Abstract

Objectives

Occupational exposure to blood and body fluids is a major risk factor for the transmission of infections to health professionals in developing countries like Ethiopia. The aim of this study was to assess standard precaution practices (SPPs) and its associated factors among health professionals working at Addis Ababa government hospitals.

Methods

A cross-sectional study was conducted on 772 health professionals working at eight government hospitals in Addis Ababa, 2015. The multistage sampling technique was used to select study participants. Health professionals who were directly participating in screening, diagnosis, treatment and follow-ups of patients were studied. SPPs by health professionals were determined by a self-rated response to a 30-item Likert scale. A respondent would be graded as ‘good’ compliant for the assessment if they scored at least the mean of the total score, or would be considered as poor compliant if they scored less. To take the hierarchical structure of the data into account during analysis, multilevel binary logistic regressions were used. The intraclass correlation coefficient was calculated to evaluate whether variations in score were primarily within or between hospitals.

Result

Out of the participants, 50.65% had good SPPs. At the individual level, attitude, age and educational status were found to be important factors of SPPs. Controlling individual-level factors, applying regular observations (adjusted OR (AOR) 1.82; 95% CI 1.2 to 2.76), providing sufficient materials (AOR 1.53; 95% CI 1.03 to 2.28) and weak measures on reported incidences (AOR 0.49; 95% CI 0.30 to 0.8) were also hospital-level factors associated with SPPs.

Conclusion

SPPs in the healthcare facilities were found to be so low that both patients and health professionals were at a significant risk for infections. The finding suggests the need for optimising individual-level and hospital-level precautionary practices.

Keywords: epidemiology, health & safety, health policy

Strengths and limitations of this study.

The strength of this study was having large sample size which increases the precision of estimates or estimation power.

Incorporating factors at two levels, individual and hospital (such as referral, general and specialised hospitals), in the Addis Ababa city.

Applying multilevel model analysis used to avoid atomistic and ecological fallacy.

The limitation of this study was the possibility of response bias that they were likely to over-report their practice.

The other limitation of this study was using unvalidated tool to measure standard precautions.

Background

Standard precaution is the basic minimum standard of hygiene to be applied throughout all contact with blood or body fluids from any patient or source regardless of diagnosis or infection status. Health professionals should apply the principles of standard precautions at each encounter with a patient and consider every person, patient or staff as potentially infectious or susceptible to infection.1–4 The practice has been designed for use in caring for all people, both clients and patients, attending healthcare facilities.5–7 Both recipients and providers of care in a hospital are at risk for acquiring and transmitting infections through exposure to blood, body fluids or contaminated materials.8–16

Health professionals are exposed to blood and other body fluids while they are performing their activities. Out of 35 million health professionals worldwide, about 3 million receive percutaneous exposures to bloodborne pathogens each year; 2 million of them to hepatitis B virus (HBV), 0.9 million to hepatitis C virus (HCV) and 170 000 to HIV. These injuries may result in 15 000 HCV, 70 000 HBV and 500 HIV infections. More than 90% of these infections are known to occur in developing countries.17

Hospital-level factors have a significant impact on the occupational exposure of health professionals. For example, a study done in São Paulo revealed that an institutional factor had significant association with standard precaution practices (SPPs). Health professionals who got support and frequent feedback on safety practice by the institutional managements had more than threefold compliance with SPPs compared with those who did not get such support and feedback.18

Adherence to SPPs is the best way of preventing health professionals, patients, visitors and communities at large from hospital-acquired infections and needle stick injuries.4 Although only minimal data have been available on the prevalence of healthcare-acquired infections (HCAIs) in Ethiopian hospitals, in developing countries with health systems and resources similar to Ethiopia, studies have shown as high as 40% HCAI rates.4 In Ethiopia, there has been a dramatic increase in the development of health facilities, but the emphasis given to preventing occupational exposures has been inadequate despite its high prevalence. For instance, a study done in Dire Dawa and Harari in 2010 showed that the prevalence of splashing of blood or body fluids to the mouth or eyes was 28.8%.9

There were some studies on SPPs done in Ethiopia9 19 20; however, the available studies did not address the problem of identifying factors at individual and hospital levels using a single analytical framework to provide reliable information. In this context, therefore, reliable information from both levels was required to design more effective strategies for increasing health professionals’ compliance with SPPs and for preventing the transmissions of infectious diseases in healthcare settings. Therefore, the aim of this study was to assess SPP and its associated factors among health professionals working at Addis Ababa government hospitals in Ethiopia.

