Highlights

We review prior research on race and the criminal justice system response to sexual assault.

Studies varied in race focus, theory use, sample composition, and how and whose race was measured.

Seemingly disparate findings were not‐so‐disparate after considering individual study features.

Race‐based oppression, like all forms of oppression, is cumulative and must be contextualized.

Researchers yield a great power, and responsibility, in deciding how to include race in research.

Keywords: Sexual assault, Rape, Race, Criminal justice system, Police, Review

Abstract

Prior research has consistently documented that the vast majority of sexual assault cases do not progress through the criminal justice system. However, there is less agreement in prior work on how race influences case progression, resulting in a literature frequently described as “inconsistent.” This systematic review examines all prior research that has included race as an independent variable in predicting the criminal justice system response to sexual assault (N = 34) in an effort to provide insight into seemingly disparate findings. We assess each study for the degree to which race was a focal point of interest, if and what theory was used to inform the investigation of race, how samples were drawn, and how and whose race was measured. Results illustrate that findings in prior research are not inconsistent, but rather unite to tell a nuanced story of the role of race in the criminal justice system response to sexual assault. The review demonstrates how decisions made by researchers throughout the research process can have significant impacts on reported findings, and how such findings may be used to influence policy and practice.

Introduction

In 2006, Tarana Burke coined the phrase, “Me Too,” as a means to let survivors of sexual assault (SA), particularly women and girls of color, know that they are not alone; and that in working together, they may find hope, support, and inspiration (Ohlheiser, 2017). About a decade letter, #MeToo emerged as a viral awareness campaign, with millions taking to Facebook, Twitter, and other venues to share their experiences of sexual violence and to join in community with one another. The “Me Too” conversation reemerged and continued amid a backdrop of reports of SA at the hands of many prominent figures (Johnson & Hawbaker, 2019); the Larry Nassar sexual abuse investigations (Hauser & Astor, 2018); the discovery and documentation of hundreds of thousands of untested SA kits nationwide (Campbell, Feeney, Fehler‐Cabral, Shaw, & Horsford, 2017; Reilly, 2015); the election and inauguration of President Trump and the worldwide Women's March in response to it (Smith‐Spark, 2017); and the nomination, Senate Judiciary Committee's hearing on SA reports against, and subsequent swearing in of Supreme Court Justice Kavanaugh (Stolberg, 2018). While the public discourse on sexual violence surged, so did a parallel, though largely separate conversation on race and the criminal justice system (CJS). The acquittal of George Zimmerman for the killing of Trayvon Martin (L. Alvarez & Buckley, 2013); the killings of Eric Garner, Mike Brown, Philando Castile, and many others by police officers on duty (Hafner, 2018); the continued mass incarceration of African American men and women (Tucker, 2017); and the mobilization of the Black Lives Matter movement (Thomas & Zuckerman, 2018) have renewed a focus on the experiences and interactions of individuals of color and the CJS, with a particular focus on the extent to which such experiences are defined by systemic racism.

Though recent public discourse on race and the CJS largely occurs in separate, distinct spaces from discussions on sexual violence, much research has examined their intersection. A sizable body of literature has investigated the quite complex CJS response to SA, and how cases move through it (see Lonsway & Archambault, 2012; Spohn & Tellis, 2012 for reviews). For a SA case to progress in the CJS, it must first be reported to police. Police may then conduct an investigation and refer the case to the prosecutor's office for the consideration of charges against an identified suspect. In some jurisdictions, interactions between police investigators and the prosecutor's office happen earlier on in the process, as some investigators routinely screen all cases with the prosecutor's office shortly after the assault is reported. The police frequently also interface with the medical system and crime laboratory during their investigation. Police may assist the victim in accessing a medical forensic exam, and transport completed SA evidence collection kits from the medical facility where they are completed to crime laboratories where they may be analyzed and used in the course of the criminal investigation and potential future prosecution. Once a case is referred to the prosecutor's office, the prosecutor may choose to file charges. The charges may be dismissed prior to prosecution, the defendant may plead guilty, or the case may go to trial. If the case goes to trial, it may result in a guilty verdict, or an acquittal. If the defendant is convicted via a guilty plea or conviction at trial, the defendant may be incarcerated, or receive some other sentence (e.g., parole, fine). Prior research on the CJS response to SA has documented how fewer and fewer cases reach each juncture in this system. Lonsway and Archambault (2012) call this the “funnel of attrition;” for every 100 forcible rapes committed, an estimated 5–20 are reported to police, 0.4–5.4 are prosecuted, 0.2–5.2 result in a conviction, and 0.2–2.8 result in incarceration of the offender (p. 158).

Beyond documenting high rates of attrition among SA cases in the CJS generally, prior research has also attempted to understand what factors distinguish those cases that do progress from those that get left behind. For example, studies have examined what predicts some cases resulting in an arrest, while others do not (e.g., Addington & Rennison, 2008); some cases being prosecuted, while others are not (e.g., see Campbell, Patterson, Bybee, & Dworkin, 2009); some cases resulting in a conviction, while others end in an acquittal or dismissal (e.g., Maxwell, Robinson, & Post, 2003); and how convicted offenders are sentenced (e.g., Curry, 2010). Race is frequently included as one such factor. However, while there is general agreement that the vast majority of cases do not progress through the CJS, there is less agreement across studies in how race influences case progression. Prior research on the influence of race on the CJS response to SA has been described as “mixed” (Shaw, Campbell, & Cain, 2016, p. 458), “inconsistent” (Spohn & Tellis, 2012, p. 176), and containing “contradictions” (Maxwell et al., 2003, p. 524). Thus, the purpose of this review is to examine prior research on race and the CJS response to SA so as to try and resolve seeming disparities in prior work and provide empirical information that may be used to catalyze and inform public discourse focused on the intersection of race, gender, sexual violence, and the CJS response to it. Through a thorough examination of how race is conceptualized, theorized, measured, and discussed, we hope to help tell a more cohesive, nuanced narrative that can contribute to this ongoing public discussion and perhaps help inform change initiatives therein.

Method

Literature Search

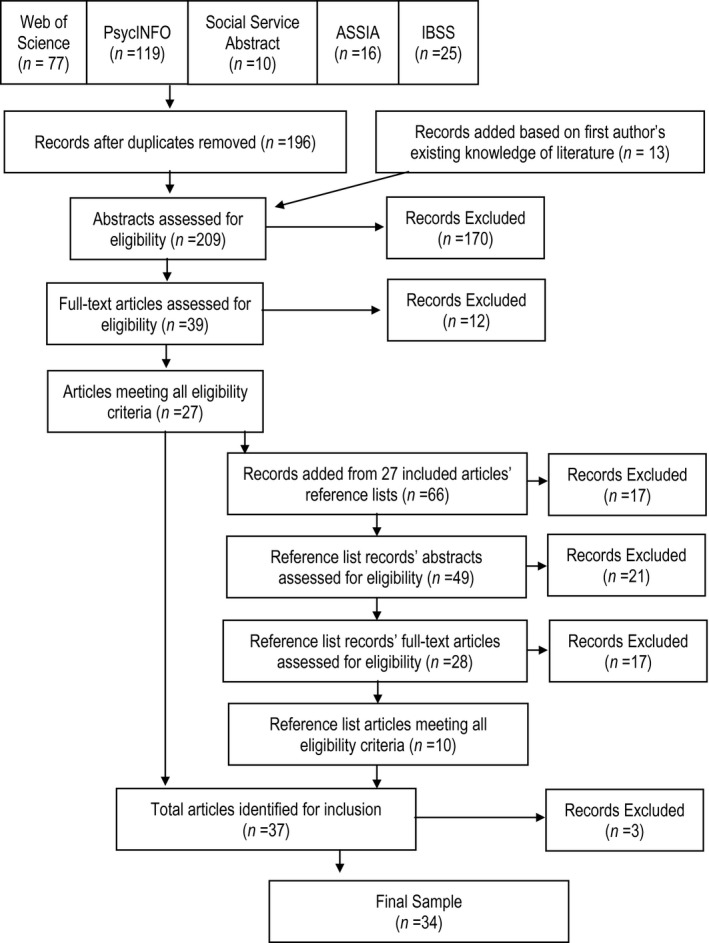

The empirical studies included in this review were identified through library and online databases, as well as checking the reference lists of identified articles for additional relevant studies (see Booth, Papaioannou, & Sutton, 2012). Specifically, we searched Web of Science, PsycINFO, Social Service Abstracts, Applied Social Sciences Index and Abstracts (ASSIA), and International Bibliography of the Social Sciences (IBSS) using the key word “race” in combination with “rape” or “sexual assault,” and “police,” “prosecution,” “law enforcement,” or “criminal justice.” After removing duplicates across databases, our initial search yielded 196 records. Based on the first author's existing knowledge of the literature on the CJS response to SA, the abstracts of an additional thirteen records were added.

