Dear Editor,

The mixed-lineage leukemia (MLL) protein was originally identified through its association with acute lymphoid and myeloid leukemias1. MLL is an H3K4 histone methyltransferase that can execute methylation through its evolutionarily conserved SET domain, and this activity is essential for normal MLL function2. MLL is proteolytically cleaved into two fragments: MLLN320 and MLLC180, which non-covalently interact to form an intramolecular complex3.

MLL is regarded as a nuclear protein and several nuclear localization signals in MLLN320 contribute to its nuclear localization;4 therefore, nuclear extracts are routinely used to purify MLL protein complexes2,5. Through this strategy, a number of nuclear proteins such as MENIN, ASH2L, and WDR5 have been identified as essential MLL-binding partners5,6. However, previous studies showed that the cleavage of MLL by Taspase1 occurred in the cytoplasm3 and that free MLLC180 could be exported to the cytoplasm7, thus raising the possibility that MLL might possess some underappreciated functions in the cytoplasm. To identify possible MLL-binding proteins in a more comprehensive manner, total 293T cell extracts were used for MLL affinity purification followed by LC/MS analysis. As expected, we acquired a number of previously identified MLL-binding proteins including MENIN, ASH2L, and WDR56. Interesting, we repeatedly identified several cytoplasmic proteins, including P-body components such as YB-1, EDC3, DDX6, UPF1, and PABPC1 (Supplementary Table S1), suggesting a physical interaction between MLL and these P-body components.

