Abstract

Introduction

Venoarterial extracorporeal membrane oxygenation (VA-ECMO) is widely used to support the most severe forms of cardiogenic shock (CS). Nevertheless, despite extracorporeal membrane oxygenation (ECMO) use, mortality still remains high (50%). Moderate hypothermia (MH) (33°C–34°C) may improve cardiac performance and decrease ischaemia–reperfusion injuries. The use of MH during VA-ECMO is strongly supported by experimental and preliminary clinical data.

Methods and analysis

The Hypothermia-Extracorporeal Membrane Oxygenation (HYPO-ECMO) study is a multicentre, prospective, controlled randomised trial between an MH group (33°C≤T°C≤34°C) and normothermia group (36°C≤T°C≤37°C). The primary endpoint is all-cause mortality at day 30 following randomisation. The study will also assess as secondary endpoints the effects of targeted temperature management strategies on (1) mortality rate at different time points, (2) organ failure and supportive treatment use and (3) safety. All intubated adults with refractory CS supported with VA-ECMO will be screened. Exclusion criteria are patients having undergone cardiac surgery for heart transplantation or left or biventricular assist device implantation, acute poisoning with cardiotoxic drugs, pregnancy, uncontrolled bleeding and refractory cardiac arrest.

Three-hundred and thirty-four patients will be randomised and followed up to 6 months to detect a 15% difference in mortality. Data analysis will be intention to treat. The differences between the two study groups in the risk of all-cause mortality at day 30 following randomisation will be studied using logistic regression analysis adjusted for postcardiotomy setting, prior cardiac arrest, prior myocardial infarction, age, vasopressor dose, Sepsis-related Organ Failure Assessment (SOFA) score and lactate at randomisation.

Ethics and dissemination

Ethics approval has been granted by the Comité de Protection des Personnes Est III Ethics Committee. The trial has been approved by the French Health Authorities (Agence Nationale de la Sécurité du Médicament et des Produits de Santé). Dissemination of results will be performed via journal articles and presentations at national and international conferences. Since this study is also the first step in the constitution of an ‘ECMO Trials Group’, its results will also be disseminated by the aforementioned group.

Trial registration number

Keywords: cardiogenic shock, ECMO VA, hypothermia

Strengths and limitations of this study.

This is a translational-minded trial strongly supported by experimental and preliminary clinical data regarding hypothermia in cardiogenic shock.

This is a pragmatic trial using simple inclusion criteria that would ensure an easy implementation of the results if positive.

The HYPO-ECMO will be conducted in the majority of the centres using venoarterial extracorporeal membrane oxygenation in France.

To ensure a high inclusion rate, comprehensive biological data are not collected.

Introduction

Venoarterial extracorporeal membrane oxygenation (VA-ECMO) is a widely and increasingly used technique to support the most severe forms of cardiogenic shock (CS).1 The leading cause of CS is myocardial infarction (MI).2 CS affects approximately 5%–7% of patients with MI. Nevertheless, despite extracorporeal membrane oxygenation (ECMO) use, mortality remains alarmingly high (50%),2 3 thus underscoring the importance of improving short-term survival, which remains unacceptably low. Unfortunately, very few recent advances have been achieved in the treatment of CS, with the exception of ECMO for refractory CS. Refractory CS is conventionally defined as CS associated with refractory hypotension and an increased need for vasopressor and inotrope support, along with lactic acidosis and organ failure. Of importance, three randomised controlled studies are currently ongoing, aimed at defining the place of VA-ECMO in the management of non-refractory CS (NCT03813134, NCT03637205 and the ANCHOR study in France)

As recently suggested, therapeutic hypothermia may play a key role in the medical treatment of CS.4 Therapeutic hypothermia is now a standard part of treatment for out-of-hospital cardiac arrest.5 It allows decreasing the metabolic rate by 5%–7% per degree reduction of body temperature.4 A concomitant decrease in carbon dioxide production, oxygen consumption, as well as glucose use is also observed.6 Moreover, hypothermia is known to affect the cardiovascular (CV) system in multiple ways, many of which could prove advantageous in CS, especially after post-MI. In a study conducted in a dog model of acute post-MI CS, hypothermia maintained at 32°C was associated with a decrease in systemic oxygen consumption, heart rate, left ventricular end-diastolic pressure, as well as myocardial oxygen consumption, while stroke work/volume and cardiac output were maintained along with improved survival time.7 This latter study was recently validated in an ischaemic CS pig model in which acute mortality was also reduced in the therapeutic hypothermia group.8 The positive inotropic effects of hypothermia in the heart are seemingly related to an increase in contraction amplitudes, action potential duration, calcium transients, fractional sarcoplasmic reticulum calcium release and calcium content in individual ventricular myocytes.9