Selection and Data Abstraction of Included Articles

Each of the authors reviewed independently the abstracts for the 209 records to assess if they should be included in the review (see Fig. 1). To be included, the abstract must have described a study that met the following inclusion criteria: an original empirical article published in a peer‐reviewed journal through 2016, that used quantitative methods to examine factors that predict some aspect of the CJS response to SA, with actual data on the CJS response (e.g., not surveys of individuals’ perceptions, review of vignettes, mock juror reactions, etc.). The authors then met to review their independent assessments, and discussed any discrepancies until consensus was reached. We identified 39 records for potential inclusion (28 from the initial database search and 11 from the first author's supplementary list of articles).

Figure 1.

Flowchart of search results

The full‐text articles for the 39 records were reviewed in their entirety to ensure each study met the above inclusion criteria. In addition, each article needed to include race (of the victim, the suspect, or both) as a predictor variable in the quantitative analysis and be written in English. Following independent assessment and group discussion, we identified 27 articles for inclusion in this review. A check of the references provided in each of these 27 articles identified an additional 66 references for potential inclusion. We followed a similar process as described above, reviewing the abstracts for each of these 66 references, then the complete articles to ensure race was included as an independent variable. We identified ten additional articles for inclusion through these means, yielding 37 articles for inclusion in this review. Once coding was underway, however, we excluded one article due to multiple errors identified in the manuscript, some pertaining directly to the purpose of this review. Two additional articles were removed as they only provided descriptive statistics; no inferential tests were performed.

The first author reviewed and coded the final sample of N = 34 studies for the extent to which race was a focal point of interest (i.e., race was a focal variable of interest, one of a battery of variables of interest, or treated as a control variable); extent to which theory was used to inform the investigation of race (i.e., the specific theory or theories used and provided explanations for theory selection); sample selection and composition (i.e., inclusion criteria, sample size, sample locales, samples’ racial composition, and data sources); how race was coded (i.e., race of the victim, perpetrator, or both; and race categories used); and outcomes of interest and research findings (i.e., the dependent variables explored and reported findings).

Results

Table 1 describes the outcome of interest; sample; if race was a focal, control, or variable of interest; if and what theory was used to guide the examination of race; race measures; and race findings for each of the included articles. Included studies were published between 1961 (Bullock, 1961) and 2016 (Shaw et al., 2016), relying upon data and administrative records collected as early as 1945 (Wolfgang & Riedel, 1975), and as recently as 2009 (Shaw et al., 2016). All studies were conducted in the United States. Unless otherwise noted, in discussing each article, we use the same language presented in the original article for terms related to race (e.g., “Victims of Color,” “non‐White victims,” “Negroes,” etc.). We maintain the specific language and terms used by the authors in their original manuscripts as the language we use to discuss race provides insight into how we consider and socially construct race.

Table 1.

Description of included articles

| Author (year) | Outcome of interest | Samplea | Racial composition of sampleb | Theory to examine race | Race measurec | Race findings |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Addington and Rennison (2008)d | Rape clearance: Arrest or clearance by exceptional means | 22,876 female rape victims in the FBI Uniform Crime Reporting (UCR) Program's National Incident Reporting System (NIBRS) data from 2002 |

Victim 76.9% White 20% Non‐White 3.1% Unknown/missing Suspect 60.5% White 28.5% Non‐White 11.1% Unknown/missing |

None |

Victim Non‐Hispanic White or Notb Suspect White or Non‐White |

Cases with Non‐Hispanic White victims had a lower odds (OR = 0.88) of being cleared by arrest or exceptional means. Cases with White suspects had a higher odds (OR = 1.13) of being cleared by arrest or exceptional means. |

| Alvarez and Bachman (1996)e | Sentence length: Number of years. Life and death sentences recoded to reflect 15 and 20 years above the longest sentence received | 2,204 active inmates aged 16–72 years old, assumed to be representative of average Arizona state correctional population in 1990 |

Suspect 95% Caucasian 5% American Indian Other racial/ethnic groups excluded |

ict Theory |

Suspect Caucasian or American Indian Other racial/ethnic groups excluded |

Caucasians had an average sentence of 26 years compared to 19 years for American Indians. This was not statistically significant. |

| Beichner and Spohn (2012)d | Prosecutor's charging decision: Charges filed vs. no charges filed | 666 reported rape cases from police agencies in Miami, Kansas City, and Philadelphia that involve female victims at least 12 years old with a corresponding arrest and referral to the prosecutor's office from 1996 to 1998 |

Victim 65.6% non‐White 34.4% White Suspect 76.8% non‐White 23.3% White |

None explicitly identified for race examination. Focal Concerns Theory used for overall investigation. |

Victim White or non‐White Suspect White or non‐White |

White victims were more likely to have charges filed in cases of aggravated rape (i.e., suspect and victim were stranger, suspect used gun or knife during assault; or victim suffered collateral injuries). No effect of victim race or suspect race in simple rapes (i.e., no aggravating factors). |

| Bouffard (2000)e |

Founding: Founded vs. unfounded by police Case closure: Among founded cases, case closure category |

326 felony SA cases drawn from the investigative files of one urban/suburban agency in 1995 |

Victim 76.6% African‐American 18.3% White 6.1% Other Suspect 85.1% African‐American 9.8% White 5.1% Other |

Theory of Law |

Victim White or Notb Suspect African‐American or Notb Dyad White victim and African‐American suspect or Notb |

No effect of victim race, suspect race, or race dyad. |

| Bradmiller and Walters (1985)e | Severity of charge: Rape (more severe charge) vs. nonrape (less severe charge) | 89 cases of charged SA being evaluated by the Court Psychiatric Center in Hamilton County, OH from January 1973‐May 1979 that involved offenders with no prior conviction for SA; included charges that were still considered crimes at the time of the study (1985); did not have a more severe charge (e.g., aggravated murder); and were not missing data on variables of interest (e.g., force used) |

Suspect 60% Black 40% White |

None |

Suspect Black or white |

Race accounted for 5% of the variance in the dependent variable—severity of charge. Given similar crimes, black offenders were more likely to be charged with more serious crimes (i.e., rape as opposed to nonrape). |

| Briggs and Opsal (2012)e | Arrest: Suspect arrested vs. no suspect arrested | 226,496 cases reported to FBI UCR NIBRS by 1,490 police departments in 30 states for offences that occurred in 2008; SA cases are one type of offense included |

Victim 68.1% white non‐Hispanic 20.6% black non‐Hispanic 11% white Hispanic 0.3% black Hispanic Other racial/ethnic groups excluded |

Theory of Law Procedural Justice |

Victim White or black Hispanic or Non‐Hispanic Other racial/ethnic groups excluded |

Cases involving Hispanic victims were more likely to conclude in arrest than non‐Hispanic victims, though this relationship was not statistically significant. |

| Bullock (1961)e | Sentence length: short (less than 10 years) vs. long (ten years and longer) | 3,644 inmates committed for burglary, rape, and murder to the Texas State Prison at Huntsville in 1958 |

Suspect 68.2% white 31.% Negro Other racial/ethnic groups excluded |

None officially named. Theory of Law concepts presented. |

Suspect White or Negro Other racial/ethnic groups excluded |

Negro offenders are more likely to receive short sentences, even after considering geographic region, plea bargains, and number of previous felony convictions. |

| Campbell et al. (2009)f | Case outcome: Not referred by the police for prosecution vs. referred but not charged vs. charged but later dropped or acquitted vs. conviction at trial or guilty plea | 137 adult SA cases reported to police and treated by a SA nurse examiner program in a geographically diverse county in the Midwest from 1999 to 2005 |

Victim 86% Caucasian 14% racial/ethnic minority |

None |

Victim Caucasian or racial/ethnic minority |

No effect of victim race. |

| Chandler and Torney (1981)e | Case outcome: charged vs. released/dropped. If charged, plea bargain vs. trial | 408 SA victims treated by the Sex Abuse Treatment Center of a large, urban hospital between October 1976 and September 1978 | Not provided | Conflict Theory |

