Abstract

Background

Person-centred care (PCC) is now recognised as an important component of healthcare quality. However, a lack of consensus of its most critical elements and absence of a global measure of person-centredness has limited the ability to evaluate the impact of implementation.

Aim

Introduce a measurable construct for PCC that yields improvement in quality, patient loyalty and staff engagement.

Methods

Informed by scientific evidence and the voices of patients, families and healthcare professionals, the Person-Centered Care Certification Programme was developed as a comprehensive measure of PCC (Person-Centered Care Certification is a registered trademark of Planetree Registered in the US Patent and Trademark Office). Ten years after its development, the programme was redesigned to offer a more complete evaluative framework to focus organisations’ PCC efforts and better understand their impact. Drawing on the National Academy of Medicine’s Guiding Framework for Patient and Family Engaged Care, five drivers for excellence were identified that delineate the critical inputs required to create and maintain a culture of PCC. Aligned within the drivers are 26 interventions that connect staff to purpose, promote partnership with patients and families, engage individuals in care and promote continuous learning. A multimethod evaluation approach assesses how effectively these PCC strategies have been executed within the organisation and to understand their impact on the human experience of care.

Results

The Person-Centered Care Certification Programme is associated with improvements in patient experience, patient loyalty and staff engagement.

Conclusion

The structured Certification framework can help organisations identify PCC improvement opportunities, guide their implementation efforts, and better understand the impact on patient and staff outcomes. Tested in cultures around the world and across the care continuum, the framework has proven effective in converting PCC into a definable, measurable and attainable goal. This paper outlines how the programme was designed, the measurable benefits derived by organisations and lessons learnt through the process.

Keywords: organizational culture, patient-centred care, accreditation, evaluation methodology, healthcare quality improvement

Background

Quality in healthcare has been described as the right care at the right time in the right place, every time.1 In countries around the world and in settings across the healthcare continuum, patients and family members express a desire for a higher standard.2 3 Individuals who have participated in patient/family focus groups have consistently described quality healthcare experiences as featuring caring interactions, choice, responsiveness, family involvement, clear communication and coordination among team members.4

Person-centred care (PCC; also referred to as patient-centred care, patient and family centred care and patient and family engaged care) integrates the right care at the right time in the right place with these patient and family-defined priorities.

In the 18 years since the Institute of Medicine’s Crossing the Quality Chasm report first identified PCC as one of six determinants of high-quality healthcare,5 important progress has been made globally toward creating a more person-centred healthcare system. Fuelled by a growing body of evidence linking PCC to a range of quality outcomes,6–9 the concept has been incorporated into practice,10 11 healthcare policy12 13 and reimbursement models. It has generated interest among researchers who have studied the impact of patient and family engagement strategies,14 and it has fuelled the emergence of patient experience officers15 16 and patient and family advisors in healthcare centres around the world.17 18 PCC has also gained prominence in organisational mission statements, strategic plans and marketing efforts.

Yet the impact of these inputs to create a more person-centred healthcare system has been difficult to determine with any precision. This stems from two critical gaps:

A lack of clarity of the most crucial elements necessary to implement and sustain an organisational culture of PCC.19–23

The absence of a standardised way to evaluate person-centredness in all its complexity and multidimensionality.

