Abstract

Introduction

Patients with non-muscle-invasive bladder cancer (NMIBC) have a good survival but are at high risk for tumour recurrence and disease progression. It is important to identify lifestyle habits that may reduce the risk of recurrence and progression and improve health-related quality of life (HRQOL). This paper describes the rationale and design of the UroLife study. The main aim of this study is to evaluate whether lifestyle habits are related to prognosis and HRQOL in patients with NMIBC.

Methods and analysis

The UroLife study is a multicentre prospective cohort study among more than 1100 newly diagnosed patients with NMIBC recruited from 22 hospitals in the Netherlands. At 6 weeks and 3, 15 and 51 months after diagnosis, participants fill out a general questionnaire, and questionnaires about their lifestyle habits and HRQOL. At 3, 15 and 51 months after diagnosis, information about fluid intake and micturition is collected with a 4-day diary. At 3 and 15 months after diagnosis, patients donate blood samples for DNA extraction and (dietary) biomarker analysis. Tumour samples are collected from all patients with T1 disease to assess molecular subtypes. Information about disease characteristics and therapy for the primary tumour and subsequent recurrences is collected from the medical records by the Netherlands Cancer Registry. Statistical analyses will be adjusted for age, gender, tumour characteristics and other known confounders.

Ethics and dissemination

The study protocol has been approved by the Committee for Human Research region Arnhem-Nijmegen (CMO 2013-494). Patients who agree to participate in the study provide written informed consent. The findings from our study will be disseminated through peer-reviewed scientific journals and presentations at (inter)national scientific meetings. Patients will be informed about the progress and results of this study through biannual newsletters and through the website of the study and of the bladder cancer patient association.

Keywords: bladder cancer, diet, lifestyle, biomarkers, recurrence, prognosis, quality of life, cohort, study protocol

Strengths and limitations of this study.

Large multicentre prospective cohort study of non-muscle-invasive bladder cancer patients recruited shortly after diagnosis.

Extensive dietary, lifestyle, medical and health-related quality of life data at multiple time points after diagnosis.

Availability of blood samples at 3 and 15 months after diagnosis, and formalin-fixed, paraffin-embedded tumour tissue.

Limited power for subgroup analyses.

Loss to follow-up potentially influencing validity of results.

Introduction

Urinary bladder cancer is the sixth most common cancer in the male population worldwide and tenth if considering both genders.1 Approximately 75% of patients is diagnosed with non-muscle-invasive bladder cancer (NMIBC, stages Ta, T1 and Tis) and 25% with muscle-invasive bladder cancer (stages T2, T3 and T4).2 Patients with NMIBC have a good survival but are at high risk for tumour recurrence and disease progression.3 They are therefore subjected to frequent follow-up by cystoscopy and treatment. This makes bladder cancer the most expensive cancer in terms of healthcare expenditures per patient per year.4 The high recurrence rate may also impact health-related quality of life (HRQOL).5 Lifestyle factors have been linked to the prognosis and quality of life in patients with several cancer types6 7 but evidence in patients with NMIBC is scarce. If we can identify lifestyle habits that are related to the risk of recurrence and progression and HRQOL in patients with NMIBC, optimal interventions can be developed to improve their prognosis and HRQOL.

The primary risk factor for bladder cancer is smoking, which accounts for 43% of bladder cancer cases in men and 26% in women in Europe.8 Other important risk factors for bladder cancer are occupational exposures to carcinogens like aromatic amines and polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons, family history and specific low penetrance germline genetic variants.9 Recent meta-analyses suggest that excess body weight10 and physical inactivity11 may also increase bladder cancer risk. The World Cancer Research Fund/American Institute for Cancer Research report found probable evidence that arsenic in drinking water increases the risk of bladder, and limited suggestive evidence that higher consumption of fruit and vegetables and of tea decreases the risk of bladder cancer.12 For other dietary and lifestyle factors, this report concluded that data were of too low quality, inconsistent or the number of studies were insufficient to draw conclusions.12

