Abstract

Liver Kinase B1 (LKB1) plays a key role in cellular metabolism by controlling AMPK activation. However, its function in dendritic cell (DC) biology has not been addressed. Here, we find that LKB1 functions as a critical brake on DC immunogenicity, and when lost, leads to reduced mitochondrial fitness and increased maturation, migration, and T cell priming of peripheral DCs. Concurrently, loss of LKB1 in DCs enhances their capacity to promote output of regulatory T cells (Tregs) from the thymus, which dominates the outcome of peripheral immune responses, as suggested by increased resistance to asthma and higher susceptibility to cancer in CD11cΔLKB1 mice. Mechanistically, we find that loss of LKB1 specifically primes thymic CD11b+ DCs to facilitate thymic Treg development and expansion, which is independent from AMPK signalling, but dependent on mTOR and enhanced phospholipase C β1-driven CD86 expression. Together, our results identify LKB1 as a critical regulator of DC-driven effector T cell and Treg responses both in the periphery and the thymus.

Subject terms: Innate immunity, Cell biology, Immunology

Introduction

Dendritic cells (DCs) form a central link between innate and adaptive immunity and are crucial for initiation and regulation of T cell responses both under inflammatory conditions as well as during steady state. DCs are also key regulators of immune homeostasis and maintenance of immune tolerance by governing the development of regulatory T cells (Tregs). Tregs can be induced in the thymus, referred to as thymic-derived Tregs (tTregs), as well as in the periphery (pTregs) from naïve T cells.1 tTregs are characterized by a TCR repertoire that predominantly recognizes self-antigens and are important to maintain self-tolerance and to prevent auto-immunity.2 pTregs, on the other hand, are thought to primarily govern tolerogenic responses against foreign antigens and microbes.3 Whereas the mechanisms through which pTregs are induced in the periphery by DCs are fairly well characterized,4 the pathways through which DCs control tTreg development and homeostasis are still poorly defined.

There is a growing appreciation that activation and effector function of immune cells, including that of DCs, are dependent on reprogramming of intracellular metabolic pathways.5,6 Primarily in vitro studies have shown that an immunogenic phenotype of DCs induced by Toll-like receptor (TLR) activation depends on a glycolysis-driven anabolic program,7,8 while a more catabolic type of metabolism is linked to quiescent and tolerogenic DCs, characterized by increased fatty acid oxidation and mitochondrial oxidative phosphorylation (OXPHOS).7,9,10 However, to what extent catabolic vs. anabolic metabolism of DCs regulates the balance between tolerogenic and immunogenic properties of DCs under physiological conditions, remains to be determined.

The tumor suppressor liver kinase B1 (LKB1, encoded by Stk11) is a bioenergetic sensor that controls cell metabolism and growth. LKB1 has several downstream targets, but it is most well known for being a key upstream activator of AMP-activated Kinase (AMPK). Under low intracellular ATP levels, as a result of insufficient oxygen and/or nutrient availability to fuel mitochondrial OXPHOS and glycolysis to generate ATP, LKB1 phosphorylates AMPK. This allows AMPK to activate catabolic mitochondrial metabolism and to suppress anabolic sugar and lipid metabolic pathways to conserve energy and restore cellular bioenergetic homeostasis.11 The role of LKB1 as a tumor suppressor has been well appreciated as germline mutations in Stk11 are responsible for the inherited cancer disorder Peutz-Jeghers Syndrome12 and as LKB1 is commonly mutated in various types of cancer.13 More recently a picture is emerging that LKB1 also plays a key role in regulation of the immune system. For example, LKB1 was shown to be required for haematopoietic stem cell maintenance14,15 and T cell development in the thymus.16 It is also crucial for metabolic and functional fitness of Tregs17,18 and can dampen pro-inflammatory responses in macrophages.19 However, the physiological role of LKB1 in regulating metabolic and functional properties of DCs has not yet been explored.

We here report that loss of LKB1 in DCs results in disruption of mitochondrial fitness and enhanced immunogenic properties of these cells in vivo. Surprisingly, however, loss of LKB1 also greatly enhances the capacity of CD11b+ DCs in the thymus to promote the generation of functional Tregs, through enhanced mTOR signalling and phospholipase C β1-driven CD86 expression. Our findings reveal a central role for LKB1 in DC metabolism and immune homeostasis, as it — depending on the context — acts as a critical brake on the immunogenic and tolerogenic properties of DCs.

Results

LKB1 promotes mitochondrial fitness in DCs and retains them in a quiescent state

To study the physiological role of LKB1 in the biology of DCs, Stk11flox/flox mice were crossed to Itgaxcre mice to generate mice with a selective deficiency for LKB1 in CD11c+ cells. cDCs from the conditional knockout mice (CD11cΔLKB1) showed a near complete loss of LKB1 expression (Fig. 1a). Furthermore, all major splenic DC subsets were present in similar frequencies and numbers as in Cre- littermates (CD11cWT) (Fig. 1b, c; Supplementary information, Fig. S1a, b), suggesting loss of LKB1 has no major impact on DC homeostasis. Given the importance of LKB1 in cellular metabolism, we next assessed several mitochondrial parameters of, and glucose uptake by, splenic DC subsets. Consistent with previous reports, we found that cDC1s displayed higher mitochondrial mass, membrane potential and reactive oxygen species production compared to cDC2s20,21 (Fig. 1d). Interestingly, a marked defect in mitochondrial mass, membrane potential and reactive oxygen species production could be observed in both cDC subsets and pDCs from CD11cΔLKB1 mice in spleen (Fig. 1d; Supplementary information, Fig. S2a) and LNs (Supplementary information, Fig. S2b, c), while glucose uptake was enhanced in the cDC2s due to LKB1 deficiency (Fig. 1e). We additionally characterized in vivo Flt3L-expanded splenic cDC subsets metabolically (Supplementary information, Fig. S3a). Although similar to unexpanded splenic cDCs, these cells displayed defects in several mitochondrial parameters (Supplementary information, Fig. S3b). No significant alterations in mitochondrial respiration could be observed due to loss of LKB1 (Supplementary information, Fig. S3d, e). Moreover, consistent with increased glucose uptake by unexpanded splenic cDC2s, glucose uptake (Supplementary information, Fig. S3c) and glycolytic rates (Supplementary information, Fig. S3f, g) were increased in Flt3L-expanded cDC2s, but not in cDC1s, from CD11cΔLKB1 mice. Moreover, bone marrow-derived DCs (GMDCs) generated from CD11cΔLKB1 mice showed metabolic alterations, characterized by reduced baseline mitochondrial respiration and spare respiratory capacity (Supplementary information, Fig. S4), suggesting an important role for LKB1 in maintaining mitochondrial fitness in various DCs subsets.

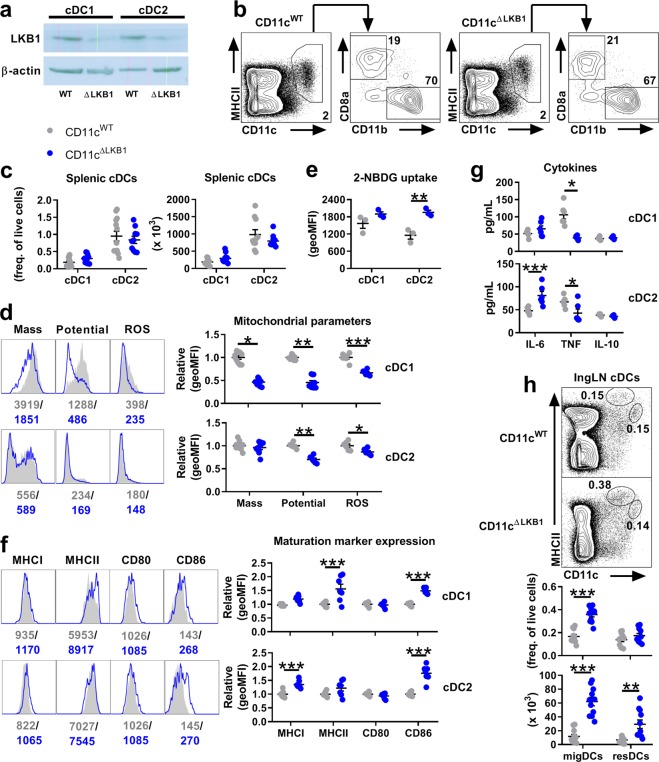

Fig. 1.

LKB1 promotes mitochondrial fitness in DCs and retains them in a quiescent state. a Flt3L-expanded cDC1s and cDC2s were sorted from spleens of WT (CD11cWT) and Itgaxcre Stk11fl/fl (CD11cΔLKB1) mice before immunoblot analysis of LKB1 and β-actin. b, c Splenic cDC1s and cDC2s were identified as CD11c+MHCII+CD8a+ (or CD11c+MHCII+XCR1+) and CD11c+MHCII+11b+ (CD11c+MHCII+CD172a+) respectively as shown in representative flow cytometric plots ((b), see Supplementary information, Figure S1a for full gating). Percentages ((c), left) and absolute numbers ((c), right) were quantified. d Representative histograms (left) and relative expression (right) of mitochondrial mass, membrane potential and ROS production in splenic cDC1s (top) and cDC2s (bottom), as analysed by flow cytometry. e Uptake of a fluorescent glucose analogue by splenic cDCs detected using flow cytometry. f Representative histograms (left) and relative surface expression (right) of indicated markers by splenic cDC1s (top) and cDC2s (bottom). g Flt3L-expanded splenic cDC1s (top) and cDC2s (bottom) were sorted from spleens and put into culture. 16 h later, supernatants were harvested and analysed for indicated cytokines by cytokine bead array. h Migratory and resident DCs in the inguinal LN were identified as CD11c+MHCIIhi and CD11chiMHCII+ respectively as shown in representative flow cytometric plots (top), and percentages (middle) and absolute numbers (bottom) were quantified. Data are pooled from 3 (c, h), 2 (d, f, g) 2 or 1 (e) (independent) experiment(s) with three to four mice and shown as mean ± SEM; *p < 0.05, **p < 0.01, ***p < 0.001

Phenotypically, cDCs, but not pDCs, from CD11cΔLKB1 mice displayed an increased expression of several activation markers in spleen and LNs (Fig. 1f; Supplementary information, Fig. S5a-c) and had an altered cytokine production profile at steady state with lower TNF production but higher IL-6 secretion by cDC2s (Fig. 1g). It should be noted that we cannot rule out the possibility that the absence of a strong phenotype in pDCs may be the result of incomplete deletion of LKB1, due to intermediate CD11c and thereby Cre expression. In addition, analysis of peripheral lymph nodes (LNs) revealed a significantly increased accumulation of migratory DCs. On the other hand, frequencies and numbers of resident DC populations were in general not increased by LKB1 deficiency (Fig. 1h; Supplementary information, Fig. S5d, e), except for the number of inguinal LN-resident DCs (Fig. 1h), which went along with an increase in overall cell numbers in this LN in CD11cΔLKB1 mice (Supplementary information, Fig. S5f). Together, with strongly upregulated CCR7 expression by migratory DCs (Supplementary information, Fig. S5g), this points towards enhanced baseline migration towards lymphoid organs by tissue-derived DCs when LKB1 is lost. Indeed, subcutaneously injected GMDCs from CD11cΔLKB1 mice, which also expressed higher levels of CCR7 than their WT counterparts (Fig. 2a), accumulated more rapidly in draining LNs (Fig. 2b, c). Together, this suggests that LKB1 signalling is important for restricting spontaneous activation and migration of DCs under steady state conditions.

