Abstract

Introduction

Migraine is a primary cause of disability worldwide, particularly affecting young adults and middle-aged women. Although multiple clinical trials and systematic reviews have suggested that acupuncture could be effective in treating acute migraine attacks, the methodologies in academic studies and commonly applied practices vary greatly. This study protocol outlines a plan to assess and rank the effectiveness of the different acupuncture methods in order to develop a prioritised acupuncture-based treatment regimen for acute migraine attacks.

Objective

To compare the efficacy of different acupuncture methods and conventional medicinal methods in the treatment of acute migraine attacks.

Methods and analysis

Six databases will be searched, including MEDLINE, EMBASE, the Cochrane Central Register of Controlled Trials, China National Knowledge Infrastructure, Chinese Science and Technology Periodical Database and Wanfang Database from inception to 31 August 2019. The primary outcomes will be assessed using metrics for intensity and duration (in hours) of pain post-treatment. Bayesian network meta-analysis will be conducted using WinBUGS V.1.4.3. Finally, we will use the Grading of Recommendations Assessment, Development and Evaluation System to assess the quality of evidence.

Ethics and dissemination

The results will be disseminated through peer-reviewed publication. Since no private and confidential patient data will be contained in the reporting, there are no ethical considerations associated with this protocol.

PROSPERO registration number

CRD42019126472.

Keywords: migraine disorders, acupuncture, network meta-analysis, systematic review, protocol

Strengths and limitations of this study.

This study will be the first ever Bayesian network meta-analysis comparing acupuncture-based methods in the treatment of acute migraine.

The quality of evidence will be assessed by the Grading of Recommendations Assessment, Development, and Evaluation system.

Our research approach will focus upon acupuncture methods, but without any discussion about the associated acupoint selection or analysis of the specific details of acupuncture techniques.

We will only retrieve data from Chinese and English databases which could limit available data or result in language bias.

Introduction

Description of the condition

Migraine is a neurological disease characterised by recurrent attacks of unilateral headache of a pulsating quality and moderate or severe intensity, aggravated by routine physical activity and associated with nausea and/or photophobia and phonophobia.1 Untreated or unsuccessfully treated attacks last 4–72 hours and have a serious impact on patient quality of life. In accordance with the seminal 2016 Global Burden of Neurological Disorders Study,2 migraine is the main globally scaled cause of disability, particularly affecting young adults and middle-aged women. Furthermore, migraine has ranked as the second largest contributor of disability-adjusted life years among neurological disorders.

Although the exact causes and dynamics of migraine among groups and individuals remain unclear, it is now widely accepted that migraine has a strong genetic basis that should be viewed as part of the complex systems forming the brain network and involving multiple cortical, subcortical and brainstem regions.3 Despite increasing awareness and clinically based research of migraine, relatively limited progress has been made in therapeutics to clearly understand and control symptoms effectively. Triptans, ergotamine derivatives, non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs and opioids are widely considered effective in treating acute migraine attacks.4 Nevertheless, the potential and reported side effects of these treatment courses should not be underestimated because they can be severe. Besides potentially inducing gastrointestinal and cardiovascular disorders,5 6 pain levels worsen when patients consume analgesics or triptan drugs too frequently or for too long, resulting in abuse of these substances or eventual reduction in the effectiveness of these drugs resulting in a vicious cycle.7 Side effects of substance abuse drive patients to seek non-pharmacological therapies. Therefore, developing safe and effective alternative therapies for acute migraine attacks is of utmost priority.

Description of the intervention

Acupuncture is one of the main and commonly used therapies in traditional Chinese medicine (TCM). Acupuncture is accomplished by inserting needles into skin at specific areas of the body (acupoints) or by making insertions along central meridians at certain depths under the skin.8 This produces a sensation of ‘de qi’ simultaneously, which is often described as a sour, numb radiating or distending pain.

