Abstract

The glassy carbon electrode was fabricated with multifunctional bis-triazole-appended calix[4]arene and then used for the simultaneous detection of Zn(II), Pb(II), As(III), and Hg(II). Before applying the square-wave anodic stripping voltammetry, the sensitivity and precision of the modified electrode was assured by optimizing various conditions such as the modifier concentration, pH of the solution, deposition potential, accumulation time, and supporting electrolytes. The modified glassy carbon electrode was found to be responsive up to picomolar limits for the aforementioned heavy metal ions, which is a concentration limit much lower than the threshold level permitted by the World Health Organization. Importantly, the designed sensing platform showed anti-interference ability, good stability, repeatability, reproducibility, and applicability for the detection of multiple metal ions. The detection limits obtained for Zn(II), Pb(II), As(III), and Hg(II) are 66.3, 14.6, 71.9, and 28.9 pM, respectively.

1. Introduction

Heavy metals (HMs) are highly toxic, nonbiodegradable, persistent, and ubiquitously distributed, thus posing a great threat to the biosphere. The major cause of these pollutants is the anthropogenic activities including mining, smelting, and various other industrial processes. These toxins enter into the body of living organisms through the food chain and induce severe health effects.1−4 Some HMs such as iron, cobalt, zinc, copper, and manganese are important in trace amounts, but their excess leads to toxic effects in humans.5,6 While other HMs, that is, lead, arsenic, mercury, cadmium, etc., are considered highly toxic even at very low concentrations. The toxicity of these HMs is declared by the “Agency for Toxic Substances and Disease Registry Priority List of Hazardous Substances” and World Health Organization (WHO).7−11 The excess of HMs results in enzyme inhibition, oxidative stress, and impaired antioxidant metabolism. Moreover, these have been reported to cause lethal effects in living organisms by free-radical generation and could end up with mutations in DNA,12−17 reduction of protein sulfhydryl, and lipid peroxidation.3,6,18 For instance, the presence of Pb(II) ions above a certain level of its threshold causes neurodegenerative diseases, kidney damage, bone growth retardation, hyperirritability, and ataxia.19 Similarly, the presence of mercury causes kidney failure, vestibular dysfunction, respiratory track damage, autism, birth defects, speech impairment, and skin diseases after exceeding its threshold limit.20 Likewise, zinc is another heavy metal, and the excess of which leads to cardiac dysfunction, DNA damage, and gene mutation.21 Moreover, arsenide (As(III)) being the most toxic is associated with several deadly diseases such as skin lesions, lung cancer, keratosis, bladder cancer, etc. Therefore, it is important to develop analytical tools to detect and quantify the HM ions in drinking water reservoirs.

The analytical methods commonly used for HM ion detection are atomic absorbance spectroscopy, atomic emission spectroscopy, inductively coupled plasma mass spectroscopy, and X-ray fluorescence. These methods are of great significance, but their cost, time consumption, and requirement of large sample volumes and highly skilled operators limit their operations at small scales. The electrochemical techniques, particularly stripping voltammetry, on the other hand, are promising alternatives and extensively used for HM ion detection owing to their simple design, portability, faster analysis speed, greater sensitivity, and improved selectivity.22−27 Suitable modifiers are used for boosting up the sensitivity of the working electrode.28−30 Bis-triazole-appended calix[4]arene (BTC) was selected as an electrode modifier owing to its amphipathic structure. The insolubility of BTC in aqueous solutions due to the dominance of its hydrophobic character and presence of hydrophilic groups such as 1,2,3-triazole, alkoxy, hydroxyl, and aldehyde functional groups suitable for binding to metal ions makes the selected modifier useful for electrode modification. It possesses electrode-anchoring hydrophobic groups and metal ion-binding groups, thus acting as a conducting bridge between the host (transducer) and guest (target metal ions). Thus, in the present work, the synthesized BTC modifier was drop-casted on a glassy carbon electrode surface. The designed electrochemical sensing platform presents a cost-effective and novel approach for the sensitive and selective determination of Zn(II), Pb(II), As(III), and Hg(II) in laboratory samples as well as in real samples. The proposed method offers a feasible way for on-site detection of heavy metal cations, particularly, the most lethal, As(III) and Hg(II) in water.