Available evidence about the role of lifestyle habits on prognosis in patients with NMIBC is restricted to smoking13 14 and excess body weight.15 A systematic review13 and recent meta-analysis of 10 studies including a total of 6307 patients with NMIBC14 found that current and former smokers at diagnosis had an approximately 25% increased risk of recurrence compared with never smokers. Our recent meta-analysis15 of three studies16–18 showed that overweight and obesity compared with normal weight at diagnosis were associated with increased risk of recurrence but not progression in patients with NMIBC, although power for progression was limited.15 Smoking cessation and weight loss after diagnosis in relation to clinical outcomes have hardly been investigated. Evidence for other lifestyle habits, such as fluid intake and micturition, physical activity, and fruit and vegetable consumption, is very limited or not available.15 Also, most studies on lifestyle and NMIBC prognosis included a heterogeneous study population with different tumour stages and grades of bladder cancer. However, NMIBC prognosis is clearly different for these subgroups19 and may also differ by molecular subtype.20 21 Whether associations of lifestyle habits with NMIBC prognosis are mediated and/or modified by tumour stage and by molecular subtype has not yet been investigated.

Despite the high frequency of surveillance and repeated treatments, relatively little is known about the HRQOL of patients with NMIBC,22 and research with validated bladder cancer-specific instruments is needed.23 A systematic review of five studies on lifestyle and HRQOL in bladder cancer patients found some evidence for a positive association between physical activity and HRQOL, but insufficient evidence to draw any conclusions for consumption of fruit and vegetables or smoking cessation.24

The aim of our study is to evaluate the association of pre- and post-diagnosis lifestyle habits (and habit changes) with risk of recurrence and progression and HRQOL. Also, we want to explore whether this association is mediated and/or modified by tumour stage and molecular subtype.

Methods and analysis

The UroLife study (Urothelial cell cancer: Lifestyle, prognosis and quality of Life) is a prospective cohort study including patients with newly diagnosed NMIBC. The study has been designed to evaluate the association of lifestyle habits with risk of recurrence and progression and HRQOL. Patients are recruited in 22 hospitals in the east, south and central parts of the Netherlands. Before the start of the study, permission was asked from all urologists of the participating hospitals to select and invite eligible patients from the Netherlands Cancer Registry (NCR), held by the Netherlands Comprehensive Cancer Organisation (IKNL). Once every 1 to 2 weeks, new patients are identified through IKNL using notification lists of the nationwide network and registry of histo- and cytopathology in the Netherlands (PALGA Foundation). Approximately 4 weeks after diagnosis, patients are invited on behalf of their urologist to participate in this study. Patients who agree to participate provide a written informed consent.

Patient population

Eligible participants are Dutch speaking patients between 18 and 80 years old who are newly diagnosed with a histologically confirmed primary stage Ta, T1 and Tis NMIBC tumour and underwent a transurethral resection (TUR). Patients with a previous diagnosis of cancer in the past 5 years and those with a lymph node metastasis or distant metastasis are not eligible.

Patient and public involvement

Patients were not involved in the design, recruitment and conduct of the study.

