Abstract

Background

Most maternal and child deaths are preventable or treatable with proven, cost-effective interventions for infectious diseases and maternal and neonatal complications. In 2015 sub-Saharan Africa accounted for up to 66% of global maternal deaths and half of the under-five deaths. Access to essential medicines and commodities and trained healthcare workers to provide life-saving maternal, newborn and post-natal care are central to further reductions in maternal and child mortality.

Methods

Available data for 24 priority medicines for women and children were extracted from WHO service availability and readiness assessments conducted between 2012 and 2015 for eight countries in sub-Saharan Africa. The mean availability of medicines in facilities stating they provide services for women or children and differences by facility type, ownership and location are reported.

Results

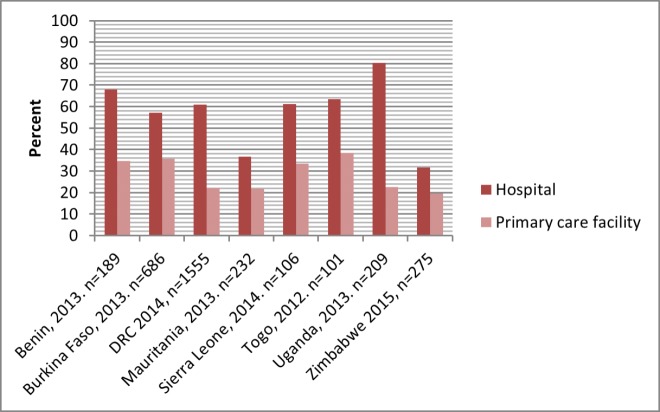

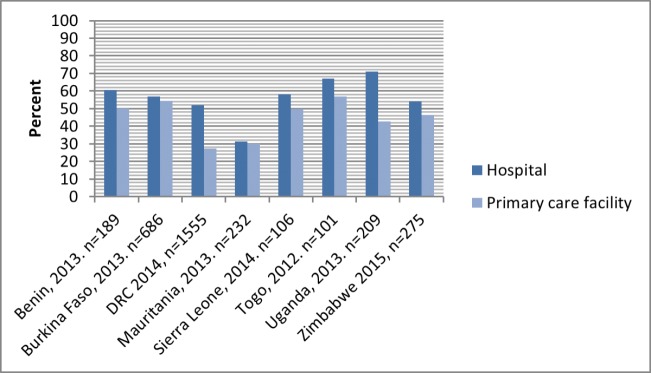

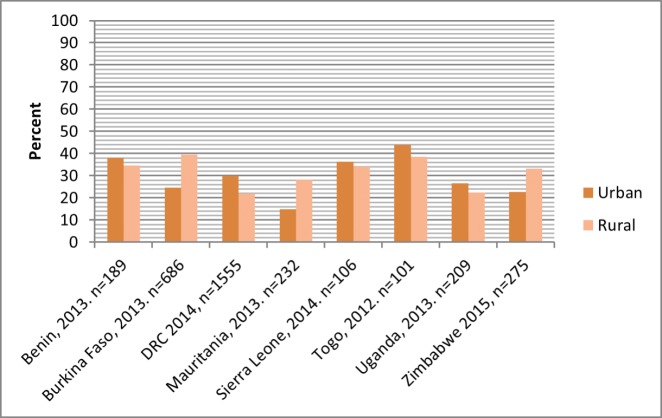

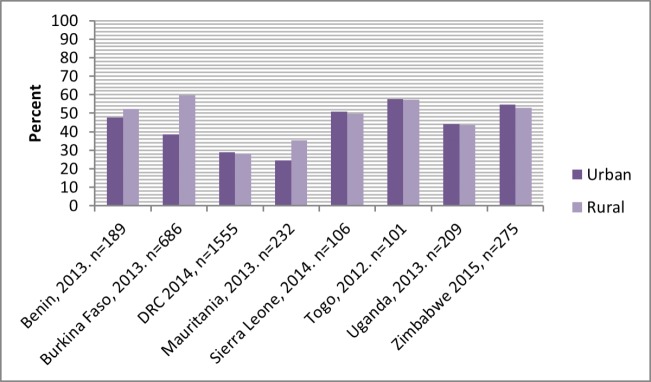

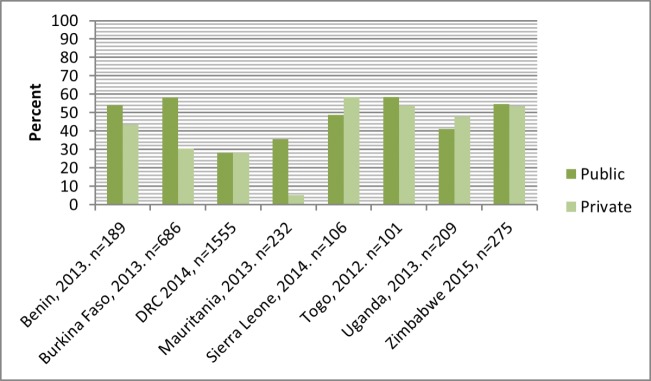

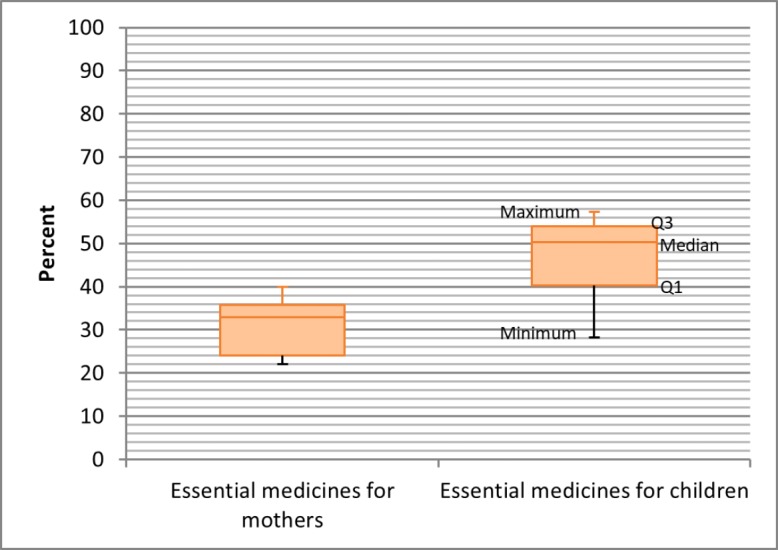

The mean availability of 12 priority essential medicines for women ranged from 22% to 40% (median 33%; IQR 12%) and 12 priority medicines for children ranged from 28% to 57% (median 50%; IQR 14%). Few facilities (<1%) had all nominated medicines available. There was higher availability of priority medicines for women in hospitals than in primary care facilities: range 32%–80% (median 61%) versus 20%–39% (median 23%) and for children’s medicines 31%–71% (median 58%) versus 27%–57% (median 48%). Availability was higher in public than private facilities: for women’s medicines, range 21%–41% (median 34%) versus 4%–36% (median 27%) and for children’s medicines 28%–58% (median 51%) versus 5%–58% (median 46%). Patterns were mixed for rural and urban location for the priority medicines for women, but similar for children’s medicines.

Conclusions

The survey results show unacceptably low availability of priority medicines for women and children in the eight countries. Governments should ensure the availability of medicines for mothers and children if they are to achieve the health sustainable development goals.

Keywords: essential medicines, priority medicines, availability, women, children, sub-saharan africa

Summary box.

What is already known?

There are limited data on the availability of essential medicines for the prevention and treatment of infectious diseases and maternal and neonatal complications in sub-Saharan Africa.

What are the new findings?

In eight sub-Saharan countries (Benin, Burkina Faso, Democratic Republic of the Congo, Uganda, Mauritania, Sierra Leone, Togo and Zimbabwe), mean availability of 12 essential medicines for women ranged from 22% to 40% and 12 priority medicines for children ranged from 28% to 57%.

