed immediately. In addition, notes were taken during the interviews.

To increase the consistency and accuracy of the study, 4 criteria proposed by Guba and Lincoln27 (including credibility and confirm ability, dependability, and transferability) were applied. In order to obtain credibility and confirm ability criteria, submergence and review by research colleagues and participants and expert opinions were used. For dependability, 2 people were used for coding. Finally, for transferability, the experts’ opinions, as well as heterogeneous and purposeful sampling, were used.

Data Analysis

Data were analyzed by content analysis method. The text of the interviews was reread several times to fully understand the concepts and themes; then the data were coded, then main themes were extracted from the primary codes. Data encoding was done by two researchers. In data analysis, criteria of acceptability, transparency, integration, repeatability, and reliability were applied. Results from the review of documents are presented descriptively in the results section. MaxQDA10 software was used for content analysis.

Ethical Approval

The study had been approved by the Ethics Committee of the authors’ institute (Ethical Number: TBZMED.REC.1397.597). Ethical issues (including the informed consent of the participants, plagiarism, duplication, etc) are fully respected by the authors. The confidentiality principles are respected in the information of individuals. The individuals have been assured that the results of the study would be used only for the purposes of the study not in any other cases, and each person was allowed to leave the study at any stage of study without any loss.

Results

The findings of this study are presented in 4 sections: context, content, stakeholders, and process.

Context

Contextual factors were classified according to the Licher’s method25 (Table 1).

Table 1.

Contextual Factors of Public-Private Partnership in Primary Health Care Policy in East Azerbaijan Province, Iran.

| Factor | Description | Quotation of Participants | |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Conditional factors | According to the participants in this study, conditional factors have no effect on the development and implementation of this policy. | — |

| 2 | Structural factors | a) Political issues: Simultaneously with the coming of the new government, with the slogan “Promoting people’s health”, the HEP was designed and launched. The plan started from the clinical sector and later was implemented in the PHC. Participants believed that the project was politically well supported. On the other hand, upstream documents supported the participation of the private sector in different areas. Participants believed that there were good political supports at the beginning at provincial and national levels (such as governors, parliament members), but then, the officials and policymakers forget the plan and provided poor support. | Participant No. 7: “We trusted the individuals and the

officials who supported the plan, but later . . . they did

not keep their words.” Participant No. 2: “. . . political forces sought people’s satisfaction that is the precursor of political consent . . .” Participant No. 9: “. . . In general policies of the regime and MOH emphasized the entry of private sector in the health sector because services should be provided actively and the government with limited resources is not able to provide active services to the entire population”. |

| b) Economic issues: The economic situation in the country has had a significant impact on the implementation of PPP policy. Participants believed that financial support was good at the beginning, but then faced some problems during the implementation. | Participant No. 1: “. . . the MOH failed to provide money for the health sector and the university was not able to give all the money to the VCH . . . It was like a melting snowball that had become very small when came to us.” | ||

| c) Technical issue: • Private sector: According to interviewees, since the low number it was difficult to attract private companies to participate in the bidding and HCs management. On the other hand, companies were reluctant to participate in and collaborate with the public sector due to their experience from health cooperatives in 1998. For this reason, the policy designer team had to give greater privilege to private companies by different incentives. • Public sector: According to the participants, there were no problems with the technical aspect on the public side. The health centers previously set up for public services were used, and in some areas where there were no public centers for provision of services, locations were provided with the help of the municipality, or buildings were rented by HCs. |

— | ||

| 3 | Cultural factors | a) People: Since people did not interfere in the design and development of this policy, they were indifferent to its implementation. The design team performed a wide notification to overcome these problems, and HCs had extensive public education in their areas. This led to people trust in these centers and, consequently, resulted in greater cooperation. Nonetheless there is still room for improvement. | — |

| b) Organizational culture: The managers of private companies believed that the lack of cooperation of public sector (including the headquarter staff or even VCH and district health networks managers) with this policy, and sometimes unawareness of other university’s vice chancellors of the policy’s implementation has created many problems and barriers in implementation. | Participant No. 3: “. . . The main obstacles were in our own system; there was no common language, especially at Intermediate levels and below . . .” | ||

| c) Public sector employees: According to one of the participants, one of the biggest cultural problems was that the body of the government has not grown intellectually in accordance with the PPP ideas. This means that public sector employees do not have a positive view of partnering with the private sector and sometimes see it as a threat to of their jobs security. | — | ||

| 4 | International or external factors | In their interviews, participants did not mention the international or external factors that underlie this policy, but it seems that encouraging to use of private sector capacity in international plans, including UHC,28 family practice,29 and strengthening health system programs,30 presented by the World Health Organization and the Eastern Mediterranean Regional Office (EMRO), have influenced the designers of this policy to use the power of the private sector. | — |

Abbreviations: HEP, health evolution plan; PHC, primary health care; PPP, public-private partnership; HC, health complex; MOH, Ministry of Health; VCH, Vice Chancellor for Health of University of Medical Sciences; UHC, universal health coverage.

Content

Policy Objectives

One of the important issues in this section is the objectives of the PPP in PHC policy. Different participants had stated different objectives for this policy, which were addressed in 6 themes (Table 2).

Table 2.