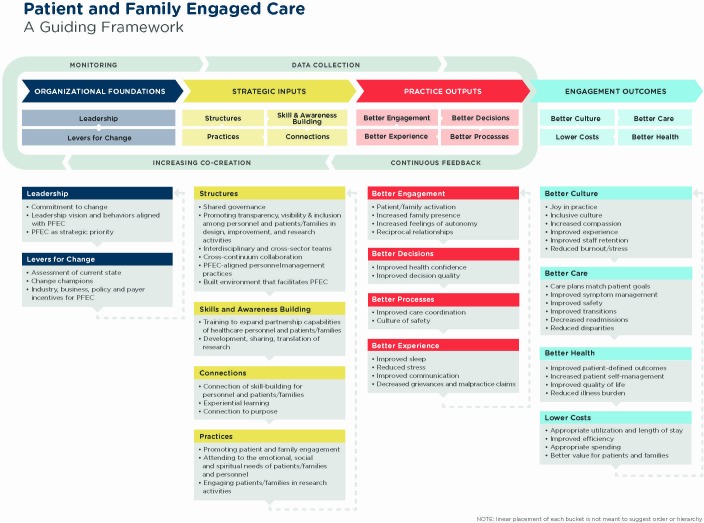

Great strides have been made in identifying key PCC culture change strategies. In particular, the National Academy of Medicine’s Guiding Framework for Patient and Family Engaged Care offers a clearly defined pathway of foundational elements that set the stage for sustainable change. It goes on to identify specific strategic inputs for establishing a culture of patient and family engaged care.24 The framework is grounded in scientific evidence and the lived experience of patients, their family caregivers, practitioners and health system leaders. It was created to reduce the ambiguity around the most impactful patient and family engagement approaches. The framework illustrates how these approaches build on each other to improve outcomes that matter to all stakeholders in the healthcare enterprise, that is, the Quadruple Aim outcomes of better health, better care, lower costs and better culture (see figure 1).

Figure 1.

NAM guiding framework for patient and family engaged care. NAM, National Academy of Medicine.

This effort to establish greater consensus around the most high impact PCC strategies opens the door to address the second prevalent gap: the absence of a standardised way to evaluate the impact of these strategies. Without a viable alternative, PCC measurement strategies have been haphazard and inconsistent.25 They have been largely reliant on proxy measures like the Consumer Assessment of Healthcare Providers and Systems (CAHPS) patient experience survey or net promoter scores, which have failed to capture the complexities of organisational culture, the experience of healthcare professionals and how these work in concert to impact patient and family care, outcomes and experiences.

Aim

The Person-Centered Care Certification Programme was developed to address this gap through the introduction of a structured, results-oriented and measurable framework for evaluating organisational performance relative to PCC.

Methods

Informed by scientific evidence and the lived experience of patients, families and healthcare professionals, the Person-Centered Care Certification Programme was launched by Planetree International in 2007 as a comprehensive and holistic measure of PCC (Planetree International is a not-for-profit organisation that pioneered the development of person-centred care approaches around the world by considering the healthcare experience through the perspectives of patients, family caregivers and healthcare professionals). Though developed by Planetree, the measure was designed to be applicable to all healthcare organisations, regardless of setting or formal affiliation with Planetree. Ten years after its development, the programme was redesigned to align with the most current evidence of best practices in PCC. The goal was to offer a more complete evaluative framework that would focus and accelerate organisations’ PCC efforts and their impact.

To guide this work, Planetree convened an international multistakeholder advisory group inclusive of patient and family advocates, healthcare executives, practitioners and other accreditation, quality and improvement experts.26 Drawing on their own experiences, PCC literature and the National Academy of Medicine’s 2017 Guiding Framework for Patient and Family Engaged Care, these advisors met over the course of 18 months to develop the certification framework. The group identified five thematic drivers and 26 specific inputs (or criteria) that delineate the critical structural, operational and practice inputs required to create and maintain a culture of PCC. A multimethod evaluation approach was then developed to assess the degree to which the PCC inputs are effectively executed within an organisation and the impact of doing so on the human experience of care.

A number of avenues were established to continually vet the advisory group’s efforts for relevance and feasibility. Planetree engaged its own Patient and Family Partnership Council to ensure programme improvements retained the distinct focus on what matters most to patients and families. In addition, as criteria were recommended, a public comment period was launched globally to collect broader stakeholder input into the advancement and evolution of the standards. As adjustments to the assessment process were considered, they were tested via real-time, small scale tests of change to evaluate usefulness and operational practicality. For example, programme developers were able to test specific focus group questions, as well as the viability of incorporating spontaneous patient, family and staff interviews into facility tours.

Performance framework

The resulting framework developed through this process now constitutes the evaluation standards for healthcare organisations applying for Certification. As such, it also serves as an implementation roadmap for organisations working toward excellence in PCC.