Victim Caucasian or non‐Caucasian or Hawaiian Suspect Caucasian or non‐Caucasian or Hawaiian Dyad Both Caucasian or both non‐Caucasian or Defendant non‐Caucasian/Victim Caucasian or Defendant Caucasian/Victim non‐Caucasian |

Caucasian suspects are underrepresented and Hawaiian suspects are overrepresented among those indicted. Caucasian victims are overrepresented among those seeing their assailant indicted. Cases with Caucasian victims and Non‐Caucasian suspects are more likely to result in a charge than to have the suspect released. Caucasian defendants are overrepresented in the plea bargaining process and Hawaiian defendants are overrepresented among those going to trial. |

| Curry (2010)e | Sentence length: Number of years | 241 randomly selected male offenders who are at least 18 years old and convicted of felony SA against a female in the seven largest counties in Texas between January and September 1991 |

Victim 43% White 31% Black 26% Hispanic Suspect 41% Black 31% White 28% Hispanic Other racial/ethnic groups excluded |

Conflict Theory Focal Concerns Theory Blameworthiness Attribution Bounded Rationality |

Victim Non‐Hispanic White or non‐Hispanic Black or Hispanic Suspect Non‐Hispanic White or non‐Hispanic Black or Hispanic Dyad Offender Black/Victim White or Offender Hispanic/Victim White or Offender White/Victim White or Offender or Offender any race/Victim Black or Hispanic Other racial/ethnic groups excluded |

Hispanic offenders receive shorter sentences than White offenders. No effect of victim race or race dyad. |

| Frazier and Haney (1996)f |

Suspect interview: Suspect questioned vs. no suspect questioned Prosecutor's charging decision: Charges filed vs. no charges filed |

569 criminal sexual conduct cases involving females victims over the age of 15 reported to a Midwestern metropolitan police department in 1991 |

Victim 55% White 31% Black 10% Native‐American 3% Other or Unknown |

None |

Victim Caucasian or Notb Suspect Caucasian or Notb |

No effect of victim race or suspect race. |

| Gray‐Eurom et al. (2002)f |

Conviction: Guilty verdict vs. not guilty verdict Prosecutor's charging decision: Charges filed vs. no charges filed |

355 SA patients who received a forensic exam at the Adult and Adolescent SA Program in Duval County, Florida between October 1993 and September 1995; reported to police; had a suspect identified; and a known legal conclusion |

Victim 51% black 47% white 2% other minorities Suspect 32% black 10% white 58% examiner did not record offender race |

None |

Victim White or Notb |

Cases with white victims trended toward conviction, though the relationship was not statistically significant. Cases with victims who were not white trended toward being dropped, though the relationship was not statistically significant. |

| Holleran et al. (2010)d | Prosecutor's charging decision: Charges filed vs. no charges filed | 368 reported rape cases from police agencies in Kansas City and Philadelphia involving male offenders, female victims at least 12 years old, an initial police charge of forcible rape, and a corresponding arrest and referral to the prosecutor's office from 1996 to 1998 | Not provided | Focal Concerns Theory |

Victim White or Black Suspect White or Black Other racial/ethnic groups excluded |

No effect of victim race or suspect race. |

| Horney and Spohn (1996)d |

Suspect identification: Suspect identified vs. no suspect identified Case outcome: closed by police vs. referred to prosecutor but declined vs. accepted by prosecutor but later dismissed vs. prosecuted and not‐guilty verdict; vs. prosecuted and guilty |

259 reported criminal sexual conduct cases randomly selected from the daily complaint log of the Detroit Police Department's Sex Crimes Unit in 1989 with a female complainant at least 16 years old, initial charges of first or third‐degree criminal sexual conduct, and not unfounded. |

Victim 88.8% black 11.2% white Suspect 93.8% black 6.2% white |

None |

Victim Black or white Suspect Black or white |

Cases with black victims are more likely to have a suspect identified. No effect of victim or suspect race on case outcome. |

| Kerstetter (1990)f |

Founding: Founded vs. unfounded by police Prosecutor's charging decision: Charges filed vs. no charges filed Victim decline prosecution: Victim declined prosecution vs. did not decline Suspect line‐up: suspect line‐up completed vs. no suspect line‐up Arrest: Suspect arrested vs. no suspect arrested |

1,530 founded rape cases reported to and founded by the Chicago police department in 1979 and 671 randomly selected cases from all SA complaints made by women to the Chicago police department in 1981 | Not provided | Conflict Theory |

Victim Not provided Suspect Not provided Dyad Not provided |

No effect of victim, suspect, or dyad race. |

| Kingsnorth et al. (1998)e |

Prosecutor's charging decision: Case charged and moves forward to prosecution vs. rejected or charges or dismissed Plea: Went to trial vs. guilty plea Incarceration Type: Jail vs. prison Sentence length: Number of years |

365 rape cases forwarded to the district attorney's office by Sacramento police and county sheriff's department from 1992 to 1994 |

Dyad 34.5% White suspect/White victim 32.1% Black suspect/Black victim 21.4% Black suspect/White victim 12.1% Hispanic suspect/White victim Other racial/ethnic combinations excluded |

Conflict Theory Structural Contexts Sexual Stratification Hypothesis |

Dyad White suspect/White victim or Black suspect/White victim or Hispanic suspect/White victim or Black suspect/Black victim Other racial/ethnic combinations excluded |

Cases with White suspects/White victims are arrested, on average, on a greater number of counts than cases with Black suspects/White victims and cases with Hispanic suspects/White victims. No effect of race dyad on prosecutor's charging decision, plea, incarceration type, or sentence length. |

| LaFree (1980a)e |

Arrest: Suspect arrested vs. no suspect arrested Seriousness of crime: Mean prison term imposed by statute if convicted Felony charge: felony charges filed vs. no felony charges filed Dismissal: Prosecutor's decision to dismiss charges vs. pursue charges Plea: Went to trial vs. guilty plea Conviction: convicted by a guilty plea or guilty verdict at trial vs. no conviction Sentence type: Executed vs. non‐executed (i.e., combination of probation, suspended sentence, and fine) Incarceration Type: For executed sentences, incarceration at state penitentiary or elsewhere (less serious) Sentence length: Number of years |

870 suspects forcible sex offenses of female victims reported to police in a large Midwestern city between January 1970 and December 1975 |

Dyad 44.7% black suspect/black victim 32.3% white suspect/white victim 23.0% black suspect/white victim |

Conflict Theory Sexual Stratification Hypothesis |

Dyad black suspect/black victim or white suspect/white victim or black suspect/white victim |

From case report through final sentencing, the percentage of black intraracial assaults steadily declined, the percentage of white intraracial assaults remained relatively constant, and the percentage of cases involving black suspects/white victims steadily increased. Cases with black suspects/white victims were more likely to receive more serious charges; be filed as felonies; result in executed sentences; result in incarceration in the state penitentiary; and result in longer sentences. No effect of race dyad on arrest, dismissal, plea, or conviction. |

| LaFree (1980b)f |

Plea: Went to trial vs. guilty plea Guilty verdict: Among those who go to trial, guilty verdict vs. not guilty verdict Conviction: convicted by a guilty plea or guilty verdict at trial vs. no conviction |

124 forcible rape cases involving female victims adjudicated by the courts of a large Midwestern city in 1970, 1973, and 1975 |

Victim 59.7% white 40.3% black Suspect 67.7% black 32.3% white Dyad 40.3% black suspect/black victim 31.5% white suspect/white victim 28.2% black suspect/white victim Two victims and one suspect were non‐white other than black. They were grouped in with black. One case involved white suspect/black victim. This case was added to black suspect/black victim. |

None explicitly identified for race examination. Conflict Theory and Labeling Theory for overall investigation. |

Victim white or black Suspect white or black Dyad black suspect/black victim white suspect/white victim black suspect/white victim Two victims and one suspect were non‐white other than black. They were grouped in with black. One case involved white suspect/black victim. This case was added to black suspect/black victim. |

Cases with black suspects were more likely to go to trial than result in plea bargain. Cases with black victims were less likely to result in a conviction via a plea bargain or a guilty verdict at trial. |

| LaFree (1981)f |

Arrest: Suspect arrested vs. no suspect arrested Seriousness of crime: Mean prison term imposed by statute if convicted Felony charge: felony charges filed vs. no felony charges filed |