Fig. 2.

LKB1 limits the T cell-priming capacity of DCs. a Surface expression of CCR7 on GM-CSF-cultured BM-derived DCs (GMDCs) from CD11cWT and CD11cΔLKB1 mice as analysed by flow cytometry. b, c CTV-labeled GMDCs from CD11cWT and CD11cΔLKB1 mice were injected into footpads of WT mice. 24 h later, migrated GMDCs were quantified in draining popliteal LNs by flow cytometry. d–k GMDCs were stimulated for 6 hours with OVA and LPS and then, injected into footpads of WT mice. 7 days later, T cell responses were evaluated in draining popliteal LNs by flow cytometry (e–k). e Frequencies of CD44+CD62L- effector CD8+ T cells are shown in representative flow cytometry plots (left) and enumerated (right). f Frequencies of CD44+ OVA-specific CD8+ T cells, based on KbOva tetramer, are shown in representative flow cytometry plots (left) and enumerated (right). g Popliteal LN cells were stimulated with PMA/Ionomycin in the presence of Brefeldin A and CD8+ T cells were analysed for expression of indicated cytokines as shown in representative flow cytometry plots (left) and enumerated (right). h Frequencies of CD44+CD62L- effector CD4+ T cells are shown in representative flow cytometry plots (left) and enumerated (right). i–k Popliteal LN cells were stimulated as in (g) and CD4+ T cells were analysed for expression of indicated cytokines as shown in representative flow cytometry plots (left) and enumerated (right). Data are pooled from 4 independent experiments (a), 2 independent experiments with four mice (c) or 1 experiment with five mice (e–k) and shown as mean ± SEM; *p < 0.05, **p < 0.01, ***p < 0.001

LKB1 limits the T cell-priming capacity of DCs

Next, we aimed to address how the loss of LKB1 would affect the T cell-priming capacities of DCs. To this end, we adoptively transferred GMDCs, pulsed in vitro with OVA and LPS, into footpads of recipient mice and analysed the T cell response in the draining LNs 7 days later (Fig. 2d). Compared to WT GMDCs, immunization with LKB1-deficient GMDCs resulted in a significantly greater expansion of effector CD44+CD62L-CD4+ and CD8+ T cells (Fig. 2e, h) and OVA-specific CD8+ T cells (Fig. 2f). Furthermore, enhanced production of IFN-γ by CD8+ T cells (Fig. 2g) and IFN-γ and IL-17 by CD4+ T cells (Fig. 2i–k) was also observed. Likewise, OVA-pulsed primary splenic cDC1s and cDC2s isolated from CD11cΔLKB1 mice induced stronger in vitro proliferation of CD8+ (OT-I) and CD4+ (OT-II) T cells, respectively (Supplementary information, Fig. S6a–c), of which the latter also produced more IL-4 and IL-17 (Supplementary information, Fig. S6d). These data indicate that LKB1, by limiting DC activation in a cell-intrinsic manner, functions as a brake on the overall T cell-priming capacities of DCs.

CD11cΔLKB1 mice have impaired responses to immunization and are less capable of controlling tumor growth due to a DC-extrinsic immune suppressive environment

Given the increased pro-inflammatory properties of LKB1-deficient DCs, we hypothesized that CD11cΔLKB1 mice would mount stronger immune responses in response to immunization. However, unexpectedly, in a model of subcutaneous immunization (Fig. 3a), CD11cΔLKB1 mice showed impaired antigen-specific CD8+ T cell responses (Fig. 3d) and reduced production of IFN-γ by both CD8+ (Fig. 3b) and CD4+ T cells (Fig. 3c). Consistent with these data, we found that CD11cΔLKB1 mice challenged with a B16 melanoma tumor (Fig. 3e), for which both CD4+ and CD8+ T cell responses are required for anti-tumor immunity,22 had a more rapid outgrowth of those tumors than CD11cWT mice (Fig. 3f). These data together suggest that despite the pro-inflammatory signature of DCs present in CD11cΔLKB1 mice, these mice display an immune-suppressed phenotype.

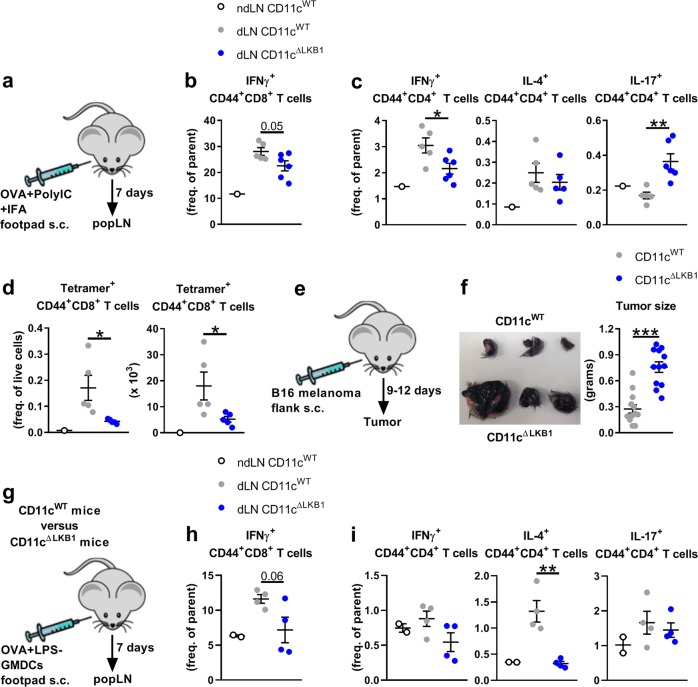

Fig. 3.

CD11cΔLKB1 mice have impaired responses to immunization and are less capable of controlling tumor growth. a–d CD11cWT and CD11cΔLKB1 mice were immunized with Poly (I:C) and OVA in incomplete Freund’s adjuvant into the footpad. 7 days later, T cell responses were evaluated in draining popliteal LNs by flow cytometry. b, c Popliteal LN cells were stimulated with PMA/Ionomycin in the presence of Brefeldin A and CD8+ T cells (b) and CD4+ T cells (c) were analysed for expression of indicated cytokines by flow cytometry. d Percentages (left) and absolute numbers (right) of CD44+ OVA-specific CD8+ T cells, based on KbOva tetramer, were quantified by flow cytometry. e, f B16 melanoma tumour cells were injected into the flank of CD11cWT and CD11cΔLKB1 mice and tumour weight was determined 9 to 12 days later. g–i GMDCs were stimulated for 6 h with OVA and LPS and then, injected into footpads of CD11cWT and CD11cΔLKB1 mice. 7 days later, T cell responses were evaluated in draining popliteal LNs by flow cytometry (h, i). Popliteal LN cells were stimulated as in (c) and CD8+ T cells (h) and CD4+ T cells (i) were analysed for expression of indicated cytokines. Data are pooled from 4 independent experiments with three to four mice (f) or 1 experiment with four to five mice (b–d, h, i) and shown as mean ± SEM; *p < 0.05, **p < 0.01, ***p < 0.001

To reconcile these at first sight contradictory observations, we hypothesized that there may be additional changes in the overall immunological profile of CD11cΔLKB1 mice outside the DC compartment that counteract the increased immunogenic properties of LKB1-deficient DCs, and could account for the immune-suppressed phenotype. To explore the possibility that the immune-suppressive environment could be DC extrinsic in these mice, we adoptively transferred WT GMDCs, pulsed in vitro with OVA and LPS, into footpads of either CD11cWT or CD11cΔLKB1 mice and subsequently analysed T cell responses in these mice (Fig. 3g). We observed a reduced ability to prime effector T cell responses by WT DCs in the CD11cΔLKB1 mice compared to CD11cWT mice, as evidenced by lower cytokine production in primed T cells (Fig. 3h, i), providing support for the existence of an DC-extrinsic immune-suppressive environment in CD11cΔLKB1 mice.

LKB1-deficiency in DCs results in a dramatically expanded functional Treg pool in vivo that is associated with protection against allergic asthma

Given the well-established critical role of Tregs in regulation and suppression of immune responses, we wondered whether alterations in the Treg compartment could provide an explanation for the immune-suppressed phenotype of CD11cΔLKB1 mice. When we analysed the T cell pool of naïve CD11cΔLKB1 mice, we found a dramatically expanded pool, both in frequencies and numbers, of Foxp3+ Tregs in spleen and peripheral LNs relative to CD11cWT mice (Fig. 4a). In comparison to Tregs from CD11cWT mice, these Tregs expressed increased levels of immune-suppressive markers glucocorticoid-induced TNFR family-related gene (GITR), cytotoxic T-lymphocyte-associated antigen 4 (CTLA4) and activation marker CD44, but lower levels of CD25 (Fig. 4b), an expression profile that has been linked to effector (e)Tregs.23 Moreover, on a per cell basis, Tregs from CD11cΔLKB1 mice showed an enhanced capacity to suppress bystander T cell proliferation in vitro (Fig. 4c, d). To further characterize the Tregs from these mice, we analyzed and compared the TCR repertoire of CD25hi CD4+ Tregs from CD11cΔLKB1 and CD11cWT mice. The distribution of the most frequently used V and J genes from both TCRα and β was similar between Tregs from CD11cΔLKB1 and CD11cWT mice (Supplementary information, Fig. S7), suggesting no major differences between the TCR repertoire of the Tregs from the two mouse strains. This indicates that 1) the expanded Treg pool in CD11cΔLKB1 mice is not due to selective outgrowth of Tregs with particular antigen specificity and 2) the increased suppressive function of Tregs in CD11cΔLKB1 mice is not the result of altered antigen specificity, but more likely a consequence of potentiated antigen-independent bystander suppression due to increased expression of immunoregulatory markers.24–26

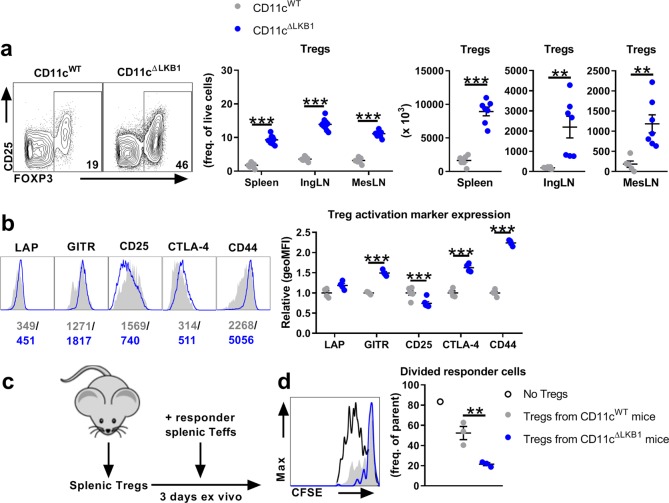

Fig. 4.