The Objectives of Public-Private Partnership in Primary Health Care policy in East Azerbaijan Province, Iran.

| Objectives | Quotation of Participants | |

|---|---|---|

| 1 | Decreasing the public sector tenure | Participant No. 2: “In fact, we bought the service . . . The public health system and the MOH could leave providing services and become an observer. Could easily have done monitoring and supervision.” |

| 2 | Using the power of the private sector | Participant No. 2: “. . . The use of the private sector was raised so that we could use the potential, ability, and skill of the private sector.” |

| 3 | Attracting people’s participation | Participant No. 10: “By attracting the private partnership, the community partnership which was one of the principles of the PHC, was realized . . .” |

| 4 | Improving the PHC system efficiency | Participant No. 3: “If the government wants to spend low and get good result, current public system will not work. With this structure and manpower, there will not be a good result . . . will lose both money and reputation.” |

| 5 | Modifying the payment system | Participant No. 10: “Maybe, one of the goals of this policy was to change the payment system (and setting up) pays for quality and performance . . .” |

| 6 | Increasing justice | Participant No. 1 stated: “. . . When we say to complete the population coverage . . . When we say to increase the number and diversity of the service, and when we say to have the highest financial protection, it means justice . . .” |

Abbreviations: PHC, primary health care; MOH, Ministry of Health.

Contract

The policy design team from the VCH, with the help of members of the University’s Legal Affairs, Vice Chancellor for Resource Management Affairs of University of Medical Sciences, university security department, and representatives of private sector, developed the initial contract considering current conditions. This contract included the following items:

Contract Subject: Region health management and provision of health care services according to the laws and regulations of the MOH, which the universities of medical sciences are required to implement.

Duration of contract: All contracts are adjusted for a period of 3 years and after that, in case of agreement and satisfaction of performance, they can be extended or moderated. The deployment of human resources and the launch of services provision that must be verified by the contractor are the basis for the start of a contract and capitation payment. Guaranteeing the contract is annual and based on the capitation of same year.

The covered population: The census and blocked population is the basis for payment for the first quarter of the contract. During implementation of the contract, population changes can be calculated quarterly according to the information recorded in the electronic system that will be the basis for payment.

Place of providing services: CHCs (management headquarters of health complexes) and health centers.

Types of services: (A) Services included in capitation such as vaccination, basic and periodic visits, target groups care, oral and dental health services for target groups and pre-pregnancy tests for mothers are free and no franchise gotten from the covered population for providing these services. (B) In case of services not included in capitation such as outpatient visits and pharmaceutical and paraclinical services, franchise is gotten from the covered population for providing these services and the remaining costs are received from the insurance companies. (C) About services that are not included in capitation, such as injections and dressings, and some dental services, the total cost received from service receivers or insurance companies under government tariffs.

Monetary value of the contract and financial turnover: The service capitation is based on the announced capitation by the Tabriz University of Medical Sciences and the mutual agreement. Total cash and non-cash incomes of services provision not included in capitation deposit into the bank account of the network and after taking legal procedure, will be returned to HC account in full. Review and confirm the covered population in the information system done by the employer quarterly that is the basis for reimbursement to the contractor for the next quarter.

Contractor’s obligations: Work hours, how to deal with the breach of contract, to record information and legal fractions.

Employer’s obligations: To provide required hygienic items, conduct monitoring and evaluation, reimbursement conditions and education.

Monitoring and evaluation: Monitoring and evaluation content, bonus and its payment method.

Performance and obligations guarantee: The contractor must submit a valid bank guarantee equivalent to 10% of the total amount of the contract to the employer when signing the contract. If the contractor fails to comply with any of his obligations, the employer will confiscate the guarantee without any legal formalities in favor of the university.

Government employees’ intervention prohibition act: The contractor is not subject to intervention prohibition act and if it is found otherwise, the contractor is obliged to compensate the employer for damages.

Termination of contract: Employer can terminate the contract unilaterally and terminate the activity of contractor if finding any contractor’s violation of the provisions of this contract and the contractor has no right to protest and in case of damage from the contractor, the employer can confiscate the guarantee and financial claims of the contractor and also claims any damages occurred more than the amount of guarantee and claims.

Dispute resolution: The parties will try to resolve disputes arising from the contract in a friendly manner, otherwise the matter will be resolved in presence of representatives of vice chancellor for health and contractor at the Financial and Trading Expert Commission of the university.

Residence of parties to the contract: Each party to the contract is obligated to inform other party in writing if the address is changed; otherwise the previous address is valid for official notification.

Stakeholder Analysis

The characteristics of the stakeholders have been determined by kind, position, motivation, and effect (it should be noted that all the characteristics were not exactly extracted from the interview but, based on the experience of the research team, the status of the stakeholders was determined on the basis of these characteristics; Table 3).

Table 3.

Key Stakeholders of Public-Private Partnership in Primary Health Care Policy in East Azerbaijan Province, Iran.

