Abstract

BACKGROUND:

Smoking hookahs is one of the most preventable risk factors for non communicable diseases. It is also considered as the gateway to youth addiction. Planning and training to prevent this health problem is considered an important priority. The aim of this study was to determine the predictive factors for preventing hookah smoking (PHS) in the youth of Sirjan city, based on the protection motivation theory (PMT).

MATERIALS AND METHODS:

This research was a cross-sectional study conducted in 2018, and participants were chosen by simple random sampling. Data were collected by a researcher-made questionnaire which was valid and reliable and was designed based on the PMT constructs. This questionnaire was completed by 280 young people in Sirjan, Iran. Data were analyzed through descriptive statistics, Pearson correlation coefficients, and linear regression.

RESULTS:

Pearson correlation coefficients showed that there was a significant correlation between protection motivation and the structures of the PMT, except for the response cost structure. The strongest correlation was between protection motivation and self-efficacy (r = 0.502) and fear (r = 0.470). The structures of the PMT predicted 36.5% of PHS, and fear (β =0.27) was the strongest predictor of PHS.

CONCLUSION:

The results of this study show that the constructs of the PMT can partially predict PHS. This theory can be used as a tool for designing and implementing educational interventions to prevent hookah smoking among the youth.

Keywords: Hookah, predicting factor, protection motivation theory, youth

Introduction

Today, one of the global health problems is increased tobacco use. It is predicted that tobacco will cause one-third of adult deaths by 2020.[1] Tobacco is consumed in a variety of ways. The use of hookah is an old and common method of its usage. Global statistics indicate that its use has increased and has now become a social phenomenon.[2]

Tobacco smoke includes more than 4000 different chemical substances, which most of them are produced during the burning process and more than 40 of them are carcinogens, such as hydrocarbons and heavy metals.[3] The high density of carbon monoxide, tar, nicotine, and heavy metals in tobacco smoke can cause many diseases such as oral and lung cancer, decreased respiratory function, reduced fertility, and cardiovascular disease. On the other hand, the use of shared oral tubes in hookah smokers causes transmission of infectious diseases such as respiratory infections and herpes.[4]

Smoking hookah has become popular among Iranian youth, especially the 15–24 years old.[5] Young people are the active and productive class of each society and have a prominent role in the future of the country. However, smoking cigarettes and hookahs among the youth can lead to addiction and disease.[6]

Daily, 100 million people smoke hookah in the world, and statistics show a high rate of hookah consumption, especially among adolescents and young people.[7] The study of Dehdari et al. showed that the prevalence of hookah smoking was 40.3% among Iranian students.[8] Another study on high school students in Iran showed that the prevalence of hookah smoking was 34.4% among girls and 51.9% among boys.[9] A study from Turkey showed that the consumption of hookah among nonmedical students was 37.5% and among medical students was 28.6%.[10] Another study from Pakistan showed that the prevalence of hookah smoking in adolescent students aged 14–19 years was 27% and in college students was 54%.[11]

Some researchers think that if appropriate educational programs and evaluations are developed, protection motivation behaviors can be promoted.[12] One of the theories which are used to investigate the influencing factors on the motivation of individual behaviors is the protection motivation theory (PMT).[13]

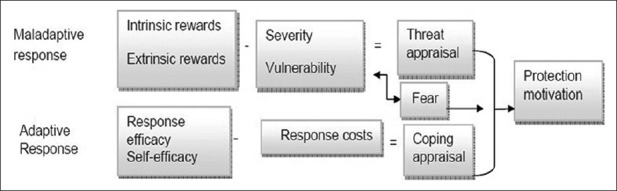

This theory consists of seven constructs which are perceived susceptibility, perceived severity, external and internal rewards, self-efficacy, response efficiency, response costs, and protection motivation. Each of these constructs can be placed in two intermediary cognitive processes which are the coping appraisal and threat appraisal processes [Figure 1].[14]

Figure 1.

