Abstract

Objective

Telehealth has been established as a viable option for improved access and timeliness of care. Physician-guided patient self-evaluation may improve the viability of telehealth evaluation; however, there are little data evaluating the efficacy of self-administered examination (SAE). This study aims to compare the diagnostic accuracy of a patient SAE to a traditional standardised clinical examination (SCE) for evaluation of femoroacetabular impingement syndrome (FAIS).

Methods

75 patients seeking care for hip-related pain were included for participation. All patients underwent both SAE and SCE and were randomised to the order of the examinations. Diagnostic accuracy statistics were calculated for both examination group for a final diagnosis of FAIS. Mean diagnostic accuracy results for each group were then compared using Mann-Whitney U non-parametric tests.

Results

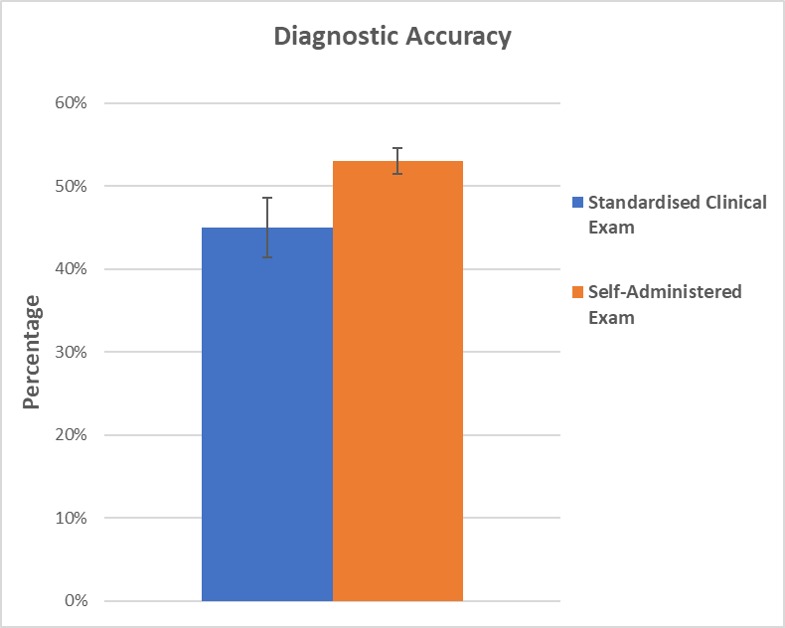

The diagnostic accuracy of individual SAE and SCE manoeuvres varied widely. Both SAE and SCE demonstrated no to moderate change in post-test probability for the diagnosis of FAIS. Although low, SAE demonstrated a statistically greater mean diagnostic accuracy compared with the SCE (53.6% vs 45.5%, p=0.02).

Conclusion

Diagnostic accuracy was statistically significantly higher for the self-exam than for the traditional clinical exam although the difference may not be clinically relevant. Although the mean accuracy remains relatively low for both exams, these values are consistent with hip exam for FAIS reported in the literature. Having established the validity of an SAE, future investigations will need to evaluate implementation in a telehealth setting.

Keywords: femoroacetabular impingement syndrome, telehealth, diagnostic accuracy

What are the new findings?

A patient’s self-performed examination was more accurate for the diagnosis of femoroacetabular impingement syndrome than a traditional examination performed by a clinician.

How might it impact on clinical practice in the near future?

These data establish the validity of a patient’s self-performed examination that may be implemented into a telehealth model to help improve early diagnosis of hip pathology and streamline access to care.

Introduction

Telehealth has become an increasing subject of study due to the potential for providing equitable access to care1–3 and improving triage to the appropriate providers.4 5 The integration of telehealth into clinical practice may also have economic benefits, contributing to improved costs of care.5 The clinical exam provides key diagnostic information to support accurate diagnosis and decision-making in musculoskeletal care. Effective and comprehensive telehealth approaches to musculoskeletal care must evaluate the marginal impact on diagnostic accuracy of and/or reproduce this element of the evaluation approach. A patient-performed screening physical examination may offer a solution; however, the diagnostic utility of such an examination must first be evaluated.