2. Results and Discussion

2.1. Synthesis of Bis-triazole-Appended Calix[4]arene (BTC)

The detailed synthesis, characterization, and X-ray diffraction studies of BTC have already been published by our research group.31 The brief outline for its synthesis is shown in Scheme 1.

Scheme 1. Synthesis of BTC (8).

(i) Acetone, K2CO3, 60 °C, 3 h, 91%; (ii) CH3CN, K2CO3, 60 °C, 4 h, 68%; (iii) DMF, NaN3, 70 °C, 1 h, 90%; and (iv) DMF, sodium ascorbate, CuSO4·5H2O, 2 h, 73%.

2.2. Electrochemical Characterization of the Bis-triazole-Based Calix[4]arene-Modified GCE

The changes in the surface properties of the GCE were analyzed by cyclic voltammetry and electrochemical impedance spectroscopy after modification with BTC. Meanwhile, cyclic voltammetry (CV) was also carried out using bare and modified GCEs in a solution mixture of 5 mM potassium ferricyanide (K3[Fe(CN)6]) and 0.1 M KCl. The experimental results displayed a great enhancement in current values for oxidation and reduction of the potassium ferri/ferrocyanide redox couple as shown in Figure 1.32−35 The observed enhancement in the current values was attributed to more active sites and an increased surface area of the modified GCE. Thus, the assembling of BTC on GCE was confirmed to be used as a modifier for improved sensing of metal ions.

Figure 1.

Cyclic voltammograms of (a) bare and (b) modified GCEs in a 5 mM solution of K3[Fe(CN)6] containing 0.1 M KCl.

Moreover, EIS studies were performed under a similar environment as shown in Figure 2. A semicircular arc and a straight line were obtained in a Nyquist plot. The diameter of the semicircle in the Nyquist plot that corresponds to charge transfer resistance (Rct) controls the charge transfer process on the electrode/electrolyte interface. A significant decrease in the diameter of the semicircular arc after the modification of the GCE with BTC reveals an increase in charge transfer kinetics at the modified electrode. The obtained EIS results are in good agreement with the results of cyclic voltammograms.

Figure 2.

Nyquist plot obtained with bare and modified electrodes in a 5 mM K3[Fe(CN)6] solution containing 0.1 M KCl using electrochemical impedance spectroscopy.

2.3. Metal Ion Chelation

After the successful modification of GCE with BTC, square-wave anodic stripping voltammetry (SWASV) was performed on the solution mixture containing Zn(II), Pb(II), As(III), and Hg(II) in 50% BRB solution at pH 3 using both bare (control) and modified GCEs as shown in Figure 3. The BTC-modified GCE displayed a more intense current response as compared to unmodified GCE. This increase in current signals of metal ions can be attributed to the effective binding of metal cations with carbonyl, hydroxyl, and triazole functionalities present in BTC. The binding of the BTC with metal ions facilitates the accessibility of metal ions at the electrode–solution interface and enhances the electroplating efficacy in the deposition step. Moreover, the electron-rich functionalities in the BTC molecules offer adsorption sites for metal ions to form a metal atom–metal ion couple, which is essential for enhanced current responses. Therefore, the immobilized layer of BTC serves as a venturing stone among metal ions (analytes) and electrodes for rapid electron transfer. The modifier is insoluble in water due to its hydrophobic nature. Therefore, when the modified electrode is kept in solution for analyte detection, the modifier stays on the electrode and does not go into the analyte solution. We anticipate that the excellent conductivity of the used modifier is due to the presence of electron-rich functionalities in its chemical structure, orientation of its water soluble moieties toward the solution, and their ability of bending to act as a communication link between the electrode and analytes.

Figure 3.

SWASV of the (a) modified electrode in solvent (water and BRB of pH 3.0) and (b) unmodified and (c) modified electrodes in 1.2 mM solutions of Zn(II), Pb(II), As(III), and Hg(II) at a scan rate of 50 mV/s and deposition time of 50 s.

2.4. Optimization of Experimental Conditions

The influence of stripping conditions such as the amount of modifier, pH of the sample, supporting electrolyte, scan rate, accumulation potential, and accumulation time on voltammetric responses of the selected metal ions was examined with the BTC-modified GCE. The details are given below.