The protection motivation theory

Appraisal of the health threat and appraisal of the coping responses result in the intention to perform adaptive responses (a protection motivation) or may lead to maladaptive responses. Maladaptive responses are those that place an individual at health risk and lead to negative consequences such as smoking.[15]

The coping appraisal process is the sum of self-efficacy and response efficiency minus the response cost. Thus, increasing self-efficacy and response efficiency and reducing the response cost will increase “coping appraisal.” Self-efficacy and response efficiency increase the likelihood of choosing adaptive responses, whereas cost responses can reduce adaptive responses. The sum of the two intermediary processes creates the motivation for protection and behavior.[16]

A study done by Yan et al. in China showed that sensitivity, severity, external and internal rewards, self-efficacy, and response cost were, respectively, the most important determinants of intention to smoke cigarettes and the smoking behavior.[17] The results of another study done by Sabahy et al. in Iran showed that there was a significant relationship between attitude and social acceptance, with protection motivation toward hookah use among students.[18] The results of Fakhari et al. showed that a positive attitude toward smoking was associated with students’ transition to hookah smoking status.[19]

Studies about hookah smoking and the predictive factors of hookah smoking are limited. Therefore, because of the increased use of hookah among the youth in recent years, studying the reasons for its increase and popularity among the youth and adolescence is an important issue and requires more research.

Most of the previous studies were interventional and focused on people addicted to hookah or target groups such as women and students[4] but this study focused on adolescent tendencies and predictive factors in hookah smoking, and the results can be used to design interventions for this target group. The aim of this study was to investigate the predictive factors for preventing hookah smoking (PHS) among the youth, in Sirjan city, based on the PMT.

Materials and Methods

Participants and sampling method

This cross-sectional study was conducted in 2018, in Sirjan, Iran. Two-hundred and eighty adolescent males and females were randomly selected as participants in this study. Sample size was estimated according to parameters from a similar study[20] in which the maximum value of the constructs’ standard deviation was 1.7. The acceptable error was assumed to be 0.2, and Type I error was assumed 0.05. The minimum sample size calculated was 278; however, 280 people were chosen in this study.

After listing the health centers of Sirjan city, two centers were randomly selected as the study group. Then, the list of youths which were covered by these two health centers in Sirjan city was extracted, and 280 participants were randomly selected through simple random sampling. The researcher-made questionnaire was completed by the participants in the health centers.

The inclusion criteria were individuals’ willingness to participate in the study, age between 12 and 18 years, living in Sirjan for more than 6 months, and lack of mental disorders including depression (determined by self-report and chart review). The exclusion criteria were drug addiction, not living in Sirjan, and unwillingness to participate in the research. Drug addicts were excluded because this study was about primary prevention, which was not possible to study on people who were already addicted.

Data collection tools

The questionnaire consisted of three parts. The first part contained demographic information with 11 questions about age, gender, marital status, education, father's education, mother's education, father's use of hookah, mother's use of hookah, friend's use of hookah, hookah consumption by themselves, the first place of hookah use, and the sources of information about the harms of hookah.

The second part consisted of eight multiple choice questions about knowledge, and the third part included 64 questions related to constructs of the PMT.[21]

In the knowledge part, the yes option got a score of 2 and “I don’t know” and “no” got a score of 1. The range of the knowledge score was from 8 to 16.

The questions related to the PMT were based on a 5-point Likert scale. Participants had to choose from strongly agree to strongly disagree, and the scores were from 1 to 5. Based on the meaning of the phrases, some questions were scored the opposite way.

The structures of the PMT were perceived sensitivity (8 questions, range: 8–40), perceived severity (8 questions, range: 8–40), internal and external rewards (9 questions, range: 9–45), self-efficacy (8 questions, range: 8–40), response efficiency (8 questions, range: 8–40), response cost (8 questions, range: 8–40), fear (8 questions, range: 8–40), and protection motivation (7 questions, range: 7–35).

The questionnaire was sent to ten health education, epidemiology, and psychiatry experts, to determine its content and face validity. The edited version of the questionnaire was prepared after receiving their comments about the clarity, necessity, relevance, and comprehensiveness of the questions. Some ambiguous, irrelevant, and vague phrases were removed, and some other phrases were corrected.

In order to determine the internal reliability of the questionnaire, 30 individuals were asked to complete the questionnaire, and a 0.7 or higher Cronbach's alpha was considered acceptable. In order to examine external reliability, test–retest was done in 2-week intervals by 30 youth individuals who were not included in the study. The results are in Table 1.

Table 1.

