Abstract

Unintentional injuries, the leading cause of morbidity and mortality among youth in the United States, are burdensome and costly to society. Continued prevention efforts to reduce rates of unintentional injury remain imperative. We emphasized the role of practitioner influence across a linear concept of injury prevention comprising delivery, practice, and application/generalization and within the context of child developmental factors. Specific strategies for injury prevention tailored to the cognitive development stage of the patient are provided. This information may be useful to health care practitioners, who have significant interaction with youth and their families.

Keywords: pediatrics, safety, prevention

“The concept of practitioners as an important point of contact for reducing health risks is not new and has been exploited in other fields”

Unintentional injuries are a serious health concern for young Americans and the leading cause of death for individuals 1 to 17 years old.1 Approximately 4169 children and adolescents aged 1 to 17 years in the United States died, and more than 6.7 million required medical treatment following an unintentional injury in 2014.1 Knowledge of injury etiology and prevention has increased, but continued efforts to address unintentional injury as a health problem remain imperative.2

One way unintentional injury risk can be decreased is through interaction between practitioners, children or adolescents, and parents. We define practitioners here as primarily doctors and nurses, but the term could be extended to any person providing treatment to a patient. The concept of practitioners as an important point of contact for reducing health risks is not new and has been exploited in other fields—for example, counseling by dentists to reduce tobacco use.3 However, time available to practitioners during visits with patients may not afford opportunities to engage in lengthy interventions, increasing the importance of efficient and effective use of interactions between practitioners and patients. Our aim is to explore how practitioners may better ensure that injury prevention efforts are received and comprehended by tailoring interventions to children’s cognitive developmental abilities.

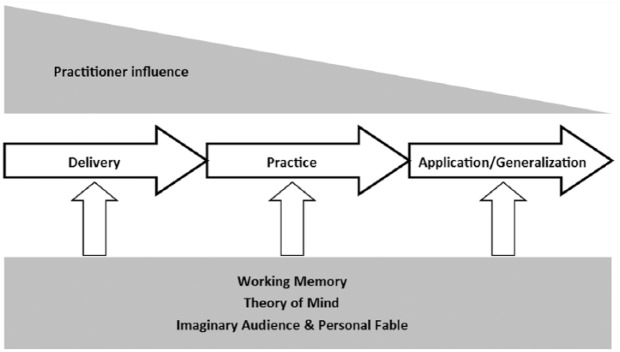

To illustrate the process we explore here, we present a model showing our conceptualization of how practitioner influence is interrelated with injury prevention and child development (Figure 1). Our model, an adaptation of a common teaching method,4 is a linear process of injury prevention comprising delivery, practice, and application/generalization. This linear process occurs within the context of child developmental factors and relevance of efforts by practitioners. The potential impact of practitioners on injury prevention decreases as children, adolescents, or caregivers move beyond the direct influence of the practitioner and apply or generalize newly learned information in the world beyond. Key cognitive developmental characteristics are shown in our model, tempering reception of injury prevention throughout the process. Concepts in the model are intended to apply to children and adolescents or, if a child is very young, to a caregiver responsible for the child’s safety.

Figure 1.

Model of practitioner and cognitive influence across the linear process of prevention.

Linear Concept of Prevention

Our conceptualization of injury prevention is straightforward. The individual is taught or informed about a given topic (in our case, injury risk—ie, Delivery). Discussion or actual practice of a preventive behavior follows (ie, Practice). Finally, the individual is expected to maintain and apply newly learned behaviors beyond the context of the prevention effort (ie, Application/Generalization).

Delivery

Delivery of injury prevention is the point at which practitioners potentially have the most influence. Practitioners transmit messages or techniques for decreasing injury risk to patients or parents, thus having an impact on factors resulting in unintentional injury.5 Delivery of prevention efforts include consideration of how messages are worded, whether a particular spokesperson may more effectively transmit the message (practitioner, parent, other child, or character), and use of tangible or visual materials. Injury prevention at this initial stage may simply consist of discussion about a safety concern, but also could include demonstration of safe behaviors. Delivery of information may be tailored to fit the needs of the child or family. For example, the information may need to be presented in Spanish for non-English speakers. In addition, “precision medicine” should take into account the individual difference factors that may exacerbate risks of injury for some youth (eg, developmental disabilities, risk-taking propensity).6 Some prevention efforts may end at the delivery stage (eg, providing parents only with literature about a particular safety concern) but, ideally, will continue into the second part of the process: practice.