Although the number of arthroscopic hip surgeries for intra-articular pathology continues to increase, accurate diagnosis of patients with hip pain remains a diagnostic challenge.6 7 Increasing focus has been placed on the role of clinical examination in the differential diagnosis of intra-articular and periarticular sources of hip pain.6 8 9 This is of particular interest given variability in the diagnostic accuracy of radiographic testing10–13 and the associated costs and barriers in access associated with such studies.

The primary objective of this study is to measure the diagnostic accuracy of a patient self-administered examination (SAE) of the hip versus a traditional standardised clinical examination (SCE) for diagnosis of femoroacetabular impingement syndrome (FAIS). A secondary objective was to evaluate the individual diagnostic accuracy metrics of both forms of examination and evaluate their influence of post-test probability of FAIS. FAIS was selected because of its relatively high prevalence, increasing diagnosis and surgical prevalence, and questionable examination utility in comparison to reference imaging. We hypothesised that there would be no difference in diagnostic accuracy between the patient-administered SAE and the clinician-performed SCE.

Methods

Study design

This was a prospective, case-based, case–control study design. The Standard for Reporting Diagnostic Accuracy guidelines were used in development of the methodology.

Participants

Following institutional review board approval, 80 patients seeking care from a fellowship-trained hip arthroscopy specialist for hip-related pain or mechanical symptoms were recruited for participation in an outpatient clinical setting. Consecutive patients were identified in an outpatient clinic of a tier-one institution from July 2017 until March 2018. Five patients were unable to complete the entire examination due to time constraints. The final number of participating subjects was 75. Testing was performed in the same outpatient clinical setting for all subjects. All patients underwent both SAE and SCE and were randomised to the order of the examinations.

Inclusion criteria

Ages 18–80 years; seeking care for hip-related pain and/or clicking, catching, giving way or stiffness, able to sign or verbalise study consent, without confounding medical conditions (eg, gynaecological or urinary pathology) and English speaking were approached for inclusion. No subjects declined.

Exclusion criteria

Patients with known lumbar spine or sacroiliac pathology, previous hip surgery, previous hip injury that would normally exclude from examination as standard practice, or inability to sign or verbalise consent were excluded.

Index tests

Subjective patient history

Based on a review of the literature for subjective findings associated with periarticular and intra-articular hip pathology the following subjective patient history items were collected prior to patient testing: location of pain included groin versus lateral hip,14–18 difficulty with stairs,19 20 pain with placing or removing shoes in a sitting position,21 pain with sleeping on one’s side, stiffness in the morning, pain in the morning, pain with sitting and ‘catching’ or ‘clicking’ in the hip.

Patient SAE

A review of the literature was performed to identify a series of self-performed manoeuvres associated with periarticular and intra-articular hip pathology (see table 1 for further details).21–25 Subjects met with the instructing provider in a private clinical exam room. The instructing provider was blinded to the final diagnosis. Reproduction of concordant pain (ie, pain consistent with that typically experienced by the patient) was considered a positive result for SAE manoeuvres.

Table 1.

Self-administered examination (SAE)

| Examination manoeuvre | Description | Positive test |

| Trochanteric palpation22 23 | Patient instructed to lie on the side with symptomatic leg facing the ceiling, hips flexed to 60° and knees held together. Patient then instructed to palpate lateral hip for tenderness. |

|

| Restricted range of motion (ROM)—hip rotation | Patient instructed to sit in chair with hip flexed to 90°. Active internal and external rotation performed to end point and held for 5 s. |

|

| Restricted ROM—supine hip flexion | Patient instructed to lie supine with hips flexed. Knees are brought directly in line with the shoulders and then brought outside of the shoulders. |

|

| Flexion abduction external rotation (FABER)21 | The lateral malleolus of the symptomatic leg is placed above the patella of the contralateral leg. The pelvis is maintained level and parallel to the bed. The bent knee is allowed to fall towards the bed without moving the pelvis. |

|

| Bilateral bent knee fallout | Lying flat on the back with both knees bent and feet flat on the floor. Both knees are gradually allowed to fall to the outside with the feet maintained on the floor. |

|

| Bilateral resisted hip adduction37 | Sitting in a chair, subject is instructed to place one fist between the knees. They then apply as much force as possible for up to 5 s. |

|

| Sitting hip abduction | Sitting in a chair with knees together, a belt is placed around both knees. The subject attempts to push the knees apart with as much force as possible for up to 5 s. |