The internal reliability index (Cronbach’s alpha coefficient) and external reliability index (test-retest coefficients) of the questionnaire

| Model structure | Number of questions | Cronbach’s alpha coefficient | Test-retest coefficient (r) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Perceived susceptibility | 8 | 0.91 | 0.89 |

| Perceived severity | 8 | 0.87 | 0.86 |

| Internal and external rewards | 9 | 0.89 | 0.91 |

| Response costs | 8 | 0.79 | 0.81 |

| Response efficiency | 8 | 0.89 | 0.83 |

| Self-efficiency | 8 | 0.82 | 0.84 |

| Fear | 8 | 0.84 | 0.86 |

| Protection motivation | 7 | 0.85 | 0.81 |

Ethical considerations

This study was approved by the Ethics Committee of Shahid Sadoughi University of Medical Sciences (Ethics Code: IR.SSU.SDH.REC.1396.134). The aim of the study was explained for the participants, and informed consent was inquired from all participants and their parents.

Data analysis

Before statistical analysis, the normal distribution of quantitative variables was checked by the Kolmogorov–Smirnov test. Data were analyzed by SPSS version 20 software (IBM, Armonk, NY, USA). Descriptive statistics (frequency and percentage) were reported, and Pearson correlation and linear regression tests were performed.

Results

The participants of this study were 280 young people with a mean age of 15.6 ± 3.82. Less than half (48.9%) were in the 12–18-year-old age group and 51.1% were in the 18–24-year-old age group. The mean age of the participants was 18.06 ± 3.82. One-hundred and twenty-six (45%) were male and 154 (55%) were female. Two-hundred and sixteen participants (77.1%) were single and 64 (22.9%) were married. In terms of education, 2 (0.7%) were illiterate, 10 (3.6%) had elementary school education, 108 (38.6%) had middle school education, 125 (44.6%) had a high school diploma, and 35 (12.5%) had higher education. Most of the parents had high school education.

The results showed that 98 adolescents (35%) sometimes smoked, 26 (9.3%) always smoked, and 156 (55.7%) had never smoked hookah. Furthermore, 179 (63.9%) had friends who smoked hookah and 101 (36.1%) did not have friends who smoked hookah.

The results of regression analysis of the demographic factors on PHS showed that age (β = 0.30, P = 0.001), education level (β =0.234, P = 0.002), education level of father (β = 0.175, P = 0.039), maternal education level (β = 0.256, P = 0.003), the individual's hookah smoking (β = −0.34, P = 0.006), father's hookah smoking (β = −0.169, P = 0.006), and friends’ hookah smoking (β = −0.131, P = 0.026) were significantly related to the PMT, so that older participants, those with higher education levels, and those who had parents with higher education levels were more likely to have PHS, but the individual's smoking of hookah or father's or friends’ smoking of hookah was negatively related to PHS [Table 2].

Table 2.

Multiple linear regression analysis of demographic factors affecting preventing hookah smoking

| Variable | β | SE (β) | Standardized β | t | P | 95% CI for B | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Lower | Upper | ||||||

| Final model | Step 4 | ||||||

| Age | 0.25 | 0.06 | 0.30 | 3.88 | <0.001 | 0.012 | 0.38 |

| Level of education | 0.984 | 0.309 | 0.234 | 3.18 | 0.002 | −0.375 | 1.592 |

| Father’s level of education | 0.497 | 0.239 | 0.175 | 2.079 | 0.039 | 0.026 | 0.968 |

| Mother’s education level | 0.736 | 0.247 | 0.256 | 2.98 | 0.003 | 0.25 | 1.22 |

| The individual’s hookah smoking status | −1.7 | 0.30 | −0.34 | −5.59 | <0.001 | −2.30 | −1.10 |

| Father’s hookah smoking status | −0.895 | 0.322 | −0.169 | −2.77 | 0.006 | −0.26 | −1.53 |

| Friend’s hookah smoking situation | −0.883 | 0.393 | −0.131 | −2.24 | 0.026 | −1.65 | −0.109 |

CI: Confidence interval, SE: Standard error

The study variables were normal, and Pearson correlation was used to investigate the correlation between the constructs of the PMT. The results showed that there was a strong and significant correlation between perceived susceptibility, perceived severity, and fear. There were positive correlations between PHS and perceived susceptibility (r = 0.324, P ≤ 0.001), perceived severity (r = 0.344, P ≤ 0.001), response efficiency (r = 0.441, P ≤ 0.001), self-efficacy (r = 0.502, P = 0.001), and fear (r = 0.470, P = 0.001) but negative correlations with internal and external rewards (r = −0.115, P ≤ 0.05). Response cost showed no significant correlation with PHS (r = −0.068, P = 0.253) [Table 3].

Table 3.