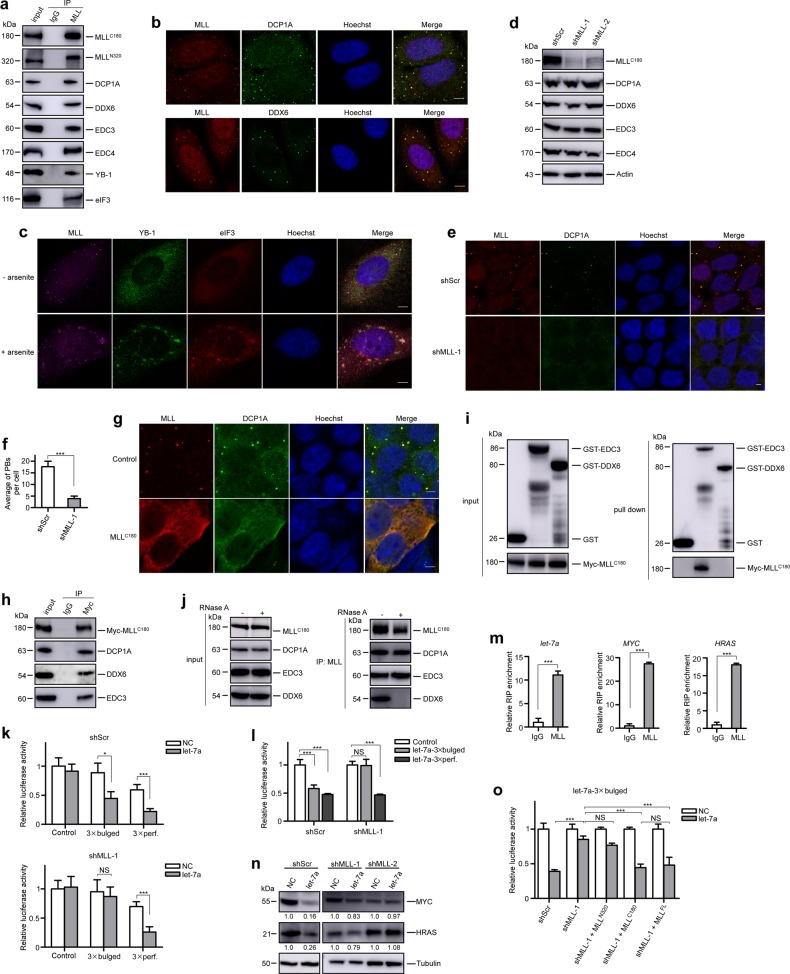

In mammalian cells, P-bodies contain nontranslated mRNAs and the conserved core of proteins involved in the decay and translational repression of mRNAs8. These factors include the decapping enzymes DCP1A and DCP2, the decapping activators EDC3, EDC4, and DDX68. To verify the connections between MLL and P-bodies, we examined several P-body marker proteins including DCP1A, DDX6, EDC3, and EDC4 in endogenous MLL immunoprecipitates, and confirmed a physical interaction between MLL and these P-body components (Fig. 1a and Supplementary Fig. S1a). Furthermore, we demonstrated that these interactions preferentially occur in cytoplasm, but not in nucleus (Supplementary Fig. S1b).

Fig. 1. MLL localizes to P-bodies and is essential for P-body integrity.

a The total lysates of 293T cells were prepared and subjected to immunoprecipitation using anti-MLL antibodies. Copurified proteins were examined by immunoblots using the indicated antibodies. Specific antibodies were used to detect the MLLN320 and MLLC180, respectively. b The localization of endogenous MLL and P-body markers in 293T cells was visualized by immunofluorescence using indicated antibodies. Scale bar, 5 μm. c 293T cells were untreated (upper panels) or arsenite treated (0.5 mM, 45 min) (lower panels), then fixed and stained with indicated antibodies. Note that YB-1 is detectable in P-bodies in unstressed cells, and relocalized to stress granule upon arsenite treatment, whereas eIF3 is specific for stress granule. d Knockdown of MLL by targeting three independent sequences and its effect on the expression of P-body proteins were examined by western blot using indicated antibodies. e 293T-shScr and 293T-shMLL cells were examined by immunofluorescence using antibodies against MLL and DCP1A. Scale bar, 5 μm. f Detectable P-bodies detected by immunofluorescence using antibodies against DCP1A were quantified for all cells in the field of view (×126 magnification) and data from at least three random fields were collected and analyzed using Image J. g MLLC180 alone was overexpressed in 293T cells, then immunofluorescence experiments were performed using antibodies against MLLC180 (Bethyl) and DCP1A. Scale bar, 5 μm. h 293T cells were transfected with MLLC180, cell cytoplasm fractions were prepared for the coimmunoprecipitation assays using the indicated antibodies. i Direct interactions between MLLC180 and GST-EDC3, GST-DDX6 were examined. Left panels: western blots shown the inputs of purified GST-EDC3, GST-DDX6, and Myc-MLLC180. Right panels: the pull down immunoblots were shown with GST-EDC3 and GST-DDX6 as the baits and the pulled MLLC180 detected by an anti-Myc antibody. j 293T cell lysates were treated with RNase A followed by anti-MLL immunoprecipitation. Western blots were performed using indicated antibodies. k 293T-shScr and shMLL cells transfected with Agomir-negative control (NC) or Agomir-let-7a mimic (let-7a) were subjected to dual luciferase reporter assays. The ratio of luciferase activity was measured and normalized to the value of the cells transfected with the control reporter and NC. l The effects of MLL knockdown on the function of endogenous let-7a were analyzed using dual luciferase reporter assays. The ratio of luciferase activity was measured and normalized to the value of the cells transfected with the control reporter in each cell line. m Lysates of 293T cells were prepared and subjected to anti-MLL RIP or mock RIP using IgG. Pull-downed RNAs were analyzed by qRT-PCR. n 293T-shScr and 293T-shMLL cells were transfected with NC and let-7a. After 24 h of transfection, cell lysates were prepared and assessed by anti-MYC and anti-HRAS western blots. The ratio of protein levels was normalized to the value of the cells transfected with the NC. o 293T-shMLL cells were transfected with shRNA-resistant MLLC180, MLLN320 or full-length MLL (MLLFL) to determine which of these subunits could relief the dysregulated let-7a mediated gene silencing due to MLL knockdown. Experiments were performed as described in Fig. 1k. The ratio of luciferase activity was measured and normalized to the value of the cells transfected with the NC. *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01, ***P < 0.001. NS, no significant difference. Data represent mean and s.e.m of three independent experiments