2.4.1. Amount of Modifier

The effect of the concentration of BTC on the current values of metal ions was investigated, and the increase in the peak current was observed until the achievement of the saturation point. The enhancement in current signals with an increase in the concentration of the modifier indicates an increase in the surface area of the GCE. Meanwhile, a further increase in the modifier concentration after the saturation point leads to a decrease in peak current values. The decrement in current signals is because of the multilayer formation of BTC molecules on the GCE surface and results in deactivation of the modified electrode due to hindrance of the electron transmission processes. The maximum peak current values (the saturation point) for Zn(II), Pb(II), As(III), and Hg(II) were observed at 1 mM concentration of BTC as shown in Figure 4.

Figure 4.

Effect of immobilized dosage of BTC on the striping peak current of metal ions, i.e., Zn(II), Pb(II), As(III), and Hg(II).

2.4.2. Accumulation Time

The deposition time was also found to play a critical role in improving the sensitivity of the modified GCE. The effect of accumulation time on the voltammetric response of the selected metal ions was studied within the range of 10 to 60 s using SWASV as shown in Figure 5. It was found that the current values increase linearly with the increase in accumulation time as more metal ions get reduced on the surface of the modified electrode. A further increase in the accumulation time led to a decrease in peak current values probably due to the rapid saturation of the active sites on BTC by metal ions. The highest current response was obtained at 50 s, which was thus considered to be the optimum time for further experiments.

Figure 5.

Effect of accumulation time on the SWASV current response for 1.2 mM solutions of Zn(II), Pb(II), As(III), and Hg(II). The supporting electrolyte is BRB (pH = 3), the scan rate is 50 mV/s, and the pulse amplitude is 25 mV (inset plot of Ip vs td).

2.4.3. Accumulation Potential

Similarly, the deposition potential is another important parameter to be considered in electrochemical detections; thus, the effect of the deposition potential on electrode sensitivity was performed for Zn(II), Pb(II), As(III), and Hg(II) in the deposition potential range of −1 to −1.4 V. The enhancement in the current signals was observed in the potential window of −1.0 to −1.2 V. A further increase in potential from −1.2 to −1.4 V leads to a decrease in current signals. This reduction in current signals at a higher negative potential is because of the hydrogen gas evolution. Hence, further experiments were performed at the selected optimum deposition potential of −1.2 V in order to avoid hydrogen gas evolution for best sensing results (Figure S1 of the Supporting Information).

2.4.4. Supporting Electrolytes

The effect of various supporting electrolytes, that is, BRB of pH 3, KCl, CH3COOH, H3PO4, and HCl solutions on the current signals of metal ions was also investigated as shown in Figure S2 of the Supporting Information. The optimum results were obtained in the presence of BRB (pH = 3), and therefore BRB (pH = 3) was selected as an electrolyte in further experiments.

2.4.5. pH Effect

The ionization of various functional groups present in the structure of BTC responsible for binding metal ions is highly affected by the pH of the solution. Thus, the effect of pH was studied by varying the pH of the analyte solution from pH 2 to pH 6 in order to assess the sensing ability of the electrode. The best response was observed at pH 3 as shown in Figure 6. The enhancement in current signals at pH 3 is because of the rapid exchange of metal ions with the protons generated by functional groups of modifiers. The corresponding decrease in peak current values at higher-pH media could be the result of a decrease in ionization of functional groups and availability of fewer ion-exchange sites by hydrolysis of metal ions.

Figure 6.

Effect of pH on the current signal of 1.2 mM solutions of Zn(II), Pb(II), As(III), and Hg(II) using the BTC-modified GCE in BRB of different pH values of 2–6 under optimized conditions.

2.5. Interference Study

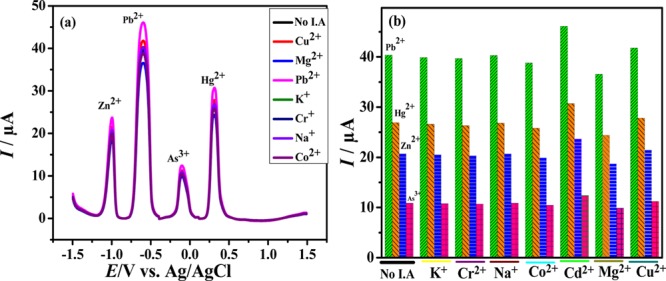

In real samples, various other competitive metal ions are also present along with the analytes and can influence the sensing of a particular analyte. Therefore, the effect of various possible metal ions on the electrode sensing of Zn(II), Pb(II), As(III), and Hg(II) was investigated in the present work. The metal ions used as interfering agents were K+, Cr2+, Na+, Co2+, Cd2+, Mg2+, and Cu2+. It can be observed from Figure 7 that the presence of interfering species in a two-fold higher concentration than that of the analyte slightly affects the peak currents of the target analytes, thus signifying resistance of the developed electrochemical sensor for interfering ions.