LKB1-deficiency in DCs results in a dramatically expanded functional Treg pool in vivo. a Tregs in spleens, inguinal LNs and mesenteric LNs from CD11cWT and CD11cΔLKB1 mice were identified as CD3+CD4+FOXP3+ as shown in representative flow cytometry plots from the spleen (left). Frequencies (middle) and absolute numbers (right) were quantified by flow cytometry. b Representative histograms (left) and relative surface expression (right) are shown of indicated markers by splenic Tregs. c, d T cell suppression assay, in which the ability of CD25high CD4+ T cells sorted from spleens of CD11cWT and CD11cΔLKB1 mice to suppress anti-CD3- and splenocyte-induced proliferation of CFSE-labeled CD25−CD4+ T cells as responder cells was evaluated. Proliferation of responder cells was evaluated by CFSE dilution after 3 days as shown in a representative histogram (left) and quantified (right). Data are pooled from 2 to 3 independent experiments with three to four mice (a), 1 experiment with four mice (b) or is a representative of 2 independent experiments (c) and shown as mean ± SEM; *p < 0.05, **p < 0.01, ***p < 0.001

To assess whether this increased functional Treg pool in CD11cΔLKB1 mice could also be associated with a beneficial effect on disease outcome, we challenged mice with house dust mite to induce allergic asthma (Fig. 5a), which is a Type 2 immunity-driven disease model in which Tregs can provide protection against allergic inflammation.27 CD11cWT mice were highly susceptible to induction of HDM-driven allergic asthma, as evidenced by increased cellular infiltrate in the bronchioalveolar lavage (BAL) (Fig. 5b), increased accumulation of eosinophils in BAL and lung (Fig. 5c–e), and strong antigen-specific production of the Type 2 cytokines IL-4, IL-5, IL-10 and IL-13 by immune cells in the lung-draining mediastinal LN (Fig. 5f). Remarkably, CD11cΔLKB1 mice were totally resistant to developing this allergic response (Fig. 5b–e), which corresponded with significantly increased frequencies of Tregs in lungs and medLNs both before and after HDM challenge (Fig. 5g, h). This shows that in vivo LKB1 signalling in DCs is crucial for limiting excessive Treg induction, which is correlated with susceptibility to allergic asthma as a model of an inflammatory disease.

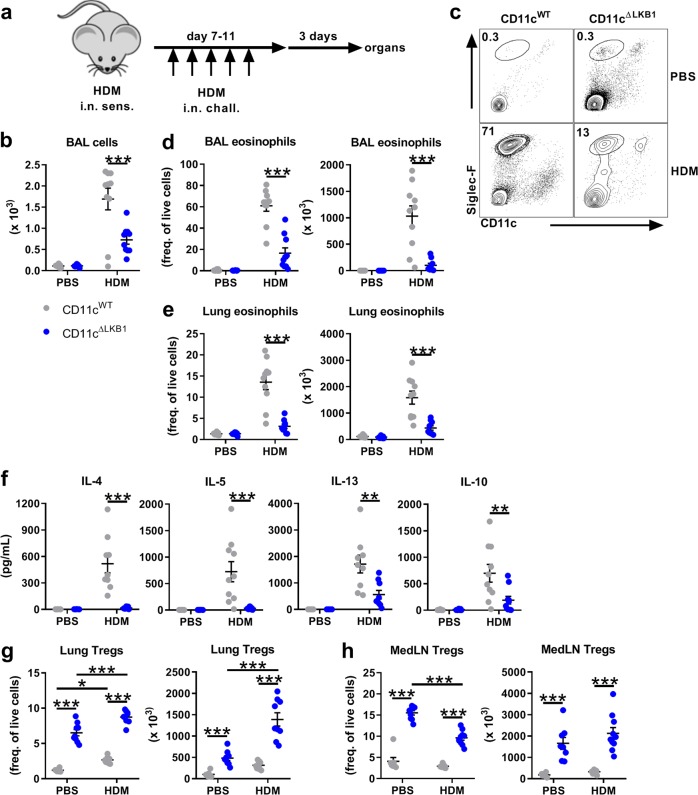

Fig. 5.

LKB1-deficiency in DCs protects mice from allergic asthma. a–f CD11cWT and CD11cΔLKB1 mice were sensitized by intranasal application of HDM and 1 week later challenged for 5 consecutive days. 3 days after the challenge, allergic airway inflammation was evaluated in bronchoalveolar lavage (BAL), lungs and lung-draining mediastinal LNs by flow cytometry. b Inflammatory cell recruitment was determined in BAL by cell counts. c–e Eosinophils were identified as Siglec-F+CD11c− as shown in representative flow cytometry plots from the BAL (c). BAL eosinophil percentages ((d), left) and absolute numbers ((d), right) and lung eosinophil percentages ((e), left) and absolute numbers ((e), right) were quantified. f Mediastinal LN cells were restimulated with HDM and 3 days later, supernatants were harvested and analysed for indicated cytokines by cytokine bead array. g, h Tregs identified as CD3+CD4+FOXP3+. Lung Tregs percentages ((g), left) and absolute numbers ((g), right) and MedLN Treg percentages ((h), left) and absolute numbers ((h), right) were quantified. Data are pooled from 2 independent experiments with three to five mice and shown as mean ± SEM; *p < 0.05, **p < 0.01, ***p < 0.001

LKB1 restricts the ability of thymic CD11b+ cDC2s to drive tTreg generation

Tregs can originate from the thymus (tTregs) as well as develop from naïve T cells in the periphery (pTregs). Under steady-state conditions, tTregs can be identified based on the expression of Helios.28,29 We observed that a higher frequency and number of Tregs from CD11cΔLKB1 mice expressed Helios than their counterparts in CD11cWT mice, suggesting that Tregs from CD11cΔLKB1 mice are of thymic origin (Fig. 6a). Consistent with this notion, we observed increased frequencies and numbers of Tregs in the thymus of adult CD11cΔLKB1 mice (Fig. 6b), despite a normal distribution of thymocyte subsets (Supplementary information, Fig. S8a), although it cannot be ruled out that pTregs circulating through the thymus could also potentially contribute to this phenotype.30 However, we found that at 6 days after birth, which is just after the start of tTreg development in mice,31 the frequencies and numbers of Tregs were higher in thymi of CD11cΔLKB1 mice (Fig. 6c), but not in spleens (Supplementary information, Fig. S8b). Together, these data provide support for the notion that the phenotype of accumulated Tregs in CD11cΔLKB1 mice is initiated in the thymus, concurrent with the beginning of natural tTreg development. Moreover, given the eTreg-like features of tTregs from CD11cΔLKB1 mice, and the highly proliferative nature of eTregs,23 we wondered whether in addition to increased tTreg output from thymus, enhanced peripheral proliferation of tTregs is occurring, which could contribute to the enlarged Treg pool in these mice. Indeed, in LNs from adult CD11cΔLKB1 mice, we found a significantly higher frequency of Ki67+ Tregs compared to WT mice (Supplementary information, Fig. S8c), although this was not clearly seen in spleens. In addition, we found that in in vitro cultures of peripheral tTregs with splenic DCs, Tregs proliferated faster when cocultured with cDC2s isolated from CD11cΔLKB1 mice than from WT counterparts (Supplementary information, Fig. S8d). Of note, cDC1s did not show a difference in this assay. These data indicate that, in addition to increased tTreg output from thymus, enhanced peripheral proliferation of tTregs may contribute to the observed tTreg accumulation in CD11cΔLKB1 mice.

Fig. 6.

LKB1 restricts the ability of thymic CD11b+ cDC2s to drive tTreg generation. a Intracellular Helios expression in Tregs identified as CD3+CD4+FOXP3+ from indicated peripheral organs of CD11cWT and CD11cΔLKB1 mice as shown in representative flow cytometry plots of splenic Tregs (left). Percentages (middle) and absolute numbers (right) were quantified by flow cytometry. b Percentages (left) and absolute numbers (right) of Tregs in thymi of CD11cWT and CD11cΔLKB1 mice were quantified. c Percentages (left) and absolute numbers (right) of Tregs in thymi of 6 days old CD11cWT and CD11cΔLKB1 pups were quantified. d Thymic cDC1s and cDC2s were identified as CD11c+MHCII+CD8a+ (or CD11c+MHCII+XCR1+) and CD11c+MHCII+11b+ (CD11c+MHCII+CD172a+) respectively (see Supplementary information, Figure S1a for gating strategy), and percentages (top) and absolute numbers (bottom) were quantified. e, f Flt3L-expanded thymic cDC1s, cDC2s and pDCs, the last identified as Siglec-H+CD11cint, were sorted and cocultured in the presence of IL-7 with GFP− CD25− single positive CD4+ thymocytes sorted from DEREG mice. After 5 days, frequencies of newly generated GFP+(FOXP3+) cells were determined as shown in representative flow cytometric plots of cocultures with thymic cDC2s ((f), left) and enumerated ((f), right). g Coculture as in (f) but with double amount of thymic cDC2s. Data are pooled from 3 (b, d), 2 (f, g) or 1 (a, c) (independent) experiment(s) with three to four mice and shown as mean ± SEM; *p < 0.05, **p < 0.01, ***p < 0.001

