Introduction

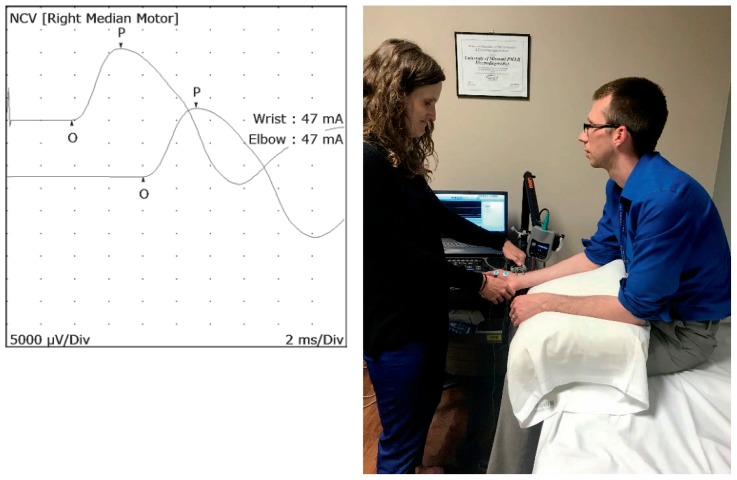

Electrodiagnostic testing includes nerve conduction studies (NCSs) and electromyography (EMG). NCSs involve applying electrical current to the nerves causing them to depolarize, inducing an action potential that is recorded, allowing the examiner to analyze various physiologic characteristics of the nerve, including latency, amplitude, and conduction velocity (Images 1 and 2). Electromyography involves putting a needle electrode into the muscle to determine to how the muscle is functioning at rest and with contraction. Different from an X-ray or MRI, electrodiagnostic studies are physiologic tests that give the examiner information about how the nerve, neuromuscular junction, and muscle are functioning.

Prior to initiating testing, the electrodiagnostic physician should take a brief history, perform a focused physical exam, and develop a differential diagnosis to guide the appropriate selection of nerves and muscles to be evaluated. This allows the studies to be comprehensive yet minimize discomfort for the patient. The physician comes to a diagnosis based on the pattern of abnormalities (or lack thereof), and frequently alters the testing of various nerves and muscles in real time based on the analysis of the results. Electrodiagnostic studies are very much like an investigation, with the outcome of the investigation dependent on the knowledge and experience of the investigator. Electrodiagnostic studies can help localize the lesion that may be causing the patient’s symptoms, rule out other diagnoses that could be causing similar symptoms, determine the severity of the lesion, and help to guide additional workup. These studies are frequently part of a complex clinical decision making process that may ultimately initiate invasive surgeries or other expensive medical treatments; therefore, its use and validity must be scrutinized.

Challenges in Electrodiagnostic Medicine

Many referring physicians are unaware that non-physician providers are performing electrodiagnostic studies in their communities. In 1999, the American Association of Electrodiagnostic Medicine (AAEM), which is now the American Association of Neuromuscular and Electrodiagnostic Medicine (AANEM), published “Guidelines in Electrodiagnostic Medicine: the Scope of Electrodiagnostic Medicine,”1 which recommended that electrodiagnostic consultants be physicians with residency training in physiatry (Physical Medicine and Rehabilitation) and neurology. Despite this recommendation, it was noted in 2004 that 16.9% of electrodiagnostic encounters billed in the United States were provided by non-physician providers, including physical therapists, podiatrists, and chiropractors.2 These non-physician providers were found to be performing electrodiagnostic examinations on younger patients with fewer comorbidities. Nonphysician providers used fewer electrodiagnostic studies (only one study per encounter) than physiatrists and neurologists (three studies per encounter), possibly leading to under-recognition of more complex diagnoses.2 It was later found that non-physician providers performing electrodiagnostic exams identified polyneuropathies in persons with diabetes only at a rate one-sixth that of physiatrists and neurologists, likely due to underutilization of NCSs.3 Substandard electrodiagnostic studies may lead to undependable results that may need to be repeated or cause unnecessary surgeries and procedures that are not successful, wasting healthcare dollars. Physical therapists, chiropractors, and podiatrists frequently lobby at the state level,2 and they continue to be permitted legally to perform electrodiagnostics in many states. In the state of Missouri, for example, under Revised Statute 334.500, physical therapists may perform electromyography and nerve conduction tests, but may not interpret the results of the electromyography or nerve conduction test; under Missouri Code of State Regulations 20 CSR 2070- 2.020(1), chiropractors are allowed to perform electromyography.