| Stakeholder | Kind | Position | Motivation | Effect | |||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Individual | Group | Organization | Internal (Subsidiary of University) | External | Financial | Nonfinancial | Effective | Affected | Positive | Negative | Obviously | Secretly | Consciously | Unconsciously | Designing | Implementation | |

| University’s Vice Chancellor for Health | * | * | * | * | * | * | * | * | * | * | |||||||

| University Board of Directors | * | * | * | * | * | * | * | * | |||||||||

| University president | * | * | * | * | * | * | * | * | * | * | |||||||

| Deputy of health of ministry of health | * | * | * | * | * | * | * | * | * | ||||||||

| Minister of Health | * | * | * | * | * | * | * | * | |||||||||

| University’s Vice Chancellor for Resource management affairs | * | * | * | * | * | * | * | * | * | * | * | ||||||

| Other University’s Vice Chancellor | * | * | * | * | * | * | * | * | |||||||||

| Health insurance companies | * | * | * | * | * | * | * | * | * | ||||||||

| University’s office for Legal Affairs | * | * | * | * | * | * | * | * | |||||||||

| Municipality | * | * | * | * | * | * | * | * | |||||||||

| Department of education | * | * | * | * | * | * | * | * | * | ||||||||

| Public sector employee | * | * | * | * | * | * | * | * | * | * | * | ||||||

| Politicians | * | * | * | * | * | * | * | * | * | * | |||||||

| people (households) | * | * | * | * | * | * | * | * | * | * | * | * | |||||

| planning and budget organization | * | * | * | * | * | * | * | * | * | ||||||||

| Supportive organizations (Imam Khomeini Relief Foundation, State Welfare Organization) | * | * | * | * | * | * | * | * | |||||||||

| Private doctors (physicians working in individual or group department) | * | * | * | * | * | * | * | * | * | * | * | ||||||

| Private sector (managers and employees) | * | * | * | * | * | * | * | * | * | * | |||||||

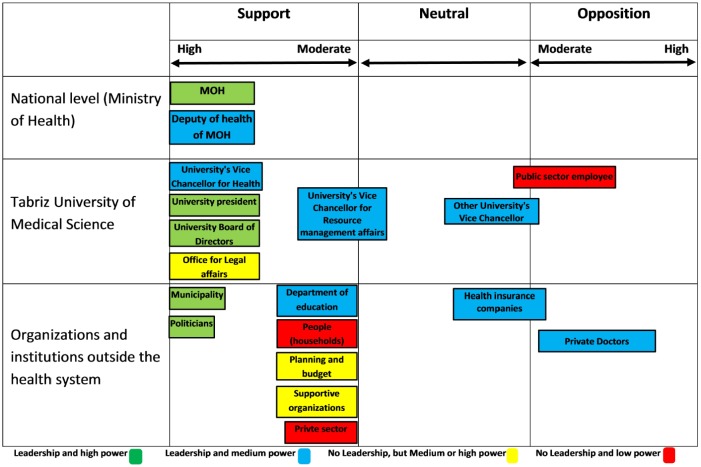

Based on the information obtained from stakeholder analysis in the present study, a stakeholder position map was designed at three levels of national, university, and other organizations out of health system. In this study, University of Medical Sciences was considered as the main responsible organization for this policy (Figure 2).

Figure 2.

Position map of key stakeholders of public-private partnership in primary health care policy in East Azerbaijan Province, Iran.

Process

The study results in this section are discussed in 4 sections “agenda setting,” “policy design,” “policy implementation,” and “policy evaluation.”

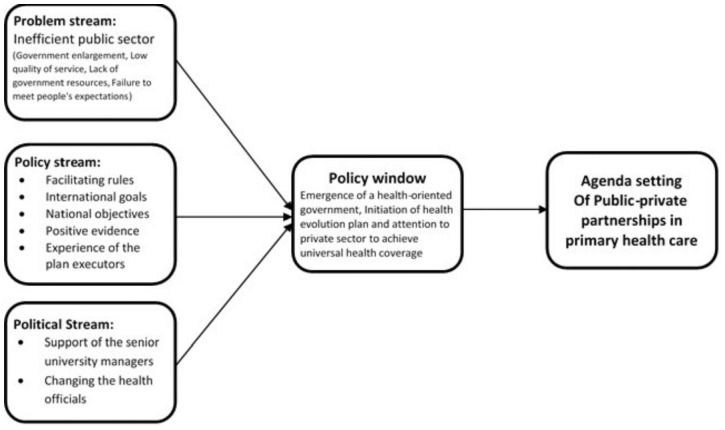

Agenda Setting

In this section, the factors leading to the setting this policy as the agenda is presented in the form of problems, policies, and political streams (John Kingdon, 1984,26Figure 3).

Figure 3.

The flow of multiple streams about the agenda setting of public-private partnership in primary health care policy in East Azerbaijan Province, Iran.