Practice

The purpose of practice is to make the newly learned information concrete. Practice will include any element of the prevention effort requiring the person being protected to perform or rehearse the safe behavior in some way—for example, practicing pedestrian crossings on a table-top street model, on a nearby street if time permits, or in a realistic simulation of a pedestrian environment if one is available. Practice also may involve guided participation with a parent or practitioner or, perhaps, group tasks including other children. Parents, rather than children themselves, may be the targets of the practice stage if injury hazards for young children are of concern. If physically performing a safe behavior is not practical, a practitioner may discuss how safety concerns are being addressed in the household. We depict decreasing impact from practitioners in this second stage in the model because practice may be more likely to require time and resources not consistently available. We also acknowledge that the practice stage is very likely to be limited by time constraints faced by most practitioners. The practice stage of prevention serves to manifest concepts from the delivery stage into concrete experiences for children, adolescents, or caregivers. The occurrence of some form of practice, even if only for a few moments, is perhaps more important than whether practice comprises discussion or actual physical participation. That is, practice does not need to be elaborate and time-consuming. Making information learned during delivery concrete in some way is the goal.

Application/Generalization

The final stage in our injury prevention process is application/generalization. Safe behaviors, in this stage, are performed in the world beyond the direct influence of the practitioner: for example, parents who have received prevention aimed at reducing poisonings among young children acting to place household chemicals out of reach of children in their home, parents ensuring smoke detectors are in working order, or children engaging in safer road crossing behaviors.

We place generalization of safe behavior, although conceptually distinct, also in this final stage. Generalization requires a child or caregiver to recognize the relevance of recently acquired information or safe behavior in a context that does not match the one encountered in earlier stages of prevention and then execute safe behaviors in the new context. Put differently, the concept of generalization requires extension of learning to similar contexts and is more than merely replication of behavioral performance: for example, parents addressing child safety concerns after moving into a new household or children engaging in safe crossing behaviors on streets designed differently than those encountered during prevention. As shown in the model, we propose that direct practitioner influence may be minimal at this final stage for 2 reasons. First, both injury risk behaviors and preventive behaviors occur in contexts in which the practitioner is not present. Second, injury risk behaviors and preventive behaviors in the world beyond the practitioner’s office rest on the ability of the person at whom prevention was aimed—individual characteristics over which the practitioner has no influence.

Tailoring Injury Prevention

Injury prevention may be more effective if tailored to the recipient6,7 rather than delivered in a uniform fashion. Tailoring injury prevention is particularly relevant when developmental level varies among recipients.8 The need for tailoring prevention efforts to the characteristics of the person being protected has been explored for more than a decade. Early work compared generic and tailored injury prevention messages delivered during well-child visits in a caregiver setting.9 The “Baby, Be Safe” prevention effort generated customized handouts for parents after an initial baseline assessment. Caregivers who received the prevention were more likely to adopt safe behaviors on follow-up, an effect enhanced if discussion with a practitioner occurred. Tailored messages were again compared with generic messages delivered during well-child visits in a primary care setting but with the intentional addition of practitioner involvement.10 Caregivers who received tailored prevention messages, both with and without practitioner involvement, were more likely to have adopted safe behaviors at follow-up. Such results of tailored injury prevention correspond to the first stage of injury prevention in our model—namely, delivery—and highlight not only the importance of how messages are transmitted, but also the important role practitioners play in enhancing prevention efforts.

In particular, preventions tailored to children’s cognitive development have received increasing empirical support. Cognitive abilities affecting reception of messages, effectiveness of practice, and ability to apply and generalize training can be relevant at all 3 stages of the prevention process. For example, incorporating consideration of children’s cognitive developmental abilities has been suggested to improve effectiveness of pediatric pedestrian injury prevention.7 Specifically, the emergence of child pedestrian and adolescent driving skills appear to parallel certain aspects of executive control around which prevention efforts could be constructed.7,11-13

Another study has tailored delivery of messages and methods to child characteristics in order to reduce specific risk behaviors. Researchers tested whether tailoring intervention to cognitive processing would reduce playground injury risk behaviors by using the induced hypocrisy paradigm.14 The induced hypocrisy paradigm involves creation of cognitive dissonance as a catalyst for behavior change, thus exploiting the practice stage of injury prevention by forcing mental processing, not mere reception, of new information.

Tailored injury prevention delivered in primary care settings has been examined in a handful of studies, as discussed above. However, ways of including practitioners in the tailored process remain to be explored. Our focus in the next section is on how practitioners may be better integrated into the prevention process by tailoring interaction with young patients or their caregivers according to cognitive developmental capabilities. However, before delving into the next section, we caution that we are not proposing that practitioners saddle themselves with the burden of developing elaborate ways of adapting their messages to particular recipients. Instead, we suggest that practitioners be mindful of adapting injury prevention to the recipient within the limits of their time, resources, and training. If well-developed injury prevention tools are available, we suggest that practitioners consider using them.