Data collection and management

Questionnaires

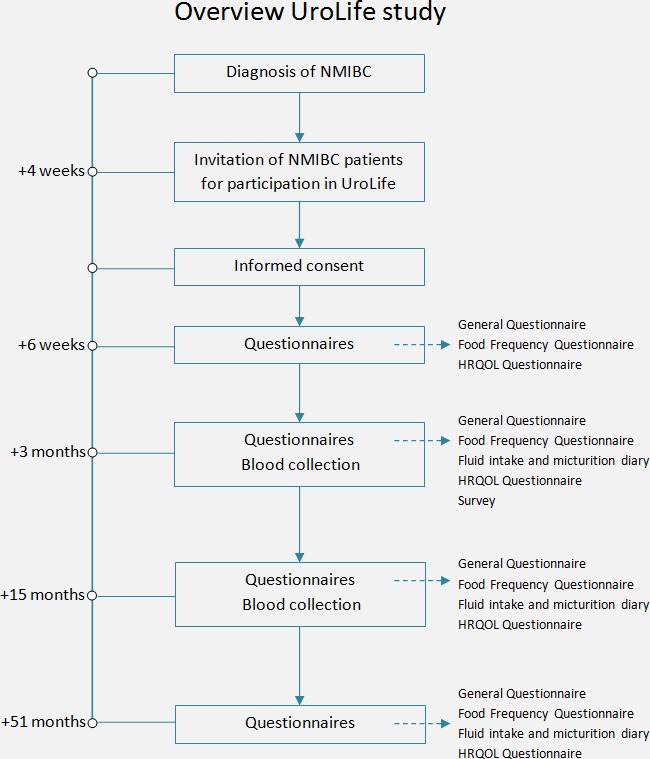

Participants are asked to complete self-administered web-based or paper-and-pencil-based questionnaires at 6 weeks (T6wk), 3 months (T3mo), 15 months (T15mo) and 51 months (T51mo) after diagnosis (figure 1, table 1). Web-based questionnaires are collected using the data collection tool of the Patient Reported Outcomes Following Initial treatment and Long term Evaluation of Survivorship registry.25 Follow-up telephone calls are made to non-responding participants and to respondents whose questionnaires have missing items.

Figure 1.

Timeline and study design of the UroLife study. HRQOL, health-related quality of life; NMIBC, non-muscle-invasive bladder cancer.

Table 1.

Overview of data collection in UroLife at the four time points

| Included topics | T6wk | T3mo | T15mo | T51mo | |

| Questionnaires | |||||

| Sociodemographic data | Date of birth, gender, living situation, marital status, country of birth of participant, father, mother, race, highest level of education, working history, occupational exposure | X | |||

| Anthropometry |

Height at diagnosis, weight 2 years before diagnosis, weight at age 18 years, average weight during adult life | X | |||

| Current body weight, waist and hip circumference | X | X | X | X | |

| Lifestyle |

Current and past smoking behaviour, environmental smoke exposure | X | X | X | X |

| SQUASH26 | X | X | X | X | |

| Frequency and amount of alcohol consumption during week and weekend days | X | X | X | X | |

| Changes in eating habits and reasons for/type of changes | X | X | X | ||

| Medical history |

Previously diagnosed with cancer, family history of cancer | X | |||

| Comorbidities, medication use, dietary supplement use | X | X | X | X | |

| Questions for females |

Menstruation, menopause, use of contraceptives, use of hormone replacement therapy | X | X | X | X |

| Pregnancy | X | ||||

| Diet | 163-item Food Frequency Questionnaire | X | X | X | X |

| HRQOL | EORTC QLQ-C3031 and EORTC QLQ-NMIBC2432 | X | X | X | X |

| Awareness risk factors and lifestyle advice | Awareness of cancer risk factors, received lifestyle advice, attitudes towards lifestyle advice | X | |||

| Four-day diary | Frequency micturition, amount and type of fluid intake | X | X | X | |

| Blood |

EDTA whole blood for DNA isolation | X | |||

| EDTA plasma, heparin plasma | X | X | |||

| Tissue | Formalin-fixed paraffin-embedded tissue of the primary tumour | X | |||

| Clinical data |

Disease characteristics, therapy | X | X | X | X |

| Recurrence and progression | X | X | |||

EORTC QLQ, European Organisation for Research and Treatment of Cancer Quality of Life Questionnaire; HRQOL, health-related quality of life; NMIBC, non-muscle-invasive bladder cancer; SQUASH, Short questionnaire to assess health-enhancing physical activity.

The baseline questionnaire contains questions on demographics (age, sex, ethnicity, education, living situation, occupation, marital status) and (family) history of cancer. All questionnaires collect information about height, body weight, amount and frequency of alcohol consumption during week and weekend days, smoking habits, comorbidities and the use of medication. Information on smoking habits is collected in detail, including age or date of starting and stopping smoking, number of cigarettes smoked per day, duration of smoking and passive exposure to smoking. Information about habitual physical activity is collected by using the previously validated short questionnaire to assess health-enhancing physical activity (SQUASH),26 which is fairly reliable and valid in an adult population.26–28 The SQUASH questionnaire assesses the average time, that is, number of days per week and hours and minutes per day, spent in commuting activities, leisure time activities, household activities and activities at work in a normal week in the past month. At T3mo, T15mo and T51mo, patients are also asked to measure and report their waist and hip circumference.

