Abstract

Hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC) is a significant health burden worldwide and its pathogenesis remains to be fully elucidated. One of the means by which long non-coding (lnc)RNAs regulate gene expression is by interacting with micro (mi)RNAs and acting as competing endogenous (ce)RNAs. lncRNAs have important roles in various diseases. The aim of the present study was to examine the potential roles of lncRNAs in HCC. The RNA expression profiles of 21 paired tissues of HCC and adjacent non-tumor tissues were obtained from the Gene Expression Omnibus database. The differentially expressed RNAs were analyzed using the DESeq package in R. Expression validation and survival analysis of selected RNAs were performed using Gene Expression Profile Interactive Analysis and/or Kaplan-Meier Plotter. The target genes of the miRNAs were predicted using lncBase or TargetScan. Functional analyses were performed using the Database for Annotation, Visualization and Integrated Discovery, and regulatory networks were determined using Cytoscape. Long intergenic non-protein coding RNA 1093 (LINC01093) was identified as one of the most significantly downregulated lncRNAs in HCC tissues. Downregulated expression of LINC01093 was associated with poor prognosis. A ceRNA network involving LINC01093, miR-96-5p and zinc finger AN1-type containing 5 (ZFAND5) was established. According to functional analyses, NF-κB signaling was implicated in the regulatory network for HCC. The present study revealed that a LINC01093/miR-96-5p/ZFAND5/NF-κB signaling axis may have an important role in the pathogenesis of HCC, and further investigation of this axis may provide novel insight into the development and progression of HCC.

Keywords: hepatocellular carcinoma, long non-coding RNA, microRNA, The Cancer Genome Atlas, competing endogenous RNA

Introduction

Liver cancer was estimated to be the sixth most common cancer type and the fourth leading cause of cancer-associated death worldwide in 2018, and it has been reported that hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC) is the most common subtype, accounting for 75–85% of all primary cases of liver cancer (1). However, the underlying molecular mechanisms of HCC development remain to be fully elucidated, and the high incidence of metastasis and recurrence frequently results in poor prognosis for patients with HCC, even following curative therapy (2). Therefore, it is imperative to identify novel diagnostic and prognostic biomarkers and efficacious therapeutic targets.

Abnormalities in gene transcription and translation serve important roles in the development and progression of HCC. Developments in biotechnology, including genome sequencing and bioinformatics, have facilitated the study of the tumor transcriptome and proteome, which has advanced the current understanding of the underlying molecular mechanisms of HCC. Genome sequencing has indicated that the human genome is comprised of <2% protein-coding genes and >90% of the genome is transcribed as non-coding RNA (ncRNA) (3). Numerous classes of ncRNA have been identified and demonstrated to be associated with cancer, including long-ncRNAs (lncRNAs), microRNAs (miRNAs), small nucleolar RNAs and PIWI-interacting RNAs (4–7), among which lncRNAs and miRNAs have been most extensively studied. lncRNAs are >200 nucleotides long and participate in multiple biological functions, including epigenetics, nuclear import, alternative splicing, RNA decay and translation (5). miRNAs are small ncRNAs of 18–25 nucleotides in length that regulate the expression of multiple mRNAs by reducing the stability and inhibiting the translation of mRNAs at the post-transcriptional level (8). miRNAs restrain the expression of target genes, whereas lncRNAs may competitively combine with miRNAs to promote the expression of target genes; in this interaction, they are commonly referred to as competing endogenous RNAs (ceRNAs) (9). Although previous studies have reported on the roles of lncRNAs and miRNAs in HCC (10–14), the specific underlying mechanisms associated with the initiation and progression of HCC remain to be fully elucidated (15).

In the present study, profiles of differentially expressed lncRNAs between HCC tissues and adjacent normal tissues were determined from high-throughput RNA sequencing data.

Bioinformatics and survival analysis using integrated mining of data from The Cancer Genome Atlas (TCGA) was performed (16). Simultaneously, the regulatory mechanisms and signaling pathways in HCC were predicted and their differential diagnostic performance was analyzed to provide a potentially valuable reference for the early diagnosis, effective treatment and prognosis of patients with HCC.

Materials and methods

RNA-sequencing (seq) data retrieval and processing

The GSE94660 dataset was obtained from the Gene Expression Omnibus (GEO), which contains the RNA sequencing data from 21 pairs of tumor and non-neoplastic liver tissues from patients with hepatitis B virus-associated HCC. The normalized gene expression dataset GSE94660 was downloaded from the GEO database (https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/geo/) (17). To identify the differentially expressed genes between tumor and non-tumor tissues, threshold values of a fold change of |1.5| and P<0.05 were used.

Expression level analysis

The expression of lncRNA and mRNA in patients were analyzed using either Gene Expression Profiling Interactive Analysis (GEPIA) (18) or from expression data downloaded from TCGA (16). Expression data of lncRNA in normal tissues were obtained from BioProject (accession no. PRJEB4337; linc01093) (19).