Cognitive Development and Components of Injury Prevention

We suggest that practitioners may more effectively increase safe behavior if cognitive characteristics of recipients are taken into account. All 3 components of prevention are influenced by cognitive development in our model. We consider 2 specific aspects of child cognitive development: working memory and theory of mind. The key adolescent cognitive developmental concepts we discuss are the imaginary audience and personal fable.

Cognitive development comprises far more complexity than is appropriate (or possible) to include here. Clearly, cognitive development is dynamic and involves many interrelated components, some of which may prove relevant to injury prevention efforts by practitioners. We limit our discussion of relevant cognitive developmental characteristics in the interest of brevity and because each factor has some presence in the literature.

Childhood

Developmental psychologists divide childhood into 3 stages: infancy/toddlerhood, early childhood, and middle childhood. Unintentional injury is a health concern across the lifespan. However, we limit our discussion here to the developmental periods of early and middle childhood.

Early childhood comprises the toddler and preschool years, from 1 year of age until approximately 5 years of age, whereas middle childhood comprises from 5 to 6 years of age until the onset of adolescence.15 Cognitive development during early childhood is rapid in comparison to later periods in the lifespan. We first consider working memory, which refers to the capacity for short-term storage and manipulation of information. Working memory capacity develops steadily across childhood, reaching adult levels around age 15 years but varies widely between children of a given age.16,17 For example, an 8-year-old child with highly developed working memory may be equivalent to a 15-year-old with average capacity.18 In addition to developing larger working memory capacity, children’s ability to use working memory capacity also improves. The developmental increase in children’s working memory capacity enables larger amounts of information to be rehearsed19 and to be used more efficiently.20

The age-related increase in capacity and efficiency of working memory, and a strong relation to language comprehension,21 makes working memory relevant to the delivery of instructions during behavioral interventions. Younger children’s working memory is taxed to a greater degree by increased complexity of information,22 implying that children will be less able to process longer, more complex instructions during behavioral tasks. Thus, shorter, concrete communication between researchers/practitioners and children would perhaps be more effective.

Children will also use working memory capacity to practice skills or behaviors during intervention. This would involve holding newly learned information in memory and manipulating the information in order to achieve the desired safe behavior. For example, a child instructed to cross a street safely by attending to traffic from all directions, being aware of their own visibility to drivers, and choosing from several options of crossing locations is using working memory capacity to organize this information and derive safe behaviors. Working memory capacity will still be in use once an intervention is complete. Children will be required to expend some mental effort generalizing skills and behaviors to other settings.

Theory of mind develops from across childhood and into adolescence. Theory of mind is not a theory per se but a broad concept comprising understanding of emotions, knowledge, and thinking both in oneself and in others.23 For example, younger children understand that behaviors are driven by beliefs and desires but have difficulty differentiating their own beliefs and desires from those of others. Developing theory of mind also affects understanding of perception in physical space, having important implications for injury risk. For example, children have a basic understanding by the end of the preschool years that 2 individuals can have different physical perspectives of the same object or that one individual may not be able to see the object at all.24

Theory of mind will likely affect delivery, practice, and application/generalization of injury prevention. We may assume that most children aged 6 to 10 years old have developed some theory of mind,23,25 but their ability to perceive and mentally manipulate abstract information is limited.26 Fortunately, injury risk situations are concrete (ie, physical and tactile), and these are the situations in which children will have to apply theory-of-mind skills. For example, with theory-of-mind skills, a child will understand that a driver cannot see pedestrians crossing from between parked cars27 or realize that a large dog near the playground may be alarmed if approached by children innocently intending to play. Therefore, training techniques used for injury prevention must be both concrete and emphasize the use of theory-of-mind skills. In addition, although our concern here is cognition, we must mention that developing abilities such as theory of mind exist within a cluster of other factors affecting child behavior (eg, temperamental control).