|

| Single-leg stance25 | Standing next to a wall, the contralateral hand is used for balance. The asymptomatic foot is raised until the thigh is parallel to the floor. This position is held for up to 30 s. |

|

| Three-way squat |

|

|

| Single-leg squat | Standing on one leg while holding a stationary surface for balance, subject slowing squats as far as possible. |

|

Standardised clinical examination

A literature review was performed to identify a series of clinician-performed examination manoeuvres to develop the SCE (see table 2 for further details).6 15 21 24–26 This standardised examination protocol was conducted by a different provider from the SAE. The examination included tests of passive range of motion and specialised provocative manoeuvres (eg, flexion adduction internal rotation (FADIR)) to assess for intra-articular pathology (table 2). Providers performing the SCE were blinded to the administration and findings of the SAE and vice versa.

Table 2.

Standardised clinical examination (SCE)

| Examination manoeuvre | Description | Positive test |

| Restricted passive range of motion (ROM) | With patient supine, each hip is passively raised into end-range flexion. From that position, the hip is rotated internally and externally to end range. The hip is passively placed into end-range extension. |

|

| Flexion abduction external rotation (FABER)21 | With patient supine, the provider places the heel of the examined leg over the opposite knee. The hip is passively externally rotated and abducted via pressure on the knee. |

|

| Resisted supine hip abduction6 | With patient supine, the leg is placed in neutral abduction. The patient is asked to push the leg into abduction with as much force as possible for up to 5 s. |

|

| Resisted hip adduction24 | With patient supine, clinician places forearm between bilateral knees. Patient squeezes the clinician forearm with as much force as possible for up to 5 s. |

|

| Resisted external derotation test25 | With patient supine, the hip is flexed to 90° and externally rotated. The patient attempts to return leg to neutral rotation against resistance. |

|

| Flexion adduction internal rotation (FADIR)6 | With patient supine, the hip is flexed to 90°. Adduction and internal rotation of the hip is applied. |

|

| Thomas test15 | With the patient supine and the contralateral hip maximally flexed, the clinician passively extends the symptomatic hip. |

|

| Log roll test38 | With the patient supine and hip in neutral flexion and abduction, the lower extremity is passively rolled into maximal internal and external rotation. |

|

Reference standards

A diagnosis of FAIS was defined according to the Warwick Agreement which includes the presence of hip pain, clicking, catching or stiffness which is reproduced with impingement testing in the presence of cam or pincer morphology on plain radiographs in the absence of radiographic osteoarthritis (Tonnis grade 0 or 1).27 A diagnosis of osteoarthritis was defined as the presence of hip pain, clicking, catching or stiffness in the presence of radiograph findings of joint space narrowing, osteophyte formation and/or subchondral sclerosis/cyst formation (Tonnis grade 2 or 3). A diagnosis of trochanteric bursitis was defined as primary pain localised to the lateral hip, over the greater trochanter and reproduced with palpation.

Power analysis

The study is powered for the primary objective of the study, which is to measure the diagnostic accuracy of a patient-performed clinical examination versus a standard clinical examination. We powered the study by expected cell frequencies for those with and without an intra-articular disorder. Our previous works28 have shown a higher percentage of ‘True Positives (TP)’ for the intra-articular group (than false negatives (FN)) and we hypothesise a slightly higher percentage of true negatives (TN) than false positives (FP). With a projection of the following proportions, TP=47%, FN=20%, FP=13% and TN=20%, we would require a sample size of 75 to meet statistical significance.

Statistical analysis

Analysis was performed using SPSS (IBM V25.0). Diagnostic accuracy measures of sensitivity (SN), specificity (SP), positive likelihood ratio (LR+), negative likelihood ratio (LR−) and post-test probabilities were calculated for each component of the SAE and SCE.

SN was defined as the ability of the test to identify a positive finding when the targeted diagnosis is present, that is, TP. SP was defined as the ability of the test to identify a negative finding when the targeted is negative, that is, TN. LR+ indicates a shift in probability favouring the existence of a disorder if the test is found to be positive. Value greater than 1 indicates greater diagnostic strength. LR− indicates a shift in probability favouring the absence of a disorder if the test is found to be negative. Value less than 1 indicates better ability to determine a negative result. Post-test probability indicates a shift in the probability of the condition being present or absent relative to the pretest prevalence.