The characteristics of sensations can be enhanced by concurrently using electrical stimulation (electroacupuncture (EA)), heat (moxibustion acupuncture (MA)), or frequent manual stimulation (traditional manual acupuncture (TA)).9 EA combines needling and electric stimulation. The stimulator connects needles at two points and releases pulses of electric current to generate continuous stimulation when the needles are retained in the skin. MA uses applied heating of the needle by burning mugwort on the needle handle after its insertion into the body. Fire needling (FA) is an acupuncture method that punctures and removes a red-hot needle from a point in the skin. According to the theory of TCM acupuncture, FA has the functions of warming the meridians and dispelling cold, clearing and activating meridians and collaterals. This study aims to investigate these methods. The selected acupoints are based on the TCM acupuncture, and they are mainly ashi points, local or distal acupoints along meridians, specific acupoints and comprehensively selected acupoints.10

TCM philosophies focus on manoeuvres meant to balance life energy, but the dynamics of the mechanism is difficult to assess from a strict standpoint of scientific study.11 However, biochemical evidence has shown that acupuncture increases the activity of the opioidergic system and induces the release of serotonin, dopamine, neurotrophins and nitric oxide, and the consequences could effectively treat disorders like migraine.9 Although exact mechanisms are unresolved, acupuncture is still a widely used and accepted approach for migraine treatment. According to a US-based survey, 9.9% of patients who underwent treatment for migraine or other headaches used acupuncture to help alleviate symptoms.12 In recent years, controlled clinical trials on acute or chronic migraine have increased in number and experimental breadth.13–16 Furthermore, several Cochrane systematic reviews have confirmed the effectiveness and safety of acupuncture.17 18 However, heretofore very few or negligible rigorous systematic reviews have assessed the role of acupuncture in association with the treatment or any other related factors of acute migraine. Most of the literature only considers evidence obtained by comparing acupuncture methods and medicine or sham acupuncture methods and has failed to compare results of all existing acupuncture methods. Therefore, determining the best acupuncture methods for relieving pain is intractable. In this study, we will choose TA, EA, MA and FA as the objects evaluated by the TCM theory.

Objectives

Objectives of this systematic review and network meta-analysis are to: (1) compare and rank all acupuncture methods in terms of efficacy in the treatment of migraine; and (2) produce a credible evidence comparing efficacy of acupuncture methods and conventional-based medicine (CM) for migraine. We expect that the outcomes will provide evidence to clarify the current controversy surrounding acupuncture, and thus provide an important summary of the literature-based references to help clinical practices and health policy decision-makers.

Methods

This protocol will be conducted according to the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses Protocols (PRISMA-P) statement and the Checklist of Items to Include When Reporting a Systematic Review Involving a Network Meta-analysis.19 20 The research has been registered on PROSPERO (online supplementary file 1 for PRISMA-P checklist).

bmjopen-2019-031043supp001.pdf (93.2KB, pdf)

Eligibility criteria

Types of studies

We will only use data from randomised controlled trials published in English or Chinese without any regional restrictions. The first period of randomised cross-over trials will be included. Literature reviews, animal studies, retrospective studies, case reports and studies with unavailable data will be excluded.

Types of participants

Participants will include adults (≥18 years old) suffering from acute migraine according to the definition by the Headache Classification Subcommittee of the International Headache Society1 or any other accepted diagnostic guidelines. Participants with migraines of a definite identified cause such as intracranial lesions will be excluded from our analyses. Results will not be analysed according to sex or nationality.