Habitual dietary intake is collected using a 163-item validated and reproducible self-administered food frequency questionnaire that was developed by Wageningen University.29 The questionnaire contains questions about the frequency of consumption of food products and the portion size during the previous year (T6wk) or the previous months (T3mo, T15mo, and T51mo). Frequency and portion size of consumed food products are multiplied to obtain their intake in grams per day. Nutrient intake is calculated using the Dutch Food Composition Database NEVO 2011.30 Information about fluid intake and micturition is collected with a 4-day diary at T3mo, T15mo and T51mo.

HRQOL is assessed at all four time points with the validated European Organisation for Research and Treatment of Cancer Quality of Life Questionnaire C30 (EORTC QLQ-C30)31 and a 24-item module for patients with NMIBC, i.e. the EORTC QLQ-NMIBC24.32 The EORTC QLQ-C30 contains five function scales (physical, role, cognitive, emotional and social functioning), three symptom scales (fatigue, nausea, pain and vomiting) and six single items (dyspnea, insomnia, loss of appetite, constipation, diarrhoea, and financial impact), all scored from 1 (not at all) to 4 (very much)) and a global health status scale with ranges from 1 (very poor) to 7 (excellent). The EORTC QLQ-NMIBC24 contains six scales (urinary symptoms, malaise, future worries, bloating and flatulence, sexual function and male sexual function) and five single items (intravesical treatment issues, sexual intimacy, risk of contaminating partner, sexual enjoyment, female sexual problems) scored from 1 (not at all) to 4 (very much). All scores will be linearly transformed to a 0–100 scale.

Furthermore, at T3mo patients are asked to report whether they are aware of possible risk factors for (bladder) cancer, received lifestyle advice from their physician and what their attitudes are towards physicians giving lifestyle advice.

Blood samples

Non-fasting blood samples are collected at T3mo and T15mo. At T3mo, 10 mL EDTA whole blood (for DNA isolation), 10 mL EDTA plasma and 10 mL heparin plasma are collected. At T15mo, 10 mL EDTA plasma and 10 mL heparin plasma are collected. Heparin plasma tubes are wrapped in aluminium foil to protect them from light. All blood samples are collected, processed and stored at −80°C locally in the participating hospitals according to a standard protocol before transportation on dry ice to the Radboud Biobank. The blood samples are stored in the Radboud Biobank at −80°C for future analyses of genetic and other biomarkers. Analysis of heparin plasma levels of nine biomarkers of fruit and vegetable consumption is planned. Concentration of six carotenoids (ie, alpha-carotene, beta-carotene, beta-cryptoxanthin, lutein, lycopene and zeaxanthin), alpha-tocopherol, beta- and gamma-tocopherol and retinol will be measured by High Performance Liquid Chromatography (Thermo Scientific Accela LC system; Thermo Fisher Scientific) and analysed by using ChromQuest 5.0, V.3.2.1 software (Thermo Fisher Scientific).

Tumour samples

From patients diagnosed with T1 NMIBC, tumour specimens will be collected in two batches in 2019 and 2021. Tumour blocks will be identified by using the PALGA Foundation and retrieved using the Dutch National Tissuebank Portal from the local pathology laboratories. Pathology review will be performed and tissue microarrays will be constructed. Molecular subtypes will be assessed by immunohistochemistry in 2021. As the development of a molecular classification system for NMIBC is still in progress and no consensus system is available yet,33 we will use the most suitable evidence-based subtyping method that will then be available.

Clinical data

For all patients with NMIBC, information about disease characteristics and therapy for the initial tumour is collected from the medical records by data managers of the NCR. Information about tumour characteristics includes incidence date, clinical Tumour, Node, Metastasis (cTNM) and post-surgical Tumour, Node, Metastasis (pTNM) stage,2 tumour grade, concomitant carcinoma in situ, multifocality, number of tumours and histology. With respect to therapy, information is collected on type of cystoscopy (white or blue light) and on TUR, that is, date of TUR, presence of detrusor in the surgical specimen and presence of lymphovascular invasion. Furthermore, data on local treatment (eg, intravesical chemotherapy, intravesical immunotherapy) with start and stop dates and, if applicable, on cystectomy (eg, date, type) are collected.