905 forcible sex offenses with female victims reported to police in a large Midwestern city in 1970, 1973, and 1975 |

Victim 54.6% white 45.4% black Suspect 67% black 33% white Dyad 44.1% black suspect/black victim 33% white suspect/white victim 22.9% black suspect/white victim Non‐white suspects and victims who were not black (less than 1%) were grouped in with black. Cases with white suspects/black victims (1.2%) excluded. |

None |

Victim white or black Suspect white or black Dyad black suspect/black victim or white suspect/white victim or black suspect/white victim Non‐white suspects and victims who were not black (less than 1%) were grouped in with black. Cases with white suspects/black victims (1.2%) excluded. |

Once a SA unit was implemented, black intraracial cases were significantly less likely to have an arrest than White intraracial cases. Cases with black suspects/white victims had more serious charges and were more likely to be charged as felonies. |

| Maxwell et al. (2003)e |

Pretrial release: Defendant released vs. detained Prosecutor's charging decision: Arrest charge maintained or elevated by prosecutor vs. downgraded to a lesser offense Conviction: By a guilty plea or guilty verdict at trial vs. not guilty at trial or dismissal Incarceration: Incarceration vs. no incarceration Incarceration Type: Prison vs. jail, probation, or other type of sentence Sentence Length: Expected maximum number of months |

4,050 arrested defendants associated with filed felony SA cases selected from a stratified sample of the Nation's 75 most populous counties in the National Pretrial Reporting Program (nPRP), also known as the State Court Processing Statistics (SCPS), in 1990, 1992, 1994, and 1996 |

Suspects 49% African‐American 38% White 10% Hispanic 3% Asian |

Consensus Theory Conflict Theory Lotz & Hewitt's Five Models |

Suspect White or African‐American or Hispanic or Asian and other races |

No effect of suspect race on pretrial release, prosecutor's charging decision, incarceration. African‐American and Hispanic suspects were significantly less likely to be found guilty than White suspects. Asian suspects are somewhat more likely to be found guilty than White suspects, though this does not reach statistical significance. African‐American and Hispanic suspects were significantly less likely to be sentenced to prison than White suspects. White suspects convicted of SA receive significantly longer sentences than all other groups, regardless of their prior criminal history or their current criminal justice status. |

| Roberts (2008)f | Clearance by arrest: Case cleared by arrest vs. not cleared by arrest | 11,215 forcible rape incidents reported in the 2000 FBI UCR NIBRS from 10 cities with populations between 25,000 and 660,000 across seventeen states |

Victim 61.87% White 34.28% non‐White 3.85% Missing |

Conflict Theory Theory of Law |

Victim White or non‐White |

Cases with non‐White victims were more likely to be cleared by arrest. |

| Shaw and Campbell (2013)f | Rape Kit Submission: Rape kit was submitted to the crime lab vs. rape kit not submitted | 393 reported SA cases involving 13–17 year old victims treated by two SA nurse examiner programs in two Midwestern communities from 1998 to 2007 |

Victim 80.3% White 14.9% African‐ American 3.0% Bi/Multiracial 1.0% Latino/a 0.8% Other |

None |

Victim White or non‐White |

Cases with non‐White victims were nearly twice as likely to have their kit submitted. |

| Shaw et al. (2016)e |

Investigative steps: Number of investigative steps completed Arrest: Suspect arrested vs. no suspect arrested Referral: Case referred to the prosecutor for the consideration of charges vs. no referral to the prosecutor |

248 reported SA cases corresponding to randomly selected, largely unsubmitted SA kits that accumulated in police property in a large, urban, predominately Black/African‐American, Midwestern City from 1980 to 2009 |

Victim 86.3% Black 13.3% White 0.4% Other Suspect 91.9% Black 5.6% White 0.4% Other 2.0% Missing |

Social Dominance Theory |

Victim White or of color Suspect White or of color All but one victim and one suspect of color were Black/African‐American. |

Victims of color were more likely to be deemed uncooperative, without a phone/means of contact, without information, or weak, which then meant a case was likely to have fewer investigate steps completed and was less likely to have an arrest and referral to the prosecutor's office. No effect of suspect race. |

| Spears and Spohn (1997)d | Prosecutor's charging decision: Charges filed vs. no charges filed | 321 SA cases presented to the warrant section of the county prosecutor's office in Detroit in 1989 |

Victim 82.5% black 17.5% white Suspect 85.6% black 14.4% white |

None |

Victim white or black Suspect white or black |

No effect of victim or suspect race. |

| Spohn and Cederblom (1991)e |

Sentence Type: Sent to prison vs. not sent to prison Sentence length: Of those sentenced to prison, number of days for expected minimum sentence |

363 rape and 299 other sexual offense cases with a male offender that resulted in a conviction and sentencing of the offender from 1976 to 1978 based on Detroit's Recorder's Court records | Not provided for subsample of rape and other sexual offense cases. Entire sample, which included cases with offenders convicted of 11 different felony crimes, was 84.2% black and 15.8% white. | Liberation Hypothesis |

Suspect white or black |

Cases with black suspects were more likely to result in incarceration than cases with white suspects when it was a stranger assault. Race did not have an effect on incarceration for acquaintance assault. No effect of suspect race on sentencing length. |

| Spohn and Holleran (2001)f | Prosecutor's charging decision: Charges filed vs. no charges filed | 526 reported SA cases involving female victims 12 years and older, male offenders, and that were referred to the prosecutor in Kansas City and Philadelphia from 1996 to 1998 |

Stranger Rapes 41% white victims 21% white suspects Acquaintance Rapes 31% white victims 24% white suspects Partner Rapes 32% white victims 23% white suspects |

None |

Victim white or Notb Suspect white or Notb |

Cases with white victims were 4.5 times more likely to be charged when it was a stranger assault. Victim race did not have an effect on charging in non‐stranger cases. |

| Spohn and Horney (1993)ffor victim; C for suspect |

Dismissal: Prosecutor's decision to dismiss charges vs. pursue charges Plea: Went to trial vs. plea to a lesser charge Conviction: By a guilty plea or guilty verdict at trial vs. not guilty at trial or dismissal Incarceration: Incarceration vs. no incarceration |

812 rape cases charged by the prosecutor in Detroit from 1970 to 1984 |

Victim 73.0% black 27.0% white Suspect 87.9% black 11.2% white |

None |

Victim white or black Suspect white or black |

Following rape law reform in 1975, cases with black victims were less likely to have charges dismissed or result in a plea bargain. No effect of suspect race on dismissal or plea. Following rape law reform in 1975, cases with black suspects were less likely to result in a conviction. No effect of victim race on conviction. No effect of victim or suspect race on incarceration. |

| Spohn and Spears (1996)e |

Dismissal: Prosecutor's decision to dismiss charges vs. pursue charges Conviction: By a guilty plea or guilty verdict at trial vs. not guilty at trial or dismissal Incarceration: Incarceration vs. no incarceration Sentence Length: Among those incarcerated, maximum sentence imposed |

1,152 SA cases involving female victims and male perpetrators charged by the prosecutor in Detroit from 1970 to 1984 |

Dyad 74% black suspect/black victim 13.3% black suspect/white victim 12.7% white suspect/white victim |

Sexual Stratification Hypothesis |

Dyad black suspect/black victim or black suspect/white victim or white suspect/white victim |

Cases with black suspects/white victims were significantly more likely to be dismissed, though when convicted, resulted in longer sentences than other dyads. Cases with black suspects/white victims were less likely to be convicted than cases with white suspects/white victims. No effect of dyad race on incarceration. Among intraracial black dyads, stranger cases were significantly less likely to have charges dismissed, more likely to result in incarceration, and resulted in longer sentences than cases of acquaintance assault. |

| Spohn et al. (2001)f | Prosecutor's charging decision: Charges filed vs. no charges filed | 140 rape cases involving victims 12 years old and up that were cleared by arrest in 1997 from the sex crimes bureau of the Miami‐Dade police department |

Victim 58.1% black 31.3% white 10.9% Hispanic/other Suspect 64.9% black 18.9% white 16.2% Hispanic |

Focal Concerns Theory |

Victim white or Notb Suspect white or Notb |

Charges were more frequently rejected with non‐white victims and suspects, though this was not statistically significant. |

| Spohn et al. (2014)f | Founding: Founded vs. unfounded by police | 393 SA cases involving female complainants 12 years and up reported to the Los Angeles Police Department in 2008 |