Types of intervention

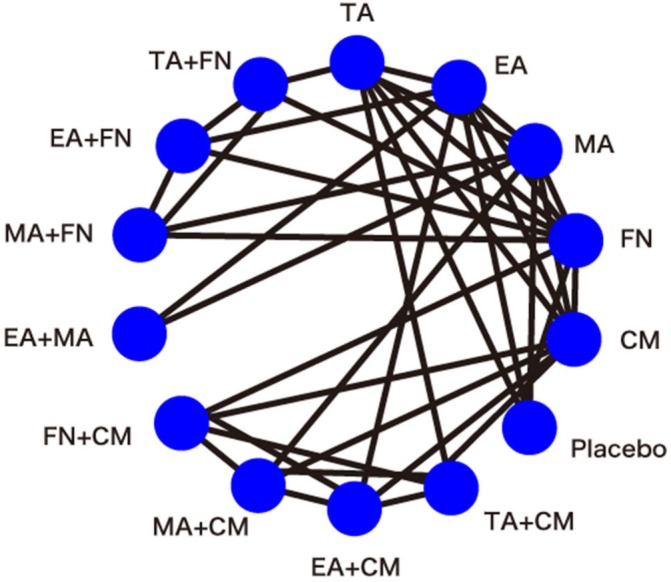

Our selection of acupuncture methods for analysis will include TA, EA, MA, FA, a combination of any two of these methods or combinations of any of these acupuncture methods with CM, regardless of acupoint selection or needling techniques. In accordance with the outlined Standards for Reporting Interventions in Clinical Trials of Acupuncture,21 rationales related to acupuncture will be limited to TCM, neither the period when the research had been conducted nor the duration of the research will be restricted in the analyses. Therefore, non-traditional ear acupuncture and wrist-ankle acupuncture will be excluded. Moreover, dry needle, laser acupuncture, bee venom acupuncture, acupotomy, as well as any irrelevant treatments, including blood-letting therapy, cupping, and herbal medicine will be excluded from our data set and analyses. Figure 1 illustrates the network plot of all possible direct comparisons.

Figure 1.

Network plot of all possible direct comparisons (CM, conventional-based medicine; EA, electroacupuncture; FN, fire needling; MA, moxibustion acupuncture; TA, traditional manual acupuncture).

Types of control groups

Different acupuncture methods will form the basis for the control group, and which will include both a placebo group as well as a CM group. Trials comparing two acupoint selections or acupuncture manipulations will be excluded.

Types of outcome measures

Studies reporting one or more of the following outcomes will be included.

Primary outcomes

A main objective of this review will be the evaluation of the analgesic effects of different acupuncture methods in the treatment of acute migraine attacks. Hence, the primary desirable outcomes include pain reduction within 2 hours of treatment and reductions in the duration of pain post-treatment.

Levels of pain intensity were measured through headache score rating scales such as the visual analogue scale and numerical rating scale22 wherein each scale would be used to assess outcomes from the time of treatment conclusion till 2 hours post-treatment. Many studies have examined the corresponding relationships with time; hence, our study will select the score or other applicable measure 2 hours after treatment. If this time is unavailable in the data set, we will choose the closest time available to the 2-hour mark as the temporal measure to be included in this study. We will also measure the duration of pain in hours post-treatment.

Secondary outcomes

Secondary outcomes will include: (1) percentage of participants presenting ≥50% pain reduction 2 hours post-treatment; (2) percentage of participants who were headache-free 2 hours post-treatment23; and (3) characterisation of adverse events directly related to intervention as reported to assess safety measures.

Search strategy

We will search the following electronic database: MEDLINE (medical literature analysis and retrieval system on line), EMBASE (Excerpta Medica Database), the Cochrane Central Register of Controlled Trials, China National Knowledge Infrastructure, Chinese Science and Technology Periodical Database and the Wanfang Database. Furthermore, we will search clinical trial registries, academic dissertations, research conference proceedings and grey literature to reduce publication bias in our data. In addition, data from literature reviews and meta-analysis will be manually searched in case of omissions of data in traditionally styled reporting. Search dates will be from the inception of the online databases up to 31 August 2019, and the languages searched will be limited to either English or Chinese. The retrieval mode used will be a combination of free words and medical subject headings terms, including ‘migraine disorders, migraine, acupuncture therapy, acupuncture, electroacupuncture, moxibustion acupuncture, etc.’ until we feel we have exhausted all possibilities related to all the highly applicable search terms. The search strategy for PubMed is shown in box 1.

Box 1. Search strategy used for the PubMed database.

