Abstract

Introduction

Cardiovascular diseases are the main cause of mortality and disability worldwide, so the prevention becomes a priority in terms of public health. Therefore, it is necessary to use validated strategies to adequately identify these patients in daily clinical practice. The objective of this scope review is to comprehend and comprehensively describe the anthropometric indicators used in studies, such as such as weight, height, circumferences, lengths and skin folds, that address its association with coronary artery calcification to identify cardiovascular risk in the adult population.

Methods and analysis

Using Arksey and O'Malley's scoping review methodology as a guide, our scoping review of published reviews begins by searching several databases: Cochrane Central Register of Controlled Trials in the Cochrane Library, Medline Complete (EbscoHost), Embase, LILACS (Literatura Latino-Americana e do Caribe em Ciências da Saúde-BIREME Literatura Latino-Americana e do Caribe em Ciências da Saúde)and Web of Science and Scielo. As well as, it will be searched in the International Platform of the Registry of Clinical Trials of the WHO (www.who.int/ictrp); ClinicalTrials.gov; Transforming Research into Practice. Our team has formulated search strategies and two reviewers will independently screen eligible studies for final study selection. Bibliographic data and abstract content will be collected and analysed using a tool developed iteratively by the research team.

Ethics and dissemination

This protocol reports a comprehensive, rigorous and transparent methodology. This scoping review will be the first study to compare anthropometric measurements and coronary artery calcification, and thereby will contribute to the design and comparison of future studies in this field. This protocol reports a comprehensive, rigorous and transparent methodology. The results will be disseminated through a peer-reviewed publication. By identifying gaps in the current body of literature, this study can guide future research.

Keywords: anthropometric indicators, cardiovascular diseases, coronary artery calcification

Strengths and limitations of this study.

This is a novel review approach to cover a vast volume of literature on a broad topic, thus offering a ‘big picture’ or map of research on the anthropometric indicators that address its association with coronary artery calcification to identify cardiovascular risk.

This protocol outlines a rigorous study design that includes the use of an established scoping review methodology, a multidisciplinary search strategy developed iteratively in consultation with an experienced medical librarian and a study selection and data extraction process that is carried out in tandem with validation from content experts.

The synthesis of data will be limited to a peer-reviewed published work.

Background

Cardiovascular diseases (CVD) are the main cause of mortality and disability worldwide. In this sense, the prevention of CVD becomes a priority in terms of public health, especially in those individuals considered to be at high cardiovascular risk (CVR). Therefore, it is necessary to use validated strategies to adequately identify these patients in daily clinical practice. The application of methods to determine body composition began in the 1940s, and was expanded to a variety of methods, being used as an indicator of health status, treatment evolution and functional condition.1

These factors make it interesting to investigate the use of anthropometry as a method of assessing the risk of cardiovascular disease, since it is easy to apply in the clinic due to being operationally simple techniques, low cost and providing information about risk factors2 that can aid in the prevention and treatment of diseases. Anthropometry is one of the methods of assessing body composition and is defined as: ‘the science that studies the measurement of size, weight and proportions of the human body’.3 Perissinotto et al found that non-pathological factors that may affect anthropometric characteristics should be taken into account, such as age, gender and geographical area.4 Anthropometric measures have been the focus of many studies. However, some difficulties such as the possible redistribution of fat, the choice of the most appropriate equation and the best measurement technique are important issues that may limit the accuracy in the elderly populations.5

Through the various anthropometric measures, data such as weight, height, circumferences, lengths and skin folds can be obtained. The values obtained allow us to calculate secondary measures such as body mass index (BMI), arm muscle circumference, arm muscle area and others¹. To estimate the body fat compartment, there are several formulas that use the value of the skin folds, each of which determines the number and location of the pleat to be used.6 Each of these measures and their interrelations determine a specific body compartment, with a greater or lesser degree of precision¹. However, there are criticism concerning the estimation of body composition by anthropometry because it can present important changes in results by interindividual variability.

