Abstract

Background

NACHT and WD repeat domain-containing protein 1 (Nwd1) is a member of the innate immune protein subfamily. Nwd1 contributes to the androgen receptor signaling pathway and is involved in axonal growth. However, the mechanisms that underlie pathophysiological dysfunction in seizures remain unclear.

Methods

Biochemical methods were used to assess Nwd1 expression and localization in a mouse model of kainic acid (KA)-induced acute seizures and temporal lobe epilepsy (TLE) patients. Electrophysiological recordings were used to measure the role of Nwd1 in regulating synaptic transmission and neuronal hyperexcitability in a model of magnesium-free-induced seizure in vitro. Behavioral experiments were performed, and seizure-induced pathological changes were evaluated in a KA-induced seizure model in vivo. GluN2B expression was measured and its correlation with Tyr1472-GluN2B phosphorylation was analyzed in primary hippocampal neurons.

Findings

We demonstrated high protein levels of Nwd1 in brain tissues obtained from mice with acute seizures and TLE patients. Silencing Nwd1 in mice using an adeno-associated virus (AAV) profoundly suppressed neuronal hyperexcitability and the occurrence of acute seizures, which may have been caused by reducing GluN2B-containing NMDA receptor-dependent glutamatergic synaptic transmission. Moreover, the decreased activation of Nwd1 reduced GluN2B expression and the phosphorylation of the GluN2B subunit at Tyr1472.

Interpretation

Here, we report a previously unrecognized but important role of Nwd1 in seizure models in vitro and in vivo, i.e., modulating the phosphorylation of the GluN2B subunit at Tyr1472 and regulating neuronal hyperexcitability. Meanwhile, our findings may provide a therapeutic strategy for the treatment of epilepsy or other hyperexcitability-related neurological disorders.

Fund

The funders have not participated in the study design, data collection, data analysis, interpretation, or writing of the report.

Abbreviations: Adeno-associated virus, (AAV); Artificial cerebrospinal fluid, (ACSF); α-amino-3-hydroxy-5-methyl-4-isoxazolepropionic acid receptor-dependent EPSCs, (AMPA-EPSCs); Calcium/calmodulin-dependent protein kinase II, (CaMKII); Excitatory postsynaptic current, (EPSC); Glial fibrillary acidic protein, (GFAP); Kainic acid, (KA); Leucine rich repeat domain containing protein, (NLR); Microtubule associated protein 2, (MAP2); Miniature excitatory postsynaptic currents, (mEPSCs); Miniature inhibitory postsynaptic currents, (mIPSCs); NACHT and WD repeat domain-containing protein 1, (Nwd1); N-methyl-d-aspartate receptor, (NMDAR); NMDAR-mediated EPSCs, (NMDA-EPSCs); Paired-pulse ratio, (PPR); Paroxysmal depolarization shift, (PDS); Spontaneous recurrent seizures, (SRSs); Status epilepticus, (SE); Temporal lobe epilepsy, (TLE)

Keywords: Neuronal hyperexcitability, NACHT and WD repeat domain-containing protein 1, NMDA receptor, Neuronal synaptic transmission, Hippocampus, GluN2B phosphorylation, Cognition

Research in Context.

Evidence before this study

NACHT and WD repeat domain-containing protein 1 (Nwd1) is a member of the NACHT and leucine rich repeat domain containing protein (NLR) family. Nwd1 is widely expressed in various brain regions. Existing research suggests that Nwd1 expression becomes elevated during prostate cancer progression, is associated with various molecular chaperones commonly related to androgen receptor complexes, and eventually modulates androgen receptor signaling. Moreover, Nwd1 is expressed in neural stem/progenitor cells and is most analogous to the apoptosis regulator Apaf1, which may be involved with signaling molecules of axonal outgrowth regulation and apoptosis. However, whether and how it is involved in the pathophysiological process of seizure is not clear. We hypothesize that Nwd1 controls neuronal hyperexcitability.

Added value of this study

In the present study, we provide evidence supporting our hypothesis. We demonstrate that silencing Nwd1 in mice using AAV profoundly suppresses neuronal hyperexcitability in vitro free magnesium models and reduces the occurrence of epileptic seizures induced by KA injection. As a potential mechanism, we demonstrate an increase in Nwd1 expression in brain tissues from epileptic mice and TLE patients, suggesting that these molecules may be associated with human epilepsy. Electrophysiological experiments suggest that Nwd1 downregulation decreases GluN2B-containing NMDAR-mediated glutamatergic synaptic transmission by decreasing the phosphorylation of GluN2B at Tyr1472, which should result in the decreased excitability of neuronal networks.

Implications of all the available evidence

Our results reveal a novel mechanism underlying the biological role of Nwd1 at the synapse and characterize the beneficial effect of Nwd1 in the treatment of epilepsy by suggesting that the downregulation of Nwd1 prolongs the anticonvulsant effect in a manner similar to that produced by anti-epileptic drugs. Our findings may provide a therapeutic strategy for epilepsy or other hyperexcitability-related neurological disorders.

Alt-text: Unlabelled Box

1. Introduction

Seizure is caused by a loss of the balance between excitatory and inhibitory systems, which originates from the hyperexcitability of a large number of neurons in different brain regions, including the cortex and the hippocampus [1,2]. The hippocampus, which is particularly susceptible to seizures, often undergoes structural reorganization, and it is widely used for studying altered epileptiform events and cognitive impairment [[3], [4], [5], [6], [7], [8], [9]]. The N-methyl-d-aspartate receptor (NMDAR) is a major type of glutamate receptors that is widely distributed in the brain and plays a critical role in synaptic function such as cognition and seizures [[10], [11], [12]]. The number and subunit composition of synaptic NMDARs are tightly controlled by neuronal activity. GluN2B signal transduction depends on phosphorylation at its C-terminal tail by the Src-family of nonreceptor protein-tyrosine kinases, which includes Fyn, cyclic AMP-dependent protein kinase, protein kinase C, and calcium/calmodulin-dependent protein kinase II (CaMKII) [[13], [14], [15]]. Mice with a tyrosine to phenyalanine mutation at Tyr1472 exhibit impaired fear-related learning, reduced amygdaloid long-term potentiation [[15], [16], [17]], and an inhibition of the binding of GluN2B to AP-2, resulting in an increase in the levels of the synaptic GluN2B membrane protein [18,19], and the prevention of neuropathic pain by suppression phosphorylation of GluN2B at Tyr1472 [20]. However, less is known about GluN2B phosphorylation at the Tyr1472 site in seizures. Studies have shown that NMDAR subunits and autoantibodies against NMDARs lead to the development of epilepsy in humans [3,21,22], however, NMDAR antagonists failed to emerge as a means for clinical intervention for epilepsy because of the challenge in attaining clinically tolerable doses and/or the technical difficulties in penetrating the blood-brain barrier [23]. Therefore, investigating NMDAR subtype-dependent contributions to seizures is of great interest for understanding the pathology of the disease.

As a member of the innate immune protein subfamily, NACHT- and leucine-rich repeat domain-containing proteins (NLRs) are mainly used as cytoplasmic pattern recognition receptors to recognize cytoplasmic pathogens and endogenous cell damage signals [24,25]. NACHT and WD repeat domain-containing protein 1 (Nwd1) is a member of the NLR family. Nwd1 is expressed in the cerebral cortex, striatum, hippocampal pyramidal layer, and dentate gyrus [26]. Prior research has found that Nwd1 is expressed in neural stem/progenitor cells and is most analogous to the apoptosis regulator Apaf1, which may be involved with signaling molecules of axonal outgrowth regulation and promoting axon growth or apoptosis [26]. However, whether it is involved in the pathophysiological process of seizures is not clear.

Until now, there has been very limited information regarding the relationship between Nwd1 and NMDA receptors. Thus, we aimed to investigate whether Nwd1 modulates neuronal hyperexcitability and GluN2B phosphorylation in seizure models. In the present study, we therefore sought to determine the following: 1) how Nwd1 modulates neuronal hyperexcitability under seizure-inducing conditions; 2) whether and how Nwd1 regulates GluN2B-containing NMDAR-mediated postsynaptic currents in a model of magnesium-free-induced seizure; and 3) how Nwd1 influences the phosphorylation of the GluN2B subunit at Tyr1472 under epileptic conditions.

2. Materials and methods

2.1. Animals and ethics statement

C57BL/6 mice were used for all experiments. The mice were maintained under standard laboratory conditions (controlled temperature: 22 ± 1 °C; 12-h light/dark cycle with lights on from 8:00 a.m. to 8:00 p.m.). Food and water were available ad libitum. All animal procedures were reviewed and approved by the Animal Ethics Committee of Chongqing Medical University and Southern Medical University. Every effort was made to minimize the number of animals used and their suffering.

2.2. Constructs, viral packaging and in vivo stereotaxic injections

shRNA of Nwd1 was constructed and synthesized by Biopharmaceutical Technology Co., Ltd. (Shanghai, China). A recombinant adeno-associated virus (AAV-Nwd1-shRNA-GFP) was produced by co-transfecting 293 T cells with an AAV expression plasmid and packaging the plasmids. Oligonucleotides of 21-base sense and antisense sequences were connected with a hairpin loop followed by a poly A termination signal. The target sequences against mouse Nwd1 that were used are as follows: AAV-Nwd1-shRNA1: 5′-GCTATCACCGATCAGTTATTG-3′ (virus titer: 2.83 × 1012 transducing units (TU)/mL); AAV-Nwd1-shRNA2: 5′-GCCACACACCAGCTCTGTATA-3′ (2.76 × 1012 TU/mL); and AAV-Nwd1- shRNA3: 5′-GCTGAAGATGCACTGCTATGC-3′ (3.20 × 1012 TU/mL). These targeting shRNAs were screened in hippocampal tissue of mice (Fig. S1a–b). The AAV-Nwd1-shRNA1 that effectively knocked down the expression of Nwd1 was chosen for use in the KA-induced seizure model (Fig. S2a; Fig. 7). The sequence of the scrambled shRNA was 5′-TTCTCCGAACGTGTCACGT-3′ (2.88 × 1012 TU/mL). The targeting shRNA and the scrambled shRNA were ligated into an AAV2/9 vector expressing EGFP. An AAV with an empty vector expressing GFP alone (AAV-GFP) was used as the control (5.95 × 1012 TU/mL).