Next, we aimed to further understand how loss of LKB1 in DCs enhanced Treg output from the thymus. Three major DC subsets have been described to be present in the thymus: CD8a+ cDC1s, CD11b+ cDC2s and pDCs, all of which have, depending on the model studied, been implicated in tTreg development.32–35 We found that cDC2s, but not cDC1s or pDCs, were present in an approximately two-fold higher frequency in thymi of CD11cΔLKB1 compared to CD11cWT mice (Fig. 6d; Supplementary information, Fig. S9a), although due to reduced total cell number of thymi from CD11cΔLKB1 mice, total cDC2 numbers were not elevated (Fig. 6d; Supplementary information, Fig. S9b). The increased frequency of cDC2s in thymi CD11cΔLKB1 mice correlated with a higher surface expression of CCR7 selectively on these DCs (Supplementary information, Fig. S9c). Ki67 staining was similar between cDC2s from thymi of CD11cΔLKB1 and CD11cWT mice, indicating no differences in proliferative rates (Supplementary information, Fig. S9d). In addition, consistent with what was observed for splenic cDCs, thymic cDCs from CD11cΔLKB1 mice had reduced mitochondrial mass and membrane potential (Supplementary information, Fig. S9e).

tTregs have been shown to primarily develop from immature single positive (SP) CD4+ CD25− thymocytes.31 To identify which DC subset(s) may drive the enhanced tTreg generation, we used an ex vivo DC-thymocyte coculture model,35 in which we assessed the ability of different thymic DC subsets to induce expression of Foxp3+ in SP CD4+ CD25−GFP− thymocytes sorted from foxp3-GFP/DTR (DEREG-mice) (Supplementary information, Fig. S10a, d). Given the rarity of thymic DCs, in vivo flt3L-expanded thymic DC subsets were used for these experiments. Consistent with a previous report using this model,35 we found that cDC2s from CD11cWT mice tended to have a superior ability to induce Foxp3+ Tregs from Foxp3- thymocytes, over cDC1s and pDCs (Fig. 6e, f). Importantly, cDC2s isolated from CD11cΔLKB1 mice showed a further enhanced capacity to generate Foxp3+ Tregs from Foxp3- thymocytes (Fig. 6f). Concomitantly, some additional expansion of Foxp3- T cells could be observed (Supplementary information, Fig. S10b). The tTreg-generating ability of the other two DC subsets was unaffected by loss of LKB1 (Fig. 6f). Moreover, doubling the number cDC2s from CD11cΔLKB1 mice in these cultures, to mimic the increased frequency of cDC2s found in thymi of these mice, further boosted tTreg output (Fig. 6g). This would suggest that both cell-intrinsic differences and changes in frequency of cDC2s as a consequence of LKB1 deficiency could account for the increased tTreg generation. Of note, in analogous cocultures of splenic DCs with splenic naïve conventional CD25−GFP−CD4+ T cells (Supplementary information, Fig. S10c) or of OVA-peptide pulsed splenic DCs with naïve OVA-specific OT-II CD4+ T cells (data not shown), no differential induction of Foxp3+ Tregs could be observed. Together, these findings suggest that LKB1 signalling in DCs is critically important for selectively keeping tTreg generation in check, specifically by limiting the ability of thymic cDC2s to promote tTreg generation.

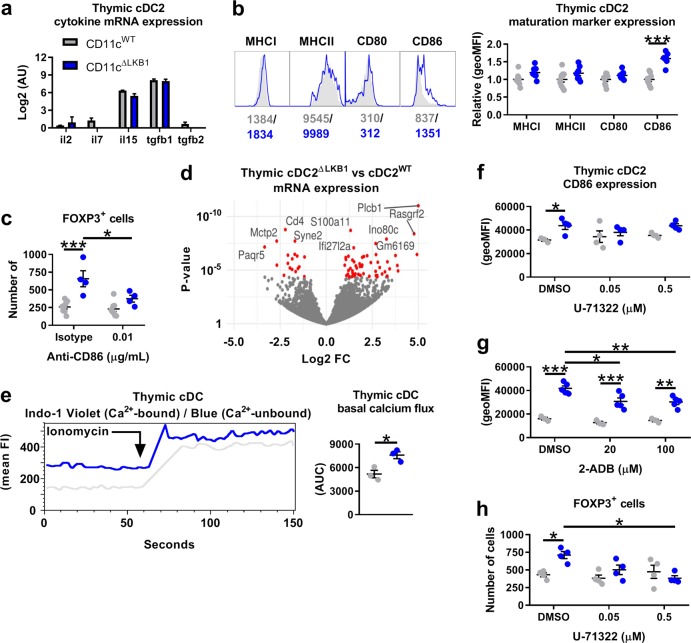

LKB1 signalling restricts tTreg generation by thymic cDC2 by limiting mTOR, calcium signalling and expression of CD86

Finally, we aimed to delineate the underlying immunological and molecular mechanism(s) through which LKB1 limits thymic cDC2s to promote generation of tTregs. We found either very low or no difference in mRNA expression of cytokines linked to fostering tTreg development,36–38 including IL-2, IL-7, IL-15 and TGFβ1/2, between thymic cDC2s from CD11cΔLKB1 and CD11cWT mice (Fig. 7a). However, we did find a selective increase in expression of CD86 on both Flt3L-expanded and un-expanded thymic cDC2s from CD11cΔLKB1 mice (Fig. 7b; Supplementary information, Fig. S11a). Increased expression of CD86 on thymic cDC2s from CD11cΔLKB1 mice was already evident at day 6 after birth (Supplementary information, Fig. S11b), which coincides with the initiation of the increased tTreg output from the thymus in these mice. The frequencies of these DCs were not yet increased on day 6 (Supplementary information, Fig. S11c). Costimulation provided by CD80 and CD86 is known to be crucial for tTreg development as tTreg generation in CD80/86 or CD28 KO mice is severely compromised.39,40 Importantly, addition of low doses of neutralizing anti-CD86 to cDC2-thymocyte cocultures as described in Fig. 6g — to reduce, but not entirely block CD86-mediated costimulation — selectively counteracted the enhanced tTreg-generating ability of LKB1-deficient cDC2s, back to levels similar to those induced by WT cDC2s (Fig. 7c), suggesting that the increased CD86 expression accounts for the observed phenotype.

Fig. 7.

LKB1 signalling restricts thymic cDC2-induced tTreg generation by limiting calcium signalling and expression of CD86. a RNAseq-based relative mRNA expression of indicated genes from sorted Flt3L-expanded LKB1-deficient thymic cDC2s vs. Flt3L-expanded WT thymic cDC2s. b Representative histograms (left) and relative surface expression (right) are shown of indicated markers by Flt3L-expanded thymic cDC2s. c Flt3L-expanded thymic cDC2s were sorted and cocultured with GFP-FOXP3−CD25− single positive CD4+ thymocytes sorted from DEREG mice in the presence of IL-7 with or without anti-CD86. After 5 days, newly generated GFP-FOXP3+ cells were enumerated. d Volcano plot shows genes differentially expressed between Flt3L-expanded LKB1-deficient thymic cDC2s vs. Flt3L-expanded WT thymic cDC2s. x axis shows log-fold change in expression between LKB1-deficient and WT thymic cDC2s. y axis shows p value for corresponding gene. Significantly differentially expressed genes are highlighted in red. e Calcium flux in CD11c-MACSed Flt3L-expanded thymic total cDCs from CD11cWT and CD11cΔLKB1 mice. The bridged gap indicates the addition of Ionomycin. Basal calcium flux = 30 s before addition of Ionomycin. f Thymic single cell suspensions from Flt3L-treated mice were treated with the phospholipase C (PLC) inhibitor U-71322 for 30 min, washed, and 18 h later, CD86 surface expression on cDC2s was determined by flow cytometry. g As in (f) but with the IP3R inhibitor 2-ADB instead of U-71322. h as in (c) but with 30 min pre-treatment with U-71322 instead of anti-CD86. Data are pooled from 3 independent experiments with three mice (b), 2 independent experiments with one to three mice (c, h) or 1 experiment with three to five mice (a, d, f, g) and shown as mean ± SEM; *p < 0.05, **p < 0.01, ***p < 0.001

The most well-characterized substrate through which LKB1 regulates cellular functions and metabolism is AMPK, which mediates its effects through its catalytic α−subunit.41 Of the two α−subunit isoforms that exist, myeloid cells express only AMPKα1.42 To assess whether LKB1 controls the tTreg-generating ability of thymic cDC2s through AMPK signalling, we crossed Prkaa1flox/flox mice (encoding AMPKα1) with Itgaxcre mice (CD11cΔAMPKα1). Thymic DCs from both CD11cΔLKB1 (Supplementary information, Fig. S11d) and CD11cΔAMPKα1 (Supplementary information, Fig. S11e) mice showed a comparable defect in AMPK signalling, which was measured by phosphorylation of the bona fide AMPK substrate ACCser79. Surprisingly, however, in contrast to what we found in CD11cΔLKB1 mice, Treg populations in both spleens and thymi from CD11cΔAMPKα1 mice were similar in size to that of CD11cWT mice (Supplementary information, Fig. S11f), demonstrating that the observed Treg phenotype in CD11cΔLKB1 mice is driven in an AMPK-independent manner. Of note, metabolic changes observed in DCs from CD11cΔLKB1 mice, were not seen in DCs from CD11cΔAMPKα1 mice, indicating that LKB1-induced metabolic properties in DCs are also mediated independently from AMPK (Supplementary information, Fig. S11g, h). In an attempt to identify how LKB1 regulates the tTreg-generating ability of thymic cDC2s independently from AMPK, the transcriptome of thymic cDC2s from CD11cΔLKB1 mice was analysed and compared to that of the other thymic DC subsets, as well as to those from CD11cWT mice. This revealed that loss of LKB1 had the largest impact on the transcriptome of cDC2s, in comparison to cDC1s and pDCs, resulting in total of 70 significantly differentially expressed genes between KO and WT cDC2s (Fig. 7d; Supplementary information, Fig. S12). The single most strongly upregulated gene (800 fold) in LKB1-deficient cDC2s was plcb1, which encodes phospholipase C β1 (PLC-β1) (Fig. 7d). PLC, by activation of inositol trisphosphate receptor (IP3R), promotes calcium release and signalling in cells, which has been shown to be crucial for DC activation, migration and T cell priming.43 Consistent with this increased expression of PLC-β1, we found elevated baseline calcium levels in thymic LKB1-deficient cDC2s (Fig. 7e). When we lowered PLC activity, using low doses of a PLC inhibitor, or inhibited IP3R in LKB1-deficient cDC2s, the increased CD86 expression was selectively reduced in LKB1-deficient cDC2s (Fig. 7f, g), which concordantly resulted in a reduction of their tTreg-generating ability to similar levels as thymic LKB1-sufficient cDC2s (Fig. 7h). In addition, gene set enrichment analysis for biological processes indicated increased translational activity in LKB1-deficient cDC2s (Supplementary information, Fig. S13a). The mammalian target of rapamycin (mTOR) signalling pathway is an important positive regulator of translation and its activation is antagonized by AMPK signalling.44 Consistent with impaired AMPK signalling and an increased translational signature, thymic DCs from CD11cΔLKB1 mice displayed heightened mTOR signalling as determined by phosphorylation of S6 (Supplementary information, Fig. S13b). Blocking of mTOR did not significantly reduce CD86 expression in LKB1-deficient cDC2s (Supplementary information, Fig. S13c). However, it did result in a significant reduction of their tTreg-generating ability, back to similar levels as LKB1-sufficient cDC2s (Supplementary information, Fig. S13d), suggesting a role for enhanced mTOR signalling in this phenotype independent from regulation of CD86. These observations indicate that LKB1, independently from AMPK, keeps tTreg generation in check by limiting mTOR signalling and calcium signalling-induced costimulation by thymic cDC2s.