Generally, availability was higher in hospitals than in primary care facilities; patterns were less consistent for urban versus rural locations, and public versus private facilities.

What do the new findings imply?

Further investigation is needed to determine whether low availability reflects lack of demand, that the medicines are not included in local treatment guidelines or protocols, or there are failings in procurement and distribution for these products.

Efforts are needed to strengthen medicine regulatory systems to ensure the quality of products in circulation, improve medicine supply chain management, ensure adequate financing for purchase of medicines, and support the education and training of healthcare workers in the use of these essential commodities.

Background

Sexual and reproductive health along with newborn and child survival is important to the global development agenda. The Millennium Development Goals 4 and 5 proposed reductions in under-five deaths by two-thirds and in maternal mortality by three-quarters between 1990 and 2015. These commitments resulted in substantial improvements in maternal and child health globally, with the number of under-five deaths reducing by half from 12.7 million in 1990 to 5.9 million in 2015, and maternal deaths by 42% from 523 000 in 1990 to 3 03 000 in 2015.1 Progress with neonatal deaths was somewhat slower compared with under-five mortality, with neonatal mortality rate per 1000 reducing from 36 in 1990 to 19 in 2015.2

Most of the maternal and child deaths occur in developing countries. In 2015 for instance, half of the under-five deaths occurred in sub-Saharan Africa and a third in Southern Asia.3 During the same year, sub-Saharan Africa accounted for up to 66% of global maternal deaths (201 000 of 303 000 deaths) followed by Southern Asia (22%).1 Postpartum haemorrhage was the leading cause of maternal death in low-income countries, with death rates around 150 per 100 000 deliveries in sub-Saharan Africa compared with 0.4 per 100 000 in the UK.4 The sustainable development goals (SDGs), adopted in September 2015, continue this agenda with aims to reduce the global maternal mortality ratio to less than 70 per 100 000 live births (health goal 3.1) and to end preventable deaths of newborns and children under 5 years of age with targets at least as low as 12 per 1000 live births and under-five mortality at least as low as 25 per 1000 live births (goal 3.2) by 2030.5

Most maternal and child deaths are preventable or treatable with proven, cost-effective interventions for infectious diseases and maternal and neonatal complications. Access to essential medicines and commodities and to a health workforce trained to provide life-saving maternal and newborn care during pregnancy, birth and postnatal period along with targeted programme to address specific maternal and child health needs form the nexus for further reduction in maternal and child mortality.