Adolescence

Adolescence begins at 12 to 13 years of age and extends until the onset of adulthood at around 19 years of age and perhaps into one’s early 20s.15 Brain maturation in regions related to higher-order processes that may be implicated in behaviors increasing injury risk continue to mature through emerging adulthood.28 Cognitive development during the early teen years is marked by the emergence of the capacity for abstract thought, underpinned by neurological changes such as myelination of the frontal lobes, synaptic pruning, and variation in neurotransmitter levels. Adolescent egocentrism, a consequence of development during the early teen years, includes 2 well-known characteristics of thought: the imaginary audience and the personal fable.29 Evidence suggests that these 2 aspects of adolescent cognitive development are linked to reckless behavior.30

The imaginary audience and the personal fable are characterized by the conflict between a tendency toward self-preoccupation and hyperawareness of the perceptions and beliefs of others. The imaginary audience refers to mental construction and reaction to the perceived collective attention of others.29 Adolescents are consequentially highly self-conscious and behave as if under constant, intense scrutiny by peers. The personal fable concerns perception of an inflated sense of uniqueness.29 The adolescent will likely feel that his or her emotional or social experiences are intense, unique, and incomprehensible to adults. As we will discuss in the following sections, each aspect of adolescent egocentrism may interfere with delivery of injury prevention messages, impair the effectiveness of practice, and result in failure to apply or generalize information or behaviors learned during injury prevention efforts.

Implications for Primary Care Practice

Practitioners are stakeholders in preventing injuries. Prevention efforts by practitioners can have direct impact, help reduce burden on families, and ultimately help reduce financial burden on society. Practitioners play an important role in our model of injury prevention in several ways. First, delivery and practice are most directly affected by practitioner efforts. A family’s primary care practitioner is a point of contact for injury prevention, and advice given carries the weight of medical training.

Second, practitioners may not have direct influence on application and generalization of injury prevention, which typically will occur beyond practitioners’ offices, but can play indirect roles. One way practitioners can influence injury prevention beyond patient visits is through partnership and involvement with local safety organizations (eg, Safe Routes to School). Local safety events also are excellent opportunities for practitioners to become involved in injury prevention (eg, Teddy bear picnics, safety fairs, or events hosted by fire departments or law enforcement). Practitioners can increase safety in their community by organizing, participating in, or simply supporting such events.

Guidelines for Primary Caregivers

We offer several simple guidelines for practitioners interested in increasing their effectiveness in injury prevention:

Focus on delivery of prevention, which may be influenced by availability and timing. Practitioners can have the most direct influence during one-on-one time with patients through use of concrete visual and manipulable ways to communicate safety messages and by wording messages in ways younger children can comprehend: for example, providing samples of household safety devices for parents to use (smoke alarms, cabinet locks, or gun locks) and offering information for adolescent drivers and parents to consider.

Practitioners should implement practice of new information or techniques when possible. Time constraints may prevent practice of behaviors with children and adolescents, but perhaps practitioners can (minimally) spend time discussing newly learned information to assist recipients with later generalization. For example, discussion between adolescent drivers and physicians could focus on graduated driver licensing laws and policy and teen-parent contracts.31 Practitioners providing items for parents of young children to use can spend time demonstrating how the items work (eg, reviewing instructions for how to install a gun lock or installing cabinet locks).

Practitioners can become involved with, or support, stakeholder activities in the community.

Practitioners should tailor injury prevention efforts to the cognitive capabilities of the child or adolescent being protected by taking into consideration the developmental stage of the patient. We discuss the characteristics of injuries typical during childhood and adolescence and examples of how practitioners may tailor their interaction with recipients in the next section.

Prevention Process in Context of Practitioner Influence and Cognitive Development

Practitioners interested in efficiently applying injury prevention strategies should be mindful of the most frequent injury types during childhood and how injury types vary developmentally. During early childhood (ages 1 to 4 years), injuries often occur in or near the home. Falls (down stairs, from furniture, or simply while walking or running), poisonings, drowning, cuts, and burns all are typical.32-34 During middle childhood (ages 5 to 9 years), changes occur in types of injuries incurred as children attend school and begin to spend more time outside the home. Motor vehicle–related injuries become the leading cause of death for individuals ages 5 to 24 years old.1 Falls are still among the top 10 most frequent types of injury between ages 5 to 11 years, but injuries related to overexertion, dog bites, bicycling, and being a motor vehicle occupant also are common.1 Children of school age also are at greater risk than younger children for pedestrian injury because they spend more time away from home with friends or going to and from school.7

Adolescents normatively spend increasing amount of time with peers away from parents and family.15 Not surprisingly, unintentional injury types during adolescence comprise those sustained both in and out of the home. Fall, cuts, and bite injuries still rank among the top 10 types of injuries sustained by adolescents.1 However, transportation-related injuries, including bicycling and motor-vehicle occupant/driver incidents, comprise a large portion of adolescent unintentional injuries.1 Risk of unintentional injury while driving is an important target for injury prevention, particularly among older adolescents, which differentiates this developmental period from childhood.