Furthermore, therapeutic hypothermia has multiple and potentially beneficial physiological consequences independent of its direct CV effects.4 10 Indeed, recent studies conducted in animal models suggest that ischaemia–reperfusion (I/R) injury may be reduced after emergency revascularisation for acute MI.4 Given that myocardial ischaemia and systemic hypoperfusion are characterised by an increase in oxygen radical production and a heightened inflammatory response, the induction of therapeutic hypothermia may thus provide systemic protection by blunting the production of proinflammatory cytokines, as well as impairing macrophage and neutrophil phagocytic function, thereby decreasing the severity of damage and dysfunction associated with MI.4 Other beneficial effects of hypothermia include the reduction of I/R injury in other organ systems, a reduction in endothelial cell apoptosis and oxidative stress as well as an increase in urine output.4

The use of hypothermia in patients with CS has been typically limited to cardiac surgery complicated by CS, with available literature notably limited to a few highly selected cases or series, most of which were either under-powered, non-randomised and/or in a uncontrolled setting.4 Zobel et al 11 reported the effects of moderate hypothermia (MH) in 20 patients with CS after cardiac arrest and concluded that in CS, moderate therapeutic hypothermia was associated with an increase in systemic vascular resistance leading to decreased vasopressor use and likely resulting in lower oxygen consumption. In a study of 40 patients with CS following MI, Fuernau et al found that MH did not improve cardiac power index at 24 hours. Nevertheless, the study was not powered for mortality and positive effects of hypothermia were not limited to cardiac effects.12 Consequently, a well-designed and well-powered RCT is currently needed in order to provide sufficient evidence to support the clinical use of therapeutic hypothermia in patients with post-MI refractory CS.

Patients with CS treated with ECMO exhibit severe cardiac failure associated with severe I/R injury and a proinflammatory profile, leading to increased nitric oxide production and subsequent severe vasoplegia and multiple organ failure. Therefore, adding hypothermia in the very early phase of ECMO may alleviate the deleterious effects of ischaemia–reperfusion.13 Preliminary data have demonstrated that MH during CS is well tolerated. Yet, the induction of hypothermia induces numerous changes throughout the body, such as shivering, hyperglycaemia, electrocardiographic changes, mild coagulopathy and increased sensitivity to infection. Nowadays, several strategies have been developed to minimise these potential side effects since the introduction of hypothermia in cardiac arrest.6 Indeed, no associated severe side effects have been described in previous studies especially when compared with the high severity of CS. Using a porcine model of CS treated with VA-ECMO, Vanhuyse et al have recently demonstrated that MH compared with normothermia leads to a marked decrease in vasopressor use, improves vascular reactivity, improves cardiac function and is well tolerated with no observable side effect.14 However, to date, there has yet to be a randomised study of therapeutic hypothermia in patients with post-MI refractory CS treated with VA-ECMO.

Hypothesis

The HYPO-ECMO study hypothesises that an early use of hypothermia aimed at protecting the body from I/R injury and protecting the heart may improve short-term mortality in VA-ECMO-treated patients with CS.

Methods and analysis

Study design

The HYPO-ECMO study is a multicentre randomised controlled trial. This open trial is conducted in patients with refractory CS treated with VA-ECMO. Patients are randomised in either the experimental ‘hypothermia group’ (temperature between 33°C≤T°C≤34°C) or in the control ‘normothermia group’ (36°C≤T°C≤37°C).

Objectives and endpoints

The primary study objective was to determine whether early MH (33°C≤T°C≤34°C) is superior to normothermia (36°C≤T°C≤37°C) in patients with refractory CS treated with VA-ECMO with regard to 30-day mortality. The primary endpoint of the study is all-cause mortality at day 30 following randomisation (ie, 30-day mortality).

Secondary objectives were to determine whether early MH (33°C≤T°C≤34°C) is superior to normothermia (36°C≤T°C≤37°C) in patients with refractory CS treated with VA-ECMO using endpoints listed in table 1.

Table 1.