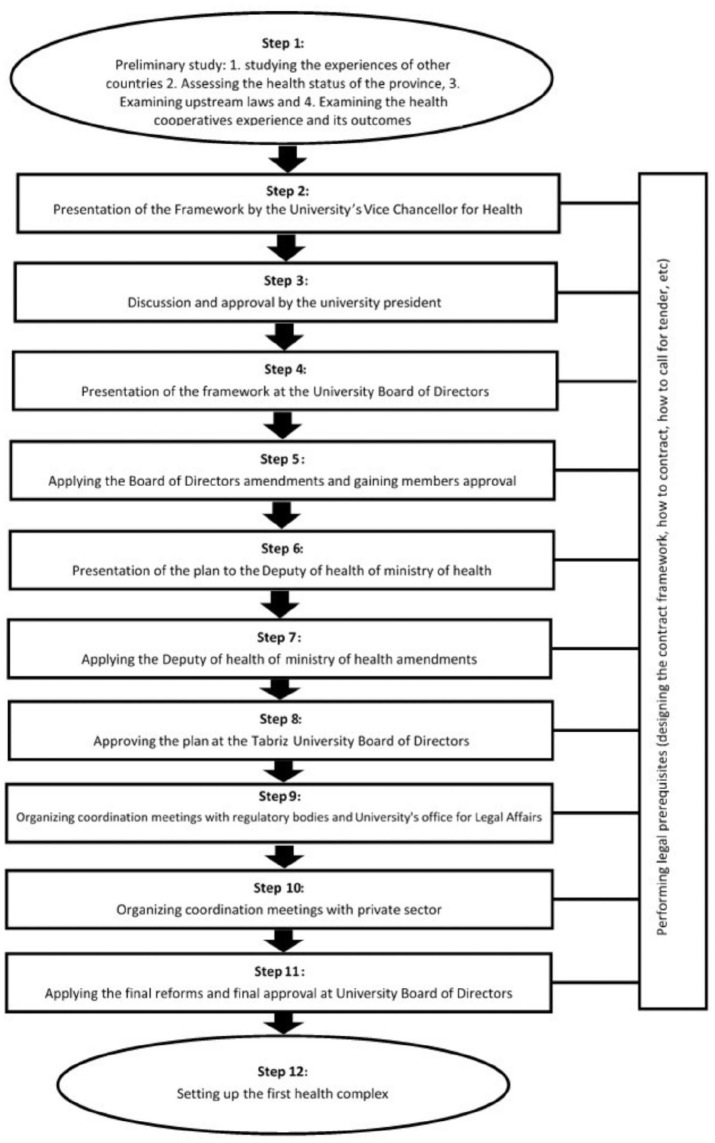

Development Process

The development and preparation of the policy is illustrated in Figure 4.

Figure 4.

The process of developing public-private partnership in primary health care policy.

Implementation

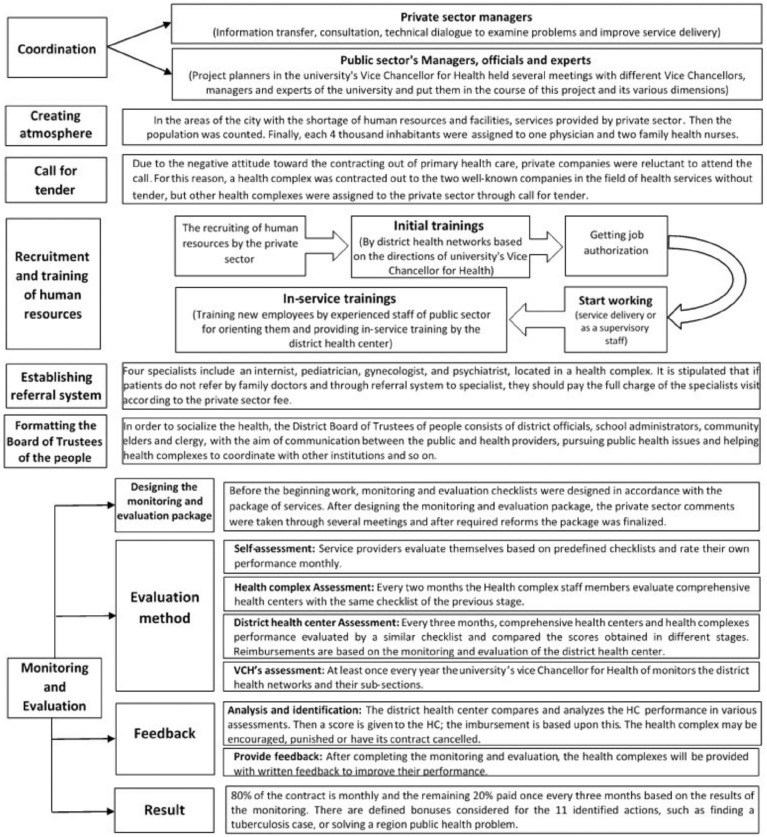

The dimensions of the implementation of the policy were examined in 7 areas (Figure 5).

Figure 5.

The implementation of public-private partnership policy in primary health care in East Azerbaijan Province, Iran.

Further details like the human resource composition, reimbursement methods to HCs, and so on are being published in other under review papers.

Evaluation

(a) Weaknesses and Strengths: The weaknesses and strengths of this policy were described under 3 main themes and 8 subthemes and 4 main themes and 13 subthemes, respectively (Table 4).

(b) Achievements: In this section, the policy’ achievements are presented in the form of 4 main themes and 23 subthemes (Table 5).

Table 4.

The Weaknesses and Strengths of Public-Private Partnership in Primary Health Care Policy in East Azerbaijan Province, Iran.

| Main Theme | Subtheme | |

|---|---|---|

| Weaknesses | Lack of background | Lack of infrastructure |

| Lack of notification about the plan | ||

| Neglecting private sector physicians | ||

| Monitoring and evaluation | Failure to define correct goals and indexes | |

| Long monitoring and evaluation process | ||

| Insufficient transparency of checklists | ||

| Contract | Short-term contract | |

| Structure of pay for performance | ||

| Strengths | Planning and policy making | Having scientific justification |

| Integrated service package | ||

| Changing the role of the public sector | ||

| Execution | Active follow-up (of covered population) | |

| Increase working hours | ||

| Better implementation of health plans and programs | ||

| Reducing layers of bureaucracy | ||

| Providing secondary health services alongside primary health care | ||

| Increasing networks’ functional potential | ||

| Monitoring and evaluation | Precise monitoring and evaluation | |

| Increasing a control level | ||

| Payment system | — |

Table 5.