Some anthropometric indices are associated with chronic diseases. The WHO defines obesity as an excess of fat per se and as a fat accumulation that is related to worsening health and uses BMI (kg/m2) to classify it.7 BMI is also used to predict the evolution and risk of disease, but it does not differentiate, for example, excess fat from excess lean mass/muscle or even oedema. For example, a bodybuilder may have a BMI above 30 kg/m2 and should not be characterised as excess fat but rather as weight.8 However, population studies have observed that the increase in BMI from 25 kg/m2 has a positive curvilinear correlation with cardiovascular diseases, hypertension and some types of cancer, bladder diseases, diabetes and higher mortality.9 In older men and women (65–74 years old), BMI >27 kg/m2 was associated with worsening of glycaemia, triglycerides and high-density lipoprotein cholesterol.10 In this study, patients were randomly assigned to either the intra-abdominal fat11 or to the BMI.12 13 The abdomen / hip circumference index is correlated with intra-abdominal fat11 and together with BMI, have a prognostic value for dyslipidaemias and coronary diseases.12 13

Among the many methods of CVR evaluation, the coronary artery calcification (CAC) deserves attention because it is a direct and non-invasive way of measuring calcium deposited in the coronary arteries.14–16 CAC proves to be a strong independent predictor of cardiovascular events, providing considerable, superior and additional prognostic information against clinical risk assessment methods.17 The risk assessment offered by the CAC goes beyond that offered by the Framingham Risk Score, for example, and to populations of different ethnicities,18 having overcome clinical risk factors and other non-invasive methods in the evaluation of CVR.19–21 The use of CAC allows restratification of CVR in patients classified as intermediate risk for low-risk or high-risk ranges,22 potentially modifying the profile and intensity of the approach to risk factors. In addition, international recommendations advocate the use of CAC as a tracking tool.23 Therefore, the quantitative evaluation of coronary calcium with CT has a definite role in the identification and stratification of coronary artery disease risk.

Study rationale

Currently, the Coronary Calcium Score imaging test is considered the gold standard for identifying CVR in patients. And there is no consensus in the literature about the anthropometric measure that best indicates the CVR. As well as there is no literature review that analyses the interrelation of the anthropometric measurements of CVR and imaging tests.

This review is therefore important because it aims to identify the anthropometric measure that is closest to the results of exams in the identification of CVR. In this way, it assists in the patients diagnoses, guaranteeing a better therapeutic result and a cost-effective approach to patient care.

In resource-limited settings, access to screening is limited and the risk of patients lost to follow-up is high. So, anthropometric indicators to be applied at point of care, which detect CVR, have become popular in those settings due to their advantages: the quickness in giving results, the possibility of giving guidance immediately, are performed with minimal technical training in non-laboratory settings and detect the risk for the disease at the clinical setting. In addition, as the test results are obtained on the same day expressed in a qualitative way (detected or not detected), and guidance can be provided right away.

Study objective

The objective of this scope review is to comprehend and comprehensively describe the anthropometric indicators used in studies that address its association with CAC to identify CVR in the adult population.

Methods and analysis

Protocol design

The methodology for this scoping review was based on the framework outlined by Arksey and O'Malley, methodological enhancement made by Levac et al and the Joanna Briggs Institute.24 25 The review will include the following five key phases: (1) identifying the research question, (2) identifying relevant studies, (3) study selection, (4) charting the data and (5) collating, summarising, and reporting the results.

In preparation for this review, a pilot scoping search for anthropometric indicator versus Calcium Coronary Score was done to identify the list of all eligible index tests. The pilot search was conducted in two steps: first, we searched for all anthropometric indicator, and second, we searched for test accuracy studies for each of the anthropometric indicator found by our first search comparing to Calcium Coronary Score. The first search, concerning available anthropometric indicator, was restricted to English and Portuguese articles. This pilot search (conducted in April/May 2019) resulted in a list of 241 eligible articles at Pubmed research.

