Abstract

Background

Monthly intravenous immunoglobulin (IVIG) and weekly subcutaneous immunoglobulin (SCIG) have been regarded as therapeutically equivalent treatments for primary immunodeficiency diseases (PIDD). Immunoglobulin G (IgG) trough level is used as a monitoring measure for infection prevention.

Objective

A systematic review and meta-analysis were performed to elucidate the relationship between IgG dosing, trough IgG levels with overall infection incidence in patients with PIDD receiving IVIG and SCIG therapy.

Methods

Medline, EMBASE, Cochrane, Central, and Scopus were searched for studies published from Jan 2010–June 2018, fulfilling the inclusion criteria. DerSimonian and Laird random-effects method were used to pool the difference of IgG trough levels. Random-effect meta-regression was used to evaluate infection incidence per 100 mg/dl IgG trough increase though IVIG and SCIG.

Results

Out of 24 observational studies included, 11 compared IgG trough levels among SCIG and IVIG (mean difference: 73.4 mg/dl, 95% CI: 31.67–119.19 mg/dl, I2 = 45%, p = 0.05), favoring weekly SCIG. For every 100 mg/dl increase in the trough, a linear trend of decreased incidence rates of infection was identified in SCIG patients (p = 0.03), but no similar trend was identified in trough levels vs. infection rates for patients receiving IVIG (p = 0.67).

Conclusion

In our study, weekly SCIG attained a higher trough level in comparison to monthly IVIG. Higher SCIG troughs were associated with lower infection rates, while IVIG troughs demonstrated no relationship.

Keywords: PIDD, Primary immunodeficiency disease, IgG trough, IVIG, SCIG

Introduction

Immunoglobulin G (IgG) replacement therapy is the mainstay of treatment in many primary immunodeficiency diseases (PIDD) associated with humoral immune defects, including common variable immunodeficiency disease (CVID), congenital hypogammaglobulinemia and agammaglobulinemia.1 While intravenous immunoglobulin (IVIG) was the most common mode of replacement in 1980–1990, subcutaneous IgG (SCIG) administration has become increasingly common in clinical practice since the 1990s.2 Both IVIG and SCIG have been regarded therapeutically equivalent (have same efficacy for prevention of bacterial infections) in patients with PIDD3,4 and choice of the use of IVIG vs. SCIG has to take into account the comparative advantages and disadvantages between these for a given patient. For example, advantages of SCIG being fewer systemic adverse events,4,5 improved quality of life5,6 and stable IgG levels6,7 and disadvantages being more local infusion sites reactions accounting for adverse events8, 9, 10, 11 and requirement of frequent infusions (weekly vs. monthly).4,5

It is unclear if there are universally accepted threshold IgG levels that correlate with adequate protection from severe infections. Serum IgG concentrations ≥500 mg/dl following IgG therapy have been recommended for adequate protection from serious infections in PIDDs.12, 13, 14 The serum IgG trough level, defined as concentration preceding the next dose of immunoglobulin (Ig) infusion, has been regarded as an important guide to therapy.15 Several recent studies have shown higher serum IgG concentrations, resulting from higher intravenous IgG and subcutaneous IgG dosing regimens, associated with infection prevention and decreasing infection-associated morbidity.13,16,17 Data from earlier studies have endorsed IgG trough level of 500 mg/dl as an appropriate initial minimum target for infection prevention in PIDD.14,18 However, subsequent clinical evidence has prompted recommendations for higher target levels of >800 mg/dl19 and 650–1000 mg/dl20 in recent clinical guidelines. Due to inconsistent trough levels, a recommendation to individualize treatment plans based on symptoms and infections has been proposed.3 Studies have also suggested no significant differences in efficacy or adverse reaction rates between subcutaneous and intravenous immunoglobulin treatment.4

In this systematic review and meta-analysis, we sought to compare IVIG vs. SCIG in PIDD patients and its effects on IgG trough levels, the overall incidence of infection and serious infections (including pneumonia) to help guide clinicians in appropriate clinical decision making.

Methods

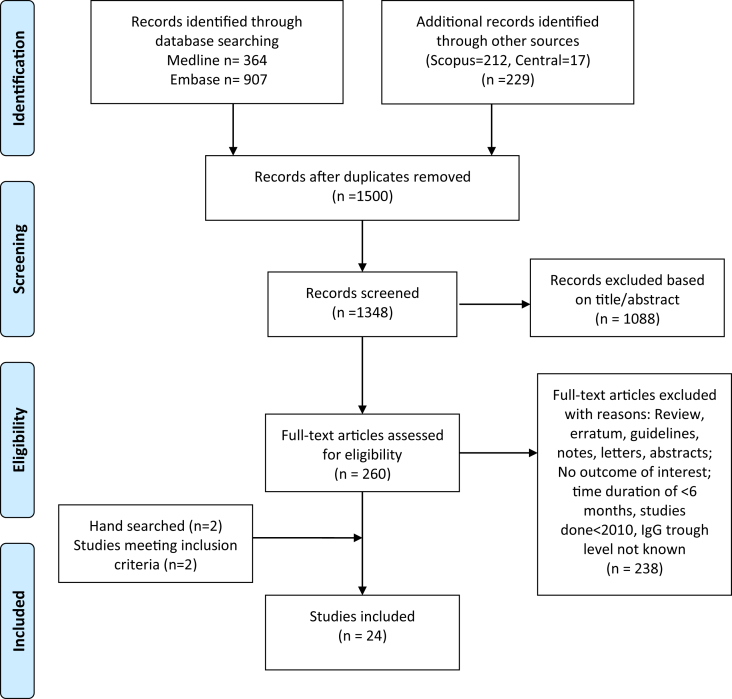

The preferred reporting items for systematic reviews and meta-analyses (PRISMA) statement as recommended by the Cochrane Collaboration for reporting systematic reviews21 was used (Fig. 1). This systematic review included studies published from Jan 1, 2010, to May 30, 2018. A meta-analysis on studies earlier than 2010 was already carried out by Orange et al.;13 we focused our review on studies after 2010 to cover newer studies since the recent advancements in the treatment of these diseases. Searches of MEDLINE, EMBASE, Cochrane Library, and Scopus databases were carried out to identify eligible studies. A combination of subject headings (MeSH, EMTREE) and text words was used for each concept. Search terms and synonyms for "immunologic deficiency" and "immunoglobulins" were combined in the search with "AND" using Boolean logic. Synonyms for immune deficiency included "immunologic deficiency syndromes", "common variable immunodeficiency", "dysgammaglobulinemia", "agammaglobulinemia", "hypogammaglobulinemia" (the text words allowed for both American and British spellings). Synonyms for immunoglobulins included "immunoglobulins", “intravenous”, “subcutaneous” abbreviations of IVIG, SQIG, as well as specific brand names such as Carimune, Gammagard, and subject headings which included specific routes of injection such as immunoglobulins/intravenous or immunoglobulins/subcutaneous were included.