Methods

Study setting, study design, participants and sampling procedure

Institutional-based cross-sectional study was conducted from 22 March 22 to 23 April 2015 in Addis Ababa government hospitals. There were 17 government hospitals in Addis Ababa. All health professionals who were working in the hospitals and participating in screening, diagnosis, treatment and follow-up of patients were eligible for the study. However, those health professionals who were severely ill to fill in the questionnaire were excluded from the study.

The sample size was determined by using single population proportion formula with the assumptions of 95% confidence level (Z=1.96), margin of error of 5%, proportion of 42.9%,19 design effect of 2 and 15% non-response rate9; with these assumptions, the final sample size was calculated to be 866 health professionals. Because the sample selection procedure was two-stage sampling technique, first 8 hospitals were selected with simple random sampling technique out of 17 hospitals, and then the health professionals were selected with simple random sampling method after allocating the overall sample size proportionally to the selected hospitals.

Data collection tools, quality control issues and study variables

A structured questionnaire was adapted from different literatures and Ethiopian Hospital Reform Implementing Guideline to collect data. Eight BSc nurse data collectors and two supervisors (health officers) were assigned for data collection using self-administered method.

The questions were first prepared in English language which was translated to Amharic and then backtranslated to English to keep its consistency. Pretest was conducted on 44 respondents (5% of total sample size) 5 days before the start of the actual data collection. The pretest was conducted on unselected governmental hospitals (Gandhi and Alert hospitals), and necessary corrections were made on the questionnaire. There was half-day training given to data collectors and supervisors focusing on how to collect the data. Before the participants gave their response, orientation was given to them on how to fill in the questionnaire. The collected data were checked for completeness and consistency by the principal investigator and the supervisors.

The outcome variable of the study was the overall SPP by health professionals and it was measured by 30 questions, which were graded by Likert scale responses on a scale of 0–5 points. The status of SPP of each participant was identified by taking the mean of the total score as a cut-off point. Accordingly, the health professionals who scored less than the mean score value were considered as having poor SPP and others who scored greater than the mean score value were considered as having good SPP.

The independent variables considered in the study were individual-level variables such as sociodemographic characteristics, knowledge and attitude of the respondents, and hospital level variables such as frequent observation and hospital category (general, special and referral hospital). The reliability coefficient for knowledge, attitude and practice items had a Cronbach’s alpha of 0.732, 0.725 and 0.797, respectively.

The respondents were asked 12 Likert’s scale questions to measure the attitude of respondents. All responses of participants were computed to determine the total scores and to calculate the mean. The mean score was used to divide the participants into three groups as positive, neutral and negative groups. Those participants who scored greater than the mean plus SD was considered as having positive attitude, within the interval of mean plus or minus SD as neutral, and less than mean minus SD as negative attitudes.21

Patient and public involvement

Patients and the public were not involved in the design and conception of the study and there are no plans to disseminate the results to patients.

Data management and analysis

After appropriate coding, the data were entered into Epi Info V.7 software and exported to Stata V.12 software for analysis. Descriptive analyses were performed using numbers and percentages to show the distribution of the outcome variables by different factors.

Using a two-level binary logistic regression modelling, we examined the effect of a number of individual-level and hospital-level variables. Thus, three different models were constructed for the analysis: the first model is an empty model without any explanatory variable; the second model controlled for the individual-level variables; and the third model controlled for both the individual-level and hospital-level variables simultaneously. A p value of less than 0.05 was used to define statistical significance. The deviance information criterion (DIC) was used as a measure of how well our different models fitted the data. The intraclass correlation coefficient (Rho) was calculated to evaluate whether the variation in the scores is primarily within or between the hospitals.

Ethical considerations

Official letters were given to the Ministry of Health, Addis Ababa health office and the selected hospitals. The purpose and significance of the study were explained for each participant. Written informed consent was obtained from each study participant before they fill in the questionnaire, and participants’ involvement was only on a voluntary basis. Participants who were not willing to participate and want to resign at any step of filling the questionnaire were informed to do so without any restriction. We never wrote the names of participants in the questionnaire, and the confidentiality of the data has been kept at all level of the study.

Result

Sociodemographic characteristics

A total of 772 participants were involved in the study with 89.2% response rate. The majority (54.4%) of the respondents were nurses and slightly more than half, that is, 397 (51.42%) of the respondents were BSc health professionals. The mean (SD) age and work experience of respondents were 29.63 (6.95) and 6.04 (6.02) years, respectively (table 1).