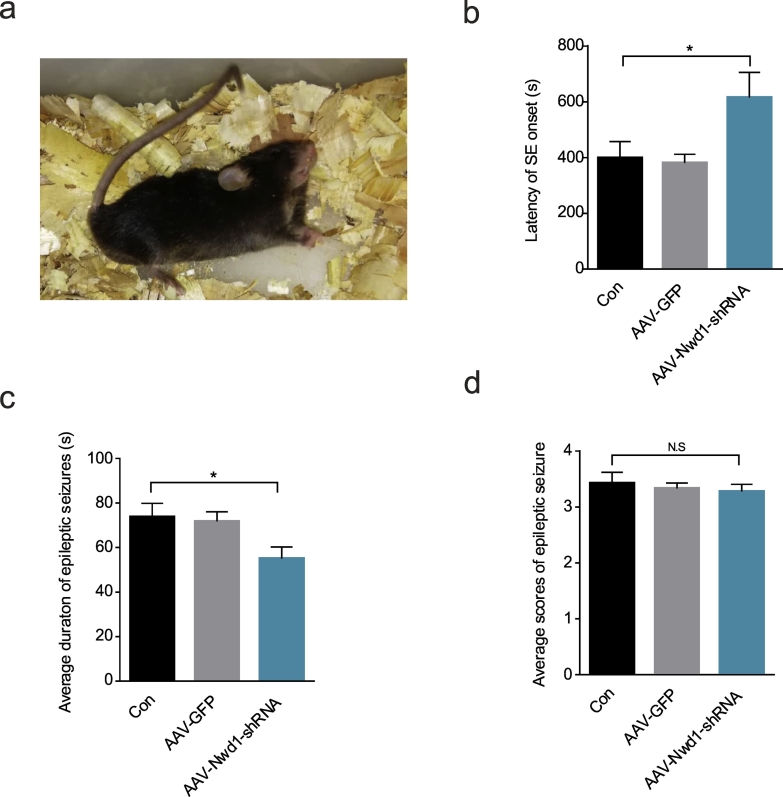

Fig. 7.

Silencing Nwd1 reduces acute seizure severity during KA-induced SE.

(a) A mouse with Racine's stage VI seizure activity showing severe generalized tonic-clonic seizures. (b) A graph showing that the latency of SE onset was prolonged during SE for AAV-Nwd1-shRNA-injected mice compared to control and AAV-GFP-injected mice (n = 6 per group; *P = .0391). (c) A graph showing that, compared to control mice, AAV-Nwd1-shRNA-injected mice exhibited acute seizures of a shorter duration (n = 6 per group; *P = .0464). (d) A graph shows showing that there was no difference in the average behaviour seizure score among all groups (n = 6 per group). The error bars indicate the SEM (*P < 0.05; N.S. represents no significance; ANOVA followed by Tukey's test).

For in vivo viral injections, adult mice (18–25 g, 8–10 weeks old) were anesthetized with 3.5% chloral hydrate and then mounted in a stereotactic headframe containing a mouse adaptor (Reward Life Technology Co., Ltd., China), as described previously [27,28]. The viral vectors were bilaterally injected into the dorsal hippocampus region (anteroposterior (AP) = −1.8 mm, mediolateral (ML) = 1.2 mm, dorsoventral (DV) = 1.5 mm) with a microsyringe (Hamilton, Reno, NV) filled with 2.0 μL of virus. A volume of 1.0 μL of virus was delivered at a speed of 0.1 μL/min. After a 5-min delay, the needle was retracted 0.25 mm, and an additional 1.0 μL of virus was delivered over an additional 10 min. The needle was left in place for 5 additional minutes after the injection of the virus. They were returned to their home cages and used 3 weeks after AAV injection.

2.3. Kainic acid-induced acute seizure model and behavioral tests

The KA-induced acute seizures were produced essentially as previously described [[28], [29], [30]]. KA (Sigma-Aldrich, Cat# K0250) was administered to mice at a dose of 20 mg/kg (diluted in 0.9% NaCl solution) via intraperitoneal injection. To minimize suffering and mortality rates, we intraperitoneally injected diazepam (10 mg/kg body weight) 45 min after KA administration to block seizures and then injected lorazepam (6 mg/kg body weight) 1 h later [31]. The evaluation of seizure severity was performed according to Racine's scale, as reported previously [32]. Seizures were evaluated as follows: stage 0, no seizure; stage I, mouth and facial twitching; stage II, head nodding; stage III, monoliteral forelimb clonus; stage IV, rearing and bilateral forelimb clonus and/or Straub tail; stage V, bilateral limb clonus and falling or turning over onto one side; and stage VI, generalized tonic-clonic seizures. To standardize the measurement of status epilepticus (SE), the behavioral onset of SE was defined as the first time a mouse exhibited a stage ≥ IV seizure. Moreover, when a mouse experienced a minimum of three stage III–VI seizure events within 45 min following KA injection, it was considered to have experienced SE. The seizures were scored by an observer who was blinded to the treatment and who only scored behavioral seizures with a Racine score of III–VI. The mice were scored every 5 min for 45 min after KA injection.

3. Human tissue samples

All human brain tissue specimens were obtained as described in our previous study [28,33,34]. Samples from eight adult patients with drug-resistant temporal lobe epilepsy with hippocampal sclerosis taken during routine surgical procedures were randomly chosen from our brain tissue bank. Samples from these patients were obtained only for treatment purposes. The details were provided in the Supplementary materials and supplementary Table S1 and Table S2. The informed consent form was signed by the patients or their close relatives before surgery. The study was approved by the National Institutes of Health and Human Research Committee of Chongqing Medical University. The human study was carried out in accordance with the National Institute of Health Human Subjects Policies and Guidance released in Jan 26 and Dec 23, 1999. The formal approval to conduct the study described has been obtained from the human being review board of the appropriate ethics committee as stated in the manuscript.

3.1. Primary hippocampal cell culture and spine density analysis

Primary cultured neurons were cultured as described from E18 C57BL/6 mice [35]. Hippocampal explants were digested with 0.25% trypsin (Invitrogen, Cat# 25200072) for 30 min at 37 °C and then triturated with a pipette in Dulbecco's modified Eagle's medium with 10% fetal bovine serum. The dissociated neurons were plated at a density of 65 cells/mm2 in a six-well dish. The cultures were maintained at 37 °C and physiological pH with 5% CO2. After 4 h, the medium was replaced with neurobasal medium supplemented with 2% B27, 1% antibiotic and 0.5 mM GlutaMAX™-I (Invitrogen, Cat# 10565018). The hippocampal neurons were cultured for 5–7 days and then treated with AAV-Nwd1-shRNA, AAV-Scr-shRNA, AAV-GFP, GluN2B-Tyr1472, or GluN2B-Ser1480 before western blotting or immunofluorescence according, to the experimental requirements. To construct a Mg2+-free model, hippocampal neurons were exposed to Mg2+-free artificial cerebrospinal fluid (ACSF) for 3 h at 37 °C.

For spine density analysis, neurons were transfected at DIV5 with 2 μL AAV-Nwd1-shRNA, AAV-Scr-shRNA, or AAV-GFP for two weeks. The neurons were fixed with 4% paraformaldehyde, washed with phosphate-buffered saline (PBS) and incubated with rabbit anti-GFP antibody (1:500, Abcam, Cat# ab6556) overnight at 4 °C. After being washed, the neurons were incubated with a goat anti-rabbit Alexa Fluor 488 (1:200, Beyotime, Cat# A0423) secondary antibody for 1 h at 37 °C. Images were captured with a confocal laser-scanning microscope (LSM700, Zeiss). The number of spines was determined with Image-Pro Plus 6.0 software.

3.2. Biochemical measurement of cell surface protein levels

Biochemical measurements of cell surface protein levels were performed as previously described [36]. Briefly, cell-surface receptor proteins on DIV14–18 neurons cultured in 60-mm diameter dishes were extracted with a Mem-PER™ Plus Membrane Protein Extraction Kit (Thermo Fisher Scientific, Cat# 89842), as per the manufacturer's protocol. The cell precipitate was washed with 3 mL of cell cleaning solution and centrifuged at 300 xg for 5 min, and the supernatant was discarded twice. Permeation buffer (0.75 mL) was added to the cell precipitate. The homogeneous cell suspensions were incubated at 4 °C for 10 min under continuous mixing conditions and centrifuged at 16,000 xg at 4 °C for 15 min, and the supernatant fractions were collected. Solubilizing buffer was added to the precipitate for resuspension and incubated at 4 °C for 30 min. The tube was centrifuged at 16,000 ×g for 15 min at 4 °C. The extracted proteins were then analyzed by immunoblotting.

3.3. Western blot, immunohistochemical staining and immunofluorescence analysis

Western blot, immunohistochemical staining and immunofluorescence analysis of cultured hippocampal neurons and tissues from the animals were performed as described in our previous studies [28,34,37]. The following primary antibodies were used in this study: a rabbit anti-NWD1 pAb (1:500, Proteintech Group, Inc., Cat# 25025–1-AP); a rabbit anti-GAPDH mAb (1:1000, Proteintech Group, Inc., Cat# 10494–1-AP); a guinea pig anti-MAP2 mAb (1:300, Synaptic Systems, Cat# 188004); a mouse anti-GFAP mAb (1:200, Proteintech Group, Inc., Cat# 60190–1-Ig); a chicken anti-GAD67 mAb (1:300; Synaptic Systems, Cat# 198006); a goat anti-PSD95 mAb (1:300, Abcam, Cat# ab12093); a mouse anti-PSD95 mAb (1:300, Abcam, Cat# ab13552); a guinea pig anti-Vglut1 mAb (1:300; Synaptic Systems, Cat# 135304); DAPI (1:50, Sigma-Aldrich, Cat# D9542); a rabbit anti-GluN2A pAb (1:500, Proteintech Group, Inc., Cat# 19953-1-AP); a mouse anti-GluN2B mAb (1:500, Abcam, Cat# ab28373); a rabbit anti-GluN2B pAb (1:500, Abcam, Cat# ab65783); a rabbit anti-GluN2B-Tyr1472 pAb (1:500, Abcam, Cat# ab3856,); and a rabbit anti-GluN2B-Ser1480 pAb (1:200, Bioss, Cat# bs-5382R); a mouse anti-Beta Actin Antibody mAb (1:1000, Proteintech Group, Inc., Cat# 60008-1-Ig).

3.4. Electrophysiological recordings

Hippocampal slices were prepared as described previously [28]. Briefly, AAV-treated mice were anesthetized. Coronal hippocampal slices (400 μm thick) were cut using a vibrating blade microtome (VT1200S, Leica, Germany) in an ice-cold artificial cerebrospinal fluid (ACSF) solution. The fresh slices were placed in a continuously oxygenated humidified interface holding a chamber containing oxygenated Mg2+-free ACSF ((in mM) 124 NaCl, 2.5 KCl, 1.25 NaH2PO4·2H2O, 26 NaHCO3, 0 MgCl2·6H2O, 2 CaCl2, and 10 glucose (pH 7.4, 315–330 mOsm)), in which they recovered for at least 1 h before subsequent studies. After recovery, whole-cell patch-clamp recordings were made from CA1 pyramidal neurons visualized with infrared optics using an upright microscope equipped with a 40× water-immersion lens (BX51WI, Olympus, Tokyo, Japan) and an infrared-sensitive CCD camera (Dage-MTI, Michigan City, IN, USA). The slices were placed in the recording chamber, which was superfused (2 mL/min) with Mg2+-free ACSF at 22–24 °C with a 1440A digitizer and a MultiClamp 700B amplifier (Molecular Devices, Palo Alto, CA). Pipettes were pulled by a micropipette puller (P-97, Sutter Instruments) with a resistance of 3–5 MΩ. All solutions were saturated with 95% O2 and 5% CO2.