Stage 1: identifying the research question

This review was guided by the question, ‘What is the diagnostic accuracy of anthropometric methods associated with CAC to measure CVR in the adult population?’ For the purposes of this study, a scoping review is defined as a type of research synthesis that aims to ‘map the literature on a particular topic or research area and provide an opportunity to identify key concepts, gaps in the research and types and sources of evidence to inform practice, policymaking and research’.26

As scoping is an iterative process, we might add additional questions based on our findings along the review process.24 While the eventual goal of this study is to contribute to the understanding of the process of nursing students’ learning in practice, we will also synthesise results that are relevant to this topic.

Stage 2: identifying relevant studies

Search strategy and information sources

To the databases selection it will be considered the coverage in the area of Health Sciences and availability through the Portal of Periodicals of Capes and the Portal of the Library System of the Federal University of Paraná. The selected databases will be: Cochrane Central Register of Controlled Trials in the Cochrane Library, Medline Complete (EbscoHost), Embase (Ovid SP), LILACS (Literatura Latino-Americana e do Caribe em Ciências da Saúde-BIREME Literatura Latino-Americana e do Caribe em Ciências da Saúde) Web of Science, Scopus and SciELO. As well as, will search in the International Platform of the Registry of Clinical Trials of the WHO (www.who.int/ictrp); ClinicalTrials.gov; Transforming Research into Practice and will be updated. We will apply language limits to the searches (Portuguese, English, Spanish).

To ensure that all relevant information is retrieved, we will also search a variety of grey literature sources. We will search relevant grey literature databases (eg, Grey Literature Report, OpenGrey, Web of Science Conference Proceedings) to identify studies, reports and conference abstracts of relevance to this review. We will also conduct a targeted search of the grey literature in local, provincial, national and international organisations’ websites and related health or scientific organisations classification.

The search strategy for the scoping review will be as comprehensive as possible within the constraints of time and resources to identify both published and unpublished (grey literature) primary studies as well as reviews. As recommended in all JBI (Joanna Briggs Institute) types of reviews, a four-step search strategy is to be used (table 1)

Table 1.

Table showing the four-step search strategy

| Step | Strategy |

| 1 | Limited search of Pubmed, analysis of text words in titles and abstracts and of index terms used to describe the articles (241 articles in 28th May 2019) |

| 2 | Search using all identified keywords and index terms across all included databases: Cochrane Central Register of Controlled Trials in the Cochrane Library, Medline Complete (EbscoHost), Embase (Ovid SP), LILACS (BIREME) and Web of Science and Scielo. Also, it will be searched in the International Platform of the Registry of Clinical Trials of the WHO (www.who.int/ictrp); ClinicalTrials.gov; Transforming Research into Practice and will be updated. |

| 3 | Search of reference lists of all identified reports and articles for additional studies |

| 4 | Search of all relevant published systematic reviews and consultation with experts |

Search terms will be determined with input from the research team, research collaborators and knowledge users. The search strategy was developed by an experienced research librarian and was revised pending input from stakeholders. The search will combine terms from two thematic blocks were drawn: anthropometric indicators (comparator 1) and CAC (comparator 2). Terms will be searched as both keywords in the title and/or abstract and subject headings (eg, Medical Subject Headings, EMTREE - Embase subjects headings) as appropriate. No language or date limits will be applied.

The search strategy example is showed in table 2.

Table 2.

Table showing search strategy example for PubMed

| Search | Query |

| #1 Comparator 1 |

(anthropometry OR anthropometric OR “anthropometric indicator” OR “anthropometric marker” OR “anthropometric parameter” OR “anthropometric measurement”) |

| #2 Comparator 2 |

(“calcium coronary score” OR “calcium artery score” OR “calcium coronary artery score” OR “coronary artery calcium” OR “coronary calcification” OR “coronary artery calcium score” OR “computed tomographic angiography”) |

| #3 | #1 AND #2 |

| Limits | Age +18, Language (Portuguese, Spanish, English), Human Studies |

Stage 3: study selection

The review process will consist of two levels of screening: (1) a title and abstract review and (2) full-text review. For the first level of screening, two investigators will independently screen the title and abstract of all retrieved citations for inclusion against a set of minimum inclusion criteria. The criteria will be tested on a sample of abstracts prior to beginning the abstract review to ensure that they are robust enough to capture any articles that may relate to the theme. Any articles that are deemed relevant by either or both of the reviewers will be included in the full-text review. In the second step, the two investigators will then each independently assess the full-text articles to determine if they meet the inclusion/exclusion criteria. To determine inter-rater agreement, Cohen’s κ statistic will be calculated at both the title and abstract review stage and at the full-article review stage.27 Any discordant full-text articles will be reviewed a second time, and further disagreements about study eligibility at the full-text review stage will be resolved through discussion with a third investigator until full consensus is obtained.