Search terms

1. randomised controlled trial [(pt])

2. controlled clinical trial [(pt])

3. randomised [(tiab])

4. placebo [(tiab])

5. clinical trials as topic [mesh: noexp]

6. randomly [(ab])

7. trial [(ti])

8. OR 1–7

9. humans [(mh])

10. 8 AND 9

11. Migraine Disorders [(Mesh])

12. migraine

13. migrain*

14. OR 11–13

15. 10 AND 14

16. acupuncture therapy [(Mesh])

17. acupuncture treatment

18. pharmacoacupuncture treatment

19. pharmacoacupuncture therapy

20. acupuncture [(Mesh])

21. electroacupuncture.

22. moxibustion acupuncture

23. warming needle moxibustion

24. fire needling

25. fire needle

26. fire acupuncture

27. OR 16–26

28. 15 AND 27

Study selection and data extraction

One reviewer will perform the searches according to designated search strategies and download relevant citations. NoteExpress V.3.0 will be used to remove duplicate literature through electronic/manual-based steps. Two reviewers will independently screen the study article titles and abstracts and then retrieve the studies most consistent with the eligibility criteria. Any disagreement between reviewers will be resolved through discussion with a third reviewer. All trials will be allocated to the following five groups: inclusion group, non-patient group, intervention group, outcome group and awaiting group. Two reviewers will use Microsoft Excel to encode and extract parameters from applicable studies including general information (author list, publication year, and journal), characteristics of included trials (diagnostic criteria, age range, intervention details) and outcome data (numbers of response events and non-response events, dropouts, time points, mean and SD). The risk of introduced bias will be analysed using the Cochrane risk of bias assessment tool.24 If there is any missing data and when necessary, corresponding authors will be contacted and asked to provide relevant details. Some studies will be excluded if we are unable to get access to the data and the reasons for exclusion will be reported in detail in these cases.

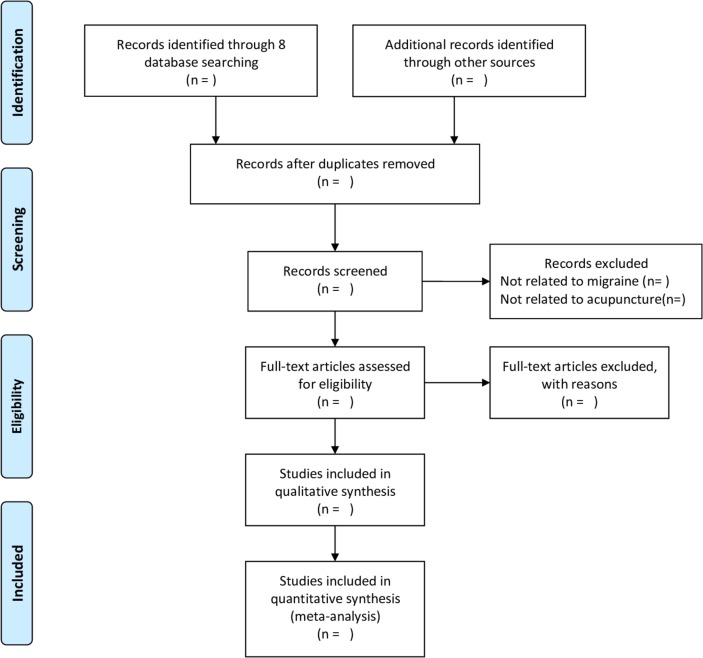

The entire stepwise process will be presented using a PRISMA flow chart (http://www.prismastatement.org) (figure 2).

Figure 2.

PRISMA flow diagram of the study selection process.

Quality assessment

Two reviewers will independently evaluate methodological quality of data using the Cochrane Collaboration Risk of Bias Tool.24 Six domains will be included: random sequence generation, allocation concealment, blinding of participants and personnel, blinding of outcome assessment, incomplete outcome data and selective outcome reporting. Each entry will be categorised into low, high or unclear risk of bias. Any disagreements between each of the two reviewers will be resolved through discussions with a third reviewer.