Results and Achievements of Public-Private Partnership in Primary Health Care Policy in East Azerbaijan Province, Iran.

| Main Theme | Subtheme | Quote of Participants |

|---|---|---|

| Structural and managerial | Identifying the weaknesses of the public sector | Participant No. 13: “. . . It was a great achievement that had been showed the public sector has many weaknesses that private sector can cover . . .” |

| Training multiskilled human resources (family health nurses) | Participant No. 7: “One of the achievements was the training of multi-skilled human resources that did a lot of work . . .” | |

| Implementation of family practice | Participant No. 2: “We could implement family practice . . . The people know their family physician; they are in touch with him/her, and an intimate relationship has been created between the physician and family health nurse with the people . . .” | |

| Promoting employees’ motivation | Participant No. 2: “. . . Reluctant employees were one of our most important problems in the previous public structure. Since payment in the private sector was based on monitoring, the motivation of the staff was increased . . .” | |

| Developing service packages | — | |

| Improving service delivery physical space | Participant No. 1: “. . . I think the physical space of service delivery has been improved and there is a decent space for people in health centers . . .” | |

| Creating infrastructure | Participant No. 3: “The plan succeeded in creating some infrastructures. It developed the SIB system (health information system), and provided human resource and physical space . . .” | |

| Public satisfaction | Participant No. 5: “. . . In monitoring and evaluation, focused on customer’s satisfaction considerably, and the results showed a high increase . . .” | |

| Service delivery | Self-care | Participant No. 9: “. . .There was no (Specific program for) self-care before; now you can see people are trained and take care of themselves.” |

| Identifying patients | Participant No. 2: “Compared to the past, we identified a number of people who were sick but they did not know and had not yet been identified . . .” | |

| Improving health indexes | Participant No. 1: “. . . Definitely, when you can increase the coverage and provide an active service, the people’s health will improve, which is the program’s strength.” | |

| Providing active services | Participant No. 9: “. . . Providing active services are the most important strength of this policy and makes all the goals of this policy come true.” | |

| Promoting population coverage | Participant No. 1: “. . . We did not have such access (to health services) in urban areas; now it is available for 100% of the population. This was a very strong point . . .” | |

| Economic | Reducing costs | Participant No. 1: “. . . while having a comprehensive service (comprehensive service package), our costs have been reduced relatively . . .” |

| Decreasing average medicine consumption | Participant No. 6: “. . . During this period (since policy implementation), the average medicine consumption has decreased . . .” | |

| Better use of resources | Participant No. 3: “by this policy the resources were used better and overuse prevented . . .” | |

| Social and political | Providing social justice | Participant No 3: “. . . Rich people pay attention to their own health . . . They refer directly to private sector and secondary and tertiary level services, and do not refer to the PHCs (primary health centers) so much. But low-income households go to the PHC (for their health needs) . . .” |

| Increasing public trust | Participant No. 1: “. . . We measured the trust of the people . . . As I remember, in the first two years, we had about 40% to 45% increase in people’s trust in the health system . . .” | |

| People’s participation | Participant No. 1: “We formed people’s board of trustees in each of the HCs; we took their opinions, and asked for their help . . . It was very interesting; they became our active arm. In their neighborhoods and ceremonies, they encouraged their neighbors to (refer to health complexes and) get these services” | |

| Creating jobs | Participant No. 5: “. . . Graduates of various medical courses employed without imposing any cost on the public sectors.” | |

| Obtaining authorities and policy makers’ trust | Participant No. 1: “. . . We could obtain the accompaniment of local religious leaders, district and provincial authorities, university directors and even national officials . . .” | |

| Breaking the taboo of change in PHC | Participant No. 8: “. . . When the health minister speaks, he says: “We feel very strong now because we have the private sector, it’s a mistake to leave the private sector . . . This is very important . . . today, in the policy makers and directors’ meetings, one of the common strategies is that this service could transfer to the private sector.” |

Discussion

About 10 million people in Iran live in the marginal areas of big cities. Regarding the poor health in the marginal areas of cities, MOH has considered health interventions in order to improve the health status of these areas.13 Implementation of the HEP in EAP has different features and structure and this province has many innovations in this field. In this study, PPP in the provision of PHC policy in the EAP has been analyzed.

Context

The results of the study showed that the support of PPP by the political parties was one of the factors influencing the implementation of this policy. But this support was only provided in the early stages of implementation; later political support diminished, which causing problems with the execution of the plan. Economic problems and financial resources unsustainability can also be due to weak political support. In the study of Christia et al31 in Guatemala, major changes to the PPP in PHC program due to election and government change was one of the challenges of the plan.

On the other hand, it seems that the coincidence of implementation of this policy with the implementation of the HEP in the country, which brought a lot of financial resources to the health system, have led to all required budget for PPP policy be provided. When the government faced economic fluctuations, the health budget also fell sharply, and the PPP in PHC policy is no exception, and since then, there have been many problems that could jeopardize the existence of the policy. In a study conducted in Bangladesh by Islam et al,32 an assessment of PPP policy in providing PHC in urban areas, showed a reduction of state aid from 26% of the total project budget in the early stages of the plan to 12%, can led to uncertainty in the project’s continuity in the following years.

In general, most participants believed that because of the availability of technical expertise in the public sector, especially the scientific capability and experience of the policy designer team, there was no way to official and policy makers to opposite this policy. Also, technically, especially in the field of human resources, there was no such problem which can drop the existence and continuity of the policy into trouble. The only technical problem was the shortage of physicians, which has been one of the main concerns of health system in PHC sector since past. This is considered due to better working conditions in other sectors in comparison with PHC. The results of the study carried out by Islam et al32 showed that physicians are reluctant to attend in PHC, due to lack of professional development and low salaries.