Victim 47.6% Hispanic 28% white 19.1% black |

None explicitly identified for race examination. Theory of Law and Focal Concerns Theory for overall investigation. |

Victim white or black or Hispanic or Other |

No effect of victim race. |

| Tellis and Spohn (2008)e |

Founding: Founded vs. unfounded by police Prosecutor's charging decision: Charges filed vs. no charges filed Victim decline prosecution: Victim declined prosecution vs. did not decline |

1,452 SA cases with victims 14 years old and up reported to the Sex Crimes Unit of the San Diego Police Department from 1991 to 2002 |

Dyad 35% White suspect/White victim 18% Black suspect/Black victim 15% Black suspect/White victim 15% Hispanic suspect/Hispanic victim 10% Hispanic suspect/White victim 4% White suspect/Hispanic victim 3% Black suspect/Hispanic victim Other racial/ethnic combinations excluded |

Sexual Stratification Hypothesis Liberation Hypothesis |

Dyad Black suspect/Black victim or Black suspect/White victim or Black suspect/Hispanic victim or Hispanic suspect/Hispanic victim or Hispanic suspect/White victim or White suspect/White victim or White suspect/Hispanic victim Other racial/ethnic combinations excluded |

Cases with intraracial White dyads were more likely to be unfounded than cases with Hispanic suspects/White victims. No dyad race effect on prosecutor's charging decision or victim declining prosecution. |

| Walsh (1987)e |

Sentence Type: Probation vs. prison Sentence severity: Scale with score determined based on points allocated for each year of probation (10), day in county jail (1), $25 fine (1), two days in work release (1), and day in state prison (1.1). |

417 defendants sentenced on felony SA charges in a metropolitan Ohio county from 1978 to 1983 |

Suspects 58% white 42% black |

Sexual Stratification Hypothesis |

Victim white or black Suspect white or black Dyad white suspect/white victim or black suspect/black victim or black suspect/white victim Nine cases of white suspect/black victim were excluded. |

Black suspects/white victims are four times more likely to be imprisoned as black suspects/black victims and twice as likely as white suspects/white victims. black intraracial dyads received significantly more lenient sentences than white intraracial dyads even though black intraracial dyads committed more serious crimes and had more significant prior records. black suspects who assault white victims, regardless of offender/victim relationship, received significantly harsher penalties than black suspects who assault black victims. Penalties are even more lenient for black suspects/black victims when the suspect and victim are acquainted. |

| Wolfgang and Riedel (1973)e | Sentence type: death sentence vs. other sentence | 1,265 rape convictions from 1945 to 1965 in 230 counties in eleven southern and border states in which rape is a capital offense |

Suspect 65.1% black 34.9% white |

None |

Suspect black or white Dyad black suspect/white victim or Notb |

After accounting for two dozen possible nonracial variables, black defendants were sentenced to death at a rate seven times that of white defendants; black defendants with white victims were sentenced to death eighteen times more frequently than any other race dyad. |

| Wolfgang and Riedel (1975)e | Sentence type: death sentence vs. other sentence | 361 rape convictions from 1945 to 1965 in Georgia | Not provided | None |

Victim Not provided Suspect Not Provided Dyad black suspect/white victim or Notb |

Black suspect/white victim cases are most likely to result in a death sentence. No effect of victim or suspect race alone. |

SA, sexual assault.

Cases, victims, and suspects from crimes other than rape or SA were included in some study samples. The sample descriptions provided here are specific to those samples/subsamples for rape and SA. If a study included cases, victims, or suspects from crimes other than rape or SA and did not provide specific information on the subsample for rape and SA only, it is noted.

These variables were dichotomous. “Or Not” is not language used by the authors/researchers of each manuscript; it is our language to indicate a dichotomous variable.

In some studies, the racial composition information and race measures provided do not include exhaustive categories for all races (e.g., “black” and “white” are the only race categories reported or measured). When authors/researchers explained how other races were handled, it is noted. If this is not noted, that means it was not clear if other races did not appear in the sample, or if other races were intentionally excluded from the sample.

Race was a control variable.

Race was a focal point of interest.

Race was one of many variables of interest.

Race as a Focal Point of Interest

Of the thirty‐four articles reviewed, half (n = 17) included race as a focal point of interest in the investigation. For example, articles examined the potential discriminatory application of the law for “American Indian” compared to “Caucasian” perpetrators (Alvarez & Bachman, 1996); the main effect of victim “race/ethnicity” on sentencing outcomes (Curry, 2010); and the impact of “the racial composition of the victim‐defendant dyad” on police and prosecutor decision‐making (LaFree, 1980a). An additional twelve articles included race as one of many variables of interest, though not a focal point of the empirical investigation. The remaining five articles included race as a control. Some articles provided an explanation for this decision. For example, in examining SA case progression through the CJS, Horney and Spohn (1996) explain that while “the interaction of victim and offender race has been shown by some studies to be a significant determinant of case outcomes (LaFree, 1989; Walsh, 1987), [they] were not able to explore this interaction because 82% of the cases in this Detroit sample (90% of cases with suspects) were black‐on‐black offenses” (p. 141); thus, race was entered as a control. The majority of studies that included race as a focal point found at least one statistically significant race finding (n = 13; 76.5%), compared to about sixty percent of studies including race as a variable of interest (n = 7; 58.3%) or control (n = 3; 60%). In four studies, the original authors called attention to patterns in their data that suggested an influence of race, but that did not reach statistical significance. If these patterns are considered, 88.2% of studies that included race as a focal point (n = 15) report a relationship between race and the outcome variables; 75% of studies with race as a variable of interest (n = 9); and 60% of studies that included race as a control (n = 3).

Use of Theory to Explore Race

In half of the included articles (n = 17), the authors explicitly identified theory or conceptual models informing their empirical investigation of race. Another three articles discussed theory informing their overall investigation, though not specific to race; one article presented theoretical concepts that informed their investigation of race, but did not specifically name the theory as the theory was not yet developed; and the remaining thirteen articles provided no mention of theory in what guided their investigation. A total of thirteen different theories were used by authors to inform their empirical investigations. Regardless of if and how theory was used, about two‐thirds of the included articles had a least one statistically significant race finding (n = 11; 64.5% of articles with theory to guide race investigation; n = 2; 66.6% of articles with theory, though not explicitly tied to race investigation; and n = 9; 69.2% of articles with no mention of theory).

Conflict Theory

The theory most frequently used to inform empirical investigations of race was Conflict Theory (n = 8). Three articles used Conflict Theory alone, and five articles used Conflict Theory in combination with other theories or models (discussed below). One additional article used Conflict Theory to inform the overall investigation, though did not explicitly tie it to the inclusion of race in the study. In applying Conflict Theory to investigations of the CJS response to SA, authors explain how the very definition of what constitutes a crime, the extent to which a specific activity is treated as a serious crime, and how the CJS responds is determined by elites—powerful subgroups who occupy and want to maintain their favorable position in society (Maxwell et al., 2003). Crime and criminal justice processing is defined and designed in such a way to act as a means of control, help maintain existing power differentials, and ensure powerful subgroups retain their access to scarce resources while denying access to others (Chandler & Torney, 1981; Kerstetter, 1990; LaFree, 1980a). Race is one key determinant of the societal subgroup to which an individual belongs (Maxwell et al., 2003). In examining race and the CJS response to SA, we would expect to see “Black” crime victims devalued relative to “White” victims, leading to harsher penalties for those who harm “Whites” and more lenient sentences for those who harm “Blacks” (Curry, 2010). Not only are less powerful groups expected to be afforded less protection when they are victimized, but also to be more severely punished when suspected of perpetrating crimes (Maxwell et al., 2003).