In 2011, the WHO together with the United Nations Children’s Fund and the United Nations Population Fund identified a list of 30 medicines, based on the burden of disease and evidence of benefit, to address the essential medicine needs of mothers and children.6 The list was updated in 2012 and renamed the ‘priority life-saving medicines for women and children’ (table 1).7 The medicines for women include medicines for preventing and treating postpartum haemorrhage, severe pre-eclampsia and eclampsia, maternal sepsis and provision of safe abortion and management of complications of abortion or miscarriage. Priority medicines for children include those for treating pneumonia, diarrhoea, malaria, neonatal sepsis, HIV/AIDS and vitamin A deficiency. The expectation is that facilities providing maternal and child health services in each country have these medicines available at all times.

Table 1.

List of priority life-saving medicines for women and children7

| Women | Children |

| Postpartum haemorrhage | Pneumonia |

| Oxytocin | Amoxicillin |

| Misoprostol | Ampicillin |

| Sodium chloride | Ceftriaxone |

| Sodium lactate compound | Gentamicin |

| Severe pre-eclampsia and eclampsia | Oxygen |

| Magnesium sulfate | Diarrhoea |

| Calcium gluconate injection | Oral rehydration salts |

| Hydralazine | Zinc |

| Methyldopa | Malaria |

| Maternal sepsis | Artemisinin-based combination therapy |

| Ampicillin | Artesunate (rectal, injection) |

| Gentamicin | Neonatal sepsis |

| Metronidazole | Ampicillin |

| Provision of safe abortion services and/or the management of incomplete abortion and miscarriage | Ceftriaxone |

| Gentamicin | |

| Procaine benzylpenicillin | |

| Misoprostol | Vitamin A deficiency |

| Mifepristone+misoprostol | Vitamin A |

| Sexually transmitted infections | Palliative care and pain |

| Azithromycin | Morphine |

| Cefixime | Paracetamol |

| Benzathine benzylpenicillin | Vaccines |

| Management of preterm labour | Vaccines (national schedule) |

| Nifedipine | HIV |

| Dexamethasone | Standard regimen for first-line |

| Betamethasone | antiretroviral treatment |

| Prevention of tetanus in mother and newborn | |

| Tetanus vaccine | |

| Contraception | |

| Oral contraceptives |

Source: Priority life-saving medicines for women and children 2012 http://apps.who.int/iris/bitstream/10665/75154/1/WHO_EMP_MAR_2012.1_eng.pdf?ua=1.

This study assessed the availability of 24 priority life-saving medicines for women and children in eight sub-Saharan African countries that have publicly available service availability and readiness assessment (SARA) data with WHO Benin, Burkina Faso, Democratic Republic of the Congo, Mauritania, Sierra Leone, Togo, Uganda and Zimbabwe using the most recent SARA data for each country. All the eight countries share a high burden of maternal, neonatal and under-five deaths, with maternal mortality ratio per 100 000 live births in 2015 ranging from 343 in Uganda to 1360 in Sierra Leone, and neonatal and under-five mortality rates per 1000 live births ranging from 19 in Uganda to 36 in Mauritania and 55 in Uganda to 120 in Sierra Leone, respectively.1 2

Methods

WHO, with funding support from partners such as Global Fund and Global Alliance for Vaccine Initiative, provides technical support to countries to conduct SARA surveys every 1–2 years to assess if health facilities meet the basic standards to provide essential service. SARA surveys are conducted at the request of, and in conjunction with, Ministries of Health to support health service planning. Service availability refers to the physical presence of delivery of services. Service readiness meanwhile refers to the ability of health facilities to provide a service—measured through the availability of items such as medicines, trained staff, guidelines, equipment and laboratory services.8

The number of facilities surveyed during SARA is often the maximum feasible, depending on available funds. The facilities are sampled nationally using multi-stage stratified random sampling. Stratification is by facility level and public–private ownership. Where sample size permits, further stratification is done by urban–rural location. Data are collected using WHO’s standard SARA core questionnaire, with adaptations to country context for facility classifications, subnational administrative units and staff categories.9 The SARA core questionnaire is a validated tool that focuses on key health services and the ability or readiness of facilities to offer the services. The questionnaire does not attempt to measure the quality of services or resources, but it can be used in conjunction with additional modules such as management assessment or quality of care. Availability is assessed by direct observation of the in-date medicine in the facility, regardless of quantity present.

Data are collected through key-informant interviews by trained local data collectors working to established methods under the strict supervision of survey coordinators. Data are collected using both paper questionnaire and mobile electronic devices using census and survey processing software, with paper questionnaires serving as a backup. Quality assurance that includes repeat of surveys in 10% of participating facilities is often provided by external agencies (eg, John Snow) or a locally sourced academic institution.