Figure 7.

Effect of various interfering agents on the SWASV (a) voltammogram and (b) peak current of the analytes using the BTC-modified GCE.

2.6. Reproducibility of the Bis-triazole-Based Calix[4]arene-Modified GCE

In order to assess the reproducibility of the modified electrode, six repetitive oxidative measurements of electrodeposited Zn(0), As(0), Hg(0), and Pb(0) were recorded by the BTC-modified GCE using SWASV as shown in Figure S3. No obvious contradictions in the stripping current values of 0.8 mM Zn(II), Pb(II), As(III), and Hg(II) were found. These results justify significant reproducibility of the modified electrochemical sensing platform. The relative standard deviation (RSD) was calculated to be less than 4%. Hence, the developed BTC-modified GCE displayed adequate reproducibility for repetitive electrochemical determinations of heavy metal ions.

2.7. Simultaneous Determination of Zn(II), Pb(II), As(III), and Hg(II)

SWASV was also used for the simultaneous detection of the selected metal ions under optimized conditions. The resulting electrochemical sensor showed a robust analytical response at different concentrations of Zn(II), Pb(II), As(III), and Hg(II) as shown in Figure 8.

Figure 8.

SWASV curves obtained for simultaneous detection of Zn(II), Pb(II), As(III), and Hg(II) in the concentration range of 0.9 mM to 7 nM with the BTC-modified GCE.

Excellent calibration curves were obtained for Zn(II), Pb(II), Hg(II), and As(III) in the concentration range of 0.9 mM to 7 nM with regression coefficients of 0.9974, 0.998, 0.998, and 0.998, respectively. The limits of detection found for Zn(II), Pb(II), Hg(II), and As(III) with respective values of 66.3, 14.6, 28.9, and 71.9 pM are tabulated in Table 1. These LOD values are also lower than those reported in the literature.36−43

Table 1. Comparison of the Proposed Sensor with Previously Reported Electrochemical Sensors for the Simultaneous Determination of Zn(II), Hg(II), Pb(II), and As(III).

| modified electrode | method | LOD of Zn2+ | LOD of Pb2+ | LOD of As3+ | LOD of Hg2+ | refs |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| HMDE | DPCSV | 7.0 nM | 1.3 nM | (36) | ||

| [Ru(bpy)3]2+-GO/GE | DPV | 1.41 nM | 2.30 nM | 1.60 nM | (37) | |

| graphene/CeO2/GCE | DPASV | 0.1 nM | 0.2771 nM | (38) | ||

| HAP-Nafion/GCE | DPASV | 0.05 μM | 0.03 μM | (39) | ||

| BiFEs | SWASV | 0.615 μM | 192 nM | (40) | ||

| γ-AlOOH@SiO2/Fe3O4/GCE | SWASV | 0.04 μM | 2.0 nM | 0.02 μM | (41) | |

| HMDE | DPASV | 21 nM | 7.1 nM | (42) | ||

| AuNPs/CNFs/GCE | SWASV | 0.1 μM | (43) | |||

| BTC-GCE | SWASW | 66.3 pM | 14.6 pM | 71.9 pM | 28.9 pM | this work |

2.8. Analysis of Real Samples

In order to check the accuracy of the proposed electrochemical sensing method in real-world outdoor applications, the BTC-modified GCE was employed for monitoring Zn(II), Pb(II), As(III), and Hg(II) in real water samples collected from Rawal Lake, Islamabad, Pakistan, tap water, and drinking water. In this experiment, the stock solutions of metal ions in real water samples were diluted with 50% BRB (pH = 3) with no more sample treatment. The amounts of Zn(II), Pb(II), As(III), and Hg(II) in lake, tap, and drinking water samples were determined by the traditional standard addition method by spiking known amounts of Zn(II), Pb(II), As(III), and Hg(II). Excellent recoveries were observed for Zn(II), Pb(II), As(III), and Hg(II) in all three samples listed in Table 2.