Diagnostic accuracy ((TP+TN)/(TP+TN+FP+FN)×100) for each examination was calculated and pooled for the SAE and SCE. Mean diagnostic accuracy was then compared using a Mann-Whitney U non-parametric test. A Mann-Whitney U test is the non-parametric alternative equivalent to a t-test but is a more conservative measure that does not require the same assumptions as a parametric test of differentiation. A statistically significant finding was defined as p<0.05.

Missing data

Complete data were available in 97.6% of test items. In total, 92.5% of the individuals had complete cases. Because the missing values were limited and consisted primarily of categorical values, SPSS was instructed to skip missing values during statistical analysis, despite values being missing at random.

Patient and Public Involvement

The development of the above described methods was designed to cause the least possible amount of disruption to the patient’s clinical experience. Although patients were not directly involved in the development of the study protocol, outcome measures were developed based on the patients’ subjective experience. The results of the present study will be disseminated to patients to whom Telehealth care is offered as deemed appropriate in the clinical setting.

Complete data were available in 97.6% of test items. In total, 92.5% of the individuals had complete cases. Because the missing values were limited and consisted primarily of categorical values, SPSS was instructed to skip missing values during statistical analysis, despite values being missing at random.

Results

For the 75 included patients, mean age was 45 (range 18–77) with mean body mass index of 28 (range 17–68). Regarding self-reported gender, subjects were 67% female, 33% male. Regarding self-reported racial identity, subjects were 73% White/Caucasian, 13% Black/African-American, 3% Asian/Native Pacific Islander with 9% declining to report. Regarding self-reported ethnicity, subjects were 88% non-Hispanic/Latino, 1.5% Hispanic/Latino with 11% declining to report.

Online supplementary appendix 1 outlines the SN, SP, positive and negative predictive values, LRs and accuracy values of the SAE and SCE. In general, the CIs of the LRs were wide for each of the tests, with a majority crossing 1.0. A number of the tests had diagnostic accuracy results below 50%. The FADIR test had an overall accuracy of 70.11% and demonstrated statistically significant increases and decreases in post-test probability. Pain with palpation of the lateral hip was also statistically significant and had an overall accuracy of 64.37%. The largest change in post-test probability for a statistically significant test involved the FADIR test, with a negative finding decreasing post-test probability by 30%.

bmjsem-2019-000574supp001.pdf (72.8KB, pdf)

SAE demonstrated a statistically greater mean diagnostic accuracy compared with the SCE (53.6% vs 45.5%, p=0.02) (figure 1). The diagnostic accuracy of individual SAE manoeuvres varied widely.

Figure 1.

Comparison of the two testing formats demonstrated a significantly higher diagnostic accuracy for the self-administered examination (53%±1.6%) versus the standardised clinical exam (45%±3.6%). P=0.02.

Discussion

The present investigation demonstrated three notable findings which we believe merit explanation and further study. First, the diagnostic accuracy of a patient SAE for FAIS was statistically higher than that of a traditional clinician-performed examination. Second, neither examination protocol demonstrated a strong diagnostic accuracy or influenced post-test probability of diagnosis for FAIS in an outpatient orthopaedic surgery clinic. Third, the results of the SAE may be transferrable to a telehealth setting; however, further investigation is needed first.

Previous investigations have evaluated the diagnostic accuracy of physical examination for intra-articular hip pathology. Notably, in a meta-analysis of 21 studies evaluating the diagnostic accuracy of physical examination for FAIS, Reiman et al demonstrated minimal increase in post-test probabilities for physician-performed physical examination.28 An earlier systematic review performed by Tijssen et al also illustrates the diagnostic complexity of FAIS, ultimately finding none of the examination manoeuvres evaluated to be reliable for confirmation or disagreement with diagnosis.29 These findings may be related to the practice setting in which these examinations are performed. Once a patient has been referred to the outpatient clinic of a hip arthroscopy specialist, there is a high potential for verification bias by the provider which may dampen the effect of physical exam on final diagnosis.