The assessment of availability of priority life-saving medicines in this study is based on 24 of the 30 medicines recommended by WHO: 12 for women and 12 for children (table 2). Oxytocin is the preferred uterotonic for the prevention and management of postpartum haemorrhage.10 Misoprostol tablets are recommended when oxytocin is not available or cannot be used safely. Magnesium sulfate is recommended for treating severe pre-eclampsia and eclampsia that are associated, annually, with an estimated 50 000 maternal deaths worldwide.11 Calcium gluconate is used for treatment of magnesium sulfate toxicity. Dexamethasone or betamethasone injections can improve foetal lung maturity in the case of preterm birth. WHO guidelines recommend oral rehydration salts (ORS) and zinc supplementation for the treatment of childhood diarrhoea.12 Artemisinin-based combination treatments are first-line oral treatments for malaria with artesunate rectal formulations recommended for the pre-referral treatment of children with severe malaria.13 Oral amoxicillin is first-line treatment for community-acquired pneumonia in children; ampicillin, gentamicin and ceftriaxone are used to treat severe pneumonia in children as well as neonatal and maternal sepsis. Vitamin A is used for treatment and prevention of Vitamin A deficiency which is a recognised risk factor for severe measles, a common cause of death in low/middle-income countries. Paracetamol and morphine meanwhile are the recommended medicines for relieving pain.

Table 2.

List of essential medicines included in the study

| Women | Children | |

| 1 | Oxytocin injectable | Amoxicillin syrup/suspension |

| 2 | Sodium chloride injectable solution | Ampicillin powder for injection |

| 3 | Calcium gluconate injectable | Ceftriaxone powder for injection |

| 4 | Magnesium sulfate injectable | Gentamicin injectable |

| 5 | Ampicillin powder for injection | Procaine benzylpenicillin injection |

| 6 | Gentamicin injectable | Oral rehydration solution sachets |

| 7 | Metronidazole injectable | Zinc tablets |

| 8 | Misoprostol capsules or tablets | ACT |

| 9 | Azithromycin capsules, tablet or oral liquid | Artesunate rectal or injectable forms |

| 10 | Cefixime capsule or tablet | Vitamin A capsules |

| 11 | Benzathine benzylpenicillin powder for injection | Morphine granule, injectable, capsules or tablets |

| 12 | Betamethasone or dexamethasone injectable | Paracetamol syrup/suspension |

ACT, artemisinin-based combination therapy.

Data analysis was carried in STATA V.11.0 using methods that are appropriate for the survey design in each country. This involves application of sampling weights to reflect the probability of selection of facilities at each stage of the sampling design and using STATA commands for survey data for all analyses. Details of the analysis are as follows: Each variable was assigned value 1 if the medicine was available and 0 if unavailable. Sampling weights were then applied. The percentage of facilities that had the medicine was calculated (sum of facilities with item/total number of facilities *100) with 95% CI overall and then by facility level, public–private ownership, and urban–rural location. The mean of the medicines was then calculated together with the 95% CI overall and then by facility level, public–private ownership and urban–rural location—ensuring that all medicines carry the same weight as each facility is expected to have them.

Analysis was done only among facilities that indicated that they provided maternal and child health services, as some facilities, by policy design, are not meant to provide certain services.

Patient and public involvement

Patients and the public are not involved in SARA surveys. With WHO technical support, each of the countries has produced comprehensive SARA reports and disseminated them, through dissemination workshops, to all key stakeholders, including health partners. Results are used to inform health systems and policy development and implementation. This article adds to this effort. The results will particularly be used to generate policy briefs and support knowledge brokering to improve availability of essential medicines for mothers and children in the African region.

Results

Data for this report are for the most recent SARA survey in eight countries in sub-Saharan Africa, namely: Benin (2013, n=189 facilities), Burkina Faso (2013, n=686), Democratic Republic of the Congo (2014, n=1555), Uganda (2013, n=209), Mauritania (2013, n=232), Sierra Leone (2014, n=106), Togo (2012, n=101) and Zimbabwe (2015, n=275).

The percentage of facilities that reported the availability of maternal health services ranged from 53% in Uganda to 91% in Sierra Leone and Togo. For child health services, it ranged from 72% in Mauritania to 99% in Togo and Zimbabwe.

The availability of essential medicines for women and children

Of the 12 essential medicines for women that were enquired about, only 1% of the facilities in Uganda, Mauritania and Sierra Leone, and none in the rest of the countries had all of them (table 3). For child health services, none of the facilities had all the 12 essential medicines (table 4).

Table 3.