Table 1.

Sociodemographic characteristics of health professionals in Addis Ababa government hospitals (n=772), 2015

| Variable | Frequency | Percentage |

| Age category | ||

| 20–29 | 400 | 51.81 |

| 30–39 | 300 | 38.86 |

| 40–49 | 42 | 5.44 |

| 50–59 | 30 | 3.89 |

| Sex | ||

| Male | 360 | 46.63 |

| Female | 412 | 53.37 |

| Profession | ||

| Nurse | 420 | 54.4 |

| Doctors* | 149 | 19.18 |

| Laboratory | 69 | 8.94 |

| Health officer | 54 | 6.99 |

| Midwife | 39 | 5.05 |

| Psychiatry | 20 | 2.72 |

| Anaesthesiology | 21 | 2.72 |

| Work experience in years | ||

| <1 | 18 | 2.33 |

| 1–5 | 457 | 59.2 |

| 6–10 | 215 | 27.85 |

| >10 | 82 | 10.62 |

| Marital status | ||

| Married | 287 | 37.18 |

| Single | 466 | 60.36 |

| Others† | 19 | 2.46 |

*Specialists and medical doctor.

†Widowed, separated and divorced.

‡Assistant nurse.

Standard precaution practices

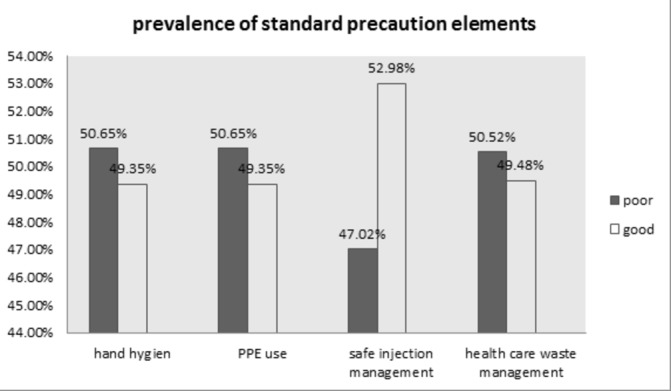

Good SPP among health professionals working at Addis Ababa hospitals was 50.65% (95% CI 46.1% to 53.9%). About 61.5% (95% CI 58.3% to 64.9%) of the participants always changed gloves between patient contacts, and 21.11% (95% CI 18.4% to 23.8%) of them always recapped used needles. Out of the SPP elements, only safe injection management was practised above fifty percent (50%) (figure 1).

Figure 1.

Percentage of standard precaution practices among health professionals working in Addis Ababa government hospitals, 2015.

Out of the participants, 57.6%, 28.4%, 8.7,2.9% and 2.5% washed their hands always, often, sometimes, seldom and never, respectively, after any direct contact with patients. Moreover, only 59.2% of the respondents always disposed waste in coded bins accordingly.

In the intercept model (null model), the result indicated that there was considerable heterogeneity among hospitals. The intraclass correlation in the null model for SPPs indicated that 5.6% of the total variance could be attributed to differences among hospitals (table 2).

Table 2.

Parameter coefficients of the null model in using hospital, Addis Ababa (2015)

| Random effect | Estimate | 95% CI |

| Level 2 variance—var (cons) | 0.19* | (0.055 to 0.66) |

| Rho—intraclass correlation (%) | 5.6 | |

| Deviance | 1052 |

*Significant.

In model 3, when both individual-level and hospital-level variables were added together, health professionals aged 40–49 were more likely to practise standard precautions (OR=2.98; 95% CI 1.05 to 7.25) than the younger health professionals, aged 20–29. The odds of practising SPP for BSc health professionals were decreased by 38% compared with diploma health professionals (OR=0.62; 95% CI 0.4 to 0.9). The odds of developing good SPPs among health professionals who had positive attitude were 8.12 times higher compared with health professionals who had negative attitude towards SPP (table 3).

Table 3.