Target prediction and network establishment

To predict potential miRNAs that target candidate lncRNAs, lncBase version 2 (http://carolina.imis.athena-innovation.gr/diana_tools/web/index.php?r=lncbasev2/index) (20) was used with a prediction score of ≥0.95 as the threshold value. The miRNAs identified were further inputted into TargetScan (http://www.targetscan.org/vert_72/) (21) to identify their potential target genes. Targets with a cumulative weighted context score ≤-0.6 that interacted with a differentially expressed gene identified in the GSE94660 dataset were selected to establish an interaction network with candidate miRNAs and lncRNA using Cytoscape 3.40 (22).

Interactome identification and functional enrichment analysis

Proteins that physically interacted with zinc finger AN1-type containing 5 (ZFAND5) were identified from BioGRID (https://thebiogrid.org/) (23), an interaction repository containing 1,623,645 protein and genetic interactions in a number of species. Gene ontology (GO) (24) and reactome pathway enrichment analyses of the ZFAND5 interactome were performed using the Database for Annotation, Visualization and Integrated Discovery (DAVID; http://david.abcc.ncifcrf.gov/) (25), which provides a comprehensive set of functional annotation tools for researchers to understand the biological contexts surrounding a large number of interacting genes.

Survival analysis

To assess the prognostic value of the lncRNAs and genes identified, GEPIA and Kaplan-Meier plotter (http://kmplot.com/analysis/) (26) were used. Overall survival of patients with HCC was analyzed using a Kaplan-Meier plot based on the median expression levels of each gene. The hazard ratio (HR) and 95% confidence intervals were calculated and a log-rank test was used to determine whether survival was significantly different between patients with high and low expression of each gene in their HCC tissues.

Results

Downregulated expression of LINC01093 in HCC tissues is associated with poor prognosis

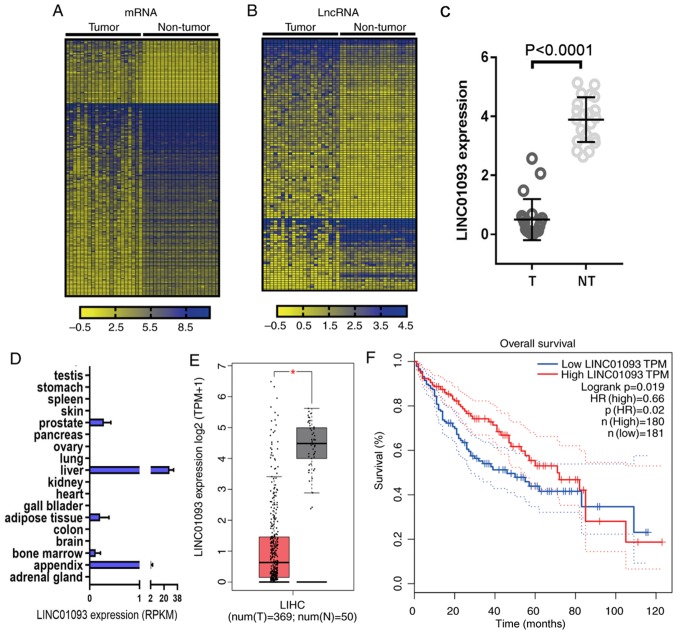

The GSE94660 dataset from GEO database was analyzed, and heatmaps were generated to present the differentially expressed genes (Fig. 1A) and lncRNAs (Fig. 1B) with a fold change ≥|1.5| and P<0.05. LINC01093 (27,28) was the most significantly downregulated lncRNA (Fig. 1C). The expression profile of LINC01093 in normal tissues was obtained from BioProject, and LINC01093 was almost exclusively expressed in normal liver tissue in humans (Fig. 1D). To validate these results, the expression of LINC01093 in HCC tissues and adjacent non-tumor tissues was analyzed using the GEPIA database. The results indicated that LINC01093 was significantly downregulated in tumor tissues compared with that in normal tissues (Fig. 1E). Survival analysis using Kaplan-Meier plotter suggested that low expression levels of LINC01093 in patients with HCC predicted a less favorable prognosis (Fig. 1F).

Figure 1.

LINC01093 is downregulated in HCC tissues and positively associated with patient prognosis. Heat maps for (A) mRNAs and (B) lncRNAs deregulated in HCC vs. adjacent non-tumor tissues. (C) Expression of LINC01093 in HCC tissues and adjacent non-tumor tissues. (D) Expression of LINC01093 across normal organs and tissues. (E) Validation of LINC01093 expression in HCC tissues (n=369) and adjacent non-tumor tissues (n=50) using data from The Cancer Genome Atlas. The tumor tissues are presented on the left and the non-tumor tissues on the right. *P<0.05. (F) Kaplan-Meier analysis of overall survival for patients with HCC with high vs. low LINC01093 expression. Dotted lines stand for the 95% CI for the HR. HCC, hepatocellular carcinoma; lncRNA, long non-coding RNA; LINC01093, long intergenic non-protein coding RNA 1093; T, tumor samples; NT, non-tumor tissue samples; HR, hazard ratio; RPKM, reads per kilobase per million mapped reads; TPM, transcripts per million.