Early Childhood

Our model combines the prevention process, cognitive developmental factors, and practitioner influence. We offer some examples, here and in Table 1, to demonstrate how integration of these factors can be accomplished. We also acknowledge the roles caregivers play in enhancing practitioner efforts at each developmental stage. First, we consider early childhood. Our cognitive developmental factors of interest across all of childhood are working memory and theory of mind. As we have already outlined, each of these cognitive developmental factors function differently during early and middle childhood. Working memory capacity and efficiency are limited during early childhood. Theory of mind is likewise rudimentary, allowing young children limited understanding of the mental processing occurring in the minds of other people.

Table 1.

Examples of Prevention Adapted Across Developmental Levels and Factors.

| Working Memory | Theory of Mind | Imaginary Audience | Personal Fable | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Early childhood | Short, uncomplicated messages and practice (perhaps best delivered to caregiver) | Concrete information and practice kept relevant to child’s immediate surroundings and behavior; inclusion of caregiver in delivery and practice | ||

| Middle childhood | Uncomplicated messages delivered to child | Concrete information and practice, relevant to immediate surroundings; inclusion of simple differences in physical perspective | ||

| Adolescence | Delivery of messages directly to adolescent | Delivery and practice no longer bound by concrete thinking; inclusion of differences in physical and mental perspectives of others | Encouraging modeling of safe behaviors for peers; ie, using inflated personal importance to encourage engagement in safe behaviors | Use of role play, or other methods, to make injury risk more personally relevant; review of delivery stage if necessary |

All phases of the injury prevention process may be affected by developing working memory and theory of mind in young children. Practitioners must be mindful when delivering safety messages, which should be kept short and uncomplicated. In the case of very young children (toddlers), delivery should involve the caregiver rather than the child. When prevention messages are communicated to the child, they should be relevant to the child’s immediate safety and his or her behavior rather than intertwined with perceptions of other people (eg, Does a driver expect a child to run suddenly into the roadway chasing a ball?). Limited theory-of-mind development will create difficulty for children trying to tie their own behavior into the context of perceptions held by others. We suggest that concrete delivery and practice will be the best way to circumvent limitations placed on prevention by early childhood cognitive development. For example, a recent meta-analysis found that delivery of safety messages as a combination of visual and manipulable methods, such as photographs or videos, was most effective.35

Practice will be crucial for manifesting concepts that have only been discussed during the delivery stage. Concrete practice of skills for prevention may be impractical or impossible in some practitioner contexts. However, we offer examples of how practice can more easily be accomplished from the domain of pedestrian safety. Small table-top street models can easily be used indoors and have been used to study pedestrian skills in relation to cognitive development.36 A variety of small, easily stored pedestrian road kits are commercially available that could be used on the floor in the practitioner’s office. Likewise, pedestrian safety teaching kits are available from transportation departments in most of the United States. Such kits may be used in practitioners’ offices. Practitioners may also direct parents toward pedestrian safety kits (or materials for other injury types), so parents may practice safe behaviors with their children at home, thereby shifting some burden of practice from the office to the home.

We have so far mentioned only a few cognitive developmental constraints on delivery and practice during injury prevention. Such developmental constraints highlight the critical role caregivers play in injury prevention during early childhood. We suggest that caregivers may often be the primary targets during the delivery and practice phases of the prevention process. Motor vehicle–related injuries among young children offer one example of why targeting caregivers is important. Children are injured as passengers riding in child car seats or booster seats. Caregivers are responsible for implementing safety devices in their vehicles and, thus, have full control over such injuries at young ages. In contrast, poisonings among young children involve behavior on the part of children themselves, meaning the child should be targeted. However, caregivers remain extremely important because they are responsible for storage of medicines and chemicals in the household.

Middle Childhood

Practitioners may more often target prevention at children themselves during middle childhood. Although caregivers remain an important influence, during middle childhood an increasing amount of time is spent with peers.15 Concrete methods during delivery remain important when working with children in the middle childhood years. However, working memory skills and theory of mind have advanced beyond early childhood levels. Practitioners should remain mindful of simplicity during delivery, but memory ability will be less likely to inhibit absorption of messages. Children will be better able to consider the physical and perceptual variation in perspectives of other people (eg, simple physical perspective of drivers for pedestrian safety; social aspects of helmet use for safe bicycling). We caution, however, that most children are not yet functioning at an adult level of theory of mind even at the end of middle childhood. Overall, we suggest that concrete methods are important across childhood for making delivery and practice more effective during injury prevention. Cognitive advances during middle childhood may free practitioners from the need for purely concrete methods, depending on the developmental levels of individual children.