Multilevel multivariable logistic regression modelling of factors associated with standard precaution practice among health professionals working in Addis Ababa government hospitals, 2015

| Variables | Model 1a | Model 2b | Model 3c (full model |

| OR (95% CI) | OR (95% CI) | OR (95% CI) | |

| Age category | |||

| 20–29 | 1 | 1 | |

| 30–39 | 2.00 (1.33 to 3.02)** | 1.94 (1.2 to 2.9)** | |

| 40–49 | 3.43 (1.33 to 8.83)* | 2.98 (1.05 to 7.25)* | |

| 50–59 | 5.17 (1.56 to 16.72)** | 4.57 (1.3 to 15.5)* | |

| Educational level | |||

| Diploma | 1 | 1 | |

| Degree | 0.63 (0.44 to 0.91) * | 0.62 (0.4 to 0.9) * | |

| Masters | 0.46 (0.27 to 0.78) ** | 0.5 (0.27 to 0.86) * | |

| Specialist | 0.19 (0.05 to 0.76) * | 0.25 (0.06 to 1.05) | |

| Others | 0.21 (0.01 to 2.54) | 0.25 (0.02 to 3.4) | |

| Knowledge | |||

| Poor | 1 | 1 | |

| Medium | 1.4 (0.88 to 2.25) | 1.47 (0.9 to 2.3) | |

| High | 1.43 (0.85 to 2.4) | 1.52 (0.9 to 2.6) | |

| Attitude | |||

| Negative | 1 | 1 | |

| Neutral | 3.25 (2.02 to 5.26)*** | 3.04 (1.9 to 4.96)*** | |

| Positive | 8.4 (4.46 to 15.73)*** | 8.12 (4.25 to 15.53)*** | |

| Hospital-level variable | |||

| Provide safety box and waste bin adequately | |||

| Yes | 1.01 (0.9 to 1.03) | ||

| No | 1.0 | ||

| Measures for reported incidences | |||

| Yes | 1.0 | ||

| No | 0.49 (0.3 to 0.8) ** | ||

| Allocate budget for SPP activities | |||

| Yes | 1.02 (0.66 to 1.57) | ||

| No | 1.0 | ||

| Provide materials for SPP activities | |||

| Yes | 1.5 (1.03 to 2.27)* | ||

| No | 1.0 | ||

| Management give feedback by regular observation | |||

| Yes | 1.82 (1.2 to 2.74)** | ||

| No | 1.0 | ||

| Management give feedback by giving immediate response for problems | |||

| Yes | 1.45 (0.86 to 2.40) | ||

| No | 1.0 | ||

| Facilitate health professionals and experts to post safety symbols | |||

| Yes | 0.82 (0.49 to 1.35) | ||

| No | 1.0 | ||

| Standard of the hospital | |||

| General hospital | 1 | ||

| Specialised hospital | 2.35 (1.44 to 3.8)* | ||

| Referral hospital | 1.01 (0.64 to 1.58) | ||

| Random effect | Model 1 | Model 2 | Model 3 |

| Hospital-level variance | 0.19 (0.06 to 0.66) | 0.13 (0.03 to 0.57) | 0.14 (0.03 to 0.6) |

| Model fit statistics | Model 1 | Model 2 | Model 3 |

| Deviance | 1052 | 958 | 902 |

| AIC | 1055 | 1002 | 970 |

a=there is no independent variable in the model; b=only individual-level variables included in the model; c=all level variables included in the model.

*p<0.05; **p<0.01; ***p<0.001.

AIC, Akaike Information Criterion; SPP, standard precaution practice.

On the other hand, a specialty level education, which was a significant variable at individual-level training compared with diploma-level training, became a non-significant variable in a model containing both individual-level and hospital-level variables (table 3).

Discussion

Our study found that almost half of the health professionals had good SPP. The study also revealed that positive attitude, low educational level and old age were positively associated with good SPPs at the individual level. Among hospital-level factors, feedback and regular observations, no response to reported incidences, provision of materials and hospital standards were significantly associated with SPPs.

The prevalence of good SPP noted in this work is in line with that of a study done among Nigerian health professionals (46.8%).22 However, it is higher than the result of a study done in northern Ethiopia (42.9%).19 The difference might be due to variations in the attitude of individuals towards SPPs, regular observations, feedback, work experience and availability of facilities. On the other hand, our finding is lower than that of a study done in eastern Ethiopia (80%). The possible explanation might be due to the different study participants in that the eastern Ethiopia study involved those who were both hospital and health centre workers. Another possible explanation could be differences in the data collection tools used.9

The prevention of potential exposure to blood and other body fluids depends on the type of procedures and personal protective equipment available.4 9 In our study, 61.5% of the health professionals always changed gloves between patient contacts, but that was lower than a study done in Nigeria (72.4%).23 24 The variations between the findings of the two studies may be due to the negligence of health professionals in our study setting and differences in the availability of gloves.