We will include all study designs seeking to evaluate anthropometric measurements as CVR index, in which it was compared with an eligible reference standard (Coronary Calcium Score). The anthropometric measure may have been assessed alone or in conjunction with (and/or compared with) other measures. The studies should have measured anthropometry and performed a Coronary Calcium Score simultaneously or at least prior to any intervention to ensure that the comparative tests reflect the same status. However, we will include studies in which this is not explicitly stated.

We will include prospective and retrospective studies in the analysis.

The inclusion criteria will be developed in an iterative process in which the reviewers calibrate a threshold for inclusion and exclusion. The initial inclusion criteria will be: adults without any kind of intervention at prescreening (surgeries, drug treatment, specific diseases).

Since we are interested in learning how CAC and anthropometric measurements are associated, we exclude adults with intervention at the time of prescreening or adolescents/children (<18 years of age) or specialised populations (specific diseases; drug treatment).

The exposure of this review will be an individual’s total and regional body composition. These measures may include, but are not limited to: height (m), mass (kg) and BMI (kg/m2), waist circumference (cm), hip circumference (cm), total body fat (g), total body fat percentage (%), android fat (g), gynoid fat (g) and intra-abdominal body fat (g, cm2, cm3).

Stage 4: data collection

Data will be extracted from full-text journal articles which meet the aforementioned inclusion criteria. A data collection instrument will be developed by the research team to confirm study relevance and to extract study characteristics. Study characteristics to be extracted will include, but not be limited to: publication year, publication type (eg, original research), study design, country, patient population characteristics, anthropometric measurements, calcium artery calcification method, cut-off points, outcomes, study quality). This form will be reviewed by the research team and pretested by all reviewers before implementation to ensure that the form is capturing the information accurately. Data abstraction will be conducted in duplicate with two reviewers independently (CF and NMC) extracting data from all included studies. To ensure accurate data collection, each reviewer’s independent abstracted data will be compared and any discrepancies will be further discussed to ensure consistency between the reviewers. The search results will be imported into the EndNote (Thomson Reuters) citation manager and pooled into a single library.

Stage 5: data summary and synthesis of results

Since a scoping review can be used to map the concepts underpinning a research area and the main sources and types of evidence available, the aggregated findings provide an overview of the research rather than an assessment of the quality of individual studies. Although formal assessment of study quality is generally not performed in scoping reviews, some claim it should be incorporated in the methodology.26 28 Assessing study quality will enable us to address quantitative and qualitative gaps in the literature.25 We will therefore assess the quality of included studies by a set of quality indicators for reviews developed by Buckley et al.29 The analytic frame will be piloted on 5–10 articles by the team and will allow us to analyse the selected articles through a common framework.

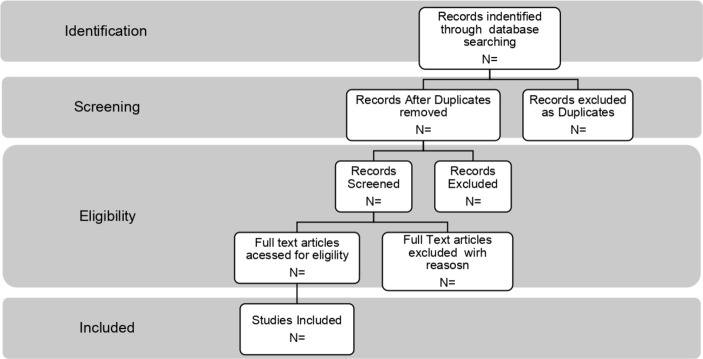

A Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses flow diagram will be used to report final numbers in the resulting study publication. As we expect a diverse body of knowledge, we will give a descriptive account of concepts and subsequent operationalisations. We will synthesise study findings using narrative descriptions based on themes that emerge from the extracted data. The results will be compared and consolidated through consensus between two of the reviewers, CF and NMC (figure 1).30

Figure 1.