LINC01093 is a potential target of miR-96-5p

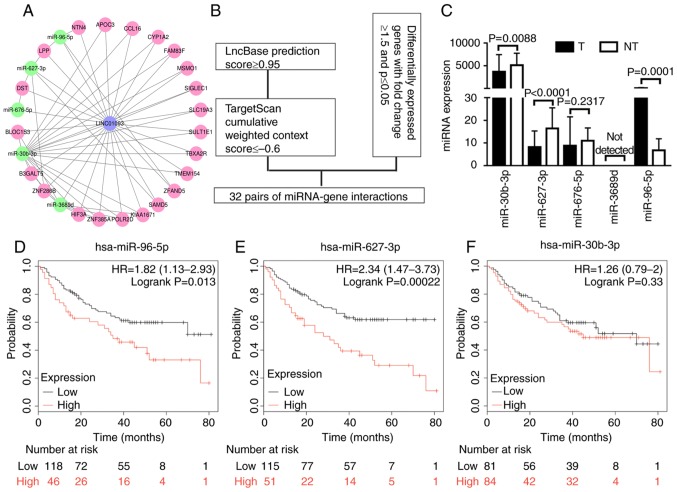

lncRNAs primarily function as ceRNAs; thus, low expression levels of LINC01093 in tumor tissues lead to high expression of target miRNAs. To identify potential miRNAs that interact with LINC01093, the lncBase database was used. By implementing a cutoff prediction score of ≥0.95, five potential miRNAs were identified: miR-30b-3p, miR-627-3p, miR-676-5p, miR-3689d and miR-96-5p. The potential target genes of these miRNAs were predicted using TargetScan and screened with a total context score of ≤0.6 used as the cutoff. Genes identified in TargetScan, which were also differentially expressed in the GSE94660 dataset, were selected as candidate targets. A lncRNA-miRNA-gene network was established (Fig. 2A) with the aforementioned diverse bioinformatics tools (Fig. 2B). The expression levels of the five aforementioned miRNAs were validated using data from TCGA, revealing that three of the miRNAs were significantly differentially expressed between tumor tissues and adjacent non-tumor tissues; among these miRs, miR-96-5p was upregulated in tumor tissues, whereas miR-30b-3p and miR-627-3p were significantly downregulated in tumor tissues (Fig. 2C). The Kaplan-Meier plotter was used to perform survival analysis, and the results indicated that low expression levels of miR-96-5p predicted a favorable prognosis for patients with HCC (Fig. 2D). Although the expression levels were negatively associated with patient prognosis, miR-627-3p was not statistically considered a potential candidate miRNA (Fig. 2E). There was no significant association between the expression of miR-30b-3p and survival outcome (Fig. 2F). These results indicate that miR-96-5p potentially targets LINC01093. The results indicated that miR-96-5p has a tumor suppressor role in HCC by inhibiting LINC01093, and its upregulation is associated with a favorable prognosis regarding survival.

Figure 2.

LINC01093 is a potential target of miR-96-5p. (A) Regulatory network of LINC01093, miRNAs and mRNAs: Blue nodes, LINC01093; green nodes, miRNA; pink nodes, mRNA. (B) Flow chart for the in silico prediction of LINC01093-miRNA-mRNA pairs. (C) Validation of miRNA expression using data from The Cancer Genome Atlas. Kaplan-Meier analysis of overall survival for patients with hepatocellular carcinoma with high vs. low expression of (D) miR-96-5p, (E) miR-627-3p and (F) miR-30b-3p. miRNA, microRNA; hsa, Homo sapiens; LINC01093, long intergenic non-protein coding RNA 1093; T, tumor samples; NT, non-tumor tissue samples; HR, hazard ratio. NTN4, nerve guidance factor 4; APOC3, apolipoprotein C3; CCL16, C-C motif chemokine ligand 16; CYP1A2, cytochrome P450 1A2; FAM83F, family with sequence similarity 83; MSMO1, methylsterol monooxygenase 1; SIGLEC1, sialic acid binding Ig like lectin 1; SLC19A3, solute carrier family 19 member 3; SULT1E1, sulfotransferase family 1E member 1; TBXA2R, thromboxane A2 receptor; TMEM154, transmembrane protein 154; ZFAND5, zinc finger AN1-type containing 5; SMAD5, SMAD family member 5; POLR2D, RNA polymerase II subunit D; ZNF385, zinc finger protein 385A, HIF3A, hypoxia inducible factor 3 subunit α; ZNF286B, zinc finger protein 286B; B3GALT5, β-1,3-galactosyltransferase 5; BLOC1S3, biogenesis of lysosomal organelles complex 1 subunit 3; DST, dystonin; LPP, LIM domain containing preferred translocation partner in lipoma.