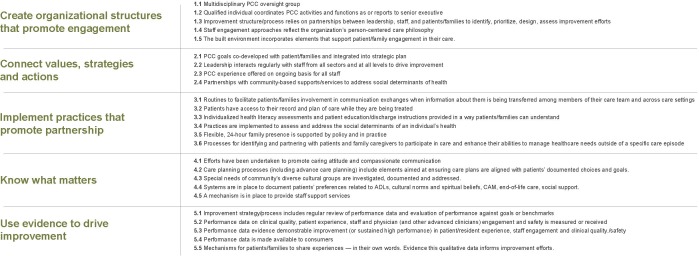

The five drivers for excellence depict, at a high level, what it takes organisationally to advance PCC. They establish the multifaceted nature of this work and highlight the need to support a coordinated approach where organisational strategies, structures, practices and measures are aligned around PCC. The five drivers are: (1) create organisational structures that promote engagement; (2) connect values, strategies and actions; (3) implement practices that promote partnership; (4) know what matters; and (5) use evidence to drive improvement. These drivers map directly to the evidence-based National Academy of Medicine Guiding Framework for Patient and Family Engaged Care.14

The drivers are supported by criteria.27 These criteria indicate the key inputs that work together to harness the voices of key stakeholders, connect staff to purpose, engage patients and families in their care and promote continuous learning and measurement of outcomes that matter. The criteria (shown here in their abbreviated form) are intended to standardise expectations of what it means to be person-centred and what it takes operationally to achieve that desired state (see figure 2).

Figure 2.

Person-Centered Care Certification Programme criteria.

A key consideration in developing the criteria was balancing the need to be sufficiently directive to ensure a consistent understanding of the desired future state while not being so prescriptive so as to block innovation and adaptations to meet the unique needs of specific organisations and/or populations. Furthermore, as an international certification programme, the requirements need to be flexible enough to accommodate cultural nuances and differences in national policies, rules and regulations.

To achieve this delicate balancing act, the 26 criteria are written to express the intent of the requirement. This focus on the intent versus a rigidly defined required way of achieving the intent preserves ample flexibility for how the desired result can be achieved. Supplementary documentation is provided to applicants that presents operational examples from different care settings to further clarify the expectations and to provide a clear path forward for implementation.

For instance, criterion 2.2. requires that ‘[L]eadership interacts regularly with staff from all sectors and at all levels to drive improvement in the organization’. How this requirement is met may vary in different organisations. The evaluation methodology supports this variation because organisations are assessed on how well they are meeting the intent of purposeful leadership interactions versus a specific input, such as executive rounds. In addition to preserving flexibility, this approach also guards against implementation of specific practices merely to meet a standard rather than to truly drive change.

Evaluation process

From its inception, a defining attribute of the Person-Centered Care Certification Programme has been its multimethod approach to evaluation. Evidence gleaned from traditional documentation reviews are supplemented with data from focus groups and interviews with key stakeholders. While retaining this defining element of the evaluation process, significant changes to the validation methodology ushered in a more objective, logical and transparent evaluation process.

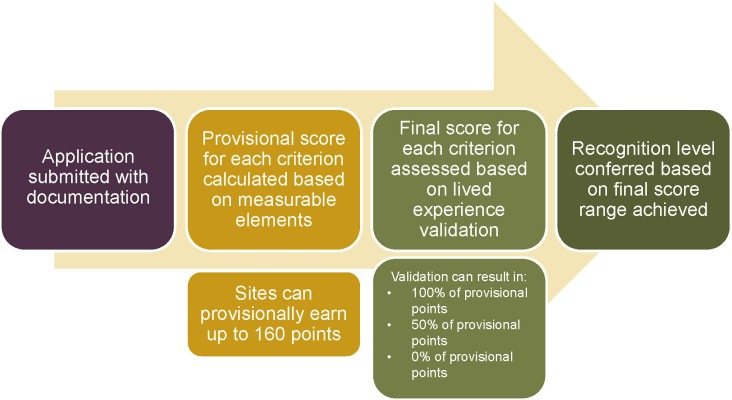

In the redesigned evaluative framework, the criteria are supported by measurable elements that outline the objectively assessable components of each criterion. These measurable elements form the basis for the certification programme’s scoring methodology. A score is calculated based on performance against these measurable elements. This initial score is determined based on the review of a written application, supportive documentation and performance measures. Up to 160 points can be earned. The 160 points are equally distributed among the five drivers; however, not all the criteria are weighted the same. The online supplementary file 1 presents each of the criteria with their associated point value.Point weights for the criteria range from 2 points to 15 points.

bmjoq-2019-000737supp001.pdf (104.2KB, pdf)

Ultimately, this initial score is validated by a unique lived experience evidence component of the evaluation process. Fitting for a person-centred certification, patients, family caregivers and staff have the final word on how well the organisation is meeting the spirit and intent of each of the 26 certification criteria. Their personal stories and insights illuminate the degree to which PCC strategies have been effectively executed and how doing so has made an impact on the human experience of care.

