Abstract

Introduction

Pulmonary embolism poses one of the most challenging diagnoses in medicine. Resolving these diagnostic difficulties is more crucial in emergency departments where fast and accurate decisions are needed for a life-saving purpose. Here, clinical pretest evaluation is an important step in the diagnostic algorithm of pulmonary embolism. Although clinical probability scores are widely used in emergency departments of sub-Saharan Africa, no study has cited their diagnostic performance in this resource-constrained environment. This study will seek to assess the performance of four routinely used clinical prediction models in Cameroonians presenting with suspicion of pulmonary embolism at the emergency department.

Methods and analysis

It will be a cross-sectional study comparing the sensitivity, specificity, positive and negative predictive values and accuracy of the Wells, Simplified Wells, Revised Geneva and the Simplified Revised Geneva Scores to CT pulmonary angiography as gold standard in all consecutive consenting patients aged above 15 years admitted for clinical suspicion of pulmonary embolism to the emergency departments of seven major referral hospitals of Cameroon between 1 July 2019 and 31 December 2020. The area under the receiver operating curve, calibration plots, Hosmer and Lemeshow statistics, observed/expected event rates, net benefit and decision curve will be measured of each the clinical prediction test to ascertain the clinical score with the best diagnostic performance.

Ethics and dissemination

Clearance has been obtained from the Institutional Review Board of the Faculty of medicine and biomedical sciences of the University of Yaounde I, Cameroon and the directorates of all participating hospitals to conduct this study. Also, informed consent will be sought from each patient or their legal next of kin and parents for minors, before enrolment into this study. The final study will be published in a peer-review journal and the findings presented to health authorities and healthcare providers.

Keywords: pulmonary embolism, wells score, simplified wells score, revised geneva score, simplified revised geneva score, emergency department, African

Strengths and limitations of this study.

This is the first study to assess the diagnostic performance of four routine clinical probability scores (CPSs) for pulmonary embolism (PE) in sub-Saharan Africa, hence, may provide an insight on the CPS with the best diagnostic performance.

Bias will be reduced by filling all the CPS before the conduct of a CT pulmonary angiography (CTPA), as well as blinding the results of CPS to the radiologists performing the CTPA.

Robust statistical methods like the area under the receiver operating curve will be used to ascertain the test with the best diagnostic performance.

Its main limitation is the inability to objectively assess the expertise of radiologists who will interpret the CTPA results, which is a paramount determinant of the amount of confirmed PE cases.

Another drawback is the exclusion of D-dimer measurements which are of great significance in the risk stratification of PE.

Background

Pulmonary embolism (PE) is a potentially lethal sequela of venous thromboembolism (VTE) with a reported 30-day mortality rate varying between 14% and 44%.1–4 It poses considerable diagnostic difficulties in clinical practice and especially in emergency medicine, due to the polymorphism of its clinical manifestations and the lack of a pathognomic symptom or sign.5 Hence, it is common for the diagnosis of PE to be easily overlooked6 7 till necropsy where it has been reported in 53% of the dead people who had an autopsy.8 Consequently, clinicians have developed a high index of clinical suspicion of PE over the last decade.9 However, of all suspected PE patients, only 10%–15% would be confirmed during the diagnostic tests.10 Overtesting leads to undue expenses, potential iatrogenic damages, such as contrast-induced allergic reactions, contrast-induced nephropathy11 or radiation-induced solid tumours12 from multidetector CT pulmonary angiography (CTPA), its current gold-standard diagnostic test.13 In an attempt to remedy the problem of undue investigations, several clinical probability scores (CPSs), among which the most widely used are the Wells,14 Simplified Wells,15 Revised Geneva,16 Simplified Revised Geneva (SRG)17 scores and the YEARS clinical decision rule,18 were put forth to guide the choice of diagnostic testing depending on the assessed PE probability (low, intermediate or high).13 Current guidelines recommend their use coupled with D-dimer to preclude patients with a low PE probability from further diagnostic tests, without compromising the patient’s safety.13 This diagnostic algorithm reduces the number of unnecessary CTPA by 35%, with only 1%–2% of missed cases in the group of patients with a low PE probability.19 This is of invaluable economic interest in resource-limited emergency departments (EDs) of sub-Saharan Africa (SSA) where CTPA has recently been described to be financially and geographically inaccessible for the majority of patients with suspected PE.20