Discussion

LKB1 is a central regulator of cellular metabolism and growth. Despite the growing appreciation for a key role of metabolic reprogramming in shaping the functional properties of DCs, the role of LKB1 in DC metabolism and biology has thus far not been explored. We here discovered a crucial role for LKB1 in governing mitochondrial fitness, and in putting a brake on DC activation, migration and T cell priming. Interestingly, we provide evidence that while loss of LKB1 results in enhanced immunogenicity of DCs in the periphery, this phenotype of enhanced maturation also licences CD11b+ DCs to increase thymic Treg development and expansion under homeostatic conditions. Our data suggest that this tTreg accumulation has a dominant immunosuppressive effect on any pro-inflammatory immune response induced in these mice as illustrated by a reduced capacity to control tumor growth and by protection against developing allergic asthma. This reveals that LKB1 serves as an important rheostat in DCs to maintain immune homeostasis by governing the balance between pro-inflammatory and regulatory T cell responses.

Although LKB1 has been shown to be required for haematopoietic stem cell and Treg survival and maintenance,14,15,17,18 we did not observe gross alterations in DC frequencies and numbers in CD11cΔLKB1 mice, suggesting LKB1 is dispensable for these processes in DCs. Possibly, the fact that DCs are shorter-lived,45 makes them less reliant on LKB1-dependent processes that support longevity. Metabolically, LKB1-deficiency resulted in reduction of mitochondrial fitness parameters in multiple DC subsets across several organs, which was accompanied by increased glycolytic rates. Since we previously found that DC activation depends on a switch to glycolytic metabolism and not on OXPHOS,7,8 LKB1 may contribute to maintaining DCs in a quiescent state by stimulating mitochondrial oxidative metabolism and reducing aerobic glycolysis. To what extent this is AMPK-dependent remains to be determined, but the fact that other studies have documented a more pro-inflammatory phenotype of DCs in which AMPK was silenced,7,42,46 would indicate at least a partial dependence on AMPK. However, CD11cΔAMPKa1 mice did not phenocopy the metabolic changes in DCs, nor enhanced Treg accumulation seen in CD11cΔLKB1 mice, clearly demonstrating additional AMPK-independent LKB1-driven effects on DC biology, as further discussed below.

Despite the increased immunogenic potential of LKB1-deficient DCs, CD11cΔLKB1 mice were protected against allergic asthma and were less capable of controlling tumor growth. Our data suggest that this is due to a dramatic expansion of Foxp3+ Tregs with an effector (eTreg) phenotype, characterized by high expression of immunosuppressive markers and enhanced suppressive function. The observations that 1) a higher frequency of Tregs express Helios in naïve CD11cΔLKB1 mice, 2) Tregs were found to present in higher frequencies in thymi but not yet in spleens of newborn mice, and 3) only thymic DCs, but not splenic DCs, from CD11cΔLKB1 mice showed enhanced capacity to promote Treg differentiation, provide strong support for the notion that the observed accumulation of Tregs stems from increased tTreg output and not from enhanced conversion of pTregs from naïve T cells in the periphery. Moreover, our data suggest that tTreg proliferation is additionally stimulated in the periphery, which may further contribute to the observed enhanced accumulation of Tregs in CD11cΔLKB1 mice. Finally, it should be noted that our experimental model cannot formally rule out that loss of LKB1 in CD11c+ cells other than DCs, such as macrophages, may play a role in the accumulated tTreg phenotype. However, this is unlikely as it has been shown that macrophages play no significant role in development of tTregs.47

Several studies have highlighted the importance of thymic DCs in contributing to tTreg development,32–35 presumably by presenting self-antigen to positively selected, immature CD4+ SP thymocytes in the medullar regions of the thymus.48 However, the precise mechanisms and the relative contributions of different DC subsets in regulating thymic tTreg development are not well understood. In line with others,35 we here identified thymic CD11b+ cDC2s, to have a superior ability to promote Treg expansion from CD4+ SP thymocytes ex vivo. Importantly, in keeping with the observation that LKB1 deficiency induced the largest number of transcriptional changes in thymic cDC2, loss of LKB1 further potentiated the capacity specifically of thymic CD11b+ cDC2s to promote tTreg generation. In these cultures, we used CD4+ SP CD25−GFP− thymocytes sorted from foxp3-GFP/DTR (DEREG-mice) with the aim to test de novo induction of tTregs by these DCs. However, DEREG-mice have been reported to have a small proportion of Foxp3+ cells that do not express GFP.49 We therefore cannot formally exclude the possibility that some of the tTregs arising from our ex vivo coculture experiments, originate from a few CD25− Foxp3+ tTreg precursors that may have been present in the sorted CD4+ SP CD25−GFP− thymocytes. Yet, given that Foxp3 expression by thymocytes in the absence of CD25 expression renders them highly apoptotic,50 it is unlikely that these cells are a major contributor to the CD25+GFP+Foxp3+ tTreg pool we evaluated as a readout in these cultures. Finally, it should be noted that, thymic cDC2s were expanded in vivo with Flt3L-secreting tumor before use in ex vivo culture systems. We currently do not know whether these DCs are functionally identical to those in unmanipulated mice. Therefore, additional studies, using genetic approaches that selectively target LKB1 in cDC2s in situ, are warranted to unequivocally demonstrate that tTreg expansion observed in CD11cΔLKB1 mice is mediated by cDC2s in vivo.

tTreg development is commonly thought to be favored by engagement of TCRs with relatively high affinity to self-antigens, somewhere between the affinity required for positive selection of conventional T cells and the affinity leading to negative selection.48 Our observation that Tregs from CD11cWT and CD11cΔLKB1 have similar TCR repertoires, makes it unlikely that enhanced tTreg generation in CD11cΔLKB1 mice is due to an altered repertoire of peptides presented by thymic cDC2s that favor Treg-promoting high affinity MHCII-peptide-TCR interactions. Instead, we found an increased expression of CD86 on cDC2s from CD11cΔLKB1 mice, which underpins the enhanced capacity of these cells to promote tTreg generation. CD86 and CD80-dependent costimulation has been shown to be a prerequisite for tTreg development and has been suggested to provide signals — independently from TCR stimulation — that facilitate Treg differentiation early during development rather than fostering Treg generation through promoting the proliferative expansion of Treg precursors.39,51–53 Our data extend these observations by revealing that costimulation is not only permissive for, but may also, when increased, result in potentiation of tTreg generation. Further studies will be required to gain insight into the mechanism through which CD86-mediated costimulation by LKB1-deficient cDC2s results in enhanced tTreg development. In addition, we found an increased frequency of cDC2s in the thymus, which when mimicked in the ex vivo DC-thymocyte cultures, further enhanced tTreg generation. Thymic cDC2s develop extrathymically and migrate to the thymus where they can locally proliferate.54 Although the role for CCR7 in migration of DCs to the thymus is not fully understood, the observation that thymic cDC2s from CD11cΔLKB1 mice expressed higher levels of CCR7, but did not show increased Ki67 staining, may suggest that the higher frequency of these cells in the thymus can be explained by enhanced migration. We hypothesize that this increased DC frequency in the thymus results in more frequent and/or higher-affinity TCR interactions,48 that together with increased CD86 expression, can further contribute to the enhanced tTreg generation in CD11cΔLKB1 mice. Taken together, our work suggests that both cell-intrinsic differences and changes in frequency of cDC2s as a consequence of LKB1 deficiency can account for the increased tTreg generation and output. This reveals a central role of LKB1 in tTreg homeostasis by specifically restricting the ability of thymic cDC2s to drive tTreg development.

Interestingly, we show that deficiency of AMPKα1 in DCs does not lead to enhanced Treg accumulation, arguing against a role for AMPK in restricting LKB1-driven tTreg generation. Instead we found that loss of LKB1 resulted in increased PLC-β1 expression and baseline calcium levels. In line with the well-described role for PLC-induced calcium signalling in DC activation and migration,43 pharmacological inhibition of PLC or IP3R, partially reverted increased CD86 expression as well as the enhanced ability of thymic LKB1-deficient cDC2s to support tTreg development. However, given the potential off target effects of inhibitors, additional studies using genetic approaches are warranted to further corroborate these results. Thus far, LKB1 signalling has not been implicated in regulation of calcium signalling. Additional studies will be needed to reveal the underlying pathway through which LKB1 controls PLC-β1 expression and calcium signalling. It is likely to involve one or more of the AMPK related-kinases, which are also substrates of LKB1 and are known to mediate several LKB1-driven cellular processes.55 In this respect, MAP/microtubule affinity-regulating kinases and salt-inducible kinases might be interesting candidates as they have been shown to mediate the AMPK-independent immunological changes driven by LKB1 in Tregs.18 In addition, loss of LKB1 in thymic cDC2s resulted in increased mTOR activation which was also required for the increased ability of these cells to support tTreg development. Whether or how there is crosstalk between mTOR and PLC-β1-mediated calcium signalling in thymic cDC2s to regulate tTreg development remains to be determined. Given that PLC-γ1 signalling can promote mTOR activation in tumor cells,56 it is tempting to speculate that mTOR is a downstream target of PLC-β1 signalling to control tTreg development by thymic cDC2s. Collectively, our findings, revealing a key role for LKB1 in the regulation of DC function that is independent from AMPK, are largely consistent with, and add to the growing body of literature documenting AMPK-independent functions for LKB1 in the biology of other immune cells such as haematopoietic stem cells,14,15 Tregs17,18 and macrophages.19

Taken together, our current work reveals a crucial role for LKB1 in preventing DCs from going into functional overdrive, which at peripheral sites, translates into limiting their capacity to mature, migrate and prime pro-inflammatory T cells responses, and in the thymus, into restricting generation of tTregs. The observations of an increased inflammatory phenotype of DCs and concomitant accumulation of Tregs in CD11cΔLKB1 mice, share similarities with what has been observed in mice with a DC-specific deletion of A20, a negative regulator of TLR signalling.57 However, those mice were highly susceptible to developing systemic auto-immunity due to the fact that, in contrast to our murine model, Tregs only started to accumulate later in life (>20 weeks of age). Nonetheless, it is conceivable that both their and our observations, although with different kinetics, represent a common phenomenon of a feedback regulatory loop between DCs and Tregs described by Nussenzweig et al.,58 in which immunological effects of decreased or increased DC numbers and/or activation are counterbalanced by the concomitant shrinkage or expansion of the Treg pool, respectively, in an attempt to maintain immune homeostasis. In conclusion, we discovered a central role for LKB1 in governing DC-driven immunity and tolerance, which provides novel mechanistic insights into how tolerance vs. immunity are controlled and identifies the LKB1 signalling axis as a potentially promising target for therapeutic interventions.