Table 2. Results of Recovery Experiments (ND: Not Detected, i.e., below the Limits of Detection).

| Pb2+ concentration (μM) |

Zn2+ concentration (μM) |

As3+ concentration (μM) |

Hg2+ concentration (μM) |

|||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| sample no. | original | added | found | recovery | original | added | found | recovery | original | added | found | recovery | original | added | found | recovery |

| (1) lake water sample | ND | 0.9 | 0.89 | 98.88% | 0.04 | 0.9 | 0.89 | 98.88% | ND | 0.9 | 0.88 | 97.77% | ND | 0.9 | 0.89 | 98.88% |

| (2) drinking water sample | ND | 0.6 | 0.59 | 98.33% | ND | 0.6 | 0.58 | 96.66% | ND | 0.6 | 0.59 | 98.33% | ND | 0.6 | 0.6 | 99.83% |

| (3) tap water sample | ND | 0.3 | 0.298 | 99.33% | 0.01 | 0.3 | 0.3 | 98.33% | ND | 0.3 | 0.3 | 99.66% | ND | 0.3 | 0.3 | 100% |

3. Conclusions

In summary, we introduced novel bis-triazole-based calix[4]arene-modified GCE for the simultaneous sensing of four types of metal ions, that is, Zn(II), Pb(II), As(III), and Hg(II). The modifier resulted in a higher surface area of the electrode, increased metal ion accumulation at the electrode/electrolyte interface, and improved conductivity resulting in enhanced sensitivity and performance of the designed electrochemical platform. The designed modified electrode is cost effective, easy to fabricate, regenerative, and environmentally benign. The voltammetric stripping measurements showed that the designed electrode surface has excellent repeatability and high sensitivity and selectivity. It also showed good reproducibility and displayed wide linear concentration ranges for the respective target analytes with detection limits of 66.3, 14.6, 28.9, and 71.9 pM for Zn(II), Pb(II), Hg(II), and As(III), respectively. In addition, the recommended sensing platform was effectively utilized for the simultaneous detection of these ions in real water samples.

4. Experimental Section

4.1. Chemical Reagents

All chemicals used in this study were of analytical grade and used without any further purification. The Britton-Robinson buffer (BRB) was employed as a supporting electrolyte in the pH range 2–6. Deionized water was used for the preparation of different metal ion solutions, and the solution of BTC was prepared in DMSO. The experiments were performed under a nitrogen gas atmosphere in order to evacuate atmospheric oxygen and avoid unnecessary oxidation.

4.2. Apparatus

Electrochemical impedance spectroscopy (EIS) and voltammetric investigations were performed via Metrohm Autolab PGSTAT 302 N. The conventionally used three-electrode system was employed including bare and modified glassy carbon electrodes (GCEs) as the working electrode, Ag/AgCl (saturated KCl electrode) as the reference, and platinum wire as a counter electrode. The pH measurements were carried out by an INOLAB pH meter.

4.3. Preparation of the Modified Glassy Carbon Electrode

First, the GCE surface was polished with the help of a nylon buffing pad using 0.05 μm of α-Al2O3 powder until a smooth and shiny surface of the GCE was attained. Later, the GCE was sonicated for 2 min in HNO3 (1:1, v/v), alcohol, and double-distilled water followed by washing with distilled water and drying in air. The stock solution of BTC, having its chemical structure shown in Scheme 2, was prepared in DMSO. Voltammetric studies were performed using both bare and modified GCEs. The modification of the GCE was carried out by the drop-casting method in order to enhance the surface properties of the GCE.

Scheme 2. Chemical Structure of Bis-triazole-based Calix[4]arene.

Acknowledgments

The authors gratefully acknowledge the financial support from Higher Education Commission of Pakistan and Quaid-i-Azam University, Islamabad.

Supporting Information Available

The Supporting Information is available free of charge on the ACS Publications website at DOI: 10.1021/acsomega.9b01869.

Electrochemical data presenting the influence of accumulation time, effect of various supporting electrolytes, and stability of the modified electrochemical sensor (PDF)

The authors declare no competing financial interest.