Fig. 1.

Flow chart describing systematic research and study selection process

The eligibility criteria for this systematic review were (1) human subjects with a diagnosis of PIDD undergoing IgG treatment; (2) reported outcomes comparing IVIG, SCIG, or different dosage/forms of IVIG/SCIG; (3) Documented IgG trough level; (4) Studies showing an outcome of interest (overall infection, pneumonia/serious infection, or hospitalization rates). Studies without documented therapy studies not reporting any outcome of interest or definitions of those outcomes, and studies without a comparator were excluded from our analysis. Conference extracts were excluded. The language was restricted to English.

Study abstracts were screened by two investigators (PS and AJ), full-text articles were reviewed for those that fulfilled eligibility criteria and irrelevant articles were excluded. Disputes were settled with mutual agreement. To minimize data duplication as a result of multiple reporting, we compared articles from the same investigator. Relevant data were extracted by two investigators (PS and AJ) and checked by another (PK).

From each study, we extracted and tabulated details on the study source, design, patient with PIDD, type of PIDD included, mean age in years, percentage of female patients, percentage of CVID patients, the region of study, the total population of study and duration of the study (Table 1). Furthermore, we extracted the details on treatment, including the type of treatment IgG used, comparison group, dosing protocol, IgG trough level, pneumonia rate, overall infection rate, days of hospitalizations, days missed from school/work and adverse events per patient-year (Table 2).

Table 1.

Baseline Characteristics of clinical studies included in systematic review and meta-analysis.

| SN | Studies | Study design | Region | Total Population of Study | Study duration | Treatment IgG used (Brand name) | Comparison | No. of patients (n) | Mean age in years (SD/range) | Female gender (n, %) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Aydiner 201529 | Prospective, observational | Turkey | 16 | 10 months | SCIG | 5–10% IVIG vs. SCIG | 16 | 7.5 (0–33 years) | 7 (43.7%) |

| 2 | Berger 201030 | Open-label, uncontrolled trial | Germany | 51 (adults = 42, children = 9), (3–66 years) | 12 months | 16% SCIG (Vivaglobin) | Historic IVIG vs. | 51 | 37.8 ± 19.40 | 30 (58.8%) |

| 16% SCIG | 31 | 10.4 ± 20.24 | 18 (58.1%) | |||||||

| 3 | Ballow 201631 | Phase IV, multi-center, open-label study | USA | 24 (2–16 years) | 12 months | 5% DIF IVIG (Flebogamma) | Historic IVIG vs. 5% DIF IVIG | 24 | 9.0 (2.0–16.0) | 5 (20.8%) |

| 4 | Bezrodnik 20138 | Observational, prospective/retrospective, open-label multicenter study | Argentina | 15 (6–18 years) | 36 weeks | 16% SCIG (Beriglobina P) | 16% SCIG | 15 | 10.6 (3.7) | 4 (27%) |

| 5 | Bezrodnik 201432 | Observational, descriptive and ambispective study | Argentina | 32 (8 months - 40 years) | 36 weeks | 16% SCIG (Beriglobina P) | Historic IVIG vs. SCIG (15 via pump and 2 via push) | 32 | 11 (8–40) | 15 (46.9%) |

| 6 | Borte 20179 | Prospective, non-controlled clinical trial | Europe | 49 (>2 years) | 52 weeks | IVIG 10% (Kiovig)/SCIG 16% (Subcuvia) | IVIG 10%/SCIG 16% (period1) vs. | 33 (IVIG), 16 (SCIG16%) | 17 (2–67) | 19 (38.8%) |

| SCIG 20% | SCIG 20% (period2) | 49 (SCIG 20%) | ||||||||

| 7 | Borte 201710 | Prospective, open-label, non-controlled, non-randomized, multicenter, phase 3 study | USA and Europe | 51 (13 children, 12 adolescents, 26 adults) | 12 months | IVIG 10% (Panzyga) | 3-weekly IVIG then IVIG 10% | 21 | 26.2 ± 21.2 | 14 (66.7%) |

| 4-weekly IVIG then IVIG 10% | 30 | 27.2 ± 18.2 | 19 (63.3%) | |||||||

| 8 | Borte 201133 | Prospective, open-label, multicenter, single-arm, phase III | Europe | 18 (2–11 years) and 5 (12–15 years) and 28 (16–64 years) | 12 weeks (wash-in/wash-out period)+28 weeks efficacy period | SCIG 20% (Hizentra) | IVIG vs. 20%SCIG | 51 | 7.2 ± 2.5 (children), 14 ± 1 (adolescents), 34.1 ± 12.7 (adults) | 5 (27.8%) children, 0 adolescents, 11 (39.3%) adults |

| 9 | Haddad 20126 | Comparative study for Open-label, multi-center, single-arm design | USA and Europe | EU = 46 | 12 weeks wash-in/wash-out period + efficacy period (28 weeks in Europe and 52 weeks in USA) | SCIG 20% (Hizentra) | SCIG 20% same dose as historic IVIG | 46 | 21.5 ± 15.6 | 15 (33%) |

| USA = 38 | SCIG 20% 1.5 x dose as historic IVIG | 38 | 36.3 ± 19.5 | 21 (55%) | ||||||

| 10 | Hagan 201011 | Prospective, open-label, multicenter, single-arm, phase III | USA | 49 (5–72 years) | 12 weeks wash-in/wash-out period and 12-month efficacy period | SCIG 20% (IgPro20) | IVIG then SCIG 20% | 49 | 36.3 ± 19.52 | 21 (55.3%) |

| 11 | Jolles 201134 | Prospective, open-label, multicenter, single-arm, phase III | Europe | 53 (17 < 12 years, 5 < 16 years,31 ≥ 16 years). | 12-week wash-in/wash-out period, 28 weeks efficacy period | SCIG 20% (Hizentra) | Switch from IVIG to SCIG 20% | 46 (ITT), 23 (PPK) | 21.5 ± 15.6 | 15 (32.6%) |

| 12 | Kanegane 201435 | Prospective, multicenter, open-label, single-arm, phase III | Japan | 25 (2–12 years = 11, 12–16 years = 8, 16–65 years = 26), | 12-week wash-in/wash-out period with 12-week efficacy period | IgPro20 SCIG (Hizentra) | Switch from IVIG to SCIG 20% | 24 (ITT), 21 (PPK) | 17.5 (3–58) ITT, 19(3–58) PPK | 9 (37.5%) ITT, 7 (33.3%) PPK |

| 13 | Krivan 201636 | Open-label, prospective, multicenter, single-arm study | Europe | 62 (2–61 years), 36 adults and 26 pediatrics | 12 months | IVIG (IqYmune) | Switch from IVIG to IqYmune | 62 | 27.4 (2–61) | 19 (30.6%) |