An applicant’s score remains provisional until validated via this ‘lived experience evidence’. This qualitative data is collected during a multiday site visit, which is a key element of the certification evaluation process. Approaches used to gather lived experience evidence include focus groups, interviews, meetings and structured observation. When rating the lived experience evidence, site surveyors consider:

Frequency and consistency of comment type, for example, expressions of satisfaction versus dissatisfaction.

Specificity of feedback, for example, degree to which expressions of (dis)satisfaction are accompanied by personal examples that left an impression (positive or negative).

Importance, for example, match between satisfaction and prioritisation.

Based on these findings, adjustments are made to the provisional score (see figure 3) to ensure that the final performance score reflects not only the best intentions of the organisation as documented in the written application, but most importantly, the real-life experiences of those who interact with the healthcare system. Site surveyors draw directly on the voices of patients, family caregivers and staff describing their personal experiences to substantiate how the organisation was rated on the criteria.

Figure 3.

Person-Centered Care Certification evaluation process.

This part of the process is particularly valued by teams pursuing recognition, as expressed by Dr Zuber M Shaikh, PhD of Gold-Certified Dr Sulaiman Al Habib Medical Group in Riyadh, Saudi Arabia: “The Person-Centered Care Certification was the first time that we have witnessed a survey process which takes into account the involvement of staff from all the different levels of the organization, patients and their families and community leaders”.

Recognition

Certification is ultimately conferred by an independent Person-Centered Care Certification Committee comprised of patient advocates, healthcare executives from Certified sites around the world, and other healthcare quality experts.28 The level of Certification awarded is based on the organisation’s final score: Bronze (60%–74% of the total possible points earned); Silver (75%–89% of the total possible points earned); Gold (90% or more of the total possible points earned). These recognition tiers offer the opportunity for organisations at varying stages of PCC implementation to set attainable shorter term targets while making progress toward a longer term goal of Gold Certification. The recognition term is 3 years, however, a team can opt to reapply before the term is up if they feel they are positioned to achieve a higher level of recognition.

Results

Tested in cultures around the world and across the care continuum, the Person-Centered Care Certification framework has proven effective in converting PCC into a definable, measurable and attainable goal. Healthcare organisations that have achieved Gold Certification have consistently demonstrated that an organisational culture emphasising quality, compassion and partnership results in better care, increased patient loyalty and greater staff engagement.

To date, 139 organisations in 12 countries have achieved Bronze, Silver or Gold-level Certification.29 This includes acute care hospitals, behavioural health hospitals, outpatient health centres and clinics, long-term care communities, rehabilitation hospitals, hospice settings physician offices and integrated health systems.

A challenge inherent in the programme’s global and cross-continuum scope is a lack of standardisation in how participating organisations measure and report on key performance indicators (KPIs). Where possible, performance of comparable organisations against industry benchmarks is used to demonstrate patterns of improvement. For instance, Gold Certified hospitals in the USA significantly outperform the national average on the likelihood to recommend question of the Hospital Consumer Assessment of Healthcare Providers and Systems (HCAHPS) survey. In addition, while many different staff engagement and satisfaction measures are used (limiting comparability of outcomes), most Certified organisations have documented improvements in staff opinion surveys and retention rates.