ZFAND5 is a candidate target of miR-96-5p

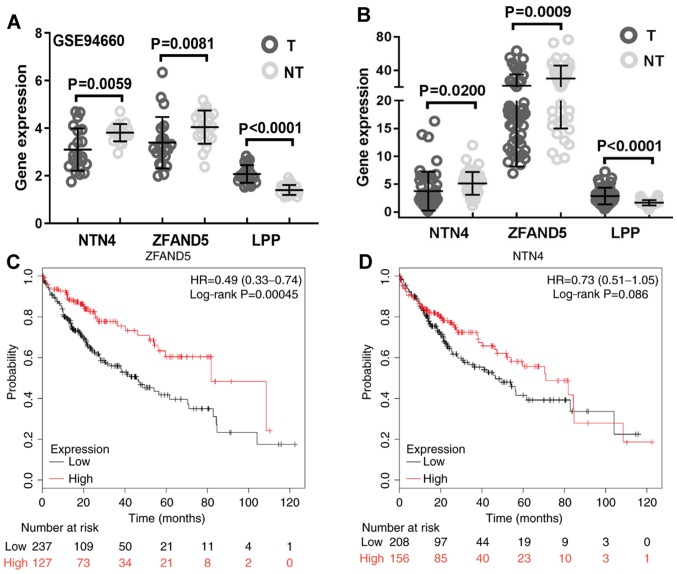

miRNA regulates gene expression in a negative manner; thus, high expression levels of miR-96-5p in the tumor tissue theoretically result in decreased expression of the target gene. To identify the potential targets, expression of previously predicted miR-96-5p target genes were analyzed and the results suggested that the expression levels of netrin 4 (NTN4) and ZFAND5 were lower in HCC tissues compared with those in the adjacent non-tumor tissues (Fig. 3A). LIM domain containing preferred translocation partner in lipoma (LPP) was significantly differentially expressed; however, its expression was upregulated in tumor tissues (Fig. 3A). These results were further validated using data from TCGA, confirming that NTN4 and ZFAND5 were downregulated in HCC tissues (Fig. 3B). NTN4 and ZFAND5 were further subjected to survival analysis, and the results demonstrated that only high expression of ZFAND5 predicted a favorable prognosis for patients with HCC (Fig. 3C), whereas high expression of NTN4 was not predicted to be significantly associated with improved prognosis (Fig. 3D). Therefore, ZFAND5 was selected for further analysis.

Figure 3.

ZFAND5 is a candidate target of miR-96-5p. (A) Expression of selected miR-96-5p target genes. (B) The aberrant expression of the target genes was validated using The Cancer Genome Atlas dataset. Kaplan-Meier analysis of overall survival for patients with hepatocellular carcinoma with high vs. low expression of (C) ZFAND5 and (D) NTN4. ZFAND5, zinc finger AN1-type containing 5; miRNA, microRNA; T, tumor samples; NT, non-tumor tissue samples; HR, hazard ratio; NTN4, netrin 4; LPP, LIM domain containing preferred translocation partner in lipoma.

Functional analysis of the ZFAND5 interactome indicates the significance of NF-κB signaling