This study found out that about 21.1% of the health professionals always recapped used needles. This finding is relatively similar to that of a previous study done in northern Ethiopia and reported 17%.19 Although our finding was lower than that of Nigeria (36.7%),22 it was still capable of exposing health professional to infectious diseases such as HIV and HBV.

Public concern has been growing over the disposal of wastes produced by healthcare facilities in the world.25 The study found that 53.3% of health professionals never disposed of waste into the already full receptacles. This poor practice of waste segregation may be due to inadequate availability of waste bins and the negligence of health professionals for their safety.

At the individual level, attitude, education and age were found to be important variables associated with good SPPs. Thus, health professionals who had positive attitude were slightly more than eight times more likely to develop good SPPs compared with respondents who had negative attitude, keeping other variables constant. Other studies also reported the positive association between attitude and good SPP.26–30

Our study revealed that practising standard precaution among degree holders decreased by half compared with diploma health professionals. This indicates that better educational attainment had a negative effect on SPP. This could be because more educated health professionals may ignore SPPs, or they may give priority to their patients than their safety. On the other hand, older health professionals had better SPP compared with the younger groups, aged 20–29 years.31 32 This finding is dissimilar to that of another similar study.23 The possible explanation may be that the knowledge of the younger health professionals in our study setting might not be supported by adequate skills.

For hospitals that did not respond to reported incidents, the odds of developing good practice by health professionals decreased by 51% compared with hospitals that acted immediately. The odds of developing SPPs for health professionals working at hospitals and performing observations with feedback on activities relating to such practices increased by 82% compared with their counterparts. This finding was of course supported by another similar study.18

Health professionals working at hospitals with their different characteristics had different practices. The odds of developing SPPs for health professionals working at specialised hospitals were 2.4 times higher than for health professionals working at general hospitals with the same value of random effect. The possible explanation could be differences in the availability of materials and the burden of acute cases at such hospitals. Another explanation could be work in shifts at the general hospitals, which may affect the strict follow-up of some standard precaution guidelines.

The strength of the study may be the large sample size, which could have increased estimation power or the precision of estimates. Our use of a multilevel analysis which helps to avoid atomistic and ecological fallacies is another strength; the measurement of the effect of factors from both individual and hospital levels on SPP is also an attempt to address the gap we identified.9 19 20 On the contrary, the limitation of the study was the possibility of response bias as participants were likely to over-report their practices. Follow-up observations of all respondents would help to cross-check self- reported data.

In conclusion, SPPs are so low that there is an obvious likelihood of acquiring the risk for nosocomial infections. Variables such as age, educational status and attitude were factors associated with SPPs at the individual level, while lack of frequent observations, the absence of measures to cope with reported incidents, poor provision of materials and hospital standards were factors significantly associated with SPP at hospital levels.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We would like to thank the University of Gondar for ethical approval. We also like to extend our appreciation to data collectors and the study participants for their devoted cooperation.

Footnotes

Contributors: DA conceived the study ideas, design, analysed data and wrote the draft of the manuscript. LD and BAD participated in the study design, edited the manuscript and contributed to the final analysis. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Funding: The authors have not declared a specific grant for this research from any funding agency in the public, commercial or not-for-profit sectors.

Competing interests: None declared.

Patient consent for publication: Not required.

Ethics approval: Ethical statement for the study was obtained from the Ethical Committee of Institute of Public Health, College of Medicine and Health Sciences, University of Gondar.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

Data availability statement: Data are available on reasonable request.

References

- 1. Stokes L. Infection prevention policy standard precautions policy 2012.

- 2. Health service executes Standard precaution guideline 2009.

- 3. Katherine H, Murray L. Standard precautions a new approach to reducing infection transmission in the hospital setting. Journal of intravenous nursing 1997;20. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Minister of Health Ethiopian Hospital reforming implementation guideline 2010.

- 5. Infection Control Steering Committee Australian guidelines for the prevention and control of infection in health care 2010.

- 6. Beltrami EM, Williams IT, Shapiro CN, et al. Risk and management of blood-borne infections in health care workers. Clin Microbiol Rev 2000;13:385–407. 10.1128/CMR.13.3.385 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Siegel JD, Rhinehart E, Jackson M, et al. Guideline for isolation precautions: preventing transmission of infectious agents in healthcare settings 2007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 8. JHPIEGO Infection prevention guidelines for healthcare facilities with limited resources 2003.