Data on clinical outcomes, that is, recurrence and progression, with dates of diagnosis, tumour characteristics and therapy is also collected from the medical records by data managers of the NCR. Information on vital status is collected by linkage with the Personal Records Database. All patients will be followed for at least 5 years.

Power considerations & Data analysis

Risk of recurrence (or progression) will be evaluated as time to first recurrence (or progression). The association of pre- and post-diagnostic lifestyle factors, as well as changes in lifestyle factors, with risk of recurrence and progression will be evaluated by estimating hazard ratios and 95% CI using Cox proportional hazards regression analyses. All analyses will be adjusted for age, gender, tumour characteristics and other known confounders. Analytical techniques for longitudinal data and multiple outcomes will also be explored and applied. Our power calculation is based on 1100 patients who will be followed for 5 years. For comparing the highest (n=275) versus lowest quartile (n=275) of a lifestyle factor (or vice versa), this study will be sufficiently powered (two-sided alpha=0.05, power 80%) to detect a HR of ≥1.5 or≥1.3 (or ≤0.7 or≤0.8) when assuming a 5-year recurrence risk of 31% or 78%,34 respectively.35 36 With an assumed loss to follow-up of 25% after 5 years, detectable hazard ratios will increase to ≥1.6 or≥1.4 (or ≤0.6 or≤0.7), respectively. Lower hazard ratios can be detected when lifestyle factors are modelled continuously.

The association of lifestyle factors with HRQOL will be evaluated using longitudinal mixed-model analyses, taking into account the within-subject variation in lifestyle and HRQOL over time and the between-subject variation. All analyses will be adjusted for age, gender, tumour characteristics and other known confounders. Since we expect that the between-subject variation in lifestyle and HRQOL will be much larger than the within-subject variation, most information will come from the association observed between subjects and not from the association observed within subjects over time, Therefore, our power calculation is based on a cross-sectional correlation at one time point. With 825 patients (assuming a loss to follow-up of 25%) and using 10 predictor variables, we have 80% power to detect a small correlation (Cohen’s f 2 of 0.02).37 38 Power will be higher when using repeated measurements over time, especially when there is within-subject variation of lifestyle factors and HRQOL over time.

Cohort status

Medical ethical approval was obtained on 17 January 2014. Patient recruitment started in May 2014. Between 8 May 2014 and 25 April 2017, 2133 patients with NMIBC initially diagnosed with Ta, T1 or Tis tumours have been identified and invited to participate in UroLife. Of these invited patients, 1193 patients agreed to participate and 77 dropped out before filling out the first questionnaires (response rate 52%). Since May 2017, recruitment of patients with T1 (but not Ta or Tis) tumours has continued and is still ongoing. We aim to recruit a total of at least 700 patients with T1 bladder cancer, and the projected date of recruitment completion is April 2021.

Discussion

The UroLife study is one of the largest multicentre prospective cohort studies on lifestyle and NMIBC outcomes worldwide. UroLife will provide new and comprehensive insights into whether lifestyle habits (or habit changes) are related to NMIBC outcomes and HRQOL, and whether these relations differ by tumour stage and molecular subtype. Unique features of UroLife are the recruitment of patients shortly after diagnosis, collection of extensive dietary, lifestyle, medical and HRQOL data at multiple time points after diagnosis, collection of blood (for DNA and biomarker analysis) and the availability of tumour tissue samples (for molecular classification).

As in many prospective cohort studies, non-participation may limit the generalisability of our findings. In addition, loss to follow-up may limit the validity of our findings. Information bias due to reliance on recall and self-report, or due to missing data, may be another potential limitation. Although our study is large, we intend to combine our data set in the future with other similar prospective studies in NMIBC to increase statistical power for subgroup analyses.

If the results of this study show that lifestyle factors are associated with clinical outcomes in NMIBC patients and these results are confirmed by other prospective studies or randomised trials, lifestyle recommendations and lifestyle interventions can be developed. Patients diagnosed with NMIBC could then be advised by their physician about their lifestyle and/or referred to a lifestyle intervention (eg, smoking cessation programme, exercise programme). Thus, our ultimate aim is to provide personalised evidence-based lifestyle advice to patients with NMIBC, also according to tumour stage and molecular subtype, to enable them to have an influence on their clinical outcome.