Flow diagram for the scoping review process adapted from the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses statement by Moher and colleagues.30

A narrative summary will accompany the diagram results and will describe how the results relate to the review’s objective and questions.

Patient and public involvement

No patient involved.

Ethics and dissemination

This protocol reports a comprehensive, rigorous and transparent methodology. This scoping review will be the first study to compare anthropometric measurements and CAC, and thereby will contribute to the design and comparison of future studies in this field. The results will be disseminated through a peer-reviewed publication. By identifying gaps in the current body of literature, this study can guide future research. Both the methodology and the results may be of interest for researchers, doctors, nutritionist and other health professions given the widely spread importance of learning in clinical practice. Since the methodology applied consists of reviewing and collecting data from publicly available materials, this study does not require an ethical approval.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

This review will contribute to a Master of Internal Medicine and Health Sciences degree for CF.

Footnotes

Contributors: CF conceived the idea, developed the research question and study methods and contributed meaningfully to the drafting and editing. NMC, FEZN, CCBA, ELJ aided in developing the research question and study methods contributed meaningfully to the drafting and editing.

Funding: This study is financed in part by the Coordenação de Aperfeiçoamento de Pessoal de Nível Superior—Brasil (CAPES)—Finance Code 001.

Competing interests: None declared.

Patient consent for publication: Not required.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

References

- 1. Navarro AM, Marchini JS. Uso de medidas antropométricas para estimar gordura corporal em adultos. Nutrire Rev Soc Bras Alim Nutr = Brazilian Food Nutr 2000;19/20:31–74. [Google Scholar]

- 2. Ball SD, Altena TS, Swan PD. Comparison of anthropometry to DXA: a new prediction equation for men. Eur J Clin Nutr 2004;19:1–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Pollock ML, Wilmore JH, Fox III SM. Exercícios na Saúde e na Doença – Avaliação e prescrição para prevenção e reabilitação. Editora MEDSI Rio de Janeiro RJ 1986:235–40. [Google Scholar]

- 4. Perissinotto E, Pisent C, Sergi G, et al. . Anthropometric measurements in the elderly: age and gender differences. Br J Nutr 2002;87:177–86. 10.1079/BJN2001487 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Visser M, Heuvel EVD, Deurenberg P. Prediction equations for the estimation of body composition in the elderly using anthropometric data. Br J Nutr 1994;71:823–33. 10.1079/BJN19940189 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Trischler KA. Medida e Avaliação me Educação Física e Esportes de Barrow & McGee. Ed. da tradução da 5º Edição: Greguol M Barueri, SP, Manole, 2003: 229–71. [Google Scholar]

- 7. World Health Organization Physical status: the use and interpretation of anthropometry. Report of a WHO expert committee. World Health Organ Tech Rep Ser 1995;854:1–452. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Svendsen OL. Should measurement of body composition influence therapy for obesity? Acta Diabetol 2003;40:s250–3. 10.1007/s00592-003-0078-y [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Bray GA. Obesity: definition, diagnosis and disadvantages. Med J Aust 1985;142(7 Suppl):2–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Cabrera MAS, Jacob Filho W. Obesidade em idosos: Prevalência, distribuição E associação com hábitos E co-morbidades. ArqBras Endocrinol Metab 2001;45:494–501. [Google Scholar]