Secondary objectives and endpoints

| Secondary objectives | Secondary endpoints |

| Mortality during hospitalisation and up to 180 days | All-cause mortality at 48 hours and at days 7, 60 and 180 |

| VA-ECMO weaning time | VA-ECMO duration |

| Adverse cardiovascular events | Composite endpoint of death, cardiac transplant, escalation to LVAD and stroke at days 30, 60 and 180 |

| Necessity of fluid and vasopressor support | Cumulated amount of administered fluids and duration of vasopressor use in ICU |

| Lactate clearance | Duration to normalisation of lactate |

| Duration of organ failure | Number of days alive without organ failure(s), defined with the SOFA score and its components (respiratory, liver, coagulation and renal), between inclusion, D7 and D30 |

| Mechanical ventilation support use | Duration of mechanical ventilation and the number of days between inclusion and days 30, 60 and 180, alive without mechanical ventilation |

| Renal replacement therapy use | Number of days alive without renal replacement therapy and number of days between inclusion and days 30, 60 and 180, without renal replacement therapy |

| Duration of ICU stay and total duration of hospitalisation | Duration of ICU stay and of hospitalisation |

| Risk of bleeding | Number of severe and moderate bleeding complications estimated using the BARC classification15 and the number of packed red blood cells transfused under VA-ECMO |

| Risk of sepsis | Infection probability: pulmonary, blood and VA-ECMO cannulae |

BARC, bleeding academic research consortium; ICU, intensive care unit; LVAD, left ventricul assist device; VA-ECMO, venoarterial extracorporeal membrane oxygenation.

Patients

The targeted population of this trial consists of patients with CS treated by VA-ECMO. Consecutive eligible subjects, meeting the detailed inclusion and exclusion criteria (table 2), will be considered for the study.

Table 2.

Trial inclusion and exclusion criteria

| Inclusion criteria | Exclusion criteria |

| Age≥18 years | VA-ECMO after cardiac surgery for heart or lung–heart transplantation or ventricular assist device implantation |

| Intubated patients with cardiogenic shock treated with VA-ECMO | VA-ECMO for acute poisoning with cardiotoxic drugs |

| Patients affiliated or beneficiaries of a social security scheme | Pregnancy |

| Uncontrolled bleeding (bleeding despite medical intervention (surgery or drugs) | |

| Implantation of VA-ECMO under cardiac massage with a duration of cardiac massage of ≥45 min | |

| Out-of-hospital refractory cardiac arrest | |

| Participation in another interventional research involving therapeutic modifications | |

| Cerebral deficit with fixed dilated pupils | |

| Patient moribund on the day of randomisation | |

| Irreversible neurological pathology | |

| Minor patients | |

| Patients under tutelage |

VA-ECMO, venoarterial extracorporeal membrane oxygenation.

Enrolment

All intubated patients with refractory CS supported with VA-ECMO will be screened. Patients with CS treated with VA-ECMO in the intensive care unit meeting all of the inclusion and non-inclusion criteria will be enrolled in the study. The inclusion and randomisation of the patients will be performed after VA-ECMO implementation. VA-ECMO will be initiated in accordance to local practices with flow settings to ensure sufficient tissue perfusion. Inclusion and study intervention will be performed as soon as possible during the first 6 hours (preferably 4 hours) after VA-ECMO initiation. After eligibility verification, complete clinical examination and informed consent process, patients will be randomised in either the intervention group (MH group) or the control group (normothermia).