During middle childhood, developmental factors should not be quite as constraining as those in early childhood. Practitioners can shift more focus onto the child. However, we suggest that both children and caregivers still be the targets of injury prevention efforts during middle childhood. Caregivers can play a role in helping the child understand messages delivered and in helping newly learned behaviors to be practiced once beyond the practitioner’s office. Caregivers also remain in an important supervisory position in their children’s lives—for example, helping structure activities in and out of school and controlling access to injury hazards around the home. Pedestrian safety offers one such example of parental structure, with parents walking to and from school with their children or being reluctant to allow children to cross without supervision until the end of middle childhood and even then, only if the caregiver feels that the child has demonstrated competence. Indeed, children should not be allowed to cross streets alone until the end of middle childhood. Our suggestion, overall, is that practitioners’ delivery of safety messages and practice should be balanced between the child and caregiver during middle childhood. With respect to some types of injury (eg, pedestrian), caregivers may be the primary targets.

Adolescence

We suggest the imaginary audience and personal fable are important developmental factors in injury prevention during adolescence. Both aspects of adolescent egocentrism lead adolescents to feel they are unique and under constant, intense scrutiny; a heightened sense of self-consciousness. The imaginary audience and personal fable may weaken all 3 phases in the process of injury prevention. The personal fable, in particular, may make adolescents resistant to delivery of safety messages; that is, the feeling of uniqueness makes messages of personal risk irrelevant because injury risk applies to other people and not oneself. The imaginary audience can weaken the practice and application/generalization phases. Practice of safe behaviors, and later application, will not be done in a meaningful way if under perceived intense scrutiny. The focus of such behavior in the adolescent will be on how others perceive the behavior, rather than on gaining maximum benefit for safety. Practice and application may be further weakened if new knowledge and behaviors were seen as not applicable to oneself in the first place.

We envision at least 2 paths for practitioners working with adolescents in the context of adolescent egocentrism. First, practitioners can attempt to work around the potentially harmful effects of adolescent egocentrism on injury prevention efforts. The effect of the personal fable may be counteracted through use of role play.37,38 Role play can help make the information at hand more personally relevant during the practice phase. Practitioners may then briefly move backward in the prevention sequence and revisit the delivery phase after practice has made the information more concretely relatable to the adolescent. Second, adolescent thinking could be exploited to increase safe behaviors.39 If adolescents view themselves as under close scrutiny and sufficiently unique as to be interesting, then adolescents could be encouraged to model safe behavior for their peers’ sake. For example, “I am already a better driver than my peers, but since they all pay attention to me maybe I can help them by showing them how to be a safe driver.”

Adolescence is a period during which autonomy and differentiation of oneself from one’s caregivers becomes increasingly important. As such, adolescents may be resistant to parental involvement in their safety. However, caregivers do remain relevant to injury prevention among adolescents. For example, motor vehicle safety again offers insight into how caregivers can be influential. In many states, adolescents must spend time driving with their caregivers before obtaining a license, bringing caregivers directly into training adolescents how to drive as well as imparting knowledge and attitudes toward road safety. Parents also often own and maintain the vehicle their adolescent drives. Thus, caregivers often control access to vehicles, making them particularly important targets for injury prevention efforts by practitioners.

Application/Generalization: Practitioner and Developmental Influences

Our model shows that practitioners have potentially the least amount of influence on application/generalization of injury prevention. Younger children, and even some adolescents, may have great difficulty remembering to apply newly learned information or skills for injury prevention. Even greater difficulty may be encountered by children when a need for generalization arises, and indeed, generalization may be beyond the cognitive capability of some younger children. Children and adolescents are obviously not likely to be in the practitioner’s presence when application and generalization are needed.

Practitioners remain influential, however, at this final stage of injury prevention through supporting and participating in local events targeting safety. For example, the first author’s community hosts an annual children’s safety fair, in which several local practitioners, a hospital, fire personnel, law enforcement, and other safety organizations (eg, Safe Routes to School) are participants. Local practitioners involved in the safety fair contribute in several ways, including speaking with families at the event, helping direct the event by serving on a board of officers, providing literature to disseminate to the public, and providing financial support to caregivers for safety equipment such as bicycle helmets. Beyond local events, other stakeholders, such as law enforcement and Safe Routes to School, become points of contact supporting application and generalization of safe behavior. Practitioner support and cooperation with other stakeholders helps extend practitioner influence beyond the practice stage of injury prevention.

A final consideration for application and generalization is the role of practitioners in helping ensure that newly learned skills or information are actually being used. For practitioners who see patients on a regular basis, follow-up could be accomplished during regularly scheduled office visits or checkups. In other instances, however, the patient may see the practitioner only once (eg, emergency department visit). When the patient has no follow-up visit scheduled, we suggest that perhaps another type of practitioner, such as a nurse, may be able to contact the patient and have some influence (even if small) on application and generalization.