The level of the quality of evidence for main outcomes will be assessed with the Grading of Recommendations Assessment, Development, and Evaluation (GRADE) system approach performed independently by two reviewers and considering study limitations, inconsistency, indirectness, imprecision and publication bias.25 Quality assessments procedure will include the following steps: (1) presenting direct and indirect effect estimates; (2) rating the quality of direct and indirect estimates; (3) presenting the results of the network meta-analysis; and (4) rating the quality of the network meta-analysis effect estimations.

Network meta-analysis

We will use STATA V.14.0 and WinBUGS V.1.4.3 to perform the network meta-analysis. Data of the two groups will result from the use of different technologies and instead of identical acupuncture methods, we will merge data according to the Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions. The I2 statistic will be used to assess levels of the heterogeneity. Fixed effects models will be used if the I2 value is <50%, or else a random effects model will be used to perform the pairwise meta-analysis and to explore the main sources of heterogeneity. Continuous outcomes will be calculated as standardised mean differences (SMDs), and binary outcomes will be calculated as ORs. Both types of effect sizes will be presented with 95% CIs, and values of p<0.05 will be regarded as statistically significant.

For combining direct/indirect-based evidence, we will perform a Bayesian network meta-analysis using a random effects model. The node splitting method will be used to evaluate the inconsistency of direct and indirect estimates in each closed loop according to the resultant p-value.26 Values of p>0.05 indicate good consistency, and all inconsistencies will be reported (p<0.05). Bayesian inference will be analysed using the Markov chain Monte Carlo method. Iteration number will be set to 50,000, and the first 10 000 iterations for annealing will be set up to eliminate influences of the initial value. For indirect comparison, continuous outcomes will be calculated as SMDs, and binary outcomes will be calculated as ORs. Both types of effect sizes will be presented with 95% credible intervals. The estimation of the Gelman-Rubin statistic will be used to evaluate convergence of simulations. Furthermore, mean ranks and the area surface under the cumulative ranking curve will be presented as percentages, and corresponding graphs will be produced to sequence the probabilities of an optimal intervention. Evidence supporting the relationships of the included studies will be determined by analysis of a network plot, and resultant figures and network meta-analysis graphs will be presented.

Assessment of heterogeneity

Examination of clinical and methodological heterogeneity will focus on participants’ characteristics, interventions and outcomes of the included trials, and on comparisons of the goodness of fit of the fixed effects model and random effects model. Statistical heterogeneity will be assessed quantitatively using the I² statistic. Values of I2 <50% will indicate that heterogeneity is not salient for the cases that we explore. Meta-analysis will be performed after removal of studies where main or unacceptable sources of heterogeneity were derived. Furthermore, if the source of heterogeneity cannot be explored, a narrative review will be provided.

Assessment of transitivity and similarity

In order to produce a credible and valid result, an assessment of transitivity and similarity will be necessary. However, as it is difficult to identify the transitivity and similarity using statistical analysis, assessment will be based on clinical and methodological characteristics including participant characteristics (age and pain degree), study designs (blind method and risk of bias) and interventions (duration of treatment and needling techniques). All these research aspects and influential factors will be investigated and reported.

Sensitivity analysis and subgroup analysis

We will explore sources of heterogeneity by performing a network meta-regression using a random effects network meta-regression model. If the number of included studies is sufficient, we will conduct an analysis of the subgroups organised according to geographical region and race. In order to obtain a stable conclusion, we will conduct a sensitivity analysis to eliminate effects of trials with small sample size, eliminate studies not reporting a blind approach to procurement and analysis of data and eliminate studies rated as high risk of bias based on accounting of methodological quality. These steps will be crucial to ensure the accuracy and depth of inferences from results.

Publication bias

Publication bias will be evaluated using an Egger’s regression test which will help avoid observation bias and produce a funnel plot indicating a digitally based modelling result.

Additional analyses

With respect to the potential differences of acupoint selection and amount of stimulation between each acupuncturist, we expect that some correlation between the observed and inferred levels of the heterogeneity will most likely exist objectively. Because of its clinical importance, we will conduct a descriptive analysis of the acupoint selection, needling techniques, amount of electrical stimulation or any other factors that were detailed in the included studies that may generate heterogeneity in the treatment outcomes.