For miniature excitatory postsynaptic current (mEPSC) recordings, the pyramidal neurons were held at −70 mV in the presence of 1 μM TTX (Aladdin Bio-Chem Technology Co., Cat# 4368-28-9) and 100 μM picrotoxin (PTX) (Sigma-Aldrich, Cat# R284556), with the pipette solution containing (in mM) 130 CsMeSO4, 10 HEPES, 10 CsCl, 4 NaCl, 1 MgCl2·6H2O, 1 EGTA, 12 Na-phosphocreatine, 0.5 Na3-GTP, 5 Mg-ATP, and 5 NMG (pH 7.3, 285 mOsm). For miniature inhibitory postsynaptic current (mIPSC) recordings, the pyramidal neurons were bathed with 1 μM TTX, 20 μM DNQX (Sigma-Aldrich, Cat# D0540), and 50 μM DL-AP5 (Sigma-Aldrich, Cat# A8054), with the pipette solution containing (in mM) 100 CsCl, 10 HEPES, 1 MgCl2·6H2O, 1 EGTA, 30 NMG, 0.5 Na3-GTP, 5 Mg-ATP, 1 EGTA, and 12 Na-phosphocreatine (pH 7.3, 290 mOsm).

To investigate the properties of evoked excitatory postsynaptic current (EPSC) recordings, 100 μM PTX was added to the ACSF to block GABAA receptor currents. EPSCs were evoked by stimulating the Schaffer collateral (SC)-CA1 pathway with a bipolar tungsten stimulating electrode (0.05 Hz, 0.1 ms duration). The neurons were held at −70 mV to record α-amino-3-hydroxy-5-methyl-4-isoxazolepropionic acid receptor-dependent EPSCs (AMPA-EPSCs) and at +40 mV to record NMDAR-mediated EPSCs (NMDA-EPSCs). AMPAR and NMDAR current amplitudes were evaluated by averaging 10 traces measured at the point of the peak amplitude and 50 ms after the peak amplitude, respectively. After EPSC baseline recordings, the GluN2B subunit antagonist ifenprodil (Sigma-Aldrich, Cat# I2892) was added to the ACSF for additional EPSC recordings.

For paired-pulse ratio (PPR) recordings, EPSCs were evoked by stimulating the SC-CA1 pathway (50 ms stimulation interval) at a holding potential of +40 mV in the presence of 100 μM PTX and 20 μM DNQX. The value of the ratios was defined as the amplitude of the EPSCs evoked between the first and second pulse. For spontaneous firing recordings of hippocampal pyramidal neurons, the slices were perfused in Mg2+-free ACSF and held at resting membrane potential. Microelectrodes were filled with the following solution (in mM): 60 K2SO4, 60 NMG, 40 HEPES, 4 MgCl2·6H2O, 0.5 BAPTA, 12 Na-phosphocreatine, 2 Na-ATP, and 0.2 Na3-GTP (pH 7.3, 290 mOsm). Four or more action potentials were defined as epileptiform activity of the pyramidal neurons and were quantified as a depolarization drift (PDS). After 10 min of baseline recordings, the NMDA receptor antagonist DL-AP5 was bath-applied for 20 min.

Extracellular field potential recordings were performed as described previously [28,38]. Electrodes were positioned in the CA1 stratum radiatum in current-clamp mode with 1 M NaCl-filled glass pipettes (1–2 MΩ). Electrophysiological signals were amplified and filtered at 0.1 Hz and 1 kHz by a MultiClamp 700 B amplifier digitized at 5 kHz with a 1440A digitizer. Epileptiform activity was induced by perfusing Mg2+-free/4-AP ACSF containing the following (in mM): 124 NaCl, 1.25 NaH2PO4·2H2O, 26 NaHCO3, 0 MgCl2·6H2O, 2 CaCl2, 10 glucose and 0.1 4-AP. The onset of synchronous population activity was timed from the negative peak of the initial population spike to the last spike present in each epileptiform event. After 30 min of baseline recordings, DL-AP5 was bath-applied for 40 min.

In all experiments, series and input resistances were continually controlled below 20 MΩ and were not compensated. The data were not included if the series resistance fluctuated >25% of the initial value. The data were analyzed using pClamp 10.0.3 and MiniAnalysis 6.0.3 (Synaptosoft, USA), and at least 50% of the data were analyzed in a blinded fashion. All reagents for ACSF preparation were obtained from Sigma-Aldrich or Tocris Bioscience.

3.5. Statistical analysis

The statistical analyses were performed using Prism 6.0 software (GraphPad, San Diego, CA, USA). For all electrophysiological, biochemistry and immunohistochemistry experiments, an unpaired two-tailed Student's t-test (for two sample) or one-way ANOVA followed by Tukey's multiple comparisons test (for three or more samples) were used. The differences between the mean values were evaluated using one-way ANOVA followed by the least significant difference (LSD) test for post hoc comparisons when equal variances were assumed. For the electrophysiological tests, the n values represent the number of neurons and slices. For all other experiments, the n values represent the number of tissues from mice or patients. All of the results are shown as the means ± S.E.M., and statistical significance was set at *P < .05, **P < .01, ***P < .001.

4. Results

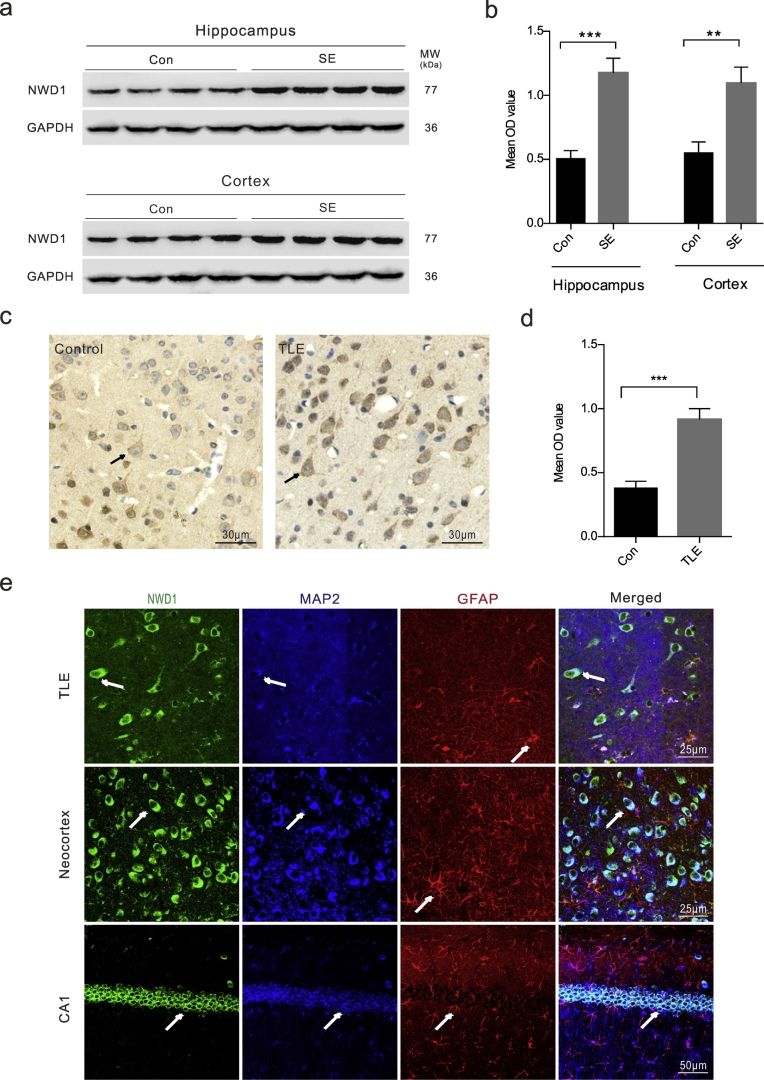

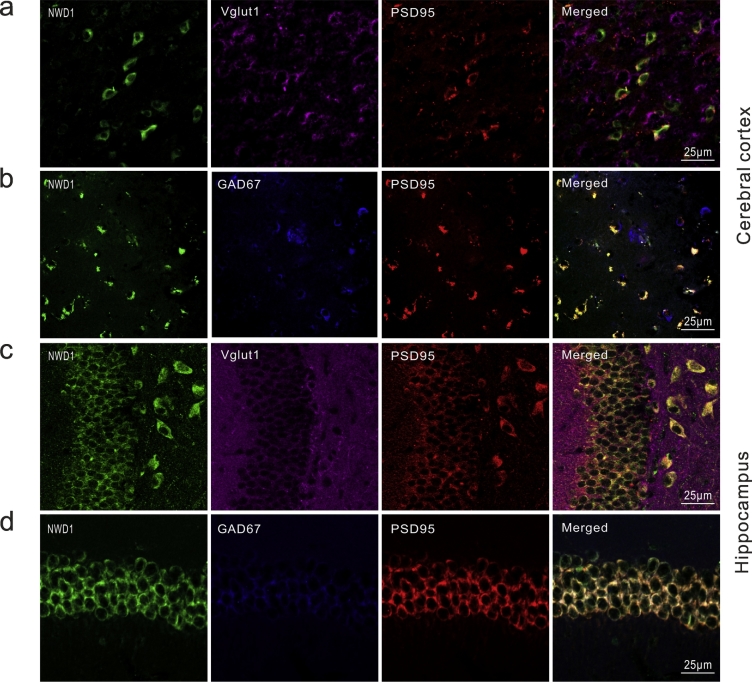

4.1. Nwd1 is expressed in the excitatory synapses of seizure-induced mice and in human epileptogenic tissues

To demonstrate the correlation between Nwd1 and seizure, we first assessed whether pathologic seizure activity in vivo affects Nwd1 expression. The KA-induced model recapitulates the neuropathological, electroencephalographic and behavioral characteristics that are observed in epileptic patients, particularly recurring spontaneous seizures (SRSs) that are resistant to various antiepileptic drugs [39,40]. The results showed that the levels of the Nwd1 protein were increased in the hippocampus and cerebral cortex of KA-induced acute seizure mice compared with those in the control (Fig. 1a–b). To further characterize this effect, we used immunohistochemistry, and we found similar expression patterns in cortical tissue obtained from drug-resistant TLE patients. Nwd1 immunoreactivity was stronger in cerebral cortex tissues from TLE patients than in those from controls (Fig. 1c–d). The imbalance between inhibitory and excitatory components result in neuronal networks hyperexcitability through neurotransmission synaptic function, which eventually leads to seizures [2]. We then examined the distribution of Nwd1 in functional synapses to further explore the function of Nwd1 in seizure. Triple immunofluorescence staining of TLE and acute seizure mouse specimens revealed that Nwd1 was located in MAP2-positive neurons but not in GFAP-positive astrocytes in the hippocampus and cerebral cortex, demonstrating that hippocampal neurons express Nwd1 (Fig. 1e; Fig. S1c). Moreover, Nwd1 was coexpressed with the excitatory synapse postsynaptic density marker PSD95, whereas cells labeled with the presynaptic vesicular marker VGLUT1 were not positive for Nwd1 (Fig. 2a, c). In a further analysis, Nwd1 was weakly expressed in inhibitory synapses labeled with the glutamate decarboxylase isoform GAD67 (Fig. 2b, d) These results show that Nwd1 may play a role in seizure by being mainly expressed in functional excitatory synapses.