| 14 | Melamed 201637 | Open-label, multi-center, non-randomized phase 4 study | USA(7), Chile(1), Israel (1) | 25 (3–16 years) | 12 months | 5% IVIG (Gammaplex) | Switch from IVIG to IVIG 5% | 14 on 21-day infusion and 11 on 28-day infusion | 10.4 ± 3.84 | 6 (24%) |

| 15 | Moy 201038 | Prospective, open-label, multi-center, non- comparative | USA | 50 (≥3 years) | 12 months | 5% IVIG with and 5 g d-sorbitol (Gammaplex 5%) | Switch from IVIG to 5% IVIG | 22 on 21-day and 28 on 28-day infusion schedule | 44 ± 19.10 | 24 (48%) |

| 16 | Patel 201539 | Retrospective chart review | USA | 88 (0-<2 years = 34, 2–5 years = 54) | 45.5 months | SCIG 20% (Hizentra) | Historic Hizentra use | 88 | 34 months (2-59) | 35 (40%) |

| 17 | Quinti 201117 | Prospective, multi-center | Italy | 302 (CVID + XLA) | 3.8 years (CVID) 5.8 years (XLA) |

IVIG | IVIG in CVID vs. XLA | 302 | 28.7 ± 18.4 (3–68 years) (CVID) | NA |

| 4.9 ± 6.2 (16 days-40.9 years) (XLA) | ||||||||||

| 18 | Stein 201640 | Prospective, open-label, single-arm, multicenter, historically controlled, phase III | USA and Canada | 40 (2–70 years)- 39 in US and 6 in Canada | 12 months | 10% IVIG (Kedrion) | Historic Hizentra use (mean age of initiation of Hizentra 34 months) | 88 | 34 months (2-59) | 35 (40%) |

| 19 | Suez 201641 | Prospective, open-label clinical trial | USA and Canada | 74 (≥2 years) | 52 weeks | IVIG 10% and SCIG 20% | 74 | 39.9 ± 20.7 | 13 (29%) | |

| 20 | Viallard 201742 | Prospective, multicenter, non-randomized, open-label | France | 22 (18–70 years) | 9 months | 5% lyophilized IVIG (Tegeline) and IV Ig new generation (ClairYg IGNG) | Period 1-IVIG 10% then SCIG 205 in period 2, 3 and 4 | 22 | 36 (3–83) | 37 (48.1%) |

| 21 | Vultaggio 201543 | Prospective, observational, multicenter | Italy | 50 (group A >14 years = 43, Group B ≤ 14 years = 7) | 24 months | SCIG 16% (Vivaglobin) | IVIG/SCIG vs. SCIG 16% | 50 | 41.9 ± 12.2 | 8 (36.4%) |

| 22 | Wasserman 201244 | Open-label, phase III, efficacy and pharmacokinetic study | USA | 63 (6–11 years = 4, 12–17 years = 6, 18–64 years = 44, >65 years = 9) | 12 months | IVIG 10% (Biotest) | IVIG vs. SCIG 16% | 50 | 31.7 ± 15.7 | 19 (38%) |

| 23 | Wasserman 201245 | Prospective, multicenter, open label, phase III | USA and Canada | 87 (2–12 years = 14, ≥12 years = 73) | 14–18 months | SCIG/IVIG preceded by rHyPH20 [recombinant human hyaluronidase (IGHy)] | IVIG 10% infusion in 21 day vs. 28 day | 87 | 41.2 ± 19.68 | 32 (50.8%) |

| 24 | Wasserman 20167 | Prospective, open-label, non-controlled, multi-center studies, phase III trial [Extension of earlier study (2012)] | USA and Canada | 63 (<18 years = 15, ≥18 years = 48) | 30 months | SCIG preceded by rHyPH20 [recombinant human hyaluronidase (IGHy)] | SCIG/IVIG + rHyPH20 vs. IVIG/SCIG alone | 87 | 35 (4–78) | 43 (49.4%) |

Legend: IgG- Immunoglobulin, n = number, SD- Standard Deviation, IVIG- Intravenous Immunoglobulin, SCIG- Subcutaneous Immunoglobulin, NA-not available, EU = Europe, USA= United States of America, ITT- Intent to treat, PPK- per-protocol pharmacokinetic, CVID= Common variable immunodeficiency disease, XLA = X-linked agammaglobulinemia

Table 2.

IgG dose, IgG trough level and outcomes of Primary Immunodeficiency disease patients in included clinical studies.

| SN. | Studies | Type of IgG used | Dosing protocol, Mean(range) mg/Kg/week | IgG trough level (Mean ± SD) mg/dl | Severe infections n (rate/patient/year) | Overall infection (n, CI)-annual rate per patient | Days of hospitalization (n, Mean ± SD) | Days missed from work/school (n, Mean ± SD) | Adverse events/patient/year |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Aydiner 201529 | IVIG | 330–1250 mg/kg/wk | 976 ± 564 mg/dl | 0 | 7 events in 4 pts in 10 months | na | na | na |

| SCIG | 300–430 mg/kg/wk | 1025 ± 409 mg/dl | |||||||

| 2 | Berger 201030 | IVIG | 100–200 mg/kg/wk | 914.8 ± 273.37 mg/dl | 0.03 | 3.42 | na | 4.5/subject/year | 27.5 |

| 16% SCIG | 878 ± 234.77 mg/dl | ||||||||

| 3 | Ballow 201631 | IVIG | 300–800 mg/kg/wk | 800–1000 mg/dl | 1 episode | 0.051 | 0.2 ± 1.1 | 6.2 ± 17.7 | 20.2 |

| 5% IVIG | |||||||||

| 4 | Bezrodnik 20138 | IVIG | 556 mg/kg/month (420–870) | 960.2 mg/dl | 3 episodes in IVIG/1 in SCIG | 1.4 | 0 | na | na |

| 16% SCIG | 139 mg/kg/wk (105–181) | 1317 mg/dl (wk16), 1309.2 mg/dl (wk 24) and 1231.5 mg/dl (wk 36) | 0.4 | 0 | na | 0.14 | |||

| 5 | Bezrodnik 201432 | IVIG (48 weeks) | na | 1005.33 ± 419.420 mg/dl | 4 episodes | 2–7 | na | na | 0.13 |

| 16% SCIG (9 months) | 133 mg/kg/wk (100–192) | 1205 ± 457.990 mg/dl | 3 episodes | 1–2 | na | na | 0.02 | ||

| 6 | Borte 20179 | Period 1-IVIG 10% for 13 wk/SCIG 16% for 12 wks. | 125 ± 42 mg/kg/week (20% SCIG) | IVIG 10% = 720 mg/dl SCIG 16% = 897 mg/dl | 0 IVIG, 1(0.27) SCIG 16%) | 6.29 rate (IVIG), 8.92 rate (SCIG 16%), 4.38 (SCIG 20%) | 1 (0.12) IVIG,2 (0.54) SCIG 16% | 90 (10.69) IVIG/187(50.42) SCIG | 0.058 |