Ethics and dissemination

Patients who agree to participate in the study provide written informed consent. The findings from our cohort study will be disseminated through peer-reviewed scientific journals, and presentations at (inter)national scientific meetings. Patients will be informed about the progress and results of this study through biannual newsletters and through the website of the study (https://www.radboudumc.nl/trials/urolife) and of the bladder cancer patient association (https://www.blaasofnierkanker.nl/). Also, presentations will be given at contact days of the bladder cancer patient association.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We are grateful to all the patients who participate in this study and we would like to thank the following hospitals for their involvement in recruitment for the UroLife study: Amphia Ziekenhuis, Breda/Oosterhout (Dr DKE van der Schoot); Ziekenhuis Bernhoven, Uden (Dr AQHJ Niemer); Canisius-Wilhelmina Ziekenhuis, Nijmegen (Dr DM Somford); Catharina Ziekenhuis, Eindhoven (Dr EL Koldewijn); Deventer Ziekenhuis, Deventer (Dr PLM van den Tillaar); Elkerliek Ziekenhuis, Helmond (Dr EW Stapper†, Dr PJ van Hest); Gelre Ziekenhuizen, Apeldoorn/Zutphen (Dr DM Bochove-Overgaauw); Isala Klinieken, Zwolle (Dr E te Slaa); Jeroen Bosch Ziekenhuis, ‘s-Hertogenbosch (Dr JR Oddens; Dr S van der Meer); Meander Medisch Centrum, Amersfoort (Dr FS van Rey); Medisch Spectrum Twente, Enschede (Dr M Asselman); Maxima Medisch Centrum, Veldhoven/Eindhoven (Dr LMCL Fossion); Maasziekenhuis Pantein, Boxmeer (Dr E van Boven); Radboudumc, Nijmegen (Prof Dr JA Witjes); Rijnstate, Arnhem/Velp/Zevenaar (Dr CJ Wijburg); Slingeland Ziekenhuis, Doetinchem (Dr ADH Geboers); St. Anna Ziekenhuis, Geldrop (Dr A Sonneveld); Elisabeth-TweeSteden Ziekenhuis, Tilburg/Waalwijk (Dr PJM Kil); St Jansdal Ziekenhuis, Harderwijk (Drs WJ Kniestedt); VieCuri, Venlo (Dr G Yurdakul, Dr AHP Meier); Ziekenhuis Gelderse Vallei, Ede (Dr MDH Kortleve); Ziekenhuisgroep Twente, Almelo/Hengelo (Dr EB Cornel). In addition, we thank Ms Monique Eijgenberger for her assistance in data collection. We also thank the data managers and research assistants of the Netherlands Cancer Registry held by the Netherlands Comprehensive Cancer Organisation for inviting patients and collecting clinical data.

Footnotes

Contributors: AV, LAK, JAW, EK and KA contributed to the conception and design of the study. AV provides overall study management and coordinates the project. EW has contributed and LdG contributes to data collection. LdG, EW and AV drafted the manuscript. All authors have critically read and revised the manuscript. All authors approved the final version of the manuscript.

Funding: This work was supported by Alpe d’HuZes/Dutch Cancer Society (KUN 2013-5926) and Dutch Cancer Society (Project no. 11179). Sponsors were not involved in the study design nor will they be in the collection, analysis and interpretation of data, or in the publications that will result from this study.

Competing interests: None declared.

Patient consent for publication: Not required.

Ethics approval: The study protocol has been approved by the Committee for Human Research region Arnhem-Nijmegen (CMO 2013-494).