Some Limitations and Conclusion

Several limitations of our proposed process are worth mentioning. First, and perhaps most obvious, practitioners probably will have little time to engage in injury prevention efforts during visits with children, adolescents, and caregivers. Second, practitioners will likely not have access to sophisticated materials for injury prevention. Third, materials and facilities for delivering injury prevention will vary greatly, making prevention efforts inconsistent. Such challenges are likely to be encountered by any practitioner interested in playing a role in prevention of unintentional injury. However, our intent is not to recommend implementation of elaborate, time-consuming efforts for injury prevention within the already busy context of a practitioner’s other duties. Rather, we have offered an ideal from which deviations will certainly occur among interested practitioners.

A fourth limitation is that our proposed model will likely be difficult to apply to individuals with special cognitive considerations. Two examples of such considerations are attention-deficit hyperactivity disorder and autism spectrum disorders. In either case, the nature of the child or adolescent’s cognitive processing will likely make delivery and practice for injury prevention difficult for the child and the practitioner. In such cases, we suggest that the caregiver should be the primary target for prevention. We have mentioned 4 limitations here. Practitioners may encounter other unforeseen challenges. Although injury prevention may be difficult for practitioners to enact, we maintain that any effort to prevent unintentional injury is worthwhile even if the impact is minimal.

We also must note that the process of delivery, practice, and application/generalization is relevant to yet another audience: those who develop materials for practitioners. As we have already mentioned, practitioners will likely be faced with a short time in which to implement delivery and practice. Researchers, nonprofit, or government organizations preparing and disseminating materials for injury prevention may use our recommendations to indirectly support practitioner efforts by adapting materials to the process, the developmental considerations, and the practitioner influence shown in Figure 1. For example, preparing materials for practitioners to use under time constraint, for use by varying types of practitioners, or for use with patients from various developmental backgrounds all may be useful in implementing more effective injury prevention.

Practitioners are important stakeholders and points of contact for injury prevention but are afforded relatively little time with children and adolescents during office visits. We suggested a linear model of injury prevention around which practitioners may structure more effective injury prevention. Tailoring injury prevention to cognitive context is important across all phases of prevention. Practitioners must generally be mindful of cognitive limitations but among adolescents, perhaps, exploit cognitive limitations for better injury prevention. Simplicity and concreteness are important throughout the process of prevention.

Footnotes

Declaration of Conflicting Interests: The author(s) declared no potential conflicts of interest with respect to the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

Funding: The author(s) received no financial support for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

Ethical Approval: Not applicable, because this article does not contain any studies with human or animal subjects.

Informed Consent: Not applicable, because this article does not contain any studies with human or animal subjects.

Trial Registration: Not applicable, because this article does not contain any clinical trials.

References

- 1. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Injury prevention and control: welcome to WISQARSTM. https://www.cdc.gov/injury/wisqars/index.html. Accessed November 15, 2017.

- 2. Alonge O, Hyder AA. Reducing the global burden of childhood unintentional injuries. Arch Dis Child. 2014;99:62-69. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Warnakulasuriya S. Effectiveness of tobacco counseling in the dental office. J Dent Educ. 2002;66:1079-1087. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Reinhartz J, Van Cleaf D. Teach-Practice-Apply: The TPA Instruction Model, K-8. West Haven, CT: NEA Professional Library; 1986. [Google Scholar]

- 5. Garzon DL. Contributing factors to preschool unintentional injury. J Pediatr Nurs. 2005;20:441-447. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Winston FK, Puzino K, Romer D. Precision prevention: time to move beyond universal interventions. Inj Prev. 2016;22:87-91. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Barton BK. Integrating selective attention into developmental pedestrian safety research. Can Psychol. 2006;47:203-210. [Google Scholar]

- 8. Morrongiello BA, Schwebel DC. Gaps in childhood injury research and prevention: what can developmental scientists contribute? Child Dev Perspect. 2008;2:78-84. [Google Scholar]

- 9. Nansel TR, Weaver N, Donlin M, Jacobsen H, Kreuter MW, Simons-Morton B. Baby, be safe: the effect of tailored communications for pediatric injury prevention provided in a primary care setting. Patient Educ Couns. 2002;46:175-190. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Nansel TR, Weaver NL, Jacobsen HA, Glasheen C, Kreuter MW. Preventing unintentional pediatric injuries: a tailored intervention for parents and providers. Health Educ Res. 2008;23:656-669. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Pope CN, Ross LA, Stavrinos D. Association between executive function and problematic adolescent driving. J Dev Behav Pediatr. 2016;37:702-711. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Pope CN, Bell TR, Stavrinos D. Mechanisms behind distracted driving behavior: the role of age and executive function in the engagement of distracted driving. Accid Anal Prev. 2017;98:123-129. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Tabibi Z, Borzabadi HH, Mashhadi A, Stavrinos D. Predicting aberrant driving behavior: the role of executive function. Transp Res Part F Traffic Psychol Behav. 2015;34:18-28. [Google Scholar]