Patient and public involvement

No patients and members of the public will be directly involved. Only data already existent in the literature and the aforementioned sources will be used for this study.

Discussion

In China, acupuncture therapies to treat acute migraine attacks are diverse, and the appropriate selection of the method and approach specific to an individual’s course of treatment has not yet been standardised. Hence, clinicians always perform combinations of several acupuncture-based methods. The need to explore multiple methodologies to determine what works best for patients increases the burdens of time and financial investment on the patients, as well as increase inefficiency and wastage of medical resources. In recent years, several controlled clinical trials have been performed, but the quality of the research has been uneven and methodologies often limited without considering multiple factors together. Network meta-analysis can alternatively be used to integrate direct and indirect comparisons across a set of multiple variables,27 which can strengthen the inferences of efficacy and help to compare efficacies of different acupuncture treatments.28 In order to generate reliable experimentally based evidence on a larger scale as compared with limited types of single studies, we will perform a rigorous analysis with multiple inclusion criteria and quality scores for results assessed by a GRADE-based framework. Therefore, we expect that our results will provide a much needed and novel prioritisation regime for acupuncture treatment aimed at mitigating or alleviating acute migraine attacks. To the best of our knowledge, this study will be the first network meta-analysis of acupuncture methods for the treatment of acute migraine. We hope that our results will provide credible evidence to support the beneficial use of acupuncture and encourage wider acceptance of the positive measureable clinical applications of acupuncture as an alternative therapy for migraine. We will update this protocol required in the future and the date of amendments and description of changes will be presented as a supplement.

Ethics and dissemination

The results will be disseminated through peer-reviewed publication. Since no private and confidential patient data will be contained in the reporting, there are no ethical considerations associated with this protocol.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

The authors are grateful to Haoying Zhou for her helpful assistance.

Footnotes

Contributors: JZ and CW conceived the study and drafted the protocol. JuL, JiL and JY revised it. JZ, JuL and JiL developed the search strategies and will run it. JZ and JuL will select studies and extract data. JZ and JY will analyse the data. All authors have approved the final edition of the protocol.

Funding: The authors have not declared a specific grant for this research from any funding agency in the public, commercial or not-for-profit sectors.

Competing interests: None declared.

Patient consent for publication: Not required.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