Percentage of facilities offering maternal health services and had the indicated medicines, by country

| Benin 2013 n=189 |

Burkina Faso 2013 n=686 |

DRC 2014 n=1555 |

Mauritania 2013 n=232 |

Sierra Leone 2014 n=106 | Togo 2012 n=101 |

Uganda 2013 n=209 |

Zimbabwe 2015 n=275 | |

| % of facilities offering maternal health services | 70 | 87 | 77 | 55 | 91 | 91 | 53 | 90 |

| Among facilities that indicated offering maternal health services, the percentage with the medicines | ||||||||

| Oxytocin | 63 | 80 | 40 | 37 | 49 | 80 | 46 | 85 |

| Sodium chloride | 51 | 38 | 32 | 28 | 54 | 50 | 36 | 70 |

| Calcium gluconate injection | 54 | 9 | 17 | 7 | 35 | 63 | 10 | 8 |

| Magnesium sulfate injection | 26 | 18 | 8 | 11 | 74 | 18 | 30 | 86 |

| Ampicillin injection | 64 | 83 | 47 | 44 | 23 | 70 | 30 | 2 |

| Gentamicin injection | 58 | 68 | 11 | 36 | 26 | 62 | 40 | 41 |

| Metronidazole injection | 42 | 41 | 24 | 27 | 58 | 19 | 19 | 2 |

| Misoprostol | 6 | 1 | 2 | 2 | 7 | 2 | 11 | 8 |

| Azithromycin | 10 | 1 | 11 | 6 | 6 | 7 | 11 | 1 |

| Cefixime | 1 | 1 | 16 | 3 | 3 | 2 | 7 | 1 |

| Benzathine benzylpenicillin injection | 14 | 78 | 29 | 30 | 31 | 56 | 30 | 66 |

| Betamethasone or dexamethasone injection | 43 | 11 | 46 | 33 | 51 | 50 | 20 | 4 |

| Offering services and with all 12 essential medicines | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 0 |

| Mean availability of the 12 medicines (%) | 36 | 36 | 24 | 22 | 35 | 40 | 24 | 31 |

Table 4.

Percentage of facilities offering child health services and had the indicated medicines, by country

| Benin 2013 n=189 |

Burkina Faso 2013 n=686 |

DRC 2014 n=1555 |

Mauritania 2013 n=232 |

Sierra Leone 2014 n=106 | Togo 2012 n=101 |

Uganda 2013 n=209 |

Zimbabwe 2015 n=275 |

|

| % of facilities with child health services | 93 | 95 | 88 | 72 | 97 | 99 | 93 | 99 |

| Among facilities offering child health services, percentage that had the essential medicines | ||||||||

| Amoxicillin | 56 | 87 | 47 | 56 | 89 | 79 | 28 | 86 |

| Ampicillin injectable | 82 | 88 | 49 | 54 | 25 | 75 | 36 | 2 |

| Ceftriaxone | 38 | 76 | 15 | 6 | 7 | 66 | 33 | 31 |

| Gentamicin | 71 | 70 | 11 | 48 | 29 | 70 | 51 | 0 |

| Benzyl penicillin | 9 | 9 | 28 | 20 | 50 | 16 | 36 | 80 |

| ORS | 69 | 81 | 54 | 49 | 88 | 82 | 73 | 93 |

| Zinc | 66 | 31 | 21 | 13 | 81 | 50 | 65 | 95 |

| ACT | 84 | 86 | 59 | 19 | 67 | 84 | 82 | 96 |

| Artesunate | 9 | 3 | 4 | 4 | 22 | 19 | 8 | 2 |

| Vitamin A | 61 | 38 | 25 | 39 | 68 | 76 | 75 | 95 |

| Morphine | 2 | 2 | 1 | 3 | 5 | 4 | 2 | 2 |

| Paracetamol | 57 | 82 | 25 | 51 | 70 | 66 | 34 | 64 |

| Offering services and with all 12 essential medicines | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Mean availability of the 12 medicines (%) | 50 | 54 | 28 | 30 | 50 | 57 | 44 | 54 |

ACT, artemisinin-based combination therapy; ORS, oral rehydration salts.

The mean availability was particularly low for the maternal medicines, ranging from 22% to 40% (median 32%, IQR 11%), meaning that facilities that reported offering maternal services had only 3–5 of the 12 medicines (figure 1). Maternal medicines such as misoprostol, cefixime and azithromycin were available in less than 10% of the facilities (table 3). Availability of the essential medicines for children was slightly better with the mean availability ranging from 28% to 57% (median 50%). The availability of artesunate and morphine was particularly low (table 4).

Figure 1.

Mean availability of the 12 essential medicines for women and children.

In almost all the countries, mean availability of the essential medicines for women and children was substantially higher in hospitals than in primary care facilities (figures 2 and 3). The differences in availability were more pronounced in the case of the medicines for women. However, the pattern by facility location was less clear: in Benin, Uganda, Sierra Leone and Democratic Republic of the Congo, the essential medicines for women were more available in urban than in rural facilities; in the other countries, availability was higher in rural than in urban facilities (figure 4). The availability of children’s medicines was generally similar between urban and rural facilities except in Burkina Faso and Mauritania where it was substantially higher in rural than in urban facilities (figure 5). The essential medicines for both women and children were more available in public than in private facilities in Benin, Burkina Faso, Mauritania, Togo and Zimbabwe, with marked differences in Benin, Burkina Faso and Mauritania (figures 6 and 7). For children’s medicines in Benin for instance, ACT was available in 92% of public facilities compared with 69% of private facilities, and zinc was available in 76% of public facilities compared with 47% of private facilities. Similarly in Burkina Faso, ACT and zinc were available in 92% and 35% of public facilities compared with 48% and 1% of private facilities, respectively.

Figure 2.

Mean availability of 12 essential medicines for women, by facility type.