Supplementary Material

References

- Tóth G.; Hermann T.; Da Silva M. R.; Montanarella L. Heavy metals in agricultural soils of the European Union with implications for food safety. Environ. Int. 2016, 88, 299–309. 10.1016/j.envint.2015.12.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim B. G.; Hong Y. S.; Haraguchi K.; Sakomoto M.; Lim H.-J.; Seo J. W.; Kim Y. M. Comparative Screening Analytic Methods for Elderly of Blood Methylmercury Concentration between Two Analytical Institutions. Comput. Math. Methods Med. 2018, 2018, 2509413. 10.1155/2018/2509413. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kumar Jena B.; Retna Raj C. Gold nanoelectrode ensembles for the simultaneous electrochemical detection of ultratrace arsenic, Mercury, and Copper. Anal. Chem. 2008, 80, 4836–4844. 10.1021/ac071064w. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nolan E. M.; Lippard S. J. A “turn-on” fluorescent sensor for the selective detection of mercuric ion in aqueous media. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2003, 125, 14270–14271. 10.1021/ja037995g. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chow E.; Gooding J. J. Peptide modified electrodes as electrochemical metal ion sensors. Electroanalysis 2006, 18, 1437–1448. 10.1002/elan.200603558. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Coelho N. M. M.; da Silva A. C.; da Silva C. M. Determination of As (III) and total inorganic arsenic by flow injection hydride generation atomic absorption spectrometry. Anal. Chim. Acta 2002, 460, 227–233. 10.1016/S0003-2670(02)00252-0. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Li D.; Li J.; Jia X.; Han Y.; Wang E. Electrochemical determination of arsenic (III) on mercaptoethylamine modified Au electrode in neutral media. Anal. Chim. Acta 2012, 733, 23–27. 10.1016/j.aca.2012.04.030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marschner K.; Musil S.; Dědina J. Achieving 100% efficient postcolumn hydride generation for As speciation analysis by atomic fluorescence spectrometry. Anal. Chem. 2016, 88, 4041–4047. 10.1021/acs.analchem.6b00370. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sadee B.; Foulkes M. E.; Hill S. J. Coupled techniques for arsenic speciation in food and drinking water: a review. J. Anal. At. Spectrom. 2015, 30, 102–118. 10.1039/C4JA00269E. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Wojcieszek J.; Jiménez-Lamana J.; Bierla K.; Asztemborska M.; Ruzik L.; Jarosz M.; Szpunar J. Elucidation of the fate of zinc in model plants using single particle ICP-MS and ESI tandem MS. J. Anal. At. Spectrom. 2019, 683. 10.1039/C8JA00390D. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Maleki B.; Baghayeri M.; Ghanei-Motlagh M.; Zonoz F. M.; Amiri A.; Hajizadeh F.; Hosseinifar A.; Esmaeilnezhad E. Polyamidoamine dendrimer functionalized iron oxide nanoparticles for simultaneous electrochemical detection of Pb2+ and Cd2+ ions in environmental waters. Measurement 2019, 140, 81–88. 10.1016/j.measurement.2019.03.052. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Merli D.; Ferrari C.; Cabrini E.; Dacarro G.; Pallavicini P.; Profumo A. A gold nanoparticle chemically modified gold electrode for the determination of surfactants. RSC Adv. 2016, 6, 106500–106507. 10.1039/C6RA22223D. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Ivandini T. A.; Einaga Y.. Heavy Metal Sensing Based on Diamond Electrodes. In Carbon-Based Nanosensor Technology; Springer: 2017, pp 67–86. [Google Scholar]