Sexual Stratification Hypothesis

The second most frequently used theory was the Sexual Stratification Hypothesis (n = 5). Two articles used the Sexual Stratification Hypothesis on its own; one article used it in combination with Conflict Theory; one article in combination with the Liberation Hypothesis (discussed below); and another article used it in combination with both Conflict Theory and Structural Contexts (discussed below). The Sexual Stratification Hypothesis builds from Conflict Theory by conceptualizing sexual access as one of the scarce resources powerful subgroups intend to control (LaFree, 1980a). Individuals are classified into subgroups, or strata, based primarily on race and gender. Power differentials among these subgroups then determine sexual access to whom, by whom. The Sexual Stratification Hypothesis consists of a series of assumptions: (a) women are the valued and scarce property of the men of their own race; (b) “white” women are more valuable than “black” women; (c) the SA of a “white” woman by a “black” man is a dual threat, threatening both the “white” man's property rights and his dominant social position; (d) the SA of a “black” woman by any race does not threaten the status quo, and is thus less serious; and (e) “white” men have the power to sanction differently based on their social position and perceived threats to it (Walsh, 1987, p. 155). The Sexual Stratification Hypothesis requires an examination of the racial composition of the victim/perpetrator dyad, rather than examining victim or perpetrator race alone (Chandler & Torney, 1981; LaFree, 1980a; Tellis & Spohn, 2008; Walsh, 1987). In examining the CJS response to SA, Sexual Stratification Hypothesis suggests that “blacks who sexually assault whites” will receive the most robust CJS response (e.g., harsher sentences), “followed by whites who assault whites, blacks who assault blacks, and white (sic) who assault blacks” (Walsh, 1987, p. 155).

Black's Theory of Law

Three articles used Black's Theory of Law to inform the investigation of race in the CJS response to SA. One article relied solely on Black's Theory of Law; the second article used Black's Theory of Law in combination with Conflict Theory; and the third used Black's Theory of Law paired with Procedural Justice (see below). Spohn, White, and Tellis (2014) also used Black's Theory of Law, though for the overall investigation, not specifically for the examination of race. Interestingly, Bullock (1961) also referenced concepts and ideas from Black's Theory of Law, but did not explicitly name the theory, as the Theory of Law was not articulated by Black until 1976. Black's Theory of Law posits that the “application of law varies in its quantity,” with an arrest representing more law than no arrest or investigation at all, a criminal charge representing more law than no charges filed, and so on (Bouffard, 2000, p. 528). How much law is applied in a given situation is dependent on the social status of those involved (Bouffard, 2000; Spohn et al., 2014). “Upward” crimes are those committed by someone of lower social status against those of higher status; “downward” crimes are the opposite. Upward crimes threaten the status quo. Thus, they are considered more serious, and result in a greater quantity of law, whereas victims of downward crimes are devalued and receive less law (Bouffard, 2000; Briggs & Opsal, 2012; Roberts, 2008). In applying this theory to the CJS response to SA, we would expect a generally low level of law to be applied for all SAs, as the majority of SAs are “downward” crimes, with a male perpetrator and female victim (Bouffard, 2000). An even lower quantity of law would be expected for “ethnic minority victims” (Roberts, 2008).

Focal Concerns Theory

Three studies used Focal Concerns Theory to inform their empirical investigation of race. Two studies used Focal Concerns Theory alone, while the third used it in combination with Conflict Theory, Blameworthiness Attribution (see below), and Bounded Rationality (see below). Two additional articles used Focal Concerns Theory for the overall examination of the CJS response to SA, but did not link the theory explicitly to the investigation of race. Focal Concerns Theory states that judges’ sentencing decisions reflect a set of focal concerns; specifically, the blameworthiness or culpability of offenders, judges’ desire to protect communities from potentially dangerous individuals, and practical considerations (Holleran, Beichner, & Spohn, 2010; Spohn, Beichner, & Davis‐Frenzel, 2001). However, judges are not able to accurately determine just how dangerous an offender is. Thus, they rely on stereotypes and other attributions linked to an individual's group‐based identities, with some groups believed to be more dangerous or crime‐prone (Holleran et al., 2010; Spohn et al., 2001). This “perceptual shorthand” used by judges to make sentencing decisions has a far‐reaching impact (Steffensmeier, Ulmer, & Kramer, 1998, as cited in Spohn et al., 2001). CJS personnel who encounter offenders earlier on in the process develop a “downstream orientation,” in which police and prosecutors share judges' concerns, but also consider how a judge and jury will view the case, and the likelihood of a conviction (Frohmann, 1997, as cited in Spohn et al., 2001). Because “African American” individuals are frequently stereotyped as more dangerous and crime prone, CJS personnel are expected to be more likely to arrest, charge, and provide a harsher sentence for “African American” offenders as compared to “Whites” (Curry, 2010; see also Holleran et al., 2010; Spohn et al., 2001).

Liberation Hypothesis

Two studies used the Liberation Hypothesis to inform their investigation of race, with one relying on the Liberation Hypothesis alone and the other pairing it with the Sexual Stratification Hypothesis. According to the Liberation Hypothesis (Kalven & Zeisel, 1966, as cited in Spohn & Cederblom, 1991), when jurors are presented with weak, ambiguous, or contradictory evidence, they must find other sources of information to guide their decision‐making. Thus, they are ‘‘liberated’’ from the constraints imposed by the law and a pure fact‐finding mission, and instead turn to their own sentiments, values, and biases to inform their decisions (Spohn & Cederblom, 1991; Tellis & Spohn, 2008). Racial bias, then may influence how a juror decides a case, and even how CJS personnel respond to a case. Researchers who have used this theory explain that legally irrelevant characteristics, like the race of the suspect and victim, would be expected to influence CJS processing in “more ambiguous cases of simple rape” that involve a single known offender, no weapons and no injuries, as opposed to “aggravated rapes” that involve a stranger, multiple perpetrators, the use of a weapon, or injuries to the victim (Tellis & Spohn, 2008, p. 253; see also Spohn & Cederblom, 1991).

Social Dominance Theory

One article relied on Social Dominance Theory to inform its empirical investigation of race. Social Dominance Theory (Sidanius & Pratto, 2001, 2011) posits that all societies organize themselves into group‐based social hierarchies in which a few dominant groups possess greater social value (e.g., power, access to resources) than a many subordinate groups. Groups are defined by age, gender and other salient aspects of group‐based identity in a given context (e.g., race). Hierarchy‐enhancing and hierarchy‐attenuating forces at the individual, interpersonal, and systems level determine the extent to which groups are organized into hierarchies in a given a society at a given time. Legitimizing myths are one mechanism by which group‐based social hierarchies are created and reinforced. Legitimizing myths are shared ideologies that appeal to morality or intellect, and are used to legitimize or justify the disproportionate allocation of social value. In Social Dominance Theory, the CJS is considered “one of the most important hierarchy‐enhancing social institutions,” as individuals are treated differently within the CJS based on their group identity, with the intention of reinforcing hierarchical groups and power differentials (Sidanius, Liu, Shaw, & Pratto, 1994, p. 340, as cited by Shaw et al., 2016). In applying this theory to race and the CJS response to SA, “victims of color” would be expected to receive a less‐than‐thorough CJS response, with legitimizing myths operating to justify the disparity (Shaw et al., 2016).

Structural Contexts

One article drew upon the concept of Structural Contexts to complement the researchers’ primary applications of Conflict Theory and the Sexual Stratification Hypothesis. Kingsnorth, Lopez, Wentworth, and Cummings (1998) explain that there may not be systematic discrimination based on race and ethnicity in the CJS. Rather, Structural Contexts determine the extent of discrimination, with discrimination being limited to certain times, places, and offenses types within the CJS. One role of research is to identify the “structural and contextual conditions that are most likely to result in racial discrimination” (Hagan & Bumiller, 1983, p. 21, as cited in Kingsnorth et al., 1983).

Blameworthiness Attribution Theory

One article drew upon Blameworthiness Attribution Theory, as well as Bounded Rationality Theory (see below) to supplement the authors’ primary application of Conflict Theory and Focal Concerns Theory. In citing Baumer, Messner, and Felson (2000), Curry (2010) briefly explains that “non‐White” victims of violent crime may be seen as more responsible, or to blame, for their victimization due to stereotypes that “non‐White” individuals are more likely to be involved in violent crimes. As a result, offenders who target “non‐Whites” are seen as less blameworthy and receive more lenient punishments as compared to those who victimize “Whites.”

Bounded Rationality Theory

Curry (2010) also briefly mentioned Bounded Rationality Theory. In citing Albonetti (1991), Curry explains that there is prior support that judges seek to reduce uncertainty by relying on stereotypes that “Black” offenders have a greater criminal propensity and pose a greater risk to the community, thus they receive longer sentences. Curry (2010) points out that Bounded Rationality Theory, Blameworthiness Attribution Theory, Focal Concerns Theory, and Conflict Theory are all complementary to one another, thus their collective inclusion in Curry's investigation of race and the CJS response to SA. No other articles referenced Bounded Rationality Theory.