Figure 3.

Mean availability of 12 essential medicines for children, by facility type.

Figure 4.

Mean availability of 12 essential medicines for women, by facility location.

Figure 5.

Mean availability of 12 essential medicines for children, by facility location.

Figure 6.

Mean availability of 12 essential medicines for women, by facility ownership.

Figure 7.

Mean availability of 12 essential medicines for children, by facility ownership.

Discussion

These results confirm the poor availability of priority medicines for women and children in sub-Saharan Africa. The mean availability of 12 essential medicines for women was less than 50% in all eight countries surveyed (range 22%–40%). There was slightly better availability of the 12 priority medicines for children (range 28%–57%). Few facilities had all the nominated medicines available at the time of the survey. These results are notwithstanding the ongoing international efforts including guidelines targeting treatment of diarrhoea and pneumonia in children and implementation efforts by the UN Commission on Life-Saving Commodities for Women and Children, ‘the Every Women Every Child program’, ‘Muskoka Initiative Partnership Program’ and other NGO-led initiatives.10 14–18

While studies have assessed the inclusion of these priority medicines for women and children in national essential medicines lists,19 20 there are few data on the extent to which they are available in health facilities. An augmented key informant study in 37 countries (18 of these in Africa) suggested that oxytocin and magnesium sulfate were regularly available (available ‘more than half of the time’) in 89% and 76% of surveyed countries, respectively, with regular availability of misoprostol in 27% of countries.21 Spector et al reported around 70% availability of oxytocin and magnesium sulfate injection in 18 low-income countries, 16 of which were in Africa; however, these data were based on self-reports using an internet-based survey and very small numbers of facilities in each participating country.22 Our results accord with reasonable availability of oxytocin (37%–85% of facilities across countries); however, results for magnesium sulfate were more variable (8%–86% of facilities depending on the country) and misoprostol was not widely available (range 1%–11% of facilities).

The availability of oxytocin tells only part of the story. Its effectiveness is dependent on refrigeration of the product and the availability of trained staff to administer it. In addition, there are reported problems with the quality of oxytocin in circulation that may relate to inadequate storage and transportation and/or low manufacturing quality.23 24 Low availability compounded by poor quality threatens the quality of care that can be offered to women.25 26 Trials with the room temperature stable carbetocin offer promise of a more reliably effective treatment for the prevention of postpartum haemorrhage and may contribute to improvements in maternal survival.27 28

Medicines access is restricted to particular levels of care in some settings. The low availability of azithromycin (range 1%–11% of facilities) and cefixime (1%–16%) in part reflects their restriction to use in specialist or referral facilities in most of the eight countries. In the era of antimicrobial resistance, these restrictions may assist in reducing inappropriate use of these agents and preserve their usefulness for clinical care.

Facility ownership may also influence care. For example, data from 29 countries in sub-Saharan Africa indicate private providers are less likely to prescribe oral rehydration for children with diarrhoea and more likely to prescribe pills or syrups, antibiotics, herbal remedies and other medicines that do not treat dehydration.29 Our data are consistent with these observations, with lower availability of ORS and zinc sulfate in private compared with public facilities; for ORS range 6%–92% (median 55%) versus 56%–94% (median 84%), and for zinc, 1%–93% (median 36%) versus 16%–97% (median 66%), respectively. Medicine choices are also influenced by caregiver preferences for treatment types, perceptions about causes of diarrhoea, cost of treatments and distance to health facilities.30 31 Increasing use of ORS and zinc requires strategies for public and private sectors, along with improving knowledge of caregivers on the preparation and use of ORS, and facilitating access through community outlets.32

The low levels of availability of artesunate injection or rectal formulations found were less surprising. WHO guidelines recommended the use of rectal artesunate for pre-referral treatment of children with severe malaria, in advance of the availability of a WHO-prequalified product or marketing authorisation of a formulation by a stringent regulatory authority. The intention was to provide advocacy for product development and the launch of a quality-assured rectal artesunate formulation followed in 2017.33 Even in the absence of the rectal (or injection) formulation it cannot be inferred there were no medicines available for treating severe malaria; the national essential medicine lists of all eight countries included both artemether injection and quinine injections. The availability of these alternative treatments was not assessed in this study.

Fewer than 5% of healthcare facilities in each country surveyed had morphine available in injection, tablet or granule formulations. This is consistent with other studies showing very low opioid consumption in Africa, in part due to severely restricted formularies of opioids, poor availability of opioids even when included in national essential medicines lists and excessive regulation that limits patient access.34

The strengths of this study are the large numbers and representative sample of facilities surveyed in each country. The stratification by facility level, managing authority and location allows for sector level monitoring of progress towards health objectives and identification of problem areas that need to be addressed. It is unclear from these cross-sectional data whether low availability reflects lack of demand, that the medicines are not included in local treatment guidelines or protocols, or there are failings in procurement and distribution for these products.