Globally, EDs are at the forefront of the management of patients with suspected PE.21 Here, prompt and accurate ruling in or out the diagnosis of PE is vital for the timely diagnosis and treatment of PE. As mentioned above, the diagnosis of PE begins with the risk stratification through CPS to prevent patients with low PE probability from unnecessary further testings.13 21 Although these clinical prediction models have been externally validated in high-income countries where they were designed,22 23 the generalisation of their validity to SSA remains questionable due to lack of data in this regards. It is known that a CPS derived in a particular setting often performs less well when applied in another setting24–27 due to discrepancies in disease prevalence and differences in clinicians’ experiences of suspected cases.24 Thus, generalising the external validity of CPS for PE to SSA without prior evidence is inappropriate given that several studies have showed blacks to have a 30%–60% increase in the incidence of PE,28–30 as well as a 30% increase in PE-related mortality compared with other racial groups.31

Objectives

The study objectives will be to assess the diagnostic performance of the Original Wells, Simplified Wells, Revised Geneva and the SRG scores in a selected SSA population admitted to the ED with clinical suspicion of PE.

Methods and analysis

The final study will be reported in conformity to the Tripod checklist for prediction model validation.

Study design, setting and duration

This will be a cross-sectional multicentre study carried out in the EDs of seven major referral hospitals of Cameroon: the National Emergency Centre of Cameroon, the Gynaeco-obstetric and Paediatric Hospital of Yaoundé, the Yaoundé Central Hospital, the Yaoundé General Hospital, the University Hospital Centre of Yaounde, the Douala General Hospital and the Laquintinie Hospital of Douala between the period of 1 July 2019 and 31 December 2020. The Gynaeco-obstetric and Paediatric Hospital of Yaoundé is specialised in the management of all maternal and child diseases irrespective of the mother’s and child’s age. The other six hospitals are specialised in the management of all adults’ as well of maternal and child diseases, irrespective of the adult’s, mother’s and child’s ages. All seven hospitals are tertiary and university teaching hospitals in the cities of either Yaoundé or Douala of Cameroon. Averagely, each hospital manages 1000 patients per year.

Patient eligibility criteria

We will prospectively recruit all consecutive patients aged above 15 years who will be admitted to the aforementioned seven EDs for clinical suspicion of PE. Pregnant women will also be included. Case definition of clinical suspicion of PE will be any patient presenting with sudden dyspnoea, chest pain, haemoptysis or syncope. We will exclude the patients who will refuse to consent, those who will not undergo CTPA to rule in or rule out PE despite clinical suspicion, patients with contraindications to CTPA (haemodynamic instability, dehydration, altered renal function) and those with a diagnosis of PE documented before ED admission.

Sampling method

Assuming a prevalence rate of 61.5% for PE in Africa,32 we used the Eng’s formula33 to obtain a minimum sample size of 364 participants through a consecutive sampling method.