Consensus Theory

One article presented Consensus Theory alongside its presentation of Conflict Theory, and before introducing Lotz and Hewitt's Five Models (see below). Consensus Theory posits that society is stable and unified, law is neutral, there is consensus among most members of society as to how criminal behavior is defined, and the CJS responds equally and fairly to all groups and people, regardless of their social location, value, or power (Hunt, 1980, as cited in Maxwell et al., 2003). Maxwell et al. (2003) discuss how Consensus Theory and Conflict Theory present two competing perspectives, that research supporting both perspectives exists, and how Lotz and Hewitt's Five Models (see below) provide a menu of options to explain patterns observed.

Lotz & Hewitt's Five Models

After discussing the competing Consensus and Conflict Theories, Maxwell et al. (2003) introduce Lotz and Hewitt's Five Models (1977). Lotz and Hewitt (1977, as discussed in Maxwell et al., 2003) provide five models concerning the impact of legal and extra‐legal factors on CJS case processing. The first model aligns with Consensus Theory and contends that extra‐legal factors, like race, are not empirically related to outcomes; only legal factors, like a defendant's prior record, explain outcomes. The second model argues that extra‐legal factors may be significant, but are based on how closely tied the defendant is to their community and their family, not the defendant's race (or class or sex). The third model, more consistent with Conflict Theory, argues that class and racial biases play a role early on in the CJS response—at arrest—and go on to impact final case outcomes; harsher treatment of “minorities and those in lower classes” results from systemic racial and class bias, not from the severity of the offense or prior criminal record. The fourth model, consistent with Conflict Theory and Labeling Theory (discussed below), describes the sentencing process as a power play between CJS agents who do the labeling, and defendants who are labeled. How much power a particular defendant has depends on their race (as well as sex and class), thus influencing case processing. The fifth and final model, also consistent with Conflict Theory, contends that race, and other irrelevant factors, impact sentencing, yet in the opposite direction. At the time of sentencing, “minorities and lower class defendants” are treated more leniently compared to “Whites and upper class defendants” as the courts attempt to correct for the disproportionately high rates of arrest by police of “minorities and lower class defendants.” Maxwell et al. (2003) explain that these five models help illuminate how the same theory—Conflict Theory—may produce seemingly contradictory findings. No other articles referenced these Five Models.

Procedural Justice

One article drew upon concepts of Procedural Justice to complement their primary application of Black's Theory of Law. Briggs and Opsal (2012) argue that CJS case processing is dependent on both police action, and victim cooperation. Tyler's Procedural Justice framework (2004, as referenced in Briggs & Opsal, 2012) argues that when community members perceive CJS procedures as fair, they are more likely to view the system as legitimate, and to ultimately cooperate with police and other system personnel. Briggs and Opsal (2012) explain that existing research has documented that “blacks,” and has suggested that “Hispanics,” view these systems and actors as having decreased legitimacy, which leads to such victims being less cooperative, and to their cases not progressing in the CJS.

Labeling Theory

One article employed Labeling Theory to support their primary use of Conflict Theory in examining the CJS response to SA, though the authors’ use of these two theories was not explicitly tied to race. LaFree (1980b) briefly explains that labeling theory suggests criminal justice agents’ stereotypes for crimes influence their decision‐making in responding to crime. Thus, “the more similar the characteristics of victims, offenders, and offenses are to the typifications of rape held by processing agents, the more likely an incidence is to result in the conviction of an accused offender” (LaFree, 1980b, p. 835).

Sample Selection and Composition

Sample Sizes

Sample sizes ranged from n = 89 to n = 226,496, with an average of n = 8,398 and median of n = 413. However, the largest sample included cases of SA, as well as robbery, aggravated assault, and simple assault. Of the study samples that only included SA cases, the largest sample was n = 22,876. As can be expected, studies with the largest samples came from national databases, including the National Incident‐Based Reporting System (NIBRS) of the Federal Bureau of Investigation and National Pretrial Reporting Program (NPRP), funded by the Bureau of Justice Statistics. The largest single state and city samples came from Texas at n = 3,644, and Chicago at n = 1,530, respectively.

Sample Locales

Using the U.S. Census Bureau's four census regions (https://www.census.gov/geo/reference/gtc/gtc_census_divreg.html), fourteen studies (41.2%) used samples from the Midwest: ten studies drew samples from Midwestern cities, such as Chicago or Detroit; three studies drew samples from Midwestern counties, such as Hamilton County, Ohio; and one study from “two Midwestern communities” (Shaw & Campbell, 2013). Ten of the fourteen studies conducted with samples from the Midwest (71.4%) found at least one statistically significant race finding while the other four reported no statistically significant race findings or trends. Six studies’ samples (17.6%) came from the South, sampling from a single Southern city—Miami; multiple counties in a single Southern state—Texas; multiple counties across multiple Southern states; or single states, such as Texas and Georgia. Four studies with samples from the South found at least one statistically significant race finding, with the remaining two articles reporting a trend or pattern that suggested a race influence. Four studies’ samples (11.8%) came from the West: two studies sampled from Western cities, including Los Angeles and San Diego; one from a Western county—Sacramento County; and one from a Western state—Arizona. Half of the studies with samples from the West reported at least one statistically significant race finding, with the other half reporting trends or patterns that suggested a race influence. The remaining studies (n = 7; 20.1%) drew samples from several cities spanning several states and U.S. regions. This included a series of studies that drew samples from Kansas City (Midwest region) and Philadelphia (northeast region), with one of these studies also including cases from Miami (Southern region). This also included four studies with samples that included cities or counties from all regions of the United States, or were national in scope. Five of these studies (71.4%) reported at least one statistically significant race finding. Locale information was not provided for the remaining three studies (8.8%).

Cases Included in Sample

Studies varied in terms of which cases were, and were not, included in study samples. One study included all cases for which victims presented to a medical facility for post‐assault care, regardless of if they reported the assault to the CJS or not; this study found at least one statistically significant race finding. Fifteen studies only included SA cases that had been reported to police in their study sample, with nine of these requiring an additional related criterion, such that the case be reported and have an associated forensic exam or rape kit for the victim (n = 3); be reported and founded by police (n = 2); be reported and included in NIBRS data provided by police agencies (n= 3); or be reported, have an associated forensic exam, and have a suspect identified (n= 1). Sixty percent of the studies that limited their sample to reported cases (n = 9) reported at least one statistically significant race finding, with an additional study reporting trends. Six studies only included cases that had an arrest (n= 1), referral to the prosecutor (n= 2), or both (n= 3). One third of these studies reported at least one statistically significant race finding (n= 2), with an additional third of these studies reporting a race trend that did not reach statistical significance (n= 2). Four studies required that cases not only be reported and referred to the prosecutor, but also charged by the prosecutor. Two of these studies included an additional criterion paired with charging, such that the charges not being dismissed, or that a suspect also be arrested. Six studies’ samples only included cases that resulted in a conviction. All studies with samples limited to cases that had been charged, and studies limited to cases that resulted in a conviction, reported at least one statistically significant race finding. Finally, two studies’ samples were limited to cases in which the offender was incarcerated; one of these studies reported a statistically significant race finding, while the other reported a race trend that did not reach statistical significance.

Samples’ Racial Composition

Studies varied in how samples’ racial compositions were reported, with some reporting only victim race, only offender race, only the victim/offender dyad, or a combination of these. Eighteen studies reported on the race of the victims associated with cases in their samples. In nine of these studies, “white,” “Caucasian,” and “white nonHispanic” victims made up the largest proportion of the samples (43%–86%); “Black” or “African‐American” victims made up the largest proportion of the samples for seven studies (51%–89%); “Hispanic” victims made up the largest proportion of one study's sample (47%); and “non‐White” victims made up the largest proportion of one sample's study (66%). Eighteen studies reported on the race of the suspects associated with the cases in their samples. “Black” offenders made up the largest proportion of twelve studies’ samples (41%–94%). “White” offenders made up the largest proportion of the samples for four studies (58%–95%); and “non‐White” offenders made up the largest proportion of one study's sample (77%). The final study that reported offender race indicated that offender race was not recorded in the majority of cases (58%), as race was coded from medical examiner records (Gray‐Eurom, Seaberg, & Wears, 2002). Of the cases in which offender race was recorded, the majority (32%) were “black.” Six studies reported on the victim/offender racial dyad. In four of these studies, the largest proportion of the sample consisted of “black intraracial dyads” (40%–74%); “white suspect/white victim” dyads made up the largest proportion of the samples in the remaining two studies (35%).