| Period 2-SCIG 20% for 52 wk | SCIG 20% = 827 mg/dl | 1(0.022) | 200(4.38) | 7(0.15)-SCIG | 710 (15.55) | ||||

| 7 | Borte 201710 | 10% IVIG (/3 weeks) | 485 mg/kg/month | 1100–1220 mg/dl | 3.68 (overall) 4.19 (3 weekly)) |

na | 37 absences (61.95%) | Serious AE 13% (4 weekly) vs. 5% in 4 weekly | |

| 10% IVIG (/4 weeks) | 810–870 mg/dl | 3.33 (4 weekly) | 1 (0.08) | 3.64 | |||||

| 8 | Borte 201133 | IVIG/SCIG | 200–800 mg/kg/wk | 694 mg/dl (c), 790 mg/dl (a), 781 mg/dl (ad) g/l | 0 | 4.77/5.18 (a)/5.47 (ad) | 8.36(c),0(a),0.63(ad) | 1.7 (c), na (a), na (ad) | 0.04(c),0.035 (a),0.08(ad)/infusion |

| 20% SCIG | 129.9 mg/kg/wk -children(c), 113.7 mg/kg/wk- adolescents (a) and 114.3 mg/kg/wk- adults (ad) |

786 mg/dl (c), 791 mg/dl (a), 831 mg/dl (ad) | 0 | ||||||

| 9 | Haddad 20126 | 20% SCIG (1:1) EU | 120 mg/kg/wk | 810 ± 144 mg/dl | 0 | 5.18 | 3.48 | 8 | 0.59 events/infusion (1:1) |

| 20% SCIG (1.5:1) USA | 210 mg/kg/wk | 1254 ± 322 mg/dl | 0 | 2.76 | 0.2 | 2.06 | 0.06 in 1:1 | ||

| 10 | Hagan 201011 | 20% SCIG | 179.6–224.3 mg/kg (IgPro20) | 1210–1290 mg/dl | 0 | 2.76 | 0.2 | 2.06 | local AE = 0.592, other than local AE = 0.043 |

| 11 | Jolles 201134 | IVIG | Pre study = 702 mg/dl | 1(wash out) = 0.03 events/patient/year | 5.18 | 3.48 | 8 | 0.177/infusion | |

| 20% SCIG | 120 ± 35.72 mg/kg/wk (20% SCIG) | On infusion = 809 mg/dl | |||||||

| 12 | Kanegane 201435 | IVIG | 77.3 ± 30.5 mg/kg/month | 653 ± 140 mg/dl (IVIG) | 0 | 2.98 | 0.55 | 3.48 | 0.461/infusion |

| 20% SCIG | 87.8 ± 35.2 mg/kg/wk SCIG | 715 ± 151 mg/dl (SCIG) | |||||||

| 13 | Krivan 201636 | IqYmune | 220–970 mg/kg | 579 ± 203 mg/dl | 1 (0.017) | 3.79 | 0.89 | 1.01 | 0.45/infusion |

| 773/- 236 mg/dk (IVIG) | |||||||||

| 14 | Melamed 201637 | IVIG 5% 21-day infusion | 300–800 mg/kg/wk | 21-day infusion = 987–1083 mg/dl | 2 (0.09) | 3.08 | 3.5 | 1.1 | 0.39/infusion |

| IVIG 5% 28-day infusion | 28-day infusion = 822–882 mg/dl | ||||||||

| 15 | Moy 201038 | IVIG 5% | 469.4 mg/kg/month (21-day infusion) 466.2 mg/kg/month (28-day infusion) |

21-day infusion = 936–1240 mg/dl | 0 | 3.07 | 2 days | 8.73 | 1 AE/3 infusions |

| 28-day infusion = 833–1140 mg/dl | |||||||||

| 16 | Patel 201539 | SCIG 20% | 674 mg/kg/wk (260–2000) 552 mg/kg/month (IVIG) |

794 mg/dl (on IVIG) and 943 mg/dl (IGSC 20%) | 0.03 | 0.067 rate | na | na | 41 (47%) local AEs |

| 17 | Quinti 201117 | IVIG | CVID- 398 ± 167 mg/kg/wk | CVID-667 ± 176 mg/dl | 0.06–0.1 episodes patient-year | na | na | na | na |

| XLA-608 ± 273 mg/kg/wk | XLA-758 ± 202 mg/dl | 0.03–0.11 episodes patient-year | |||||||

| 18 | Stein 201640 | 10% IVIG | 501.7 mg/kg/month | 923.9 mg/dl | 2 (0.04) | 2.9 | 0.6 | 2.8 | 44(98%)- 450 events |

| 19 | Suez 201641 | IVIG 10% and SCIG 20% | 222 ± 71 mg/kg/wk | 1523 mg/dl with IGSC and 1200 mg/dl in IVIG 10% in 3 weeks | 0 | 3.86 in IVIG | 0.02 | 1.16 | 0.036/infusion |

| 2.41 in SCIG | |||||||||

| 20 | Viallard 201742 | Tegeline | 442 mg/kg/month (286–608) | Tegeline 805 ± 134 mg/dl | Tegeline-0 | Tegeline-4.35 (0–21.8) | Tegeline-0 | Tegeline-8.8 (6.4–11.9) | Tegeline-0.09 |

| ClairYg | ClairYg 917 ± 172 mg/dl | ClairYg-0 | ClairYg-4.3(0–15.1) | ClairYg-0 | ClairYg-0.3(0.1–0.9) | ClairYg-0.08 | |||

| 21 | Vultaggio 201543 | IVIG | Maintenance of total monthly dose of historic IVIG split into four weekly doses of SCIG | Baseline 635 ± 242.8 mg/dl | 5 (0.056) | 33/39 patients (84.6%)- infection | 1.93 ± 4.08 (IVIG) | 15.27 ± 23.17 (IVIG) | Local reactions (14/50 = 28%) |

| SCIG 16% | 671 ± 217.5 mg/dl | 0.64 ± 2.94 (SCIG) | 2.26 ± 4.45 (SCIG) | ||||||

| 22 | Wasserman 201244 | IVIG 10% | 500 mg/kg/wk (254–1029) | 1076 ± 254 mg/dl (606–1780 mg/dl) in 21-days | 2 (0.035) | 2.6 (2.3–2.7) | 0.21 | 2.28 | 937 events |

| 943 ± 215 mg/dl (487–2250) in 28-days | |||||||||

| 23 | Wasserman 201245 | IVIG/SCIG + IGHy vs. IVIG/SCIG alone | IGHy at 75U/g IgG followed by IgG 10% at 155 mg/kg/wk | <12 yrs = 995 mg/dl, >12 yrs 1070 mg/dl | 2(0.025) | 2.97 (IGHy) 4.51 (IVIG) |