Study procedure

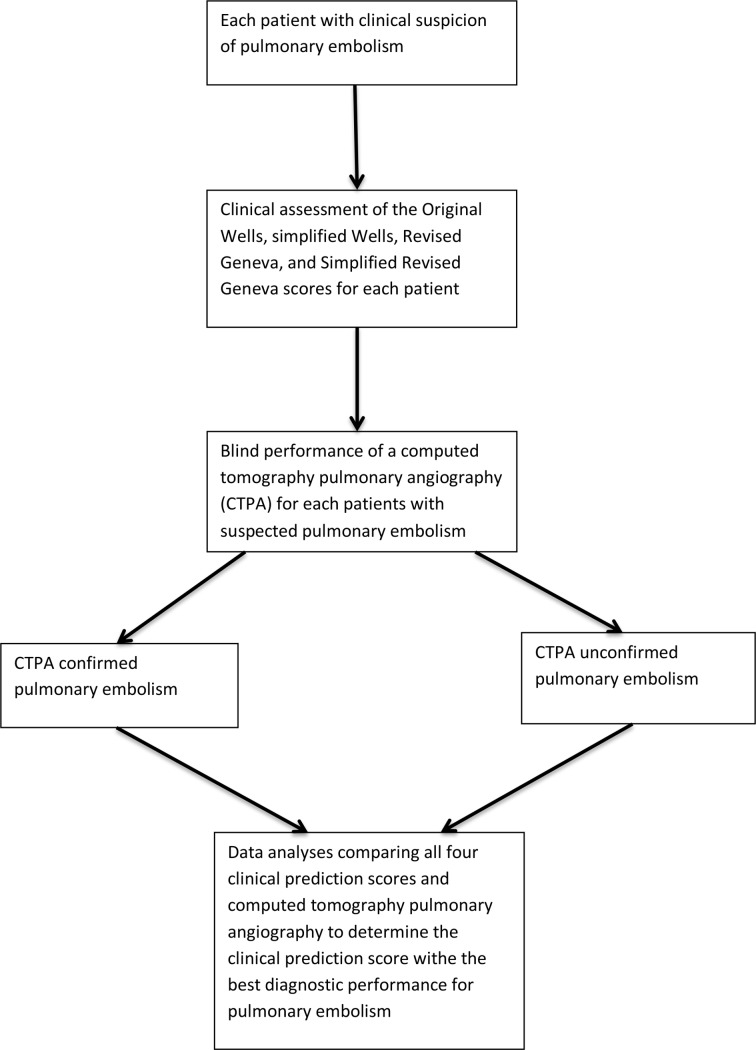

We will approach all consecutive patients admitted for clinical suspicion of PE to obtain informed consent. Using a pilot-tested interview administered questionnaire (online supplementary file 1), each enrolled patient will be assessed for PE clinically probability before any other test to avoid bias, using four CPS, namely; the original Wells score, the simplified Wells score, the Revised Geneva score and the SRG score. The YEARS clinical rule, a CPS, will not be studied because it entails the measurement of D-dimers, which is relatively expensive and not available in all SSA laboratories.18 Figure 1 illustrates the study procedure.

Figure 1.

A flow chart illustrating the study procedure.

bmjopen-2019-031322supp001.pdf (103.6KB, pdf)

Definitions of terms

Patients will be considered to have chronic heart failure, cancer, history of previous deep venous thrombosis or PE or chronic pulmonary disease if these conditions will be known before ED admission. Recent surgery will be defined as any surgical intervention performed within the last 4 weeks before the patient’s admission.

Diagnostic testing and assessment of potential sources of bias

The questionnaire will be filled and systematically reviewed for completeness before proceeding to further diagnostic testing. After assessment of the clinical prediction of PE, all patients with none of the aforementioned contraindications to CTPA will undergo a CTPA to either rule in or rule out the diagnosis of PE. The diagnosis of PE will be established by the CTPA detection of an embolus in the pulmonary vasculature. Radiologists performing the CTPA will have a minimum of 10 years of clinical experience after qualifying to reduce the chances of the radiologists missing out the diagnosis of PE. The results of the CPS will be blinded to the radiologist to decrease the bias.

Data management and analysis

Using CTPA as the goal standard test, the sensitivity, specificity, positive predictive value, negative predictive value and accuracy of each CPS will be calculated. The sensitivity of each CPS will be calculated as the proportion of patients with CTPA confirmed PE who will have a PE likely probability. The specificity of each of the four CPS will be calculated as the proportion of patients with CTPA unconfirmed PE who will have a PE unlikely score. The positive predictive value will be calculated as the proportion of patients with PE likely score who will have CTPA confirmed PE. The negative predictive value of each CPS will be calculated as the proportion of patients with PE unlikely score who will have a CTPA unconfirmed PE. The accuracy of each CPS will be calculated as the proportion of true results (true positives and true negatives) or the number of correct clinical assessments divided by the number of all assessments. Data will be entered into the SPSS V.20.0 for analysis. Measures of discrimination, such as the area under the curve (AUC) and measures of calibration (calibration plots, Hosmer and Lemeshow statistics, observed/expected event rates, etc), would be used to better ascertain the performance of each CPS. Other analyses, such as the net benefit or decision curve, would also be measured. To ease analysis the predictive models were dichotomised as follows: Original Wells scores between 0–4 and >4 will be considered PE unlikely and PE likely, respectively (table 1); Simplified Wells scores between ≤1 and >1 will be considered as PE unlikely and PE likely, respectively (table 1); Revised Geneva scores between 0–5 and ≥6 will be considered PE unlikely and PE likely, respectively (table 2) and SRG scores between 0–2 and ≥3 will be considered PE unlikely and PE likely, respectively (table 2).