The difficulty with consistent diagnosis of FAIS may relate to the relative heterogeneity of the condition. As a syndrome with multiple described subtypes (ie, cam, pincer, mixed), a large variety of patients with potentially very different presentations may fall under the diagnostic umbrella of FAIS. This may be reflected in the heterogeneity of the present study’s findings. Several examination manoeuvres when evaluated individually did demonstrate an improvement in post-test probability; however, this effect was diminished when the results were pooled. Given these findings, further evaluation of specific clusters of exam manoeuvres is merited to potentially elucidate the most reproducibly accurate tests for diagnosing providers. A cluster analysis also can further narrow the number of self-exam manoeuvres to improve the ease of implementation and evaluate how these manoeuvres relate to the different subtypes of FAIS.

In addition to further cluster analysis, future directions will analyse the effect of intra-articular injection on the predictive value of our examination protocols. A recently published investigation demonstrated that in situations of low disease prevalence and low examination sensitivity, diagnostic injection was more beneficial than advanced imaging.30 Further economic and decision model analysis is merited to determine the optimum combination of examination manoeuvres and diagnostic injection in the diagnosis of FAIS. This line of study will be further expanded to evaluate the effect of these diagnostic measures on the ultimate decision to proceed with surgical intervention.

Given the ever-expanding population and the physical limitations of providers, telehealth represents an opportunity to expand access to care and facilitate appropriate triage of patients. In concept, telehealth has shown increasing acceptance among providers and patients. A recent cross-sectional analysis of patient satisfaction for 3303 individuals demonstrated that the majority of patients were very satisfied with their telehealth experience.31 It should be noted that the cost-effectiveness of telehealth remains controversial, with several investigations demonstrating a lack of cost savings compared with traditional care.32 33 Notably, those controversies appear to be most prevalent with regard to treatment of long-term or chronic conditions. In the orthopaedic setting, telehealth application has been associated with reduction of cost, time and hospital visits following major joint arthroplasty34; however, the capacity for accurate diagnosis remains controversial.35 36

At this time, further investigation is merited into the effect of telehealth on utilisation and cost in the more acute orthopaedic setting. We envision a two-phase approach with the first phase being to assess accuracy of both the clinician-administered and patient-administered exam and the second to evaluate implementation of the SAE in a telehealth setting. Important questions include when and how the patient should perform the exam as well as the accuracy in practice. The present study satisfies phase 1 by establishing a proof of concept for a patient-performed examination to diagnose FAIS. The above stated future directions of study may help establish a feasible set of examination manoeuvres that may be performed remotely by patients with hip pain via a telehealth model.

Limitations

As discussed above, neither SAE nor SCE demonstrated a strong influence on the post-test probability of FAIS diagnosis. Within each group, there was a large degree of variability with regard to accuracy measures evaluated. This may relate to the high degree of variability among patients with a diagnosis of FAIS. For the present investigation, the reference standard for evaluation of accuracy was clinical diagnosis of FAIS based on interpretation of radiographs and clinical impression. Although the Warwick Agreement on femoroacetabular impingement27 was used as a guideline for this reference, this method introduces an element of potential bias. Finally, the demographics of the included subjects are not representative of the larger population, potentially limiting our ability to generalise the results of the present study. Having established the proof of concept, future study directions will include cluster analysis of specific sets of examination manoeuvres to evaluate for high-performing tests to be used in clinical practice.

Conclusion

A patient SAE for FAIS demonstrated higher pooled diagnostic accuracy than a traditionally performed provider examination. Having established a proof of concept, future directions will investigate potential implementation of patient self-examination in a telehealth model.

Footnotes

Contributors: All listed authors were integral to the planning, execution, writing and revision of the present study. All coauthors contributed substantially to the study design, acquisition, analysis and/or interpretation of data. Final approval of the submitted manuscript was obtained from all coauthors.

Funding: The authors have not declared a specific grant for this research from any funding agency in the public, commercial or not-for-profit sectors.

Competing interests: None declared.

Patient consent for publication: Not required.

Ethics approval: Institutional review board approval was obtained prior to initiation of this study.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

Data availability statement: All data relevant to the study are included in the article or uploaded as supplementary information.