- 11. Kim SK, Kim HJ, Hur KY, et al. . Visceral fat thickness measured by ultrasonography can estimate not only visceral obesity but also risks of cardiovascular and metabolic diseases. Am J Clin Nutr 2004;79:593–9. 10.1093/ajcn/79.4.593 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Rosenbaum M, Leibel RL, Hirsch J. Obesity. N Engl J Med 1997;337:396–407. 10.1056/NEJM199708073370606 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Misra A, Pandey RM, Sinha S, et al. . Receiver operating characteristics curve analysis of body fat & body mass index in dyslipidaemic Asian Indians. Indian J Med Res 2003;117:170–9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Bischoff B, Kantert C, Meyer T, et al. . Cardiovascular risk assessment based on the quantification of coronary calcium in contrast-enhanced coronary computed tomography angiography. Eur Heart J Cardiovasc Imaging 2012;13:468–75. 10.1093/ejechocard/jer261 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Tota-Maharaj R, Blaha MJ, McEvoy JW, et al. . Coronary artery calcium for the prediction of mortality in young adults 75 years old. Eur Heart J 2012;33:2955–62. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Tota-Maharaj R, Blaha MJ, Blankstein R, et al. . Association of coronary artery calcium and coronary heart disease events in young and elderly participants in the multi-ethnic study of atherosclerosis: a secondary analysis of a prospective, population-based cohort. Mayo Clin Proc 2014;89:1350–9. 10.1016/j.mayocp.2014.05.017 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Hecht HS. Coronary artery calcium scanning: past, present, and future. JACC Cardiovasc Imaging 2015;8:579–96. 10.1016/j.jcmg.2015.02.006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Greenland P, LaBree L, Azen SP. Coronary artery calcium score combined with Framingham score for risk prediction in asymptomatic individuals. JAMA 2004;291:210–5. 10.1001/jama.291.2.210 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Peters SAE, den Ruijter HM, Bots ML, et al. . Improvements in risk stratification for the occurrence of cardiovascular disease by imaging subclinical atherosclerosis: a systematic review. Heart 2012;98:177–84. 88 10.1136/heartjnl-2011-300747 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Yeboah J, McClelland RL, Polonsky TS, et al. . Comparison of novel risk markers for improvement in cardiovascular risk assessment in intermediate-risk individuals. JAMA 2012;308:788–95. 10.1001/jama.2012.9624 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Blaha MJ, Cainzos-Achirica M, Greenland P, et al. . Role of coronary artery calcium score of zero and other negative risk markers for cardiovascular disease: the multi-ethnic study of atherosclerosis (MESA). Circulation 2016;133:849–58. 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.115.018524 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Polonsky TS, et al. Coronary artery calcium score and risk classification for coronary heart disease prediction. JAMA 2010;303:1610–6. 10.1001/jama.2010.461 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Naghavi M, Falk E, Hecht HS, et al. . From vulnerable plaque to vulnerable Patient—Part III: Executive summary of the screening for heart attack prevention and education (shape) Task force report. Am J Cardiol 2006;98:2–15. 10.1016/j.amjcard.2006.03.002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Arksey H, O'Malley L. Scoping studies: towards a methodological framework. Int J Soc Res Methodol 2005;8:19–32. 10.1080/1364557032000119616 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Levac D, Colquhoun H, O'Brien KK. Scoping studies: advancing the methodology. Implementation Sci 2010;5:1–9. 10.1186/1748-5908-5-69 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Daudt HML, van Mossel C, Scott SJ. Enhancing the scoping study methodology: a large, inter-professional team’s experience with Arksey and O’Malley’s framework. BMC Med Res Methodol 2013;13:48 10.1186/1471-2288-13-48 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Cohen J. A coefficient of agreement for nominal scales. Educ Psychol Meas 1960;20:37–46. 10.1177/001316446002000104 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Peters MDJ, Godfrey C, McInerney P, et al. . Chapter 11: scoping reviews : Joanna Briggs Institute Reviewer's Manual. The Joanna Briggs Institute, 2017. https://reviewersmanual.joannabriggs.org/ [Google Scholar]

- 29. Buckley S, Coleman J, Davison I, et al. . The educational effects of portfolios on undergraduate student learning: a best evidence medical education (BEME) systematic review. BEME guide No. 11. Med Teach 2009;31:282–98. 10.1080/01421590902889897 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Moher D, Liberati A, Tetzlaff J, et al. . Preferred reporting items for systematic reviews and meta-analyses: the PRISMA statement. Ann Intern Med 2009;151:264–9. 10.7326/0003-4819-151-4-200908180-00135 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.