Table 1.

The Original Wells score and Simplified Wells score for PE

| Predictive variables | Original Wells score | Simplified Wells score |

| Previous PE or DVT | 1.5 | 1 |

| Heart rate >100 bpm | 1.5 | 1 |

| Recent surgery or immobilisation | 1.5 | 1 |

| Clinical signs of DVT | 3 | 1 |

| Alternative diagnosis less likely than PE | 3 | 1 |

| Haemoptysis | 1 | 1 |

| Cancer | 1 | 1 |

| Pretest probability | Pretest probability | |

| 0–1: low | ≤1: PE unlikely (low) | |

| 2–6: moderate | >1: PE likely (high) | |

| ≥7: high | ||

| Dichotomised score | ||

| ≤4: PE unlikely (low) | ||

| >4: PE likely (high) |

DVT, deep venous thrombosis; PE, pulmonary embolism.

Table 2.

The Revised Geneva score and Simplified Revised Geneva score for PE

| Predictive variables | Revised Geneva score | Simplified Revised Geneva score |

| Age >65 years | 1 | 1 |

| Active malignancy (or considered cure <1 year) | 2 | 1 |

| Recent surgery or fracture of the lower limbs within 1 month | 2 | 1 |

| Previous PE or DVT | 3 | 1 |

| Haemoptysis | 2 | 1 |

| Unilateral lower limb pain | 3 | 1 |

| Tenderness on lower limb deep venous palpation and unilateral oedema | 4 | 1 |

| Heart rate | ||

| 75–94 bpm | 3 | 1 |

| ≥95 bpm | 5 | 2 |

| Pretest probability | Pretest probability | |

| 0–3: low | 0–1: low | |

| 4–10: moderate | 2–4: moderate | |

| ≥11: high | ≥5: high | |

| Dichotomised score | Dichotomised score | |

| 0–5: PE unlikely (low) | 0–2: PE unlikely (low) | |

| ≥6: PE likely (high) | ≥3: PE likely (high) |

DVT, deep venous thrombosis; PE, pulmonary embolism.

Patient and public involvement

Data will be collected directly from patients during the conduction of the study. The findings of this study will be presented at conferences, to relevant health authorities and will be published in a biomedical peer-reviewed journal.

Ethics and dissemination

Also, informed consent will be sought from each patient or their legal next of kin and parental consent will be obtained for all minors. The final study will be published in a peer-review journal and the findings presented to health authorities and the healthcare providers.

Discussion

PE is the most life-threatening complication of VTE. A recent systematic review on the epidemiology of venous thromboembolism in Africa found that the prevalence of PE ranges between 0.14% and 61.5%.32 Furthermore, PE accounts for a mortality rate of 53% of autopsy reports.8 These high prevalence rates and mortality rates of PE reiterates the burden of disease it poses. The ill health related to PE is further aggravated by the significant diagnostic challenge in clinical practice and particularly in emergency medicine, due to its polymorphic clinical presentations and absence of pathognomic clinical signs or symptoms. Hence, it is common for the diagnosis of PE to be easily missed out.6 7 CTPA remains the imaging test to diagnose PE.13 By paradox, the advent of CTPA let to a reduction in the prevalence of PE due to an overdiagnosis of PE as a result of an increased index of clinical suspicion of PE by clinicians.9 However, CTPA is not void of complications. It may lead to contrast medium-induced nephropathy11 or radiation medium-induced solid tumours.12 To advert the sequelae of CTPA, sequential pretest testing using CPS has been introduced. Appropriate use of these CPS obviates the need of CTPA by 20%–30%, with an overall 3-month diagnostic failure rate below 1.5%.18 Although CPS are routinely used in EDs of low-resource settings, few studies have cited their external validity in SSA. We intend to use robust statistical methods with the measurement of discrimination, such as AUC, measures of calibration (calibration plots, Hosmer and Lemeshow statistics, observed/expected event rates, etc), calculation of net benefit or decision curve, which would help ascertain the CPS with the best diagnostic performance for PE among all the four CPS assessed. The findings of this study may guide clinicians in making informed decisions in predicting PE diagnosis and identification of patients at the need of further testings or anticoagulants therapy in resource-challenged environments where CTPA is not always available or affordable to confirm the diagnosis of PE.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

The authors thank all administrative staff of participating hospitals for authorising us to conduct this study.