Differences in estimates of medicines availability can relate to study methods, facility selection and definitions of products surveyed.35 However reliable quantification is critical in order to assess problems, determine causes, institute remedies to improve the availability of critical medicines and monitor changes over time. At a national level it is important to understand the capacities of different actors in the healthcare system to provide services. Where there are not enough public facilities or trust in these facilities is low, patients may choose or be forced to attend private facilities. If the availability of essential medicines in the private sector is low, it is important to find out what treatments are being used and whether evidence-based treatment guidelines and algorithms are being followed. Studies need to consider medicine affordability and the potential impact of out-of-pocket costs on use of these medicines by the women and children who need them.

A full discussion of the national medicine supply systems in each country is beyond the scope of this study. While there are some national differences, all countries surveyed are low-income countries with very limited budgets for medicines procurement for the public sector. All have a mix of national agencies and private wholesalers procuring and distributing essential medicines for public and private healthcare sectors, often supplemented with donor programme providing medicines and training of healthcare workers to support local initiatives to improve healthcare services.

This study illustrates that the availability of key essential medicines for women and children under 5 years of age in sub-Saharan Africa is unacceptably low. These medicines should be available in functioning health systems at all times.36

bmjgh-2018-001306supp001.pdf (142.1KB, pdf)

Footnotes

Handling editor: Valery Ridde

Contributors: BD and JR conceived the idea. BD assembled the data, did analysis of the data and wrote the study methods and results that were reviewed by JR, KPO’N, DYTD and MM. JR wrote the background document that was reviewed by BD, KPO’N, DYTD and MM. BD and JR wrote the discussion and conclusion sections that were reviewed by KPO’N, DYTD and MM.

Funding: The authors have not declared a specific grant for this research from any funding agency in the public, commercial or not-for-profit sectors.

Competing interests: None declared.

Patient consent for publication: Not required.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

Data availability statement: The data that support the findings of this study areavailable on request from the corresponding author BD.

References

- 1.World Health Organization Trends in maternal mortality: 1990 to 2015. estimates by who, UNICEF, UNFPA, the world bank and the United nations population division. Geneva: World Health Organization, 2015. (Accessed 25 July 2017). [Google Scholar]

- 2.United Nations Children’s Fund Levels and trends in child mortality: report 2015. The un Inter-agency group for child mortality estimates. Available: https://www.unicef.org/publications/files/Child_Mortality_Report_2015_Web_9_Sept_15.pdf [Accessed 25 July 2017].

- 3.United Nations Inter-agency Group for Child Mortality Estimation (UN-IGME) Levels and trends in child mortality, 2015. Available: http://www.who.int/maternal_child_adolescent/documents/levels_trends_child_mortality_2015/en/ [Accessed 18 Aug 2017].

- 4.Say L, Chou D, Gemmill A, et al. . Global causes of maternal death: a who systematic analysis. The Lancet Global Health 2014;2:e323–33. 10.1016/S2214-109X(14)70227-X [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.World Health Organization World health statistics 2017: monitoring health for the SDGs, sustainable development goals. Available: http://apps.who.int/iris/bitstream/10665/255336/1/9789241565486-eng.pdf [Accessed 5 Feb 2018].

- 6.World Health Organization Priority medicines for mothers and children 2011. Geneva: World Health Organization, 2011. (Accessed 24 Aug 2017). [Google Scholar]

- 7.World Health Organization Priority life-saving medicines for women and children 2012. Geneva: World Health Organization, 2012. (Accessed 24 Aug 2017). [Google Scholar]

- 8.World Health Organization Service availability and readiness assessment (SARA): an annual monitoring system for service delivery. reference manual version 2.2 (revised July 2015). Available: http://www.who.int/healthinfo/systems/SARA_Reference_Manual_Chapter2.pdf?ua=1 [Accessed 5 Feb 2018].

- 9.World Health Organization Service availability and readiness assessment (SARA): indicators and questionnaire. Available: http://www.who.int/healthinfo/systems/sara_indicators_questionnaire/en/ [Accessed 8 Feb 2018].

- 10.World Health Organization Who recommendations for the prevention and treatment of postpartum haemorrhage. Geneva: World Health Organization, 2012. (Accessed 24 Aug 2017). [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.World Health Organization Who recommendations for the prevention and treatment of pre-eclampsia and eclampsia. Geneva: World Health Organization, 2011. (Accessed on 17 June 2019). [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.World Health Organization/The United Nations Children’s Fund (UNICEF) 2013 Ending preventable child deaths from pneumonia and diarrhoea by 2025: the integrated global action plan for pneumonia and diarrhoea (GAPPD. Geneva: World Health Organization, 2013. (Accessed 24 Aug 2017). [Google Scholar]

- 13.World Health Organization Global Malaria Program Rectal artesunate for pre-referral treatment of severe malaria, 2017. Available: http://apps.who.int/iris/bitstream/10665/259356/1/WHO-HTM-GMP-2017.19-eng.pdf [Accessed 5 Feb 2018].

- 14.World Health Organization Strategies toward ending preventable maternal mortality (EPMM. Geneva: World Health Organization, 2015. (Accessed 24 Aug 2017). [Google Scholar]

- 15.World Health Organization Every newborn: an action plan to end preventable deaths. Geneva: World Health Organization, 2015. (Accessed 24 Aug 2017). [Google Scholar]

- 16.UNICEF Committing to child survival: a promise renewed. Available: http://www.apromiserenewed.org/ [Accessed 24 Feb 2017].