Fig. 1.

Nwd1 expression is upregulated in the brain tissues of a mouse model of acute seizures and TLE patients.

(a–b) Western blot analysis shows that Nwd1 protein levels are increased in the hippocampus and cerebral cortex of mice with KA-induced status epilepticus compared with those in the control (***P = .0002, **P = .0034, n = 8 per group, unpaired t-test; SE, status epilepticus). (c–d) Immunohistochemical staining indicates that Nwd1 immunoreactivity in the cerebral cortex tissues is stronger in TLE patients than in controls (***P = .0003 versus control, n = 8 per group, unpaired t-test). (e) Nwd1 is expressed in pyramidal neurons and colocalizes with microtubule-associated protein 2 (MAP2)-positive neurons but not with an astrocyte marker (glial fibrillary acidic protein (GFAP)) in cortical and hippocampal samples from TLE patients and acute seizures mice. The arrows indicate the positive cells. The error bars indicate the SEM. *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01, ***P < 0.001.

Fig. 2.

Nwd1 location in excitatory synapses acute seizures brain tissues.

(a–b) Immunofluorescence staining for Nwd1 in the cerebral cortex of individuals with TLE patients. Nwd1 co-localizes with excitatory synapses marker postsynaptic density protein PSD95 but presynaptic vesicular marker Vglut1 (a) and less in inhibitory synapses marker GAD67 (b). (c–d) Immunofluorescence of Nwd1 in the hippocampi from KA-induced acute seizures mice show that Nwd1 colocalizes with PSD95 and lacks of colocalization of Nwd1with Vglut1 (c) and less in GAD67 (d) in the neuronal cells.

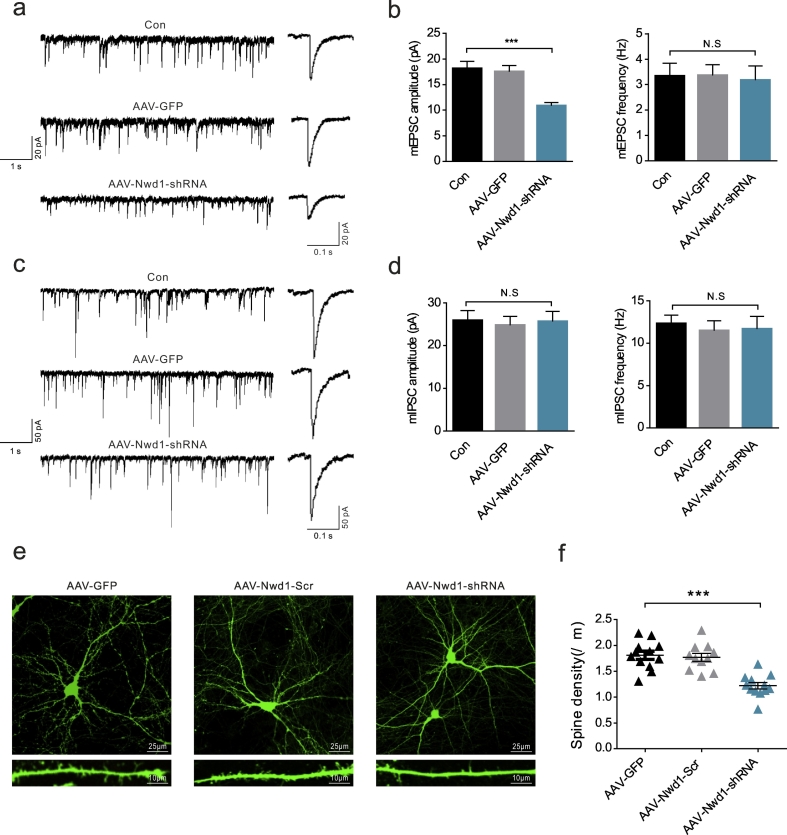

4.2. Downregulation of Nwd1 weakens glutamatergic synaptic transmission

We next explored the molecular mechanism underlying the effect of Nwd1 deletion on seizures and asked whether Nwd1 is necessary and sufficient for regulating excitatory synaptic transmission. To further test this possibility, we measured mEPSCs and mIPSCs in hippocampal pyramidal neurons [41,42] prepared from acute brain slices taken from mice injected with AAV-Nwd1-shRNA or AAV-GFP. The slices were subjected to voltage-clamp recordings in a Mg2+-free model in vitro. Compared to the recordings from AAV-GFP-treated and untreated control littermates, the whole-cell recordings from the CA1 pyramidal neurons of the AAV-Nwd1-shRNA-treated mice showed significantly lower mEPSC amplitudes without a change in frequency (Fig. 3a–b). However, inhibitory synaptic transmission, as measured by the frequencies and amplitudes of the mIPSCs, was not significantly affected (Fig. 3c–d). These results suggest that the major alteration that occurs after the knockdown of Nwd1 is a decrease in glutamatergic synaptic transmission manifested as a reduction in postsynaptic receptor number/function.

Fig. 3.

Downregulation of Nwd1 weakens glutamatergic synaptic transmission in hippocampal pyramidal neurons.

(a) Representative mEPSC recordings (left) and average waveforms (right) for the control (Con), AAV-GFP-injected and AAV-Nwd1-shRNA-injected mice. (b) The quantitative analysis of mEPSC frequency and amplitude (n = 14 neurons for Con, n = 13 neurons for AAV-GFP; n = 15 neurons for AAV-Nwd1-shRNA). (c) Representative mIPSC recordings (left) and average waveforms (right) for the mice in all groups. (d) The quantitative analysis of mIPSC frequency and amplitude (n = 12 neurons for Con, n = 13 neurons for AAV-GFP; n = 11 neurons for AAV-Nwd1-shRNA). (e) Representative images of the dendrites of primary hippocampal neurons treated with either AAV-GFP, AAV-Nwd1-Scr or AAV-Nwd1-shRNA. (f) The summary of spine density (n = 12 neurons for AAV-GFP, n = 11 neurons for AAV-Nwd1-Scr; n = 12 neurons for AAV-Nwd1-shRNA). Scale bars: upper panels, 25 μm; lower panels, 10 μm. The error bars indicate the SEM. ***P < 0.001, P ≥ .05 was considered not significant (N.S.). One-way analysis of variance (ANOVA), followed by Tukey's test.

Because some evidence supports that a loss in dendritic spine density leads to reduced excitatory synapses [[43], [44], [45]], we examined whether AAV-Nwd1-shRNA causes changes to dendritic spines in primary hippocampal cells. Consistent with a reduction in excitatory synaptic transmission, we observed a significantly lower dendritic spine density in Nwd1-knockdown neurons compared with control neurons (Fig. 3e–f). Thus, injecting AAV-Nwd1-shRNA in vitro resulted in a significant reduction in spine density.

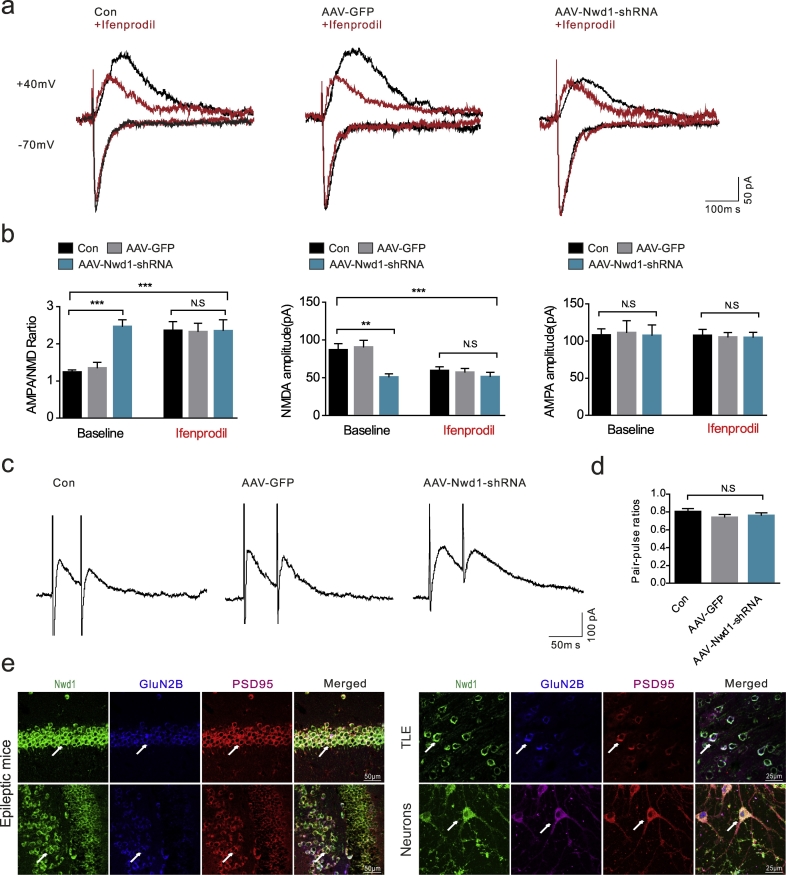

4.3. Nwd1 inhibition decreases GluN2B-dependent EPSCs in the hippocampus

To test whether the decreased mEPSC amplitudes correspond to a decrease in synaptic strength, we recorded evoked EPSPs in pyramidal neurons from the CA1 region of the hippocampus. The ratio between the amplitudes of the AMPA-EPSCs and the amplitudes of the NMDA-EPSCs was defined as the AMPA/NMDA ratio, which is often used to measure glutamatergic synaptic strength [46,47]. The AAV-Nwd1-shRNA-treated mice exhibited a significantly increased AMPA/NMDA ratio relative to that of the AAV-GFP-treated and control mice (Fig. 4a–b). Moreover, NMDA-EPSC amplitudes (50.55 ± 4.83 pA) were significantly decreased compared to those obtained from the AAV-GFP-injected mice (90.13 ± 9.54 pA), whereas there was no effect of AAV-Nwd1-shRNA on the amplitudes of the AMPA-EPSCs (Fig. 4a–b). The results showed that the AAV-Nwd1-shRNA-induced increase in the AMPA/NMDA ratio was due to a reduction in NMDA receptor function. The NMDAR subunit GluN2B forms a glutamate-gated ion channel that is pivotal for the regulation of synaptic function [48]. Compared to the baseline ratio in the Con and AAV-GFP-treated slices, the AMPA/NMDA ratio and the NMDA-EPSC amplitudes were not significantly altered in the AAV-Nwd1-shRNA-treated slices after they were exposed to ifenprodil (a GluN2B subunit antagonist) for 15 min (Fig. 4a–b). The paired-pulse ratio (PPR) was determined in the presence of PTX and DNQX to ensure the elimination of the effects on GABAA and AMPA receptors. The results showed that there was no significant difference between the PPRs of the AAV-Nwd1-shRNA-treated, AAV-GFP-injected and control mice, suggesting that Nwd1 does not alter the probability of presynaptic NMDA release (Fig. 4c–d). Triple labeling of human brain and seizure mice tissues and primary hippocampal neurons with antibodies against the GluN2B subunit, Nwd1 and PSD95 showed that these neurons express three receptors with a similar distribution pattern, further supporting the possibility that the effect of Nwd1 on NMDA occurs through the GluN2B subunit (Fig. 4e). Therefore, these results indicate that Nwd1 knockdown decreases GluN2B-dependent EPSCs in hippocampal pyramidal neurons.