Matrix of correlation coefficient between protection motivation theory structures and preventing hookah smoking

| PMT constructs | Perceived susceptibility | Perceived severity | Response cost | Response efficacy | Self-efficacy | Rewards | Fear | Protection motivation |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Perceived susceptibility | 1 | |||||||

| Perceived severity | 0.626** | 1 | ||||||

| Response cost | −0.046 | 0.009 | 1 | |||||

| Response efficacy | 0.411** | 0.348* | 0.098 | 1 | ||||

| Self-efficacy | 0.507** | 0.454** | −0.027 | 0.600** | 1 | |||

| Rewards | −0.033 | −0.016 | 0.439** | −0.084 | −0.062 | 1 | ||

| Fear | 0.479** | 0.519** | 0.018 | 0.274** | 0.502** | 0.10 | 1 | |

| Protection motivation | 0.324** | 0.344** | −0.068 | 0.441** | 0.502** | −0.115* | 0.470** | 1 |

*Correlation is significant at the 0.05 level (two-tailed), **Correlation is significant at the 0.01 level (two-tailed). PMT=Protection motivation theory

According to the linear regression test, perceived reward, response efficiency, self-efficacy, and fear predicted more than 36% of PHS variability. Fear (β =0.27) had a more important role than other variables [Table 4].

Table 4.

Multiple linear regression analysis of protection motivation theory constructs effective on preventing hookah smoking

| Variable | β | SE (β) | Standardized β | P | 95% CI for B | R2 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Lower | Upper | ||||||

| Constant | 4.68 | 2.23 | - | 0.037 | 0.29 | 9.07 | 0.365 |

| Perceived susceptibility | 0.04 | 0.059 | 0.046 | 0.49 | −0.07 | 0.15 | |

| Perceived severity | 0.034 | 0.061 | 0.036 | 0.58 | −0.08 | 0.15 | |

| Rewards | −0.10 | 0.044 | −0.126 | 0.023 | 0.01 | 0.18 | |

| Response cost | −0.01 | 0.05 | −0.012 | 0.828 | −0.11 | 0.09 | |

| Response efficacy | 0.20 | 0.053 | 0.24 | <0.001 | 0.103 | 0.31 | |

| Self-efficacy | 0.22 | 0.06 | 0.22 | 0.001 | 0.09 | 0.35 | |

| Fear | 0.23 | 0.05 | 0.27 | <0.001 | 0.13 | 0.33 | |

CI=Confidence interval, SE=Standard error

Furthermore, the results of this study showed that the two intermediary cognitive processes, threat appraisal and coping appraisal, predicted more than 10% of PHS variability, in which the role of coping appraisal was stronger (β =0.32) [Table 5].

Table 5.

Multiple linear regression analysis of the mediation processes (threat appraisal and coping appraisal) of protection motivation theory on preventing hookah smoking

| Variable | β | SE (β) | Standardized β | P | 95% CI for B | R2 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Lower | Upper | ||||||

| Constant | 26.09 | 0.25 | - | <0.001 | 25.59 | 26.59 | 0.103 |

| Threat appraisal | 0.07 | 0.36 | 0.013 | 0.847 | −0.64 | 0.78 | |

| Coping appraisal | 1.85 | 0.38 | 0.32 | <0.001 | 1.1 | 2.6 | |

CI=Confidence interval, SE=Standard error

Discussion

A combination of social, economic, and cultural changes has led to the creation of a risky lifestyle for humankind, and one of these dilemmas is the increasing use of hookah, especially among young people and adolescents.[21] Identifying the effective causes in this phenomenon is necessary.[6] Therefore, the aim of this study was to investigate the predictive factors for PHS among the youth, in Sirjan city, based on the PMT.

This study showed that 44.3% of the participants smoked hookah which is an alarming number. In a study conducted by Dehdari et al. on Iranian students, the prevalence of hookah smoking was 40.3%.[8] Another study conducted on high school students in Tehran showed the rates of hookah smoking were 34.4% in girls and 51.9% in boys, and the mean was 43%.[9] A study in Turkey showed that hookah consumption was 37.5% among nonmedical students and 28.6% among medical students.[10]

Several factors are involved in the increased rates of smoking hookah. The most important reasons for its use from the public's point of view are people's lack of knowledge about its harms, the availability of various tobacco flavors, its low costs, social acceptance, and youths attempt to gain personal and social identity, enjoyment, and self-esteem.[22,23] From the World Health Organization's point of view, misconceptions about the safe and harmless nature of hookah are the main reasons of its consumption.[24]

The findings of the study showed that age, level of education, father's level of education, mother's level of education, hookah smoking of the participant, hookah smoking status of the father, and the hookah smoking status of the friends were the most important influencing factors on PHS.