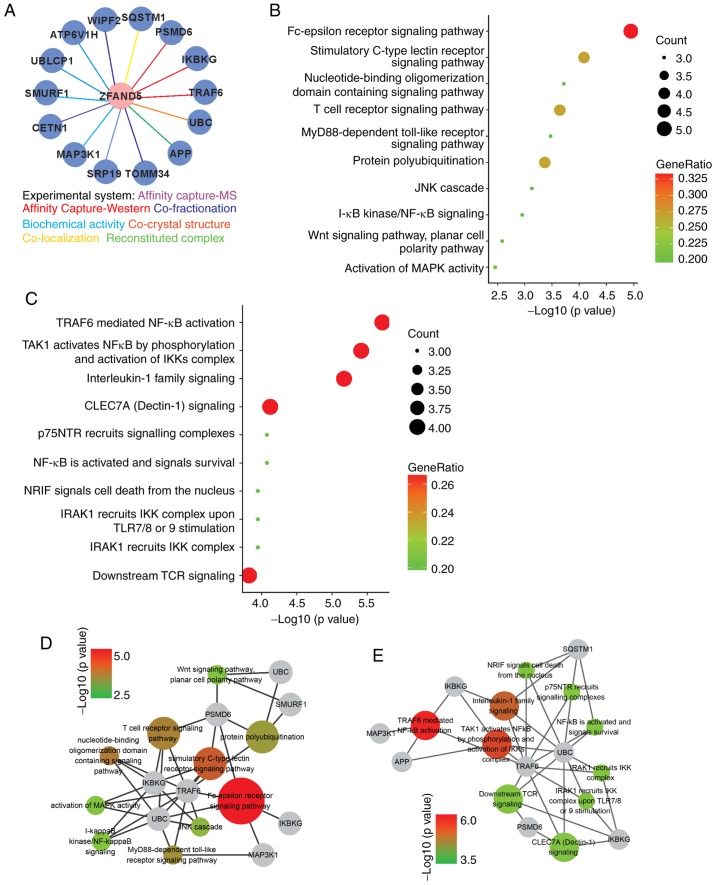

To further explore its function, the interactome of ZFAND5 was determined using BioGRID. This led to the identification of a total of 14 physical interactors with various experimental systems (Fig. 4A). Functional analysis demonstrated that the top 10 enriched GO terms were ‘Fc-epsilon receptor signaling pathway’, ‘stimulatory C-type lectin receptor signaling pathway’, ‘nucleotide-binding oligomerization domain containing signaling pathway’, ‘T cell receptor signaling pathway’, ‘MyD88-dependent Toll like receptor (TLR) signaling pathway’, ‘protein polyubiquitination’, ‘JNK cascade’, ‘inhibitor of NF-κB kinase (IKK)/NF-κB signaling’, ‘Wnt signaling pathway’ and ‘activation of mitogen-activated protein kinase (MAPK) activity’ (Fig. 4B); while the most significantly enriched reactome pathways were tumor necrosis factor receptor associated factor 6 (TRAF6)-mediated NF-κB activation’; MAPK kinase kinase 7 (TAK1) activates NF-κB by phosphorylation and activation of IKKs complex, interleukin-1 family signaling, C-type lectin domain containing 7A (CLEC7A) signaling, nerve growth factor receptor (p75NTR) recruits signaling complexes, NF-κB is activated and signals survival, neurotrophin receptor-interacting factor (NRIF) signals cell death from the nucleus, interleukin 1 receptor associated kinase 1 (IRAK1) recruits IKK complex upon TLR7/8 or −9 stimulation, IRAK1 recruits IKK complex, and downstream T-cell receptor (TCR) signaling (Fig. 4C). A network consisting of the genes involved in the top 10 GO terms was visualized using Cytoscape (Fig. 4D). Similarly, the reactome pathway network is presented in Fig. 4E. Colored nodes represent different GO terms or pathways and the node color represents enrichment significance. Combined GO and pathway analysis indicated that NF-κB signaling had a prominent significance.

Figure 4.

Functional analyses of the ZFAND5 interactome. (A) ZFAND5 interactors identified by different experimental systems. (B) Gene Ontology analysis of ZFAND5 interactors in the category Biological Process. (C) Reactome pathway analysis of ZFAND5 interactors. Visualization of genes involved in (D) Biological Process terms and (E) reactome pathways. The grey nodes indicate genes and other colored nodes represent different GO terms or pathways. The node size and color represent enrichment significance; the larger the node, the higher enrichment significance of the pathway. ZFAND5, zinc finger AN1-type containing 5. SQSTM1, sequestosome 1; PSMD6, proteasome 26S subunit non-ATPase 6; IKBKG, inhibitor of nuclear factor κB kinase regulatory subunit γ; TRAF6, TNF receptor associated factor 6; UBC, ubiquitin C; APP, amyloid β precursor protein; TOMM34, translocase of outer mitochondrial membrane 34; SRP19, signal recognition particle 19; MAP3K1, mitogen-activated protein kinase kinase kinase 1; CETN1, centrin 1; SMURF1, SMAD specific E3 ubiquitin protein ligase 1; UBLCP1, ubiquitin like domain containing CTD phosphatase 1; ATP6V1H, ATPase H+ transporting V1 subunit H; WIPF2, WAS/WASL interacting protein family member 2.

Discussion

HCC is notoriously difficult to treat successfully and is one of the leading causes of cancer-associated death worldwide. To date, the mechanisms underlying the initiation and progression of HCC have remained to be fully elucidated. lncRNAs have been indicated to regulate gene expression and have been implicated in various biological processes and human diseases. RNA-seq is a high-throughput sequencing technique that may reveal the presence and quantity of specific RNAs in a sample, which allows for the analysis of gene expression, alternative gene splicing and gene fusion. RNA-seq has been widely used to identify pathogenesis-associated genes, and to determine potential therapeutic targets in various diseases.

In the present study, the mRNA and lncRNA expression profiles between HCC tissues and adjacent non-tumor tissues from the GSE94660 dataset were compared and it was demonstrated that LINC01093 was significantly downregulated in tumor tissues. Analysis with BioProject indicated that LINC01093 was almost exclusively expressed in the normal adult liver. The expression of LINC01093 was then validated using data from TCGA, which confirmed its downregulation in HCC, and further survival analysis demonstrated that high expression levels of LINC01093 in HCC tissues were associated with a favorable clinical prognosis.