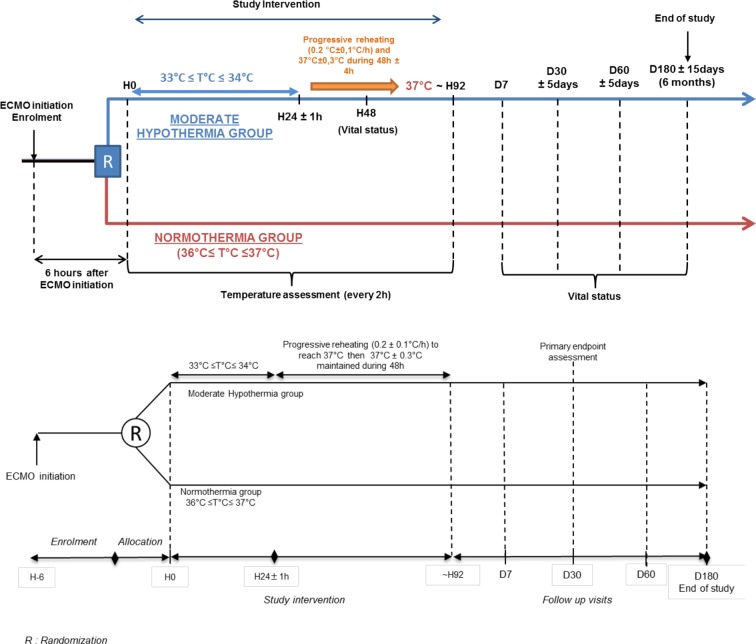

Hypothermia group

MH will be induced as soon as possible after VA-ECMO implementation and randomisation. MH is induced using the heat controller of the VA-ECMO circuit and other classical temperature management if necessary (external or internal technique). The temperature is maintained between 33°C≤T°C≤34°C during 24±1 hours followed by a progressive reheating (0.2°C±0.1°C/hour) to reach 37°C. Temperature at 37°C±0.3°C is maintained during 48±4 hours after having reached 37°C.

Although rare, the potential physiological effects of hypothermia that can appear based on literature data are shivering, modifications in blood gas management, hyperglycaemia, electrocardiographic changes, mild coagulopathy and increased sensitivity to infection. In such case, appropriate management will be performed according to the most current recommendations.

In cases of uncontrolled bleeding, hypothermia will be stopped and resumed as soon as the bleeding is controlled for a total duration of 24 hours of MH. Tolerance to hypothermia is ensured with the cautious use of sedation and eventually with the use of a paralysing agent in case of shivering.

Normothermia group

The Extracorporeal Life Support Organisation (ELSO) recommends, ‘Temperature can be maintained at any level by adjusting the temperature of the water bath. Temperature is usually maintained close to 37°C’. A large number of patients requiring VA-ECMO experience a cardiac arrest prior to ECMO implantation. Regarding such patients, it is now recommended to maintain the patients between 33 and 36 degrees. Therefore, for these patients, the temperature will be maintained at 36°C.

Central temperature will be measured every 2 hours in each group in accordance with local practice. All medications or treatments are authorised during the trial. The treatment protocol is summarised in figure 1.

Figure 1.

HYPO-ECMO study: Treatment protocol and follow up.

Follow-Up

Any subject can withdraw his/her participation to this study at any time and for any reason.

The investigator can permanently end a subject's participation in the research for any reason affecting the subject's safety or which would be in the subject's best interests. Serious adverse events associated with the use of hypothermia have been reported such as shivering, modifications in blood gas management, hyperglycaemia, electrocardiographic changes, mild coagulopathy and increased sensitivity to infection.

Ethical considerations

This study follows the principles of the Declaration of Helsinki and is in accordance with good clinical practices and French regulation. The trial has been approved by the French Health Authorities (Agence Nationale de la Sécurité du Médicament et des Produits de Santé (ANSM)) and the appropriate ethics committee (Comité de Protection des Personnes (CPP) Est III (N° CPP 16.04.03)).

Information provided to patients

In the particular context of this protocol, the persons included in this research may not be able to receive information regarding the study and give their consent before the implementation of the protocol due to their medical condition and emergency. In such instance, if a member of the patient's family or support person is present, this person is informed and consent is gathered, according to article 1122-1-3 of the French Health Code.

In the absence of a family member or support person, the investigator will include the patient in the study and obtain the consent of the family member or support person as soon as possible.

The patient's consent for the continuation of the trial will be obtained when his/her condition allows (online supplementary file). The patient, family member or support person is free to refuse participation in the study and may at any time and for whatever reason withdraw his or her consent.

bmjopen-2019-031697supp001.pdf (159.8KB, pdf)

Twenty French ECMO teams/heart centres are currently participating in the HYPO-ECMO study. To this day, approximately three hundred patients have been included and randomised in the trial. Data collection is expected to be completed by November 2019.

Data quality and regulatory issues

Confidentiality

All personal and medical information is collected and shared in accordance to medical confidentiality, as well as French and European regulations regarding data protection.

Furthermore, all data recorded in the secured database for statistical analysis are pseudonymised (first letter of first name and last name, patient code in the study and partial birth date). The study data are sent to the sponsor via secured channels (electronic case report form (eCRF) and secure SharePoint).

After the end of the trial, study database and documents will be archived by the investigator sites and sponsor in accordance with French and European regulations.

Monitoring of the study

The sponsor of the study—the Nancy University Hospital—will monitor (quality control and audits) the study in all sites to ensure that compliance with the Protocol and applicable regulations is maintained and that the data are collected in a timely, accurate and complete manner. All suspected unexpected serious adverse reactions will be declared by the sponsor, within the legal time frame, to the ANSM and the ethics committee.