Fig. 4.

Nwd1 inhibition decreases the GluN2B-dependent EPSCs in the hippocampus. (a) Representative recordings of NMDAR- and AMPAR-mediated responses a single neuron during application of regular free magnesium ACSF (baseline), followed by solution containing Ifenprodil in all groups. (b) Down-regulation Nwd1 decreased AMPAR/NMDAR ratio and NMDA-EPSCs amplitudes, but had no such effect after application of GluN2B inhibitor Ifenprodil to the same cells (n = 12 neurons for Con, n = 11 neurons for AAV-GFP; n = 11 neurons for AAV-Nwd1-shRNA). (c) Representative traces are shown for paired-pulse stimulation recording from hippocampal pyramidal neurons. (d) Summary of results demonstrates that the paired-pulse ratio (P2/P1; ordinate) is not significantly changed in Con, AAV-GFP and AAV-Nwd1-shRNA treated mice (P ˃ 0.05). (e) Immunostaining analysis of Nwd1, GluN2B, and PSD95 expression in the hippocampi from acute seizures mice, cerebral cortex of TLE patients and cultured hippocampal neurons. Error bars, s.e.m.; ANOVA followed by Tukey's test. **P ˂ 0.01, ***P < 0.001, N.S., not significant.

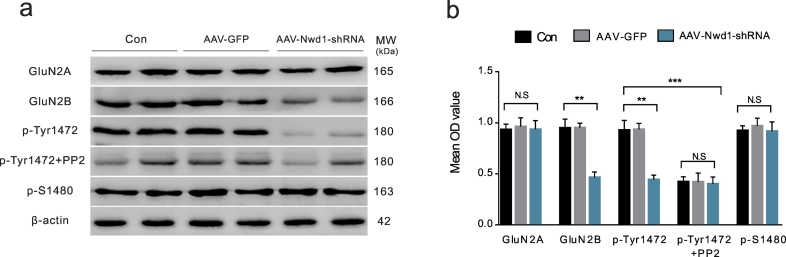

4.4. Decreased neuronal Nwd1 activity alters the phosphorylation of GluN2B at Tyr 1472

The tyrosine phosphorylation of the GluN2B subunit regulates the trafficking and synaptic localization of NMDARs [10,17]. To determine whether decreased synaptic activity is due to the lower number of NMDARs on the cell surface induced by GluN2B phosphorylation, we isolated surface receptors and analyzed them by western blotting. The phosphorylation levels of GluN2B at Tyrosine1472 (Tyr1472) and Serine 1480 (S1480) were assessed using phospho-site-specific antibodies. We found that the pretreatment of hippocampal neurons with AAV-Nwd1-shRNA in magnesium-free conditions decreased the surface expression of GluN2B and the phosphorylation of the GluN2B subunit at Tyr1472 without affecting the phosphorylation of GluN2B at S1480 or the surface expression of GluN2A compared with those in the control groups (Fig. 5a–b). When the hippocampal neurons were exposed to the Src family tyrosine kinase inhibitor PP2 (1 μM) after pretreatment with AAV, the results showed that the phosphorylation of GluN2B at Tyr1472 did not change in the AAV-Nwd1-shRNA-treated neurons (Fig. 5a–b). Our experiments suggest that the phosphorylation of GluN2B at Tyr1472 may play an important role in the synaptic localization of NMDARs.

Fig. 5.

Phosphorylation of Tyr1472 in GluN2B is suppressed in the hippocampal neurons after decreasing Nwd1 activity.

(a) Representative western blots for GluN2A, GluN2B, p-Tyr1472 and p-S1480 in the primary hippocampal neuron lysate obtained from AAV-Nwd1-shRNA, AAV-GFP and control neurons. (b) Quantitative analysis of data in (a). The surface protein amount of GluN2B, but not of GluN2A, is decreased after AAV-Nwd1-shRNA treated, and p-Tyr1472 intensity is decreased. However, p-Tyr1472 intensity did not change after application of inhibitor PP2 to the AAV-Nwd1-shRNA treated groups. Phosphorylation of GluN2B at S1480 showed no change in the neurons treated with AAV-Nwd1-shRNA compared to control and AAV-GFP group (n = 6 mice for each group). Error bars indicate SEM. ANOVA followed by Tukey's test. **P < 0.01, ***P < 0.001. N.S., not significant.

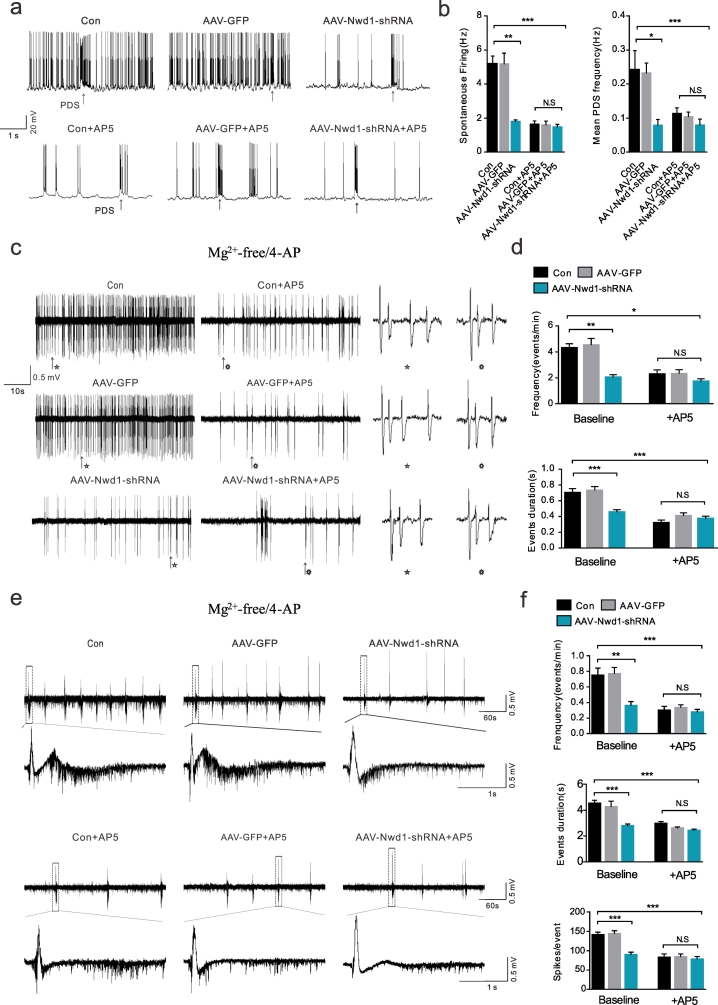

4.5. Inhibition of Nwd1 activity alleviates neuronal hyperexcitability

A logical hypothesis based on the data presented above is that Nwd1 downregulation produces a long-lasting decrease in the spontaneous firing of hippocampal pyramidal neurons due to the weakness of postsynaptic NMDA receptor function. To test this hypothesis, we performed in vitro intracellular and extracellular recordings in slices treated with AAV-Nwd1-shRNA or AAV-GFP in Mg2+-depleted ACSF to measure spontaneous firing. Our results demonstrated that, compared to the pyramidal neurons of the AAV-GFP-treated and controls, the pyramidal neurons of the AAV-Nwd1-shRNA mice exhibited a decreased spontaneous firing frequency (Fig. 6a–b). In agreement with this result, the frequency of PDS (a high-frequency burst of action potentials) was reduced in the AAV-Nwd1-shRNA slices (Fig. 6a–b). In addition, the application of the NMDA agonist DL-AP5 (50 μM) had no significant effect on spontaneous firing or PDS frequency in the AAV-Nwd1-shRNA slices compared to control slices (Fig. 6a–b). We evaluated whether Nwd1 contributes to abnormal network excitability, and we found that epileptiform activity, including ictal-like events and interictal-like events, were less frequently observed in extracellular recordings of the hippocampal CA1 area of the AAV-Nwd1-shRNA slices, indicating decreased excitability in these tissues (Fig. 6c–f). Similar to the above results, there was a significant reduction in the duration of epileptiform events in the AAV-Nwd1-shRNA-treated mice compared to the AAV-GFP-injected and control mice (Fig. 6). Moreover, epileptiform event spikes were reduced in the slices obtained from the AAV-Nwd1-shRNA mice (Fig. 6f). Pretreatment with DL-AP5 produced results similar to spontaneous firing patterns in the AAV-Nwd1-shRNA slices (Fig. 6d, f). These results are consistent with the hypothesis that the lower levels of Nwd1 that induce a reduction in postsynaptic NMDA receptor function produce a decreased neuronal hyperexcitability in hippocampal pyramidal neurons and slices.

Fig. 6.

Inhibition of Nwd1 activity alleviates neuronal hyperexcitability in vitro in a model of magnesium-free induced seizure.

(a) Representative spontaneous firing traces of CA1 pyramidal neurons at baseline (upper traces) and after bath application of AP5 (lower traces) are shown for each experimental group. (b) Graphs showing the spontaneous firing and PDS frequency in the AAV-Nwd1-shRNA-treated, AAV-GFP-treated and control slices, and the effect of the NMDAR antagonist DL-AP5 application on spontaneous firing and PDS frequency (n = 10 neurons for control, n = 10 neurons for AAV-GFP-treated, n = 11 neurons for AAV-Nwd1-shRNA-treated; *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01, ***P < 0.001; ANOVA followed by post hoc test). (c, e) Representative extracellular recordings showing the initiation of interictal-like epileptiform events (c) and ictal-like epileptiform events (e) in proconvulsant ACSF (0 Mg2+, 100 μM 4-AP) in the CA1 region of control, AAV-GFP-treated and AAV-Nwd1-shRNA-treated mice in the absence or presence of DL-AP5. (d) Quantitative analysis of the data in (c). Slices from AAV-Nwd1-shRNA mice showed a reduction interictal-like event frequency and a decreased average event duration. Pretreatment with 20 μM DL-AP5 decreased the average event duration and reduced the interictal-like event frequency in control and AAV-GFP-treated slices but not in AAV-Nwd1-shRNA-treated slices (*P < 0.05, **P < 0.01, ***P < 0.001). (f) Quantitative analysis of the data in (e). The average of ictal-like event frequency, event duration and event spikes were all reduced in slices obtained from AAV-Nwd1-shRNA-treated mice. The application of AP5 decreased the above indicators in Con control and AAV-GFP-treated slices but not in AAV-Nwd1-shRNA-treated slices (n = 11 slices for control, n = 10 slices for AAV-GFP-treated; n = 11 slices for AAV-Nwd1-shRNA-treated; The error bars indicate the SEM. ANOVA followed by post hoc test (*P < 0.05, **P < 0.01, ***P < 0.001; N.S., not significant).