As with many other medical technologies that have been developed to improve the lives of our patients, electrodiagnostic studies have been plagued with fraud, waste, and abuse. Unfortunately, there has been unnecessary use of electrodiagnostic studies for financial gain, which prompted the department of Health and Human Services Inspector General to issue a report titled, “Questionable Billing for Medicare Electrodiagnostic Studies” in April of 2014, examining billing for the year 2011. 4 The most heavily scrutinized areas were New York, Los Angeles, and Houston; however, St. Louis, Missouri, was also named in this report. Since May of 2012, the Office of Inspector General has leveled penalties of almost $13 million in restitution and fines, along with 70 years behind bars for providers who have been guilty of fraudulent billing for electrodiagnostic exams.5 Because of the increase in fraudulent billing, the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services (CMS) significantly reduced the reimbursement for electrodiagnostic studies in 2013, ranging from 40–70%.6 These cuts in reimbursement forced many physicians performing electrodiagnostic studies to discontinue these services, which limited patient access to physicians performing these important tests. This was a big wake up call to many in the electrodiagnostic community that improvement in quality of electrodiagnostic laboratories was vital.

Nerve conduction studies involve applying electrical current to the nerves causing them to depolarize, inducing an action potential that is recorded, allowing the examiner to analyze various physiologic characteristics of the nerve, including latency, amplitude, and conduction velocity.

Recommendations for Referring Physicians

In May of 2012, AANEM updated its position statement regarding whom is qualified to perform electrodiagnostic examinations to include physicians whom have completed American Council for Graduate Medical Education (ACGME) accredited physiatry or neurology residencies and or fellowships, with direct supervision under an experienced electrodiagnostic physician for six months, and documentation of two hundred electrodiagnostic exams performed during this time.7 Physiatrists’ residency training commonly encompasses these requirements,8,9 and generally physiatrists go on to perform electrodiagnostics independently after residency. Physiatrists may additionally become board certified through the American Board of Electrodiagnostic Medicine (ABEM) or the American Board of Physical Medicine and Rehabilitation (ABPMR) Neuromuscular Medicine subspecialty. Neurologists’ exposure to electrodiagnostics in residency is variable,9 and those interested in this specialty go on to perform a one year neuromuscular or clinical neurophysiology fellowship. Neurologists may become board certified through the ABEM or the American Board of Psychiatry and Neurology (ABPN) Neuromuscular Medicine Subspecialty. We recommend getting to know the physician to whom you send your patients for electrodiagnostic studies, including their qualifications, as the quality of your electrodiagnostic examinations highly depends on the experience of the examiner.

Currently the gold standard in electrodiagnostic testing is performed in electrodiagnostic laboratories accredited by the AANEM.10 In response to the unfortunate electrodiagnostic fraud, waste, and abuse, and subsequent reduction in reimbursement of electrodiagnostic testing, the AANEM took it upon themselves to improve standardization and quality of electrodiagnostic testing throughout the United States by offering an electrodiagnostic lab accreditation process. To become accredited, electrodiagnostic laboratories must use only physicians that are either physiatrists or neurologists with appropriate residency and or fellowship training as the medical directors and the practicing physicians. The accredited laboratory must demonstrate appropriate safety standards, including records of preventative maintenance of the equipment, as well as ongoing quality improvement projects to ensure continued advancement. The accredited laboratory must show appropriate documentation of electrodiagnostic exams by submitting reports that are peer reviewed for: evidence of history and physical exam, appropriate choice of NCSs and EMG, suitable reference data for comparison, proper documentation of raw data, and correct conclusions based on the data collected. Each laboratory must undergo reaccreditation every five years to show that these criteria continue to be met. The authors of this paper have both been through this accreditation process and feel that, although tedious at times, it has been very gratifying to know we are striving to meet the highest quality standards. It is the authors’ recommendations that referring physicians look for AANEM accredited electrodiagnostic laboratories in their areas to refer their patients.11 If you are currently performing electrodiagnostic studies in your practice, the author’s highly recommend initiating the AANEM accreditation process in your laboratory to reassure your referral sources of your commitment to providing the highest quality electrodiagnostic testing for your patients.10