0.02 (IGHy) vs. 0.06 (IVIG) | 0.28 (IGHy) vs. 0.23 (IVIG) | local AE = 0.199/infusion (IGHy) vs. 0.011/infusion (IVIG) |

| <12 yrs = 963 mg/dl, >12 yrs = 1040 mg/dl | |||||||||

| 24 | Wasserman 20167 | SCIG + IGHy vs. SCIG | 155 ± 53 mg/kg/week | 1135 mg/dl (2 week), 1195 mg/dl(3week), 983 mg/dl (4 week) | 5 (0.03) | 2.99 | 0.12 | 5.75 | 10.68/subjects' year |

Legend: IgG- Immunoglobulin, n = number, SD- Standard Deviation, wk-week, yrs-years IVIG- Intravenous Immunoglobulin, SCIG- Subcutaneous Immunoglobulin, na-not available, EU = Europe, USA= United States of America, ITT- Intent to treat, PPK- per-protocol pharmacokinetic, CVID= Common variable immunodeficiency disease, XLA = X-linked agammaglobulinemia, IGHy-recombinant human hyaluronidase

Study quality was formally evaluated by two investigators (PS and AD) using a modified Newcastle-Ottawa Quality Assessment Scale22 for observational studies. Any discrepancies were resolved by a third author (PK) (Supplementary File 1).

The outcomes from individual studies were calculated with RevMan, version 5.3 (Cochrane Collaboration, Oxford, United Kingdom). The Inverse-Variance method was used to compare the IVIG and SCIG trough levels. Risk Ratios (RRs) and 95% confidence intervals (CIs) were estimated using a random-effects method to control the heterogeneity as their assumption accounts for the presence of variability among the studies.23 The I2 statistic was used to estimate the percentage of heterogeneity among the studies. I2 values < 30% were considered a low heterogeneity, 30%–60% as moderate, and >60% as high.24 Peto odds ratio was used when the event rate was <1%. DerSimonian and Laird random-effects method was used to pool the difference of IgG trough levels along with random-effect meta-regression to evaluate infection incidence per 100 mg/dl IgG trough increase through IVIG and SCIG. A p-value of <0.05 was used as a level of significance. Publication bias was assessed by visual assessment of funnel plots (Supplementary File 2).

Results

Our study included 24 studies that met our eligibility criteria, of which 21 were prospective, 2 were ambispective and 1 was a retrospective study (Table 1). Twelve studies were conducted in the United States, 10 in European countries (2 with the US), 4 in Canada (with the US), 2 in Argentina, 1 in Japan and Turkey each, and a multinational study by the US along with Chile and Israel. Treatment IgG products used and study durations were included. The mean patient age was 23.8 years in 24 studies, with 10 studies including those <18 years and 14 including those >18 years of age. Seven studies had more than 50% females, but males comprised the majority of the patient population overall. Disease types resulting in PIDD by the study are shown in Supplemental Table 2. CVID was the predominant PIDD with 5 studies showing >80% of CVID in the affected patient population, followed by XLA.

IVIG had been used in all the studies as a historical form of IgG administration and was compared with SCIG in 15 studies. IVIG administration frequency was every 3 or 4 weeks, whereas, SCIG dose was given weekly. Trough levels calculated in studies varied in terms of timing, with most of the levels drawn prior to the next IVIG and SCIG infusion. After reviewing the quality of studies, 11 studies were compared in the meta-analysis for trough levels as depicted in the forest plot (Fig. 2). Inclusion criteria of the studies stipulated documented diagnosis of PIDD requiring IgG therapy with a stable dose and trough level. However, in one study done by Borte et al., patients above 2 years of age with PIDD requiring 0.3–1 g/kg IgG for ≥ 3 months with serum IgG trough 5 g/l only were included. Patients with chronic infections with Hepatitis B, C or HIV, on antibiotics, abnormal liver and renal function tests, severe neutropenia, thrombotic episodes, malignancy, currently receiving immunosuppression, pregnant or nursing were excluded in most studies. Reported details on criteria for pneumonia diagnosis during the course of treatment with IVIG and SCIG therapy were limited, with some studies reporting the diagnosis based on history, chest X-ray, physical exam and need for hospitalization. Pneumonia was also sometimes reported as a "serious infection" separating it from the overall infections diagnosed during the treatment period. However, due to the low number of pneumonia diagnoses reported in the studies, regression analysis was focused on overall infections and serious infections. The annual rate of infection per patient was calculated, when not provided, for statistical analysis. Days of hospitalization, days missed from school and work, adverse events from the IVIG and SCIG therapy were reviewed and included if reported (Table 2).

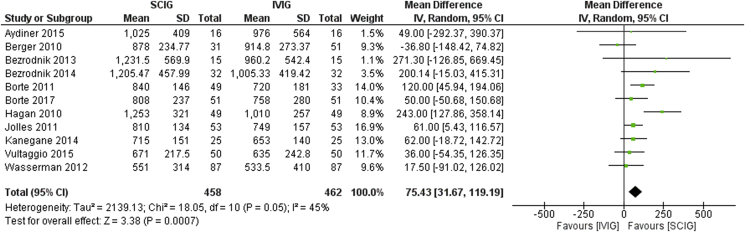

Fig. 2.

Trough levels in SCIG vs. IVIG

Among the total 24 studies, 13 with IVIG therapy and 11 with SCIG therapy were reviewed owing to the availability of data required for comparative study and meta-analysis. Eleven studies which compared IVIG and SCIG therapy were included in the initial meta-analysis. Higher mean trough level attainment was evident in the SCIG group as compared to IVIG with a mean difference of 75.43 (CI 31.67–119.19), with moderate heterogeneity (I2 = 45%) (Fig. 2).

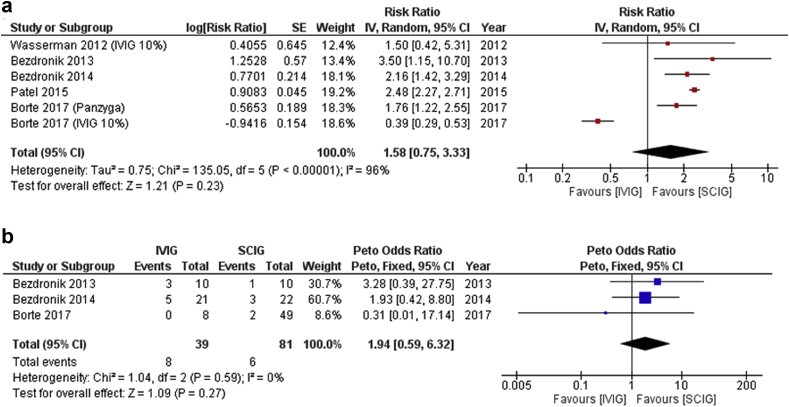

Among 6 studies comparing IVIG vs. SCIG in terms of the incidence of infection, the difference in risk of overall infections (Risk difference = 1.58, 95% CI: 0.75–3.33, p = 0.23, I2 = 96%) or serious infections was not statistically significant (Peto odds ratio = 1.94, 95% CI: 0.59–6.32, (p = 0.59, I = 0%), but a clinically relevant difference could not be ruled out (Fig. 3a and b).