4.6. The effect of Nwd1 on acute seizures in a KA-induced mouse model

In general, seizures can be produced by an imbalance between neuronal excitation and inhibition, in which glutamate and GABA, respectively, play important roles [2,49]. Consistent with this, our above results found that downregulation of Nwd1 reduced excitability. Meanwhile, having characterized a pattern of Nwd1 upregulation in the excitatory synapses of acute seizures mouse and TLE patient specimens, we next investigated whether Nwd1 activity contributes to seizures. To address this issue, we compared the seizures in acute SE evoked by intraperitoneal injections KA every 5 min for 45 min (Fig. 7a). First, we reduced Nwd1 levels in C57BL/6 mice by an intrahippocampal injection of AAV-Nwd1-shRNA 3 weeks before KA application [28,50]. The time to the onset of the first seizure (the latency of SE onset) was markedly delayed by AAV-Nwd1-shRNA treatment (Fig. 7b). Compared with the control mice, the AAV-Nwd1-shRNA injected mice also exhibited a significantly reduced average duration of behavioral seizure events (Fig. 7c). In addition, there was no difference in the average behavior seizure score among all groups, which indicated that Nwd1 had no effect on seizure score (Fig. 7d). Furthermore, we measured the relationship between seizure degree and the levels of the Nwd1 protein, and we found that Nwd1 expression was reduced in the AAV-Nwd1-shRNA-treated mice after KA-induced SE (Fig. S2a–b). Consistent with the above results, Nissl staining indicated the protective effects of AAV-Nwd1-shRNA against the hippocampal tissue damaged by KA exposure. The loss of Nissl substance was attenuated by AAV-Nwd1-shRNA injection (Fig. S2c). Furthermore, immunofluorescence staining showed a loss of NeuN positive cells in the hippocampal CA1 region of vehicle- and AAV-Nwd1-GFP-treated mice after KA-SE treatment. This hippocampal damage was attenuated by AAV-Nwd1-shRNA (Fig. S2d–e). Collectively, these results imply that the low expression of Nwd1 mitigates KA-induced seizures.

5. Discussion

To our knowledge, these are the first in vivo and in vitro studies showing that the inhibition of Nwd1 can alter pathologic electrical activity in the brain, and our results offer a novel therapeutic target for the treatment of seizures. In the present study, we identified a novel role for Nwd1 in controlling synaptic NMDAR composition. Specifically, we obtained four principal findings from this study: 1) there are high protein levels of Nwd1 in brain tissues obtained from TLE patients and mice with KA-induced acute seizures; 2) in vitro, inhibition of Nwd1 by AAV reduces excitatory synaptic transmission by suppressing GluN2B-containing NMDAR-mediated excitatory postsynaptic currents in acute hippocampal slices; 3) the downregulation of Nwd1 reduces GluN2B surface protein levels by decreasing the phosphorylation of the GluN2B subunit at Tyr1472 in primary hippocampal neurons; and 4) silencing Nwd1 profoundly suppresses neuronal hyperexcitability and reduces the occurrence of acute seizures during KA-induced SE. Our findings highlight the important role of Nwd1 in regulating neuronal excitability, and the inhibition of Nwd1 may lead to a therapeutic strategy for treating acute seizures or other hyperexcitability-related neurological disorders.

Nwd1 is a newly identified NLR-related protein that contains a central NACHT domain akin to that of classical NLR family members [25,51]. There has been no evidence produced by recent profiling work to suggest that there is an association between seizures and changes in Nwd1 expression. Our experiments are the first to show the upregulation of Nwd1 in the hippocampus and cortex of TLE patients and acute seizure mice specimens and to link this upregulation to harmful seizures. This suggests that the regulation of Nwd1 may be coupled to epileptic or pathogenic brain activity.

Synapse dysfunction has been implicated in epilepsy [4]. As shown by immunofluorescence staining, Nwd1 was localized to MAP2-positive cells and cells positive for the excitatory synapse marker PSD95- in hippocampal and cortical epileptic tissues but was not localized to cells positive for an inhibitory synapse marker. These results suggest that Nwd1 may be associated with seizures through its expression in functional excitatory synapses. In addition, our electrophysiological studies revealed that Nwd1 was suppressed in hippocampal CA1 pyramidal neurons in Mg2+-depleted ACSF [28,52], and the AAV-Nwd1-shRNA-treated slices displayed a reduction in mEPSC amplitude. However, AAV-Nwd1-shRNA had no effect on mEPSC frequency, mIPSC frequency or amplitude. These observations imply that silencing Nwd1 may alter glutamatergic receptor function. Dendritic spine structure and density are positively related to synaptic strength and the expression of synaptic proteins. Dendritic spines are targets of excitatory axons, and spine loss accounts for reduced excitatory responses in the brain [43,53]. Here, we found that the knockdown of Nwd1 in mice decreased excitatory synaptic transmission, likely by decreasing the basal number of dendritic spines in the hippocampus. Moreover, NMDAR subunits are crucial for neuronal synaptic transmission and synaptic plasticity [54]; consistent with this, whole-cell recording studies revealed decreased NMDAR currents in the AAV-Nwd1-shRNA-injected mice that were not changed in the presence of ifenprodil, suggesting an effect of GluN2B-mediated EPSCs. Together, our findings highlight that glutamatergic synaptic transmission is downregulated by Nwd1 silencing via postsynaptic GluN2B-containing-NMDAR-mediated mechanisms.

NMDAR surface proteins, especially the GluN2B subunit, are dynamic, and their trafficking, insertion, and internalization are tightly regulated [[54], [55], [56]]. The tyrosine phosphorylation of NMDAR subunits is an important regulatory mechanism for plastic changes in NMDARs [57]. Previous research has found that the phosphorylation of Tyr1472 positively correlates with the surface expression of NMDARs by Cdk5 in an activity-dependent manner [19]. In our study, we found that the phosphorylation of Tyr1472 and the surface expression of GluN2B were decreased in primary hippocampal neuron lysates after incubation with Mg2+-free ACSF when Nwd1 activity was inhibited by AAV-Nwd1-shRNA. Nevertheless, the downregulation of Nwd1 affected neither Ser1480 phosphorylation nor the surface expression of GluN2A. Therefore, our data indicate a novel mechanism by which Nwd1 impacts the level of surface GluN2B protein in an activity-dependent manner by regulating the level of Tyr1472 phosphorylation. Existing research suggests that the phosphorylation of Tyr1472-GluN2B lowers the binding of NMDARs to the clathrin adaptor protein complex AP-2 and therefore may be related to the endocytosis machinery [18]. However, our experiment did not confirm whether Nwd1 is involved in NMDAR trafficking and thus whether it affects the surface expression of GluN2B; this notion needs to be explored in further experiments. Based on our study, we speculate that suppressed levels of the Nwd1 protein result in a loss of phosphorylated Tyr1472 and, consequently, in the decreased surface expression of GluN2B, which in turn results in impaired GluN2B-mediated synaptic transmission.

Given that postsynaptic Nwd1 is a key mediator of NMDAR activity, a critical question is whether postsynaptic Nwd1 is linked to neuronal hyperexcitability and behavioral phenotypes. Circuit hyperexcitability is accompanied by increased spontaneous excitatory synaptic input or reduced inhibitory synaptic input, which leads to a shift in the balance between excitation and inhibition and generates neuronal hyperexcitability [2,58,59]. In the in vitro Mg2+-free model used in this study, our findings suggest that there was a significant reduction in spontaneous firing and the PDS of single hippocampal pyramidal neurons from the AAV-Nwd1-shRNA-injected mice, which was in agreement with the application of the NMDA agonist DL-AP5. Moreover, the observed decrease in NMDAR-dependent excitatory synaptic transmission was not accompanied by a significant change in inhibitory transmission, which eventually led to less spontaneous firing. Interictal-like epileptiform discharge activity was secondary to after discharges, as has been described previously. Ictal-like epileptiform discharge activity was composed of an initial sustained phase and a subsequent phase of involving an intermittent pattern of population discharges [38,60]. This is similar to tonic-clonic seizures in patients with epilepsy. In our experiment, extracellular recordings from the CA1 region of the AAV-Nwd1-shRNA-treated slices indicated that the frequencies and durations of the interictal-like and ictal-like epileptiform discharges, as well as ictal-like epileptiform discharge event spikes, were lower than those of the control groups. This finding suggests that the neuronal hyperexcitability and hypersynchrony inhibited by the downregulation of Nwd1 may inhibit seizures and after discharges. To further verify these results, we measured animal behavior. The KA-induced model exhibited typical histopathological changes analogous to those of temporal lobe epilepsy patients [39]. Our in vivo experiment suggested lower Nwd1 expression lengthened the seizure onset and reduced the seizure duration of status epilepticus induced by KA. These data show that the knockdown of Nwd1 generates a prolonged anticonvulsant effect in a manner similar to that produced by anti-epileptic drugs.

In conclusion, we report a previously unrecognized but important role of Nwd1 in acute seizure models in vitro and in vivo. Our results for the first time reveal an increase in Nwd1 expression in brain tissues from TLE patients, suggesting that this molecule may be associated with human epilepsy. This study indicates that the knockdown of Nwd1 profoundly suppresses neuronal hyperexcitability and acute seizures, and suggests that Nwd1 downregulation controls GluN2B-containing-NMDAR-mediated glutamatergic transmission by decreasing the Tyr1472 phosphorylation of GluN2B. Given the effects of Nwd1, our study contributes to the understanding of the biological role of Nwd1 at the synapse and the characterization of the beneficial effects of Nwd1 in the treatment of seizures. Moreover, this study provides a clue for the development of an alternative approach to the treatment of epilepsy through offers a novel therapeutic target on Nwd1.

The following are the supplementary data related to this article.

Analysis of the differential expression of Nwd1 after AAV injection. (a) A representative western blot for Nwd1 after AAV injection is shown. Compared with AAV-Nwd1-shRNA2 and AAV-Nwd1-shRNA3, AAV-Nwd1-shRNA1 effectively decreased Nwd1 expression in the hippocampus 3 weeks after AAV injection (n=4; **P˂ 0.01; N.S. represents no significance; ANOVA followed by Tukey’s test). (b) Representative fluorescence images of AAV-Nwd1-shRNA expression in the hippocampus in AAV-Nwd1-shRNA-infected mice. Scale bar, 400 μm. (c) Immunofluorescence analysis showing the expression of Nwd1 in hippocampal coronal sections from normal mice and mice with KA-induced SE. Note that Nwd1 is expressed in neurons from normal mice and mice with seizures. Scale bar, 50 μm.