References

- 1.Russell TG. Physical rehabilitation using telemedicine. J Telemed Telecare 2007;13:217–20. 10.1258/135763307781458886 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Currell R, Urquhart C, Wainwright P. Lewis R: telemedicine versus face to face patient care: effects on professional practice and health care outcomes. Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews 2000;2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Haukipuro K, Ohinmaa A, Winblad I, et al. The feasibility of telemedicine for orthopaedic outpatient clinicsa randomized controlled trial. J Telemed Telecare 2000;6:193–8. 10.1258/1357633001935347 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Wallace P, Haines A, Harrison R, et al. Joint teleconsultations (virtual outreach) versus standard outpatient appointments for patients referred by their general practitioner for a specialist opinion: a randomised trial. The Lancet 2002;359:1961–8. 10.1016/S0140-6736(02)08828-1 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Wallace P, Haines A, Harrison R, et al. Design and performance of a multi-centre randomised controlled trial and economic evaluation of joint tele-consultations [ISRCTN54264250]. BMC Fam Pract 2002;3:1 10.1186/1471-2296-3-1 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Reiman MP, Goode AP, Hegedus EJ, et al. Diagnostic accuracy of clinical tests of the hip: a systematic review with meta-analysis. Br J Sports Med 2013;47:893–902. 10.1136/bjsports-2012-091035 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Colvin AC, Harrast J. Harner C: trends in hip arthroscopy. J Bone Joint Surg Am 2012;94:e23. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Byrd JWT, Jones KS. Diagnostic accuracy of clinical assessment, magnetic resonance imaging, magnetic resonance arthrography, and intra-articular injection in hip arthroscopy patients. Am J Sports Med 2004;32:1668–74. 10.1177/0363546504266480 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Tibor LM, Sekiya JK. Differential diagnosis of pain around the hip joint. Arthroscopy: The Journal of Arthroscopic & Related Surgery 2008;24:1407–21. 10.1016/j.arthro.2008.06.019 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Smith TO, Hilton G, Toms AP, et al. The diagnostic accuracy of acetabular labral tears using magnetic resonance imaging and magnetic resonance arthrography: a meta-analysis. European Radiology 2010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Smith TO, Simpson M, Ejindu V, et al. The diagnostic test accuracy of magnetic resonance imaging, magnetic resonance arthrography and computer tomography in the detection of chondral lesions of the hip. Eur J Orthop Surg Traumatol 2013;23:335–44. 10.1007/s00590-012-0972-5 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Reichenbach S, Leunig M, Werlen S, et al. Association between cam-type deformities and magnetic resonance imaging-detected structural hip damage: a cross-sectional study in young men. Arthritis & Rheumatism 2011;63:4023–30. 10.1002/art.30589 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Reichenbach S, Jüni P, Werlen S, et al. Prevalence of cam-type deformity on hip magnetic resonance imaging in young males: a cross-sectional study. Arthritis Care Res 2010;62:1319–27. 10.1002/acr.20198 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Groh MM, Herrera J. A comprehensive review of hip labral tears. Curr Rev Musculoskelet Med 2009;2:105–17. 10.1007/s12178-009-9052-9 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.McCarthy JC, Busconi B. The role of hip arthroscopy in the diagnosis and treatment of hip disease. Orthopedics 1995;18:753–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Keeney JA, Peelle MW, Jackson J, et al. Magnetic resonance arthrography versus arthroscopy in the evaluation of articular hip pathology. Clin Orthop Relat Res 2004;429:163–9. 10.1097/01.blo.0000150125.34906.7d [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Vendittoli PA, Young DA, Stitson DJ, et al. Acetabular rim lesions: arthroscopic assessment and clinical relevance. Int Orthop 2012;36:2235–41. 10.1007/s00264-012-1595-5 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Burnett RSJ, Della Rocca GJ, Prather H, et al. Clinical presentation of patients with tears of the acetabular labrum. J Bone Joint Surg Am 2006;88:1448–57. 10.2106/JBJS.D.02806 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Clohisy JC, Baca G, Beaule PE, et al. Descriptive epidemiology of femoroacetabular impingement: a North American cohort of patients undergoing surgery. Am J Sports Med 2013;41:1348–56. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Clohisy JC, Knaus ER, Hunt DM, et al. Clinical presentation of patients with symptomatic anterior hip impingement. Clin Orthop Relat Res 2009;467:638–44. 