Materials and methods

Mice

Itgaxcre Stk11fl/fl (LKB1) (17591855; 12226664), Itgaxcre Prkaa1fl/fl (AMPKα1) (21124450), Foxp3-DTR/EGFP (DEREG) (17200412), OVA-specific CD4+ T cell receptor transgenic mice (OT-II), or OVA-specific CD8+ T cell receptor transgenic mice (OT-I), and WT male and female mice, all on a C57BL/6 background, were purchased from The Jackson Laboratory and crossed, housed and bred at the LUMC, Leiden, The Netherlands, under SPF conditions. Animal experiments were performed when the mice were between 2–6 days or 8–16 weeks old, all in accordance with local government regulations and the EU Directive 2010/63EU and Recommendation 2007/526/EC regarding the protection of animals used for experimental and other scientific purposes, as well as approved by the Dutch Central Authority for Scientific Procedures on Animals (CCD) (animal license number AVD116002015253).

Flt3L-secreting B16 melanoma cells

Flt3L-secreting B16 melanoma cells were kindly provided by Dr. Edward Pearce and passaged every 3–4 days using a Trypsin-EDTA solution (Sigma, Zwijndrecht, The Netherlands) followed by replating in T175 culture flasks at 2 × 106 cells in 35 mL of medium comprised of DMEM High Glucose (Biowest, Nuaillé, France) supplemented with 10% FCS (Capricorn, Den Haag, The Netherlands), 100 U/mL penicillin (Eureco-pharma, Ridderkerk, The Netherlands) and 100 µg/mL streptomycin (Sigma).

Generation of BM-derived DCs

BM cells were flushed from femurs and plated in 6-well plate at 2 × 106 cells in 3–6 mL of medium comprised of RMPI-1640 (Gibco, Bleiswijk, The Netherlands) supplemented with 5% FCS (Gibco), 25 nM β-mercaptoethanol (Sigma), 100 U/mL penicillin (Eureco-pharma), 100 µg/mL streptomycin (Sigma) and 20 ng/mL of GM-CSF (PeproTech, Hamburg, Germany) for 8 days, with a medium change on day 4 and day 7. Subsequently, non-adherent GMDCs were used for various assays.

In vivo DC expansion, isolation and sorting

To expand the number of DCs in mice, Flt3L-secreting B16 melanoma cells were harvested and washed using phenol red-free HBSS (Gibco) before subcutaneous injection of 2 × 106 cells in 100 µL of HBSS into the flank of mice. Nine to twelve days later, lymphoid organs were harvested, placed in 500 µL medium (with Ca2+), mechanically disrupted, digested by addition of 50 µL medium (with Ca2+) supplemented with Collagenase D (Roche, Woerden, The Netherlands, end concentration of 1 mg/mL) and DNase I (Sigma, end concentration of 2000 U/mL) and incubation for 20 min at 37 °C. Upon completion of digestion, single-cell suspensions were subjected to red blood cell lysis (inhouse; 0.15 M NH4Cl, 1 mM KHCO3, 0.1 mM EDTA [Sigma] in ddH2O) and filtered with a 100 µm sterile filter before counting. From these suspensions, DC populations were further enriched by positive isolation with CD11c-Microbeads (Miltenyi, Leiden, The Netherlands) and sorting in cDC1 (CD8a+CD11c+MHCII+), cDC2 (CD11b+CD11c+MHCII+) and pDC (Siglec-H+CD11cint) subsets on a BD FACSAria using a 85 μm nozzle at 45 PSI. Subsequently, sorted DCs were used for various assays.

Western blotting

Sorted Flt3L-expanded splenic cDCs were washed twice with PBS before being lysed in EBSB buffer (8% [w/v] glycerol, 3% [w/v] SDS and 100 mM Tris-HCl [pH 6.8]). Lysates were immediately boiled for 5 min and their protein content was determined using a bicinchoninic acid protein assay kit (Pierce). Proteins were separated by SDS-PAGE followed by transfer to a PVDF membrane. Membranes were blocked for 1 h at room temperature in TTBS buffer (20 mM Tris-HCl [pH 7.6], 137 mM NaCl, and 0.25% [v/v] Tween 20) containing 5% (w/v) fat free milk and incubated overnight with primary antibodies. The primary antibodies used were: anti-LKB1 (Ley 37D/G6) (1:1000) (Santa Cruz) and anti-beta-actin (AC-15) (1:2000) (Sigma). The membranes were then washed in TTBS buffer and incubated with horseradish peroxidase-conjugated secondary antibodies for 2 h at room temperature. After washing, blots were developed using enhanced chemiluminescence.

DC cytokine analysis

For cytokine production, 3 × 105 expanded DCs in 200 µL of medium were settled in a flat-bottom 96-well plate and stimulated with Poly(I:C) (InvivoGen, Toulouse, France) or LPS (ultrapure, InvivoGen). Sixteen hours later, supernatants were collected for cytokine analysis by cytokine bead array.

DC migration assay

For DC migration assays, GMDCs were harvested on day 8, labelled with CTV according to the manufacture’s recommendation (1 µM, Invitrogen, Bleiswijk, The Netherlands), and washed using phenol red-free HBSS (Gibco) before subcutaneous injection of 5 × 105 cells in 40 µL of HBSS into the footpad of mice. Twenty-four hours later, the number of migrated CTV-labeled GMDCs was assessed in the draining popliteal lymph nodes (popLNs)

In vitro T cell priming assay

OT-II cells were negatively isolated with a CD4+ T cell Isolation Kit (Miltenyi) and OT-I cells were positively isolated with anti-mouse CD8a-PE (eBioscience, Bleiswijk, The Netherlands) followed by anti-PE MicroBeads (Miltenyi). 5 × 103 DCs were settled in a round-bottom 96-well plate, pulsed with 100 µg/mL of OVA (InvivoGen) in combination with LPS for 5 h, and washed before adding 5 × 104 CFSE-labeled OT cells in 200 µL of medium. After 3 days for the OT-I cells and 4 days for the OT-II cells, cells were harvested and analyzed for proliferation by assessing CFSE dilution and for cytokine production by intracellular cytokine analysis by flow cytometry which was done by incubating the cells in PMA/Ionomycin (Sigma) in the presence of Brefeldin A (Sigma) for 4 h before viability staining and fixation.

In vivo T cell priming following footpad immunization

In vitro-cultured GMDCs were pulsed with 100 µg/mL OVA (InvivoGen) and 100 ng/mL LPS (ultrapure, InvivoGen) for 6 h, after which cells were washed and used for subcutaneous immunization in the hind footpads of mice (5 × 105 DCs/footpad). Alternatively, mice were subcutaneously immunized with OVA and Poly (I:C) emulsified in 30 µL of incomplete Freunds’ adjuvant (IFA, InvivoGen) in the hind footpad. Seven days later, draining popliteal LNs were harvested and OVA-specific CD8+ T cell response was determined by flow cytometry. CD4+ and CD8+ T cell cytokine production was determined by flow cytometry after incubating the cells in PMA/Ionomycin (Sigma) in the presence of Brefeldin A (Sigma) for 4 h before viability staining and fixation.

In vitro T cell suppression assay

T cell suppression assays were performed in round-bottom 96-well plates with 2 × 104 sorted splenic CD4+CD25− T cells labelled with CFSE according to the manufacturer’s recommendations (0.5 µM, Sigma) as responder cells, activated by 5 µg/mL of anti-CD3 (BD Pharmingen, Vianen, The Netherlands), and cultured in the presence of 8 × 104 irradiated (3000 RAD) splenocytes, acting as antigen-presenting cells. 5 × 103 CD4+CD25+ T cells as suppressors sorted from CD11cWT or CD11cΔLKB1 mice were added and then cultured for 3 days after which CFSE dilution was assessed by flow cytometry.

In vitro Treg proliferation assay

5 × 104 CD4+CD8-GFP+CD25+ splenocytes, sorted from DEREG mice and labelled with CTV according to the manufacturer’s recommendations, were cultured in round-bottom 96-well plates together with 25 × 103 Flt3L-expanded splenic DC subsets sorted from CD11cWT or CD11cΔLKB1 mice, in the presence of 100 U/mL of recombinant human IL-2 (R&D systems). 4 days later, CTV dilution was assessed by flow cytometry.

In vitro Treg induction assay

In vitro Treg induction assays were performed in round-bottom 96-well plates with 1 × 104 sorted Flt3L-expanded thymic or splenic DC subsets and 2 × 104 sorted CD4+CD8-GFP−CD25− thymocytes or splenocytes from DEREG mice, unless different ratios are specifically mentioned, in the presence of 10 ng/mL of IL-7 (PeproTech) for 5 days. To determine the contribution of CD86 on DCs, anti-CD86 (BioLegend, Koblenz, Germany) or its isotype control (BioLegend) were added during the entire culture. To determine the contribution of phospholipase C, calcium or mTOR signalling in DCs, the DCs were incubated for 30 min with the phospholipase C inhibitor U 71322 (Abcam, Cambridge, The Netherlands), inositol trisphosphate receptor (IP3R) inhibitor 2-aminoethyl diphenylborinate (2-ADB, Sigma) or rapamycin (Calbiochem), respectively, and washed before adding the thymocytes in the presence of 150 ng/mL Flt3L (eBioscience). On day 5, the number of GFP+ Tregs in the culture was assessed by flow cytometry. For ex vivo assessment of the effect of these inhibitors on CD86 expression in thymic cDC2s, 1 × 106 thymocyte single-cell suspensions were incubated for 30 min with U-71322, 2-ADB or rapamycin and washed before culture in the presence of 150 ng/mL Flt3L. 18 h later, CD86 expression on thymic cDC2s was assessed by flow cytometry.