Fig. 3.

(a) and (b). Infection rates and serious infection rates in IVIG vs. SCIG

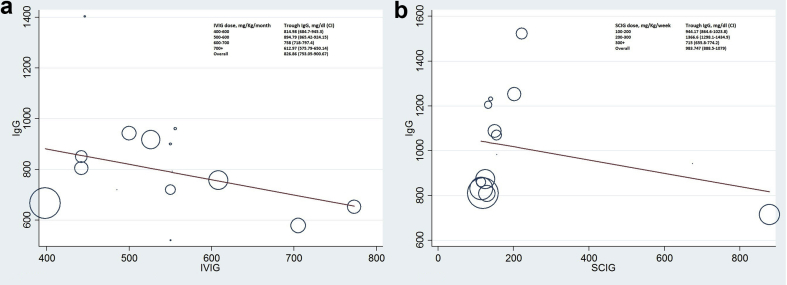

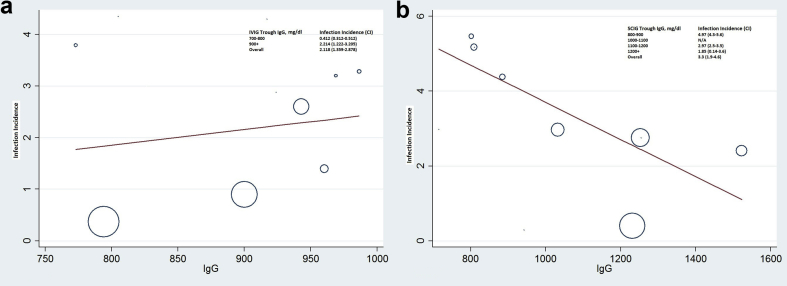

Random-effects meta-regression analysis was used to analyze the increase in IgG trough level with a concomitant increase in IVIG and SCIG dose. No notable linear relationship with dose-dependent trough level was seen with either IVIG or SCIG therapy (Fig. 4a and b). However, across the studies included for regression analysis of IVIG and SCIG trough vs. infection incidence (Fig. 5a and b), each additional 100 mg/dl trough attained through SCIG was associated with a reduction in pneumonia incidence rate, as displayed in Fig. 5b. No significant trend was apparent within the IVIG trough range as depicted in Fig. 5a.

Fig. 4.

(a) and (b). Effect of IVIG dose (mg/kg) on trough IgG level (mg/dl) and effect of SCIG dose (mg/kg) on trough IgG level (mg/dl). Each data point corresponds to a single observation period in a patient group of an included study. Abbreviations, C, 95% confidence interval; IVIG, intravenous immunoglobulin; SCIG, subcutaneous immunoglobulin

Fig. 5.

(a) and (b). Effect of IgG trough level (mg/dl) on infection incidence per patient-year in SCIG and IVIG groups. Each data point corresponds to a single observation period in a patient group of an included study. Abbreviations, C, 95% confidence interval; IVIG, intravenous immunoglobulin; SCIG, subcutaneous immunoglobulin

Discussion

Our study shows higher IgG trough levels in patients on SCIG vs. IVIG therapy. Among the 11 studies included in our meta-analysis of IVIG vs. SCIG trough level, consistently higher trough levels were observed with SCIG. A study done by Chapel et al. had also reported higher trough level in patients on SCIG therapy compared to IVIG, but doses differing as per infusion centers, differences in route of administration with no statistical evaluation of achieved serum IgG level make the comparison difficult.4 Similar findings were reported by Bonagura et al. as well.25 These findings may be due to the fact that pharmacokinetics of IgG tends to differ when smaller doses are given more frequently as compared to large boluses given on a monthly basis. SCIG therapy has been noted to have lower peaks and higher IgG troughs. A total IgG dose divided into three or four equal portions in weekly intervals is expected to have less variation and fluctuations of IgG trough level, approximately 900 mg/dl difference in peak and trough level after IVIG infusion in comparison to 100 mg/dl difference of the same after SCIG infusion.26 Another study by Radinski advocated that frequent SCIG dosing allows better maintenance of consistent serum IgG levels.27 Although our study favored higher level of IgG trough on SCIG therapy, increment in the level per dose increase did not have a linear correlation, and a similar finding was observed with IVIG therapy as well. This could have resulted from the variation of timing in measuring trough levels in different studies. Although the measurement of IgG trough level was done prior to infusion in most studies, some did not mention the exact timing of level drawn. Whether trough levels should be used as a guide for treatment remains controversial. Data from earlier studies have endorsed IgG trough level of 500 mg/dl as an appropriate initial minimum target for infection prevention in PIDD.18 However, subsequent clinical evidence has prompted recommendations for higher target levels of >800 mg/dl19 and 650–1000 mg/dl20 in recent clinical guidelines. Due to inconsistent trough levels, preference for individualized treatment plan based on symptoms and infection prevention are considered.3 More studies are required to ascertain pharmacokinetic parameters such as maximal concentration in serum (Cmax), the time necessary to reach concentration after complete infusion (Tmax) and volume of distribution.

Similarly, a clear positive association of higher trough levels with lower infection rates was seen with SCIG in our meta-regression. Infection incidence rate with trough 800–900 mg/dl at 4.97 (CI 4.3–5.8) precipitously decreased to 1.85 (CI 0.14–3.6) and with trough level of 1200 + mg/dl which was statistically significant at p = 0.03. This relation, however, was not seen with IVIG therapy. Although we included 24 studies in our systematic review, we could only include 11 studies in our meta-analysis owing to lack of patient-level data. An earlier meta-analysis done by Orange et al. had also noted a significant reduction in pneumonia incidence (incidence rate ratio - 0.726, CI 0.658–0.801), with a 27% reduction in pneumonia incidence for each 100 mg/dl increment in trough IgG.13 While this study's analysis was limited to pneumonia incidence, authors did suggest the advantages of higher trough levels benefitting overall infection prevention as well. Comparison of overall or serious infections between IVIG vs. SCIG was not significantly different, however, a clinically significant difference cannot be ruled out due to a low number of patients and wide confidence interval seen.

The primary strength of this study is that it includes a large group of studies to quantify the relationship of infection rate and IgG trough levels in PIDD patients, along with the relationship of dose vs. trough level in IVIG as well as SCIG modes of treatment. Our results may have been confounded by a focused presentation on the efficacy of SCIG product, as most study trials were developed by pharmaceutical companies. Another caveat could be an effect seen by several studies in the past which noted serum IgG levels to rise continuously for months when previously untreated or under-treated patients received SCIG therapy.26,28 Although the study includes studies done in several countries with large patient data, most studies are cohort studies, which limits the overall strength of evidence.