To determine whether MLL localizes to P-body foci, we examined the localization of MLL. Although MLL dominantly localized to the nucleus, a significant portion of MLL was present in discrete cytoplasmic foci, colocalizing with P-body marker proteins such as DCP1A, DDX6, EDC3, and EDC4 (Fig. 1b and Supplementary Figs. S1c–e). P-bodies and stress granules (SGs) are two closely related cytoplasmic mRNP granules, sharing some common components such as YB-19. YB-1, which partially presented in P-bodies when cells were untreated, predominantly relocalized into SGs after sodium arsenite treatment10. Since our results showed that YB-1 as well as SG marker eIF3 was binding partner of MLL (Fig. 1a and Supplementary Fig. S1a), we also investigated whether MLL was a component of SGs. We found that MLL colocalized with a portion of YB-1 in untreated cells. Upon sodium arsenite treatment, part of MLL together with the majority of YB-1 relocalized to SGs as indicated by the SG marker eIF3, while the rest of the cytoplasmic MLL mainly remained in the P-bodies with DCP1A (Fig. 1c and Supplementary Fig. S1f). Thus, these results demonstrated that MLL was present not only in P-bodies but also in the closely related SGs.

Previous studies have shown that different components of P-bodies have various effects on P-body integrity9. We sought to determine the role of MLL on P-body integrity by examining the effects of MLL depletion on the formation of P-bodies in MLL knockdown 293T cells and Mll knockout MEF cells. Depletion of MLL caused a significant decrease in DCP1A- or DDX6-associated P-bodies without affecting the protein levels of P-body components (Fig. 1d–f and Supplementary Fig. S1g–l). These results revealed that MLL was required for the maintenance of P-bodies.

We next investigated which MLL subunit was involved in P-body assembly. Consistent with previous reports, ectopically expressed MLLN320 and MLLC180 alone were predominantly localized in the nucleus and the cytoplasm, respectively (Fig. 1g and Supplementary Fig. S2a, b). In contrast, MLLC180 from ectopically expressed full-length MLL was predominantly localized to the nucleus (Supplementary Fig. S2c, d), suggesting that MLLC180 was normally constrained in the nucleus by MLLN320. Interestingly, overexpression of MLLC180 alone led to disruption of microscopic P-body foci without affecting the protein levels of P-body components; however, MLLC180 still remained colocalized with P-body components in a diffuse pattern (Fig. 1g, h and Supplementary Fig. S2b, e). We further demonstrated that EDC3, but not DDX6, could pull down MLLC180, indicating a direct interaction between MLLC180 and at least some of the P-body components (Fig. 1i). Co-IP experiments further revealed that the interaction between MLL and DDX6 decreased dramatically after RNase A treatment, indicating that this interaction was an RNA-dependent indirect interaction, rather than a direct protein–protein interaction (Fig. 1j and Supplementary Fig. S2f). In contrast, the interactions between MLL and other P-body components including DCP1A and EDC3 were not affected by RNase A treatment (Fig. 1j and Supplementary Fig. S2f). These results thus revealed that it was MLLC180 that interacted with P-body components directly and was crucial for maintaining P-body integrity.