The results showed that there was a significant relationship between age and PHS, so that protection motivation increases as age increases. This can be due to knowledge increase overtime. The results of this study are consistent with the results of a study on non secure driving in Yazd, Iran,[25] which showed that with increasing age, the risk of dangerous driving decreased; however, the results of the Lowe et al.'s study on Australian students showed that by increasing age, sun protection behaviors decreased,[26] which contradicts the results of this study.

In this study, individual education and parenting education were significantly related to PHS. The results of Morowati Sharifabad et al.'s study[27] and Tazval et al.'s study[28] are consistent with the results of this study. Their finding suggested that as education increases, PHS increases as well.

The findings also showed that the hookah smoking of participants, their parents, and their friends led to less PHS. These findings are consistent with the results of the study done by Yan et al. on predictors of smoking in China.[17] A study on Iranian students also showed that having friends who smoke hookah had a significant relation with smoking cigarette and hookah in the individual,[5] which is consistent with the current study.

The results of Pearson correlation coefficients showed that there was a significant correlation between PHS and all constructs, except response cost structures, and the strongest correlation was seen in self-efficacy (r = 0.502) and fear (r = 0.470).

The results showed that there was a positive and significant relation between PHS and perceived susceptibility, which suggests that if people see themselves at risk of losing their health, their protection motivation will be greater. These results were consistent with the results of Babazadeh et al.[29] and Mohammadi et al.[30]

The results also showed that there was a significant positive correlation between PHS and perceived severity. These findings suggest that if people become aware of the consequences and harms of hookah smoking on the health of themselves and those around them, protection motivation will increase. These findings are consistent with Tazval et al.'s study[28] but are contradicted by Hadi.[31]

In this study, there was a positive and significant correlation between PHS and fear, which indicates that fear can be an intermediary element in protection motivation, and if one is afraid of smoking hookahs and its complications, his/her motivation will increase for not smoking hookah. This finding is consistent with the results of various studies.[25,27]

As it is expected, in this study, there was a positive and significant correlation between self-efficacy and response efficacy structures with PHS. The results of several studies are consistent with the results of this study.[27,32] The positive correlation suggests that a person with a higher self-efficacy can act consistently (e.g. not smoke hookah) against a health risk (hookah), and this can reduce health risks, protect his health, and prevent the consequences of inappropriate behavior (hookah smoking). Therefore, in designing educational interventions, emphasis on self-efficacy and effectiveness of the suggested responses is essential to alleviate threats.

There was a significant negative correlation between perceived rewards and PHS in this study. This means as the perceived reward of the incompatible behaviors increases, the individual's intention to perform consistent behavior decreases, and the individual will be less motivated to refrain from that behavior. These results are consistent with the results of similar studies.[25,33]

According to the results of this study, the protective motivation theory constructs can predict 36.5% of the PHS changes in the youth. Among the structures, rewards, self-efficacy, response efficiency, and fear were significant predictors of protection motivation, and fear was the strongest predictor. This suggests that if one feels fear of hookah smoking and its harms, his motivation for not smoking hookah will increase, which is consistent with the results of a study done by Sharifirad et al.[34] These results indicate that inducing fear must be included in educational interventions to increase protection motivation.

The results also showed that intermediary cognitive processes (threat appraisal and coping appraisal) were able to explain 10.3% of the variance of PHS. Coping appraisal predicts protection motivation more than threat appraisal. In contrary, in the study done by Plotnikoff et al., threat appraisal and next coping appraisal were strong predictors for the intention of doing protective behaviors.[32] Floyd et al., in a meta-analysis, based on the PMT, in 20 health fields showed that the coping appraisal variables were generally more powerful predictors of motivation and behavior.[35] These results indicate that as the abilities and responses of a person for coping with perceived threat increases, the probability of motivating and protecting health behaviors increases as well.

Conclusion

The results of this study show the effectiveness of the PMT in predicting PHS in the youth. This study also showed the alarmingly high prevalence of hookah smoking in the target group. The effective constructs of this theory can be used in designing tools and implementing and evaluating educational interventions to prevent hookah smoking among the youth.