House dust mite-induced allergic asthma model

Allergic airway inflammation was induced by sensitizing mice via intranasal administration of 1 µg HDM (Greer, London, United Kingdom) in 50 µL of PBS. One week later, these mice were challenged for 5 consecutive days via intranasal administration of 10 µg HDM in 50 µL of PBS. On day 15, bronchoalveolar lavage (BAL) fluid, lung, and lung-draining mediastinal LNs (med LNs) were obtained to determine inflammatory cell recruitment. BAL was performed by instilling the lungs with 3 × 1 mL aliquots of sterile PBS (Braun, Oss, The Netherlands). For single-cell suspensions of whole lung tissue, lungs were perfused with sterile PBS via the right ventricle to clear leukocytes and erythrocytes from the pulmonary circulation. Lung and medLN homogenization was performed as described above. Eosinophilia was assessed in BAL and lungs by flow cytometry as a readout for allergic inflammation. To assess HDM-specific T cell responses, single cell suspensions of 3 × 105 isolated leukocytes of medLNs were added to a round-bottom 96-well plate with 10 µL HDM in 200 µL of medium. Plates were incubated at 37 °C in 5% CO2 for 3 days after which supernatants were analysed for cytokines by cytokine bead array.

Melanoma tumor model

Mice were challenged with 1 × 105 OVA-expressing B16 melanoma cells intradermally on the flank. Nine to twelve days later, mice were sacrificed and tumor weight was determined.

Flow cytometry

Enzymatically digested cell suspensions were stained for 20 min at room temperature using a Fixable Aqua Dead Cell Stain Kit (Invitrogen) and unless sorted or calcium flux assessed, fixed for 10 min at 37 °C using a 4% methanol-free formaldehyde solution (Polysciences, Edenkoben, Germany for pACC Ser79 detection) or 1 h at 4 °C using a FOXP3/Transcription Factor Staining Buffer Set (Invitrogen, for FOXP3 detection) or 15 min at room temperature using a 1.85% formaldehyde PBS solution (Sigma, for everything else). For detection of pACC Ser79, cell suspensions were permanently permeabilised using 100% methanol for at least 10 min at −20 °C (pACC Ser79 detection). Afterwards, cell suspensions were stained in PBS supplemented with 0.5% BSA (Roche) and 2 mM EDTA (Sigma) and antibodies for 30 min at 4 °C. For detection of FOXP3 and intracellular cytokines, cell suspensions were stained in Permeabilization Buffer (eBioscience) instead of supplemented PBS. Mitochondrial mass, membrane potential and ROS were quantified by staining with MitoTracker Green (20 nM, Invitrogen), TMRM (20 nM, Invitrogen) and MitoSOX (5 uM, Invitrogen) for 30 min at 37 °C before staining with other antibodies. Phosphorylated ACC Ser79 and S6 Ser235/236 were stained for 1 h at room temperature before staining with other antibodies. The second round of staining included goat anti-rabbit-AF647 to detect the unconjugated rabbit anti-pACC Ser79. All samples were run on a FACSCanto II or BD LSR II and analysed using FACS Diva 8 (all BD Biosciences) and FlowJo (Version 9.5, TreeStar).

Antibodies

The antibodies used in this study were as follows: anti-CD3-eF450, anti-CD4-PE-Cy7, anti-CD11b-PE-Cy7, anti-CD11c-PE-Cy7, anti-CD40, anti-CD44, anti-CD62L, anti-CD80, anti-CD152 (CTLA-4), anti-FOXP3, anti-IFN-γ-FITC and IFN-γ-PE-Cy7, anti-IL-17A and anti-MHCII all from eBioscience. Anti-CD3-BV605, anti-CD8a, anti-CD64, anti-CD86-APC-Fire 750, anti-CD103, anti-CD172a, anti-CD197 (CCR7), anti-CD326 (EpCAM), anti-Helios, anti-Ki67, anti-LAP (TGF-β1), anti-H2-Kb (MHCI) and anti-XCR1 all from BioLegend. Anti-CD4-BV650, anti-CD11c-HV450, anti-CD25, anti-CD86-PE, anti-IFN-γ-APC-Cy7, anti-IL-4, anti-Siglec-F and anti-pS6 Ser235/236 all from BD Biosciences (Vianen, The Netherlands). Anti-CD11b-PerCP-Cy5.5 from BD Pharmingen. Anti-pACC Ser79 from Cell Signaling (Leiden, The Netherlands). Anti-rabbit from Invitrogen. H-2Kb/OVA (SIINFEKL) MHC Tetramer made inhouse.

Cytometric bead array

Cell culture supernatants were analyzed for IL-1b, IL-4, IL-5, IL-6, IL-10, IL-13 and TNF using the Cytokine Bead Array (BD Biosciences) according to the manufacturer’s recommendation.

RNA and TCR sequencing

mRNA from 0.5 to 1 × 105 sorted thymic DC subsets or splenic and thymic CD8-CD4+CD25hi Tregs was extracted with oligo-dT beads (Invitrogen), and libraries were prepared and quantified as described before.59 Raw and processed data were deposited to Gene Expression Omnibus. Differential gene expression analysis was carried out with DESeq2 package,60 pre-ranked gene set enrichment analysis was done using fgsea package61 with Reactome database,62 MSigDB Hallmarks collection63 and Gene Ontology database (The Gene Ontology Consortium, 2017). T cell receptor alpha and beta chain clonality was assessed using the MiXCR tool64 using standard parameters of the RNA-seq workflow. TCR clonality was analyzed using the R package tcR.65

Extracellular flux analysis

Extracellular Flux Analysis was performed as described before.66 Briefly, DCs were resuspended in unbuffered RPMI-1640 (Sigma), which was filtered through a 0.22 µm filter system (Corning, Amsterdam, The Netherlands), the pH was set to 7.4 using 37% HCl, and was supplemented with 5% FCS. Cells were settled (70.000 GMDCs or 175.000 cDCs) on a 96-well assay plate (Agilent, Amstelveen, The Netherlands) and rested at 37 °C in 0% CO2 for 1 h. OCR and ECAR were recorded with the XF96e Extracellular Flux analyser (Agilent) and analysed using Wave Desktop (Version 2.6, Agilent). Subsequently extracellular acidification rate (ECAR) and oxygen consumption rate (OCR) were analyzed in response to glucose (10 mM; port A; Sigma), oligomycin (1 µM; port B; Cayman Chemical, Ann Arbor, Michigan, United States), fluoro-carbonyl cyanide phenylhydrazone (FCCP, 3 µM; port C; Sigma), and rotenone/antimycin A (1/1 μM; port D; Sigma). Glycolytic rate = increase in ECAR in response to injection A. Baseline OCR = difference in OCR between readings following port A injection and readings after port D injection. Spare OCR is difference between basal and maximum OCR, which is calculated based on the difference in OCR between readings following port C injection and readings after port A injection.

Calcium flux assay

To assess intracellular calcium flux in DCs, MACS-isolated CD11c-positive cells from the thymus were washed with PBS (with Ca2+/Mg2+) supplemented with 1% FCS. 2 uM of Indo-1 AM (Invitrogen) was added to 500 µL of PBS 1% FCS (with Ca2+/Mg2+) for up to 2 × 106 cells. Cells were incubated for 45 min at 37 °C in the dark and then washed with cold PBS (with Ca2+/Mg2+) and resuspended in 500 µL cold PBS (with Ca2+/Mg2+). The cells were reheated for 5 min to 37 °C before assessing calcium flux. Calcium flux was then assessed by flow cytometry analysing Indo-1 ratio over a time course of 30 s basal measurement and 30 s following Ionoymcin (Sigma) stimulation.

Quantification and statistical analysis

Statistical analysis, as specified in figure legends, were performed with Prism 7 (GraphPad software). Data were analysed with the non-paired Student’s t test for 2 bars or the two-way ANOVA corrected for multiple comparisons using Sidak’s multiple comparison test for 2 or more groups. p values < 0.05 were considered significant (*p < 0.05, **p < 0.01, ***p < 0.001).

Supplementary information

Acknowledgements

This work was supported by an LUMC and Marie Curie fellowship awarded to B.E.

Author contributions

B.E., L.R.P., T.A.P., A.J.v.d.H., F.O., H.v.d.Z., S.v.d.S., A.S., A.O.-F. and E.E. performed experiments; B.E., M.N.A., L.R.P., A.S. and E.E. designed and analyzed experiments; B.E. conceived and supervised the study and wrote the manuscript together with L.R.P.

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Supplementary information

Supplementary information accompanies this paper at 10.1038/s41422-019-0161-8.