- 14. Morrongiello BA, Mark L. “Practice what you preach”: induced hypocrisy as an intervention strategy to reduce children’s intentions to risk take on playgrounds. J Pediatr Psychol. 2008;33:1117-1128. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Berk LE, Meyers AB. Infants, Children, and Adolescents. 8th ed. London, UK: Pearson; 2015. [Google Scholar]

- 16. Gavens N, Barrioullet P. Delays of retention, processing efficiency, and attentional resources, in working memory span development. J Mem Lang. 2004;51:644-657. [Google Scholar]

- 17. Gathercole SE, Pickering SJ, Ambridge B, Wearing H. The structure of working memory from 5 to 15 years of age. Dev Psychol. 2004;40:177-190. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Gathercole SE, Alloway TP. Working memory and classroom learning. J Prof Assoc Teach Students Specific Learn Difficulties. 2004;17:2-12. [Google Scholar]

- 19. Ornstein PA, Naus MJ, Liberty C. Rehearsal and organization processes in children’s memory. Child Dev. 1975;46:818-830. [Google Scholar]

- 20. Flavell JH, Beach DR, Chinsky JM. Spontaneous and verbal rehearsal in memory task as a function of age. Child Dev. 1966:37:283-299. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Willis CS, Gathercole SE. Phonological short-term memory contributions to sentence processing in young children. Memory. 2001;9:349-363. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Stins JF, Polderman JC, Boomsma DI, de Geus EJC. Response interference and working memory in 12-year-old children. Child Neuropsychol. 2005;11:191-201. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Flavell JH. Theory-of-mind development: retrospect and prospect. Merrill Palmer Q. 2004;50:274-290. [Google Scholar]

- 24. Flavell JH. Development of knowledge about vision. In: Levin DT. ed. Thinking and Seeing: Visual Metacognition in Adults and Children. Cambridge, MA: M I T Press; 2004:13-36. [Google Scholar]

- 25. Bartsch K, Wellman HM. Children Talk About the Mind. New York, NY: Oxford University Press; 1995. [Google Scholar]

- 26. Piaget J. Part I: cognitive development in children: Piaget development and learning. J Res Sci Teach. 1964;2:176-186. [Google Scholar]

- 27. Ampofo-Boateng K, Thomson JA. Children’s perception of safety and danger on the road. Br J Psychol. 1991;82(pt 4):487-505. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Giedd JN. The teen brain: insights from neuroimaging. J Adolesc Health. 2008;42:335-343. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Elkind D. Egocentrism in adolescence. Child Dev. 1967;38:1025-1034. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Arnett J. The young and the reckless: adolescent reckless behavior. Curr Dir Psychol Sci. 1995;4:67-71. [Google Scholar]

- 31. Campbell BT, Borrup K, Salaheen H, Banco L, Lapidus G. Intervention improves physician counseling on teen driving safety. J Trauma. 2009;67(1, suppl):S54-S57. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Garzon DL, Lee RK, Homan SM. There’s no place like home: a preliminary study of toddler unintentional injury. J Pediatr Nurs. 2007;22:368-375. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Ozanne-Smith J, Day L, Parsons B, Tibballs J, Dobbin M. Childhood poisoning: access and prevention. J Paediatr Child Health. 2001;37:262-265. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Wintemute GJ. Drowning in early childhood. Pediatr Ann. 1992;21:417-421. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Shen J, Rouse J, Godbole M, Wells HL, Boppana S, Schwebel DC. Systematic review: interventions to educate children about dog safety and prevent pediatric dog-bite injuries: a meta-analytic review. J Pediatr Psychol. 2017;42:779-791. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Barton BK, Ulrich T, Lyday B. The roles of gender, age, and cognitive development in children’s pedestrian route selection. Child Care Health Dev. 2012;38:280-286. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Saltz E, Perry A, Cabral R. Attacking the personal fable role-play and its effect on teen attitudes toward sexual abstinence. Youth Soc. 1994;26:223-242. [Google Scholar]

- 38. Out JW, Lafreniere KD. Baby think it over: using role-play to prevent teen pregnancy. Adolescence. 2001;36:571-582. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Greene K, Rubin DL, Hale JL, Walters LH. The utility of understanding adolescent egocentrism in designing health promotion messages. Health Commun. 1996;8:131-152. [Google Scholar]