Until programme uptake increases to a level wherein similar-type data can be collected from larger comparable cohorts all using the same KPIs, efforts to substantiate that the Certification framework yields improvements in patient loyalty, staff engagement and quality are dependent on trends observed across multiple sites. For instance:

Examples of increased patient loyalty

Northern Westchester Hospital (NWH) in Mt. Kisco, New York (part of the Northwell Health system) has seen significant gains across several HCAHPS patient satisfaction metrics. Most notable is the 37-point improvement NWH achieved in ‘Likelihood to Recommend’ since beginning its journey to Certification.30

At Sharp Coronado Hospital (part of the San Diego, California-based Sharp Healthcare System), patient satisfaction increased from less than the 50th percentile to close to the top percentile in the nation since initiating its PCC implementation effort.31

At Enloe Medical Center in Chico, California, patient experience scores jumped from the 49th to the 80th percentile.32

At Bellevue Medical Center outside of Beirut, Lebanon, patient experiences scores exceed 95%.33

Examples of greater staff engagement

NewYork Presbyterian/Westchester Division, a behavioural health hospital in White Plains, New York that is part of the NewYork Presbyterian system, reports the highest employee engagement scores of any hospital within the system.34

Enloe Medical Center’s staff engagement scores increased from the 19th to the 51st percentile.

Examples of better care

At Loch Lomond Villa, a long-term care community in New Brunswick, Canada, the PCC journey resulted in an easing up of rigid institutional approaches for meals, bathing and sleep. This more flexible approach resulted in a 43% reduction in the use of dietary supplements, fewer residents on antipsychotic medications and 60% fewer bed alarms.35

At Dr. Sulaiman Al Habib Medical Group in Riyadh, Saudi Arabia, implementation of the Person-Centered Care Certification standards has resulted in an improvement in bedside shift report compliance from 64.2% to 88.6%, Care Partner programme compliance from 62.6% to 87.4% and has contributed to a better employee experience.36

Discussion

Since the programme’s launch, considerable knowledge about common challenges and barriers to PCC has been gained by monitoring performance trends, for instance criteria associated most frequently with point reductions. In the redesigned programme’s first year of operation, programme staff closely monitored trends for where and why provisional points were most frequently deducted. The average differential between the provisional score and the final score (following lived experience evidence adjustments) was a nine point reduction. Common reasons for points being deducted included less robust patient/family involvement on key organisational structures than indicated in the application and a lack of patient and family awareness of key engagement opportunities. A frequent disconnect between written documentation and the lived experience was where comprehensive policies had been developed for involving patients and families in key exchanges of information about their care (criterion 3.1), sharing the medical record (criterion 3.2), and involving family caregivers as members of the care team (criterion 3.6). Direct input from patients and families indicated teams were falling short, however, on executing these strategies. This illuminates the importance of teams putting in place quality check systems to ensure that policies for patient and family engagement approaches work not only on paper, but most importantly in practice. Experience also suggests that encouraging organisations early on in the PCC journey to engage patients and families as partners on steering committees, work teams, and improvement projects helps accelerate teams’ Certification efforts.

The performance framework does come with some limitations. For one, the programme emphasises organisational culture as the key driver of excellence in person-centred care. Others,37 however, have asserted that culture is one of a number of factors that would facilitate or impede adoption of this type of system change. It may be perceived that with its emphasis on organisational culture, the Certification framework is too narrow a lens to fully evaluate what drives achievement in PCC, and that culture overshadows elements from the broader context and/or at the individual level that would also be key indicators for successful adoption.

Also, worth noting is that the drivers and criteria describe processes as opposed to outcomes. This is aligned with the perspective of evaluating patients’ and staff members’ experiences versus their satisfaction,25 however, the exclusion of outcome-based standards creates an evidence gap. The lack of universally employed and recognised PCC outcomes-based measures presents a challenge for the field. Moving toward an evaluative approach that measures outcomes directly (vs assessing the practices and processes expected to drive improved outcomes) will strengthen the case for PCC implementation.

It will be incumbent on programme leaders to continue exploring strategies for demonstrating a clear and compelling return on the investment of pursuing Certification. One potential approach may be to collect predata and postdata on an existing tool that would be applicable across cultures and across settings of care, such as the Caring Culture Survey, which measures a perceptions of caring within a healthcare organisation through both a direct and non-direct care perspective.38

Conclusion

Planetree embarked on this effort with the goal of developing an approach for objectively evaluating person-centred care implementation efforts. While many lessons were learnt along the way, the most important take-away is this: when thoughtfully approached and structured, our experience suggests that PCC can, in fact, be evaluated in a standardised and objective way.