- Cui L.; Wu J.; Ju H. Label-free signal-on aptasensor for sensitive electrochemical detection of arsenite. Biosens. Bioelectron. 2016, 79, 861–865. 10.1016/j.bios.2016.01.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Han D.-D.; Liu Z.-G.; Liu J.-H.; Huang X.-J. The size effect of Pt nanoparticles: a new route to improve sensitivity in electrochemical detection of As (III). RSC Adv. 2015, 5, 38290–38297. 10.1039/C5RA06475A. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Gao C.; Yu X.-Y.; Xiong S.-Q.; Liu J.-H.; Huang X.-J. Electrochemical detection of arsenic (III) completely free from noble metal: Fe3O4 microspheres-room temperature ionic liquid composite showing better performance than gold. Anal. Chem. 2013, 85, 2673–2680. 10.1021/ac303143x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gunderson C.; Zhang B. Microfabricated, massive electrochemical arrays of uniform ultramicroelectrodes. J. Electroanal. Chem. 2016, 781, 174–180. 10.1016/j.jelechem.2016.10.054. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hossain M. M.; Islam M. M.; Ferdousi S.; Okajima T.; Ohsaka T. Anodic Stripping Voltammetric detection of arsenic (III) at gold nanoparticle-modified glassy carbon electrodes prepared by electrodeposition in the presence of various additives. Electroanalysis 2008, 20, 2435–2441. 10.1002/elan.200804339. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Reuben A. Childhood Lead Exposure and Adult Neurodegenerative Disease. J. Alzheimer’s Dis. 2018, 64, 17–42. 10.3233/JAD-180267. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Church M. W.; Kaltenbach J. A. Hearing, speech, language, and vestibular disorders in the fetal alcohol syndrome: a literature review. Alcohol.: Clin. Exp. Res. 1997, 21, 495–512. 10.1111/j.1530-0277.1997.tb03796.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xiao L.; Wildgoose G. G.; Compton R. G. Sensitive electrochemical detection of arsenic (III) using gold nanoparticle modified carbon nanotubes via anodic stripping voltammetry. Anal. Chim. Acta 2008, 620, 44–49. 10.1016/j.aca.2008.05.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang Q.-X.; Wen H.; Peng D.; Fu Q.; Huang X.-J. Interesting interference evidences of electrochemical detection of Zn (II), Cd (II) and Pb (II) on three different morphologies of MnO2 nanocrystals. J. Electroanal. Chem. 2015, 739, 89–96. 10.1016/j.jelechem.2014.12.023. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Yao X.-Z.; Guo Z.; Yuan Q.-H.; Liu Z.-G.; Liu J.-H.; Huang X.-J. Exploiting differential electrochemical stripping behaviors of Fe3O4 nanocrystals toward heavy metal ions by crystal cutting. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces 2014, 6, 12203–12213. 10.1021/am501617a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu Z.-G.; Chen X.; Liu J.-H.; Huang X.-J. Robust electrochemical analysis of As (III) integrating with interference tests: A case study in groundwater. J. Hazard. Mater. 2014, 278, 66–74. 10.1016/j.jhazmat.2014.05.094. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu Z.-G.; Chen X.; Jia Y.; Liu J.-H.; Huang X.-J. Role of Fe (III) in preventing humic interference during As (III) detection on gold electrode: Spectroscopic and voltammetric evidence. J. Hazard. Mater. 2014, 267, 153–160. 10.1016/j.jhazmat.2013.12.054. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lai L. M. H.; Goon I. Y.; Lim M.; Hibbert D. B.; Amal R.; Gooding J. J. Gold-coated magnetic nanoparticles as “dispersible electrodes”–Understanding their electrochemical performance. J. Electroanal. Chem. 2011, 656, 130–135. 10.1016/j.jelechem.2010.12.016. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Baghayeri M.; Amiri A.; Razghandi H. Employment of Pd nanoparticles at the structure of poly aminohippuric acid as a nanocomposite for hydrogen peroxide detection. J. Electroanal. Chem. 2019, 832, 142–151. 10.1016/j.jelechem.2018.10.063. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Xu R.-X.; Yu X.-Y.; Gao C.; Liu J.-H.; Compton R. G.; Huang X.-J. Enhancing selectivity in stripping voltammetry by different adsorption behaviors: the use of nanostructured Mg–Al-layered double hydroxides to detect Cd (II). Analyst 2013, 138, 1812–1818. 10.1039/c3an36271j. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu Z.-G.; Huang X.-J. Voltammetric determination of inorganic arsenic. TrAC, Trends Anal. Chem. 2014, 60, 25–35. 10.1016/j.trac.2014.04.014. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Baghayeri M.; Alinezhad H.; Fayazi M.; Tarahomi M.; Ghanei-Motlagh R.; Maleki B. A novel electrochemical sensor based on a glassy carbon electrode modified with dendrimer functionalized magnetic graphene oxide for simultaneous determination of trace Pb (II) and Cd (II). Electrochim. Acta 2019, 312, 80–88. 10.1016/j.electacta.2019.04.180. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Khan B.; Shah M. R.; Ahmed D.; Rabnawaz M.; Anis I.; Afridi S.; Makhmoor T.; Tahir M. N. Synthesis, characterization and Cu2+ triggered selective fluorescence quenching of Bis-calix [4] arene tetra-triazole macrocycle. J. Hazard. Mater. 2016, 309, 97–106. 10.1016/j.jhazmat.2016.01.074. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sun Y.-F.; Zhao L.-J.; Jiang T.-J.; Li S.-S.; Yang M.; Huang X.-J. Sensitive and selective electrochemical detection of heavy metal ions using amino-functionalized carbon microspheres. J. Electroanal. Chem. 2016, 760, 143–150. 10.1016/j.jelechem.2015.11.028. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Zhou S.-F.; Wang J.-J.; Gan L.; Han X.-J.; Fan H.-L.; Mei L.-Y.; Huang J.; Liu Y.-Q. Individual and simultaneous electrochemical detection toward heavy metal ions based on L-cysteine modified mesoporous MnFe2O4 nanocrystal clusters. J. Alloys Compd. 2017, 721, 492–500. 10.1016/j.jallcom.2017.05.321. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang Z.; Fu X.; Li K.; Liu R.; Peng D.; He L.; Wang M.; Zhang H.; Zhou L. One-step fabrication of electrochemical biosensor based on DNA-modified three-dimensional reduced graphene oxide and chitosan nanocomposite for highly sensitive detection of Hg (II). Sens. Actuators, B 2016, 225, 453–462. 10.1016/j.snb.2015.11.091. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Locatelli C. Anodic and cathodic stripping voltammetry in the simultaneous determination of toxic metals in environmental samples. Electroanalysis 1997, 9, 1014–1017. 10.1002/elan.1140091309. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Baghayeri M.; Amiri A.; Maleki B.; Alizadeh Z.; Reiser O. A simple approach for simultaneous detection of cadmium (II) and lead (II) based on glutathione coated magnetic nanoparticles as a highly selective electrochemical probe. Sens. Actuators, B 2018, 273, 1442–1450. 10.1016/j.snb.2018.07.063. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Gumpu M. B.; Veerapandian M.; Krishnan U. M.; Rayappan J. B. B. Simultaneous electrochemical detection of Cd (II), Pb (II), As (III) and Hg (II) ions using ruthenium (II)-textured graphene oxide nanocomposite. Talanta 2017, 162, 574–582. 10.1016/j.talanta.2016.10.076. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xie Y.-L.; Zhao S.-Q.; Ye H.-L.; Yuan J.; Song P.; Hu S.-Q. Graphene/CeO2 hybrid materials for the simultaneous electrochemical detection of cadmium (II), lead (II), copper (II), and mercury (II). J. Electroanal. Chem. 2015, 757, 235–242. 10.1016/j.jelechem.2015.09.043. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang B.; Chen J.; Zhu H.; Yang T.; Zou M.; Zhang M.; Du M. Facile and green fabrication of size-controlled AuNPs/CNFs hybrids for the highly sensitive simultaneous detection of heavy metal ions. Electrochim. Acta 2016, 196, 422–430. 10.1016/j.electacta.2016.02.163. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Gao F.; Gao N.; Nishitani A.; Tanaka H. Rod-like hydroxyapatite and Nafion nanocomposite as an electrochemical matrix for simultaneous and sensitive detection of Hg2+, Cu2+, Pb2+ and Cd2+. J. Electroanal. Chem. 2016, 775, 212–218. 10.1016/j.jelechem.2016.05.032. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Pauliukaitė R.; Brett C. M. A. Characterization and application of bismuth film modified carbon film electrodes. Electroanalysis 2005, 17, 1354–1359. 10.1002/elan.200403282. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Wei Y.; Yang R.; Zhang Y. X.; Wang L.; Liu J. H.; Huang X. J. High adsorptive γ-AlOOH (boehmite)@ SiO2/Fe3O4 porous magnetic microspheres for detection of toxic metal ions in drinking water. Chem. Commun. 2011, 47, 11062–11064. 10.1039/c1cc14215a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kucukkolbasi S.; Temur O.; Kara H.; Khaskheli A. R. Monitoring of Zn (II), Cd (II), Pb (II) and Cu (II) during refining of some vegetable oils using differential pulse anodic stripping voltammetry. Food Anal. Methods 2014, 7, 872–878. 10.1007/s12161-013-9694-5. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.