To understand the role of LINC01093 in hepatocellular carcinogenesis, miRNAs that target LINC01093 were predicted and screened. miR-30b-3p, miR-627-3p, miR-676-5p, miR-3689d and miR-96-5p were identified as potential candidates. The expression levels of these five miRNAs were validated using TCGA, and the results demonstrated that miR-30b-3p, miR-627-3p and miR-96-5p were significantly differentially expressed between tumor tissues and non-tumor tissues, but only miR-96-5p was upregulated in tumor tissues. Survival analysis of the three miRNAs was also performed and the results demonstrated that low expression levels of miR-96-5p predicted a favorable prognosis of patients. miR-96-5p has previously been recognized as an oncogenic miRNA in different types of cancer. In bladder cancer, studies revealed that miR-96-5p promoted tumor cell migration and invasion (29). In prostate cancer, it has been reported that miR-96-5p governed tumor progression and disease outcome by targeting a retinoic acid receptor γ network (30). In colorectal cancer, miR-96-5p was indicated to promote tumor invasion through inhibition of reversion-inducing cysteine-rich protein expression (31). In the present study, the results also suggested that miR-96-5p may promote HCC progression and to be associated with poor disease outcome.

Target genes of miR-96-5p were then predicted and screened with a cumulative weighted context score of ≤-0.6, and LPP, NTN4 and ZFAND5 were the identified as target genes among the differentially expressed genes identified in the GSE94660 dataset. These genes were therefore selected as candidate genes. miRNA regulates gene expression in a negative manner, and since miR-96-5p was upregulated in tumor tissues, downregulation of target genes was expected. The expression of the three candidate genes was analyzed, revealing that ZFAND5 and NTN4 had lower expression in tumor tissues compared with that in adjacent non-tumor tissues, whereas LPP was upregulated in HCC tissues, and these results were further confirmed in the TCGA dataset. ZFAD5 and NTN4 were subjected to survival analysis, which revealed that high mRNA expression levels of ZFAND5 were a favorable predictor of patient prognosis.

ZFAND5 is a member of the ZFAND family (28), and studies have revealed that ZFAND5 enhances protein degradation by activating the ubiquitin-proteasome system (32,33). To understand the potential role of ZFAND5 in HCC, proteins that physically interacted with ZFAND5 were obtained from BioGRID, which included 14 interactors identified by 7 different experimental systems. The ZFAND5-interactome was subsequently subjected to functional enrichment analysis. GO analysis revealed that the top 10 biological processes were ‘Fc-epsilon receptor signaling pathway’, ‘stimulatory C-type lectin receptor signaling pathway’, ‘nucleotide-binding oligomerization domain containing signaling pathway’, ‘T cell receptor signaling pathway’, ‘MyD88-dependent TLR signaling pathway’, ‘protein polyubiquitination’, ‘JNK cascade’, ‘IKK/NF-κB signaling’, ‘Wnt signaling pathway’ and ‘activation of MAPK activity’, while the most significantly enriched reactome pathways were ‘TRAF6 mediated NF-κB activation’, ‘TAK1 activates NF-κB by phosphorylation and activation of IKKs complex’, ‘interleukin-1 family signaling’, ‘CLEC7A signaling’, ‘p75NTR recruits signaling complexes’, ‘NF-κB is activated and signals survival’, ‘NRIF signals cell death from the nucleus’, ‘IRAK1 recruits IKK complex upon TLR7/8 or −9 stimulation’, ‘IRAK1 recruits IKK complex’ and ‘downstream TCR signaling’. These results demonstrate that the NF-kB signaling is an important downstream pathway of ZFAND5.

NF-κB serves a well-known function in immune regulation and inflammatory responses, but growing evidence has additionally demonstrated its role in tumorigenesis (34,35). Therefore, NF-κB is frequently considered as the critical link between inflammation and cancer (35–37). It was reported that ZFAND5 inhibits NF-κB activation by interacting with IKKγ (38). Therefore, the present study indicated the role of a LINC01093/miR96-5p/ZFAND5/NF-κB axis in the regulation of HCC development and progression, and further investigations are required to verify these results. Lack of experimental data is a limitation of the present study, and in a further study, in vitro and in vivo experiments will be performed to verify the conclusions that were obtained through the bioinformatics analysis. Through the use of bioinformatics analysis and in vitro and in vivo experiments, novel insight into the development of potential treatments for patients with HCC may be gained.

Acknowledgements

Not applicable.

Funding

This work was supported by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (grant nos. 81372654 and 81672848).

Availability of data and materials

The datasets analyzed during the current study are available in the GEO repository (https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/geo/query/acc.cgi?acc=GSE94660) and the BioProject repository (https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/bioproject?term=PRJEB4337&cmd=DetailsSearch).

Authors' contributions

JZ designed the study and revised the manuscript. YZ and KY performed the GEO database analysis, analysed the data and wrote the manuscript. CH and LL performed bioinformatics analysis. HZ and MH assisted with the collection and analysis of other data. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Ethics approval and consent to participate

Not applicable.