Our study did not show a significant difference in overall infections or serious infections with IVIG vs. SCIG, but a clinically significant difference cannot be ruled out. Based on our observation, weekly SCIG attained a higher trough level in comparison to monthly IVIG. Higher SCIG troughs were associated with lower infection rates, while IVIG troughs demonstrated no relationship. More randomized controlled trials are required to look at the effect of dosing with serum IgG trough levels, and more importantly its effect on infection prevention.

Financial disclosures

Authors have nothing to disclose.

Grant support

The project was supported by grant T32 GM08685 (Pragya Shrestha) from National Institutes of Health and CTSA Grant Number UL1 TR002377 from the National Center for Advancing Translational Science (NCATS) (Paras Karmacharya).

Conflict of interest statement

The authors declare no conflicts of interest in preparing this article.

Consent for publication

All authors have agreement to publish the work.

Ethics approval

This review did not require ethics approval.

Availability of data and materials

Additional details regarding the data are available in the supplemental file for the manuscript.

Contributors

PS conceived, designed and wrote the initial manuscript. PK, AD and AYJ provided intellectual input and revised the final manuscript. WZ performed statistical analysis. PS is the overall guarantor for the final manuscript.

Acknowledgements

We would like to thank our librarian,Patricia J. Erwin, M.L.S. for help with the extensive search strategy.

Footnotes

Full list of author information is available at the end of the article

Supplementary data to this article can be found online at https://doi.org/10.1016/j.waojou.2019.100068.

Appendix A. Supplementary data

The following is the Supplementary data to this article:

References

- 1.Aghamohammadi A., Moin M., Farhoudi A. Efficacy of intravenous immunoglobulin on the prevention of pneumonia in patients with agammaglobulinemia. FEMS Immunol Med Microbiol. 2004;40(2):113–118. doi: 10.1016/S0928-8244(03)00304-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Shabaninejad H., Asgharzadeh A., Rezaei N., Rezapoor A. A comparative study of intravenous immunoglobulin and subcutaneous immunoglobulin in adult patients with primary immunodeficiency diseases: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Expert Rev Clin Immunol. 2016;12(5):595–602. doi: 10.1586/1744666X.2016.1155452. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Ballow M. Optimizing immunoglobulin treatment for patients with primary immunodeficiency disease to prevent pneumonia and infection incidence: review of the current data. Ann Allergy Asthma Immunol. 2013;111(6 Suppl):S2–S5. doi: 10.1016/j.anai.2013.06.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Chapel H.M., Spickett G.P., Ericson D., Engl W., Eibl M.M., Bjorkander J. The comparison of the efficacy and safety of intravenous versus subcutaneous immunoglobulin replacement therapy. J Clin Immunol. 2000;20(2):94–100. doi: 10.1023/a:1006678312925. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Gardulf A., Andersen V., Björkander J. Subcutaneous immunoglobulin replacement in patients with primary antibody deficiencies: safety and costs. Lancet. 1995;345(8946):365–369. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(95)90346-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Haddad E., Berger M., Wang E.C.Y., Jones C.A., Bexon M., Baggish J.S. Higher doses of subcutaneous IgG reduce resource utilization in patients with primary immunodeficiency. J Clin Immunol. 2012;32(2):281–289. doi: 10.1007/s10875-011-9631-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Wasserman R.L., Melamed I., Stein M.R. Long-term tolerability, safety, and efficacy of recombinant human hyaluronidase-facilitated subcutaneous infusion of human immunoglobulin for primary immunodeficiency. J Clin Immunol. 2016;36(6):571–582. doi: 10.1007/s10875-016-0298-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Bezrodnik L., Gómez Raccio A., Belardinelli G. Comparative study of subcutaneous versus intravenous IgG replacement therapy in pediatric patients with primary immunodeficiency diseases: a multicenter study in Argentina. J Clin Immunol. 2013;33(7):1216–1222. doi: 10.1007/s10875-013-9916-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Borte M., Kriván G., Derfalvi B. Efficacy, safety, tolerability and pharmacokinetics of a novel human immune globulin subcutaneous, 20%: a Phase 2/3 study in Europe in patients with primary immunodeficiencies: IGSC 20% in patients with PIDD in Europe. Clin Exp Immunol. 2017;187(1):146–159. doi: 10.1111/cei.12866. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Borte M., Melamed I.R., Pulka G. Efficacy and safety of human intravenous immunoglobulin 10% (Panzyga®) in patients with primary immunodeficiency diseases: a two-stage, multicenter, prospective, open-label study. J Clin Immunol. 2017;37(6):603–612. doi: 10.1007/s10875-017-0424-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Hagan J.B., Fasano M.B., Spector S. Efficacy and safety of a new 20% immunoglobulin preparation for subcutaneous administration, IgPro20, in patients with primary immunodeficiency. J Clin Immunol. 2010;30(5):734–745. doi: 10.1007/s10875-010-9423-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Bonilla F.A., Khan D.A., Ballas Z.K. Practice parameter for the diagnosis and management of primary immunodeficiency. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2015;136(5):1186–1205. doi: 10.1016/j.jaci.2015.04.049. e78. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Orange J.S., Grossman W.J., Navickis R.J., Wilkes M.M. Impact of trough IgG on pneumonia incidence in primary immunodeficiency: a meta-analysis of clinical studies. Clin Immunol. 2010;137(1):21–30. doi: 10.1016/j.clim.2010.06.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Roifman C.M., Levison H., Gelfand E.W. High-dose versus low-dose intravenous immunoglobulin in hypogammaglobulinaemia and chronic lung disease. Lancet. 1987;1(8541):1075–1077. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(87)90494-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Yong P.L., Boyle J., Ballow M. Use of intravenous immunoglobulin and adjunctive therapies in the treatment of primary immunodeficiencies. Clin Immunol. 2010;135(2):255–263. doi: 10.1016/j.clim.2009.10.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Lucas M., Lee M., Lortan J., Lopez-Granados E., Misbah S., Chapel H. Infection outcomes in patients with common variable immunodeficiency disorders: relationship to immunoglobulin therapy over 22 years. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2010;125(6):1354–1360. doi: 10.1016/j.jaci.2010.02.040. e4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Quinti I., Soresina A., Guerra A. Effectiveness of immunoglobulin replacement therapy on clinical outcome in patients with primary antibody deficiencies: results from a multicenter prospective cohort study. J Clin Immunol. 2011;31(3):315–322. doi: 10.1007/s10875-011-9511-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Hernandez-Trujillo H.S., Chapel H., Lo Re V. Comparison of American and European practices in the management of patients with primary immunodeficiencies. Clin Exp Immunol. 2012;169(1):57–69. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2249.2012.04588.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Orange J.S., Belohradsky B.H., Berger M. Evaluation of correlation between dose and clinical outcomes in subcutaneous immunoglobulin replacement therapy. Clin Exp Immunol. 2012;169(2):172–181. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2249.2012.04594.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Roifman C.M., Berger M., Notarangelo L.D. Management of primary antibody deficiency with replacement therapy: summary of guidelines. Immunol Allergy Clin N AM. 2008;28(4):875–876. doi: 10.1016/j.iac.2008.07.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Beller E.M., Glasziou P.P., Altman D.G. PRISMA for abstracts: reporting systematic reviews in journal and conference abstracts. PLoS Med. 2013;10(4) doi: 10.1371/journal.pmed.1001419. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Ottawa Hospital Research Institute. http://www.ohri.ca/programs/clinical_epidemiology/oxford.asp. Accessed September 23, 2018.