miRNA-mediated gene silencing takes place in the P-bodies11. However, the loss of visible P-body foci does not necessarily mean a defect in miRNA-mediated gene silencing12. Given that depletion of MLL could affect the integrity of P-bodies, we sought to determine whether MLL depletion would affect miRNA-mediated gene silencing. Mature miRNAs cause gene silencing either by cleaving perfectly matched mRNAs or by suppressing the translation of partially matched mRNAs13. To determine which type of miRNA-mediated gene silencing would be affected by MLL, we used different luciferase reporters harboring perfect or bulged let-7a target sites to distinguish between these two types of miRNA-mediated gene silencing (Supplementary Fig. S3a). Interestingly, depletion of MLL impaired the function of let-7a mimics as well as endogenous let-7a to silence the imperfect target but had little effect on the perfect target (Fig. 1k, l and Supplementary Fig. S3b, c). The mature expression levels of the shRNA control and the MLL-targeting shRNA were not only equally abundant, but were also similarly bound to AGO2 (Supplementary Fig. S3d), thus excluding the possibility that differing reporter activity levels were caused by a competitive effect of mature shRNAs on Argonaute proteins that affected endogenous miRNAs14. The preferential effect of MLL in miRNA-mediated silencing of imperfect targets was further documented by CXCR4 reporter assays (Supplementary Fig. S3a, e).

To explore which miRNAs and mRNA targets could be affected by MLL, we first performed RNA immunoprecipitation (RIP) to identify the miRNAs and their mRNA targets associated with MLL. The RIP-seq results demonstrated a plethora of MLL-binding miRNAs including let-7a, miR-10a, and miR-196b (Supplementary Table S2), which were further validated by qRT-PCR (Fig. 1m and Supplementary Fig. S3f). In addition, among MLL-binding mRNAs we identified MYC and HRAS, two well-characterized targets of let-7a15 (Fig. 1m and Supplementary Table S3), suggesting that translational regulation of MYC and HRAS by let-7a might be affected by MLL. We therefore evaluated whether the expression of MYC and HRAS proteins could escape translational suppression by let-7a in MLL-depleted cells. In the control cells, MYC and HRAS protein levels decreased significantly upon treatment with let-7a mimics. In contrast, MYC and HRAS protein expression in MLL-depleted cells showed no obvious decrease when cells were transfected with let-7a (Fig. 1n and Supplementary Fig. S3g). In addition, the ratio of MYC protein to mRNA was much higher in MLL-depleted cells (Supplementary Fig. S3h), indicating that translational suppression of MYC mRNA occurred in an MLL-dependent manner. Together with the previous reporter assays, these results suggested that MLL was required for the translational repression mediated by a subset of miRNAs, especially let-7a.

To demonstrate that MLL plays a causal role in the recruitment of miRNA to miRISC, we reintroduced shRNA-resistant MLLC180, MLLN320 or full-length MLL into MLL knockdown 293T cells and Mll knockout MEF cells and found that the introduction of MLLC180 but not MLLN320 could partially reverse the deficits in miRNA activity caused by loss of endogenous MLL, as evaluated by reporter assays (Fig. 1o and Supplementary Fig. S3i, j). Taken together, these results revealed that MLL plays a causal role in targeting miRNAs to form a functional miRISC complex.

A consensus has developed that mature MLL serves as an epigenetic regulator in the form of an intramolecular complex. However, our findings have revealed, for the first time to the best of our knowledge, that MLL subunits do not have to bind each other to be functional; instead, they can be separated and exert additional functions. Since MLL subunits can only be separated when MLL is processed by Taspase1, our findings reinforce the concept that the processing of MLL is vital to proper MLL function.

Supplementary information

Acknowledgements

We thank James Hsieh for providing essential materials and initial support to this project. This work was supported by the National Key Research and Development Program of China (2018YFA0107802), the National Natural Science Foundation of China (81570119 and 81370651), the Program of Shanghai Academic/Technology Research Leader (19XD1402500), the Shanghai Municipal Education Commission Gaofeng Clinical Medicine Grant (20161304), the Shanghai Municipal Health Commission (2019CXJQ01), the Shu Guang project supported by Shanghai Municipal Education Commission and Shanghai Education Development Foundation (14SG15), the Collaborative Innovation Center of Hematology, and the Samuel Waxman Cancer Research Foundation.