Patient consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

References

- 1.Bray F, Ferlay J, Soerjomataram I, Siegel RL, Torre LA, Jemal A. Global cancer statistics 2018: GLOBOCAN estimates of incidence and mortality worldwide for 36 cancers in 185 countries. CA Cancer J Clin. 2018;68:394–424. doi: 10.3322/caac.21492. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Bodzin AS, Busuttil RW. Hepatocellular carcinoma: Advances in diagnosis, management, and long-term outcome. World J Hepatol. 2015;7:1157–1167. doi: 10.4254/wjh.v7.i9.1157. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Shi X, Sun M, Liu H, Yao Y, Song Y. Long non-coding RNAs: A new frontier in the study of human diseases. Cancer Lett. 2013;339:159–166. doi: 10.1016/j.canlet.2013.06.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Berindan-Neagoe I, Calin GA. Molecular pathways: MicroRNAs, cancer cells, and microenvironment. Clin Cancer Res. 2014;20:6247–6253. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-13-2500. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Bartonicek N, Maag JL, Dinger ME. Long noncoding RNAs in cancer: Mechanisms of action and technological advancements. Mol Cancer. 2016;15:43. doi: 10.1186/s12943-016-0530-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Ng KW, Anderson C, Marshall EA, Minatel BC, Enfield KS, Saprunoff HL, Lam WL, Martinez VD. Piwi-interacting RNAs in cancer: Emerging functions and clinical utility. Mol Cancer. 2016;15:5. doi: 10.1186/s12943-016-0491-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Mannoor K, Liao J, Jiang F. Small nucleolar RNAs in cancer. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2012;1826:121–128. doi: 10.1016/j.bbcan.2012.03.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Holoch D, Moazed D. RNA-mediated epigenetic regulation of gene expression. Nat Rev Genet. 2015;16:71–84. doi: 10.1038/nrg3863. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Zhu C, Cheng D, Qiu X, Zhuang M, Liu Z. Long noncoding RNA SNHG16 promotes cell proliferation by sponging MicroRNA-205 and upregulating ZEB1 expression in osteosarcoma. Cell Physiol Biochem. 2018;51:429–440. doi: 10.1159/000495239. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Lan T, Ma W, Hong Z, Wu L, Chen X, Yuan Y. Long non-coding RNA small nucleolar RNA host gene 12 (SNHG12) promotes tumorigenesis and metastasis by targeting miR-199a/b-5p in hepatocellular carcinoma. J Exp Clin Cancer Res. 2017;36:11. doi: 10.1186/s13046-016-0486-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Dong J, Teng F, Guo W, Yang J, Ding G, Fu Z. lncRNA SNHG8 promotes the tumorigenesis and metastasis by sponging miR-149-5p and predicts tumor recurrence in hepatocellular carcinoma. Cell Physiol Biochem. 2018;51:2262–2274. doi: 10.1159/000495871. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Tu J, Zhao Z, Xu M, Chen M, Weng Q, Wang J, Ji J. LINC00707 contributes to hepatocellular carcinoma progression via sponging miR-206 to increase CDK14. J Cell Physiol. 2019;234:10615–10624. doi: 10.1002/jcp.27737. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Wang YG, Liu J, Shi M, Chen FX. lncRNA DGCR5 represses the development of hepatocellular carcinoma by targeting the miR-346/KLF14 axis. J Cell Physiol. 2018;234:572–580. doi: 10.1002/jcp.26779. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Chen W, You J, Zheng Q, Zhu YY. Downregulation of lncRNA OGFRP1 inhibits hepatocellular carcinoma progression by AKT/mTOR and Wnt/β-catenin signaling pathways. Cancer Manag Res. 2018;10:1817–1826. doi: 10.2147/CMAR.S164911. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Takahashi K, Yan I, Haga H, Patel T. Long noncoding RNA in liver diseases. Hepatology. 2014;60:744–753. doi: 10.1002/hep.27043. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Cancer Genome Atlas Research Network. Weinstein JN, Collisson EA, Mills GB, Shaw KR, Ozenberger BA, Ellrott K, Shmulevich I, Sander C, Stuart JM. The cancer genome atlas pan-cancer analysis project. Nat Genet. 2013;45:1113–1120. doi: 10.1038/ng.2764. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Edgar R, Domrachev M, Lash AE. Gene expression omnibus: NCBI gene expression and hybridization array data repository. Nucleic Acids Res. 2002;30:207–210. doi: 10.1093/nar/30.1.207. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Tang Z, Li C, Kang B, Gao G, Li C, Zhang Z. GEPIA: A web server for cancer and normal gene expression profiling and interactive analyses. Nucleic Acids Res. 2017;45:W98–W102. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkx247. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Ota T, Suzuki Y, Nishikawa T, Otsuki T, Sugiyama T, Irie R, Wakamatsu A, Hayashi K, Sato H, Nagai K, et al. Complete sequencing and characterization of 21,243 full-length human cDNAs. Nat Genet. 2004;36:40–45. doi: 10.1038/ng1285. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Paraskevopoulou MD, Vlachos IS, Karagkouni D, Georgakilas G, Kanellos I, Vergoulis T, Zagganas K, Tsanakas P, Floros E, Dalamagas T, Hatzigeorgiou AG. DIANA-LncBase v2: Indexing microRNA targets on non-coding transcripts. Nucleic Acids Res. 2016;44:D231–D238. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkv1270. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Lewis BP, Burge CB, Bartel DP. Conserved seed pairing, often flanked by adenosines, indicates that thousands of human genes are microRNA targets. Cell. 2005;120:15–20. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2004.12.035. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Smoot ME, Ono K, Ruscheinski J, Wang PL, Ideker T. Cytoscape 2.8: New features for data integration and network visualization. Bioinformatics. 2011;27:431–432. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btq675. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Oughtred R, Stark C, Breitkreutz BJ, Rust J, Boucher L, Chang C, Kolas N, O'Donnell L, Leung G, McAdam R, et al. The BioGRID interaction database: 2019 update. Nucleic Acids Res. 2019;47:D529–D541. doi: 10.1093/nar/gky1079. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Ashburner M, Ball CA, Blake JA, Botstein D, Butler H, Cherry JM, Davis AP, Dolinski K, Dwight SS, Eppig JT, et al. Gene ontology: Tool for the unification of biology. The gene ontology consortium. Nat Genet. 2000;25:25–29. doi: 10.1038/75556. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Huang DW, Sherman BT, Tan Q, Collins JR, Alvord WG, Roayaei J, Stephens R, Baseler MW, Lane HC, Lempicki RA. The DAVID gene functional classification tool: A novel biological module-centric algorithm to functionally analyze large gene lists. Genome Biol. 2007;8:R183. doi: 10.1186/gb-2007-8-9-r183. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Hou GX, Liu P, Yang J, Wen S. Mining expression and prognosis of topoisomerase isoforms in non-small-cell lung cancer by using Oncomine and Kaplan-Meier plotter. PLoS One. 2017;12:e0174515. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0174515. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Mou Y, Wang D, Xing R, Nie H, Mou Y, Zhang Y, Zhou X. Identification of long noncoding RNAs biomarkers in patients with hepatitis B virus-associated hepatocellular carcinoma. Cancer Biomark. 2018;23:95–106. doi: 10.3233/CBM-181424. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Dai M, Chen S, Wei X, Zhu X, Lan F, Dai S, Qin X. Diagnosis, prognosis and bioinformatics analysis of lncRNAs in hepatocellular carcinoma. Oncotarget. 2017;8:95799–95809. doi: 10.18632/oncotarget.21329. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.He C, Zhang Q, Gu R, Lou Y, Liu W. miR-96 regulates migration and invasion of bladder cancer through epithelial-mesenchymal transition in response to transforming growth factor-β1. J Cell Biochem. 2018;119:7807–7817. doi: 10.1002/jcb.27172. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Long MD, Singh PK, Russell JR, Llimos G, Rosario S, Rizvi A, van den Berg PR, Kirk J, Sucheston-Campbell LE, Smiraglia DJ, Campbell MJ. The miR-96 and RARγ signaling axis governs androgen signaling and prostate cancer progression. Oncogene. 2019;38:421–444. doi: 10.1038/s41388-018-0450-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Iseki Y, Shibutani M, Maeda K, Nagahara H, Fukuoka T, Matsutani S, Hirakawa K, Ohira M. MicroRNA-96 promotes tumor invasion in colorectal cancer via RECK. Anticancer Res. 2018;38:2031–2035. doi: 10.21873/anticanres.12442. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Lee D, Takayama S, Goldberg AL. ZFAND5/ZNF216 is an activator of the 26S proteasome that stimulates overall protein degradation. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2018;115:E9550–E9559. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1809934115. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Hishiya A, Iemura S, Natsume T, Takayama S, Ikeda K, Watanabe K. A novel ubiquitin-binding protein ZNF216 functioning in muscle atrophy. EMBO J. 2006;25:554–564. doi: 10.1038/sj.emboj.7600945. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Dolcet X, Llobet D, Pallares J, Matias-Guiu X. NF-kB in development and progression of human cancer. Virchows Arch. 2005;446:475–482. doi: 10.1007/s00428-005-1264-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Marx J. Cancer research. Inflammation and cancer: The link grows stronger. Science. 2004;306:966–968. doi: 10.1126/science.306.5698.966. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Karin M. NF-kappaB as a critical link between inflammation and cancer. Cold Spring Harb Perspect Biol. 2009;1:a000141. doi: 10.1101/cshperspect.a000141. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Karin M. Nuclear factor-kappaB in cancer development and progression. Nature. 2006;441:431–436. doi: 10.1038/nature04870. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Huang J, Teng L, Li L, Liu T, Li L, Chen D, Xu LG, Zhai Z, Shu HB. ZNF216 is an A20-like and IkappaB kinase gamma-interacting inhibitor of NFkappaB activation. J Biol Chem. 2004;279:16847–16853. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M309491200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

The datasets analyzed during the current study are available in the GEO repository (https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/geo/query/acc.cgi?acc=GSE94660) and the BioProject repository (https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/bioproject?term=PRJEB4337&cmd=DetailsSearch).