Expression and morphological changes in the hippocampus after KA-induced SE. (a) Representative western blots for Nwd1 in hippocampal lysates from control mice and AAV-GFP- and AAV-Nwd1-shRNA injected mice immediately following 1 hr after SE. (b) Quantitative analysis of the data in (a). The level of Nwd1 protein decreased in AAV-Nwd1-shRNA-treated mice compared with control and AAV-GFP-treated mice (n=4; **P˂ 0.01; N.S. represents no significance; ANOVA followed by Tukey’s test). (c) Nissl staining showing Nissl substance loss and pyramidal neuron loss in the CA1, CA3 and dentate gyrus (DG) areas after KA-SE in vehicle- and AAV-GFP-treated mice. Note that this hippocampal damage was attenuated by AAV-Nwd1-shRNA. The red rectangles represent high magnification images. Scale bar: Hippocampus, 400 μm; CA1, DG, 50 μm; CA3, 100 μm. (d) Immunofluorescence analysis showing the expression of NeuN (green) and GFAP (red) in hippocampal coronal sections after AAV injection in KA-SE mice. Scale bar, 50 μm. (e) Quantitative analysis of the number of NeuN-positive cells in the CA1 region of the hippocampus in each group. Note the reduced number of neurons in vehicle- and AAV-GFP-treated mice. However, the number of neurons was attenuated in AAV-Nwd1-shRNA-treated mice. The error bars indicate the SEM (n = 3 per group; neurons from 10 brain slices were counted for each animal; * P˂ 0.05, *** P˂ 0.001).

Supplemental Information for Inhibition of Nwd1 activity attenuates neuronal hyperexcitability and GluN2B phosphorylation in the hippocampus.

Author contribution

QY, ZFH, YFL, FSZ, YDH, XFW and QW designed the experiments. QY, FSZ, YDH, HL, SZZ, MQH, DMX, YL, MY, YY, XBW, WW, JHM and YLM performed the experiments and analyzed the data. QY, XFW and QW wrote the manuscript. XFW and QW supervised the all work.

Declaration of Competing Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Acknowledgements

This work was supported by the Science and Technology Program of Guangdong of China (Grant No: 2016A050502019), Natural Science Foundations of Guangdong of China (Grant NO: 2017A030311010), Leading Talent in Talents Project Guangdong High-level Personnel of Special Support Program, and Scientific Research Foundation of Guangzhou (Grant NO: 201704030080), National Natural Science Foundation of China (Grant NOs: 81873777, 81901310, 81671301, 81471319, 81301109).

Contributor Information

Xuefeng Wang, Email: WXF201346@163.com.

Qing Wang, Email: denniswq@yahoo.com.