In general, cultural barriers did not affect the development of this policy, but there were some cultural problems in the implementation phase due to the issues such as lack of familiarity with policy in different organizational levels of public sector. It seems that proper public notification is necessary to justify all public sectors, other public organizations (health insurance companies, municipality etc), politicians and people before and after the implementation of the policy.

Content

From the findings of this study, it can be concluded the social justice was the main goal of policy implementation, although other organizational goals also were followed. The social justice is the driving force and the main goal of many reforms and interventions in health systems.33,34 The 2008 World Health Organization report highlights social justice as the main pillar and key component of PHC reforms.35

Stakeholder Analysis

The number of university internal stakeholders who support the policy is considerable; hence the likelihood of formation a coalition is high. University officials can attract these stakeholders’ cooperation through involving them in redesigning and implementation process. There are various ways to get support of insurance companies and other university’s vice chancellors, who are neutral for this plan. They can be involved in the process of implementing or redesigning and modifying different parts of the plan. They should also be encouraged to engage in the implementation of this policy using various methods such as providing financial and non-financial incentives. They must be persuaded to support PPP in PHC policy and increase their power to the extent necessary.

On the other hand, private-sector physicians are considered to be opposing stakeholders who have moderate leadership and power, which their power should be reduced, or could negotiate with them and justify them about the benefits of the plan, or could offer incentives for their coordination with the plan. It seems that attracting the intra-organizational supporters will strengthen the position of the policy against private-sector physicians.

More decision-making power can be given to people and the private companies that support the plan, but lack leadership and have moderate to weak power, to increase their power and leadership. They can be invited to participate in the implementation process and solve the challenges and problems; which is one of the health socialization ways. Also, health education through mass media, creating various grassroots campaigns, and attracting people’s participation in identifying problems and planning to solve them are the other effective solutions that can strengthen these supporters and facilitate the health socialization.

In order to preserve the support of stakeholders who have high power and leadership, basic concepts and achievements of policy must be explained to them and get their help to solve problems and provide solutions for the challenges of PPP in PHC policy. For example, Department of Education’s influence on parents can be used to provide better health education and periodic health examinations services to students and households.

In order to attract the support of public sector employees who were the opponents with no leadership and low power, continuous and planned coordination meetings can be organized. It is also possible to explain the various dimensions of the plan to them and use their comments and assure them that the implementation of the plan will not endanger their interests.

Process

Agenda Setting and Development Process

It seems that the public sector’s inefficiency in providing PHC is the main problem stream that set PPP policy in agenda. The existence of facilitating laws and national and international goals, along with the presence of a policy designer team who had experience of implementation of PPP in the form of health cooperatives in 1998 and the positive outcomes of that plan, provided a platform for proposing this policy to improve current system.

On the other hand, the coincidence of PPP policy with the HEP was an opportunity to facilitate the development and implementation of this policy. Organizing coordination meetings and inviting managers who had participated in the experience of the health cooperatives, as well as inviting private sector representative and academic specialists to attend service package, monitoring, contract development, and calculating capitation, and meetings during the policy development phase are the strengths of this policy and kind of innovation.

Implementation

It seems that the considerable points in the implementation of this policy are coordination meetings, staff training method, establishment of referral system, and monitoring and evaluation method. But for the continuity of these strengths, it seems necessary to sustainability in management and policy implementation style.

Evaluation

Some of the weaknesses of this plan were predictable and correctable before the implementation, and they should have been considered by the design team. On the other hand, there were unpredictable problems and weaknesses that were identified during the implementation. Since there was not much experience in this field in Iran, incidence of some problems and weaknesses were not unexpected. But it seems that, as many participants suggested, a pilot study could help identify and resolve these weaknesses before implementation the plan on a wide scale.

The results of this study emphasized more on the “lack of infrastructure” as a fundamental weakness. It seems that the project’s executives considered solving of some infrastructure beyond the health system, because it requires a change in the national level by all beneficiary institutions and organizations which are not easily possible. On the other hand, the time limitation was one of the serious obstacles to the solution of the infrastructure problems of this policy, which could cause it to stop. It seems that the solution of the aforementioned problem requires comprehensive political support from the beneficiary upstream institutions. In the study by Dehnavieh et al,35 who examined the implementation of PPP in PHC policy as an experience in health system reform, lack of facilities, high workload due to lack of some human resources—specially physicians—unsustainability in financial resources, and lack of health insurance companies’ cooperation have been identified as the weaknesses of this policy.

The main strengths of this policy, in terms of high emphasis and consensus of participants, were improving access to services, active follow-up, providing secondary health services alongside PHC, changing the role of the public sector, accurate monitoring and evaluation, and setting up pay for performance and quality of service system. Despite the emphasis of public sector interviewees on the accuracy of monitoring and evaluation, the private sector representatives believed that there are some deficiencies in monitoring and evaluation system; which the quality and accuracy of the process could be improved through eliminating them. Stakeholders’ opinions indicate that one of the solutions to this problem would be to organize coordination meetings between the public and private sectors to achieve common language. Based on the results of the study by Dehnavieh et al,36 decentralized planning, strengthening the engagement of the private sector, using the performance assessment methods more appropriately, using the prospective payment method, strengthening the referral system, strengthening service continuity, facilitating financial access, and increasing geographical access especially in marginalized areas, are the strengths of this policy.