Experience to date with the Person-Centered Care Certification framework indicates that both as a concrete implementation roadmap and as a recognition vehicle that shines a light on what excellence in PCC looks like in practice, the Certification programme is a viable tool for converting person-centred excellence into a definable goal that can be set, tracked and achieved.

Footnotes

Twitter: @SaraPlanetree

Contributors: SG, Vice President of Knowledge Management, Planetree International is the primary author responsible for the overall content. KJ, Senior Vice President, Global Services, Planetree International shaped the outline for the manuscript. S. Frampton, PhD, President, Planetree International reviewed the manuscript. C. Davies, Director Certification Services, Planetree International reviewed the manuscript.

Funding: The authors have not declared a specific grant for this research from any funding agency in the public, commercial or not-for-profit sectors.

Competing interests: None declared.

Patient consent for publication: Not required.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

References

- 1.Nowak NA, Rimmasch H, Kirby A, et al. . Right care, right time, right place, every time. Healthc Financ Manage 2012;66:82–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Valentine N, Darby C, Bonsel GJ. Which aspects of non-clinical quality of care are most important? Results from WHO's general population surveys of “health systems responsiveness” in 41 countries. Soc Sci Med 2008;66:1939–50. 10.1016/j.socscimed.2007.12.002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Droz M, Senn N, Cohidon C. Communication, continuity and coordination of care are the most important patients' values for family medicine in a fee-for-services health system. BMC Fam Pract 2019;20:19 10.1186/s12875-018-0895-2 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Harrison J. What patients want: a multi-country qualitative study 2018. unpublished manuscript.

- 5.Institute of Medicine Crossing the quality chasm: a new health system for the 21st century. National Academy Press, 2001. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Doyle C, Lennox L, Bell D. A systematic review of evidence on the links between patient experience and clinical safety and effectiveness. BMJ Open 2013;3:e001570 10.1136/bmjopen-2012-001570 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Beach MC, Keruly J, Moore RD. Is the quality of the patient-provider relationship associated with better adherence and health outcomes for patients with HIV? J Gen Intern Med 2006;21:661–5. 10.1111/j.1525-1497.2006.00399.x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Bertakis KD, Azari R. Patient-Centered care is associated with decreased health care utilization. J Am Board Fam Med 2011;24:229–39. 10.3122/jabfm.2011.03.100170 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Jaén CR, Ferrer RL, Miller WL, et al. . Patient outcomes at 26 months in the patient-centered medical home national demonstration project. Ann Fam Med 2010;8 Suppl 1:S57–67. 10.1370/afm.1121 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Moore L, Britten N, Lydahl D, et al. . Barriers and facilitators to the implementation of person-centred care in different healthcare contexts. Scand J Caring Sci 2017;31:662–73. 10.1111/scs.12376 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Aboumatar HJ, Chang BH, Al Danaf J, et al. . Promising practices for achieving patient-centered hospital care: a national study of high performing US hospitals. Med Care 2015;53:758–67. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Matthews D. Bill 46: an act respecting the care provided by health care organizations. Toronto, ON, Canada: Legislative Assemble of Ontario, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- 13.World Health Organization People-centred health care: a policy framework. World Health Organization, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Frampton SB, Guastello S, Hoy L, et al. . Harnessing evidence and experience to change culture: a guiding framework for patient and family engaged care. NAM Perspectives 2017;7 10.31478/201701f [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Burns J. Chief experience officers push patients to forefront. Manag Care 2015;24:51–3. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Carlson B. The rise of the chief experience officer. Physician Leadersh J 2015;2:16–21. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Carman KL, Dardess P, Maurer M, et al. . Patient and family engagement: a framework for understanding the elements and developing interventions and policies. Health Aff 2013;32:223–31. 10.1377/hlthaff.2012.1133 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Goodridge D, Isinger T, Rotter T. Patient family advisors’ perspectives on engagement in health-care quality improvement initiatives: power and partnership. Health Expect 2018;21:379–86. 10.1111/hex.12633 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Scholl I, Zill JM, Härter M, et al. . How do health services researchers understand the concept of patient-centeredness? Results from an expert survey. Patient Prefer Adherence 2014;8:1153–60. 10.2147/PPA.S64051 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Vest JR, Bolin JN, Miller TR, et al. . Review: Medical Homes: “Where You Stand on Definitions Depends on Where You Sit”. Med Care Res Rev 2010;67:393–411. 10.1177/1077558710367794 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Scholl I, Zill JM, Härter M, et al. . An integrative model of Patient-Centeredness – a systematic review and concept analysis. PLoS One 2014;9:e107828 10.1371/journal.pone.0107828 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Epstein RM, Fiscella K, Lesser CS, et al. . Why the nation needs a policy push on patient-centered health care. Health Aff 2010;29:1489–95. 10.1377/hlthaff.2009.0888 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Epstein RM, Street RL. The values and value of patient-centered care. Ann Fam Med 2011;9:100–3. 10.1370/afm.1239 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Frampton and others Harnessing evidence and experience to change culture 2017.