Data Sources

All studies relied on CJS records or national databases. Four studies used national databases, including NIBRS and NPRP. The remaining studies relied on police records (n= 14); county records (n= 2); corrections records (n= 1); court records (n= 1); judge's referral paperwork (n= 1); prison records (n= 1); crime lab records (n= 1); some combination of police, prosecutor, and court records (n=6); or an unspecified form of CJS records (n= 3). Four studies also used medical records.

Race Coding

Victim Race, Suspect Race, and Racial Dyads

In eleven of the studies, victim and suspect race were coded and analyzed as separate variables. Eight of the studies coded for and included variables in analysis for victim/suspect racial dyad, in addition to victim race and suspect race. Six studies coded and analyzed only victim race; five studies only suspect race; and four studies only the victim/suspect dyad. All of the studies that coded and analyzed dyads alone (n= 4) or suspects alone (n= 5) reported at least one statistically significant or trending race finding. About three‐quarters of the studies that coded and analyzed victim and suspect race as separate variables (n= 8; 73%), or that coded and analyzed victim race, suspect race, and racial dyad as separate variables (n= 6; 75%) reported at least one statistically significant or trending race finding. One‐third of studies that coded and analyzed victim race alone reported at least one statistically significant race finding (n= 2; 33%).

Race Categories

Fifteen studies coded race into one of two categories: “Black”/“African American”/“Negro” versus “White.” Some of these studies explained that only two categories were provided because “there were very few complainants and suspects from other racial or ethnic categories” (Holleran et al., 2010, p. 397). Eighty percent (n= 12) of studies that used a black/white dichotomy found at least one statistically significant race finding. Ten studies coded race into “white” versus “non‐white”/“victims of color”, though two of these studies noted that “African‐Americans made up most of the non‐White category” (Roberts, 2008, p. 65) or that “all but one victim of color were Black/African‐American” (Shaw et al., 2016, p. 453). Sixty percent (n= 6) of studies that used a white/non‐white or white/person of color dichotomy found at least one statistically significant race finding, with an additional two studies finding at least one trending race finding that did not reach statistical significance. Three studies used three race categories: “white” versus “black” versus “Hispanic.” These three categories were treated as being mutually exclusive. Two of these studies found at least one statistically significant race finding, with the third reporting a trending race finding. Two studies used “black” versus “white” versus “Hispanic,” and provided a fourth “other” category. Both of these studies reported at least one statistically significant finding. One study coded race and ethnicity separately, including a code for “white” versus “black,” and a code for “Hispanic” versus “non‐Hispanic,” resulting in four categories: white non‐Hispanic, black non‐Hispanic, white Hispanic, and black Hispanic. This study found no significant race finding. One study coded race as either “Caucasian” or “American Indian,” noting that “studies including multiple minority groups are important, however, exclusive focus on American Indians allows for more specific analyses and discussions of this neglected group” (Alvarez & Bachman, 1996, p. 551). This study reported a trending race finding, though it did not reach statistical significance. One study coded race into categories of “Caucasian” versus “non‐Caucasian,” versus “Hawaiian,” and reported at least one statistically significant race finding. The remaining study did not report how it coded race.

Outcomes of Interest and Findings

Studies examined a range of outcomes related to all stages of the CJS process, from the specific investigate steps completed by law enforcement, to prosecutor charging decisions, to final case dispositions and sentencing outcomes.

Police Investigations

Investigative steps

Five studies examined the investigative steps taken by police during the course of an investigation, prior to an arrest being made or the case being referred to the prosecutor's office for the consideration of charges. These studies found that cases with “black” or “Non‐White” victims were more likely to have their rape kit submitted by police to a crime lab for analysis and to have a suspect identified (Horney & Spohn, 1996; Shaw & Campbell, 2013), but that the race of the victim, suspect, and dyad had no impact on if there was a suspect line‐up or suspect interview (Frazier & Haney, 1996; Kerstetter, 1990). Shaw et al. (2016), in looking for mechanisms that explained how race had its impact, found that race did not directly predict the overall number of investigative steps completed on a given SA case. Rather, the race of the victim predicted if police were likely to deem the victim uncooperative or otherwise blame the victim for the less‐than‐thorough police investigation, which then predicted the number of investigative steps completed. In this study, Shaw et al. found that “black” victims were more likely to be deemed uncooperative, which then meant fewer investigative steps were completed. Taken together, these findings align, as it is possible that “non‐white”/“black” victims are more likely to have their rape kits submitted and a suspect identified initially, but then are deemed uncooperative during the investigation, which halts the investigation and precludes a suspect line‐up or interview.

Unfounding

During an investigation, police may decide to “unfound” a case, meaning they determine no crime occurred and close the case. Four studies examined unfounding. Three reported no significant effect of victim, suspect, or dyad race (Bouffard, 2000; Kerstetter, 1990; Spohn et al., 2014). Tellis and Spohn (2008), however, found that among “White” victims, cases with “White” suspects were more likely to be unfounded than cases with “Hispanic” suspects. This finding may have been due to Tellis & Spohn's nuanced approach to examining race. In examining unfounding decisions, Bouffard (2000) examined racial dyads, but only had categories for “White” and “African‐American” victims and suspects; Spohn et al. (2014) provided a third category—”Hispanic”—but did not examine dyads. Tellis and Spohn (2008) examined dyads, and included a category for “Hispanic” victims and suspects. If a dyad approach were not taken, and a category for “Hispanic” not provided, they would not have been able to learn that cases involving “White” victims with “White” suspects were more likely to be unfounded than those with “Hispanic” suspects. It is not possible to evaluate where Kerstetter's study (2000) falls in this, as information on how race was categorized is not provided.

Clearance by arrest

Nine articles examined predictors of case closure by arrest or exceptional means, meaning a suspect has been identified and arrested, or that the police were prepared to make an arrest, but were unable to do so due to exceptional means (e.g., the suspect is deceased). Cases involving “White” victims, “white” suspects, and “White intraracial” dyads were more likely to result in arrest, and for suspects to be arrested on a greater number of charges (Addington & Rennison, 2008; Kingsnorth et al., 1998; LaFree, 1981; Shaw et al., 2016). Addington and Rennison (2008) and Roberts (2008) found the opposite, with (“Non‐Hispanic”) “white” victims less likely to have their cases cleared by arrest. However, both of these studies were conducted with large samples from NIBRS data (n = 22,876; n = 11,215, respectively). Addington and Rennison note that “because of the large sample size, almost all of the predictors and controls are statistically significant. As such, it is important to consider the “substantive” (or clinical) significance and examine the effect size” (p. 216). Both studies reported relatively small odds ratios for the race effect (OR = 0.88; OR = 1.113, respectively). An additional four studies reported no statistically significant effect of victim, suspect, or dyad race on arrest (Bouffard, 2000; Briggs & Opsal, 2012; Kerstetter, 1990; LaFree, 1980a). Similar to patterns observed in unfounding (see discussion above), studies that reported no significant race findings on arrest had less nuance in their measurement and analysis. For example, LaFree's studies in 1980a and 1981 relied on the same data. The earlier study reported no significant race finding on arrest. However, when the data were revisited in 1981, LaFree included an examination of the influence of race on arrest before and after an SA unit was implemented in the focal jurisdiction. Accounting for this additional influencing feature revealed a significant relationship between race and arrest.

Referral to the prosecutor

In order for a case to proceed to prosecution, it must be referred to the prosecutor by police for the consideration of charges. Only one study examined the influence of race on the likelihood of a referral to the prosecutor. Shaw et al. (2016) found that race indirectly predicted referral to the prosecutor's office. “Black” victims were more likely to be deemed uncooperative by police, or otherwise disruptive to the investigative process, which then decreased the likelihood that the case would be referred to the prosecutor's office.

Summary

Looking at the police investigation in totality, prior research finds that cases involving folks of color were more likely to have a suspect identified initially and the rape kit submitted to the crime lab for analysis. However, victims of color—more specifically, Black victims—were more likely to be deemed uncooperative or otherwise disruptive to the investigation by police. This results in fewer investigative steps being completed throughout the investigation, including a suspect lineup, suspect interview, arrest, and referral to the prosecutor. That victims of color are met with a less thorough CJS response lends support to several of the theories identified herein, such as Black's Theory of Law, Social Dominance Theory, and Blameworthiness Attribution Theory.

Prosecutor Action

Charging decisions