The main achievement of this policy, in the view of interviewees, was the improvement of social justice (through the improvement of access, quantity, and quality of service) that all participants agreed on. The interviewees believed that the implementation of the plan had improved the access and utilization of poor and marginalized people. In the study conducted by Bakhtiari et al22 exploring the results of PPP in PHC policy at EAP, it was shown that financial, physical and even cultural access (service acceptance) to PHC services has been improved. The results of the study carried out by Reeve et al37 showed that, about 6 years after the strengthening of PHC in Australia, the quantity and quality of care provided to marginalized people have been dramatically increased, which was higher in deprived areas.

Despite the mentioned strengths and weaknesses, stakeholders have described this policy as relatively successful and helpful in solving the problems of the PHC system. This seems to be a good ground for gaining stakeholders’ support to form a unified and powerful coalition to address problems.

Study Limitations

Since this study is the policy analysis in a retrospective way, one of the limitations of the study is the recall bias that can affect the accuracy of the information. In a part of this study, the existing documents were used to extract information. Given that this information was not collected for research purposes, some of them were less suitable for study purposes.

Conclusions

Simultaneously with the implementation of the HEP in Iran, EAP developed and implemented PPP in PHC policy in order to achieve UHC, which have significant differences with the country model. Analysis of this policy showed that the implementation of the HEP at the country level and the political support for these reforms paved the way for implementation of PPP in PHC policy in EAP. The results of the study indicate that the main goal of this policy was to realize UHC with an emphasis on marginalized areas, expansion of service packages, and reduction of out of pocket payments. On the other hand, this policy has not faced serious opposition from the various stakeholders. Also, according to the results of the study, the main reason for the design and implementation of PPP policy in PHC was the public sector inefficiency to completely provide PHC to all people. The main part of the development of this policy in EAP was conducted by a team from VCH in cooperation with various departments of university of medical sciences and the views of national authorities of the health system were used to edit and correct it. This policy was implemented in the form of private HCs using a defined service package and capitation payment for a specific population on the margins of EAP’s cities. The results of qualitative and quantitative evaluation of this policy indicate it’s relatively successful. But the continuity of policy success requires comprehensive political support, sustainable financing, organizational and political sustainability, coordination between the university’s internal departments and between politicians and national level authorities, and the constructing culture among people and authorities through notification about the achievements and successes of the policy. Given the nature of health care, in a short period of time it is not possible to extract output and effectiveness data, except in a limited number of cases. So, designing a systematic and accurate program to measure and evaluate the success of this policy accurately, would be useful. Policy designers can use the extracted information to attract stakeholders and identify the strengths and weaknesses of the policy.

Acknowledgments

This is part of PhD thesis funded and supported by Tabriz University of Medical Sciences and Tabriz Health Services Management Research Center. Hereby, we appreciate all the participants from the private and public sectors in this study.

Footnotes

Declaration of Conflicting Interests: The author(s) declared no potential conflicts of interest with respect to the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

Funding: The author(s) disclosed receipt of the following financial support for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article: This study supported by Tabriz Health Services Management Research Center, Tabriz University of Medical Sciences. However, the Research Center played no roles in study design, data collection, analysis, writing or submitting to publication.

ORCID iD: Hojatolah Gharaee  https://orcid.org/0000-0002-9354-4175

https://orcid.org/0000-0002-9354-4175

References

- 1. Franken M, Koolman X. Health system goals: a discrete choice experiment to obtain societal valuations. Health Policy. 2013;112:28-34. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Starfield B, Shi L, Macinko J. Contribution of primary care to health systems and health. Milbank Q. 2005;83:457-502. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Shadpour K. Primary health care networks in the Islamic Republic of Iran. East Mediterr Health J. 2000;6:822-825. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Malekafzali H. Primary health case in Islamic Republic of Iran. J Sch Public Health Institute Public Health Res. 2014;12:1-10. [Google Scholar]

- 5. Sadrizadeh B. Health situation and trend in the Islamic Republic of Iran. Iran J Public Health. 2001;30:1-8. [Google Scholar]

- 6. Mehrdad R. Health system in Iran. JMAJ. 2009;52:69-73. [Google Scholar]

- 7. Lankarani KB, Alavian SM, Peymani P. Health in the Islamic Republic of Iran, challenges and progresses. Med J Islam Repub Iran. 2013;27:42-49. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Vafaee-Najar A, Nejatzadegan Z, Pourtaleb A, et al. The quality assessment of family physician service in rural regions, Northeast of Iran in 2012. Int J Health Policy Manag. 2014;2:137-142. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Heshmati B, Joulaei H. Iran’s health-care system in transition. Lancet. 2016;387:29-30. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Kraak VI, Harrigan PB, Lawrence M, Harrison PJ, Jackson MA, Swinburn B. Balancing the benefits and risks of public–private partnerships to address the global double burden of malnutrition. Public Health Nutr. 2012;15:503-517. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Vian T, McIntosh N, Grabowski A, Nkabane-Nkholongo EL, Jack BW. Hospital public–private partnerships in low resource settings: Perceptions of how the Lesotho PPP transformed management systems and performance. Health Syst Reform. 2015;1:155-166. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Osborne S. Public-Private Partnerships: Theory and Practice in International Perspective. Abingdon, England: Routledge; 2002. [Google Scholar]