- 23.Schmidt F.L., Oh I.-S., Hayes T.L. Fixed- versus random-effects models in meta-analysis: model properties and an empirical comparison of differences in results. Br J Math Stat Psychol. 2009;62(Pt 1):97–128. doi: 10.1348/000711007X255327. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Higgins J.P., Green S., editors. Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions. John Wiley & Sons, Ltd; Chichester, UK: 2008. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Bonagura V.R., Marchlewski R., Cox A., Rosenthal D.W. Biologic IgG level in primary immunodeficiency disease: the IgG level that protects against recurrent infection. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2008;122(1):210–212. doi: 10.1016/j.jaci.2008.04.044. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Berger M. Subcutaneous immunoglobulin replacement in primary immunodeficiencies. Clin Immunol. 2004;112(1):1–7. doi: 10.1016/j.clim.2004.02.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Radinsky S., Bonagura V.R. Subcutaneous immunoglobulin infusion as an alternative to intravenous immunoglobulin. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2003;112(3):630–633. doi: 10.1016/s0091-6749(03)01781-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Gaspar J., Gerritsen B., Jones A. Immunoglobulin replacement treatment by rapid subcutaneous infusion. Arch Dis Child. 1998;79(1):48–51. doi: 10.1136/adc.79.1.48. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Karakoc Aydiner E., Kiykim A., Baris S., Ozen A., Barlan I. Use of subcutaneous immunoglobulin in primary immune deficiencies. Türk Pediatri Arşivi. February 2016:8–14. doi: 10.5152/TurkPediatriArs.2016.3058. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Berger M., Murphy E., Riley P., Bergman G.E. Improved quality of life, immunoglobulin G levels, and infection rates in patients with primary immunodeficiency diseases during self-treatment with subcutaneous immunoglobulin G. South Med J. 2010;103(9):856–863. doi: 10.1097/SMJ.0b013e3181eba6ea. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Ballow M., Pinciaro P.J., Craig T. Flebogamma® 5 % DIF intravenous immunoglobulin for replacement therapy in children with primary immunodeficiency diseases. J Clin Immunol. 2016;36(6):583–589. doi: 10.1007/s10875-016-0303-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Liliana B. Subcutaneous IgG replacement therapy by push in 32 patients with primary immunodeficiency diseases in Argentine. Clin Exp Pharmacol. 2014;04(02) [Google Scholar]

- 33.Borte M., Pac M., Serban M. Efficacy and safety of Hizentra®, a new 20% immunoglobulin preparation for subcutaneous administration, in pediatric patients with primary immunodeficiency. J Clin Immunol. 2011;31(5):752–761. doi: 10.1007/s10875-011-9557-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Jolles S., Bernatowska E., de Gracia J. Efficacy and safety of Hizentra® in patients with primary immunodeficiency after a dose-equivalent switch from intravenous or subcutaneous replacement therapy. Clin Immunol. 2011;141(1):90–102. doi: 10.1016/j.clim.2011.06.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Kanegane H., Imai K., Yamada M. Efficacy and safety of IgPro20, a subcutaneous immunoglobulin, in Japanese patients with primary immunodeficiency diseases. J Clin Immunol. 2014;34(2):204–211. doi: 10.1007/s10875-013-9985-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Krivan G., Chernyshova L., Kostyuchenko L. A multicentre study on the efficacy, safety and pharmacokinetics of IqYmune®, a highly purified 10% liquid intravenous immunoglobulin, in patients with primary immune deficiency. J Clin Immunol. 2017;37(6):539–547. doi: 10.1007/s10875-017-0416-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Melamed I.R., Gupta S., Stratford Bobbitt M., Hyland N., Moy J.N. Efficacy and safety of Gammaplex ® 5% in children and adolescents with primary immunodeficiency diseases: gammaplex ® 5% in children and adolescents with PID. Clin Exp Immunol. 2016;184(2):228–236. doi: 10.1111/cei.12760. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Moy J.N., Scharenberg A.M., Stein M.R. Efficacy and safety of a new immunoglobulin G product, Gammaplex®, in primary immunodeficiency diseases: gammaplex® in PID. Clin Exp Immunol. 2010;162(3):510–515. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2249.2010.04247.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Patel N.C., Gallagher J.L., Ochs H.D. Subcutaneous immunoglobulin replacement therapy with Hizentra® is safe and effective in children less than 5 Years of age. J Clin Immunol. 2015;35(6):558–565. doi: 10.1007/s10875-015-0190-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Stein M., Nemet A., Kumar S. Efficacy, safety, and tolerability of Kedrion 10% IVIG in primary immunodeficiency. LymphoSign Journal. 2016;3(3):99–109. [Google Scholar]

- 41.Suez D., Stein M., Gupta S. Efficacy, safety, and pharmacokinetics of a novel human immune globulin subcutaneous, 20 % in patients with primary immunodeficiency diseases in North America. J Clin Immunol. 2016;36(7):700–712. doi: 10.1007/s10875-016-0327-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Viallard J.-F., Brion J.-P., Malphettes M. A multicentre, prospective, non-randomized, sequential, open-label trial to demonstrate the bioequivalence between intravenous immunoglobulin new generation (IGNG) and standard IV immunoglobulin (IVIG) in adult patients with primary immunodeficiency (PID) Rev Med Interne. 2017;38(9):578–584. doi: 10.1016/j.revmed.2017.05.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Vultaggio A., Azzari C., Milito C. Subcutaneous immunoglobulin replacement therapy in patients with primary immunodeficiency in routine clinical practice: the VISPO prospective multicenter study. Clin Drug Investig. 2015;35(3):179–185. doi: 10.1007/s40261-015-0270-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Wasserman R.L., Church J.A., Stein M. Safety, efficacy and pharmacokinetics of a new 10% liquid intravenous immunoglobulin (IVIG) in patients with primary immunodeficiency. J Clin Immunol. 2012;32(4):663–669. doi: 10.1007/s10875-012-9656-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Wasserman R.L., Melamed I., Stein M.R. Recombinant human hyaluronidase-facilitated subcutaneous infusion of human immunoglobulins for primary immunodeficiency. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2012;130(4):951–957. doi: 10.1016/j.jaci.2012.06.021. e11. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

Additional details regarding the data are available in the supplemental file for the manuscript.