- 9. Reda AA, Fisseha S, Mengistie B, et al. Standard precautions: occupational exposure and behavior of health care workers in Ethiopia. PLoS One 2010;5:e14420 10.1371/journal.pone.0014420 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Barikani A, Afaghi A. Knowledge, attitude and practice towards standard isolation precautions among Iranian medical students. Glob J Health Sci 2012;4 10.5539/gjhs.v4n2p142 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Enwere OO, Diwe KC. Knowledge, perception and practice of injection safety and healthcare waste management among teaching hospital staff in South East Nigeria: an intervention study. Pan Afr Med J 2014;17 10.11604/pamj.2014.17.218.3084 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Li L, Lin C, Wu Z, et al. Hiv-Related avoidance and universal precaution in medical settings: opportunities to intervene. Health Serv Res 2011;46:617–31. 10.1111/j.1475-6773.2010.01195.x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Foster TM, Lee MG, McGaw CD, et al. Knowledge and practice of occupational infection control among healthcare workers in Jamaica. West Indian Med J 2010;59:147–52. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Farley JE, Tudor C, Mphahlele M, et al. A national infection control evaluation of drug-resistant tuberculosis hospitals in South Africa. Int J Tuberc Lung Dis 2012;16:82–9. 10.5588/ijtld.10.0791 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Zalat M, Zalat M. Assessment of compliance to standard precautions among surgeons in Zagazig university hospitals, Egypt, using the health belief model. Journal of The Arab Society for Medical Research 2014;9:6–14. 10.4103/1687-4293.137319 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Adinma ED, Ezeama C, Adinma JIB, et al. Knowledge and practice of universal precautions against blood borne pathogens amongst house officers and nurses in tertiary health institutions in Southeast Nigeria. Niger J Clin Pract 2009;12:398–402. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. World health organization Health care worker safety 2005.

- 18. Victor E, Elaine S, Malaguti T, et al. Individual, work-related and institutional factors associated with adherence to standard precautions. J Infect Control 2013;2:106–11. [Google Scholar]

- 19. Gebresilassie A, Kumei A, Yemane D. Standard precautions practice among health care workers in public health facilities of Mekelle special zone, Northern Ethiopia. Commun Med Health Ed 2014;4. [Google Scholar]

- 20. Feleke BE. Prevalence and determinant factors for sharp injuries among Addis Ababa Hospital health professionals. Journal of Public Health 2013;1:189–93. [Google Scholar]

- 21. Najeeb N. Knowledge of standard and transmission based precautions in teritary and secondary health care settings of maldavies, India 2007.

- 22. Alice TE, Akhere AD, Ikponwonsa O, et al. Knowledge and practice of infection control among health workers in a tertiary hospital in Edo state,Nigeria. Direct Res J Health Pharm 2013;1:20–7. [Google Scholar]

- 23. Amoran OE, Onwube OO. Infection control and practice of standard precautions among healthcare workers in northern Nigeria. J Glob Infect Dis 2013;5:156–63. 10.4103/0974-777X.122010 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Abah SO, Ohimain EI. Healthcare waste management in Nigeria: a case study. J Public Health Epidemiol 2011;3:99–110. [Google Scholar]

- 25. World health organization Safe management of wastes from healthcare activities 2014.

- 26. Garland KV. A Survey of United States Dental Hygienists’ Knowledge, Attitudes, and Practices with Infection Control Guidelines. The Journal of Dental Hygiene 2013;87. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Mukherjee S, Bhattacharyya A, SharmaSarkar B, et al. Knowledge and practice of standard precautions and awareness regarding post-exposure prophylaxis for HIV among interns of a medical college in West Bengal, India. Oman Med J 2013;28:141–5. 10.5001/omj.2013.38 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Holla R, Kanchan T, Kumar N. Perception and practice of standard precautions among health care professionals at tertiary care hospitals in coastal South India. Asian J Pharm Clin Res 2014;7:101–4. [Google Scholar]

- 29. Beghdadli BZ, Chabane W, Ghomari O, et al. Standard precautions" practices among nurses in a university hospital in Western Algeria. US national library of medicine 2008;20. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Ministry of Health Malaysia Policies and procedures for infection control 2010.

- 31. Alice TE, Akhere AD, Ikponwonsa O, et al. Knowledge and practice of infection control among health workers in a tertiary hospital in Edo state, Nigeria. Direct Res J Health Pharm 2013;2:20–7. [Google Scholar]

- 32. W. Gichuhi A, Kamau SM, Nyangena E. Health care workers adherence to infection prevention practices and control measures: a case of a level four district hospital in Kenya. AJNS 2015;4:39–44. 10.11648/j.ajns.20150402.13 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.