- 13. Iyer V, Sidney K, Mehta R, Mavalankar D. Availability and provision of emergency obstetric care under a public–private partnership in three districts of Gujarat, India: lessons for Universal Health Coverage. BMJ Global Health. 2016;1:e000019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. McPake B, Hanson K. Managing the public–private mix to achieve universal health coverage. Lancet. 2016;388:622-630. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Wadge H, Roy R, Sripathy A, Fontana G, Marti J, Darzi A. How to harness the private sector for universal health coverage. Lancet. 2017;390:e19-e20. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Bakibinga P, Ettarh R, Ziraba AK, et al. The effect of enhanced public–private partnerships on maternal, newborn and child health services and outcomes in Nairobi—Kenya: the PAMANECH quasi-experimental research protocol. BMJ Open. 2014;4:e006608. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Baig MB, Panda B, Das JK, Chauhan AS. Is public private partnership an effective alternative to government in the provision of primary health care? A case study in Odisha. J Health Manag. 2014;16:41-52. [Google Scholar]

- 18. Pour Doulati S, Ashjaei K, Khaiatzadeh S, Farahbakhsh M, Sayffarshd M, Kousha A. Development of public private mix (PPM) TB DOTS in Tabriz, Iran. Health Inform Manag. 2011;8:164. [Google Scholar]

- 19. Nikniyaz A, Farahbakhsh M, Ashjaei K, Tabrizi D, Sadeghi-Bazargani H, Zakeri A. Maternity and child health care services delivered by public health centers compared to health cooperatives: Iran’s experience. J Med Sci. 2006;6:352-358. [Google Scholar]

- 20. Tabrizi JS, Farahbakhsh M, Sadeghi-Bazargani H, Hassanzadeh R, Zakeri A, Abedi L. Effectiveness of the health complex model in Iranian primary health care reform: the study protocol. Patient Prefer Adherence. 2016;10:2063-2072. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Farahbakhsh M, Sadeghi-Bazargani H, Nikniaz A, Tabrizi JS, Zakeri A, Azami S. Iran’s experience of health cooperatives as a public-private partnership model in primary health care: a comparative study in East Azerbaijan. Health Promot Perspect. 2012;2:287-298. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Bakhtiari A, Takian A, Sayari AA, et al. Design and deployment of health complexes in line with universal health coverage by focusing on the marginalized population in Tabriz, Iran. Q J Teb va Tazkyie. 2017;25:213-232. [Google Scholar]

- 23. Walt G, Gilson L. Reforming the health sector in developing countries: the central role of policy analysis. Health Policy Plan. 1994;9:353-370. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Schmeer K. Stakeholder analysis guidelines. https://www.who.int/workforcealliance/knowledge/toolkit/33.pdf?ua=1. Accessed September 25, 2019.

- 25. Buse K, Mays N, Walt G. Making Health Policy. London, England: McGraw-Hill Education; 2012. [Google Scholar]

- 26. Khodayari-Zarnaq R, Ravaghi H, Mosaddeghrad AM, Sedaghat A, Mohraz M. HIV/AIDS policy agenda setting in Iran. Med J Islam Repub Iran. 2016;30:392. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Guba EG, Lincoln YS. Epistemological and methodological bases of naturalistic inquiry. ECTJ. 1982;30(4):233-52. [Google Scholar]

- 28. World Health Organization. Universal Health Coverage: Moving Towards Better Health: Action Framework for the Western Pacific Region. Manila, Philippines: WHO Regional Office for the Western Pacific; 2016. [Google Scholar]

- 29. World Health Organization. Conceptual and strategic approach to family practice: towards universal health coverage through family practice in the Eastern Mediterranean Region.https://apps.who.int/iris/handle/10665/250529. Published 2014. Accessed September 25, 2019.

- 30. Alliance of Health Policy and System Research; Global Forum for Health Research. Strengthening health systems: the role and promise of policy and systems research. https://www.who.int/alliance-hpsr/resources/publications/hssfr/en/. Accessed September 25, 2019.

- 31. Cristia J, Evans W, Kim B. Does Contracting-Out Primary Care Services Work? The Case of Rural Guatemala. IDB working paper series. Washington, DC: Inter-American Development Bank; 2011. [Google Scholar]

- 32. Islam R, Hossain S, Bashar F, et al. Contracting-out urban primary health care in Bangladesh: a qualitative exploration of implementation processes and experience. Int J Equity Health. 2018;17:93. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Burström B, Burström K, Nilsson G, Tomson G, Whitehead M, Winblad U. Equity aspects of the Primary Health Care Choice Reform in Sweden—a scoping review. Int J Equity Health. 2017;16:29. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. DeMeester RH, Xu LJ, Nocon RS, Cook SC, Ducas AM, Chin MH. Solving disparities through payment and delivery system reform: a program to achieve health equity. Health Aff (Millwood). 2017;36:1133-1139. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. World Health Organization. The World Health Report 2008: Primary Health Care (Now More Than Ever). Geneva, Switzerland: World Health Organization; 2008. [Google Scholar]

- 36. Dehnavieh R, Noorihekmat S, Masoud A, et al. Evaluating the Tabriz Health Complex Model, lessons to learn. Iran J Epidemiol. 2018;13:59-70. [Google Scholar]

- 37. Reeve C, Humphreys J, Wakerman J, Carter M, Carroll V, Reeve D. Strengthening primary health care: achieving health gains in a remote region of Australia. Med J Aust. 2015;202:483-487. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]