One of the limitations of this study was that data collection was done through self-report. Although the questionnaires were kept confidential and anonymous, there still is a possibility of response bias. Furthermore, this study was conducted on a specific age group and the results might not be generalizable to other age groups.

Financial support and sponsorship

This study was financially supported by the Research Deputy of Shahid Sadoughi University of Medical Sciences.

Conflicts of interest

There are no conflicts of interest.

Acknowledgment

Researchers would like to thank the Research Deputy of Shahid Sadoughi University of Medical Sciences which financially supported this research and all of the individuals who participated in this study.

References

- 1.Samet JM. Tobacco smoking: The leading cause of preventable disease worldwide. Thorac Surg Clin. 2013;23:103–12. doi: 10.1016/j.thorsurg.2013.01.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Lovato C, Watts A, Stead LF. Impact of tobacco advertising and promotion on increasing adolescent smoking behaviours. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2011;10:CD003439. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD003439.pub2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Coleman BN, Johnson SE, Tessman GK, Tworek C, Alexander J, Dickinson DM, et al. “It's not smoke. It's not tar. It's not 4000 chemicals. Case closed”: Exploring attitudes, beliefs, and perceived social norms of e-cigarette use among adult users. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2016;159:80–5. doi: 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2015.11.028. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Sadeghi R, Mahmoodabad SS, Fallahzadeh H, Rezaeian M, Bidaki R, Khanjani N. A systematic review about educational interventions aimed to prevent hookah smoking. Int J Ayurvedic Med. 2019;10:14–21. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Pirdehghan A, Aghakoochak A, Vakili M, Poorrezaee M. Determination of predicting factors of hookah smoking among pre-university students in Yazd in 2015. Pajouhan Sci J. 2016;15:28–36. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Arazi H, Hosseini R, Rahimzadeh M. Comparison of cigarette and hookah smoking between physical education and non-physical education students. J Jahrom Univ Med Sci. 2013;11:57–63. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Minaker LM, Shuh A, Burkhalter RJ, Manske SR. Hookah use prevalence, predictors, and perceptions among Canadian youth: Findings from the 2012/2013 youth smoking survey. Cancer Causes Control. 2015;26:831–8. doi: 10.1007/s10552-015-0556-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Dehdari T, Jafari A, Joveyni H. Students’ perspectives in Tehran University of Medical Sciences about factors affecting smoking hookah. Razi J Med Sci. 2012;19:17–24. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Momtazi S, Rawson R. Substance abuse among Iranian high school students. Curr Opin Psychiatry. 2010;23:221–6. doi: 10.1097/YCO.0b013e328338630d. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Poyrazoǧlu S, Sarli S, Gencer Z, Günay O. Waterpipe (narghile) smoking among medical and non-medical university students in Turkey. Ups J Med Sci. 2010;115:210–6. doi: 10.3109/03009734.2010.487164. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Anjum Q, Ahmed F, Ashfaq T. Knowledge, attitude and perception of water pipe smoking (Shisha) among adolescents aged 14-19 years. J Pak Med Assoc. 2008;58:312–7. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Agha MT, Eftekhar H, Mohammad K. Application of health belief model to behavior change of diabetic patients. Payesh. 2005;4:263–9. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Crossler RE, editor. Protection Motivation Theory: Understanding Determinants To Backing up Personal Data. 43rd Hawaii International Conference on System Sciences. IEEE. 2010 [Google Scholar]