References

- 1.Abbas AK, et al. Regulatory T cells: recommendations to simplify the nomenclature. Nat. Immunol. 2013;14:307–308. doi: 10.1038/ni.2554. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Josefowicz SZ, Lu LF, Rudensky AY. Regulatory T cells: mechanisms of differentiation and function. Annu. Rev. Immunol. 2012;30:531–564. doi: 10.1146/annurev.immunol.25.022106.141623. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Bilate AM, Lafaille JJ. Induced CD4+Foxp3+ regulatory T cells in immune tolerance. Annu. Rev. Immunol. 2012;30:733–758. doi: 10.1146/annurev-immunol-020711-075043. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Domogalla MP, Rostan PV, Raker VK, Steinbrink K. Tolerance through education: how tolerogenic dendritic cells shape immunity. Front. Immunol. 2017;8:1764. doi: 10.3389/fimmu.2017.01764. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Buck MD, Sowell RT, Kaech SM, Pearce EL. Metabolic instruction of immunity. Cell. 2017;169:570–586. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2017.04.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Pearce EJ, Everts B. Dendritic cell metabolism. Nat. Rev. Immunol. 2015;15:18–29. doi: 10.1038/nri3771. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Krawczyk CM, et al. Toll-like receptor-induced changes in glycolytic metabolism regulate dendritic cell activation. Blood. 2010;115:4742–4749. doi: 10.1182/blood-2009-10-249540. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Everts B, et al. TLR-driven early glycolytic reprogramming via the kinases TBK1-IKKvarepsilon supports the anabolic demands of dendritic cell activation. Nat. Immunol. 2014;15:323–332. doi: 10.1038/ni.2833. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Malinarich F, et al. High mitochondrial respiration and glycolytic capacity represent a metabolic phenotype of human tolerogenic dendritic cells. J. Immunol. 2015;194:5174–5186. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.1303316. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Ferreira Gabriela Bomfim, Vanherwegen An-Sofie, Eelen Guy, Gutiérrez Ana Carolina Fierro, Van Lommel Leentje, Marchal Kathleen, Verlinden Lieve, Verstuyf Annemieke, Nogueira Tatiane, Georgiadou Maria, Schuit Frans, Eizirik Décio L., Gysemans Conny, Carmeliet Peter, Overbergh Lut, Mathieu Chantal. Vitamin D3 Induces Tolerance in Human Dendritic Cells by Activation of Intracellular Metabolic Pathways. Cell Reports. 2015;10(5):711–725. doi: 10.1016/j.celrep.2015.01.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Lin SC, Hardie DG. AMPK: Sensing glucose as well as cellular energy status. Cell. Metab. 2018;27:299–313. doi: 10.1016/j.cmet.2017.10.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Hemminki A, et al. A serine/threonine kinase gene defective in Peutz-Jeghers syndrome. Nature. 1998;391:184–187. doi: 10.1038/34432. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Shorning BY, Clarke AR. Energy sensing and cancer: LKB1 function and lessons learnt from Peutz-Jeghers syndrome. Semin. Cell. Dev. Biol. 2016;52:21–29. doi: 10.1016/j.semcdb.2016.02.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Nakada D, Saunders TL, Morrison SJ. Lkb1 regulates cell cycle and energy metabolism in haematopoietic stem cells. Nature. 2010;468:653–658. doi: 10.1038/nature09571. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Gurumurthy S, et al. The Lkb1 metabolic sensor maintains haematopoietic stem cell survival. Nature. 2010;468:659–663. doi: 10.1038/nature09572. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Cao Y, et al. LKB1 regulates TCR-mediated PLCgamma1 activation and thymocyte positive selection. EMBO J. 2011;30:2083–2093. doi: 10.1038/emboj.2011.116. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Yang K, et al. Homeostatic control of metabolic and functional fitness of Treg cells by LKB1 signalling. Nature. 2017;548:602–606. doi: 10.1038/nature23665. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.He N, et al. Metabolic control of regulatory T cell (Treg) survival and function by Lkb1. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA. 2017;114:12542–12547. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1715363114. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Liu Z, et al. Liver kinase B1 suppresses lipopolysaccharide-induced nuclear factor kappaB (NF-kappaB) activation in macrophages. J. Biol. Chem. 2015;290:2312–2320. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M114.616441. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Du X, et al. Hippo/Mst signalling couples metabolic state and immune function of CD8alpha(+) dendritic cells. Nature. 2018;558:141–145. doi: 10.1038/s41586-018-0177-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Kratchmarov R, et al. Metabolic control of cell fate bifurcations in a hematopoietic progenitor population. Immunol. Cell Biol. 2018;96:863–871. doi: 10.1111/imcb.12040. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Goldszmid RS, et al. Dendritic cells charged with apoptotic tumor cells induce long-lived protective CD4+ and CD8+ T cell immunity against B16 melanoma. J. Immunol. 2003;171:5940–5947. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.171.11.5940. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Smigiel KS, et al. CCR7 provides localized access to IL-2 and defines homeostatically distinct regulatory T cell subsets. J. Exp. Med. 2014;211:121–136. doi: 10.1084/jem.20131142. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Thornton AM, Shevach EM. Suppressor effector function of CD4+CD25+ immunoregulatory T cells is antigen nonspecific. J. Immunol. 2000;164:183–190. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.164.1.183. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Karim M, Feng G, Wood KJ, Bushell AR. CD25+CD4+ regulatory T cells generated by exposure to a model protein antigen prevent allograft rejection: antigen-specific reactivation in vivo is critical for bystander regulation. Blood. 2005;105:4871–4877. doi: 10.1182/blood-2004-10-3888. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Sakaguchi S, Wing K, Onishi Y, Prieto-Martin P, Yamaguchi T. Regulatory T cells: how do they suppress immune responses? Int. Immunol. 2009;21:1105–1111. doi: 10.1093/intimm/dxp095. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Kearley J, Robinson DS, Lloyd CM. CD4+CD25+ regulatory T cells reverse established allergic airway inflammation and prevent airway remodeling. J. Allergy Clin. Immunol. 2008;122:617–624 e616. doi: 10.1016/j.jaci.2008.05.048. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Thornton AM, et al. Expression of Helios, an Ikaros transcription factor family member, differentiates thymic-derived from peripherally induced Foxp3+ T regulatory cells. J. Immunol. 2010;184:3433–3441. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.0904028. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Zabransky DJ, et al. Phenotypic and functional properties of Helios+ regulatory T cells. PLoS ONE. 2012;7:e34547. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0034547. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Thiault N, et al. Peripheral regulatory T lymphocytes recirculating to the thymus suppress the development of their precursors. Nat. Immunol. 2015;16:628–634. doi: 10.1038/ni.3150. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Fontenot JD, Dooley JL, Farr AG, Rudensky AY. Developmental regulation of Foxp3 expression during ontogeny. J. Exp. Med. 2005;202:901–906. doi: 10.1084/jem.20050784. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Hu Z, et al. CCR7 modulates the generation of thymic regulatory T cells by altering the composition of the thymic dendritic cell compartment. Cell Rep. 2017;21:168–180. doi: 10.1016/j.celrep.2017.09.016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Perry JSA, et al. Distinct contributions of Aire and antigen-presenting-cell subsets to the generation of self-tolerance in the thymus. Immunity. 2014;41:414–426. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2014.08.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Martin-Gayo E, Sierra-Filardi E, Corbi AL, Toribio ML. Plasmacytoid dendritic cells resident in human thymus drive natural Treg cell development. Blood. 2010;115:5366–5375. doi: 10.1182/blood-2009-10-248260. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Proietto AI, et al. Dendritic cells in the thymus contribute to T-regulatory cell induction. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA. 2008;105:19869–19874. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0810268105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Weist BM, Kurd N, Boussier J, Chan SW, Robey EA. Thymic regulatory T cell niche size is dictated by limiting IL-2 from antigen-bearing dendritic cells and feedback competition. Nat. Immunol. 2015;16:635–641. doi: 10.1038/ni.3171. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Vang KB, et al. IL-2, -7, and -15, but not thymic stromal lymphopoeitin, redundantly govern CD4+Foxp3+ regulatory T cell development. J. Immunol. 2008;181:3285–3290. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.181.5.3285. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Konkel JE, Jin W, Abbatiello B, Grainger JR, Chen W. Thymocyte apoptosis drives the intrathymic generation of regulatory T cells. Proc. . Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 2014;111:E465–E473. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1320319111. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Hinterberger M, Wirnsberger G, Klein L. B7/CD28 in central tolerance: costimulation promotes maturation of regulatory T cell precursors and prevents their clonal deletion. Front. Immunol. 2011;2:30. doi: 10.3389/fimmu.2011.00030. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Salomon B, et al. B7/CD28 costimulation is essential for the homeostasis of the CD4+CD25+ immunoregulatory T cells that control autoimmune diabetes. Immunity. 2000;12:431–440. doi: 10.1016/S1074-7613(00)80195-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Ross FA, MacKintosh C, Hardie DG. AMP-activated protein kinase: a cellular energy sensor that comes in 12 flavours. Febs. J. 2016;283:2987–3001. doi: 10.1111/febs.13698. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Nieves W, et al. Myeloid-restricted AMPKalpha1 promotes host immunity and protects against IL-12/23p40-dependent lung injury during hookworm infection. J. Immunol. 2016;196:4632–4640. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.1502218. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Shumilina E, Huber SM, Lang F. Ca2+ signaling in the regulation of dendritic cell functions. Am. J. Physiol. Cell. Physiol. 2011;300:C1205–C1214. doi: 10.1152/ajpcell.00039.2011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Weichhart T, Hengstschlager M, Linke M. Regulation of innate immune cell function by mTOR. Nat. Rev. Immunol. 2015;15:599–614. doi: 10.1038/nri3901. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Chen M, Huang L, Shabier Z, Wang J. Regulation of the lifespan in dendritic cell subsets. Mol. Immunol. 2007;44:2558–2565. doi: 10.1016/j.molimm.2006.12.020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Carroll, K. C., Viollet, B. & Suttles, J. AMPKalpha1 deficiency amplifies proinflammatory myeloid APC activity and CD40 signaling. J. Leukoc. Biol. 94, 1113-11121(2013). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 47.Guerri L, et al. Analysis of APC types involved in CD4 tolerance and regulatory T cell generation using reaggregated thymic organ cultures. J. Immunol. 2013;190:2102–2110. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.1202883. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Hsieh CS, Lee HM, Lio CW. Selection of regulatory T cells in the thymus. Nat. Rev. Immunol. 2012;12:157–167. doi: 10.1038/nri3155. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Schallenberg S, Petzold C, Tsai PY, Sparwasser T, Kretschmer K. Vagaries of fluorochrome reporter gene expression in Foxp3+ regulatory T cells. PLoS ONE. 2012;7:e41971. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0041971. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Tai X, et al. Foxp3 transcription factor is proapoptotic and lethal to developing regulatory T cells unless counterbalanced by cytokine survival signals. Immunity. 2013;38:1116–1128. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2013.02.022. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Tai X, Cowan M, Feigenbaum L, Singer A. CD28 costimulation of developing thymocytes induces Foxp3 expression and regulatory T cell differentiation independently of interleukin 2. Nat. Immunol. 2005;6:152–162. doi: 10.1038/ni1160. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Williams JA, et al. Thymic medullary epithelium and thymocyte self-tolerance require cooperation between CD28-CD80/86 and CD40-CD40L costimulatory pathways. J. Immunol. 2014;192:630–640. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.1302550. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Lio CW, Dodson LF, Deppong CM, Hsieh CS, Green JM. CD28 facilitates the generation of Foxp3(-) cytokine responsive regulatory T cell precursors. J. Immunol. 2010;184:6007–6013. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.1000019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Li J, Park J, Foss D, Goldschneider I. Thymus-homing peripheral dendritic cells constitute two of the three major subsets of dendritic cells in the steady-state thymus. J. Exp. Med. 2009;206:607–622. doi: 10.1084/jem.20082232. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Lizcano JM, et al. LKB1 is a master kinase that activates 13 kinases of the AMPK subfamily, including MARK/PAR-1. EMBO J. 2004;23:833–843. doi: 10.1038/sj.emboj.7600110. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Dai L, et al. Phosphoinositide-specific phospholipase Cgamma1 inhibition induces autophagy in human colon cancer and hepatocellular carcinoma cells. Sci. Rep. 2017;7:13912. doi: 10.1038/s41598-017-13334-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Kool M, et al. The ubiquitin-editing protein A20 prevents dendritic cell activation, recognition of apoptotic cells, and systemic autoimmunity. Immunity. 2011;35:82–96. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2011.05.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Liu K, et al. In vivo analysis of dendritic cell development and homeostasis. Science. 2009;324:392–397. doi: 10.1126/science.1171243. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Vincent EE, et al. Mitochondrial phosphoenolpyruvate carboxykinase regulates metabolic adaptation and enables glucose-independent tumor growth. Mol. Cell. 2015;60:195–207. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2015.08.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]