- 25.Larson E, Sharma J, Bohren MA, et al. . When the patient is the expert: measuring patient experience and satisfaction with care. Bull World Health Organ 2019;97:563–9. 10.2471/BLT.18.225201 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Planetree International Person-Centered care certification program manual. Planetree International, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Planetree International Planetree certification criteria. Available: https://www.planetree.org/certification-resources/planetree-certification-criteria?hsCtaTracking=c39fc971-a46a-4aec-a120-3e20b4ad74b7%7C1401ea50-c0f8-4755-8ac5-c937dadaeb81 [Accessed 26 Apr 2019].

- 28.Planetree International Who we are. Person-Centered care certification Committee. Available: https://www.planetree.org/who-we-are [Accessed 26 Apr 2019].

- 29.Planetree person centered care certified sites. Available: https://www.planetree.org/hubfs/Downloads/ Planetree_CertifiedSites_Final_Interactive%202.1.19.pdf [Accessed 26 Apr 2019].

- 30.Northern Westchester Hospital Achieves 37-Point Gain in “Likelihood to Recommend”. Available: https://www.planetree.org/certification-resources/northern-westchester-hospital-achieves-37-point-gain-in-likelihood-to-recommend [Accessed 26 Apr 2019].

- 31.How sharp Coronado transformed outcomes and Reputation through Person-Centered care. Available: https://www.planetree.org/certification-resources/how-sharp-coronado-transformed-outcomes-reputation-through-person-centered-care [Accessed 26 Apr 2019].

- 32.Todd J. Personal email 2018.

- 33.How Bellevue medical center became the first hospital in Lebanon to introduce shared medical records, open visitation and bedside shift report. Available: https://www.planetree.org/certification-resources/bellevue-medical-center [Accessed 26 Apr 2019].

- 34.How a psychiatric hospital became a system-wide leader in employee engagement and creating a culture of safety. Available: https://www.planetree.org/certification-resources/how-newyork-presbyterian-westchester-division-implemented-a-transformational-patient-centric-model-for-behavioral-health [Accessed 26 Apr 2019].

- 35.How Loch Lomond Villa, Inc. is meeting the growing demand for long-term care and exceeding expectations for nursing home life. Available: https://www.planetree.org/certification-resources/loch-lomond-villa-case-study [Accessed 26 Apr 2019].

- 36.Zuber MS, Shaikh AA, Al Omari A. The impact of Planetree certification on a nationally and internationally accredited healthcare facility and its services. The impact of Planetree certification on a nationally and internationally accredited healthcare facility and its services. Research Review International Journal of Multidisciplinary 2018;03:318–32. [Google Scholar]

- 37.Greenhalgh T, Wherton J, Papoutsi C, et al. . Beyond adoption: a new framework for theorizing and evaluating Nonadoption, abandonment, and challenges to the scale-up, spread, and sustainability of health and care technologies. J Med Internet Res 2017;19:e367 10.2196/jmir.8775 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Mensik J, Leebov W, Steinbinder A. Survey development: caregivers help define a tool to measure cultures of care. J Nurs Adm 2019;49:138–42. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

bmjoq-2019-000737supp001.pdf (104.2KB, pdf)