The sponsor will provide yearly safety reports to the French regulatory agency and the ethics committee. An independent data and safety monitoring board has been established to monitor patient safety and evaluate benefits–risks balance during the study.

Patient and public Involvement

The patients and public were not involved.

Statistical analysis/ data management

Clinical data management and statistical analysis will be carried out at the ‘Centre d’Investigation Clinique, Plurithématique’ department (CIC 1433), CHRU-Nancy.

Randomisation

Remote online randomisation will be provided, based on a prespecified list of randomly mixed block sizes (of which investigators will be blinded to) and stratified on centres, via a secure web access to an electronic data capture (EDC) solution. This list was prepared and verified, in accordance with CIC procedure, by two statisticians. Individual and secured access will be provided to remote authorised users to perform the random allocation of patients.

Data management

Data will be collected via an eCRF. Individual and secured remote access will be provided to authorised users (investigators and clinical trial technicians).

Data consistency tests will be implemented in the EDC accordingly to the data validation plan to facilitate the capture of comprehensive and accurate data. Warnings regarding data inconsistencies and completeness will be displayed in real time during data acquisition, and further discrepancies will be sent to the investigational centres to refine data accuracy.

Safety data (serious adverse events) reconciliation will performed with the pharmacovigilance database, at evenly spaced time points during the course of the study, in order to reconcile the databases.

After final review by the study's scientific committee, the database will be locked and provided as SAS 9.4 software (SAS Institute, Cary, NC, USA) files to the statistical team for analysis under the leadership of the trial’s methodologist.

Sample size

We anticipated that mortality in cardiogenic patients supported with VA-ECMO will be 50% (based both on ELSO data, Combes data (Crit Care Med. 2008 May;36(5):1404–11), as well as personal data from the study's principal investigator (database of 150 patients)).

Considering a total event risk (for the primary endpoint) of 50% in the control group, a sample size of n=167 patients/group will detect a 15% absolute difference in favour of the VA-ECMO group using a chi-square test with an 80% power and considering a two-sided global alpha level of 5% using the LanDe Mets method with O’Brien-Fleming boundary for one interim analysis after inclusion of two-third of the patients.

Statistical analysis

Statistical analysis for the primary endpoint

The differences between the two study groups (ie, intervention and controls) relative to the risk of all-cause mortality at day 30 following randomisation will be studied using logistic regression adjusted for the postcardiotomy setting, prior cardiac arrest, prior MI, age, vasopressor dose, SOFA score and lactate at randomisation. Resulting associations will be illustrated by means of Kaplan-Meier survival curves, and a similarly adjusted HR will also be provided as well as crude estimates of ORs and HRs.

Statistical analysis for the secondary endpoints

For the secondary analysis of a) all-cause mortality at 48 hours and at days 7, 60, 180, and b) the composite endpoint of death, cardiac transplant, escalation to LVAD, stroke at days 30, 60, 180, the same analysis strategy will be performed as for the primary endpoint.

An unpaired t-test will be performed, after testing of the variables for normality of distribution of continuous outcomes. Linear regression adjusted for the same variables as those depicted in the primary endpoint analysis will also be performed. Importantly, in case of non-normal distributions, non-parametric tests will be used.

Chi-square tests (or Fisher's exact test in the event of an insufficient number of expected patients in the 2×2 cell) will be performed for categorical outcomes other than those described above and odd-ratios will be provided for illustrative purposes.

An interaction analysis will be performed using the following list of possible predictive markers: postcardiotomy setting, prior cardiac arrest, prior MI, age, vasopressor dose, SOFA score and lactate at randomisation.

Degrees of statistical significance

A bilateral p value lower than 4.9% will be considered significant for the final analysis. A p value threshold lower than 5% is mandatory, given the planned interim analyses to ensure a global alpha level of 5%.

Trial status

This trial is registered with the last protocol version being number six dated on 11 September 2017. Patient inclusions started in October 2016 and are expected to end in October 2019. Follow-up will last 6 months for each patient. Inclusions and follow-up are expected to end in October 2019 and April 2020, respectively.

Conclusions

The HYPO-ECMO study is an important and innovative randomised controlled trial that will assess, for the first time in human study, whether MH during 24 hours can decrease the mortality rate in refractory CS treated with VA-ECMO. Considering the secondary endpoints ‘escalation to LVAD or heart transplantation’ and given the high expected mortality, the opportunity to reach LVAD and heart transplantation will also be considered as a success.