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

References

- 1. Bray F, Ferlay J, Soerjomataram I, et al. Global cancer statistics 2018: GLOBOCAN estimates of incidence and mortality worldwide for 36 cancers in 185 countries. CA Cancer J Clin 2018;68:394–424. 10.3322/caac.21492 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Babjuk M, Böhle A, Burger M, et al. EAU guidelines on non-muscle-invasive urothelial carcinoma of the bladder: update 2016. Eur Urol 2017;71:447–61. 10.1016/j.eururo.2016.05.041 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Cambier S, Sylvester RJ, Collette L, et al. Eortc nomograms and risk groups for predicting recurrence, progression, and disease-specific and overall survival in non-muscle-invasive stage Ta-T1 urothelial bladder cancer patients treated with 1-3 years of maintenance Bacillus Calmette-Guérin. Eur Urol 2016;69:60–9. 10.1016/j.eururo.2015.06.045 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Sievert KD, Amend B, Nagele U, et al. Economic aspects of bladder cancer: what are the benefits and costs? World J Urol 2009;27:295–300. 10.1007/s00345-009-0395-z [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Schmidt S, Francés A, Lorente Garin JA, et al. Quality of life in patients with non-muscle-invasive bladder cancer: one-year results of a multicentre prospective cohort study. Urol Oncol 2015;33 10.1016/j.urolonc.2014.09.012 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Ligibel J. Lifestyle factors in cancer survivorship. JCO 2012;30:3697–704. 10.1200/JCO.2012.42.0638 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Mehra K, Berkowitz A, Sanft T. Diet, physical activity, and body weight in cancer survivorship. Med Clin North Am 2017;101:1151–65. 10.1016/j.mcna.2017.06.004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. van Osch FH, Jochems SH, van Schooten F-J, et al. Quantified relations between exposure to tobacco smoking and bladder cancer risk: a meta-analysis of 89 observational studies. Int J Epidemiol 2016;45:857–70. 10.1093/ije/dyw044 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Cumberbatch MGK, Jubber I, Black PC, et al. Epidemiology of bladder cancer: a systematic review and contemporary update of risk factors in 2018. Eur Urol 2018;74:784–95. 10.1016/j.eururo.2018.09.001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Sun J-W, Zhao L-G, Yang Y, et al. Obesity and risk of bladder cancer: a dose-response meta-analysis of 15 cohort studies. PLoS One 2015;10:e0119313 10.1371/journal.pone.0119313 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Keimling M, Behrens G, Schmid D, et al. The association between physical activity and bladder cancer: systematic review and meta-analysis. Br J Cancer 2014;110:1862–70. 10.1038/bjc.2014.77 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. World Cancer Research Fund/American Institute for Cancer Research Continuous update project expert report 2018: diet, nutrition, physical activity and bladder cancer, 2018. Available: https://www.wcrf.org/dietandcancer