- 17.United Nations Every woman every child. Available: http://www.everywomaneverychild.org/about/what-is-every-woman-every-child [Accessed 24 August 2017].

- 18.Government of Canada The Muskoka initiative (2010-2015). Available: http://mnch.international.gc.ca/en/topics/leadership-muskoka_background.html [Accessed 24 Aug 2017].

- 19.Hill S, Yang A, Bero L. Priority medicines for maternal and child health: a global survey of national essential medicines Lists. PLoS One 2012;7:e38055 10.1371/journal.pone.0038055 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Lalani A, Firoz T, Magee LA, et al. . For the community level interventions for pre-eclampsia (clip) Working Group. pharmacotherapy for preeclampsia in low and middle income countries: an analysis of essential medicines Lists. J Obstet Gynaecol Can 2013;35:215–23. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Smith JM, Currie S, Cannon T, et al. . Are national policies and programs for prevention and management of postpartum hemorrhage and preeclampsia adequate? a key informant survey in 37 countries. Glob Health Sci Pract 2014;2:275–84. 10.9745/GHSP-D-14-00034 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Spector JM, Reisman J, Lipsitz S, et al. . Access to essential technologies for safe childbirth: a survey of health workers in Africa and Asia. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth 2013;13:43 10.1186/1471-2393-13-43 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Torloni MR, Gomes Freitas C, Kartoglu UH, et al. . Quality of oxytocin available in low- and middle-income countries: a systematic review of the literature. BJOG: Int J Obstet Gy 2016;123:2076–86. 10.1111/1471-0528.13998 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Anyakora C, Oni Y, Ezedinachi U, et al. . Quality medicines in maternal health: results of oxytocin, misoprostol, magnesium sulfate and calcium gluconate quality audits. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth 2018;18:44https://doi.org/ 10.1186/s12884-018-1671-y [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.World Health Organization Who global surveillance and monitoring system for substandard and falsified medical products. Geneva: World Health Organization, 2017Licence: CC BY-NC-SA 3.0 IGO (Accessed 8 Feb 2018). [Google Scholar]

- 26.World Health Organization Falsified cefixime products circulating in the Democratic Republic of the Congo. Medical product alert N° 1/2018, 2018. Available: http://www.who.int/medicines/publications/drugalerts/en/ [Accessed 8 Feb 2018].

- 27.Maged AM, Hassan AMA, Shehata NAA. Carbetocin versus oxytocin in the management of atonic post partum haemorrhage (PPH) after vaginal delivery: a randomised controlled trial. Arch Gynecol Obstet 2016;293:993–9. 10.1007/s00404-015-3911-y [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Widmer M, Piaggio G, Abdel-Aleem H, et al. . Room temperature stable carbetocin for the prevention of postpartum haemorrhage during the third stage of labour in women delivering vaginally: study protocol for a randomized controlled trial. Trials 2016;17:143https://doi.org/ 10.1186/s13063-016-1271-y [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Sood N, Wagner Z. Private sector provision of oral rehydration therapy for child diarrhea in sub-Saharan Africa. Am J Trop Med Hyg 2014;90:939–44. 10.4269/ajtmh.13-0279 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Bedford KJA, Sharkey AB. Local barriers and solutions to improve care-seeking for childhood pneumonia, diarrhoea and malaria in Kenya, Nigeria and niger: a qualitative study. PLoS One 2014;9:e100038 10.1371/journal.pone.0100038 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Olson CK, Bartlett AV, Breiman RF, et al. . Community case management of childhood diarrhea in a setting with declining use of oral rehydration therapy: findings from cross-sectional studies among primary household caregivers, Kenya, 2007. Am J Trop Med Hyg 2011;85:1134–40. 10.4269/ajtmh.2011.11-0178 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Jammalamadugu SB, Mosime B, Masupe T, et al. . Assessment of the household availability of oral rehydration salt in rural Botswana. Pan Afr Med J 2013;15 10.11604/pamj.2013.15.130.2793 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.World Health organization special programme for research and training in tropical diseases (TDR). rectal artesunate suppositories launched for severe malaria in young children. News 2017;27http://www.who.int/tdr/news/2017/malaria-rectal-artesunate-suppositories/en/ [Google Scholar]

- 34.Cleary J, Powell RA, Munene G, et al. . Formulary availability and regulatory barriers to accessibility of opioids for cancer pain in Africa: a report from the global opioid policy initiative (GOPI). Annals of Oncology 2013;24(suppl 11):xi14–23. 10.1093/annonc/mdt499 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Robertson J, Macé C, Forte G, et al. . Medicines availability for non-communicable diseases: the case for standardized monitoring. Global Health 2015;11:18 10.1186/s12992-015-0105-0 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.World Health Organization Essential medicines. Available: http://www.who.int/medicines/services/essmedicines_def/en/ [Accessed 8 Feb 2018].

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

bmjgh-2018-001306supp001.pdf (142.1KB, pdf)