References

- 1.Pitkanen A., Lukasiuk K. Mechanisms of epileptogenesis and potential treatment targets. Lancet Neurol. 2011 Feb;10(2):173–186. doi: 10.1016/S1474-4422(10)70310-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Wu Y., Liu D., Song Z. Neuronal networks and energy bursts in epilepsy. Neuroscience. 2015 Feb 26;287:175–186. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroscience.2014.06.046. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Punnakkal P., Dominic D. NMDA receptor GluN2 subtypes control epileptiform events in the Hippocampus. Neuromolecular Med. 2018 Mar;20(1):90–96. doi: 10.1007/s12017-018-8477-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Casillas-Espinosa P.M., Powell K.L., O'Brien T.J. Regulators of synaptic transmission: roles in the pathogenesis and treatment of epilepsy. Epilepsia. 2012 Dec;53:41–58. doi: 10.1111/epi.12034. Suppl 9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Fu C.H., Iascone D.M., Petrof I., Hazra A., Zhang X., Pyfer M.S. Early seizure activity accelerates depletion of hippocampal neural stem cells and impairs spatial discrimination in an Alzheimer's disease model. Cell Rep. 2019 Jun 25;27(13):3741–3751. doi: 10.1016/j.celrep.2019.05.101. [e4] [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Barry J.M., Sakkaki S., Barriere S.J., Patterson K.P., Lenck-Santini P.P., Scott R.C. Temporal coordination of Hippocampal neurons reflects cognitive outcome post-febrile status epilepticus. EBioMedicine. 2016 May;7:175–190. doi: 10.1016/j.ebiom.2016.03.039. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Han D., Wang Q., Gao Z., Chen T., Wang Z. Clinical features of dementia with lewy bodies in 35 Chinese patients. Transl Neurodegener. 2014 Jan 8;3(1):1. doi: 10.1186/2047-9158-3-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Tramutola A., Lanzillotta C., Barone E., Arena A., Zuliani I., Mosca L. Intranasal rapamycin ameliorates Alzheimer-like cognitive decline in a mouse model of down syndrome. Transl Neurodegener. 2018;7:28. doi: 10.1186/s40035-018-0133-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Morroni F., Sita G., Graziosi A., Turrini E., Fimognari C., Tarozzi A. Neuroprotective effect of caffeic acid phenethyl ester in a mouse model of Alzheimer's disease involves Nrf2/HO-1 pathway. Aging Dis. 2018 Aug;9(4):605–622. doi: 10.14336/AD.2017.0903. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Lau C.G., Zukin R.S. NMDA receptor trafficking in synaptic plasticity and neuropsychiatric disorders. Nat Rev Neurosci. 2007 Jun;8(6):413–426. doi: 10.1038/nrn2153. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Galanopoulou A.S., Moshe S.L. Pathogenesis and new candidate treatments for infantile spasms and early life epileptic encephalopathies: a view from preclinical studies. Neurobiol Dis. 2015 Jul;79:135–149. doi: 10.1016/j.nbd.2015.04.015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Viaccoz A., Desestret V., Ducray F., Picard G., Cavillon G., Rogemond V. Clinical specificities of adult male patients with NMDA receptor antibodies encephalitis. Neurology. 2014 Feb 18;82(7):556–563. doi: 10.1212/WNL.0000000000000126. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Sanz-Clemente A., Gray J.A., Ogilvie K.A., Nicoll R.A., Roche K.W. Activated CaMKII couples GluN2B and casein kinase 2 to control synaptic NMDA receptors. Cell Rep. 2013 Mar 28;3(3):607–614. doi: 10.1016/j.celrep.2013.02.011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Sharma S., Wu S.Y., Jimenez H., Xing F., Zhu D., Liu Y. Ca(2+) and CACNA1H mediate targeted suppression of breast cancer brain metastasis by AM RF EMF. EBioMedicine. 2019 Jun;44:194–208. doi: 10.1016/j.ebiom.2019.05.038. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Nakamura T., Sakaue F., Nasu-Nishimura Y., Takeda Y., Matsuura K., Akiyama T. The autism-related protein PX-RICS mediates GABAergic synaptic plasticity in hippocampal neurons and emotional learning in mice. EBioMedicine. 2018 Aug;34:189–200. doi: 10.1016/j.ebiom.2018.07.011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Nakazawa T., Komai S., Watabe A.M., Kiyama Y., Fukaya M., Arima-Yoshida F. NR2B tyrosine phosphorylation modulates fear learning as well as amygdaloid synaptic plasticity. EMBO J. 2006 Jun 21;25(12):2867–2877. doi: 10.1038/sj.emboj.7601156. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Nakazawa T., Komai S., Tezuka T., Hisatsune C., Umemori H., Semba K. Characterization of Fyn-mediated tyrosine phosphorylation sites on GluR epsilon 2 (NR2B) subunit of the N-methyl-D-aspartate receptor. J Biol Chem. 2001 Jan 5;276(1):693–699. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M008085200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Prybylowski K., Chang K., Sans N., Kan L., Vicini S., Wenthold R.J. The synaptic localization of NR2B-containing NMDA receptors is controlled by interactions with PDZ proteins and AP-2. Neuron. 2005 Sep 15;47(6):845–857. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2005.08.016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Zhang S., Edelmann L., Liu J., Crandall J.E., Morabito M.A. Cdk5 regulates the phosphorylation of tyrosine 1472 NR2B and the surface expression of NMDA receptors. J Neurosci. 2008 Jan 9;28(2):415–424. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.1900-07.2008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Qiu S., Chen T., Koga K., Guo Y.Y., Xu H., Song Q. An increase in synaptic NMDA receptors in the insular cortex contributes to neuropathic pain. Sci Signal. 2013 May 14;6(275):ra34. doi: 10.1126/scisignal.2003778. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Swanger S.A., Chen W., Wells G., Burger P.B., Tankovic A., Bhattacharya S. Mechanistic insight into NMDA receptor dysregulation by rare variants in the GluN2A and GluN2B agonist binding domains. Am J Hum Genet. 2016 Dec 1;99(6):1261–1280. doi: 10.1016/j.ajhg.2016.10.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Loss C.M., da Rosa N.S., Mestriner R.G., Xavier L.L., Oliveira D.L. Blockade of GluN2B-containing NMDA receptors reduces short-term brain damage induced by early-life status epilepticus. Neurotoxicology. 2019 Jan 11;71:138–149. doi: 10.1016/j.neuro.2019.01.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Yuan H., Myers S.J., Wells G., Nicholson K.L., Swanger S.A., Lyuboslavsky P. Context-dependent GluN2B-selective inhibitors of NMDA receptor function are neuroprotective with minimal side effects. Neuron. 2015 Mar 18;85(6):1305–1318. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2015.02.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Kanneganti T.D., Lamkanfi M., Nunez G. Intracellular NOD-like receptors in host defense and disease. Immunity. 2007 Oct;27(4):549–559. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2007.10.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Ting J.P., Lovering R.C., Alnemri E.S., Bertin J., Boss J.M., Davis B.K. The NLR gene family: a standard nomenclature. Immunity. 2008 Mar;28(3):285–287. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2008.02.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Yamada S., Sakakibara S.I. Expression profile of the STAND protein Nwd1 in the developing and mature mouse central nervous system. J Comp Neurol. 2018 Sep 1;526(13):2099–2114. doi: 10.1002/cne.24495. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Cao X., Li L.P., Wang Q., Wu Q., Hu H.H., Zhang M. Astrocyte-derived ATP modulates depressive-like behaviors. Nat Med. 2013 Jun;19(6):773–777. doi: 10.1038/nm.3162. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Yang Q., Zheng F., Hu Y., Yang Y., Li Y., Chen G. ZDHHC8 critically regulates seizure susceptibility in epilepsy. Cell Death Dis. 2018 Jul 23;9(8):795. doi: 10.1038/s41419-018-0842-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Sharma A.K., Reams R.Y., Jordan W.H., Miller M.A., Thacker H.L., Snyder P.W. Mesial temporal lobe epilepsy: pathogenesis, induced rodent models and lesions. Toxicol Pathol. 2007 Dec;35(7):984–999. doi: 10.1080/01926230701748305. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Wang Z., Chen Y., Lu Y., Chen X., Cheng L., Mi X. Effects of JIP3 on epileptic seizures: evidence from temporal lobe epilepsy patients, kainic-induced acute seizures and pentylenetetrazole-induced kindled seizures. Neuroscience. 2015 Aug 6;300:314–324. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroscience.2015.05.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Gu B., Huang Y.Z., He X.P., Joshi R.B., Jang W., McNamara J.O. A peptide uncoupling BDNF receptor TrkB from phospholipase cgamma1 prevents epilepsy induced by status epilepticus. Neuron. 2015 Nov 4;88(3):484–491. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2015.09.032. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Racine R.J. Modification of seizure activity by electrical stimulation. II. Motor seizure. Electroencephalogr Clin Neurophysiol. 1972 Mar;32(3):281–294. doi: 10.1016/0013-4694(72)90177-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Xu X., Shangguan Y., Lu S., Wang W. Tubulin beta-III modulates seizure activity in epilepsy. J Pathol. 2017 Jul;242(3):297–308. doi: 10.1002/path.4903. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Zhang X., Chen G., Lu Y., Liu J., Fang M., Luo J. Association of mitochondrial letm1 with epileptic seizures. Cereb Cortex. 2014 Oct;24(10):2533–2540. doi: 10.1093/cercor/bht118. (New York, NY: 1991) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.McKay S., Ryan T.J., McQueen J., Indersmitten T., Marwick K.F.M., Hasel P. The developmental shift of NMDA receptor composition proceeds independently of GluN2 subunit-specific GluN2 C-terminal sequences. Cell Rep. 2018 Oct 23;25(4):841–851. doi: 10.1016/j.celrep.2018.09.089. [e4] [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Nakajima K., Yin X., Takei Y., Seog D.H., Homma N., Hirokawa N. Molecular motor KIF5A is essential for GABA(A) receptor transport, and KIF5A deletion causes epilepsy. Neuron. 2012 Dec 6;76(5):945–961. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2012.10.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Yang Y., Tian X., Xu D.M., Zheng F.S., Lu X., Zhang Y.K. GPR40 modulates epileptic seizure and NMDA receptor function. Sci Adv. 2018 Oct;4(10) doi: 10.1126/sciadv.aau2357. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Fellin T., Gomez-Gonzalo M., Gobbo S., Carmignoto G., Haydon P.G. Astrocytic glutamate is not necessary for the generation of epileptiform neuronal activity in hippocampal slices. J Neurosci. 2006 Sep 6;26(36):9312–9322. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.2836-06.2006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Levesque M., Avoli M. The kainic acid model of temporal lobe epilepsy. Neurosci Biobehav Rev. 2013 Dec;37(10):2887–2899. doi: 10.1016/j.neubiorev.2013.10.011. Pt 2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Riban V., Bouilleret V., Pham-Le B.T., Fritschy J.M., Marescaux C., Depaulis A. Evolution of hippocampal epileptic activity during the development of hippocampal sclerosis in a mouse model of temporal lobe epilepsy. Neuroscience. 2002;112(1):101–111. doi: 10.1016/s0306-4522(02)00064-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Wang Y., Xu C., Xu Z., Ji C., Liang J., Wang Y. Depolarized GABAergic signaling in Subicular microcircuits mediates generalized seizure in temporal lobe epilepsy. Neuron. 2017 Jul 5;95(1):92–105. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2017.06.004. [e5] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Chang P., Augustin K., Boddum K., Williams S., Sun M., Terschak J.A. Seizure control by decanoic acid through direct AMPA receptor inhibition. Brain: J Neurol. 2016 Feb;139:431–443. doi: 10.1093/brain/awv325. Pt 2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Segal M. Dendritic spines, synaptic plasticity and neuronal survival: activity shapes dendritic spines to enhance neuronal viability. Eur J Neurosci. 2010 Jun;31(12):2178–2184. doi: 10.1111/j.1460-9568.2010.07270.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Muller M., Gahwiler B.H., Rietschin L., Thompson S.M. Reversible loss of dendritic spines and altered excitability after chronic epilepsy in hippocampal slice cultures. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1993 Jan 1;90(1):257–261. doi: 10.1073/pnas.90.1.257. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Pavlowsky A., Gianfelice A., Pallotto M., Zanchi A., Vara H., Khelfaoui M. A postsynaptic signaling pathway that may account for the cognitive defect due to IL1RAPL1 mutation. Current Biol: CB. 2010 Jan 26;20(2):103–115. doi: 10.1016/j.cub.2009.12.030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Lewitus G.M., Konefal S.C., Greenhalgh A.D., Pribiag H., Augereau K., Stellwagen D. Microglial TNF-alpha suppresses cocaine-induced plasticity and behavioral sensitization. Neuron. 2016 May 4;90(3):483–491. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2016.03.030. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Ramirez D.M.O., Crawford D.C. Loss of Doc2-dependent spontaneous neurotransmission augments glutamatergic synaptic strength. J Neurosci. 2017 Jun 28;37(26):6224–6230. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.0418-17.2017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Wyllie D.J., Livesey M.R., Hardingham G.E. Influence of GluN2 subunit identity on NMDA receptor function. Neuropharmacology. 2013 Nov;74:4–17. doi: 10.1016/j.neuropharm.2013.01.016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.McNamara J.O., Huang Y.Z., Leonard A.S. Molecular signaling mechanisms underlying epileptogenesis. Sci STKE: Signal Transduct Knowl Environ. 2006 Oct 10;2006(356):re12. doi: 10.1126/stke.3562006re12. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Noe F., Pool A.H., Nissinen J., Gobbi M., Bland R., Rizzi M. Neuropeptide Y gene therapy decreases chronic spontaneous seizures in a rat model of temporal lobe epilepsy. Brain: J Neurol. 2008 Jun;131:1506–1515. doi: 10.1093/brain/awn079. Pt 6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Correa R.G., Krajewska M., Ware C.F., Gerlic M., Reed J.C. The NLR-related protein NWD1 is associated with prostate cancer and modulates androgen receptor signaling. Oncotarget. 2014 Mar 30;5(6):1666–1682. doi: 10.18632/oncotarget.1850. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Osborn K.E., Shytle R.D., Frontera A.T., Soble J.R., Schoenberg M.R. Addressing potential role of magnesium dyshomeostasis to improve treatment efficacy for epilepsy: a reexamination of the literature. J Clin Pharmacol. 2016 Mar;56(3):260–265. doi: 10.1002/jcph.626. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Tzeng T.C., Hasegawa Y., Iguchi R., Cheung A., Caffrey D.R., Thatcher E.J. Inflammasome-derived cytokine IL18 suppresses amyloid-induced seizures in Alzheimer-prone mice. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2018 Sep 4;115(36):9002–9007. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1801802115. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Paoletti P., Bellone C., Zhou Q. NMDA receptor subunit diversity: impact on receptor properties, synaptic plasticity and disease. Nat Rev Neurosci. 2013 Jun;14(6):383–400. doi: 10.1038/nrn3504. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Groc L., Bard L., Choquet D. Surface trafficking of N-methyl-D-aspartate receptors: physiological and pathological perspectives. Neuroscience. 2009 Jan 12;158(1):4–18. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroscience.2008.05.029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Groc L., Heine M., Cousins S.L., Stephenson F.A., Lounis B., Cognet L. NMDA receptor surface mobility depends on NR2A-2B subunits. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2006 Dec 5;103(49):18769–18774. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0605238103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Salter M.W., Kalia L.V. Src kinases: a hub for NMDA receptor regulation. Nat Rev Neurosci. 2004 Apr;5(4):317–328. doi: 10.1038/nrn1368. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.McCormick D.A., Contreras D. On the cellular and network bases of epileptic seizures. Annu Rev Physiol. 2001;63:815–846. doi: 10.1146/annurev.physiol.63.1.815. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Dani V.S., Chang Q., Maffei A., Turrigiano G.G., Jaenisch R., Nelson S.B. Reduced cortical activity due to a shift in the balance between excitation and inhibition in a mouse model of Rett syndrome. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2005 Aug 30;102(35):12560–12565. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0506071102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Dzhala V.I., Staley K.J. Transition from interictal to ictal activity in limbic networks in vitro. J Neurosci. 2003 Aug 27;23(21):7873–7880. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.23-21-07873.2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Analysis of the differential expression of Nwd1 after AAV injection. (a) A representative western blot for Nwd1 after AAV injection is shown. Compared with AAV-Nwd1-shRNA2 and AAV-Nwd1-shRNA3, AAV-Nwd1-shRNA1 effectively decreased Nwd1 expression in the hippocampus 3 weeks after AAV injection (n=4; **P˂ 0.01; N.S. represents no significance; ANOVA followed by Tukey’s test). (b) Representative fluorescence images of AAV-Nwd1-shRNA expression in the hippocampus in AAV-Nwd1-shRNA-infected mice. Scale bar, 400 μm. (c) Immunofluorescence analysis showing the expression of Nwd1 in hippocampal coronal sections from normal mice and mice with KA-induced SE. Note that Nwd1 is expressed in neurons from normal mice and mice with seizures. Scale bar, 50 μm.

Expression and morphological changes in the hippocampus after KA-induced SE. (a) Representative western blots for Nwd1 in hippocampal lysates from control mice and AAV-GFP- and AAV-Nwd1-shRNA injected mice immediately following 1 hr after SE. (b) Quantitative analysis of the data in (a). The level of Nwd1 protein decreased in AAV-Nwd1-shRNA-treated mice compared with control and AAV-GFP-treated mice (n=4; **P˂ 0.01; N.S. represents no significance; ANOVA followed by Tukey’s test). (c) Nissl staining showing Nissl substance loss and pyramidal neuron loss in the CA1, CA3 and dentate gyrus (DG) areas after KA-SE in vehicle- and AAV-GFP-treated mice. Note that this hippocampal damage was attenuated by AAV-Nwd1-shRNA. The red rectangles represent high magnification images. Scale bar: Hippocampus, 400 μm; CA1, DG, 50 μm; CA3, 100 μm. (d) Immunofluorescence analysis showing the expression of NeuN (green) and GFAP (red) in hippocampal coronal sections after AAV injection in KA-SE mice. Scale bar, 50 μm. (e) Quantitative analysis of the number of NeuN-positive cells in the CA1 region of the hippocampus in each group. Note the reduced number of neurons in vehicle- and AAV-GFP-treated mice. However, the number of neurons was attenuated in AAV-Nwd1-shRNA-treated mice. The error bars indicate the SEM (n = 3 per group; neurons from 10 brain slices were counted for each animal; * P˂ 0.05, *** P˂ 0.001).

Supplemental Information for Inhibition of Nwd1 activity attenuates neuronal hyperexcitability and GluN2B phosphorylation in the hippocampus.