References

- 1. Headache classification Committee of the International headache Society (IHS) the International classification of headache disorders, 3rd edition. Cephalalgia 2018;38:1–211. 10.1177/0333102417738202 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Feigin VL, Nichols E, Alam T, et al. . Global, regional, and national burden of neurological disorders, 1990-2016: a systematic analysis for the global burden of disease study 2016. Lancet Neurol 2019;18:459–80. 10.1016/S1474-4422(18)30499-X [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Puledda F, Messina R, Goadsby PJ. An update on migraine: current understanding and future directions. J Neurol 2017;264:2031–9. 10.1007/s00415-017-8434-y [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Marmura MJ, Silberstein SD, Schwedt TJ. The acute treatment of migraine in adults: the American headache Society evidence assessment of migraine pharmacotherapies. Headache 2015;55:3–20. 10.1111/head.12499 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Evers S, Áfra J, Frese A, et al. . EFNS guideline on the drug treatment of migraine--revised report of an EFNS task force. Eur J Neurol 2009;16:968–81. 10.1111/j.1468-1331.2009.02748.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Tfelt-Hansen PC. Evidence-Based guideline update: pharmacologic treatment for episodic migraine prevention in adults: report of the Quality Standards Subcommittee of the American Academy of Neurology and the American headache Society. Neurology 2013;80:869–70. 10.1212/01.wnl.0000427909.23467.39 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Hawkes N. Too frequent use of painkillers can cause rather than cure headaches. BMJ 2012;345:e6281 10.1136/bmj.e6281 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Gao Z, Giovanardi CM, Li H, et al. . Acupuncture for migraine: a protocol for a meta-analysis and meta-regression of randomised controlled trials. BMJ Open 2018;8:e022998 10.1136/bmjopen-2018-022998 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Liu Y, Yu S. Recent approaches and development of acupuncture on chronic daily headache. Curr Pain Headache Rep 2016;20:4 10.1007/s11916-015-0535-7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Wen Y, Wang D, Fan G. Acupoint selection for acute migraine treated with acupuncture. Chinese Acupuncture & Moxibustion 2018;38. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Millstine D, Chen CY, Bauer B. Complementary and integrative medicine in the management of headache. BMJ 2017;357 10.1136/bmj.j1805 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Burke A, Upchurch DM, Dye C, et al. . Acupuncture use in the United States: findings from the National health interview survey. J Altern Complement Med 2006;12:639–48. 10.1089/acm.2006.12.639 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Li Y, Liang F, Yang X, et al. . Acupuncture for treating acute attacks of migraine: a randomized controlled trial. Headache 2009;49:805–16. 10.1111/j.1526-4610.2009.01424.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Wang L-P, Zhang X-Z, Guo J, et al. . Efficacy of acupuncture for acute migraine attack: a multicenter single blinded, randomized controlled trial. Pain Med 2012;13:623–30. 10.1111/j.1526-4637.2012.01376.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Farahmand S, Shafazand S, Alinia E, et al. . Pain management using acupuncture method in migraine headache patients; a single blinded randomized clinical trial. Anesth Pain Med 2018;8:e81688 10.5812/aapm.81688 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Zhao L, Chen J, Li Y, et al. . The long-term effect of acupuncture for migraine prophylaxis: a randomized clinical trial. JAMA Intern Med 2017;177:508–15. 10.1001/jamainternmed.2016.9378 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Linde K, Allais G, Brinkhaus B, et al. . Acupuncture for the prevention of episodic migraine. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2016;25 10.1002/14651858.CD001218.pub3 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Linde K, Allais G, Brinkhaus B, et al. . Acupuncture formigraineprophylaxis. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2009;1. [Google Scholar]

- 19. Shamseer L, Moher D, Clarke M, et al. . Preferred reporting items for systematic review and meta-analysis protocols (PRISMA-P) 2015: elaboration and explanation. BMJ 2015;349:g7647 10.1136/bmj.g7647 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Hutton B, Salanti G, Caldwell DM, et al. . The PRISMA extension statement for reporting of systematic reviews incorporating network meta-analyses of health care interventions: checklist and explanations. Ann Intern Med 2015;162:777–84. 10.7326/M14-2385 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. MacPherson H, Altman DG, Hammerschlag R, et al. . Revised standards for reporting interventions in clinical trials of acupuncture (stricta): extending the CONSORT statement. PLoS Med 2010;7:e1000261 10.1371/journal.pmed.1000261 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Loder E, Burch R. Measuring pain intensity in headache trials: which scale to use? Cephalalgia 2012;32:179–82. 10.1177/0333102411434812 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Tfelt-Hansen P, Pascual J, Ramadan N, et al. . Guidelines for controlled trials of drugs in migraine: third edition. A guide for Investigators. Cephalalgia 2012;32:6–38. 38 10.1177/0333102411417901 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Higgins JPT, Green S, Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions Version 5.2.0. The Cochrane Collaboration, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- 25. Salanti G, Del Giovane C, Chaimani A, et al. . Evaluating the quality of evidence from a network meta-analysis. PLoS One 2014;9:e99682 10.1371/journal.pone.0099682 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Dias S, Welton NJ, Caldwell DM, et al. . Checking consistency in mixed treatment comparison meta-analysis. Stat Med 2010;29:932–44. 10.1002/sim.3767 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Caldwell DM, Ades AE, Higgins JPT. Simultaneous comparison of multiple treatments: combining direct and indirect evidence. BMJ 2005;331:897–900. 10.1136/bmj.331.7521.897 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Salanti G. Indirect and mixed-treatment comparison, network, or multiple-treatments meta-analysis: many names, many benefits, many concerns for the next generation evidence synthesis tool. Res Synth Methods 2012;3:80–97. 10.1002/jrsm.1037 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

bmjopen-2019-031043supp001.pdf (93.2KB, pdf)