The Future of Electrodiagnostic Medicine

We believe the future of electrodiagnostic medicine is optimistic. Many other diagnostic tests continue to be developed in the use of neuromuscular medicine, but none that can give as much physiologic information about muscle and nerve function. After going through a very difficult growing period of uncovering fraud, waste, and abuse, the field of electrodiagnostic medicine has persevered and cultivated a culture of quality improvement, advocacy, and self-policing through recent efforts in AANEM accredited laboratories. This process, although difficult for those of us who strive for the gold standard already, has only strengthened and united many in the electrodiagnostic community to improve quality of care for our patients.

Footnotes

Chrissa McClellan, MD, MSMA member since 2016, is assistant professor, department of physical Medicine and Rehabilitation, university of Missouri-Columbia, Columbia, Missouri. Matt McLaughlin, MD, is Assistant Professor, Department of Pediatrics, University of Missouri-Kansas City, Kansas City, Missouri.

Contact: McClellanCL@health.missouri.edu

References

- 1.American Association of Electrodiagnostic Medicine. Guidelines in Electrodiagnostic Medicine, the Scope of Electrodiagnostic Medicine. Muscle & Nerve. 1999;(Suppl 8):S3–S12. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Dillingham T, Pezzin L, Rice J. Electrodiagnostic Services in the United States. Muscle & Nerve. 2004;29:198–204. doi: 10.1002/mus.10553. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Dillingham T, Pezzin L. Under-Recognition of Polyneuropathy in Persons with Diabetes by Nonphysician Electrodiagnostic Service Providers. Am J Phys Med Rehab. 2005;84:399–406. doi: 10.1097/01.phm.0000163863.85719.6e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Department of Health and Human Services, Office of Inspector General. Questionable Billing for Medicare Electrodiagnostic Tests. Apr, 2014. OEI-04-12-00420. [Google Scholar]

- 5.AANEM News Express: Seven High Profile NCS Fraud Cases. https://oig.hhs.gov/oei/reports/oei-04-12-00420.asp.

- 6.AANEM advocacy. https://www.aanem.org/getmedia/cd20f185-3a25-4803-a166-30cde3233a47/Cuts-talking-points.pdf.

- 7.AANEM Position Statement: Who is Qualified to Practice Electrodiagnostic Medicine? May, 1999. Updated May 2012 https://www.aanem.org/getmedia/1e53beb2-987d-4f06-b091-ebe56148a8b9/Who-is-Qualifed-to-Practice-EDX-2012.pdf.

- 8.ACGME Program Requirements for Graduate Medical Education in Physical Medicine and Rehabilitation. Effective. Jul 1, 2019. https://www.acgme.org/Portals/0/PFAssets/ProgramRequirements/340_PhysicalMedicineRehabilitation_2019_TCC.pdf?ver=2019-03-27-090248-423.

- 9.New Study Shows Disparities in Electrodiagnostic Training in Residency Programs. AANEM Express. 2019 Jan 2; [Google Scholar]

- 10.http://www.aanem.org/Practice/EDX-Laboratory-Accreditation

- 11.http://www.aanem.org/Practice/EDX-Laboratory-Accreditation/Find-an-Accredited-Lab?state=mo