Footnotes

Contributors: AE and JNT: Study protocol conception, design and manuscript writing. POE, JAMM and JZM: critically revised the manuscript for intellectual content. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Funding: The authors have not declared a specific grant for this research from any funding agency in the public, commercial or not-for-profit sectors.

Competing interests: None declared.

Patient consent for publication: Not required.

Ethics approval: Clearance has been granted by the Institutional Review Board of the Faculty of Medicine and Biomedical Sciences of the University of Yaounde I, Cameroon and the directorates of all participating hospitals to conduct this study.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

References

- 1. Mantilla CB, Horlocker TT, Schroeder DR, et al. Frequency of myocardial infarction, pulmonary embolism, deep venous thrombosis, and death following primary hip or knee arthroplasty. Anesthesiology 2002;96:1140–6. 10.1097/00000542-200205000-00017 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Comfere TB, Sprung J, Case KA, et al. Predictors of mortality following symptomatic pulmonary embolism in patients undergoing noncardiac surgery. Can J Anesth 2007;54:634–41. 10.1007/BF03022957 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Sakon M, Kakkar AK, Ikeda M, et al. Current status of pulmonary embolism in general surgery in Japan. Surg Today 2004;34:805–10. 10.1007/s00595-004-2842-1 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Heit JA, Silverstein MD, Mohr DN, et al. Predictors of survival after deep vein thrombosis and pulmonary embolism: a population-based, cohort study. Arch Intern Med 1999;159:445–53. 10.1001/archinte.159.5.445 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Bĕlohlávek J, Dytrych V, Linhart A. Pulmonary embolism, part I: epidemiology, risk factors and risk stratification, pathophysiology, clinical presentation, diagnosis and nonthrombotic pulmonary embolism. Exp Clin Cardiol 2013;18:129–38. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Barais M, Morio N, Cuzon Breton A, et al. “I Can't Find Anything Wrong: It Must Be a Pulmonary Embolism”: Diagnosing Suspected Pulmonary Embolism in Primary Care, a Qualitative Study. PLoS One 2014;9:e98112 10.1371/journal.pone.0098112 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Schiff GD, Hasan O, Kim S, et al. Diagnostic error in medicine: analysis of 583 physician-reported errors. Arch Intern Med 2009;169:1881–7. 10.1001/archinternmed.2009.333 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Lindblad B, Eriksson A, Bergqvist D. Autopsy-Verified pulmonary embolism in a surgical department: analysis of the period from 1951 to 1988. Br J Surg 1991:1849–52. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Wiener RS, Schwartz LM, Woloshin S. Time trends in pulmonary embolism in the United States: evidence of overdiagnosis. Arch Intern Med 2011;171:831–7. 10.1001/archinternmed.2011.178 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Le Gal G, Bounameaux H. Diagnosing pulmonary embolism: running after the decreasing prevalence of cases among suspected patients. J Thromb Haemost 2004;2:1244–6. 10.1111/j.1538-7836.2004.00795.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Mitchell AM, Kline JA. Contrast nephropathy following computed tomography angiography of the chest for pulmonary embolism in the emergency department. J Thromb Haemost 2007;5:50–4. 10.1111/j.1538-7836.2006.02251.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Cochran ST, Bomyea K, Sayre JW. Trends in adverse events after IV administration of contrast media. American Journal of Roentgenology 2001;176:1385–8. 10.2214/ajr.176.6.1761385 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Konstantinides SV, Torbicki A, Agnelli G, et al. 2014 ESC Guidelines on the diagnosis and management of acute pulmonary embolism: The Task Force for the Diagnosis and Management of Acute Pulmonary Embolism of the European Society of Cardiology (ESC)Endorsed by the European Respiratory Society (ERS). Eur Heart J 2014;35:3033–73.25173341 [Google Scholar]