- 14.Tsai HS, Jiang M, Alhabash S, LaRose R, Rifon NJ, Cotten SR. Understanding online safety behaviors: A protection motivation theory perspective. Comput Secur. 2016;59:138–50. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Rippetoe PA, Rogers RW. Effects of components of protection-motivation theory on adaptive and maladaptive coping with a health threat. J Pers Soc Psychol. 1987;52:596–604. doi: 10.1037//0022-3514.52.3.596. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Norman P, Conner M. Predicting and changing health behaviour: Future directions. Predicting Health Behav. 2005;2:324–71. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Yan Y, Jacques-Tiura AJ, Chen X, Xie N, Chen J, Yang N, et al. Application of the protection motivation theory in predicting cigarette smoking among adolescents in China. Addict Behav. 2014;39:181–8. doi: 10.1016/j.addbeh.2013.09.027. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Sabahy AR, Divsalar K, Nakhaee N. Attitude of university students towards waterpipe smoking: Study in Iran. Addict Health. 2011;3:9–14. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Fakhari A, Mohammadpoorasl A, Nedjat S, Sharif Hosseini M, Fotouhi A. Hookah smoking in high school students and its determinants in Iran: A longitudinal study. Am J Mens Health. 2015;9:186–92. doi: 10.1177/1557988314535236. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Macdonell K, Chen X, Yan Y, Li F, Gong J, Sun H, et al. A protection motivation theory-based scale for tobacco research among Chinese youth. J Addict Res Ther. 2013;4:154. doi: 10.4172/2155-6105.1000154. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Mazloomy Mahmoodabad SS, Sadeghi R, Fallahzadeh H, Rezaeian M, Bidaki R, Khanjani N. Validity and reliability of the preventing hookah smoking (PHS) questionnaire in adolescents based on the protection motivation theory. Int J Pediatr. 2018;6:8327–37. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Martinasek MP, McDermott RJ, Martini L. Waterpipe (hookah) tobacco smoking among youth. Curr Probl Pediatr Adolesc Health Care. 2011;41:34–57. doi: 10.1016/j.cppeds.2010.10.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Sadeghi R, Mahmoodabad SS, Fallahzadeh H, Rezaeian M, Bidaki R, Khanjani N. Readability and suitability assessment of adolescent education material in preventing hookah smoking. Int J High Risk Behav Addiction. 2019;8:e83117. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Jahanpour F, Vahedparast H, Ravanipour M, Azodi P. The trend of hookah use among adolescents and youth: A qualitative study. J Qual Res Health Sci. 2015;3:340–8. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Morowati Sharifabad MA, Momeni Sarvestani M, Barkhordari Firoozabadi A, Fallahzadeh H. Predictors of unsafe driving in Yazd city, Based on protection motivation theory in 2010. Horizon Med Sci. 2012;17:49–59. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Lowe JB, Borland R, Stanton WR, Baade P, White V, Balanda KP. Sun-safe behaviour among secondary school students in Australia. Health Educ Res. 2000;15:271–81. doi: 10.1093/her/15.3.271. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Zare Sakhvidi MJ, Zare M, Mostaghaci M, Mehrparvar AH, Morowatisharifabad MA, Naghshineh E. Psychosocial predictors for cancer prevention behaviors in workplace using protection motivation theory. Adv Prev Med. 2015;2015:467498. doi: 10.1155/2015/467498. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Tazval J, Ghafari M, Mohtashami Yeganeh F, Babazadeh T, Rabati R. Efficiency of protection motivation theory on prediction of skin cancer and sunlight preventive behaviors in farmers in Ilam county. J Health. 2016;7:656–67. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Babazadeh T, Nadrian H, Banayejeddi M, Rezapour B. Determinants of skin cancer preventive behaviors among rural farmers in Iran: An application of protection motivation theory. J Cancer Educ. 2017;32:604–12. doi: 10.1007/s13187-016-1004-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Mohammadi S, Baghiani Moghadam MH, Noorbala MT, Mazloomi SS, Fallahzadeh H, Daya A. Survey about the role of appearance concern with skin cancer prevention behavior based on protection motivation theory. J Dermatol Cosmetic. 2010;1:70–7. [Google Scholar]

- 31.Hadi L. Study of determinants of lung cancer protective behaviors in Esfahan steel company workers based on protection motivation theory. J Toloo E Behdasht. 2015;16:67–80. [Google Scholar]

- 32.Plotnikoff RC, Trinh L, Courneya KS, Karunamuni N, Sigal RJ. Predictors of aerobic physical activity and resistance training among Canadian adults with type 2 diabetes: An application of the protection motivation theory. Psychol Sport Exerc. 2009;10:320–8. [Google Scholar]

- 33.Baghianimoghaddam MH, Mohammadi S, Norbala MT, Mazloomi SS. The study of factors relevant to skin cancer preventive behavior in female high school students in Yazd based on protection motivation theory. Knowledge and Health. 2010;5:10–15. [Google Scholar]

- 34.Sharifirad G, Yarmohammadi P, Morowati SM, Rahayi Z. The status of preventive behaviors regarding influenza (A) H1N1 pandemic based on protection motivation theory among female high school students in Isfahan, Iran. Health system research. 2011;7:108–117. doi: 10.4103/2277-9531.127556. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Floyd DL, Prentice†Dunn S, Rogers RW. A meta-analysis of research on protection motivation theory. J Appl Soc Psychol. 2000;30:407–29. [Google Scholar]