- 13. Crivelli JJ, Xylinas E, Kluth LA, et al. Effect of smoking on outcomes of urothelial carcinoma: a systematic review of the literature. Eur Urol 2014;65:742–54. 10.1016/j.eururo.2013.06.010 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Hou L, Hong X, Dai M, et al. Association of smoking status with prognosis in bladder cancer: a meta-analysis. Oncotarget 2017;8:1278–89. 10.18632/oncotarget.13606 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Westhoff E, Witjes JA, Fleshner NE, et al. Body mass index, diet-related factors, and bladder cancer prognosis: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Bladder Cancer 2018;4:91–112. 10.3233/BLC-170147 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Kluth LA, Xylinas E, Crivelli JJ, et al. Obesity is associated with worse outcomes in patients with T1 high grade urothelial carcinoma of the bladder. J Urol 2013;190:480–6. 10.1016/j.juro.2013.01.089 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Wyszynski A, Tanyos SA, Rees JR, et al. Body mass and smoking are modifiable risk factors for recurrent bladder cancer. Cancer 2014;120:408–14. 10.1002/cncr.28394 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Xu T, Zhu Z, Wang X, et al. Impact of body mass on recurrence and progression in Chinese patients with TA, T1 urothelial bladder cancer. Int Urol Nephrol 2015;47:1135–41. 10.1007/s11255-015-1013-1 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. van der Heijden AG, Witjes JA, Recurrence WJA. Recurrence, progression, and follow-up in Non–Muscle-Invasive bladder cancer. European Urology Supplements 2009;8:556–62. 10.1016/j.eursup.2009.06.010 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Sjödahl G, Lauss M, Lövgren K, et al. A molecular taxonomy for urothelial carcinoma. Clin Cancer Res 2012;18:3377–86. 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-12-0077-T [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Patschan O, Sjödahl G, Chebil G, et al. A molecular pathologic framework for risk stratification of stage T1 urothelial carcinoma. Eur Urol 2015;68:824–32. 10.1016/j.eururo.2015.02.021 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Jung A, Nielsen ME, Crandell JL, et al. Quality of life in non-muscle-invasive bladder cancer survivors. Cancer Nurs 2019;42 10.1097/NCC.0000000000000606 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Mohamed NE, Gilbert F, Lee CT, et al. Pursuing quality in the application of bladder cancer quality of life research. Bladder Cancer 2016;2:139–49. 10.3233/BLC-160051 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Gopalakrishna A, Longo TA, Fantony JJ, et al. Lifestyle factors and health-related quality of life in bladder cancer survivors: a systematic review. J Cancer Surviv 2016;10:874–82. 10.1007/s11764-016-0533-8 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. van de Poll-Franse LV, Horevoorts N, van Eenbergen M, et al. The patient reported outcomes following initial treatment and long term evaluation of survivorship registry: scope, rationale and design of an infrastructure for the study of physical and psychosocial outcomes in cancer survivorship cohorts. Eur J Cancer 2011;47:2188–94. 10.1016/j.ejca.2011.04.034 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Wendel-Vos GCW, Schuit AJ, Saris WHM, et al. Reproducibility and relative validity of the short questionnaire to assess health-enhancing physical activity. J Clin Epidemiol 2003;56:1163–9. 10.1016/S0895-4356(03)00220-8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. de Hollander EL, Zwart L, de Vries SI, et al. The squash was a more valid tool than the OBiN for categorizing adults according to the Dutch physical activity and the combined guideline. J Clin Epidemiol 2012;65:73–81. 10.1016/j.jclinepi.2011.05.005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Wagenmakers R, van den Akker-Scheek I, Groothoff JW, et al. Reliability and validity of the short questionnaire to assess health-enhancing physical activity (squash) in patients after total hip arthroplasty. BMC Musculoskelet Disord 2008;9:141 10.1186/1471-2474-9-141 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Siebelink E, Geelen A, de Vries JHM. Self-Reported energy intake by FFQ compared with actual energy intake to maintain body weight in 516 adults. Br J Nutr 2011;106:274–81. 10.1017/S0007114511000067 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. NEVO NEVO-tabel: Dutch food composition database. Den Haag: RIVM/Voedingscentrum; 2011. [Google Scholar]

- 31. Aaronson NK, Ahmedzai S, Bergman B, et al. The European organization for research and treatment of cancer QLQ-C30: a quality-of-life instrument for use in international clinical trials in oncology. JNCI Journal of the National Cancer Institute 1993;85:365–76. 10.1093/jnci/85.5.365 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Blazeby JM, Hall E, Aaronson NK, et al. Validation and reliability testing of the EORTC QLQ-NMIBC24 questionnaire module to assess patient-reported outcomes in non-muscle-invasive bladder cancer. Eur Urol 2014;66:1148–56. 10.1016/j.eururo.2014.02.034 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Chandrasekar T, Erlich A, Zlotta AR. Molecular characterization of bladder cancer. Curr Urol Rep 2018;19:107 10.1007/s11934-018-0853-5 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Sylvester RJ, van der Meijden APM, Oosterlinck W, et al. Predicting recurrence and progression in individual patients with stage TA T1 bladder cancer using EORTC risk tables: a combined analysis of 2596 patients from seven EORTC trials. Eur Urol 2006;49:466–77. 10.1016/j.eururo.2005.12.031 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Dupont WD, Plummer WD. Power and sample size calculations. A review and computer program. Control Clin Trials 1990;11:116–28. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Dupont WD, Plummer WD. Ps: power and sample size calculation. Available: http://biostat.mc.vanderbilt.edu/wiki/Main/PowerSampleSize [Accessed 16 Jan 2019].

- 37. Faul F, Erdfelder E, Buchner A, et al. Statistical power analyses using G*Power 3.1: tests for correlation and regression analyses. Behav Res Methods 2009;41:1149–60. 10.3758/BRM.41.4.1149 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Faul F, Erdfelder E, Buchner A, et al. G*Power: statistical power analyses for windows and MAC. Available: http://www.gpower.hhu.de [Accessed 16 Jan 2019].

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.