Authors’ contributions

S.H.Z., Z.H.C., R.H.W., and Y.T.T. designed and performed most of the experiments, analyzed the data, and wrote the draft manuscript. M.L.G. and Y.T.H performed some experiments and data analyses. C.J.Z., Z.C., and S.J.C provided expertize and extensively edited the manuscript. H.L. contributed grant support, designed the entire project, wrote the manuscript, and supervised the project. All authors discussed the results and commented on the manuscript.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

Footnotes

Publisher’s note: Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

These authors contributed equally: Shouhai Zhu, Zhihong Chen, Ruiheng Wang, Yuting Tan

Supplementary information

Supplementary Information accompanies the paper at (10.1038/s41421-019-0111-0).

References

- 1.Tkachuk DC, Kohler S, Cleary ML. Involvement of a homolog of Drosophila trithorax by 11q23 chromosomal translocations in acute leukemias. Cell. 1992;71:691–700. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(92)90602-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Nakamura T, et al. ALL-1 is a histone methyltransferase that assembles a supercomplex of proteins involved in transcriptional regulation. Mol. Cell. 2002;10:1119–1128. doi: 10.1016/S1097-2765(02)00740-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Hsieh JJ, Cheng EH, Korsmeyer SJ. Taspase1: a threonine aspartase required for cleavage of MLL and proper HOX gene expression. Cell. 2003;115:293–303. doi: 10.1016/S0092-8674(03)00816-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Yano T, et al. Nuclear punctate distribution of ALL-1 is conferred by distinct elements at the N terminus of the protein. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA. 1997;94:7286–7291. doi: 10.1073/pnas.94.14.7286. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Yokoyama A, et al. Leukemia proto-oncoprotein MLL forms a SET1-like histone methyltransferase complex with menin to regulate Hox gene expression. Mol. Cell. Biol. 2004;24:5639–5649. doi: 10.1128/MCB.24.13.5639-5649.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Dou Y, et al. Regulation of MLL1 H3K4 methyltransferase activity by its core components. Nat. Struct. Mol. Biol. 2006;13:713–719. doi: 10.1038/nsmb1128. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Yokoyama A, et al. Proteolytically cleaved MLL subunits are susceptible to distinct degradation pathways. J. Cell Sci. 2011;124:2208–2219. doi: 10.1242/jcs.080523. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Eulalio A, Behm-Ansmant I, Izaurralde E. P bodies: at the crossroads of post-transcriptional pathways. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 2007;8:9–22. doi: 10.1038/nrm2080. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Decker CJ, Parker R. P-bodies and stress granules: possible roles in the control of translation and mRNA degradation. Cold Spring Harb. Perspect. Biol. 2012;4:a012286. doi: 10.1101/cshperspect.a012286. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Kedersha N, Anderson P. Mammalian stress granules and processing bodies. Methods Enzymol. 2007;431:61–81. doi: 10.1016/S0076-6879(07)31005-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Chu CY, Rana TM. Translation repression in human cells by microRNA-induced gene silencing requires RCK/p54. PLoS Biol. 2006;4:e210. doi: 10.1371/journal.pbio.0040210. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Franks TM, Lykke-Andersen J. The control of mRNA decapping and P-body formation. Mol. Cell. 2008;32:605–615. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2008.11.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Peters L, Meister G. Argonaute proteins: mediators of RNA silencing. Mol. Cell. 2007;26:611–623. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2007.05.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Grimm D, et al. Fatality in mice due to oversaturation of cellular microRNA/short hairpin RNA pathways. Nature. 2006;441:537–541. doi: 10.1038/nature04791. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Bussing I, Slack FJ, Grosshans H. let-7 microRNAs in development, stem cells and cancer. Trends Mol. Med. 2008;14:400–409. doi: 10.1016/j.molmed.2008.07.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.