- 14. Wells PS, et al. Use of a clinical model for safe management of patients with suspected pulmonary embolism. Ann Intern Med 1998;129:997–1005. 10.7326/0003-4819-129-12-199812150-00002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Wells PS, Anderson DR, Rodger M, et al. Derivation of a simple clinical model to categorize patient’s probability of pulmonary embolism: increasing the model’s utility with the SimpliRED d-dimer. Thromb Haemost 2000:416–20. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Le Gal G, Righini M, Roy P-M, et al. Prediction of pulmonary embolism in the emergency department: the revised Geneva score. Ann Intern Med 2006;144:165–71. 10.7326/0003-4819-144-3-200602070-00004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Kline JA, Nelson RD, Jackson RE, et al. Criteria for the safe use of D -dimer testing in emergency department patients with suspected pulmonary embolism: a multicenter US study. Ann Emerg Med 2002;39:144–52. 10.1067/mem.2002.121398 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. van der Hulle T, Cheung WY, Kooij S, et al. Simplified diagnostic management of suspected pulmonary embolism (the years study): a prospective, multicentre, cohort study. The Lancet 2017;390:289–97. 10.1016/S0140-6736(17)30885-1 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Lucassen W, Geersing G-J, Erkens PMG, et al. Clinical decision rules for excluding pulmonary embolism: a meta-analysis. Ann Intern Med 2011;155:448 10.7326/0003-4819-155-7-201110040-00007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Tambe J, Moifo B, Fongang E, et al. Acute pulmonary embolism in the era of multi-detector CT: a reality in sub-Saharan Africa. BMC Med Imaging 2012;12 10.1186/1471-2342-12-31 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Hendriksen JMT, Geersing G-J, Lucassen WAM, et al. Diagnostic prediction models for suspected pulmonary embolism: systematic review and independent external validation in primary care. BMJ 2015;351 10.1136/bmj.h4438 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Righini M, Bounameaux H. External validation and comparison of recently described prediction rules for suspected pulmonary embolism. Curr Opin Pulm Med 2004;10:345–9. 10.1097/01.mcp.0000130329.21799.7b [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Hendriksen JMT, Geersing G-J, Lucassen WAM, et al. Diagnostic prediction models for suspected pulmonary embolism: systematic review and independent external validation in primary care. BMJ 2015. 10.1136/bmj.h4438 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Moons KGM, Kengne AP, Grobbee DE, et al. Risk prediction models: II. external validation, model updating, and impact assessment. Heart 2012;98:691–8. 10.1136/heartjnl-2011-301247 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Altman DG, Royston P. What do we mean by validating a prognostic model? Stat Med 2000;19:453–73. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Reilly BM, Evans AT. Translating clinical research into clinical practice: impact of using prediction rules to make decisions. Ann Intern Med 2006;144:201–9. 10.7326/0003-4819-144-3-200602070-00009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Justice AC, Covinsky KE, Berlin JA. Assessing the generalizability of prognostic information. Ann Intern Med 1999;130:515–24. 10.7326/0003-4819-130-6-199903160-00016 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. White RH, Keenan CR. Effects of race and ethnicity on the incidence of venous thromboembolism. Thromb Res 2009;123:S11–17. 10.1016/S0049-3848(09)70136-7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Zakai N, Lutsey P, Folsom A, et al. Black-white differences in venous thrombosis risk: the longitudinal investigation of thromboembolism etiology (Lite). Blood ASH Annual Meeting Abstracts 2010;478. [Google Scholar]

- 30. Schneider D, Lilienfeld DE, Im W. The epidemiology of pulmonary embolism: racial contrasts in incidence and in-hospital case fatality. J Natl Med Assoc 2006;98:1967–72. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Ibrahim SA, Stone RA, Obrosky DS, et al. Racial differences in 30-day mortality for pulmonary embolism. Am J Public Health 2006;96:2161–4. 10.2105/AJPH.2005.078618 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Danwang C, Temgoua MN, Agbor VN, et al. Epidemiology of venous thromboembolism in Africa: a systematic review. J Thromb Haemost 2017;15:1770–81. 10.1111/jth.13769 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Eng J. Sample size estimation: how many individuals should be studied? Radiology 2003;227:309–13. 10.1148/radiol.2272012051 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

bmjopen-2019-031322supp001.pdf (103.6KB, pdf)