The results should provide further perspective for years to come. In addition, better long-term outcomes could also be expected while ECMO use is still increasing worldwide. The findings may have important consequences for therapeutic strategies targeted at reducing the morbidity, mortality and cost of CS management.

Supplementary Material

Footnotes

Contributors: BL and NG conceived and designed the study. BL, NG, XL and LM developed the study design and revised the protocol (last V.7.1 on 25 April 2018). BL, XL and NG sought funding and ethical approval. AJ, BL, NG, XL and LM contributed to the writing of the manuscript and read and approved the final manuscript.

Funding: This work was funded by the French Ministry of Health.

Competing interests: None declared.

Patient consent for publication: Not required.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

References

- 1. Levy B, Bastien O, Karim B, et al. . Experts' recommendations for the management of adult patients with cardiogenic shock. Ann Intensive Care 2015;5:52 10.1186/s13613-015-0052-1 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Thiele H, Zeymer U, Neumann F-J, et al. . Intraaortic balloon support for myocardial infarction with cardiogenic shock. N Engl J Med 2012;367:1287–96. 10.1056/NEJMoa1208410 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Thiele H, Ohman EM, Desch S, et al. . Management of cardiogenic shock. Eur Heart J 2015;36:1223–30. 10.1093/eurheartj/ehv051 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Stegman BM, Newby LK, Hochman JS, et al. . Post-Myocardial infarction cardiogenic shock is a systemic illness in need of systemic treatment: is therapeutic hypothermia one possibility? J Am Coll Cardiol 2012;59:644–7. 10.1016/j.jacc.2011.11.010 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Nielsen N, Wetterslev J, Cronberg T, et al. . Targeted temperature management at 33 degrees C versus 36 degrees C after cardiac arrest. mild therapeutic hypothermia to improve the neurologic outcome after cardiac arrest. N Engl J Med 2013;369:2197–206.24237006 [Google Scholar]

- 6. Polderman KH. Mechanisms of action, physiological effects, and complications of hypothermia. Crit Care Med 2009;37:S186–202. 10.1097/CCM.0b013e3181aa5241 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Boyer NH, Gerstein MM. Induced hypothermia in dogs with acute myocardial infarction and shock. J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg 1977;74:286–94. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Götberg M, van der Pals J, Olivecrona GK, et al. . Mild hypothermia reduces acute mortality and improves hemodynamic outcome in a cardiogenic shock pig model. Resuscitation 2010;81:1190–6. 10.1016/j.resuscitation.2010.04.033 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Shutt RH, Howlett SE. Hypothermia increases the gain of excitation-contraction coupling in guinea pig ventricular myocytes. Am J Physiol Cell Physiol 2008;295:C692–700. 10.1152/ajpcell.00287.2008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Han Y-S, Tveita T, Prakash YS, et al. . Mechanisms underlying hypothermia-induced cardiac contractile dysfunction. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol 2010;298:H890–7. 10.1152/ajpheart.00805.2009 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Zobel C, Adler C, Kranz A, et al. . Mild therapeutic hypothermia in cardiogenic shock syndrome. Crit Care Med 2012;40:1715–23. 10.1097/CCM.0b013e318246b820 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Fuernau G, Beck J, Desch S, et al. . Mild hypothermia in cardiogenic shock complicating myocardial infarction. Circulation 2019;139:448–57. 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.117.032722 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Zhao L, Luo L, Chen J, et al. . Utilization of extracorporeal membrane oxygenation alleviates intestinal ischemia-reperfusion injury in prolonged hemorrhagic shock animal model. Cell Biochem Biophys 2014;70:1733–40. 10.1007/s12013-014-0121-3 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Vanhuyse F, Ducrocq N, Louis H, et al. . Moderate hypothermia improves cardiac and vascular function in a pig model of ischemic cardiogenic shock treated with veno-arterial ECMO. Shock 2017;47:236–41. 10.1097/SHK.0000000000000712 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Kikkert WJ, van Geloven N, van der Laan MH, et al. . The prognostic value of bleeding academic research consortium (BARC)-defined bleeding complications in ST-segment elevation myocardial infarction: a comparison with the TIMI (Thrombolysis In Myocardial Infarction), GUSTO (Global Utilization of Streptokinase and Tissue Plasminogen Activator for Occluded Coronary Arteries), and ISTH (International Society on Thrombosis and Haemostasis) bleeding classifications. J Am Coll Cardiol 2014;63:1866–75. 10.1016/j.jacc.2014.01.069 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

bmjopen-2019-031697supp001.pdf (159.8KB, pdf)