10.1007/s11999-008-0680-y [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Fearon AM, Scarvell JM, Neeman T, et al. Greater trochanteric pain syndrome: defining the clinical syndrome. Br J Sports Med 2013;47:649–53. 10.1136/bjsports-2012-091565 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Falvey EC, Franklyn-Miller A, McCrory PR. The greater trochanter triangle; a pathoanatomic approach to the diagnosis of chronic, proximal, lateral, lower pain in athletes. Br J Sports Med 2009;43:146–52. 10.1136/bjsm.2007.042325 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Grimaldi A, Mellor R, Nicolson P, et al. Utility of clinical tests to diagnose MRI-confirmed gluteal tendinopathy in patients presenting with lateral hip pain. Br J Sports Med 2017;51:519–24. 10.1136/bjsports-2016-096175 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Thorborg K, Branci S, Nielsen MP, et al. Holmich P: Copenhagen five-second squeeze: a valid indicator of sports-related hip and groin function. British Journal of Sports Medicine 2016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Lequesne M, Mathieu P, Vuillemin-Bodaghi V, et al. Gluteal tendinopathy in refractory greater trochanter pain syndrome: diagnostic value of two clinical tests. Arthritis Rheum 2008;59:241–6. 10.1002/art.23354 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Martin RL, Enseki KR, Draovitch P, et al. Acetabular labral tears of the hip: examination and diagnostic challenges. J Orthop Sports Phys Ther 2006;36:503–15. 10.2519/jospt.2006.2135 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Griffin DR, Dickenson EJ, O'Donnell J, et al. The Warwick agreement on femoroacetabular impingement syndrome (FAI syndrome): an international consensus statement. Br J Sports Med 2016;50:1169–76. 10.1136/bjsports-2016-096743 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Reiman MP, Goode AP, Cook CE, et al. Diagnostic accuracy of clinical tests for the diagnosis of hip femoroacetabular impingement/labral tear: a systematic review with meta-analysis. Br J Sports Med 2015;49:811 10.1136/bjsports-2014-094302 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Tijssen M, van Cingel R, Willemsen L, et al. Diagnostics of femoroacetabular impingement and Labral pathology of the hip: a systematic review of the accuracy and validity of physical tests. Arthroscopy: The Journal of Arthroscopic & Related Surgery 2012;28:860–71. 10.1016/j.arthro.2011.12.004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Cunningham DJ, Paranjape CS, Harris JD, et al. Advanced imaging adds little value in the diagnosis of femoroacetabular impingement syndrome. The Journal of Bone and Joint Surgery 2017;99:e133 10.2106/JBJS.16.00963 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Polinski JM, Barker T, Gagliano N, et al. Patients’ Satisfaction with and Preference for Telehealth Visits. J Gen Intern Med 2016;31:269–75. 10.1007/s11606-015-3489-x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Henderson C, Knapp M, Fernandez J-L, et al. Cost effectiveness of telehealth for patients with long term conditions (whole systems Demonstrator telehealth questionnaire study): nested economic evaluation in a pragmatic, cluster randomised controlled trial. BMJ 2013;346:f1035 10.1136/bmj.f1035 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Henderson C, Knapp M, Fernández J-L, et al. Cost-Effectiveness of telecare for people with social care needs: the whole systems Demonstrator cluster randomised trial. Age Ageing 2014;43:794–800. 10.1093/ageing/afu067 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Koutras C, Bitsaki M, Koutras G, et al. Socioeconomic impact of e-health services in major joint replacement: a scoping review. THC 2015;23:809–17. 10.3233/THC-151036 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Chandhanayingyong C, Tangtrakulwanich B, Kiriratnikom T. Teleconsultation for emergency orthopaedic patients using the multimedia messaging service via mobile phones. J Telemed Telecare 2007;13:193–6. 10.1258/135763307780908049 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Elkaim M, Rogier A, Langlois J, et al. Teleconsultation using multimedia messaging service for management plan in pediatric orthopaedics: a pilot study. Journal of Pediatric Orthopaedics 2010;30:296–300. 10.1097/BPO.0b013e3181d35b10 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Thorborg K, Branci S, Nielsen MP, et al. Copenhagen five-second squeeze: a valid indicator of sports-related hip and groin function. Br J Sports Med 2017;51:594–9. 10.1136/bjsports-2016-096675 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Martin RL, Sekiya JK. The interrater reliability of 4 clinical tests used to assess individuals with musculoskeletal hip pain. J Orthop Sports Phys Ther 2008;38:71–7. 10.2519/jospt.2008.2677 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

bmjsem-2019-000574supp001.pdf (72.8KB, pdf)